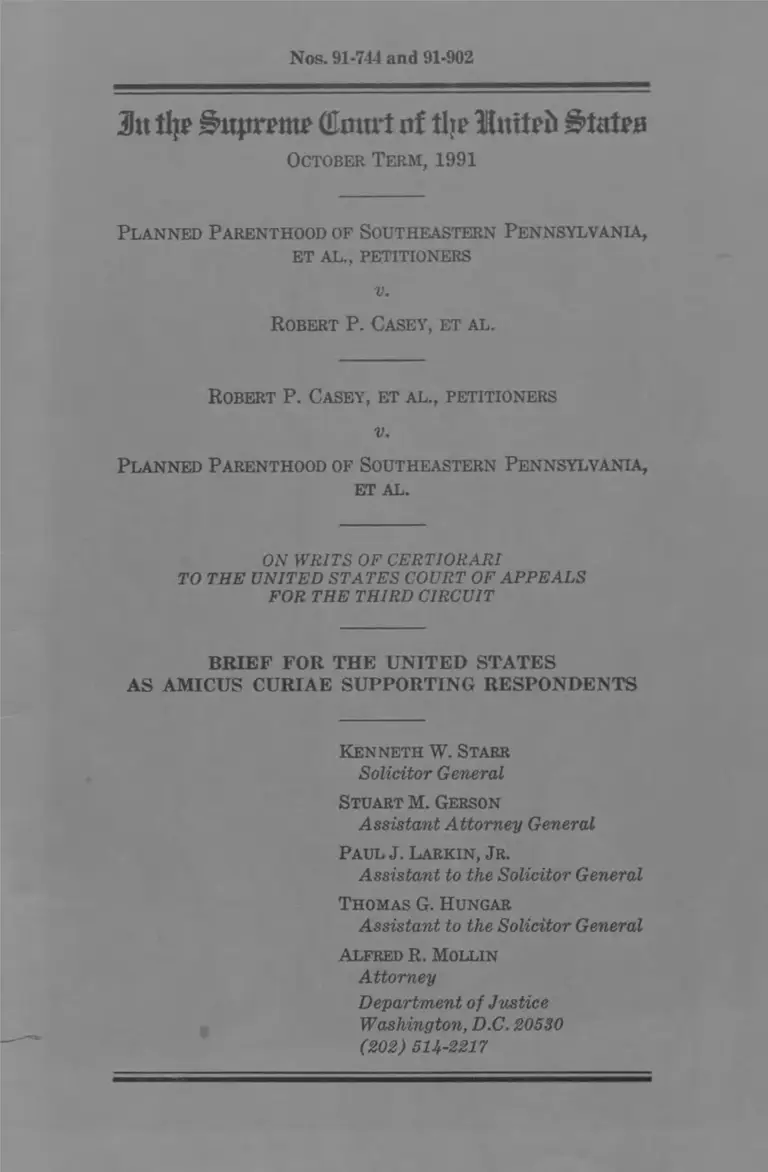

Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

April 30, 1992

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey Brief Amicus Curiae, 1992. 7badc268-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4c033486-101a-48b9-be45-85528bb4f121/planned-parenthood-of-southeastern-pennsylvania-v-casey-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

Nos. 91-744 and 91-902

3tt % j5>upr(Emtrt nf llu> llmtrh Slatro

October Term, 1991

Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania,

ET AL., PETITIONERS

V.

Robert P. Casey, et al.

Robert P. Casey, et al., petitioners

v.

Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania,

e t AL.

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

AS AMICUS CURIAE SUPPORTING RESPONDENTS

Ke n n e th W . Starr

Solicitor General

Stuart M. Gerson

Assistant Attorney General

P a u l J. L a r k in , Jr .

Assistant to the Solicitor General

T hom as G. H ungar

Assistant to the Solicitor General

A lfred R. Mollin

Attorney

Department of Justice

Washington, D.C. 20530

(202) 514-2217

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Did the court of appeals err in upholding the con

stitutionality of the following provisions of the Pennsyl

vania Abortion Control Act: (a) 18 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann.

§ 3203 (Purdon 1983 & Supp. 1991) (definition of med

ical emergency); (b) 18 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann. § 3205

(Purdon 1983 & Supp. 1991) (informed consent); (c)

18 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann. § 3206 (Purdon 1983 & Supp.

1991) (parental consent); (d) 18 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann.

§§ 3207 and 3214 (Purdon 1983 & Supp. 1991) reporting

requirements) ?

2. Did the court of appeals err in holding 18 Pa. Cons.

Stat. Ann. § 3209 (Purdon Supp. 1991) (spousal notice)

unconstitutional ?

( i )

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Interest of the United States__________________________ 1

Statement___________________________________________ 2

Summary o f argument_______ 4

Argument:

The Pennsylvania Abortion Control Act does not

violate the Constitution................................................ 5

I. Abortion regulations should be upheld if they

are reasonably designed to serve a legitimate

state interest............................................................. 6

A. Abortion regulations should be subject to

heightened scrutiny only if they implicate a

fundamental right ............................................ 6

B. The Pennsylvania Abortion Control Act does

not implicate a fundamental right under the

Due Process Clause....................................... 8

1. The Nation’s history and traditions do

not establish a fundamental right to

abortion......................................................... 9

2. The State has a compelling interest in

protecting the fetus throughout preg

nancy ................ 15

II. The Pennsylvania Abortion Control Act is rea

sonably designed to advance legitimate state

interests..................................................................... 19

Conclusion................................................ 29

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health,

462 U.S. 416 (1983)......... .........................3, 5,17, 20, 25

Bolger v. Youngs Drug Products Corp., 463 U.S.

60 (1983) ............................... ................................. 11

Bowen V. Kendrick, 487 U.S. 589 (1988)................. 18

Bowers v. Hardwick, 478 U.S. 186 (1986)............... 7, 8, 9

( i l l )

Burnett v. Coronado Oil & Gas Co., 285 U.S. 393

(1932)...................................................... - ............... 9

Burnham v. Superior Court, 495 U.S. 604 (1990).. 8

Califano v. Aznavorian, 439 U.S. 170 (1978)........ 7

Carey v. Population Servs. Int’l, 431 U.S. 678

(1977).............. .................................................... ... 15

Coker V. Georgia, 433 U.S. 584 (1977) .................... 14

Cox V. Wood, 247 U.S. 3 (1918)........... ............... — 14

Cruzan V. Director, 110 S. Ct. 2841 (1990)............ 8, 20

DeShaney V. Winnebago County Dep’t of Social

Services, 489 U.S. 189 (1989)..................... 14

Doe V. Doe, 365 Mass. 556, 314 N.E.2d 128

(1974) ........................................................................ 23

Employment Division, Dep’t of Human Resources

V. Smith, 494 U.S. 872 (1990) .................... 18

Ferguson V. Skrupa, 372 U.S. 726 (1963) .............. 7

Geduldig v. Aiello, 417 U.S. 484 (1974) .................. 26

Griffin v. United States, 112 S. Ct. 466 (1991) ....... 8

Griswold V. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965)......... 6-7, 8

Haig v. Agee, 453 U.S. 280 (1981).......................... 15

Harris V. McRae, 448 U.S. 297 (1980).... 13,18, 20, 22, 26

Hodgson v. Minnesota, 110 S. Ct. 2926 (1990) .... 1, 5, 22,

23, 25

Illinois v. Gates, 462 U.S. 213 (1983)....................... 16

Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11 (1905).... 14, 27

Jehovah’s Witnesses V. King County Hosp., 390

U.S. 598 (1968), aff’g 278 F. Supp. 488 (W.D.

Wash. 1967).............................................................. 18

Judgment of Feb. 25, 1975, 39 BVerfGE 1, re

printed in 9 J. Marshall J. Prac. & Proc. 605

(1975) ........................................................................ 12

Kirchberg V. Feenstra, 450 U.S. 455 (1981) .......... 26

Labine V. Vincent, 401 U.S. 532 (1971).................. 24, 25

Lee v. Washington, 390 U.S. 333 (1968)................. 15

Lehr v. Robertson, 463 U.S. 248 (1983).................. 24

Lindsey v. Normet, 405 U.S. 56 (1972)................... 14

Maher V. Roe, 432 U.S. 464 (1977) .......................... 21, 26

Marks V. United States, 430 U.S. 188 (1977)........ 3

McKeiver V. Pennsylvania, 403 U.S. 528 (1971).... 8

Metro Broadcasting, Inc. V. FCC, 110 S. Ct. 2997

(1990)........................................................................ 5

TV

Cases— Continued: Page

Metropolitan Life Ins. Co. v. Ward, 470 U.S. 869

(1985) .................................................................... 15

Michael H. v. Gerald D., 491 U.S. 110 (1989)....7-8, 9,12,

13, 24

Michael M. v. Superior Court, 450 U.S. 464

(1981).................................................................... 14

Minnesota v. Probate Court, 309 U.S. 270 (1940).. 27

Miranda V. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966) ............. 16

Moore v. East Cleveland, 431 U.S. 494 (1977)....... 6, 7, 8

Morgentaler v. Regina, 1 S.C.R. 30, 44 D.L.R. 4th

385 (1988) ........................................................... 12

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697 (1931) .............. 15-16

Ohio v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health,

110 S. Ct. 2972 (1990) ........................................ 19, 24

Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U.S. 319 (1937) ........... 7

Patterson v. New York, 432 U.S. 197 (1977)........ 8

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510 (1925).. 6

Planned Parenthood v. Danforth, 428 U.S. 52

(1976) ................20, 24, 28

Planned Parenthood Ass’n v. Ashcroft, 462 U.S.

476 (1983) ........................................................... 28

Poe V. Gerstein, 517 F.2d 787 (5th Cir. 1975),

aff’d, 428 U.S. 901 (1976) ................................... 23

Poe V. UUman, 367 U.S. 497 (1961) ....................... 16

Prince V. Massachusetts, 321 U.S. 158 (1944)...... 18

Reynolds v. United States, 98 U.S. 145 (1879).... 18

Riley v. National Fed’n of the Blind, 487 U.S. 781

(1988) ............. 21

Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973) ............................passim

Rust v. Sullivan, 111 S. Ct. 1759 (1991) ............... 8

Schad v. Arizona, 111 S. Ct. 2491 (1991) ............... 8

Scheinberg v. Smith, 659 F.2d 476 (5th Cir.

1981) ...................................................................... 25

Schloendorff v. Society of the New York Hosp.,

211 N.Y. 125, 105 N.E. 92 (1914) ...................... 13

Schmerber v. California, 384 U.S. 757 (1966) ....... 13-14

Selective Draft Law Cases, 245 U.S. 366 (1918).... 14

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 (1942)............ 24

Slater v. Baker, 2 Wils. 359, 95 Eng. 860 (K.B.

1767) ...................................................................... 20

Snyder v. Massachusetts, 291 U.S. 97 (1934)......... 8

V

Cases— Continued: Page

Sosna v. Iowa, 419 U.S. 393 (1975)......................... 25

Stanford v. Kentucky, 492 U.S. 361 (1989) ......... 8,11,12

Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetricians

& Gynecologists, 476 U.S. 747 (1986).....3, 5,13,17,18,

20, 21, 27, 28

United States v. Kozminski, 487 U.S. 931 (1988).. 19

United States V. O’Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968)...... 11

United States V. Salerno, 481 U.S. 739 (1987)..... 19

United States Dep’t of Agric. v. Moreno, 413 U.S.

528 (1973) ............................................................... 15

Vance V. Bradley, 440 U.S. 93 (1979) ...................... 21

Virginia V. American Booksellers Ass’n, 484 U.S.

383 (1988) ......................... 27

Vitek v. Jones, 445 U.S. 480 (1980) ........................ 13

Washington v. Harper, 494 U.S. 210 (1990)........... 13

Webster v. Reproductive Health Care Servs., 492

U.S. 490 (1989).......................1, 5, 6, 9,14,15,17,19, 26

Williamson v. Lee Optical Co., 348 U.S. 483

(1955)........................................................................ 7

Winston v. Lee, 470 U.S. 753 (1985)......................... 14

Wyman v. James, 400 U.S. 309 (1971) .................. 28

Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel, 471

U.S. 626 (1985) ......................... 21

Zobel v. Williams, 457 U.S. 55 (1982) .................... 15

Constitution and statutes:

U.S. Const.:

Amend. 1................................................................ 21

Establishment Clause.................................. 18

Free Exercise Clause................................... 18,19

Amend. I V ............................................................. 14

Amend. V (Due Process Clause) ...............5, 6, 8,14-15

Amend. V I II .......................................................... 8

Amend. X .............................................................. 6

Amend. X I I I .............................. 19

Amend. X IV .......................................................... 4,10

Equal Protection Clause.............................. 26

Act of Sept. 30, 1976, Pub. L. No. 94-439, §209,

90 Stat. 1434 (Hyde Amendment)....................... 2,18

VI

Cases— Continued: Page

Statutes— Continued: Page

Public Health Service Act (Adolescent Family

Life Act of 1981), 42 U.S.C. 300z et seq.............. 2,18

Abortion Control Act, 18 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann.

(Purdon) :

§§ 3201-3220 (1983 & Supp. 1991).................... 2

§ 3202(a) (1983)................................................. 11

§ 3202(b) (1983) ................................................ 2

§ 3202(b) (4) (1983).............................. 11

§ 3203 (Supp. 1991) ............................................ 26

§ 3203(a) (1983).................................................. 2

§ 3204(c) (Supp. 1991) ...................................... 2,18

§ 3205 (a) (1) (Supp. 1991)................................ 20

§ 3205(a) (2) (1983 & Supp. 1991) ................... 20

§ 3206 (a) (1983 & Supp. 1991).......................... 22

§ 3206(b) (1983) ...... 22

§ 3206 ( c ) ( 1983) ................................................. 22

§ 3206(d) (1983)................................................. 22

§ 3206 (e) - (h) (1983 & Supp. 1991) .................. 22

§ 3207 (1983 & Supp. 1991) ................................ 27

§ 3209 (a) (Supp. 1991)....................................... 23, 25

§ 3209(b) (Supp.1991) ..................................... 23

§ 3211 (a) (1983 & Supp. 1991)......................... 2

§ 3214 (Supp. 1991) ............................................ 27-28

§3214 (a) (Supp. 1991) ...................................... 27,28

Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 18-6-101 (1) (West 1986) .... 23

Lord Ellenborough’s Act, 1803, 43 Geo. 3, ch. 58...... 10

Miscellaneous:

A. Bickel, The Morality of Consent (1975) ............... 9

Bopp, Will There Be a Constitutional Right to

Abortion After the Reconsideration of Roe v.

Wade?, 15 J. Contemp. L. 131 (1989) ................ 19

Burt, The Constitution of the Family, 1979 Sup.

Ct. Rev. 329 ................... 9

A. Cox, The Court and the Constitution (1987)..... 9

J. Ely, Democracy and Distrust—A Theory of

Judicial Review (1980)......................................... 9

Ely, The Wages of Crying Wolf: A Comment on

Roe v. Wade, 82 Yale L.J. 920 (1973) ................ 16-17

Epstein, Substantive Due Process by Any Other

Name: The Abortion Cases, 1973 Sup. Ct. Rev.

159.............................................................................. 9,11

VII

Miscellaneous— Continued: Page

M. Glendon, Abortion and Divorce in Western

Law (1987) .......................................................... 12

Gunther, Some Reflections on the Judicial Role:

Distinctions, Roots, and Prospects, 1979 Wash.

U.L.Q. 817.............................................................. 9

3 F. Harper, F. James, Jr. & 0. Gray, The Law of

Torts (2d ed. 1986)............................................... 13, 20

J. Mohr, Abortion in America (1978)............... 10,11,17

Siegel, Reasoning From the Body: A Historical

Perspective on Abortion Regulation and Ques

tions of Equal Protection, 44 Stan. L. Rev. 261

(1992)....................................................... ........... 10,11

L. Tribe, American Constitutional Law (2d ed.

1988)................ 17

Wellington, Common Law Rules and Constitutional

Double Standards: Some Notes on Adjudica

tion, 83 Yale L.J. 221 (1973) . 9

3n lip ^lpirrmr dmtrt nf lip lltttlri) fla irs

October T e r m , 1991

No. 91-744

P l a n n e d P aren th o o d of So u th e a ste r n P e n n s y l v a n ia ,

ET AL., PETITIONERS,

V.

R obert P. Ca s e y , e t a l .

No. 91-902

R obert P. Ca s e y , e t a l ., pe titio n e r s

v.

P l a n n e d P a r e n th o o d of So u th e a ste r n P e n n s y l v a n ia ,

e t AL.

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

AS AMICUS CURIAE SUPPORTING RESPONDENTS

INTEREST OF THE UNITED STATES

This Court granted review in order to resolve several

issues regarding the constitutionality of the 1988 and

1989 amendments to the Pennsylvania Abortion Control

Act. In Webster v. Reproductive Health Care Servs., 492

U.S. 490 (1989), and Hodgson v. Minnesota, 110 S. Ct.

2926 (1990), the United States filed briefs as an amicus

( 1 )

2

curiae in which we argued that Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S.

113 (1973), was wrongly decided and should be over

ruled. Moreover, Congress has enacted laws affecting

abortion.1 The United States therefore has a substantial

interest in the outcome of this case.

STATEMENT

1. In 1988 and 1989, Pennsylvania amended its Abor

tion Control Act, 18 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann. §■§ 3201-3220

(Purdon 1983 & Supp. 1991). The purpose of the Act

is to “protect hereby the life and health of the woman

subject to abortion” and “ the child subject to abortion,”

to “ foster the development of standards of professional

conduct in a critical area of medical practice,” to “ pro

vide for development of statistical data,” and to “ protect

the right of the minor woman voluntarily to decide to

submit to abortion or to carry her child to term.” Id.

§ 3203(a) (Purdon 1983); see also id. § 3202(b) (Pur

don 1983) (legislative findings). The Act outlaws post

viability abortions and pre-viability abortions based on

the fetus’s sex. Id. § 3204(c) (Purdon Supp. 1991),

§ 3211(a) (Purdon 1983 & Supp. 1991). Otherwise, the

Act regulates but does not ban abortion. Five such reg

ulations are at issue here: the informed consent, in

formed parental consent, and spousal notification re

quirements; the definition of a medical emergency, which

is an exception to the first three provisions; and certain

reporting requirements.

2. Petitioners, five abortion clinics and one physician,

brought this action three days before the 1988 amend

ments would have taken effect, seeking to have those

amendments (and later the 1989 amendments) declared

unconstitutional. The district court entered preliminary

injunctions against the 1988 and 1989 amendments. After

1 E.g., Act of Sept. 30, 1976, Pub. L. No. 94-439, § 209, 90 Stat.

1434 (the Hyde Amendment); Public Health Service Act (the

Adolescent Family Life Act of 1981), 42 U.S.C. 300z et seq.

3

a bench trial, relying on Roe v. Wade, Akron v. Akron

Center for Reproductive Health, 462 U.S. 416 (1983)

(Akron I), and Thornburgh v. American College of Ob

stetricians & Gynecologists, 476 U.S. 747 (1986), the

court held unconstitutional the five provisions noted above

and permanently enjoined their enforcement. 91-744 Pet.

App. (Pet. App.) 104a-287a.

3. The court of appeals, by a divided vote, affirmed

in part and reversed in part. Pet. App. la-103a. At the

outset, the court addressed the correct standard of re

view for abortion regulations. Relying on Marks v.

United States, 430 U.S. 188 (1977), the court concluded

that when this Court issues a judgment without a ma

jority opinion, “ the holding of the Court may be viewed

as that position taken by those members who concurred

in the judgment on the narrowest grounds.” Pet. App.

20a, 15a-24a. Applying that approach to this Court’s

decisions, the court held that the strict scrutiny standard

of Roe, Akron I, and Thornburgh was no longer applica

ble after Webster and Hodgson. Instead, the court de

termined, the undue burden standard adopted by Justice

O’Connor now constituted the governing rule. Pet. App.

24a-30a.

The Third Circuit then applied the undue burden stand

ard to the Pennsylvania Act. The court unanimously held

that the definition of medical emergency included condi

tions posing a significant risk of death or serious injury

to a woman, and that the informed consent, informed

parental consent, and reporting requirements did not un

duly burden a woman’s right to an abortion. Pet. App.

33a-60a, 75a-85a. By contrast, a majority of the court

held that the spousal notification provision was unduly

burdensome and that the State lacked a compelling in

terest in ensuring such notification. Pet. App. 60a-74a.

Judge Alito dissented from that portion of the majority’s

decision. Pet. App. 86a-103a.

4

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I. Under this Court’s decisions, a liberty interest is

“ fundamental” and thus deserves heightened protection

only if our Nation’s history and traditions have protected

that interest from state restriction. Those sources do not

establish a fundamental right to abortion. Abortion after

quickening was a crime at common law; the first English

abortion statute outlawed abortions throughout pregnancy;

state laws condemning or restricting abortion were com

mon when the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified; and

21 of those laws were still in existence in 1973. Thus,

strict scrutiny is inappropriate. The correct standard of

review is the one endorsed by the Webster plurality. In

any event, a State has a compelling interest in protecting

fetal life throughout pregnancy.

II. The challenged provisions of the Pennsylvania Act

are reasonably designed to advance legitimate state in

terests. The informed consent and waiting period re

quirements ensure that a woman knows the relevant facts

and can reflect on them before making a final decision.

The informed parental consent requirement enables par

ents to make important decisions affecting their child.

The spousal notification requirement can help protect

the life of a fetus, the integrity of the family unit, and

the husband’s interests in procreation within marriage

and the potential life of his unborn child. The definition

of medical emergency includes those conditions that put

a woman’s life or health at significant risk. The report

ing rules help in enforcing the ban on abortion of viable

fetuses (except to protect a mother’s life or health), in

advancing medical knowledge, and in informing the pub

lic about the use of state tax dollars.

5

ARGUMENT

THE PENNSYLVANIA ABORTION CONTROL ACT

DOES NOT VIOLATE THE CONSTITUTION

In Roe v. Wade, a divided Court held that a woman

has a fundamental right to an abortion; the Court also

adopted a complex trimester framework to determine

whether and how a State may regulate abortion. Since

then, a majority of the Members of this Court has ex

pressed the view that Roe and succeeding cases should be

limited or overruled. See Webster, 492 U.S. at 517-521

(plurality opinion of Rehnquist, C.J., joined by White &

Kennedy, J J .) ; id. at 532 (opinion of Scalia, J . ) ; Hodg

son, 110 S. Ct. at 2984 (Scalia, J., concurring); Thorn

burgh, 476 U.S. at 786-797 (White, J., dissenting,

joined by Rehnquist, J . ) ; Akron I, 462 U.S. at 453-459

(O’Connor, J., dissenting, joined by White & Rehnquist,

JJ.). At the same time, none of the opinions in recent

abortion cases commanded a majority. The result is that

considerable uncertainty now prevails with respect to

the proper standard of review applicable when legisla

tion affecting abortion is challenged under the Due Proc

ess Clause. The Third Circuit’s opinion in this case

illustrates this uncertainty.

Ascertaining the correct standard of review is not only

the threshold issue, but also a critical one. Here, as else

where, the question of the correct standard that the courts

should employ is not merely “ a lawyer’s quibble over

words,” but “ establishes whether and when the Court and

Constitution allow the Government to” regulate a woman’s

abortion decision. Metro Broadcasting, lux. v. FCC, 110

S. Ct. 2997, 3033 (1990) (O’Connor, J., dissenting). This

issue is one in need of clarification if the legislatures,

lower courts, and litigants are to have guidance in this

difficult area. We believe that the correct standard was

the one articulated by the Webster plurality: Is a regula

tion reasonably designed to serve a legitimate state inter-

6

est? That standard should be applied to the questions in

this case and to abortion regulations generally.2

I. ABORTION REGULATIONS SHOULD BE UPHELD

IF THEY ARE REASONABLY DESIGNED TO

SERVE A LEGITIMATE STATE INTEREST

A. Abortion Regulations Should Be Subject To

Heightened Scrutiny Only If They Implicate A

Fundamental Right

The ultimate source for constitutional rights is the text

of the Constitution. That text, of course, is silent with

respect to abortion; the Constitution leaves this matter to

the States, since only the States possess a general, regu

latory police power. See Roe, 410 U.S. at 177 (Rehnquist,

J., dissenting) ( “ the drafters did not intend to have the

Fourteenth Amendment withdraw from the States the

power to legislate with respect to this matter” ) ; U.S.

Const. Amend. X. The “ right to an abortion” was ju

dicially recognized in Roe as “ derived from the Due Proc

ess Clause,” Webster, 492 U.S. at 521 (plurality opinion) ;

Roe, 410 U.S. at 153. By its terms, however, the Due

Process Clause seeks to ensure that the government af

fords a person the process she is due before it attempts

to deprive her of life, liberty, or property. The text of

the Clause therefore focuses on procedure, not substance.

This Court’s decisions nevertheless hold that the Clause

provides a measure of substantive protection to certain

liberty interests. See, e.g., Moore v. East Cleveland, 431

U.S. 494 (1977); Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S.

510 (1925); Griswold V. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479, 501

2 Petitioners note, Pet. Br. 36-37, that we urged this Court to

adopt an “ undue burden” analysis in Akron /, but criticized and

abandoned that standard in Webster and Hodgson. We adhere to

our views as expressed in the latter two cases. In our view, the

undue burden standard begs the question at issue (namely, whether

there is a fundamental right to abortion) and does not provide a

meaningful guide for assessing the weight of the competing

interests.

7

(1965) (Harlan, J., concurring in the judgment). At

the same time, the Court has been cautious in identifying

such rights, recognizing that once the courts venture be

yond the “ core textual meaning” of “ liberty” as freedom

from bodily restraint, the imputation of substance to that

concept is a “ treacherous” undertaking. Michael H. v.

Gerald D., 491 U.S. 110, 121 (1989) (plurality opinion)

(citation omitted). Accordingly, the Court has recognized

that it “ is most vulnerable and comes nearest to illegiti

macy when it deals with judge-made constitutional law

having little or no cognizable roots in the language or

design of the Constitution.” Bowers v. Hardunck, 478

U.S. 186, 194 (1986).

The general standard of review in assessing a sub

stantive due process claim is highly deferential to legis

lative judgments. As a rule, a state or federal law that

trenches on an individual’s liberty interest will be upheld

as long as it is rationally related to a legitimate govern

mental interest. See, e.g., Califano v. Aznavorian, 439

U.S. 170, 176-178 (1978); Ferguson V. Skrupa, 372 U.S.

726 (1963); Williamson v. Lee Optical Co., 348 U.S. 483

(1955). In some sensitive areas, however, the Court has

gone further and held that certain liberty interests rise

to the level of “ fundamental rights” and are subject to

more exacting scrutiny. Michael H., 491 U.S. at 122

(plurality opinion). Where that is the case, the State

may restrict such a liberty interest only through means

that are narrowly tailored to serve a compelling state

interest. Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. at 155-156 (collecting

cases). Accordingly, the applicable standard of review in

substantive due process cases is principally a function of

the methodology used for identifying what rights are

“ fundamental.”

This Court has held that a liberty interest will be

deemed fundamental if it is “ implicit in the concept of

ordered liberty,” Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U.S. 319,

325 (1937), is “ deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and

tradition,” Moore, 431 U.S. at 503 (plurality opinion),

or is “ so rooted in the traditions and conscience of our

people as to be ranked as fundamental,” Michael H., 491

8

U.S. at 122 (plurality opinion) (quoting Snyder V. Mass

achusetts, 291 U.S. 97, 105 (1934)). See Bowers, 478

U.S. at 192-194. The precise formulation may vary, but

the governing methodology rests on the Nation’s history

and traditions. E.g., Burnham v. Superior Court, 495

U.S. 604, 608-619 (1990) (plurality opinion); Michael

H., 491 U.S. at 122-130 (plurality opinion); Bowers, 478

U.S. at 192-194; Moore, 431 U.S. at 504 n.12 (plurality

opinion); Griswold, 381 U.S. at 501 (Harlan, J., concur

ring in the judgment). See Cruzan v. Director, 110 S. Ct.

2841, 2846-2851 & n.7 (1990).3 By so limiting funda

mental rights, the Court has sought, in the words of the

Michael H. plurality, to “ prevent future generations from

lightly casting aside important traditional values,” while

assuring that the Due Process Clause does not become a

license “ to invent new ones.” 491 U.S. at 122 n.2. See

Moore, 431 U.S. at 504 n.12 (plurality opinion).

B. The Pennsylvania Abortion Control Act Does Not

Implicate A Fundamental Right Under The Due

Process Clause

Petitioners’ principal submission is that the Court

should reaffirm the fundamental right to abortion identi

fied in Roe. As we explained in our briefs in Akron I,

Thornburgh, Webster, Hodgson, and Rust V. Sullivan,

111 S. Ct. 1759 (1991), Roe v. Wade was wrongly de

cided and should be overruled. We strongly adhere to

that position in this case.4 But regardless of whether this

3 That approach is consistent with this Court’s procedural due

process and Eighth Amendment decisions. In those areas, too, this

Court has insisted that, at a minimum, history and tradition must

inform/ the otherwise broad and general constitutional text. See,

e.g., Griffin v. United States, 112 S. Ct. 466, 469-470 (1991) ;

Schad v. Arizona, 111 S. Ct. 2491, 2500-2503 (1991) (plurality

opinion) ; id. at 2505-2507 (opinion of Scalia, J.) ; Stanford V.

Kentucky, 492 U.S. 361, 368-370 (1989) ; Patterson V. New York,

432 U.S. 197, 202 (1977); McKeiver V. Pennsylvania, 403 U.S.

528,548 (1971) (plurality opinion).

4 As we explained in our Webster brief (at 9-10), stare decisis

considerations do not preclude reconsidering and overruling Roe.

9

case requires reconsideration of Roe’s actual holding, see

Webster, 492 U.S. at 521 (plurality opinion), the Court

should clarify the standard of review of abortion regula

tion and, in so doing, make clear that the liberty interest

recognized in Webster does not rise to the exceptional

level of a fundamental right.

1 . The Nation’s history and traditions do not estab

lish a fundamental right to abortion

In Webster, a plurality of the Court determined that

a woman’s interest in having an abortion is a form of

liberty protected by due process against arbitrary depri

vation by the State. 492 U.S. at 520. Under the tradi

tional means used by this Court to identify fundamental

rights, however, no credible foundation exists for the

claim that a woman enjoys a fundamental right to abor

tion.® That conclusion follows whether the inquiry is

framed broadly, in terms of privacy or reproductive

choice, or narrowly, in terms of abortion. Compare

Michael H., 491 U.S. at 127-128 n.6 (opinion of Scalia,

J .), with id. at 132 (O’Connor, J., concurring in part).

I f “ [n]either the length of time a majority has held its convictions

[n]or the passions with which it defends them can withdraw legi-

lation from this Court’s scrutiny,” Bowers, 478 U.S. at 210 (Black-

mun, J., dissenting), neither factor should immunize one of this

Court’s constitutional rulings from re-examination, because in

such cases “correction through legislative action is practically im

possible.” Burnett v. Coronado Oil & Gas Co., 285 U.S. 393, 407

(1932) (Brandeis, J., dissenting). 5 *

5 That judgment is shared by a broad spectrum of constitutional

scholars. See, e.g., A. Bickel, The Morality of Consent 27-29

(1975) ; Burt, The Constitution of the Family, 1979 Sup. Ct. Rev.

329, 371-373; A. Cox, The Court and the Constitution 322-338

(1987) ; J. Ely, Democracy and Distrust— A Theory of Judicial

Review 2-3, 247-248 n.52 (1980); Epstein, Substantive Due Process

by Any Other Name: The Abortion Cases, 1973 Sup. Ct. Rev. 159:

Gunther, Some Reflections on the Judicial Role: Distinctions,

Roots, and Prospects, 1979 Wash. U.L.Q. 817, 819; Wellington,

Common Law Rules and Constitutional Double Standards: Some

Notes on Adjudication, 83 Yale L.J. 221, 297-311 (1973).

10

To examine this proposition, we turn to explore the legal

history and traditions of the American people to discern

the basis and nature of any such right.

a. It is beyond dispute that abortion after “ quicken

ing” was an offense at common law.6 The first English

abortion law, Lord Ellenborough’s Act, 1803, 43 Geo. 3,

ch. 58, outlawed abortion throughout pregnancy; it dis

tinguished pre- from post-quickening abortions only to

fix the severity of punishment. Early in our history, this

Nation embraced the common law. In 1821, however,

States began to enact laws condemning or restricting

abortion. By the time the Fourteenth Amendment was

ratified, such legislation was commonplace; in 1868, at

least 28 of the then-37 States and 8 Territories had stat

utes banning or limiting abortion. The Reconstruction

Era witnessed “ the most important burst of anti-abortion

legislation in the nation’s history.” J. Mohr, Abortion in

America 200 (1978).7 By the turn of the century, after

“ the passage of unambiguous anti-abortion laws in most

of the states that had not already acted during the previ

ous twenty years,” the country had completed the transi

tion from a Nation that followed the common law rule

6 The historical materials are discussed in Roe, 410 U.S. at 132-

141; id. at 174-177 & nn.1-2 (Rehnquist, J., dissenting); J. Mohr,

Abortion in America (1978) ; Siegel, Reasoning From the Body:

A Historical Perspective on Abortion Regulation and Questions of

Equal Protection, 44 Stan. L. Rev. 261, 281-282 (1992) ; Amicus

Br. of the American Academy o f Medical Ethics; Amicus Br. of

Certain American State Legislators.

7 “ At least 40 anti-abortion statutes of various kinds were placed

on the state and territorial lawbooks during that period [between

1860 and 1880]; over 30 in the years from 1866 through 1877

alone. Some 13 jurisdictions formally outlawed abortion for the

first time, and at least 21 states revised their already existing

statutes on the subject. More significantly, most of the legislation

passed between 1860 and 1880 explicitly accepted the regulars’

[j.e., regular physicians’ ] assertions that the interruption of ges

tation at any point in a pregnancy should be a crime and that the

state itself should try actively to restrict the practice of abortion.”

J. Mohr, supra, at 200.

11

outlawing post-quickening abortion to “a nation where

abortion was legally and officially proscribed.” Id. at

226. “ Every state in the Union had an anti-abortion law

of some kind on its books by 1900 except Kentucky, where

the state courts outlawed the practice anyway.” Id. at

229-230. With minor refinements and adjustments, those

statutes, which reflected “ a basic legislative consensus,”

remained unchanged until the 1960’s. Id. at 229. And 21

of those laws were in effect in 1973 when Roe was de

cided, even after a decade of efforts at liberalization.8

In view of this historical record, it cannot persuasively

be argued that the interest in having an abortion is so

deeply rooted in our history as to be deemed “ fundamen

tal.” The record in favor of the right to an abortion is

no stronger than the record in Michael H., where the

court found no fundamental right to visitation privileges

by adulterous fathers, or in Bowers, where the Court

found no fundamental right to engage in homosexual

sodomy. Cf. Stanford v. Kentucky, 492 U.S. 361, 370-373

(1989) (no consensus against execution of 16-year-olds

when a majority of the States with capital punishment

8 Amici 250 Historians contend that laws banning abortion were

originally adopted for various ignoble reasons, not to protect life

in the womb. 250 Historians Br. 15-26. That claim is overstated,

J. Mohr, supra, 35-36, 165, 200; Siegel, 44 Stan. L. Rev. at 282,

but it is irrelevant in any event. “ It is a familiar principle of

constitutional law that this Court will not strike down an other

wise constitutional statute on the basis of an alleged illicit legisla

tive motive,” United States V. O’Brien, 391 U.S. 367, 383 (1968),

and that “ the insufficiency of the original motivation does not di

minish other interests that the restriction may now serve,” Bolger

V. Youngs Drug Products Corp., 463 U.S. 60, 71 (1983); Epstein,

1973 Sup. Ct. Rev. at 168 n.34. Pennsylvania “ places a supreme

value upon protecting human life,” including prenatal life, 18 Pa.

Cons. Stat. Ann. §3202 (b )(4 ) (Purdon 1983), and the purpose

of this Act is to “protect hereby the life and health o f the woman

subject to abortion” and “ the child subject to abortion,” id.

§ 3202(a) (Purdon 1983). Just as the widespread use of controlled

substances does not render the drug laws unconstitutional, so, too,

the prevalance of illegal abortions does not undermine laws outlaw

ing or restricting abortion.

12

allows them to be executed). In short, this Nation’s his

tory rebuts any claim that the right to obtain an abortion

is fundamental, since that history does not “exclude * * *

a societal tradition of enacting laws denying that inter

est.” Michael H., 491 U.S. at 122 n.2 (opinion of Scalia,

J., joined by Rehnquist, C.J., O’Connor & Kennedy, JJ.).°

0 The prevalence of bans or restrictions on abortion prior to

Roe was “not merely an historical accident.” Stanford, 492 U.S.

at 369 n.l (citation omitted). After studying the abortion laws of

20 Western countries, a leading comparative law scholar reported

that “ we have less regulation o f abortion in the interest o f the

fetus than any other Western nation,” and “to a greater extent

than in any other country, our courts have shut down the legis

lative process of bargaining, education, and persuasion on the

abortion issue.” M. Glendon, Abortion and Divorce in Western

Law 2 (1987). Two of those nations (Belgium and Ireland) have

blanket prohibitions against abortion in their criminal law, sub

ject only to the defense of necessity. Four countries (Canada,

Portugal, Spain, and Switzerland) allow abortion only early in

pregnancy and only in restricted instances, such as if there is a

serious danger to the pregnant woman’s health, a likelihood of

serious disease or defect in the fetus, or the pregnancy resulted

from rape or incest. Eight countries (Great Britain, Finland,

France, West Germany, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Neth

erlands) permit abortion in early pregnancy in a wider variety of

circumstances that pose a particular hardship for a pregnant

woman. Five nations (Austria, Denmark, Greece, Norway, and

Sweden) allow elective abortions early in pregnancy, and strictly

limit abortions thereafter. Only the United States permits elective

abortion until viability. Id. at 13-15 & Table 1, 145-154. Indeed,

Eastern European nations and the former Soviet Union had

greater restrictions on abortion than this country does. Id. at 23-

24. Thus, the fact that the regime created by Roe is so out of step

with these judgments suggests that it is Roe, not the pre-Roe state

of our law, that is “ an historical accident.”

After the publication of Professor Glendon’s book, the Canadian

Supreme Court struck down its abortion law on grounds similar

to those stated in Roe. Morgentaler v. Regina, 1 S.C.R. 30, 44

D.L.R.4th 385 (1988). The West German constitutional court, by

contrast, had earlier struck down a law liberalizing access to abor

tion on the grounds that “ ‘life developing within the womb’ is

constitutionally protected.” Judgment of Feb. 25, 1975, 39 BVerfGE

1 (quoted in M. Glendon, supra, at 26). See 9 J. Marshall J. Prac.

& Proc. 605 (1975) (reprinting decision).

13

b. Petitioners argue that “ compelled continuation of

a pregnancy infringes on a woman’s right to bodily in

tegrity by imposing substantial physical intrusions and

significant risks of physical harm” and that abortion re

strictions deny women “ the right to make autonomous

decisions about reproduction and family planning.” Pet.

Br. 24, 26. Roe made a similar point. 410 U.S. at 153.10

10 Roe did not seek to ground a right to abortion in the text of

the Constitution or this Nation’s history and tradition. Instead,

Roe fashioned the “ fundamental right” to abortion by reference to

several decisions of this Court. Roe described those decisions as

recognizing a “guarantee of personal privacy,” which “has some

extension to activities relating to marriage, procreation, contracep

tion, family relationships, and child rearing and education.” 410

U.S. at 152-153 (citations omitted). “ This right to privacy,” Roe

declared, “ is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision

whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.” Id. at 153.

That line of reasoning, with all respect, is deeply flawed. Even

if this Court’s pre-Uoe decisions have a common denominator, it

is not a highly abstract right to “ privacy,” but a recognition of the

importance of the family. Cf. Michael H., 491 U.S. at 123

(plurality opinion). Even if those cases have “some extension”

to “activities relating to” the family, abortion is “ inherently dif

ferent” from activities such as the use of contraceptives. Abortion,

after all, “ involves the purposeful termination of potential life.”

Harris v. McRae, 448 U.S. 297, 325 (1980); see generally Thorn

burgh, 476 U.S. at 792 n.2 (White, J., dissenting). For that reason,

Roe itself realized that a “ pregnant woman cannot be isolated in her

privacy.” 410 U.S. at 159. In sum, Roe derived a right to abortion

from pre-Roe cases only by creating an artificial common denomina

tor while denying what makes abortion unique.

By contrast, a law mandating abortions would pose a starkly

different issue. At common law, a competent adult had a right to

refuse medical care, and involuntary treatment was a battery ab

sent consent or an emergency. Schloendorff v. Society of the New

York Hosp., 211 N.Y. 125, 129-130, 105 N.E. 92, 93 (1914) (Car-

dozo, J . ) ; 3 F. Harper, F. James, Jr. & O. Gray, The Law of Torts

§17.1 (2d ed. 1986). Relying on that tradition, the Court has held

that a competent adult has a liberty interest protected by due

process in refusing unwanted, state-administered medical care.

Washington v. Harper, 494 U.S. 210, 229 (1990) ; Vitek v. Jones,

445 U.S. 480, 494 (1980). Moreover, a compelled intrusion into a

person’s body is a “ search” under the Fourth Amendment, Schmer-

14

We readily agree that pregnancy (like abortion) entails

“profound physical, emotional, and psychological conse

quences.” Michael M. v. Superior Court, 450 U.S. 464,

471 (1981) (plurality opinion). But those burdens, albeit

substantial, do not themselves give rise to a fundamental

right. As this Court has recognized, governmental re

fusal to fund abortions can be quite burdensome, yet the

Constitution does not guarantee a woman the right to

such funds. And that is so even if the State funds child

birth expenses. Webster, 492 U.S. at 507-511. The re

fusal to supply other forms of government assistance can

prove harmful, yet the Constitution does not require a

State to intervene to prevent harm from befalling a per

son. DeShaney v. Winnebago County Dep’t of Social

Servs., 489 U.S. 189 (1989) (police protection); Lindsey

v. Normet, 405 U.S. 56 (1972) (shelter). I f risk of

physical or psychological harm were sufficient to create a

constitutional right, a person would arguably have a

right to avoid vaccinations or military service. But there

is no such right. Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11

(1905); Selective Draft Law Cases, 245 U.S. 366 (1918) ;

Cox v. Wood, 247 U.S. 3 (1918). In sum, risk of harm,

standing alone, does not give rise to a constitutional

right.

Nor is this conclusion altered by the fact that abortion

is a controversy “ of a ‘sensitive and emotional nature,’

generating heated public debate and controversy, ‘with

vigorous opposing views’ and ‘deeply and seemingly abso

lute convictions.’ ” New York et al. Br. 11 (quoting Roe,

410 U.S. at 116). Other subjects, such as capital punish

ment, likewise evoke strong emotions and inspire heated

debate. Yet the Constitution leaves such questions in the

main to the political process to decide.11 In short, the Due

ber V. California, 384 U.S. 757, 767-768 (1966), and the Fourth

Amendment prohibits as unreasonable certain forcible intrusions

into a person’s body, Winston V. Lee, 470 U.S. 753 (1985).

11 The Court has, of course, established limits in that regard.

See, e.g., Coker V. Georgia, 433 U.S. 584 (1977). But within those

15

Process Clause does not remove issues from the political

process and put them before the judiciary for resolution

because they are difficult and divisive.

We believe that the proper inquiry in reviewing an

abortion regulation is whether the regulation is reason

ably designed to advance a legitimate state interest,

as a plurality of this Court articulated in Webster. 492

U. S. at 520. That standard of review is deferential,

but not toothless. Indeed, this Court has held laws in

valid under such a standard. Compare, e.g., Metropoli

tan Life Ins. Co. v. Ward, 470 U.S. 869 (1985); Zobel

V. Williams, 457 U.S. 55 (1982); United States Dep’t of

Agric. v. Moreno, 413 U.S. 528 (1973). No reason exists

to assume that courts will abdicate their responsibility

to ensure that abortion regulations pass muster under

that standard. Legislatures under that constitutional

regime will not be able arbitrarily or unreasonably to

constrain a woman’s liberty interest.

2. The S tate has a com pelling in terest in p ro tect

ing the fetu s throughout pregnancy

Even if the Court’s pre-Roe decisions could be said to

create a right of “privacy” or to “ accomplish or prevent

conception,” Carey v. Population Servs. Int’l, 431 U.S.

678, 685 (1977), that conclusion would not end the

inquiry. The Court’s decisions make clear that a State

can limit or even forbid conduct that is otherwise entitled

to constitutional protection if the State acts precisely to

vindicate a compelling interest. See, e.g., Haig v. Agee,

453 U.S. 280, 308-309 (1981) (the government may re

voke the passport of a person who wishes to travel in

order to disclose intelligence operations and the names

of intelligence personnel); Lee v. Washington, 390 U.S.

333, 334 (1968) (Black, J., concurring) (the govern

ment may take threats and tensions from prison racial

strife into account for the purpose of maintaining se

curity and order in prison); Near v. Minnesota, 283

limits, the policy question of using capital punishment is one en

trusted to the political processes in a democratic society.

16

U.S. 697, 716 (1931) (dictum that military needs justify

a prior restraint on the disclosure of the sailing date of

troop ships). That principle is as applicable in this con

text as in any other, because, as Justice Harlan once

noted, “ [t]he right of privacy most manifestly is not an

absolute.” Poe v. Ullman, 367 U.S. 497, 552 (1961)

(Harlan, J., dissenting). The protection of innocent hu

man life— in or out of the womb— is certainly the most

compelling interest that a State can advance. See Illi

nois V. Gates, 462 U.S. 213, 237 (1983) (“ [t]he most

basic function of any government” is “ to provide for

the security of the individual and of his property” )

(quoting Miranda V. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 539 (1966)

(White, J., dissenting)). In our view, a State’s interest

in protecting fetal life throughout pregnancy, as a gen

eral matter, outweighs a woman’s liberty interest in an

abortion. The State’s interest in prenatal life is a wholly

legitimate and entirely adequate basis for restricting the

right to abortion derived in Roe.

Central to Roe was the conclusion that the State lacks

a compelling interest in preserving fetal life throughout

pregnancy. Roe noted that a woman’s right to terminate

a fetus “ is not unqualified and must be considered against

important state interests” in “ safeguarding health, in

maintaining medical standards, and in protecting po

tential life.” 410 U.S. at 154. But Roe stated that the

weight of those interests is not uniform from conception

to birth; instead, they “ grow[] in substantiality as the

woman approaches term.” Id. at 162-163. Particularly

critical in this regard was Roe’s conclusion that a State’s

“ important and legitimate interest in potential life” is

not “ compelling,” i.e., sufficiently weighty to overcome

the fundamental right to abortion, until the fetus has

reached viability, since only then is the fetus capable of

“ meaningful life outside the mother’s womb.” Id. at 163.

The proposition that a State’s interest in protecting

life in the womb is compelling only at viability “ seems

to mistake a definition for a syllogism.” Ely, The Wages

17

of Crying Wolf: A Comment on Roe v. Wade, 82 Yale

L.J. 920, 924 (1973).12 “ The choice of viability as the

point at which the state interest in potential life becomes

compelling is no less arbitrary than choosing any point

before viability or any point afterward.” Akron I, 462

U.S. at 461 (O’Connor, J., dissenting). Even if the

importance of a State’s interest in protecting the fetus

parallels the fetus’s development, it does not follow that

the State’s interest in this regard is not compelling

throughout a pregnancy. An interest may be sufficiently

weighty to be “compelling” in the constitutional sense

even if it later assumes still greater urgency. Accord

ingly, since “potential life is no less potential in the first

weeks of pregnancy than it is at viability or afterward,”

Akron I, 462 U.S. at 461 (O’Connor, J., dissenting), the

State’s interest in protecting prenatal life “ if compelling

after viability, is equally compelling before viability,”

Webster, 492 U.S. at 519 (plurality opinion); Thorn

burgh, 476 U.S. at 828 (O’Connor, J., dissenting).

Roe itself recognized that laws infringing on a funda

mental right are not automatically invalid; they survive

strict scrutiny if they are “narrowly drawn to express

only the legitimate state interests at stake.” 410 U.S.

at 155. Accordingly, because the State’s interest in pro

tecting prenatal life is compelling throughout pregnancy,

12 See J. Mohr, supra, at 165 (“ Most [19th century] physicians

considered abortion a crime because of the inherent difficulties of

determining any point at which a steadily developing embryo be

came somehow more alive than it had been the moment before.

Furthermore, they objected strongly to snuffing out life in the

making.” ) ; see also id. at 35-36, 200; L. Tribe, American Con

stitutional Lau; 1349 (2d ed. 1988) ( “nothing in [Roe] provides a

satisfactory explanation of why the fetal interest should not be

deemed overriding prior to viability, particularly when a legisla

tive majority chooses to regard the fetus as a human being from

the moment of conception and perhaps even when it does not” )

(footnotes omitted).

18

we believe that regulations furthering that interest are

lawful throughout pregnancy.13

13 Petitioners may even agree with us to some extent. The Act

prohibits pre-viability abortions based on the sex of the fetus.

18 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann. § 3204(c) (Purdon Supp. 1991). While

petitioners ask the Court to reaffirm Roe, which bars a State from

outlawing previability abortions, petitioners did not contend in the

courts below, and they do not argue in this Court, that this pro

vision is unconstitutional. It is not difficult to understand why.

The prospect that a woman would terminate life in the womb

merely because it is a boy or a girl surely should be so utterly

odious to every member of “ a free, egalitarian, and democratic

society” like ours, Thornburgh, 476 U.S. at 793 (White, J., dis

senting), that any such abortion would be properly subject to

universal condemnation. At the very least, no one could seriously

claim that the Constitution offers the remotest protection for

such a macabre act. Yet, i f a State has a compelling interest in

forbidding gender-selection abortions, the Roe trimester frame

work cannot survive intact. And if the State has a compelling

interest in prohibiting abortions for that reason, it may fairly

be asked why the State lacks a similar compelling interest in out

lawing abortions for other reasons. A State which believes that a

child in the womb should not be destroyed simply because it is a

boy or a girl should also be free to protect that life if it is the

second (or third, etc.) child to be born, or if the pregnancy oc

curred despite the use of contraceptives.

Petitioners contend that “ the right to abortion may be grounded”

in constitutional rights other than due process. Pet. Br. 19 n.27.

In our view, those claims are meritless. Indeed, the ceaseless quest

for a textual basis for the constitutional right to abortion only

underscores the lack of any such support. See, e.g., Harris v. Mc

Rae, 448 U.S. at 319-320 (rejecting Establishment Clause challenge

to Hyde Amendment) ; Bowen v. Kendrick, 487 U.S. 589 (1988)

(same, Public Health Service Act (the Adolescent Family Life Act

of 1981), 42 U.S.C. 300z et seq.) ; Employment Division, Dep’t of

Human Resources v. Smith, 494 U.S. 872, 879-890 (1990) (Free

Exercise Clause does not invalidate neutral laws directed at secular

subjects; rejecting Free Exercise challenge to statute banning drug

use) ; Reynolds v. United States, 98 U.S. 145 (1879) (same, laws

banning polygamy); Prince v. Massachusetts, 321 U.S. 158 (1944)

(same, law banning child labor, as applied to distribution o f reli

gious pamphlets); Jehovah’s Witnesses v. King County Hasp., 390

U.S. 598 (1968), aff’g 278 F. Supp. 488 (W.D. Wash. 1967) (up

holding life-saving transfusion for a minor child over parents’

19

II. THE PENNSYLVANIA ABORTION CONTROL ACT

IS REASONABLY DESIGNED TO ADVANCE LE

GITIMATE STATE INTERESTS

Petitioners claim that the Act is unconstitutional under

any standard of review. Pet. Br. 40-61. In so arguing,

petitioners and amici (e.g., ACOG Br. 17-20; American

Psychological Ass’n B r.; City of New York et al. B r.;

NAACP Legal Defense and Educ. Fund et al. B r.; Penn

sylvania Coalition Against Domestic Violence et al. Br.)

rely heavily on the burden that could befall some women

from provisions such as the spousal notification require

ment. Yet, as the court of appeals noted, petitioners

brought a facial constitutional challenge to the statute,

not an as-applied challenge. Pet. App. 5a, 41a. Thus,

the governing legal standard is exacting: Petitioners

must prove that the statute cannot be constitutionally

applied to anyone. See, e.g., Ohio v. Akron Center for

Reproductive Health, 110 S. Ct. 2972, 2980-2981 (1990)

(Akron II ) ; United States v. Salerno, 481 U.S. 739, 745

(1987); Webster, 492 U.S. at 524 (O’Connor, J., con

curring). This they cannot do.14

Informed consent. Under the Pennsylvania statute, a

woman must be given medical and other information by a

physician or his agent, and she must wait 24 hours before

consenting to an abortion.15 Those provisions are valid.

Free Exercise claim; relying on Prince) ; United, States v. Kozmin-

ski, 487 U.S. 931, 944 (1988) (Thirteenth Amendment does not

apply to established common law cases, such as parents’ right to

custody of their children) ; U.S. Brief in Bray v. Alexandria

Women’s Health Clinic, No. 90-985 (opposition to abortion is not

gender discrimination) (a copy has been supplied to the parties’

counsel) ; see generally Bopp, Will There Be a Constitutional Right

to Abortion A fter the Reconsideration of Roe v. Wade?, 15 J.

Contemp. L. 131 (1989).

14 The majority in Akron I and Thornburgh struck down statu

tory requirements similar to those here. The Webster plurality,

however, explained that many o f the rules adopted in Roe and

later cases would not be of “constitutional import” once Roe’s

trimester framework is abandoned. 492 U.S. at 518 n.15.

15 A referring or performing physician must inform a woman

about (i) the nature of the procedure and risks and alternatives

20

The State has a legitimate interest in ensuring that a

woman’s decision to have an abortion is an informed one.

Thornburgh, 476 U.S. at 760; Akron I, 462 U.S. at 443;

Planned Parenthood v. Danforth, 428 U.S. 52, 67 (1976).16

Accurate information about the abortion procedure and

its risks and alternatives is related to maternal health

and a State’s legitimate purpose in requiring informed

consent. Akron I, 462 U.S. at 446. An accurate descrip

tion of the gestational age of the fetus and the risks

involved in carrying a child to term furthers those

interests and the State’s concern for potential life. See

Thornburgh, 476 U.S. at 798-804 (White, J., dissenting);

id. at 830-831 (O’Connor, J., dissenting).17 Likewise, the

State’s interest in preserving potential life is rationally

served by informing women that medical assistance ben

efits and paternal child support may be obtainable, and

by making available accurate information about the

that a reasonable patient would find material; (ii) the fetus’s prob

able gestational age; and (iii) the medical risks involved in carry

ing a pregnancy to term. 18 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann. § 3205(a)(1)

(Purdon Supp. 1991). A physician or a qualified agent also must

tell a woman that (i) medical assistance benefits may be available

for prenatal, childbirth, and neonatal care; (ii) the child’s father

is liable for child support; and (iii) the state health department

publishes free materials describing the fetus at different stages

and listing abortion alternatives. Id. §3205 (a) (2) (Purdon 1983

& Supp. 1991). A 24-hour waiting period follows.

16 At common law and today, a physician must obtain patients’

consent to the contemplated scope of an operation without mislead

ing them about its nature or probable consequences, and must in

form patients about the risks posed by available alternative treat

ments. See, e.g., Cruzan, 110 S. Ct. at 2846-2847; Slater v. Baker,

2 Wils. 359, 95 Eng. Rep. 860 (K.B. 1767) ; 3 F. Harper, F. James,

Jr. & O. Gray, supra, § 17.1.

17 Petitioners’ claim that non-physician counselors can provide

the same information is beside the point. As the court of appeals

observed, it was reasonable for the State to conclude that disclosure

by physicians will be more effective than delegation o f that task

to others. Pet. App. 47a-48a.

21

process of fetal growth and alternatives to abortion. Id.

at 831 (O’Connor, J., dissenting).

The fact that some information may be of little or no

use to some recipients, Pet. App. 177a-180a, does not

cast doubt on the validity of the Act. Where, as here, no

fundamental right is at stake, government may regulate

conduct in an overinclusive manner, as long as it does

so rationally. Vance v. Bradley, 440 U.S. 93, 108 (1979).

A State’s belief that its interests are better served with

an informed consent provision than without one is, in

our view, entirely rational.

It is no argument that the disclosure of accurate in

formation might persuade some women not to have an

abortion. Encouraging childbirth is a legitimate gov

ernmental objective. Harris v. McRae, 448 U.S. 297, 322-

323 (1980); Maher V. Roe, 432 U.S. 464, 478-479 (1977).

Roe did not purport to impress on the Constitution the

proposition that abortion is a public good. Thornburgh,

476 U.S. at 797 (White, J., dissenting). Instead, Roe

professed agnosticism on the question when life begins

and declined to debate the morality of abortion. 410 U.S.

at 116-117, 159-162. Thus, the fact that the informed

consent provision may dissuade some women from having

an abortion does not undermine its validity.18

Lastly, the Act’s 24-hour waiting period readily passes

muster. A waiting period provides time for reflection

and reconsideration, furthering a State’s interests in in

formed consent and protecting fetal life. A mandatory

18 Nor do the informed consent provisions violate the First

Amendment rights of physicians or counselors. States are free to

require professionals to include accurate and reasonably material

information in their commercial speech directed toward prospec

tive clients. Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel, 471 U.S.

626, 650-651 (1985). Truthful and relevant information about

risks, alternatives, and medical and financial facts is not the kind

of “prescribe [d] * * * orthodox [y] in politics, nationalism, reli

gion, or other matters of opinion” that violates the First Amend

ment’s protection o f commercial speech. Id. at 651; cf. Riley v.

National Fed’n of the Blind, 487 U.S. 781, 796 n.9 (1988).

22

waiting period burdens women seeking abortions, but the

State is constitutionally at liberty to weigh the com

peting concerns and to strike what it sees as an appropri

ate balance. The abortion decision, once implemented,

is an irrevocable one, and the unique psychological con

sequences of that singular act will remain with a woman

(and her spouse or partner) throughout their lives. What

ever the wisdom of the State’s decision, it is clearly a

rational one. See Harris v. McRae, 448 U.S. at 326.

Informed parental consent. An unemancipated or in

competent minor must give her informed consent and

obtain that of a parent or guardian before she can

obtain an abortion. 18 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann. § 3206(a)

(Purdon 1983 & Supp. 1991).19 Alternatively, a minor

can obtain an abortion if a state court finds that she

is mature, is capable of giving informed consent, and

gives such consent, or that an abortion is in her best

interests. Id. § 3206(c) and (d) (Purdon 1983); see

id. § 3206(e)-(h) (Purdon 1983 & Supp. 1991) (bypass

procedures). Those provisions are valid, too.

In our view, a minor has no fundamental right to an

abortion without parental consent.20 In addition, a State

has a strong and legitimate interest in involving par

ents in matters affecting their children’s well-being, in

cluding abortion. See, e.g., Hodgson, 110 S. Ct. at 2948

(opinion of Stevens, J . ) ; id. at 2950-2951 (opinion of

19 Consent of the child’s guardian (s) is sufficient if both parents

are dead or otherwise unavailable to the physician in a reasonable

time and manner. Consent of a custodial parent is sufficient if the

child’s parents are divorced. Consent of an adult standing in loco

parentis is sufficient if neither a parent nor a guardian is available

to the physician in a reasonable time and manner. 18 Pa. Cons.

Stat. Ann. § 3206(b) (Purdon 1983). In the case of pregnancy due

to incest by the child’s father, the minor need obtain consent only

from her mother. 18 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann. § 3206(a) (Purdon

1983 & Supp. 1991).

20 Our position in this regard is set forth in our amicus brief in

Hodgson V. Minnesota, Nos. 88-1125 & 88-1309, a copy of which has

been provided to the parties’ counsel.

23

O’Connor, J .) ; id. at 2970 (opinion of Kennedy, J.).

Parental consent laws reasonably advance that interest.

Furthermore, if the informed consent provision is valid,

the informed parental consent provision is valid, too. A

State has a keener interest in protecting minors than

adults against their improvement choices.

Spousal notification. The Act adopts a spousal notifi

cation requirement in order “ to further the Common

wealth’s interest in promoting the integrity of the marital

relationship,” in “protect [ing] a spouse’s interests in

having children within marriage,” and in “ protecting the

prenatal life of that spouse’s child,” 18 Pa. Cons. Stat.

Ann. § 3209(a) (Purdon Supp. 1991). With certain

exceptions, a woman must give the physician a signed

statement, under penalty for making a false statement,

that she has notified her spouse that she will undergo an

abortion. Ibid.21 This notification requirement readily

survives facial challenge, because it is reasonably de

signed to further a number of legitimate state interests.22 *

First, spousal notification is reasonably designed to ad

vance a State’s legitimate interest in protecting the fetus.

21 A woman need not provide the statement if her spouse is not

the child’s father; if he could not be located after a diligent

search; if the pregnancy is the result of a spousal sexual assault

that has been reported to the authorities; or i f she has reason to

believe that notifying her spouse will lead her to suffer bodily in

jury by him or someone else. Id. § 3209(b) (Purdon Supp. 1991).

22 Pennsylvania is not alone in recognizing and protecting the

husband’s interest in the life of his unborn child. Before and during

the 19th century, when abortion was strictly regulated and gen

erally prohibited by state law, there was no need for special pro

tection of the father’s interests. See Poe V. Gerstein, 517 F.2d

787, 795 (5th Cir. 1975), aff’d, 428 U.S. 901 (1976). By the time

of Roe, some States had liberalized their abortion laws, and many

o f the new laws acknowledged and protected the father’s role in

the abortion decision. Doe v. Doe, 365 Mass. 556, 561 & nn.3-5, 314

N.E.2d 128, 131 & nn.3-5 (1974) (citing statutes of 15 States re

quiring husband’s consent for abortions under some or all circum

stances). A number of spousal consent and notification laws are

currently on the books. See, e.g., Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 18-6-

101(1) (West 1986) (spousal consent).

24

The husband sometimes will oppose a proposed abortion.

After being notified, he may persuade his spouse to recon

sider her decision, thus achieving the State’s interest.

Cf. Pet. App. 255a-256a.

Second, a husband’s interests in procreation within

marriage and in the potential life of his unborn child

are unquestionably legitimate and substantial ones.23 It

can hardly be gainsaid that the State acts legitimately in

seeking to protect such parental and familial interests.

See Michael H., 491 U.S. at 128-129 (opinion of Scalia,

J.) (husband’s opportunity “ to develop a relationship

with” the offspring of the marital community may be pro

tected by the State) (quoting Lehr v. Robertson, 463 U.S.

248, 262 (1983 )); Labine v. Vincent, 401 U.S. 532, 538

(1971). The spousal notification requirement is certainly

a reasonable means of advancing that state interest. By

providing that, absent unusual circumstances, a husband

will know of his spouse’s intent to have an abortion, the

notification requirement ensures at least the possibility

that the husband will participate in deciding the fate of

his unborn child, a possibility that might otherwise have

been denied him. The husband’s participation, in turn,

may lead his spouse to reconsider her options or to re

think a hasty decision.24 As Judge Alito noted in dissent

23 See Danforth, 428 U.S. at 69; id. at 93 (White, J., dissenting

in part) ; Skinner V. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535, 541 (1942). Dan

forth held that a State could not condition a woman’s access to an

abortion on the consent of her spouse, but that conclusion rested

on the flawed premise that “ the State cannot regulate or proscribe

abortion during the first stage” of pregnancy. 428 U.S. at 69. A

spousal notification requirement also impinges far less severely on

a woman’s ability to have an abortion than does a spousal consent

requirement. See Akron II, 110 S. Ct. at 2979.

24 No doubt most wives would consult with their husbands even

absent a statutory notice requirement. Pet. App. 193a. Nonethe

less, the Act will likely increase the number of such consultations.

Many women who otherwise might choose not to tell their spouses of

their decision, for reasons of convenience, haste, or concern about

disagreement, will be inclined to comply because of the legislative

mandate.

25

below, the state legislature “ could have rationally believed

that some married women are initially inclined to obtain

an abortion without their husbands’ knowledge because of

perceived problems— such as economic constraints, future

plans, or the husbands’ previously expressed opposition—

that may be obviated by discussion prior to the abortion.”

Pet. App. 102a.

Finally, and for essentially the same reasons, the

State’s interest in “ promoting the integrity of the mari

tal relationship,” 18 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann. § 3209(a)

(Purdon Supp. 1991), is reasonably furthered by the

spousal notice requirement. That interest is legitimate,

Akron I, 462 U.S. at 443 n.32, and is properly encom

passed by the State’s traditional power to regulate mar

riage and strengthen family life, see Sosna v. Iowa, 419

U.S. 393, 404 (1975); Labine, 401 U.S. at 538. Petition

ers’ claim, Pet. Br. 43-44, and the district court’s ruling,

Pet. App. 261a-262a, that the notification requirement

does not fui’ther the State’s interest misses the point.

The interest that Pennsylvania has chosen to foster is

marital integrity, not “ [mjarital accord,” Pet. App. 262a.

A State may legitimately elect to ensure truthful marital

communication concerning a crucial issue such as abor

tion, despite the possibility that marital discord may re

sult in some instances. See Scheinberg v. Smith, 659 F.2d

476, 484-486 & n.4 (5th Cir. 1981).

Petitioners make much of the possibility that some

women may be deterred from obtaining an abortion if

they must notify their spouses. Pet. Br. 41-43. But the

State could reasonably have concluded that the statutory

exceptions for women who reasonably fear bodily injury

and for pregnancies resulting from spousal assault would

eliminate the principal bases for that concern. The pos

sibility that some women may not take advantage of the

exceptions, or may fear other consequences of notification,

does not affect the facial validity of the statute. See

Hodgson, 110 S. Ct. at 2968 (opinion of Kennedy, J.)

( “ Laws are not declared unconstitutional because of some

general reluctance to follow a statutory scheme the legis-

26

lature finds necessary to accomplish a legitimate state

objective.” ). The State weighed the complex social and

moral considerations involved and found such concerns

insufficient to overcome the countervailing factors. The

wisdom of such a clearly rational decision is not for the

courts to judge. See Harris v. McRae, 448 U.S. at 32G.25

Medical emergency. A “medical emergency” is an ex

ception to the above requirements of the Act.26 Petition

ers argued below that the statutory definition of medical

emergency was inadequate since it did not include three

serious conditions that pregnant women can suffer (pre-

clampsia, inevitable abortion, and prematurely ruptured

membrane). The district court ruled that the definition

did not include those conditions, Pet. App. 237a, but the

court of appeals disagreed, Pet. App. 41a, relying on the

“well-accepted canon [] of statutory interpretation used

in the [state] courts,” Webster, 492 U.S. at 515 (plural-

25 Petitioners argue that the spousal notification requirement

violates the Equal Protection Clause and impermissibly intrudes

on “ the protected marital relationship.” Pet. Br. 44-48. In our

view, neither claim has merit. Women who want an abortion are

not a “ suspect” or “ quasi-suspect” class deserving of heightened

scrutiny under the Equal Protection Clause. See Harris V. McRae,

448 U.S. at 323; Maher v. Roe, 432 U.S. at 470-471; cf. Geduldig V.

Aiello, 417 U.S. 484, 496-497 n.20 (1974). Likewise no generalized

right of marital privacy is infringed by the spousal notification

requirement. If the State may— indeed must, see Kirchberg v.

Feenstra, 450 U.S. 455 (1981)— require the participation of both

spouses in the disposition of marital property, surely it may re

quire that they both be aware of the far more important decision

to terminate a pregnancy.

2<! A “ medical emergency” is defined as “ [t]hat condition which,

on the basis of the physician’s good faith clinical judgment, so

complicates the medical condition of a pregnant woman as to neces

sitate the immediate abortion of her pregnancy to avert her death

or for which a delay will create serious risk o f substantial and ir

reversible impairment of major bodily function.” 18 Pa. Cons. Stat.

Ann. § 3203 (Purdon Supp. 1991).

27

ity opinion), that a statute should be read to preserve its

constitutionality and on the fact that petitioners chal

lenged the Act on its face. Pet. App. 37a, 41a.2T

Petitioners do not argue that the Act cannot be read

that way. Instead, they criticize the Third Circuit for

reading the Act too narrowly, as protecting women only

from “ significant” health risks. Pet. Br. 60-61. Due

process, however, does not require the State to avoid

placing insignificant health risks on individuals for the

public benefit. This Court in Jacobson v. Massachusetts

upheld a compulsory smallpox vaccination even though

the vaccine had a statistical possibility of causing serious

illness or death. In this case, the State has a compelling

interest in protecting the fetus, which “ justifies] sub

stantial and ordinarily impermissible impositions on the

individual,” including “ the infliction of some degree of

risk of physical harm.” Thornburgh, 476 U.S. at 808-

809 (White, J., dissenting).

Reporting requirements. Facilities performing abor

tions have various reporting obligations.27 28 The require-

27 The State also reads the definition to include all three condi

tions. See Appellants C.A. Br. 5-7, 23-25. A state attorney gen

eral’s interpretation of a state law is not binding on the state

courts, Virginia V. American Booksellers Ass’n, 484 U.S. 383, 397

(1988), but may be useful in construing state law, cf. Minnesota

V. Probate Court, 309 U.S. 270, 273-274 (1940) (relying on the

state attorney general’s reading of the state supreme court’s

opinion).

28 Each facility must file a report with its name and address and