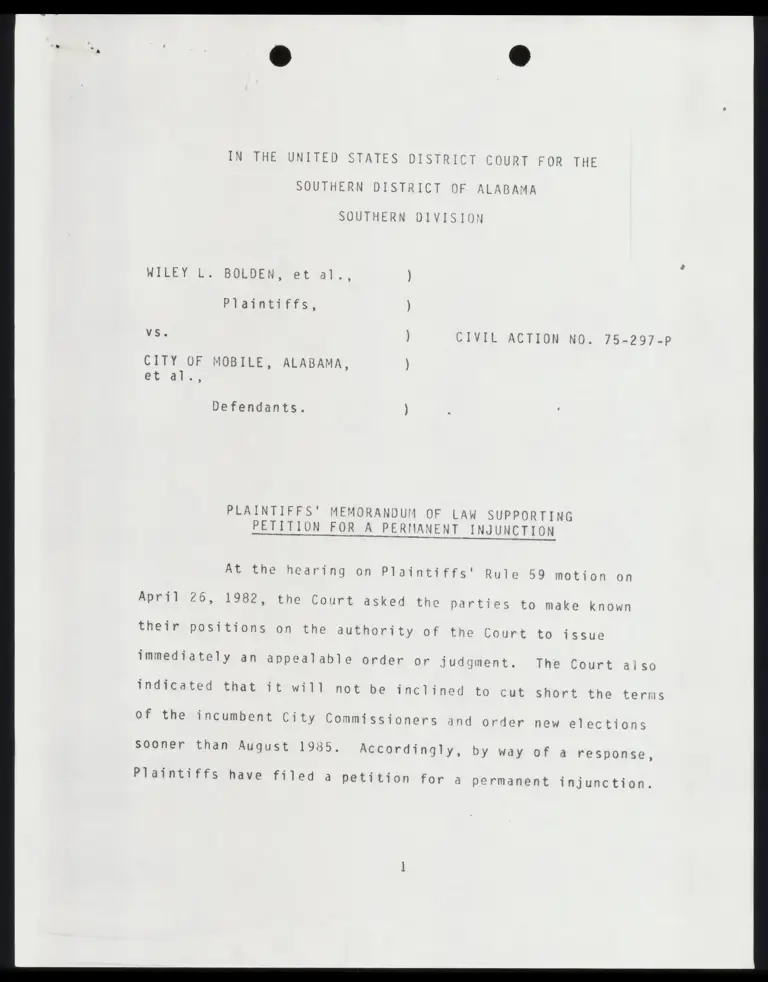

Plaintiffs' Memorandum of Law Supporting Petition for a Permanent Injunction; Plaintiffs' Petition for a Permanent Injunction

Public Court Documents

May 7, 1982

20 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Plaintiffs' Memorandum of Law Supporting Petition for a Permanent Injunction; Plaintiffs' Petition for a Permanent Injunction, 1982. 4745548f-cdcd-ef11-8ee9-6045bddb7cb0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4bfb55a1-7779-4f0d-9f17-99e4a4d15781/plaintiffs-memorandum-of-law-supporting-petition-for-a-permanent-injunction-plaintiffs-petition-for-a-permanent-injunction. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

WILEY |. BOLDEN, et al., )

Plaintiffs, )

VS. ) CIVIL ACTION NO. 75-297-p

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, )

et al.,

Defendants. )

PLAINTIFFS' MEMORANDUM OF LAW SUPPORTING

PETITION FOR A PERMANENT INJUNCTION

At the hearing on Plaintiffs' Rule 59 motion on

April 26, 1982, the Court asked the parties to make known

their positions on the authority of the Court to issue

immediately an appealable order or judgment. The Court also

indicated that it will not be inclined to cut short the terms

of the incumbent City Commissioners and order new elections

sooner than Auqust 1985. Accordingly, by way of a response,

Plaintiffs have filed a petition for a permanent injunction.

;

#

This memorandum of law will address reasons why the

injunction should be granted. However, should the Court deny

the injunction, it is Plaintiffs' present intention

immediately to appeal, so that there may be a timely

resolution of their claim to expeditious relief. ’

An Injunction Should be Entered Where the Court Retains

Jurisdiction For the Legislature to Enact a New Statute

The Supreme Court has explicitly disapproved the

procedure of withholding an injunction against an

unconstitutional or unlawful State statute while inviting the

Legislature to respond with its own remedy. Gunn Vv.

University Committee to End the War in Viet Nam, 393 U.S.

383 (1970). This is because "until a district court issues

an injunction, or enters an order denying one, it is simply

not possible to know with any certainty what the court has

decided ..." 1d. at 383, Rule 65{(d), Fed.R.Civ.P., was

designed to eliminate confusion when a federal court

determines that a State statute is unconstitutional in

certain respects. ld. at 389,

That requirement [of Rule 65(d)] is

essential in cases where private

conduct is sought to be enjoined,

as we did in [Longshoremen's Assn.

Local 1291 v. Philadelphia Marine

Yrade Assn., 359 U.5. 54, 7/9 (1957}].

Tt 1s absolutely vital in a case where

a federal court is asked to nullify a

law duly enacted by a sovereign State.

The restraint and tact that evidently

motivated the District Court in refrain-

ing from the entry of an injunctive order

in this case are understandable. But when

a three-judge district court issues an

opinion expressing the view that a State

statute should be enjoined as unconsti-

tutional -- and then fails to follow-up

with an injunction -- the result is un-

fortunate at best. For when confronted

with such an opinion by a federal court,

state officials would no doubt hesitate

long before disregarding it. Yet in the

absence of an injunctive order, they are

unable to know precisely what the three-

Judge court intended to enjoin and unable

as well to appeal to this Court.

Gunn supra, 399 U.S. at 389-91 (citation omitted).

Garza v. Smith, 450 F.2d 790 (5th Civ. 1971), cited by the

Defendants, failed to take notice of the Supreme Court's

instructions in Gunn, which was decided a year earlier. More

recently, the Fifth Circuit has distinquished Garza in a

manner that directly implies disapproval of its precedential

value. United States v, Mississippi Power & Light Co., 638

F.2d 899, 903, n.4 (5th Cir. 1981). There the Court of

Appeals accepted appellate jurisdiction over a decision of

the district court, even though the lower court had failed to

enter an injunction and had relied instead "on the

wh

y declaratory force of [its] decisions and on the good faith o

Sd

+

the parties." Id. at 903. The Fifth Circuit refused to

follow Garza, because the orders appealed from concerned

issues that had been remanded to the district court after an

appeal to the Supreme Court and were, therefore, "in effect a

continuation of the first appeals." 1d. It concluded that

the interests of justice and efficiency demanded immediate

resolution of the case. 638 F.2d at 903, citing Gillespie v.

United States Steel Corp., 379 U.S. 143, 152-53 (1964)

(which dictates that the Court of Appeals should give the

finality requirement a "practical rather than a technical

construction" and that the chief countervailing

considerations are "the inconvenience and costs of piecemeal

review on the one hand and the danger of denying justice by

delay on the other").

In any event, Plaintiffs have now acted to

eliminate any uncertainty by petitioning for a permanent

injunction. Without question, the dissatisfied parties may

appeal under 28 U.S.C. §1292(a) (1) if the Court either

grants or denies the injunctive relief asked for. United

States v. Mississippi Power & Light Co., supra 638 F.2d at

903. Where, as in the instant case, the timing of relief is

a critical issue, the parties are entitled to a ruling that

may be appealed immediately.

Plaintiffs Are Entitled to Early Interim Elections

If the Alabama Legislature fails or refuses to

provide a constitutionally acceptable remedy after it next

convenes, Plaintiffs and the class of black citizens they

represent are entitled to immediate interim city elections by

single-member districts, even though the terms of the

incumbent commissioners must be cut short. Taylor v. Monroe

County Board of Supervisors, 421 F.2d 1038 {5¢h Cir. 1970),

is squarely on point. There the district court had entered

an order in April 1969 that the Board of Supervisors must be

reapportioned. The incumbents had begun new terms in January

1968, which were due to expire in January 1972. The district

wv

court refused to order interim elections, the plaintiff

appealed, and the Fifth Circuit, on January 14, 1970,

reversed and remanded with instructions to hold interim

elections on or before July 1, 1970, if possible. The 1967

elections had taken place while the case was pending on an

earlier appeal. Then the Supreme Court extended one person,

one vote requirements to local governments in Avery v.

Midland County, 390 U.S. 471 (1967), and the Fifth Circuit

had reversed the judgment of the trial court and remanded

with instructions that a reapportionment be ordered. ld. at

1039. In the second appeal, the Fifth Circuit noted the

teaching of Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964), "that

the holding of court ordered elections is undesirable at best

caer? 421 F.2d at 1041, But, consistent with the mandate of

Reynolds that "judicial relief becomes appropriate only when

a legislature fails to reapportion according to federal

constitutional requisites in a timely fashion after having

had an adequate opportunity to do $0," 377 4.5. at 586, the

Fifth Circuit concluded

that the trial court should have

ascertained "expeditiously" just how

much time and effort would be involved

in preparing for and holding a special

election which would certainly have

committed legally elected officials to

have served at least more than half the

current term of office.

422 F.2d at 1041. The court noted that at the time the

district court had denied interim elections 31 of 48 months

of the incumbents' terms of office were still to run, whereas

less than 24 of the 48 months remained at the time of the

Fifth Circuit's decision. 421 F.2d at 1039, n.l. This made

the choice of equities "more difficult perhaps than it might

have been if the appeal had been expedited ...." 421 F.2d at

1039.

Of special relevance to the instant case is the

following passage from Taylor:

Much comfort, it seems, can be

taken by Plaintiffs-Appelliants from

the language of this Court in its

prior decision. Where we spoke of

“further proceedings expeditiously

conducted consistently with the holdings

of the Supreme Court and for appropriate

relief grounded thereon," we surely

meant something more than correcting the

abuse in time for an election for a

term to commence three and a half years

in the future.

421 F.2d at 1042, Surely, in light of the history of this

case, blacks in Mobile are entitled to no less expeditious a

remedy. The incumbent city commissioners began their new,

four-year terms on October 5, 1981. As of now, they stil]

have three years and five months of their present terms to

serve. Jo delay Plaintiffs' relief any longer than the end

of the next legislative session would be contrary to the

importance placed on constitutional voting rights by the

Supreme Court in Reynolds and by the Fifth Circuit in Taylor.

Rodgers v. Commissioners Court of San Augustine

County, 483 F.Supp 779 (E.D.Tex. 1980) (J. Robert HM.

Parker), summarized the teaching of Taylor v. Monroe County

Board of Supervisors:

Where a Court approved reapportionment

1s implemented, the general rule is that

the Plaintiffs do not have a right to an

immediate election under the newly drawn

precincts; similarly, the present County

Commissioners are not entitled to complete

their terms as a matter of right. Rather,

the Court is to weigh several factors where

the Plaintiffs move for a special election

under the new apportionment scheme, including

the extent of malapportionment existing under

the invalid boundary lines: tl he expense,

Co

d

rx

S|

sill

time, and effort that would be expended by

the County Commissioners Court if a special

election were held; the number of citizens

that will be deprived of an opportunity to

he Court declines to shorten the

ounty Commissioner's term; and

vote if t

present C

the basic equities of the respective posi-

tions of the parties.

483 F.Supp at 781, citing Taylor and Dollinge: Jefferson sm em —

County Commissioners Court, 335 F.S\ r 40, 3 (E.D.Tex.

1971).

In the weighing of equities, special elections

11 should more readily be ordered "in the context of racial

inequalities or hinderances." Graves v. Barnes, 343 F.Supp.

704, 736 { 1972}, aff'd in part sub nom.White v,.

Regester, 4] S 755 (1973), citing Connor v. Johnson,

Sims v, Amos, 336 F.Supp 924

(M.D. Ala. 1972), aff'd 409 u.s. ¢ (1972). In Sims v.

Amos, the three-judge court acknowledged its power to order

mid-term elections, 336 F.Supp. at 940 (see cases cited),

but declined to do SO, because In the facts of that

particular case, it would have ‘place[d] too great a burden

on the State's election officials." There are no similar

mechanical difficulties preventing the conduct

elections for the City of Mobile.

Undersigned counsel has been unable to}

Cases where the federal appellate courts have approved

postponement of a remedy for unconstitutional elections

much as three years beyond the judgment of

unconstitutionality. In Ely v. Kahr, 403 Y4.5. 108 (1971),

the Supreme Court affirmed the district court's decision to

allow 1970 legislative elections go forward in Arizona under

the old, malapportioned plan, but the Court instructed the

trial court to "make very sure that the 1972 elections are

held under a constitutionally adequate apportionment plan.”

403 U.S. at 114-15. More recently, the three-judge court in

Cosner v. Dalton, 522 F.Supp 350, 364 (E.D.Va. 1981),

permitted impending elections to go ahead as scheduled in

1981 under the following conditions:

Because Virginia's citizens are

entitled to vote as soon as possible

for their representatives under a

constitutional apportionment plan, we

will 1imit the terms of members

of the House of Delegates elected in

1981 to one year. We also will direct

the state election officials to conduct

a new election in 1982 for the House of

Delegates under the General Assembly's

new Act or our own plan.

522 F.Supp at 364 (emphasis added).

For all of the aforegoing reasons, Plaintiffs pray

that the Court will grant their Petition for a permanent

10

injunction.

. . ry ~

Respectfully submitted this “/ day of

1982.

BLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN,

405 Van Antwerp Bidg.

P. 0. Box 1051

Mobile, Alabama 36633

! ‘4 / £7 /)

BY XY IL hold 7A fA

Y3 2

Lhe »

J

IFA £5 U. BLACKSHER

\/ LARRY T. MENEFEE

EDWARD STILL

Reeves & Still

Suite 400, Commerce Center

2027 First Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 3520

JACK En sanERS

NAPOLEON B. ILLIAMS

Legal tose Fund

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

wv New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I do hereby certify that on May 7, 1982 a copy

11

3

foregoing document was served upon counsel of record:

Charles B. Arendall, Jr., Esquire, William C. Tidwell,

~

[+] Jedsole, Greaves & Johnston, P.

Esquire, Hand, Arendall,

Box 123, Mobile, Alabama 36601, Roderick P. Stout, Esquire,

City Attorney, City Hall, Mobile, Alabama 36602, Charles

Rhyne, Esquire, and William S. Rhyne, Esquire, 1000

Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 800, Washington, D.C. 2003 J ’

Paul F. Hancock, Esquire and J. Gerald Hebert, Esquire,

Civil Rights Division, Department of Justice, 10th and

Constitution Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20530. b ] y DY

iil,

0.

S.

depositing same in the United States mail, postage prepaid or

by hand.

A TE : /

7 [Ly / ) If

JV AV ¢ fig Ul A

ATTORNEY FOR PLATHTIFF T -

\

12

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

SOUTHERN DIVISION

WILEY L. BOLDEN, ef al., )

Plaintiffs, )

VS. ) CIVIL ACTION NO. 75-297-P

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, )

et al.,

Defendants. )

PLAINTIFFS' PETITION FOR A PERMANENT INJUNCTION

Plaintiffs Wiley L. Bolden, et al., through their

undersigned counsel, would show unto the Court as follows:

1. On April 15, 1982, this Court entered its

Opinion and Order making findings of fact and conclusions of

law as directed by the Court of Appeals, which vacated and

remanded this Court's earlier judgment of October 22. 1976.

In said Opinion and Order the Court held that the present

at-large plan for electing Mobile City Commissioners violates

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the fourteenth

and fifteenth amendments. It withheld entry of a remedial

order to provide the State an opportunity to enact a

constitutional election plan "reasonably prior to a city

election in August, 1983." The Court further announced that

it will develop and implement its own remedial plan, upon

motion of one of the parties or on its own motion, if it

appears that the legislature will not respond in time for the

1983 elections.

2. On April 20, 1982, Plaintiffs filed a motion

pursuant to Rule 59, Fed.R.Civ.P., asking the Court to

1

: |

certify pursuant to Rule 54(b) that its ruling on the

unconstitutionality and unlawfulness of the at-large system

was final and appealable, notwithstanding the pendency of

other claims in this action.

3. On April 26, 1982, the Defendants filed a

response to Plaintiffs' Rule 59 motion, urging that said

motion be denied and that this Court not enter a final and

appealable judgment until it becomes necessary for it to

enter a remedial injunction.

4. A hearing on Plaintiffs' Rule 59 motion was

held on April 26, 1982, at which time this Court gave both

sides additional time to respond to the aforesaid arguments

of the Defendants regarding this Court's authority to issue

an appealable order. At this hearing, undersigned counsel

understood the Court to repudiate our interpretation of the

April 15 Opinion and Order to the effect that the Court would

require mid-term city elections in August 1983. We

understood the Court to say that it had no intention of

cutting short the terms of the present city commissioners,

which do not expire until 1985, that in 1983 the Court will

only specify the type of election plan it will order, and

that the Court will likely stay such order pending the final

outcome of an expected appeal by the .Defendants. The Court

further indicated, at least tentatively, that it will not be

inclined to issue an appealable order on the merits until it

issues a remedial order in 1983.

5. To delay relief by way of single-member

district elections until August 1985 would be inequitable and

unjust to the class of black citizens whose fundamental

constitutional and statutory voting rights are presently

being denied. It would also work an intolerable inversion of

constitutional priorities. Deference to the State

Legislature in the remedial process must be properly balanced

against the equally important requirement of providing a

speedy remedy for constitutional wrongs.

6. Plaintiffs and the class they represent are

entitled to mid-term elections in August 1983, whether those

elections are held pursuant to a plan adopted by the

Legislature or one adopted by the Court. Plaintiffs filed

this lawsuit on June 9, 1975. A judgment that the at-large

city election system was unconstitutional was originally

entered on October 22, 1976. That judgment has now survived

a lengthy appeal, a fundamental change in the standard of

proof announced by the Supreme Court, and lengthy remand

proceedings. This Court's Opinion and Order of April 15,

1982, reaffirms that black citizens were entitled to

single-member district elections in 1977.

7. The provision of speedy relief from the

existing unconstitutional and unlawful election system is an

urgent matter. According to principles established by the

Supreme Court, this Court should withhold that remedy only

long enough to give the Legislature a reasonable opportunity

to adopt its own constitutional election plan. There will

Tikely be at least one Special Session of the Legislature in

1982.

8. The concern announced by this Court for

preserving the full terms in office of the incumbent city

commissioners, in light of the history of this case and in

light of the fundamental importance of the constitutional

wrong, is not an adequate justification for postponing

remedial elections to August 1985. Plaintiffs did not oppose

the conduct of at-large elections in 1981 pending the outcome

of trial proceedings on remand because they shared the belief

that the citizens of Mobile should not be unduly denied the

opportunity to vote on their city officials. Plaintiffs were

not informed by the Court at that time that the Court would

be inclined to allow the at-large elected officials to serve

out their full terms. If Plaintiffs had known that they were

faced with a choice of opposing elections in 1981 or

postponing the opportunity for remedial elections until 1985,

they would have reluctantly sought a stay of the 1981

elections.

9. There is another important reason why this

Court should enter a permanent injunction immediately against

the existing at-large system. The Supreme Court has said

repeatedly that, when State statutes are declared

unconstitutional, it is critically important that the

provisions of Rule 65(d), Fed.R.Civ.P., be fully complied

with:

Every order granting an injunction

and every restraining order shall set

forth the reasons for its issuance;

shall be specific in terms; shall

describe in reasonable detail, and

not by reference to the complaint

or other document, the act or acts

sought to be restrained

Without a permanent injunction specifying in what particulars

the present Mobile city form of government and its election

system are objectionable, the Defendants and the Alabama

Legislature will not be provided adequate notice of what

legislative response is constitutionally required. For

example, there has already been speculation whether the

necessary implication of this Court's April 15 Opinion is

that the entire commission form of government is

unconstitutional and unlawful. It has never been Plaintiffs’

contention that the commission form of government itself must

be changed in order to provide black citizens adequate

relief. Only the at-large election system needs to be

changed to single-member districts. The Court's expression

&

of concern on p. 60 of its Opinion that imposing

single-member districts on the commission form might cause

One person, one vote problems can be remedied simply by

enjoining that feature of the commission form of government

which requires or permits the commissioners to assign

themselves separate executive department head duties either

before or after their elections. These questions illustrate

the need for a specific permanent injunction to provide the

State a fair opportunity to produce an adequate remedy.

10. In addition, the permanent injunction should

specify that remedial elections must take place as soon as

practicable and in no event later than August 1983. This

would not only make it clear that Plaintiffs and the class of

black citizens would receive timely constitutional relief,

but it would provide the State with sufficiently specific

notice of when it must make a legislative response and would

provide the Legislature an opportunity to design 1982 or 1983

elections into the law.

11. In addition, the permanent injunction prayad

for herein should specify, by reference to Rule 54(b),

Fed.R.Civ.P., or otherwise that it is an appealable order in

order to provide a prompt opportunity for review of all

aspects of this Court's judgment by the Court of Appeals.

Plaintiffs submit that this Case was remanded by the Court of

Appeals with instructions for a prompt consideration of the

issues left open by the Supreme Court with the intention that

resolution of these issues by the trial court be promptly

reviewable on appeal.

WHEREFORE plaintiffs pray that the Court will

immediately enter a permanent injunction in the form

specified by Rule 65(d), Fed.R.Civ.P., restraining the

Defendants, their successors, officers, agents, attorneys,

employees, and those acting in concert with them or at their

direction, from:

(1) conducting any further elections of Mobile

City Commissioners on an at-large basis;

(2) assigning separate executive duties or

responsibilities to individual City Commissioners, either

prior to or following their election;

(3) failing to conduct new elections for the

government of the City of Mobile as soon as practicable

after the first special session of the Alabama Legislature in

1982, either utilizing a new method of election adopted by

the State and approved by this Court as a constitutionally

and legally adequate response to this Court's judgment or

electing new city commissioners under the present form of

government from three single-member districts.

Plaintiffs further pray that said injunction

contain provisions:

(4) that on its own motion or the motion of the

parties the Court will set a hearing at which the Court will

consider proposals for the boundaries of three single-member

commissioner districts, if after a reasonable time the Court

has not approved a lawful and constitutional remedy adopted

by the State; and

(5) retaining jurisdiction of this action for

subsequent consideration of the amount of attorneys' fees,

costs and expenses to which plaintiffs are entitled and to

insure full compliance with the orders and decrees of the

Court.

Plaintiffs further pray that the Court will

promptly consider this Petition for a permanent injunction

and, should it be inclined not to grant the relief requested

herein, that it promptly enter an order denying this Petition

in whole or in part, in order that Plaintiffs may promptly

appeal and seek the speedy relief to which they are

constitutionally and legally entitled.

Respectfully submitted this 7/ day of May, 1982.

BLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN, P.A.

405 Yan Antwerp Bldg.

P. 0. Box 1051

Mobile, Alabama 36633

EDWARD STILL

Reeves & Stil]

Suite 400, Commerce Center

2027 First Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

JACK GREENBERG

NAPOLEON B. WILLIAMS

Legal Defense.Fund

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I do hereby certify that on _/ day of May, 1982

a copy of the foregoing PLAINTIFFS' PETITION FOR A PERMANENT

INJUNCTION was served upon counsel of record: Charles B.

4 Arendall, Jr., Esquire, William C. Tidwell, }I1, Esquire,

Hand, Arendall, Bedsole, Greaves & Johnston, P. 0. Box 123,

Mobile, Alabama 36601, Roderick P. Stout, Esquire, City

Attorney, City Hall, Mobile, Alabama 36602, Charles S.

Rhyne, Esquire, and William S. Rhyne, Esquire, 1000

Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 800, Washington, D.C. 20036,

Paul F. Hancock, Esquire and J. Gerald Hebert, Esquire,

Civil Rights Division, Department of Jus tice, 10th and

Constitution Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20530, and

William Bradford Reynolds, Esquire, Assistant Attorney

General, Department of Justice, Washington, D.C. 20530, by

depositing same in the United States mail, postage prepaid or

by hand.

[dr iis

i nti asta: