Calhoun v. Cook Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

July 26, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Calhoun v. Cook Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1972. c227cb7b-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4c32b8d0-f316-40c3-975a-479e8d3008d3/calhoun-v-cook-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

/

■» V

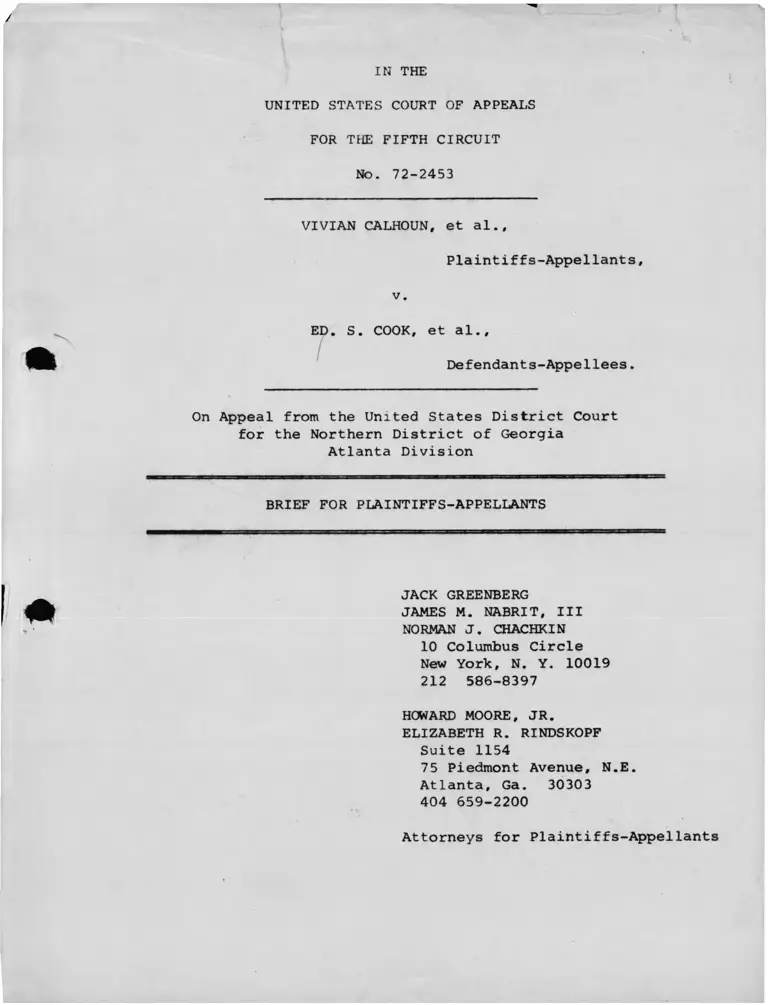

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 72-2453

VIVIAN CALHOUN, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

ED. S. COOK, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Georgia

Atlanta Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

212 586-8397

HOWARD MOORE, JR.

ELIZABETH R. RINDSKOPF

Suite 1154

75 Piedmont Avenue, N.E.

Atlanta, Ga. 30303

404 659-2200

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

I

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 72-2453

VIVIAN CALHOUN, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

ED. S. COOK, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Georgia

Atlanta Division

CERTIFICATE REQUIRED BY

FIFTH CIRCUIT LOCAL RULE 13(a)

The undersigned, counsel of record for plaintiffs-

appellants, certifies that the following listed parties have

an interest in the outcome of this case. These representa

tions are made in order that Judges of this Court may evaluate

possible disqualification or recusal pursuant to Local Rule

13(a) .

1. Plaintiffs Vivian Calhoun, et al., represent a class

of Negro parents and their children attending the public school

system of the city of Atlanta and seek desegregation of the

public schools. The original plaintiffs are as follows:

Vivian Calhoun, Cornetha Calhoun and Fred Calhoun,

infants, by Willie Calhoun, their father and next

friend;

Cornell Harper, Jessie Lee Harper, Betty Jean Harper

and Frank Harper, infants, by Henry J. Harper, their

father and next friend;

Leanard Jackson, Jr., Cecelia Jackson, Phyllis Jackson

and Reba Jackson, by Leanard Jackson, Sr., their

father and next friend;

Betty Jean Winfrey, Jenning Winfrey, Melvin Winfrey,

Sharon Winfrey and Doris Winfrey, by Roosevelt Winfrey,

their father and next friend;

Juanita Fears and Johnny Fears, by Johnny Fears, Sr.,

their father and next friend;

Onitha Putnam and Cloud Putnam, by Dock Putnam, their

father and next friend;

Ernest Swann and Charles Swann, by Ralph Swann, their

father and next friend;

James Lester and William Lester, by David Lester,

their father and next friend;

Sandra McDowell and Snowdra McDowall, by Hudie

McDowell, their father and next friend;

Delane Jenkins and Marion Jenkins, by Mrs. Ruth

Smith, formerly Mrs. Ruth Jenkins, their mother and

next friend.

2. Plaintiffs-intervenors allowed by order of November 22,

1967, are as follows:

Mrs. Precious Griggs, mother and next friend of

Precious Wanda Griggs;

2

Edward Moody, father and next friend of Teireione

Michaelel Moody, Ronald Moody, Rhonda Moody, Arlene

Denis Moody, Muriel Avon Moody, Sharon Elaine Moody,

Carolyn Moody and Daisey Marie Moody;

Leroy Bowden, father and next friend of Sheryl Ann

Bowden;

Mrs. Gweldolyn Coggins, mother and next friend of

Joseph Coggins and Yvonne Coggins;

Reverend P. C. McCollum, father and next friend of

Ph^i®tto McCollum, Lerna LaFay McCollum, Gary Bernard

McCollum, Travis Veshun McCollum and Anita Yvonne

McCollum;

Mrs. Catherine Simpson, mother and next friend of

Patricia Simpson, Jacquelyn Simpson and Angela Marie

Simpson;

John Browner, father and next friend of Shelia Browner;

Reverend Howard W. Creecy, Sr., father and next friend

of Howard W. Creecy, Jr., Gardner Creecy and Candace

Creecy;

Reverend Ralph Abernathy, father and next friend of

Juandalyn Abernathy, Donzaley Abernathy and Ralph

Abernathy, III;

Elmore Keith, father and next friend of Artis Keith;

Howell Hester, father and next friend of Claire Hester;

Louis Johnson, father and next friend of Michael Johnson;

Jake Rowe, father and next friend of Jose Rowe;

George Williams, Jr., father and next friend of Sylvia

R. Williams;

Mary Francis Henderson, mother and next friend of Ingrid

Henderson and Corliss Henderson;

Jesse Hill, Jr., father and next friend of Nancy Hill

and Azira Hill;

Runette Bowden.

3

3. The defendants are:

John W. Letson, Superintendent of Schools

The City of Atlanta Board of Education by and through

its members:

June Cofer, Mrs. LeRoy Woodward, Asa G. Yancey,

Charles L. Carnes, Jerry Luxemburger, Howard E.

Klein, Benjamin E. Mays, J. Frank Smith, Jr.,

J. A. Middleton, William J. VanLandingham.

James M. Nabrit, III

Attorney of Record for

III

(Plaint if fs-Appellants

4

Issues Presented ......................................... 1

Statement of the C a s e ................................... 4

Statement of Facts:

I. Present Status and History of School Desegrega

tion in Atlanta - Pupils and Faculty........... 10

A. Total Enrollment ............................ 10

B. Statistics on Racial Separation of Pupils -

1971-1972 10

C. School Segregation Index ................... 12

D. Present Assignment Methods ................. 13

E. Individial Segregation History of the 83

Current Black Schools in Atlanta ........... 16

F. The Interrelationship between Housing Segre

gation Caused by State Action and School

Segregation in Atlanta ...................... 19

G. Faculty Segregation ........................ 26

H. Staff Discrimination ........................ 29

II. Facts on Plaintiffs' Proposed P l a n ............. 31

A. The Plan Was Prepared by a Competent Expert 31

B. General Approach of the P l a n ............... 31

C. Detailed Explanation of P l a n ............... 33

1. Elementary Schools ...................... 33

2. Middle Schools and Junior Highs . . . . 35

3. High Schools............................ 35

I N D E X

Page

i

Page

D. Transportation Under Plaintiffs' Plan . . . 36

1. Number of Pupils Transported ............. 36

2. Time and D i s t a n c e ......................... 38

3. Comparison of Busing Distances ......... 39

4. Present Busing - 39,000 Daily Rides . . 40

(a) Special Bus Service.................. 41

(b) Contract B u s e s ...................... 42

(c) Student Riders on Regular Bus Routes 42

5. Use of Busing to Segregate Pupils . . . 43

6 . National School Bus Statistics ......... 44

7. Cost of Busing Under P l a n ................ 45

E. Facts on the "White Flight" I s s u e ............. 46

F. Dr. Stolee's Proposed Staff Desegregation

P l a n ............................................ 52

ARGUMENT:

I. The Atlanta Public School System Is in Violation

of the Fourteenth A m e n d m e n t ...................... 54

A. Pupil Assignments ............................. 54

B. Faculty and Staff Assignments ................ 61

II. The Court Should Order Implementation of Plain

tiffs' P l a n ........................................ g3

m * Plaintiffs' Faculty and Staff Desegregation Plan

Should Be Implemented ............................. 59

Conclusion.............

Cases;

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396 U.S.

19 (1969)......................................... 66

Allen v. Board of Public Instruction of Broward County,

Fla., 432 F. 2d 362 (1970)........................ 58

Anthony v. Marshall County Board of Education, 409 F.2d

1287 (5th Cir. 1 9 6 9 ) ............................ 68

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953)................. 21

Bowen v. City of Atlanta, 159 Ga. 145, 125 S.E. 199

(Ga. 1 9 2 4 ) ............................ 21

Brewer v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, Va.,

456 F.2d 943 (4th Cir. 1972), cert, den., ___

U.S. ___ (1972) [40 U.S.L. Week 3 5 4 0 ] ........... 59

Brewer v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37

(4th Cir. 1 9 6 8 ) .................................. 60

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) . . . . 69

Brown v. Board of Education of the City of Bessemer,

___ F.2d ___ (5th Cir. 1972) [No. 71-2892,

July 11, 1 9 7 2 ] .................................. 59

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 ( 1 9 1 7 ) ................... 21

Calhoun v. Cook, 443 F.2d 1174 (5th Cir. 1971) . . . . 13,54

Calhoun v. Cook, 5th Cir. No. 71-2622 .............. 4,9,25,63

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board, 396 U.S.

290 ( 1 9 7 0 ) ..................................... 65,66

Clark v. Board of Education of Little Rock School

District, 449 F.2d 493 (8th Cir. 1 9 7 1 ) .......... 38

Colorado Anti-Discrimination Com. v. Continental Air

Lines, 372 U.S. 714 (1963)..................... 70

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Page

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958)...................... 69

Crow v. Brown, 5th Cir. No. 71-3466, decided March 15,

1972, affirming Crow v. Brown, 332 F. Supp. 382

(N.D. Ga. 1 9 7 1 ) ................................ 23

Dandridge v. Jefferson Parish School Bd., 456 F.2d 552

(5th Cir. 1 9 7 2 ) ................................ 17,57

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 402 U.S. 33 (1971) ............... 55,58,59,64

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 430 F.2d 883 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 0 ) ........... 55

Dooley v. Savannah Bank and Trust Co., 199 Ga. 353,

34 S.E.2d 522 (Ga. 1 9 4 5 ) ........................ 21

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp.

971 (W.D. Okla. 1955), aff'd, 375 F.2d 158

(10th Cir.), cert, denied, 387 U.S. 931 (1967) 60

Flax v. Potts, ___ F .2d ___ (5th Cir. 1972) [No. 71-2715,

July 14, 1 9 7 2 ] .................................. 57

Glover v. City of Atlanta, 148 Ga. 285, 96 S.E. 562

(Ga. 1 9 1 8 ) ....................................... 21

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968) 54,56

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dist.,

409 F .2d 682 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, den.,

396 U.S. 940 (1969) 61

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction of Plam Beach

County, 258 F.2d 730 (5th Cir. 1 9 5 8 ) ........... 60

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400 (1968) . 72

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 ( 1 9 4 8 ) ................. 21

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District,

419 F . 2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 0 ) ........... 28,29,63,70

Page

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) ............. 5,55,56,58,59,63,64,65

66,67,69,70

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

431 F .2d 138 (4th Cir. 1970), aff'd insofar as

it affirmed district court, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) 61

Thorpe v. Durham Housing Authority, 393 U.S. 268 (1969) 72

United States v. Board of Education of Baldwin County,

Ga., 423 F . 2d 1013 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 0 ) ............. 65

United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School

District, ___ F.2d ___ (5th Cir. 1972)

[No. 71-2773, April 1, 1 9 7 2 ] ................... 59

United States v. Hinds County School Board, 443 F.2d 611

(5th Cir. .1970) 5

United States v. Montgomery County Board of Education,

395 U.S. 225 (1969) 70

United States v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education,

___ U.S. ___ (1972) [40 U.S.L. Week 4817] . . . 67

Statutes;

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title V I ...................... 29

Emergency School Aid Act, Public Law 92-318 (June 23,

1972), Section 7 1 8 ................................. 27,71

42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1983 ................................ 29

42 U.S.C. § 2000e as amended............................ 29

Constitution of Ga., Art. VII (Ga. Code Ann.

§§ 2-8601 - 2-8605) 41

Ga. Code Ann. § 32-618 (d) .............................. 37

Ga. Code Ann. § 68-616.................................. 44

v

Georgia Laws 1 9 7 1 ........................................ 41

Georgia Laws 1966 41

Georgia Laws 1965 41

Other Authorities;

Federal Housing Authority Underwriting Manual (1938) . . 23,24

Taeuber and Taeuber, Negroes in Cities (1969) ......... 19

Page

vi

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 72-2453

VIVIAN CALHOUN, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

ED. S. COOK, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Georgia

Atlanta Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

ISSUES PRESENTED

1. Whether the Atlanta, Georgia public school system is

in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment's prohibition against

racially segregated dual systems and the requirement of the

"greatest possible degree of actual desegregation" where:

a. More than three-fifths (61.5%) of all black children

(44,449 out of 72,321) are assigned to schools which are 99%-100%

black and four-fifths (82.5%) are in schools more than 90%

black;

b. The school board has declined to pair any schools

(either contiguous or non-contiguous) regardless of the dis

tances involved;

c. The school board has declined to utilize non-contiguous

zones with or without transportation by school buses as a

desegregation device;

d. The vast majority of the 83 all-black schools were

originally established as such or were converted from all-

white to all-black by board action; many present day all-black

schools were established as such before the first token desegre

gation steps began (40 prior to 1962); and the so-called

"resegregation" process cannot possibly account for present

segregation since only a handful of present all-black schools

were once integrated;

e. Black teachers are now, and have always been, more

concentrated in schools with predominantly black pupils and

white teachers are now and always have been concentrated in

white pupil schools;

f. The housing segregation which makes school desegregation

more difficult in Atlanta was caused, created and maintained by

city (including school board), state and federal governmental

2

action in violation of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments;

included among many facets of such housing discrimination is a

Pattern of public low income housing units which were racially

restricted and segregated by law and were built in conjunction

with nearby segregated schools planned by the school board to

accommodate the legally segregated housing units.

2. Whether, assuming the Atlanta system has failed to

remedy the constitutional violation, the plaintiffs' proposed

pupil assignment plan, which would eliminate all one-race

schools by various established school desegregation techniques

(including simple rezoning, various contiguous and non-con-

tiguous pairings of schools, and transportation), should be

ordered implemented where:

a. The district court found the plan "workable" and

"'feasible' in the sense that it apparently is a sound approach

to the problem of redistributing both Black and white pupils

on a equal basis so as to create a more nearly perfect racial

mix" (R. 675);

b. But the district court rejected the plan as unreason

able because he found that there was no constitutional violation,

and because of the court's prophecy that implementation would

cause so many white pupils to leave as to create an all-black

school system.

3

3. Whether plaintiffs' proposed faculty and staff

desegregation plan should be adopted where the school board has

never eliminated the concentration of black teachers in black

schools and white teachers in white schools.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On October 21, 1971, this case, in which Negro plaintiffs

have sought since 1958 to obtain the desegregation of the

Atlanta, Georgia public school system, was remanded by the

court of appeals to the district court for further fact-finding

on specified issues. Calhoun v. Cook, 5th Cir. No. 71-2622.

The brief of appellants in No. 71-2622 describes the long his

tory of the case. This Court’s October 21, 1971, order directed

(a) that plaintiffs be given a reasonable opportunity to

present and support in the district court an alternate and

superior plan to desegregate the Atlanta public school system;

(b) that the district court supplement the record on

appeal with findings and conclusions as to the viability and

efficacy of plaintiffs' plan;

(c) that the district court "shall additionally consider

and make supplementary findings of fact and conclusions of law

on the wide range reevaluation of the Atlanta school system

described in the paragraph of its opinion of July 28, 1971,

entitled 'Comment'";

4

(c3) that the portion of th© opinion of th© district court

of July 28, 1971, stating that the case shall stand dismissed

on January 1, 1972, is vacated and that during the next three

school years the school district shall be required by the dis

trict court to file semi-annual reports similar to those

required in United States v. Hinds County School Board. 443

F.2d 611, 618-619 (5th Cir. 1970).

On December 30, 1971, plaintiffs filed their proposed plan

accompanied by a "Motion for Adoption of Plaintiffs' Proposed

Desegregation Plan and for Other Relief" (R. 561-587). Plain

tiffs reported that they were submitting a plan (R. 564)

prepared by Dr. Michael J. Stolee, Professor of Education and

Associate Dean at the School of Education of the University of

Miami.

Plaintiffs’ motion alleged that the Atlanta system had

not achieved the "greatest possible degree of actual desegrega

tion and continues to have a large number of one-race schools

which are the result of the historic pattern of racial segre

gation. It alleged that Atlanta schools may be desegregated by

use of the techniques in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971), and that desegregation of

Atlanta was feasible and practical. It alleged that plaintiffs'

plan would achieve the greatest possible degree of actual

5

desegregation and eliminate all one-race and substantially dis

proportionate schools and that it was not justifiable to adopt

a plan accomplishing less desegregation. It alleged that

plaintiffs' plan was designed to treat white and black pupils

equitably insofar as it requires transportation, and that any

adequate desegregation plan must be designed to treat all

racial groups on a fair and equitable basis.

Plaintiffs' motion prayed, inter alia, that the court

(1) enter an injunction ordering that the board implement plain

tiffs' proposed plan and that the board "make any adjustments

and reassignments as may be necessary periodically to continue

the school system on a desegregated basis without racially

identifiable schools and one-race schools"; (2) enter an

injunction ordering defendants to implement plaintiffs' proposal

with respect to desegregation of faculties and administrative

staffs; and (3) in the event the court disapproves plaintiffs'

plan in whole or in part, that it require that defendants imple

ment a plan "which achieves the same degree of actual desegrega

tion as would be achieved by plaintiffs' proposed plan."

On or about March 29, 1972, the defendants filed their

"Response to Plaintiffs' Alternate Plan for Further Desegrega

tion" (R. 602-615). The response alleged that the Atlanta public

school system serves approximately 100,000 pupils; that the

6

school population is presently 73% black and 27% white; that

in the 1970-71 school year the system lost about 7,000 white

pupils from the preceding year and in the 1971-72 year the

system lost about 5,100 white pupils from the preceding year;

that the system "since 1872 has never transported a single stu

dent, owns no buses and receives no state aid for transporta

tion"; that based on information furnished by each principal

the "private" Atlanta Transit System arranges routes to

accommodate students at reduced fares; that the system has a

majority-to-minority transfer provision and furnishes free

transportation to those pupils;that presently about 1,750

pupils are taking advantage of this majority-to-minority transfer

provision. The defendants alleged that plaintiffs' plan would

require the busing of 50,000 pupils at an annual cost of

$2,954,168 "in a school system that has never provided busing

and never used busing to establish or perpetuate segregation."

The response argued there is a distinction between Atlanta and

other systems ordered to bus by federal courts in that Atlanta

"is different because there are no existing transportation facil

ities and because there is no state imposed segregation"; that

obtaining the estimated $2,954,167 to operate the buses "is next

to impossible"; that wherever there are schools in Atlanta which

are predominantly of one race "this result has been caused by

7

factors completely beyond the control of school authorities";

that "the major factor is the migration of children to private

or suburban schools"; and that the present plan of assignment

in Atlanta "complies with the Federal Constitutional require

ments." The response said that on March 27, 1972, the board

adopted a report submitted by a board committee stating "that

mandatory mass bussing of pupils in Atlanta is unworkable and,

in fact, will not achieve the desired results of ourselves orythe plaintiffs."

Thereafter, the court on May 3-4, 1972, heard evidence

offered by the parties. (See Transcript, R. 29-557.) (While

Judge Henderson also signed the subsequent opinion, Chief Judge

Smith sat alone at the evidentiary hearing.) Plaintiffs

1/ The board's pleading also reported adoption of recommenda

tions that the system increase the number of blacks in key

positions; that a resource committee of interested citizens be

appointed in each school area to consult with the area superin

tendent; that a new position of associate superintendent be

created with the first appointment being filled by a black per

son; that new positions be created for blacks on the admin

istrative staffs; that "an outside professional group" be

selected to appraise the entire system; that the system increase

its efforts in the reading program; that the board establish

certain unique high schools and middle schools to be city

wide schools; that it is the policy of the board to maintain

integrated faculties and administration; that the board has on

numerous occasions adopted an open housing position and believes

this is the only ultimate solution to an integrated school pro

gram; that this action program should be accomplished by or

before December 31, 1973; and that greater effort be made to

increase the number of majority-to-minority transfers.

R. 610-614.

8

subsequently filed detailed proposed findings and conclusions

(R. 616-665). On June 8, 1972, the court filed an opinion

(R. 666-682) concluding that plaintiffs' plan is "rejected."

In summary, the court decided that the school board satisfied

constitutional requirements with respect to both faculty assign

ments and pupil assignments. The court held that "Atlanta has

long since been a 'genuinely nondiscriminatory' unitary system;

because it has been a 'de facto' city since at least 1967";

that "its imperfection is due to causes beyond the control of

the Board; because no 'state action' is involved any longer"

(R. 681). The court found that plaintiffs' plan is "workable"

and "feasible" (R. 675) but rejected it on the ground that a

busing plan would cause white flight and"Atlanta will most

likely evolve into an all-black system if the plaintiffs' plan

for busing is adopted" (R. 681).

On June 23, 1972, the district court entered an order

directing that its findings be certified to this Court in

response to this Court’s order of October 21, 1971, in 5th Cir.

No. 71-2622, and also denying plaintiffs' motion for an injunc

tion ordering implementation of plaintiffs' plan (R. 684). The

same day, June 23, 1972, plaintiffs filed notice of appeal from

the orders of June 8 and 23, 1972 (R. 683).

9

STATEMENT OF FACTS

I• Present Status and History of School Desegregation

in Atlanta - Pupils and Faculty.

A. Total Enrollment

During 1971-72 the Atlanta system operated 155 schools

w ith 100,174 pupils. There were 126 elemeritary (grades K-7)

and 29 secondary schools (grades 8-12), including 3 middle

schools (grades 6-8) and one junior high (grades 7-9) Ex

2/

P-16.

In the fall of 1971 black pupils were 72.2% of the enroll

ment .

Negro WhitePupils No. % No. % Total

Elementary 45,452 71.8 17,867 28.2 63,319

Secondary 26.869 72.9 9,896 27.1 36.855

Total 72,321 72.2 27,853 27.8 100,174

B. Statistics on Racial Separation of Pupils - 1971-1972

Atlanta schools are still characterized by a pattern of

separation of black pupils from white pupils. Over four-fifths

2/ Ex. P—16 collects detailed statistics by race for pupils and

staff for 1954, 1955, 1960, 1961 and 1966 through 1971. The

arrangement of the several charts for each year is described in

testimony at R. 166-169, 179-185.

10

of all Negro children attend schools which are 90% or more black

and over three-fifths of them are in schools more than 99% black.

The following chart summarizes the pupil segregation:

Fall 1971

Combined Elementary and Secondary-^/

% Negro

Pupils

No. of

Schools No. Negro Pupils No. White Pupils

100% 23 ) 17,423) 1)

) 83 ) 59,689 (82.5%) ) 757 (2.7%)

90-99 60 ) 42,266) 756)

80-89 5 2,442 (3.4%) 346 (1.2%)

70-79 2 924 (1.3%) 278 (1.0%)

60-69 5 2,111 (2.9%) 1,146 (4.1%)

50-59 4 1,387 (1.9%) 1,105 (4.0%)

40-49 8 2,336 (3.2%) 2,987 (10.7%)

30-39 3 563 (0 .8%) 1,026 (3.7%)

20-29 8 1,930 (2.7%) 5,701 (20.7%)

10-19 8 622 (0.9%) 3,242 (11.7%)

1-9 20 ) 309) 8,354)

Less ) 28 ) 317 (0.4%) ) 11,195 (40.2%)

than 1 8 ) 8) 2,841)

Totals 154 72,321 (100%) 27,853 (100%)

3/ Ex. P-16.

11

In fall 1971 there were 23 schools with 100% Negro enroll

ments which enroll 17,423 black pupils. There were 59 schools

with Negro populations greater than 99%, enrolling 44,449 Negro

4/

pupils. Ex. P-16. At the secondary level, 18,720 black

pupils (69.7%) and at the elementary level, 25,729 black pupils

(26.6%) attended schools more than 99% black. Ibid. Half of

the white elementary pupils and about 20% of white secondary

students attend virtually all-white (90% or more) schools.

Ibicl.

C. School Segregation Index

Plaintiffs' expert witness. Dr. Karl E. Taeuber,

analyzed the history of school desegregation in Atlanta by Vmeasuring it with a pupil segregation index. See Ex. P-50.

Zero represents exact racial balance and 100 represents complete

segregation; thus, before desegregation in Atlanta began in 1961,

the index was 100. Ex. P-50.

4/ Ex. P-16 contains charts similar to that above for elementary

and secondary schools. It also contains parallel charts for

earlier years.

5/ The segregation index is explained in Dr. Taeuber's book,

Negroes in Cities, Ex. P-54, where it was applied to measure

housing segregation. See testimony at R. 248-268.

12

Pupil Segregation Index

School Year Elementary Secondary

1966- 67

1967- 68

1968- 69

1969- 70

1970- 71

1971- 72

Plaintiffs' Plan

97 95

95 92

93 88

91 86

84 81

82 82

15 10

D. Present Assignment Methods

The current system of pupil assignment in Atlanta uses

vattendance zones depicted on three maps. The plan now in

effect was proposed by the board and approved by the district

court March 20, 1970 (Hooper, D.J.). Plaintiffs appealed the

approval and on June 10, 1971, this Court ruled the:

judgment of the district court is vacated and

the cause remanded with directions that the dis

trict court require the School Board forthwith

to institute and implement a student assignment

plan that complies with the principles estab

lished in Swann v. Charlotte-Meeklenburg Board

of Education, ... insofar as they relate to the

issues presented in this case, including but not

limited to the provisions of that opinion rela

tive to a majority-to-minority pupil transfer

option providing for free transportation and

space availability to the transferring student.

Calhoun v. Cook, 443 F.2d 1174 (5th Cir.

1971).

6/ See Ex. P-5 (elementary base map), P-9 (junior high and

middle school base map), P-11 (senior high base map). See

testimony at R. 56, 65, 75-77.

13

Nevertheless, because of subsequent orders in the trial court,

now under review, the 1970 plan, which this Court vacated more

than a year ago, remains in effect.

Atlanta school authorities have restricted their desegre

gation effort to single contiguous zones and the majority-to-

minority transfer plan. Atlanta has never used pairing, grouping,

ynon-contiguous zoning or busing as desegregation techniques.

7/ Although the opinion below states the board has used pairing

(R. 672), this is a plain mistake of fact. The Assistant Super

intendent, Dr. Cook, testified at his deposition (pp. 61-63):

Q Getting back to the issue of the current

pupil assignment practices of the system, I think

we had gone over the zones, and we had gone over

the exceptions to the zones. Is it correct to

state that the system does not use any transporta

tion zones or non-contiguous zones of any kind?

A Yes.

Q By non-contiguous, what I mean is a zone

that is not geographically surrounding the school

that it serves.

A Yes.

Q Would it also be accurate to state that the

system does not combine more than one school in a

zone or use a grade structure system, whereby ---

A We don't pair, yes.

Q You don11 have any pairing?

A That's right.

* * *

(continued)

14

Currently each school has an attendance area surrounding the

8/

school, and with some exceptions, pupils are directed to the

school in their zone of residence. The board’s attendance areas

vary greatly in size from small walk-in zones to huge areas where

many pupils live miles from the schools to which they are

assigned.

7/ (Continued)

Q Is there any policy statement on this

issue by the board that you know about or recall,

whether or not you used pairing or whether or not

you used contiguous zones?

A No. Obviously we have not done it, so this

is not our policy.

Q Was that policy based on staff recommenda

tions, or what?

A There is no written policy about it. We

just haven't done it. We do not have a policy

against it; we simply have not done it.

See also colloquy at R. 80-81.

8/ Exceptions to the attendance zone assignments are handicapped

children, children in special schools, children transferred

under the court ordered majority-to-minority race transfer plan,

children moved ror administrative reasons including disciplinary

reasons, and children who were enrolled in a sequence of courses

at a school prior to the zones who would otherwise have been

moved to a school without the same course. (See Cook Deposition

of March 16, 1972, pp. 48-50.)

15

E. Individual Segregation Histories of the 83

Current Black Schools in Atlanta.

The vast majority of the 83 schools with pupil popula

tions over 90% black were established as all-black schools under

the dual system. Exhibit P-45(a) lists 40 such schools which

were all-black in 1962 before any desegregation and are still

virtually all-black. See also R. 199-200, 205, 209. Exhibit

P-46 lists 13 schools which were converted from all-white to

all-black by the school administration prior to 1966 (R. 200-

202, 205, 209). Exhibit P-46 lists 55 schools which always

have been more than 90% black schools.

Exhibit P—17 contains a separate enrollment history by race

for each school in Atlanta. A study of the 83 schools which are

now 90% or more black indicates that:

9/

1) 59 schools have always been over 90% black;

2) 12 schools were administratively converted from 100%

10/

white to all-black during operation of the dual system;

3) only 12 schools have changed from less than 90% black

9/ See Ex. P-46 which lists 53 such schools. Carver High School

has also always been 100% black and should be included in the

list in Ex. P-46. See also Blalock, Drew and Adamsville schools

which opened in 1971 as all-black schools. Ex. P-17.

10/ See Ex. P-46, p. 2. (A thirteenth school, East Lake, was

79% black in 1966.)

16

to more than 90% black since 1966. Of these 12 schools, 7

became over 90% black by 1969 during operation of the board's

freedom-of-choice plan. The others became over 90% black in

1970 or 1971 under the board's current attendance areas.

The opinion below unaccountably refers to "vast numbers"

of "resegregated" schools (R. 681).

Here we have vast numbers of schools which have

been desegregated and then resegregated by shift

ing population trends. Cf. Dandridge v. Jefferson

Parish School Bd.. 456 F.2d 552 (5th Cir. 1972).

We submit the finding is clearly erroneous. The court cites no

details to support the assertion. The cold fact of the indi

vidual school enrollment histories (Ex. P-17) analyzed in the

prior discussion simply is that there are no more than a dozen

schools in Atlanta to be even discussed in the category of

12/

"resegregation." No others have gone from all-white (90% plus)

11/

11/ These 12 schools include 8 elementary schools (Arkwright,

Beecher Hills, Burgess, Connally, East Lake, Gilbert, Harris,

Rusk and West Manor) and 3 secondary schools (Brown, Hoke Smith

and Southwest). Ex. P-17.

12/ The only school board showing on "resegregation" is a 1971

affidavit by Supt. Letson (see Record in 5th Cir. No. 71-2622)

which asserted that 17 schools had become resegregated since

1961. This is hardly a "vast number" in Atlanta, but few of

the 17 meet any definition of "resegregation" since few were

ever integrated. Elementary school desegregation did not even

begin in Atlanta until 1965. Analysis of the Superintendent's

list of 17 "resegregated" schools by reference to the individual

enrollment histories in P-17 shows the following:

17

during the period since all grades in the system were desegre

gated. All of the so-called "resegregation" took place under

the regime of the very same pupil assignment policies which are

challenged in this appeal: some were "resegregated" under

freedom of choice and the rest under the current school zoning

plan. Most schools have never been integrated in the first

place as the enrollment history exhibits amply demonstrate school

by-school and year-by-year. See Ex. P-16 and P-17.

Testimony at hearings several years ago by Superintendent

Letson and others established that the school board frequently

converted all-white schools into all-black schools, transfer

ring segregated pupils and faculties into and out of a building

12/ (Continued)

1. 4 schools which were shifted from all-white to all-black

between 1954 and 1961: Capital Avenue, Fain, Mayson and

Whitefoord.

2. 6 schools which were converted from all-white to all

black between 1961 and 1966: Carey, Center Hill, Kirkwood,

West Haven, Murphy High and Fulton High.

3. 1 school which opened all-black in 1966 or 1967: Grove

Park.

4. 6 remaining schools which were briefly desegregated

before becoming black: Beecher Hills, Burgess, Connally, Gilbert

and Westminster. East Lake (79% black in 1966) may also belong

in- this group. Almost all of these schools became resegregated

under the free choice procedure in effect prior to 1970 when

white pupils were permitted to transfer out to attend white

schools and avoid schools with blacks.

18

en masse. See Exhibits P-41, P-42 and P-43. The most dramatic

evidence of the practice of "converting" schools from white to

black is the testimony about Kirkwood school. Ex. P-43 shows

that Kirkwood was 100 percent white— students and faculty—

prior to January 25, 1965. On that date, in the middle of a

school year, 400 Negro pupils and a complete black faculty were

moved in and 334 out of 340 white pupils were transferred out,

along with all of the white staff, except the principal, secre

tary and cafeteria manager. Ex. P. 43; R. 201-202.

F. The Interrelationship between Housing Segregation

Caused by State Action and School Segregation in

Atlanta.

A comprehensive study and measurement of residential

segregation throughout the United States was conducted by plain

tiffs' expert witness. Dr. Karl E. Taeuber (see Ex. P-54,

'Negroes in Cities, Residential Segregation and Neighborhood

Change," Taeuber & Taeuber). The high degree of residential

segregation which is "universal in American cities" is also

13/

characteristic of Atlanta. But Atlanta, and southern cities

13/ Dr. Taeuber states;

A high degree of racial residential segregation is

universal in American cities. Whether a city is a

metropolitan center or a suburb; whether it is in

the North or South; whether the Negro population is

large or small— in every case, white and Negro

19

generally, have a significant difference from the northern pat

tern of housing segregation:

This, then, represents a basic difference between

Northern and Southern cities. In most Southern

cities, Negroes have continuously been housed in

areas set aside for them, whereas in the North

most areas now inhabited by Negroes were formerly

occupied by whites. (Ex. P-54, Chapter 1; see

also Chapter 8.)

Racial discrimination is the basic cause of residential

14/

segregation in the Atlanta area. Dr. Taeuber's study and

13/ (Continued)

households are highly segregated from each other.

Negroes are more segregated residentially than

are Orientals, Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans,

or any nationality group. In fact, Negroes are by

far the most residentially segregated urban minority

group in recent American history. This is evident

in the virtually complete exclusion of Negro resi

dents from most new suburban developments of the

past fifty years as well as in the block-by-block

expansion of Negro residential areas in the central

portions of many large cities. (Ex. P-54, Chapter 1)

Dr. Taeuber measured the segregation index for Atlanta:

Residential Segregation Index

Atlanta, 1940-1970______

Year

1940

1950

1960

1970

1970, Atlanta's Suburbs

Segregation Index

87

92

94

92

92

(Ex. P-52)

14/ See generally the testimony of Dr. Taeuber and Mr. Martin

Sloane (R. 241-385). See also Ex. P-54 and P-73.

20

testimony show that it is discrimination rather than poverty or

choice which causes the pattern of Negro residential segrega

tion. (Ex. P-54, R. 299-301)

The pattern of housing segregation in Atlanta was estab

lished by local laws requiring that the races live apart. Even

after such laws were held unconstitutional in Buchanan v.

Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917), Atlanta enforced two ordinances

requiring racial segregation in housing until those laws were

held unconstitutional. See Glover v. City of Atlanta. 148 Ga.

285, 96 S.E. 562 (Ga. 1918), and Bowen v. City of Atlanta. 159 Ga.

145, 125 S.E. 199 (Ga. 1924). It was stipulated that these old

segregation laws set a pattern which still persists today and

that their effects still linger. R. 364-366.

After these laws were struck down, the same result was

achieved in Atlanta by widespread use of racially restrictive

covenants in deeds which were enforced by Georgia courts. The

covenants accomplished the same type of racial zoning previously

maintained by the ordinances. See Dooley v. Savannah Bank and

Trust Co., 199 Ga. 353, 34 S.E.2d 522 (Ga. 1945), indicating that

Georgia law required state court enforcement of racially restric

tive covenants prior to Shelley v. Kraemer. 334 U.S. 1 (1948),

and Barrows v. Jackson. 346 U.S. 249 (1953).

Exhibit P-73 is an account of federal policies on residental

segregation prepared by Martin Sloane, Assistant Staff Director

21

of the United States Commission on Civil Rights, and a housing

expert. Mr. Sloane describes how the Federal Housing Admin

istration (FHA) required the use of racially restrictive

covenants and required segregation in all FHA housing for 13

crucial years after World War II (R. 356-358). FHA played a

central role, both nationally and in Atlanta, in establishing

the present pattern of residential segregation. Many federal

agencies contributed to residential segregation, including the

Federal Home Loan Bank Board, the Homeowners Loan Corporation,

Comptroller of the Currency, Federal Reserve Board and Federal

Deposit Insurance Corporation. Exhibit P-73 also shows how

various fedeia 1 agencies have failed to take any effective action

to change the pattern of housing segregation and indeed continue

to promote housing segregation, even though this is now forbid

den by various federal statutes. Sloane's expert appraisal of

federal housing policy shows that the federal response to the

legal mandate to prevent segregation and discrimination in housing

is generally ineffective and that the goal of equal housing oppor-

tunity remains far from achievement. It also shows that present

federal housing policies and laws offer no hope of integrating

the schools.

The discrimination which has promoted residential segregation

within Atlanta has also set the metropolitan area pattern by which

22

Negroes are excluded from the white suburban communities.

Between 1960 and 1970 the Atlanta city population increased

from 38% Negro to 51% Negro; the population of the Atlanta sub

urbs decreased from 8% to 6% Negro; and the Negro population of

the total metropolitan area was stable at 23% in 1960 and 22%

in 1970. Local government discrimination is partially respon

sible for the confinement of Negroes to cities and their exclu

sion from Atlanta's suburban communities. The Fifth Circuit

recently affirmed a decision so holding in a case involving

housing discrimination by public officials in Fulton County,

Georgia. See Crow v. Brown. 5th Cir. No. 71-3466, decided

March 15, 1972, affirming. Crow v. Brown. 332 F. Supp. 382 (N.D.

Ga. 1971).

Establishment of racially segregated schools under the dual

system influenced Atlanta neighborhoods to become residentially

segregated. Designating schools as black or white or converting

schools from white to black helped shape the pattern of residen

tial segregation around the segregated schools. The construction

of schools designed to serve racially segregated public housing

projects also tended to lock in school segregation and neighbor

hood segregation. The interrelation of dual school systems and

residential segregation is also shown by the Federal Housing

Authority Underwriting Manual (1938, Ex. P-71) which illustrates

23

that FHA's policy of promoting residential segregation was alsoiVinvolved in promoting school segregation.

Dr. Stolee pointed out— and Judge Smith agreed— that the

dual system of schools operated in an important way to segregate

the neighborhoods around the segregated schools:

A Well, when a school is labeled for a given

race, then obviously the people that want to live

in the environs of that school would be members of

the same race; and so while in some ways the school

may have been established because of racial pat

terns of the neighborhood, once it was there then

it contributed to the continuing racial pattern

growth of the neighborhood.

THE COURT: No question about that. (R. 210)

Discrimination was also practiced by the low rent public

housing program, which was operated on a racially segregated

basis by the local public housing agency, the Atlanta Housing

Authority. See Ex. P-44; see also Ex. P-73. It was stipulated

that the Atlanta Housing Authority and the defendant school board

worked "hand in glove" to establish segregated low income public

housing projects and nearby public schools located and con

structed to serve the segregated projects. (R. 370-376) Super

intendent Letson filed an affidavit identifying 29 schools which

were segregated by planning or building schools to serve housing

15/ See the 1938 FHA Underwriting Manual, Section 951.

24

projects which were once limited by law to black occupancy and

16/

are still all-black.

As Dr. Stolee pointed out, it is the school authorities'

decision which established schools adjacent to or within the

16/ See Record in 5th Cir. No. 71-2622. Affidavit of John W.

Letson, filed July 2, 1971:

In the Atlanta system there are twenty-nine

(29) schools that are in what school authorities

call a controlled situation. A controlled situa

tion means that a certain school serves, and often

was built to serve, a federally funded housing pro

ject. According to Executive Order No. 11063 which

follows 42 U.S.C.A. 1982, these housing projects

are supposed to be racially nondiscriminatory and

are to have integrated occupants. If the housing

authorities would obey their own laws and integrate

these housing projects, these twenty-nine (29)

schools serving the projects would have more inte

gration.

The names of these twenty-nine (29) schools that

are in control situations are as follows:

Butler Ware

Campbell Wesley

Carey Williams

Carter Archer

Craddock Price

Drew Washington

Dunbar Blair Village

Gilbert Blalock

Jessie Jones Boyd

M. Agnes Jones Cook

Oglethorpe Dobbs

Pitts Fowler

Robinson Luckie

Slater East Atlanta

Smith

25

housing projects and fixes the ultimate pattern of segregation

by the fashioning of pupil assignment policies to accommodate

the pattern of residential segregation. R. 205-209.

G. Faculty Segregation

In 1971-72 Atlanta public schools employed 4,805

teachers of whom 60% were Negro:

Negro White

Teachers No. % No. % Total

Elementary 1,808.1 62.2 1,097.3 37.8 2,905.4

Secondary 1,118.4 58.9 781.8 41.4 1.900.2

Total 2,926.5 60.8 1,879.1 39.2 4,805.6

There is a continuing concentration of black teachers in

schools with virtually all-black pupils. The faculties in the

system all have some integration and range from a high of 84.6%

Negro (at Howard) to a low of 30.1% Negro (at Dykes).

Plaintiffs' exhibits (Ex. P-16, Ex. P-16 (a) and Ex. P-17),

compare the racial composition of faculty and student bodies of

all Atlanta elementary and high schools. In comparing the racial

distribution of faculty to the racial composition of the student

body of the various schools, a uniform pattern emerges. This

pattern obtained in both years since the March 1970 faculty

desegregation order of the district court. Ex. P-16. In 1970-71

26

*the system-wide percentage of black teachers was 59.7%. ibid.

Of the 24 schools with faculties 70% black or more, all but one

school had student bodies 90%-100% black. Ibid. Of the 20

schools with faculties less than 50% black, all but two schools

had student bodies more than 60% white and six of these schools

had student bodies 90% or more white. Ibid.

During 1971-72, the system-wide faculty ratio was 60.8% black.

Ibid. Thirty-eight schools had faculties over 70% black; all but

one of these were composed of student bodies 90% or more black.

Ibid. Thirty-five schools had faculties less than 50% black and

24 of these schools had student bodies less than 30% black.

Ibid. Schools with a white faculty percentage over the system-

wide ratio are identifiable in all cases as white by the compo

sition of their student bodies. Ibid. Schools with a percentage

of black teachers over the system-wide ratio are uniformly iden

tifiable as black by the composition of their student bodies.

Ibid.

Plaintiffs presented testimony of Mrs. Frances Pauley,

H.E.W.'s coordinator for civil rights compliance reviews under

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Emergency School

Assistance Program (ESAP) for Georgia, Alabama and Tennessee.

(R. 444-482) Mrs. Pauley reviewed Atlanta’s two-year application

for Priority I ESAP funds in the amount of $3,340,044, submitted

27

August 27, 1971. (Ex. P—48) Mrs. Pauley recommended disapproval

of the Atlanta application on September 1, 1971, because of the

system's failure to comply with faculty assignment requirements

°f Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District. 419

F •2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1970), as interpreted by HEW. HEW inter

prets Singleton to require the ratio of minorities to non—minor

ities faculty in all schools to be "substantially similar" to the

ratio in the whole system. "Substantial similarity" as defined

by HEW s rule of thumb" means individual schools must not vary

from the system—wide ratio by more than two teachers and 5%.

R. 449-450. The ESAP review conducted by Mrs. Pauley revealed

that 20 out of the 25 Atlanta high schools, and 24 of the sys

tem's 125 elementary schools were in violation of the Singleton

rule as thus applied. Figures submitted to HEW (Ex. P-48)

showed that, particularly among Atlanta's high schools, variances

from the system—wide ratio by as many as 10 or more teachers were

not unusual (Douglas, Dykes, Harper, Hoke Smith and Therrell).

HEW estimated the need to transfer approximately 140 teachers to

comply with Singleton. Phone conversations and a meeting on

October 13, 1971, were held to explain this fact to Superintendent

Letson and to encourage more faculty desegregation. Superin

tendent Letson was intransigent in his reaction to the HEW request.

Mrs. Pauley testified (R. 464):

28

Q And in your meeting on October 13 with

Dr. Letson, were you willing to, or is it your

policy generally to negotiate or take—

A The door of HEW is always open to

negotiations.

Q So you would have been willing to agree

to consider their application with a transfer of

something less than 140?

A I would say that my superior that day

spent about an hour and a half trying to persuade

Mr. Letson to talk of negotiations and he refused,

he constantly refused, said he could not make a

change of assignment of a single teacher.

The result was that HEW officials in Washington rejected

the ESAP applications and Atlanta lost $3,340,044 in federal

uyfunds. R. 458-459.

H. Staff Discrimination

While not attempting to present a detailed proof of

employment discrimination as warranted under the various civil

rights acts (cf_. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e as amended and 42 U.S.C.

§§ 1981, 1983), plaintiffs presented documentary evidence.

17/ Mrs. Pauley personally supervised or conducted all civil

rights reviews in Georgia, Alabama and Tennessee under ESAP

and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Atlanta was the

only system which refused any attempt to meet HEW's civil

rights requirements. Memphis, Nashville, Chattanooga,

Savannah, Columbus, Macon, Birmingham, Montgomery and Mobile

each successfully met the Singleton test as applied by HEW in

determining civil rights compliance. R. 476.

29

Ex. P-77, demonstrating the lack of black participation in the

educational decision-making and planning processes of the

Atlanta public schools. Blacks are almost totally absent from

decision-making central administrative positions in all but a

few federally-funded programs. Of particular note is the total

absence of blacks from the school system's Educational Broad

casting Department. Blacks appear in that section only in

three cases, a maid, a custodian and a crewman. Throughout

the Central Administrative Staff blacks uniformly are concen

trated in clerical and maintenance positions. While some Central

Administrative Staff positions by definition afford little or no

contact with the student body and educational process (e.g.,

Finance Department, General Accounting, Special Accounts, etc.),

a high number of these positions do directly affect the student

population, either through planning of educational programs and

facilities or through such centrally operated programs as the

aforementioned Educational Broadcasting Department. The absence

of blacks from such Central Administrative Staff positions is

reflective of the fact that as presently operated, Atlanta is

not a "unitary" school system.

30

II. Facts on Plaintiffs' Proposed Plan

A - The Plan Was Prepared by a Competent Expert.

Plaintiffs' plan was prepared by Dr. Michael J. Stolee

who was found "well-qualified in terms of integration problems

and ... [to have] extensive experience in the preparation of

surveys and plans for a number of school districts throughout

18/

this Circuit and elsewhere." (R. 670) His thorough study

included visiting the exterior of each of Atlanta's 155 schools.

19/

(R. 129)

B. General Approach of the Plan.

Dr. Stolee used multiple desegregation techniques,

including single attendance zones (the adjustment of some

boundaries and retention of others), the pairing of schools, the

grouping of three or four schools, non-contiguous attendance

10/ See Ex. P-1, R. 12-13. Dr. Stolee is a recognized expert

in the field of public school administration and school desegre

gation. He has served as a public school teacher, principal,

superintendent of schools, as well as professor of education

at the university level. From 1966-1969 he was director of the

Florida School Desegregation Consulting Center. He has partici

pated in school desegregation studies and surveys in more than

30 communities.

19/ Dr. Stolee studied voluminous documents about the system

(Ex. P-15) and met with the board attorney (Mr. Latimer) and

administrative personnel. R. 128-130.

31

zones, and transportation and attempted to put them all together

in a reasonable way. R. 126-127. The plan seeks to desegregate

the entire system at once and avoid the unsuccessful piecemeal

approach used to date in Atlanta. (R. 118-119) The plan would

eliminate all one-race schools, and assign pupils so that all

schools would more or less reflect the makeup of the community.

Schools would have a range of from about 54% to 87% black

enrollments.

The series of groups and pairs in the plan were designed

to equalize the burden of transferring between black and white

pupils. R. 77-78. The groups were also designed to aim for

equality in the numbers of black and white pupils in the lowest

grades who remain in their home areas. R. 77-78. Of course,

under the plan every pupil spends some elementary grades in his

present home area. R. 80-81.

Dr. Stolee's plan minimizes the number of pupils transferred

within each group. He accomplished this by avoiding a "Princeton

Plan" grade structure and using an alternate method to reduce

the number of transferees but achieve as much integration.

20/

R. 64-66.

20/ Exhibit P-25 illustrates how grade structures are arranged

to significantly reduce the number of pupils reassigned.

32

The plan was designed to relate rationally to local trans

portation arteries. (R. 85-86. There is no "cross-town" busing;

the maximum is "half cross-town" (R. 86) and most trips are much

shorter. The grouping of schools considered the alternatives of

transporting more pupils on shorter rides or accomplishing

similar results by transporting fewer pupils on slightly longer

trips. The decision was to reduce the number of pupils bused

by planning slightly longer rides for those transported.

Dr. Stolee judged that none of the rides would require an exces

sive period, and that all are within distances and times

commonly used in school systems. Plaintiffs' detailed transporta

tion time and distance study is discussed below.

C. Detailed Explanation of Plan.

1. Elementary Schools. The elementary plan has three

parts designated in Exhibits P-2 and P-3 (which show enrollment

projections) as Series I, Series II and Series III. The elemen-

n/tary plan is also illustrated by maps and overlays.

21/ Use these large maps as follows:

a. View P-5 — existing elementary zones.

b. View overlay P-6 over P-5 — Series I.

c. View Overlay P-7 over P-5 — Series II.

d. View Overlay P-8 over P-5 — Series III;

non-contiguous groups are color coded.

33

Series I (R. 26-31) includes 12 schools where present

attendance lines were left unchanged because the schools in fall

1971 were in the general range of the system's racial popula

tion. Projected enrollments in Series I schools range from 55%

to 87% black; only these 12 schools are now within this range.

The board's attendance areas for these elementary schools range

in size from small compact "walk-in" areas to large sprawling

areas where pupils must necessarily be transported to school.

See, for example, the attendance area for Ben Hill, Ex. P-5.

Series II (R. 31-53) desegregates 47 elementary schools by

combining adjoining or contiguous zones and changing the grades

at schools within the newly enlarged area. Typically, one pre

dominantly white and one or more predominantly black schools

22/

are combined in a group. The size of the combined areas in

Group II pairings compares favorably with many existing single

zones now in use. Only a portion of Group II pupils will need

transportation; the estimates are discussed below.

22/ The grouping technique is illustrated by group No. 2 in

Series II involving English Avenue, Haygood and Home Park

schools. Now English Avenue is black and Haygood and Home Park

are white. The plan combines the three adjoining areas into

one attendance area. Under the plan English Avenue School would

serve all pupils in grades 1-3 in the entire three school area

while Haygood and Home Park would both serve grades 4-5. Fourth

and fifth grade pupils in the English Avenue area would be divided

between Haygood and Home Park. Pupils in the Haygood and Home

Park areas would return to their home neighborhoods in grades

four and five. See Ex. P-7 over P-5.

34

Series III uses similar grouping and pairing techniques

with school districts which are not contiguous or adjoining; it

includes 64 schools in 22 groups. R. 83-94. The non-contiguous

groups are arranged to relate to the high school feeder pattern

and to favorable transportation routes.

The projected racial composition of schools in Series II

and III would range between 54% black at Morningside and 86%

black at Pitts and Craddock.

2. Middle Schools and Junior Highs. In 1971-72, Atlanta

had 3 middle schools and one junior high. Dr. Stolee would

desegregate each without disturbing the grade structure by making

23/

boundary changes. See R. 94-104, Ex. P-4.

3. High Schools. Exhibit P-4 gives high school enrollment

24/

projections; the high school plan is explained at R. 104-118.

23/ See Ex. P-4 for enrollment projections. See Maps and Over

lays P-5, P-9, P-10. Use maps as follows:

a. View P-9 — existing junior high and middle zones

b. View overlay P-10 over P-5 (elementarv base map)

to see proposed zones.

24/ Use Maps and Overlays P-5, P-11, P-12 as follows:

a. View P-11 — present high school zones.

b. View overlay P-12 over P-5 (elementary base map)

to see proposed high school zones; non-con-

tiguous areas are color coded. Feeder pattern

shown by noting elementary zones.

35

Redrawing of attendance zones would desegregate ten high schools,

indicated as black outlined areas in map overlay. Ex. P-12,

R. 107-108. Fourteen senior high schools would be desegregated

by establishing transportation zones (non-contiguous zones)

in addition to regular zones surrounding the schools. R. 107-

108. Eleven of these schools would have two separate areas and

three would have three areas.

The high school plan is based on a feeder relationship with

elementary schools so that pupils would remain together through

out elementary and secondary school. R. 110-111. Transportation

patterns for elementary and secondary schools would be similar.

Two pupils in a family at different levels could, if they both,

required transportation, travel in the same direction on the

same bus. R. 111-117.

D. Transportation Under Plaintiffs' Plan.

1. Number of Pupils Transported. The district court

25/

reviewed the parties' conflicting estimates and concluded the

truth was "as is usual ... somewhere in-between":

25/ The parties' differing estimates of the number of pupils

to be transported were because of differing assumptions about

the rules that might govern a future transportation system.

36

... The court concludes that approximately

one—third of the total enrollment or some

33,000 pupils would have to be bused under

the Stolee plan. (R. 673)

The court accepted plaintiffs' basis of deciding eligibility

by whether pupils lived 1-1/2 miles from a school, the distance

being derived from Georgia law. Ga. Code Ann. § 32-618 (d).

The board's estimates based on one mile were rejected.

The difference between the court’s estimate and plaintiffs'

reflect the court s thought that if any free busing is given

equal protection would demand that all pupils living over 1—1/2

miles from school be given free transportation whether or not

they remain at their "neighborhood school" under the plan.

(R. 673) Plaintiffs contended that a workable and fair plan

might provide free buses for only those pupils in non-contiguous

25/ (Continued)

Estimates

Plaintiffs Board

Elementary Schools: Series I

Series II

Series III

0

2,304

12,853

0

6,814

12,402

Junior High and Middle Schools 560 879

High Schools 7,474* 27.670

Total 23,191 47,765

* Total eligible 9,965 less estimated

25% self transportation by auto, etc.

37

areas who would most need transportation and whose present sit-

26/

uation would be most drastically changed. But plaintiffs, of

course, have no objection to a more generous policy which both

the district court and the board preferred if busing is to be

ordered. Plaintiffs merely urge that if busing resources are

at a premium, the minimum number to implement the plan is

smaller.

2. Time and Distance. The court below was "of the view

that transportation for the bulk of the pupils would consume an

average of 35-45 minutes each way in Atlanta traffic, which is

notoriously atrocious during rush hours." (R. 673) We believe

this finding at least slightly overstates the "average" travel

time, but the difference is probably unimportant for present

purposes. Plaintiffs made a thorough over-the-road survey of

the times and distances between the paired schools and non-con-

tiguous zones (Ex. P-39; R. 189-209). The survey checked the

pairs that were farthest apart— the Group III elementary schools

and the non-contiguous high school groups. The closer schools

in Groups I and II and the contiguous high school zones were not

listed in the survey because they were obviously shorter and

26/ See Plaintiffs' Proposed Findings and Conclusions, R. 642.

Plaintiffs cited the Eighth Circuit rule. Clark v. Board of

Education of Little Rock School District, 449 F.2d 493, 499

(8th Cir. 1971).

38

similar to current patterns— but their inclusion would make the

overall average less than that stated by the court.

Plaintiffs' time and distance study (P-39) conducted by

Thomas Harley, was based on driving an automobile at speeds

which simulated bus travel along the routes between paired

schools. Other pairings similar to those tested were also iden

tified. P-39. Harley's speed and routes were cross checked

with Atlanta Transit system experience. R. 226-230. Harley

found that the times and distances between the Group III schools

and non-contiguous high school zones ranged from a high of 46

minutes and 15 miles to a low of 8 minutes and 2.4 miles. The

median trip was about 26 minutes and 9 miles; the average about

26 minutes and 10 miles. (Calculated from Ex. P-39.)

3. Comparison of Busing Distances. The average number of

miles traveled one-way per trip by school bus for the entire

state of Georgia in recent years was as follows (Ex. P-18):

Thus, the longest distance traveled on any route under plain

tiffs' plan - 15 miles - is equal to the average trip traveled

in Georgia by school bus in 1970-71. The present school bus

service in Atlanta, discussed below, also averages 15 miles per

1955-56

1960-61

1966- 67

1967- 68

1968- 69

1969- 70

1970- 71

19.3

18.5

17.9

17.7

17.3

16.6

15.0

39

school trip. R. 419; Ex. P-38. Busing under plaintiffs' plan

is well within the distance which is conventional and accepted

27/

in Atlanta and in other Georgia school systems today.

4. Present Busing - 39,000 Daily Rides. Many of the

33,000 pupils the court found would be bused by plaintiffs' plan

27/ See Exhibit P-18 and depositions of John Maddox, Ex. P-75,

R. 390-394. The Georgia Department of Education reported that

in 1970-71, 565,830 Georgia pupils rode school buses daily;

517,206 lived more than 1-1/2 miles from school. The State

reported the following statistics for 1970-71:

Number of Buses 5,413

Number of Trips 9,521

Miles Traveled:

One Way:

Total Daily 142,707

Per Bus 26.4

Per Trip 15.0

Annual:

Total 51,257,374

Per Bus 9,469

Per Trip 5,384

Pupils Transported:

Total 565,830

Per Bus 104.5

Per Trip 59.4

Expenditures (per annum):

Total $25,226,540.78

Bus $4,660.36

Trip $2,649.57

Child $44.58

Mile 49.2

40

already ride buses every day. The complexity of the current

arrangement makes the exact overlap unclear. The central fact

is that in 1971-72 there were 39,414 daily student rides (R.

414-415) publicly subsidized on buses operated by the Metropolitan

Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA). Ex. P-35, P. 36, P-37a,

P—37b, P—38. Eighty—five or 90% of these were students in

Atlanta City public schools (R. 414). About 40% of the 39,000

rides are in the morning and 60% are in the afternoon (R. 422).

The present school busing in Atlanta public schools was

described by William Nix, Chief Transportation Engineer,

Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority, whose expertise

was stipulated (R. 395-429). MARTA is a "governmental body"

28/

under the laws of Georgia (R. 416).

Nix testified MARTA provides bus service to Atlanta public

schools under three arrangements:

(a) Special Bus Service. Since the early 1940's MARTA

or its predecessor ATS, has offered school children in the

28/ Georgia Laws 1965, p. 2243; Georgia Laws 1966, p. 3264;

and Georgia Laws 1971, pp. 2082, 2092; Constitution of Ga.,

Art. VII (Ga. Code Ann. §§ 2-8601 to 2-8605). On February 16,

1972, MARTA, through a purchase of all stock of the former

Atlanta Transit System (ATS), became the public authority

charged with operating all public transportation services

presently used by the Atlanta school system. MARTA has con

tinued to operate under policies established by ATS for all

purposes relevant to this suit, and the testimony of William G.

Nix relating to the ATS, describes present MARTA practices.

41

4

metropolitan area of Atlanta "Special Bus Service." Special

buses make a "school run" before or after their regular routes.

MARTA allots 99 buses in the morning and 189 afternoon, for

schools in the Atlanta metropolitan area (Ex. P-38) .

Approximately 85%-90% of such Special Bus Service is for

the benefit of the Atlanta City public school system with 52

elementary and 26 high schools in the Atlanta system having

special routes (Ex. P-36). MARTA makes 467 trips per day on

Special School Runs for a total of 7,004 miles per day or 24

miles per average bus trip and 15 miles per school trip. Ex. P-38

The runs average 45.5 passengers per trip. Ibid. A partial fare

of 10 cents is charged student riders. No other monies are

paid to MARTA for school runs, and student fares do not cover

the actual costs. General fares of non-school passengers must

compensate for a yearly deficit of $535,100 (Ex. P-37a), caused

by the Special School Runs.

(b) Contract Buses. In 1971-72 MARTA provided eight

charter buses for students in "majority-to-minority" desegrega

tion transfers. Unlike Special Bus Service, charter buses are

free to students and paid for by the Atlanta Board at $50 per

bus per day, or a yearly total of about $112,000 (R. 427).

(c) Student Riders on Regular Bus Routes. MARTA also

offers a reduced 10 cents fare to students using regularly

42

scheduled bus routes. Nix testified it was impossible to esti

mate the exact subsidy provided by MARTA for this group but

that the ten cent fare in effect since the 1950's did not cover

the cost. Of the total 39,414 daily student riders, 42.6% are

school passengers on regular bus runs, while 57.7% rode on

special service (Ex. P-376).

The demands for Special Bus Service for Atlanta public

schools has increased annually. ATS has turned down approxi

mately 30 requests annually for Special Bus Service.

We estimate that more than $1,189,432.20 is spent annually

29/

for transporting students to Atlanta public schools.

5* Use of Busing to Segregate Pupils. The former superin

tendent of schools, Miss Ira Jarrell, testified in 1959 that

the Atlanta public school system paid for transportation of black

29/ Estimated as follows (based on 85% of MARTA totals for

city schools):

$ 355,470.00

454,835.00

267,127.20

1 1 2,0 0 0 . 0 0

$1,189,432.20

+ unknown

Paid by students riding special runs

Subsidy provided by MARTA for special

runs

Student fares paid on regular service

Contract Bus Service, paid by Atlanta

Board of Education

Subsidy by MARTA for students on regu

lar runs

Ex. P-37a, 37b; R. 412, 427.

43

children from an area where there was no black school to a

segregated school in another part of the City. These pupils

in the neighborhood of the former Philadelphia School were

bused to Thomas Oliver School (all within the city limits) on

buses operated by the county school system. The Atlanta school

system paid for this transportation by contract arrangement

with the county. See Ex. P-40.

Exhibit P-27, a school board bond proposal dated May 10,

1954, shows busing in 1954:

In the Southwest high school area many students

are transported two and three miles to J. C.

Nsrris School. This is being done in order to

prevent double sessions at Cascade and Venetian

Hills. (Ex. P-27, p. 1)

And, of course, the special bus runs of ATS (now MARTA)

were established years before desegregation began when state law

required bus segregation. Georgia Code Ann. § 68-616. The

school system cooperated with the bus company in arranging the

special runs. School opening and closing hours are adjusted

to accommodate the practical requirements of the bus company.

Exhibit P-26 shows the staggered schedules; and see Dr. Cook's

Deposition, pp. 16-18.

6* National School Bus Statistics. In 1969-70, there were

18,757,735 pupils transported in the United States at public

expense. Ex. P-22.

44

The National Safety Council reports that transportation by

school bus is safer than other methods of going to and from

school and accounts for a very tiny proportion of school acci

dents. See P-23 and P-24.

7. Cost of Busing Under Plan. The court found that plain

tiffs' plan would require 200 operating buses and 20 spares.

The court found the initial investment would be $13,500 to

$14,000 per bus or $2.97 to $3.08 million dollars plus $1 mil

lion for garages, or a total of $4 million. The court estimated

operating costs at $40 per day per bus or 1.8 million dollars

annually.

Although we think nothing in the case hinges on the dif

ference, plaintiffs believe the court's estimate is too high.

We acknowledge that precision in such advance estimates is

impossible, but other systems operate much more cheaply. The

record contains much data on the busing experience of other

systems. P-18, P-19, P-20, P-21, P-74.

Dr. Stolee estimated the cost of 100 buses needed for the

plan by various methods. See Ex. P-14. He estimated the cost

from $581,000 to $1,033,000. Ibid. Dr. Stolee also explained

how some districts avoid any capital outlay by contracting for

bus service. Ibid.

The 1970-71 Georgia statewide average busing costs was

$44.58 per pupil per year, and $25.89 per bus per day

45

($4,660 -*- 180 days). Ex. P-18, Table 1. Using the court's

figure of 33,000 pupils, the annual cost would be $1.47 mil

lion at the Georgia average per pupil cost. Using the court's