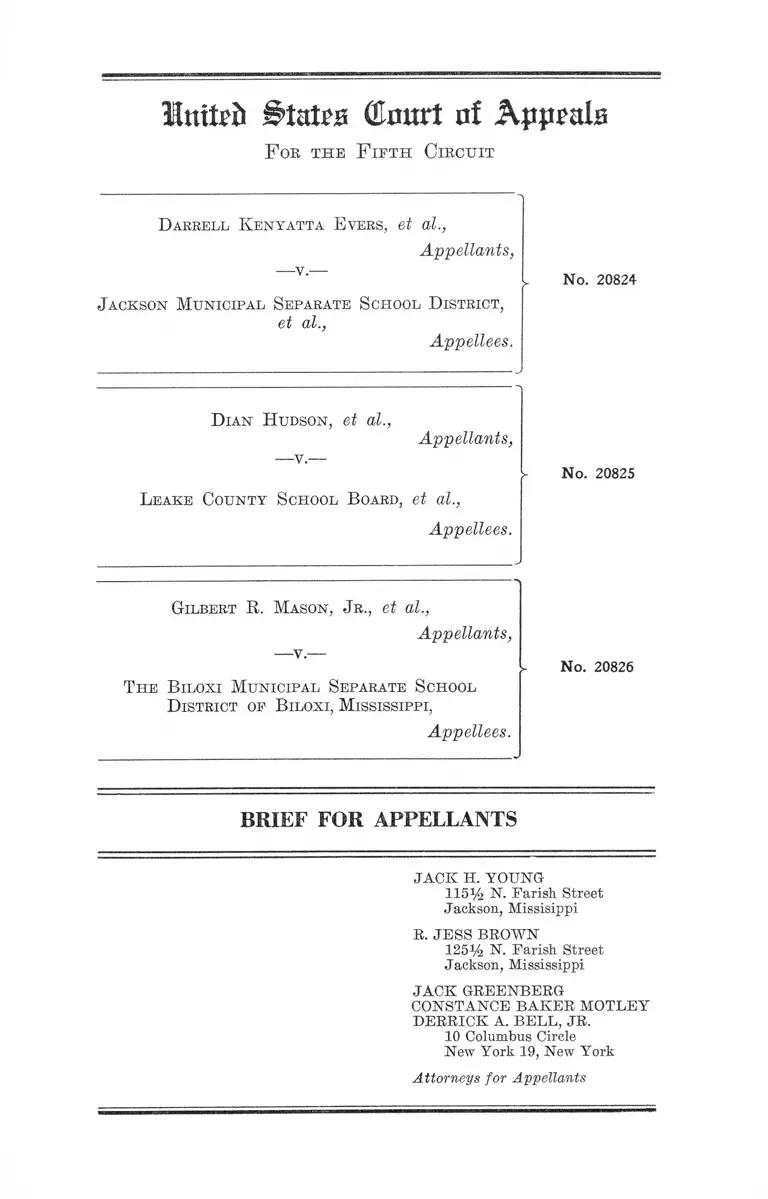

Evers v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Distr. Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Evers v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Distr. Brief for Appellants, 1963. a9e8155a-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4c5a0798-e1ec-441a-9634-bbc30152aa80/evers-v-jackson-municipal-separate-school-distr-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

Hutted States OJuurt uf Appeals

F oe t h e F if t h C ir c u it

D arrell K enyatta E vees, et al.,

Appellants,

-v -

J ackson M unicipal Separate S chool D istrict,

et al,,

Appellees.

D ian H udson, et al.,

Appellants,

L eake County School B oard, et al.,

Appellees.

Gilbert R. M ason, J r ., et al.,

Appellants,

T he B iloxi Municipal Separate School

D istrict op B iloxi, M ississippi,

Appellees.

No. 20824

No. 20825

No. 20826

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

JACK H. YOUNG

llSi/o N. Earish Street

Jackson, Missisippi

R. JESS BROWN

1251/; N. Parish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

JACK GREENBERG

CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY

DERRICK A. BELL, JR.

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

Statement of the C ase...... ................................................. 1

General Summary ..... ........................................................ 1

I. Evers, et al. v. Jackson Municipal Separate

School District ........................................................ 3

II. Hudson, et al. v. Leake County School Board .... 5

III. Mason, et al. v. Biloxi Municipal Separate

School District ......................... 6

Specifications of Error ...................................................... 8

Argument

I. The Appellees Maintain Racially Segregated

Schools in Conformance With Mississippi Laws 8

II. Appellants Are Entitled to the Relief Sought

Without Exhausting Remedies in Mississippi’s

Pupil Assignment Act .......................................... 12

III. Appellants Are Entitled to Orders Reversing

the Dismissal of These Cases and Other Ap

propriate Relief in Accordance With the Deci

sions of This Court ................................................ 14

Conclusion ............................................................................ 18

T able of Ca s e s :

Aaron v. McKinley, 173 F. Supp. 944 (E. D. Ark.

1959), aff’d sub nom. Faubus v. Aaron, 361 IT. S.

197

PAGE

9

ii

Allen v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 198 F. Supp. 497 (E. D. Va. 1961) ........ ...... 9

Armstrong v. Board of Education of Birmingham,

------ F. 2 d -------- (5th Cir. Jul. 12, 1963) ........... 12,14,17

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) ....8,11,

14,16

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955) .... 17

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 187 F. Supp. 42

(E. D. La. 1960), aff’d 365 TJ. S. 569; 308 F. 2d 491-

501 (5th Cir. 1962) ..........................................................9; 13

Davis v. School Commissioners of Mobile County,------

F. 2 d ------ (5th Cir. Jul. 9, 1963) .............................. 14,17

Fowler v. Curtis Pub. Co., 78 F. Supp. 303, aff’d 182

F. 2d 377 (D. C. Cir. 1950) .......................................... 16

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of Dade County,

246 F. 2d 913 (5th Cir. 1957); 272 F. 2d 763 (5th

Cir. 1959) ........................................................................

Goss v. Board of Education of City of Knoxville, 373

U. S. 683 (1963) ............................................................

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board, 197 F. Supp.

PAGE

649 (E. D. La. 1961), aff’d 368 H. S. 515................... 9

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction of Palm Beach,

Florida, 258 F. 2d 730, 732 (5th Cir. 1958) ............... 13

Holmes v. Danner, 5 Eace Eel. Law Eep. 1092 (1961) 9

James v. Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331 (E. D. Va. 1959),

appeal dismissed, 359 U. S. 1006 .................

13

17

9

I l l

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 668, 671

(1963) ..................................................... .......................... 12

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 277 F. 2d

370, 372 (5th Cir. 1960) ........................... .................. 13,15

Meredith v. Fair, 199 F. Supp. 754 (S. I). Miss. 1961),

aff’d 298 F. 2d 696, 701; 305 F. 2d 343, 344-45 (5th

Cir. 1962) .... ........... ............ .............. ...................... ....... 11

Monroe v. Pape, 365 TJ. S. 167, 183 .............................. 12

Nelson v. Grooms, 307 F. 2d 76 (5th Cir. 1962) ........... 2

Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 242 F. 2d 156,

166 (5th Cir. 1957), cert. den. 354 U. S. 948 ...........12,17

Potts v. Flax, 313 F. 2d 284, 290 (5th Cir. 1963) ____ 13

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham Board of Education,

162 F. Supp. 372 (N. D. Ala. 1958), aff’d 358 U. S.

101 (1958) ............................... ..................... ......... ...... .. 13

Smoot v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance

Co., 299 F. 2d 525 (5th Cir. 1962) ............. ....... ......... 16

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Educa

tion, 318 F. 2d 425 (5th Cir. 1963) .......................... 17

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 (May 27,

1963) ................................................................... ............. 17

PAGE

O t h e r A u t h o r it ie s :

28 United States Code, §1983 ....................................... . 12

Mississippi Constitution

Art. 8, Sections 201, 205, 207, 213-B ....................... 9

1Y

Miss. Code (1942) Annot.

§3841.3 ..... 10

§4065.3 ........................... 10

§6220.5 ..................................... 10

§6232-21 to 6232-43 ......................... .................. ......... 9

§6328-01 to 6328-117 ............................... ........... ...... 9

§6328-03 .............. 9

§6334-01 to 6334-07 ................... ..........................2, 4, 7,14

§6334-11 ............ 10

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 12(b) ............. 15

6 Race Rel. Law Reps. 314 (1961-62) ................................. 9

2 Moore’s Federal Practice 2255-2257 ..................... 16

PAGE

Mnxteb Btutva GImtrt rtf KppmilB

F ob th e F if t h C iechit

D arrell K enyatta E vers, et al.,

Appellants,

■—v.—

J ackson M unicipal Separate School D istrict,

et al.,

Appellees.

D ian H udson, et al.,

Appellants,

L eake County School B oard, et al.,

Appellees.

Gilbert R. Mason, Jr., et al.,

■—v.—

Appellants,

T pie B iloxi M unicipal Separate S chool

D istrict of B iloxi, M ississippi,

Appellees.

No. 20824

No. 20825

No. 20826

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement o f the Case

General Summary

Nine years after the United States Supreme Court de

clared segregated schools unconstitutional, Negro parents

in three Mississippi communities, Jackson, Leake County

2

and Biloxi, having petitioned their respective Boards of

Education without success to comply with the law of the

land and initiate desegregation of the public schools, tiled

these actions in the United States District Court, Southern

District of Mississippi, seeking injunctive relief to compel

the termination of policies of racial segregation main

tained by the Boards in clear violation of the constitu

tional rights of appellants and the class they represent.

Motions for preliminary injunction seeking relief in the

1963-64 school year were filed with the complaints.

In phrasing now familiar to virtually every district

court in this Circuit, and relying on decisions so numerous

that in the words of one member of this Court they “ are

an affectation to cite” ,1 appellants prayed for an end to

the biracial public school system operated by the Boards

under color of state law and pursuant to a policy, custom

and practice sanctioned by state law. In this regard, the

complaints referred to provisions in the Constitution and

Statutes of the State of Mississippi expressly requiring the

segregation or aiding in the maintenance of segregation

in the public schools.

In response, the three appellee Boards filed almost

identical motions to dismiss. The Boards did not deny

that the public schools under their jurisdictions are oper

ated on a racially segregated basis, but each maintained

that the failure of any appellant to apply to a particular

school or seek individual reassignment in accordance with

a state pupil assignment law adopted in 1954, Miss. Code

Annot., §§6334-01 to 6334-07, required dismissal of the

suits.

The court below reviewed the pleadings and facts con

tained in affidavits filed with the City of Jackson and

1 Judge Brown concurring in Nelson v. Grooms, 307 F. 2d 76

(5th Cir. 1962).

3

Leake County cases, and dismissed them because appel

lants had failed to exhaust administrative remedies pro

vided by state law. Upon ascertaining that the City of

Biloxi case was similar to the other two, the court below

dismissed it without opinion.

Still seeking to initiate desegregation of their school

systems at the start of the 1963-64 school year, appellants

on July 16, 1962 appealed and filed motions for injunctions

pending appeal or in the alternative motions to advance

the appeals and oral arguments in these cases. These

motions were denied by this Court on July 22, 1963, and

a subsequent motion to consolidate the cases for appeal

was also denied although permission to file single briefs

was granted which right is being exercised by appellants

here.

I.

In Evers, et al. v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, suit was filed March 4, 1963 on behalf of 10 Negro

children, and all other Negro children similarly situated in

Jackson, Mississippi. This action followed the appellee

Board’s failure to respond to a petition calling for desegre

gation of the schools mailed to it in August 1962 by the

appellants and other Negro citizens of Jackson, Mississippi

(R. 25).

The complaint alleged that the Jackson Public School

system is wholly segregated pursuant to state law and

Board policy, custom and practice (R. 4-7). Schools are

limited to attendance by white students only or Negro

students only (R. 5), and teachers, principals and other

professional personnel are assigned to such schools on

the basis of race (R. 6). Budgets, school construction

plans, and other aspects of school administration are

adopted and executed in accordance with the operation of

a compulsory biracial system of schools (R. 6). Appel

4

lants did not apply for individual transfers nor did they

seek to exhaust the administrative remedies provided by

the Mississippi pupil assignment act, alleging that such

exhaustion, in view of the state policy and the policy of

the appellees, would have been futile and inadequate to

provide the relief which they seek (R. 8).

Appellees’ motion to dismiss (R. 15) includes allegations

that the complaint fails to state a claim upon which relief

can be granted, that plaintiffs have not been denied any

personal rights, lack standing to seek relief for themselves

and for others, that the court lacks jurisdiction, and that

appellants failed to exhaust administrative remedies under

Mississippi Pupil Assignment Laws §§6334-01 to 6334-07.

In support of the motion, appellees filed a lengthy affi

davit signed by Superintendent of Schools, Kirby P.

Walker (R. 17-33). The affidavit states that in August

1954, the appellee Board abolished all attendance areas

and since that time has assigned all students individually

after receiving applications prepared by the students

(R. 17-18), that none of the appellants have ever sought

reassignment to a school other than those to which they

were assigned (R. 19-20), and that no child would know

the school to which he would be assigned for the 1963-64

school year until after application has been made for

enrollment and temporary assignment is made by the

superintendent, after which, applications for change in

such temporary assignments would be received (R. 21).

The affidavit and exhibits attached in support (R. 24) do

not indicate that the superintendent could make assign

ments on other than a biracial basis.

The appellee Board acknowledged receipt of appellants’

desegregation petition in the superintendent’s affidavit

without indicating whether any consideration was given to

it (R. 21). Six of the appellants, according to the affidavit,

have submitted applications for enrollment and assign

ment for each scholastic year (R. 22), but the application

forms provide no opportunity for the student to select

the school where he is to be assigned (R. 27-32). Each

applicant is required by state law to sign a certificate in

dicating non-affiliation in secret societies (R. 33), but such

signature has no apparent effect on school assignment.

Following a hearing on appellees’ motion to dismiss in

April 1963 (R. 34), the Court took the ease under advise

ment until June 24, 1963, at which time all counsel were

advised in a letter opinion of the court below’s decision to

dismiss the complaint because none of the appellants had

exhausted the remedies provided by the State Pupil

Assignment Act (R. 35-37). An order to this effect was

signed on June 29, 1963 (R. 40), from which order appel

lants bring this appeal (R. 41).

II.

Hudson, et al. v. Leake County School Board, was

brought on behalf of 28 Negro children, and other Negroes

similarly situated. The complaint, filed March 7, 1963,

set forth the by now familiar details of a biracial school

system manifested by the complete racial segregation of

all students, teachers, budgets and other appropriated

funds (R. 6). In February and again in August 1962,

appellants and other Negro parents petitioned the Board

to desegregate the schools, but received no official response

from the Board (R. 6-7).

The appellees’ policy of maintaining segregated schools

is in accord with state law (R. 7-8) which so expressly

requires such policy as to render futile and useless the

exhaustion of provisions of the State Pupil Assignment

Act (R. 9). Appellants alleged these policies violate rights

guaranteed them by the Fourteenth Amendment, and,

6

seeking immediate relief, they filed a motion for a pre

liminary injunction (R. 11).

A motion to dismiss filed by appellees (R. 15) contained

inter alia an allegation that the complaint fails to state

a claim upon which relief can be granted, and also re

ported appellants’ failure to exhaust administrative rem

edies under Mississippi’s pupil assignment act. An

affidavit by School Superintendent, I). C. Ware, filed with

the motion indicates that each of the minor appellants

was assigned to the schools they are now attending in

accordance with their request or the request of their par

ents, and that none have sought transfers (R. 17-18).

As in the City of Jackson case above, the court below

heard the appellees’ motion to dismiss on April 5, 1963

(R. 20), and reported its decision to grant same in a letter

dated June 24, 1963. The lower court’s letter opinion

found that the Mississippi pupil assignment act, while it

does not “ compel integregation,” authorizes a child or

parent “ to request assignment to a school of his choice

and provides a full and adequate remedy to redress any

wrong if it occurs” (R. 23).

An order dismissing the action was signed on July 5,

1963 (R. 25), from which this appeal was filed (R. 26).

III.

Mason, et al. v. Biloxi Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, as with the City of Jackson and lueake County suits,

was filed by Negro parents on behalf of their children

and other similarly situated children following the appel

lee Board’s failure to respond to two written requests to

initiate desegregation of the public schools.

With the complaint, appellants filed a Motion for Pre

liminary Injunction (R. 14), which motion was set for

7

hearing on June 26, 1963, by the district court (R. 17).

Appellees however filed a motion to dismiss (R. 17), which

was set for hearing on June 19, 1963 (R. 18).

On June 19, 1963, appellants filed an affidavit signed by

one of them, Dr. Gilbert R. Mason (R. 14), which affidavit

attests to allegations in the complaint (R. 1-13) and avers

that the Biloxi public schools are racially segregated

(R. 19), that the Negro schools are clearly inferior (R. 20),

and that on March 18, 1963, a petition requesting the

appellee Board to desegregate the schools was presented at

a meeting of the Board (R. 22). The Board promised to

take the petition under consideration (R. 21), but having

received no response, appellants again petitioned the Board

by telegram on May 20, 1963 (R. 23A).

Appellees’ motion to dismiss (R. 17) states inter alia,

that “ the complaint fails to state a claim upon which

relief can be granted,” and adds, “ None of the plaintiffs

has exhausted any of the administrative remedies avail

able under Chapter 260 of the Mississippi Laws of 1954,

Sections 6334-01 to 6334-07, inclusive” (R. 17).

At the outset of the hearing on the motion to dismiss

held June 19, 1963 (R. 18), the court below requested and

was informed by both counsel that the City of Biloxi suit

was similar, to the City of Jackson and Leake County

cases. The court then announced that it had decided to

grant the motion to dismiss filed in those cases, would

examine all pleadings and briefs filed in the Biloxi case,

and if it found the case similar to the Jackson and Leake

County cases, would adhere to those rulings in the Biloxi

case.

Without further opinion, an order of dismissal was sub

sequently signed by the court below on July 5, 1963, and

appellants filed a Notice of Appeal (R. 24).

8

Specifications of Error

I. The court below erred in finding that Mississippi

statutes providing for racial segregation in the public

schools have been repealed or declared unconstitutional.

II. The court below erred in finding that appellants

must exhaust administrative remedies provided by state

law as a prerequisite to seeking federal court aid to enjoin

the infringement of their constitutional rights.

III. The court below erred in granting the motions to

dismiss, which at least as to the Jackson and Leake County

cases were in effect motions for summary judgment.

A R G U M E N T

I.

The Appellees Maintain Racially Segregated Schools

in Conformance With Mississippi Laws.

There is now at least token compliance with the United

States Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) in every state in the Union

with the exception of the State where these three cases

were brought.

This is not mere chance. As set forth in the complaints

(Jackson, R. 7; Leake Co., R. 7-8; Biloxi, R. 9), several

provisions of Mississippi’s Constitution and statutes ex

pressly require segregated schools. These provisions have

not been repealed or declared unconstitutional as found

by the court below (City of Jackson, R. 36).

9

Art. 8, Sec. 207 of the Mississippi Constitution states:

“ Separate schools shall be maintained for children of the

white and colored races.” 2

2 This old provision has not been amended or repealed. Indeed,

it has been strengthened by a 1960 amendment to sections 201 and

205 of Art. 8 which make it discretionary with the legislature

whether free public schools will be maintained by taxation or other

wise. Under the prior provisions, the maintenance of public schools

was a duty (§201), with at least four months of schooling required

during each scholastic year (§205). See 6 Race Rel. Law Rep. 314

(1961-62).

In addition, Art. 8 §213-B, enacted in 1954, empowers the legis

lature to abolish the public schools in the state or in any county

or school district. Sections 6232-21 to 6232-43 Miss. Code of 1942

Annot. empower the Legislature, the Governor and Boards of Trus

tees to close public schools when a determination is made that such

closure is in the best interest of a majority of the educable children

involved, or in the best interests of the school or school district.

Other southern states have attempted to use similar provisions

to close schools placed under federal court order to desegregate.

Hall v. St. Helena. Parish School Board, 197 P. Supp. 649 (E. D.

La. 1961), aff’d 368 U. S. 515; James v. Almond, 170 P. Supp.

331 (E. D. Ya. 1959), appeal dismissed, 359 U. S. 1006; Aaron v.

McKinley, 173 P. Supp. 944 (E. D. Ark. 1959), aff’d sub. nom.

Eaubus v. Aaron, 361 U. S. 197; Bush v. Orleans Parish School

\Board, 187 P. Supp. 42 (E. D. La. 1960), aff’d, 365 U. S. 569;

Allen v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, 198 P.

Supp. 497 (E. D. Va. 1961); Holmes v. Danner, 5 Race Rel. Law

Rep. 1092 (1961).

A legislative program enacted in 1953 and apparently intended

for the consolidation and reorganization of school districts,

§§6328-01 to 6328-117 Miss. Code (1942) Annot., nevertheless con

tains a provision, §6328-03 titled, “ Equalization of facilities be

tween races” providing that all school districts reorganized under

the act shall include the educable children of all races, and prior to

approval of such reorganization, a satisfactory plan of “equali

zation of facilities between the races shall be submitted and

approved . . . ”

10

§3841.3 Miss. Code 1942 Annot. authorizes the state

Attorney General to represent any school official in suits

challenging the validity under the constitution and laws

of the United States of a state law determining inter alia

what persons shall attend or be enrolled in state colleges

and schools. It was enacted in 1958.

§4065.3 Miss. Code 1942 Annot. requires the entire

executive branch of the state government:

“ to prohibit, by any lawful, peaceful and constitutional

means, the implementation of or the compliance with

the integregation decisions of the United States

Supreme Court of May 17, 1954 (347 U. S. 483, 74

S. Ct. 686, 98 L. ed. 873) and of May 31, 1955 (349

U. S. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753, 99 L. ed. 1083), and to pro

hibit by any lawful, peaceful and constitutional means,

the causing or mixing or integration of the white

and Negro races in public schools, . . . by any branch

of the federal government. . . . ”

§6220.5 Miss. Code 1942 Annot., enacted in 1955 sub

jects any white person attending a school receiving state

funds of high school level or below with a Negro to prose

cution and upon conviction to a jail term of up to six

months, or a fine of up to $25.00 or both.

§6334-11 Miss. Code 1942 Annot,., enacted in 1960, for

bids the enrollment or attendance of a child in any school

except the school district of his residence, unless the child

is transferred to another school district in accord with

state statutes.

Under this broad legislative umbrella, the public schools

throughout the state of Mississippi, including those under

appellees’ control, have continued to function on a segre

gated basis without apparent regard for the many decisions

of this Court and the United States Supreme Court requir

11

ing a prompt and reasonable start toward school desegre

gation.

The court below found that the Mississippi statutes

which prior to the Brown case in 1954, required segrega

tion in public schools “ have been repealed or declared un

constitutional, . . . ” (City of Jackson, R. 36). But the

statutory provisions set forth in the complaints and re

viewed above have not been repealed nor expressly declared

unconstitutional. There has been, moreover, no repudia

tion of these provisions by appellees, and no indication

that they will not continue to maintain segregated schools

in conformance with these statutes unless this Court

orders otherwise.

The intent of these provisions is clearly the maintenance

of racial segregation in Mississippi’s public schools. This

Court has taken judicial notice that “ the state of Missis

sippi maintains a policy of segregation in its schools and

colleges.” Meredith v. Fair, 298 F. 2d 696, 701 (5th Cir.

1962); 305 F. 2d 343, 344-45 (5th Cir. 1962). The appellee

Boards are following this policy. Any other conclusion

would fly in the face of “what everybody knows . . . ”

Meredith v. Fair, 305 F. 2d 343, 344 (5th Cir. 1962).

1 2

II.

Appellants Are Entitled to the Relief Sought Without

Exhausting Remedies in Mississippi’s Pupil Assignment

Act.

Assuming, arguendo, a serious question as to whether

appellants must exhaust administrative procedures estab

lished by state law prior to utilizing the provisions of 28

United States Code, §1983 to enjoin appellee school boards

from denying their constitutional rights to a desegregated

education, that question is now settled by the Supreme

Court’s decision in McNeese v. Board of Education, 373

U. S. 668 (19<?3). There, the Court said, . . relief under

the Civil Rights Act may not be defeated because relief was

not first sought under state law which provided a remedy.”

The federal remedy is supplementary to the state remedy

said the Court quoting its opinion in Monroe v. Pape, 365

U. S. 167, 183, and the state remedy need not be sought and

refused before the federal one is invoked. 373 U. S. at 671.

But, as this Court said in Armstrong v. Board of Educa

tion of Birmingham,------F. 2d------- (5th Cir. Jul. 12,1963),

in which the McNeese case, supra, is followed, there has

never been any doubt concerning this Court’s position on

the necessity of exhaustion of pupil assignment law reme

dies. In Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 242 F. 2d

156 (1957) cert. den. 354 U. S. 948, the first appeal here of a

case involving a state pupil assignment law, a state con

stitutional provision and state statutes required separate

assignments based on race. See 242 F. 2d at 159. This

Court, while basing its ruling on other grounds, stated that

it would be unfair to remit thousands of minor Negro chil

dren to thousands of administrative hearings before the

school board for relief, “ so long as assignments could be

made under the Louisiana Constitution and Statutes only

13

on a basis of separate schools for white and colored chil

dren. . . .” 242 F. 2d at 162.

Acknowledging the existence of the Florida Pupil Assign

ment Law of 1956 in Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction

of Dade County, 246 F. 2d 913 (5th Cir. 1957), this Court

held that exhaustion of its provisions was not necessary so

long as racial segregation was required throughout the

school system. It is true that Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham

Board of Education, 162 F. Supp. 372 (N. D. Ala. 1958),

aff’d 358 U. 8. 101 (1958) held that the Alabama Pupil

Assignment Act was not invalid on its face, but Judge

Rives, who had written the opinion in Shuttlesworth pointed

out in Holland v. Board of Public Instruction of Palm

Beach, Florida, 258 F. 2d 730, 732 (5th Cir. 1958), that this

decision did not alter the courts’ position that the remedies

provided by pupil assignment laws need not be exhausted

prior to the filing of a school desegregation suit.

This point was re-emphasized in the second appeal of the

Gibson case. 272 F. 2d 763 (5th Cir. 1959), where Judge

Rives, again speaking for the Court, found that the as

signment of all students according to race under the Florida

Pupil Assignment Act did not constitute a sufficient plan

of desegregation even when accompanied by an “ Implemen

tation Resolution.” Subsequently in Mannings v. Board of

Public Instruction, 277 F. 2d 370 (5th Cir. 1960), this Court

explained again that the exhaustion of administrative reme

dies is not a prerequisite to a suit to enjoin segregated

schools. Similar statements and holdings are found in

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction, 306 F. 2d 862,

869 (5th Cir. 1962), Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board,

308 F. 2d 491, 499-501 (5th Cir. 1962); and Potts v. Flax,

313 F. 2d 284, 290 (5th Cir. 1963).

In recent months, this Court has granted injunctions

pending appeals in ordering immediate relief for appellants

14

seeking to desegregate schools in Birmingham and Mobile,

Alabama. Davis v. School Commissioners of Mobile

County, ------ F. 2d ------ (5th Cir. Jul. 9, 1963); Arm

strong v. Board of Education of Birmingham, ------ F. 2d

------ (5th Cir., Jul. 12, 1963). In neither case did plaintiffs

attempt to exhaust administrative remedies under the Ala

bama Pupil Assignment Act prior to filing suit.

Appellants submit that there is no reason why the rules

as to exhaustion of administrative remedies, uniformly ap

plied by this Court since 1956 to Pupil Assignment Acts in

Louisiana, Florida, Alabama, and Texas should not apply

with special force on the Mississippi Act, §§6334-01 to

6334-07, Miss. Code (1942) Annot. which is similar to those

considered in the other states, particularly since the policy

of school segregation in Mississippi is more deeply en

trenched in that state’s laws today than in the period prior

to Brown v. Board of Education, 347 F. S. 483 (1954).

III.

Appellants Are Entitled to Orders Reversing the Dis

missal o f These Cases and Other Appropriate Relief in

Accordance With the Decisions o f This Court.

The relief here sought is neither novel, unique or extraor

dinary. Appellants ask merely that this Court provide

them with rulings similar to those already handed down in

countless other school desegregation cases where all the

defenses raised here by appellees have been considered and

rejected. Appellants respectfully suggest that the court be-

low’s opinions, when reviewed in the light of these cases,

necessitates reversal of the orders of dismissal with in

structions to grant appellants their requested relief in at

least two of the cases.

15

There is in Mississippi simply no basis for a finding

that the state no longer enforces a policy of racial segrega

tion in its public schools and colleges. To the contrary,

since 1954 there are more provisions in the State Constitu

tion and Statutes aimed at maintaining school segregation

than ever. None of the provisions requiring segregation

have been repealed, and the appellee boards have operated

the schools under their control in complete conformance

with them. The Boards have totally ignored appellants’ pe

titions to initiate desegregation even though this method

of notice has been frequently approved by this Court and

have adopted transfer standards which, administered in ac

cordance with a continuing policy of initial assignments

based on race, result in the appellee school systems being as

segregated by race now as they ever were.

These are the facts and the precedents which were avail

able to the court below and from which its decisions in these

cases were made. Not only were the orders of dismissal

final and appealable, Mannings v. Board of Public Instruc

tion, 277 F. 2d 370, 372 (5th Cir. 1960) but, at least as to the

City of Jackson and Leake County cases, they were deci

sions based on the merits.

Under Buie 12(b), Federal Buies of Civil Procedure:

“ If, on a motion asserting the defense numbered (6)

to dismiss for failure of the pleading to state a claim

upon which relief can be granted, matters outside the

pleading are presented to and not excluded by the

court, the motion shall be treated as one for summary

judgment and disposed of as provided in Buie 56, . . .”

The motions to dismiss filed by appellees in all three

cases asserted as the first defense: “The complaint fails to

state a claim upon which relief can be granted.” In the

City of Jackson and Leake County cases, appellees pre

16

sented affidavits in support of these motions, which affi

davits were “ not excluded by the court” , but were expressly

referred to by the court in its opinions (City of Jackson, R.

36; Leake County, R. 23).

Applying this settled rule to these two cases, justifies a

conclusion that the orders of dismissal were based on the

merits of the cases. Smoot v. State Farm Mutual Automo

bile Insurance Co., 299 F. 2d 525 (5th Cir. 1962); Fowler v.

Curtis Pub. Co., 78 F. Supp. 303, aff’d 182 F. 2d 377 (D. C.

Cir. 1950). See 2 Moore’s Federal Practice 2255-2257. This

being so, appellants submit that the City of Jackson and

Leake County decisions should be reversed and returned to

the district court with instructions to promptly initiate de

segregation of the public schools.

In the City of Biloxi case, appellees filed no affidavit to

support their motion to dismiss. Appellants had filed an

affidavit in support of their motion for preliminary injunc

tion (Biloxi, R. 19), but the court entered no opinion with

its order to dismiss the Biloxi case, and the record on ap

peal does not indicate whether the court considered appel

lants’ affidavit or matters outside the pleadings in reaching

its decision. Thus, appellants submit that the decision in

the City of Biloxi case should be reversed with directions

to promptly hear and decide appellants’ motion for a pre

liminary injunction.

In conclusion, the records in these appeals are evidence

that appellees and other Mississippi officials are probably

less willing to comply with the Brown case now than they

were in 1954. Thus, whatever the problems in effectuating

the desegregation of the appellees’ schools, it is unlikely

that more time will prove helpful in their solution. More

over, as this Court has said, “ The vindication of rights

guaranteed by the Constitution cannot be conditioned upon

17

the absence of practical difficulties.” Orleans Parish School

Board v. Bush, 242 F. 2d 156, 166 (5th Cir. 1957).

The Supreme Court in Watson v. City of Memphis, 373

U. S. 526 (1963), and Goss v. City of Knoxville, 373 U. S.

683 (1963) placed a new urgency on its earlier decision in

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955), requir

ing school boards to make a prompt and reasonable start

toward school desegregation.

This Court’s recent decisions in Armstrong v. Birming

ham Board of Education, — — F. 2d —— (July 12, 1963);

Davis v. Mobile School Board,------F. 2d -------- (July 9,

1963); and St ell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of

Education, 318 F. 2d 425 (5th Cir. 1963), also signify that

lengthy litigation delays will no longer be permitted to de

lay to the point of denial the constitutional right of Negro

children to obtain a desegregated education in the public

schools of their home towns. That appellants are entitled

to such an education is as apparent from the cases as their

presence here is reflective of their desire.

18

CONCLUSION

W h e r e fo r e , for all the foregoing reasons, appellants re

quest that the orders of the court below dismissing these

cases be reversed with directions in the City of Jackson and

Leake County cases to enter orders requiring the appellee

school boards to promptly initiate school desegregation in

accordance with the orders of this Court, and with direc

tions in the City of Biloxi case to promptly hear and decide

appellants’ motion for a preliminary injunction.

Respectfully submitted,

J a c k H. Y o ung

1151/2 N. Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

R. J ess B r o w n

125% N. Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

J a c k G reen berg

C o n sta n c f B a k e r M o tley

D er r ic k A. B e l l , Jr.

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Appellants