Draft Order to submit a Plan of Unitary School Operation

Working File

January 1, 1971

6 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Draft Order to submit a Plan of Unitary School Operation, 1971. 7f97aaaa-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4c13f51b-80f4-47cb-aa9b-06f2e3abd8ef/draft-order-to-submit-a-plan-of-unitary-school-operation. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

va.x).£^/-

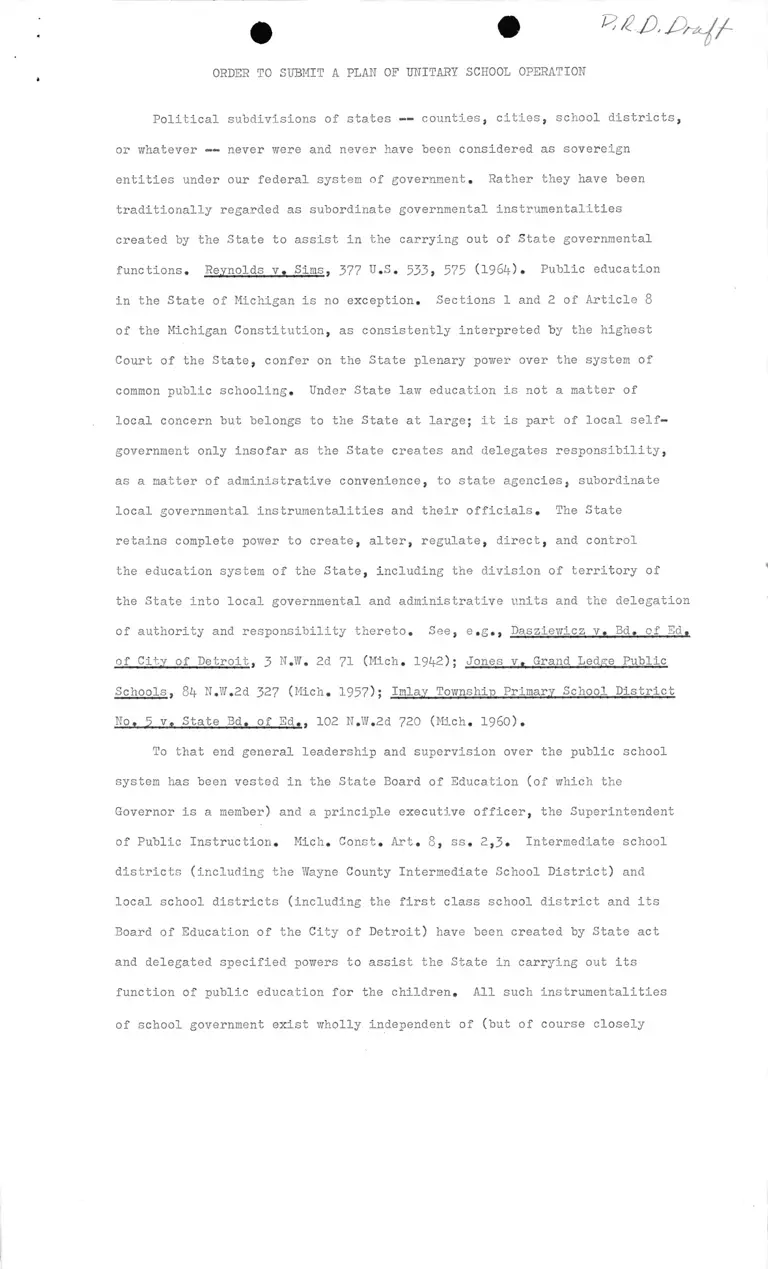

ORDER TO SUBMIT A PLAN OF UNITARY SCHOOL OPERATION

Political subdivisions of states — * counties, cities, school districts,

or whatever — never were and never have been considered as sovereign

entities under our federal system of government. Rather they have been

traditionally regarded as subordinate governmental instrumentalities

created by the State to assist in the carrying out of State governmental

functions. Reynolds v. Sims. 377 U.S. 533} 575 (196^). Public education

in the State of Michigan is no exception. Sections 1 and 2 of Article 8

of the Michigan Constitution, as consistently interpreted by the highest

Court of the State, confer on the State plenary power over the system of

common public schooling. Under State law education is not a matter of

local concern but belongs to the State at large; it is part of local self-

government only insofar as the State creates and delegates responsibility,

as a matter of administrative convenience, to state agencies, subordinate

local governmental instrumentalities and their officials. The State

retains complete power to create, alter, regulate, direct, and control

the education system of the State, including the division of territory of

the State into local governmental and administrative units and the delegation

of authority and responsibility thereto. See, e.g., Daszlewicz v. 3d. of Ed,

of City of Detroit. 3 N.W. 2d 71 (Mich. 19^2); -Jones v. Grand Ledge Public

Schools, 8*f N.W.2d 327 (Mich. 1957); Inlay Township Primary School District

No. 5 v. State 3d. of Ed.. 102 N.W.2d 720 (Mich. I960).

To that end general leadership and supervision over the public school

system has been vested in the State Board of Education (of which the

Governor is a member) and a principle executive officer, the Superintendent

of Public Instruction. Mich. Const. Art. 8, ss. 2,3* Intermediate school

districts (including the Wayne County Intermediate School District) and

local school districts (including the first class school district and its

Board of Education of the City of Detroit) have been created by State act

and delegated specified powers to assist the State in carrying out its

function of public education for the children. All such instrumentalities

of school government exist wholly, independent of (but of course closely

- 2

cooperate with many) general municipal, city, and county governments

Education has been made compulsory for all children with a few narrow

exceptions; and historically school authorities have assigned the children,

who choose to meet that obligation in the public system of common schools,

to a particular public school facility.

"The equal protection clause speaks to the state." Hall v, St. Helena

Parish School Bd.. 197 F.Supp. 649, 658 (E.D.La. 1961) (3 Judge Court, per

Wisdom, Christenberry and Wright), aff'd . All the delegees

(State Board of Education, State Superintendent of Public Instruction,

intermediate and local school districts) of State authority over public

education, and all their agents and employees, are agents of the State;

their actions, undertaken in an official capacity or otherwise relative to

public schooling, are those of the State for purposes of the 14th amendment

and are subservient thereto. Ex Parte Young ; Sooner v.

Aaron. 358 U.S, 1 , 16-17 (1958); Haney v. Sevier County School Bd.. 410 F.2d

920 (8th Cir. 1969)* The 14th amendment imposes on the State, and all its

public school and other authorities, the affirmative obligation to avoid

racial discrimination and actions which will have the effect of disadvantaging

members of the black race as such. In the field of public education, where

the State, as here, offers an education to some, it is now under an affirmative

obligation to make that educational opportunity available to all on substan

tially equal terms and eschew the separation of black and white children and

faculty in "Negro" and "White" schools. Brown v. Board of Education. 347 U.S.

433 (1954); Green v. County School 3d.. 391 U.S. l t f l (1968).

With respect to plaintiff class in this cause, the State and all its

agents have not fulfilled that obligation. As set forth more fully in the

preliminary findings of fact and conclusions of law here attached, the State

has long deprived black children in the City of Detroit that equal educational

opportunity and acted to contain black children and faculty in racially

identifiable and separate schools from white children and faculty. Such

violations of plaintiffs* constitutional rights have included the following:

1/ Territorial jurisdictions of such school government instrumentalities need

not be and often are not coterminus with municipal, county, city, or other

special districts. Although the first class school district of the City

of Detroit now corresponds to the boundaries of the City of Detroit, such

has not always been the case.

1 , a variety of financing and resource allocation practices (including

general state aid, expenditures per pupil, and reimbursement for trans

portation); 2, teacher hiring and assignment; and 3. student assignment.

More particularly, the State’s imposition of segregation in the public

schools through student assignment practices has included the creation

and maintenance of school attendance boundaries which have had the natural

and probable effect of containing black children in separate schools.

Included among these unconstitutional school attendance boundaries are

those that are coincident with boundaries of the local school districts.

The creation and maintenance of those attendance boundaries has had the

same natural and probable effect as well. Both state and local defendants

were aware of this problem and had the power to right the wrong thereby

perpetuated; but despite some tentative efforts, they have failed to

eradicate the wrong

In such circumstances there can be no question that the pervasive

segregation in the public schools within the City of Detroit and throughout

the metropolitan area is state-imposed. And where, as here, the right of

black children and its violation by the defendants has been shown,

"the scope of /this Court »s/ equitable powers to remedy

past wrongs is broad," Swann. Davis v, Pontiac School Bd,,

(6th Cir, FN1),

and includes all aspects of pupil assignment, transportation, personnel,

resource allocation, revision of school attendance areas, and reorganization

of school districts. Brown II, 3k9 U.S. 2 % (1955); Swann: Haney. It is

the obligation of this Court to insure that plaintiffs in this cause get

the kind of education that is given in the State’s public schools pursuant

to the commands of the United States Constitution, G-rlffin y« Prince Bdward

County, 377 U,S. 218 (196A). It is the obligation of defendents to come

2/ The Court does not mean to suggest that any of the particular individuals

now before the court as party defendant has acted with malevolent intent.

But the state-imposed segregation persists, alleviated only by a few

symbolic efforts and political compromises which served only to perpetuate

segregation in the schools. By now it should be patent, however, that the

rights of black school children to full equality in public education does

not depend on the will of the dominant white majority and its hostility

in deed to vindication of these rights. Brown II. Cooper. Monroe»

The natural and probable effect of actions by persons acting under color

of state authority has been to segregate the schools on a racial basis;

only one purpose can be attributed under the Constitution to that pervasive

pattern, Cf, Pontiac and Hew York v« Heberts. 171 U.3. 658, 681 (1898)

(Harlan, dissenting),

forward with a plan that promises realistically to work now until it is

clear that state-imposed segregation in the public schools has been

completely removed. Green; Alexander; Swann. The goal of such plan shall

(0be^the elimination of racial identifiability from the schools in pupil

and teacher assignment so that no school is substantially disproportionate

in its student and faculty racial mix relative to their respective racial

(2)+ke, ailcccCtVDvn o f

mixes in the immediate area andj_objectively measurable resources and

expenditures per pupil aiss -~Bllaeg|fettd on a substantially equal basis per

pupil in each schoolf. There is no constitutional requirement of any >

particular racial balance in each school; but in the elimination of the

vestiges of state-imposed segregation, there is a heavy presumption against

L\toWrtej

the persistence of schools substantially disproportionate, |ln Their relevant

student and faculty racial mixes. Defendants bear a heavy burden to justify

the existence of such public schools anywhere in the City of Detroit and

the immediate metropolitan area. The existence of present school attendance

boundaries, including those coincident with school district boundaries,

serve as no justification; indeed, they are a primary means used by the

State to impose segregation.

Although defendants have wide discretion in formulating a plan of

school operation consistent \7ith the lifth amendment affirmative obligation,

some further guidelines from this Court may be helpful. The assignment of

s^'dv.vd'i^lstudents and faculty (and jequalization of facilities and resources for schools

to which children in plaintiff class may be assigned) may not be obstructed

by those local governmental instrumentalities and boundaries which, now

happen to exist. Although such instrumentalities may serve an important

interest of the State in both bringing school government closer to the people

and enabling the State to carry out its function of education, their existence

in the -present form is not compelling and, in view of the variety of alter

natives available which would both permit the State to promote those interests

and at the same time eliminate school segregation, is not an adequate justi

fication for the continuation of segregation in the public schools. As

students, faculty, and resources must be assigned and allocated to eliminate

the last vestiges of state-imposed segregation, the existing jurisdictional

• •

- 5 -

boundaries of local school government (including the decentralized regions)

will have to be crossed or in the alternative altered.

Defendants may wish to maintain existing jurisdictions and merely

operate the schools to which plaintiffs and their faculty are assigned under

cooperative contracts as a unitary school system. Or the defendants may

wish to alter and reorganize the present system and territories of delegating

responsibility for the State function of education to form new local govern-

3/mental instrumentalities,*" For example, if the State deems decentralization

(local instrumentalities serving 200,000 persons) an important interest,

pie-shaped school districts emanating from the center city may be created.

If the State deems community control (school government importantly

influenced by the children, parents and staff in attendance at a particular

school) important, substantial power may be given to the individual school.

If the State deems choice among schools or curriculum important, the State

may permit such choice, but only within constraints that guarantee no

school will have a racial mix substantially disproportionate from that of

the system. The division of power, authority and responsibility among

such instrumentalities, or between such instrumentalities and the State

and any systemwide school government (a successor to the Wayne County

Intermediate School District or a tri-county school district), is properly

within the discretion of defendants. But in no event may such governance

or choice arrangements serve as any barrier to or justification for segregation

and inequality in the schools. Any suggestions here made as to possible

governance arrangements are merely thoughts on the possible; the political

and administrative structure the State chooses to implement to assist in

carrying out the education function are matters properly left to the State

1/ The State’s power and ability to alter governmental structures is clearly

shown by the "decentralization" of the Detroit public schools. That

decentralization created 8 regional school boards with specified powers

under the umbrella of the City-wide school district. Those eight regional

boundaries, of course, may not serve as barriers to desegregation; neither

may the actions of the regional boards. As set forth more fully In the

attached findings of fact and conclusions of law, the regional boards,

boundaries, and authority as implemented have served not only to perpetuate

previously existing school segregation but also to affirmatively segregate

the school system further. Depending on the general plan submitted,

defendants may wish to reconsider the existing jurisdiction of the regional

boards and decentralization in general; In any event, defendants must

propose a plan which effectively eliminates any actual or potential ob

structions the present regionalization may have to the elimination of the

state-imposed segregation.

within the broad confines of the Federal Constitution.-*^

The job of righting past wrongs is difficult; but it is commanded by

Constitution and truly is long overdue. With the assistance of defendants,

careful planning, and the understanding and will of a basically good

people, the transition to a unitary school system may proceed immediately

with as few hardships as accompany any major change. The 14th amendment

will countenance no less than full equality for all peoples in the public

schools of this State now and hereafter. To that task defendants must now

firmly and with single-minded purpose direct their attention and effort.

j j / Under present State law procedures exist for the State Board of Education

to evaluate intermediate and local school district organization and

operation and for school districts (local or intermediate) to merge,

reorganize, consolidate, or annex. See, e.g., M.C.L. ss. 3/j.0.442,

340.291, 340.401, 340*431* Such procedures may serve as possible guide

lines for any reorganization and evaluation contemplated or necessary

in the svibmission of a plan. Insofar as any of the procedures under state

lav; envision some consent by a majority of the electors in any particular

area, such electoral consent is not necessary and cannot stand in the way

of the full vindication of plaintiff’s rights in this cause. Swann.

Cooper. Monroe. Haney at 923*

5/ To assist in that task plaintiffs may wish to retain experts at defendants*

expensee t0/ examine any plan submitted by defendants and/or draw up a

separate proposal. The Court will oversee any arrangement and expenses

to insure that they are reasonable. We must all bear in mind, however,

that cost at this stage in the proceeding is a small matter compared

with the deprivation of £«MB4-**-rights in the past and the need to prepare

adequately and fully for the future so that such wrongs do not ag&in

occur.