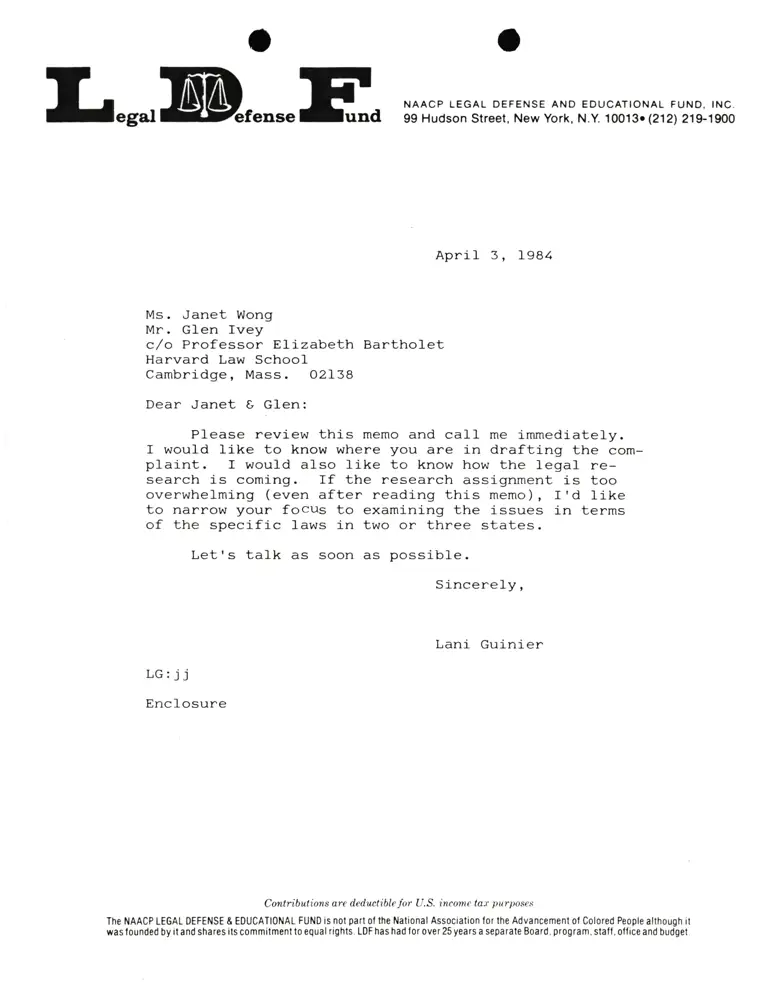

Letter from Lani Guinier to Ms. Janet Wong

Correspondence

April 3, 1984

1 page

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Letter from Lani Guinier to Ms. Janet Wong, 1984. 6549dd18-e692-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4b523905-cf8c-4795-b961-3e751f1d4f20/letter-from-lani-guinier-to-ms-janet-wong. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Lesa,UDrenseH.

April 3, L981

Ms. Janet Wong

Mr. Glen Ivey

c/o Professor Elizabeth Bartholet

Harvard Law Schoo1

Cambridge, Mass. 02138

Dear Janet E GIen:

Please review thj-s memo and call me immediately.

I would like to know where you are in drafting the com-

plaint. I would also like to know how the legal re-

search is coming. If the research assignment is too

overwhelming (even after reading this memo), I'd like

to narrow your focus to examining the issues in terms

of the specific laws in two or three states.

Let's talk as soon as possible.

Sincerely,

Lani Guinier

LG:jj

Enclosure

Contributions are dedwtible Jor U.S. intome tar purposes

The NAACP LEGAL oEFENSE & EDUCAIIoNAL FUND is not part ol the National Association lor the Advancement ol Colored People although it

was tounded by it and shares its commitment to equal rights. LDF has had lor over 25 years a separale Board. program, stafl, orrice and budget

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

99 Hudson Street, New York, N.Y. 10013o (212) 21$1900