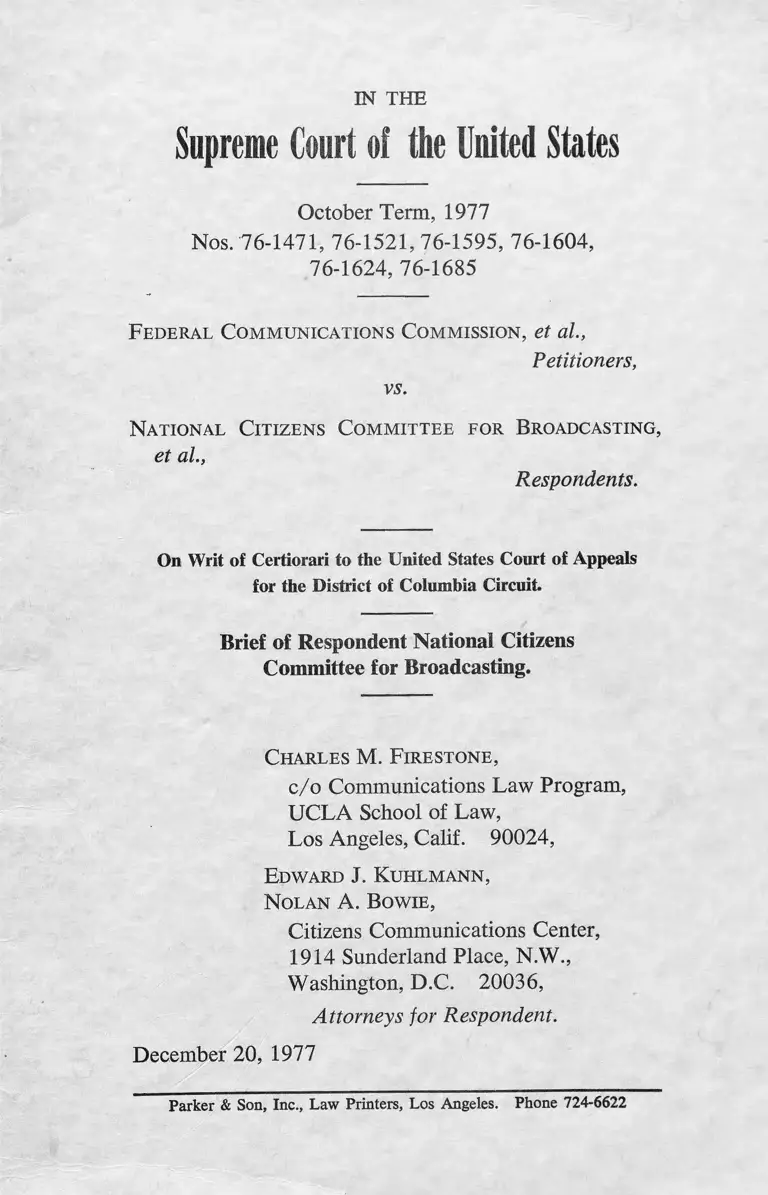

Federal Communications Commission v. National Citizens Committee for Broadcasting Brief of Respondent

Public Court Documents

December 20, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Federal Communications Commission v. National Citizens Committee for Broadcasting Brief of Respondent, 1977. 8ea22784-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4bd23e2d-954f-4c69-a316-6b294597e434/federal-communications-commission-v-national-citizens-committee-for-broadcasting-brief-of-respondent. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1977

Nos. 76-1471, 76-1521,76-1595, 76-1604,

76-1624, 76-1685

F ederal C om m unications Com m ission , et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

N ational C itizen s Co m m ittee for Broadcasting,

et al.,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the District of Columbia Circuit.

Brief of Respondent National Citizens

Committee for Broadcasting.

Charles M. F iresto n e ,

c/o Communications Law Program,

UCLA School of Law,

Los Angeles, Calif. 90024,

E dward J. Ku h lm a n n ,

N olan A. Bow ie ,

Citizens Communications Center,

1914 Sunderland Place, N.W.,

Washington, D.C. 20036,

Attorneys for Respondent.

December 20, 1977

Parker & Son, Inc., Law Printers, Los Angeles. Phone 724-6622

vSUBJECT I N D E X

Opinions Below ..-....... .................... .................. -....... 1

Jurisdiction ..................... ........ .................................. 2

Statutes Involved .......... .................. — ...... ............. - 2

Questions Presented__ ______ ______ ____-....... . 2

Counterstatement of the C ase................................... 3

A. The FCC’s Long-Standing Emphasis on Di

versification of Ownership of the Media of

Mass Communication ....... 3

B. The 1970 Proceeding, Docket 18110 ............ 6

1. The Further Notice of Proposed Rule-

making .................................................... 6

2. The Second Report and Order ............ 8

3. Reconsideration ........ 10

C. The Court of Appeals Decision ..................... 10

Summary of Argument ..... ............ ........................... 13

Argument ............. 16

I.

The Court of Appeals Properly Upheld the Com

mission’s Authority to Adopt a Rule Barring

Future Acquisitions of Newspaper-Broadcast

Combinations ............ ............. .................... — 16

A. Congress Has Given the Commission the

Latitude and Authority to Consider News

paper Ownership in Licensing Broadcast

Stations ................. 16

Page

11.

B. The First Amendment Is Served Rather

Than Abridged by a Content Neutral

Page

Rule Promoting Diversity of Information

Sources to a Local Community................ 21

C. The Commission’s Adoption of Its Pro

spective Ban Is a Reasonable Exercise of

Its Discretion .......................... ................ 23

II.

The Court of Appeals Correctly Found the Com

mission’s Second Report Arbitrary in the Ap

plication of Its New Cross-Ownership Stand

ards to Existing Combinations ........ 26

A. The Commission Erred in Its Assessment

of the Burden of Proof in This Proceeding

.................................................................... 27

B. The Commission Did Not Adequately Ex

plain Why Its Diversification Presumption

in the Prospective Rules Was Denigrated

When Applied to Most Existing Combina

tions ............................................................ 29

C. The Commission’s Grounds for Preferring

Grandfathering Interests of Existing Li

censees Over the Public’s Interest in Diver

sity Are Arbitrary and Unsupported by

the Record ------ -------- ---------------------- 32

1. Local Ownership and Integration of

Ownership and Management______ 32

2. Continuity of Operation ........... 33

3. Economic Dislocation ___ 37

4. Unfairness to Existing Licensees .... 39

111.

Page

a. Divestiture Is Not Retroactive

Rulemaking ............... 39

b. Divestiture Is Not Severe or

Harsh ....... 42

5. Best Practicable Service ................... 44

III.

The Commission’s Standards for Divestiture and

for Ad Hoc Challenge Are Irrational .............. 45

A. The Standard for Divestiture ----------- - 46

B. The Ad Hoc Standard ................. ....... ...... 48

IV.

A Reviewing Court May Instruct an Agency on

Remand Where Fairness and the Public In

terest so Dictate.... .............- ........................... 53

Conclusion .................. .................................. ......— 57

Appendix. 26 U.S.C. § 1071 (a) (1970) ....App, p. 1

IV.

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED

Cases Page

Addison v. Holly Hill Co., 322 U.S. 607 (1944)

.... ................. ............. ..................... .................. 55, 56

Alianza Federal de Mercedes v. FCC, 539 F.2d 732

(D.C. Cir. 1976) _____ _________ __________ 38

American Airlines, Inc. v. CAB, 359 F.2d 624

(D.C.Cir. 1966) (en banc) ............................ 40, 41

Ashbacker Radio Co. v. FCC, 326 U.S. 327 (1945)

..... ............ 40

Associated Press v. United States, 52 F.Supp. 362

(S.D.N.Y. 1943), aff’d 326 U.S. 1 (1945)

................... ......... ................ ................... .....3, 22, 28

Bilingual Bicultural Coalition on Mass Media v.

FCC, 492 F,2d 656 (D.C. Cir. 1974) ................ 27

Buckley v. Caleo, 424 U.S. 1 (1976) ....... 21, 22, 24

California Citizens Band Ass’n v. United States, 375

F.2d 43 (9th Cir.), cert denied, 389 U.S. 844

(1967) ........................ 40

CBS v. Democratic National Committee, 412 U.S.

94 (1973) ............ 3

Citizens Communications Center v. FCC, 447 F.2d

1201 (D.C. Cir. 1971) ............. ........... ....3, 24, 40

Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe, 401

U.S. 402 (1971) ________ 24

Crowder v. FCC, 399 F.2d 569 (D.C. Cir. 1968) .. 36

Clarksburg Publishing Co. v. FCC, 225 F.2d 511

(D.C. Cir. 1955) ............ .................. ................ 3

Columbus Broadcasting Coalition v. FCC, 505 F.2d

320 (D.C. Cir. 1974) ................ ......... .......7, 8, 28

V.

F.C.C. v. Pottsville Broadcasting Co., 309 U.S. 134

(1940) .............................................................. 16, 40

FCC v. RCA Communications, Inc., 346 U.S. 86

(1953) .............................. .................................... 24

FCC v. Sanders Bros. Radio Station, 309 U.S. 470

(1940) .................................................................. 40

Fed. Radio Comm’n v. Nelson Bros., 289 U.S. 266

(1933) .................................................................. 40

FPC v. Texaco, 377 U.S. 33 (1964) .................... . 40

General Telephone Co. of the Southwest v. United

States, 449 F.2d 846 (5th Cir. 1971) ..... ..3, 5, 54

Greater Boston Television Corp. v. FCC, 444 F.2d

841 (DC. Cir. 1970), cert, denied 403 U.S. 923

(1971) .............................................. -.............. -6, 18

Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U.S. 233

(1936) ............................ ............................... -..... 22

GTE Service Corp. v. FCC, 474 F.2d 724 (2d Cir.

1973) ..................................... 17, 24

Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347 (1914) ....... 53

Hale v. FCC, 425 F.2d 556 (D.C. Cir. 1970) ....

............................ ......... ................................7, 27, 34

Iacopi v. FCC, 451 F.2d 1142 (9th Cir. 1971) .... 5

Joseph v. FCC, 404 F.2d 207 (D.C. Cir. 1968) ....

........................................................................... 18, 57

Mansfield Journal Co. v. FCC, 180 F.2d 28 (D.C.

Cir. 1950) ..... .............. ................. -................ 18, 23

McClatchy Broadcasting Co. v. FCC, 239 F.2d 15

(D.C. Cir. 1956), cert, denied, 353 U.S. 918

(1957) .................................................................. 18

Page

VI.

Metropolitan Television Corp. v. FCC, 289 F.2d

874 (D.C. Cir. 1961) ______________ ____ 5, 54

Miami Herald v. Tornillo, 418 U.S. 241 (1974) .. 22

Mobil Oil Corp. v. FPC, 417 U.S. 283 (1974) ........ 24

Mt. Mansfield Television, Inc. v. FCC, 422 F.2d

470 (2d Cir. 1971) ............................................... 24

National Ass’n of Broadcasters v. FCC, 554 F.2d

1118 (D.C. Cir. 1976) ....... ........ ............54, 55, 56

National Black Media Coalition v. FCC, D.C. Cir.

No. 77-1500 .......... ................. ................... .......... 44

National Citizens Committee for Broadcasting v.

FCC, D.C. Cir. No. 75-1933 (Sept. 22, 1975) .... 5

National Cable Television Ass’n v. United States,

415 U.S. 336 (1974) ..................... 54

NBC v. United States, 319 U.S. 219 (1943) ..... 16, 21

New Orleans v. Dukes, 427 U.S. 297 (1974) .......... 54

Office of Communication of the United Church of

Christ v. FCC, 359 F.2d 994 (D.C. Cir.

1966) ........ 44

Office of Communication of the United Church of

Christ v. FCC, 425 F.2d 543 (D.C. Cir. 1969)

................................................................................. 56

Page

Office of Communication of the United Church of

Christ v. FCC, 465 F.2d 519 (D.C. Cir. 1972).. 23

Palko v. Connecticut. 302 U.S. 319 (1937) ............ 29

Permian Basin Area Rate Cases, 390 U.S. 747

(1969) ___ _____ ____ ______ _________ 18

Pikes Peak Broadcasting v. FCC, 422 F.2d

671 (D.C. Cir. 1969) ..................... ..................... 53

Vll.

Plains Radio Broadcasting Co. v. FCC, 175 F.2d

359 (D.C. Cir. 1949) ....................... ................. 18

Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. FCC, 395 U.S. 367

(1969) ............................ ........... .........3, 21, 24, 28

Scripps-Howard Radio, Inc. v. FCC, 189 F.2d 677

(D.C. Cir.), cert, denied 342 U.S. 830 (1951)

......................................... 3

SEC v. Chenery Corp., 332 U.S. 194 (1947) .......... 56

Secretary of Agriculture v. United States, 347 U.S.

645 (1954) .................................................. . 57

South Terminal Corp. v. EPA, 504 F.2d 646 (1st

Cir. 1974) .... ................ ......... .................. ......41, 54

Stone v. FCC, 466 F.2d 316 (D.C. Cir. 1972) ........ 7

Transcontinent Television Corp. v. FCC, 308 F.2d

339 (D.C. Cir. 1962) .......................................... 41

United States v. E. I. DuPont de Nemours & Co.,

351 U.S. 377 (1956) .......... ........... ...................... 47

United States v. E. I. DuPont de Nemours & Co.,

366 U.S. 316 (1961) _________________ _____ 43

United States v. Maher, 307 U.S. 148 (1939) ....... 53

United States v. Midwest Video Corp., 406 U.S.

649 (1972) .......................................... 17

United States v. Radio Corp. of America, 358 U.S.

334 (1959) ........................................... 17

United States v. Southwestern Cable Co., 392 U.S.

157 (1968) .............................. ................ 17, 18, 24

United States v. Storer Broadcasting Co., 351 U.S.

192 (1956) .................... ............ ......3, 4, 16, 40, 50

United States v. Wise, 370 U.S. 405 (1961) ....... 19

Page

vm.

WAIT Radio v. FCC, 418 F.2d 1153 (D.C. Cir.

1969) .................... ................................................ 50

WBEN, Inc. v. United States, 396 F.2d 601 (2d Cir.

1968) ...... ............. ............................................40, 42

Williams v. Washington Metropolitan Area Transit

Commission, 415 F.2d 922 (D.C. Cir. 1968)

(en banc), cert, denied, 393 U.S. 1081 (1969) .. 56

WLVA, Inc. v. FCC, 459 F.2d 1286 (D.C. Cir.

Page

1972) ..............................-..................................... 35

Agency Decisions and Orders

A. H. Belo Corp., 46 F.C.C.2d 1075 (1974) .......... 28

Amendment of Multiple Ownership Rules, 9 P&F

Radio Reg. 1563 (1953) ..................................... 4

Amendment of the Multiple Ownership Rules, 18

Fed. Reg. 7796 (1953) ................... ................... 4

American Television Co., 12 F.C.C.2d 518 (1968)

............................................................................... 49

Cable Television Systems, Second Report and Order,

55 F.C.C.2d 540 (1975) ..................... ........-...... 5

CATV Rules, 2 F.C.C.2d 725 (1966) .................... 43

CATV Rules, 36 F.C.C.2d 143 (1972) ............ 43

CATV, Second Report and Order, 23 F.C.C.2d

816 (1970) ....... .......................-.....- .....-..........- 5

Chronicle Broadcasting Co., 16 F.C.C.2d 882

(1969), renewal granted 40 F.C.C.2d 775

(1973) ........... ............. -.......... - .--8 , 23, 27, 47, 49

City of Camden, 18 F.C.C.2d 412 (1969) .......... -- 37

Daily Telegraph Printing Co., 59 F.C.C.2d 185

(1976) ....... .............. - .............. - .......... -............. 27

IX.

Duopoly Rules, 5 Fed. Reg. 2382 (1940) ............. 4

Duopoly Rules, 6 Fed. Reg. 2282 (1941) ............. 4

Duopoly Rules, 8 Fed. Reg. 16065 (1943) .... 4

Effingham Broadcasting Co.. 51 F.C.C.2d 453

(1975) ........ ..................................... ........... ......... 52

Federation of Citizens Ass’ns (D.C.), 21 F.C.C.2d

12 (1969) ........ ............................... ................... 7

Frontier Broadcasting Co., 21 F.C.C.2d 570

(1970), dismissed for voluntary divestiture, 35

F.C.C.2d 875 (1972) .......... ............6, 18, 49, 52

Gale Broadcasting Co., 15 P.&F, Radio Reg. 2d 337

(1969) .................. - _______ _______________ 49

Jonquil Broadcasting Co., 21 F.C.C.2d 178 (1970)

................................... .............................. ............. 49

Lee Enterprises, Inc., 18 F.C.C.2d 684 (1969) ..... 49

McClatchy Newspapers, 40 P&F Radio Reg. 2d

1393 (1977) .... ................... .............. ................ 28

McPherson Broadcasting Co., 54 F.C.C.2d 565

(1975) ................ ....................... ............... 27, 28, 51

Miami Broadcasting Co., 1 P.&F. Radio Reg. 2d 43

(1963) ........ .................... - .....-.......................... - 49

Midwest Radio-Television, Inc., 16 F.C.C.2d 943,

18 F.C.C.2d 1011 (1969), renewal granted 24

F.C.C.2d 625 (1970) ____ ___ 6, 8, 18, 19, 27, 49

Multiple Ownership. First Report and Order,

Docket 18110, 22 F.C.C. 2d 306 (1970) ..6, 24, 25

Multiple Ownership, Further Notice, 22 F.C.C.2d

339 (1970) ..................... ........................-.......-6, 7

Page

X.

Multiple Ownership, Notice, 33 Fed. Reg. 5315

(1968) _____________ __ _________ ___ ____ 6

National Citizens Committee for Broadcasting, 56

F.C.C.2d 476 (1975), 57 F.C.C.2d 1060 (1976)

..................................................................... 28

Newhouse Broadcasting Corp. (WAPI-TV), 59

F.C.C.2d 218 (1976) ........................ ............ 27, 51

Newspaper Ownership of Radio Stations, 9 Fed.

Reg. 702 (1944) .......... ...............- ....... .............. 5

Policies Relating to the Broadcast Renewal Appli

cant, Stemming from the Comparative Hearing

Process, 40 P. & F. Radio Reg. 2d 763 (1977),

appeal pending sub nom. National Black Media

Page

Coalition v. FCC, D.C. Cir. No. 77-1500 .......... 44

Policy Statement on Comparative Broadcast Hear

ings, 1 F.C.C.2d 393 (1965) ................... .......4, 32

Policy Statement on Comparative Hearings Involv

ing Regular Renewal Applicants, 22 F.C.C.2d

424, recon. denied, 24 F.C.C.2d 383 (1970),

rev’d sub nom., Citizens Communications Center

v. FCC, 447 F.2d 1201 (D.C. Cir. 1971) ___ 44

Public Notice, FCC 76-1197, December 23, 1976 .. 43

RadiOhio, Inc., 38 F.C.C.2d 721 (1975), aff’d sub

nom. Columbus Broadcasting Coalition v. FCC,

505 F,2d 320 (D.C. Cir. 1974) ...... ............ . 28

Report on Chain Broadcasting, Docket 5060, May

1941, affirmed, National Broadcasting Corp. v.

United States, 319 IJ.S. 190 (1943) ------ ------4, 16

Scripps-Howard Broadcasting Company, 31 F.C.C.

2d 1090 (1971) ....................... - .................... 7, 18

XI.

Page

Tax Certificates, 19 P&F Radio Reg. 2d 1831

(1970) .............................. ............. ...................... 31

Tax Certification Policy, 59 F.C.C.2d 91 (1976)

............................................................................... 47

Terre Haute Broadcasting Corp., 25 F.C.C.2d 348

(1970) ......................... ............ ............... ............ 44

Western Connecticut Broadcasting Co., 47 F.C.C.2d

432 (1974) ............................................................ 27

WPIX, Inc., 20 F.C.C.2d 298 (1970) ................. 27

WGAL-Television, Inc., 62 F.C.C.2d 527 (1976)

..........................................................9, 27, 50, 51, 52

WHDH, Inc., 16 F.C.C.2d 1 (1969), aff’d sub nom.

Greater Boston Television Corp. v. FCC, 444 F.

2d 841 (D.C. Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 403 U.S.

923 (1971) ....................... ,...............................6, 27

Statutes

Communications Act of 1934, 48 Stat. 1064, as

amended:

Section 2(a), 47 U.S.C. §152(a) (1970) ....... . 2

Section 4, 47 U.S.C. §154 (1970) ...................... 2

Section 301, 47 U.S.C. §301 (1970) .... ...2, 40, 54

Section 303, 47 U.S.C. §303 (1970) ........... ....2, 16

Section 304, 47 U.S.C. §304 (1970) .............40, 54

Section 307, 47 U.S.C. §307 (1970) ........2, 40, 54

Section 309, 47 U.S.C. §309 (1970)....2, 29, 40, 54

Section 405, 47 U.S.C. §405 ................ ......... . 23

Interna] Revenue Code, 26 U.S.C. Sec. 1071

(1970) ........ ....................... -............... 2, 5, 9, 38, 42

XU.

Revenue Act of 1943, Sec. 123, 58 Stat. 44 (Feb.

Page

25, 1944), 26 U.S.C. Sec. 112(m) .................... 5

United States Code, Title 28, Sec. 1254(1) ............ 2

United States Constitution, Amendment I ............

...................................13, 21, 22, 23, 28, 29, 49, 53

United States Constitution, Amendment X IV .......... 54

United States Constitution, Amendment XV .......... 53

Rules and Regulations of the

Federal Communications Commission:

Code of Federal Regulations, Title 47, Sec.

1.597(a) (1976) ........ ......... ......... ..................... 36

Code of Federal Regulations, Title 47, Sec. 73.35

(1976) ......................... ......... .......................3, 48, 49

Code of Federal Regulations, Title 47, Sec. 73.240

(1976) ..................... .......-............................3, 48, 49

Code of Federal Regulations, Title 47, Sec. 73.636

(1976) ......................................................... 3, 48, 49

Code of Federal Regulations, Title 47, Sec. 76.501

(1975) ................... ............... ............................... 5

Miscellaneous

Barnett, S., “Cross-Ownership of Mass Media in the

Same City.” (Barnett Report) .... .................. .23, 28

Congressional Quarterly Almanac (Vol. XXX), pp.

714-17 (1974) ..... ....................... -........ ..........20

Davis, K., Administrative Law of the Seventies,

(1976) __________ ___________• ---------- 41

Federal Communications Commission Annual Re

ports, 1945 ------------ -------------------- — .......4, 5

Xlll.

Federal Communications Commission Annual Re

ports, 1969-1973 .................................................... 34

Friendly, H., Chenery Revisited: Reflections on Re

versal and Remand of Administrative Orders,

1969 DUKE L J. 199, 223 (1969) ..................... 57

Gormley, W. T., Jr., The Effects of Newspaper-

Television Cross-Ownership on News Homoge

neity, (Univ. of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

(1976)) ................................................................ 33

Green, “Conglomerate Broadcasters Are Faulted in

FCC Pilot Study, Wider Inquiry Slated,” Wall

Street Journal, August 11, 1970, p. 32 ................ 28

H. Rep. No. 93-961, 93d Cong., 2d Sess............ 8, 20

H. Rep. No. 1079, 78th Cong., 2d Sess. (1944) .. 5

H.R. 12993, 93d Cong., 2d Sess., (March 28,

1974) .................................................................... 8

Howard, H., Multiple Broadcast Ownership: Regu

latory History, 27 FED. COM. B.J. 1, 15 (1974)

................................................................................. 4

Johnson & Dystel, A Day In The Life: The Federal

Communications Commission, 82 YALE L. J.

1575, 1607 (1973) ............................................... 28

Koch, E., “WCVB: Carrying the Torch,” 29 Access

Magazine 13 (1976) .............................................. 36

Moore, B. J., Federal Practice (1974) ..... .............. 55

“NAB Presses Drive for Renewal Relief,” Broadcast

ing Magazine, December 4, 1972, p. 38 ............ 19

Senate Report No. 93-1190, 93d Cong., 2d Sess.,

.................................... .................. .................................................... . .8, 20

Page

XIV.

“Two More Cross-Owners Go Thataway,” Broad

casting Magazine, December 12, 1977, p. 1 9 ..... 31

U.S. News and World Report, April 18, 1977, p.

36 ........................................................................... 30

“Whitehead Bill Joins the Crowd Seeking to Ease

Renewal Trauma,” Broadcasting Magazine, Janu

ary 1, 1973, pp. 24-25 ......................................... 19

“WMAL-TV Fetches $100 Million, Trading Rec

ord,” Broadcasting Magazine, April 4, 1977, p.

28 .......................................................................31, 43

Page

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1977

Nos. 76-1471, 76-1521, 76-1595, 76-1604,

76-1624, 76-1685

F ederal C om m unications Com m ission , et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

N ational C itizens Co m m ittee for Broadcasting,

et al.,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the District of Columbia Circuit.

Brief of Respondent National Citizens

Committee for Broadcasting.

OPINIONS BELOW.

The opinions of the Court of Appeals are reported

at 555 F.2d 938 (D.C. Cir. 1977) (A. 339-444).1

The opinions of the Federal Communications Commis

sion (FCC) are reported at 50 F.C.C.2d 1046,2

reconsideration, 53 F.C.C.2d 589 (1975) (A. 134-

338).

1Natioml Citizens Committee for Broadcasting v. FCC (here

after, NCCB).

2Second Report and Order, Multiple Ownership (hereafter

Second Report).

— 2—

JURISDICTION.

This Court has jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. §1254

(1), the Court having granted and consolidated the

various petitions for a writ of certiorari in this review

on October 3, 1977.

STATUTES INVOLVED.

Sections 2(a), 4(i), 4 (j), 301, 303(g), 303(r),

307(a), 307(d), 309(a) and 309(d) of the Communi

cations Act of 1934, 48 Stat. 1064, as amended, 47

U.S.C. §§152(a), 154(i), 154(j), 301, 303(g),

303(r), 307(a), 307(d), 309(a) and 309(d) (1970)

are set forth in the Appendix. (A. 27-32).

In addition, Respondent sets forth Section 1071 of

the Internal Revenue Code, 26 U.S.C. §1071, in the

Appendix to this brief.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED.

Whether the Federal Communications Commission

has the authority to adopt a general rule proscribing

future licensing of broadcast stations to daily news

papers serving the same market.

Whether the Court of Appeals was correct in holding

that the Commission acted arbitrarily and capriciously

when it grandfathered most existing broadcast station-

newspaper combinations.

Whether the Court of Appeals correctly concluded

that the Commission acted arbitrarily in differentiating

among licensees in setting the standard for divestiture

of cross-owned media.

Whether the Court of Appeals acted reasonably when

it ordered the Commission to take further steps to

— 3—

ensure that everyone would be consistently treated under

the general standard against cross-ownership adopted

in the rulemaking proceeding.

COUNTERSTATEMENT OF THE CASE.

These cases present for review a decision of the

United States Court of Appeals for the District of

Columbia Circuit upholding that portion of the Federal

Communications Commission’s multiple ownership rules

(47 C.F.R. §§73.35, 73.240 and 73.636 (1976)) that

prohibit ownership between co-located broadcast sta

tions and newspapers, and vacating that part of the

rules which grandfathers all but 16 current licensees

that are associated with co-located newspapers. The

respondent, National Citizens Committee for Broadcast

ing, seeks affirmance.

A. The FCC’s Long-Standing Emphasis on Diversifi

cation of Ownership of the Media of Mass Com

munication.

The Federal Communications Commission, with the

guidance of this Court3 and the courts of appeals,4

has long recognized that in a licensing scheme where

access by the public is necessarily limited, diversification

of ownership of the media of mass communication

sE.g., United States v. Storer Broadcasting Co., 351 U.S.

192, 203-04 (1956); Associated Press v. United States, 326

U.S. 1, 20 (1945). See also CBS v. Democratic National

Committee, 412 U.S. 94, 122 (1973); Red Lion Broadcasting

Co. v. FCC, 395 U.S. 367, 390 (1969).

4E.g., General Telephone Co. of the Southwest v. United

States, 449 F.2d 846, 857 (5th Cir. 1971); Citizens Communi

cations Center v. FCC, 447 F.2d 1201, 1207, 1213-14, n.

36 (D.C. Cir. 1971); Clarksburg Publishing Co. v. FCC, 225

F.2d 511, 518-19 (D.C. Cir. 1955); Scripps-Howard Radio,

Inc. v. FCC, 189 F.2d 677, 683 (D.C. Cir.), cert, denied

342 U.S. 830 (1951).

-4-

is a strong, if not primary licensing factor.* 1 * * * 5 Thus

the Commission adopted rules (1) in 1941 requiring

NBC to divest one of its dual networks6; (2) in

1941-43 barring common ownership of two local broad

cast stations of the same type (e . g only one AM

radio license in a given market) and requiring divest

iture within six months to conform to the new “duopoly”

standard7; and (3) in 1953 specifying maximum num

bers of TV, AM and FM stations allowed to be under

common ownership nationally.8 * * * * * * 15

As early as 1944 the Commission considered news

paper ownership to be a relevant factor in awarding

licenses. Although it declined to adopt a rule generally

barring newspaper ownership of a local station, the

Commission stated its intention at that time not to

grant licenses “to permit concentration of control in

sE.g., Policy Statement on Comparative Broadcast Hearings,

1 F.C.C.2d 393, 394 (1965) (hereafter, 1965 Policy Statement).

See also cases cited in the Court’s decision below, NCCB,

555 F.2d at 948-49, nn. 26-27 (A. 336-68).

6Report on Chain Broadcasting, Docket 5060, May 1941,

affirmed, National Broadcasting Corp. v. United States, 319

U.S. 190 (1943).

7Duopoly Rules 5 Fed. Reg. 2382 (1940), 6 Fed. Reg.

2282 (1941), 8 Fed. Reg. 16065 (1943). See 1945 F.C.C.

Annual Report, at 12.

8Amendment of the Multiple Ownership Rules, 18 Fed.

Reg. 7796 (1953), affirmed United States v. Storer Broad

casting Co., 351 U.S. 192 (1956). Unlike the instant case,

almost all licensees met this standard at the time it was adopted.

Divestitures were thus considered on a case-by-base basis.

Amendment of Multiple Ownership Rules, 9 P&F Radio Reg.

1563, 1572 (1953). According to one commentator, only two

parties violated the new rule. They were each given three

years to divest their excess stations. FI. Howard, Multiple Broad

cast Ownership: Regulatory History, 27 FED. COM. B.J. 1,

15 (1974).

— 5—

the hands of the few to the exclusion of the many

who may be equally well qualified to render such

public service as is required of a licensee.”9

When adopting ownership diversification rules, the

Commission has regularly imposed divestiture remedies

to achieve its policies.19 Congress has not only specif

ically approved this practice but also fostered it. In

reaction to the Commission’s divestiture requirements

in its 1943 AM duopoly rules, supra, n. 7, Congress

amended the Internal Revenue Code in 1944 to au

thorize the FCC to grant special tax certificates. This

allowed licensees who sold or exchanged their media

properties, in order to effectuate a change in a Commis

sion ownership policy, to defer capital gains by treating

the transactions as involuntary conversions.11 9 10 *

9Newspaper Ownership of Radio Stations, 9 Fed. Reg. 702

(1944).

10In addition to the divestiture orders listed above, the

Commission has required, for example, divestiture of syndication

companies by networks, see Iacopi v. FCC, 451 F.2d 1142,

1147 (9th Cir. 1971); divestiture of cable television systems

by telephone companies, General Telephone Co. of the Southwest

v. United States, supra, n. 4; divestiture of cable television

systems by television networks and by television licensees in

the same market, CATV, Second Report and Order, 23 F.C.C.2d

816 (1970); 47 C.F.R. §76.501 (1975). But see Cable Televi

sion Systems, Second Report and Order, 55 F.C.C.2d 540

(1975), appeal pending sub nom. National Citizens Committee

for Broadcasting v. FCC, D.C. Cir. No. 75-1933 (Sept. 22,

1975) (Amendment of divestiture requirement to conform to

standards established in Docket 18110; case being held in abey

ance pending this review). Also, the Commission has required

divestiture by the networks of spot sales representation for

their affiliates, Metropolitan Television Corp. v. FCC, 289 F.2d

874 (D.C. Cir. 1961).

n Revenue Act of 1943, §123, 58 Stat. 44 (Feb. 25, 1944),

26 U.S.C. §112(m); now 26 U.S.C. §1071. See H. Rep.

No. 1079, 78th Cong., 2d Sess. (1944) at p. 50.

— 6—

Subsequently, in the broadcast license renewal con

text, the Commission began in the 1960s to recognize

that the diversification factor, even without proven

abuses, may warrant loss12 or divestiture13 of license.

Seeking to consider the diversification issue on an

industry-wide basis, however, the Commission in 1968

instituted a new rulemaking proceeding, Docket 18110,

to revisit the question of local concentrations of control.

Multiple Ownership, Notice, 33 Fed. Reg. 5315

(1968). In 1970, again “to promote maximum diversi

fication of programming sources and viewpoints,” id.,

the Commission barred future creation or transfer of

TV-radio (AM/FM) combinations. Multiple Owner

ship, First Report and Order, Docket 18110, 22 F.C.C.

2d 306 (1970) (A. 33) (hereafter, First Report). The

Commission held to the view that “60 different licensees

are more desirable than 50, and even that 51 are

more desirable than 50.” Id., 22 F.C.C.2d at 311,

f 21. (A. 43).

B. The 1970 Proceeding, Docket 18110.

1. The Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking.

Concurrently with its First Report, the Commission

issued a Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, Mul

tiple Ownership, Docket 18110, 22 F.C.C.2d 339

12WHDH, Inc., 16 F.C.C.2d 1 (1969), aff’d sub nom.,

Greater Boston Television Corp. v. FCC, 444 F.2d 841 (D.C.

Cir. 1970), cert, denied 403 U.S. 923 (1971) (TV license

granted to competing applicant but case “sui generis” because

renewal applicant had only a four month license). See also

Midwest Radio-Television, Inc., 16 F.C.C.2d 943, 18 F.C.C.2d

1011 (1969) (media concentration issue designated for hearing

apart from questions of abuse), deferred, 24 F.C.C.2d 625

(1970).

lsFrontier Boradcasting Co., 21 F.C.C.2d 570 (1970), dis

missed for voluntary divestiture, 35 F.C.C.2d 875 (1972).

- 7

(1970) (A. 101), proposing to require divestiture with

in five years of all existing newspaper-broadcast or

television-radio combinations in a single market. Future

creation or transfer of newspaper-broadcast combina

tions would also be barred, for, the Commission found,

“ [i]t has now become clear that the most significant

aspect of the problem is the common control of tele

vision stations and newspapers of general circulation.

. . . [T] he public looks primarily to these two sources

for its news and information on public affairs.” Id.,

22 F.C.C.2d at 344, f 26 (A. 111).

As then Chairman Dean Burch described the matter

in his concurring opinion:

There are only a few daily newspapers in each

large city and their numbers are declining. There

are only a few powerful VHF stations in these

cities, and their numbers cannot be increased.

Equally important, the evidence shows that the

very large majority of people get their news in

formation from these two limited sources. Here

then is the guts of the matter. Id., 22 F.C.C.2d

at 350 (A. 124).

During the next five years, while the Commission

considered the concentration question by rulemaking,

it deferred specific license challenges based on undue

concentration of control grounds to this proceeding.14 * 21

u See, e.g., Columbus Broadcasting Coalition v. FCC, 505

F.2d 320, 325 (D.C. Cir. 1974); Stone v. FCC, 466 F.2d

316, 331 (D.C. Cir. 1972); Hale v. FCC, 425 F.2d 556

(D.C. Cir. 1970); Scripps-Howard Broadcasting Company, 31

F.C.C.2d 1090 (1971); Federation of Citizens Ass’ns (D.C.),

21 F.C.C.2d 12 (1969). In Hale, supra, Judge Tamm concurred

to note that Docket 18110 offered “some hope that the Com

mission will finally come to grips with the grave problem

inherent in the rising concentration of ownership in the mass

media. . . .” Id., 425 F.2d at 566.

~ -8 —

Indeed, the Commission even deferred such questions

in ongoing adjudicatory hearings to this rulemaking.1"

2. The Second Report and Order.

Finally, in 1975, after extensive rulemaking proceed

ings, and spurred by Congress and the courts,10 the

Commission issued its Second Report, Multiple Owner

ship, 50 F.C.C.2d 1046 (1975) (A. 134). The Com

mission prohibited the creation of future television-

newspaper combinations in the same community. Even

though it found the record inconclusive on the question

of whether actual abuses stemmed from broadcast-news

paper cross-ownership, the Commission acted to increase

the diversity of media voices.

The Commission also determined that divestiture was

an appropriate remedy to implement its new standard,

but applied it in only 16 of the nation’s smallest

markets, where one entity controlled an absolute mo

nopoly over the local daily newspapers and broadcast

stations. Second Report, 50 F.C.C.2d at 1081-82, 114,

1098 (A. 204-06, 242).

As long as the community had one other signal,

however, the Commission grandfathered the existing

media cross-owner from future license challenge. Re

newal hearings on undue concentration of control issues 15 16

15E.g., Chronicle Broadcasting Co., 40 F.C.C.2d 775, 796

(1973); Midwest Radio-Television, Inc., 24 F.C.C.2d 625, 627

(1970).

16See, e.g., H.R. 12993, 93d Cong., 2d Sess., March 28,

1974 (requiring FCC to resolve Docket 18110 within six

months), H. Rep. No. 93-961, 93d Cong., 2d Sess. (hereafter,

House Report) at p. 23; S. Rep. No. 93-1190, 93d Cong.,

2d Sess. (hereafter Senate Report) at pp. 14-15, 22 (action

required on Docket 18110 by end of calendar year); Columbus

Broadcasting Coalition v. FCC, supra, n. 14, 505 F.2d at

330.

would thereafter be foreclosed unless economic monop

olization under the Sherman Antitrust Act could be

demonstrated. Id., 50 F.C.C.2d at 1088 (A. 218).17

With respect to divestiture, the Commission claimed

that “local ownership,” “continuity of operations,” and

“local economic dislocations” outweighed the suddenly

“abstract,” and “mere hoped for gain in diversity.”

Second Report, 50 F.C.C.2d at 1078 (A. 196-98).

The Commission noted, in addition, that all licensees

who divested to meet the new standard, whether re

quired to divest or not, would receive beneficial tax

certificates under 26 U.S.C. §1071. Id., 50 F.C.C.2d

at 1085, n. 45 (A. 211).18

“ Subsequent cases have shown that the Commission has

not followed this extremely difficult standard. E.g., WGAL-

Television, Inc., 62 F.C.C.2d 527 (1976) (FCC refused to

designate issue on economic monopolization since it had neither

the expertise nor experience to enforce the antitrust laws).

See decision below, NCCB, 555 F.2d at 966, n. 108 (A.

428-29).

18Of the seven Commissioners, six either concurred or dis

sented. Commissioners Lee, Reid, and Washburn concurred;

Commissioners Hooks and Robinson concurred in part and

dissented in part; and Commissioner Quello issued a separate

statement which he did not characterize.

Commissioner Quello objected to the Commission’s failure

to adopt policies or rules requiring operational separation of

commonly owned newspaper-broadcast combinations, and urged

“extreme vigilance on a case-by-case basis.” (A. 277). Commis

sioner Hooks joined him on this point, and also dissented

in part because: “I cannot join my colleagues in limiting divesti

ture to pure monopoly instances while ignoring other circum

stances where the problem could be as bad or worse.” (A.

273).

Commissioner Robinson filed a comprehensive opinion arguing

for a structural rather than a behavioral approach to concentra

tion. He noted that the decisional standard of proof used

by the Commission in evaluating the record reversed the tradi

tional assumption “that a competitive, unconcentrated ownership

structure is prima facie in the public interest” (A. 295). This,

he argued, in essence approves “how some broadcasters regard

their licenses as property,” a view “simply at odds with our

statute.” (A. 296, n. 20).

3. Reconsideration.

On reconsideration, Multiple Ownership, 53 F.C.C.

2d 589 (1975) (A. 317) (hereafter, Reconsideration),

the Commission rebuffed industry pleas to adopt no

rules in this field and reiterated its belief in the guiding

premise of the rule. It noted: “ [W]e again must reject

[the] argument that commonly owned media provide

diversity. It is unrealistic to expect the same level

of diversity as would be offered if the entities were

under separate ownership.” Id., 53 F.C.C.2d at 592,

n. 9 (A. 323).

But the Commission maintained diversity is primary

only “when it can be achieved without hardship or

disruption.” Id. at 592, 51 8 (A. 324). For instance,

the Commission stated that if any new “egregious situa

tions” or effective monopolies should arise due to the

loss of currently existing competitive services, those

stations would not have to divest. Id,, 53 F.C.C.2d

at 590-91 (A. 320).

C. The Court of Appeals Decision.

Upon appeals brought by NCCB, several licensees

facing divestiture, the National Association of Broad

casters, and the American Newspaper Publishers As

sociation, the Court of Appeals unanimously reversed

the Commission (A. 339). It upheld the Commission’s

assertion of authority to act to increase diversity pro

spectively even though the Commission had found no

established record of actual abuses flowing from cross

ownership. But the Court reversed the Commission’s

decision that such a record is necessary before divest

iture of existing cross-ownerships could be ordered

(A. 415-31). The Court examined the reasons put

11—

forth by the Commission for this inconsistent position,

and found them, upon thorough analysis of the record,

to be invalid and unsupported by the record. As it

later summarized:

[W]e were faced with a situation in which the

Commission had treated three indistinguishable

groups very differently. Because of this, steps

had to be taken to restore consistent administra

tive treatment. Since the only consistent and court-

approved policy in this field was that which we

approved in affirming the Commission’s prospec

tive rules, and because no valid reasons had been

given by the Commission for departing from

this policy of giving diversity of media ownership

controlling weight, we ordered the Commission to

take further steps to ensure that everyone would

be consistently treated under the standard already

adopted for new license applicants (subject, of

course, to an appropriate waiver procedure, which

we also ordered the Commission to adopt, but

which it had already indicated would be available

with respect to the egregious 16). NCCB, 555

F.2d 967, 969-70 (A. 443).

The Court supported the above conclusion with the

following analysis:

(1) The Commission had the authority to promul

gate prospective rules prohibiting cross-ownership even

though the record was inconclusive on the question

of whether actual “abuses” flowed from newspaper-

broadcast ownership. Its authority flows from long-

established principles which indicate that the Commis

sion could act to increase diversity of broadcast media.

The Commission’s action based on diversity is sup

ported by the fact that the Commission had consistently

— 12—

acted on diversity principles with the repeated sup

port of the Supreme Court and the courts of appeals

(A. 362-88).

(2) But contrary to these established principles fa

voring diversity, the Commission when it considered

divestiture of presently co-located facilities insisted on

the need for actual evidence of abuses. And while

the Commission made reference to differentiating fac

tors between present and future licensees, the Court

found that the Commission had either no record support

for them or the Commission had weighed them in

a manner inconsistent with past practice. First, in this

regard, the Court reviewed the Commission’s considera

tion of harm to the public interest that might result

from the reduction of the quality of broadcast program

ming if divestiture were ordered. Here the Court found

that the Commission had found no basis in the record

to support such a proposition. Next, the Court examined

the competing policies that the Commission had as

serted to support its shift of emphasis. These the Court

found had in all instances in the past been given

lesser weight than diversity. Moreover, the Court found

that to weigh these new policies in the way the Com

mission had, would require “massive shifts” in Commis

sion practice with respect to license transfers (A. 394-

430).

(3) Finally, the Court held that there was no record

evidence that justified the disparate treatment of the

16 “egregious” cases that were ordered to divest by

the Commission (A. 430).

The Court concluded, 555 F.2d at 960 (A. 431)

that:

For these reasons expressed above, we believe

the opposite presumption is compelled, and that

— 13—

divestiture is required except in those cases where

the evidence clearly discloses that cross-ownership

is in the public interest.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.

The Federal Communications Commission has broad

authority under the Communications Act to prevent

monopolization or concentration of control over the

media of mass communications. The Commission’s long

standing practice of considering newspaper ownership

in determining qualifications for broadcast license ap

plicants on an ad hoc basis has been consistently upheld

by the courts.

Therefore, the FCC’s adoption of a rule barring

future acquisition of newspaper broadcast cross-owner

ships in the same market is a reasonable exercise

of the agency’s authority. Indeed, Congress has recently

expressed its condonance of the Commission’s use of

its rulemaking authority in this way. Structural diversi

fication, furthermore, serves rather than abridges basic

First Amendment principles.

While a federal agency has considerable discretion

to apply its rules and policies as best meets the public

interest, it is restricted from arbitrary and capricious

rulemaking. A court of appeals’ review of an agency

rulemaking is narrow, but searching. Its determination

as to whether an agency has support in the record

for its reasoning is narrowly reviewed by this Court.

Although the Commission has consistently found di

versification to be a primary licensing goal, it denigrat

ed this factor without rational explanation, in consider

ing whether to apply its new one-to-a-market policy

to existing cross-owners. The Commission ignored its

own presumptions and policies favoring diversification,

— 14—

derived from the Communications Act, in placing a

burden on the public to show tangible harm from

such existing cross-ownerships before requiring divest

iture. Furthermore, if it were necessary, the Commis

sion had substantial evidence of tangible harm before

it.

Contrary to the Commission’s view, divestiture is not

a harsh and severe remedy. Nor is it a retroactive

rule, since it allows licensees ample time to comply

with the policy in the future. In any event, broadcasters

have no property right to their licenses, which last

only three years. An applicant seeking renewal, there

fore, is subject to the rules and policies extant at

the time of renewal, not at the time of the original

grant. And broadcasters have long been on notice

of the Commission’s intention to promote structural

diversity.

The Commission claims that it applied a wholly dif

ferent standard to existing operations because it feared

that disruption to the industry might result and also

because it wanted to assure the public of the best

practicable service. However, diversity of ownership

is one element of the “best practicable service” licensing

goal, and the Commission has traditionally found other

individual elements of that standard to be secondary

to the primary goal of diversification. Certainly this

is true for the elements of “local ownership,” “conti

nuity of operation” and “local economic dislocation.”

The Commission’s speculations about harmful effects

in these areas from divestiture are unjustified by reason

or by the record.

There is no reason to believe that new owners would

not provide equal or better local broadcast service,

as well as greater diversity of information sources.

15—

Moreover, licensees have ample time and special tax

benefits which alleviate any legitimate concern over

their private economic interest. The Commission’s prac

tice of approving scores of transfer applications each

year, furthermore, demonstrates the fallacy of the Com

mission’s concern for these makeweight arguments.

The line which the Commission drew to require

divestiture by some but not all licensees is arbitrary

and irrational. It supposedly requires divestiture by

“effective monopolies,” but uses a diversity-based rather

than a monopoly-based criterion to determine whether

concentration in a given locality meets that standard.

Conversely, in protecting existing licensees against

petitions to deny based on concentration of control

grounds, the Commission adopted a Sherman Act “eco

nomic monopolization” standard, which it has since

admitted it is ill-equipped to administer. The Commis

sion has no provision, furthermore, for considering

divestiture on an ad hoc basis, and will not consider

showings by petitioners that the underlying goals of

the general policy, viz,., diversity and competition, would

be served by divestiture rather than renewal of license.

In sum, this case is simply a court reversal of

arbitrary and capricious action by a federal agency

which has lost sight of its mandate to regulate in

the public, not private, interest. The Court of Appeals

properly reminded the agency of its own long-standing

presumptions, and attendant burdens of proof. On re

mand, the Commission would retain discretion to adopt

a rule which does not draw arbitrary lines aimed at

protecting private interests at the expense of the pub

lic’s.

— 16—

ARGUMENT.

I.

THE COURT OF APPEALS PROPERLY UPHELD THE

COMMISSION’S AUTHORITY TO ADOPT A RULE

BARRING FUTURE ACQUISITIONS OF NEWSPAPER-

BROADCAST COMBINATIONS.

A. Congress Has Given the Commission the Latitude

and Authority to Consider Newspaper Ownership

in Licensing Broadcast Stations.

This Court has consistently upheld the broad authori

ty of the Federal Communications Commission to adopt

regulations interpreting the Congressionally delegated

standards of the “public interest, convenience and neces

sity.”19 The Commission’s power under that standard,

and its mandate generally to “encourage the larger and

more effective use of radio in the public interest,”

47 U.S.C. §303 (g) (1970), allows the agency flexibil

ity to adopt regulations to meet the “fluid and dynamic”

qualities of broadcast regulation, including those relat

ing to concentration of control over ownership of broad

cast stations. Id. “Congress moved under the spur of

a widespread fear that in the absence of governmental

control the public interest might be subordinated to

monopolistic domination in the broadcast field.” F.C.C.

v. Pottsville Broadcasting Co., 309 U.S. 134, 137

(1940).

In United States v. Storer Broadcasting Co., 351

U.S. 192, 203 (1956), the Court upheld the FCC’s

numerical limitation on the number of broadcast licenses

one person could hold nationwide, stating:

Congress sought to create regulation for public

protection with careful provision to assure fair

19NBC v. United States, supra, n. 6, 319 U.S. at 219

(1943).

1 7 -

opportunity for open competition in the use of

broadcasting facilities. Accordingly, we cannot in

terpret §309 (b) as barring rules that declare a

present intent to limit the number of stations

consistent with a permissible “concentration of

control.”

And in United States v. Radio Corp. of America,

358 U.S. 334, 351-52 (1959) the Court accepted

the possibility that

[A]ntitrust considerations alone would keep the

statutory [licensing] standard from being met, as

when the publisher of the sole newspaper in an

area applies for a license for the only available

radio and television facilities which, if granted,

would give him a monopoly of that area’s major

media of mass communication.

More recently, this Court upheld the Commission’s

authority to regulate communications media ancillary

to its authority over broadcasting even absent express

provision in the Act.20

Accordingly, the Commission’s general authority to

take newspaper ownership into consideration in deter-

20United States v. Midwest Video Corp., 406 U.S. 649

(1972); United States v. Southwestern Cable Co., 392 U.S.

157 (1968). Review of the Commission’s attempted regulation

of data processors in GTE Service Corp. v. FCC, 474 F.2d

724 (2d Cir. 1973) is not to the contrary (NAB Br. at

24-25). There the Commission’s authority to regulate activities

of communications common carriers in the computer field was

upheld, but regulations directly controlling the computer industry

were reversed as beyond the Commission’s jurisdiction and intent.

Id., 474 F.2d at 733. The GTE Court specifically distinguished

the newspaper-broadcast cross-ownership situation as within the

agency’s authority. Id., 474 F.2d at 734. In the present case,

the Commission is regulating qualifications for owning broad

cast stations. It is not regulating newspapers. (A. 378, n.

41).

18

mining broadcast licensing qualifications is clear.21

And as this Court has warned, courts should not inter

fere “in the absence of compelling evidence that such

was Congress’ intention * * * to prohibit administra

tive action imperative for the achievement of an agen

cy’s ultimate purposes.” 22

The American Newspaper Publishers Association

(ANPA) and the National Association of Broadcasters

(NAB), along with some amici curiae, argue that

the Commission’s expansive powers do not include the

ability to bar newspapers from acquiring broadcast

stations in the same locality. They base the argument

on (1) a limited and selective review of subsequent

Congressional statements, none of which resulted in

an amendment to the Communications Act; (2) an

opinion of one former FCC General Counsel in 1938,

who was looking at a somewhat different question

under different circumstances, and (3) dicta from a

1942 court of appeals decision. While the petitioners’

arguments were extensively considered below and dis

missed by the Court, NCCB, 555 F.2d at 947-54 (A.

362-88), the vigor with which the petitioners again

assert various Congressional statements requires some

21E.g., Greater Boston Television Corp. v. FCC, supra, n.

12; Joseph v. FCC, 404 F.2d 207 (D C. Cir. 1968); McClatchy

Broadcasting Co. v. FCC, 239 F.2d 15 (D.C. Cir. 1956),

cert, denied, 353 U.S. 918 (1957); Scripps-FIoward Radio,

Inc. v. FCC, supra, n. 4; Mansfield Journal Co. v. FCC,

180 F.2d 28 (D.C. Cir. 1950); Plains Radio Broadcasting

Co. v. FCC, 175 F.2d 359 (D.C. Cir. 1949); Frontier Broad

casting Co., supra, n. 13.

22United States v. Southwestern Cable Co., supra, n. 20,

392 U.S. at 177, quoting Permian Basin Area Rate Cases,

390 U.S. 747, 780 (1969).

1 9 -

exposition beyond the Court of Appeals review. See

also Second Report, 50 F.C.C.2d at 1051-52 (A.

144-46).

ANPA, NAB and some of their amici cite various

Congressional statements made between 1946 and 1952.

They argue that Congress has expressed its intention

that the FCC not “discriminate” against newspaper

owners. They treat certain legislative statements as

if legislation had in fact been adopted precluding FCC

consideration of newspaper ownership in licensing

broadcasters.

Neither the Commission23 nor the Court of Appeals24

was persuaded by Congress’ inaction. Indeed, the

Court noted that the general use of subsequent legisla

tive activity is not useful to determine the meaning

of the original statute, citing United States v. Wise,

370 U.S. 405, 411 (1961). NCCB, 555 F.2d at 952,

n. 41 (A. 378).

Nevertheless, recent Congressional actions conclusive

ly demonstrate Congressional concurrence with the

Commission’s view that it has statutory authority to

bar newspaper ownership of co-located broadcast sta

tions by the rule here in issue. During the pendency

of this rulemaking, and at the instigation of the NAB

and others,25 both the House of Representatives and

23Second Report, 50 F.C.C.2d at 1051 (A. 144-45).

2iNCCB, 555 F.2d at 952 (A. 378).

25See, e.g., “NAB Presses Drive for Renewal Relief,” Broad

casting Magazine, December 4, 1972 at 38; “Whitehead Bill

Joins the Crowd Seeking to Ease Renewal Trauma,” Broadcast

ing Magazine, January 1, 1973 at 24-25.

-2 0

the Senate adopted bills expressing their intention that

the FCC not consider cross-ownership at license renewal

time unless the Commission adopted rules prohibiting

such interests, and gave the renewal applicant a rea

sonable opportunity to divest to conform to the new

rules.26 The House Report quotes from the Further

Notice in Docket 18110, f 34 [A. 116], where the

Commission proposed through rule to require divestiture

of co-located commonly owned daily newspapers and

broadcast stations. It then states that “if cross-ownership

is to be prohibited or management or ownership struc

tures or their composition are to be prescribed, it

must be done by rules. . . .” Id. at 19. There can

be little question that the House Committee viewed

the Commission as having jurisdiction to act as it

proposed in Docket 18110.

Similarly, in the Senate Report, the Committee re

ferred to the Docket 18110 proposal to bar newspaper

cross-ownership of broadcast stations, id. at 14, and

concluded, “The Commission has rules regarding mul

tiple ownership, and there appears to be no reason

why rules regarding cross-ownership would not also

be appropriate.” Id. at 15. Both the House and Senate

adopted measures to require the Commission, in view

of its delay, to conclude Docket 18110 within a certain

time period. House Report, supra, n. 16, at 25; Senate

Report, supra, n. 16, at 14-15, 22; Congressional Quar

terly Almanac, supra, n. 26, at pp. 714-17. However,

conferees were never selected in the House, and the

bills eventually died. Id. No member of the House

or Senate Commerce Committees, however, expressed

26Congressional Quarterly Almanac (Vol. XXX), pp. 714-

17 (1974), House Report, supra, n. 16, at pp. 18-19; Senate

Report, supra, n. 16, at pp. 14-15.

— 21—

the belief that the Commission did not have the au

thority to consider newspaper ownership of broadcast

stations or to adopt the proposal in the Further Notice

in Docket 18110.27

B. The First Amendment Is Served Rather Than

Abridged by a Content Neutral Rule Promoting

Diversity of Information Sources to a Local Com

munity.

ANPA (Br. at 17-26) and the NAB (Br. at 25-

37) argue, again, that their individual right to broadcast

should prevail over the public’s right to diversity of

information sources. This is a tired argument, and

one which this Court has rejected many times.

“No one has a First Amendment right to a license

or to monopolize a radio frequency; to deny a station

license because ‘the public interest’ requires it ‘is not

a denial of free speech.’ ” Red Lion, supra, n. 3,

395 U.S. at 389, citing NRC v. United States, supra,

n. 6, 319 U.S. at 227. “It is the right of the viewers

and listeners, not the right of the broadcasters, which

is paramount.” Id., 395 U.S. at 390.

In upholding the FCC’s Fairness Doctrine, then,

the unanimous Red Lion Court conclusively established

the validity of FCC regulations aimed at promoting

diversity. And the Court in Buckley v. Valeo, 424

U.S. 1, 49, n. 55 (1976), reaffirmed this view where

27ANPA’s argument in this Court to the effect that the

FCC does not have authority to prohibit newspapers from

becoming broadcast licensees is in direct contradiction to its

position before the Commission that the Commission has denied

newspaper ownership in a hearing setting in the past, and

that rather than enact a rule, the Commission should continue

to consider newspaper ownership on an ad hoc basis. ANPA

Comments, Docket 18110 (A. 715-16). See generally Reply

Comments of Stephen R. Barnett (A. 776 ff.).

■22-

it stated that “in contrast to the undeniable effect

of . . . [unconstitutional campaign expenditure limita

tions], the presumed effect of the Fairness Doctrine

is one of ‘enhancing the volume and quality of coverage

of public issues.’ ”

The Fairness Doctrine “may well mark the outer

limits of a permissible diversification policy which relies

on direct government control over the content of broad

cast programs.” NCCB, 555 F.2d at 950 (A. 371).

But the structural ownership rules here under review

are far less restrictive, from a First Amendment perspec

tive, because they are totally content neutral. They

do not ban, punish, or mandate what may be published

or aired.28

The Commission’s rules, moreover, do not restrict

a licensee from publishing a newspaper. While it does

not allow one making that choice to retain a broadcast

license in the same locality, this is consistent with

long-standing prohibitions against monopolization of the

press (Associated Press v. United States, supra, n.

3, 326 U.S. at 20), and against domination of broadcast

frequencies. Thus the Commission will not allow one

entity to obtain two television licenses in the same

locality; it can also refrain from issuing a broadcast

28This distinguishes the Commission’s content neutral, struc

tural diversity rules from the other major First Amendment

cases cited by petitioners. Thus in Grosjean v. American Press

Co., 297 U.S. 233, 250 (1936), the newspaper tax was “a

deliberate and calculated device in the guise of a tax to limit

the circulation of information to which the public is entitled. . . .”

And in Miami Herald v. Tornillo, 418 U.S. 241, 251 (1974),

the Court struck down a right of reply statute which exacted

“a penalty on the basis of the content of a newspaper.” The

Court of Appeals, furthermore, pointed out that “ [fjreedom

of the press "does not necessarily shield newspaper publishers

from regulation that may make publication more difficult.”

Id. (A. 383).

^ 2 3 -

station license to one who has a concentration of

other media of mass communications.

Indeed, content neutral rules aimed at maximizing

information sources and mass media in a particular

locality further rather than abridge the goals of the

First Amendment. In addition, in view of the Commis

sion’s need, at times, to investigate allegations of be

havioral abuses of local cross-ownerships,29 structural

measures taken in advance to prevent the possibility

of such abuses will also promote the public interest

and the First Amendment.

C. The Commission’s Adoption of Its Prospective Ban

Is a Reasonable Exercise of Its Discretion.

In assessing whether or not the Commission was

“arbitrary or capricious” in adopting a particular rule

the courts of appeals have a narrow but searching * 40

29See Mansfield Journal Co. v. FCC, supra, n.21, 180 F.2d

at 35 (“the way the newspaper is operated in relation to

other media of communication is material”). See also Chronicle

Broadcasting Co., 16 F.C.C.2d 882 (1969), renewal granted,

40 F.C.C.2d 775 (1973). As some have suggested, continued

cross-ownerships may invite the government into the newsrooms

of newspapers or broadcast stations in order to investigate

legitimate claims, supported by extrinsic evidence, of news man

agement, and other abuses contrary to the public interest. Oral

Argument of then NCCB Counsel, Frank W. Lloyd (A. 925,

928-29); S. Barnett, “Cross-Ownership of Mass Media in the

Same City.” (Barnett Report) (A. 990, 1001-02, 1011-21,

and articles cited therein).

Petitioners have suggested that the Barnett Report was not

properly before the Court of Appeals because they allege it

was not officially part of the record. Certainly the Commission

had an opportunity to pass upon it, however, since Commission

ers Hooks and Robinson each referred to it in their dissents.

Second Report, 50 F.C.C.2d at 1108, 1120, n. 17 (A. 269,

293). This is sufficient to meet the statutory test of 47 U.S.C.

§405. Office of Communication of the United Church of Christ

v. FCC, 465 F.2d 519, 523 (D.C. Cir. 1972). And as the

Court of Appeals noted, “much of the report consists of discus

sion of cases in the public record. . . .” NCCB, 555 F.2d

at 959, n. 71 (A. 403).

- 2 4 -

scope of review, Citizens to Preserve Overton Park

v. Volpe, 401 U.S. 402, 415 (1971), while that of

this Court is more narrow and circumscribed. Mobil

Oil Corp. v. FPC, A ll U.S. 283, 309 (1974).

The Commission need not await the feared result

before acting to prevent the potential for abuses of

concentrations of control over the mass media, and

to foster diversity.30

The Commission has traditionally taken newspaper

ownership into account in licensing broadcast stations,31

and the present rule is a codification and extension

of existing Commission practice. By adopting a rule,

rather than continuing to proceed on an ad hoc basis,

the Commission is protecting newspaper owners from

investing in an operation where renewal expectancies

may in some instances be outweighed at renewal time

by the diversification factor. See Citizens Communica

tions Center v. FCC, supra, 447 F.2d at 1213-14,

n. 36 (1971). 20

30See, e.g., Buckley v. Valeo, supra, 424 U.S. at 29, 49,

n. 55, where the Court upheld a limitation on campaign contribu

tions in part because of the potential for abuse, and alluded

to the Fairness Doctrine’s “presumed effect” to increase the

total amount of speech. Accord: Red Lion, supra, n. 3, 395

U.S. at 393; United States v. Southwestern Cable Co., supra,

392 U.S. at 176-77 (Commission can plan in advance with

cable television, instead of waiting to react to events); FCC

v. RCA Communications, Inc., 346 U.S. 86, 96-97 (1953)

(“the possible benefits of competition do not lend themselves

to detailed forecast” ); GTE Service Corp. v. FCC, supra, n.

20, 474 F.2d at 731 (certain prohibitions imposed against

communications common carriers relating to data processing

affirmed on “potential domination” rationale); Mt. Mansfield

Television, Inc. v. FCC, 442 F.2d 470, 487 (2d Cir. 1971)

(primetime access rule affirmed on potential of curbing competi

tive restraints and network dominance in syndication); First

Report, supra, 22 F.C.C.2d at 311, % 20 (A. 43) (“remedial

action need not await the feared result”).

slSee supra, n. 21.

■25-

Adoption of the rule based on the Commission’s

intent to foster diversity of expression, even without

evidence of past abuses, is reasonable because the Com

mission has long presumed that “it is unrealistic to

expect the same level of diversity [from commonly

owned mass media entities] as would be offered if

the entities were under separate ownership.” Reconsid

eration, 53 F.C.C.2d at 592, n. 9 (A. 323). See

also Second Report, 50 F.C.C.2d at 1050, f 14 (A.

142) (need for diversified ownership). “ [Centraliza

tion of control over the media of mass communications

is, like monopolization of economic power, per se un

desirable.” First Report, 22 F.C.C.2d at 310, f 17

(A. 41).

In sum, as the Court below held, “ [t]he prospective

ban is an attempt to promote diversity without govern

ment regulation or supervision over speech.” NCCB,

555 F.2d at 950 (A. 373). The Court observed after

reviewing the record here that although there is no

guarantee that the prospective ban will increase diver

sity, this did not make the attempt irrational nor was

it unreasonable for the Commission to license an inde

pendent new voice. Id. (A. 374). “The ‘search for

truth,’ ” the Court stated, “will be facilitated by govern

ment policy that encourages the maximum number

of searchers.” Id. at 951. (A. 374).

— 26

II.

THE COURT OF APPEALS CORRECTLY FOUND THE

COMMISSION’S SECOND REPORT ARBITRARY IN

THE APPLICATION OF ITS NEW CROSS-OWNERSHIP

STANDARDS TO EXISTING COMBINATIONS.

Having found that the Commission was authorized

and that it acted reasonably in applying its “duopoly”

rules to local newspaper-broadcast cross-ownerships, the

Court of Appeals then looked to whether the Commis

sion’s enforcement mechanism for applying the new

standard to existing cross-ownerships was reasonable.

For, while the Commission applied the standard to

future acquisitions and certain small licensees who con

trolled absolute monopolies in their cities, it exempted

and indeed immunized all other cross-ownerships in

the country, regardless of the degree of concentration

they held.

The Court thoroughly searched for a rational basis

for the Commission’s action, but found the record

bare of factual support and the premise of its action

unreasoned. The Commission argues that for existing

combinations, other factors such as “best practicable

service” and disruption to the industry and individual

owners come into play. But as we demonstrate below,

the Court correctly held that all of the Commission’s

fears of “harmful effects” from divestiture were ground

less, its application of countervailing factors irrational,

and that the Commission inexplicably abandoned its

traditional presumption in favor of diversification of

media outlets.

— 27—

A. The Commission Erred in Its Assessment of the

Burden of Proof in This Proceeding.

The Court of Appeals correctly held that the Com

mission erred in requiring the public to show evidence

of tangible harm from cross-ownerships before requir

ing across the board divestiture.32

32Moreover if such evidence were necessary, the Commission

had sufficient evidence before it to act affirmatively on the

divestiture issue. Contrary to the Commission’s statements, there

are numerous examples of detriments, including actionable abuses

warranting a hearing on denial of license from co-located

newspaper-broadcast cross-ownerships. E.g., WGAL-Television,

Inc., supra, n. 17 (newspaper preference of TV station); West

ern Connecticut Broadcasting Co., 47 F.C.C.2d 432, 433-35

(1974) (concentration extreme and possible discrimination

against political candidates); WPIX, Inc., 20 F.C.C.2d 298,

300 (1970) (news management, but no concentration of control

issue designated); Chronicle Broadcasting Co., supra, n. 15

(news management); Midwest Radio-Television, Inc., supra, n.

12 (cross subsidizations); WHDH, Inc., supra, n. 12 (lack

of editorializing).

In large part, however, any deficiencies that do exist in

the record can be attributed to the Commission’s unwillingness

to examine such issues when they were presented in licensing

and complaint proceedings. Instead, the Commission has for

years deferred examination of actual evidence in deference to

its overall examination of its policies carried on in this rule-

making. See, supra, nn. 14-15.

Furthermore, the Commission is very reluctant to designate

allegations of abuse of a cross-ownership for hearing unless

the case is well-established. Yet it is nearly impossible to meet

the Commission’s burden for hearing without discovery proce

dures, which, in Catch 22 fashion, are not available until a

case is set for hearing. See, e.g., Bilingual Bicultural Coaltion

on Mass Media v. FCC, 492 F.2d 656, 659 (D.C. Cir. 1974);

Hale v. FCC, supra, n. 14, 425 F.2d at 566 (Tamm, concur

ring).

There were, in addition, many allegations in individual cases

before the Commission which, while perhaps not warranting

a renewal hearing in every case, nonetheless offered the Com

mission the opportunity, had it been truly interested, to pursue

the matter in rulemaking. These include allegations raised in

Newhouse Broadcasting Corp. (W API-TV), 59 F.C.C.2d 218,

231-39 (1976); Daily Telegraph Printing Co., 59 F.C.C.2d

185 (1976); McPherson Broadcasting Co., 54 F.C.C.2d 565

(This footnote is continued on next page)

— 28—

By placing the burden on those who sought diversi

fication over concentration, the Court found, the Com

mission had acted in a manner contrary to the general

presumption that precipitated the rulemaking and ulti

mately the prohibition against future cross-ownerships:

namely that the Communications Act,33 the First

Amendment,34 and the Commission’s long-standing

(1975); A. H. Belo Corp., 46 F.C.C.2d 1075, 1081-88, 1091

(1974); RadiOhio, Inc., 38 F.C.C.2d 721, 751 (1975) (John

son, dissenting), aff’d sub nom. Columbus Broadcasting Coalition

v. FCC, supra, n. 14. See Johnson & Dystel, A Day In

The Life: The Federal Communications Commission, 82 YALE

L. J. 1575, 1607 (1973).

In addition, Professor Steven Barnett’s extensive documenta

tion in “Cross Ownership of Mass Media in the Same City”

(A. 990-1051), lists many instances from public records of

non-coverage, non-editorializing, news management to favor busi

ness interests, economic tie-ins between newspaper and broad

cast station advertising, and the like. Also, the Commission

heard personal testimony at oral argument as to the detrimental

effects of cross-ownerships in several cities. (A. 923, 933-

42). See generally, Commissioner Robinson’s dissent at A. 291.

The Commission’s Conglomerate Study Report might also

have contained important information. Although the pilot study

did reveal abuses, see Green, “Conglomerate Broadcasters Are

Faulted in FCC Pilot Study, Wider Inquiry Slated,” Wall Street

Journal, August 11, 1970, p. 32, the Commission has refused

to reveal large sections of its final report. National Citizens

Committee for Broadcasting, 56 F.C.C.2d 476 (1975), 57

F.C.C.2d 1060 (1976).

Finally, the Commission has recently designated an “undue

concentration of control” issue in a comparative renewal proceed

ing, based on the grandfathered renewal applicant’s proposed

extension of its service, citing the “duopoly” policy as of “over

riding decisional significance” and expressing “concern for divers

ity and competition.” McClatchy Newspapers, 40 P&F Radio

Reg. 2d 1393, 1403-04 (1977).

3SE.g., 47 U.S.C. §303(g) (1970) obligates the Commission

to “encourage the larger and more effect use of radio in

the public interest.” NCCB, 555 F.2d at 962-63. (A. 417).

S4E.g., “The First Amendment ‘presupposes that right con

clusions are more likely to be gathered out of a multitude

of tongues. . . .’ ” NCCB, 555 F,2d at 963 (A. 417-18),

citing Associated Press v. United States, 52 F.Supp. 362, 372

(S.D.N.Y. 1943), aff’d 326 U.S. 1 (1945). See also Red

Lion, supra, n. 3, 395 U.S. at 390.

— 2 9 -

policy35 favored diversification.36 Once the Commission

adopted the general proposition, the Court held, con

sistency required that the burden should properly have

shifted to the cross-owners to demonstrate why their

concentrations serve the “public interest, convenience

and necessity.” 47 U.S.C. §309 (1970). Instead, the

Commission deferred to the private economic interests

of the licensee over diversity and competition in the

media.