McPherson, Sr. v. School District No. 186 of Springfield Illinois Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellees

Public Court Documents

March 14, 2001

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McPherson, Sr. v. School District No. 186 of Springfield Illinois Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellees, 2001. 322b6fc6-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4c503372-5777-46af-a911-ce63fb3d92cc/mcpherson-sr-v-school-district-no-186-of-springfield-illinois-brief-of-plaintiffs-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

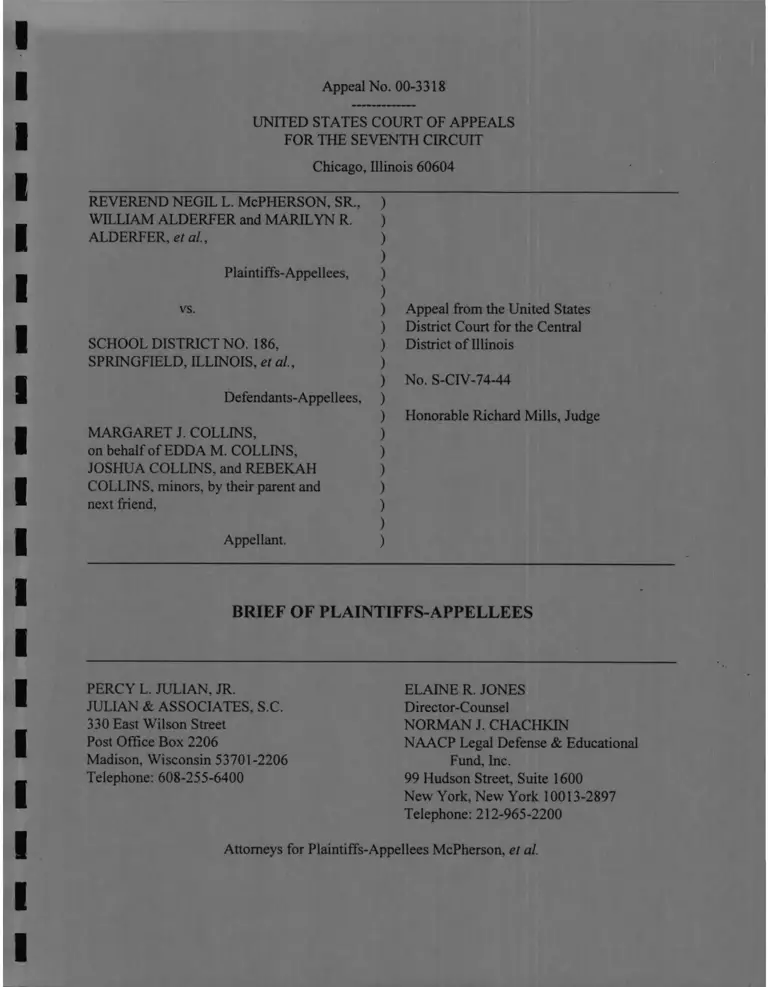

Appeal No. 00-3318

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

Chicago, Illinois 60604

REVEREND NEGIL L. McPHERSON, SR.,

WILLIAM ALDERFER and MARILYN R.

ALDERFER, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

vs.

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 186,

SPRINGFIELD, ILLINOIS, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

MARGARET J. COLLINS,

on behalf of EDDA M. COLLINS,

JOSHUA COLLINS, and REBEKAH

COLLINS, minors, by their parent and

next friend,

Appellant.

)

)

)

)

)

)

) Appeal from the United States

) District Court for the Central

) District of Illinois

)

) No. S-CIV-74-44

)

) Honorable Richard Mills, Judge

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

PERCY L. JULIAN, JR.

JULIAN & ASSOCIATES, S.C.

330 East Wilson Street

Post Office Box 2206

Madison, Wisconsin 53701-2206

Telephone: 608-255-6400

ELAINE R. JONES

Director-Counsel

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

NAACP Legal Defense & Educational

Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013-2897

Telephone: 212-965-2200

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees McPherson, et al.

Appellate Court No: 00-3318

CIRCUIT RULE 26.1 DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

(formerly known as Certificate of Interest)

Short Caption: McPherson v. School District No. 186______________________

To enable the judges to determine whether recusal is necessary or appropriate, an attorney for a non-governmental party

or amicus curiae, or a private attorney representing a government party, must furnish a disclosure statement stating the

following information in compliance with Circuit Rule 26.1 and Fed. R. App. P. 26.1 . Each attorney is asked to

complete and file a Disclosure Statement with the Clerk of the Court as soon as possible after the appeal is

docketed in this Court. Counsel is required to complete the entire statement and to use N/A for any information

that is not applicable.

(1) The full name of every party that the attorney represents in the case (if the party is a corporation, you must provide the

corporate disclosure information required by Fed. R. App. P. 26.1 by completing the item #3):

Marilyn R. Alderfer. William Alderfer, Carol A. Bonds. Jennifer Bridges. Kristin Bridges.

Patrick Bridges, Roger Peon Bridges. Beverlv A. Davis. Carrie L. Davis. Catherine D. Davis.

Charles C. Davis, Debra A. Davis, George C. Davis. Jr.. Homerann Davis. Kathlv L. Davis. Lisa

C. Davis. Marilyn W, Davis, Robert E. Davis. Roberta M. Davis. Donald Echols. Joyce F.

Echols, Kevin Echols. Sonia Echols. Tate L. Echols. David S. Ellsworth. Marv E. Ellsworth.

Rebecca Ellsworth, Gary E. Freeman. Vanzella Freeman. Constance D. Garrett. William C.

Garrett. Ida Welbom Jackson, Brad P. Jones. David L. Jones. Jerry W. Jones. Michael J. Jones.

Robert B. Jones, Rosa D, Jones, Toni M. Jones. Alisa M. Kimble. Chervl D. Kimble. Elsie I,.

Kimble, Gregory' A, Kimble, Jeffrey L. Kimble. Gennea Logan. Willis Logan, Charles

McClanahan, Clarence McClanahan. Donald McClanahan. Elaine McClanahan. Herds

McClanahan, Alan R. McCoy, Andrew W, McCoy. Barbara Ann McCov. John K. McCov.

Kenneth D, McCoy, Rev. Ophilis McCoy. Ronald E. McCoy. Angela Marie McPherson, Rev.

Nigel McPherson, Sr.. Nigel Livingston McPherson. Jr.. Carol Mills. Eleanor S. Mills. Julia

Mills, Susan Mills, Beth E. Potter, Gregory C. Potter. Kristen A. Potter. Marv Jo Potter. Carol

Readus, Dessie Readus, Fannv Readus. Jackie Readus. Lvnn Readus, Mvra Readus. Shea

Readus, Paul Sandefur, Ginger Shelton, Glenn Shelton. Glenn Shelton. II, Leslie A. Shelton

Ronda J, Shelton, Sidney F. Shelton. Wendv L. Shelton. Billie Sue Shiner. Eduardo M. Shiner.

Larry E. Shiner, Laurence F. Shiner. Suzanna K. Shiner. Michelle V. Shoultz. Rev. Rudolph S.

Shoultz, Tonv E. Shoultz, Eve Siebert. Mark Siebert. Mark Siebert. Jr.. Sonia Siebert. Arthur M.

Smith, Heather L. Smith, Patricia B. Smith. Chaney Statler. Deanna Statler. Stacv Statler. Carol

Washington, Crissie Washington, Kenny Washington. Lawrence Washington. Wendv

Washington, Denise L. Winston, Jr.. Rupert S. Winston. Valerie M. Winston. Gloria M.

Winston. Rupert S. Winston, Jr.; and (a) all those school children within District No. 186 or

eligible to attend schools within School District No. 186 who attend segregated or substantially

segregated schools and who mav receive unequal educational opportunities, and fbj all those

school children who are within School District No. 186 or eligible to attend the schools within

said district, who will be attending segregated schools or substantially segregated schools, and a

segregated school system, and who will be receiving unequal educational opportunity.

(2) The names of all law firms whose partners or associates have appeared for the party in the case (including

proceedings in the district court or before an administrative agency) or are expected to appear for the party in this court:

Julian & Associates, S.C.; NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund. Inc.: Edward Tarahilda:

Lawrence E. Rothstein_____

(3) If the party or amicus is a corporation:

i) Identify all its parent corporations, if any; and

___________ N/A_______

ii) list any publicly held company that owns 10% or more of the party's or amicus' stock:

___________ N/A

The Court prefers the statement be filed immediately following docketing; but, the disclosure statement shall be filed

with the principal brief or upon the filing of a motion, response, petition, or answer in this court, whichever occurs first.

The attorney furnishing the statement must file an amended statement to reflect any material changes in the required

information. The text of the statement (i.e. caption omitted) shall also be included in front of the table of contents of the

party's main brief.

r \

Attorney's Signature;---^/^ Date: 3 / V / L > /

Attorney's Printed Name:

/ ^ ' /

Norman J. Chachkin

Address: NAACP Leeal Defense & Educational Fund. Inc.

99 Hudson Street, lb* floor

New York New York 10013-2897

Phone Number: 212-965-2200

Fax Number: 212-219-2052

E-Mail Address: nchachkin a naacpldf.org

CIRCUIT RULE 26.1 DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

(formerly known as Certificate of Interest)

Appellate Court No: 00-3318

Short Caption: McPherson v. School District No. 186__________________________

To enable the judges to determine whether recusal is necessary or appropriate, an attorney for a non-governmental party

or amicus curiae, or a private attorney representing a government party, must furnish a disclosure statement stating the '

following information in compliance with C ircuit Rule 26.1 and Fed. R. App. P. 26.1 Each attorney is asked u f

complete and file a Disclosure Statement with the Clerk of the Court as soon as possible after the appeal is

docketed in this Court. Counsel is required to complete the entire statement and to use N/A for anv information

that is not applicable.

(1) The full name of every party that the attorney represents in the case (if the partv is a corporation, you must provide the

corporate disclosure information required by Fed. R. App. P. 26.1 by completing the item #3):

Marilyn R. Alderfer, William Alderfer, Carol A. Bonds, Jennifer Bridges. Kristin Bridges,

Patrick Bridges, Roger Peon Bridges, Beverlv A. Davis, Carrie L. Davis. Catherine D. Davis

Charles C. Davis, Debra A. Davis, George C. Davis, Jr., Homerann Davis. Kathlv I.. Davis T ka

C. Davis. Marilvn W. Davis. Robert E. Davis. Roberta M. Davis. Donald Echols. Jnvre F

Echols. Kevin Echols. Sonia Echols. Tate L. Echols. David S. Ellsworth. Marv F FINwnrth

Rebecca Ellsworth. Gary E. Freeman. Vanzella Freeman. Constance P Garrett. William C

Garrett. Ida Welbom Jackson, Brad P. Jones. David L. Jones. Jem' W. Jones, Michael .1 lone.

Robert B. Jones. Rosa D. Jones, Toni M. Jones. Alisa M. Kimble. Chervl D. Kimble. Elsie T

Kimble. Gregory A. Kimble, Jeffrey L. Kimble. Gennea Logan. Willis Logan. Charles

McClanahan. Clarence McClanahan, Donald McClanahan Elaine McClanahan. Hertis

McClanahan. Alan R. McCoy, Andrew VC McCov. Barbara Ann McCoy, John K. McCnv

Kenneth D. McCoy, Rev. Ophilis McCov, Ronald E. McCov, Angela Marie McPherson. Rev.

Nigel McPherson. Sr.. Nigel Livingston McPherson. Jr.. Carol Mills. Eleanor S Mills. Julia

Mills. Susan Mills, Beth E. Potter, Gregory C. Potter, Kristen A. Potter. Marv Jo Potter. Carnl

Readus. Dessie Readus, Fannv Readus. Jackie Readus. Lvnn Readus. Mvra Readus. Shea

Readus. Paul Sandefur, Ginger Shelton. Glenn Shelton. Glenn Shelton. II. Leslie A. Shelton

Ronda J. Shelton. Sidney F. Shelton. Wendv L. Shelton. Billie Sue Shiner Eduardo M. Shiner

Larry E. Shiner., Laurence F. Shiner, Suzanna K Shiner. Michelle V. Shoultz. Rev. Rudolnh S

Shoultz. Tony E. Shoultz, Eve Siebert. Mark Siebert, Mark Siebert. Jr.. Sonia Siebert. Arthur M

Smith. Heather L. Smith. Patricia B. Smith, Chanev Statler. Deanna Statler, Stacv Statler. Carol

Ŵashington, Crissie Washington, Kennv Washington. Lawrence Washington. Wendv

Washington, Denise L. Winston. Jr.. Rupert S. Winston. Valerie M. Winston. Gloria M

Winston. Rupert S. Winston, Jr.; and (a) all those school children within District No 1 8b nr

eligible to attend schools within School District No. 186 who attend seereaated or substantially

segregated schools and who may receive unequal educational opportunities, and (b) all those

school children who are within School District No. 1 86 or eligible to attend the schools within

said district, who will be attending segregated schools or substantially segregated schools, and a

segregated school system, and who will be receiving unequal educational opportunity.

Julian & Associates, S.C.; NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund. Inc.: Edward Tarahilria-

Lawrence E. Rothstein _________________ 1

(3) If the party or amicus is a corporation:

i) Identify all its parent corporations, if any; and

___________ N/A_________ ________________ _______________________

ii) list any publicly held company that owns 10% or more of the party's or amicus’ stock:

___________ N/A

The Court prefers the statement be filed immediately following docketing; but, the disclosure statement shall be filed

with the principal brief or upon the filing of a motion, response, petition, or answer in this court, whichever occurs first

The attorney furnishing the statement must file an amended statement to reflect any material changes in the required

information. The text of the statement (i.e. caption omitted) shall also be included in front of the table of contents ofthe

Attorney's Signature

Attorney's Printed Name: Percy L. Julian Jr

Date: ~

Address: Julian & Associates, S.C.

--------------------------------- 330 East Wilson Street. P.O. Box 2206

Madison. Wisconsin 53701-2206

Phone Number: 608-255-6400

Fax Number: 608-255-8933

E-Mail Address: iulianfa'iulian.com

Table of Authorities ...................................................................................................................ii

Statement o f Jurisdiction .......................................................................................................... 1

I. District Court’s Jurisdiction ................................................................................ 2

II. Appellate Jurisdiction ...........................................................................................2

Statement of the Issues .......................................................................................................... 3

Statement of the Case .................................................................................................................3

Statement of F a c ts ....................................................................................................................... 7

Summary of Argument .......................................................................................................... 11

ARGUMENT ............................................................................................................................13

I Collins Failed To Establish That She Was Entitled

To Intervene In This Lawsuit As A Matter Of Right ............................ 13

A. Collins failed to seek intervention on

a timely b a s i s ......................................................................................... 15

B. Collins failed to establish that she has a

legally protectable interest in the subject

matter o f the action ............................................................................ 17

C. Collins failed to demonstrate inadequacy

o f representation ...................................................................................19

II Collins Lacks Standing To Raise Other Issues On This Appeal . . . . 2 3

Conclusion ................................................................................................................... 24

Certificate Pursuant to Fed. R. App. P. 32(a)(7)(C )............................................................ 25

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

i

Certificate o f Service ............................................................................................................ 25

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Air Line Stewards and Stewardesses Ass ’n v. American Airlines, Inc.,

455 F.2d 101 (7th Cir. 1972) .....................................................................................18

Anderson v. Hardman,

No. 00-1171 (7th Cir. Feb. 23, 2001) ........................................................................ 13

Armstrong v. Board ofSch. Dirs. o f Milwaukee,

616 F.2d 327 (7th Cir. 1980) .................................................................................. 23n

B.H. v. McDonald,

49 F.3d 294 (7th Cir. 1995) ....................................................................................... 22

Bradley v. Milliken,

828 F.2d 1186 (6th Cir. 1987) .......................................................................... 17n,22

Donaldson v. United States,

400 U.S. 517 (1971) ............................................................................................. . 19

Felzen v. Andreas,

134 F.3d 873 (7th Cir. 1998), a ff’dper curiam

sub nom. California Pub. Employees ' Ret.

Sys. v. Felzen, 525 U.S. 1052 (1999) ...................................................................... 23

Gautreaux v. Pierce,

743 F.2d 526 (7th Cir. 1984) ..................................................................................... 18

In re Associated Press,

162 F.3d 503 (7th Cir. 1998) .............................................................................. 23,24

TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued)

Page

ii

Cases (continued):

In re Brand Name Prescription Drugs Antitrust Litig.,

115 F.3d 456 (7th Cir. 1997) ............................................................... ..................... 23

Jenkins v. Missouri,

78 F.3d 1270 (8th Cir. 1996) ..................................................................................... 22

Marino v. Ortiz,

484 U.S. 301 (1988) .................................................................................................. 23

McPherson v. School Dist. No. 186,

465 F. Supp. 749 (S.D. 111. 1978) .......................................................................... 23n

McPherson v. School Dist. No. 186,

426 F. Supp. 173 (S.D. 111. 1976) ..................................................................... 4, 23n

People Who Care v. Rockford Bd. ofEduc.,

68 F.3d 172 (7th Cir. 1995) .............................................................................. 13n, 14

Smuck v. Hobson,

408 F.2d 175 (D.C. Cir. 1969) ................................................................................ 18

Sokaogon Chippewa Cmty. v. Babbitt,

214 F.3d 941 (7th Cir. 2000) ............................................................................ l 3n? 14

Solid Waste Agency . U.S. Army Corps o f Engineers,

101 F.3d 503 (7th Cir. 1996) .................................................................................. 19n

United States v. South Bend Cmtv. Sch. Corp.,

710 F.2d 394 (7th Cir. 1983), cert, denied,

466 U.S. 926 (1984) ........................................................................................... 16?20

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

United States v. South Bend Cmty. Sch. Corp.,

692 F.2d 623 (7th Cir. 1982) ............... 19, 23n

Cases (continued):

Wade v. Goldschmidt,

673 F.2d 182 (7th Cir. 1982) ............................................................................ 17, 19n

Statutes and Rules:

28 U.S.C. § 1291 .2

28 U.S.C. § 1292 ................................................................................................................... 6n

28 U.S.C. § 1331 ......................................................................................................................... 2

28 U.S.C. § 1343 2

P.L. 95-408. 92 Stat. 883 (1978) ......................................................................................... 2n

Fed. R. App. P. 28 .................................................................................................................13

Fed. R. Civ. P. 11 16n

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23 .......................................................................................................................3

Fed. R. Civ. P. 24 ......................................................................................................6. 11. 13n

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

IV

Appeal No. 00-3318

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

Chicago, Illinois 60604

REVEREND NEGIL L. McPHERSON, SR., )

WILLIAM ALDERFER and MARILYN R. )

ALDERFER, et al., )

)

Plaintiffs-Appellees. )

)

vs- ) Appeal from the United States

) District Court for the Central

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 186. ) District of Illinois

SPRINGFIELD. ILLINOIS, et al., )

) No. S-CIV-74-44

Defendants-Appellees. )

) Honorable Richard Mills, Judge

MARGARET J. COLLINS, )

on behalf of EDDA M. COLLINS. )

JOSHUA COLLINS, and REBEKAH )

COLLINS, minors, by their parent and )

next friend, )

)

Appellant. )

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

Statement of Jurisdiction

The Statement of Jurisdiction of Appellant Collins (hereinafter, “Collins”) is not

complete or correct.

1

I. District Court’s Jurisdiction

This action was commenced on April 11, 1974 in the United States District Court

for the Southern District o f Illinois' to desegregate the public schools o f School District

No. 186, Springfield, Illinois {hereinafter, “School District”) as required by the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution and various federal statutes. The District

Court accordingly has jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331, 1343(3) and 1343(4).

II. Appellate Jurisdiction

On July 28, 2000. this Court entered an Order in Appeal No. 00-2149 directing the

Clerk ot the court below to treat Collins' April 7, 2000 “Petition for Permission to Appeal

Under 28 USCS 1292 (b)” (App’t Br. App. A108-A109) as a timely Notice o f Appeal

from the District Court s March 27, 2000 denial o f Collins’ motion to intervene. Implicit

in that direction is the determination that the March 27, 2000 Order below was a final

determination of Collins' right to intervene.2 and this Court therefore has jurisdiction over

this appeal pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1291.

'In 1979, the Central District of Illinois was created by P.L. 95-408, §§ 4,5, 92 Stat. 883,

884-85 (1978) and the matter was transferred to that federal judicial district.

"Plaintiffs-appellees McPherson, et al. (hereinafter, “plaintiffs”) believe, for the reasons set

forth in "Plaintiffs’ Statement in Opposition to Appellant’s Circuit Rule 3 Docketing Statement

and in Response to the School District’s Motion to Dismiss” (filed in this Court October 26, 2000),

at 5-8. the March 27, 2000 order below is not appealable. A similar argument was made in the

School District’s October 2, 2000 “Motion to Dismiss Appeal,” at 6 (“Because the Order is not

final as to the minor children, the Appellate Court has no jurisdiction under 28 USC § 1291"), 8

(“the March 27. 2000 Orders are interlocutory in nature and pursuant to 28 USC § 1291, therefore,

not appealable”). However, this Court on December 18, 2000 denied the “Motion to Dismiss

Appeal” and we therefore proceed on the understanding that the March 27 Order is appealable in

this Court.

2

Statement of the Issues

1. Did the District Court err in denying Collins’ motion to intervene as o f right in

this action?

2. Does Collins lack standing to raise other issues on this appeal?

Statement of the Case

This class action lawsuit was filed on April 11, 1974 to desegregate the public

schools of Springfield. Illinois. On December 27, 1974, the District Court approved and

entered a Consent Decree executed by the parties (App’t Br. App. A 1-A 12) in which, inter

alia. the Court certified the action under Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(a) and (b)(2) on behalf of a

class consisting of

(a) all those school children within District No. 186 or eligible to attend

schools within School District No. 186 who attend segregated or

substantially segregated schools and who may receive unequal educational

opportunities; and (b) all those school children who are within School

District No. 186 or eligible to attend the schools within said district, who

will be attending segregated schools or substantially segregated schools, and -

a segregated school system, and who will be receiving unequal educational

opportunity.

Consent Decree, ^ 2 (App t Br. App. A2-A3). The Consent Decree also contained an

explicit finding that

Various actions and omissions of the Board of Education of School District

No. 186, and of officials of the district, when considered together and

cumulatively, have resulted in violations of the Fourteenth Amendment by

contributing to the creation, intensification, and perpetuation of racial

segregation in and among the public schools of Springfield School District

No. 186 not limited to any physically or otherwise separable portion of the

3

district. Defendants have an affirmative obligation to eliminate and prevent

racial segregation in the public schools o f District No. 186.

Id., U 5 (App’t Br. App. A4). The Decree directed the School District to submit a remedial

plan for the Court’s consideration (see App’t Br. App. at A7 U 4). Following further

proceedings, the District Court ordered the implementation of the District’s plan for

secondary schools and an alternative proposed by plaintiffs for elementary schools.

McPherson v. School Dist. No. 186, 426 F. Supp. 173 (S.D. 111. 1976).

On January 7,2000, the School District filed a motion to modify the District Court’s

1976 Order to reflect a new grade structure, building utilization, and pupil assignment

plan, together with a supporting memorandum (App’t Br. App. A13-A36). Plaintiffs

responded on January 24. 2000, advising the Court that “in light o f the enrollments

projected to result from implementation of the modifications sought by the District

[citations omitted], plaintiffs do not interpose any objection at this time to the Motion.”3

(However, plaintiffs requested that the Court approve the changes on an interim basis only

and reserved the right to object after actual school enrollment figures became available

following implementation of the changes.) On January 26, 2000, the District Court issued

its Order (entered on the docket January 28. 2000) granting the Motion and directing that

plaintiffs file any objections within 30 days after the School District filed its report of

actual school enrollments (App’t Br. App. A37-A39).

’Appellant did not include plaintiffs' response in her Short Appendix. It is reprinted in the

Supplemental Appendix submitted with the Appellee Brief of School District No 186 at SA36-SA

38.

4

On February 7, 2000, Collins, the present Appellant, proceeding pro se on behalf of

her three minor children, whom she identified as “Intervenors-Objectors” and as ‘'member

of the class protected by plaintiffs' class action,” filed an “Objection to Reorganization

Plan for Springfield Public School District #186” with the District Court (App’t Br. App.

A43-A48). Collins asked that the District Court

place a permanent injunction against the District 186 redistricting plan and

appoint a Master to ensure that African American parents, and students are

not segregated and that their rights are not violated. Further that equal

protection of the law be returned to all citizens of the Springfield Public

School District 186 and that equitable relief is appropriate in this case and

reasonable attorneys fees be paid to petitioner-objectors' attorney at the end

of any trial.

(App’t Br. App. A47.)4 The trial court, while noting that it had already granted the

District s motion, directed the parties' counsel to submit responses to Collins’ “Objection”

(see App't Br. App. A51-A53). The District (id. at A54-A59) and plaintiffs5 did so on

February 23, 2000. Collins replied on February 28, 2000 (id. at A65-A73); the School

District moved on March 7, 2000 to strike the reply on the ground that it was unauthorized

by the local rules or for leave to file an appended Surreply.6 At this point, on March 14,

2000. Collins moved to "quash" the Surreply and sought, for the first time, to intervene as

4This "Objection" was amended by Collins in respects not material to this appeal on

February 7, 2000 (App’t Br. App. A49-A50).

5Again. Collins failed to include this document in her Short Appendix; it is reprinted at

Supp. App. SA39-SA48a.

6Collins also omitted these pleadings from her Short Appendix but they are not material to

the issues before this Court.

5

of right in this litigation pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 24(a)(2) (App’t Br. App. A74-A76).

The School District responded to this pleading on March 23, 2000 (id. at A77-A79)7 and

on March 23, 2000, the court below issued Orders (entered on the docket March 27, 2000)

denying Collins’ “Objection” to the reorganization of district grade structures and

assignments that it had earlier approved (id. at A80-A82), declining to strike either

Collins' Reply or the District’s Surreply, and denying Collins’ request for intervention on

the grounds that it was untimely and that she had not shown inadequacy of representation

(id. at A83-A86).

This appeal ultimately followed.8

?Prior to receiving the District Court's ruling on the request for intervention, although after

that ruling had been issued, plaintiffs also responded to Collins' motion, on March 29, 2000, in a

document omitted from Appellant's Short Appendix that is reprinted at Supp. App. SA49-SA63.

sCollins initially moved below for permission to appeal the District Court’s January 28,

2000 and March 27. 2000 Orders pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b) (see App’t Br. App. A108-

A109). The District Court denied that relief on April 19, 2000 (id. at A113-A116). On April 27,

2000. Collins filed a Notice of Appeal, reprinted at Supp. App. SA64-SA65, “from the Orders of

the District Court entered on February. 9. 2000. March 27, 2000 and April 19, 2000 denying

objections, intervention and injunctive relief." That appeal was docketed in this Court on May 3,

2000 as No. 00-2149. On July 28. 2000. this Court dismissed the appeal as untimely but, as

previously noted, directed the District Court Clerk to treat Collins’ § 1292(b) motion as a timely

filed Notice of Appeal “from the district court's denial of her motion for leave to intervene,” and

the present appeal was docketed as No. 00-3318. (Collins subsequently filed her § 1292(b)

Petition directly with this Court on August 4. 2000. and it was docketed as No. 00-8022; on August

21, this Court dismissed it for lack of jurisdiction since the District Court had not certified its

orders for interlocutory appeal.)

6

Statement of Facts

Reduced to its essentials, this appeal involves disagreements, on the part of a parent

of several minor class members, with class counsel’s handling of this school desegregation

action. The District Court denied the parent’s motion to intervene in the action as a named

party on the grounds of untimeliness and failure to demonstrate inadequacy of

representation by class counsel.

Appellant Collins is a former chairperson of the education committee of the

Springfield. Illinois branch of the NAACP (App’t Br. App. at A93). She believes that her

children have been subjected to racially discriminatory treatment by the Springfield school

system “f[ro]m the very first day that [they] started school in [the district] . . . . [She] first

became aware of this discrimination on/or about 1985'"(id. at A88). Although Collins

filed complaints of discrimination against the School District with the Illinois State Board

of Education and Sangamon County Superintendent o f Schools on September 20, 1999

(see App’t Br. App. at A88), and with the United States Department o f Education on

October 14. 1999 (App’t Br. App. A87-A101). she did not seek any personal involvement

in this litigation until February, 2000 (see id. at A43).

Collins' appearance in the court below followed upon the School District’s January,

2000 submission of a motion seeking approval of alterations in grade structure, building

usage and pupil assignments — the first substantial change in these areas since the District

Court’s initial approval of a desegregation plan in 1976. The School District’s filing

7

indicated that its restructuring plan was developed over a period of years commencing in

1992 {id. at A 16) and included a series of public meetings, as well as a presentation to a

meeting of the local branch of the NAACP in the fall o f 1999 {id. at A 17).

In response to the School District's motion, Collins submitted an “Objection” that

encompassed many subject areas extending beyond the matters raised in the motion {id. at

A43-A48) and sought, inter alia, appointment of a Master {id. at A47). As class counsel

subsequently advised the District Court. Collins’ “Objection” contained “wide-ranging

assertions that the School District operates in a racially discriminatory fashion with respect

to nearly every aspect of its operations, including in areas unlikely to be affected by the

grade structure modifications that are the subject o f the School District’s motion” (Supp.

App. at SA 40). As to complaints that did evidence some connection to the motion, class

counsel told the Court, Collins "allegefd] an unbroken chain of discriminatory conduct

extending back for at least “49 years' and apparently unaffected (in [Collins’] view) by this

Court's remedial Orders, including the remedial plan directed by th[e] Court in 1976”

(Supp. App. at SA 44).

After the District Court rejected Collins' request for disapproval of the School

District s restructuring plan, she sought intervention for her children as new class

representatives in order to litigate these same broad claims {see A74-A75 1 [proposed

intervenors are “representatives o f the plaintiff class”], 2 [proposed intervenors “are being

discriminated against and deprived of equal protection under law as guaranteed by the

8

Constitution”], 3 [the court and class counsel “are failing to represent and protect the Civil

Rights o f African American Children and their parents by not enforcing the Consent

Decree”], 12 [referring court to Collins’ previously filed “Objection” raising “minority

hiring, promotion and retention; or [s/c] other concerns addressed by the Consent

Decree”]).

The District Court denied the motion to intervene by Order entered March 27,2000.

It concluded that the motion was untimely:

. . . Ms. Collins’ motion to intervene is not timely because, in essence, Ms.

Collins is seeking to intervene based upon her belief that the 1976 consent

decree issued by this Court is inadequate to remedy racial discrimination in

the Springfield school district. Because she is attacking a 24 year old Order,

her petition is untimely.

To the extent that Ms. Collins is only attacking Defendant’s motion to

modify, her petition is. nevertheless, untimely as she waited 2Vi months after

Defendant filed its motion before filing her motion to intervene.

(App t Br. App. at A85.) The court also concluded that intervention should be denied

because Collins had not demonstrated inadequacy of representation by class counsel:

Finally, the Court has previously found and again today finds that

Plaintiffs' counsel and Plaintiffs' class adequately represent the interest of

similarly situated individuals in this case, including Ms. Collins and her

children.

(Id. at A86.) In its Order of the same date rejecting Collins’ previously filed “Objection”

to the School District s motion, the court below observed that “[h]er children, as members

of the class, have been admirably represented by Plaintiffs’ counsel, and Plaintiffs’ counsel

has neither indicated an unwillingness nor an inability to continue to represent the class

9

members, including Ms. Collins’ children, in this matter” {id. at A81). The court

continued by noting that it had

ordered Defendant to file the actual school enrollment figures after the

modification occurs once those actual enrollment figures become available

and has given Plaintiffs (through their counsel) 30 days thereafter to file any

objections which they have to the modification. By this means, the Court

will insure compliance with the Consent Order entered by this Court and the

federal statutes upon which the Consent Order was based. McPherson v.

School District No. 186. 465 F. Supp. 749, 753 (C.D. 111. 1978). For these

reasons, Ms. Collins’ pro se objections are denied.

(App’t Br. App. at A82.)

Following entry o f the judgment denying intervention that is the subject of this

appeal, the School District on November 9. 2000 did file with the District Court a “Report

o f Enrollment Figures” for the 2000-01 school year.9 Plaintiffs responded on December 5,

2000.'" After comparing the actual school enrollments to those projected when the

District's request to modify prior Orders had been filed, plaintiffs asked the District Court

to withhold final approval of the new plan until after a report showing enrollments for the

2001-02 school year was available:

[Pjlaintiffs should again be allowed a period of 30 days within which to seek

such additional relief as they may conclude is justified. In the meantime,

plaintiffs' counsel will seek to work with the District to identify problems

and solutions so that better results are achieved in the next school year.

gThis document is reprinted at Supp. App. SA66-SA82.

"This document is reprinted at Supp. App. SA83-SA90.

10

The School District did not object, and on December 13, 2000 the District Court entered

an order to this effect (reprinted at Supp. App. SA91-SA93).

Summary of Argument

I

Intervention was properly denied by the District Court because Collins failed to

meet the minimum requirements of Fed. R. Civ. P. 24(a).

A. Collins did not seek intervention on a timely basis. As a former chairperson of

the education committee of the local branch of the NAACP she had knowledge of the

proposed grade restructuring plan developed over a multi-year period by the School

District. Indeed, in her brief Collins asserts that she has been aware at least since 1985 of

the allegedly discriminatory practices that she sought to challenge by her attempted

intervention. Yet Collins inexplicably and unjustifiably waited until the year 2000, and

after the District Court had approved the new plan for implementation, to seek to enter the

lawsuit as a party.

B. Collins' pleadings fail to demonstrate that she (on behalf of her children) has a

direct and substantial, legally protectable interest in the subject matter o f this litigation that

she is attempting to vindicate through intervention. The congeries o f complaints about

various interactions of her children with school system personnel that she raises have far

too attenuated a connection with the subject matter of this suit to support intervention — to

say nothing ol her complaints about alleged discrimination against school district

employees in the administration of workplace discipline or about the method of electing

school board members. Insofar as her allegations do focus upon the desegregation process,

they are so lacking in meaningful factual detail that they simply do not describe a specific,

legally protected interest that Collins seeks to vindicate by her intervention.

C. Finally, Collins fails to show that the interests o f the plaintiff class — including

her children — in this case are not being adequately represented by class counsel. While

Collins may disagree with various decisions of counsel concerning litigation strategy she

has not raised colorable claims of gross negligence, bad faith or collusion. In the absence

of such a showing, where (as here) a proposed intervenor and an existing party to a suit

share the same overall objective in the litigation, adequacy of representation is presumed

and there is no right to intervene.

II

Collins lacks standing to raise any other issues on this appeal in light of her inability

to demonstrate a right to intervention.

12

ARGUMENT

I

Collins Failed To Establish That She Was

Entitled To Intervene In This Lawsuit

As A Matter Of Right"

Plaintiffs do not doubt the sincerity of Collins' concerns about the operations of the

School District. And we recognize that Collins is proceeding pro se. Nevertheless, it

remains necessary for any litigant, including one representing his or her own interests

without the benefit of counsel, to meet the well-established legal requirements for

intervention before the litigant may become a part}' to a pending action. See, e.g.,

Anderson v. Hardman. No. 00-1171 (7th Cir. Feb. 23. 2001) (dismissingpro se appeal for

failure to comply with Fed. R. App. P. 28 requirement of a comprehensible argument,

noting that the rule "applies equally to pro se litigants, and when a pro se litigant fails to

comply with that rule, we cannot fill the void by crafting arguments and performing the

necessary legal research, see Pelfresne v. Village o f Williams Bay. 917 F.2d 1017,-1023

(7th Cir. 1990). Collins manifestly failed to make the minimum legal showing to support

intervention in this matter.

"In appeals from denials of intervention sought as a matter of right pursuant to Fed. R. Civ.

P. 24(a), this Court reviews determinations of timeliness for abuse of discretion, while its review of

lower court determinations as to other prerequisites for intervention is de novo. Sokaogon

Chippewa Cmty. v. Babbitt, 214 F.3d 941,945 (7th Cir. 2000); People Who Care v. Rockford Bd of

Educ.. 68 F.3d 172, 175 (7th Cir. 1995).

The requirements for intervention as o f right have recently been summarized by this

Court as follows:

Apart from the timeliness requirement, to which we turn later. Rule 24

establishes three requirements for someone seeking to intervene of right: (1)

the applicant must claim an interest relating to the property or transaction

which is the subject of the action, (2) the applicant must be so situated that

the disposition of the action may as a practical matter impair or impede the

applicant's ability to protect that interest, and (3) existing parties must not be

adequate representatives o f the applicant's interest. See Fed. R. Civ. P. 24(a);

7C Wright, Miller & Kane, sec. 1908 (2d ed. 1986).

"The purpose of the [timeliness] requirement is to prevent a tardy intervenor

from derailing a lawsuit within sight o f the terminal. As soon as a

prospective intervenor knows or has reason to know that his interests might

be adversely affected by the outcome of the litigation he must move

promptly to intervene. United States v. South Bend Community Sch. Corp.,

710 F.2d 394, 396 (7th Cir. 1983), quoted in United States v. City o f

Chicago, 870 F.2d 1256, 1263 (7th Cir. 1989). We consider the following

factors to determine whether a motion is timely: (1) the length of time the

intervenor knew or should have known of his interest in the case; (2) the

prejudice caused to the original parties by the delay; (3) the prejudice to the

intervenor if the motion is denied; (4) any other unusual circumstances.

Ragsdale v. Turnock, 941 F.2d 501, 504 (7th Cir. 1991), citing South v. ■

Rowe, 759 F.2d 610. 612 (7th Cir. 1985).

Sokaogon Chippewa Cmty. v. Babbitt, 214 F.3d 941, 945-46, 949 (7lh Cir. 2000). See also

People Who Care v. Rockford Bd. o f Educ.. 68 F.3d 172, 175 (7th Cir. 1995). All four

requirements must be met to justify intervention. Sokaogan Chippewa Cmty., 214 F.3d at

946. We treat only three o f the factors here.

14

A. Collins failed to seek intervention on a timely basis.

The District Court's conclusion that Collins’ motion was untimely is unquestionably

correct and, in any event, is not subject to reversal under the applicable “abuse of

discretion" standard of review, see supra note 11.

As set forth above, Collins seeks to become a party to this action in order to raise a

barrage of claims of systemic and pervasive discrimination by the School District. She

asserts that this policy of discrimination has been the longstanding practice of the

District,12 thus far unaffected by the commencement of this suit, the entry of remedial

orders, or their implementation.1’ Since Collins served as chairperson of the education

committee of the local branch of the NAACP. she could hardly have been ignorant of the

District's plans to alter student assignments and facilities.14 Moreover, she asserts that she

’"Collins informed the District Court in her very first filing in this action that “the

Defendant #186 has repeatedly been made aware of its violation of the Equal Protection Clause by

the Concerning African American Parents' papers and complaints to District #186 School Board

and the District. Board minutes dating can attested to this as can various newspaper articles”

(App't Br. App. at A44).

1 'Collins acknowledges that the school district is subject to the 1974 Consent Decree in this

case but she believes that it “has made no effort to desegregate the schools, diversify the staff or

the classrooms” (App’t Br. App. at A95).

l4The restructuring plan included operation of a new school, Vachel Lindsay, built in the

Koke Mill area of the district. See App't Br. App. at A23, A28. Construction of this school was

one of Collins' specific complaints (see id. at A46. A68). The School District had informed the

District Court of this planned construction in the spring of 1998, leading the local NAACP branch

to submit a protest to the Court about it (id. at A40-A42). One may infer that Collins could hardly

have been unaware of this, but neither she nor the local NAACP branch sought to intervene at that

time.

15

has been aware o f what she characterizes as the failure o f class counsel to represent

adequately the interests of the class — for some time:

Appellant as Co-chair o f the Education Committee for the Springfield

Branch of the NAACP called Percy Julian on a couple occasions along with

the legal chair for the Springfield Branch of the NAACP. Percy Julian was

never interested in representing the concerns of the Branch regarding

discrimination in the Springfield Public School District.

(App’t Br. at 22).13 Collins filed complaints with the State Board o f Education and the

United States Department of Education in the fall of 1999. See supra page 7. Under these

circumstances, Collins' delay in seeking to participate in the case is inexplicable. There

simply was no basis for her waiting until six weeks after the School District filed its

"Motion to Modify Orders” before seeking to intervene, to “leam[ whether] Plaintiff

counsels were . . . going to object to the School District’s 'motion to modify,’” App’t Br. at

19. "As soon as a prospective intervenor knows or has reason to know that his interests

might be adversely affected by the outcome of the litigation he must move promptly to

intervene.” United States v. South Bend Cmty. Sch. Corp., 710 F.2d 394, 396 (7th Cir.

1983). cert, denied. 466 U.S. 926 (1984). Collins' application to intervene was untimely.

’ ’Plaintiffs categorically deny the validity of these charges. We refer to them here only for

the purpose of demonstrating Collins' protracted failure to seek to protect the interests that she now

asserts are being harmed in this litigation. Class counsel have consistently carried out their

responsibilities to the class in this matter, by both prosecuting meritorious issues vigorously and

also by declining to raise issues that lack legal merit. Cf Fed. R. Civ. P. 11. Collins’ belief — or

wish — that the jurisprudence of school desegregation supports various of her claims does not

make it so. nor provide a meritorious basis for intervention.

16

B. Collins failed to establish that she has a legally

protectable interest in the subject matter o f the action.

Collins’ children are unquestionably members of the class on whose behalf this suit

is maintained, and they therefore have an interest in common with other members of the

class in having past unlawful systemic discrimination and segregation on the part of the

School District remedied. But it is far from clear, based on Collins’ pleadings, that the

purpose for which she seeks intervention is really to vindicate such an interest (leaving

aside, for the moment, the question whether that interest is already adequately represented).

Even a cursory review of Collins’ “Objection” to the School District’s January,

2000 motion (App’t Br. App. A43-A48) — and her motion to intervene (id. at A74-75)

that basically incorporates it — reveals that Collins wishes to litigate in this case myriad

specific incidents involving her children16 as well as many other issues that are not

appropriately made a part of a school desegregation suit (for example, complaints of

discrimination “against African American employees in the handling of sexual harassment

charges and other disciplinary actions,” id. at A44 ^ 11 [emphasis added] or complaints

about the method of electing school board members, id. at A47 ^ 28). As this Court

recognized in Wade v. Goldschmidt. 673 F.2d 182. 184 (7th Cir. 1982), “‘In the context of

intervention, the question is not whether a lawsuit should be begun [or defended], but

]6See Bradley v. Milliken, 828 F.2d 1186, 1192 (6lh Cir. 1987) (suggesting that discrete

problem at particular middle school that was focus of concern of proposed intervenors was

insufficient "to establish the necessary ‘direct, substantial interest’ in the overall desegregation suit

required by Rule 24(a)(2)”).

17

whether already initiated litigation should be extended to include additional parties’”

(bracketed material in original) (quoting Smuck v. Hobson, 408 F.2d 175, 179 (D.C. Cir.

1969)). Thus, even if Collins could raise some of these claims “in some lawsuit . . . the

only real question is whether or not [she] can raise [them] by a[n] intervention in [this]

lawsuit,” Gautreaux v. Pierce, 743 F.2d 526. 534 (7th Cir. 1984). As in Gautreaux,

requiring Collins to commence her own litigation to vindicate these claims does not impair

her ability to protect these other interests that she articulates.

With respect to Collins' interest in having prior discrimination by the School

District remedied effectively, her allegations are so lacking in meaningful supporting

factual detail that they provide no basis for the conclusion that she has a specific,

articulable interest in the desegregation process that is not already receiving protection in

this case, or that disposition of the January. 2000 School District Motion has impaired her

ability to protect such an interest. C f Air Line Stewards and Stewardesses A ss’n v.

American Airlines, Inc., 455 F.2d 101 (7,h Cir. 1972) (affirming denial o f intervention to

EEOC at remedy stage of Title Vll case in absence of showing of non-compliance with

district court orders).17 The District Court's denial o f intervention therefore may also be

1 In Air Lines Stewards, this Court interpreted the relevant statutes to limit the

Commission s right to intervene to situations in which it wished to enforce already formulated

remedial decrees that were being ignored or disobeyed. It therefore held the Commission's interest

in a Title VII action in which a settlement had been proposed, but not yet approved, to be

"contingent and not direct, as required by Rule 24(a)(2).” 455 F.2d at 105. By analogy, in the

absence of a showing of inadequacy of representation by class counsel an individual class

member's "interest” in becoming a litigant to enforce the underlying right at issue in the case is not

sufficiently "direct" to warrant intervention.

18

justified on the ground that Collins' pleadings (making appropriate allowances for her pro

se status) do not establish that she has a direct, significant and legally protectable interest

in the proceedings that warrants her entry into the case as a litigant. See Donaldson v.

United States, 400 U.S. 517, 527-31 (1971) (proposed intervenor must show “significantly

protectable interest such as "privilege or "abuse of process’' and not just dissatisfaction

with outcome of proceedings to establish right to enter litigation).

C. Collins failed to demonstrate inadequacy o f representation.

Collins seeks to enter this case in order to achieve the same ultimate goal pursued

by the plaintiff class and class counsel: "compl[iancej with the Consent Decree and

Desegregation Order and the elimination of any “continuing] discrimination] against

African American students and their parents." App't Br‘ at 25. One may infer from her

tilings that she would litigate the matter differently from class counsel were she permitted

to intervene. Nevertheless, where the proposed intervenor and the existing party share “the

same ultimate objective," this Court presumes adequacy of representation in the absence of

a showing of gross negligence, bad faith or collusion. United States v. South BendCmty.

Sch. Corp., 692 F.2d 623. 628 (7th Cir. 1982).18

]&See Solid Waste Agency v. U.S. Army Corps o f Engineers, 101 F.3d 503, 508 (7th Cir.

1996) (adequacy of representation presumed where interests of original party and proposed

intervenor are the same and there is no conflict of interest); Wade v. Goldschmidt, 673 F.2d at 186

n.7 (inadequate representation not established where there was no showing of collusion, adversity

of interest between existing party and proposed intervenor. or failure by existing party to advance

or defend common interest).

19

The District Court held there was no such showing. “[T]he Court has previously

found and again today finds that Plaintiffs’ counsel and Plaintiffs’ class adequately

represent the interest o f similarly situated individuals in this case, including Ms. Collins

and her children” (App’t Br. App. A86). Collins’ Brief utterly fails to demonstrate that

this finding was in error; instead, she irresponsibly charges that “School District 186 and

[the] District Court are in collusion in maintaining racial isolation and segregation of

African American students” (App't Br. at 25 [emphasis added]). “If a parent could

intervene in a school desegregation suit as of right merely by stating his concern in

constitutional terms, or by denouncing the decree rather than seeking to modify it

incrementally, the requirement of adequacy of representation would be a dead letter, and

school desegregation suits would become unmanageable.” United States v. South Bend

Cmty. Sch. Corp., 710 F.2d at 396.

Contrary to Collins' contentions, class counsel have conscientiously sought to

protect the interests of the plaintiff class in this litigation. As described above,- class

counsel did not object to the School District's motion seeking approval o f changes in grade

structure, building utilization, and student assignments based on the projected outcomes o f

those changes supplied by the District — but reserved the right “to seek appropriate relief

from th[e District] Court should actual school enrollments following implementation of the

changes in grade structure and attendance boundaries described in the Motion papers differ

substantially from those projections” (Supp. App. at SA36-SA 37). After the School

20

District’s “Report of Enrollment Figures” was filed in November, 2000, as had been

previously ordered by the District Court, class counsel carefully analyzed the information

provided, and then submitted a Response with the District Court on behalf of plaintiffs. In

this Response, plaintiffs noted that the “actual results achieved under the new plan . . .

show much greater deviations” (id. at SA85), and suggested that it was “unclear whether

these results signify defects in the plan or merely operational problems with its initial

implementation" (id. at SA 86). In particular, the Response noted, at Feitshans Elementary

School (operated under contract by the Edison Schools Corporation with an entirely

voluntary enrollment) “there seems to have been a distinct implementation failure” (id.),

with the result that Feitshans had a 63% minority enrollment. Based upon these

observations, plaintiffs concluded:

Under these circumstances, plaintiffs suggest that final approval o f the new

plan should be pretermitted. The District should be required to file a similar

Report of Enrollment Figures for the 2001-02 school year, and plaintiffs

should again be allowed a period of 30 days within which to seek such

additional relief as they may conclude is justified. In the meantime, -

plaintiffs' counsel will seek to work with the District to identify problems

and solutions so that better results are achieved in the next school year.

(Id. at SA88.)

Thus, class counsel have been attentive to the interest of the class in assuring

effective desegregation of the District's schools. Collins obviously would have preferred

to have had the District Court reject the grade structure and assignment modifications in

their entirety; by contrast, plaintiffs and class counsel have determined that the best course

21

of action is to give the school district a chance to show that the modification plan realizes

its promise to improve desegregation in the schools before seeking judicial intervention.

This disagreement over appropriate litigation strategy does not show inadequacy of

representation. See B.H. v. McDonald. 49 F.3d 294, 297 (7th Cir. 1995) (class counsel's

"refusal to take up [proposed intervenors’] demand for open court hearings . . . does not

reflect inadequate representation, but only [class counsel’s] considered judgment about the

beneficial effects of additional in-chambers conferences”); Bradley v. Milliken, 828 F.2d

1186, 1193 (6th Cir. 1987) ("while the proposed intervenors strongly oppose abandoning

an adversarial role vis-a-vis the Detroit School Board, such a decision is not the equivalent

of 'collusion' with the opposing party . . . we simply cannot find that such differences of

opinion lead to a conclusion that representation has been inadequate”); Jenkins v.

Missouri. 78 F.3d 1270, 1276 (8th Cir. 1996) ("disagreements over the details of the

remedy . . . do not show inadequate representation”).

For all ol these reasons, the denial of intervention below was fully justified. •

22

II

Collins Lacks Standing To Raise

Other Issues On This Appeal19

Collins' brief (at 1) seeks to define other issues to be resolved by this Court on this

appeal, involving the correctness of the District Court’s approval o f the School District’s

Motion to Modify Orders. Because Collins never became a party to this action, she may

not raise such issues on the present appeal. Marino v. Ortiz, 484 U.S. 301, 304 (1988) (per

curiam)-. In re Associated Press, 162 F.3d 503. 506 (7th Cir. 1998); Felzen v. Andreas, 134

F.3d 873 (7th Cir. 1998), a ff’dper curiam sub nom. California Pub. Employees ’ Ret. Sys. v.

Felzen, 525 U.S. 1052 (1999); In re Brand Name Prescription Drugs Antitrust Litig., 115

F.3d 456 (7th Cir. 1997).20

Even if the Court determines that intervention should have been granted, the case

should be remanded to the district court so that a record on the other issues that Collins

'‘'The issue of standing on appeal arises in the first instance in this Court, which therefore

makes a plenary determination on the legal question.

20Armstrong v. Board o f Sch. Dirs. o f Milwaukee, 616 F.2d 327, 367 (7th Cir. 1980, which

states that “an unnamed class member who appears in response to a Rule 23(e) notice and objects

to a settlement has a right to appeal from an adverse judgment,” was decided prior to Marino v.

Ortiz and this Court's decisions following that ruling; we do not believe it continues to represent

the law of the Circuit on the question. A fortiori, in a case such as the present one, in which there

was no “settlement" of the litigation but merely the approval of a post-judgment motion modifying

a remedial order, see App’t Br. at A1-12 (Consent Decree on liability); McPherson v. School Dist.

No. 186, 426 F. Supp. 173 (S.D. 111. 1976) (remedial order); id., 465 F. Supp. 749, 753 (S.D. 111.

1978) (noting, in course of opinion supporting award of attorneys’ fees to plaintiffs, that remedial

“plan is being successfully implemented”), Collins may not appeal the merits without first attaining

party status in the case. See also United States v. South Bend Cmty. Sch. Corp., 692 F.2d at 629

n.6.

23

seeks to raise can be made before this Court considers them. See In re Associated Press,

162 F.3d at 509 (reaching other issues after reversing denial of intervention only “because

the district court necessarily must confront on remand access issues which already have

been briefed before us, [and] considerations of judicial economy counsel that we address

these matters and identify specifically the tasks which the district court must now

undertake”).

Conclusion

1 he judgment below denying intervention should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted.

PERCY L. JULIAN. JR.

JULIAN & ASSOCIATES. S.C.

330 East Wilson Street

Post Office Box 2206

Madison. Wisconsin 53701-2206

Telephone: 608-255-6400

Fund. Inc.

99 Hudson Street. Suite 1600

New York. New York 10013-2897

Telephone: 212-965-2200

ELAINE R. JONES

Director-Counsel

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

NAACP Legal Defense & Educational

Attorneys for Plaintiffs Appellees McPherson, et al.

24

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE

Pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1746,1 hereby declare, under penalty o f perjury on this iH iA

day of March, 2001, that this Brief has been prepared using WordPerfect 8 word

processing software, Times New Roman font, and that the total number of words that must

be counted pursuant to Fed. R. App. P. 32(a)(7)(B), as calculated by that software

program, is 6641.

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this N A day of March, 2001, two copies of the foregoing

Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellees were served upon counsel for the other parties to this appeal,

by depositing the same in the United States mail, first-class postage prepaid, addressed as

follows:

Ms. Margaret J. Collins

1306-A Denison

Springfield. IL 62704

Lorilea Buerkett, Esq.

Eric L. Grenzebach, Esq.

Brown, Flay & Stephens

P.O. Box 2459

Springfield, IL 62705-2459

Norman J./Chachkin