Simkins v Moses H Cone Memorial Hospital Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

February 1, 1963

53 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Simkins v Moses H Cone Memorial Hospital Brief for Appellant, 1963. ebf5a660-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4c5b8cb0-970d-467e-b91c-524533678fa1/simkins-v-moses-h-cone-memorial-hospital-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

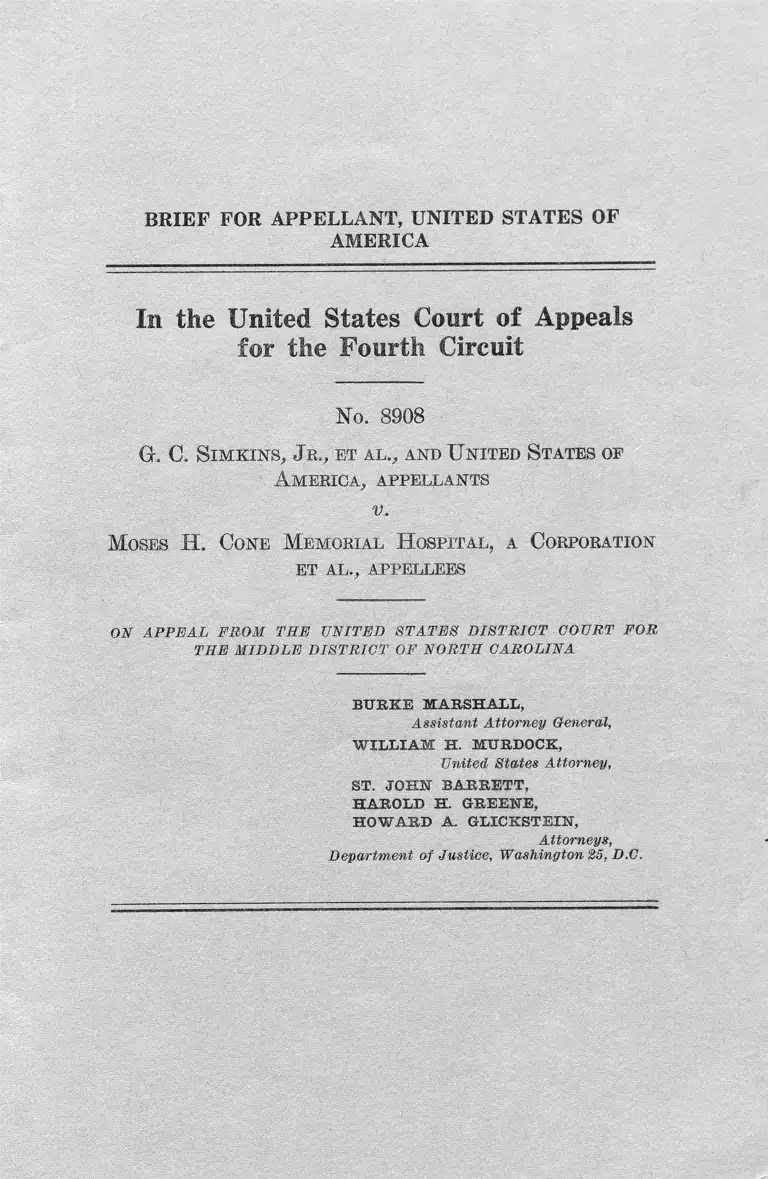

BRIEF FOR APPELLAN T, UNITED STATES OF

AM ERICA

In the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 8908

GL C. Sim kins , J r., et al., and U nited States of

A merica, appellants

v.

M oses EL Cone M emorial H ospital, a Corporation

ET AL., APPELLEES

ON A PPE A L FROM THE UNITED STATES D ISTR IC T COURT FOR

THE M ID D LE D ISTR IC T OF NORTH CAROLINA

BURKE M ARSHALL,

Assistant A ttorn ey General,

W IL L IA M H. MURDOCK,

United States Attorney,

ST. JOHN BARRETT,

HAROLD H. GREENE,

HOW ARD A. GLICKSTEIKT,

A ttorneys,

Departm ent o f Justice, W ashington 25, D.C.

I N D E X

Statement of the case___________________________________ 1

Questions presented_____________________________________ 7

Statutes involved________________________________________ 8

Statement of facts_______________________________ 10

Argument_______________________________________________ 15

I. The conduct of defendant hospitals in discriminat

ing against N egro patients is State action----------- 15

A. The controlling principles________________ 15

B. The hospitals are acting for the State and

are subject to constitutional limitations. 20

C. The non-discrimination provision of the

Hill-Burton A ct_______________________ 32

II. The provision of the Hill-Burton Act sanctioning

the construction of separate-but-equal hospital

facilities is unconstitutional____________________ 40

Conclusion______________________________________________ 48

TABLE OF CASES

Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F. 2d 97 (C.A. 8, 1958)------------------- 17

American Communications Ass’n v. Douds, 339 U.S. 382

(1950)________________________________________________ 16

Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 297 H.S. 288

(1936)_________________________________ 40

Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750 (C.A. 5, 1961)________ 35,43

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954)________________ 16,43, 45

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Gompany, 280 F. 2d 531

(C.A. 5, 1960)________________________________________ 35

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454 (1960)------------------------- 23

Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707 (M.D. Ala., 1956),

affirmed, 352-U.S. 903 (1956)---------------------------------------- 42

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)------------ 42

Burton v. United States, 196 U.S. 283 (1905)--------------------- 40

Button v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715

(1961)____________________________________ 5,17,18,38,41,44

Page

( i )

6T7083— 63— 1

Catlette v. United States, 132 F. 2d 902 (C.A. 4, 1943)_____ 45

City of Greensboro v. Simpkins, 246 F. 2d 425 (C.A. 4, 1957),

affirming, 149 F. Supp. 562 (M.D. N.C. 1957)_________ 17

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883)_________________ 15, 19, 34

Coke v. City of Atlanta, 184 F. Supp. 579 (N.D. Ga. 1960)_ 17

Cooper y. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958)_______________________ 16,44

Dawson v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 220 F. 2d

386 (C.A. 4, 1955), affirmed, 350 U.S. 877 (1955)_______ 42

Eaton v. Board of Managers of James Walker Memorial

Hospital, 261 F. 2d 521 (C.A. 4, 1958), cert, denied, 359

U.S. 984 (1958)__________________________ _____________ 5

Flemming v. South Carolina Electric and Gas Company, 224

F. 2d 752 (C.A. 4, 1955), appeal dismissed, 351 U.S. 901 _ 35

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157 (1961)________________ 28

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960)_______________ 46

Henry v. Greenville Airport Commission, 279 F. 2d 751 (C.A.

4, 1960)______________________________________________ 42

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U.S. 81 (1943)__________ 46

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24 (1948)_______________________ 46

Jones v. Marva Theatres, 180 F. Supp. 49 (D. Md. 1960)__ 17

Lawrence v. Hancock, 76 F. Supp. 1004 (S.D. W. Va. 1948)_ 17

Lynch v. United States, 189 F. 2d 476 (C.A. 5, 1951)______ 45

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501 (1946)__________________ 23

Ming v. Horgan, 3 RR. L. Rep. 693 (Cal. Super. Ct. 1958)- 46

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Association, 347 U.S. 971

(1954), vacating and remanding, 202 F. 2d 275 (C.A. 6,

1953)________ 17

McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Ry. Co., 235 U.S.

151 (1914)________________________________________ 37,38,44

Nash v. Air Terminal Services, 85 F. Supp. 545 (E.D. Va.

1949)_____________________________________________ 17

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U.S. 73 (1932)_____________________ 23

Picking v. Pennsylvania R. Co., 151 F. 2d 240 (C.A. 3,

1945)_________________________________________________ 45

Ples.sy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896)__________________ 37,43

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944)__________________ 23

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville Railroad Co., 323 U.S. 192

(1944)_________________________________________________ 43,45

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880)__________ 42

n

Page

Tate v. Department of Conservation, 133 F. Supp. 53 (E.D.

Ya., 1955), affirmed, 231 F, 2d 615 (C.A. 4, 1956), cert.

denied, 352 U.S. 838 (1956)------------------------------------------- 17, 42

Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461 (1953)------------------------------- 23

United States v. Auto Workers, 352 U.S. 567 (1957)---------

Western Union Telegraph Co. v. Foster, 247 U.S. 105 (1918) _ 46

Williams v. Hot Shoppes Inc., 293 F. 2d 835 (C.A. D.C.

1961)_________________________________________________ 36

STATUTES

28 U.S.C. 2403__________________________________________ 3

42 U.S.C. 291(a)______________________________ 21,28,30,32,41

42 U.S.C. 291b(a)(3)------------------------------------------------------- 21

42 U.S.C. 291d__________________________________________ 28

42 U.S.C. 291e(f)________ 3, 7, 13, 20, 22, 29, 30, 31, 32, 39, 42, 47

42 U.S.C. 291f(a)(4)_____________________________________ 13,21

42 U.S.C. 291h(a)_______________________________________ 28

42 U.S.C. 291h(e)_______________________________________ 34

42 U.S.C. 291m_________________________________________ 29, 30

42 U.S.C. 291n__________________________________________ 28

42 U.S.C. 2641-2643____________________________________ 26

42 U.S.C. 2642(b)_______________________________________ 26

42 C.F.R. 53____________________________________________ 25

42 C.F.R. 53.111________________________________________ 8,26

42 C.F.R. 53.112______________________________ 2, 8, 9, 14, 15, 26

42 C.F.R. 53.113______________________________________ 9, 14,26

42 C.F.R. 53.127(d)_____________________________________ 25

Rule 24a of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure------------- 3

MISCELLANEOUS

H. Rep. No. 2519, 79th Cong____________________________ 29

BLR. No. 1756, 87th Cong., 2d Sess--------------------------------- 26

Senate Report No. 674, 79th Congress, 1st Sess----------------21, 29

Hearings Before Senate Committee on Education and

Labor on S. 191, 79th Cong., 1st Sess--------------------------- 22

91 Cong. Rec. 11714-------------------------------------------------------- 29

91 Cong. Rec. 11716------- 24

Cong. Rec. August 28, 1962, p. 16856------------------------------ 27

Ill

Page

In the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 8908

G-. C. S im kins , Jr., et al., and U nited States op

A merica, appellants

v.

M oses H. Cone M emorial H ospital, a Corporation

et al., appellees

ON A P P E A L FROM T E E UNITED STATES D ISTR IC T COURT FOR

TIIE M ID D LE D IST R IC T OF N O R TE CAROLINA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On February 12, 1962, the plaintiffs, Negro citizens

suing on behalf of themselves and other Negro

physicians, dentists and patients similarly situated,

filed a complaint seeking injunctive and declaratory

relief in the United States District Court for the

Middle District of North Carolina (4aj. The com

plainants alleged, inter alia, that the defendants—-the

Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, its director,

Harold Bettis, the Wesley Long Community Hospital

and its administrator, A. 0. Smith—had discriminated

against them because of their race in violation of the

Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United

2

States Constitution (13a-14a). The relief sought was

(1) an injunction restraining the defendants from

continuing to enforce the policy, practice, custom and

usage of denying plaintiff physicians and dentists the

use of staff facilities at the Moses H. Cone and Wesley

Long Community Hospitals in Greensboro, North

Carolina, on the ground of race; (2) an injunction-

restraining defendants from continuing to enforce the

policy, practice, custom and usage of denying and

abridging admission of patients on the basis of race

and refusing to permit patients, on the basis of race,

to be treated by their own physicians and dentists at

the Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital and the Wesley

Long Community Hospital in Greensboro, North Caro

lina ; (3) a declaratory judgment declaring a portion

of the Hill-Burton Act (Hospital Survey and Con

struction Act of 1946, 60 Stat. 1041, as amended; 42

ILS.C. 291 et seq.) and a regulation pursuant thereto

(42 C.F.R. 53.112; 21 F.R. 9841), which authorize

the construction of hospital facilities and the promo

tion of hospital services with funds of the United

States on a separate-but-equal basis, unconstitutional,

invalid and void as violative of the Fifth and Four

teenth Amendments to the United States Constitution

(17a-18a). Subsequently (on May 4, 1962) the plain

tiffs filed a motion for preliminary injunction and a

motion for summary judgment (68a; 72a).

On April 2, 1962, the defendants filed a motion to

dismiss for lack of jurisdiction over the subject mat

ter for the reason that the plaintiffs were seeking

redress for the alleged invasion of their civil rights

by private corporations and individuals (19a).

3

Since this proceeding is one in which “ the constitu

tionality of * * * [an] Act of Congress affecting the

public interest * * * [has been] drawn in question,”

the United States, pursuant to 28 U.S.C. 2403 and

Rule 24(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

moved on May 8, 1962, to file a pleading in interven

tion (165a). This pleading in intervention alleged

that “ the Moses TL Cone Memorial Hospital has

refused and is presently refusing to admit Negro

patients on the same terms and conditions as white

patients;” that “ the Wesley Long Community Hos

pital has refused and is refusing to admit Negro

patients on the basis of race;” that the conduct of

the hospitals complained of was authorized by the

North Carolina State Plan of Hospital Construction

which was adopted pursuant to the Hill-Burton Act

and the regulations issued thereunder; and that the

conduct of the hospitals violates the Fourteenth

Amendment of the Constitution (171a). The United

States prayed that the District Court declare that so

much of 42 U.S.C. 291e(f) as authorizes the Surgeon

General to prescribe regulations concerning separate

hospital facilities for separate population groups is

unconstitutional, null and void (171a-172a).

On August 9, 1962, the United States moved for

summary judgment and asked for: (1) declaratory

relief with respect to the challenged portion of the

Hill-Burton Act, and (2) an injunction enjoining the

defendant hospitals from discriminating, on account

of race and color, in the admission of patients (189a).

On June 26, 1962, the District Court held a full

4

hearing on all pending motions, at the conclusion o f

which an order was entered granting the motion of

the United States to intervene (188a). The case was

submitted to the District Court on the documentary'

evidence filed by the parties, and on December 5, 1962,

the Court issued its findings of fact, conclusions of law

and opinion (211 U Supp. 628; 195a-222a). The

Court noted that “ the sole qxiestion for determination

is whether the defendants have been shown to be so

impressed with a public interest as to render them

instrumentalities of government, and thus within the

reach of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to

the Constitution of the United States. In making this

determination, it is necessary to examine the various

aspects of governmental involvement which the plain

tiffs contend add up to make the defendant hospitals

public corporations in the coUstitutional sense”

(206a-207a). The Court analyzed each of the factors

alleged to demonstrate state involvement and rejected

each as a sufficient basis for creating constitutional

obligations (221a).

With respect to the receipt of Hill-Burton funds,

the Court noted that “ all funds received, or to be

received, by both hospitals were allocated and granted

to, and accepted by, the hospitals with the express

written understanding that admission of patients to

the hospital facilities might be denied because of race,

color or creed” (214a). The Court found that the

fimds granted were unrestricted and that the federal

regulations governing Hill-Burton appropriations are

5

designed to ensure properly planned and well con

structed facilities and not to control internal opera

tions. The Court concluded (217a) :

Since no state or federal agency has the right

to exercise any supervision or control over the

operation of either hospital by virtue of their

use of Hill-Burton funds, other than factors

relating to the sound construction and equip

ment of the facilities, and inspections to ensure

the maintenance of proper health standards,

and since control, rather than contribution, is

the decisive factor in determining the public

character of a corporation, it necessarily fol

lows that the receipt of unrestricted Hill-

Burton funds by the defendant hospitals in no

way transforms the hospitals into public

agencies.

The Court also rejected the argument that a differ

ent result would be required if instead of concentrat

ing on individual elements it considered the totality

of governmental contacts. The Court accepted the

defendants’ argument that “ zero multiplied by any

number would still equal zero” (218a). It distin

guished Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority,

365 TJ.S. 715 (1961) and relied on Eaton v. Board of

Managers of James Walker Memorial Hospital, 261

F. 2d 521 (C.A. 4, 1958), cert, denied, 359 U.S. 984

(1958)d

1In that case, although there were certain contacts between

the hospital and governmental bodies, the Court found that

the discriminatory policies of the hospital were not subject to

constitutional restriction.

677083— 68-------2

6

The Court expressly refused to pass on the constitu

tionality of the Hill-Burton proviso, stating (220a-

221a) :

It is a cardinal principle that courts do not

deal in advisory opinions, and avoid rendering

a decision on constitutional questions unless it

is absolutely necessary to the disposition of the

case. Barr v. Matteo, 355 U.S. 171, 2 L. Ed. 2d

179, 78 S. Ct. 204 (1957). I f the defendants

were claiming any right or privilege under the

separate but equal provisions of the Hill-

Burton Act, it would perhaps be necessary to

the disposition of the case to rule upon the con

stitutionality of those provisions. Here, how

ever, as earlier stated, the defendants make no

such claim, and it is unnecessary for the Court,

as requested by the United States, to advise the

Surgeon General with respect to his legal obli

gations under the Act. There has been no

showing that the statute in question has resulted

in depriving the plaintiffs or any other citizens

of their constitutional rights. The only issue

involved in this litigation is whether the defend

ants have become governmental agencies in

the constitutional sense by the acceptance of

public fimds in the construction and equipment

of their hospitals, and their other involvements

with public agencies. The constitutionality of

the separate but equal provisions of the Hill-

Burton Act is not an issue, and a declaration

as to its constitutionality is not necessary to

the disposition of the case.

What the plaintiffs and the United States

are really asking in their prayer for declara

tory relief is an order desegregating all private

facilities receiving Hill-Burton funds over a

7

period of years, even though the funds were

given with the understanding that the private

facilities might retain their freedom to conduct

their private affairs in their own way. This

court is not prepared to grant the declaratory

relief prayed for, thereby retroactively altering

established rights, particularly when it is unnec

essary to do so, in deciding the jurisdictional

question.

The Court concluded that since the defendants were

“ private persons and corporations, and not instrumen

talities of government (221a),” they were not subject

to the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments and that,

consequently, the Court was without jurisdiction over

the subject matter of the action. The motions for

summary judgment by the plaintiffs and by the United

States were denied and the defendants’ motion to

dismiss the action for lack of jurisdiction over the

subject matter was granted (223a).

Plaintiffs and the United States filed notices of

appeal January 4 and 11, 1963 respectively (224a,

225a).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether, as a result of defendants’ participation

in the Hill-Burton hospital system, they are governed

by the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment or

the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment in their admission policies.

2. Whether those portions of 42 U.S.C. 291e(f) and

42 C.F.R. 53.112 which authorize racial discrimination

violate the Fifth or Fourteenth Amendments.

8

STATUTES INVOLVED

42 U.S.C. 291e(f) provides:

( f ) That the State plan shall provide for

adequate hospital facilities for the people re

siding in a State, without discrimination on

account of race, creed, or color, and shall pro

vide for adequate hospital facilities for persons

unable to pay therefor. Such regulation may

require that before approval of any application

for a hospital or addition to a hospital is recom

mended by a State agency, assurance shall be

received by the State from the applicant that

(1) such hospital or addition to a hospital will

be made available to all persons residing in the

territorial area of the applicant, without dis

crimination on account of race, creed, or color,

but an exception shall be made in cases where

separate hospital facilities are provided for

separate population groups, if the plan makes

equitable provision on the basis of need for fa

cilities and services of like quality for each such

group; and (2) there will be made available in

each such hospital or addition to a hospital a

reasonable volume of hospital services to per

sons unable to pay therefor, but an exception

shall be made if such a requirement is not feasi

ble from a financial standpoint.

42 C.F.R. §§ 53.111-53.113 provide:

§ 53.111 General. The State plan shall pro

vide for adequate hospital, diagnostic or treat

ment center, rehabilitation facility, and nursing

home service for the people residing in a State

without discrimination on account of race,

creed, or color, and shall provide for adequate

facilities of these types for persons unable to

pay therefor.

9

§ 53.112 Nondiscrimination. Before a con

struction application is recommended by a State

agency for approval, the State agency shall ob

tain assurance from the applicant that the

facilities to be built with aid under the Act will

be made available without discrimination on ac

count of race, creed, or color, to all persons

residing in the area to be served by that facility.

However, in any area where separate hospital,

diagnostic or treatment center, rehabilitation or

nursing home facilities, are provided for sep

arate population groups, the State agency may

waive the requirement of assurance from the

construction applicant if (a) it finds that the

plan otherwise makes equitable provision on

the basis of need for facilities and services of

like quality for each such population group in

the area, and (b) such finding is subsequently

approved by the Surgeon General. Facilities

provided under the Federal Act will be consid

ered as making equitable provision for separate

population groups when the facilities to be

built for the group less well provided for here

tofore are equal to the proportion of such group

in the total population of the area except that

the State plan shall not program facilities for

a separate population group for construction

beyond the level of adequacy for such group.

§ 53.113 Hospital, diagnostic or treatment

center, rehabilitation facility, and nursing home

service for persons unable to pay therefor.

Before a construction application is recom

mended by a State agency for approval, the

State agency shall obtain assurance that the

applicant will furnish a reasonable volume of

free patient care. As used in this section, “ free

10

patient care” means hospital, diagnostic or

treatment center, rehabilitation facility, or nurs

ing home service offered below cost or free to

persons unable to pay therefor, including under

“ persons unable to pay therefor” , both the

legally indigent and persons who are otherwise

self-supporting but are unable to pay the full

cost of needed care. Such care may be paid

for wholly or partly out of public funds or

contributions of individuals and private and

charitable organizations such as community

chests or may be contributed at the expense of

the hospital itself. In determining what con

stitutes a reasonable volume of free patient care,

there shall be considered conditions in the area

to be served by the applicant, including the

amount of free care that may be available other

wise than through the applicant. The require

ment of assurance from the applicant may be

waived if the applicant demonstrates to the sat

isfaction of the State agency, subject to subse

quent approval by the Surgeon General, that

furnishing such free patient care is not feasible

financially.

STATEMENT OF FACTS 2

Six of the plaintiffs are qualified physicians and

three are qualified dentists, all practicing in Greens

boro, North Carolina (197a). These plaintiffs seek

admission to the staff facilities of the Cone Hospital

and the Long Hospital without discrimination on the

basis of race (197a). They have applied for admis

2 We emphasize only those facts that are pertinent to the

argument made in this brief. A complete statement o f the facts

is contained in plantiffs’ brief, pp. 5-19.

11

sion to the staff of Cone Hospital and have been re

jected, and they have requested staff application forms

from Long Hospital but these requests have not been

honored (198a).

Plaintiffs A. J. Taylor and Donald R. Lyons are in

need of medical treatment and desire to enter either

the Wesley Long Community Hospital or the Moses

H. Cone Memorial Hospital where complete medical

equipment and the best facilities for treatment in the

Greensboro area are available. Plaintiffs also desire

treatment from their personal physicians (197a).

They cannot, however, be admitted to the Long Hos

pital since that hospital follows a policy, practice,

custom and usage of refusing to admit Negroes to the

use of its facilities. Plaintiffs cannot enter the Cone

Hospital on the same basis as whites nor can they

enter the Cone Hospital and be treated by their per

sonal physicians because the Cone Hospital will not

admit Negro doctors or dentists to staff facilities

(198a).

Defendants, Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, Inc.,

and Wesley Long Community Hospital, Inc., are

North Carolina corporations that have established and

now maintain in Greensboro, North Carolina, the

Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital and the Wesley

Long Community Hospital, respectively, which are

non-profit, tax exempt and State licensed (197a). De

fendant Harold Bettis is the Director of the Moses H.

Cone Memorial Hospital, Inc. and defendant A. O.

Smith is the Administrator of the Wesley Long Com

munity Hospital (198a).

12

The Long Hospital is a charitable corporation gov

erned by a self-perpetuating board of twelve trustees

(200a). The Cone Hospital is also a charitable North

Carolina corporation governed by fifteen trustees of

which five are appointed by agents or subdivisions of

the State and one is appointed by a “public agency”

(199a).3

Both hospitals are exempt from ad valorem taxes

assessed by the City of Greensboro and Guilford

County at tax rates of $1.27 and $0.82 per $100 valu

ation respectively (200a).

The Cone Hospital cooperates in a nurses’ training

program with two tax-supported institutions of higher

learning.4

The Cone and Long Hospitals are part of the Hill-

Burton Hospital system. Plaintiffs, in their brief,

have set forth in detail the nature of the relationship

between the defendant hospitals and the Hill-Burton

system. They also discuss the extent of federal finan

cial contributions to defendant hospitals, the nature

of the North Carolina State Plan of Hospital Care

3 Three members are appointed by the Governor of North

Carolina; one member is named by the Board of Commissioners

of the City of Greensboro; one member is named by the Board

of Guilford County; and one member by the Guilford County

Medical Society (199a). The Guilford County Medical So

ciety is a component o f the Medical Society o f North Carolina

which appoints the Board of Medical Examiners o f North

Carolina and elects four members of the State Board of Health

(11a). The District Court assumed for purposes o f its decision

that the Guilford County Medical Society is a “ public agency”

(207a).

4 See plaintiffs’ brief, pp. 18-19, for a detailed description

of that program.

13

and the sundry federal and state controls over defend

ants’ activities.5

These controls are divided into seven categories:

(1) Controls over the construction contracts and the

construction period;

(2) Controls over details of hospital construction

and equipment;

(3) Controls over future operations and status of

hospitals;

(4) Controls over details of hospital maintenance

and operation;

(5) Control of size and distribution of facilities;

(6) Rights of project applicants and state agencies;

(7) Regulation of racial discrimination.

We believe that plaintiffs’ description of defendants’

relationship to the Hill-Burton system is well stated,

and we will not duplicate their discussion. However,

we would like to add the following to the discussion

of the manner in which the Hill-Burton Act regulates

racial discrimination and the provision of services to

the needy.

A State, to participate in the Hill-Burton program,

is required to submit for approval by the Surgeon

General a state plan setting forth a “ hospital con

struction program” which, among other things, “meets

the requirements as to lack of discrimination on ac

count of race, creed, or color, and for furnishing

needed hospital services to persons unable to pay

therefor, required by the regulations prescribed under

section 291 e (f). * * *” (42 U.S.C. 291f(a)(4).)

5 See plaintiffs’ brief, pp. 8-18.

677083— 63- -3

(14

The State may meet the non-discrimination require

ment “ in any area where separate hospital, diagnostic

or treatment center, rehabilitation or nursing home

facilities, are provided for separate population groups

* * * if * * * the plan otherwise makes equitable pro

vision on the basis of need for facilities and services

of like quality for each such population group in the

area, and * * * such finding is subsequently approved

by the Surgeon General.” (Regulation 52.112, 42

C.F.R., 53.112.6) Where a separate-but-equal plan is

in operation, the individual applicant for aid need not

give any assurance that it will not discriminate and,

in fact, may expressly indicate on its application

form that “ certain persons in this area will be denied

admission to the proposed facilities as patients because

of race, creed, or color” (93a). The arrangement to

extend aid is formally concluded by a memorandum

of agreement signed by representatives of the appli

cant, the State agency and the Surgeon General.

Where a State seeks to meet the non-discrimination

requirement by programming separate facilities for

separate population groups, it is required to submit

to the Surgeon General a “ Non-Discrimination

Report” (Form PH S-8) (120a-121a). The prepa

ration of this report requires the State agency specifi

cally to enumerate the number of hospital beds

available for each racial group. The North Carolina

6 The requirement to provide care for the needy will be

waived “ if the applicant demonstrates to the satisfaction of

the State agency, subject to subseqiient approval by the Sur

geon General, that furnishing such free patient care is not

feasible financially.” (Regulation 53.113, 42 C.F.R. 53.113.)

15

Medical Care Commission submitted such a “ Non-

Discrimination Report” on January 3, 1962 (120a-

121a).

That report lists the L. Richardson Memorial Hos

pital as having 91 acceptable beds for “ non-white”

patients and none for “ white” ; Wesley Long Com

munity Hospital as having none for “ non-white”

patients and 220 for “ white” ; and Moses H. Cone

Hospital as having none for “ non-white” and 182

for “ white” (120a).

Significant duties are imposed on the Surgeon Gen

eral with respect to the “ Non-Discrimination Report.”

Regulation 53.112 provides that a State agency’s find

ings must be approved by the Surgeon General.7

Consequently the Surgeon General has the duty of

determining whether the State properly has applied

the separate-but-equal formula, i.e., whether the

State’s plan actually makes “ equitable provision” for

all population groups.

AEGU M EST

I. The conduct o f defendant hospitals in discriminating

against Negro patients is State action

A. The controlling principles

From the declaration in the Civil Bights Cases, 109

U.S. 3, 11 (1883), that the Fourteenth Amendment

“ nullifies and makes void * * * State action of every

kind, which * * * denies * * * the equal protection

of the laws” to the Supreme Court’s pronouncement

7 The “ Non-Discrimination Report” submitted by the North

Carolina Medical Care Commission on January 3, 1962 was

approved by the Surgeon General on January 22, 1962 (120a).

16

in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 IJ.S. 1, 19 (1958), that state

participation ‘ ‘ through any arrangement, management,

funds or property” is sufficient to make racial dis

crimination in such circumstances violative of the

Fourteenth Amendment, it has been clear that the

mere outward trappings of private activity are not

sufficient to insulate an activity from the commands

of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. Racially

discriminatory acts of individuals are so insulated

only insofar as they are “ unsupported by State

authority in the shape of laws, customs, or judicial

or executive proceedings*” or are “ not sanctioned in

some way by the State.” \Qivil Rights Cases, supra

at 17. Where racial discrimination is accompanied

by some form of governmental support, the appli

cability of the F ifth8 and Fourteenth Amendment is

clear.9 \.

Only recently, the Supreme Court had, before it the

problem of determining whether a State had become

so involved in private conduct as to make the action of

private individuals subject to the Fourteenth Amend

ment. In holding that a private restaurant operating

in a public building under a lease from a public au

thority could not engage in racial discrimination, the

8 Cf. Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 IJ.S. 497 (1954).

9 The interrelationship between governmental and private

activity was aptly described by Chief Justice Vinson in Ameri

can Communications Ass'n v. Douds, 339 IJ.S. 382, 401 (1950)

where he wrote: “ * * * when authority derives in part from

Government’s thumb on the scales, the exercise o f that power

by private persons becomes closely akin, in some respects, to

its exercise by Government itself.”

17

Court noted (Burton v. Wilmington Parking Au

thority, 365 U.S. 715, 722, 725 (1 9 6 1 )):10

Only by sifting facts and weighing circum

stances can the nonobvious involvement of the

State in private conduct be attributed its true

significance.

* * * *

But no State may effectively abdicate its re

sponsibilities by either ignoring them or by

merely failing to discharge them whatever the

motive may be. It is of no consolation to an in

dividual denied the equal protection of the laws

that it was done in good faith . . . By its in

action, the Authority, and through it the State,

has not only made itself a party to the refusal

of service, but has elected to place its power,

10 Even before Burton there was a large body of case law

which proscribed discrimination by a lessee of public property

or facilities. See Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Associa

tion, 347 U.S. 971 (1954), vacating ancl remanding, 202 F. 2d

275 (C.A. 6, 1953) (leased open air theater); Aaron v. Cooper,

261 F. 2d 97 (C.A. 8, 1958) (leased school); City of Greens-

boro v. iSimpkin-s, 246 F. 2d 425 (C.A. 4, 1957), affirming, 149

F. Supp. 562 (M.D.N.C. 1957) (leased cafeteria); Coke v.

City of Atlanta, 184 F. Supp. 579 (N.D. Ga. 1960) (leased air

port restaurant), Jones v. Marva Theatres, 180 F. Supp. 49 (D.

Md. 1960) (leased motion picture theatre); Tate v. Department

of Conservation, 133 F. Supp. 53 (E.D. Va. 1955), affirmed, 231

F. 2d 615 (C.A. 4, 1956), cert, denied, 352 U.S. 838 (1956)

(leased beach) ; Nash v. A ir Terminal /Services, 85 F. Supp.

545 (E.D. Va. 1949) (leased airport restaurant) ; Lawrence v.

Hancock, 76 F. Supp. 1004 (S.D. W . Va. 1948) (leased swim

ming pool). Although these decisions are rested on various

grounds—in some, that the lease was a technique of evading

state responsibility; in others, that the property, though pri

vately operated, was being used for a public purpose—they

have been uniform in reaching the conclusion that the discrim

ination effectuated by the private lessee was constitutionally

forbidden.

18

property and prestige, behind the admitted dis

crimination. [Emphasis added.] 11

Relying primarily upon the Burton decision, plain

tiffs argument that the totality of governmental involve

ment, in the activities of the defendant hospitals is

such as to make applicable the prohibitions of the

Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments.12 While we sup

port this argument, we will not develop it in this

brief. Rather, wo will demonstrate here that it is

because of the relationship of the defendant hospitals

to the Hill-Burton system that their admission policies

must be deemed “ state action.” Our position is based

on the fact that the Hill-Burton system contemplates

a State obligation to plan for facilities to provide

adequate hospital service to all the people of the

11 The concurring and dissenting opinions provided even

broader tests of governmental responsibility. Justice Stewart,

concurring, stated that legislative enactments “ authorizing dis

criminatory classification based exclusively on color * * * is

clearly violative o f the Fourteenth Amendment.” [Emphasis

added.] (365 U.S. at 726-27.) Justice Frankfurter, dissenting,

commented: “For a State to place its authority behind discrimi

natory treatment based solely on color is indubitably a denial by

a State of the equal protection o f the laws, in violation o f the

Fourteenth Amendment” (365 U.S. at 727). Dissenting Jus

tices Harlan and Whittaker also indicated that they “ would

certainly agree” with Mr. Justice Stewart’s formulation (365

U.S. at 729).

12 In support of this argument, plaintiffs rely on the follow

ing aspects o f governmental involvement: (a) financial support;

(b) licensing; (c) tax exemption; (d) the composition of the

Board of Trustees of the Cone Hospital; (e) the participation

o f the Cone Hospital in a program of nurses’ training in coop

eration with tax-supported state institutions of higher learning

and (f) the role of defendant hospitals, under the Hill-Burton

Act, as integral components o f a federal-state system o f hospital

care.

19

State. To the extent that this obligation is carried

out by otherwise private institutions, these recipients

of the federal grants are acting for the State and

are therefore subject, in this respect, to the obliga

tions imposed upon State agents and instrumentalities

by the Fourteenth Amendment.

At the outset, however, it is important to stress

what we are not contending. We do not argue that

purely private activities are governed by the standard

established by the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments.

The Civil Bights Cases, supra, have established that

an otherwise private institution is not subject to the

nondiscrimination provisions of the Constitution

merely because, unlike a home for example, it is gen

erally open to the public. We do not attack that rule.

Nor do we urge that the receipt of government finan

cial aid is sufficient, without more, to deprive an

otherwise private institution of its non-governmental

character. Under circumstances different from those

present in this case, many colleges, universities, re

search institutions, and hospitals enjoy such financial

aid without becoming subject to the constitutional

obligations resting on the federal and State govern

ments. As we shall demonstrate, however, this case

involves something more, in the way of governmental

involvement, than the grant of financial aid. While

the line between governmental and private action is

necessarily delicate, we submit that, on balance, the

governmental involvement under the Hill-Burton Act

is sueh that the participating hospitals cannot be re-

20

gardecl as exempt from the equal protection require

ment of the Constitution.

B. The hospitals are acting for the State and are subject to constitutional

limitations

1. The Hill-Burton Act requires that each partici

pating State set up a comprehensive plan of hospital

care for the benefit of all of the people of the State.

It was Congress’ intention that the participating

States plan for facilities to provide adequate

hospital service to “ all the people” of the State

(sections 291(a) and 291e(f)), and each partici

pating State is required to make an undertaking

to that effect. Any State which has assumed this, ob

ligation is therefore responsible, under the scheme of

the Hill-Burton Act, to design a plan assuring that

“ all the people” of that State are provided adequate

hospital services. The means used. for carrying out

this obligation may vary; the State may employ the

services of governmental hospitals or non-profit hospi

tals. But, to repeat, the obligation is the State’s, .and

if, for example, the number of beds in non-profit hos

pitals appear to lie inadequate to meet the needs, the

State would undoubtedly have to plan for beds in

governmental institutions to have a program meeting

the requirements of the law. Accordingly, when, the

State draws a non-State institution into the State plan,

the latter performs one of the State’s acknowledged

functions. It follows that such a non-governmental

institution becomes pro tanto a State instrumentality

with concomitant obligations, . . v. . .

21

2. Congress enacted the Hill-Burton Act to meet

vital national needs. As the report of the Senate Com

mittee on Education and Labor on the Act noted: 13

Your committee has given careful considera

tion to the national need for hospital facilities

as shown by the testimony of a large number of

well-informed witnesses from many walks of

life. It has been pointed out that our national

health rests upon four main pillars—medical

research, preventive medicine, medical care, and

hospitalization. This bill is designed to

strengthen all four through the provision of

more adequate hospital facilities. Lack of

hospital facilities—properly placed and ade

quately equipped—represents one of the weak

est spots in our national health structure.

42 U.S.C. 291(a) declares that the basic and over

riding purpose of the Act is to assist the several States

in the development of programs for hospital construc

tion that will afford the necessary facilities “ for

furnishing adequate hospital, clinic and similar serv

ices to all their people.” 14 Accordingly, Section

291e(f) similarly provides that the Surgeon General

shall adopt regulations making it mandatory that the

State plan of hospital construction provide “ for

13 Senate Report No. 674, 79th Congress, 1st Sess., p. 2-3.

14 This broad declaration of Congressional policy (42 U.S.C.

291(a) ) is carried forward into the survey and planning pro

visions (42 U.S.C. 291b(a) (3), o f which North Carolina took

advantage, and thence into the State plan for construction (42

U.S.C. 291f (a) (4) (C ».

677083— 63- -4

22

adequate hospital facilities for the people residing in

a State * * *” 15

Senator Hill, in describing the purpose of his bill,

quite correctly described the ultimate result when he

said that it was intended to assist the States in pre

paring “ a State-wide program for new construction so

that all people of the State may have adequate health

and hospital services.” 16

This emphasis on the creation of a State-wide

system of hospitals for the provision of hospital serv

ice to all of the people of the State indicates that the

Hill-Burton program was not limited to the granting

of financial aid to individual hospitals. It shows,

rather, a congressional design to induce the States,

upon joining the program, to undertake the super

vision of the construction and maintenance of ade

quate hospital facilities throughout their territory.

Upon joining- the program a participating State in

effect assumes, as a State function, the obligation of

15 Section 291e(f) also stipulates that State plans shall make

provision for hospital admissions without discrimination on

account of race, color, or creed. We discuss the full significance

o f this provision in a subsequent part, o f this brief. Suffice it

to say here that the requirement o f non-discrimination is an

indication that Congress felt that what was involved was' a

governmental responsibility, or it would not have imposed upon

the States (and authorized the Surgeon General to impose,

through them, on all participating hospitals) a constitutional

non-discrimination obligation binding only upon governmental

entities. ’ h h - , q' o :

16 Hearings , before Senate; . Committee . on Education and

Labor on S. 191, 79th Cong., 1st Sess., p. 8 .,

23

planning for adequate hospital care. And it is, of

course, clear that when a State function or responsi

bility is being exercised, it matters not for Fourteenth

Amendment purposes that the agent or instrumental

ity would otherwise be private: the equal protection

guarantee applies. Marsh v. Alabama, 326 TT.S. 501

(1946) ; Nixon v. Condon, 286 U.S. 73 (1932) ; Smith v.

Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944) ; Terry v. Adams, 345

U.S. 461 (1953).

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454 (1960), even

though not reaching any constitutional issue, is' an

analogy on this point. There the bus carrier had vol

unteered to make terminal and restaurant facilities

available to its passengers. Here the State has volun

teered to set up a hospital system that makes hospital

services available to all its people. There the terminal

and restaurant had cooperated in the undertaking.

Here the defendant hospitals have cooperated in the

hospital system. The Court held that under these cir

cumstances the terminal and restaurant were bound

by the same federal obligations as was the bus carrier

and said (364 U.S. at 460-461) : “ * * * if the bus car

rier has volunteered to make terminal and restaurant

facilities available to its interstate passengers as a

regular part of their transportation, and the terminal

and restaurant have acquiesced and cooperated in this

undertaking, the terminal and restaurant must per

form these services without discrimination prohibited

by the Act. In the performance of these services

under such conditions the terminal and restaurant

24

stand in the place of the bus company in the perform

ance of its transportation obligations.” So here, the

defendant hospitals stand in the place of the State in

the performance of its Constitutional obligations.

3. There are other indications in the statute that

hospitals which participate in the Hill-Burton pro

gram have asserted to perform a governmental func

tion. The very comprehensiveness of the program

points in this direction. So does the fact that Con

gress has placed the federal-state program of hospital

care under the detailed supervision and administra

tion of governmental bodies. Senator Hill, in ex

plaining how the program would operate, made clear

the total involvement of government. He said (91

Cong. Rec. 11716) :

The provision in the bill requiring each state

to formulate and have approved by the surgeon

general a State plan based upon a State-wide

inventory of existing hospitals and a survey of

needs, and the requirement that each applica

tion for funds must be in conformity with the

State plan and be approved by the State agency

administering it, will greatly stimulate and

help to bring about an integrated system of

health and hospital facilities within each state.

The over-all standards and general regulations

issued by the Surgeon General of the Public

Health Service, together with his expert advice

and help, will bring about a more uniform and

integrated national system of hospital and

health facilities.

25

In other words, the Hill-Burton program was de

signed to encourage the creation of a state-wide sys

tem of hospital service. The adoption of a plan for

such a system was required by Congress as a condition

to receiving aid. And the Surgeon-General is given

extensive supervisory control over the plan and its

operation.

Under the Act, the Surgeon General is granted

rule-making power over the methods of administra

tion of the plan and the standards of construction and

equipment for hospitals. He also regulates the

manner in which the State agency administering the

plan determines the priority of projects to receive

federal funds and sets standards for determining the

number of hospital beds necessary to provide ade

quate hospital services to people residing in the State.

Pursuant to this authority, the Surgeon General has

promulgated regulations which must be adhered to by

the State agency administering the plan and by all

applicants for aid. These regulations—42 C JAR.

53—are extremely detailed and cover such matters as

the distribution of diagnostic and treatment centers

and equipment.17

17 The regulations prescribe a multitude o f requirements that

an applicant must meet to be approved by the State agency for

participation in the State plan. For example, in approving

any application the State agency is required by regulation (42

C.F.R. 53.127(d)) to certify that the application contains

reasonable assurances as to title, payment o f prevailing rates

of wages, and financial support for the construction arid opera

tion o f ; the project; that the plans and specifications for con

struction - o f the project1 are in accord with the minimum

construction standards in the Federal regulations; that the

application contains-an assurance that the applicant will con

26

The recent Public Works Acceleration Act of 1962,

76 Stat. 542, 42 C.S.C. 2641-2643-—provides an indi

cation of the status of Hill-Burton hospitals. The

purpose of the 1962 Act is to accelerate public work

projects in order to combat unemployment. In sec

tion 2641 of the Act, Congress declared that “ The

Nation has a backlog of needed public projects, and

an acceleration of these projects now will not only

increase employment at a time when jobs are urgently

required but will also meet long-standing public needs,

improve community services, and enhance the health

and welfare of citizens of the Nation.” To carry

out this purpose, the President is “ authorized to initi

ate and accelerate in eligible areas those Federal

public works projects which have been authorized by

Congress, and those public works projects of States

and local governments for which Federal financial

assistance is authorized under provisions of law other

than this chapter. * * *” (42 U.S.C. 2642(b).)

Significantly, Congress considered that assistance to

nonprofit hospitals would be an appropriate public

works project. Thus, H.R. No. 1756, 87th Cong. 2d

Sess., p. 17, states: “ Hospitals represent another

area of pressing public need on which activity could

be begun promptly. The assistance in this bill, which

form to the requirements of sections 53.111, 53.112, and 53.113

o f the regulations regarding the provision of facilities for

persons unable to pay therefor; that the application contains

an assurance that the applicant will conform to State standards

for operation and maintenance and to all applicable State laws

and State and local regulations; that the application is en

titled to priority over other projects within the State; and that

the State agency has approved the application.

27

could be used for both public and private nonprofit

hospitals, would be particularly helpful in meeting

the urgent need for modernization of older hospitals.”

See also Cong. Rec., August 28, 1962, p. 16856.

4. In appraising the effect of the Hill-Burton Act,

it is important to remember the context of the statute.

A very substantial proportion of the country’s hospi

tals are unquestionably public, albeit non-governmen

tal, institutions.18

As the memorandum of the General Counsel of the

Department of Health, Education, and Welfare

(175a) reveals, non-profit hospitals have a decidedly

public character. Indeed, governmental hospitals

“ differ little from private non-profit hospitals except

in the manner of selection of the governing boards,

and sometimes in having a cal] upon tax funds to meet

deficits” (176a). Both governmental and non-profit

hospitals serve as general community hospitals. Such

“ community hospitals have become essential, both to

provide hospital service to the people of the commu

nity and to enable its physicians to practice good

medicine” (179a). In addition, all hospitals have very

substantial governmental contacts. The record in this

case demonstrates the detailed licensing and regula

tion to which hospitals are subjected. Moreover, hos

pitals have long been dependent upon public support

in the form of tax exemptions as well as substantial

grants.

These circumstances seem significant in determining

18 In 1960, there were 524 accredited governmental hospitals,

2,276 accredited private non-profit hospitals and 154 proprie

tary (profit-making) accredited hospitals (175a).

28

whether it is likely that through the Hill-Burton Act,

Congress has in fact established a program which uses

the participating non-profit hospitals as government

instrumentalities for the limited purpose of meeting

the community’s need for hospital services. The pro

portion of hospitals which were State, county or mu

nicipal institutions, the degree of public interest, the

dependence upon tax exemptions, the existing systems

of licensing and regulations, all show that the pro

gram as we conceive it involves no drastic change in

institutions except in race relations where the change

is impelled by the Constitution. Cf. Garner v. Loui

siana, 368 U.S. 157, 183 (1961) (Mr. Justice Douglas

concurring).

5. To be sure, there are provisions in the Act which

show that Congress did not intend under the Hill-

Burton program to require state control of partici

pating non-profit hospitals in all their functions.

Thus, a number of provisions of the Act use the words

“non-profit” in contra-distinction to the adjective

“public” in describing the types of hospitals to be as

sisted.19 We do not believe, however, that the use of

such terms—which merely describe the nature of the

ownership of the recipients of federal assistance-

overrides the legal import of a federal-state program

specificially designed to furnish hospital services to

all the people. For example, under our view of this

case, the Cone Hospital will continue to be a non-profit

hospital in the sense that its present Board of Trus

tees, and not the State, will be responsible for its

management. Only with respect to the admission to

19See, e.g., 42 U.S.C. 291(a), 291d, 291h(a), 291n.

29

hospital services will the hospital be considered a

governmental instrumentality required to adhere to

the commands of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Other provisions of the Act, and portions of the

legislative history, do suggest that the statute was in

tended to establish simply a program of grants-in-

aid.20 I f these stood alone, a different question would

20 See, e.g., the following:

(a) 42 U.S.C. 291m (60 Stat. 1049), entitled “ State control of

operations” which provides: “ Except as otherwise specifically

provided, nothing in this subchapter shall be construed as con

ferring on any Federal officer or employee the right to exercise

any supervision or control over the administration, personnel,

maintenance, or operation o f any hospital, diagnostic or treat

ment center, rehabilitation facility, or nursing home with respect

to which any funds have been or may be expended under this

subchapter” (emphasis added). [While the title “ State con

trol of operations” is used in the Statutes at Large, the United

States Code uses the phrase “ State control of agencies.” ]

(b) The House Committee Report (H. Rep. No. 2519, 79t,h

Cong., p. 8) states that regulations under 42 U.S.C. 291e(f)

will “ relate solely to administration o f the plan submitted by

the State agency and do not in any way relate to the admin

istration of hospitals.”

(c) Senator Hill stated: “ The bill does not provide a Federal

program of hospital construction. It does provide a program

of Federal aid to the states and their localities for hospital

construction.” 91 Cong. Rec. 11714.

(d) Senate Report No. 674, 79th Cong. 1st Sess. p. 7, states:

“ The bill is not a Federal hospital construction bill. The

need for a country-wide program of hospital construction has

been demonstrated. It remained for the committee to consider

and determine the relationship that should exist between the

Federal Government and the States in planning and carrying

out such a program. The committee believes that a Federal-aid

program of the character set forth in the reported bill, which

will supplement State and local funds for planning and carry

ing out a construction program, but will at the same time

encourage the States to assume the responsibility for carrying

30

be presented. We believe, however, that these pro

visions should be read as expressing Congress’ intent

not to put the federal government into the business of

directly administering hospitals. The Hill-Burton

program was meant to provide a federal stage on

which the states and the hospitals designated to par

ticipate in the State system would be the principal

actors. Congress was intent on establishing an elabo

rate framework to make possible the rendition of

hospital services to all the people but it was not Con

gress’ intent to impose on the federal government the

obligation of constructing on that framework. That

this is so is clearly illustrated by 42 U.S.C. 291m (60

Stat. 1049) which, although it disavows federal super

vision or control over assisted hospitals, makes clear

in its title—“ State control of operations”■—that there

shall be control, but by the States.21

Finally, the argument that the Hill-Burton Act

establishes only a program of construction grants is

inconsistent with the clear language of 42 IT.S.C.

291e(f). That argument necessarily treats 291e(f)

as doing no more than assuring an equitable distribu

tion of the money so that proportionate shares will

out the program to the greatest possible extent consistent with

a proper check upon expenditure of Federal appropriations,

will be most effective in a long-range hospital-construction

program.”

21 It is significant that the disavowal o f federal administrative

control applies equally to the “private” non-profit hospitals and

to those admittedly “ public.” Moreover, Section 291m is intro

duced by the phrase “ Except as otherwise specifically pro

vided * * *” As we have indicated, 42 U.S.C. 291(a) and

291e(f) demonstrate a Congressional intention to make it a

matter o f federal concern as to whom hospital services are

provided.

31

reach the institutions serving whites, Negroes and

other segregated groups, and that Congress was not

concerned with the actual provision of hospital serv

ices to the needy or with discrimination in the rendi

tion of services. But this argument is invalid. Sec

tion 291e(f) shows on its face that Congress was

concerned not merely with the distribution of the

money but with what is done with the new hospital

facilities in the continuing rendition of hospital serv

ices. Far from being content to leave this to private

decision, Congress imposed upon the States, and au

thorized the Surgeon General to require them to

impose on the hospitals, the twin obligations of

aiding the needy and avoiding unconstitutional

discrimination.

Section 291e(f), therefore, cannot be explained

away as only an effort to see that money is equi

tably distributed, with the governmental responsibility

stopping at that point. We think that, in conjunction

with the other considerations noted, it is sufficient evi

dence that Congress did regard the availability of hos

pital services as a State responsibility to be met

either through hospitals run by governmental agen

cies or by non-profit organizations on behalf of the

State, although managed by private citizens.

But even if the opposing evidence be thought

stronger with respect to the overall character of the

non-profit hospitals, we submit that Congress unques

tionably undertook to deal, and to require the States

to deal through the hospitals, with the problem o f dis

crimination on grounds of race, creed or color. Hav

32

ing taken this step neither ' government could,

consistently with the Fourteenth Amendment, do less

than the Amendment requires; and, at least in that

respect, the hospitals must he acting as the instru

ments of the State and bound by the same limitation.

C. The non-discrimination provision of the Hill-Burton Act

1. We have argued above that hospitals voluntarily

participating in the Hill-Burton system are govern

mental instrumentalities for the purpose of providing-

hospital care to all the people. This argument is based

on our analysis of the Hill-Burton Act, particularly

sections 291(a) and 291e(f), and its legislative history

which, we believe, demonstrates that Congress in

tended through the Act to promote hospital services

for all the people.

As an alternative to the above argument, we now

contend that the hospitals, even if otherwise private,

are acting for the government in using the grants to

provide hospital facilities without unconstitutional

discrimination. It is clear that under the Hill-Burton

program, the admission policies of participating hos

pitals are made a matter of federal and State concern.

This is not a subject on which the federal statute is

silent ; it is not a subject over which the State agencies

have no responsibility. Rather, under the statute, the

Surgeon Greneral is required to participate in and

direct the implementation of the congressional policy

that Hill-Burton hospital be for the use of all the peo

ple on an “ equitable” basis. By imposing this

33

duty on State agencies and the Surgeon General,

Congress has made the public availability of Hill-

Burton facilities a subject of governmental concern

and control. Here, then, the statute providing for a

hospital program and financial assistance directly

and positively concerns itself with the admission

policies of those to receive the assistance. Whether

in the absence of this governmental supervision and

control racially restrictive admission policies of Hill-

Burton hospitals would otherwise be purely “ private

action7’ and subject to no constitutional strictures need

not be considered. Congress has removed the racial

admission policies of Hill-Burton hospitals from the

realm of private action. Congress has regulated and

has authorized the Surgeon General to regulate those

policies in the national interest. It has further pro

vided that the several States regulate those policies

and give binding assurances as to the nature of those

policies. And the final performance of the continuing

obligation, which the government accepted and im

posed upon the States, falls on the hospital in render

ing services. At least to this extent, the Act

contemplates that the hospitals are to act as, and for,

the State. What a hospital does with respect to race,

creed or color must therefore conform to the Four

teenth Amendment.

The essential point is that, even in the case of

otherwise private hospitals, Congress was unwilling

to leave the avoidance of unconstitutional dis

crimination to free private decision. Congress per

ceived, and forced the States (and also the hos

34

pitals choosing to participate in the program) to

accept a governmental obligation. In effect, it im

pressed a trust for these two purposes upon the money

and any facilities into which the funds are converted.

Anyone taking the money would take it, as it were,

subject to the trust, and in performing the trust the

taker would be acting for the government and subject,

in this respect, to its constitutional obligations.22 Con

sequently, it may fairly be said that the admission

policies of Hill-Burton hospitals are sanctioned by

force of law; for these policies are formulated and

carried out with government assistance and pursuant

to statutory authorization and governmental direction.

a. Legal precedent supports our position. It is now

clear that State laws requiring racial discrimination

by private businesses or individuals are unconstitu

tional. Hot only are the laws themselves unconstitu

tional, but the conduct which the law compels of the.

private individuals is itself unconstitutional even

though, absent the law, it would be permissible as

“ private action” . As indicated, supra, as early as the

Civil Rights Cases, 109 TT.S. 3, 17 (1883) the Supreme

Court made clear that discriminatory acts of private

22 Our view that federal funds contributed under the Hill-

Burton program are impressed with a trust is supported by

42 U.S.C. 291h(e) which provides that i f a hospital is sold

or transferred to a person or agency not qualified to file an

application under the Act or ceases to be a “non-profit hos

pital” , the United States may recover a proportionate share

of the then value as its contribution was to the cost o f the

project. This provision suggests that the Federal Government

has a continuing interest in the recipients of its aid.

35

persons are insulated from the Fourteenth Amend

ment only insofar as they are “ unsupported by State

authority in the shape of laws, customs, or judicial or

executive proceedings,” or are “ not sanctioned in some

way by the State. ’ ’ More recently, courts have found

that where private persons segregate pursuant to posi

tive provisions of the law, the actions of the private

persons are within the ambit of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. In Boman v. Birmingham Transit Company,

280 F. 2d 531 (C.A. 5, 1960) a city ordinance per

mitted passenger carriers to make rules for the seating

of passengers. The Court of Appeals held that the

action of the bus company in promulgating and en

forcing the rules was “ state action” and said (280 F.

2d at 535) :

Of course, the simple company rule that Ne

gro passengers must sit in back and white pas

sengers must sit in front, while an unnecessary

affront to a large group of its patrons, would

not effect a denial of constitutional rights if not

enforced by force or by threat of arrest and

criminal action. Where, as here, the City dele

gated to its franchise holder the power to make

rules for seating of passengers and made the

violation of such rules criminal, no matter how

peaceful, quiet or rightful (as the court here

held), such violation was, we conclude that the

Bus Company to that extent became an agent of

the State and its actions in promulgating and

enforcing the rule constituted a denial of the

plaintiffs’ constitutional rights.

See also Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750, 755-56

(C.A. 5, 1961) ; Flemming v. South Carolina Electric

36

and Gas Company, 224 F. 2d 752 (C.A. 4, 1955), ap

peal dismissed, 351 U.S. 901.

A similar conclusion was reached by Judges

Bazelon and Edgerton in Williams v. Hot Shoppes,

Inc., 293 F. 2d 835 (C.A.D.C. 1961).23 They said

(293 F. 2d at 846) :

When otherwise private persons or institu

tions are required by law to enforce the

declared policy of the state against others, their

enforcement of that policy is state action no

less than would be enforcement of that policy

by a uniformed officer. Baldwin v. Morgan,

5 Cir., 1958, 251 F. 2d 780 ■ Flemming v. South

Carolina Electric & Gas Co., 4 Cir., 1955, 224

F. 2d 752, appeal dismissed, 1956, 351 U.S. 901,

76 S. Ct. 692, 100 L Ed. 1439. “ The pith of

the matter is simply this, that when [private

groups] * * * are invested with an authority

independent of the will of the association in

whose name they undertake to speak, they

become to that extent the organs of the state

itself, the repositories of official power.” Mxon

v. Condon, supra at page 88.

b. It is true that the above cases deal with laws

which required racial discrimination or which enforced

private discrimination by criminal sanctions. It is

equally true, however, that statutes authorizing or

permitting racial segregation run just as afoul of

the equal protection clause as statutes compelling

segregation.

23 Although. Judges Bazelon and Edgerton were dissenting,

they were the only members o f the couil; to consider the ques

tion. The majority of the court, relying on the equitable

abstention doctrine, did not reach the merits.

37

Almost fifty years ago, the Supreme Court consid

ered this question in McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka and

Santa Fe By. Co., 235 U.S. 151 (1911). There the

State of Oklahoma had enacted a. statute requiring

railroads to provide separate-but-equal facilities for

their intrastate passengers. Had the legislature

stopped at that point its effort would, of course,

have been within the Constitution under the then pre

vailing doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537

(1896). The State legislature, however, went further

and, having imposed the equality of treatment for

mula which was then recognized by the courts as valid,

went on to provide that the railroads need not follow

that formula with respect to sleeping, dining and chair

cars—so-called luxury facilities. Several Negroes

sued to enjoin enforcement of that statute. The Dis

trict Court determined that the statutory proviso with

respect to the luxury facilities did not offend the

equal protection clause. The Court of Appeals

affirmed. The Supreme Court, in an opinion written

by Justice Hughes, overruled the lower courts on this

point. While the Court did not dispute the principle

that the State could, by remaining silent, have left the

railroads to discriminate on the basis of race, it held

that if the passenger “ is denied by a common carrier,

acting in the matter under the authority of a state

law, a facility or conveyance in the course of his jour

ney which under substantially the same circum

stances is furnished to another traveler, he may prop

erly complain that his constitutional privilege has

38

been invaded” (235 U.S. at 162). [Emphasis

added.] 24

Here, as in McCabe, government has inserted itself

into an activity that might otherwise be regarded as

“ private” in order to set a standard of non-discrimi

nation for the benefit of the entire public. Congress

has chosen to inject the force of federal law into the

area of hospital admissions. It need not have done

that. It could have provided that funds be granted

free of conditions relating to admission. But Con

gress has chosen to concern itself with the admission

practices of participants in the Hill-Burton program

and expressly has authorized and sanctioned discrimi

nation. Here also, as in McCabe, the legislative au

thority has been exercised to allow discrimination of

the type which the courts have ruled cannot be in

dulged in by the governmental authority itself. This

authorization is unconstitutional and the admission

policies of defendant hospitals, as an exjjress subject

of Congressional regulation, are required to conform

to the commands of the Fifth and Fourteenth

Amendments.

2. It may be objected, however, that the only obli

gation Congress perceived is to see that proportion

ately equal, although separate, hospital facilities are

available to whites and Negroes and other groups.

One answer is that Congress obviously believed

that the major obligation, declared by the first sen

24 The principle of McCabe recently was endorsed by the

Supreme Court in Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority

365 U.S. 715 (1961). There the court. again made clear that

racial discrimination under the authority o f State law was pro

scribed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

39

tence of 42 IT.S.C. 291e(f), was to avoid discrimina

tion and comply with constitutional standards in the

provision of hospital services. It believed that sepa

rate but equal facilities would meet the obligation and

it was therefore willing to accept such facilities as an

exception to the general rule. This assumption was

a mistake. Even though the government might have

left the selection of patients entirely to the hospitals,

it could not constitutionally put an imprimatur of

government approval upon segregation. Taking the

statute as it was enacted, without speculating about

political probabilities, it seems fair to say that the

avoidance of unconstitutional discrimination was the

dominant aim of 42 IT.S.C. 291e(f) and that since a

choice must be made between invalidating the whole

or excising the unconstitutional portion, the subor

dinate exception must be excised, leaving the domi

nant undertaking intact.

A second answer is that once Congress undertook to

eliminate discrimination in the availability of hospital

facilities, it could use no standard other than that

found in the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments.

Congress could not license part performance of a

constitutional duty.

In short, it can be conceded that a government—

whether State or federal—can give away money or

grant property and leave the recipient free to dis

criminate or not discriminate, on the basis of race, in

the use of the property. Where, however, the gov

ernment exercises control to assure that the money or

property is used for the benefit of all the people, the

standards set by the government, and the conduct of

40

recipients of aid acting under those standards, must

conform to the Constitution.

II. The provision o f the Hill-Burton Act sanctioning the

construction o f separate-but-equal hospital facilities is