Correspondences between Guinier and Whatley

Correspondence

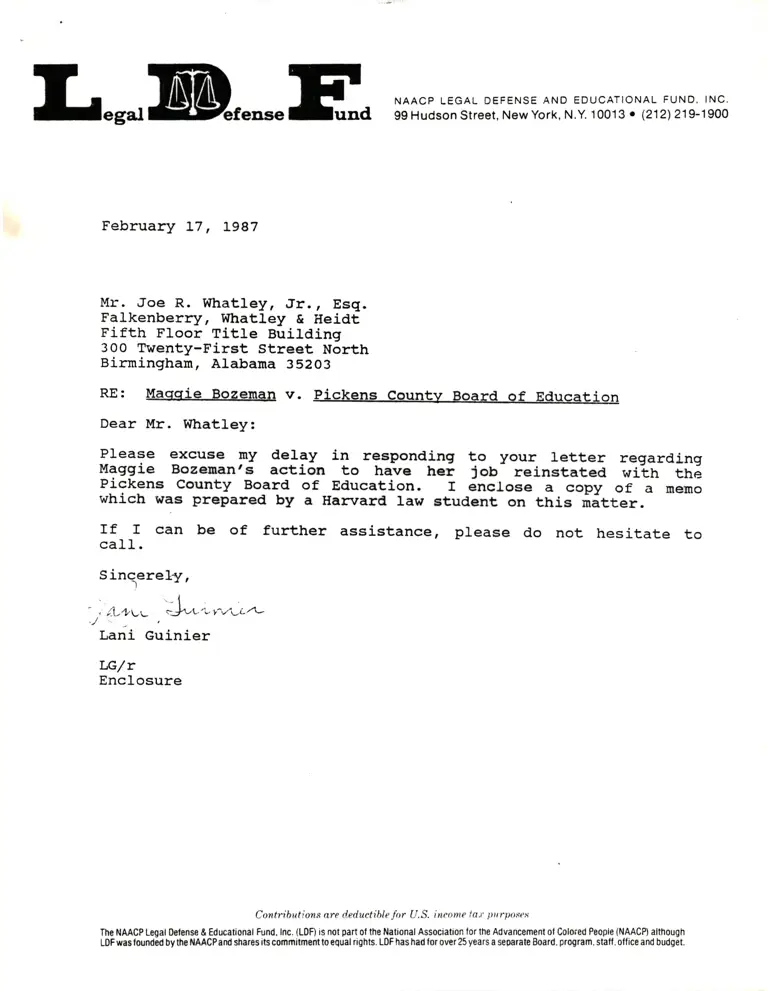

February 17, 1987

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman v. Pickens County Board of Education. Correspondences between Guinier and Whatley, 1987. 81f54321-f192-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4b6d5cc4-493f-4d98-9685-075d9efeb04d/correspondences-between-guinier-and-whatley. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

Lesa,E&renseH.

February L7, L987

Mr. Joe R. I{hat1ey, Jr., Esq.

Falkenberry, Whatley & Heidt

Fifth Floor Title Building

300 Twenty-First Street North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

RE: Mqggie Bozemqn v. pickens countv Board o.f Education

Dear Mr. Whatley:

Please excuse Py delay in responding to your letter regardingMaggie Bozeman's action to have hei Job- reinstated wiin th;Pickens county Board of Education. r enclose a copy of a meuowhlch rras prepared by a Harrrard law student on this nitter.

If f can be of further assistance, please do not hesitate tocal1.

S inqere{,

,/

Lani Guinier

LG/r

Enclosure

Contributions are deductible for U.S. ineome iat I)xrpos('.s

Th€ NAACP Legal 0etense & Educalional fund, lnc. (LDO is not part of the National Association lor the Advancement ol Colored People (NAACP) although

LDFwa6 rounded by the l,lAACPa]d shares its commitmont lo equal rights. LDF has had lor over 25 years a separate Board, program, stafl, otfice and budget.

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

gg Hudson street, New york, N.y. 1001 3 o (212) 219_1900

A-hv.- J-.,.. v^,./eLA-

JOHN C. FALKENBERRY

JOE R.V}IATLEY,JR.

FRANCES HEIDT

CMRLES F. NORTON, JR.

LA'iO OFFICES

FalrcxBERRY, WHarlrv I HErnr

FIFTH FLOOR TITLE BUILDINC

3OO TITENTY-FIRST STREET NORTH

BIRMINGHAM, AunaUa 35203

v

TELEPHONE

(205) 322-il00

August 19, 1986

Lani Guinier, Esquire

Legal and Education Defense Fund

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10015

Re: Maggie Bozeman v. Pickens County Board of Education

Dear Ms. Guinier:

We have been asked by the Alabama Education Association

to consider pursuing some action on behalf of Ms. Bozeman about

her termination, to attempt to recover damages and have her

reinstated in her job with the Board of Education. tvls. Bozeman

has informed me that you may have done some work on possible

civil claims which she might have. I would yery much

appreciate your either giving me a call or sending me whatever

research you have which might be of assistance.

Yours !ruly,

1ey, Jr.

JRWj r: mae

cc: Ms. Maggi.e Bozeman

Dr. Joe L. Reed