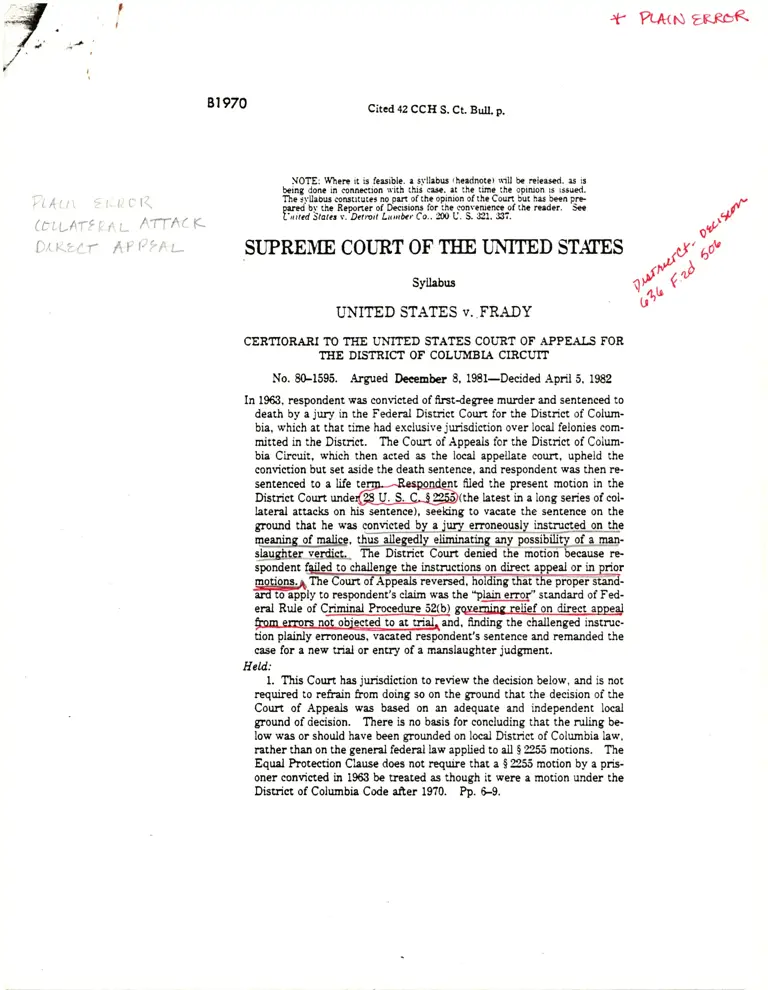

United States v. Frady Court Opinion

Working File

April 5, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. United States v. Frady Court Opinion, 1982. ea3c103d-f092-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4c55446b-861e-4ec8-8fdf-f728a0ffb013/united-states-v-frady-court-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

f R^tN zKSo€.

81970

',1"

( L i sl'rc

( ,t . ..- i,,t t.

NOTE: 'ir'herr it is fersiblc. r sl'llabus theednotet sill be released. as is

beinq donc in connxlion s'ith this cse. rt the time the opiruon rs issued.| ]1,'j'IiiH'flHL'li'.i"ff,31ii::ti?".Hjili,tl'*L.,: Hff" os

/ 1-,r| ( (... Lirrtcd Statec t.'Dctutt Luatr.r Co..200 U. S. 3el. $?.

STPREN/M COURT OF THE t]NIlED STATES

Syllebus

UNITED STATES V. FRADY

CEBTIORAzu TO fiTE UNTTED STATES COI'BT OF APPEAIS FOB

TIIE DISTRICT OF COLIIMBIA CIRCUTT

No. 80-1595. Arped Deeember 8, 1981-Decided April 5, 1982

In 1963, respondent was convicted of firstdegree mr:rder and sentenced to

death by a jury in the Federal District Corrrt for the District of Colum-

bia, which at that time had exciusive jruisdiction over local felonies com-

mitted in the District. The Court of Appeds for the Distriet of Colum-

bia Circuit, which then acted as the local appellate court, upheld the

conviction but set aside the death sentence, and respondent was tien re-

sentencd to a life glt filed the present motion in the

District Cour:t unde (the latest in a Iong series of col-

Iateral ettacks on his sentence), seeking to vacate the sentence on the

groud that he was conlqtd_U_Li

meanins of mdice.#'

slaushter- yedicL

Cited 42 CCH S. Ct. BulL p.

gqfegin&relief on direct appeaJ

and, finding the chdlenged instnrc-

tion plainly erroneous, vacated respondent's sentence and remanded the

case for a new trial or entry of a mansleughter judgment.

Held:

1. This Court has jurisdiction to r.eview the decision below, and is not

required to refrzin from doing so on the ground that the decision of the

Court of Appeals was based on an adequate and independent local

ground of ciecision. There is no basis for concluding that the miing be-

low was or should have been grounded on locd District of Columbia law,

rather than on the general federal law applied to all $ 2255 motions. The

Equd hotection Clause does not require that a $ 2255 morion by a pris-

oner convicted in 196i1 be treated as though it wer"e a motion under the

District of Colunbia Code after 1970. Pp. L9.

smndens failed to chdlence rhe instmcdons on direet aooed or in prior.--

motions. r The Coun of @ns iFAt-ifi e propei -starit-

iffifi;ly to respondeni'i ctaim was the ?Eq!rro5,'rt-a"ia of Fed-

AI,

'ur:no

{

aty

bf

81971cited 42 ccH s. ct. Bull. p.

UNITED STATES U. FRADY

SYllabus

lr

' f '

Lr\

l, l{ ,'

( \'

of the i has been,t

affrmance of the

app€al t!. 10-14.

3. The pnoPer standad for rcview of respondent's conviction is the

I' sendard under which, to obtain collateral

r o contemporaneous objectiolt

111

*Ja,

"

*n"icted defendant must show both..cause" excusing his double

;;";;urri defauit and lactual prejudice" resulting from the erors of

which he comPlirins. h. 15-1?.

;. B;;p;;'";t has failen far shoft of meeting his b,rden of showing

not r"r.iy that the e6o6 at his Eial cleared a pos-sibility of prejudice

;;i,il ti"y worked to his actual and substantial disadvantage. infect-

;; hi";t;; trial with er:ror of constitutionai dimensions' The suong

uiicontradicted evidence of malice in the record' coupled with respond-

ent,s utter failure to come forward n"ith a colorabie claim that he acted

*ithoot malice, disposes of his contention that he suffered such actual

;;;j,;di.J,f".".ir"i of his conviction 19 years later could be justified'

tioi*r"r, an examination of t]le jury instructions shows no substantial

likelihood that the same jury that iound respondent guilty of f:rst{".9*

murder would have .on.tri"d, if only rhe mdice instmctions had been

'o"ttti t

","a,

that his crime was only mansiaughter' fr' l1-2"

-

U. S. App. D. C.-, 636 F' 2d 506' reversed and rernanded'

O'CoNNoB, J., delivered the opinion of the Cor:rt' in which Wrrre'

PowEu, REIoIQUIsT' and Sravixs, JJ'. joined' STEvENS' J" filed a

;;;;;g. .pG. Bucnrux, J., filed an opinion concuring jn the

iJg,r;: Bapr*x^rr, J., frled a dissenting opinion' Buncsn' C' J" and

"lr1filn^r.r* J., rook no part in the consicleration or decision of the case.

2. The Cor.ut of Appeais' use of Rule 52(b)'s '!lgh erorr'.standard to

review respondent's 0 2255 motion was conlt?ry]o long'€stabryl* o1:

plece

81972 Cited 42 CCH S. Ct. BulI. p.

SI]PRENIE COT]RT OF TIIE III{ITED STCIES

No. 80-1595

UNITED STATES, PETITIONER U. JOSEPH C. FBADY

ON WRrI OF CERTIORARI TO TIIE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEAIS F'OR TIIE DTSTBIC'T OF COLLIMBTA CIRCUTT

[April5, 1982]

Jusrrcg O'Coi.tNoR delivered the opinion of the court.

(nrt. 52(Df the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedr:re per-

rdts a crimfnai conviction to be overturned o&gilgg!-plpsal

rbr "plam-eror' in che jury instmctions, .u.ffidE]EiiI-

ant failed to object to the erroneous-instmctions before the

jury retired, 6 required by@ule aQ m this case we are

asked to decide whether the same standard of review appiies

on a collateral challenge rto a criminal conviction brought

under %V. S. C. $2255.

I

A

Joseph Frady, the respondent,. does not dispute that nine-

teen years ago he and Richard Gordon killed T-qlq3aEgrr4gI_

in the front room of the victim's house in Washington, D. C.

Nonetheless, because the resolution of this case depends on

what the jury learned about Frady's crime, we must briefly

recount what happened, as told by the witnesses at Frady's

trial and summarized by the Courlof Appeals. See Fradgrvfl

United States (Frady I), Lzl U._S._App. D. C. 78, 348 F. ,Ll

84 (en banc), cert. denied, 382 U. S. 909 (1965).

The events leading up to the killing began at about 4:30

p.m. on the afternoon of March 13, 1963, when two women

saw Frady drive slowly by Bennett's house in an old car.

Later, at about 7:00 p.m., Frady, accompanied by Richard

citcd 42 ccH s. ct. Bull. p. 81973

UNITED STATES U. FRADY

Gordon and Gordon's fiend, Elizabeth Rydel' returned to

the same block. on this second trip, Ryder overheard

i:*a, ."y ,.something about- that is thc house over there," at

;il;i poirt roav .ria Gordon looked in rhe direction of the

victim's house.

.lfta, reconnoitering Bennett',s home, Frady, Gordon, and

Ryder drove across town to a restaurant' where they were

;;il; Uy C"o"g" Berurett, Thomas

-Bennett's

brother' At

ifr. t..tir*rrt fryder heard George Bennett teii Frady that

,.he needed time to get the furniture and things settled."

sh" fu heard r*ai ask Bennett ,,if he hit a man in the

.frlri .orfd you breal a rib and fracture or puncture.a lung,

could it kill a person,,? Bennett answered that ..you have to

tit "-** p""fty hard." Just before they Ieft the restaurant'

R;6[&d 6orge Bennett say:."If you do a good job you

will get a bonus."

nVJ*, Gordon, and Frady then set out by car for llth

pr".L, .i.ound the comer from Thomas Bennett',s home,

;h;"; they parked, leaving the motor running' Gordon and

Il;t totti nyder ih"y *"i. goTg'!ust around the corner"'

As Gordon got out, Ryder saw irim reach down and pick up

,o*"tti"g. She could not see exactly what it was',but it

ioof."a Uf. . cuff of a glove or heavy material of some kind."

Alittleafter8:30p.-t.,aneighborheardknockingatthe

front door of Benne-tt s house, fo-llowed by the-noise of a fight

i.-p"G.... At 8:44 p.m.. she cailed the police' Within a

.o,ipte=of minutes; two policemen in a p"t:ol Yago.larrived'

and one of them got oot in time to see Frady and Gordon

emerge from Bennett's front door'

tnslae Bennett's house, police officers later found a sham-

blesofbroken,disorderedfurnitureandblood-spattered

;rU.. Thomas Bennett lay dead in a pool of biood' His

n".i. *a chest had suffered horseshoe-shaped wounds from

tir" t.tA ireel plaies on Frad/s leather boots and his head

*as carea in bjt blows from i broken piece^ of a-table top'

*fri.t, significantly, bore no fingerprints' One of Bennett's

eyes had been knocked from its socket'

81971 cited 42 ccH S. Ct. BulI. p.

UNITSD STATES u. FRADY

Outside,the policeman on foot heard Frady and Gordon ex-

claim, "The cops!" as they emerged from the house. Ttrey

immediately took flight, nrnning around the corner toward

their waiting automobile. Both ofHcers pursued, one on

foot, the other in the police wagon. As Frady and Gordon

ran, one of them threw Thomas Bennett's wallet and a pair of

gloves under a parked car. Frady and Gordon managed to

reach their waiting automobile and scramble into it without

being captured by the officer following on foot, but the patrol

wagon arrived in time to block their departure. One of them

was then heard to remark, 'They've got us." When ar-

rested, Frady and Gordon lvere covered with their victim's

blood. Unlike their victim, however, neither had sustained

an injury, apart from a cut on Gordon's forehead.

B

Although Frady now admits that the eviclence that he and

Gordon caused Bennett's cieath was "overrilhelming,"t at his

trial in the United States District Court for the District of

Columbia Frady defended solely by denying all responsibility

for the killing, suggesting through his attorney that another

man, the real murderer, had been seen leaving the victim's

house while the police were preoecupied apprehending Frady

and Gordon. Consistent with this theory, Frady did not

raise any justification, excuse, or mitigating circumstance.

A jury convicted Frady of flrst-degree murder and robbery,

and sentenced him to death by electrocution.

Sitting en banc, the Court of Appeals for the District of Co-

lumbia Circuit upheld Frady's first-degree murder conviction

by a vote of Ll. Frady I, supra. Apparently ail nine

judges wouid have affirmed a conliction for second-degree

murder.2

'Brief for Appellant in Frady v. United Slales, No. 7L2356 (CADC),

p. LZ @ro se).

'The soie dissenter. Judge J. Skelly Wright. noted that under the law of

the District of Columbia an'tnrent to inflict serious injury, unaccompanied

81975citcd 42 ccH s. ct. Bull. p.

UNITED STATES U. FRADY

Nevertheiess,byavoteofS-l,thecourtsetasideFrad/s

death sentence. The five judges in the majority were unabie

to agree on a rationaie for that result' Four of the flve be-

tievei the procedures used to instmct and poll the jr:ry on the

death p.n"lty were too ambiguous to sustain a sentence of

death.i Thofifth and deciding vote was cast by a judge who

believed the District Cotrrt shouid have adopted, for the flrst

time in the District of Columbia, a procedure bifurcating the

Orrf, *a sentencing phases of Frady's trial' Id"' at 85' 348

F. ia, at 91 (McGowan, J., concutring)' By this narrow

margin, Frady escaped electrocution

Fiady was then resentenced to a life term. Almost immedi-

ately, ire Uegan a long series of c@on his sen-

tence,' cuiminating in the case now before us'

C

Frady initiated the present action by bringing a motion

bv oremeditation, is su.fficient for second degree murder' but 6rst degree

J#;;;;;,'r" "aaiir*

to premeditation, the specific intent to kill"'-F;;i

".untted

stateil-iiavit, rztu' 9' epp' D' c' 78' el n'.13' 348

f. zign. fi n. 13 (Wrisht. J., aissenting in part and concurring in part)

(citations omitted). cert". aeniea, 382 U' S' gOg (1965)' Because Judge

WrigfriU"U"ved the evidence suffrcient only to sustain a verdict that Frady

a"-fii"""t.fy intended,o ,:* Ttromas Bennett' Judge Wright w-ould-have

reversed Frady's conriction for first'degree murder' Id' ' at 9l' 348 F ' 2d'

at tl.--,ii

dirr"nt. TrrE Cgrer Jusrtce (who was then ser"ring as a Circuit

Jrdg. ;; the Court of Appeals)' characterized that view as having "no

basis nithout

"n

,".o.piiin that these jurors.*'ere illiterat: ,I:::::'-

in part).

ii.,-^ttW,A48 F. 2d, at 113 (Burger, J., concuring in pan and dissenting

-'t:;rrrrtt

ed by the Court of Appeals' 204 U' S' App' D' c' 234' 236

o. i. seo F. 2d 506. ;OA n. Z (1980), FradV 6led fgur

^tno=tio.1s=lo

vlFle*,:r

-{pp. D. C. ZB'1. %61

motions to vacate or {

of APPeds decision directing that

Frady's separate ."n .n"". for robbery '"1 'yl"i T",:?":Y,"lty

rather t]ran consecuriv.ty. ctrrtra states v. Fmdy (Frudy //), 1917 u' s'

App. D. C. 69. 607 F. 2d 383 (1979)'

{

81976 citcd 42 ccH s. ct. BulI. p.

,, ('" \

UNITED STATES t" FR^A'DY

under 28 U. S. C. $ 225:0' seeking the vacation of his sen-

tenee because the jury instrrrctions used at his trial in i963

*ere aefectlre. Siecifically, Frady argued that the Court of

Appeals, in cases decided after his trial and appeal' had dis-

apj"ouea instnrctions identicai to those used in his case. As

, e;.*ri"ed by these later mlings,'the judge at Frady's trial

/ fr"Ji.p"op".iy equated intent with malice by stating that "a

*"orreiul ict . . . intentionally done . . . is therefore done

t *iti, or"ti.. aforethought." See 204 U' S' App' D'.C'.?34'

' Zg6 n. O, OgO F. 2d 506; 509 n. 6 (19g0). Also, the trial judge

had inconectly instnrcted the jury lhat "the law infers or

f...o*., foom the use of such weapon in the absence of

Lxphnatory or mitigating circumstances the existence of the

*"Ii.. essential to cuipable homicide.,, See id., at 236, 636

r. za, at 508. In his $ 2255 motion Frady contend.ed that

these instnrctions eompelled the jury to presume malice and

thereby wrongfully eiiminated any possibriilV 9f a man-

,t"rgirier verd'lct, .irr.. ,-rlaughter was defined as culpa-

ble homicide without malice.'

'Section 2255 provides in peninent part that:

,,A prisoner in custody uncler sentence of a court established by Act of

C";g.r; claiming the right to be released,pon the ground that the sen-

t"n.Z *". imposed in vio'iation of the Constitution or laws of the United

States, or thai the co,rt was without jurisdiction to impose such sentence,

or that the sentence was in excess of the ma.ximum authorized by law, or is

othenrise subject to collateral at'tack. ma]' move the court which imposed

the sentence to vacate. set aside or corect the sentence"'

'Frady cited B€lto?r v. United Sfotes, L27 lJ' S' App' D' C' 201'

2}l-;m5: B8Z F. Zd tio, 153-1tl (1957): Green v. Linited States (Green I),

iiz u. s. App. D. C. 98, 9F100, {05 F. 2ci 1368. 136e-13?0 (1968): and

inttedsrates v.wharton, t39 U. S.App.D. C.293.297-298,433 F.2d

151, {A5-156 (19?0). The Govemment ilo". not contest Frady's assenionl

tt"i tir" jury insmtctions were erroneous as clerermined by these late!

rulings.

'Sie, e. g., Fryer v. (JnitedStofes, 93 U. S' 'tpp' D: t' 3'l' T' 201

.F ' 2d

B4;fub. ."n. a"ni"a. B4O U. S. 885 (1953) (manslaughter is 'the unlaurfiri

kiiling of a human being without 1n{!9e'] tgmqhasis deieted); United States

iiiloaon, tSg U. S.ipp.D.C.293,296,133 F. 2d 151, {&l0.970) (md-

81977

Court of Appeds reversed. The court held that the proper

standard to apply to Frady's claim is th{,lain erro5,}taPd;

Cited 42 CCH S. Ct. Buil. p.

UNITED STATES U. FRADY

The District Court deniecl Frady's $ 2255 motion. stating

that Frady should have challenged the jury instntctions on

direct appeal, or in one of his many earlier motions. The

ard relief on dj fro m-ilrro rs no t "o b i Jffi i

il6lTg?6;andDivis v. United States,411 U. S. 233 (1973),

relief on followi

fault at d instmctions to be

plainly erroneous, the court vacated Frad/s sentence and re-

manded the case for a new trial or, more realisticaliy, the en-

try of a judgment of manslaughter. Over a vigorous dissent,

the full Court of Appeals denied the Government a rehearing

en banc.

We granted the Government's petition for a writ of certio-

rari to review whether the Court of Appeals properly in-

voked the 'llain enoy'' standard in considering Frady's be-

lated coilaterai attack.

II

Before we reach the merits, however, we flrst must con-

sider an objection Frady makes to our grant of certiorari.

Frady argues that we shouid refrain from reviewing the deci-

sion below because the issues presented pertain solely to the

ice is *the sole element differentiating murder from manslaughtey'').

Frady also challenged the trial juclge's instruction that: "A person is pre'

sumed to intend the natual [and] probable consequences of his act." See

204 U. S.App. D. C., at 87 n.7,636 F. 2d, at 509 n. ? (1980). Frady

argud that this instmction w:ui unconstitutional under our decision in

Sandstrom v. Montana,l42 U. S. 510 (1.979), in which we heid that a simi-

Iar instnrction that "[t]he law presumes that a percon intends the ordinary

cons€quences of his voluntary acts" might lmpermissibly lead a reasonable

juror to believe the presumption is conclusive. The Corrrt of Appeals re'

frained from deciding this issue, however, so we do not consider it here.

rat

81978 Cited 42 CCH S. Ct. Bull. p.

UNITED STATES u. FRADY

Iocal law of the District of coiumbia, w.ith which we normally

do not intert'ere."

Frady's contention is that the federal cou:ts in the District

of columbia exercise a pr:rely local jurisdictional r,rn.tion

when they nrie on a $ 22EE motion brought by a prisoner con-

victed of a local law offense. T'hus, aclording t'o Frady, the

general federal law controlling the dispositioi of $ 22Si mo_

tions.does !9! apply to his case. Instead, a splcial local

brand of $ 2255 law, developed to implement that'section for

the benefit of local'offenders in the District of columbia, con-trols. Frady conciudes that we should therefore ,.r""u

from disturbing the nriing below, since it is based on an ade-

quate and independent local ground of decision.,

To examine Frady's contention, it is necessary to review

some history. when Frady *as tried in r968,'the united

states District court for the District of columbia had .-*.ro-

sive jurisdiction over local felonies, and the united Strt.,

9oqt of Appeals for the District of columbia circuit a.i.a

".the local appellate court, issuing binding decisions oi p*.tv

locai law. In 19?0, however, ttre oistrict of columbia'court

Reform and Criminal Procedure Act (Court Reform Aci), S4

stat. 473r split the local District of columbia and feJeral

criminal jurisdictions, directing local criminal cases io a

newly created local court system and retaining (with minor

exceptions) only federal criminal cases in the .*i-.tirrg Federal

District Cor:rt and Court of Appeals.

As part of this division of jurisdiction, the court Beform

Act substituted for $ 2285 a new loeal statute controiling col-

'As we said in Fisher v. united'States, 32g u. s. 469, {?6 G946): ,.Mat-

ters relating to law enforeement in the District [of columbia] a"e enrrustea

to the couns of the District. or:r poricy is not to interfere with the roeal

nrles of law which they fashion, sarl in exceptional situarions *treie egre-

gious eror has been committed.,'

_ -'_fody, of course, cloes not argre that we do not have juriscliction under

28 u. s. c. $ 12tl (l) to hear this case, only that we shourd, in our discre.

tion, rcfrain from exercising it.

citcd 42 ccH s. ct. BuIt. p.

UNITED STATES t'. FRADY

lateral relief for those convicted in the new iocal trial court.

See D. C. Code $23-110 (1981). The Act, however, did not

alter the jurisdiction of the federal courts in the District to

hear postconviction motions and appeals brought under

in55, either by prisoners like Frady who were conlicted of

local offenses prior to the Act, or by prisoners convicted in

federal court after the Act.

The cnr.x of Frad/s argument is that the Equai Protection

Clause would be violated unless the Court Reform Act is in-

terpreted as implicitly and retroactively splitting, not just

the District's court system, but also the Districtis law gov-

erning 92255 motions. Aceording to Frady, rhe Equal Fro-

tection Clause requires that a $ Z2SE motion brought by a

prisoner convicted of a local crime in Federai District court

prior to the passage of the Cour:t Reform Act be treated iden-

tically to a motion under iocal D. C. Code $ 2B-110 brought by

a prisoner convicted in the local Superior Court afler the pas-

sage of the Act. Fracly suggests that the Cor:rt of Appeais

for this reason must have nrled on his motion as though it

were subject to the local law developed pursuant to $ 28-110,

and that we should not intenrene in this locai dispute.

Frad/s argument, however, was neither made io the court

below nor foilowed by it. Nowhere in the Court of Appeais,

opinion-or in the submissions to that court or to the district

court'o-is there any hint that there may be peculiarities of

g?255law unique to collateral attack in the District of Colum-

bia. To the contrary, the analysis and authorities cited by

the Court of Appeals make it clear that the court reiied on

the generai federal law controlling all $ 2255 motions, and did

not intend to afford Frady's gJ;Sd motion special treatment

simply because Frady was convicted under the District of Co-

lumbia Code rather than under the United States Code.

'' We note that Frad/s winning pro se bief to the court below, chough

e-\tensively discussing the generd federal law regartling the proper clispo-

sition of $ 2255 motions, nowhere suggested rhat speciai local nries shouid

be applied to the case.

91979

8r980 Cited 42 CCH S. Ct' Bull' P'

UNITED STATES U. FRADY

Moreover, the Court of Appealsr-\1'oulcl have ened had' it

done so. There it n" reaso" to believe that Congress m-

tended the result f"ay =oggests,'

and he does not attempt

the impossiUfe tas't<'li"it-ffiS that it did' Furthermore'

Frad/s .oggtt"oit-io ii" c6ntrary-not*ithtt"nding' the

Equal Protectron'Crt'i'"-a*t *t "quire

that a- motion

brought pursuant'- it-S Zm !t .' p"itoit" convicted in the

Federai District ct*i;igob te'trl;;; "t

though it had

been brougi,t p*l"ilti"blc' coa" ii*i10 after 1970' In

fact. even those ffitl";-ita"*i to"t contemporaneousiy

with those trita ror'itt o*t :-**:I tie tocai court need

not always ue trelii^iatiiLuv' As we noted in Suodn v'

Presslev,4Sg u i' iza izg-3ao n'-iz (19?o' for example'

Dersons .ontttto-i" ir" r*"r courts-are not denied equal pro-

iection of the h*;'diy-b"ttot"'hev' uniike persons con-

victeci in the ftat"A-toi'rts' must 'Orini

c'oliateral challenges

fiff;;;ri.tiont u"fore Art' t juas;'.oncluding

that the'" rt ilor*, we find no basis whateve

H:li'.'ffiil * l*[1riff:#13i#i'{ffi

;1i:h;;ilD55 motions'" rher

merits.

ffi"or.AppearslT^ll:^,.:.*::*S"14*,:rTH:,:T.;fi H

l?? ilS.Hl.B:t:til ffi ",:"t'?11'nili'r'o''*' not toca' ba* Iaw

aoplies to - "pp"tti"l

t""J"ta of a local;ff;" in fecleral cou:t' despite

tt" r".t that the

"fl'#il;i''' "ppri"t

to those convicted of the same

*:

w: Hilii:t H*",gI #, UIT ;!:LI !:1{}illtixmore favorable to

i,.""

"

r".a sa-riilmffi' il" Igt"":.i:S#ftlT.3l'Hi'"'iff

'-Bni"fr ":|ir:f,';lilt!'"'riiil;;";;;to-$255'andwe

mav therefor" '"rv

l'n=t*f**t"11sllirialIt Jt'" Butlctv' Cnited

ff 1;:8i;'d S':ffi ::Tin *:it"n:Y:'E ""IiX {t I

similarities betwe

minded trs: {he ffiil:il;" 9r.t"i11a

law in matters not affected bv

."-".J..i"""r "*Tilffi:ii*:dh.

,;

:.r:l:':

peculiarrv or rocar

concenL" Fisht'

citcd 42 ccH s. ct. BuIl. p.

LINITED STATES T.. FRADY

III

A

may be had to the nrle d-y on appeal'fr;rn"r'irrjil

in" the

"No party may assign as error any portion of the chargeor omission therefrom unless he tbjects thereto b"f;;

:|| r5. ::,T :,.r:., ^.,-o

n.ict ey

.it

s u."ai.i, st a tin g ai. t..iiythe matter ro whjch he objects ;J;iJ;ffirdr';i hiqbjection. "

w-ozl9j-lowever, somewhat tempe$ the severity of Rule30.

.

It- grants the courts of Appeal! the latitude ro correctparticularly egregious er?ors on appeai r.g*di... J" a.r"n-dant's trial defauit:

"Plain errots or defects affecting substantial rights maybe noticed aithough they were n'oi urougrrt to the atten-tion ofthe court."

Ruie 52(b) was intended to afford a means for the promptredress of miscariages of justice.; riy-itr-r;il;J;."*"

Bl 981

Nineteen years after his crime, Frady now complains he

,:T^:.:T!d bI a jury.eroneously instmcted on rhe mean-

on direet

"'The n:le

-merely restated existing

Bl 982

UNITED STATES T.. FRADY

elict in countenancing it, even absent the defencrant's timeiy

assistance in detectins it. The ruiffi N,

balancing of our need td encourage ar trial participants to ,l)t

seek a fair and aceurate trial the first time around against our tT.(\

insistence that obvious injustice be promptly redreised.'r ,.afl,fl

Because it was i how.ever,/ "$^"

the "plain enof' standard is out of plGThen-a prisoner

launches a collateral attack against a criminal conviction after

society's legitimate interest in the finality of the judgment

has been perfected by the e.rpiration of the time aiiowed for

direct rerriew or by the affirmance of the conviction on ap-

peai. Nevertheless, in 1980 the Court of Appeals applied

the 'llain enoy''standard to Frady,s long-delayla S Z55 ,no-

tion, as though the clock had been turnecl back to 196b when

Frady's case was first before the court on direct appeal. In

effect, the court ailowed Frady to take a second appeal fif-

teen years after the first was decicled.

As its justification for this action, the Cor.rt of Appeals

pointed to a singie phrase to be found in our opinion n Dauis

v.Unite! States,4tl U. S. ZBg, Z4C-iZ{.J (19?B). ThereG

asserted-TE5o more lenient standard of waiver shouid

applf'on collateral attack than on direct review. Seizing on

this phrase, the Court of Appeals interpreted ,,no more- le-

nient" as meaning, in effect, no more stringent, and for this

cited 42 ccH s. ct. Bull. p.

''The Courts of Appeals long have recognized that the power g::anted

them by @.lztul-s-to be used sparingly, solely in those circumstinces in,:ule oz\o, tS P Oe Pewhich a miscarriage ofjGtlie nroilforTir-n"ise resuit. see, e. g., (Jnited,

Or-t-- -- ^ ('Plain erfriE er:'or

which is'both obvious and substantial'.

=

error nrie is not a

run-of-the-mill remedy. The intention of the nrle is to serwe the ends of

justice: therefore it is invoked 'onllr in exceptional cireumstances [where

necessaryl to avoid a miscarriage of justice'." (citations omitted)). cer.t. cle-

nied, '150 u. s. 920 (198r): Linited sfales v. DiBened,etto, atz F. 2d490, 494

(CA8 1976) ("This cou:t. along uith eourts in general. have applied the

plain eror rule sparingly and only in situations where it is necessary to do

so to prevent a great misca:riage of justice." (citations omitted)).

Cited 42 CCH S. Ct. BulL p.

UNITED STATES t'. FRADY

reason applied the "plain elToy''standard for direct review to

Frady's collateral challenge, despite long-established con-

trary authority. -,-.-\

. By adopting the same standard of review for $ 2255 tito- -

\ tions as wouid be applied on direct appeal, the Court of Ap

\ peals accorded no significance whatever to the existence of a

LnnA judgment perfected by appeal. Once the defendant's

chanrse.ltqaDped has been lBiyed or e{haustlcs!, however, we

are entitied to presume he stands fairiy and finaily convicted,

especiaily when, as here, he already has had a fair opportu-

nity to present his federal claims to a federal fomm- Our

trial and appellate procedures are not so unreliable that we

may not afford their completed operation any binding effect

beyond the next in a series of endless post-conviction collat-

erai attacks. To the contrary, a final judgment commands

respect.

For this reason, we have Iong and consistently affirrned

that a not do serwice for an

See, a. 9., United States v. A

(19?9); Hill v. United States,368 U. S. 424, 42U29 (1962);

Sunnl v. Large,332 U. S. 174, 181-182 (.1947); Adams v-

t|nited States ex rel. McCann, 317 U. S. 269, 274 (1942);

Glasgout v. Moyer,225lJ. S. 420, 428 (L912); Matter of Greg-

ory, 2L9 U. S. 2L0, zLB (1911). As we recently had occasion

to explain:

"When Congress enacted $ 2255 in 1948, it simplified

the procedure for making a collateral attack on a find

judgment entered in a federal criminai case, but it did

I not purport to modify the basic distinction between di-

I rect review and collateral review. It has, of course,

EerA attact on a flnal The reasons for nar-

rowly limiting the grounds for coilateral attack on final

Br 983

c0\

re-

Bt 984 Citcd 42 CCH S. Ct. BulL p.

UN1TED STATES U. FBADY

judgments are well Isrown and basic to our adversary

system of justice." United States v. Addonizio, 4a2

U. S. 178, 184 (1979) (footnotes omitted).

This citation indicates that the Court of Appeals' ened in re-

viewing Frady's S 2255 motion under the same standard as

would be used on direct appeal, as though collaterai attack

and direct review were interchangeable.

Moreover, only five years ago we expressly stated that thel

plain error standard is inappropriate for the review of a state

I

prisonerrs collateral attack on erroneous jury instntctions: - J

"Orderly procedure requires that the respective adver-

iaries' views as to how the jury should be instnrcted be

presented to the triai judge in time to enable him to de-

liver an accurate eharge and to minimize the risk of com-

mitting reversible enior. It is the rare case in which an

improper instnrction will justify reversai of a criminal

conviction when no objection has been made in the trial

court.

"The Aurden of demonstratin4 that an etrsrteou,s in'

stnr,ction u)as so prejudicial that it will support a collat'

eral attack on the constitutional ualidita of a state

csurts julqment is wm greater than the shwing re-

quired to establish plain error on direct appeal." Hen' -

dercon v. Kibbe,4:11 U. S. 145, lil (197? (emphasis

Seemingly, we could not have made the point with greater

clarity. 0f course, unlike in the case before us, in Kibbe the

@ not a federai, court was under at-

tack, so cogriderations of comiW were at issue that do not

constrain us here. But the Federal Government, no less

than the States, has an interest in the finality of its criminal

judgments. In addition, a federai prisoner like Frady, un:J

like his state counterparts, has already had an opportunity to_l$'$

citcd 42 ccH s. ct. Buu. p.

UNITED STATES u, FRADY

on-9ry a prefemed .status when they

relief.

trial and a fo-

pns-

seek post-conviction

Br 985

In sum, the lower court's use of the "prain erroy', standard

to.review Frad/s |?2EA motion *as contrary to long-estab-

lished law from which we find no reason to deiart. fr. i."r-

flrm the well-settled principle that to obtain .ott"t."a ,.ti.r

"prisoner must clear a significantly higher hurdle tt"rr*oria

exist on direct appeal.,5

ilL,:""T:":_.::J_: i9d'":.,o*y^^tl,_.

proper ireldesd to be used bya gi?tri,ct cpg:t engaged p,rsuanr to $-ZSA {"rti,ffi;;;;ffi;:

-_ongnal criminal rid. W

standard

rEJ.Jusrrcns BnsNNeN and Br"ic6,ruN contend that the p*."a,rot ai"".rir"

of $ 2255 enroC' standard of Ruie i2(b) of

,eEe""I revrew ortfrF

^F.g"inpl trirla The dissenting anaa'cmFEr..-

ff*ffi:'";iffiffit'z# il; i, w'as intended,. nilHH

I

By approvins $ 2285 Rule 12, we belieye congress intended mereiy toauthorize a court in its discretion to use the Fedeil Rures of C"i.irJ ero-cednre to reguiate the conduct ofa $ 225d proceecling. _f .ourt of"pp""l.,

f.or e.xample, could invoke the ,.piain enoy'' stanclarcl on direct review of adistrict court's conduct or a $ zisi hearing, if the court or-.pp""il ro*a

"sufficiently egregious error in the $ 22Ei pioceeding itselfthai'hal noi-u""n

brought ro the atrention of the cristrict coun. Thui, as $ 2256 Rul. ii .ug-gests, under proper cireumstances Rule i2(b) can play a role in $ ZS;proceedings.

^ -{_e {so note that, contrary to the suggestions in the dissenting opinion,

$ 2255 Ru.le 12 does not mandate by irs

-oivn

force the *" oi*v-i",ii.ur*

t his federal elaims in federal

tg!:_ On balance, weTee no baliE

xtr ^ in his concunring opinionl pist, at-, point out that $225dq#Tjt.s that: "If no procedure is specifically prescriUa Uyiffinues' rne ostnct court may proceed in any laurfirl manner not inconsistentwiti these rules, or any applicable statuie, and may

"ppfy

ifr"-f.a.""f

Rules of criminal procednrl or rhe rederal nues'oi'iiitt--ilo.ea*",

whichever it deems more appropriate, to motions filed under the." *i"r.,,

Bl 986 citcd 42 ccH s. ct. BulI. p.

UNITED STATES U. FRADY

B

We believg-the proper stand

tion is tf,. 6rt. *a

".trrt

p".jraiieltandard enunciated

n Davis v. Ynited States,4ll U. S. fgg (1973), and later con-n Davis v. Wted States,4l1 U. S. f35 (1973), and later con-

firmed and extend ed, rn Francis v. Henderson, 425 U . S. 536

(1976), afi W433 U.S. 72 (1977).

Under this standard, to obtain collateral relief besed-quld-

qIIgEtto-YirJsb-EL!9lL- emPoralleoYs objectioLwas qade' a

dffiEea a efenEEt-mffi " excusin g his

double procedr:ral default, and (2) "actual prejudice" result-

ing from the enorc of which he compiains. In applying this

dual standard to the case before us, we it unnecessarrr to

t-----,,,#

w because we are

confident he suffered no actuai prej of a degree suffr-

cient to justrfy collateral relief nineteen years after his

crime.td

nrle of civii or criminal procedure. The Advisory Cnrnmittee Not*

$ 2255 Rule 1? refers the reader 'for discussion" of possible restrictions on

til usiliffi nries of procedure to the Note to the andogous provision

governing proceedings under 28 U. S. C. g?9,il, $ 2254 Rule 11 (which pro-

oidest '"rt,e Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, to the extent that they are

not inconsistent with these mles, may be applied' when appropriate, to pe'

titions filed under these nrles."). The Note to $ 2254 Rule 11 expiains that

the nrle "allow[s] the coqrt considering the petition to use any of the rules

of civil procedure (unless inconsistent $ith these mles of habeas cotpus)

when in its discretion the court decides they are appropriate under the eir-

cumstances of the particular case. The court does not have to rigidly ap-

ply nrles which would be inconsistent or inequitable in the overall frame-

work of habeas corpus." As we have explained in the text above, use of

the ,llain enoy'' standard is 'tnconsistent or inequitable in the overall

frameworlC' of coilateral reyiew of federal criminal coitvictions under

$ 2255.

'c Frady claims that he had "cause" not to object at trial or on appeal be'

cause those proceedings occured before the decisions of the Coun of Ap-

peals disapproving the erToneous instnrctions. Any objection, he asserts,

therefore would have been futile.

In this rrigard, the Govemment points out that the flrst case to reject the

jury instmctions Frady now attacks rvas decided only tu'o years after

81 987

Citcd 42 CCII S' Ct' Bull' P'

UNITED STATES U. FRADY

rnconsiderin-.ti,#;,,Tillqi!'ffii:'iJl.::'.;I

roneolls jury instnt

rrrysg,*xg$li'- mxE-rffi

cases firrther etao

$3 U. S., at "'.

ffiftif" *1t1ofIit ttt'"in other situ-

El*

il::'r*ql'i?i1$,f'#1fl

'(:i""-*ili'ii""'rto,show

bef oreobtainrng'ttrffig:t**:'.t"f'S'I.,';X':11f,:r':m:ii:fi *x*.r";:ft :::.:::7

::l*:lt'mn fi!::11'd:'::*= ill **:"'a' u-

:**[ im,U;:*ii]l ::ffi:f ioilor"tion' which re-

';*l#i**fu in+t't'm$*[.m*

*:T,'#fr'f ,gn*xlT:l':1"'i't*il'.';i*',i[:{

*kjiTiHtt"''+hfi i**+xg*ilsai"*

I:i*df

".ffi

ir J '*t*i!iii't*;;*"'s m'#' ilr"::

'*,n""a.*,,r'::".1llil;5,i:i,:ff; l'e+tt?,Hp:m'i*:'

;:5;f#i1*,lti"'"H;;;;ii" t'o"' pl'l' ii *ii'r' we addressed a

Ir{Ir,*fi *:lh"n"u"*petitiono:::'llliillll?LT",.Ti*iii.

**l'"* *" i"qa st tsta' at 13' howev"t' ll'o="r; .*siitudonai stnctures

;,ff *.f $iil3:::';*'l',il:t"'T"1':

Br 988 citcd 42 ccH s. ct. Bull. p.

UNITED.STATES T' FRADY

ouires that the clegree of prejuclice resulting from instnrction

#.;"#;;;d i. the'totil context of the events at trial'

As we have often emphasized:

.[A] .'"-gi. in.t*ction to.a'{

j*y ;;y not U" judged in artificiai isolation' but must oe

1

"i.*.a in the .ont.it of the overall charge'" C"Pp .H

xluintrn.4l4 u. s. 141, 1.1il14? (19?3) (citations omitted).

#;;;;l ;.ltrdgment of conviction is commonlv the eul-

*i*iion 6r a titaluch includes restimony of witnesses: s-

ffi",,!..t counsel, receipt of.exhibits in evidence, and in-

3mrJi." of the iurry Uy^ttre judge' Thus not only is the

challenged instnrciion Uut one of In*y such instnrctions' but

iii"-proZ.rs of instnrction itself is but one of several compo-

,.rttrf the trial *ti.f, may result in the judgment of convic-

tion." Id., at L47."

i,v. no* rppty these established standards to Frady's case.

ry

Frady bases his claim that he was prejudiced on hi-s-asser-

tion ttrat the jr:ry was not given an adequate oppoftunity to

consider a mar,.t"ugirter vJrdict' eccordlnq toJraay+rc

'' At the lime Frady was tried, murder in the flrst degree was defined

(and stiil is) as a tiuing .oi*ittei .lurposeiy'' "of deliberate and premedi'

;"d ;J;;." D. c. c"a. s 2-240r (1b81)' ,Murder

in the second degree

was defined ." "

f.iffins (oii'tt tt'* a fist<legree murd-er) with "malice

aforerhought.,, S Z-Zi'Oi. Culpable killings without malice were defrned

to be manslaughter. See n. 7' sttpr.o'

The District of Cotumbia .t't"t' clefining murder in the flrst and second

degree were first p".."d

"i

the turn of the century' Act of M*' ?' 1901' 31

st":.. igzr, ch. 85i, $0 ?98: aoo, as a coclifrcation of the common-law defini-

,i"*, "ti.f,

they did noi-AtpUt"' See-O'Connsr v' tinited Sloies' 399 A'

?rtls|tDC 19?3); ao*iitii'i. inited' States'26 U' S' App' D' C' 382' 385

(1905). The definition of manslaughter was never codifred' but remairr a

matterofcommonlaw.seeLinit-ed'Stolesv.Pend,et,3og.L2d.l92(Dc

Cited 42 CCH S. Ct. Bull. p.

UNITED STATES i,. FRADY

Our

*ffi:111_ k ^tl _*!yig:" rhe. burd e;,f ,i;;;:?,;to Frady's

$".:9,r:*:::, infectins rri. .nti". iil ;ilh #; ffiXffit;

Bt 989

This Frady has fa,ed to do. at the outset, we emphasize

r973).

The significance of

.the,

various degrees of homicide uncler the law of theDistrict was sumrnarizea Uy *re Coirr.:ii.r,pp""rs in 1967:

"In homespun terminorogy, intentional murder is in the first degree rfcommirted in cold brood,. ani is muraeiin ii" ,."ona degree if commirtedon impulse or in the sudden.hear ,a;;:i;;:'. . . [AJ homicide conceived inpassion constitutes murder in tir" n""iJls"" onry if the jury is convincedbevond a reasonable aouut rhat ih;;;;;";"ppreciabre time after the de-sign was conceived urd. that in trus il; ti,ir" *""

"-n

ir[" ir,ougi,t,and a turnin' over in tt. rina-*J;;;;.* perristence of the initialimpulse of passion.

'' ' ' [A]n unlavrfur huing in the sudden heat of passion-whether pro.duced by rage' resentment. anger. ten'or or fear-is reduced from murderto manslaughter onJy if there ** ,a"q*i. provocation. such as might nat-urally induce a reasonabie ,,r io ril *.fi of the moment to loie self-control and commit the-act on impulse

"na

*iit out reflection. ,, Austii v.united Statbs, tn u. s. app- li.i. ;d t8s, 882 F. zd w, tB? (rs6r)(citations omitted).

The polic:r basis for the clistinction between first-degree murder andother homicjdes was

"ry1ry:a ii cii'i"ri ,.z,nitriitiir, i+ rii.'epp.D. c. m, ur, Lz, r. id erg, ziiiiiriii, " '

"statutes like orirs. which disting:*ish crelberate and premecritatecr murcierfrom orher murder, reflecr

"

;]i-.f ,h";;;iio m"airates an intent to killand then deliberately executes it is. more aangerous. more culpable or resscapable of reformarion than one who tciUs oi.suaaen impulse; or that thepnospecE of the death oenalty is mop r,..rv i. cleter men from deliberatethan ftom impursive ,Lu"t.- rrr" aeriue'#""t itt"" is gu,ty of first degreemurdeg the impulsive killer is not.J-------- "

So stated, Frad/s claim of actual prejuciice has validity

,

Br 990 citcd 42 ccH s. ct. Bu[. p.

UNiTED STATES T.. FRADY

that this would be a different case hacl Frady brought before

the District Court affirmative evidence indicating that he had

been convicted wrongly of a erime of which he was innocent.

But Frady, it must be remembered, did not assert at trial

that he and Richard Gordon beat Thomas Bennett to death

without malice. Instead, Frady claimed he had nothing

whatever to do with the crime. The evidence, however, was

overrrhelming, and Frady promptly abandoned that theory

on appeal. Frady I, L27 U. S. App. D. C., at 95, 348 F. 2d,

at 101. Since that time, Frady has never presented color-

able evidence, even from his own testimony, indicating such

justification, mitigation, or excuse that would reduce his

crime from murder to manslaughter.

Indeed, the evidence in the record compels the conclusion

that there was, as the clissenters from the deniai of a rehear-

ing en banc below put it, "malice aplenty." Frady III,204

U. S. App. D. C., at 245,636 F. 2d, at5l7. Frady and Gor-

don twice reconnoitered their victim's house on the afternoon

and evening of the murder. Just before the killing, they

were overheard in a conversation suggesting that they'\rere

assassins hired by George Bennett to do away with his

brother." Frady I, LzL U. S. App.D..C., at 97,348 F. 2d,

at 103 (Miller, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part).

They brought gloves to the scene of the murder which they

discarded during their flight from the police, and the murder

weapon bore no fingerprints. FinaUy, there was the un-

speakable bmtality of the killing itself.

Indeed, the evidence of malice was strong enough that the

10 judges closest to the case-the trial iudge and the nine

judges who 17 years ago decided Frady's appeal en banc-

were at that time unanimous in finding the record at least

sufficient to sustain a conviction for second-degree muriler-

a kilting with malice. Nine of the l0 judges went further,

finding the evidence sufEcient to sustain the jury's verdict

that Frady not only killed with malice, but with premeditated

and deliberate intent.

We conclude that the strong uncontradicted evidence of

Br 991

citcd 42 ccH S. Ct. Bull' p'

UNITED STATES I.. FRADY

malice in the record, Fraciy's utter feiigre-ig

mauce ln LIrtr rELUrrrl wvsr'Yt-

thai hej44ed_lrilhoui,;o[|j;*,"rd *U-1-e'oIoqbllrqtm,

malice, clisPoses of i:::,'::lil

Bm#i'T';{il'$iy;J}H'J'l*rmlxiL'.'.*

riage of justice in this case' .:-^|:^- ^r +ha irrnr ''^'S;Jd;t douut remain' our,ex-Lmlnation of the jury in-

stnrctions shows "" "Ut["ftiA

tiitttit'ood that the same jury

that forlrd Frady ffi;;ifi"t-degree murder would have

concluded, if only fi;-;;li;; instrirctions had been better

framed, that his ;;;

-was

only manslaught-er' T", j"v'

after all, did not ttiJy g"a fraay gurlty of second-degree

murcler, which ,tqoi"J odv matice'

- It iound Frady guilty

of first-de gr..J tllil;itlna pre meditat ed-murd er'

To see pr..i."ty'tlitit-ioUi'"a to conclude to make this

finding, it is neces;#;;:i';"t":,!n" instmctions the triai

judge gave the :'"y '" the meaning of premeditation and

deliberation:

"lP]remeditation is the formation.of the intent or pian to

kill, the r.",#"t ;i';;;!iti"-t ies1gn

to kill' It must

have been contitlered bi the defendants'

..Itisyo*ii.ii.ililt..''i"-"fromthefactsandcir.

cumstance. "'

tt'G case as you-nna ttrem sturounding the

killing wtretirel?nii4'31'a consideration amounting

to deliberatio;;;;;a.- .If .q, even though it be of ex-

ceedingly u,i.i"a'''iliioii' tr'"i 1s suffr cient'- because it is

the fact or a.riu![ffiffi;-]i;; tt'* ti" Iength of t'l:.it

continued tf,"i-it irnpo't'nt' Althou-g\ some app-recla-

ble period ot iit"-nltt ha'e elapilda*ing whic'h the

defendants dtiiil;tilit *at"r* this eiement to be es-

tablished, no'il*il'ri;t;;gth J ti*t is necessary for

deliberationt .Lt ffiols "* *o'*e the lapse of davs or

hours o, .u.'ll? il;;;;-

-ii- i" No' +0-?'-63 (Dc)' p'

806, rePrinted at APP' zE'

Bv contrast, to have found Frady suiltv of manslaughter

theirrry wouid h;#;;d ;'inaii't fr"tttintt of the kind of

81992 Citcd 42 CCH S. Ct. Bull. p.

UNITED STATES u. FRADY

excuse, justification. or mitigation that recluces a killing from

murder to manslaughter. As the trial court put it:

"The element [sic] the Government must prove in or-

der for you to find the defendants Sudty of manslaughter

are:

"One, that the defendants inflicted a wound or wounds

from which the deceased died, these being inflicted in

the District of Columbia.

"Two, that the defendants stmck the deceased in sud-

den passion, E!$rgg! e3iigr,that the defendants' sudden

passion was aroused by adequate provocation. When I

say sudden passion, I mean to include rage, resentment,

anger, terror and fear; so when I use the expression

'sudden passion.' [sic] I include all of these.

"Provaeation, [sic] in order to bring a homicide under

the offense of manslaqghter, must be adequate, must be

such as might naturally induce a reasonabli man in anger

of the moment to commit the deed. It must be such

provocation would [sic] have like effect upon the mind of

a reasonable or average man causing him to lose his self-

control.

"In addition to the great provocdtion, there must be

passion and hot blood caused by that provoeation. Mere

words, however, no matter how insulting, offensive or

abusive, are not adequate to induce [sic] a homicide al-

though committed in passion, provoked, as I have ex-

plained, from murder to manslaughter." Id., at p. 809,

reprinted at App. 30.

Plainly, a rational jury that believed Frady had formed ,,a

plan to kill . . . a positive design to kill" with "reflection and

consideration amounting to deliberation," could not also have

believed that he acted in "sudden passion . . . aroused by ad-

equate provocation. . . causing him to lose his self-control."

We conclude that, whatever it may wrongly have beiieved

malice to be, Frady's jury would not have found passion and

fl

/

/.

Citcd 42 CCH S. Ct. BulI. p.

UNITED STATES U. FRADY

provocation. especially since Frady presented no evidence

whatever of mitigating cireumstances, but instead defended

by disclaiming any involvement with the kiliing." Surely

there is no substantial likelihood the enoneous malice in-

stnrctions prejudiced Frady's chances with the jury.

v

In sum, Frady has fallen far short of meeting tris Uuraen oy'

showing that he has suffered the degree of actuai prejudice

I

necessary to overcome society's justified interests in the fi- |

nality of criminal judgments. Therefore, the judgment of I

the Court of Appeals is reversed, and the case is remanded

I

for further proceedings consistent with this opinion. J

o ordered.

THs CHrrF JusrIcE and JusucE MARSHALL took no part

in the consideration or decision of this case.

'e Nor, on the facts of this case, wouid a finding of a premeditated and

deliberate intent to kill be consistent as a matter of law with an absence of

malice. See n. 18, supflt.

We are not alone in flnding that an erroneous maiice instnrction is not

necessarily cause for reversal. Even on direct appeal rather than on col-

lateral attack, the highest eourt in the District of Columbia has refused to

reverse convictions obtained after the use of precisely the same instnrc-

tions of which Frady compiains here. For example, n Belton v. United

States, ln V. S. App. D. C. 201, 382 F. 2d 150 (1967), the fi:st deeision

expressly to disapprove the instnrction that the law infers malice from the

use ofa deadly weapon. the court afflrnred a first<legree murder conviction

with the obsen'ation that a "jury inferring premeditation and deliberation

could hardly have failed to int'er.maiice." Id., at 206,382 F. 2d. at 155.

Similarly, inHowardv. United Sfates, 128 U. S. App. D. 9. 336,389 F.2d

287 (196O, a seeonddegree murder conviction was ajfirmed on direct ap-

peal, although the same defective instmction had been given. In two

cases in which the defendants put malice in issue by raising self-defense

clirims at trial, however, the court, on direct apped, reversed murder con-

victions obtained through the use of the faulty instntctions. Grem v.

United Stdtes (Grem I), 132 U. S. App. D. C. 98, 405 F. 2d 1368 (1968):

United States v. Wharton,l39 U. S. App. D. C. 293, 433 F. 2d 451 (1970).

Br 993

81994 citcd 42 ccH s. ct. Bull. p.

SIPRENIE COTJRT OF TIIE I]MTED STA{rES

No. 80-1595

UNITED STATES, PETITIONER, U. JOSEPH C. FRADY

ON WRM OF CERTIOBARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEAIS FOR TIIE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

lApril S, 19821

Jugrcr SreveNs, concuring.

Although my view of the relevance of the cause for coun-

sel's failure to object to a jury instmction is significantiy dif-

ferent from the Court's, seeWairuttright v. Sykes, 433 U. S.

72, g4-l97 (SrrvrNs, J., concurring)i Rose v. Lundy,

-U. S.

-r -

(StnvrNs, J., dissentng);.Engle v' Isaac,

-

U. S.

-, -

n. 1 (StSvpNS, J., concuning in part

and dissenting in part), I have joined the Court's opinion in

this case because it properly focuses on the character of the

prejudice to determine whether eollateral relief is

appropriate.

cited 42 ccH s. ct. Bull. p.

SI]PREME COT]RT OF TIIE LII.IITED STAf,ES

No. 80-1595

UNITED STATES, PETITIONER, t. JOSEPH C. FRADY

ON WRTT OF CERTIORARI TO TIIE UNITED STATES COURT OT'

APPEAIS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBH CIRCIIIT

[Apri]5, 1982]

Jusflcg BuectotuN, concuring in the judgment.

Like JusucE BBENNaN, I believe that the plain emor mle

of Fed. Rule Crim. Proc. 52(b) has some applicability in a

5n55 proceeding. In my view, recognizing a federai court's

discretion to redress plain erzor on collateral review neither

nuilifies the cause and prejudice requirement articulated in

Wainutright v. Sykes,433 U. S. 72 (19?7), nor disserves the

policies underlying' that requirement.

Despite the Court's assertions that Ruie 52(b) was in-

tended for use only on direct appeal and that the Court of Ap

peals ignored "long-established contrary authority," ante, at

Ll, L2,I find nothing in the Rule's seemingly broad language ,

supporting the Court's restriction of its scope. In fact, the fif

plain error doctrine .is specifically made applicable to allflll

stages of atl criminal proceedings, which, as the dissentingffl

opinion points out, include the collaterai review procedures of l"

$ 2255. See post, at 2, 4-5, and nn. 5, 6. Even more strik-

1

ing, $ 2255 Rule 12 explicitly permits a federal court to "apply I

the Federal Rules of Criminai Procedure or the Federal I

Ruies of Civil Procedure, whichever it deems most appropri- |

ate, to motions filed under.these mles." 28 U. S. C. $rrfl

Rule 12.*

I Aithough $ 2255 Rule 12 does not 'tnandate bf its own force the use of

any panicular mle of civil or criminal procedure," ante, at 1L15, n. 15. it

does afford a federal court discretion in determining whether to appiy the

Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure or the Federal Rules of Civil Proce-

dure. The Coun's e.xtended discussion, in the same footnote. of the Advi-

Br 995

*a

/

Bl 996 citcd 42 ccH s. cL Bull. p.

UNITED STATES U' FRADY

The cause and prejudice standard of Waintwight v' Sykes'

$tpra' is premised on the notion that. c9pteE!.?ra+e=o1l

ttre interests of

p strative goais such

;;;;;i..ist;a to serve.

-See

433 U'S', at 88-90'. As

founa here, an explicit exception to the contemporaneous

objection nrle is aPPlicable. Gi

to a eon

ion has

;@emporaneous obj ectiol ttqy.tT:l:

ihe Court conledes, considerations of comity are not- at issue

here. See ante, at 13. The second objeetive of the cause

and prejudice requirement-lo enforce contemporaneous

oUi..iiori nrles and, in particutar, to ensure finality-is, in

il;;; ti*if"rfv irrelevant where, as, the CtY t-f

}-p-p^"*

and a prisoney's petition forcoilaterai review falls within that

oa"piior, I see no need for the prisoner to prov.e "cause" for

his failure to comply with a nrle that is inapplicable in his

- sase.

r-I" the federal courts, the plain elTor doctrine constitutes

, - I * .*;;;d; go Fed. Rule crim. proc. 30's requirement that

-t<- hrq"id;t. ,rt " timely objections to instn:ctions' If the

"edft of AppeJs prop."iy .[o".t.tired the errors identifled

uy

"..pondent

as'plain error, it correctly refused.to require

him to *"k; i1," iro.. and prejudice showing dtiscribed in

soryCommitteeNoteto$22S4Rulell.isbesidethepoint.The.Advisory

co,*itt."Notetoszs;nuePexpresslyobsenesthatRule12"dif.

i.i; torn $ 225a Rule tt in that the former "inclucles the Federai Rules of

criminal Procedure as rvell as the civii." And the note to Ruie 12 appar-

mrly refers to the note accompanf in_g $ 2254

^Rule

11 -tflor cliscussion" oniy

oitf," restrictions rn Fecl. R. Civ. P. gtlaxZl ' ' ' .'' Even if the note to'

S-Zil nrr" ll is reievant to our clecision in this case. I do not subscribe to

ih" Co*t,. conclusion that the plain enor cloctrine is " Snconsistent or in'

"qoiout"intheoverallfrarnervorK,'ofcoilateralrel"iervpursuanttoi r55. See ante, at 15. n. 15. quoting Aclvisory committee Noce ro i 21{

Rule 11.

81997

circd 42 ccH s. ct. Bull. p.

UNITED STATES U. FRADY

Waimtright v. SYkes, sxlPro" -hri; aipror.i, ioes'not, as the Cgutt charges'- "affor[d] fed-

eral prisoners a preferred status when they seek post-convic-,

tionielief.,, Ante, at L4. The court has long recogmzedf

;-# th; Wainunight v. Sykes standarcl need not be metl

whereaStatehasdeclinedtoenforceitsowncontemporane;1

."..U:..tion nrle. See, e. g', Uls-ter.Cwnty C*4v.' Allen'

442 TJ. S. 140, 14&154 (tbzgl; wainutrig_ht_r:-lay12' 433

U. S., "i

aZ; Francis v. Hend'erson,425 U' S' -a36' ilL l,iV

obid. simiiarly, the cause and prejudice standara sirc$!

/

not be a barrier to relief when the plain error exception.to,the

I

federalcontemporaneousobjectionrequirementisap:licabll[

aTilf;;;J contemporaneous objection m=lei uuy differ tom'

\,h;.;.f ,h. St@Y of the Wainunight v'

ffi;**A;ArE refore may vary according to the contours

/;i fi; p"ni.ot"" jurisdiction'i contemporaneous obj ection re-

(oritl"i*r.

_-gri

that variance does not improperly distin-.;;h

il;..n f.d.t t and state prisoners, just as respecting

irr, aif.".nces between the contlmporaneous objection nries

of two states creates no impermissible distinction. In fact,

it is the Court's approach-iefusing to give effect to the plain

Loo, exception io tt. federai contemporaneous objection

nrle, whiie recognizing exceptions to the analogous state

nrles-thatgives-someprisonersa..preferedstatus.,'

Similarty,-rnyapproachdoesnotaffordprisoners"asecond

appeal," anfte, al ii, ttut sacrificing.the interest in finality of

.irr't i.iiont. As the dissenting opinion observes' acknowl-

.agiil it . appticability of Rule 52(b) in $ 2255 proceedings

does not merge direci appeal ancl collateral review' See

prri .i,3, n. zisee atso Uiitectslafes v' Addonizio' MZ U' S'

izg,' tgO (i9?9); Hend'erson v. Kibbe, 431 U' S' 145' 16.l

(1977)..BecauselagreewiththeCourt,however,thatrespondent

has not clemonstrated that the erroneous jury instructions of

*ti.n he complains "so infected the entire trial that the re-

.uftinJ.onviciion violates due process," Cttpp v' I'laughtm'

81998

Citcd 42 CCII.S. Ct. BulL p.

UNITED S?ATES u. FBADy

474 U. S. l4l, l4Z.0gZB), I conclude thar the Court of Ap.peals ered in holding th;i;;;;t was enritted to reliefunder Bute E2(b)' i..o"ainsril'i-;;;.* in the reversar oftne judgurent of tt. C.,rrtliTip."fl.

Br 999Cited 42 CCH S. Ct. Bull. P.

SI]PRENIE COURT OF fiIE TINITED STTIES

No. 80-1595

UNITED STATES, PETITIONER U. JOSEPH C. FRADY

oNWRIToFoERTIoRARIToTHEUNITEDSTATEScoURToF

APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

[April5, 19821

Jusrrcr BntrNNRN, dissenting.

I have frequently dissented from this Court's progressive

emascuiation of collateral review of criminal convictions.

E. g., En4te v. Isaac,

-

U. S. :,- (1982); Sumnsr

v. ilIata, i+g U. S. 539,552 (1981); Wairutrightv. Sykes,433

U. S. 72, gg (L911); Stone v. Powell, 428 U: S' 465, 502

(19?6); see aiso Dauis v. United Stafes, 411 U' S' 233, 245

itgzgl 1M^RSHALL, J., dissenting). Today the Courttakes a

further step down this unfortunate path by_ declaring the

plain error st*drrd of the Federal Ruies of criminai Proce'

iure inapplicable to petitions for relief under 28 U' S' C'

5?255. in so doing, tle Co,rt does not pause to consider the

nature of the plain error Rule. Nor does the Court consider

lhe riminat character of a proceeding under $ 2255 as distin-

guished from the ciuil chancter of a proceeding under 28

il. S. C. g11il. Because the Court's decision is obviously

inconsistent with both, I dissent.

I

A

The Court cleclares that the plain eror Ruie, Fed' Rule

Crim. Proc. 52(b), was intencled for use oniy on direct appeal

and is ,,out of place" when the prisoner is collaterally attack-

ing his conviciion. Ante, at 11. But the power to notice

p6in error at any stage of a criminal proceeding is funda-

82000

cited 42 CCH s. ct. Bull. p.

UNITED STATES u. FRA.DY

Eental to the courts'obtigation to correct substantiaj miscar-riages of justiee. Th"t ;bil;;tiJn qualifies rvhat rhe courtcharacterizes as our entitremEnt io pr..u*e that the defend_ant has been fairly d frh"$'.oi"i.r"a. Ante, at tZ.The Cot't coreetly p.i"i;;;; ante a*0, n. tB, that Rule52(b), was merely

".1r1"t.ril;existing law. The role ofthe ptain error gg1ry t ".-;il; been to empower courrs,espeeiauy in eriminar cases, to correct errors ihat seriouslyaffeet the ,fairness, integrity, o" puUfi. ;6;r;ri;; ofludicialptoceedings." t|nited, Slatii u. itkrrr-*,Zg? U.S, 152, 160

S_36): significantty,.ar,rough;;. of the Rules of criminar^ttocedure ap,eT.under h"di;;:uch as ,,preliminarv pro-eeedingB, "'Trial, " _or,,Appeaf fr ,L ;zrul i. .* .iii.t6.A rrerat Frovisions":f tl"

"*:G, .ooii.;;i;,;;u-;;: of au Icriminal proceedings in federai ;;il.. See Fed. Rule Crim. Ihoc. r.

E' vvq

-__{

The Rule has been.reried upon to-correct error:s that mayhave seriourly pr-.jyi..a , po'Jilrgr.9."ril;;d#,

see,e. s., Unitea st"ti::. *tan i,-iii 11 3a tztt, tzt*r,216 (CAIrwr), @;;,, rrtg"rmin;' il-i#eity orthe judicial proceeding,. see, ,jr., iW,449 F. 2d,92,9L?5 tiez rsiil]'' fr. p,"r' error Rute miti-gates the harsh impact of the aiversarial system, underwhich the defend"ntl. g.n."Jiy ["'"ra by the conduct of his

tary effect on the prosecutior'.rondu.t of the triar. If the

'Ru.le 52(b) provides:

"Plain enors or defeets affecting sustantial rigits may be noticed a.rthough

Hfl.H,T,."ot

brought to ri,"'ittlnt];;;;i" court.,, Fed. Rule brim.

Although the Rrrle applies to "prain errors or crefecrs affecting sub.tan-7tid rights," one commentltgy

1ai .rgg.ri.a inrt the disjunctive form of/the Rule is only a me:rns of aistlngr;siir;;;,

sio n or e,,i aen.i *i .i.r"" J ;"}: ;i;il;: fi:l,,ifr lI;. i r,; .,i; :ilf,

"

j

, i,s.,#i"iiil6;::i

citcd 42 CCH s. cL BulI. p. 82001

UNI?ED STATES r,. FRA.Dy

:1',.jXgJt[':H: t?l T:h.: t o guard

.

a gainst th e possi birity

e.xperience

"

rJ.:lli:tttifl #ilHliry- H[intervene ro proteet rh. J;iil;ir"o, the mistakes of coun-sel." 88 Moore,s Federal pr.ii..'q; Z.OZ Lzl (1gg1).The Rure does not ,ra..mire ooi int.".st in the finality ofcriminai convictions. Rule ;ifUi p..r"its, rather than di-rects, the courts to_ notice pf"in .[oI; the power to recognizeplain error is one qt.1 9ir.lil;;';; admonished to exercisecautiously, see United,srares v.'b;;,515 F. 2d g92, g96 (CA51975), and resort ,-o-grly in ;..*.1pilnal

cireumstances,i,Ar-kinson, ,*rpr,.. at 160, " v.t, ii"irntiri. power chat the courtholds congress intendecr-io ;;;;;;;*r courts reviewing ac-

Iiil:ltfl::?H*?i.*;::iJT'riifr *11y,:i:l:

H::

governing

$ 225i ;.;;;iL a.r" thit the bou,.r

I The Court,s assumption that Rule i2(b) is inapplicable toI proceedings under.s

?bm ir-6iil;;! gi;;^-;.H;;;;;;*,.

\ ru% €1 g. s. r+s, rs+ riiia'ir,ilh suggeilIhat theE#ffi !:rT, TiT; ;i, #i, #U,h#t,: :not, that the plain error cloctrin"-fr". no role in iUU..lio*,I could not accept trr" *r" cru-.t[ analysis because it fai]sto consider the expricit .ors.*ioirr ai.rin.tion between

,The Court rrrr..::.,,.1.11.,T1:Mng ferteral-couns to recognize plain:#JJH:[};*.":"Y rvoukr obscui.',i.,iin**;;, -;;;;' ifi","""r

$ 2355 and direct apo"r1'1'^'j:,1':

But the signint'nt Jrr.".;;:'#;;"",

rcsziJl.tj.*."'t:tj',ff i'i:::Hf :iT:Hi,i,":,,:H..,nl,11*l

;[:1,:il5,T:::ffi^1r_r:J rJlJi..s,,iJb'r" u,,r." $?o5r unjess it is a

actey',rhariiro.ii"i',i1,:,,j"iiijjil,"rrll.fi

f :;r;1..f,T..r;i::,i,L,

if:;: ;d.ff,J.,e 1;l1f;jft:l=,1'1iffi,

-

s""

"r.o

.iiij v Z.nited

82002 Cited 42 CCII S. Ct. Bull. P.

UNiTED STATES U. FRADY

g?9.*1,' a civil collateral review procedure for state prisonll

ers, and |?PJr:o,' a timina,l collateral review procedure foll

federal prisoners.

In enacting 28 U. S. C. $ in54 and,2255, Congress could

tn

"s.

This was

Rep.

reaf-

,

"State custody; remedies in State courts

"(a) The Supreme Court, a Justice thereoi a cireuit judge' or a district

court shall entertain an application for a lvTit of h in behalf of a

peFon in custody pursuant to the judgment of a State court only on the

gfound that he is in custody in violation of the Constitution or laws or

treaties of the United States."

'fitle 28 U. S. C. $2255 provides in pertinent part:

"Federal Custody; remedies on motion attacking sentence:

,.A prisoner in custody under sentence of a court established by Act of

Congress claiming the right to be released upon the ground that the sen-

tenci r"as imposed in violation of the Constitution or Iaws of the United

States, or that the court was without jurisdiction to impose such sentence,

or thet the sentence was in e.\cess of the maximum authorized by law, or is

otherwise subject to collateral attack may move the court which imposed

the sentence to. vacate. set aside or correct the sentence.

-

'A motion fo

,.An application for a writ of habeas col?us in behalf of a prisoner who is

authorizld to apply for reiief by motion pursuant to this section, shdl not

be entertained ifit appears rhat the applicant has failed to apply for reliei

by motion, to the court which sentenced him, or that such court has denied

him reliei unless it also appears that the remedy by motion is inaciequate

or ineffective to test the legality of his detention."

i Section 2255 was intended to be in the nature of, but much broader

The habeas urit remains available to fed-k to the cotrn mat sentg l ne naoea:t wnl relllallls .lt i:ulaurE LU rw-

- erai prisoners where the motion provided under $ 2255 is for some reason

inaclequate. S. Rep. No. 1526, 80th Cong., 2d Sess., 2 (1948). See also

H.R. hep. No. 308. 80th Cong. lst Sess., A180 (f947). See generaily

not have been more explicit: Seqlion

rate civil action, but a $ 225p-lqqqg!

Ariminai case il which petitioner is

o tS20, €Fth Cong., 2d Sess., 2 (1948).i

than.theaqgjentrwitofcoramnob t'nlik.

-{

/.-

/

B2003Cited 42 CCH S. CL Bull. P.

UNITED STATES U. FBADY

firmed in the 28 U. S. C. $ 2254 Rutes and the 28 U. S. C'

9?2j5:o Ruies, approved by Congress in 1976. 90 Stat' 1334'

The Advisory Committee's Notes for the E ZSe nUes emptu'

S1zE

Advi-

11, L2,

cifically prescribed by these nrles, the district court [consid-

ering a motion under g 22551 may proceed in any lawfui man-

United Stotes v. Hayman, ?/iZV. S. m5 (1952).

'The Advisory Note to Ruie I states in pertinent part:

.,Whereas sections 2,4L-?2il (dealing with federal habeas for those in

state custody) speak ofthe district court judge 'issuing the writ' as the op

erative re.iay, section 2255 provides that, if the judge finds the movant's

assenions to be meritorious, he'shall discharge the prisoner or resentence

him or gant a new trial or corTect the sentence as may apPear appropri-

ate.' lirir ir possible because a motion under $ 2255 is a further step in the

movant,s criminal case and not a Sepamte civil action, as appeanl from the

legislative history of section 2 of s. 20, 80th congress, the provisions of

,rf,i.h '*""e incorporated by the same Congress in title 28 U' S' C' as

$2255." 28 U. S. C., P.280.

The Note to Rule 3 states that the fiiing fee required for actions under

$ 2254 actions is not requted for motions under $ 22$: "[A]s in other mo-

tions filed h a criminal action, there is no requirement of a filing fee." a

U. S. C., p.283.

Rule 1l was amended in 19?9 to provide that the time for appeal of $ 2955

morions is governed by Ruie {(a). the civil provison of the Federal Rules of

Appellate foocedure, rather than nrie {(b), the criminai provision. But

tire Note to the Rule states: "Even though section 255 proceeclings are a

fui,ther step in the criminal ease, [this provision] corectly states culTent

Iaw." 28 U. S. C., p. 1207 (Supp. III).

The Note to Rule 12 states:

'This nrte differs from mle 11 of the $ 2254 mles in that it includes the Fed-

eral Rules of Criminal Procedure as well as the civii. This is because of

the nature of a S 255 proceecling as a continuing part of the criminal pro-

ceeding (see advisory committee note to rule 1) as rvell as a remedy analo'

gous t; habeas corpus by state prisoners." 28 U. S. C'. p' 287'

82004 Citcd 42 CCH S. Ct. Bull. p.

UNITED STATES U. FRADY

ner not inconsistent with these ntles, or any applicable

statute, and may appty the Fedqal Rules of Crimitnl Proce'

dru,re or tire Federai Rules of Civil Procedure, whichever it

deems more appropriate to motions filed under these rules."

2g u. s. c. $ D-r; hute 12 (emphasis added). This is in con-

trast to the parallel Rule governing moli9ns under. $94*

which providls: ,ulhe Federal Rules of, Ciyil Procedure, ttrl

the extent they are not inconsistent with [the Rules Govern- /

ing Section 22Ba Casesl, may be applied, when appropriaterJ

. | ." 28 TJ. S. C. $ 2254 Ruie 11 (emphasis added). Thfl

court today blurs the distinction between $ 2255 and $ 22il,

ignores Congress' insistence that a $ 2255 motion is a continu-

a"tion of the criminal trial, and makes no mention of Congress'

express authorization to apply the Federal Ruies of criminat

Procedrrre.

The court suggests t}at to apply the piain elror Rule in

$ 2255 proceedings and not in $ 22# habeas actions would

grant flaerat prisoners a 'lrefelryed" stafiis ' Ante, at 14'

to the contrarlr, to bar federal judges from reeognizing plain

erToni on collateral review is to bind the federal prisoners

')

o

2d 506, 509 (Fla.

2d 1011, 1012 (1980);Wrightv. State,33 Md- App. 68, 70, 363

A. 2d lifzo, szz (19?6); Riggs v. State,50 Or. App. 109, I14,

6P9, P. 2d 327,329 (1981); indeed, by waiving a procedural

bar, state courts can permit the petitioner collaterai review

in federal court as weli. lee l[ullaneA v. Wilbu,r,421 U' S'

684, 688, n. 7 (19?5). But the federal prisonerJs only source

of respite from this court's "airtight system of procedural

forfeitures," Wainutright v. Sykes, 433 U. S., at 101 (BneN-

NAI.I, J. ciissenting), lies with the cliscretionary exereise of

the federal courts' power. The Court's nrling does not es-

tablish parity betwien federal and state prisoners; rather it

more tishtly thanlheir state counterparts to this Court's pro-

ceduraliarriersJhtate court judges may have power to rqc-

osnize olain error iricollateral reile@'

cited42 ccH s. ct. Buu. p.

UNITED STATES U. FRADY

unduly restricts the power of the federai courts to remedy

substantial injustice. i

As the Court notes, ante, at 13, the concems of comity

which underlie many of the opinions establishing obstacles to

92254 review of state confinement, 0. 9., Sumner v. Mata,

449U. S., at 5-o0;Stonev. Powell,428U. S., at491, n.31;

Francis v. Hmderson, 425 U. S. 536, 5,11 (19?6), are absent

here. If it is tl:ue, as the Court has repeatedly asserted, that

the tensions inherent in federal court review of state court

convictions require that substantive rights f ield at times to

procedural ntles, no similar tension erists in a $ 2255 proceed-

ing. Under i225:o, the prisoner is directed back to the same

court that fint convicted him. The plain er?or doctrin{

merely allows federal courts the discretion common to mos{

courts to waive procedural defauits where justice requires.)

I might add that this is not the first instance in which the

Court has obscured the distinction between 92254 and $ 2255.

ln Francis v. Henderson, s'u.pra, and then n Wairutright v.

lsykes, su:W, the Court ignored the distinction between

I S ZSe and $ D-il in order to apply a Federal Rule of Criminal

(Frocednre to the purely chlil 92254 proceeeding. Now,

ironically, the Court again obscures the distinction this time

to aaoid application of a Criminal Procedure Rule to a rimi'

nal i25:o proceeding. with each obfuscation of the distinc-

tion between i?2.54 and $ 2255, the Court has erected ; ne's

"procedural hurdle," see Engle v. .Issac.

-

U. S.

-,

-

(1982) (SmvrNS, J., concurring in parC and dissenting

in part), for prisoners seeking collateral review of their con-

victions. Indeed, the "cause and prejudice" standard, which

the Court today decides preempts the plain error Ruie, and

which I continue to view as antithetical to this Court's duty to

ensure that "'federal constitutional rights of personal liberty

shall not be denied without the fullest opportunity for ple-

nary federal judicial review,"" has its origin in the Federai

82005

B2006

UNITED STATES u. FRADY

Rules of Criminai Procedure that the Court now finds inap-

plicable. As the cause and prejudice standard has taken on

its talismanic role in the law of habeas coryus oniy through

the Court's past application of the principles of the Federal

Rules of Criminal Procedure in both 52284 and $ 2285 actions,

perhaps a brief review of this history is in order.

The "c_ause and prejudice" standard originated in Dauis y.c:dtrasffi frgz3). lnDTais,the Coun ap-pli Rules of Criminal Proce-

dure'to hoid that a federal prisoner seeking collateral re-

view under i2255 had waived his objection to the composition

of the grand jury. Relying on the exception for ,,cause

shown" in Rule 12(bX2), and Shotwell Manufacturing Co. v.

United States,37l U. S. 341 (1963) (a case of direct appeai

from a federai conviction in which the Court constmed-the

cause exception to 12(b)(2) as encompassing an inquiry into

prejudice) the Court divined a nrle for $ 22Ei challenges to

the composition of the grand jury: such claims were cogni-

zable oniy if the prisoner showed both ',cause,' and ,.preju-

dice." Dauis v. United States, supro,, at 24{245

0n the foundation of Dauis, the Court has buiit an incred-

ible "house of cards whose foundation has escaped any sys-

tematie inspection." Wainunight v. Sykes, sltpra, at 100,

n. 1 (BnnNNAN, J., dissenting). Notwithstanding the lack

of any evidence of congressional purpose to apply the Fecleral

Rules of Criminal Procedure except in $ 22Si proceedings,'

cited 42 ccH s. ct. Bu[. p.

senting), quoting Fay v. iYoio. 3?2 U. S. ggf, €4 (196A).

'Rule l2(bX2), amended in l9?4, provided in peninent parr ar the time

Darns was decided that:

"Defenses and objections based on defects in the institution of the pros-

ecution or in the indictment or information other than that it fails to iho*

jurisdiction in the court or to charge an offense ma1. be raised oniy by mo-

tion before trid. . . . Failure to present any such clefense or objection as

herein provided constitutes a rvaiver thereoi but the court for eause showa

may grant retef ftom rhe waiver." Fed. Rule crim. Proc. 12(b)(2) (1g?0).

'fie Court stated in Dads, rrithout citarion, that "The Federal Rules

Cited 42 CCH S. Ct. Bull. p.

UNITED STATES u. FRADY

82007

{qre crimhat defendant Finaly, coming n U .i".f.,-t[.

court today relies on this "cause and preJ'uiice,' standard to

preempt the plain emor standard of Rule of 5Z(b).

Francis and,wainutrig,ftt_held applicable to a ciuil proceed-

Tg an inapplicable Rule of criminal procedure in order to de.

feat substantial claims of state prisoners. Today the Court

excludes the applicablity in a criminal proceeding or a Ruie of

criminal Procedure plainly intended by congresi to be avail-

ableto fgdgral prisoners. Any consistency iir these decisions

hes in their announcement, that even in the teeth of clear

congressional direction to the contrary, this court wiit strain

to subordinate a prisoney's interest in substantial justice to a