Ward v. Louisiana Brief in Opposition to Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

April 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ward v. Louisiana Brief in Opposition to Writ of Certiorari, 1965. 8d736872-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4b5d0a99-9157-4c92-b6cb-9fceb4f0c8e0/ward-v-louisiana-brief-in-opposition-to-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

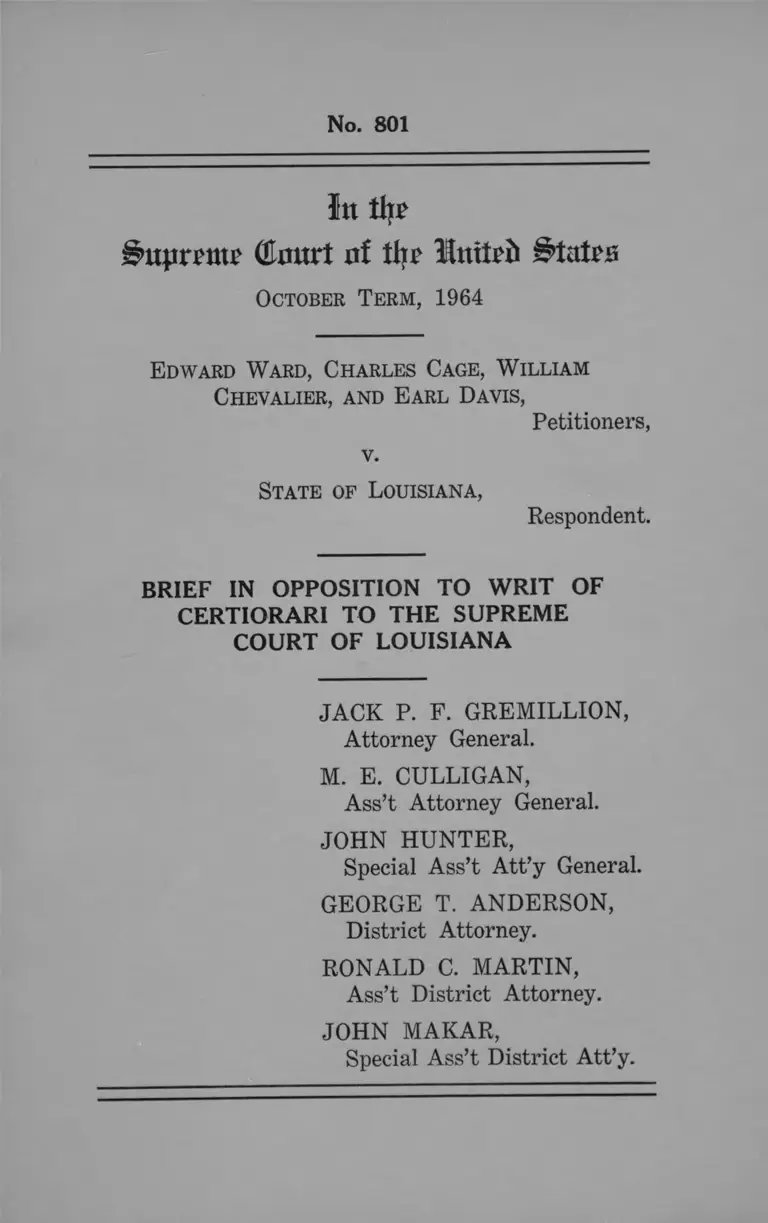

No. 801

In %

Ipitpmtte CCmtrt of tin' lltutci) States

October Term, 1964

Edward W ard, Charles Cage, W illiam

Chevalier, and Earl Davis,

Petitioners,

v.

State of Louisiana,

Respondent.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO WRIT OF

CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME

COURT OF LOUISIANA

JACK P. F. GREMILLION,

Attorney General.

M. E. CULLIGAN,

Ass’t Attorney General.

JOHN HUNTER,

Special Ass’t Att’y General.

GEORGE T. ANDERSON,

District Attorney.

RONALD C. MARTIN,

Ass’t District Attorney.

JOHN MAKAR,

Special Ass’t District Att’y.

1

TABLE OF CASES

PAGE

State v. Ashworth, (1906), 117 La. 212, 41 So2d

550; ....................................................................... 10

State v. Durr, 39 La. Ann. 751, 2 So. 546;............ 11

State v. Rogers (1961) 132 So2d 819, 241 La. 841; 12

State v. Slack (1955) 227 La. 598, 80 So2d 89;.... 10

State v. Ware (1891) 43 La. Ann. 400; ................ 12

State v. West (1931) 172 La. 344, 134 So. 243;.... 10

United States ex rel. Dukes v. Sain (1962) 297 F.

2d 799 ................................................................... 11

STATUTES

Constitution of Louisiana, Article 7, § 10............ 1, 12

LSA-R.S. 14:23 ...................................................... 1, 12

LSA-R.S. 14:2 4 .................................................... -....... 2

LSA-R.S. 14:30 ...................................................... 2, 12

LSA-R.S. 15:445 ........................................................... 2

LSA-R.S. 15:446 ........................................................... 3

LSA-R.S. 15:507 .......................................................... 3

No. 801

In tljp

^nprpntf (ttonrt of the Hnitfii States

October Term, 1964

Edward W ard, Charles Cage, W illiam

Chevalier, and E arl Davis,

Petitioners,

v.

State of Louisiana,

Respondent.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO WRIT OF

CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME

COURT OF LOUISIANA

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS

AND STATUTES INVOLVED

1. Louisiana Constitution of 1921, Article 7, § 10

§ 10. The Supreme Court has control of, and

general supervisory jurisdiction over

all inferior courts.

. . . In criminal prosecutions, its appellate

jurisdiction extends to question of law alone.

2. Louisiana Revised Statutes Annotated, R. S. 14:-

23 (Volume 9, page 84)

§ 24. Parties to Crimes

2

The parties to crime are classified as:

(1) Principals; and

(2) Accessories after the fact

3. Louisiana Revised Statutes Annotated, R. S. 14:24

(Volume 9, page 86 ):

§ 24. Principals

All persons concerned in the commission

of a crime, whether present or absent, and

whether they directly commit the act consti

tuting the offense, said and abet in its com

mission, or directly or indirectly counsel or

procure another to commit the crime, are

principals.

4. Louisiana Revised Statutes Annotated, R. S. 14:30

(Volume 9, page 352) :

§ 30. Murder

Murder is the killing of a human being.

(1) When the offender has a specific in

tent to kill or to inflict great bodily harm; or

(2) When the offender is engaged in the

perpetration or attempted perpetration of ag

gravated arson, aggravated burglary, aggra

vated kidnapping, aggravated rape, armed

robbery, or simple robbery, even though he has

no intent to kill.

Whoever commits the crime of murder

shall be punished by death.

5. Louisiana Revised Statutes Annotated, R. S. 15:-

445 (Volume 11, page 453) :

3

§ 445. Inference of intent; evidence of acts

similar to that charged

In order to show, intent, evidence is ad

missible of similar acts, independent of the

act charged as a crime in the indictment, for

though intent is a question of fact, it need

not be proven as a fact, it may be inferred

from the circumstances of the transaction.

6. Louisiana Revised Statutes Annotated, R. S. 15:-

446 (Volume 11, page 459):

§ 446. Evidence where knowledge or intent

is material and where offense is one

of a system

When knowledge or intent forms an es

sential part of the inquiry, testimony may be

offered of such acts, conduct or declarations

of the accused as tend to establish such knowl

edge or intent and where the offense is one

of a system, evidence is admissible to prove

the continuity of the offense, and the commis

sion of similar offenses for the purpose of

showing guilty knowledge and intent, but not

to prove the offense charged.

7. Louisiana Revised Statutes Annotated, R. S. 15:-

507 (Volume 12, page 80) :

§ 507. Specification of grounds for relief;

trial; proof

Every motion for a new trial must specify

the grounds upon which relief is sought, must

be tried contradictorily with the district at

torney, and the proof must correspond with

the allegations of the motion.

4

RE-STATEMENT OF CASE

As set forth in the first two paragraphs of pe

titioners’ application, on November 10, 1962 a post

football game party was going on at the apartment of

John Fisher situated on a corner of Lafayette and

Second Streets, at 801 Second Street in the city of

Natchitoches. A little after midnight, James Larry

Weeks and Daniel J. Brupbacker left the party to go

to the Circle Cafe for something to eat. This cafe

was located on the corner of Lafayette and Washing

ton or Front Street, one block east of the apartment.

Brupbacker was somewhat intoxicated and talk

ing loudly, but as the two boys approached the men

coming out of the colored entrance of the Circle Cafe

about twenty-five or thirty yards away, Larry Weeks

told Brupbacker to quiet down, and he did. (R. 155)

There were about eight people on the sidewalk,

including two men, near the entrance of this cafe. ( R.

156) Neither of these boys said anything to this

group as they approached and passed them. However,

Larry Weeks accidentally brushed one of the boys in

passing. Nothing was said until the two boys had

walked about five more yards past the group and

one member of the group asked, “ What do you want?”

or “ What are you doing?” (R. 157). One member of

the group then reached a hand in his pocket as if he

were going for “ something” . Weeks imitated this

gesture as he and Brupbacker began to back toward

the corner of Lafayette and Washington Streets in

order to get around to the front entrance of the cafe as

5

Cage, Davis, Chevalier, Courtney and perhaps others

began to advance and attempt to surround them. (R.

106, 130) Counsel’s statement that “ a group of white

men emerged (at this point) and came to the rescue

of Weeks and Brupbacker” is not supported by the

evidence. The two got around the corner, to the front

entrance of the cafe, and opened the door when one

member of the group, a boy by the name of W. C.

Courtney who had gone to the Circle Cafe with Charles

Cage, William Chevalier and Earl Davis, threw a

rock or brick at Weeks and Brupbacker. It missed the

two boys and struck the door of the Circle Cafe.

Petitioners’ counsel says that heated words were

exchanged between Weeks and Brupbacker and some

of the young negro boys, but the testimony of Weeks

and Brupbacker was not contradicted by either Cage

or Davis, who simply said that they got into an argu

ment with the two boys.

Weeks picked up the rock or brick and hurled it

at the pink and white Buick in which Chevalier, Cage

and Davis were riding away, striking the windshield

of the Buick.

Cage, Chevalier and Davis rode around the block

and passed back in front of the Circle Cafe where a

group had gathered. Apparently someone in the group

hollered, telling them to stop, perhaps cursing. (R.

742, 743)1 (R. 817)2

Cage, Chevalier and Davis then went looking for

mavis’ testimony.

2Cage’s testimony.

6

Cage’s uncle, Edward Ward, and found him at the

Casa Grande or Casino Inn on Phillips Street. Cheva

lier went inside and brought Edward Ward outside

where they say “ we told Ward what happened” .3 Ed

ward Ward said that he was told that they were

standing on the sidewalk and some white boys came

along and bumped into them and deliberately pushed

them off the sidewalk. (R. 872) Neither Davis nor

Cage told Ward that W. C. Courtney had first thrown

a brick at the two boys at the Circle Cafe. (R. 759

Davis) (R. 573 Cage) Ward further stated that

Chevalier told him in response to his inquiry as to

what he did when they pushed them off the sidewalk,

“ that they didn’t do anything— that they didn’t want

to get into any trouble and that a fellow picked up a

brick and threw it through the windshield and broke

the windshield.” (R. 872)

Ward’s, Davis’ and Cage’s testimony shows that

Ward left the three boys standing together outside in

front of the Casa Grande and that he went back in

the cafe and there returned with George Wright to

the latter’s Volkswagon automobile parked in front

of the Casa Grande where Wright gave Ward the

murder weapon. (Ward R. 873, 874) (Cage R. 805)

It was only after he had gotten the gun that

Ward walked by his Buick and surveyed the damage

to the windshield. (R. 874) At this time he had the

gun in his right hand, which he says was at his side.

(R. 874) Ward made no attempt to hide the gun after

nWilliam Chevalier’s statement and Earl Davis’ and Charles Cage’s

statements and testimony.

7

he got it from George Wright’s car and walked across

the street to the Buick and then to his station wagon

which was parked in front of the Buick (R. 767),

and although he says that the three boys were already

in his station wagon, Earl Davis said that they were

standing by the Buick when Ward walked up and said,

“ come get in the car and go with him.” (R. 770) Cage

says, “ well, we stood out by the car until he came

back, and he told us to get in the car.” (R. 806)

Earl Davis testified that they stayed close to

gether from the time they go to the Casa Grande

until the time they left with Edward Ward with the

exception of the time when Chevalier went inside the

club to get Ward which was just long enough to go

inside and come right back out. (R. 772)

Ward then told the three boys to take him down

town to where the rock throwing incident took place.

(R. 796, 797) Chief of Police, Boyd Durr, testified

that by the shortest route the distance from the Circle

Cafe to the Casa Grande Club was about one (1) mile.

The defendants approached 801 Second Street

from the south on Second Street very slowly. (R. 301,

329) While they denied slowing down until they ac

tually turned off Second Street onto Lafayette, the

testimony of Gary Harkins (R. 301, 306), who, in

cidentally had drunk no alcoholic beverages that eve

ning, and Charles Gowland (R. 328) contradicts this

denial. Ward then drove his vehicle onto Lafayette

and stopped, said something to the group of boys

standing in front of the apartment, fired two shots at

8

one of these boys and hurriedly drove away to a club

east of Natchitoches where he separated from Cage,

Chevalier and Davis, advising them, if asked, to deny

any knowledge of the shooting— (R. 847, 849)

ARGUMENT

I.

As a reason for granting the writ, the petitioners

cite the then pending case of Robert Swain v. Alabama

which was decided March 8, 1965 after the petitioners’

brief was filed.

The issues in the Swain case relative to the State’s

peremptory challenges were not similar to the issue

of the instant case. In that case there was some evi

dence that negroes had been peremptorily challenged

or struck by the prosecution from the petit jury. In

the present case, there is no evidence at all that any

negroes were peremptorily challenged by the prosecu

tion. In fact, there is no proof at all on this point in

the record, and this will be discussed under the head

ing of the next point.

II.

The petitioners contend that the public prose

cutor’s racial use of peremptory challenges to exclude

negroes from jury service violated their right to due

process and equal protection under the laws.

On April the 18th, 1963, the petitioners in this

case filed a motion for a new trial (R. 963) alleging,

“ on the further ground that your defendants are

members of the colored race, and that even though

9

members of their race were on the regular venire,

on the venire of tales jurors and among the by

standers summonsed by the sheriff as prospective

jurors after both the general venire and the

venire of tales jurors had been depleted, all of

those members of your defendants’ race who were

interrogated as prospective jurors, who did not

disqualify themselves, (Emphasis supplied) were

peremptorily challenged by the district attorney

and consequently no member of their race was on

the jury that convicted them.”

A hearing was had on the petitioners’ motion for

a new trial on April 24, 1963 at which time evidence

was taken in support of the motion on other grounds,

but the petitioners did not attempt to offer any evi

dence at all to show any discretion on the part of the

prosecution in the use of its peremptory challenges.

In fact, it is the distinct recollection of the district

attorney that the majority of the negroes all excused

themselves principally, because they did not believe

in capital punishment, and to a lesser extent, because

of a close relationship or acquaintanceship with one or

more of defendants which would tend to prejudice

them. Additionally, while it is not asserted as a fact,

it is the impression of the district attorney that the

petitioners’ counsel exercised peremptory challenges

himself in excusing several members of the colored

race.

Petitioners assert that because the district at

torney apparently did not contest the factual asser

tion by them, the trial judge assumed the truth of

the allegation in ruling that the state is excusing

10

negroes from service on the jury was exercising and

utilizing peremptory challenges which it had a right

to do.' Let it be noticed that the district attorney

had no opportunity to make any kind of denial except

by brief to the Supreme Court of Louisiana, and then

deemed it unnecessary in view of the fact that there

was no evidence to support the allegation.

Petitioners say on page 16 of their application,

“ that although the Supreme Court of Louisiana

found that petitioners had not offered proof that

negroes were systematically excluded by use of

the state’s peremptory challenges, the Court chose

to disregard this conclusion, exercised its discre

tion and decided petitioners constitutional claim

as if the allegations with respect to use of per

emptory challenges were true.”

Petitioners admit that the Supreme Court of

Louisiana found that they had offered no proof of

this use of peremptory challenges. The law of Lou

isiana requires that the allegations offered in support

of a new trial be proved.' Defendants must make some

showing to support a motion for a new trial.0 If al

legations of a motion for a new trial are not supported

by proof, the motion is properly overruled.4 * * 7 The de

cision of the Court was based upon the jurisprudence

of the State of Louisiana, however, the Court did go

on to discuss the right of peremptory challenges by

4Petition for Certiorari, page 9.

r’LSA-R. S. 15:507, supra

sState v. West, 1931, 172 La. 344, 134 So2d 243, State v. Ashworth,

1906, 117 La. 212, 41 So. 550

’’State v. Slack, 1955, 227 La. 598, 80 So2d 89.

11

both the state and the defendant8 *, State v. Durr0,

and Dukes v. Sain10.

It might be said in passing that it would be an

unskillful prosecutor indeed who would waste peremp

tory challenges on the color of a man’s skin while

knowing at the same time that after their exhaustion,

he might be forced to accept a juror of the most prej

udiced sort.

It is submitted that by authority of the Swain

and Dukes decisions, and cases cited therein, the con

tention of the petitioners in this respect is without

merit.

III.

THERE WAS EVIDENCE FROM WHICH

THE JURY COULD FAIRLY INFER THAT CAGE,

CHEVALIER AND DAVIS KNEW THAT ED

WARD WARD INTENDED TO KILL OR INFLICT

GREAT BODILY HARM UPON THE BOY RE

SPONSIBLE FOR BREAKING W ARD’S WIND

SHIELD AT THE TIME THEY LEFT THE CASA

GRANDE WITH WARD AND THAT THEY EN

TERTAINED THE SAME INTENT AND AC

TIVELY ASSISTED WARD IN THE COMMIS

SION OF THE CRIME OF WHICH THEY WERE

CONVICTED.

8167 So2d at page 362.

”State v. Durr, 39 La. Ann. 751, 2 So. 546

10U. S. ex rel. Dukes v. Sain, 297 F.2d 799 (1962) Writs denied

369 US 868, 82 S. Ct. 1035, 8 L. Ed. 2d 86, Rehearing denied 370

U.S. 920, 82 S. Ct. 1558, 8 L Ed 2d 500.

12

In criminal matters, the appellate jurisdiction of

the Louisiana Supreme Court extends to questions of

law alone.11

While the Louisiana Jurisprudence recognizes

that the absence of any evidence at all to support a

conviction becomes a matter of law,12 it is only in cases

where there is no evidence at all tending to prove that

particular fact which is essential to a valid conviction,

that the Court may set aside the conviction for want

of proof of the guilt of the defendant.13

Louisiana has abolished the common law distinc

tion between principals and accessories before the

facts, and parties to crimes are classified as principals

and accessories after the fact.14

LSA R. S. 14:24 provides:

“ all persons concerned in the commission of a

crime, whether present or absent, and whether

they directly commit the act constituting the of

fense, aid and abet in its commission, or directly

or indirectly counsel or procure another to com

mit the crime, are principals.”

The Louisiana statute defining murder requires

the presence of a specific intent to kill or to inflict

great bodily harm.15

“ Section 10, Article 7, Louisiana Constitution of 1921 as amended,

supra

12State v. Ware, 1891, 43 La. Ann. 400

lsState v. Rogers, 1961, 132 So2d 819, 214 La. 841, Cert, denied

82 S. Ct 1589, 370 U. S. 963, 8 L. Ed. 2d 830, and cases cited in the

original opinion.

14LSA-R. S. 14:23

)r“LSA-R. S. 14:30

13

As to what constitutes one a principal, American

Jurisprudence states the general rule to be that he

must be present, aiding by acts, words or gestures and

consenting to the commission of the crime, either be

fore or at the time of the commission of offense, with

full knowledge of the intent of the persons who com

mit the offense.10 Therefore, one who inflames the

mind of others and induced them by violent means to

do an illegal act is guilty of such act, although he takes

no other part therein. If he contemplates the result, he

is answerable, although it is produced in a manner

different from that contemplated by him. If he gives

directions vaguely and incautiously and the person

receiving them acts according to what he might fore

see would be the understanding, he is responsible.17

Mere knowledge that a crime is going to be com

mitted, in the absence of a duty to prevent it, does

not make one guilty of participation in it, but

where one takes another to the scene of the crime

with knowledge that it is going to be committed

or assist the active culprit to get away can not

claim innocence.18

The instrument or means by which a homicide

has been accomplished is always to be taken into

consideration in determining whether the act is

criminal and in what degree it may be so. When,

in a prosecution for homicide, it is shown that

the accused used a deadly weapon in the commis

sion of a homicide which is the subject of the * 17 *

“ Am. Jur. Criminal Law, Volume 14, Sec. 87, page 826

17Am. Jur. Criminal Law, Volume 14, Sec. 90, page 829

“ Corpus Juris Seeondum, Sec. 88<2), page 263.

14

prosecution, the law infers or presumes from the

use of such weapon, in the absence of circum

stances of explanation or mitigation, the existence

of the mineral element— intent, malice, design,

premediation, or whatever term may be used to

express it— which is essential to culpable homi

cide.19

“ Evidence which shows or tends to show prepara

tions, on the part of the defendant in a prosecu

tion for homicide, for the killing is relevant,

material, and admissible, whether the fact of

killing is denied or the accused relies on self-

defense. Proof may be given that shortly before

the commission of the homicidal act, the defend

ant procured a weapon such as caused the mortal

wound.” 20

“ All minor or evidentiary circumstances which

tend to shed light on the intent of the alleged

slayer are admissible in evidence in a prosecution

for homicide, although they may have happened

previous to the commission of the offense

charged.” 21

We must look to the record then to see whether or

not there was intent, knowledge, and aid or assistance

rendered to the petitioner Ward by the petitioners,

Chevalier, Cage and Davis (hereinafter referred to

as defendants), in order to determine whether there

was some evidence of these essential elements to sup

port their convictions.

"A m . Jur. Homicide, Volume 26, Sec. 305, page 360

20Am. Jurisprudence Homicide, Volume 26, Sec. 322, page 372

21Am. Jur. Homicide, Volume 26, Sec. 324, page 375

15

CAGE, CHEVALIER AND DAVIS HAD A

MOTIVE FOR THE MURDER.

While Louisiana law does not require the proof

of motive as an element of the crime, its existence

shows a previous relationship between the parties and

has an evidentiary bearing upon the actor’s intent.2'

There had been an argument between the three

defendants and Weeks and Brupbacker of such in

tensity as to motivate W. C. Courtney to throw a

brick or large rock at them with such great force as

to smash the door to the Circle Cafe. Weeks had

thrown the stone back at them with such force as to

break the windshield of Ward’s Buick they were driv

ing, and causing glass to cut Chevalier’s head.

After leaving the Circle Cafe, making the block

and driving past it again in search of Courtney, a

group of boys who had gathered in front of the cafe

hollered at them, telling them to stop and cursing.

(R. 742, 743)1 (R. 817)2

Here was evidence of a motive of revenge.

EVIDENCE THAT CAGE, CHEVALIER AND

DAVIS DELIBERATELY INCITED WARD TO

VENGEFUL WRATH— EVIDENCE OF THEIR

INTENT

The story related to Ward by these three defend

ants was that they were standing on the sidewalk

and some white boys came along and bumped into

“ Am. Jur. Homicide, Volume 26, Sec. 321, page 371

footnote 1 supra

=Footnote 2 supra

16

them and deliberately pushed them off the sidewalk.

(R. 872) When Ward asked them, what they, the

defendants did, they, through Chevalier their spokes

man, replied that “ they didn’t do anything. That they

didn’t want to get in trouble and that a fellow picked

up a brick and threw it through the windshield, break

ing it.” (R. 872) No one told Ward that W. C. Court

ney had thrown the rock at the white boys first. (R.

759 Davis) (R. 573 Cage) All three defendants par

ticipated in this lie. (R. 574-805 Cage) (R. 555 Cheva

lier) (R. 566 Davis)

EVIDENCE OF W ARD’S FRAME OF MIND

AS IT BEARS ON INTENT

The above version of the rock throwing incident

was highly inflamatory and of such a nature as to

provoke anyone to anger. Ward’s car windshield was

smashed by the boys at the Circle Cafe. His nephew

who lived with him and his friends who worked for

him had been badly handled and pushed around. They

had been “ ganged” , cursed, (perhaps invited to come

back and fight?) at the Circle Cafe— Chevalier was

bleeding from a cut on his head— W. C. Courtney was

missing. Ward got mad. “ I’m mad from the word go” ,

he said. (R. 880) He also gave this as a reason for his

not thinking when he got a gun before leaving the

Casa Grande Club to go downtown. Cage says “he

(Ward) got mad” . (R. 574)

ADDITIONAL EVIDENCE OF W ARD’S IN

TENT TO KILL OR INFLICT GREAT BODILY

HARM

17

After listening to the rock throwing version in

front of the Casa Grande Club, Ward went back in

and returned with George Wright where Wright gave

him the murder weapon from his Volkswagon parked

in front of the club. (R. 873, 874 W ard). Ward did not

even look at the damage to his Buiek until he passed

by it in the process of getting to his station wagon to

go downtown. (R. 874)

Ward told the other three defendants to come go

show him downtown and show him the boys and where

it happened and we would see about this. (Cage R.

574)

Davis said Ward said, “ let’s go downtown to the

place where the windshield got broken.” (R. 796, 797,

568)

EVIDENCE THAT CAGE, CHEVALIER AND

DAVIS KNEW OF W ARD’S INTENT TO COMMIT

MURDER OR GREAT BODILY HARM UPON

THEIR ANTAGOMISTS AT THE CIRCLE CAFE.

That Chevalier, Cage and Davis knew of Ward’s

anger has already been shown. They also knew that

Ward was armed.

Ward did not pretend that he made any effort

to hide the gun as he walked across the street from

Wright’s Volkswagon to his Buick, where the others

were standing but he tried to make it appear that the

others were already in his station wagon when he came

across the street and got in it, hugging the gun close

to him and slipping it under the seat to his right.

However, Cage said, “ we stood out by the car

18

until he (Ward) came back, and he told us to get in

the car.” (R. 806)

Davis said they were “ all standing up in front

of the Buick right behind the station wagon.” (R.

767). Davis saw Ward at the Volkswagon and when

he came over from the Volkswagon he told them to get

in the car and go with him. (R. 769, 770)

Cage, Chevalier and Davis were not separated

from the time they arrived at the Casa Grande until

after the shooting with the exception of the time Cheva

lier spent inside the club getting Ward, which was

just long enough to go inside and come right back

out. (R. 772 Davis)

Chevalier said in his statement, “ I think George

gave him a pistol.” (R. 555)

There was nothing to prevent the others from

seeing Ward’s gun as he walked across the street, and

they all got in his car. What was there to be seen could

reasonably be inferred by the jury to have been seen.

An armed and angry man asked Cage, Chevalier

and Davis to take him downtown where the rock

throwing incident occurred and to show him the boys

that did it. Ward’s intentions were unmistakeable.

EVIDENCE THAT CAGE, CHEVALIER AND

DAVIS AIDED WARD IN CARRYING OUT HIS

INTENTION.

Both Davis and Cage say that Ward told them

to take him back downtown where the incident hap

pened. (R. 574, 796, 797) The undisputed fact that

19

they did is evidence of their aid and assistance.

On the way downtown, the defendants passed the

Sheriff’s office, State Police Substation, and came

within one-half a block of the City Police Station but

made no effort to seek official assistance. All of this

rebuts Ward’s statement that he only wanted to see

about getting his windshield paid for.

The circumstances surround the shooting itself

goes far to reveal the intent and design of the defend

ants.

In their testimony, the defendants seek to make

it appear that they rolled up to the corner of Second

and Lafayette Streets without hesitation and stopped.

The purpose of this is to maintain the consistency of

Ward’s defense that he was inflamed by someone’s

invitation, “ you black bastard! Do you want to fight?” .

However none of this is consistent with the facts.

Earl Davis says in his statement and in his testi

mony that “ Ward asked us if that was some of the

boys and we said yes, we think that is some of them” .

(R. 749) In Cage’s testimony with reference to Ward

asking if those were the boys (involved in the rock

throwing incident), he said “ and we said we believe

it was” . (R. 808) Davis admitted on cross examina

tion that he got a good look at the boy who threw the

rock through the windshield— that he was dressed in

a white shirt, black trousers, coatless and hatless. (R.

748)

Weeks described the murdered John Fisher’s dress

and build

20

A. John had on a white dress shirt, dark tie and

dark trousers similar to myself.

Q. Did he have on a coat?

A. No sir.

Q. Did he have on a hat?

A. No sir.

Q. Can you describe his general build?

A. Yes sir. He was— I guess he was, maybe, two

or three inches shorter than I am— but maybe

a little bit broader, but similar build. (R. 144)

It was the state’s theory that when the defendants

first sighted the group of boys standing in front of

the premises at 801 Second Street, Ward slowed the

car down in order that his passengers might study

them to see if any of these boys were those involved

in the rock throwing incident and that they mistakenly

identified John Fisher as the boy who threw the rock

through Ward’s windshield, or Larry Weeks. This is

borne out by the testimony.

Larry Weeks was sitting next to a window over

looking the intersection of Lafayette and Second

Streets when the lights from Ward’s car swept into

the window and caused him to turn and look down,

and as he did, he saw two flashes from the driver’s side

of the vehicle. (R. 141) The vehicle appeared to be

stopped partially onto Lafayette Street going toward

Washington Street with the back part on Second

Street. (R. 142) He ducked when the shots were fired

and heard the car tires screech around the corner

21

going off fast down the hill toward Washington Street.

(R. 143)

Daniel Brupbacker states that Donald Bates and

Sidney O’Brien, who was escorting the former away

from the house, were walking toward Texas Street,

away from Lafayette and Second Streets, and that the

witness walked up and said something to John Fisher

and walked back to the steps of the apartment, and

as he approached the steps he heard two shots. (R.

267) He states that Fisher was standing right in

front of the steps on the sidewalk facing away from

the corner of Lafayette and Second Streets when the

witness turned and walked back toward the steps. (R.

268) When the shots were fired, he turned around

and saw John Fisher fall on the ground and blood run

out of his mouth. (R. 268) He says that as he turned

and took a couple of steps back toward the house John

Fisher was talking to O’Brien who was walking away

from the front of the house in the opposite direction

from the intersection from which the shots came. On

cross examination, Brupbacker was asked,

“ Q. Did you hear Mr. Fisher say anything to any

one other than some of the boys who were

out there?

A. No sir.

Q. Did you hear Mr. Gowland say anything to

anybody?

A. No sir.” (R. 291)

At the time of the shooting Gary Harkins was

standing on the bottom steps of the apartment or on

22

the sidewalk right in front of the steps facing John

Fisher and the street, Second Street in front of the

apartment. (R. 300) Ward’s car was coming up Sec

ond Street at this time. (R. 300)

Summarizing this witness’s testimony, he stated

that he noticed the station wagon coming up the street

and that its occupants put their lights on them. The

witness thought it was someone who was about to park

and come over to the house. He says that after look

ing back at John, the car started coming back up the

street again and that it then pulled in Lafayette Street

at an angle, two shots were fired, the vehicle drove

off and John Fisher was on the sidewalk. (R. 301).

The witness says that at the moment the shots were

fired John Fisher was talking to him, Danny Brup-

backer and Charles Gowland with his back toward

Lafayette and looking toward the witness to his right

a little. (R. 302). His description of the approach of

the automobile was that it slowed down almost stop

ping to about two or three miles an hour, just barely

creeping along, that two shots were fired and they

were gone (R. 306). He says that it was stopped for

only a couple of seconds (R. 317).

Summarizing Charles Gowland’s testimony, the

witness stated that they were all standing outside the

apartment and that there was no loud talk or disturb

ance outside, just general conversation (R. 327). In

a matter of minutes, he observed the white station

wagon approach from the south on Second Street. He

began to pay particular attention to it because the

uncle and aunt of his girl friend whom he dated that

23

night had an identical station wagon, and he thought

that perhaps it was she coming back to the apartment

for some reason (R. 328). He went on to say that the

car made a slow approach up Second Street, turned

into Lafayette and stopped although he could not tell

who was in the car, whether they were black or white.

(R. 328). He stated that he heard something shouted

from the car, although he was unable to understand

what was said (R. 335), and then saw two flashes and

the sound of a gun (R. 330) and John Fisher said,

“ Fm hit.” (R. 329). The witness stated that at first

he thought it was a prank or firecrackers (R. 330).

This witness stated that he did not hear any one

standing outside or any of his party at the premises

say anything to the occupants of the station wagon.

(R. 380)

With respect to the manner in which the car left

the scene, Gary Harkins said it left as fast as it could.

(R. 303)

The witness, Sidney O’Brien testified,

“ Well for a moment we stood out in front of

the steps, well actually it was just a moment

and Fisher wanted to know if I could handle

Donald Wayne, and then, I said yes go on, go

ahead and I would take him on to the dorm, so

Donald Wayne and I had turned and were

actually going north on Second Street, walk

ing down the sidewalk to the car, and we had

gotten along approximately to the end of the

porch, and Donald Wayne decided he wanted

to go back in, so I stopped him and was stand

24

ing in front of him. And along about that

time, well this— were these lights— car lights.”

Q. “ Were you looking in the direction of these

lights?”

A. “ No sir. I was looking north on Second Street.”

Q. “ All right.”

A. “ And as I noticed the glare of the lights down

the street, I glanced around to my left and I

saw this— well it was new— it was a Ford

station wagon. And— it was the rear end of

it I saw, maybe four to six feet the rear end

of it, turn to go on Lafayette Street. And I

just glanced by back around and about that

time well, Donald Wayne— well I heard these

two shots, just bang, bang. Actually at the

moment I thought it was a car load of high

school kids and saw a bunch of us out there

and threw a couple of firecrackers out to scare

us, and well about that time Donald Wayne

says ‘My God, he’s shot’, and both of us turned

around about that time and Fisher was laying

on the sidewalk with blood all over his face.”

(R. 344)

These were the only witnesses outside of the

apartment who knew anything about the shooting

with the exception of Donald Wayne Bates, who died

prior to the trial as was stipulated in the record.

Photographs introduced into evidence show the

body of John Fisher lying on the sidewalk in front

of the steps of the apartment where the witnesses tes

tified that it fell.

Dr. Charles Cook, the parish coroner, went to

25

the scene of the shooting and later performed an au

topsy on the body of the victim. His testimony estab

lished that a bullet had entered John Fisher’s body

from the back near the shoulder blade on the right,

traveling up and slightly to the left, severing the large

aorta of the heart and stopping just under the skin

near the left nipple. (R. 205, et seq.)

The testimony of Dr. Cook relative to the path of

the bullet through the victim’s body corroborates the

testimony of the witnesses as to which way the victim

was facing at the moment he was shot. Gary Harkins

was standing on the steps facing John Fisher and

Second Street at the moment of the shooting and he

says that when Fisher was shot, he was facing toward

us, he was to our left and was facing back toward us.

(R. 302)

The location of these witnesses was also indicated

by them on a large plat of the area marked Exhibit

“ G” which was displayed to the jury.

This testimony is diametrically opposed to the

defendant’s contention that John Fisher walked up to

the station wagon and uttered a vile challenge. Ward

said he stopped on the corner with the intention of

questioning the fellows on the corner but that before

he had an opportunity to open his mouth and say any

thing, someone rushed up to him and said,

“ you black son of a bitch, do you want to fight.” ,

to which he replied, “ yes, I’ll fight, god damm it or

words to that effect” . (R. 878), and that he

reached down and got the gun and fired twice out

of the window.” (R. 878-879)

26

Unquestionably Ward fired at the person whom

he said rushed up to the car and uttered the challenge.

“ I fired at someone who approached the car, Fm

trying to clarify this, I don’t know which one of

the guys from the other one, that who ever made

the remark to me and attempted to approach the

car, that is the individual I fired at.” (R. 893)

The evidence leaves no room for doubt that Ed

ward Ward shot and killed a boy who appeared very

much like the boy who had thrown a brick through

the windshield of his car, and he could have known who

that boy looked like only by having him pointed out

by his co-defendants as he approached the premises at

801 Second Street and studied the group of boys out

front.

This evidence supports the state’s theory that

Ward’s statement to the effect that “ I’ll fight you all

right” , was not made in response to anything that was

said by any of the boys standing out in front of the

apartment but simply that Ward was finishing up

something that he thought they had started.

The record abounds with evidence of aid Cage,

Chevalier and Davis rendered to Ward in perpetrating

this crime. There is evidence that they aided him with

knowledge of what he intended to do— kill or inflict

great bodily harm, and there is evidence that they

actively entertained a similar intent and desired the

resulting consequences.

The petitioners complain that the trial court did

not sufficiently instruct the jury of the LSA R. S.

27

14:24, relating to principals. This point is raised a bit

late. No objection was made to the charge nor was any

special instruction requested. However, it is submitted

that the language of this article should not be so dif

ficult to comprehend to the average man, and there

was evidence offered to prove the principal relation

ship.

CONCLUSION

It is respectfully submitted that the petition for

certiorari should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK P. F. GREMILLION,

Attorney General.

M. E. CULLIGAN,

Ass’t Attorney General.

JOHN HUNTER,

Special Ass’t Att’y General.

GEORGE T. ANDERSON,

District Attorney.

RONALD C. MARTIN,

Ass’t District Attorney.

JOHN MAKAR,

Special Ass’t District Att’y.

28

C E R T I F I C A T E

I, Jack P. F. Gremillion, a member of the bar of

the Supreme Court of the United States and Louisi

ana Attorney General, of counsel herein, hereby certify

that a copy of the above and foregoing brief was served

on Messrs.

James M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York, 10019

and

Russell E. Gahagan

P. 0. Box 70

Natchitoches, Louisiana

counsel for the petitioners, by depositing same in the

United States Mail with sufficient postage affixed.

Jack P. F. Gremillion

B-179, 4-65