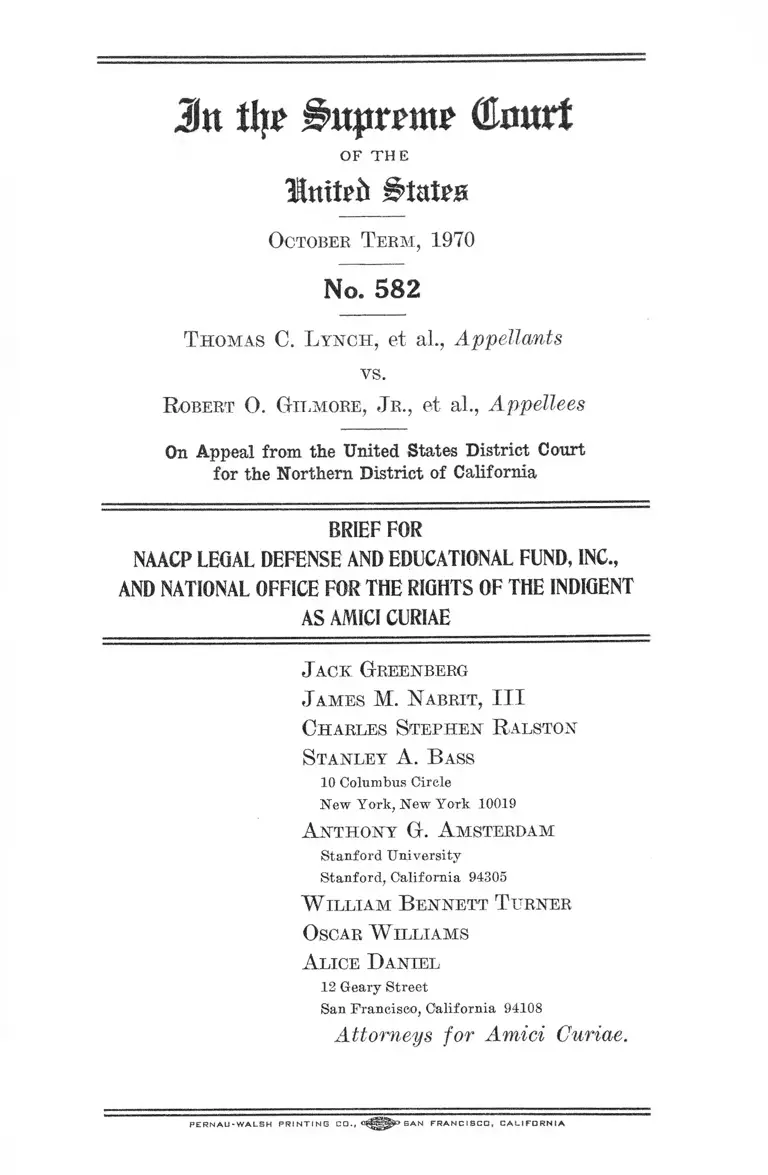

Lynch v. Gilmore, Jr. Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

June 17, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lynch v. Gilmore, Jr. Brief Amicus Curiae, 1971. 1e3af822-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4bc9762a-6284-42bd-afb1-0309e92959f5/lynch-v-gilmore-jr-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

Jtt tl|£ igorprone QJnurt

OF THE

O ctober T e r m , 1970

No. 582

T h o m a s C. L y n c h , et al., Appellants

vs.

R obert O. G il m o r e , J r ., et al., Appellees

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of California

BRIEF FOR

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

AND NATIONAL OFFICE FOR THE RIGHTS OF THE INDIGENT

AS AMICI CURIAE

J a c k G reenberg

J am es M. N ab hit, III

C h arles St e p h e n R alston

S t a n l e y A . B ass

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A n t h o n y G. A m sterd am

Stanford University

Stanford, California 94305

W il l ia m B e n n e t t T u rn er

O scar W il l ia m s

A lice D a n ie l

12 Geary Street

San Francisco, California 94108

Attorneys for Amici Curiae.

P E R N A U - W A L S H P R I N T I N G C O . , B A N F R A N C I S C O , C A L I F O R N I A

Table of Contents

Statement of interest of the amici ............................................. 1

Opinions below .............................................................. 3

Jurisdiction .................................................. 4

Question presented ...................................................................... 4

Summary of argument ................................................................ 4

Argument ...................................................................................... 7

I. Introduction ...................................................................... 7

A. The post-conviction plight of California prisoners 7

B. The decision of the court below ............................... 13

II. By depriving indigent prisoners of necessary legal

resources to challenge their convictions or sentences,

California, effectively denies them access to the courts 16

1. Significance of California post-conviction proceed

ings ................................................................ 20

2. Necessary assistance required to obtain a fair hear

ing on post-conviction claims ............................... 21

3. The legal resources provided by the state . . . . . . . . 25

III. California’s denial of necessary legal assistance to

indigent prisoners deprives them of equal protection of

the laws .................................................... 28

IV. The eleventh amendment does not bar the relief

ordered by the district court ........................................ 32

Conclusion ............... 34

Page

Table of Authorities Cited

Cases Pages

Anders v. California, 386 U.S. 738 (1967) ............................. 30

In re Banks, 4 Cal.3d 337, ..... P .2 d ..... (1971) .................. 10

Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 U.S........ , 91 S.Ct. 780 (1971)

................................................................................... 5,16,17,18,21

Burns v. Ohio, 360 U.S. 252 (1959) ......................................... 29,31

In re Chessman (1955) 44 Cal.2d 1, 278 P.2d 24 .................. 14

Cruz v. Beto, 391 F.2d 235 (5th Cir. 1968) ........................... 8

Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353 (1963).. .5, 7, 8,18,20, 29, 33

Draper v. Washington, 372 U.S. 487 (1963) ......................... 30

Bntsminger v. Iowa, 386 U.S. 748 (1967) ............................... 30

Gardner v. California, 393 U.S. 367 (1969) ..........................6,21,30

Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254 (1970) ................................... 33

Goodwin v. Cardwell, 432 F.2d 521 (6th cer, 1971) .............. 8

In re Greenfield, 11 Ca!.App.3d 563, 89 Cal.Rptr. 847 (1970)

.................................................................................................10, 24

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956) ..................17,18,29,33,34

In re Harrell, 2 Cal.3d 675, 470 P.2d 640 (1970) .................. 14,19

Ex parte Hull, 312 U.S. 546 (1941) ......................................... 16

Johnson v. Avery, 393 U.S. 483 (1969) ...................................

........................... ......................... 5,10,16,17,18,19, 24,25, 26, 31

Kaufman v. United States, 394 U.S. 217 (1969) ................... 16,20

Lane v. Brown, 372 U.S. 477 (1963) , ..................................... 29

Long v. District Court, 385 U.S. 192 (1966) ......................... 30

Marino v. Ragen, 332 U.S. 561 (1947) ................................... 22

Meltzer v. G. Buck LeCraw & Co., 39 U.S.L.W. 3483 (May 3,

1971) ........................................................................................ 17

Mempa v. Rhay, 389 U.S. 128 (1967) ..................................... 21

Mooney v. Holohan, 294 U.S. 703 (1935) ............................... 16

Nelson v. Peyton, 415 F.2d 1154 (4th Cir. 1969) . . . . 8

T able of A uthorities Cited iii

Pages

People v. Lyons, 46 IUL2d 172, 263 KE.2d 95 (1970) .......... 27

Peters v. Rutledge, 397 F.2d 731 (5th Cir. 1968) ..................13, 28

Pointer v. Texas, 380 U.S. 400 (1965) .................................. 24

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) .................................. 33

Rinaldi v. Yeager, 384 U.S. 305 (1966) ........................... 30,31,32

Roberts v. LaVallee, 389 U.S. 40 (1967) ............................... 30

Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962) ......................... 24

Rodriguez v. United States, 395 U.S. 327 (1969) .................. 20

In re Schoengarth, 66 Cal.2d 295 ............................................. 14

In re Shipman, 62 Cal. 226, 42 Cal.Rptr. 1 (1965) ................ 21

In re Smith, 3 CaL3d 192, 474 P.2d 969 (1970) ................ 10

Smith v. Bennett, 365 U.S. 708 (1961) .................................. 29

Still v. Fitzharris, 413 F.2d 977 (9th Cir. 1969) ................... 8

In re Swain (1949) 34 Cal.2d 300, 209 P.2d 793 .................. 14

Swann v. Charlotte-Meeklenburg Board of Education, .....

U.S........, 91 S.Ct. 1267 (1971) ............................................. 15,33

Swenson v. Bosler, 386 U.S. 258 (1967) ................................ 8

Turner v. Fouehe, 396 U.S. 346 (1970) ................................ 33

United States v. Simpson, 436 F.2d 163 (D.C. Cir. 1970) . . . 27

United States ex rel. Smith v. MeMann, 417 F.2d 648 (2d

Cir. 1969)' ................................................................................ 8,20

United States ex rel. Wissenfeld v. Wilkins, 281 F.2d 707

(2d Cir. 1960) ....................................................................... 23

In re Williams, 1 Cal.3d 168, 460 P.2d 984 (1969) ........ .. 9, 23

Williams v. Oklahoma City, 395 U.S. 458 (1969) ................ 30

Wilson v. Wade, 396 U.S. 282 (1970) ................................ 20

Statutes, Rules and Regulations

28 U.S.C. Section 1253 .............................................................. 4

28 U.S.C. Section 2281 .................................................... .. 4

28 U.S.C. Section 2284 .............................................................. 4

Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(e) ................................................................. 32

Ark. R. Grim. Pro. ID (Supp. 1969) ..................................... 11

Cal. Govt. Code Section 27706(a) (West Supp. 1971) . . . . 8

IV T able of A uthorities Cited

Pages

Cal. P. C. Section 1265 ................................. 21

Cal. P. C. Section 1475 ........................................... 22

Cal. P. C. Section 1508 ................................. 22

Ind. Rule P. C. 1(1) (1) (Burns Spec. Supp. 1970) (1961) 11

Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 14, §5506 (1964) .......................... 11

Mo.Sup.Ct. R. 27.26 (h) (i) ........................................................ 11

Mont. Rev. Code, Section 95-1004 (1969 Rpl. Vol.) .............. 11

N.C. Gen. Stat., Section 15-219 (Supp. 1969) ....................... 11

Ohio Rev. Code, Section 2953.24 (Page’s Supp. 1970) .......... 11

Ore. Rev. Stat., Section 138.590 (1969-70) ........... 11

S.D. Sess. Laws, ch. 121, Section 3 (1966) ........................... 11

Wyo. Stat. Ann., Section 7-408.4 (Supp. 1969) ................ 11

Other Authorities

Annual Report of the Director of the Administrative Office

of the United States Courts, 1969, Table C3 ..................... 12

1970 Annual Report to the Governor and the Legislature,

Judicial Council of California .............................................22, 24

Burger, Remarks on the State of the Federal Judiciary, 56

A.B.A. J. 929 (1970) ............................................................. 12

California Criminal Law Practice, California Continuing

Education of the Bar, 371-73 (1969) ................................. 22

5 Crim. L. Rptr. 2277-78 (1969) ............................................. 26

Crime and Delinquency in California 1969, California De

partment of Justice, Bureau of Criminal Statistics.......... 10

Criminal Appeals in California 1964-68, California Depart

ment of Justice, Bureau of Criminal Statistics .............. 8

Note, Federal Habeas Corpus, 83 Harv. L. Rev. 1038

(1970) ............................... ...................................................... 21,26

Jacob'and Sharma, Justice After Trial: Prisoners’ Need for

Legal Services in the Criminal-Correctional Process, 18

Kan. L. Rev. 498 (1970) .........................................22,25,26,27

Table of A uthorities Cited v

Krause, A Lawyer Looks at Writ Writing, 56 Cal. L. Rev.

371 (1968) ...............................................................................24,27

Lay, Problems of Federal Habeas Corpus Involving State

Prisoners, 45 F.R.D. 45 (1968) ............................................ 27

Michelman, On Protecting the Poor Through the Fourteenth

Amendment, 83 Harv. L. Rev. 7 (1969) ......................... 31

Oliver, Postconviction Applications Viewed by a Federal

Judge—Revisited, 45 F.R.D. 199 (1968) ......................... 27,28

Prison Writ Writing: Three Essays, 56 Cal. L. Rev. 342

(1968) ...................................................................................... 20

The Recorder, June 11, 1971, at 1, col. 7 ............................. 26

Representation of Indigent Criminal Defendants in Appel

late Courts, 1970 Annual Report to the Governor and the

Legislature, Judicial Council of California ......................... 9,12

Pages

Note, State Post-Conviction Remedies and Federal Habeas

Corpus, 12 William & Mary L. Rev. 149 (1970) ................

Witkin, Cal. Grim. Proc. 764-65 (1963) .................................

22

22

Jn % jg’ujrrattr ©nttrt

OF TH E

O ctober T e r m , 1970

No. 582

T h o m a s C. L y n c h , et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

R obert 0 . Gil m o r e , J r ., et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of California

BRIEF FOR

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

AND NATIONAL OFFICE FOR THE RIGHTS OF THE INDIGENT

AS AMICI CURIAE

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF THE AMICI

The NAACP Legal Defease and Educational Fund,

Inc. (the “ Legal Defense Fund” ) is a non-profit cor

poration formed in 1939 under the laws of the State

of New York. It was founded to assist black people

who suffer injustice by reason of race or color to

secure their basic rights through the legal process.

The Legal Defense Fund is independent of other

organizations and is supported by contributions from

the public.

The central purpose of the Legal Defense Fund is

the legal eradication of practices in our society that

bear with discriminatory harshness upon black people

and upon the poor, deprived and friendless, who too

often are black people. To further this purpose, in

1967 the Legal Defense Fund established a separate

corporation, the National Office for the Rights of the

Indigent (“ NORI” ), having among its objectives the

provision of legal representation to the poor in indi

vidual cases and the advocacy before appellate courts

of changes in legal doctrine unjustly affecting the

poor.

The Legal Defense Fund receives a very large

volume of pleas for assistance from prisoners incar

cerated in penal institutions and jails throughout the

nation. Prisoners call upon the Legal Defense Fund

to help in challenging constitutional error in their

convictions and sentences, in coping with their civil

problems (many of them relating to their indigency)

and in bringing suits to achieve reform of outmoded

and inhumane prison practices. The Legal Defense

Fund and NORI cannot begin to provide representa

tion or even counselling for the huge numbers of

prisoners seeking their assistance.

The San Francisco office of the Legal Defense Fund

receives a great number of requests for help from

prisoners incarcerated in the State of California.

Again, the prisoners request assistance and informa

tion not only with regard to the validity of their con

3

victions and sentences, but also concerning their per

sonal civil problems and their difficulties vis-a-vis the

prison administration. 'They frequently ask us to

reproduce and send them court decisions not other

wise available to them. While the Legal Defense

Lund attempts to respond to as many of these pleas

for assistance as possible, our limited staff and re

sources simply do not permit us to help in very many

cases, regardless of whether the cases are meritorious.

Accordingly, the Legal Defense Fund has a direct,

interest in having the states recognize their obligation

to provide necessary legal resources for the persons

whom they choose to imprison.

The Legal Defense Fund believes that the decision

of the court below is sound as a matter of law and

policy in recognizing that the state’s denial of neces

sary legal resources to prisoners cannot be squared

with the fundamental right of access to the courts,

where such access is the only means of redressing a

deprivation of liberty without due process. For this

reason, we respectfully present our views on the issue

before the Court. The parties have consented to the

filing of a brief by amici, and copies of their letters

of consent are being submitted to the Clerk with this

brief.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the three-judge District Court, filed

May 28, 1970, is reported at 319 F.Supp. 105 and is

printed in the Appendix at pp. 92-106. The opinion

4

of the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit on the

jurisdictional question is reported at 400 F.2d 228

and is printed in the Appendix at pp. 28-32. The

order of this Court denying certiorari to review the

decision of the Court of Appeals is reported at 393

U.S. 1092 (1969).

JURISDICTION

This is an appeal from an order of a three-judge

District Court convened pursuant to- 28 U.S.C. Sec

tions 2281 and 2284. On the assumption that the

court below had jurisdiction to act as a statutory

three-judge court, the jurisdiction o f this Court on

direct appeal is conferred by 28 U.S.C. Section 1253.1

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether, by depriving indigent prisoners of legal

resources necessary to present post-conviction chal

lenges to errors in their convictions or sentences,

California effectively denies them access to the courts

in violation of the due process and equal protection

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Convicted felons in California prisons whose con

victions may be tainted by fundamental error face

iBoth parties to this appeal have previously filed briefs support

ing- the jurisdiction of this Court. Amici do not intend to brief

this question.

0

special difficulties in obtaining judicial review of their

claims. California has not implemented Douglas v.

•California, 372 U.S. 353 (1963), by requiring that

convicted defendants be notified either o f their right

to appeal or of their right to assigned counsel. As a

consequence, many defendants fail to appeal through

ignorance of their rights, and must rely on post

conviction proceedings as the only means of challeng

ing the legality of their convictions. Despite the

crucial nature of these proceedings and the urgency

of the prisoners’ need, California has not adopted

any of the techniques suggested by this Court in

Johnson v. Avery, 393 II.S. 483 (1969), for providing

essential legal assistance to prisoners seeking access

to the courts.

Due process of law requires that prisoners be

afforded effective access to the courts to challenge

convictions obtained in violation of their constitu-

tional rights. Depriving them of the legal assistance

necessary for preparing and presenting these claims

effectively denies prisoners access to the only forums

empowered to settle their disputes. Boddie v. Con

necticut, 401 U.S........ , 91 S. Ct. 789 (1971). State

officials may not obstruct access to the courts and,

absent a countervailing state interest of overriding

significance, due process requires that prisoners be

given a meaningful opportunity to be heard. In short,

post-conviction proceedings must be more than a

formality; and the State must insure that those who

cannot help themselves have reasonably adequate as

sistance in preparing and filing post-conviction plead

ings. Johnson v. Avery, 393 U.S. 483 (1969).

6

The court below carefully considered what is

required to obtain a hearing on a post-conviction

petition and found that California prisoners were

effectively barred from the courts by the denial of

legal resources essential to the presentation of their

claims. It held that the State’s asserted interest in

standardization and economy was not sufficient to

justify depriving state prisoners of a meaningful

opportunity to be heard. However, the court did not

order the State to provide “ expensive law libraries”

or appointed counsel for prisoners. It simply required

the state officials to submit a plan for providing indi

gent prisoners with the legal assistance necessary to

present arguably meritorious claims in a manner that

avoids summary dismissal.

California imprisons only a small proportion of

persons convicted of felonies. 'Since those who are

not incarcerated are free to seek gainful employment

and hire an attorney, or to make use of the other

legal resources available in free society; and since

some imprisoned felons have sufficient monetary re

sources to retain an attorney to counsel them, do their

research and draft their petitions, the court below

correctly held that California denies equal protection

to indigent prisoners. This Court has consistently

made plain that indigent prisoners cannot be deprived

of meaningful and effective access to the courts by

economic barriers, and this is true in post-conviction

proceedings as well as on direct appeal. See, e.g.,

Gardner v. California, 393 H.S. 367 (1969).

Having found that indigent prisoners in California

were being deprived of due process and equal protec

7

tion of the laws by the State’s refusal to provide legal

resources essential for effective access to the courts,

the court below properly directed the state officials

to submit a plan that would assure such access. The

State can comply with the district court’s order by

utilizing one or more of the easily available, relatively

inexpensive techniques for providing prisoners with

necessary assistance. Use of such techniques would not

only assure prisoners effective access to the courts,

but would lighten the burden on state and federal

courts in processing their applications.

The Eleventh Amendment, does not bar the relief

ordered by the district court, because this Court has

repeatedly made plain that, in enforcing the Four

teenth Amendment, the federal courts may grant in

junctive relief having the effect of requiring states

to expend public funds in order to bring public pro

grams into compliance with constitutional guarantees.

ARGUMENT

I. INTRODUCTION

A. The Post-Conviction Plight of California Prisoners

Those confined to California state prisons face

special difficulties with regard to their ability to

obtain judicial relief from illegality in such confine

ment. Despite this Court’s decision in Douglas v.

California, 372 U.S. 353 (1963), California does not

have any requirement, whether by statute, rule of

court or judicial decision, that convicted criminal

defendants be notified either of their right to appeal

8

or of their right to assigned counsel on appeal.2 In

these circumstances,, it is not surprising that the pro

portion of criminal defendants who appeal from their

convictions is very small. For the years 1964 through

1968, only 5% of defendants convicted of felonies in

California appealed their convictions. California De

partment of Justice, Bureau of Criminal Statistics,

Criminal Appeals in California, 1964-1968, p. 12. The

range is from1 less than 1% of those who entered

pleas of guilty to more than one-third of those con

victed by juries. Id. Given the fact that so few de

fendants appeal and the fact that the State does not

require notification of the right to appeal with as

signed counsel, it must be assumed, that, at least some

of those who do not appeal fail to do so because of

ignorance of their rights.3 It is not clear whether

California law provides a remedy for a defendant

who thus loses his right to appeal. See Still v. Fits-

Jiarris, 413 F.2d 977 (9th Cir. 1969).

Moreover, even where a defendant does succeed in

filing notice of appeal, the State fails in many eases

zCf. United States ex rel. Smith v. McMann, 417 F.2d 648 (2d

Cir. 1969), where the Second Circuit en banc held that such, a fail

ure to provide procedures implementing Douglas violates defend

ants’ constitutional rights.

Cal. Govt. Code Section 27706(a) (West Supp. 1971) defines

the duty of the Public Defender in representing an indigent de

fendant. He is not required to prosecute an appeal to a higher

court unless “ in his opinion, the appeal will or might reasonably

be expected to result in the reversal or modification of conviction.”

If he decides not to appeal, he has no obligation to file a notice of

appeal, or to advise the defendant of Ms right to appeal or to

obtain other counsel.

3Cf. Swenson v. Bosler, 386 XJ.S. 258, 260 (1967) ; Goodwin v.

•Cardwell, 432 F.2d 521 (6th Cir. 1971); Nelson v. Peyton, 415

F.2d 1154 (4th Cir. 1969); Cruz v. Beta, 391 F.2d 235 (5th Cir.

1968).

9

to provide for adequate representation by court-

appointed counsel. The rate of compensation is ex

tremely low and it is frequently impossible to obtain

experienced counsel. A report of the California

Judicial Council states that

“ Most of the volunteers are recent admittees of

the bar with little or no experience in the field

of criminal law. As a result, the quality of repre

sentation is uneven and sometimes inadequate. In

testimony before a legislative committee it was

estimated that 30 to 40 percent of the appeals

filed for indigents in criminal cases fell ‘ below

an acceptable level of quality.’ ” See Judicial

Council of California, 1970 Annual Report to the

Governor and the Legislature, p. 16.

The inevitable consequence of the failure of the

State to provide adequate machinery for resolving

on direct appeal defendants’ claims of error in

criminal convictions or sentences is that many such

claims, including federal constitutional claims, must,

be presented in post-conviction collateral proceedings

such as coram nobis and habeas corpus. Of course,

even where defendants were adequately represented

on direct appeal, claims of error dehors the record

necessarily must be raised in collateral proceedings.

In short, there is a heavy burden on post-conviction

proceedings in California. Convicted felons are fre

quently forced to resort to collateral proceedings in

order to correct fundamental errors in their convic

tions or sentences.4

4See, e.g., In re Williams, 1 Cal.Sd 168, 460 P.2d 984 (1969),

where the indigent defendant who had been represented by the

Public Defender and failed to file timely notice of appeal filed

10

The State of California imprisons only a small

proportion of persons convicted of felonies.5 The large

number of convicted felons who are not in prison but

who are placed on probation or who have been re

leased on parole are free to seek gainful employment

and to earn sufficient income to engage an attorney

to represent them. They are also free to consult public

law libraries at their leisure and to make use of what

ever legal resources are available in the “ free world,”

including legal services offices funded by the federal

Office of Economic Opportunity. But the convicted

felons whom California chooses to imprison are left

virtually without any legal resources for preparing

and conducting post-conviction collateral proceedings.

California has not adopted any of the techniques

suggested by this Court in Johnson v. Avery, 393 U.S.

483 (1969), for providing legal assistance to prisoners

three post-conviction proceedings before he— and the California

Supreme Court—realized he had pleaded guilty to a crime he did

not commit. When the indigent defendants in In re Smith, 3 Cal.

3d 192, 474 P.2d 969 (1970), and In re Greenfield, 11 Cal.App.3d

536, 89 Cal.Rptr. 847 (1970), finally succeeded in having their

convictions overturned via in propria persona applications, the

courts deplored the inadequacy of their court-appointed counsel on

direct appeal. In Greenfield, the court said, “ A half hour of rudi

mentary research . . . would have revealed a defense crucial to

petitioner’s case.” 11 Cal.App.Sd 544. See also In re Banks, 4 Cal.

3d 337,.......P. 2 d ......... (1971).

5For example, in 1969, there were 50,568 persons charged with

felonies who were convicted in California courts. Of this number,

19,470 (38.5%) were given probation, 13,718 (27.1%) were given

probation and a jail term and 7,020 (13.9%) were sentenced to

short terms in county jails. Only 4,940 (9.8%) were sentenced to

prison. California Department of Justice, Bureau of Criminal Sta

tistics, Crime and Delinquency in California- 1,969, pp. 33, 108.

Moreover, of the 34,851 persons1 who on December 31, 1969, were

under the jurisdiction of the California Department of Correc

tions, 11,833 (33.9%) were at large on parole. Only 23,018 were

imprisoned in penal institutions under the jurisdiction of the De

partment. Id. at p. 37.

11

ill the preparation of their post-conviction pleadings:

unlike many states, California makes no provision for

representation by a public defender or legal aid

society in any proceedings after direct appeal6; the

State has not adopted a program for utilizing law

students in interviewing and advising prison inmates;

the State has not undertaken any program whereby

members of any bar association visit prisons to con

sult with prisoners concerning their cases; and the

State has not trained able and literate prisoners to

render assistance to others. 393 U.S. at 489.7

The Department of Corrections does provide a few

law books in each of its twelve institutions but, as the

court below found, these “ libraries” are grossly inade

quate even for the limited purpose of researching

claims to be presented in post-conviction criminal

proceedings. Indeed, this lawsuit was precipitated by

the promulgation of a new regulation (App. 41) pur

porting to “ standardize” the list of law books per

mitted in California prisons, but providing for the

confiscation of law books or materials not on the

prescribed list—a veritable book burning that would

«A number of states have adopted working systems for appointed

counsel in proceedings subsequent to appeal. See, e.g., Ark. R.

Grim. Pro. ID (Supp. 1969); Ind. Rule P.C. 1(1) (1) (Burns

Spec. Supp. 1970); Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 14, § 5506 (1964);

Mo. Sup. Ct. R. 27.26; Mont. Rev. Code § 95-1004 (i960 Rpl. Y o l.) ;

N.C. Gen. Stat. § 15-219 (Supp, 1969); Ohio Rev. Code §2953.24

(Page’s Supp. 1970); Ore. Rev. Stat. § 138.590 (1969-70); S.D.

Sess. Laws eh. 121, § 3 (1966) ; Wyo. Stat. Ann. § 7-408,4 (Supp.

1969).

7Indeed, California prohibited prisoners from helping each other

with any legal work until after this Court’s decision in Johnson v.

Avery.

12

deprive California prisoners of a portion of the few

legal materials they already have.

The action of the State of California and its De

partment of Corrections in incarcerating criminal

defendants and then depriving them of the legal

wherewithal for preparing and presenting constitu

tional claims to the courts takes its toll in swamping

the courts, including the federal courts, with a con

tinuing flood of in propria persona pleadings raising-

in piecemeal fashion the various claims that prisoners

on their own can think of. As Chief Justice Burger

has noted, prisoner reliance on federal courts to re

view state convictions and sentences produces not

only a drain on the limited resources of the federal

courts but also a strain on the relations between the

parallel court systems. Remarks on the State of the

Federal Judiciary, 56 A.B.A.J. 929 (1970). In fiscal

year 1968-1969 alone, California prisoners filed 1,029

cases in the federal courts in California. Annual Re

port of the Director of the Administrative Office of

the United States Courts, 1969, Table C3, p. 213. In

the same fiscal year, they also filed 6,200 post-convic

tion petitions in the state courts of California.

Judicial Council of California, 1971 Annual Report

to the Governor and the Legislature, 31. There is no

way of knowing how many of the pleadings were

frivolous or repetitious, or of knowing how much

valuable time of judges and clerks was taken up in

processing these applications. What is known is that

a substantial amount of judicial time of both state

and federal courts has been consumed in deciphering

prisoner applications from California. It is not sur

13

prising that many applications get short shrift and

it is likely that many meritorious petitions are over

looked in the flood of frivolous ones. Cf. Peters v. Rut

ledge, 397 F.2d 731, 738 (5th Cir. 1968).

B. The Decision of the Court Below

The three-judge federal district court found that

indigent prisoners in California were effectively

denied access to the courts for the purpose of pursu

ing existing post-conviction remedies. The court care

fully considered the State’s argument that law

“ libraries” must be stringently limited in the interest

of standardization and economy, and held that the

paramount federal right of access to the courts must

prevail. The court rejected the notion that an ade

quate opportunity for a prisoner to challenge his

conviction or sentence in available state and federal

forums is a “ privilege” rather than a right and found

unrealistic the State’s argument that in post-eonvic-

tion proceedings a prisoner requires no legal expertise

and need only state the facts of his case in order to

gain a judicial hearing. The court said that much

more than recitation of simple “ facts” is required to

obtain relief by habeas corpus:

“ A1 prisoner should know the rules concerning

venue, jurisdiction, exhaustion of remedies, and

proper parties respondent. He should know

which facts are legally significant, and merit

presentation to the Court, and which are irrele

vant or confusing. . . . ‘ Access to the courts,’

then, is a larger concept than that put forward

by the State. It encompasses all the means a

defendant or petitioner might, require to get fair

14

hearing from the judiciary on all charges brought

against him or grievances alleged by him.” 319

F.Supp. at 110 (App. 100).

It must be remembered that two of the three mem

bers of the court below are district judges who are

confronted with California prisoner applications

every day, and are intimately familiar with what it

takes to get a judicial hearing in California.8

The court below held that by denying indigent

prisoners the necessary legal resources to prepare an

application for post-conviction relief, California effec

tively denied them access to the courts and equal

protection of the laws. Contrary to the Attorney

GreneraTs assertion in this Court, however, the

district court did not order the state officials “ to

furnish prison inmates with extensive law libraries”

or to provide prisoners with “ professional or quasi

professional legal assistance.” The court below spe

cifically refrained from undertaking “ the task of

devising another system whereby indigent prisoners

are given adequate means of obtaining the legal

expertise necessary to obtain judicial consideration

8The California Supreme Court also disagrees with the At

torney General’s argument that a prisoner need only state “ facts”

in order to obtain judicial relief. Thus,

“ This court has itself recognized that some kind of access to

legal materials is necessary to the preparation of any effective

application for relief. ‘ [A]lthough [an application] should

ordinarily be predicated on a. full and honest statement of

the facts which the inmate believes give rise to a remedy

(In re Chessman (1955) 44 Cal.2d 1, 10 (278 P.2d 24); In re

Swam (1949) 34 Cal.2d 300, 302, 304 (209 P.2d 793)), the

relevance of certain facts may not be apparent to him until

he has done some legal research on the point.’ (In re Schoen-

garth, supra. 66 Cal.2d 295, 305).” In re Harrell, 2 Cal.3d

675, 695, 470 P.2d 640, 653 (1970).

15

of alleged grievances cognizable by the courts” (App.

104). The court noted that “ the alternatives open to

the state are legion,” and listed a few of the means

by which other states or prison systems have provided

for the legal needs of their charges (App. 101). In

stead of enjoining the California officials to provide

a library, or appointed counsel, or some other spe

cific means of ensuring that prisoners are not left

legally destitute, the court below simply ordered the

officials to file new regulations providing either for

expanded law libraries or for “ some new method of

satisfying the legal needs” of California prisoners

(App. 104-05).° Thus, the shape of the legal assistance

program is to be decided by the State.9 10 Rather than

submitting a plan or new regulations to the court

below, however, the state officials have appealed to

this Court, contending in effect that they are not

constitutionally required to provide any legal re

sources at all to indigent California prisoners.

9The court also enjoined the officials from destroying or re

moving law books and materials already available in California

prisons (App. 105-06).

10As this Court has recently said with respect to the equity

powers of federal courts where constitutional violations have been

demonstrated,

“ Once a right and a violation have been shown, the scope of

a district court’s equitable powers to remedy past wrongs is

broad, for breadth and flexibility are inherent in equitable

remedies. # *

“ As with any equity case, the nature of the violation deter

mines the scope of the remedy.” Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklen

burg Board of Education,....... U.S..........., 91 S. Ct. 1267, 1276

(1971).

Here, the court below exercised its broad equity powers in the most

restrained manner possible, by directing the state officials to de

velop their own appropriate methods rather than by mandating

specific conduct or programs by the officials.

16

II. BY DEPRIVING- INDIGENT PRISONERS OF NECESSARY

LEGAL RESOURCES TO CHALLENGE THEIR CONVICTIONS

OR SENTENCES CALIFORNIA EFFECTIVELY DENIES THEM

ACCESS TO THE COURTS.

The constitutional prohibition against depriving a

man of liberty without due process of law has, as a

necessary corollary, the requirement that prisoners be

afforded access to the courts to- permit setting aside

convictions obtained in violation of their federal con

stitutional rights. See, e.g., Kaufman v. United States,

394 U.S. 217, 226 (1969) ; Johnson v. Avery, 393 U.S.

483 (1969) ; Mooney v. Holohan, 294 U.S. 703, 713

(1935).

It has long been clear that the paramount interest

in assuring prisoners access to the courts to present

their federal claims invalidates prison regulations

which effectively impair that right. Ex parte Hull,

312 U.S. 546 (1941) . Not only may state officials not

obstruct access to the courts, but “ due process re

quires, at a minimum, that absent a countervailing

state interest of overriding significance, persons forced

to settle their claims of right and duty through the

judicial process must be given a meaningful oppor

tunity to be heard.” Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 U.S.

..... , ......, 91 S.Ct. 780, 785 (1971). The Court in

Boddie, relying on precedents established in the

criminal defense context, held that due process of

law prohibits a state from denying access to its courts

to indigents seeking judicial dissolution of their mar

riage solely because of their inability to pay court

fees and costs. The Court reasoned that where the

“ judicial proceeding becomes the only effective means

17

of resolving* the dispute at hand . . . denial of a

defendant’s full access to that process raises grave

problems for its legitimacy.”11

In Johnson v. Avery, 393 II.S. 483 (1969), the

Court recognized that full access to the courts for

many prisoners is meaningless unless some form of

legal assistance is provided. The Court emphasized

that “ for the indigent as well as for the affluent

prisoner, post-conviction proceedings must be more

than a formality.” 393 U.S. at 486. The Court held

that unless “ the state provides some reasonable

alternative to assist inmates in the preparation of

petitions for post-conviction relief” it may not bar

inmates from furnishing assistance to other inmates.

Mr. Justice White, dissenting, would not have struck

down the anti-prisoner assistance regulation but

would have ruled in a proper case that “ the state

must provide access to the courts by insuring that

those who cannot help themselves have reasonably ade

“ Tlie Court in Boddie found insufficient the state’s asserted in

terest in its fee and cost requirements as a mechanism of resource

allocation or cost recoupment, relying on Griffin v. Illinois, 351

U.S. 12 (1956). The state interest did not constitute a “ sufficient

countervailing justification” for denying the indigents an op

portunity to be heard.

Mr. Justice Black, dissenting, distinguished civil lawsuits from

criminal prosecutions, stating that “ because of this great govern

mental power the United States Constitution has provided special

protections for people charged with crime.” But as to cases fol

lowing Boddie, Mr. Justice Black has noted that “ once the right

to unhampered access to the judicial process has been established,

that right is diluted unless the indigent litigant has an opportu

nity to assert and obtain review of the errors committed at trial.

. . . [Tjhere cannot be meaningful access to the judicial process

until every serious litigant is represented by competent counsel.”

Meltzer v. G. Buck LeCraw cfe Co., 39 U.S.L.W. 3483, 3484 (Mav

3, 1971).

18

quate assistance in preparing their post-conviction

papers.” 393 U.S. at 502. This is precisely what the

court below has required the California officials to

do in the instant case. Indeed, Mr. Justice White’s

opinion in Johnson states what is basically at stake

in the instant case:

“ The illiterate or poorly educated and inexperi

enced indigent cannot adequately help himself

and . . . unless he secures aid from some other

source he is effectively denied the opportunity to

present! to the courts what may be valid claims

for post-conviction relief.” 393 U.S. at 498.

This Court’s decisions in Boddie and Johnson, and

the earlier decisions in Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12

(1956), and Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353

(1963), teach that the states cannot deny to indigents

the necessary means for obtaining a fair hearing of

their possibly valid constitutional claims. The Court’s

decisions have recognized practical reality not merely

by striking down absolute barriers to the courts but

by declaring that effective access to the judicial

process is required where fundamental interests like

liberty are at stake. For example, in Douglas, as here,

the prisoner was not totally barred from tiling his

appeal; and in Johnson, as here, he was not totally

barred from filing his writ. But in both cases, as here,

the state practice prevented effective use of the judi

cial process. I f a prisoner with a meritorious claim

is unable to present it to the court in a way that

avoids summary dismissal, he is denied access to the

courts. Jailhouse lawyers were permitted by Johnson

19

because of t-lie function they serve—as tools enabling

prisoners to bring their claims before the courts. Mr.

Justice White noted in Johnson that “ unless the help

the indigent gets from other inmates is reasonably

adequate for the task, he will be as surely and effec

tively barred from the courts as if he were accorded

no help at all.” 393 U.S. at 499. As foreseen by Mr.

Justice White, the district court in the present case

foimd that other tools are needed as well.12 Just as

the paramount interest in making the courts fully

available for the resolution of constitutional claims

compelled the result ha Johnson, it requires affirm

ance of the decision in the present case. Post-convic

tion remedies theoretically available to all in Cali

fornia are not in fact available if the State denies

indigents the legal wherewithal to use them. Because

the State denies the prisoner both his livelihood (e.g.,

to hire a lawyer) and his liberty (e.g., to use a public

law library or consult an OEO legal services attor

ney), the State has erected very effective barriers to

the judicial process—-unless the State furnishes

alternative sources of legal help.

In determining whether California denies im

prisoned indigents effective access to the courts, con

sideration should be given to (1) the special signifi

cance of post-conviction proceedings for California

12The California Supreme Court has also recognized that John

son v. Avery “ heralds the advent of new principles governing the

question of prisoner access to legal materials. . . . [W ]e are cog

nizant that the principles of Johnson may, in a proper case, re

quire a judicial assessment of the adequacy of prison libraries to

permit legal research of a minimum degree of effectiveness.” In

re Harrell, 2 Cal.3d 675, 695, 470 P.2d 640, 653 (1970).

20

prisoners, (2) the legal resources required for

prisoners to make effective use of such proceedings,

and (3) the legal resources actually provided by the

State.

1. Significance of California Post-Conviction Proceedings

As this Court noted with regard to federal col

lateral proceedings in Kaufman v. United States, 394

U.S. 217, 226 (1969), “ adequate protection of consti

tutional rights relating to the criminal trial process

requires the continuing availability of a mechanism

for relief.” The need for post-conviction mechanisms

for relief in California is especially strong because,

as noted above,13 the State has not provided proce

dures to implement the decision in Douglas v. Cali

fornia, 372 U.S. 353 (1963). Consequently, many con

victed felons lose through inadvertence their right to

appeal. They are, indeed, in precisely the same posi

tion as the would-be appellant in California before

this Court’s decision in Douglas—-they are left to

shift for themselves in identifying errors in their

trial and making their initial presentation to the

court.14 See Prison Writ Writing: Three Essays, 56

Cal.L.Rev. 342, 363, 373 (1968); Cf. Rodriguez v.

United States, 395 U.S. 327, 330 (1969). Without

13See pp. 7-8, supra.

14C/. United States ex rel. Smith v. McMann, 417 F.2d 648, 658

(2d Cir. 1969), where Judge Friendly observed that “ a state’s

duty may sometimes be so compelling that continued inaction can

fairly be regarded as violating the Fourteenth Amendment.” In

Wilson v. Wade, 396 U.S. 282, 286 (1970), this Court left open

the question whether there are any circumstances in which the

Constitution requires the State to provide an indigent with a free

transcript to aid him to prepare a petition for collateral relief.

21

some form of legal assistance, they will find them

selves excluded “ from the only forum effectively em

powered to settle their disputes.” Boddie v. Connecti

cut, 401 U.S....... , ..... , 91 S.Ct. 780, 785 (1971).

2. Necessary Assistance Required to Obtain A Fair Hearing on

Post-Conviction Claims

The California Supreme Court has recognized that

in a post-conviction proceeding, “ the questions that

may be raised . . . are as crucial as those that may

be raised on direct appeal.” In re Shipman, 62 Cal.2d

226, 231, 42 Cal.Rptr. 1, 4 (1965) ; cf. Gardner v. Cali

fornia, 393 U.S. 367, 370 (1969). Nevertheless, coun

sel is not appointed in such proceedings unless the

petitioner makes “ adequate factual allegations stating

a prima facie case” for relief.15 62 Cal.2d at 232, 42

Cal.Rptr. at 5. Given the substantiality and the possi

ble complexity as well as the variety of the issues

that may be presented collaterally, it is very unlikely

that the average prisoner is capable on his own of

stating a prima facie case. The threshold problem for

the prisoner is to ascertain whether state coram nobis

or state habeas corpus procedures should be invoked.18

^ Amici believe that the decision below can be affirmed without

reaching, or even approaching, the question whether prisoners have

a constitutional right to counsel in some or all posit-conviction pro

ceedings. But see Mempa v. RJiay, 389 U.S. 128, 134 (1967), where

the Court, analyzed prior right-to-counsel decisions that “ clearly

stand for the proposition that appointment of counsel for an in

digent is required at every stage of a criminal proceeding where

substantial rights of a criminal accused may be affected.” See also

Note, Federal Habeas Corpus, 83 Harv. L. Rev. 1038, 1202-05

(1970).

i«a petition for a writ of error coram nobis (Cal. Penal Code,

Section 1265), is properly filed in the court of conviction. The

conditions for its issuance are (1) an error of fact existing at the

22

Where habeas corpus is appropriate, the petitioner

has his choice of three state forums, the Superior

Court, the Court of Appeal or the Supreme Court.

California Penal Code, Sections 1475, 1508; W ithin,

Gal. Grim. Proc. 764-65 (1963). All three courts have

original habeas jurisdiction and it is not necessary

to file first in a lower court. Id. In fiscal year 1968-69,

about 6,200 post-conviction applications were filed, of

which 3,814 were filed in Superior Court, 1,051 in the

Court of Appeal and 1,345 in the Supreme Court.

Judicial Council of California, 1970 Annual Report

to the Governor and the Legislature, 36. Of the ap

proximately 6,200 applications, about 5,300 were

time of judgment; (2) the fact does not appear of record or go

to the merits of the issues tried; (3) it was not presented at trial

for excusable reasons; and (4) knowledge of the fact would have

prevented rendition of the judgment. See iCalifornia Criminal Law

Practice, California Continuing Education of the Bar, 371-73

(1969). Habeas corpus, on the other hand, is applied for in the

court having jurisdiction over the prison, and serves its tradi

tional purpose of inquiring into the lawfulness of the conviction.

As a practical matter, untutored prisoners experience difficulty in

determining whether eorarn nobis or habeas corpus is the appropri

ate vehicle for raising the “ factual issue” which they claim in

validates their conviction, and since mislabelling results in filing

in the wrong court, an erroneously labelled claim is likely to be

dismissed without explanation, regardless of its substantive merit.

For an extreme example of the difficulties! encountered by pris

oners in states which have not enacted modem post-conviction

procedures, see Marino v. Bagen, 332 U.S. 561 (1947). Only a

handful of states have done so. See generally, Note, State Post-

Conviction Remedies and Federal Habeas Corpus, 12 William &

Mary L.Rev. 149 (1970).

The Emory Law School Legal Assistance For Inmates Program

found that some inmates did not even know in what court they

had been convicted, and that many did not know the exact nature

of the crime for which they were convicted, or the nature of the

sentence imposed. See Jacob and Sharma, Justice After Trial:

Prisoners’ Need For Legal Services In the Criminal-Correctional

Process, 18 Kan. L. Rev. 493, 621 n. 723 (1970). This is con

sistent with the experience of amici in attempting to assist Cali

fornia prison inmates.

23

denied without either a hearing or a written opinion.

Id. at 31. Thus, the typical petitioner received only

a postcard stating that his petition wras summarily

denied, with no clue as to the ground for denial. Id.

at 34, 37. The typical state petitioner in California

has no way of knowing whether he has been denied

because of some techical defect in his application

(e.g., incorrect venue), a failure to state some ma

terial fact, general incomprehensibility of the peti

tion, or reliance on a legal theory rejected by eases

or statutes he has never heard of.

The Attorney General asserts here, as he did below,

that the petitioner need only state the “ facts” of his

ease in order to obtain a judicial hearing. The court,

below, however, composed of judges who know what

it takes to gain a post-conviction hearing in a busy

trial court, exposed the utter unreality of the Attor

ney General’s position (App. 100). Even assuming

that the untutored prisoner can clear all the technical

and jurisdictional hurdles, he must know which facts

to present to the court. Even an educated layman is

unlikely to be able to differentiate the legally relevant

facts in his case. Left, to his owm resources, the

prisoner is likely to omit essential facts, or to bury

them in a mass of irrelevant detail.17 This is particu-

17Cf. United States ex rel. Wissenfeld v. Wilkins, 281 F.2d 707,

715 (2d Cir. 1960), where the issue was the need for counsel at a

post-eonvietion hearing. The court said: “ . . . rarely will a. prisoner

have sufficient ability or training to recognize the facts which are

important to his1 case or present his side of the dispute in an or

derly manner.”

In In re Williams, 1 Cal.3d 168, 460 P.2d 984 (1969), the pris

oner’s third petition for habeas corpus was granted. His two un

successful petitions had been based on erroneous legal theories, and

24

laxly true when the essential “ fact” is not part of the

criminal transaction itself, but rather concerns the

constitutionality of the criminal statute, e.g., Robin

son v. California, 370 U.'S. 660 (1962), or the omis

sion of a procedural protection essential to the in

tegrity and reliability of the fact-finding process, e.g.,

Pointer v. Texas, 380 U.S. 400 (1965). In short, “ it

is necessary to understand what one’s rights are be

fore it is possible to set out in a petition the facts

which support them. . . .” Johnson v. Avery, 393 U.S.

483, 501 (1969) (dissenting opinion of White, J.).

The Attorney General also suggests that the habeas

corpus forms provided by federal and state courts

are sufficient to enable the unassisted indigent

prisoner to present an adequate claim for relief. The

inadequacy of the forms for this purpose is discussed

in the Annual Report of the Judicial Council of Cali

fornia (1971) at pages 46-47. The Report points out

that the California form fails to give any guidance

as to what possible grounds and what facts are re

quired for relief, and notes that neither the relevant

facts nor the theories are self-evident, in any case.

Moreover, reliance on forms as. the exclusive means

of providing access to the courts assumes that

the existence of a valid claim for relief was not uncovered until

he was able to cite the governing case. In In re Greenfield, 11 Cal.

App.3d 536, 89 Cal.Rptr. 847 (1970), a case in which the peti

tioner’s right to relief turned on the same point of law, the court

observed that, “ No profession depends upon its boobs so deeply and

vitally as the law. Only the smallest lawyer ist too big to use law

books.” The need for including legal citations in prisoners’ peti-

titions is particularly acute because the judges of the rural Su

perior Courts in which most petitions are filed do not have the

assistance of law clerks. See Krause, A Lawyer Looks at Writ

Writing, 56 Cal. L. Rev. 371, 372 (1968).

25

prisoners will understand printed documents and in

structions well enough to fill them out correctly. The

invalidity of such an assumption is noted by the

Report, and the general illiteracy, lack of education

and intelligence in prisons have been noticed by this

Court, Johnson v. Avery, 393 U.S. 483, 487 (1969),

and documented by commentators. See Jacob and

Sharma, Justice After Trial: Prisoners’ Need for

Legal Services in the Criminal-Correctional Process,

18 KamL.Rev. 493, 508 (1970). In short, the un

tutored and indigent prisoner, even the literate and

intelligent one, without access to an adequate library

or preliminary legal counselling, is not likely to be

able to present a petition clearly setting forth a

meritorious claim.

3. The Legal Resources Provided by the State

As noted above,18 California does not authorize its

public defenders to assist in the preparation of post

conviction proceedings. Nor does the State provide

for court-appointed attorneys, bar associations or law

students to furnish any pre-hearing assistance. Cali

fornia does permit jailhouse lawyers to help other

prisoners. And the State does provide the few law

books listed in the regulation (App. 41) invalidated

by the court below. Rut that is all.

The Attorney General, instead of filing new regula

tions providing at least for an augmented library or

“ some new method” of meeting the legal needs of

California prisoners (App. 104-05), has appealed to

18See pp. 10-11, supra.

26

this Court, taking the position that the State is not

obligated to provide any legal assistance at all to

indigent prisoners. As stated above, we believe this

Court’s decisions on effective access to the courts

render the Attorney Greneral’s position completely

untenable.

There are easily available, relatively inexpensive

techniques for providing prisoners with the necessary

legal advice and assistance for presenting valid

claims. As this Court noted in Johnson v. Avery, 393

U.S. 483 (1969), some states make public defenders

available to consult with prisoners regarding their

habeas petitions. Others have created new post-con

viction procedures which permit or require the

appointment of private counsel.19 Still others have

developed programs to assist prisoners without the

expenditure of public funds, by cooperative action

with law schools or privately funded projects.20 See

generally, on the variety of prisoner legal aid pro

grams, Jacob and Sharma, Justice A fter Trial:

Prisoners’ Need for Legal Services in the <Criminal-

Correctional Process, 18 KanJLRev. 493, 593-613

(1970).

Courts and commentators have often discussed the

economy that can result from improved state post-

19See generally Note, State Post-Conviction Remedies and Fed

eral Habeas Corpus, 12 William & Mary L.Rev. 149 (1970).

20At least one state—New York—has obtained federal funds for

this purpose through a grant from the Law Enforcement Assist

ance Administration. See 5 Crim. L. Rptr. 2277-78 (1969). In

1971 alone, California received $32,999,000 of federal funds under

the Omnibus Crime Control Act. The Recorder, June 11, 1971,

at 1, col. 7. But such funds are apparently being devoted to other

purposes.

27

conviction procedures. By reducing frivolous and

repetitious petitions and eliminating the need for

piecemeal litigation, assistance programs could effect

a substantial saving in judicial time, and reduce the

burden on the state agency charged with the duty of

responding. See, e.g., United States v. Simpson, 436

F.2d 163 (D.C. Cir. 1970); Lay, Problems of Federal

Habeas Corpus Involving State Prisoners, 45 F.R.D.

45, 49-51 (1968).21

The benefits of such programs are not merely spec

ulative. Thus, the volume of state prisoner habeas

petitions filed in the federal district court for Western

Missouri decreased following a great improvement in

the state’s processing of post-conviction applications.

See Oliver, Postconviction Applications Viewed' by

a Federal Judge—Revisited> 45 F.R.D. 199, 204

(1968).22

When prisoners are forced to prepare their post

conviction petitions without any form of expert as

21As one commentator has observed, it is unfair to blame pris

oner litigants for the great volume of totally unmeritorious peti

tions filed while simultaneously denying them the assistance they

need to determine whether their petitions have merit or not.

Krause, A Lawyer Looks at Writ Writing, 56 Cal. L.Rev. 371, 372

(1968).

22The outstanding features of the revised Missouri procedure

are: (1) it provides for mandatory appointment of counsel if the

petitioner’s motion presents any question of law or issue of fact

(regardless of whether a hearing is required); (2) counsel is re-

quired to seek out any unalleged grounds for attack and amend

the complaint to include them; and (3) the trial court is required

to make findings of fact and conclusions of law on all issues pre

sented, whether or not a hearing is held. 45 F.R.D. at 211-13; Mo.

Sup.Ct.R. 27.26(h) (i). In Illinois, post-conviction procedures re

quire the public defender to consult with the prisoner, ascertain

his claims, examine the record and amend his petition adequately

to present any constitutional claims. See People v. Lyons, 46 111.2d

172, 263 N.E.2d 95 (1970).

sistance, the flood of meritless eases makes it likely

that meritorious cases will be overlooked. See Peters

v. Rutledge, 397 F.2d 731, 738 (5th Cir. 1968). Yet,

where prisoners receive proper assistance that dis

courages frivolous claims and effectively presents

meritorious ones, observers have been surprised by

the number of valid claims which emerge. See Oliver,

Postconviction Applications Viewed by a Federal

Judge-—Revisited, 45 F.R.D. 199, 217 (1968); Jacob

and Sharma, Justice After Trial: Prisoners’ Need for

Legal Services in the GriminaLCorrectional Process,

18 Kan.L.Rev. 493, 504 (1970).

In short, there are many techniques for providing

the necessary legal resources to make effective use of

existing post-conviction remedies. The Court need not

choose among them. The district court has required

the State officials themselves to develop appropriate

legal assistance methods, and they should be free to

experiment with whatever alternatives or combina

tions thereof are best suited to the California situa

tion. But clearly, we submit, the district court was

correct in finding that due process of law requires

some form of state-provided assistance to California

prisoners.

III. CALIFORNIA’S DENIAL OF NECESSARY LEGAL ASSIST

ANCE TO INDIGENT PRISONERS DEPRIVES THEM OF

EQUAL PROTECTION OF THE LAWS.

The district court foimd not only that California

denied indigent prisoners due process of law by

depriving them of effective access to the courts, but

29

also that they were denied equal protection when com

pared with those convicts who are able to afford

retained counsel.

This Court has consistently made plain that access

to the courts by indigent prisoners for both appeals

and post-conviction proceedings cannot be effectively

denied by economic and other barriers. See Griffin v.

Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956) (right to free transcript

for appeal) ;2'8 Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353

(1963) (right to assigned counsel on appeal) r 1 Lane

v. Brown, 372 U.S. 477 (1963) (indigent may not be

barred from appealing denial of state coram nobis by

requirement that public defender order transcript) ;

Burns v. Ohio, 360 U.S. 252 (1959) (right to seek

leave to appeal without paying filing fee) ;2B Smith v.

Bennett, 365 U.S. 708 (1961) (right to bring State * 24 25

23“ There can be no equal justice where the kind of trial a man

gets depends on the amount of money he has. Destitute defendants

must be afforded as adequate appellate review as defendants who

have money enough to buy transcripts.” 351 U.S. at 19 (Black,

J.). “ The State is not free to produce such a squalid discrimina

tion. I f it has a general policy of allowing criminal appeals, it

cannot make lack of means an effective bar to the exercise of this

opportunity. The State cannot keep the word of promise to the

ear of those illegally convicted and break it to their hope.” Id. at

24 (Frankfurter, J., concurring).

24“ There is lacking that equality demanded by the Fourteenth

Amendment where the rich man, who appeals as of right, enjoys

the benefit of counsel’s examination into the record, research of

the law, and marshalling of arguments on his behalf, while the

indigent, already burdened by a preliminary determination that

his case is without merit, is forced to shift for himself. The in

digent, where the record is unclear or the errors are hidden, has

only the right to a meaningless ritual, while the rich man has a

meaningful appeal.” 372 U.S. at 357-58 (Douglas, J.).

25“ [0]nce the State chooses to establish appellate review in

criminal cases, it may not foreclose indigents from, access to any

phase of that procedure because of their poverty.” 360 U.S. at 257

(Warren, C. J.).

30

habeas corpus proceedings without paying fees) f 6

Long v. District Court, 385 U.S. 192 (1966) (right to

free transcript on appeal from State habeas corpus);

Draper v. Washington, 372 U.S. 187 (1963) (evalu

ation of merits by trial judge cannot bar the full

appellate review available to non-indigents) ; Roberts

v. LaVallee, 389 U.S. 40 (1967) (right to free tran

script of preliminary hearing) ;26 27 Rinaldi v. Yeager,

384 U.S. 305 (1966) (state may not withhold

prisoner’s earnings to recoup cost of transcript fur

nished on appeal) ; Anders v. California, 386 U.S. 738

(1967) (right to assistance of appointed counsel act

ing as advocate) ;28 Entsminger v. Iowa, 386 U.S. 748

(1967) (right to full record on appeal assuring com

plete and effective appellate review) ; Gardner v. Cali

fornia, 393 U.S. 367 (1969) (right to transcript of

state habeas hearing); Williams v. Oklahoma City,

395 U.S. 458 (1969) (right to free transcript for

appeal from conviction of petty offense).

Of course, this does not mean that the state must

equalize litigation resources to place all potential

claimants on the same footing. But unless the indi

26“ [T]o interpose any financial consideration between an in

digent prisoner of the State and his exercise of a state right to

sue for his liberty is to deny that prisoner the equal protection of

the laws.” 365 U.S. at 709 (Clark, J.).

27“ Our decisions for more than a decade now have made clear

that differences in access to the instruments needed to vindicate

legal rights, when based upon the financial situation of the defend

ant, are repugnant to the Constitution.” 389 U.S. at 42 (per

curiam).

28The procedure directed by the Court “ will assure penniless

defendants the same rights and opportunities on appeal— as nearly

as is practicable—as are enjoyed by those who are in a similar

situation but who are able to afford the retention of private coun

sel.” 386 U.S. at 745 (Clark, J.).

31

gent prisoner has legal assistance “ reasonably ade

quate for the task” of presenting a valid post-convic

tion claim, he will be “ surely and effectively barred

from the courts,” Johnson v. Avery, 393 II.S. 483, 499

(1969) (dissenting opinion of White, J.), and the

remedy fully available to a prisoner with some money

will be denied to the indigent.29 30 Such denial of legal

assistance minimally necessary to present a valid

claim violates the equal protection clause.80

The Attorney General contends that the concept of

the “ affluent” convict is illusory, and thereby dis

misses the district court's equal protection holding.

But clearly there are some prisoners who can pay a

retained attorney to counsel them, do their research

and draft their petition. As long as there are any

in this status, we submit, the State cannot—by im

prisoning the others and assuring their continued

impoverishment—make legal cripples of the indigent

prisoners.

Furthermore, California prisoners are disadvan

taged not only vis-a-vis their more fortunate fellows

but also when compared to the many convicted felons

given probation or on parole, who are free to earn

enough money to pay a lawyer or consult an OEO

legal services attorney or, if they choose, do their own

research at available public libraries. Therefore, this

case is much like the Court’s decision in Rinaldi v.

2®Of course, there is no rational basis for assuming that in

digents’ claims will be less meritorious than those of other pris

oners. Cf. Burns v. Ohio, 360 U.S. 252, 257 (1959).

30See generally, Michelman, On Protecting the Poor Through

the Fourteenth Amendment, 83 Harv. L. Rev. 7, 25-26 (1969).

Yeager, 384 U.S. 305 (1966). In Rinaldi, the Court

invalidated a Hew Jersey practice of withholding

prisoners’ earnings to reimburse the state for tran

scripts previously provided. The Court pointed out

that others convicted of the same crimes—but placed

on probation, given a suspended sentence or a fine—

were not subject to the same treatment. The Court

held that the New Jersey procedure thus denied

prisoners equal protection of the laws.

IV. THE ELEVENTH AMENDMENT DOES NOT BAR THE

RELIEF ORDERED BY THE DISTRICT COURT.

The Attorney General asserts that the injunction

of the court below is inconsistent with the Eleventh

Amendment because it is, in effect, a “ raid on the

state treasury.” This argument is a red herring.31

The district court’s injunction does not require the

spending of a single dollar of state money. What it

requires is that the defendant officials submit revised

regulations providing for some plan of adequate legal

assistance to prisoners. The Attorney General has not

submitted any plan, but has instead appealed to this

Court.

31The Attorney General also urges that, the relief granted goes

beyond the stipulation of the parties. This point hardly seems

worthy of presenting to this Court. Rule 54(e) of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure states that the judgment “ shall grant the

relief to which the party in whose favor it is rendered is entitled,”

even if not demanded in the pleadings. The court should be free

to fashion an appropriate remedy that is not expressly excluded by

or plainly inconsistent with the stipulation. The state officials will

have ample opportunity to be heard on the question of relief when

new regulations are filed in the district court.

33

W e assume that regulations complying with the

district court’s order would likely result in the ex

penditure of additional state funds, although this is

not necessarily so.32 However, the same is true in

practically any case enforcing Fourteenth Amend

ment obligations. A recent example is the decision in

Swann v. Charlotte-Meckleriburg Board of Educa

tion, 401 U.S........ , 91 S.Ct. 1267 (1971), where the

Court approved a district court order requiring a

substantial increase in the amount of busing required

to meet constitutional standards of school integration.

The Court noted that the school system would have

to employ 138 more buses than it had previously

operated. Id. at 1283, n.12. There are numerous other

cases, involving a range of Fourteenth Amendment

issues, where the Court has indirectly required the

states to expend public funds in order to bring public

programs into compliance with constitutional guar

antees. See, e.g., Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254

(1970) (hearings for welfare recipients) ; Turner v.

Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970) (reconstitution of jury

lists) ; Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) (re-

apportionment of legislative districts).

The Attorney General acknowledges that this Court

has effectively ordered the disbursement of state

funds in a number of cases (brief for appellants, p.

35). Most closely in point are the decisions in Griffin

v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956), and Douglas v. Cali

fornia, 372 U.S. 353 (1963), where the Court in

32See page 26, supra, describing alternatives for providing

minimal preliminary legal assistance to prisoners from private or

federal sources not requiring the expenditure of state funds.

34

effect required the states to spend money in order to

comply with constitutional guarantees in the criminal

process. The Attorney General purports to distinguish

these cases, however, on the ground that “ this was

done on direct review of criminal convictions in state

courts.” This distinction is untenable. We cannot be

lieve that the results in Griffin and Douglas or any

other case where this Court has granted relief result

ing in the expenditure of state funds would be any

different if the case had been brought (like the

present case) as an affirmative civil suit to invalidate

a state statute or regulation on constitutional grounds.

The Eleventh Amendment does not stand in the way

of enforcing the Fourteenth.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated, the decision below should

be in all respects affirmed.

Dated, June 17, 1971.

Respectfully submitted,

J a c k G reenberg

J a m e s M . N a b r it , I II

C h a r le s St e p h e n R alston

S t a n l e y A . B ass

A n t h o n y G . A m sterd am

W il l ia m B e n n e t t T u rn er

O scar W il l ia m s

A lice D a n ie l

Attorneys for Amici Curiae,