Thurgood Marshall Legal Society and Black Pre-Law Association v Hopwood Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

April 30, 1996

42 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Thurgood Marshall Legal Society and Black Pre-Law Association v Hopwood Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1996. 56826c1a-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4c4da0a4-9c22-44ca-a4a2-0be3cba43cc3/thurgood-marshall-legal-society-and-black-pre-law-association-v-hopwood-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

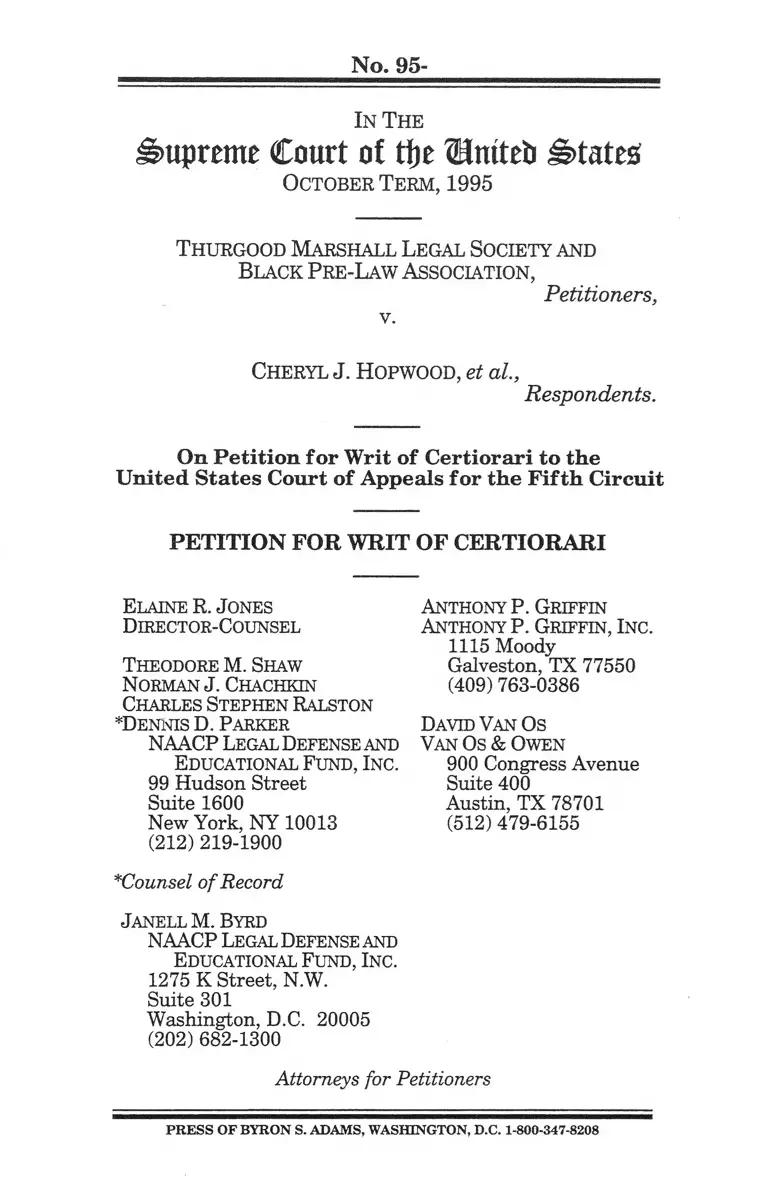

No. 95-

In The

Supreme Court of tfje Ifmteb States?

October Term, 1995

Thurgood Marshall Legal Society and

Black Pre-Law Association,

Petitioners,

v.

Cheryl J. H opwood, et a l,

Respondents.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for the F ifth Circuit

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

E laine R. J ones Anthony P . Gr iffin

Directo r-Counsel Anthony P . Gr if f in , In c .

1115 Moody

T h eodore M. Shaw Galveston, TX 77550

N orman J. Chachkin (409) 763-0386

Charles St e ph e n Ralston

*De n n is D. P arker David Van O s

NAACP Legal Defen se and Van Os & Ow en

E ducational F u n d , In c .

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

*Counsel of Record

J anell M. Byrd

NAACP Legal Defen se and

E ducational F u n d , In c .

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Attorneys for Petitioners

900 Congress Avenue

Suite 400

Austin, TX 78701

(512)479-6155

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. 1-800-347-8208

1

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Should this Court grant certiorari to resolve a conflict

among the Circuits as to the standard to determine whether

a party may intervene as a matter of right under Rule 24(a),

Fed. R. Civ. Proc., when the party on whose side the

intervenor seeks to join is a governmental agency?

2. Were petitioner organizations of African-American

students improperly prevented from protecting their

members’ constitutional and statutory rights to seek

admission to the University of Texas Law School free of

racial discrimination when the courts below refused to allow

them to intervene in this lawsuit - in which white plaintiffs

seek to bar any consideration of race in the Law School’s

admissions process - even though Petitioners sought to offer

evidence and present defenses which the other parties to the

case refused to advance, and which Petitioners contend

establish the need for the Law School to take race into

account in making admissions decisions in order to mitigate

the continued effects of its own (and other Texas

governmental entities’) prior, intentional racial

discrimination and in order to neutralize the racially

discriminatory impact of other admissions criteria utilized by

the Law School?

3. Did the courts below err in finding that a State whose

higher educational system continues to be subject to the

mandate of the federal executive agency enforcing Title VI

of the 1964 Civil Rights Act (42 U.S.C. § 2000d) requiring

that it dismantle the remaining vestiges of its prior dual

structure, could and would adequately represent the interests

of African-American students who were the intended victims

of the discriminatory practices which pervaded and underlay

that dual structure?

4. Did the court below so far depart from the accepted

and usual course of judicial proceedings in applying the "law

of the case" doctrine to issues that patently were not decided

11

in prior proceedings (and which the panel itself

characterized as having been, at best, "implicitly decided") as

to warrant correction by this Court in the exercise of its

supervisory authority?

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING

The parties to the litigation are:

Petitioners (Proposed Intervenors):

Thurgood Marshall Legal Society

Black Pre-Law Association

Plaintiffs (Respondents):

Cheryl J. Hopwood

Douglas W. Carvell

Kenneth R. Elliot

David A. Rogers

Defendants (Respondents):

The State of Texas

The University of Texas Board of Regents

Bernard Rapoport, Ellen C. Temple, Lowell H. Leberman,

Jr., Robert J. Cruikshank, Thomas O. Hicks, Zan W.

Holmes, Jr., Tom Loeffler, Martha E. Smiley, and Mario

Ramirez, members of the University of Texas Board of

Regents

The University of Texas at Austin

Robert M. Behrdahl, President of the University of Texas at

Austin

Mark Yudof, Dean of the University of Texas Law School

Stanley Johanson, Professor of Law at the University of

Texas School of Law

iii

IV

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ........................................ i

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING ........................... iii

OPINIONS BELOW ............. .......... .......................... . 1

JURISDICTION . ................................................. 1

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED ............... 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE .................................. . 2

A. Proceedings Below ........................................ 2

B. Statement of F ac ts ........................................ 9

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

INTRODUCTION...................... 15

I. Certiorari should be granted to

resolve a conflict among the Circuits

as to whether the standard for

intervention as of right on the side of

a governmental agency is more

stringent than the standard

established by Trbovich v. United

Mine Workers........................................... 17

II. This Court should review the denial

of intervention in this case, which

involves race conscious admissions in

higher education and the continuing

vitality of Bakke, from which the

panel improperly departed, and

which should not be resolved without

the evidence that Petitioners sought

to present as Intervenors........................ 19

V

III. This Court should review the denial

of Petitioners’ motions for

intervention because the bases upon

which the court below affirmed the

trial court’s denials conflict with

relevant decisions of this Court and

depart from accepted standards of

judicial conduct. . .................................. 25

CONCLUSION ............................................................ 30

VI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Pages:

Adams v. Richardson,

351 F. Supp. 636, 356 F. Supp. 92 (D.D.C.),

modified and ajf’d unanimously en banc

480 F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir. 1973), dismissed sub

nom. Women’s Equity Action League v. Cavazos,

906 F.2d 742 (D.C. Cir. 1990) .................... 12, 13

Association Against Discrimination in Employment v.

City of Bridgeport,

594 F.2d 306 (2d Cir. 1979) cert, denied 455

U.S. 988 (1982) .................... .. .................. .. . 24

Borders v. Rippy,

247 F.2d 268 (5th Cir. 1957)............................. 14

Bowen v. United States,

422 U.S. 916 (1975) ........................................ 21

Brody by and Through Sugzdinis v. Spang,

957 F.2d 1108 (3rd Cir. 1992) ......................... 18

Bush v. Vitema,

740 F.2d 350 (5th Cir. 1984)............................... 4

Conservation Law Foundation v. Mosbacher,

966 F.2d 39 (1st Cir. 1992) ........................... .. 19

County Court of Ulster County v. Allen,

442 U.S. 140 (1979) ........................................ 21

Dimond v. District of Columbia,

792 F.2d 179 (D.C. Cir. 1986) ......................... 18

Environmental Defense Fund, Inc. v. Higginson,

631 F.2d 738 (D.C.Cir. 1979)........................... 18

Flax v. Potts,

204 F. Supp. 458 (N.D. Tex. 1962), aff’d, 313

F.2d 284 (5th Cir. 1963).................................... 14

Groves v. Alabama State Board of Education,

776 F. Supp. 1518 (M.D. Ala. 1991)................ 23

Hopwood v. Texas

861 F. Supp. 551 (W.D. Tex. 1994).................... 1

Houston Independent School District v. Ross,

282 F.2d 95 (5th Cir. 1960) ........................ .. . 14

Kirkland v. New York Dept, of Correction Services,

628 F.2d 796 (2d Cir. 1980), cert, denied. 450

U.S. 980 (1981) ............................................... 24

Knight v. Alabama,

14 F.3d 1534 (11th Cir. 1994).......................... 25

LULAC v. Clements,

999 F.2d 831 (5th Cir. 1993), cert, denied, 114

S. Ct. 878 (1994).............................................. 14

Larry P. v. Riles,

793 F.2d 969 (9th Cir. 1984)............................. 23

Martin v. Wilks,

490 U.S. 755 (1989) .................. ...................... 29

vii

Pages:

Meek v. Dade County,

985 F.2d 1471 19

Mille Lacs Band of Indians v. Minnesota,

989 F.2d 994 (8th Cir. 1993)........................ .. , 18

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 (1978) ............................... .. . passim

Rodriguez de Ouijas v. Shearson/American Express,

Inc., 490 U.S. 477 (1989) ............................... .. 21

Sagebrush Rebellion, Inc. v. Watt,

713 F.2d 525 (9th Cir. 1983)........................ .. . 18

Sanguine, Ltd. v. United States Department of the

Interior, 736 F.2d 1416 (10th Cir. 1984) . 18

Smuck v. Hobson,

408 F.2d 175 (D.C. Cir. 1969) .................... 29

Stallworth v. Monsanto Co.,

558 F.2d 257 (5th Cir. 1977)............................. 29

Sweatt v. Painter,

339 U.S. 629 (1950) .................... .. 10, 11, 17

Three Affiliated Tribes v. World Engineering,

467 U.S. 138 (1984) ........................................ 21

Trbovich v. United Mine Workers,

404 U.S. 528 (1972) ............. ............... 17, 18, 26

United States v. Fordice,

505 U.S, 717 (1992) ........................ 6, 13, 24, 25

vin

Pages:

United States v. Hooker Chemicals & Plastics,

749 F.2d 968 (2nd Cir. 1984) ............. 18

IX

Pages:

United States v. New York,

820 F.2d 554 (2nd Cir. 1987) ........................... 18

United States v. Oregon,

839 F.2d 635 (9th cir. 1988)........................ 18, 19

United States v. State of Texas,

321 F. Supp. 1043, 330 F. Supp. 235 (E.D. Tex.

1970), aff’d with modifications, 447 F.2d 441

(5th Cir. 1971), cert, denied,

404 U.S. 1016 (1972)............................... .. 14

United States v. Stringfellow,

783 F.2d 821 (9th Cir. 1986), vacated

remanded on other grounds sub nom.,

Stringfellow v. Concerned Neighbors in Action,

480 U.S. 370 (1987) ........................................ 18

United States v. Texas Eastern Transmission

Corporation,

923 F.2d 410 (5th Cir. 1991) ........................ 29

United States v. Texas Education Agency (Austin),

467 F.2d 848 (5th Cir. 1972)............................. 14

Venegas v. Skaggs,

867 F.2d 527 (9th Cir.) aff’d 495 U.S. 82

(1989)................................................................ 29

Walton v. Alexander,

20 F.3d 1350 (5th Cir. 1994) ........................... 21

Washington Electric Company v. Massachusetts

Municipal Electric Company,

922 F.2d 92 (2d Cir. 1990)............................... 29

Wygant v. Jackson Board of Education,

476 U.S. 267 (1986) 22

Statutes: Pages:

Fed. R. Civ. P. 24 (a) .................................. 2, 18, 26, 29

Fed. R. Civ. P. 24(a) ............................................. 3, 4, 17

Fed. R. Civ. P. 24(b) ................................................. 3, 5

Tex. Const, art. VII, §7 (1925, repealed 1969) ........... 10

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) ........................................................ 1

42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1983 ........................................... 2

42 U.S.C. § 2000d .....................................................passim

34 C.F.R. § 100.3(b)(2) ............................................... 23

Pages:

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit was filed on March 18, 1996, is

reported at 78 F.3rd 932 (5th Cir. 1996) and is reprinted in

the Appendix at la-93a.

The May 11,1994 opinion of the United States Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit affirming the initial denial

of intervention is reported at 21 F.3d 603 (5th Cir. 1994)

(per curiam) and appears at 94a-100a. The August 19, 1994

opinion of the United States District Court for the Western

District of Texas declaring unconstitutional the admission

process used at the University of Texas Law School is

reported at 861 F. Supp. 551 (W.D. Tex. 1994) and can be

found in the appendix at 101a-187a. On January 24, 1994,

the District Court denied the Petitioners’ first motion for

intervention the unpublished decision of the district court is

contained in the appendix at 190a-195a. An unpublished

order entered on July 15, 1994 by the District Court for the

Western District of Texas denying Petitioners' second motion

for intervention appears at 188a-189a. On March 18, 1992,

Petitioners' suggestion for rehearing en banc was denied.

This denial can be found at 196a-198a. The Fifth Circuit on

April 23, 1996 issued two opinions of seven of the sixteen

judges dissenting from the Court of Appeal’s failure to grant

rehearing en banc in this case and the consolidated case on

the merits both of which appear at 196a-210a.

JURISDICTION

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1). The judgment of the United States

Court of Appeals was filed on March 18, 1996. The Order

denying the petition for rehearing was entered April 4,1996.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS

INVOLVED

This case involves the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution which provides, in relevant part:

2

All persons bom or naturalized in the United States,

and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of

the United States and the State wherein they reside.

No state shall . . . deny any person within its

jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

The case also involves Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d, which states:

No person in the United States shall, on the ground

of race, color or national origin, be excluded from

participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be

subjected to discrimination under any program or

activity receiving Federal financial assistance.

The case also involves Fed. R.Civ. P. 24 (a), which states, in

relevant part:

Intervention of Right. Upon timely application

anyone should be permitted to intervene in an action

. . . (2) when the applicant claims an interest relating

to the property or transaction which is the subject of

the action and the applicant is so situated that the

disposition of the action may as a practical matter

impair or impede the applicant’s ability to protect

that interest, unless the applicant’s interest is

adequately represented by existing parties.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Proceedings Below

This suit was initiated by the filing of two complaints

on September 29, 1992 and April 23, 1993 by two separate

groups of white plaintiffs who had unsuccessfully applied for

admission to the University of Texas Law School

(hereinafter "the Law School") for the school year beginning

in 1992. Plaintiffs claimed that the consideration of race by

the Law School as part of a remedial policy of affirmative

action in admissions violated the Fourteenth Amendment to

the United States Constitution; 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1983;

3

and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§

2000d et seq.

The district court bifurcated the procedural and

merits issues and allowed the commencement of discovery

related solely to issues of standing and ripeness. The State

of Texas filed a motion for summary judgment on

procedural grounds on August 13, 1993 which the District

Court denied on October 28, 1993. On November 17, 1993,

the Court authorized the beginning of merits discovery.

On January 5, 1994, less than two months after the

beginning of discovery and nearly three months before its

scheduled completion, Petitioners first moved to intervene

in the case. Petitioners are two organizations of African-

American students. The first, the Black Pre-Law

Association (hereinafter "the BPLA") of the University of

Texas at Austin, consists of undergraduate students

interested in attending law school, including at the

University of Texas. Each year, a number of BPLA’s

student members have applied for admission to the Law

School.

The second organization, the Thurgood Marshall

Legal Society ("TMLS") is an association of students at the

Law School dedicated to advancing legal education for

African-Americans and serving the legal and other needs of

African-Americans.

Petitioners sought intervention as a matter of right

under Fed. R. Civ. P. 24(a), as well as permissive

intervention pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 24(b). They alleged

that the State could not adequately represent their interests

because of 1) the long history of the State’s discrimination

against African-Americans; 2) the State’s need to balance

the defense of the affirmative action program against other

interests such as fiscal responsibility, administrative concerns

and public opinion (which would necessarily constrain the

defense of affirmative action); and 3) the fact that the

4

Petitioners were in a better position to present evidence of

recent discrimination. 97a.

In its order denying intervention as of right, 90a, the

District Court, citing the Fed. R. Civ. P. and Bush v. Vitema,

740 F.2d 350 (5th Cir. 1984), relied upon a presumption that

the State could be counted upon to adequately defend its

own affirmative action program, and dismissed as speculative

the Petitioners’ concerns that the State would not fully

represent their interest in the upcoming hearing.

The district court also denied permissive intervention

on the ground that adding Petitioners to the case "would

needlessly increase cost and delay disposition of the

litigation." 194a.

On appeal, the Fifth Circuit upheld the denial of

intervention as of right, articulating both the general

presumption of adequate representation by existing parties

cited by the District Court and a more stringent presumption

applicable to cases involving state parties and governmental

agencies:

where the party whose representation is said to be

inadequate is a governmental agency, a much

stronger showing of inadequacy is required . . . . In

a suit involving a matter of sovereign interests, the

State is presumed to represent the interests of its

citizens.

97a-98a (citations omitted).

The Fifth Circuit ruled that these presumptions had

not been overcome because Petitioners had demonstrated

neither that the State would not strongly defend its

affirmative action program nor that the Petitioners had a

separate defense of the affirmative action plan that the State

would not present at hearing. In reaching these

conclusions, the Court relied explicitly upon its expectation

that the State would present at the forthcoming trial

5

evidence that Petitioners felt was necessary to protect their

interests:

Although the BPLA and TMLS may have ready

access to more evidence than the State, we see no

reason they cannot provide this evidence to the State.

The BPLA and the TMLS have been authorized to

act as amicus and we see no indication that the State

would not welcome their assistance.

98a.1

At the ensuing trial, the district court limited

Petitioners’ role to that of amici curiae and afforded them

no opportunity to introduce evidence or argue before the

court. Following the direction of the Fifth Circuit,

Petitioners provided the State of Texas with evidence

showing that the Texas Index, a statistical measure

combining undergraduate grade-point average and LSAT

scores used in sorting applicants to the Law School, could

not reliably predict law school performance of first-year

African-American students and offered the State the

testimony of an expert qualified to present evidence that

race-conscious admissions to the Law School were necessary

to avoid the discrimination and potential Title VI liability

that would result from reliance on the Texas Index

exclusively.2 The state declined to introduce the evidence

or the testimony of the expert witness, presented no

evidence concerning the validity of the Texas Index and

1Noting that the Fifth Circuit had never reversed a lower court’s

decision on Rule 24(b) permissive intervention, the Court found that the

district court had not abused its discretion in denying petitioners' motion

to intervene. 99a-100a.

2One need not presume animus on the part of the state to

understand why such evidence would be awkward for the state to

introduce.

6

raised no argument that race-conscious measures were

required to mitigate the discriminatory effect of its use.

At the conclusion of trial, Petitioners submitted a

post-trial amicus brief supporting the constitutionality of the

Law School’s admission policy. In the brief, Petitioners

again argued (relying upon the declaration of the expert

witness proffered to the State) that rather than being an

unjustified preference for African-American students, the

challenged race-conscious admission process was legally

required to ameliorate the discriminatory impact of the

Texas Index.

Plaintiffs moved to strike portions of Petitioners’

post-trial amicus brief including the declaration. Although

the district court denied the motion to strike, it indicated

that it would consider only the evidence introduced at trial

by the parties.

On July 12, 1994, before the district court had

announced its judgment on the merits, Petitioners moved

again to intervene for the limited purpose of introducing

evidence supporting the independent defenses that the State

failed to raise. The district court denied that motion without

opinion on July 15, 1994. 188a-189a.

On August 19, 1994, the district court entered

judgment on the merits for plaintiffs, holding that while

certain types of race-conscious admissions are

constitutionally justified at the Law School, the 1992

admissions policy under which the plaintiffs were considered

and rejected was not "narrowly tailored" and was therefore

unlawful. The court awarded plaintiffs nominal damages but

declined to order that they be admitted or to enjoin

defendants from any consideration of race in the admissions

process. Although the district court recognized that

formerly dual systems of higher education are "under an

affirmative duty to eliminate every vestige of racial

segregation and discrimination" pursuant to United States v.

7

Fordice, 505 U.S. 717 (1992), 151a, the court did not

consider or address the separate defenses advanced by the

Petitioners or hold that affirmative action by the Law School

is necessary to avoid unlawful discrimination, as urged by the

Petitioners.

Petitioners appealed from this second denial of

intervention and plaintiffs appealed the district court's

judgment on the merits. Petitioners argued that the district

court had failed to recognize the significance of the State of

Texas's unwillingness to raise the defense of its admission

programs which the petitioners had proffered in the course

of trial. Petitioners contended that the court's failure to

allow limited intervention at the conclusion of trial based

upon the fact that the State's conduct of its defense showed

unequivocally that Petitioners' and the State's interests and

defenses were divergent was error. As a result, Petitioners

alleged that they were denied the opportunity to contribute

evidence and defenses that would have compelled the court

to acknowledge the remedial basis for the Law School's

admission program and therefor effectively protect their

interest in assuring the continued presence of African-

American students to the Law School.

A panel of the Fifth Circuit affirmed the post-trial

denial of intervention without addressing Petitioners' claim

that the State's failure at trial to present the evidence which

would have compelled the use of race-conscious admissions

at the Law School constituted undeniable proof that

Petitioners’ interests were not in fact adequately

represented.

Instead, the panel upheld the district court based on

the doctrine of “law of the case”, finding that the panel

hearing the appeal of the first denial of intervention had

“implicitly” addressed the legal questions raised in the

second intervention motion - even though that motion was

not made until after the completion of trial and after it had

become clear that the first panel’s expectation that the State

would advance arguments urged by the plaintiffs was not to

be realized.

At the same time, the Fifth Circuit reversed the

district court regarding the merits case, holding in sweeping

terms that the law school may not use race as a factor in

admissions and dismissing out of hand the use of race to

achieve diversity in an academic setting as well as all

arguments that the use of race-conscious admissions was

necessary to address the present effects of past

discrimination.

Petitioners then suggested rehearing en banc on the

issue of denial of intervention.3 On April 9,1996, the Court

denied rehearing en banc and announced the forthcoming

release of a dissent from the denial. On April 23, 1996, the

two dissenting opinions from the denial of rehearing in both

of the consolidated cases were released. The first, written by

Chief Judge Politz and joined by six additional judges,

faulted the Court for denying rehearing of a panel decision

which the dissenters felt "departed from the normal

considerations of judicial restraint" by addressing issues that

had not been properly raised in the case below and by

effectively overruling this Court's decision in Bakke. Judge

Stewart wrote separately to emphasize the historical irony of

the Circuit’s failure to grant rehearing and to condemn

Petitioners’ exclusion from the lawsuit through the denial of

3The State did not seek rehearing. In their suggestion for rehearing,

as they do now, while acknowledging their inability to seek rehearing in

the merits case because they were not parties, having been denied

intervention, Petitioners stated their belief that the issues decided in the

consolidated merits appeal were of extraordinary public importance and

had an impact on the interests of all African Americans, including those

represented by Petitioners .Petitioners nonetheless stated their belief that

rehearing would be warranted due to the importance of the issues raised

as well as the apparent conflict between the panel's decision and the

holding of this Court in Regents of the University o f California v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265, 307 (1978).

9

intervention: "[a]s to the request to intervene, what class of

persons is more qualified to adduce the evidence of the

present effect of past discrimination than current and

prospective black law students?" 209a.

B. Statement of Facts

The significance of the Fifth Circuit’s exclusion of

African-American pre-law and law students from

participation in a case that could result in the

implementation of an admission process that effectively (and

unjustifiably) excludes African-American and Mexican

American students from attendance at the University of

Texas Law School can only be understood within the context

of historical and current discrimination affecting students

and applicants to the Law School and the continuing

obligation of the Law School to remedy prior discrimination.

For that reason, the facts of the merits appeal are in some

measure inextricable from issues raised by the Petitioners.

Accordingly, Petitioners submit that this Court should grant

certiorari on the question of denial of intervention as well as

on the merits, see Petition No. 95-1773, and the facts

relevant to both are discussed briefly below.4

Petitioners recognize that, as non-parties, they cannot themselves

seek review of the merits ruling, but they urge this Court to grant the

Petition filed by the State of Texas with this Court on April 30, 1996.

The decision of the Fifth Circuit prohibiting the consideration of race in

the admissions process at the University of Texas conflicts with relevant

precedents of this Court including Regents o f the University of California

v. Bakke and for the reasons given by the State and the dissenters from

the denial of rehearing en banc, warrant review by this Court:

[t]he radical implications of this opinion, with its

sweeping dicta, will literally change the face of public

educational institutions throughout Texas, the other

states of this circuit, and this nation. A case of such

monumental import demands the attention of more

than a divided panel.

200a.

As discussed below, Petitioners believe that fairness dictates not

10

There is no dispute that the State of Texas was

responsible for creating and maintaining a system of higher

education rife with discrimination:

Texas’ system of higher education has a history of

state-sanctioned discrimination. Discrimination

against blacks in the state system of higher education

is well documented in history books, case law, and

the State’s legislative history.

106a.

From the mid-1800’s until this Court’s decision in

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950), the Law School

operated with official admissions policies and practices that

expressly excluded persons of African descent. The Texas

Constitution and state statutory provisions restricted the

school to white students, Tex. Const, art. VII, §7 (1925,

repealed 1969), and at the time Heman Sweatt applied for

admission to the Law School in 1946, no law school in the

state of Texas admitted African-Americans. 106a. The

State’s response to Sweatt’s exposure of the complete

absence of legal education for African-Americans was

inadequate: "The State hastily created a makeshift law

school that had no permanent staff, no library staff, no

facilities, and was not accredited. 106a-107a, citing Sweatt v.

Painter, 339 U.S. at 632.

This Court’s unanimous decision requiring that the

University of Texas admit Mr. Sweatt did not halt the

flagrant discrimination to which he and other minority

students were subjected. As the district court found, the end

of explicit racial prohibitions did not root out deeply

only a review of the merits appeal but also the inclusion of Petitioners

both to assure that no decision of such import is made without a

complete record and to assure participation in the process by those who

had suffered most from prior discrimination and who stand to lose the

most by an adverse ruling in the matter.

11

entrenched discrimination at the Law School: "Sweatt left

the law school in 1951 without graduating after being

subjected to racial slurs from students and professors, cross

burnings, and tire slashings." 107a.

The district court found that the University of Texas

continued discriminatory policies for decades after the

Sweatt decision. In the 1950s and 60s, the Texas Board of

Regents prohibited blacks from living in or even visiting

white dormitories and assigned Mexican-American students

to segregated housing. 107a. In the 1960s, Mexican-

Americans and African-Americans were also excluded from

membership in most University-sponsored organizations. Id.

Continuing discrimination was not limited to

treatment accorded minorities upon their admission to the

Law School. The record indicated that barriers to admission

in the law school remained in place long after the Sweatt

decision. Notwithstanding the minimal standards for

admission that were in place until 1965, the number of

African-American students admitted was extremely small.

112a.

Although the Law School tried to increase minority

representation in the student body in the late 1960s through

participation in the Council on Legal Education Opportunity

(CLEO,) a program that provided summer training at

participating law schools for minority graduates of various

universities, the Law School’s involvement was short-lived,

as were any gains in minority participation. During the 1971-

72 admission cycle, after the Law School ended its

participation in the CLEO program, the Law School

admitted no African-Americans . 114a.

The first serious effort to remedy segregation at the

Law School came as a result of an action brought against the

United States Department of Health, Education and Welfare

("HEW"), the predecessor to the United States Department

of Education. In 1970, a class of African-American students

12

in 17 Southern and border states, including Texas, sued

HEW asserting that the federal government’s funding of

state systems of higher education that discriminated against

African-Americans by operating segregated institutions

violated Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the

U.S. Constitution. Adams v. Richardson, 351 F.Supp. 636

(D.D.C. 1972), 356 F.Supp. 92 (D.D.C.), modified and affid

unanimously en banc, 480 F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir. 1973),

dismissed sub nom. Women’s Equity Action League v.

Cavazos, 906 F.2d 742 (D.C. Cir. 1990). The district court

ordered the federal government to enforce Title VI in higher

education.

In 1980, the Adams plaintiffs sought further relief

with respect to the higher education systems in Texas and

other states. In 1981 the Office for Civil Rights of the

United States Department of Education ("OCR") found that

Texas had "failed to eliminate the vestiges of its former de

jure racially dual system of public higher education, a system

which segregated blacks and whites." 109a.

In 1982, the Assistant Secretary of Education

informed the State defendants that existing plans, which

included a commitment to the goal of equal educational

opportunity and student body desegregation for both blacks

and Hispanics, were insufficient to eliminate the vestiges of

past discrimination. The plan’s goals for the enrollment of

African-American and Hispanic students fell short of the

State’s earlier commitment to seek enrollment of those

groups in proportion to their representation among

graduates of the State’s undergraduate institutions. 104a-

110a referring to Letter of Assistant Secretary of Education

Clarence Thomas, D-284. The defendants responded with

a revised plan, which OCR rejected, in part because it did

not set targets for increasing minority enrollment for each

institution. Id.

On March 23, 1983, the district court ordered OCR

to commence formal enforcement proceedings against Texas

13

within 45 days, unless OCR concluded that Texas had

submitted a desegregation plan in full conformity with

governing law. 110a. After the 1983 Adams Order, Texas

submitted an amended plan to OCR in which it committed

itself to improved measures to meet enrollment goals for

black and Hispanic students in its professional schools.

Under this plan, defendants agreed "to consider each

candidate’s entire record and [to] admit black and Hispanic

students who demonstrate potential for success but who do

not necessarily meet all traditional admission requirements."

110a. The plan was subject to monitoring for compliance

until 1988. 111a.

In 1987, OCR contacted state higher education

authorities informing them that a final evaluation would

have to be conducted prior to the expiration of the plan the

following year in order to determine if the State met its

obligations. 111a. Having itself determined that the goals

and objectives of the plan had not been met, the State

voluntarily developed a successor plan. Id. As of the time

of the district court’s ruling in this case, OCR had not

completed its evaluation of Texas’ compliance with Title VI.

112a. In January 1994, the Department of Education

notified Governor Richards that OCR was continuing to

oversee Texas’ efforts to eliminate all vestiges of de jure

segregation and that it would be reviewing the Texas system

in light of United States v. Fordice, 505 U.S. 717 (1992).

In addition to its findings about the continuing

vestiges of discrimination in the Law School, the district

court made findings that placed the Law School within the

context of education statewide.5 As is true in the area of

higher education, Texas has a long and lingering history of

discrimination at the elementary and secondary school levels:

5Since state law requires that enrollment at the Law School must

consist of 85% Texas residents, the majority of law students attended

Texas schools at earlier stages of their academic careers. 128a-129a.

14

"[t]he history of official discrimination in primary and

secondary education in Texas is well documented in history

books, case law and the record of this trial." 104a. See also

LULAC v. Clements, 999 F.2d 831 (5th Cir. 1993, cert,

denied, 114 S. Ct. 878 (1994)(recognizing that the long

history of discrimination against African-Americans and

Hispanics in all areas of public life is beyond dispute).

Indeed, the State of Texas and virtually every major school

system within it have been found by a court to have

operated a racially dual system of education. See e.g.

Houston Independent School District v. Ross, 282 F.2d 95, 96

(5th Cir. 1960); Borders v. Rippy, 247 F.2d 268 (5th Cir.

1957)(Dallas); United States v. Texas Education Agency

(Austin), 467 F.2d 848 (5th Cir. 1972); Flax v. Potts, 204

F.Supp. 458 (N.D. Tex. 1962), aff’d, 313 F.2d 284 (5th Cir.

1963) (Ft. Worth); United States v. State of Texas, 321 F.

Supp. 1043, 330 F. Supp. 235 (E.D. Tex. 1970), affd with

modifications, 447 F.2d 441 (5th Cir. 1971), cert, denied, 404

U.S. 1016 (1972) (statewide relief).

Many of these districts have not been determined to

have eliminated (to the extent practicable) all vestiges of the

dual systems under which they once operated. The trial

court expressly found that, as of May 1994, "the problem of

segregated schools is not a relic of the past" as reflected in

the fact that desegregation lawsuits remained pending

against more than forty Texas school districts. 105a.

The court also found that persistent racial hostility at

the Law School had perpetuated the perception that the Law

School was intended for white students. 153a.

After weighing the examples of persistent vestiges of

discrimination including those cited above, the district court

found that "[t]he defendants have shown it is not possible to

achieve a diverse student body without an affirmative action

program that seeks to admit and enroll minority candidates."

156a. Dramatic proof of the need for affirmative action

could be seen in the effect that elimination of race-conscious

15

relief would have on the racial composition of the student

body at the Law School. The court made an evidentiary

finding that "[h]ad the law school based its 1992 admissions

solely on the applicants’ [Texas Index scores] without regard

to race or ethnicity, the entering class would have included,

at most, nine blacks and eighteen Mexican Americans." 150a.

In addition to the evidence of the present effects of

past discrimination considered by the court, the Petitioners

sought to intervene twice to present evidence which showed

that admissions practices currently in use had a

discriminatory impact on African-American students.

Petitioners identified and made known to State defendants

an expert witness who was qualified to present evidence that

race-conscious admissions to the Law School were necessary

to avoid the unlawful racial discrimination (in violation of

Title VI) that would result from application of the same

Texas Index requirements to white and African-American

students. This evidence was never properly before any of

the courts below because of the State’s refusal to present

this defense and the lower courts’ refusal to allow Petitioners

to intervene to present this and other defenses.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

INTRODUCTION

In holding that the University of Texas Law School

may not consider race as a factor in making admissions

decisions, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals disregarded this

Court’s decisions while excluding evidence that provided

ample justification for the use of race-conscious criteria in

admissions. The Court’s errors of deciding issues not fully

presented by the case before it, of failing to recognize the

significance of continuing effects of the State’s prior

unconstitutional conduct, and of rejecting the holding in

Regents of the University o f California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265

(1978), that the goal of diversity in higher education is a

sufficient justification for considering race as a factor when

16

making admissions decisions, were compounded by its

affirmance of the district court's denial of intervention to the

Thurgood Marshall Legal Society and the Black Pre-Law

Association, organizations which represent African-American

students who attend the University of Texas Law School

and the University of Texas.

The Fifth Circuit's decision to exclude the Petitioners

from this litigation should be reviewed by this Court not only

because it impedes their ability effectively to protect their

interest in preserving an admission program that counters,

rather than perpetuates, the effects of discrimination of

which they were historical victims but also because the effect

of the denial of intervention was to preclude the

introduction of evidence that would have amply justified the

use of race-conscious measures — evidence the State refused

to present and which only the Petitioners were prepared and

willing to proffer at trial.

Constitutional questions as far-reaching as those

raised in this case should be decided carefully after rigorous

examination of all of the potential defenses and with

consideration of all of the varying interests involved. Such

rigor was absent in the decision below. Decisions made on

a perfunctory basis are undesirable in any case. In this case,

the effects were particularly serious. The failure to permit

the parties who have the most to lose from a prohibition

against race-conscious admissions to enter the case and the

court's unwillingness to consider competent evidence that

affirmative action was not only justified but compelled by the

existence of present discrimination against African-

Americans is particularly grave given Texas' long history of

denying equal educational opportunity to the class of which

Petitioners are members.

African-Americans increasingly find themselves

reduced to the status of observers of Federal Court

proceedings that result in loss of hard-fought achievements

of earlier cases brought by their predecessors. The loss of

17

those achievements is felt even more harshly when, as here,

African-Americans denied the opportunity to intervene are

compelled to watch while the defense of their interests is

placed entirely in the hands of entities which have for

generations fought to deny them equal rights and which even

today decline to use the most effective weapons in the

arsenal of available defenses. The very same law school

which was the subject of this Court’s landmark decision in

Sweatt v. Painter, which first opened the doors to legal

education for African-Americans seeking to attend in Texas,

has failed to adequately represent the interests of African-

American students. This Court should review the panel’s

decision and take corrective action.

I. Certiorari should be granted to resolve a conflict

among the Circuits as to whether the standard for

intervention as of right on the side of a

governmental agency is more stringent than the

standard established by Trbovich v. United Mine

Workers.

The court of appeals noted that the standard for

intervention as a matter of right under Rule 24(a), Fed.

Rules of Civ. Proc., ordinarily imposes a minimal burden on

the movant, citing this Court’s decision in Trbovich v. United

Mine Workers, 404 U.S. 528, 538 n. 10 (1972), holding that

the requirement "is satisfied if the applicant shows that

representation of his interest ‘may be’ inadequate." 97a.

The court below denied intervention to petitioners, however,

by applying a "much stronger showing of inadequacy"

because the party in question is a government agency, on the

ground that in "a suit involving a matter of sovereign

interest, the State is presumed to represent the interests of

all of its citizens." 97a-98a.

There is substantial conflict and confusion among the

courts of appeals as to whether the minimal Trbovich

standard, or the Fifth Circuit’s "much stronger" standard

governs where the party whose representation is claimed to

18

be inadequate is a governmental agency. This is an

important and recurring issue in the lower federal courts,

and the conflict among them should be resolved by this

Court.

The Second and Third Circuits have applied

substantially the same parens patriae presumption as the one

applied by the Fifth Circuit here. See Brody by and Through

Sugzdinis v. Spang, 957 F.2d 1108, 1122 (3rd Cir. 1992);

United States v. Hooker Chemicals & Plastics, 749 F.2d 968,

987 (2nd Cir. 1984); but cf, United States v. New York, 820

F.2d 554, 558 (2nd Cir. 1987)(parens patriae presumption

applies only when state acts as the sovereign representative

of all of its people, not applicable when state sued in its

capacity as an employer under Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964).

On the other hand, the Ninth and Tenth Circuits

have applied the Trbovich standard consistently in cases

where the party whose representation is claimed to be

inadequate is a governmental agency. See Sagebrush

Rebellion, Inc. v. Watt, 713 F.2d 525, 528 (9th Cir. 1983);

United States v. Stringfellow, 783 F.2d 821, 827 (9th Cir.

1986), opinion vacated and remanded on other grounds sub

nom., Stringfellow v. Concerned Neighbors in Action, 480 U.S.

370 (1987); United States v. Oregon, 839 F.2d 635, 637-38

(9th cir. 1988); Sanguine, Ltd. v. United States Department of

the Interior, 736 F.2d 1416, 1419 (10th Cir. 1984).

Still other Circuits have taken different positions in

different cases. Thus, the Court of Appeals for the District

of Columbia Circuit followed the parens patriae rule in

Environmental Defense Fund, Inc. v. Higginson, 631 F.2d 738

(D.C.Cir. 1979), but has permitted liberal intervention,

holding that Rule 24 (a) is satisfied when it can be said that

the applicant intervenor has an interest different from the

governmental agency Dimond v. District of Columbia, 792

F.2d 179 (D.C. Cir. 1986); accord, Mille Lacs Band of

Indians v. Minnesota, 989 F.2d 994, 1000-1002 (8th Cir.

19

1993)(announcing parens patriae rule, but following Dimond

in liberally finding inadequacy of representation); Meek v.

Dade County, 985 F.2d 1471, n.77-78 (11th Cir.

1993)(presumption of adequacy of representation dissipates

upon any showing of divergence of interests). See generally

Conservation Law Foundation v. Mosbacher, 966 F.2d 39, 41-

43 (1st Cir. 1992)(noting the split among the other circuits

while finding government representation inadequate in case

at bar).

In short, it is clear that under the standard of the

Ninth Circuit, for example, Petitioners would have been

permitted to intervene, since the State of Texas would not

and did not "make all the arguments the applicants would

make." United States v. Oregon, 839 F.2d at 638. The same

result would have obtained in the Tenth Circuit and, most

probably, in the District of Columbia, Eighth, and Eleventh

Circuits as well. As we will now discuss, the issues raised by

this case, and the arguments and evidence that would have

been made by the Petitioners had they been granted party

status through intervention exemplify the ways in which

erroneous decisions respecting intervention can affect a

court’s judgment on the merits and underscore the need for

this Court to state the correct standard.

II. This Court should review the denial of

intervention in this case which involves race

conscious admissions in higher education and

the continuing vitality of Bakke from which

the panel improperly departed, and which

should not be resolved without the evidence

that Petitioners sought to present as

Intervenors.

The Fifth Circuit's decision on the companion merits

appeal was far ranging and broad in its scope:

In summary, we hold that the University of Texas

School of Law may not use race as a factor in

20

deciding which applicants to admit in order to

achieve a diverse student body, to combat the

perceived effects of a hostile environment at the law

school, to alleviate the law school's poor reputation

in the minority community, or to eliminate any

present effects of past discrimination by actors other

than the law school.

76a-77a.

This single sentence not only sums up a holding

purporting to relate to infirmities of the selection process

used by the Law School in 1992 but also effectively

articulates a fundamental departure from and narrowing of

the permissible use of race in admissions in higher

education. As recognized by the judges dissenting from the

denial of en banc consideration,”[t]he radical implications of

this opinion, with its sweeping dicta, will literally change the

face of public educational institutions throughout Texas, the

other states of this circuit, and this nation.” 200a. That the

panel saw fit to disregard and effectively to overrule this

Court's decision in Regents of the University of California v.

Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978) permitting the consideration of

race for purposes of obtaining a diverse student body, is

itself sufficiently problematic. That it did so in a case which

did not require a large-scale re-examination of what

constitutes a compelling interest justifying the consideration

of race as a factor in admissions in higher education adds

injury to the initial insult.

This judicial overreaching is particularly egregious

because, in addition to the reasons cited in the dissents, had

any of the lower courts granted Petitioners' intervention

motions, an additional, narrower basis for deciding the issue

of the constitutionality of race-conscious admissions would

have been before the court.

Both the concurring opinion of the three-judge panel

and the dissents from denial of rehearing en banc, faulted

21

the panel and the entire court for violating basic restrictions

on judicial authority. As a preliminary matter, "[t]he

Supreme Court has left no doubt that as a constitutionally

inferior court [the Fifth Circuit is] to follow faithfully a

directly controlling Supreme Court precedent unless and

until the Supreme Court itself determines to overrule it.”

201a, citing Rodriguez de Ouijas v, ShearsonjAmerican

Express, Inc., 490 U.S. 477 (1989).

In addition to the constraints imposed upon Courts

of Appeals by decisions of the United States Supreme Court,

judicial restraint counsels against deciding constitutional

issues not necessary to the disposition of individual cases, a

principal that the court below has recognized in other

contexts but refused to apply in this case:

[I]t is settled that courts have a “strong duty to avoid

constitutional issues that need not be resolved in

order to determine the rights of the parties to the

case under consideration.” County Court o f Ulster

County v. Allen, 442 U.S. 140, 154 (1979). This

responsibility to avoid unnecessary constitutional

adjudication is a fundamental rule of judicial

restraint. Three Affiliated Tribes v. World Engineering,

467 U.S. 138, 157 (1984). All this, of course, applies

not only to the Supreme Court but to lower courts as

well. See Bowen v. United States, 422 U.S. 916

(1975).

Walton v. Alexander, 20 F.3d 1350, 1356 (5th Cir. 1994).

The Fifth Circuit violated both the charge to follow

Supreme Court precedent and the prohibition against

deciding unnecessary constitutional issues by treating this

Court's decision in Bakke as no longer binding and issuing

a blanket prohibition against the consideration of race in

admission to the Law School:

Rather than following this universally recognized

canon, adhering to our established rules, and

22

applying Supreme Court precedent, the panel charted

a path into terra incognita. Judicial self-restraint was

the first casualty . . . . The teachings proscribing the

consideration of constitutional issues unnecessary to

the decision soon followed. With these two

limitations adroitly set aside, the panel majority

apparently considered itself positioned to overrule

Bakke.

205a.

The exclusion of Petitioners, and of the arguments

and evidence that they sought to introduce is particularly

ironic given the fact that those arguments and evidence

would have expressly addressed the panel’s concern that

there was insufficient showing of a factual basis for the Law

School’s belief that it had a remedial justification for its

racial classifications. 43a, citing Wygant v. Jackson Board of

Education, 476 U.S. 267, 277-78 (1986).

Petitioners sought to intervene precisely for the

purpose of providing such remedial justification. They

initially suggested to defendants that the Texas Index

measure is invalid as to African-Americans and that its use

in the admissions process had a discriminatory effect on

African-Americans. As soon as it became clear that the

State would not use this defense, Petitioners sought to

introduce it themselves through a declaration prepared by

Dr. Martin Shapiro. In his declaration, Dr. Shapiro summed

up the results of his examination of the evaluation of

statistics about the Law School’s entering classes of 1986,

1987 and 1988 that were in the trial record:

Specifically, I have concluded (1) that regression

analysis results obtained by the Law School

Admission Services [Plaintiffs Exhibits 136 and 137]

conclusively demonstrate that the selection criteria

which the Law School has used to evaluate African-

American applicants were invalid, (2) that the Texas

23

Index should not have been used as an initial sorting

criterion for African-American applicants, but (3)

that the practice of reducing the numerical values of

the Texas Index required of African-American

applications had, at least some, ameliorative effect

upon the invalid application of the Texas Index.

Shapiro Declaration at 117.

Shapiro further concluded that "[t]he best, most valid,

[admissions] procedure would have been to eliminate the use

of the Texas Index as an initial sorting criterion for the

African-American applicants and to proceed directly to the

more extensive evaluation and review of the applications."

Shapiro Declaration at 1135. Failing that, however, lowering

the Texas Index values used to sort African-American

applications -- the course actually taken by the Law School

— "at least partially ameliorated the invalid preclusive effect

of the Texas Index" by disfavoring fewer blacks under a

measure that was invalid for them as a group. Id. at 1137.

In contrast, Dr. Shapiro found that "the least valid

procedure would have been to sort initially all applicants by

applying the same required Texas Index values to both

White and African-American applicants" id. at 11 38

(emphasis added) -- the alternative sought by plaintiffs. The

result of this process would be to eliminate unlawfully

"almost all African-American applicants, generally, and to

eliminate many or all of the most qualified African-

American applicants." Shapiro Declaration at 11 18.

The use of invalid measures that have a

discriminatory effect on African-Americans is unlawful. See

34 C.F.R § 100.3(b)(2)(1993) (U.S. Department of

Education regulations implementing Title VI); Larry P. v.

Riles, 793 F.2d 969 (9th Cir. 1984)(use of non-validated IQ

tests with discriminatory effect on black children to place

students in classes for the educable mentally retarded

violates Title VI); Groves v. Alabama State Board of

24

Education, 776 F. Supp. 1518 (M.D. Ala. 1991) (enjoining,

under Title VI, state board of education from using

minimum ACT score as requirement for admission to

undergraduate teacher training program); see also United

States v. Fordice, 505 U.S. at 718-719,(expressing serious

doubts about the constitutionality of Mississippi’s continued

use of ACT cut-scores for admission to its white colleges).

Compliance with anti-discrimination law requires

eliminating or diminishing reliance on invalid, discriminatory

measures as to those groups that are disproportionately

excluded. See Kirkland v. New York Dept, of Correction

Services, 628 F.2d 796 (2d Cir. 1980), cert, denied, 450 U.S.

980 (1981) (Title VII decision affirming trial court’s addition

of 250 points to the raw scores of group adversely impacted

by invalid examination); Association Against Discrimination

in Employment v. City of Bridgeport, 594 F.2d 306 (2d Cir.

1979) cert, denied 455 U.S. 988 (1982)(Title VII decision

suggesting lowering the cut-off score for minority test takers

as suitable remedy for an invalid test with a discriminatory

effect).

Evidence of the continuing discriminatory effect of

the Texas Index complements the extensive record of OCR

findings of persistent vestiges of discrimination and

demonstrates the unequivocal existence of present effects of

discrimination. In light of the totality of the evidence, the

challenged admission process was not a racial preference but

rather a necessary and lawful response to the invalidity of

applying this measure to African-American and Mexican-

American applicants.

The failure of any of the courts below to address this

evidence at any level creates an inadequate foundation for

the broad-reaching decision rendered by the Fifth Circuit.

This Court should grant certiorari on both the merits

petition and this petition to assure that in reaching its

decisions on issues that will have a dramatic impact on both

institutions of higher learning and African-Americans, the

25

Court has the benefit of the full presentation of relevant

evidence which is obtained only through adequate

representation of important interests and argument on

behalf of all parties.

III. This Court should review the denial of

Petitioners’ motions for intervention because

the bases upon which the court below

affirmed the trial court’s denials conflict with

relevant decisions of this Court and depart

from accepted standards of judicial conduct.

Despite the strong interest Petitioners have in the

outcome of this matter, and the fact that they would have

brought to the litigation relevant evidence rejected and

disregarded by the party which the Court entrusted to

defend and represent their interests, the courts below have

repeatedly denied them intervention. This denial is

inconsistent with the ruling of this Court and prevailing

decisions in other circuits.

On no occasion has a court held in this case that

Petitioners’ bid for intervention as of right should fail

because it was untimely, or because Petitioners lacked an

interest relating to the subject of the ongoing litigation or

did not face the prospect of suffering an impairment or

impediment to their ability to represent their interests.

Petitioners, African-Americans who are present and

prospective students of the Law School, have an undeniable

interest in assuring continued opportunities for non-

discriminatory admission and retention. See United States v.

Fordice, 505 U.S. 717, 723 (1992) (recognizing role of private

plaintiffs in vindicating their interest in elimination of

vestiges of discrimination in prior dual university system);

Knight v. Alabama, 14 F.3d 1534, 1540 (11th Cir.

1994)(recognizing interest identified in Fordice). The Fifth

Circuit’s prohibition on the consideration of race in

admissions notwithstanding (a) the past history of

discrimination against African-Americans at the Law School

26

and throughout the state educational system, (b) the

discriminatory impact of the use of the Texas Index and (c)

the desirability of maintaining diversity coupled with the

virtual certainty that strict use of the Texas Index without

considering race would greatly reduce the number of

African-Americans admitted to the Law School each provide

ample proof of the extent to which Petitioners’ interests

were subject to impairment.

The Fifth Circuit sought to justify the denial of

intervention by determining that the existing parties were

able adequately to represent the Petitioners’ interests. This

finding is contrary to prevailing law and counter to the facts

of this case.

This Court has held that an applicant for intervention

can satisfy the requirements of Fed. R. Civ. P. 24 (a)(2) by

demonstrating that representation by the existing parties may

be inadequate and that the burden of making that showing

is minimal. Trbovich v. United Mine Workers, 404 U.S. 528,

538 n.10 (1972) (reversing denial of union member’s motion

for leave to intervene in suit brought by Secretary of Labor

pursuant to complaint by that member).

The district court denied the first motion for

intervention by employing a standard more stringent than

that articulated by this Court in Trbovich. Petitioners raised

the possibility of conflict in the State’s defense of its

affirmative action program, noting that the State represented

a multiplicity of interests of its numerous citizens, some of

whom likely would not share Petitioners’ concern for the

maintenance of race-conscious admissions, and that the State

was potentially liable for acts of discrimination against

African-Americans and might thus be less than vigorous in

raising defenses that might expose it to liability. Petitioners

also made clear their intention to raise questions about the

discriminatory effect of the use of the Texas Index as an

admissions sorting device. Despite these clearly articulated

reasons for believing that the State would not adequately

27

represent the interests of African-American students, the

district court rejected the potential conflict as being

speculative. 193a.

Relying on a number of cases in which the state

appeared in either a regulatory, enforcement or parens

patriae capacity, the Fifth Circuit applied a much stronger

"state government" presumption of adequacy. 96a.

This presumption was applied in a way which made

intervention virtually impossible. Even though there were

clearly articulated conflicts in the State’s interests in

sustaining both its affirmative action plan and its other Law

School admissions criteria and even though the State was

not only appearing in its parens patriae capacity but also as

an entity that had constructed and maintained a dual system

of education which discriminated on the basis of race and

continued to employ practices in admission to the Law

School which had a disproportionate impact on African-

Americans, the Court below found the presumption of

adequate representation was not rebutted.

The second ground for upholding the denial of

intervention created a similarly difficult barrier to

Petitioners’ participation. The Fifth Circuit effectively relied

upon a presumption of altruism on the State’s part:

Although the BPLA and the TMLS may have ready

access to more evidence than the State, we see no

reason they cannot provide this evidence to the State.

The BPLA and the TMLS have been authorized to

act as amicus and we see no indication that the State

would not welcome their assistance.

98a.

By so holding, the Fifth Circuit effectively

transformed the legal standard from one under which a

potential intervenor must make a minimal showing that

existing parties may not adequately represent the

28

intervenor’s interest to one under which a movant is

required to show that existing parties will categorically refuse

to assert a specific defense or introduce specific evidence.

Short of obtaining an affidavit or pleading indicating hostile

intentions, it is difficult to imagine how such a burden might

be met.

The error of enforcing these heightened standards

was highlighted by subsequent events in the proceeding.

After the State’s presentation at trial made clear that the

State would not offer Petitioners’ defense and evidence and

that the Petitioners’ interests would be impaired, both the

district court and the Fifth Circuit still denied intervention.

Neither court addressed the fact that Petitioners’ defenses

and evidence had undeniably been excluded from the

proceedings as a result of the denial of intervention. The

district court order contains no discussion whatsoever of the

facts. 188a-189a. By its misplaced reliance on the "law of the

case” doctrine, the second panel of the Fifth Circuit

successfully evaded the impact of its earlier decision.6 Thus,

although Petitioners were proven correct in their belief that

the State would not adequately represent their interests,

their claims were never properly addressed.

Nor can Petitioners find consolation in the fact that

the Fifth Circuit held out the possibility of a new Title VI

action directed at the discriminatory effect of the Texas

Index. This invitation serves only to emphasize how the

courts below subverted the very purposes of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure by denying intervention. Although

it is true that Petitioners could file a new complaint,

disposition would have to await the completion of a lengthy

and costly new round of litigation on the identical issues

6The assertion by the court below that the first panel "implicitly"

passed upon the adequacy of Petitioners’ Texas Index claims as a basis

for intervention if the evidence were not presented by the State is

patently wrong.

29

raised in the instant case.7 This clearly frustrates the goal

of judicial economy and fairness which inform Fed. R. Civ.

P. 24, whose purpose is "to foster economy of judicial

administration and to protect non-parties from having their

interests adversely affected by litigation conducted without

their participation." Stallworth v. Monsanto Co., 558 F.2d

257, 265 (5th Cir. 1977); United States v. Texas Eastern

Transmission Corporation, 923 F.2d 410, 412 (5th Cir. 1991)

(quoting Smuck v. Hobson, 408 F.2d 175, 179 (D.C. Cir.

1969) (en banc))', Washington Electric Company v.

Massachusetts Municipal Electric Company, 922 F.2d 92 (2d

Cir. 1990); Venegas v. Skaggs, 867 F.2d 527, 530 (9th Cir.)

ajfd 495 U.S. 82 (1989).

The effects of the decisions denying intervention in

this action on the ability of African-American Petitioners to

protect their interests in being free of discrimination in

seeking admissions to the Law School are only exacerbated

by the manifest unfairness of excluding the class of victims

of prior constitutional and statutoiy discrimination from

proceedings which will have an impact on the very programs

designed to remedy prior violations against African-

Americans. The unseemly prospect of relegating Petitioners

to the role of sideline observers to proceedings that may

affect their own future educational opportunities requires

7In fact, the suggested new action would more successfully create a

Gordian knot than assure the vindication of all potential interests. Were

Petitioners to be successful in an attack alleging the discriminatory effect

of the Texas Index either through the judgment of a court or agency or

consent judgment with the State, any remedy would be subject to attack

by plaintiffs or any similarly situated non-minority Law School applicant.

See Martin v. Wilks, 490 U.S. 755 (1989). Assuming that the same

standard of intervention applied to white movants for intervention as was

used for Petitioners, their sole means of recourse would be the initiation

of a new action against the State, from which Petitioners again would

presumably be excluded. With no reasonable end in sight to these

needlessly restricted hearings, the effect on the fair and efficient

functioning of the judicial process would be grave.

30

the grant of certiorari in this case.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, Petitioners Thurgood

Marshall Legal Society and Black Pre-Law Association

respectfully pray that a Writ of Certiorari be issued to

review the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit in this matter.

Respectfully submitted,

Elaine R. Jones

Director Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

Charles Stephen Ralston

* Dennis D. Parker

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

* Counsel o f Record

Anthony P. Griffin

Anthony P. Griffin, Inc.

1115 Moody

Galveston, TX 77550

(409) 763-0386

David Van Os

Van Os & Owen

900 Congress Avenue

Suite 400

Austin, TX 78701

(512) 479-6155

Janell M. Byrd

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W. Suite 301

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 682-1300

Attorneys for Petitioners