Jackson v. Motel 6 Multipurpose, Inc. Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Suggestion of Rehearing En Banc

Public Court Documents

December 30, 1997

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jackson v. Motel 6 Multipurpose, Inc. Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Suggestion of Rehearing En Banc, 1997. 90c990f8-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4b2ef1fa-8b4f-4f8d-b24c-68b2ec817d38/jackson-v-motel-6-multipurpose-inc-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-suggestion-of-rehearing-en-banc. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

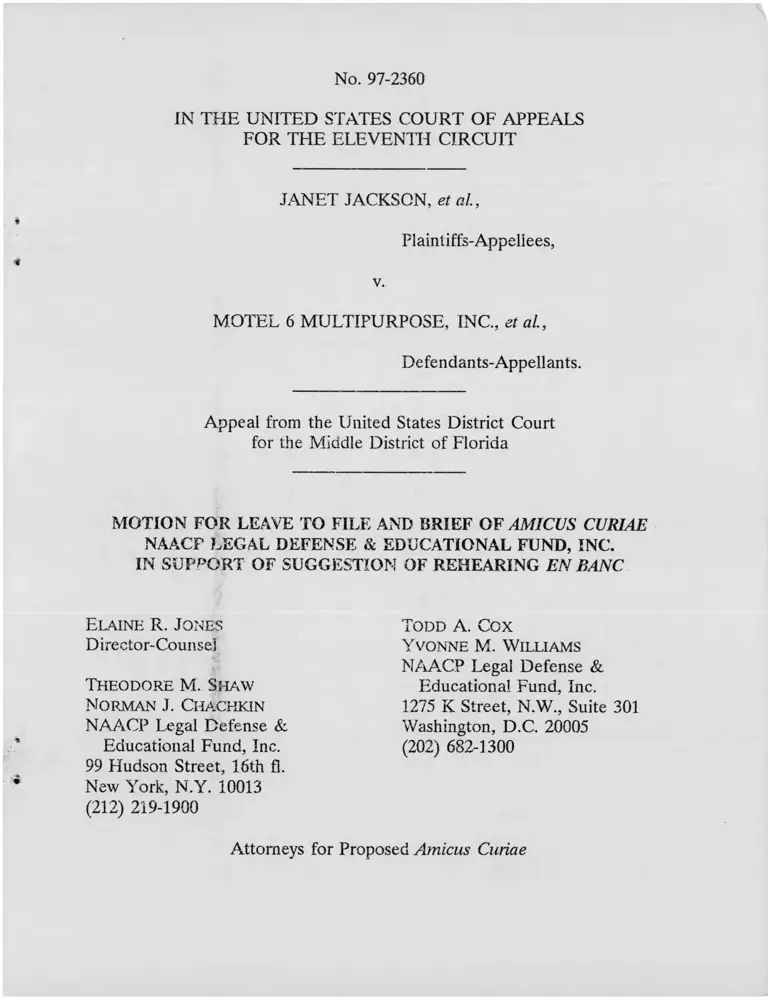

No. 97-2360

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

«

JANET JACKSON, et a l,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v .

MOTEL 6 MULTIPURPOSE, INC., et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Middle District of Florida

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE AND BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE

NAACF LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

IN SUPPORT OF SUGGESTION OF REHEARING EN BANC

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chackkin

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th fl.

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

Todd A. Cox

Yvonne M. Williams

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W., Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Attorneys for Proposed Amicus Curiae

Janet Jackson, et al. v. Motel 6 Multipurpose, Inc., et al., No. 97-2360

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

AND CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Accor S.A., Defendant-Appellant

Michael C. Addison, Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Audrey J. Anderson, Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Karl Baldwin, Plaintiff-Appellee

Jennifer Bethel, Plaintiff-Appellee

William O. Bittman, Attorney for Defendants-Appellants

C. Oliver Burt, III, Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Burt & Pucillo, Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Avis E. Buchanan, Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Norman J. Chachkin, Attorney for Amicus Curiae

Tanya Charles, Plaintiff-Appellee

Neil Chonin, Attorney for Defendants-Appellants

Chonin, Sher & Navarrete, P.A., Attorneys for Defendants-Appellants

Todd A. Cox, Attorney for Amicus Curiae

Lauren S. Dadario, Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellees

John C. Davis, Attorney for Defendants-Appellants

Delois Evans, Plaintiff-Appellee

Page Cl of 3

Defendants-Appellants

Jonathan S. Franklin, Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Brenda Hatcher, Plaintiff-Appellee

Hogan & Hartson L.L.P., Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Craig A. Hoover, Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellees

IBL Limited, Inc., Defendant-Appellant

Janet Jackson, Plaintiff-Appellee

Elaine R. Jones, Attorney for Amicus Curiae

Marcian Killsknight, Plaintiff-Appellee

Hon. Elizabeth A. Kovachevich, United States District Judge

Pitrall Lambert-Brown, Plaintiff-Appellee

Law Firm of Michael C. Addison, Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Theodore J. Leopold, Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Motel 6 G.P., Inc., Defendant-Appellant

Motel 6 Multipurpose, Inc., Defendant-Appellant

Motel 6 Operating L.P., Defendant-Appellant

NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc., Amicus Curiae

Dennis M. O’Hara, Attorney for Defendants-Appellants

Janet Jackson, et al. v. Motel 6 Multipurpose, Inc., et al., No. 97-2360

Fowler, White, Gillen, Boggs, Villareal and Banker, P.A., Attorneys f o r

Page C2 of 3

Michael J. Pucillo, Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Reed, Smith, Shaw & McClay, Attorneys for Defendants-Appellants

Edward M. Ricci, Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Ricci, Hubbard, Leopold & Frankel, Attorneys for

Plaintiffs-Appellees

Steven J. Routh, Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Joseph M. Sellers, Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Chevon Screen, Plaintiff-Appellee

Theodore M. Shaw, Attorney for Amicus Curiae

Kent Spriggs, Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Spriggs & Johnson, Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

James Stems, Plaintiff-Appellee

Charles Wachter, Attorney for Defendants-Appellants

Edward M. Waller, Jr., Attorney for Defendants-Appellants

Washington Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights and Urban Affairs,

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Wicker, Smith, Tutan & O’Hara, Attorneys for Defendants-Appellants

Yvonne M. Williams, Attorney for Amicus Curiae

Janet Jackson, et al. v. Motel 6 Multipurpose, Inc., et al., No. 97-2360

Mario Petaccia, Plaintiff-Appellee

Page C3 of 3

No. 97-2360

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

JANET JACKSON, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

MOTEL 6 MULTIPURPOSE, INC., et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Middle District of Florida

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

IN SUPPORT OF SUGGESTION OF REHEARING EN BANC

The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF), by

undersigned counsel, respectfully moves that this Court grant it leave to file

the appended Brief as Amicus Curiae in support of the Suggestion of

Rehearing En Banc filed by Plaintiffs-Appellees in this matter.

LDF has an extensive history of involvement in civil rights litigation,

including class action cases involving a wide variety of substantive issues.

Because of the profound impact that the December 10 ruling of a panel of

this Court will have upon such cases, and because of the importance of the

class action device in vindicating fundamental statutory civil rights, LDF

believes it is vitally important that an en banc Court be convened to reconsider

that ruling. Accordingly, we desire to present the members of the Court with

a brief statement of reasons why that course of action is imperative.

As of the time this brief is being submitted, counsel for proposed amicus

has been unable to secure consent to its filing from counsel for Defendants-

Appellants.

WHEREFORE, proposed amicus LDF respectfully prays that leave to

file the appended Brief be granted.

Respe ^ ’

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel Yvonne M. Williams

NAACP Legal Defense &

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

NAACP Legal Defense & Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

1275 K Street, N.W., Suite 301

Educational Fund, Inc.

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th fl.

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Proposed Amicus Curiae

- li -

Table of Contents

Page

Motion for Leave to File Brief ........................................................................i

Table of C itations................................................................................................iii

Certificate of Type Size and Style .................................................................vi

Statement of the Issue ..................................................................................... 1

Summary of the Argument .............................................................................. 1

ARGUMENT-

I. Rehearing En Banc Should Be Granted Because The

Panel Erred In Holding That Common Questions Do

Not Predominate In A Class Action Alleging A

Nationwide Policy And Practice Of Racial

Discrimination ............................................................................. 2

II. The Panel Ruling Ignores Critical Policy

Considerations Justifying The Use Of Class Actions ............ 9

Conclusion ........................................................................................................... 14

Certificate of Service ...................................................................................... 15

Table of Citations

Cases:

Amchem Prod., Inc. v. Windsor,

117 S. Ct. 2231 (1997) ................................................................ 4 ,5 ,12

Andrews v. American Tel. & Tel. Co.,

95 F.3d 1014 (11th Cir. 1996) ............................................................ 4, 5

- m -

Cases (continued):

Clark v. Universal Builders, Inc.,

501 F.2d 324 (7th Cir.), cert, denied, 419

U.S. 1070 (1974) .................................................................................... 12

Concerned Tenants Ass'n v. Indian Trails Apartments,

469 F. Supp. 522 (N.D. 111. 1980) ....................................................... 12

Cox v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co.,

784 F.2d 1546 (11th Cir.), cert, denied, 479

U.S. 883 (1986) ................................................................................. 6, 11

Dolgow v. Anderson,

43 F.R.D. 472 (E.D.N.Y. 1968) .......................................................... 6

Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co.,

424 U.S. 747 (1976) ............................................................ 6, 7n. 10, 14

Holmes v. Continental Can Co.,

706 F.2d 1144 (11th Cir. 1983) ................................................ 2, 3, 8, 9

International Bhd. of Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324 (1977) ......................................................... 6, 7, 8, 10, 14

Jenkins v. Raymark Industries, Inc.,

782 F.2d 468 (5th Cir. 1986) .............................................................. 14

Kerr v. City of West Palm Beach,

875 F.2d 1546 (11th Cir. 1989) ............................................................ 2

Kirkpatrick v. J.C. Bradford & Co.,

827 F.2d 718 (11th Cir. 1987) .............................................................. 3

Nichols v. Mobile Bd. of Realtors, Inc.

675 F.2d 671 (5th Cir. Unit B 1982) .................................................. 3

Table of Citations (continued)

Page

- IV -

Cases (continued):

Rossini v. Ogilvy & Mather, Inc.,

798 F.2d 590 (2d Cir. 1986), cert, denied, 485

U.S. 959 (1988) ...................................................................................... 4

Shroder v. Suburban Coastal Corp.,

729 F.2d 1371 (11th Cir. 1984) ....................................................... 6, 13

Vuyanich v. Republic Nat’l Bank,

521 F. Supp. 656 (N.D. Tex. 1981) ..................................................... 7

Statutes and Rules:

Fair Housing Act of 1968,

42 U.S.C. §§ 3601 et seq......................................................................... 12

42 U.S.C. § 3613(c)(1) ..................................................................................... 12

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(b)(2) ..........................................................................10, 11

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(b)(3) ........................................................................ passim

Other Authorities:

110 Cong. Rec. 14270 (1964) 7

Note, Antidiscrimination Class Actions Under the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure: The Transformation of

Rule 23(b)(2), 88 Yale L.J. 868 (1979) .............................................. 3

Gerald E. Rosen, Title VII Classes and Due Process:

To (b)(2) or not To (b)(3), 26 Wayne L. Rev.

919 (1980) 3

Table of Citations (continued)

Page

- v -

CERTIFICATE OF TYPE SIZE AND STYLE

Pursuant to Rule 28-2(d) of the Circuit Rules of the United States Court

of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, the undersigned counsel certifies that 14

point Dutch Roman was the size and style of type used in the Brief for

Amicus Curiae in Support of Suggestion of Rehearing En Banc.

- vi -

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

IN SUPPORT OF SUGGESTION OF REHEARING EN BANC

Statement of the Issues

Whether a class action may be certified under Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(b)(3)

in a case involving allegations of a nationwide policy or practice of racial

discrimination on the part of a motel chain even though the rights of class

members to damages will depend upon the individual circumstances

surrounding their requests for service at one or more facilities associated with

the chain.

Summary of the Argument

The panel held that, for purposes of class certification under Fed. R.

Civ. P. 23(b)(3), the common issue of whether Motel 6 has a practice or policy

of racial discrimination does not predominate over questions relating to the

circumstances under which individual class members may have sought services

at Motel 6 facilities. In the panel’s view, because individual class members’

entitlement to damages will not be solely determined by the question whether

Motel 6 has a practice or policy of racial discrimination but will also require

resolution of individual factual issues, the existence of such a policy or practice

will be irrelevant to the plaintiffs’ claims. While the panel makes a passing

reference to manageability concerns, its ruling rests upon a broad - and

erroneous - conclusion that the question whether Motel 6 maintained a

national policy of racial discrimination could not have sufficient predominance

in this case to justify class treatment.

The panel’s ruling turns the Rule 23(b)(3) inquiry on its head and

establishes a principle that could be broadly applied to defeat class action

treatment of a wide variety of civil rights cases, whenever damages relief as

well as injunctive remedies are sought. The panel’s error warrants rehearing

en banc by this Court.

ARGUMENT

I. Rehearing En Banc Should Be Granted Because The Panel Erred In

Holding That Common Questions Do Not Predominate In A Class

Action Alleging A Nationwide Policy And Practice Of Racial

Discrimination.

A. The Predominance Requirement is Satisfied

This Circuit has applied the terms of Rule 23(b)(3) and held that in

order for a class action to be certified under the rule, "[cjommon questions

must predominate over any questions that affect individual parties, and the

class device must be superior to all other available methods for the fair and

efficient adjudication of the dispute." Holmes v. Continental Can Co., 706 F.2d

1144, 1156 (11th Cir. 1983). See also Kerr v. City o f West Palm Beach, 875 F.2d

1546, 1557-58 (11th Cir. 1989) ("‘the issues in the class action that are subject

to generalized proof, and thus applicable to the class as a whole, must

- 2 -

predominate over those issues that are subject only to individualized proof")

(quoting Nichols v. Mobile Bd. of Realtors, Inc., 675 F.2d 671, 676 (5th Cir.

Unit B 1982)). Determining whether a common issue predominates

necessarily involves an inquiry into the factual and legal claims of the

individual class members’ cases. It is axiomatic that some of the facts

underlying the claims of individual class members may vary, but this does not

preclude class treatment. In fact, Rule 23(b)(3) contemplates that the class

members will be diverse, since "[ujnlike members of the (b)(2) class, members

of the (b)(3) class are usually not united by an ongoing legal relationship or

common trait that transcends the specific set of facts that gave rise to the

litigation." "The drafters of Rule 23 envisioned the (b)(3) class as being

‘heterogeneous in nature.’" Holmes, 706 F.2d at 1156 (citing Gerald E. Rosen,

Title VII Classes and Due Process: To (b)(2) or not To (b)(3), 26 Wayne L.

Rev. 919, 923 (1980) and Note, Antidiscrimination Class Actions Under the

Federal Rules o f Civil Procedure: The Transformation o f Rule 23(b)(2), 88 Yale

L.J. 868, 876 (1979).

Thus, the mere existence of factual differences among individual class

members does not justify a finding that the common issues do not

predominate and does not prevent class certification under Rule 23(b)(3). See

Kirkpatrick v. J.C. Bradford & Co., 827 F.2d 718, 724-25 (11th Cir. 1987) ("In

view of the overwhelming number of common factual and legal issues

- 3 -

presented . . . the mere presence of' individual factual issues "could not render

the claims unsuitable for class treatment"): Rossini v. Ogilvy & Mather, Inc., 798

F.2d 590, 599 (2d Cir. 1986) ("Commonality was not destroyed merely because

[a plaintiffs] individual claim also required proof of some facts that differed

from those of the class claim"; allegations concerning the employers

discriminatory policies constituted "common issues of law and fact [which]

predominated over those that separated [the plaintiff] from the class"), cert,

denied, 485 U.S. 959 (1988).

Here, the panel erred in determining that the common question whether

or not Motel 6 has a policy or practice of discrimination does not predominate

over the individual claims of the members of the plaintiff class for purposes

of class certification under Rule 23(b)(3). Relying on Andrews v. American

Tel. & Tel. Co., 95 F.3d 1014 (11th Cir. 1996), the panel held that the

plaintiffs’ claims will require "distinctly case-specific inquiries into the facts

surrounding each alleged incident of discrimination" and that any common

factual claims "will require highly case-specific determinations at trial." Slip

Op. at 14, 15. However, this case is not analogous to either Andrews or to

Amchem Prod., Inc. v. Windsor, 117 S. Ct. 2231 (1997), upon which the panel

relies. In Andrews, adjudication of the allegedly common question would have

required the district court to consider the substantive law of 50 different states

and would have required a review of various defendants’ "programs that in

- 4 -

many cases ha[d] little in common . . . "Andrews, 95 F.3d at 1024. Similarly,

Amchem involved consideration of different state laws which would apply to

plaintiffs’ claims and their widely diverse circumstances, including varying

levels of asbestos exposure, whether or not they had become ill, and, if so,

with what disease. Amchem, 117 S. Ct. at 2243, 2250. The settlement

formula, extinguishing class members’ opportunities separately to prosecute

their claims, was the only feature that would have been common to all class

members. In contrast, in this case, the same substantive federal law forms the

basis of all of the claims of plaintiff class members for relief from Motel 6’s

challenged discriminatory policy and practice.

The panel’s concern that proof of liability in this case will degenerate

into individual adjudications of the specific factual circumstances underlying

each member’s claim is misplaced. To the contrary, a challenge to a

defendant’s policy of racial discrimination does not require that each class

member offer proof of potentially divergent individual factual and legal claims

at this stage of the litigation. The proper inquiry in the class certification

phase is whether Motel 6 may have a policy of encouraging or tolerating

discrimination at its motels across the country. The factual allegations

contained in the affidavits submitted to the court below illustrate that this

issue is common to all class members. Although there may be other factual

questions, such as those related to specific injuries or damages of individual

- 5 -

plaintiffs, which may not be common to all class members, this is not

dispositive of the class certification issue under Rule 23(b)(3). As this Circuit

has recognized, "[t]he fact that questions peculiar to each individual member

of the class may remain after the common questions have been resolved does

not dictate the conclusion that a class action is not permissible." Shroder v.

Suburban Coastal Corp., 729 F.2d 1371,1378 (11th Cir. 1984) (quoting Dolgow

v. Anderson, 43 F.R.D. 472, 490 (E.D.N.Y. 1968)). Indeed, this Circuit has

held that once plaintiffs have proven the existence of a common policy of

discrimination, the burden shifts to the defendant to prove that individual class

members were not, in fact, victims of that discrimination. Cox v. American

Cast Iron Pipe Co., 784 F.2d 1546, 1559 (11th Cir.) (citing International Bhd.

of Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 336 (1977) and Franks v. Bowman

Transp. Co., 424 U.S. 747, 772 (1976)), cert, denied, 479 U.S. 883 (1986).

B. Pattern and Practice Cases are Appropriate for Class Treatment

The proper analysis in this case is, therefore, analogous to the analytical

framework defined by the Supreme Court for proving a pattern or practice of

discrimination in employment discrimination cases under Title VII in

Teamsters, which the Court itself recognized was not limited to the

employment context: "There would be a pattern or practice if, for example,

a number of companies or persons in the same industry or line of business

discriminated, if a chain of motels or restaurants practiced racial discrimination

- 6 -

throughout all or a significant part o f their system . . . Teamsters, 431 U.S. at

336 n.16 (emphasis supplied) (quoting 110 Cong. Rec. 14270 (1964).1

Under this analysis, a class of plaintiffs has the initial burden of proving

that the alleged "unlawful discrimination has been a regular procedure or

policy followed by an employer or a group of employers." Id. at 336, 360. In

order to facilitate the litigation, courts bifurcate the case into liability and

remedial phases. Id. at 361. Of course, during the liability phase, the

defendants may challenge plaintiffs’ proof of a policy through cross-

examination and the presentation of rebuttal evidence. Id. at 360. However,

at this stage, plaintiffs need not present evidence that each person who will

ultimately seek relief was a victim of the discriminatory policy, but only that

such a policy exists. Id. See Vuyanich v. Republic Nat’l Bank, 521 F. Supp.

656, 661 (N.D. Tex. 1981) (Higginbotham, J.) (class action treatment of

liability issue avoids "minuet" of "proof and counterproof" for each individual

claimant).

At the end of the liability stage, if it is determined that the defendant

has engaged in a regular practice of discrimination, the case moves to a

1Teamsters was a suit brought by the United States Attorney General;

however, the principles articulated in the Court’s opinion apply equally to

cases brought by private plaintiffs. See Franks, 424 U.S. at 772-73.

- 7 -

remedial phase to determine the individual relief to which each plaintiff is

entitled. Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 361, 362. In this phase, "the proof of the

pattern or practice supports an inference that any particular employment

decision during the period in which the discriminatory policy was in force was

made in pursuance of that policy." Id. at 362. The presumption of

discrimination also shifts to the defendants the burden of demonstrating that

the individual plaintiffs were not victims of the discriminatory policy. Id. at

362. It is at this point that the specific claims of plaintiffs are explored to

evaluate the effect which the discriminatory policy has had on individual

plaintiffs.

Therefore, as this Court determined in Holmes, 706 F.2d at 1157-58,

while the liability phase "stresses claims common to the class as a whole, and

if liability is found, results in injunctive or declaratory relief," the damages

stage "resolves whether a particular employee is in fact a member of the

covered class, has suffered financial loss, and thus is entitled to back pay or

other appropriate relief."

This is precisely the process this Circuit has previously determined is

appropriate for class actions certified under Rule 23(b)(3): there must be

common questions which predominate over questions which affect individual

plaintiffs, but there may also be diverse, heterogeneous claims unique to

individual parties. Such diversity is at the heart of Rule 23(b)(3) class

- 8 -

certification and this Court has endorsed the bifurcation process because it

"reflects a sensitivity toward the heterogeneous quality of the claims resolved

at the [damages] stage. . . Holmes, 706 F.2d at 1158.

The district court in this case had before it the sworn declarations of

members of the putative class, describing virtually identical experiences of

discrimination at Motel 6 facilities, which amply support an inference of a

systematic policy or practice of discrimination by Motel 6. It is this common

question regarding the policy of discrimination raised by this evidence that

predominates. The fact that there may be some individual claimants with

differing factual issues related to the damages remedy they seek does not bar

certification of the class under Rule 23(b)(3). Rather, this Court has

contemplated that a class certified under Rule 23(b)(3) would resolve any

individual divergent claims at the remedy phase, not at the liability trial, as

suggested by the panel. Thus, the fact that Motel 6 will later have the

opportunity, in any remedial stage of the litigation, to challenge the individual

claims of discrimination which resulted from this common policy, underscores

the importance of considering the claims in the class context.

II. The Panel Ruling Ignores Critical Policy Considerations Justifying The

Use Of Class Actions

The panel’s ruling represents a clear distortion of the predominance

requirement of Rule 23(b)(3). It also disregards important policy concerns

- 9 -

and threatens to undermine the ability of civil rights plaintiffs to maintain

class actions. The decision’s application to discrimination claims is particularly

troubling because it has the potential to preclude, or at least severely to

restrict, within this Circuit, class certification of these claims under Rule

23(b)(3). Moreover, by its logic the ruling could be extended to (b)(2) class

actions in which back pay or damages is sought, contrary to the controlling

holdings in Teamsters and Franks. In this fashion, the decision could affect

class treatment not only of other public accommodations claims involving

restaurants, entertainment and lodging, but also of a wide variety of claims of

discrimination in employment, housing and education. The en banc Court

should be convened to prevent this result by reversing the panel’s decision.

The practical effect of the panel’s decision is easy to predict. In any

discrimination case challenging an institutional pattern or practice, the

defendant will oppose - and may all too often defeat -- class certification on

the ground that the circumstances surrounding the application of the

discriminatory policy to individual victims predominate over issues common

to the class. Obviously, a policy or practice must be applied to individuals or

implemented by a defendant before it is discernible and before it may cause

harm. The defense to class certification now available under the panel’s ruling

can be raised in virtually every case challenging such a policy or practice and

at a minimum will preclude Rule 23(b)(3) class certification in every instance.

- 10 -

The ramifications of this decision on other discrimination claims are

obvious. For example, class claims alleging employment discrimination in

hiring and/or promotions have long been recognized within this Circuit. See,

e.g., Cox v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co. With the availability of compensatory

and punitive damages under the Civil Rights Act of 1991, it is reasonable to

expect an increase in class claims of employment discrimination that may be

brought under both Rule 23(b)(2) and Rule 23(b)(3). Under the panel’s

reasoning, persons moving for class certification of such claims will be forced

to overcome the presumption that the application of the allegedly unlawful

policy to individual victims is fraught with so many disparate factual issues that

class certification is improper. Plaintiffs in employment cases will be faced

with the almost insurmountable task of demonstrating that the circumstances

surrounding the employment decisions, such as the job qualifications of

individual class members, the number and nature of available positions, the

qualifications necessary for those positions, whether class members applied for

the positions, and the qualifications of other applicants for the positions, do

not require "distinctly case-specific inquiries into the facts surrounding each

alleged incident of discrimination." See Slip Op. at 14.

Plaintiffs seeking Rule 23(b)(3) certification for housing discrimination

claims would fare no better. While not commonly used, Rule 23(b)(3)

certification is available to plaintiffs bringing class claims under the Fair

- 11 -

Housing Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C. §§ 3601 et seq. See, e.g., Clark v. Universal

Builders, Inc., 501 F.2d 324 (7th Cir.), cert, denied, 419 U.S. 1070 (1974);

Concerned Tenants Ass’n v. Indian Trails Apartments, 496 F. Supp. 522 (N.D.

111. 1980). The availability of increased damages pursuant to the 1988

amendments to the Act suggests that courts will increasingly characterize these

suits as (b)(3) cases. See 42 U.S.C. § 3613(c)(1). In this Circuit, however,

these claims will be subject to the same arguments imposed on the Jackson

plaintiffs in this case regarding predominance and manageability. For

example, in a case alleging discriminatory refusal to rent, the tenant class will

be forced to demonstrate that the conditions surrounding each tenant’s

application, such as the availability of apartments and the qualifications of the

tenant, do not predominate over the common issue of the owner’s policy or

practice of excluding African-American tenants. The panel’s decision severely

threatens their ability to do so successfully.

Apart from the practical effect of the panel’s ruling on future

discrimination cases in this Circuit, the ruling suggests a fundamental conflict

with the long-recognized principle that class actions are an important

mechanism for vindicating the rights of groups of persons. See Amchem, 117

S. Ct. at 2246 (one of the core concerns behind Rule 23(b)(3) is to ensure "the

rights of groups of people who individually would be without effective strength

to bring their opponents into court at all") (citations omitted). This Circuit

- 12-

has recognized the importance of class actions in situations where plaintiffs

are unable to bring individual actions, particularly civil rights suits. See

Shroder, 729 F.2d at 1376 ("Throughout our legal history, a shortage has

existed of plaintiffs willing and available to file civil rights class actions. The

courts are thus, quite rightly, hesitant to deny class certification in civil rights

cases"). The ruling here threatens the ability of victims of discrimination to

use the class action as an effective and efficient means of challenging

institutional discrimination made unlawful by federal civil rights laws.2 If

victims must prove unlawful conduct through individual claims only, there will

be little opportunity to demonstrate the existence of a discriminatory policy.

As a result, individual plaintiffs and class members will lose the important

2The panel does not even address the fact that the class action may be the

only means for the plaintiffs in this case and others to pursue their claims

against Motel 6. The district court found that, due to Motel 6’s inexpensive

rental rates, individual damages are likely to be small and below the cost of

filing a civil action. Order Granting Jackson Plaintiffs’ Motion for Class

Certification and Referring Petaccia Plaintiffs’ Motion for Class Certification,

August 15, 1997, at 14-15. The district court also noted that few, if any,

private lawyers would agree to litigate these individual actions and that

individual plaintiffs proceeding pro se would be untenable. Id.

- 13 -

advantage, provided in Franks and Teamsters and their progeny, to shift the

burden to the defendant to prove that individuals were not subjected to the

discriminatory policy. Individual victims thus will be precluded from

aggregating their claims in one forum and mounting a collective challenge to

discrimination in a manner which strengthens their individual claims. The

panel does not address how this result could possible be superior or more

efficient for the judicial process than maintaining this class action. See Jenkins

v. Raymark Industries, Inc., 782 F.2d 468, 473 (5th Cir. 1986).

For the reasons stated above and based on the authorities cited,

plaintiffs-appellees’ Suggestion of Rehearing En Banc should be granted.

CONCLUSION

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

NAACP Legal Defense &

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

NAACP Legal Defense & Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

1275 K Street, N.W., Suite 301

Educational Fund, Inc.

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th fl.

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

- 14 -

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that on this 30th day of December, 1997,1 served a copy

of the foregoing Motion for Leave to File and Brief of Amicus Curiae NAACP

Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. in Support of Suggestion of

Rehearing En Banc upon counsel for the parties to this appeal, by depositing

the same in the United States mail, first-class postage prepaid, addressed as

follows:

William O. Bittman, Esq.

Reed Smith Shaw & McClay

1301 K Street, N.W.

East Tower - Suite 1100

Washington, D.C. 20005

Kent Spriggs, Esq.

John C. Davis, Esq.

Spriggs & Johnson

324 West College Avenue

Tallahassee, Florida 32301

Craig A. Hoover, Esq.

Steven J. Routh, Esq.

Audrey J. Anderson, Esq.

Jonathan S. Franklin, Esq.

Hogan & Hartson L.L.P.

555 Thirteenth Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20004

Edward M. Ricci, Esq.

Theodore J. Leopold, Esq.

Ricci, Hubbard, Leopold & Frankel

United National Bank Building

1645 Palm Beach Lakes Boulevard

W. Palm Beach, Florida 33402

Charles Wachter, Esq.

Fowler, White, Gillen, Boggs

Villareal and Banker. P.A.

P.O. Box 1438

501 E. Kennedy Boulevard

Tampa, Florida 33601

Neil Chonin, Esq.

Chonin, Sher & Navarette, P.A.

304 Palermo Avenue

Coral Gables, Florida 33134-

6608

C. Oliver Burt, III, Esq.

Lauren S. Dadario, Esq.

Burt & Pucillo

Esperante, Suite 300 East

222 Lakeview Avenue

W. Palm Beach, Florida 33401

Avis E. Buchanan, Esq.

Washington Lawyers’

Committee for Civil Rights

and Urban Affairs

1300 19th Street, N.W., #500

Washington, D.C. 20036

- 15 -

Michael C. Addison

Law Firm of Michael C. Addison

100 North Tampa Street

Suite 2175

Tampa, Florida 33602-5145

Norman J/Chachkin