Missouri v. Jenkins Brief of Respondents Kalima Jenkins et al.

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Missouri v. Jenkins Brief of Respondents Kalima Jenkins et al., 1988. 1aaae5ed-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4b3f2dff-ddf5-45c1-9807-e6e3bc06afda/missouri-v-jenkins-brief-of-respondents-kalima-jenkins-et-al. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

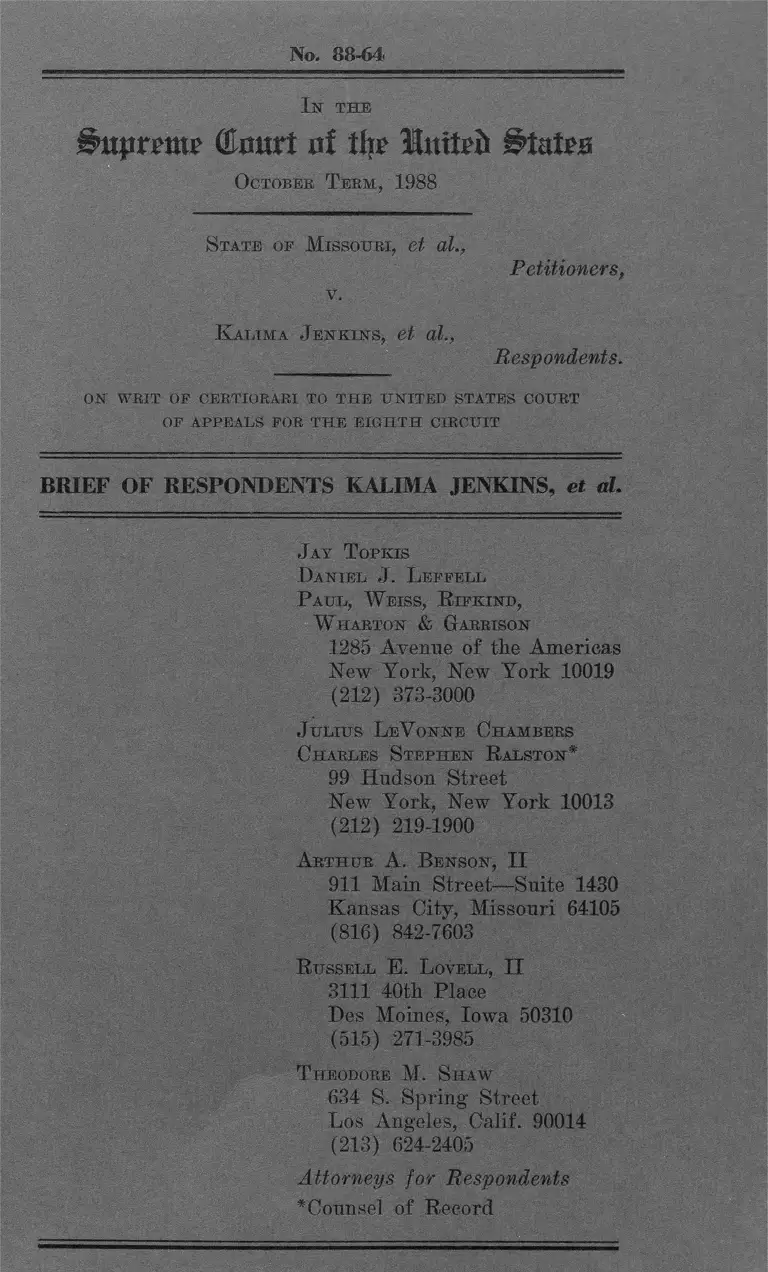

No. 88-64

I n t h e

Bnprmu (&mxt 0 I Ulnxttb Butm

O ctober T e e m , 1988

S tate of M issouri, et al.,

Petitioners,

K alima J e n k in s , et al.

Respondents.

O N W H IT O P CER TIO R A R I TO T H E U N IT E D STA TES COU RT

O F A P P E A L S FO R T H E E IG H T H C IR C U IT

BRIEF OF RESPONDENTS KALIMA JENKINS, et al.

J ay T opkis

D a n iel J . L e ppe l l

P aul, W eiss , R if k in d ,

W harton & Garrison

1285 Avenue of the Americas

New York, New York 10019

(212) 373-3000

J u liu s L eV onnb Chambers

C harles S t e p h e n R alston*

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

A r t h u r A. B enson , I I

911 Main Street—Suite 1430

Kansas City, Missouri 64105

(816) 842-7603

R ussell E. L ovell, I I

3111 40th Place

Des Moines, Iowa 50310

(515) 271-3985

T heodore M. S haw-

634 S. Spring Street

Los Angeles, Calif. 90014

(213) 624-2405

Attorneys for Respondents

*Counsel of Record

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ....................................................... 1

A. The Desegregation Litigation.......................................... 1

B. The Fee Award ................................................................. 3

SUMMARY OF A RGU M EN T....................................................... 4

ARGUM ENT..................................................................................... 5

I. THE ELEVENTH AMENDMENT DOES NOT

BAR COMPENSATION FOR DELAY

IN PAYM ENT............................................................................ 5

A. This Court’s Eleventh Amendment

Decisions Do Not Support

The State’s Position ......................................................... 5

1. The Eleventh Amendment Does

Not Apply to Awards of

Costs or to Interest on a

Component of C osts................................................. 7

2. The Eleventh Amendment Does

Not Require Specific Statutory

Reference to Compensation

for Delay in Section 1988........................................ 10

B. Library o f Congress v. Shaw

Is Not Controlling ......................................................... 14

1. The No-Interest Rule Cannot

Be Extended to the Eleventh

Am endm ent............................................................. 14

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

2. The No-Interest Rule Would

Be an Unreasonable Rule of

Statutory Construction Here ................................ 18

C. This Court Should Overrule

Hans v. Louisiana if It

Reaches the Question..................................................... 19

D. Section 1988 Authorizes

Compensation for Delay in

Fee Awards Against the

S ta tes ................................................................................ 21

II. SECTION 1988 AUTHORIZES THE

AWARD OF FEES FOR PARALEGALS

AT MARKET RA TES............................................................. 26

A. The Result the State Seeks

Would Undermine the Purpose

of Section 1988 ................................................................. 28

B. The Result the State Seeks

Would Increase the Costs of

Litigation ........................................................................ 30

C. The State’s Arguments Are

Without Merit ................................................................. 33

CONCLUSION ................................................................................ 35

- ii -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Albrecht v. United States,

329 U.S. 599 (1947)...................................................................... 24

Alyeska Pipeline Serv. Co. v.

Wilderness Soc‘y,

421 U.S. 240 (1975)........................ 7

Atascadero State Hosp. v.

Scanlon,

473 U.S. 234 (1985)......................................................... 6, 8, 11, 20

Behlar v. Smith,

719 F.2d 950 (8th Cir. 1983),

cert, denied, 466 U.S. 958

(1984)............................................................................................. 12

Bernard McMenamy Contractors,

Inc. v. Missouri State Highway

Comm'n, 582 S.W.2d 305

(Mo. App. 1979) .......................................................................... 17

Blum v. Stenson,

465 U.S 886 (1984) ....................................................... 5, 23, 26-30

Bradley v. Richmond School Bd.,

416 U.S. 696 (1974)...................................................................... 24

Brown v. Board o f Educ.,

347 U.S. 483 (1954).................................................................... 1, 2

Cameo Convalescent Center, Inc. v.

Senn, 738 F.2d 836 (7th Cir.

1984), cert, denied,

469 U.S. 1106 (1985).................................................................... 32

Chesser v. Illinois,

1987 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 7398

(N.D. 111. Aug. 11, 1987)............................................................... 12

Chisholm v. Georgia,

2 Dali. (2 U.S.) 419 (1793)........................................................... 20

Page(s)

- iii -

Page(s)

City o f Riverside v. Rivera,

A ll U.S. 561 (1986)................................................. ..................... 22

Daly v. Hill,

790 F.2d 1071 (4th Cir. 1986) ..................................................... 25

Davis v. County o f Los Angeles,

8 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA)

244, 8 Empl. Prac. Dec. (CCH)

1 9444 (C.D. Cal. June 5, 1974) ..................................... 29-30, 33

Denton Constr. Co. v. Missouri

State Highway Comm’n,

454 S.W.2d 44 (Mo. 1970) ........................................................... 17

Easter House v. Illinois

Dep ’t o f Children

and Family Serv.,

663 F. Supp. 456 (N.D.

111. 1987) ...................................................................................... 31

Edelman v. Jordan,

415 U.S. 651 (1974)........................................................................ 7

Employees v. Department o f

Pub. Health & Welfare,

411 U.S. 279 (1973)............................................................... 6, 8, 13

Fairmont Creamery Co. v. Minnesota,

215 U.S. 70 (1927)........................................................................ 16

Feher v. Department o f Labor &

Indus. Relations, 561

F. Supp. 757 (D. Hawaii 1983)................................................... 27

Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer,

A ll U.S. 445 (1976)........................................................... 11, 15, 18

Gaines v. Dougherty County Bd.

o f Educ., 115 F.2d 1565

(11th Cir. 1985) (per curiam) ..................................................... 25

Garcia v. San Antonio Metro.

Transit Auth.,

469 U.S. 528 (1985)................................................................. 20-21

- iv -

Page(s)

Garmong v. Montgomery County,

668 F. Supp. 1000 (S.D.

Tex. 1987)...................................................................................... 32

Gelofv. Papineau,

648 F. Supp. 912 (D. Del. 1986),

offd in part, vacated in part,

829 F.2d 452 (3d Cir. 1987)......................................................... 12

General Motors Corp. v. Devex Corp.,

461 U.S. 648 (1983)...................................................................... 24

Graves v. Barnes,

700 F.2d 220 (5th Cir. 1983) ....................................................... 12

Green v. Mansour,

474 U.S. 64 (1985)................................................................ 7, 9, 16

GrendeVs Den, Inc. v. Larkin,

749 F.2d 945 (1st cir. 1984)................................................... 12, 25

Hans v. Louisiana,

134 U.S. 1 (1890)............................................................... 5, 19-20

Heiar v. Crawford County,

746 F.2d 1190 (7th Cir. 1984)

cert, denied, A ll U.S. 1027

(1985)....................................................................................... 23-24

Hensley v. Eckerhart,

461 U.S. 424 (1983)....................................................... 3, 22-24, 29

Hutto v. Finney,

437 U.S. 678 (1978) ...............................................................passim

Jacobs v. Mancuso,

825 F.2d 559 (1st Cir. 1987)................................................... 32, 34

Jenkins v. Missouri,

838 F.2d 260 (8th Cir. 1988) ...................................................... 26

Jenkins v. Missouri,

855 F.2d 1295 (8th Cir. 1988) 2

Page(s)

Jenkins v. Missouri,

593 F. Supp. 1485 (W.D. Mo.

1984) 2

Jenkins v. Missouri,

639 F. Supp. 19 (W.D. Mo. 1985),

a jf d in part, mod. in part,

807 F.2d 657 (8th Cir. 1986)

(en banc).............................................................. 2

Johnson v. Georgia Highway

Express, Inc.,

488 F.2d 714 (5th Cir. 1974) ....................................................... 29

Johnson v. University College,

706 F.2d 1205 (11th Cir.), cert.

denied, 464 U.S. 994 (1983)......................................................... 25

Jordan v. Multnomah County,

815 F.2d 1258 (9th Cir. 1987) ..................................................... 25

Kawananakoa v. Polyblank,

205 U.S. 349 (1907)................................................................. 15-16

Keith v. Volpe,

501 F. Supp. 403 (C.D. Cal.

1980) ............................................................................................. 32

Knight v. DeMarea,

670 S.W.2d 59 (Mo. App. 1984).................................................. 17

Lamphere v. Brown Univ.,

610 F.2d 46 (1st Cir. 1979)........................................................... 34

Laughlin v. Boatmen’s Nat’l Bank,

354 Mo. 467, 189 S.W.2d 974

(Mo. 1945) .................................................................................... 17

- vi -

Page(s)

Liberies v. Daniel,

26 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA)

547, 26 Empl. Prac. Dec. (CCH)

1 31,816 (N.D. 111. March 20,

1981), o ff d in part, rev’d

in part, 709 F.2d 1122

(7th Cir. 1983).............................................................................. 12

Library o f Congress v. Shaw,

478 U.S. 310 (1986).................................. .......... 4, 9-10, 14-19, 23

Lightfoot v. Walker,

826 F.2d 516 (7th Cir. 1987) ........................................... 12, 24, 25

Loefler v. Frank,

108 S. Ct. 1965 (1988).................................................................. 24

Maher v. Gagne,

448 U.S. 122 (1980).................................................................... 6, 8

Milliken v. Bradley,

433 U.S. 267 (1977)........................................................................ 7

Nevada v. Hall,

440 U.S. 410 (1979)................................................................. 15-16

New York State Ass ’n for

Retarded Children v. Carey,

711 F.2d 1136 (2d Cir. 1983)....................................................... 25

Northcross v. Board o f Educ.,

611 F.2d 624 (6th Cir. 1979),

cert, denied, 447 U.S. 911

(1980)................................................................................. 24, 25, 27

Papasan v. Allain,

478 U.S. 265 (1986).............................................................. 7, 9, 16

Pennhurst State School & Hosp. v.

Halderman, 451 U.S. 1 (1980)

(“.Pennhurst 7”) .............................................................................. 8

Pennhurst State School & Hosp. v.

Halderman, 465 U.S. 89 (1984)

(“Pennhurst IP’) ................................................................. 8, 13, 16

— vii —

Page(s)

Pennsylvania v. Delaware Valley

Citizens Council,

107 S. Ct. 3078 (1987)................................................................... 26

Platoro, Ltd. v. Unidentified

Remains o f a Vessel,

695 F.2d 893 (5th Cir.), cert.

denied, 464 U.S. 818 (1983)......................................................... 12

Quern v. Jordan,

" 440 U.S. 332 (1979)................................................................... 7, 8

Ramos v. Lamm,

713 F.2d 546 (10th Cir. 1983) .................................... 12, 25, 27, 28

Richardson v. Byrd,

709 F.2d 1016 (5th Cir.

1983), cert, denied,

464 U.S. 1009 (1985)............................................................... 27, 31

Rogers v. Okin,

821 F.2d 22 (1st Cir. 1987)........................................................... 12

St. Joseph Light & Power Co. v.

Zurich Ins. Co.,

698 F.2d 1351 (8th Cir. 1983) ..................................................... 17

Save Our Cumberland Mountains,

Inc. v. Hodel,

826 F.2d 43 (D.C. Cir. 1987),

vacated in part, 857 F.2d 1516

(D.C. Cir. 1988)............................................................................ 27

Sisco v. J.S. Alberici

Constr. Co.,

733 F.2d 55 (8th Cir. 1984) ......................................................... 25

Slay Warehousing Co. v. Reliance

Ins. Co.,

489 F.2d 214 (8th Cir. 1974) ....................................................... 17

Smyth v. United States,

302 U.S. 329 (1937)........................

- viii -

24

Page(s)

Spanish Action Comm. v. City

o f Chicago,

811 F.2d 1129 (7th Cir. 1987) ..................................................... 27

Spray-Rite Serv. Corp v.

Monsanto Co.,

684 F.2d 1226 (7th Cir. 1982),

affd, 465 U.S. 752 (1984)............................................................. 31

Stanford Daily v. Zurcher,

64 F.R.D. 680 (N.D. Cal. 1974)................................................... 29

Steppelman v. State Highway

Comm ’n,

650 S.W.2d 343 (Mo. App. 1983)............................................... 17

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Bd. o f Educ.,

66 F.R.D. 483 (W.D.N.C. 1975) ............................................ 24, 29

The Siren,

1 Wall. (74 U.S.) 152 (1868)......................................................... 15

United States v. Chemical

Found., Inc.,

272 U.S. 1 (1926).......................................................................... 10

Vaughns v. Board of Educ.,

598 F. Supp. 1262 (D. Md. 1984),

affd, 770 F.2d 1244 (4th Cir.

1985) 27

Whalen, Murphy, Reid v. Estate o f

Roberts,

711 S.W.2d 587 (Mo. App. 1986)............................................... 17

Welch v. Texas Dep’t o f

Highways & Pub. Transp.,

107 S. Ct. 2941 (1987)............................................. 8, 12, 15-16, 19

Constitutional Provisions and Statutes:

U.S. Const, art III ............................................................................ 20

- ix -

Page(s)

U.S. Const, amend. XI .............................................................passim

U.S. Const, amend. X IV ................................................... . 4, 6, 20

42 U.S.C. § 1988 ........................................................................ passim

42 U.S.C. § 20003-5(k)....................................................................... 9

Mo. Rev. Stat. § 408.020 (1986) ....................................................... 17

Legislative Materials:

H. R. Rep. No. 1558, 94th Cong.,

2d Sess. (1976)............................................................. 18, 20-23, 28

S. Rep. No. 1011, 94th Cong.,

2d Sess. (1976)............................................................. 22-25, 28, 29

2 Annals of Cong. 1897 (1791)......................................................... 21

Other Authorities:

Bureau of Labor, Statistics, U.S.

Dep’t of Labor, Occupational

Outlook Quarterly (Spring 1986)................................................. 31

Engdahl, Immunity and Account

ability for Positive Government

Wrongs,

44 U. Colo. L. Rev. 1 (1972) ....................................................... 15

Model Rules o f Professional

Conduct (ABA 1983) .................................................................... 23

Model Standards and Guidelines for

Utilization o f Legal Assistants,

(NALA 1984) .............................................................................. 31

F. Pollock & F. Maitland,

History o f English Law

(2d ed. 1899) ................................................................................ 15

R. Posner, Economic Analysis o f Law

(3d Ed. 1986) 23

No. 88-64

In The

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

O ctober Term, 1988

State of M issouri, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Kalima Jenkins, et al.,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF RESPONDENTS KALIMA JENKINS, et al.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Plaintiffs’ counsel come before this Court seeking affir

mance of the fees awarded them for having proven unconstitutional

segregated education in Kansas City, Missouri — and having obtained

extensive remedies that hold real promise of equal educational oppor

tunity and meaningful desegregation.

The victory was neither swift nor easy.

A. The Desegregation Litigation

In 1977, twenty-three years after Brown v. Board o f Educa

tion, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), segregation still infected the education of

black children in the Kansas City School District (the “School Dis

trict”). The School District, its School Board, and the children of two

School Board members commenced this action, seeking desegregation

remedies against the State of Missouri and others.

- 1 -

In 1979, Arthur Benson entered an appearance on behalf

of the plaintiff school children. Mr. Benson and his small staff prose

cuted the case through three years of extensive motion practice and

discovery. By 1982, however, it was apparent that this bitterly con

tested litigation would require resources far beyond Mr. Benson’s. The

School District, which had been realigned as a nominal defendant, ad

mitted its historic responsibility for discrimination and supported

plaintiffs. But the State — whose pre-Brown laws required segrega

tion, and which had done virtually nothing post-Brown to end segrega

tion — fought this litigation at every step, and with every resource at its

disposal. And so, Mr. Benson sought and obtained the assistance of

the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (“the LDF”), a

nonprofit organization dedicated to the enforcement of civil rights.

The LDF entered the case as Mr. Benson’s co-counsel in March 1982.

In September 1984, after a 92-day bench trial, the district

court held the State defendants and the School District liable.

Jenkins v. Missouri, 593 F. Supp. 1485 (W.D. Mo. 1984). In June 1985,

after a further two-week hearing on remedies, plaintiffs obtained an

order requiring $37 million in capital improvements and $50.7 million

in new operating programs. Jenkins v. Missouri, 639 F. Supp. 19 (W.D.

Mo. 1985), (iff d in part, mod. in part, 807 F.2d 657 (8th Cir. 1986) (en

banc).

While the initial remedial order was on appeal, and after

the appeal, the district court ordered greatly increased relief: an initial

$25 million magnet-school plan, later expanded by $196 million, and

long-range capital improvements totalling $260 million. The court of

appeals affirmed. Jenkins v. Missouri, 855 F.2d 1295 (8th Cir. 1988).

Achieving these results in the face of Missouri’s recalci

trance was not easy. From 1979, Mr. Benson and attorneys he em

ployed devoted 10,875 hours to the case. His law clerks (working law

students) and paralegals worked 8,108 hours. From early 1983 to the

end of 1985, Mr. Benson devoted nearly all of his professional time to

this case — he could accept no other employment. Although his dedi

cated associates and employees agreed to defer payment for overtime

work, he paid them their base salaries throughout the litigation. He

- 2 -

exhausted his personal resources and was able to persist only by bor

rowing $633,000. Through December 31,1986, he paid $113,706 in in

terest on this debt and continued to pay approximately $5,000 a month

(Benson Aff., filed Jan. 16, 1987; Tr. 131-32).

Beginning in 1982, LDF attorneys spent 10,854 hours on

the case. Recent law school graduates, law clerks and paralegals

worked 15,517 hours. This was the most expensive case in which the

LDF had ever been involved; largely because of it, the LDF had deficits

of $700,000 in 1983 and more than $1 million in 1984 (Tr. 46, 48; PI.

Ex. 2).

B. The Fee Award

Mr. Benson and the LDF, as attorneys for the prevailing

plaintiffs, filed applications under the Civil Rights Attorney’s Fees

Awards Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C. § 1988 (“Section 1988”). The district

court held a one-day hearing, at which plaintiffs presented four wit

nesses. The State presented no witnesses; it did no more than ask

Mr. Benson a few clarifying questions about his application (Tr.

121-30).

On May 11, 1987, the district court issued an opinion me

ticulously analyzing the positions of the parties. The court awarded

Mr. Benson fees and expenses of $1,614,437 for work on the merits,

and $72,702 for the fees litigation. The court later awarded Mr. Benson

an additional $42,090 for monitoring fees and expenses, bringing the

total Benson fees judgment to $1,729,230. The court awarded the LDF

fees and expenses of $2,323,730 for work on the merits, and $42,145 for

work on the fees litigation, for a total LDF judgment of $2,365,875. V

V Counsel did not request fees for all the time spent on the litigation. In compli

ance with Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424 (1983), the applications excluded 3,628 at

torney hours and 7,046 hours for paralegals, law clerks and recent law graduates, repre

senting time allocable to unsuccessful claims. Based on the hourly rates actually

awarded, these reductions amounted to more than $700,000. The district court required

a further reduction of 3.5 hours in the LDF application (Pet. App. A32).

- 3 -

The court found that current market rates for Kansas City

attorneys with litigation experience and expertise comparable to

Mr. Benson’s ranged from $125 to $175 an hour, and that Mr. Benson’s

rate “would fall at the higher end of the range based on his expertise in

the area of civil rights” (Pet. App. A26). The court applied a small en

hancement to Mr. Benson’s time, awarding him $200 an hour to com

pensate for “preclusion of other employment,” the “undesirability of

this case” and “delay in payment” (id.). The court based its award for

the work of the other attorneys, as well as paralegals, law clerks and

recent law graduates, on current Kansas City market rates, “to com

pensate . . . for the delay in payment” (id.; see also id. at A30, A33,

A34).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Section 1988 authorizes the federal courts to award pre

vailing civil rights plaintiffs “a reasonable attorney’s fee as part of the

costs.” The courts below did so. Before this Court, the State raises two

objections to the award. Each is without merit.

1. The State contends that the courts below, by con

sidering delay in payment in assessing a “reasonable” fee, awarded

“prejudgment interest” (Pet. Br. 9, 21). This violates the Eleventh

Amendment, the State claims, because Section 1988 does not provide

for prejudgment interest against the states “in unmistakable lan

guage” (id. at 11).

The Eleventh Amendment, however, does not apply to fee

awards in actions for prospective relief, such as this. Moreover, Sec

tion 1988, enacted pursuant to the Fourteenth Amendment, abrogates

any immunity the states might otherwise enjoy. The Eleventh Amend

ment does not require that such a statute authorize compensation for

delayed payment “in unmistakable language” or in any particular

form. Library o f Congress v. Shaw, 478 U.S. 310 (1986), on which the

State relies, has no application to the Eleventh Amendment.

Moreover, this case — an action by citizens of a state

against that state — does not fall within the plain language of the Elev

- 4 -

enth Amendment. Hans v. Louisiana 134 U.S. 1 (1890), which held the

Eleventh amendment applicable to such cases, should be overruled.

2. The State contends that the courts below erred in

awarding fees for paralegals at market rates rather than “cost” (Pet.

Br. 24-27). Neither the language of Section 1988, nor its legislative his

tory, nor any decision of this Court supports the State’s position. In

deed, this Court has specifically rejected the view that fees under Sec

tion 1988 should “be calculated according to the cost of providing legal

services rather than according to the prevailing market rate.” Blum v.

Stenson, 465 U.S. 886, 895 (1984). The result Missouri seeks would un

dermine the purpose of Section 1988 by discouraging private enforce

ment of the civil rights laws. It would also promote costly, inefficient

litigation by pressuring lawyers to do work that could be done by

paralegals.

ARGUMENT

I.

THE ELEVENTH AMENDMENT DOES NOT BAR

COMPENSATION FOR DELAY IN PAYMENT

The State does not suggest that the Eleventh Amendment

restricts Congress’ power to authorize fee awards against the states.

Nor does the State dispute Congress’ power to authorize compensa

tion for delay. Rather, the State contends that such compensation con

stitutes “interest,” and that the Eleventh Amendment bars the federal

courts from awarding interest against a state absent a specific, explicit

statutory mandate. Neither precedent nor policy supports the State’s

view.

A. This Court’s Eleventh Amendment

Decisions Do Not Support

The State’s Position

This Court has held that the Eleventh Amendment re

quires “an extraordinarily explicit statutory mandate” before a federal

court may infer that Congress has authorized it to hear certain claims

- 5 -

against the states. Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678, 695 (1978). Where it

applies, this requirement “insures that Congress has not imposed

'enormous fiscal burdens on the States’without careful thought.” Id. at

697 n.27 (quoting Employees v. Department o f Pub. Health & Welfare,

411 U.S. 279,284 (1973)). Accordingly, before a federal court may hear

a federal claim against a state for retroactive, monetary relief, “Con

gress must express its intention to abrogate the Eleventh Amendment

in unmistakably clear language in the statute itself.” Atascadero State

Hosp. v. Scanlon, 473 U.S. 234, 243 (1985). Relying on Atascadero and

similar decisions, the State contends that the fee awards in this case

were impermissible, because Section 1988 does not expressly refer, “in

the statute itself,” to liability of the states or compensation for delay

(Pet. Br. 16).

The State’s reliance is misplaced. The stringent standards

for abrogation set forth in this Court’s Eleventh Amendment decisions

do not address litigation costs. Rather, they are informed and limited

by concern for the “enormous fiscal burdens” that retroactive liability

for prelitigation conduct may impose upon the states. Moreover, those

decisions have no bearing on the issue here — the scope of a statute

that lawfully and undisputedly applies against the states.

In Hutto, the Court held that Section 1988 authorizes costs,

including attorneys’ fees, against state defendants, notwithstanding

the Eleventh Amendment. Two rationales compelled this conclusion.

First, Section 1988 “imposes attorney’s fees ‘as part of the costs,”’ and

the Court “has never viewed the Eleventh Amendment as barring such

awards.” 437 U.S. at 695; see Maher v. Gagne, 448 U.S. 122,131-32 &

n.14 (1980). Second, “even if the Eleventh Amendment would other

wise present a barrier to an award of fees against a state, Congress was

clearly acting within its power under § 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment

in removing that barrier.” Maher, 448 U.S. at 132. Either of these ra

tionales disposes of Missouri’s claim to immunity.

- 6 -

1. The Eleventh Amendment Does Not

Apply to Awards of Costs or to

Interest on a Component of Costs

In enacting Section 1988, Congress provided the statutory

authorization necessary to award attorney’s fees to prevailing civil

rights plaintiffs. SeeAlyeska Pipeline Serv. Co. v. Wilderness Soc’y, 421

U.S. 240 (1975). This Court’s decisions make clear that the Eleventh

Amendment has no effect on this statute.

In Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974), the Court held

that the Eleventh Amendment bars actions in federal court seeking to

impose retrospective monetary liabilities on the states. Id. at 668. The

Court distinguished prospective relief, even though prospective relief

may have “an ancillary effect on the state treasury.” Id. 2/ As the

Court has explained, “Remedies designed to end a continuing viola

tion of federal law are necessary to vindicate the federal interest in as

suring the supremacy of that law.” Green v. Mansour, 474 U.S. 64, 68

(1985). But “compensatory or deterrence interests are insufficient to

overcome the dictates of the Eleventh Amendment.” Id.; see also

Papasan v. M ain, 478 U.S. 265, 278 (1986).

In holding Section 1988 applicable to the states in Hutto,

the Court rested its decision squarely on this distinction. The Court

recognized that the Eleventh Amendment requirement of “an extraor

dinarily explicit statutory mandate” is limited to “retroactive liability

for prelitigation conduct rather than expenses incurred in litigation

seeking only prospective relief.” 437 U.S. at 695. The Court empha

sized that, since 1849, “[c]osts have traditionally been awarded without

regard for the States’ Eleventh Amendment immunity,” and that “[t]he

Court has never viewed the Eleventh Amendment as barring such

awards, even in suits between States and individual litigants.” Id. (cita

tions and footnote omitted).

2/ See also Quern v. Jordan, 440 U.S. 332 (1979) (mailing to inform class members of

legal rights in federal court); Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1977) ($6 million in pro

spective relief).

- 7 -

Accordingly, the Court held that the Eleventh Amendment

does not affect attorney’s fees under Section 1988, because they are

“part of the costs,” rather than retroactive liability:

Unlike ordinary “retroactive” relief such as damages or resti

tution, an award of costs does not compensate the plaintiff for

the injury that first brought him into court. Instead, the award

reimburses him for a portion of the expenses he incurred in

seeking prospective relief.

Id. at 695 n.24. And because the Eleventh Amendment does not apply,

attorney’s fees may be awarded against the states without an “explicit

statutory mandate” from Congress:

Just as a federal court may treat a State like any other litigant

when it assesses costs, so also may Congress amend its defini

tion of taxable costs and have the amended class of costs apply

to the States, as it does to all other litigants, without expressly

stating that it intends to abrogate the States’ Eleventh Amend

ment immunity.

Id. at 696.

The Court reaffirmed the vitality of the retroactive-pro

spective distinction in Quern v. Jordan, 440 U.S. 332, 344-45 n.16

(1979), and in Maher v. Gagne, 448 U.S. 122,131 n.14. (1980). See also

Pennhurst State School & Hosp. v. Halderman, 465 U.S. 89, 105-06

(1984) (“Pennhurst IF). No Eleventh Amendment decision of this

Court has required an “explicit statutory mandate” for prospective re

lief from a violation of federal law, or for awards of costs incurred in

obtaining such relief. 3/

3/ See Welch v. Texas Dep’t o f Highways & Pub. Transp., 107 S. Ct. 2941,2944 & n. 1

(1987) (action for damages under the Jones Act), Atascadero, 473 U.S. at 235 (“retroac

tive monetary relief under § 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973”); Pennhurst II, 465

U.S. at 91 (state law claim); Pennhurst State School & Hosp. v. Halderman, 451 U.S. 1,24

(1980) (“Pennhurst P’) (no violation of federal law; “Congress must express clearly its in

tent to impose conditions on the grant of federal funds”); Employees v. Department o f

Pub. Health & Welfare, 411 U.S. 279,281 (1973) (overtime compensation under Fair La

bor Standards Act of 1938).

- 8 -

This distinction negates any inference that the Eleventh

Amendment affects compensation for delay in payment of attorney’s

fees under Section 1988, Such compensation does not constitute ’’ret

roactive liability for prelitigation conduct.” Hutto, A2>1 U.S. at 695. It

does not “compensate the plaintiff for the injury that first brought him

into court.” Id. at 695 n.24. Merely ancillary to prospective substantive

relief, compensation for delay in a fee award is part of a remedy “de

signed to end a continuing violation of federal law,” Green v. Mansour,

474 U.S. 64, 68 (1985); it does not “compensate a party injured in the

past by an action . . . that was illegal.” Papascm v. Attain, 478 U.S. 265,

278 (1986).

The State, relying on Library o f Congress v. Shaw, 478 U.S.

310 (1986), contends that compensation for delay in payment of attor

ney’s fees is “damages,” not “costs” (Pet. Br. 19). But Library o f Con

gress does not support the State’s position. In that case, the Court ap

plied the “no-interest rule,” a longstanding rule of statutory construc

tion applicable in actions against the federal government. As the Court

stated the rule:

In the absence of express congressional consent to the award of

interest separate from a general waiver of immunity to suit, the

United States is immune from an interest award.

478 U.S. at 314. Under this standard, the Court held that the attorney’s

fees provision of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2003e-5(k), does not authorize

prejudgment interest on fees awarded against the federal government.

Although the statute authorizes “a reasonable attorney’s fee as part of

the costs” and provides that “the United States shall be liable for costs

the same as a private person,” the Court held that these references to

“costs” do not satisfy the stringent requirements of the no-interest

rule. As the Court observed, “Prejudgment interest. . . is considered

as damages, not a component of ‘costs.’” 478 U.S. at 321.

The distinction between “costs” and “damages,” while sig

nificant in Library o f Congress, is immaterial here. First, the issue here

is not whether compensation for delay in payment of costs is “costs” or

“damages.” The issue under the Eleventh Amendment is only whether

- 9 -

such compensation constitutes “retroactive liability for prelitigation

conduct,” Hutto, 437 U.S. at 695 — clearly it does not.

Second, Library o f Congress rested on the federal govern

ment’s sovereign immunity, which specifically includes an immunity

from the award of any costs, absent the government’s consent. See

United States v. Chemical Found., Inc., 272 U.S. 1, 20-21 (1926). The

statute at issue in Library o f Congress was thus a waiver of immunity

from “costs,” to be strictly construed. Library o f Congress, 478 U.S.

at 318. And the view of prejudgment interest as “damages, not a com

ponent of ‘costs,’” informed the Court’s determination that Congress’

general reference to “costs,” did not satisfy the stringent requirements

of the no-interest rule. Id. at 321.

Here, by contrast, the states do not enjoy any Eleventh

Amendment immunity from costs comparable to the sovereign immu

nity of the federal government. See Hutto, 437 U.S. at 695-97. A statute

providing for costs against the states is thus not a waiver to be narrowly

construed. Nor do the states enjoy the benefit of an Eleventh Amend

ment “no-interest rule” requiring the searching and technical exami

nation into the meaning of “costs” that was appropriate in Library o f

Congress. (See infra pp. 14-19.) Here it is more appropriate to recog

nize that interest on costs is not any part of damages on the underlying

claim; interest on costs is fairly only a part of costs.

2. The Eleventh Amendment Does

Not Require Specific Statutory

Reference to Compensation for

Delay in Section 1988

Even if compensation for delayed payment of attorney’s

fees were a retroactive liability —- though the attorney’s fees them

selves are not — that characterization would not affect the result in

this case. Even if the Eleventh Amendment would otherwise immunize

the states from compensation for delay in a fee award, Congress has

abrogated that immunity. In holding that the Eleventh Amendment

does not bar application of Section 1988 to the states, this Court reaf

firmed that “Congress has plenary power to set aside the States’ immu

- 10 -

nity from retroactive relief in order to enforce the Fourteenth Amend

ment.” Hutto, 437 U.S. at 693 (citing Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 427 U.S. 445

(1976)). The Court held that Congress, in enacting Section 1988, “un

doubtedly intended to exercise that power.” Id. at 693.

The State contends that this exercise of Congress’ power

may not be construed to embrace compensation for delay in payment,

absent a clear reference to such compensation in the statute itself (Pet.

Br. 12). While the State seeks to ground this requirement in the Elev

enth Amendment, none of this Court’s Eleventh Amendment deci

sions suggests such a rule. Of the cases on which the State relies, only

Atascadero held Congress’ intent insufficiently clear to abrogate the

Eleventh Amendment in enforcing the Fourteenth Amendment. And

the issue in Atascadero was whether a particular statute (Section 504 of

the Rehabilitation Act of 1973) authorized actions against the states at

all. Neither Atascadero nor any of this Court’s other decisions suggests

that the requirement of “unmistakably clear language” might apply in

determining the scope of a statute, such as Section 1988, that undis-

putedly abrogates the states’ Eleventh Amendment immunity.

The State cannot and does not dispute that Section 1988

applies against it. It cannot and does not dispute that the balance re

quired by the federal system has been struck in favor of fee awards

against the states when they have violated the civil rights laws. The

State contends only that one of the natural incidents of such awards —

compensation for delay in payment — occupies a special position and

requires separate, explicit congressional authorization. This conten

tion has no more basis in the Eleventh Amendment than it does in

logic.

This Court has never held that the Eleventh Amendment

requires a separate, express reference to prejudgment interest, or com

pensation for delay, before a state may be held liable for such pay

ments under a federal statute that otherwise lawfully applies to it. And

- 11 -

the lower courts have routinely made such awards under Section 1988,

as well as under other statutes that create rights against the states. 4/

Indeed, even where an express waiver of Eleventh Amendment immu

nity by the state is required, no separate, express waiver respecting

prejudgment interest has previously been considered necessary. See

Platoro, Ltd. v. Unidentified Remains o f a Vessel, 695 F.2d 893, 906 &

n.20 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 464 U.S. 818 (1983).

The state urges that “the Eleventh Amendment issue was

not raised” in cases such as these (Pet. Br. 10 n.6). Yet the one lower

court case the State cites against these precedents did not consider

“the Eleventh Amendment issue” at all. It merely assumed the exis

tence of an “Eleventh Amendment immunity from prejudgment inter

est on fee awards,” without explanation. Rogers v. Okin, 821 F.2d 22,27

(1st Cir. 1987).

Nothing in this Court’s Eleventh Amendment jurispru

dence supports the assumption in Rogers. In Welch v. Texas Depart

ment o f Highways & Public Transportation, 107 S. Ct. 2941 (1987), the

Court elaborated the rationale behind the requirement that Congress

express its intention to abrogate the Eleventh Amendment “in unmis

takable language in the statute itself’:

We have been unwilling to infer that Congress intended to ne

gate the States’ immunity from suit in federal court, given the

“vital role of the doctrine of sovereign immunity in our federal

system.” . . . Moreover, the courts properly are reluctant to in

fer that Congress has expanded our jurisdiction.

4/ See, e.g., Lightfoot v. Walker, 826 F.2d 516 (7th Cir. 1987) (Section 1988); Gren

der s Den, Inc., v. Larkin, 749 F.2d 945 (1st Cir. 1984) (same); Ramos v. Lamm, 713 F.2d

546 (10th Cir. 1983) (same); Graves v. Barnes, 700 F.2d 220,224 (5th Cir. 1983) (fee award

under 42 U.S.C. § 19731(e)); Behlar v. Smith, 719 F.2d 950 (8th Cir. 1983) (backpay award

under Title VII), cert, denied, 466 U.S. 958 (1984); Chesser v. Illinois, 1987 U.S. Dist.

LEXIS 7398, at 12 (N.D. 111. Aug. 11,1987) (same); Gelofv. Papineau, 648 F. Supp. 912,

929,931 (D. Del. 1986) (same), a ff d in part, vacated in part on other grounds, 829 F.2d 452

(3d Cir. 1987); Liberies v. Daniel, 26 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 547, 26 Empl. Prac.

Dec. (CCH) 11 31,816 (N.D. 111. March 20,1981) (same), affd in part, rev’d in part on other

grounds, 709 F.2d 1122 (7th Cir. 1983).

- 12 -

Id. at 2946 (quoting Petmhurst II, 465 U.S. at 99). 'These considerations

properly require a searching inquiry before courts conclude that Con

gress intended a particular enactment to impose retroactive liability

on the states. As this Court has recognized, the requirement of a for

mal indication of Congress’ intent “insures that Congress has not im

posed ‘enormous fiscal burdens on the States’ without careful

thought”. Hutto, 437 U.S. at 697 n.27 (quoting Employees v. Depart

ment o f Pub. Health & Welfare, 411 U.S. 279, 284 (1973)).

But the needs of the federal system certainly do not suggest

that compensation for delay should occupy any special place under the

Eleventh Amendment, any more than any other particular that “a rea

sonable attorney’s fee” may embrace. The State contends that includ

ing compensation for delay in fee awards would “impose what could be

a substantial financial obligation on the States” (Pet. Br. 22). Admit

tedly, the state treasuries will pay somewhat greater awards if they

must compensate for delay. But the same is true “whenever a filing fee,

or a new item, such as an expert witness’ fee, is added to the category of

taxable costs.” Hutto, 437 U.S. at 697. And “it would be absurd to re

quire an express reference to state litigants” for each such item. Id.

at 696-97. Indeed, the State’s contention is belied by the circumstances

of this case. The total fee award here — approximately $4 million for

nearly a decade of litigation — is about one percent of the cost of the

substantive remedies ordered to date. The compensation for delay is

only a fraction of that one percent. To the State, the additional burden

is inconsequential — only to the attorneys is it significant.

Nor does the inclusion of compensation for delay consti

tute an expansion of the federal courts’ jurisdiction. Congress has by

statute given the federal courts jurisdiction to entertain applications

for costs, including attorney’s fees, against the states. It cannot be a

further expansion of jurisdiction to consider, in assessing such awards,

all the factors normally required by the statute’s purposes, including

delay in payment.

- 13 -

B. Library of Congress v. Shaw

Is Not Controlling

The State contends that Library o f Congress v. Shaw, 478

U S. 310 (1986), proscribes compensation for delayed payment in any

fee award against a state under Section 1988. As the State would have

it, the no-interest rule applied in Library o f Congress is a principle of

Eleventh Amendment jurisprudence. That view, however, finds no

support in Library o f Congress, which has nothing to do with the Elev

enth Amendment, does not mention the Eleventh Amendment and

does not rely on any precedent construing the Eleventh Amendment.

1. The No-Interest Rule Cannot

Be Extended to the Eleventh

Amendment

In Library o f Congress, the Court traced the history of the

no-interest rule to the “historical view that interest is an element of

damages separate from damages on the substantive claim,” and the

corollary common-law rule that, because interest was “generally pre

sumed not to be within the contemplation of the parties,” courts in

England “allowed interest by way of damages only when founded upon

agreement of the parties.” 478 U.S. at 314-15 (footnote omitted). The

Court noted that the common-law requirement of an agreement

gradually faded in suits between private parties, but “assumed special

force when applied to claims for interest against the United States,”

since “[a]s sovereign, the United States, in the absence of its consent, is

immune from suit.” Id. at 315. As the Court stated, “This basic rule of

sovereign immunity, in conjunction with the requirement of an agree

ment to pay interest, gave rise to the rule that interest cannot be recov

ered unless the award of interest was affirmatively and separately con

templated by Congress.” Id. This explanation of the no-interest rule

demonstrates its inapplicability here.

First, the common-law requirement of an agreement to pay

interest can have no effect where, as here, Congress has acted to en

force the Fourteenth Amendment. When Congress has done so, the

states’ consent to suit is irrelevant:

- 14 -

Congress can abrogate the Eleventh Amendment without the

States’ consent when it acts pursuant to its power “‘to enforce,

by appropriate legislation’ the substantive provisions of the

Fourteenth Amendment.”

Welch v. Texas Dep’t o f Highways & Pub. Transp., 107 S. Ct. 2941,2946

(1987) (quoting Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 427 U.S. 445, 456 (1976)).

Congress undoubtedly had the power, in Section 1988, to

require fee awards, including compensation for delay, with or without

states agreement. The only question is whether Congress made that

choice. All the available evidence indicates it did. {See infra pp. 21-26.)

Second, the “basic rule of sovereign immunity” relied on in

Library o f Congress is not applicable to actions governed by the Elev

enth Amendment. It derives from the common-law doctrine under

which the sovereign was immune, absent its consent, “from suit in its

own courts.” Nevada v. Hall, 440 U.S. 410, 414 (1979); see also The Si

ren, 7 Wall. (74 U.S.) 152, 154 (1868) (“It is a familiar doctrine of the

common law, that the sovereign cannot be sued in his own courts with

out his consent.”). That common-law doctrine has origins — and con

tours — very different from those of the constitutional immunity em

bodied in the Eleventh Amendment.

The common-law doctrine “had its origins in the feudal

system,” under which “no lord could be sued by a vassal in his own

court, but each petty lord was subject to suit in the courts of a higher

lord. Since the King was at the apex of the feudal pyramid, there was no

higher court in which he could be sued.” Nevada v. Hall, 440 U.S. at 415

(citing F. Pollock & F. Maitland, History o f English Law 518 (2d ed.

1899); Engdahl, Immunity and Accountability for Positive Government

Wrongs, 44 U. Colo. L. Rev. 1, 2-5 (1972)). The doctrine has been ex

plained also as embodying a fundamental attribute of sovereignty, “the

right to determine what suits may be brought in the sovereign’s own

courts.” Id. Thus, Justice Holmes explained sovereign immunity as

based “on the logical and practical ground that there can be no legal

right as against the authority that makes the law on which the right

depends.” Kawananakoa v. Polyblank, 205 U.S. 349, 353 (1907),

- 15 -

quoted in Nevada v. Hall, 440 U.S. at 415-16. Accordingly, the

common-law doctrine of sovereign immunity does not apply to actions

against a sovereign in the courts of another, co-equal (or “higher”) sov

ereign.

The Eleventh Amendment, by contrast, embodies a consti

tutional principle that is necessarily subject to the demands of our fed

eral system. In particular, the immunity conferred by the Eleventh

Amendment must be reconciled with “the need to promote the vindi

cation of federal rights.” Pennhurst II, 465 U.S. at 105; see also

Papasan v. Attain, 478 U.S. 265, 276-78(1986); Green v. Mansour, 474

U.S. 64, 68 (1985). There is thus no reason to assume that immunity

under the Eleventh Amendment is coextensive with the sovereign’s

common-law immunity from suit in its own courts.

Nothing in the “structure and requirements of the federal

system,” Welch, 107 S. Ct. at 2953, requires this Court to read a no

interest rule into the Eleventh Amendment. Once Congress has deter

mined, as it did with Section 1988, that a particular federal policy mer

its enforcement against the states, Congress has declared that the

usual federal-state balance does not obtain. And the requirements of

the federal system dictate that the state is, to that extent at least, no

longer sovereign, but is subject to the same rights and liabilities as

other parties. The applicable principle of federalism is that articulated

in Fairmont Creamery Co. v. Minnesota, 275 U.S. 70 (1927):

Though a sovereign, in many respects, the state when a party to

litigation in this Court loses some of its character as such.

Id. at 74. Specifically in the matter of costs — the issue under Section

1988 — “a federal court may treat a State like any other litigant.”

Hutto, 437 U.S. at 696.

Third, even if the constitutional immunity of the states un

der the Eleventh Amendment were coextensive with their common-

law immunity as sovereigns in their own courts, that would not require

application of a no-interest rule here. Although common-law notions

of sovereign immunity are a necessary predicate to the no-interest

- 16 -

rule, it is far from clear that the rule is an inescapable feature of

common-law sovereign immunity. The State of Missouri, for example,

does not apply such a rule in its own courts. While Missouri has a gen

eral statute authorizing awards of prejudgment interest, the statute

does not explicitly provide for such awards against the state. Mo. Rev.

Stat. § 408.020 (1986). 5/ The Missouri courts, however, apply it

against the State.6 7/ The no-interest rule, which Missouri itself does

not credit, cannot reasonably be considered so basic to sovereign im

munity as to warrant being enshrined in the Constitution. V

5/ Section 408.020 provides:

Creditors shall be allowed to receive interest at the rate of nine percent per an

num. when no other rate is agreed upon, for all moneys after they become due

and payable, on written contracts, and on accounts after they become due and

demand of payment is made; for money recovered for the use of another, and

retained without the owner's knowledge of the receipt, and for all other money

due or to become due for the forbearance of payment whereof an express prom

ise to pay interest has been made.

6/ Denton Constr. Co. v. Missouri State Highway Comm’n, 454 S.W.2d 44 (Mo.

1970); Steppelman v. State Highway Comm ’n., 650 S. W.2d 343,345 (Mo. App. 1983); Ber

nard McMenamy Contractors, Inc. v. Missouri State Highway Comm’n, 582 S.W.2d 305

(Mo. App. 1979).

71 Alternatively, the Missouri decisions awarding prejudgment interest against the

State may be viewed as construing § 408.020 to waive any no-interest immunity that

might otherwise exist. Specifically, an award of attorney’s fees meets the standards of

Section 408.020. See Laughlin v. Boatmen’s Nat'l Bank, 354 Mo. 467, 189 S.W.2d 974

(Mo. 1945) (unliquidated claims for legal services); Whalen, Murphy, Reid v. Estate o f

Roberts, 711 S.W.2d 587,590 (Mo. App. 1986) (error not to award prejudgment interest

on an attorney’s fees claim); Knight v. DeMarea, 670 S.W.2d 59 (Mo. App. 1984). And

where Section 408.020 applies, its provisions are mandatory; Denton Constr. Co. v. Mis

souri State Highway Commit, 454 S. W. 2d (Mo. 1970); St. Joseph Light & Power Co. v.

Zurich Ins. Co., 698 F.2d 1351,1355 (8th Cir. 1983); see also Slay Warehousing Co. v. Reli

ance Ins. Co., 489 F.2d 214, 215 (8th Cir. 1974).

While a waiver of immunity in Missouri’s own courts would be insufficient “to

subject [it] to suit in federal court,” Atascadero, 473 U.S. at 241 (emphasis omitted), Mis

souri is already subject “to suit in federal court,” by virtue of the important federal poli

cies embodied in the Fourteenth Amendment and the statutes implementing it.Thus,

even if the Eleventh Amendment otherwise entailed an immunity from interest, feder

alism concerns would not justify its invocation by a defendant like Missouri, which has

waived the immunity in cases where no national policy is involved.

- 17 -

2. The No-Interest Rule Would

Be an Unreasonable Rule of

Statutory Construction Here

Library o f Congress in the last analysis did no more than

apply an established principle of statutory construction in its tradi

tional context. To apply the no-interest rule here would be a very dif

ferent matter.

Library o f Congress rested explicitly on a long-established

and oft-repeated fixture of our national jurisprudence:

For well over a century, this Court, executive agencies, and

Congress itself have recognized that federal statutes cannot be

read to permit interest to run on a recovery against the United

States unless Congress affirmatively mandates that result.

478 U.S. at 316. The Court cited numerous decisions, prior to the en

actment of Title VII, the statute in issue, affirming and reaffirming the

requirements of the no-interest rule. See id. at 315-17. The Court cited

numerous opinions of Attorneys General, over the past 170 years, ar

ticulating the same rule. Indeed, the Court noted Congress’ own recog

nition of the no-interest rule: “When Congress has intended to waive

the United States’ immunity with respect to interest, it has done so ex

pressly.” Id. at 318 (footnote omitted).

Congress acted against a very different background when

it authorized the award of civil rights attorney’s fees against the states.

Congress specifically relied upon the fact that “the 11th Amendment is

not a bar to the awarding of counsel fees against state governments.”

H.R. Rep. No. 1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 7 n.14 (1976) (“House Re

port”) (citing Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, A ll U.S. 445 (1976)). Congress had

no reason to suspect that a separate, express reference to interest or

compensation for delay was necessary. There is no reason to ignore

- 18

Congress’ purpose solely because it was not expressed in a particular

form — a form that this Court has never previously required. 8/

C. This Court Should Overrule

Hans v. Louisiana if It Reaches

the Question

If this Court were to conclude, with the State, that the Elev

enth Amendment bars compensation for delay, it would then face the

question whether the Eleventh Amendment applies in this case. The

language of the amendment could scarcely be simpler, plainer or

clearer: it prohibits only actions “against one of the United States by

Citizens of another State, or by Citizens or Subjects of any Foreign

State.” U.S. Const, amend. XI. This action, however, involves claims

by citizens of a state against their own state.

In Welch, four members of this Court reaffirmed the hold

ing of Hans v. Louisiana, 134 U.S. 1 (1890), that the Eleventh Amend

ment embodies a principle of state sovereign immunity broader than

its terms, extending to actions by a citizen of a state against that state.

But four other members of the Court reaffirmed the view they ex

pressed in Atascadero, 473 U.S. at 247-302 (Brennan, J., dissenting),

that Hans misconstrued the Eleventh Amendment. Welch, 107 S. Ct. at

2958-70. They argued that the Eleventh Amendment does not bar

claims under the federal question and admiralty jurisdictions or ac

tions by a citizen against his or her own state. Id. Justice Scalia found it

unnecessary to consider whether Hans was correctly decided, saying

that Congress had enacted the statute in question (the Jones Act)

8/ Even if the no-interest rule applied under the Eleventh Amendment, it would

not apply here, because no interest was awarded. Unlike the award in Library o f Con

gress, the award here was based on current market rates; it was not adjusted by an overall

factor to compensate for all losses due to delay. Indeed, the record here shows that use of

hourly rates could not fully compensate for lost interest (Tr. 113-16; PI. Ex. 5, at 10;

Ward Aff., filed Jan. 16,1987). While the Court in Library o f Congress stated that awards

of interest, under any name, are forbidden absent the consent of the United States, the

present case does not involve “simply. . . devising a new name for an old institution.”

Library o f Congress, 478 U.S. at 321. Here, the method used — not just the name applied

— was different from awarding interest. And this method, basing the lodestar on current

market rates, was not before the Court in Library o f Congress.

- 19 -

against the background of Hans and therefore could not have intended

to grant to federal courts jurisdiction over actions against the states.

Id. at 2957-58.

If the Court were now to conclude that the Eleventh

Amendment includes a no-interest rule, this case would necessarily

raise the question that Justice Scalia did not reach. In enacting Section

1988, Congress clearly intended that it apply against the states, as this

Court has held. Rather than acting within the confines of Hans, Con

gress explicitly relied on Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 427 U.S. 445 (1976), which

held that “the Eleventh Amendment, and the principle of state sover

eignty which it embodies . . . are necessarily limited by the enforce

ment provisions of § 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment.” Id. at 456 (cit

ing Hans); see House Report at 7 n.14.

In urging the Court to overrule Hans, we have little to add

to Justice Brennan’s dissenting opinions m Atascadero and Welch. We

do note, however, with all respect, that the plain language of the Elev

enth Amendment is impossible to square with the holding in Hans. In

its extraordinarily precise specificity — prohibiting suits “against one

of the United States by Citizens of another State, or by Citizens or Sub

jects of any Foreign State” — it stands in stark contrast to the broad

language of the first ten amendments. That specificity suggests an

equally specific intent: to override the holding in Chisholm v. Georgia,

2 Dali. (2 U.S.) 419 (1793), which construed Article III to confer juris

diction of precisely such suits, even where jurisdiction would not other

wise obtain. See Welch, 107 S. Ct. at 2964-68 (Brennan, J., dissenting).

We note also that the framers of the Eleventh Amendment

would not likely have considered the states to need protection from

Congress or, therefore, from the federal courts under the federal ques

tion jurisdiction. Congress was limited to enumerated powers, and the

Tenth Amendment reserved to the states, and to the people, all powers

not conferred on Congress. As this Court has recognized, the structure

of the federal government provided whatever protection the states

might need from the federal legislature:

It is no novelty to observe that the composition of the Federal

Government was designed in large part to protect the States

- 20 -

from overreaching by Congress. The Framers thus gave the

States a role in the selection both of the Executive and the Leg

islative Branches of the Federal Government. The States were

vested with indirect influence over the House of Representa

tives and the Presidency by their control of electoral qualifica

tions and their role in Presidential elections . . . They were

given more direct influence in the Senate, where each State re

ceived equal representation and each Senator was to be se

lected by the legislature of his State.

Garcia v. San Antonio Metro. Transit Auth., 469 U.S. 528, 550-51

(1985); see also id. at 549 (“’Interference with the power of the states

was no constitutional criterion of the power of Congress.’”) (quoting 2

Annals of Cong. 1897 (1791) (Madison)).

If the Constitution leaves Congress free to regulate the

states under its commerce power — if the political process is pre

sumed to afford the states any needed protection from such regula

tion — then surely the framers of the Eleventh Amendment did not

believe that the same political process would be inadequate to protect

the states, to the extent necessary, from claims arising under the Con

stitution and laws of the United States.

D. Section 1988 Authorizes

Compensation for Delay in Fee

Awards Against the States

Since Congress undisputedly has the power to require that

the states compensate for delay in payment under Section 1988, and

since the Eleventh Amendment imposes no special standard in deter

mining whether Congress exercised that power, the ultimate question

is whether Congress has done so.

The anwer is clear. As this Court has observed, Section

1988 “primarily applies to laws passed specifically to restrain state ac

tion.” Hutto, 437 U.S. at 694. It “has a history focusing directly on the

question of state liability.” Id. at 698 n.31. According to the House

Report:

- 21 -

The greater resources available to governments provide an am

ple base from which fees can be awarded to the prevailing

plaintiff in suits against governmental officials or entities.

House Report at 1, quoted in Hutto, 437 U.S. at 694. To hold that Sec

tion 1988 applies against the states with any less force than against

other parties would be to ignore Congress’ intent. And Congress’ pur

pose in Section 1988 - to attract first-quality lawyers to civil rights

cases by providing fully compensatory fees - cannot be accomplished

without compensation for delay.

Congress enacted Section 1988 in recognition of the impor

tant role of private plaintiffs in civil rights enforcement — a recogni

tion that plaintiffs with meritorious civil rights claims “appear before

the court cloaked in a mantle of public interest.” Id. at 6. “The pur

pose of § 1988 is to ensure ‘effective access to judicial process’ for per

sons with civil rights grievances.” Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424,

429 (1983) (citing House Report at 1).

Congress considered fee awards an “essential remedy,” be

cause civil rights plaintiffs often have little or no money with which to

hire a lawyer. See S. Rep. No. 1011,94th Cong., 2d Sess. 2 (1976) (“Sen

ate Report”). In addition, the remedies in civil rights litigation may be

“nonpecuniary in nature.” Id. at 6. Such remedies provide no fund

from which to pay a lawyer. See generally City o f Riverside v. Rivera,

A ll U.S. 561, 577-78 (1986). Without fee awards, private enforcement

of the civil rights laws would thus be an empty promise — private citi

zens would have no “meaningful opportunity to vindicate the impor

tant Congressional policies which these laws contain.” Senate Report

at 2.

In view of the critical importance of private civil rights en

forcement, it is necessary to attract first-rate lawyers to the task —

persons deprived of their civil rights should not be sent to the back of

the bus to find a lawyer — and Congress so understood. Congress

sought “to attract competent counsel in cases involving civil and con

stitutional rights.” House Report at 9. To accomplish this, Congress

determined to compensate prevailing counsel in civil rights cases just

- 22 -

as in other complex litigation on behalf of paying clients. Fee awards

under Section 1988 must be similar to what “is traditional with attor

neys compensated by a fee-paying client.” Senate Report at 6. Ac

cordingly:

It is intended that the amount of fees awarded . . . be governed

by the same standards which prevail in other types of equally

complex Federal litigation, such as antitrust cases . . . .

Id., quoted in Blum v. Sternon, 465 U.S. 886, 893 (1984); see also House

Report at 8-9. As this Court held in Blum:

The statute and legislative history establish that “reasonable

fees” under § 1988 are to be calculated according to the pre

vailing market rates in the relevant community.

465 U.S. at 895. And where “a plaintiff has obtained excellent results,

his attorney should recover a fully compensatory fee.” Hensley, 461

U.S. at 435.

These principles require that fee awards include, in appro

priate circumstances, an element of compensation for delay in pay

ment. Lawyers typically bill their clients, and expect payment, on a cur

rent basis, monthly or quarterly. Indeed, lawyers are free to require

advance payment of a fee. Model Rules o f Professional Conduct,

Rule 1.5 comment (ABA 1983). In contrast, an attorney enforcing the

civil rights laws on behalf of an impecunious client must await pay

ment until his or her client becomes a “prevailing party.” And, of

course, compensation delayed is compensation diminished. As infla

tion erodes the real value of currency, delayed payment has less value

than prompt payment in the same amount. Moreover, obtaining

money — and the use of it — earlier rather than later has a recognized

economic value; in addition to losses from inflation, delayed payment

entails a “real opportunity cost of capital.” Library o f Congress, 478

U.S. at 322 n.7 (citing R. Posner, Economic Analysis o f Law 180 (3d ed.

1986)). As Judge Posner has put it:

The usual assumption in economics as in life is that a dollar

today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow, both because it

- 23 -

can be invested and earn interest and because the future is un

certain.

Heiar v. Crawford County, 746 F.2d 1190,1203 (7th Cir. 1984), cert, de

nied, 472 U.S. 1027 (1985). Accordingly, this Court has recognized in

other contexts that full compensation must include compensation for

delay in payment. 9/

These concerns take on special importance for fee awards

under Section 1988, because civil rights litigation often takes many

years before counsel receive any payment. 10/ A prevailing civil rights

plaintiffs lawyer, absent compensation for delay, would receive less

compensation — in most cases a great deal less — than he or she could

have received doing the same work for a currently-paying client at rea

sonable market rates. And that result would flatly contravene Con

gress’ objective that these lawyers receive what “is traditional with at

torneys compensated by a fee-paying client.” Senate Report at 6. A

fee award diluted by the passage of time cannot be “fully compensa

tory.” Hensley, 461 U.S. at 435.

The legislative history of Section 1988 demonstrates that

awards must account for the hardship that results from delayed pay

ment. The Senate Report cited Bradley v. Richmond School Board, 416

U.S. 696 (1974), in which this Court upheld an interim fee award and

noted:

To delay a fee award until the entire litigation is concluded

would work substantial hardship on plaintiffs and their coun

sel, and discourage the institution of actions despite the clear

congressional intent to the contrary. . . .

9/ Loefler v. Frank, 108 S. Ct. 1965, 1971 (1988) (backpay award under Title VII);

General Motors Corp. v. Devex Corp., 461 U.S. 648 (1983) (damages for patent infringe

ment); Albrecht v. United States, 329 U.S. 599, 605 (1947) (“just compensation” under

Fifth Amendment); Smyth v. United States, 302 U.S. 329, 353-54 (1937) (same).

10/ See, e.g., Hutto, 437 U.S. at 681 (9 years); Lightfoot v. Walker, 826 F.2d 516, 517

(7th Cir. 1987) (14 years); Northcrvss v. Board ofEduc., 611 F.2d 624,628 (6th Cir. 1979)

(19 years), cert, denied, 447 U.S. 911 (1980); Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of

Educ., 66 F.R.D. 483, 484 (W.D.N.C. 1975) (7 years).

- 24 -

Id. at 723, cited in Senate Report at 5. And so, in discussing the timing

of awards under Section 1988, the Senate Report stated that “[i]n ap

propriate circumstances, counsel fees under [Section 1988] may be

awarded pendente lite.” Senate Report at 5.

If the timing of fee awards must take on flexibility to ac

count for the “substantial hardship” that may result from delayed

compensation, then it begs credulity to suggest that the term “reason

able attorney’s fee” — which by its nature mandates discretion in the

district courts and case-by-case determination, see Hensley, 461 U.S,

at 429, 437 — must be read to ignore that same hardship.

In applying Section 1988, the lower courts have routinely

provided compensation for delay in payment. 11/ As the Fourth Cir

cuit has stated:

Civil Rights litigation often spans several years, and conse

quently compensation under § 1988 often occurs long after the

relevant services have been rendered. This delay in payment of

attorney’s fees “obviously dilutes the eventual award and may

convert an otherwise reasonable fee into an unreasonably low

one”.

* * *

Delay necessarily erodes the value of a fee that would have

been reasonable if paid at the time the services were rendered.

Consequently, an award based upon historic rates which does

not take delayed payment into account will not be a fully com

pensatory fee.

Daly v. Hill, 790 F.2d 1071, 1081 (4th Cir. 1986) (quoting Johnson v.

University College, 706 F.2d 1205,1210 (11th Cir.), cert, denied, 464 U.S.

994 (1983)).

11/ See, e.g., Grendel's Den, Inc. v. Larkin, 749 F.2d 945, 951,955 (1st cir. 1984); New

York State Ass’n for Retarded Children v. Carey, 711 F.2d 1136, 1152 (2d Cir. 1983);

Northcross v. BoardofEduc., 611 F.2d 624,640 (6th Cir. 1979), cert, denied, 447 U.S. 911

(1980); Lightfoot v. Walker, 826 F.2d 516,523 (7th Cir. 1987); Sisco v.J.S. Alberici Constr.

Co., 733 F.2d 55, 59 n.3 (8th Cir. 1984); Jordan v. Multnomah County, 815 F. 2d 1258,

1262-63 n.7 (9th Cir. 1987); Ramos v. Lamm, 713 F.2d 546,555 (10th Cir. 1983); Gaines v.

Dougherty County Bd. ofEduc., 775 F.2d 1565, 1572 (11th Cir. 1985) (per curiam).

- 25 -

This Court has also recognized the propriety of these ap

proaches, albeit in dictum:

When plaintiffs’ entitlement to attorney’s fees de

pends on success, their lawyers are not paid until a favorable

decision finally eventuates, which may be years later, as in this

case. Meanwhile, their expenses of doing business continue

and must be met. In setting fees for prevailing counsel, the

courts have regularly recognized the delay factor, either by

basing the award on current rates or by setting the fee based on

historical rates to reflect its present value. . . . Although delay

and the risk of nonpayment are often mentioned in the same

breath, adjusting for the former is a distinct issue that is not

involved in this case. We do not suggest, however, that adjust

ments for delay are inconsistent with the typical fee-shifting

statute.

Pennsylvania v. Delaware Valley Citizens Council, 107 S. Ct. 3078, 3081

(1987) (citations omitted); see also id. at 3099 (Blackmun, J., dissent

ing).

II.

SECTION 1988 AUTHORIZES THE AWARD OF

FEES FOR PARALEGALS AT MARKET RATES

In Blum v. Stenson, 465 U.S. 886 (1986), this Court held that

fees under Section 1988 “are to be calculated according to the prevail

ing mandet rate in the relevent community.” Id. at 895. Accordingly,

the district court in this case awarded Mr. Benson $225,085, and the

LDF $431,338, in paralegal and law clerk fees, based on hourly rates of

$35 for law clerks (law students), $40 for paralegals and $50 for recent

law school graduates. Mr. Benson’s law clerks and paralegals had

worked 8,108 hours on the case; the LDF’s law clerks, paralegals and

recent law school graduates had worked 15,517 hours. The court of ap

peals affirmed the award, saying that “market considerations should

govern, but it is not necessary to adopt an ironclad rule in this case.”

Jenkins v. Missouri, 838 F.2d 260, 266 (8th Cir. 1988). Numerous other

- 26 -

lower courts have held that market considerations should govern para

legal fees. 12/

The paralegals in this case performed a variety of tasks

that traditional clerical employees could not handle — tasks that

would otherwise have fallen to lawyers. The two paralegals whose work

made up 80 percent of Mr. Benson’s paralegal claim were both college

graduates. One had a B.A. in paralegal studies; the other has since

graduated from law school. In this litigation, they assisted with docu

ment discovery and established the filing system. They interviewed wit

nesses. They summarized deposition transcripts and exhibits for ex

pert witnesses. They prepared graphs, charts and exhibits for trial.

They assisted at trial by logging the exhibits. (Johnson Aff., filed

Jan. 16, 1987; Zinn Aff., filed Jan. 16, 1987.)

The State does not dispute that the work of paralegals in

this case was reasonably necessary to prosecution of the action and

contributed significantly to the result. The State does not dispute that

the paralegal rate awarded reflected the market rate in the relevant

community; it was in fact “a little bit below” the Kansas City average

(Tr. 110). Nevertheless, the State contends that the paralegal work here

should be compensated not at “prevailing market rates” — the meas

ure prescribed by this Court, Blum, 465 U.S. at 895 — but at “cost.”

There is no basis for such a result.

12/ See, e.g., Spanish Action Comm. v. City o f Chicago, 811 F.2d 1129,1138 (7th Cir.

1987); Save Our Cumberland Mountains, Inc. v. Model, 826 F.2d 43, 54 & n.7 (D.C. Cir.