Suggestion of Subsequently Decided Authority

Public Court Documents

February 24, 2000

3 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Suggestion of Subsequently Decided Authority, 2000. a7b30f59-e90e-f011-9989-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4c1a0939-e5eb-4e8b-893b-27e6089d9494/suggestion-of-subsequently-decided-authority. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

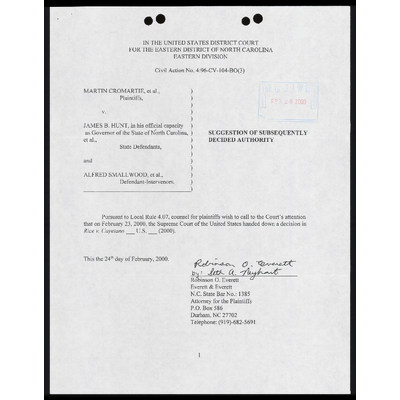

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

EASTERN DIVISION

Civil Action No. 4:96-CV-104-BO(3)

MARTIN CROMARTIE, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

V.

JAMES B. HUNT, in his official capacity

as Governor of the State of North Carolina,

et al.,

SUGGESTION OF SUBSEQUENTLY

DECIDED AUTHORITY

State Defendants,

and

ALFRED SMALLWOOD, et al.,

Defendant-Intervenors.

N

w

N

a

N

a

N

e

N

a

N

w

N

a

N

a

N

a

N

a

N

a

N

a

N

a

N

a

N

o

”

Pursuant to Local Rule 4.07, counsel for plaintiffs wish to call to the Court’s attention

that on February 23, 2000, the Supreme Court of the United States handed down a decision in

Rice v. Cayetano U.S. (2000).

This the 24™ day of February, 2000. Retrao © RE -

Pr 0. Evers

Everett & Everett

N.C. State Bar No.: 1385

Attorney for the Plaintiffs

P.O. Box 586

Durham, NC 27702

Telephone: (919)-682-5691

Williams, Boger, Grady, Davis & Tuttle, P.A.

by:

Martin B. McGee

State Bar No.: 22198

Attorneys for the Plaintiffs

P.O. Box 810

Concord, NC 28026-0810

Telephone: (704)-782-1173

Douglas E. Markham

Texas State Bar No. 12986975

Attorney for the Plaintiffs

333 Clay Suite 4510

Post Office Box 130923

Houston, TX 77219-0923

Telephone: (713) 655-8700

Facsimile: (713) 655-8701

Robert Popper

Attorney For Plaintiffs

Law Office of Neil Brickman

630 3 Ave. 21% Floor

New York, NY 10017

Telephone: (212) 986-6840

Seth Neyhart

Attorney For Plaintiffs

N7983 Town Hall Road

Eldorado, WI 54932

Telephone: (920) 872-2643

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that I have this day served the foregoing Suggestion of Subsequently Decided Authority

by mail to the following addresses:

Ms. Tiare B. Smiley, Esq.

Special Deputy Attorney General

North Carolina Department of Justice

114 W. Edenton St., Rm 337

P.O. Box 629

Raleigh, NC 27602

Phone # (919) 716-6900

Mr. Adam Stein

Ferguson, Stein, Wallas, Adkins, Gresham, Sumter, P.A.

312 W. Franklin St.

Chapel Hill, NC 27516

Phone # (919) 933-5300

“Mr. Todd A. Cox

NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.

1444 Eye Street, NW 10" Floor

Washington, DC 20005

This the 24™ day of February, 2000

bie Jf A. Fife

ed

Robinson O. Everett

Attorney for the Plaintiffs