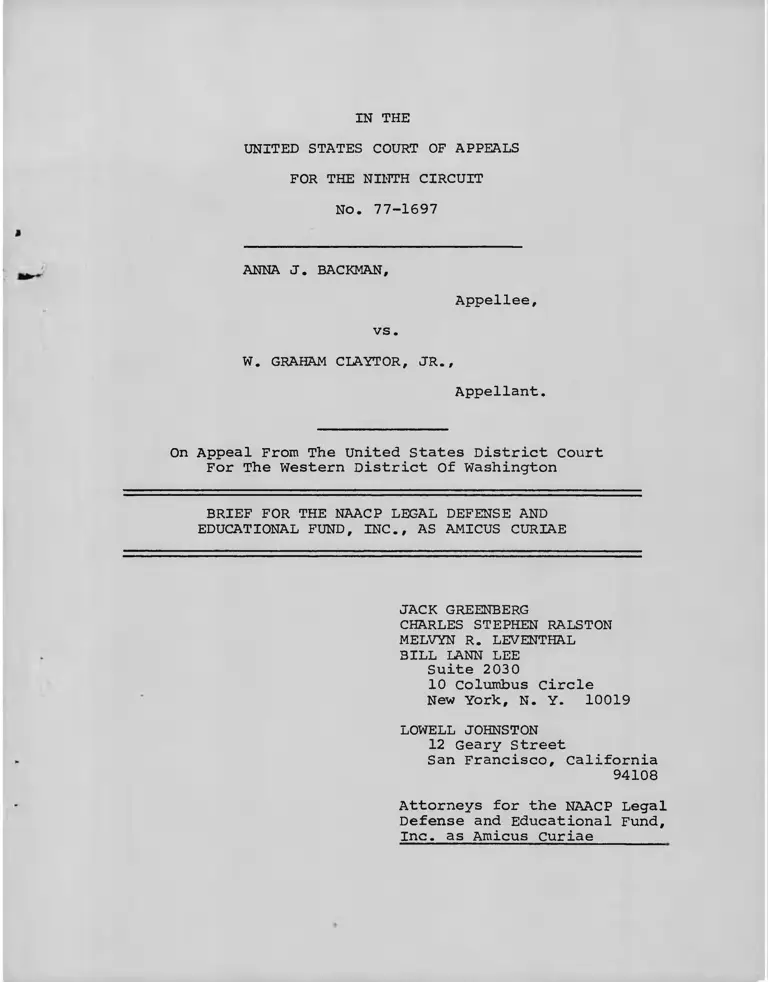

Backman v. Claytor Brief for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

December 28, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Backman v. Claytor Brief for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund as Amicus Curiae, 1976. 5d183e85-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4b435ce0-c28c-4f33-aa9a-60206d89f767/backman-v-claytor-brief-for-the-naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

No. 77-1697

ANNA J. BACKMAN,

Appellee,

vs .

W. GRAHAM CLAYTOR, JR.,

Appellant.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Western District Of Washington

BRIEF FOR THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

BILL LANN LEE

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

LOWELL JOHNSTON

12 Geary Street

San Francisco, California

94108

Attorneys for the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc, as Amicus curiae

INDEX

Page

Interest of Amicus ................................ 1

» ARGUMENT ........................................... 3

Summary of Argument..................... 3

Introduction ............................ 5

1. The Lower Court's Decision Should Be

Affirmed In Light Of The Recent

Decisions Of The D.C. And Fourth

Circuit ................................. 11

A. Plaintiff Backman Was "Prevailing

Party" In Judicial Proceedings ..... 12

B. Plaintiff Backman Was "Prevailing

Party" In Administrative-Judicial

Proceedings ......................... 21

II. Assuming Arguendo That The Suit Was

Filed For Attorneys Fees Denied In

Administrative Proceedings Alone, The

D.C. And Fourth Circuit Decisions Still

Control .................................. 25

III. The Availability Of Attorney's Fees For

Prevailing Complainants Is A Practical

Necessity In Federal Title VII

Administrative Proceedings ............. 31

CONCLUSION ......................................... 39

- x -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405

(1975) ............................................... 2, 30, 33

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36

(1974) ............................................... 7

Allen v. Veterans Administration, 542 F.2d 176

(3rd Cir. 1976) ..................................... 6

Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. v. Wilderness Society,

421 U.S. 240 (1975) .................................. 9

Barrett v. U.S. Civil Service Commission, 69

F.R.D. 544 (D.D.C. 1975) ............................. 3, 6, 36

Bell v. Schlesinger, _____ F.2d _____ (D.C. Cir.

1977) ................................................ 15

Blackmon v. McLucas, 13 EPD 511,451 (D.D.C. 1976) . 6

Brown v. General Services Administration, 425

U.S. 820 (1976) ............................... 5, 10, 15,

22, 31

Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840 (1976),

reversing. 515 F.2d 251 (9th Cir. 1975) .... . 3, 6, 22, 24,

25, 28

Coles v. Penny, 531 F.2d 609 (D.C. Cir. 1976) .... 6

Culpepper v. Reynolds Metal Co., 421 F.2d 888 (5th

Cir. 1971) ........................................... 10

Day v. Mathews, 530 F.2d 1083 (D.C. Cir. 1976) ... 6, 25

Eastland v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 553 F.2d

364 (5th Cir. 1977) ................................. 6

Ellis v. Naval Air Rework Facility, 404 F. Supp.

377 (N.D. Cal. 1976) ................................ 3

Evans v. Sheraton Park Hotel, 503 F.2d 177 (D.C.

Cir. 1974) ............................ 19

- ii -

Page

Fitzgerald v_ U.S. Civil Service Commission, _____ 29 30

F .2d _____ (D.C. Cir. 1977) ....................

Foster v. Boorstin, _____ F.2d _____ (D.C. Cir.

1977) ............................................ Passim

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747

(1976) ........................................... 2, 30

Garner v. E.I. Dupont, 538 F.2d 611 (4th Cir.

1976) ............................................ 6

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) .... 2

Grubbs v. Butz, 514 F.2d 1323 (D.C. Cir. 1975) .... 6

Hackley v. Roudebush, 520 F.2d 108 (D.C. Cir.

1975) ............................................ 3, 22, 25,

28, 31

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

States, 45 U.S.L.W. 4506 (decided May 31,

1977) ............................................ 30

Johnson v. Froehlke, 5 EPD 58,638 (D. Md. 1973) ... 6

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 488 F.2d

714 (5th Cir. 1974) ............................. 10

Johnson v. United States, 554 F.2d 632 (4th

Cir. 1977), affirming. 12 EPD 5

(D. Md. 1976) ................................... Passim

Koger v. Ball, 497 F.2d 702 (4th Cir. 1974) ...... 5

Local 1401 v. N.L.R.B., 463 F.2d 316

(D.C. Cir. 1972) ..................... .......... 24

McMullen v. Warner, 12 EPD 511/107 (D.D.C. 1976) .. 23, 32

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) .............. 2

NLRB v. Food Store Employees, 417 U.S. 1 (1974) ... 30

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., 433

F .2d 421 (8th Cir. 1970) ........................ 18, 19

Parker v. Califano, _____ F.2d _____ (D.C. Cir.

1977), affirming, 411 F. Supp. 1059 (D.D.C.

1976) ..................................... ...... Passim

- iii -

Page

Parks v. Dunlop, 517 F.2d 785 (5th Cir. 1975) .... 6

Phillips v. Martin Marietta corp., 400 U.S. 542

(1971) ........................................... 2

Place v. Weinberger, 426 U-S. 932 (1976), vacating-

and remanding in light of confession of error,

497 F .2d 412 (6th Cir. 1974) ................... 5

Reyes v. Mathews, 13 EPD 511,365 (D.D.C. 1976) ___ 22, 23

Richardson v. Wiley, 13 EPD 511,349 (D.D.C. 1976) . 18

Runyan v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976) ............ 9

Smith v. Kleindienst, 527 F.2d 853 (D.C. Cir. 1975)

(unpublished opinion), affirming, 8 FEP Cases

752 (D.D.C. 1974) ............................... 11

Swain v. Hoffman, 547 F.2d 921 (5th Cir. 1977) ___ 3

Turner v. Federal Communications Commission, 514

F .2d 1354 (D.C. Cir. 1975) ..................... 29, 30

Williams v. Saxbe, 12 EPD 511,083 (D.D.C. 1976) ... 24, 25

Williams v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 552 F.2d

691 (6th Cir. 1977) .......................... 6

Statutes;

29 U.S.C. §160 (c) ...... ........................... 30

42 U.S.C. §1985 .................................... 9

42 U.S.C. §1988 ................... ................. 9, 19

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5 (h) .............................. 4, 11, 12,

19, 20, 21,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16 ............................... 1, 2

42 U.S.C. §2000e-16 (b) ............................ 5, 27, 29

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(c) ........................... 15, 24

- iv

Page

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16 (d) ............................ 27

Rules and Regulations:

Rule 29, Fed. R. App. Pro........................... 1

Rule 23, Fed. R. Civ. Pro........................... 36

Rule 23 (a) (4), Fed. R. Civ. Pro.................... 38

Rule 801 (d) (2), Fed. R. Evid...................... 24

5 C.F.R. Part 713 .................. ............... 17

5 C.F.R. §§713.214 (a), 713.215. 713.218 (c)(2),

713.221 (b)(1) .................................. 35

5 C.F.R. § 713.220 (d) ............................. 17, 18

5 C.F.R. §713.235 .................................. 17

5 C.F.R. §§713.601-713.643, published in, 42 Fed.

Reg. 11807 (March 1, 1977) ....................... 36

5 C.F.R. § 713.603(g) .............................. 37

5 C.F.R. § 713.604 (b) (iv) ......................... 38

§5 C.F.R. § 713.608 (b)(1) .......... 37

Other Authorities:

Discrimination Complaints Examiners Handbook

(1973) ...................... 33

Federal Personnel Manual Bulletin No. 713.41

(October 10, 1975) .............................. 36

Federal Personnel Manual Letter 713-38 (May 31,

1977) 38

In re Brown, Appeals Review Board Decision

(November 8, 1974) ............................... 35

v

Page

Letter from Acting Assistant Attorney General

Irving Jaffe. to Senator Tunney, dated May 6,

1975, reprinted in, 2 CCH Employment Practices

Guide,. H e w Developments 5532 7 and,

excerpted in, BNA Daily Labor Report,

Current Develpments Section for May 13, 1975 ... 10

Moore's Fed. Pract., Rules Pamphlet, Pt. 2 at

818-21 .......................................... 24

H.R. Rep. No. 94-1558, 94th Cong. 2nd Sess.,

H.R. Comm, on the Judiciary (1976) ............. 19

Subcom. on Equal Opportunities of the H.R. Com. on

Education and Labor, Staff Report On Oversight

Investigation Of Federal Enforcement of Equal

Employment Opportunity Laws, 9th Cong., 2nd

Sess. (1976) ..................... ....... ....... 32

- vi -

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

NO. 77-1697

ANNA J. BACKMAN,

Appellee,

vs.

W. GRAHAM CLAYTOR, JR.,

Appellant.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Western District Of Washington

BRIEF FOR THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AS AMICUS CURIAE

Interest of Amicus*

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

files the instant brief amicus curiae in support of the

lower court's ruling that in this employment discrimination

brought pursuant to § 717 of Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16, plaintiff

Anna J. Bachman is entitled, as the prevailing party, to

♦Letters of the parties consenting to the filing of this

brief amicus curiae have been filed with the Clerk pursuant

to Rule 29, Fed. R. App. Pro.

recover reasonable attorney's fees for legal representation

in administrative and judicial proceedings, as provided by

statute. Amicus submits that the court should affirm the lower

court s decision in light of the recent decisions of the

D. C. Circuit in Parker v. califano. ___ F.2d ___ (decided

June 30, 1977), affirming. 411 F. Supp. 1059 (D.D.C. 1976);

Foster v. Boorstin. ___ F.2d ___ (decided June 30, 1977), and

of the Fourth Circuit in Johnson v. United States. 554 F.2d 633

(decided May 4, 1977), affirming. 12 EPD 5 ll,039 (D.Md. 1976).

The Fund is a non-profit organization, certified in

New York and California, that has provided legal assistance

to black persons seeking vindication of their civil rights

1/since 1939. Since the passage of Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et sea., the Fund has

represented numerous black and women employees prosecuting

2/

actions under Title VII; with the extension of the guarantees

and protections of Title VII to federal employees in 1972,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16, the Fund has undertaken representation

of federal employees in over thirty administrative and judicial

proceedings against various federal agencies throughout the

1/ See NAACP v. Button. 371 u. s . 415, 421 n.5 (1963).

2/ See, e.g.. Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corp.. 400 u.S.

542 (1971), Griggs v. Duke Power Co.. 401 u.S. 424 (1971);

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody. 422 U.S. 405 (1975); Franks v.

Bowman Transportation Co.. 424 U.S. 747 (1976).

2

3/

nation. The Fund also has participated as amicus curiae

in significant federal Title VII cases in which, as here,

4/the interest of its clients are affected. Lastly, lawyers

associated with the Fund have been counsel in several of the

recent D. C. and Fourth Circuit cases which affirm the right

of federal employees to recover fees in both administra

tive and judicial proceedings. Amicus submits this brief in

the hope that its experience will assist the Court in deciding

the appeal and in providing guidance to the lower courts.

ARGUMENT

Summary of Argument

Because amicus believes that the objections raised by

the government to the district court's decision are more than

adequately rebutted by the decisions of the D.C. and Fourth

Circuits and appellee's brief, we limit this brief largely to three

specific points in support of affirmance. First, the administra

tive and judicial proceedings were part and parcel of the same

litigation for which an attorney's fee was awarded, as was the

case in the D.C. and Fourth Circuit cases. The government is

completely mistaken that "[i]t is . . . impossible in the

3/ See, e.g., Swain v. Hoffman. 547 F.2d 921 (5th Cir. 1977);

Barrett v. U. S. Civil Service Commission. 69 F.R.D. 544 (D.D.C.

1975) ; Ellis v. Naval Air Rework Facility, 404 F. Supp. 391

(N.D. Cal. 1976).

4/ See, e.g., Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840 (1976);

Hackley v. Roudebush, 520 F.2d 108 (1975).

3

present case to find that the bringing of suit in the

district court had any causative effect on plaintiff's

1/obtaining reinstatement and back pay." The appeal falls

directly under authoritative precedent construing, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2 000e-5(k), viz. , Parker v. Califano, Foster v. Boorstin,

Johnson v. United States, all supra, and preceding district

court decisions, infra. The government's effort to factually

or legally distinguish this line of authority is erroneous.

This Court need go no further than to affirm in light of these

cases. Second, assuming arguendo that the appeal is not

directly controlled by the holding of the D.C. and Fourth

Circuit cases because the administrative and judicial proceedings

were "separate," the provision for fees in "any action or

proceeding under [Title VII]" in 42 U.S.C. § 2 000e-5(k), and

the principles established in those cases, nevertheless,

require affirmance. The government is on a very slippery slope

indeed in contending that § 2000e-5(k) and Parker, Foster and

Johnson apply not at all in a federal Title VII action for

the reason that plaintiff prevailed in administrative rather

than judicial proceedings when the whole thrust of the

decisions is that there is no distinction between administrative

and judicial proceedings under § 2000e-5(k). The district

court also has authority to redress the failure of the

5 / Brief for Appellant at 14.

4

administrative agency to permit recovery under 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-16(b). Third, it is the experience of amicus

that attorney's fees for administrative proceedings are a

practical necessity for the enforcement of Title VII. "§ 717

does not contemplate merely judicial relief. Rather, it

provides for a careful blend of administrative and judicial

enforcement powers," Brown v. General Services Administration.

425 U.S. 820, 833 (1976). To deprive Mrs. Backman and

other federal employees of any opportunity to recover attorney's

fees in administrative proceedings would prove detrimental to

the integrity of such proceedings in which management, as here,

is represented by a lawyer.

Introduction

Initially, however, we note that the government's

position in this case opposing attorney's fees in Title VII

administrative and judicial proceedings is but one of a variety

of technical objections defendant federal agencies have raised

in employment discrimination actions to limit the effectiveness

of Title VII's administrative-judicial enforcement scheme.

Thus, the government has attempted, inter alia, (a) to deny

an employee's right to remedy Title VII violations in cases

pending administratively or judicially at the time the Act became

6/effective, (b) to permit agencies to refuse to accept,

§ / See, Kocrer v. Ball. 497 F.2d 702 (4th Cir. 1974) ; Place v.

Kaiiihfirgfir, 426 u.S. 932 (1976), vacating_and remanding in light of

confession of error. 497 F.2d 412 (6th Cir. 1974); Brown v. General Services Administration,. 425 U.S. 820, 824 n. 4 (1976).

5

2 /process and resolve classwide claims of discrimination; (c) to

permit agencies to refuse to accept, process and resolve com-

8/

plaints of continuing violations of Title VII; (d) to permit

agencies to impose an illegal burden of proof requirement in

9/

administrative proceedings; (e) to permit agencies to refuse

to give employees notice of right to sue following exhaustion

12/of administrative remedies; (f) to remand properly filed

11/actions for further administrative proceedings; (g) to limit

an employee to a review of the administrative record only

12/

rather than a trial de_ novo; (h) to deny the right to seek,...... 11/a preliminary injunction; and (i) to deny employees the right

14/

to maintain a class action. The question of attorney's

1 / See Barrett v. U. S. Civil Service Commission. 69 F.R.D. 544

(D.D.C. 1975).

8/ See Blackmon v. McLucas. 13 EPD 511,457(D.D.C. 1976);Johnson v. Froehlke, 5 EPD 5 8638 (D. Md. 1973).

9/ See Day v. Mathews . 530 F.2d 1083 (D.C. Cir. 1976).

19/ See Coles v. Penny. 531 F.2d 609 (D.C. Cir. 1976); Allen v.

Veterans Administration. 542 F.2d 176 (3d Cir. 1976), see also

Garner v. E. I. Dupont. 538 F.2d 611 (4th Cir. 1976), but see

Eastland v. Tennessee Valley Authority. 553 F.2d 364 (5th cir. 1977).

11/ See Grubbs v. Butz. 514 F.2d 1323 (D.C. Cir. 1975).

12/ See chandler v. Roudebush. 425 U.S. 840 (1976), reversing,

515 F .2d 251 (9th Cir. 1975).

13/ See parks v. Dunlop, 517 F.2d 785 (5th cir. 1975).

14/ See Eastland v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 553 F.2d 364

(5th Cir. 1977); Williams v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 552 F.2d

691 (6th Cir. 197TT

6

fees is no less significant than other issues the courts have

resolved in favor of more vigorous Title VII anti-discrimination

enforcement, guided by the principle that "congress . . . con

sidered the policy against discrimination to be of the 'highest

priority,'" Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36, 47

(1974),

To put the government's narrowly technical position

further in perspective, we note what the government does not

argue. First, the government concedes the nature and worth of

the legal services by not disputing the district court's express

factual finding that " [t]he sum of $2,375.00 is an appropriate

award of attorney's fee to be made to plaintiff for the

services . . . on her behalf [principally] in the administrative

proceedings" (R. 174). There is simply no question that

the services provided by Mrs. Backman's counsel in

administrative proceedings were of a legal character, and of

substantial worth. The government could not do otherwise on

this record since Mrs. Backman was successful as a result

of a hard-fought two-day evidentiary hearing at which agency

management's defense was handled by a Judge Advocate General

Corps lawyer (R. 5). The hearing examiner's recommended

decision is replete with references to testimony and exhibits

submitted at the hearing, id. Second, neither below nor on

appeal has the government contradicted in any way plaintiff's

averment that "I would not have won back my job without

7

effective legal representation (R. 36), nor that of her

counsel that "plaintiff would not have succeeded in obtaining a

finding of discrimination at the administrative level without

effective legal representation" (R. 39). The government, in

short, concedes that but for legal representation in

administrative proceedings, Mrs. Backman would have lost her

case notwithstanding the merits. Third, the government on

appeal no longer raises any issue as to the district court's

exercise of discretion to award fees or the amount awarded

other than its across-the-board contention that fees cannot in

any event be conferred. The government's case stands or falls

on their technical contention alone, i .p , the recovery

of attorney's fees would be appropriate if its technical

objections are put aside.

The government, therefore, makes no pretense that

its position is or can be rationalized as furthering the

practical enforcement of Title VII. Indeed, the government

proffers a frank confession and avoidance defense that only

serves to expose the poverty of its position. The government

contends that, " [wjhatever the desirability of awarding such

fees as a matter of policy, it is clear that the award of

attorney's fees for administrative work is not essential

15/

to the operation of Title VII." In support, two abstract

15/ Brief For Appellant at 27 n. 10.

8

arguments are made. First, Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. v .

Wilderness Society, 421 U.S. 240 (1975) and Runyan v. McGrary.

427 U.S. 160, 182-186 (1976) are cited for the proposition

that attorney's fees are unnecessary even in civil rights

judicial proceedings. The Alyeska decision, however, expressly

cites the civil Rights Act as an instance in which 'Congress has opted

to rely heavily on private enforcement so as to implement public

policy and to allow counsel fees so as to encourage private

litigation," 421 U.S. at 263. The citation of Runyan v. McGrary.

holding that attorney's fees cannot be recovered under 42 U.S.C.

§ 1988, also is anomalous because Congress immediately overruled

Runyan by enacting the Civil Rights Attorney's Fees Awards Act

of 1976, 42 U.S.C. § 1988, to extend Title VII's attorney's fee

16/

provision to other kinds of civil rights litigation. Second,

attorney's fees are said to be unnecessary because a judicial

trial de_ novo would "cure" "any failure of plaintiff to obtain

relief at the administrative level due to the lack of a

lawyer," surely an instance of an argument that falls of its

own weight. Moreover, "refusing to award attorneys’ fees

for work at the administrative level would penalize the lawyer

for his pre-trial effectiveness and his resultant conservation

of judicial time," Parker v. califano, supra, slip opinion

at 28-29 and authorities cited.

16/ The related contention that the administrative process does

not require employees to be represented is discussed infra at 31

part III of the argument.

9

Amicus respectfully submits that the government's

position completely ignores "the duty of the courts to make

sure that the Act -works, and [that] the intent of congress is

not hampered by a combination of a strict construction of the

statute and a battle with semantics," Culpepper v. Reynolds

Metal Co., 421 F.2d 888, 891 (5th Cir. 1970) (emphasis added).

As the D. C. Circuit put it, "'This Court as part of its

obligation 'to make sure that Title VII works' has liberally

applied the attorney's fee provision of Title VII, recognizing

the importance of private enforcement of civil rights legis

lation, ' " Parker v. Califano, supra, slip opinion at 23,

quoting, Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 488 F.2d

714, 716 (5th Cir. 1974). Divestiture of plaintiff Backman's

bona fide attorney's fees simply cannot be justified on

enforcement grounds; the foreseeable consequence of the

government's rule is obvious - to insure that Title VII's

unitary "administrative and judicial enforcement

system," Brown v. General Services Administration, supra,ITT425 U. S. at 829, does not work.

17/ The case arises because the Justice Department has re

versed its prior policy of acquiescence to award of attorney's

fees and costs in administrative proceedings under Title VII.

The prior policy is set forth in Acting Assistant Attorney

General Irving Jaffe's response to a letter from Senator Tunney,

Chairman of the Subcommittee on constitutional Rights, dated

May 6, 1975, reprinted in 2 CCH Employment Practices Guide,

New Development ^[5327 and excerpted in BNA Daily Labor Report,

Current Developments Section for May 13, 1975. Senator Tunney

had inquired about the government's "position in opposing the

10

I.

THE LOWER COURT'S DECISION SHOULD BE AF

FIRMED IN LIGHT OF THE RECENT DECISIONS

OF THE D. C. AND FOURTH CIRCUIT________

The district court held that "an award of a reasonable

attorneys' fee for services rendered in connection with

administrative proceedings may properly be made to a

successful claimant in a Title VII action or proceeding under

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k). The reasoning in Johnson v. U.S.A.

(D. Md. 1976) [12 EPD 511,039] is persuasive, regardless of

whether the claimant prevailed through administrative or

judicial proceedings" (R. 142). The government contends

that the district court erred because (a) Mrs. Backman is not

17/ (continued)

award of attorney's fees on the theory that such an award was

not specifically provided for by the 1972 amendments to Title

VII." Jaffe responded that:

"In response to the inquiry, I instituted a

staff review of this position and having carefully

considered and evaluated the results of that review,

1 have concluded that the position should be abandoned.

The United States Attorneys will therefore be instructed

not to assert that position in any case properly brought

under the 1972 amendments and to withdraw the position

from any such cases now pending. We shall, of course,

continue to address ourselves to appropriate issues

relating to the reasonableness of amounts so requested

and to the court's discretion in making an award."

2 CCH Employment Practices Guide at p. 3611.

Consistent with this policy, the Justice Department did not

oppose entitlement to the award of attorney's fees for legal

services in the administrative process in Smith v. Klein-

dienst, 527 F.2d 853 (D.C. Cir. 1975) (unpublished opinion),

affirming. 8 FEP Cases 752 (D.D.C. 1974). In Smith, the

Justice Department unsuccessfully contested only the amount of

attorney's fees.

11

a "prevailing party" under the terns of 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k),

and (b) even if the prevailing party, she cannot recover

fees for legal representation in administrative "proceedings"

under § 2 000e-5(k), Brief For Appellant at 11 et seg.

We believe that both contentions are wrong, and directly

controlled by the recent D. C. and Fourth Circuit decisions.

Because the Parker v. Califano opinion's discussion of statutory

language, purpose and legislative history is so comprehensive

on the second contention, amicus will not discuss it. Instead,

we focus on the "prevailing party" question.

A. Plaintiff Backman Was "Prevailing Party" In Judicial

Proceedings.___________________________________________

The government contends that only a federal employee who

"prevails" in judicial proceedings can recover fees under

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k), and that, as a factual matter, " [t]he

bringing of the suit . . . had no effect on plaintiff's

receipt of the reinstatement and back pay relief she sought

[,] . . . [t]he suit was therefore not a ’catalyst' to

plaintiff's receiving relief, and plaintiff is accordingly

18/not a 'prevailing party,' under 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k)."

The district court, however, correctly rejected the govern

ment's narrow factual contention that plaintiff did not

18/ Brief For Appellant at 15.

12

19/

prevail in the judicial proceedings, and correctly ruled

that, in any event, fees were appropriate "regardless of

whether the claimant prevailed through administrative or

judicial proceedings" (R. 142). In this section, we discuss

the narrow question and in part B the broader latter question.

While conceding that a prevailing party in a Title VII

action need not obtain formal judicial relief, the government

attempts to show that it was clearly erroneous to find that

. . . £2/plaintiff prevailed in the circumstances of this case.

The government's factual recital designed to show that " [t]he

21/suit was neither necessary nor in any fashion causative,"

is, at the very least, disingenuous. The basic facts are:

The Secretary of the Navy's decision was issued June 3, 1976

in a letter to Mrs. Backman that states, inter alia, that

"fb]y separate correspondence, the Commander, Puget Sound

Naval Shipyard, has been requested to initiate action to

accomplish [reinstatement and back pay] recommended by the

Complaints Examiner and endorsed by this office" (R. 23). She

also was informed that "[i]f you are dissatisfied with this

decision," "you may file a civil action in an appropriate

19/ Compare, Defendant's Brief Re Summary Judgment (R. 65-67);

Defendant's Reply Brief (r . 138-139), with, the Order Granting

Plaintiff's Motion For Summary Judgment, and Denying Defendant's

Motion For Summary Judgment (r . 142-143).

20/ Brief For Appellant at pp. 12-15.

21/ Brief For Appellant at p. 15.

13

U. S. District within 30 days of receipt of this decision,"

id. A copy of the Secretary's decision was received June 14th

by Mrs. Backman's counsel (R. 22, 23). She herself did not

hear from the Naval Shipyard until after June 25th when she

received notice that:

II 1. Thxs letter forwards the decision of the

Department of the Navy.

2. The Puget Sound Naval Shipyard has requested

the Employee Appeal Board to reconsider its decision.

You will be notified further after we receive the

Boards [sic] response."

(R. 102). Mrs. Backman did not hear from the Shipyard again,

and so on July 13th, 29 days after receipt of the Secretary's

decision by her counsel, this action was filed (r . 1). After

filing, Mrs. Backman was reinstated and informally apprised

that she would receive back pay; she received no word that

attorney's fees for legal representation in the administrative

process would be allowed (r . 33-34, 104). Mrs. Backman moved

for summary judgment October 1st (R. 24), and the government

countered with a summary judgment motion October 12th (r . 45).

Plaintiff learned for the first time on October 12th that the

Naval Shipyard's request for reconsideration had been denied

in a decision dated July 12th (R. 48).

The government's self-serving version of the facts is

inaccurate on several counts. First, in commencing the action,

Mrs. Backman followed, to the letter, the express terms of

the Secretary's decision letter " [i]f dissatisfied with this

- 14

decision," and c£ 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(c) which, in pertinent

part, provides:

"Within thirty days of receipt of notice of final

action taken by a department, agency or unit, . . . ,

an employee . . . , if aggrieved by the disposition

of his complaint, or by the failure to take final

action on his complaint, may file a civil action."

(emphasis added)

There can be no question of the action being "necessary,"

the action was necessary under the terms of the statute

itself. Second, had Mrs. Backman not filed or waited even

a few days longer, she would have imperiled her right to any

judicial relief at all. The Supreme Court on June 6, 1976 had

just decided that Title VII, with its jurisdictional pre

requisites, was the exclusive judicial remedy for federal

employees like Mrs. Backman, Brown v. General Services

Administration, 425 U.S. 820 (1976). If she had delayed

filing her action by more than one day, i.e., beyond 30 days

of receipt by her counsel, the government would have sought

dismissal, see, e.g., Bell v. Schlesinger, ___ F.2d ___

(D. C. Cir. 1977) (reversal of lower court ruling that a

Title VII action was untimely filed 32 days after "constructive"

receipt by complainant's attorney). Thus, filing the action

when she did was necessary to preserve her only judicial

remedy. Third, if the action was unnecessary because, as

the government contends, reinstatement and back pay would

have been provided without the lawsuit, the Naval Shipyard

15

was a fault- It was the Shipyard that sought reconsideration

of the Secretary's decision even though " [t]his attempt was

doomed since it was untimely already under the regulations when 22/

it was made." It was the Shipyard that did not inform

Mrs. Backman immediately of the denial of reconsideration but

delayed three months into the lawsuit and then only in

2 3/

response to plaintiff's motion for summary judgment. it was

the Shipyard that kept Mrs. Backman in a state of suspense about

24/

her rights, and necessitated the legal proceedings. in short,

the Shipyard caused Mrs. Backman to be "aggrieved by the dis

position of [her] complaint [and] by the failure to take

final action on [her] complaint." Essentially the government's

"necessity" defense boils down to penalizing plaintiff because

the Naval Shipyard was out of time in requesting reconsideration,

and because plaintiff should have known that the action was

unnecessary although the Naval Shipyard kept the information

22/ Brief For Appellant at p. 14.

23/ Mrs. Backman did not even know the basis of the request

for reconsideration until receiving it as an attachment to

defendant's summary judgment papers. Nor did Mrs. Backman know

the date of the request.

The Shipyard's letter to Mrs. Backman reinstating her

retroactively is silent on the reconsideration or its denial,

i.e«/ she was not told if her reinstatement was pending further

administrative proceedings or in response to denial of recon

sideration.

24/ "It was necessary for me to file my case in federal court

before the 30-day time limit passed, simply to seek enforcement

of the partial remedy proposed by the Secretary of the Navy"

(R. 33).

16

required to form such an opinion from her.

The government also renews its contention, previously

rejected by the lower court, that the Naval Shipyard under

U. S. Civil Service Commission regulations, 5 C.F.R. Part 713,

had no other recourse after the denial of reconsideration but

to reinstate Mrs. Backman and give her back pay. The point

is misdirected since, under the regulations, the Shipyard

theoretically could not even seek reconsideration pursuant

to 5 C.F.R. § 713.220(d), but of course the Shipyard did in fact

do so, supra. The point also is wrong; the July 12, 1976

denial of reconsideration by the Navy Employee Appeals Review

Board was not the Shipyard's last recourse. 5 C.F.R. § 713.235

plainly provides that the U. S. Civil Service commissioners

"may, in their discretion, reopen and reconsider any previous

decision when the party requesting reopening submits written

argument or evidence." The full text of § 713.235, as set2y

forth in the margin, makes clear that this direct appeal

2_5/ "Sec. 713.235 Review by the Commissioners. —

The Commissioners may, in their discretion, reopen

and reconsider any previous decision when the party

requesting reopening submits written argument or

evidence which tends to establish that:

(1) New and material evidence is available that

was not readily available when the previous decision

was issued;

(2) The previous decision involves an erroneous

interpretation of law or regulations or a misappli

cation of established policy; or

(3) The previous decision is of a precedential

nature involving a new or unreviewed policy con-

17

to the Civil Service Commissioners, unlike reconsideration

pursuant to § 713.220(d) requires no timely filing, and

unlike appeal to the U. S. Civil Service Commissioners Appeals

Review Board pursuant to § 713.235 was open to any "party,"

not just the complainant. Section 713.235 decisions, more

over, set binding policy for the federal government as a

whole. For the convenience of the Court we set forth one

such decision as an example, see Appendix A, in which the

Commission reversed its own Appeals Review Board at the

request of the Department of the Navy. Unfortunately, it is

not unusual in this area of the law that "[p]laintiff was

forced to bring this action to the federal courts because

of the agency’s refusal to implement the finding of discrimi-

2 6/

nation," Parker v. Mathews , supra, 411 F. Supp. at 1066.

The district court clearly was entitled to presume that

the "lawsuit acted as a catalyst which prompted the [defendant]

to take action implementing its own fair employment policies

and seeking compliance with the requirements of Title VII,"

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., 433 F.2d 421, 429-430

25/ (Continued)

sideration that may have effects beyond the actual

case at hand, or is otherwise of such an exceptional

nature as to merit the personal attention of the

Commissioners. [Sec. 713.235 reads as last amended

by publication in the Federal Register (37 F.R. 22717),

effective October 21, 1972.]"

26/ See, e.g., Richardson v. Wiley, 13 EPD ^[11,349 (D.D.C.

1976) (agency erroneously refused to implement proposed

disposition accepted by plaintiffs).

18

(8th Cir. 1970). With the action pending, the Shipyard

was put to the choice between compliance or further

recalcitrance with the likelihood of judicial scrutiny

and restraint. That the compliance was grudging is obvious28/

from the face of defendant's pleadings. "Certainly the

fact that plaintiff had already filed suit in this Court . . .

had a marked effect on the [Naval Shipyard's] acceptance

of the findings made by the Hearing Examiner," Johnson v .

United States, supra, 12 EPD at p. 4840. In Johnson, the

district court found that the mere pendency of a judicial

action stayed for further administrative proceedings was

enough to create the presumption that the litigation

"caused" a favorable administrative ruling. The cir

cumstances of the litigation also are comparable to those

in Parker. where "plaintiff's persistent efforts on the

administrative level were repeatedly thwarted by the agency's

2 7/ The Parham catalyst rule has been widely followed, see,

e.q., Evans v. Sheraton Park Hotel. 503 F.2d 177, 189 (D.C. Cir.

1974). Thus, the legislative history of the Civil Rights

Attorney's Fees Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C. § 1988, (extending the

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k) provision to other civil rights areas) states:

"A 'prevailing' party should not be penalized for

seeking an out-of-court settlement, thus helping to

loosen docket congestion. Similarly, after a complaint

is, ..filed,. a_,.defendant might voluntarily .cease .the .un

lawful practice. A court should still award fees even

though it might conclude, as a matter of equity, that

no formal relief such as an injunction, is needed.

H.R. Rep. No. 94-1558, 94th Cong. 2d Sess., H.R. Comm, on the

Judiciary 7 (1976) (emphasis added) (citations omitted).

28/ See R. 48 in which the Secretary's decision is characterized

as factually and legally inadequate, "an abuse of the administrative

process," and full of "apparent deficiences in the hearing and findings."

19

non-action."

"After an initial finding of discrimination from

the investigative report, it was six months before

HEW issued an interim determination which only

partially implemented the investigative finding.

A year later, in the spring of 1975, HEW issued

its final determination which completely dis

regarded the investigative report. The final

determination stated that there had been no dis

crimination and plaintiff would remain in her

position as a GS-11. Plaintiff was then forced

into a position where a lawsuit in district court

was the only means by which she could obtain the

relief which she had begun seeking over two years

previously. Significantly, the defendant answered

the complaint by denying all the allegations of

discrimination. Yet, on September 18, 1975, the

defendant totally reversed itself and issued a new

"final" determination which found that Ms. Parker

had, in fact, been discriminated against by

defendant. Due to this change in position, the

parties agreed to settle the lawsuit as to

plaintiff's Title VII claim since the agency's

reversal had provided plaintiff with all the

relief she had requested two years and seven

months previously when she had filed her administra

tive complaint. On the basis of the facts sur

rounding the settlement of this action, this Court

finds that the plaintiff is the 'prevailing party'

and that the award of attorneys1 fees is appropriate

pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k)."

411 F. Supp. at 1064-1065, affirmed on other grounds, Parker

v. califano, supra. Amicus further submits that the

D. C. Circuit’s analysis of this issue in Foster v. Boorstin

should control:

" . . . [L]ike the Parker case, supra, defendant'sreconsideration of plaintiff's administrative

complaint involved the agency's setting aside of

an erroneous administrative action that permitted

the interrupted administrative process to go

forward. In both cases the administrative recon

sideration immediately followed the complainant's

filing of a lawsuit, and in both cases the District

Court found that these two events were causally as

well as temporally related."

20

slip opinion at 8. It is of "considerable interest" that

the government has challenged whether plaintiff is "prevailing

party" in this case, although it did not do so in Parker v .

Califano, supra, where "the facts in this case . . . are indis

tinguishable from the facts of Parker," Foster v. Boorstin,

supra, slip opinion at 7. This Court should, therefore,

reject the government's contention "that, by mooting a lawsuit

through granting relief sought, the Government could avoid

liability for attorneys' fees," id. at 6.

B. Plaintiff Backman Was "Prevailing Party" In

Administrative-Judicial Proceedings________

The government's "prevailing party" contention that

a party must have prevailed in judicial proceedings only also is

wrong. The practical rule for 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (k) stated by

the district court, in reliance on Johnson v. United States,

supra, 12 EPD at p. 4840-4841, is that it is not material

whether the party seeking the award prevailed at the

administrative level or at the judicial level because both

are "part and parcel of the same litigation." In Parker v .

Califano, supra, the D. C. Circuit expressly approved the

Johnson v. United States language, slip opinion at 20, and

expressly rejected the government's insistence that in

awarding attorney's fees a technical "distinction" should be

made between administrative and judicial enforcement of

Title VII; the "entire argument clashes sharply with the

clearly perceived structure and aims of the Title," slip

opinion at 24. The Court noted that the Supreme Court stressed

- 21 -

the interrelated character of Title VII's administrative

and judicial enforcement scheme for federal employees in

Brown v. General Services Administration, supra, 425 u. S.

at 829-833, slip opinion at 19-20. "Title VII*s 'careful

blend of administrative and judicial enforcement powers,'

Brown v. GSA. 425 U.S. 820, 833 (1976), is such that

effective utilization of the administrative proceedings can

considerably ease a plaintiff's path in any subsequent

judicial proceeding while, conversely, ineffectiveness at

the administrative level can make success at the judicial

level more difficult. Parties to a Title VII suit may, for

example, submit the record of their administrative proceedings

to the District court as evidence," Parker v. califano,

slip opinion at 24 n. 26. The Parker court also noted that

in Chandlery. Roudebush, supra, 425 U.S. 863 n. 39 f the

Supreme court, slip opinion at 28 n. 33, had stated its view

that " [p]rior administrative findings made with respect to

an employment discrimination claim may, of course, be admitted

as evidence at a federal-sector trial de novo [and] it can

be expected that, in light of the prior administrative pro

ceedings , many potential issues can be eliminated"; compare

Hackley v. Roudebush, supra, 520 F.2d at 150-152, 156-159;

Reyes v. Mathews, 13 EPD 511,365 at p. 6215 (D.D.C. 1976).

Finally, the "realities of legal practice" require that

"[f]or a conscientious lawyer representing a federal employee

22

in a Title VII claim, work done at the administrative level

is an integral part of the work necessary at the judicial

29/

level," slip opinion at pp. 28-29.

Nowhere is this more clear than in the circumstances of

this case where because Mrs. Backman prevailed on the merits

in administrative proceedings, the government was barred

from relitigating the merits in court. Her complaint

appended a copy of the hearing examiner's 16-page analysis,

findings, and recommended decision (R. 4), and the Secretary

of the Navy's decision (R. 22) which concurred in the hearing

examiner's recommended decision and proposed corrective action and

which stated that " [h]is findings are supported by the record

30/and are free of error." Although grudging the government

acquiesced in the administrative determination that the Naval

2 9 / "Most obviously an attorney can investigate the

facts of his case at a time when investigation will

be most productive. The attorney may thus gain

the familiarity with the facts of the case that

is so important in the fact-intensive area of em

ployment discrimination. Perhaps even more

important, the administrative proceedings allow

the attorney to help make a record that can be

introduced at any subsequent Dxstrict court trial.

Especially in an instance where development of a

thorough administrative record results xn an abbre

viated but successful trxal, refusing to award

attorneys' fees for work at the administrative level

would penalize the lawyer for his pre-trial effec

tiveness and his resultant conservation of judicial

time. Simply to describe the operation of appellant's

suggested distinction between attorneys' fees at

the administrative and judicial levels is to

emphasize its irrationality."

Id. (emphasis added). Compare McMullen v. Warner, 12 EPD 511,107,

at p. 5124 (D.D.C. 1976) (Sirica^ J.); Reyes v. Mathews, supra,

13 EPD at p. 6215. ' -----

30/ See supra at 19 n. 28.

23

Shipyard had discriminated against Mrs. Backman on the basis

of sex, and at no time did the government contest the finding

31/

of discrimination. The administrative finding of

discrimination in any event was dispositive, whether as the

law of the case, see Local 1401 v. NLRB. 463 F.2d 316, 322

(D.C. Cir. 1972) or as an admission against interest, see Rule

801(d)(2), Fed. R. Evid.; Advisory Committee Note in Moore’s

Fed. Pract., Rules Pamphlet, Pt. 2 at 818-21. See Williams

v. Saxbe. 12 EPD 511,083 (D.D.C. 1976) (government's request

for a trial de novo denied because the government had stipu-

32/

lated to review of the administrative record). Thus,

31/ Compare, e.g., Parker v. Matthews, supra, 411 F. Supp.

at 1064-1065 (case settled in light of administrative pro

ceedings; government concedes prevailing party status on

appeal); Johnson v. United States, supra, 12 EPD 511,039

(plaintiff obtains relief in administrative proceedings on remand

and is denied further injunctive relief by court; government

concedes prevailing party status on appeal); Foster v. Boorstin,

" [N]either the District Court nor the Government on appeal

suggests that appellant did not prevail on his claim that he

had been discriminated against or in his quest for proper

remedial relief . . . [but] that because the bulk of appellant's

litigational time and effort was spent in the administrative

rather than the judicial process, he was not entitled to

attorneys' fees," slip opinion at 7).

32/ The government is not entitled to a "judicial trial de_ novo"

on liability where it has previously determined that it is liable

for discrimination in its own administrative proceedings. Unlike

employees, an agency has no right to file a lawsuit under 42

U.S.C. § 2000e-16(c). An agency is also on a different footing

practically; one reason Congress gave federal employees the right

to a judicial trial de_ novo was its concern that administrative

decisions were partial to agency management, chandler v. Roude-

bush, supra, 425 U.S. at 863 n. 39 ("The goal may have been to

compensate for the perceived fact that '[t]he Civil Service Com-

_ 24

whether a federal employee prevails in administrative or

judicial proceedings is not material. Indeed, had Mrs.

Bachman sought to embody the relief obtained in administrative

proceedings in a declaratory or summary judgment, see, e.g.,

Day v. Mathews, 530 F.2d 1083 (D.C. Cir. 1976);

Williams v. Saxbe, supra, there is no reason

it would have been denied. To do so would have been com

pletely an empty formal exercise. To have obtained such

"judicial" relief would of course satisfy the government's

requirement for "prevailing" in judicial proceedings.

The inescapable conclusion is that Mrs. Backman was, as

the lower court found, the "prevailing party."

II.

ASSUMING ARGUENDO THAT THE SUIT WAS FILED

FOR ATTORNEY'S FEES DENIED IN ADMINISTRA

TIVE PROCEEDINGS ALONE, THE D.C. AND FOURTH

CIRCUIT DECISIONS STILL CONTROL__________

The government's brief goes to some lengths, at pp.

9-10 n. 19, as well it might, to distinguish the Fourth

Circuit's decision in Johnson v. United States, supra, as

affirming the district court decision the narrow ground

32/ (continued) mission's primary responsibility over all

personnel matters in the Government . . . create [s] a built-in

conflict of interest for examining the Government's equal

employment opportunity program for structual defects which may

result in a lack of true equal employment opportunity.']

Management, unlike complainant, also, has full access to informa

tion in agency files to prepare its case in administrative

proceedings; it is not until the judicial stage that the com

plainants have any right to discovery, see chandler v. Roudebush,

supra; Hackley v. Roudebush, supra, 520 F.2d at 137-14 and T7T

(Leventhal j. concurring).

25

that "this remanded administrative proceeding was ancillary to

Johnson's initial action in the district court," 554 F.2d at

33/

633. Presumably, the government also argues that the D. C.

Circuits' decisions are also distinguishable on like grounds

34/

by pointing to Parker, slip opinion at 21 n. 24 (incorporated

33/ The Fourth Circuit expressly stated:

"We do not reach the question of whether a prevailing

party would be entitled to attorney's fees for

representation in an administrative proceeding which

took place entirely independently of, or prior to, an

action in the district court, as that issue is not

raised by the facts of this case."

Id.

34/ "In this case, as we have noted, appellee had to

file an action in the District court before she was

accorded a just remedy for the employment discrimi

nation she had suffered. It was the District Court,

therefore, that made the attorneys' fees award which

is the subject of this appeal. Appellant argues that

affirming the holding that a District Court may award

attorneys' fees for services at the administrative and

judicial levels will have the anomalous result that a

Title VII plaintiff who is unsuccessful in the administra

tive proceedings but succeeds in court will be able to

recoup attorneys' fees for all legal services rendered,

while a plaintiff who is successful at the administrative

level will not be able to recoup any attorneys' fees.

"Our holding today is, of course, limited to the

particular facts of this case. This court need not and

does not, therefore, decide whether the anomaly predicted

by appellant will in fact result. We do point out,

however, that appellee has suggested two possible ways

in which a plaintiff successful in administrative pro

ceedings might obtain attorneys' fees for services

rendered in those proceedings. The first possibility

is to allow the plaintiff to come to court on the single

issue of whether, and in what amount, attorneys' fees are

to be awarded. The second is for the agency itself to

26

in Foster, slip opinion at 9 n. 8). Amicus, however,

believes that even assuming arguendo that the administrative

and judicial proceedings were "separate,” i.e., that Mrs.

Backman filed her Title VII suit solely for attorney's fees,

the result would still be the same.

As the Parker decision indicates, federal employees

may file a Title VII action pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(c)

if dissatisfied with the resolution of their administrative

complaint because of the denial of attorney's fees. In the

instant case, the government on appeal no longer contests

jurisdiction for Mrs. Backman's suit even as limited to one11/for fees alone. That being so, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(d)

requires that "[t]he provisions of 706(f) through (k)

34 / (continued)

award fees pursuant to its authority under § 717(b),

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(b), to 'enforce the provisions

[prohibiting employment discrimination] through

appropriate remedies, including reinstatement or

hiring of employees with or without back pay, as

will effectuate the policies of this section * * *'

(emphasis added).

"We stress that we wish to intimate no views as

to the merits of either of appellee's suggestions.

They are mentioned only to show that it would be

premature to conclude that our decision will have the

consequences feared by appellant."

35/ compare, Brief For Appellant at 2, with. Defendant's

Brief Re: Summary Judgment (R. 49-50) ("The Plaintiff Fails

To State A Claim Under Title VII").

Federal Title VII actions in which plaintiff seeks further relief are common, see, e.g., Day v. Mathews, 530

F.2d 1083 (D.C. Cir. 1976) (plaintiff erroneously denied

reinstatement and back pay administratively).

27

36/

[§ 2000e-5(f) through 5(h)], as applicable, shall govern

civil actions brought hereunder," i.e., 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k)

would govern. The language, purpose and legislative history

of § 2000e-5(k), as construed by Parker v. califano, supra,

and Foster v. Boorstin, supra, apply equally to the situation

of an action to redress the denial of fees alone; nothing in

Parker or Foster turns on the fact the purpose of the case is

one for fees only. As to Johnson v. united States, the same

36/ "The most natural reading of the phrase 'as

applicable' in § 717(d) is that it merely reflects

the inapplicability of provisions in §§ 706(f)

through (k) detailing the enforcement responsibilities

of the EEOC and the Attorney General. We cannot,

therefore, agtee with the view expressed by the

District court in Hackley v. Johnson, supra, and

relied on by the Court of Appeals here, that Congress

used the words 'as applicable' to voice its intent

to disallow trials de_ novo by aggrieved federal

employees who have received prior administrative hear

ings. As the Court of Appeals for the District of

Columbia circuit held in reversing Hackley v. Johnson,

supra, such an interpretation of the phrase 'as appli-

cable' would require a strained and unnatural reading

of §§ 706(f) through (k). Hackley v. Roudebush, 171

U.S. App. D.C., at 389, 520 F.2d, at 121. This Court

pointed out in Lynch v. Alworth-Stephens Co., 267 U.S.

364, 370, that '"the plain, obvious and rational

meaning of a statute is always to be preferred to any

curious, narrow, hidden sense that nothing but the

exigency of a hard case and the ingenuity and study

of an acute and powerful intellect would discover.'"

To read the phrase 'as applicable' in § 717(d) as

obliquely qualifying the federal employee's right to

a trial de_ novo under § 717(c) rather than as merely

reflecting the inapplicability to § 717 (c) actions of

provisions relating to the enforcement responsibilities

of the EEOC or the Attorney General would violate this

elementary cannot of construction."

Chandler v. Roudebush, supra, 425 u.S. at 847-848; compare

Hackley v. Roudebush, 520 F.2d at 119-121.

- 28

condition of the "ancillary" nature of the administrative

proceedings to the judicial action obtains since the fees

award sought in court are for administrative proceedings

in which plaintiff prevailed on the merits, see supra part

I—B . The second factor relied on by the Fourth Circuit,

that " [i]f Johnson were not represented, the court's order

remanding the case might well have been less effectively

executed," slip opinion at 3, would of course also obtain.

Thus, the distinction proposed by the government makes no

difference.

While the district court did not rest its decision on

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(b) and the issue need not be reached,

amicus believes that the discussion of the question in

appellee's brief is correct, and that only two brief comments

on the government's brief, at pp. 7-10, are required. First,

the government relies principally on the D. C. Circuit's

decision in Turner v. Federal Communication Commission, 514

F.2d 1354 (D.C. Cir. 1975) and Fitzgerald v. u. S . civil

Service Commission. 554 F.2d 1186 (D.C. Cir. 1977), neither a

case in which 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(b) or even Title VII was

in issue, as precluding further inquiry. In Parker, of course,

the D. C. Circuit mentioned the § 2000e-16(b) issue, without

intimating any views, as open in order "to show that it would

be premature to conclude that our decision [concerning

§ 2000e-5(k)] will have the [anomalous] consequences feared,"

- 29

slip opinion at 21 n. 24. Moreover, the Fitzgerald opinion,

authored by chief Judge Bazelon (who was also on the Parker

panel and joined in Judge Wright's decision) expressly stated

that While the Veterans' Preference Act did not waive sovereign

immunity, "[i]n an appropriate case, it might be possible to

find an express waiver in particularly clear legislative

history," slip opinion at 6. Furthermore, Parker expresslv

37/

distinguishes Turner. Second, the Supreme Court has once

again characterized § 10(c) of the National Labor Relations

Act, 29 U.S.C. § 160(c) as "the model for Title VII's remedial

provisions," International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. united

States, 45 U.S.L.W. 4506, 4517 (decided May 31, 1977) (back

pay), reiterating the point made earlier in Albemarle Paper

Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 419 (1975) and Franks v. Bowman

Transportation Co.. 424 U.S. 747, 769 (1976). This once again

emphasizes that the language of § 2000e-16(b) itself, like

the similar § 2000e-5(g) remedial provision, based on § 10(c)

of the NLRA, 29 U.S.C. § 160(c), contemplates recovery of

fees, see, e.g., NLRB v. Food Store Employees. 417 U.S. 1, 8-9

(1974).

37/ "[T]he petitioner in Turner had requested

the FCC to order a private party to pay petitioner's

attorneys' fees covering services rendered at the

administrative level. This is quite different from

[plaintiff's] request in the instant case for the

District Court to require a government agency to

pay attorneys' fees."

Slip opinion at p. 14 n. 17.

30

III.

THE AVAILABILITY OF ATTORNEY'S FEES FOR

PREVAILING COMPLAINANTS IS A PRACTICAL

NECESSITY IN FEDERAL TITLE VII ADMINISTRA-

TIVE PROCEEDINGS

As stated above, the nature of the legal services provided,

the worth of the attorney's fees awarded, and the necessity

of legal representation in administrative proceedings in this

case are all conceded, supra, at pp. 7-8. Amicus has also

discussed how the government all but confesses that their view

that attorney's fees for administrative proceedings be denied

cannot be justified as advancing the practical enforcement

of Title VII's "complementary administrative and judicial

enforcement mechanisms," Brown v. General Services Administration,

supra. 425 U.S. at 831, supra, at pp. 8-10. In this part of

the argument, we briefly demonstrate that legal repre

sentation for prevailing complainants is generally a practical

necessity, see Parker v. Califano, slip opinion at 24-29

(government's contention that lawyers unnecessary rejected).

We begin with the fact that:

" [T]he agency [management's] representative is likely

to be a lawyer, which can only serve to exacerbate

a non-lawyer plaintiff's disadvantage. Any realistic

assessment of Title VII administrative proceedings

requires the conclusion that . . . an employee would

often be ill-advised to embark thereon without legal

assistance."

38/

Parker v. Califano, slip opinion at 27. As Judge Sirica

38/ compare Hackley v. Roudebush, supra, 520 F.2d at 140 n. 130.

31

put it, "federal employees . . . must seek relief administra

tively before going to court . . . and . . . at that stage a

lawyer will often be a practical necessity," McMullen v. Warner,

supra, 12 EPD at p. 5124. Thus, the Fourth Circuit observed

that " [i]f Johnson were not represented, the court’s order

remanding the case [for administrative proceedings] might well

have been less effectively executed," Johnson v. united States,

554 F .2d at 633. In these cases, as here, plaintiff had to

engage legal counsel for the simple reason that management

charged with discrimination was provided with counsel paid by

the agency. That agencies generally deem that representation

by counsel is necessary for management officials standing alone

is sufficient reason to reject the government's contention

that legal representation for complainant employee is somehow

unessential. The unequal dual standard for legal representation

has recently been condemned by Congress as an example of the

inequities fostered by agency control of the complaint system:

"The complainant must also pay for any legal assistance he/she

receives in the preparation of the complaint; while agencies

can draw upon legal support from their own staff attorneys,"

Subcom. on Equal Opportunities of the H.R. Com. on Education and

Labor, Staff Report on Oversight Investigation Of Federal

Enforcement Of Equal Employment Opportunity Laws, 94th Cong.,

2d Sess. 58 (1976). Both complainants and management

- 32

officials are agency employees; there is no proper basis for

separate and unequal treatment. Indeed, appellee does not

ask the court to treat complainant and management alike by

always providing counsel for both parties when it is provided

for one party; only that when an employee prevails in

administrative proceedings that he be able to recover reasonable

attorney's fees as part of the "make whole" relief required

3 9/

by Title VII, "To cure the effect of the discrimination I

have suffered and to make me whole financially, I believe that

I must be reimbursed for the legal expenses I have been forced

to incur" (R. 36).

Parker v. Califano, supra, slip opinion at 26-27, states

the obvious that "lawyers would clearly be of assistance to a

40/

lay person" in the prosecution of his complaint.

"For example, the [DISCRIMINATION COMPLAINTS

EXAMINERS HANDBOOK (1973), published by the Office

Federal Equal Employment Opportunity,] makes pro

vision for continuances and describes the grounds

for granting or denying them (id. at 20-21), pro-

39/ Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, supra, 422 U.S. at 418-421.

40/ while the Parker opinion states that lawyers are "not

indispensable," it does so without noting until later in the

opinion, at 27, that management is likely to have a lawyer.

Amicus submits that for the generality of cases, in which

management is represented by an attorney, legal representation

is necessary for the complainant just in terms of counter

vailing power.

- 33

vides for receipt of stipulations (id. at 38),

speaks to "relevancy," "materiality," and

"repetitiousness" as matters of concern when

ruling on admissibility (id. at 47-48), and

entitles the parties to participate in drafting

written interrogatories (id. at 29). The HANDBOOK,

and federal regulations, make clear that in a Title

VII administrative hearing the employee is expected

to put evidence into the record, offer proof, argue

against exclusion of evidence, agree on stipulations,

and examine and cross-examine witnesses. See 5

C.F.R. Part 713 (1977). Settlement of the charge

is possible at any stage of the proceedings and

agreements may, accordingly, have to be negotiated

and rights may be waived."

The legal services provided by Mrs. Backman's counsel are

evident from the hearing examiner's analysis, finding and

recommend decision (R. 5); appellee also has moved to have

the record on appeal supplemented with the transcript of the

two-day administrative hearing in order to further demon

strate the adverserial nature of the hearing, and the legal

representation involved. The examiner's report and the tran

script graphically demonstrate that the government's assertion

that counsel are not needed is without a shred of credible

support: the administrative hearing was for all intent and

purposes a judicial trial. (As stated above, the transcript

and the hearing examiner's report are admissible in court

in the same way that a deposition or hearing before a master

and a master's report are admissible, supra, at 22-23.) It is the

experience of amicus that the administrative hearing in this

case is fairly typical in its adverserial quasi-judicial

character.

34

It also is the experience of amicus that federal

employees usually are unable, for financial reasons, to obtain

legal representation for administrative proceedings, and

that the usual administrative hearing pits the complainant

employee (either alone or represented by a non-lawyer fellow

employee or union representative) against the management

official and his agency attorney. The Civil Service Com

mission's regulations expressly recognize that the complainant

employee has the right to have a representative from the

filing of the administrative complaint forward, see 5 C.F.R.

§§ 713.214(a), 713.215, 713.218(c)(2), 713.221(b)(1), but

no right to have a lawyer appointed. The Appeals Review

Board of the commission has specifically held that the

regulations do not allow for counsel fees to complainant who

prevails in the administrative process, In_ re Brown, Appeals

Review Board Decision (November 8, 1974).

Thus, if the complainant cannot afford to hire an attorney,

he can get counsel only if he can convince a government-

employed attorney to act as his representative. Under the

regulations, however, only an attorney employed by the

complainant's own agency can do so on official time, if such

representation is not "inconsistent with the faithful per

formance" of the attorney's regular duties as determined by

the agency. An attorney from another agency can act as

35

representative only by using up annual leave or by taking a

leave without pay. Federal Personnel Manual Bulletin

No. 713.41 (October 10, 1975). with respect to the

representation of complainant employees by agency lawyers,

Parker points out that:

"Without questioning in any way the competence

or integrity of such attorneys, we find this an

unsatisfactory alternative to allowing a plaintiff

to choose his own counsel from outside his partic

ular agency. A plaintiff who is asked to rely on

an attorney from within the very agency about whose

practices he is complaining may lack faith in the

objectivity of the proceeding. We fear that the

absence of independent counsel could only compound

the conflict of interest that might be perceived

to exist when the agency accused of discrimination

must process and rule on the claim."

slip opinion at 28.

Moreover, the Civil Service Commission has recently

issued regulations which permit employees to bring administra

tive class action complaints, 5 C.F.R. §§ 713.601 - 713.643,

42/

published in, 42 Fed. Reg. 11807 (March 1, 1977), that

further aggravate the present unequal availability of legal

representation in administrative proceedings. The new regu

lations, which are based on Rule 23, Fed. R. civ. Pro., place

42/ The new regulations were issued pursuant to court order in

Barrett v. U. S. Civil Service Commission, 69 F.R.D. 544 (D.D.C.

1975). In Barrett, the court held that the prior refusal of

the Commission to accept, process and resolve complaints of class

discrimination were in violation of Title VII.

- 36

a much greater premium on legal counsel by permitting: com

plaints of much greater extent, scope and complexity; binding

effect of a decision on class members; and, for the

« /

first time, a right for the complainant to conduct discovery.

No change, however, is made in the availability of counsel for

complainants, although the regulations appear to recognize

44/

that legal representation may be necessary. Without recovery

43/ 5 C.F.R. § 713.608(b)(1) provides:

"Both parties are entitled to reasonable development

of evidence on matters relevant to the issues raised

in the complaint. Evidence may be developed through

interrogatories, depositions, and requests for pro

duction of documents."

44/ Thus, § 713.603(g) provides:

"If the agent is an employee in an active duty

status, he/she shall have a reasonable amount of

official time to prepare and present his/her com

plaint. Employees, including attorneys, who are

representing employees of the same agency in dis-

crimmation complaint cases must be permitted to use

a reasonable amount of official time to carry out

that responsibility whenever it is not inconsistent

with the faithful performance of their duties.

Although there is no requirement that an agency

permit its own employees to use official time for

the purpose of representing employees of other

agencies, an agency may do so at its discretion.

If the use of official time is not granted in such

cases, employees may be granted, at their request,

annual leave, or leave without pay."

(Emphasis added.)

37

of attorney's fees, it is impossible to conceive of the new

regulations being implemented since legal representation is

in most cases a sine qua non of the adequacy of a named plaintiff

457to represent a class. The Civil Service Commission would

appear to agree; Federal Personnel Manual Letter 713-38

(May 31, 1977), explaining the new regulations, advises that

the agency "should make every effort to ascertain that a

potential agent f.i.e., class representative,] knows and

understands the burdens and responsibilities assumed by an

agent, is aware of an agent's entitlement to representation,

and is informed that one criterion for acceptance or

rejection of a class complaint is the perceived ability

of the agent or his/her representative to fairly and ade

quately protect the interests of the class." p . 2.

For the above reasons, amicus submits that recovery

of attorney's fees by a prevailing employee for the costs

of legal representation in administrative proceedings is

imperative.

45/ The equivalent of Rule 23(a)(4), Fed. R. Civ. Pro., is

§ 713.604(b)(iv).

38

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons, the order granting plaintiff's

motion for summary judgment, and denying defendant's motion

for summary judgment of December 7, 1976, and the judgment of

December 28, 1976 should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

X —- ^

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

BILL LANN LEE

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

LOWELL JOHNSTON

12 Geary Street

San Francisco, California 94108

Attorneys for the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc, as Amicus Curiae________

39

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

The undersigned certifies that on this 29th day of

July 1977, copies of the foregoing Brief for the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., As Amicus curiae were

served on counsel for the parties by U. S. mail, first class,

postage prepaid, addressed to:

Paul O'Neil, Esq.

Schroeter, Goldmark & Bender

540 Central Building

Seattle, Washington 98104

Robert E. Kopp, Esq.

John M. Rogers, Esq.

Civil Division, Appellate Section

U. S. Department of Justice

Defense and Educational Fund

Inc. as Amicus Curiae

APPENDIX A

[Typescript prepared from

illegible original]

December 19, 1973

Mr. M. Melvin Shralow

Attorney at Law

1330 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19107

Dear Mr. Shralow:

This is in further response to your letter of November 29, 1973

regarding the discrimination complaint case of Mrs. Jeanne S.

Ellman, Mr. Milton M. Mellman, and Mr. Louis Shapiro, which was

decided by the Commission's Board of Appeals and Review on

April 13, 1973 and reopened by the Commissioners of the Civil

Service Commission on November 14, 1973.

In your letter you question the authority of the Commissioners to

review the case, and you protest their decision reversing the

decision of the Board of Appeals and Review and affirming the decision

of the Secretary of the Navy. You request that the decision of the

Commissioners be rescinded. For your information, under the provision

of Section 713.235 of the Civil Service Regulations, the Commissioners

may, in their discretion, reopen and reconsider a previous decision of

the Board of Appeals and Review when the party requesting reopening

submits written argument or evidence which tends to establish that:

(a) New and material evidence is available that was

not readily available when the previous decision

was issued;

(b) The previous decision involves an erroneous inter

pretation of law or regulation or a misapplication

of established policy; or