Ayers v. Fordice Brief and Opinion

Public Court Documents

April 23, 1997

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ayers v. Fordice Brief and Opinion, 1997. 33183e85-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4ca66f23-75cc-475c-bfdf-cf9455844968/ayers-v-fordice-brief-and-opinion. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

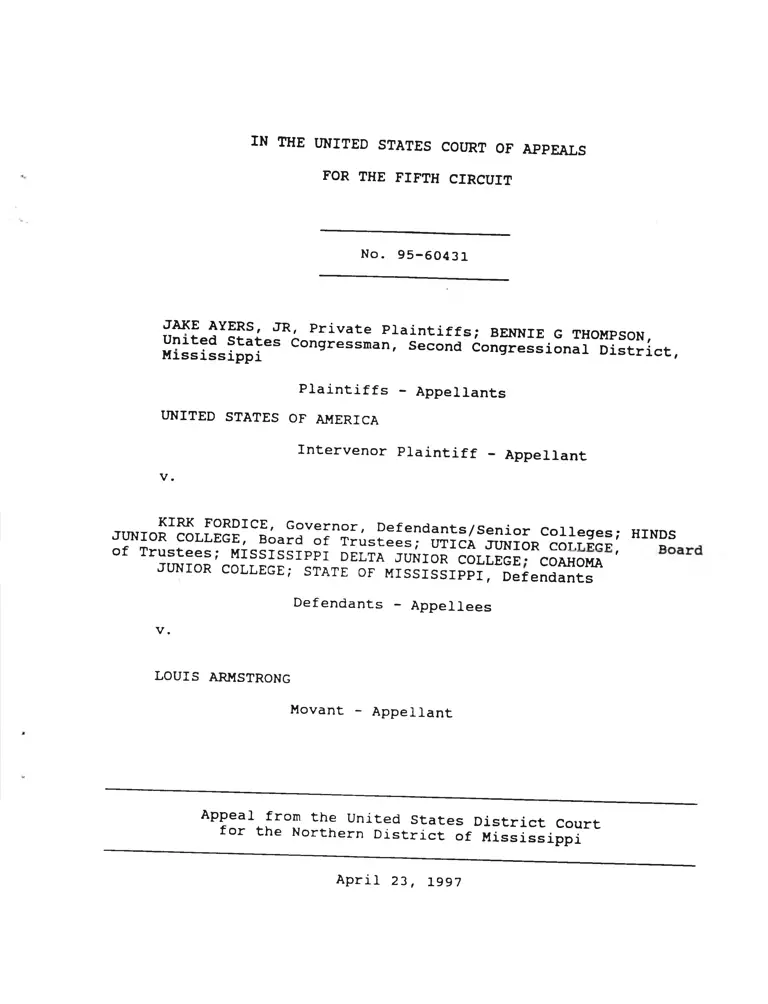

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 95-60431

JAKE AYERS, JR, Private Plaintiffs

United States Congressman, Second Mississippi

; BENNIE G THOMPSON,

Congressional District /

Plaintiffs - Appellants

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Intervenor Plaintiff - Appellant

v.

JUNIO^Tf???1^' G°ve^nor' Defendants/Senior Colleges; HINDS UNIOR COLLEGE, Board of Trustees; UTICA JUNIOR COLTFCF n

of Trustees; MISSISSIPPI DELTA JUNIOR COLLEGE? COAHOMA '

JUNIOR COLLEGE; STATE OF MISSISSIPPI, Defendants^

Defendants - Appellees

v.

LOUIS ARMSTRONG

Movant - Appellant

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Mississippi

April 23, 1997

TABLE OF CONTT-iUTg

I.

II.

III.

BACKGROUND ................

STANDARD OF REVIEW ..........

DISCUSSION ................

A* Missions Policies and Practippg............

!• Background Facts ............

2* Undergraduate Admissions Standar-Hc . . . .

. 4

10

12

12

12

15

3.

a. District court ruling........

b. Arguments on appeal ........ „c. Analysis............ * .......... 22

i. Rejection of plaintiffs' proposals ’ 28ii. Reliance on spring screening and

summer remedial program .......... 32

iii. Elimination of existing remedialcourses ........

iv. Timing........ ’ ’ * * ^ 4

d. Conclusions regarding undergraduate admissions standards

3- Scholarship Policies * * * • • • • • • • 39

a. District court ruling . . . .

c. Arguments on appeal . ........ Anc. Analysis..........* .....................

d. Conclusions regarding scholarship 42policies . . . * * " * • • • • • 52

Enhancement of Historically Black instit,n-i . 53

1• Background Facts . ............................ 53

2* New Academic Programs ...................... 54

a. District court ruling ............... R

b. Arguments on appeal . *c. Analysis.......... * .............. ...

d. Conclusions regarding new academic* 61programs ..............* * * .......... 67

3 * Land_Grant P r o a r a m g ............................... 68

a. District court ruling . . . .

b. Arguments on appeal . ..........c. Analysis............* * ..............7 0

2

d. Conclusions regarding land grant programs.......... . . y

4. Duplication of Programs . .

73

73

a. Fordice ........

b. District court ruling .

c. Arguments on appeal . .

d. Analysis ..............

e. Conclusions regarding program duplication ..............

73

74

79

80

83

5. Funding 83

a. District court ruling ............

b. Arguments on appeal ..............c. Analysis ....................

d. Conclusions regarding funding . . . . . .

Employment of Black Faculty and Administrators

D- System Governance ........ * • • • • • •

IV. CONCLUSION . . .

83

88

89

94

94

99

101

3

Before KING, JOLLY, and DENNIS, Circuit Judges.

KING, Circuit Judge:

This case concerns the obligation of the state of

Mississippi and the other defendants to dismantle the system of

~ iUre se9regation that was maintained in public universities in

Mississippi. After we heard the initial appeal of this case in

1990, the Supreme Court established, for the first time, the

standards for determining in the university context whether a

state has met its affirmative obligation to dismantle its prior

~ ***** system* We now review the district court’s ruling

following trial on remand to determine whether it erred in its

application of these standards.

For the reasons set forth below, we affirm in part, reverse

m part, and remand the case to the district court for further

proceedings consistent with this opinion.

I. background

Mississippi's system of public four-year universities was

formally segregated by race from its inception in 1848 through

1962, when the first black student was admitted to the University

of Mississippi by order of this court. See Meredith u v,,- 3 0 6

F.2d 3 7 4 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 3 7 1 U.S. 828 (1962). The

racial identiflability of Mississippi's eight public universities

changed little during the decade following the landmark admission

of James Meredith. The student composition of the University of

Mississippi, Mississippi state University, Mississippi University

4

for Women, University of Southern Mississippi, and Delta state

University (collectively, “historically white institutions” or

“HWIs”) remained almost entirely white, while that of Jackson

State University, Mississippi Valley State University, and Alcorn

State University (collectively, “historically black institutions”

or “HBIs”) remained almost entirely black. See Uryjted_States_vi_

Fordice, 505 U.S. 717, 722 (1992). The racial identifiability of

these institutions persists to the present. 1

Private plaintiffs initiated this class action2 in 1975,

complaining that Mississippi was maintaining a racially dual

system of higher education in violation of the Fifth, Ninth,

Thirteenth, and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States

Constitution, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and 1983, and Title VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000d to 2000d-7. The

United States intervened as plaintiff and alleged violations of

the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and Title

VI.

For twelve years the parties attempted to resolve their

differences through voluntary dismantlement of the prior

PnmiiJnf ̂ f®11. of 1993' the on-campus undergraduate*as,at least 75% white at each of the HWIs, and at least 93% black at each of the HBIs.

2 The class was certified by the court as:

blacJc citizens residing in Mississippi, whether students, former students, parents, employees, or

Wh° haVe been' are' or w i l 1 be discriminated against on account of race in . . . the universities operated by said Board of Trustees. diversities

Ayers v. Allain, 674 F. Supp. 1523, 1526 (N.D. Miss. 1987).

5

segregated system. Unable to achieve ultimate agreement, the

parties proceeded to trial in 1987. The district court ruled

that Mississippi had discharged its affirmative duty to dismantle

the former de jure segregated system of higher education through

its adoption and implementation of good-faith, race-neutral

policies and procedures in student admissions and other areas,

aners V. Mlflln, 674 F. Supp. 1523, 1564 (N.D. Miss. 1987) fAvers

I). Sitting en banc, this court affirmed. Avers v. » u ai. 9 1 4

F.2d 676 (5th cir. 1990). The United states Supreme Court

granted certiorari. Avers v. Mahns 4 9 9 U-S. 9 5 8 (1991)_

The Supreme court vacated the judgment and remanded for

further proceedings, holding that the mere adoption and

implementation of race-neutral policies was insufficient to

demonstrate complete abandonment of the racially dual system.

Eatdice, 505 u.s. at 731, 743. The Court stated that

even after a State dismantles its segregative

policies traceable Z° t h f S L S ^ y s i e m ' are' siin in

cconsistent with sound educational practices.

Id^ at 729. Applying this standard, the Court identified

admissions standards, program duplication, institutional mission

assignments, and continued operation of all eight public

universities as a nonexclusive list of “constitutionally suspect’

remnants of the prior de_jure system, “for even though such

policies may be race neutral on their face, they substantially

restrict a person's choice of which institution to enter, and

6

they contribute to the racial identifiability of the eight public

universities. Mississippi must justify these policies or

eliminate them.” Id,, at 733. The Court directed that these and

“each of the other policies now governing the State's university

system that have been challenged or that are challenged on

remand” be examined “in light of the standard that we articulate

today.” Id.

On remand, the district court ordered each party to submit

proposed remedies “to resolve the areas of the State's liability

pursuant to the Supreme Court mandate.” Without conceding

liability, defendant Board of Trustees of State Institutions of

Higher Learning (the “Board” ) 3 responded by presenting a

detailed proposal for modification of the higher education

system. This proposal contained, among other provisions, uniform

standards of admission for all universities, as well as a plan to

merge Delta State University and Mississippi Valley State

University into one institution to serve students in the

Mississippi Delta."

The private plaintiffs and the United States (collectively,

of fhl ^ iS resP°nsible for the management and controleight Publlc universities at issue in this case m t«CODE ANN. § 3 7-1 0 1 - 1 M 9Qfi\ Ti-c 7 unis case. MISS., , 7 1 (iyy6)- Its general powers and duties

innrt d ' alla> mana<?ing all university property disbursinafunds, establishing standards for admission and gradation and 9

supervise the functioning of eaoh institution.9 I S ifl! £ 3 7 -

c o u r t ^ n ' o c t ^ e t S r ^ r & S V u b ^ t e T i

and^ergerbplan^were^ontained

7

plaintiffs”) responded by insisting that the range of

constitutionally suspect policies and practices to be examined on

remand had yet to be determined. 5 Pursuant to a subsequent

court order, plaintiffs identified the following policies and

practices for examination: admissions standards that allegedly

deny black students equal access to higher education and tend to

channel black students to the HBIs; the use of ACT scores as a

basis for awarding undergraduate scholarships at the HWIs;

maintenance of institutional mission assignments that largely

follow historical racial designations; funding policies that

disproportionately benefit the HWIs; allocation of academic

programs that is unfavorable to the HBIs; allocation of land

grant programs between Alcorn state and Mississippi State that is

unfavorable to Alcorn; duplication of the HBIs' programs and

course offerings at the HWIs; maintenance of facilities at the

HBIS that are inferior to those at the HWIs; employment practices

that perpetuate the racial identiflability of the universities

and compensate faculty at the HBIs at a lower rate than faculty

at the HWIs; maintenance of all eight institutions; and practices

that limit the participation of black persons in system

governance. Trial commenced on May 9, 1994, following lengthy

attempts at settlement.

We

S S E t ^ * S T aS - e fi S l i ^ n n ^ 1 hend ^

8

court madeAfter ten weeks of testimony, the district

additional findings of fact and conclusions of law. The district

court found vestiges of de jure segregation in the areas of

undergraduate admissions, institutional mission assignments,

funding, equipment availability and library allocations, program

duplication, land grant programs, and number of universities.

Ayers v. Fordice, 879 F. Supp. 1419, 1477 (N.D. Miss. 1995)

(Ayers II).6 The district court entered a remedial decree on

March 7, 1995.7

The remedial decree enjoins defendants from maintaining

remnants of the prior system and engaging in practices impeding

desegregation. Specific relief includes adoption of the uniform

admissions standards proposed by the Board and allocation of

additional resources to Jackson State University and Alcorn State

University. The district court did not order implementation of

the Board's proposal to consolidate Delta State University and

Mississippi Valley state University. The decree establishes a

Monitoring Committee to monitor implementation of the terms and

obligations imposed by the decree. The Monitoring Committee is

to consist of three disinterested persons with experience in the

a , -

asp ? L T tive effects- Srisrsrsss M S M r

opi„iOT F S supp°rtat i % ^ 6entl„reetl U ”t the

th0Se “ »"*• tbe^remedialdecree p e ^ S n V S

9

field of higher education, agreed upon by the parties and

appointed by the court. The Monitoring Committee is to receive

and evaluate reports reguired of defendants and make

recommendations to the district court, which has retained

jurisdiction over the action. 8

Plaintiffs now contend that the district court left in place

practices that are traceable to the prior dual system and that

discriminatory effects and adopted reforms proposed by the

Board without examining the soundness or practicability of

alternative, less discriminatory proposals. Issues on appeal

encompass undergraduate admissions standards, scholarship

criteria, enhancement of historically black universities, system

governance, and employment. 8 No party appeals the district

court's rejection of the Board's consolidation proposal.

-L-L • ai'AW U AKD O F RFVTTTW

The standard set forth by the Supreme Court in Ford ice

guides our review of the district court's judgment. Ford ice

established that "a state does not discharge its constitutional

stayed appointment of”'the*l .Z 1996' the district court

reports ?egu?red to L »ade ?o al°ng "ith anycompletion of “the appellate process ” uI1s L C'>“ lttee' Pending

assumethattthettay ^ • ̂ c S S t S S T " w t « “

Committee will be activated%roSp£ly. ̂ that the Honltoring

broader some^respectt'thatlhif^/tH ar9UI”ent ™ appeal is

the two positions overlap considerablv^Wetot althoughwhere relevant. F aeraoiy. We note distinctions

10

obligations until it eradicates policies and practices traceable

to its prior de -jure dual system that continue to foster

segregation. 505 U.S. at 728. More specifically,

[i]f the State perpetuates policies and practices

traceable to its prior system that continue to have

segregative effects — whether by influencing student

enroiiment decisions or by fostering segregation in

other facets of the university system — and such

policies are without sound educational justification

and can be practicably eliminated, the State has not

S^prior system!^" °f Pr°Ving ^ At h*S dismantled

^ at 731. We have read Fordice to require that “each suspect

state policy or practice be analyzed to determine whether it is

traceable to the prior de jure system, whether it continues to

foster segregation, whether it lacks sound educational

justification, and whether its elimination is practicable.”

United States v. Louisiana, 9 F.3d 1159, 1164 (5th Cir. 1 9 9 3 ).

The State s liability depends upon these factors. id. 10

Once liability is found, the offending policies and

practices “must be reformed to the extent practicable and

consistent with sound educational practices.” Fordice. 505 U.S.

at 729. “[S]urely the State may not leave in place policies

rooted in its prior officially segregated system that serve to

maintain the racial identiflability of its universities if those

“liabUi?u”thlS stage in a desegregation case, a state'slabilitiy consists of its obligation to remedy remnants of a

sys^em for which constitutional liability has

“U;b?iitv”ninSt M llShed- ^ Ui5iana' we used the terT vestiaes of J J L ^ sense of an affirmative obligation to remedy

SnStint6 d° USe “^ ^ t y ^ i n thi^JeM^hw^^iSit^iS'th e''®understanding that the liability of the statP Af • •

* threSh°ld “ « « ■ =tems ' S ' S i t S .

11

policies can practicably be eliminated without eroding sound

educational policies." ^ at 743. Accordingly, we have

interpreted the directives of Fordice “as recognizing the need to

consider the practicability and soundness of educational

practices in determining remedies as well as in making an initial

determination of liability." Louisiana 9 F.3d at 1164.

We apply the directives of Eprdice in conjunction with

general standards of appellate review. This appeal challenges

elements of the district court's remedial decree and implicates

several of its findings and conclusions. We do not disturb the

district court's findings of fact unless they are clearly

erroneous, although we freely reassess its conclusions of law

under the de novo standard of review. Boss v, Honstnn

Sch. Dist. , 699 F. 2d 218, 226 (5th Cir lQR-n a ̂ ., tir. 1983). A third standard

applies to our review of the remedial decree itself. A

desegregation remedy is an exercise of a trial court's equitable

power and as such is reviewable, within the context of Fordice.

for abuse of discretion, fiU Valley v. B r i des Parish so, -a

702 F.2d 1221, 1225 (5th Cir.), cert, denied 464 U.S. 9 1 4

(1983) .

O ̂ U O CD 1UI\

A. Admissions Policies and Practirps

1• Background Fart^

In 1961, less than one week after James Meredith applied to

the University of Mississippi, the Board adopted a policy

12

requiring all applicants for undergraduate admission to any state

institution of higher education to take the American College Test

(“ACT”). Ayers I, 674 F. Supp. at 1530-31. Several months

later, the Board authorized each university to set a minimum ACT

score for eligibility for admission. Id^ at 1531. By 1963, the

University of Mississippi, Mississippi State University, and the

University of Southern Mississippi required an ACT composite

score of at least 15 for all freshmen applicants. Id^ At the

time, the average ACT score among white students was 18, while

that for black students was 7. Fordice, 505 U.S. at 7 3 4 .

When this case was tried initially in 1987, admissions

standards for first-time freshman varied along with the

historical racial identiflability of each institution. Four HWIs

continued to require a composite score of at least 15 on the ACT

for automatic admission; the other HWI, Mississippi University

for Women, required a score of 15-17 together with a high school

grade point average of at least 3 . 0 on a 4 . 0 scale, or a score of

at least 18. Ayers I, 674 F. Supp. at 1533-34. The HBIs

required a minimum ACT composite score of 13. Id̂ _ at 1534.11

Based on the undisturbed factual findings of the district

court — and unmoved by lower court determinations that the

admissions standards derived from policies enacted in the 1970s

to redress the problem of student unpreparedness — the Supreme

Court concluded in Fo_rdice that the policies were traceable to

than theTJWIsBIflthin^hined liberal exceptions policies

an S T A S E S ? ^

13

the dSLjUEE system, were originally adopted for a disoriminatory

purpose, and continued to have discriminatory effects. 5 0 5 u s

at 734. The Court found that the minimum ACT requirements

restrict[ed] the range of choices of entering students as to

which institution they may attend in a way that perpetuate[d]

segregation.” Those students who received ACT scores too

low to meet the admissions requirements at the HWIs were

restricted to the HBIs or community colleges if they wanted a

higher education. id., at 734-35. As the Court stated,

[P]roportionately more blacks than whites face[d] this choice:

In 1985, 72 percent of Mississippi's white high school seniors

achieved an ACT composite score of 15 or better, while less than

3 0 percent of black high school seniors earned that score.” id̂ _

at 735. The Court also deemed ‘‘constitutionally problematic” the

fact that the State denied automatic admission if an applicant

did not achieve the minimum ACT score specified for a particular

institution, without also considering high school grades as an

additional factor in predicting college performance. id, at

736.12

Plaintiffs' challenges on remand included the use of

differential ACT-based admissions policies at the HWIs and HBIs,

as well as the use of ACT cutoff scores and alumni connection in

12

14

Thethe award of undergraduate scholarships at the HWis. 13

district court's ruling on each of these issues is now before us

on appeal.

2. Undergraduate Admissions Standards

a. District court ruling

The district court concluded that “ [undergraduate

admissions policies and practices are vestiges of de jure

segregation that continue to have segregative effects.” Avers

II, 879 F. supp. at 1477. More specifically, the court found

that the admissions standards in place at the time of the 1987

trial were traceable to the prior de jure system and continued to

have segregative effects in a system where racially identifiable

institutions offer numerous duplicative academic programs. id̂ .

at 1434. The court held that defendants had a duty to eradicate

use of the ACT cutoff score “as a sole criterion for admission to

the system when the ACT is used in conjunction with differing

admissions standards between the HBIs and HWis.” Id. 14

nertaininrr ^ ffS alS° challen9ed policies and practices

l admissions exceptions. The district court's finding that no such policies or practices are traceable to the de—jure system is not contested on appeal.

14

se unlawful n°^ rUle that use of. an ACT cutoff is per. , ‘. Rather, its particular use in any circumstance

cha 11 e n a e d ^ C°nsider “hathar as a =°mpoLS of S e policy

S S S ? da7 r r . SsSp"attriS:ble tD Pri°r segregation.

of A c S S o r i r S S i d S S S 6/ 131!11” 3 ' claims that tha addition scores to high school grades as a predictor of freshmangrades improves the prediction only marginally, the district

admTL?°nC^ ded that the ACT Was “a so^ d component of the

w Sh hiSSSoolSrades ^ reaS°n that the ACT' in c°"*ination 9 schOQl grades, remains a better predictor of academic

15

Although admissions standards had been modified somewhat by

the time of the trial on remand, the district court found that

they "basically utilized a version of the 1987 standards with

various exceptions." Id. at 1431. m 1989, the ACT was replaced

by the Enhanced ACT. Id. at 1430. Scores on the two tests are

not equivalent; the American College Testing Program accordingly

publishes concordance tables that correlate scores on the old ACT

and Enhanced ACT according to percentile rank. 15 The

introduction of the Enhanced ACT prompted the Board to solicit

recommendations from the eight universities for revised

admissions standards based on the new test. Each HHI recommended

use of an Enhanced ACT score of is for regular admission, which

approximated the previous standard of an ACT score of 1 5 . Each

HBI recommended use of an Enhanced ACT score of 15 for regular

admission, the concordant value of which was 1 1 on the old ACT.

Because the HBIs had previously required an ACT score of at least

13 for regular admission, this recommendation represented an

effective lowering of admissions standards at these

institutions.,s Throughout the system, students not qualifying

performance than either criterion alone.”

conclusion is supported by the record. Id. at 1482. This

15

Of 18 on the E n h a n c e d ° A C T ^ • lnS^hn̂ e' haS 9 concordant value

would be in thfsamf percentile r L ^ n a °f 15 °n the ACTEnhanced ACT. P 1 rankln9 as a score of 18 on the

foreclosed^i^an^earlier^ncreasy Her increase in minimum ACT requirements.

16

for regular admission could be admitted as “high risk”

exceptions. The recommended Enhanced ACT scores for high risk

applicants ranged from 14 to 17 at the HWIs, and from 12 to 14 at

the HBIs. The Board approved all recommendations. 17

Differential admissions standards thus persisted in the system

through the 1994 trial and, as found by the district court,

resulted in the 'channeling effect' described in Fordice.” id.

at 1434. The district court's remedial order responded to the

standards in place in 1 9 9 4 .18

Defendants proposed, and the district court ordered

implementation of, new admissions criteria that standardize

requirements at all eight universities beginning with

applications for admission in the fall of 1996. The new criteria

in liohrofhev?den^Ct C°Urt'S r U l i " 9 a9ainst this backdrop and light of evidence concerning educational soundness.

17 The district court noted that although the lower ACT

S E i S S S f is%heBIn “T °ri9ina11* ProPosedby°the £55252 25 ' ^ th Board s responsibility to manage the higher education system in accordance with constitutional principles. Ayers II. 879 F. Supp. at 1 4 3 4 . rurional

While it found that admissions policies continued to have segregative effects, the district court also fou^d that

pa£ticioationPof If P°llCy or.Practice of minimizing the £55555” ^ of African-Americans in the [higher education]

~Yr S 11 • 8 7 9 F- SuPP- at 1 4 35. The court found credible evidence indicating that defendants had made substantial

See idSSat°!i' « 3 “ i n ° r i t Y to higher education.£j|e 1 0 . at 1433, 1435. In Mississippi, the ratio of the qtafp’c

shiire of the nation's black enrollment in public four-year

institutions to its share of the nation's blacj poSSati™ is

W * st«es Seeai’dthetn5'^?nal “ean a"d that °* ”anV n™ de -3-' f spates. See ld^ at 1435. Private plaintiffs aDDear tn

^ Pend !hat the district court’s finding of no current per se p cy of limiting access to the higher education system is

SiSS S ° t neous- we conclude that a"^ c o S t S i:

17

grant “regular admission” 19 to applicants who have (i) a gpa of

at least 3.20 in a designated core curriculum, (2) a GPA of at

least 2.50 in the core curriculum or class rank in the top 50%

and an Enhanced ACT score of at least 16, or (3) a GPA of at

least 2.0 in the core curriculum and an Enhanced ACT score of at

least 18. Id. at 1477-78.

The admissions policy ordered by the district court provides

an important alternative to regular admission through a spring

screening and summer remedial program for applicants who do not

meet the reguirements for regular admission. Students

participating in the spring screening process will take the

Mississippi College Placement Examination (the “accuplacer”)

during the spring of their senior year in high school. Based

upon these scores, Enhanced ACT subtest scores, and counselor

interviews, students will either be admitted for the fall

semester or invited to participate in the summer remedial

program. 20 The summer program is designed to provide ten to

eleven weeks of remedial instruction in reading, writing, and

mathematics, taught both in traditional classroom settings and

20 T,__ i appears, based on the language of the RnarH1cproposal and testimony durina trial \-h = +- 1 rne B°?rd s

options. advised to pursue other educational

18

through computer-assisted individual components. id^ at i478.

In addition, the program plan incorporates cultural and

recreational activities to “climatize” students to the college

campus. IdJ1 Those students who successfully complete the

summer program, by passing at minimum the remedial English and

mathematics courses, will be admitted in the fall.

The district court found that “the new admissions standards

through their uniformity will eliminate the prior segregative

effects of the previous differential admissions standards between

the HBIs and HWIs, noted by the Supreme Court in Fordice.” id_̂

at 1481. The district court found that as compared with the

standards litigated in the 1987 trial, the new standards would

result in an overall increase in the number of black students

eligible for regular admission to the university system. 22 As

. Although the district court made no specific findinas in

remed?J?ard' the undlsPuted evidence indicates that the summer remedial program is a departure from past remedial practices

order" f5i universit:y system. Prior to the district court's order, full semester remedial courses were offered at each

summerSnrn * Altho!!9h students who are granted admission via the summer program must participate in a year-long academic suooort

program designed to provide individualized support for marainallv

students enrolled in regular academi^credl? courts Y

a^ nJly.many of the remedial courses previously offered during

^ r t T A T . t . r . l l ^ be ell"lnated P I - ^ ?

impact:,t. The new standards were predicted to have the following

(a) the pool of black students eligible for regular admission to a public HWI will increase from

s ? u d tD 52’5%; (b) the P°o1 of b^ck

1 9 9 5 wni i 9lble f°r regular admission at the HBIs in co Wldl bf lncreased from approximately 45.3% to 52.5%, (C) the pool of black students eligible for

admission to the system as a whole will also increase

19

1994compared with the standards in place at the time of the

trial, which were less stringent than in 1987 as a result of the

1989 changes in requirements at the HBIs, the new standards would

result in an overall decline in the percentage of black students

eligible for regular admission to the system. 23 The district

court noted, however, that the summer program offers a distinct

opportunity for applicants to gain admission. 1^. at 1 4 7 9 ."

The court found the summer program to be "credible and

educationally advanced. In its proposed form, it is considered

by its developers as an educationally sound developmental

system.” I<U at 1481. The district court concluded that

system as either regular or remediated admittees.

Id.

Finally, although the State's community college system is

1987rstandards°Sed 1 9 9 5 Standards «■ compared with the

Ayers—II, 879 F. Supp. at 1 4 7 9 .

ACT were '"eligible ̂f or ̂ requi'ar- ̂ admi sc^°°* graduates who took the

system at the time of the 1 9 9 4 trial 10?h SOine university in the

projected to reduce this figure to 52 I T ”***F. Supp. at 1 4 7 9 . y >̂2.5% or 50.7%. Ayers II. 879

“summer program” ̂ nly C°UWe note^hat1S flIldlng. in terms of the

can^ead ^admission fSr ^ T i l ^ ^ " T s S e n i ^ o g r a m

i^the summer r e m e d i a l £ e £ . f ' ^ F^ ^ ° "

20

the subject of a separate lawsuit, the district court made

findings and ordered relief in this regard because the community

college system is relevant to the issue of access to higher

education. The court found evidence that the community college

system “can have an impact on the admissions policies of the

universities and their ability to further diversify institutions

of higher learning.” Id^ at 1475. The court also found,

however, that the community college system in Mississippi is not

providing remediation for students unprepared for four-year

institutions “to any great degree.” Id^ The district court

apparently linked this to at least two factors. First, in

contrast to the open admissions policy that prevailed at all

community colleges when this case was tried in 1987, some

community colleges now require minimum ACT scores for admission

to certain programs. IcL at 1474-75.25 Second, the

“overwhelming majority” of students who start at the community

college level do not transfer to four-year universities. Id^ at

1475. The University of Southern Mississippi has the highest

proportion of transfer students in its student body, largely

attributable to its recruiting efforts and articulation

agreements with several community colleges in surrounding

regions. IcL, Black students transfer at a significantly lower

25

colleqe is ̂ iot ^ A°T CUt°flfs for admission to the community lege is not an issue in this case, and the district court -̂i*

not make findings or conclusions with respect to the

onstitutionaiity of this practice. Accordingly, we do not

opinion. aSPeCt °f the COITm,unity college system in our

21

rate than whites, possibly because a high percentage of black

students in community colleges are enrolled in two-year

vocational programs.

The district court concluded that the State “is losing a

valuable resource in not coordinating the admissions requirements

and remedial programs between the community colleges and the

universities.” Id, The remedial decree contains a provision

ordering the Board “to study the feasibility of establishing

system-wide coordination of the community colleges in the State

m the areas of admissions standards and articulation

procedures,” and to report its findings to the Monitoring

Committee. id, at 1496.

k* Arguments on appeal

The district court s finding that undergraduate admissions

policies and practices are vestiges of de jure segregation that

continue to have segregative effects is not contested on appeal.

Plaintiffs do contest the remedy thereupon ordered.

Plaintiffs challenge to the admissions remedy has two

parts. First, plaintiffs argue that the district court's

adoption of the Board's proposed standards was improper because

these standards will significantly reduce the number of black

students eligible for regular admission to the university system,

and thereby disproportionately burden black students with a loss

of educational opportunity. Plaintiffs assert that the district

court was obligated by Fordice to consider the educational

soundness of alternative proposals that would have excluded fewer

22

so.black students, but failed to do

Second, plaintiffs argue that the district court's reliance

on the spring screening and summer remedial program to compensate

for the projected decline in regular admission of black students

was inappropriate because the program was untested and

incompletely defined at the time of trial. Plaintiffs contend

that although the district court found the summer program to be

“credible and educationally advanced,” it did not specifically

find that the program would be an effective means of identifying

students capable of succeeding in college or that it could

achieve the same results as “existing remedial p r o g r a m s . m

addition, plaintiffs argue that the summer program is not a

viable option for the many black students who must work during

the summer in order to afford to go to college in the fall, and

that the community college system currently does not provide an

adequate alternative. Plaintiffs therefore argue that the Board

should be required to maintain existing remedial courses and to

adopt standards that minimize any reduction in the number of

black students eligible for admission, at least during the period

that the summer program is being tested and the community college

**&5SE&BSiESSag3P

23

system undergoing change.

Although their criticise of the new admissions standards

coincide, private plaintiffs and the United states advocate

different admissions policies as alternatives. Private

plaintiffs proposed below and re-urge here adoption of a tiered

admissions policy, in which admissions reguirements vary along

with the mission of each university,2' with the most accessible

tier having “open admissions." By “open admissions,” private

plaintiffs mean a policy of granting admission to students with a

high school diploma and ACT score of 10. at 1480. Under

private plaintiffs' proposal, the three comprehensive

universities would use the admissions standards proposed by the

Board, and Jackson state University would have open admissions

for eight years with the option thereafter of gradually raising

admissions standards to the level prevailing at the comprehensive

universities. Id^ Existing remedial programs would be

strengthened in this scheme.

The united states proposed below and re-urges here an

admissions policy, which was presented to the Board in 1992 but

State Unpirsi?” a r r “LmprehensiJe"Minive?si?i4sanwhichSo??iPPi

statruniv“ si??9L s nanh"u?bfn"1mVel °t ?e9ree Jackson

~ £ a t 1 ^ “ S°ShiSh1 T T . tS c ^ S n

Si“ e?sf^y for w ^ e n 1^ 0^ ^ State UniVerSity'“regional" « v.r" ie th" S ? P1'V a U ?y stat* diversity are education. In priJaie b^a^tf??.' Pr“ « H y °n undergraduate

universities w o S l ^ n s S f t S I E m L T a ^ c ^ i b ^

24

would be granted tonever adopted, in which regular admission

students achieving (!) a 2.0 GPA in the core curriculum and a

minimum of 16 on the Enhanced ACT or (2) a 2.50 GPA in the core,

a ranking in the top 50% of the class, and a minimum of 13 on the

Enhanced ACT.28 The United States contends that under this

standard, an estimated 73.6% of black students who took the ACT

would qualify for admission, as compared to 52.5% or 50.7% under

the proposal adopted by the district, court. The United States

states that “ACT predictive data indicate that, at the [HBIs],

where remedial instruction was given, freshmen with these

qualifications could be expected to achieve at least a C

average.” U.S. Br. at 12.

Defendants argue that the new admissions criteria wholly

eliminate prior policies traceable to de jure segregation.

Defendants contend that the new admissions standards sufficiently

address the concerns articulated in Fordice because they do not

differentiate between universities according to historical racial

designation and do not rely on the ACT as the sole criterion for

admission. Defendants argue that under Fordice. the traceable

admissions policy was the Board's particular use of differential

ACT cutoff scores, which effectively channeled black students to

the HBIs, and not use of the ACT per se. Accordingly, defendants

contend that the new policy is not traceable to the prior de jure

28, The district court noted that the United States “has

4yers 11' 8 7 9 F- SuPP* at 14807States does not urge this standard on appeal. The United

25

system end may be implemented because the record discloses that

it is educationally sound and was not adopted for a

discriminatory purpose. While defendants maintain that F o r d W

does not require the district court to select the educationally

sound alternative with the least discriminatory effect, they

argue that even if the district court did have such an

obligation, its findings regarding the segregative effect and

educational soundness of the new admissions standards effectively

discharged it.

c. Analvsi s

The district court's findings that the new criteria for

admission are educationally sound and will not perpetuate

segregation within the system are not challenged on appeal.

Plaintiffs contend, rather, that the district court erred by

failing to consider the educational soundness of proposals that

would have resulted in a smaller reduction in the number of black

students excluded from regular admission.

We agree with plaintiffs that it would be inappropriate to

remedy the traceable, segregative effects of an admissions policy

in a system originally designed to limit educational opportunity

for black citizens by adopting a policy that itself caused a

reduction in meaningful educational opportunity for black

citizens. we do not, however, understand the district court to

have done so. The district court considered and rejected

alternative proposals as educationally unsound, and expressly

contemplated that the remedial route to admission could alleviate

26

any potential disproportionate impact on those black students who

are capable, with reasonable remediation, 29 of doing college

level work.

We understand the district court to have determined, in the

specific context of formulating an appropriate remedial decree in

this case under Fordice, that access to higher education must be

provided only to those applicants who can demonstrate, based on

educationally sound and constitutionally permissible indicators,

an ability (with reasonable remediation) to do college level work

and who therefore have a real prospect of earning a degree. 30

The court found that admission of students unprepared to do

college level work may result in significant attrition

accompanied by unprofitable debt accumulation. Avers IT. 879 F.

Supp. at 1435.31 Fordice does not require that all students who

29

issue reflects that each of the universities athere has for many years recognized that remediation is appropriate to enable certain students successfully *.

uriiidVhUCati°n' ThC a"0Unt °f radiation that has beer 3 provided has varied among the universities. We recognize that how much remediation is appropriate or “rea^nn^hio” j

by concepts of practrcabi?^t/and^dScat^naT^ndn^s^0™ *

student* * * 1 Mi,fsissiPPi universities at issue here require students to achieve at least a C average in order to graduate

Indeed, as indicated in our discussion below, all parties kev*

SttZ ^tguments regarding the educational soundness of Yalternative admissions proposals to this standard.

maintain The court found that Louisiana institutions, which maintain open admissions, ‘‘suffer from a very high attrition rat resulting in students owing one, two or thre^ vefr* o£ rate

expenses and having little or nothing to show for it.” Avers^T

s r s S '

Boylan testified that "(access without an opportunity io succeed

27

would have been admitted under the prior, unconstitutional

admissions standards be admitted under the reformed admissions

standards without regard to the educational soundness of the

reformed standards, instead, the district court's mandate under

£gr4^Ce WaS limited to reforming traceable, segregative policies

the extent practicable and consistent with sound educational

practices.” 505 U.s. at 729.32 Having found admissions

policies and practices to be traceable to the de jure system and

to have present segregative effects, the district court properly

focused its consideration of alternative admissions policies on

their educational soundness and potential to eliminate existing

segregative effects; its focus, in turn, on ability to do college

level work is consistent with both the evidence as presented by

plaintiffs and Fordice.

i- Rejection of plaintiffs' ornnn^lc

isn t really access,

a revolving door.” If you have an open door it quickly becomes

The Court in Fordice declined would require the State to eliminate

present discriminatory effects of the

to adopt a standard that

insofar as practicable all prior system:

us We understand Private petitioners to urgeocus on Present discriminatory effects without

rootedSin9thh6ther SUCh conse(Iuences flow from policies Thm>S thri°r system, we reject this position.

as" shiripn!-9h they Seem t 0 dlsavow as radical a remedy as student reassignment in the university setting Y

their focus on student enrollment, faculty and staffemployment patter, [and] black citizens'coUege-

™ H'and de9 ree-granting rates” would seemingly9compel

rkl\ t0 thOSe upheld in green v- g°MS.V Kent County were we to adopt their legal standard.

505 U.S. at 730 n.4 (citations original); see also id. at 732 omitted) n. 6 . (second alteration in

28

The district court set forth in detail the respective

admissions standards proposed by private plaintiffs and the

United States. £ee Ayers II, 879 F. Supp. at 1479-80. Although

the district court credited expert testimony indicating that

differential or tiered admissions standards are both sound and

routinely used, id̂ . at 1482, it did not adopt private plaintiffs'

proposal in light of its finding that the open admissions

component of this proposal was educationally unsound. Id^ at

1481-82. The district court found that

tSiardSh?ihS ac^oss the nation generally are moving

Accordino re{?uirements, not lower ones.the testimony, students in working toward

If thpv1^ iUSUally d° that which is expected of them,

colleae b v^Jw need n0t PrePare themselves for

they Sil? no? d" 9 ^ curriculum in high school,them t?XL??o 5 0 * SUGh ^Preparedness may bringcollege campuses unable to execute the rigors of coiiege work and result in low retention ratSs

degrees ^ aC^ ffi“latl°ns and years expended with no ofg5?-; • • • Jt has_also been shown that institutions Stndon? learning which open their doors to unprepared students via open admissions not only do a disservice

o many of the admittees, but can lower the quality

ge?4 ral?yUr y' ^ preStige of the institutions

~ at 1482-83. These findings are not clearly erroneous, and

the district court did not abuse its discretion in rejecting

private plaintiffs proposal.

Even assuming that tiered admissions could be implemented

without open admissions as a component thereof, it was not an

abuse of discretion in this context for the district court to opt

instead for a policy based on uniform standards. in the

Mississippi system of higher education, differential admissions

criteria were rooted in the de jure past and fostered both

29

perception that thesegregation of the races and the public

institutions with lower standards ~ the HBIs ~ were of inferior

quality. Id*, at 1477, i486. A tiered system would continue to

differentiate among institutions based on their respective

missions. See at 1482. In light of the history of

differential admissions in Mississippi higher education, and in

light of its finding that policies and practices governing the

missions of the universities are traceable to de jure segregation

and continue to have segregative effects, the district court was

within its discretion to unify standards across institutions.

The standards proposed by the United States met this

interest in uniformity, but were fixed at a level that the

district court found to be educationally unsound. Under the

United States's proposal, students with a 2.5 GPA and a class

rank in the top 50% would qualify for regular admission with an

Enhanced ACT score of 13. while this formula adds high school

grades and class rank into the eligibility determination, it

nevertheless represents a lowering of the ACT score requirement

from even post-1989 levels at the HBIs. In contrast, students

with identical qualifications would need an Enhanced ACT score of

16 to qualify for regular admission under the Board's proposal.

The district court concluded that the requirements for regular

admission under the Board's proposal were “quite moderate,” and

stated that it “does not find persuasive or educationally sound

the adoption of open admissions or continually lowering

admissions standards, as was done at the HBIs after the 1987

30

trial. — We understand this finding to encompass the

standards endorsed by the United States.

Both plaintiffs and defendants cite ACT predictive data in

support of their respective proposals. The United States points

out that such data indicates that students with the minimum

qualifications they propose would be expected to achieve at least

a C average by the end of their freshman year at each of the

HBIs. We note that such students are predicted to complete their

freshman year with grades significantly below a C average, the

minimum required for graduation, at any of the HWIs. See

PP 39-R. Defendants highlight a different aspect of the same

predictive data, which the district court apparently found

persuasive: students with the minimum qualifications proposed by

the Board would be expected to complete their freshman year with

a C average or slightly below at each of the HWIs. The district

court s finding that the Board's proposed standards are “quite

moderate” is indeed supported by the evidence. On this record,

the district court could fairly conclude that it would be

educationally unsound to adopt an admissions policy under which

students could do college level work at only three institutions

in rhe system. 33 We realize that no set of standards is without

its flaws. Significantly, as we discuss below, the standards

that the district court did adopt provide an alternative route to

. . Under the United States’s proposal, the three

ihStinTtl0nS at which students could do college level work are

couldhave lh& Standards Pr°P°sed by the United States therefore could have the perverse, albeit unintended, effect of

perpetuating the channeling effect described in Fordice.

31

Theadmission that does not rely on ACT scores whatsoever,

district court's decision to order implementation of this system

rather than dilute standards for regular admission, was a proper

exercise of its discretion.

1 1 * Reliance on spring screening and summer- remedial program

The district court recognized the likelihood that the

Board's standards would reduce the number of black students

eligible for regular admission as compared to then-prevailing

standards, 34 and chose to adopt them only in conjunction with

the additional opportunity to gain admission through the spring

screening and summer remedial program. The district court was

unable to conclude that the new standards, which provide an

alternative route to admission that does not rely on ACT scores

whatsoever, 35 would actually reduce the total number of black

students eligible for admission either as regular or remediated

admittees. In light of the district court finding that lowering

admissions standards “as was done at the HBIs after the 1987

trial” is educationally unsound, the court apparently determined

that to the extent any reduction in the number of black students

eligible for admission relative to post-1989 standards does take

tha Board's ' s t a n d s ̂ the

ex?steLadatiS?ie°ntr 1V r reaSe relative'to^ndardl^ 1’ 1 6 ^

Supp « 1 4 7 9 trlal ln 1987' See Avers IT. 879 F.

reaardle«Cfldin9Jt° the Board' anV high school graduate

screening5 T h e b e ' perf°r"'an«. participate in spring

screening take the Ic? I d ^ " ^ “ “ ParticiP*hts i" spring

32

place, it may reflect the educational unsoundness of prior

policies. As contemplated, the new standards should result in

the identification and admission of those applicants who, with

reasonable remediation, can do college level work. This is

consistent with fordice's mandate of a reformed admissions policy

that is practicable and educationally sound.

The district court also recognized that the spring screening

and summer remedial program was untested and its standards not

fully established at the time of trial. See id^ at 1478-79,

1481. we think that the program was sufficiently defined that

the district court did not abuse its discretion in ordering its

implementation. If, however, as plaintiffs suggest may be the

case,36 the spring and summer program is unable to any

significant degree to achieve its intended objectives of

identifying and admitting otherwise eligible applicants — j.e,.

applicants who could, with reasonable remediation, successfully

complete a regular academic program — for whatever reason, then

the program must be reevaluated.37 The district court's proper

presents rec^ntfrd^covere^^vi^e^l con^rni^g \h^first ̂ ea^1 s implementation of the new standards and the Spring and s u L ^

n b i ^ Th\ diStriCt court s conclusion that the Board's

33

retention of jurisdiction over this action indicates its intent

to examine this important component of the admissions system once

the relevant data becomes available.38 if the district court

ultimately concludes that the spring screening and summer

remedial program (as it may be modified) is unable to any

significant degree to achieve its objectives, then the court

should, if possible, identify and implement another practicable

and educationally sound method for achieving those objectives.

iii* Elimination of existing remedial coursps

We have thus far addressed the spring and summer program as

a component of the reformed admissions policy. We turn now to

the argument made by the plaintiffs that the district court erred

in relying upon the summer remedial program to replace the

existing remedial courses in the absence of a finding that the

summer program could achieve the same results as the

universities' existing remedial courses in enabling students to

succeed in and graduate from college.

We note in this connection that the plan proposed by the

Board provides that “[d]evelopmental studies are only offered

academic placement analysis ” Avprc tt m o t? <-

«a°soSWeS in9 insofar •• is

oPthePable °f d°in9 £vel Wor*

ZJ& TrXtrlT-i— ‘Ar-nV ~ rr 5SSV E ""

38____— £feen v- County Sch. Bd. . 391 U.S. 430 439

removed.”). * G lmposed segregation has been completely

34

during the summer session.” In ordering implementation of this

plan, the district court tacitly approved the elimination of

most, perhaps even all, of the remedial courses that had been

offered by all the universities at issue here, most notably by

the HBIs. This is a troubling decision, implicating the reformed

policies for regular admission as well as the spring screening

and summer remedial program. On the one hand, there was evidence

to indicate that an intensive, structured program of remedial

instruction during the summer months prior to a student's

immersion in the college experience may actually be more

effective at preparing students for college than a more diffused

program of remedial instruction throughout the academic year. On

the other hand, the district court appeared to base its decision

not to consolidate Mississippi Valley state University with Delta

State University, at least in part, on the significant percentage

of students enrolled in remedial, or developmental, education at

Mississippi Valley and on Mississippi Valley's role as “a

significant nurturer of underprepared blacks,” id^ at 1 4 9 2 , a

role that the district court apparently did not want to see

eliminated.39 Further, it is not clear to what extent the

operative predictive data assumes the existence of remedial

programs insofar as it is based on historical achievement. It is

clear that the predictive data relied upon by the State in

39• . We flnd it: significant that the presidents of

s t h e ^ t u d e n t s ^ t h e y

35

support of its argument that its proposed admissions standards

were “quite moderate" indicate that students who are admitted

with the minimum quantisations required under the new standards

are not predicted to achieve a c average during their first year

at at least three of the HWIs. This suggests, as defendants note

in their brief and indicated at oral argument before this court,

that many students who are admitted under the reformed standards

will need “substantial educational assistance," possibly

including remedial courses." Remedial courses may be an

important part of the admissions policy at any school in which a

significant number of students are not predicted to achieve a c

average during their first year.

The plaintiffs did not challenge the State’s existing

remediation policies as traceable to the de jure era. There was

therefore no requirement, under Fordice, for reformation of those

policies as such. However, the Board's proposed admissions

standards (Bd. R-202) treated the adoption of the summer program

and the elimination of the existing remedial courses as

components of its admissions standards, and the district court,

m ordering the implementation of the Board’s proposal,

effectively did the same. The principle that apparently

underlies the Board's admissions policy (and, therefore, the

S S ”= i s = S , S

36

district court’s decision) is that, in the case of any applicant

what can and cannot be accomplished with reasonable remediation

is a key element of the admissions decision. Clearly, this

principle is educationally sound. But the court's action in

eliminating the existing remedial courses can legitimately be

challenged by plaintiffs as an inappropriate feature of the

court's admissions remedy. We have recognized that there are

some tensions in the district court's findings in this regard.

In the light of these tensions and the absence of specific

consideration of the justification for, or reasonableness of,

eliminating these unchallenged courses, we are sufficiently

concerned about the district court's exercise of its discretion

m thls regard to direct the court on remand to reconsider its

decision to eliminate these courses. On remand, the district

court should determine if remedial courses are needed to help

ensure that students admitted under the new admissions criteria

have a realistic chance of achieving academic success.41

iv. Timing

The United States argues that it may take several years for

the summer program to be thoroughly implemented, tested, and

evaluated and argues that during the interim, an admissions

policy that minimizes any reduction in the number of black

41

decision whether to take more evidence on the

With the summer remedial program, is left to the distaic? co“ t.

37

be installed.42students eligible for regular admission should

We reject this argument. The summer program has sufficient

promise, on the present state of the record, to allow it “to

prove itself in operation,” Green v. Countv snh n* 391 u>s>

430, 440-41 (1968), should the district court decide to continue

on that path. There is no reason why, however, reconsideration

of the district court's decision to eliminate the existing

remedial courses cannot be done promptly. We intimate no view on

the outcome of that reconsideration.

d* Conclusions regarding undergraduate admissions standards ------------- —

Except as set forth below, we affirm paragraph 2 of the

remedial decree which reads in relevant part as follows: “The

1995 admissions standards as proposed by the Board for first-time

freshmen, effective for the academic year (1996-97], shall be

implemented at all universities.” Ayers II. 879 F. Supp. at

1494. We do not affirm paragraph 2 insofar as it eliminates the

remedial courses previously offered at each of the eight

universities. We remand this latter issue for reconsideration in

the light of this opinion. We understand the district court's

continuing jurisdiction to encompass the evaluation of the

effectiveness of the spring screening and summer remedial

to the tiie a Si1milar arc?uinent with respect. ime cnar it will take to implement chancre =,+-

t?meerto»tati?n °f this aspect of the remedial'decree wUl £aLpolicy?eS nDt rSqUlre installation of an interim admissions

38

program, as a component of the admissions system, in achieving

its intended objectives of identifying and admitting those

students who are capable, with reasonable remediation, of doing

college level work but who fail to qualify for regular admission.

Should the district court ultimately conclude that this program

(as it may be modified) is unable to any significant degree to

achieve its objectives, then the court will need to identify and

implement another method for achieving those objectives.

3. Scholarship Policies

a* District court ruling

While the district court found that undergraduate admissions

policies in general are vestiges of de jure segregation that

continue to have segregative effects, it found that scholarship

policies in particular are not. On remand, plaintiffs challenged

the use of ACT cutoff scores for the award of undergraduate

academic scholarships at the HWIs, as well as the use of ACT

cutoff scores and alumni connection in the award of nonresident

fee waivers for out-of-state admittees.43 Unlike most other

43 The n°nresident feG waivers for children of nonresident

scholarship^6”err»ed t0 ln thG record also as “alumni scholarships. Our use of the term “scholarships” encompasses

uSf?heCt ^ ° ‘‘arShipS,aS WeU aS r e s i d e n t f e e w a i v e d bu^ we

this type of awa?d6S ^ WaiVer when referring solely to

= u°te that Mississippi University for Women offers certain

that ?eaui?e t° reSlden ̂and President children of MUW alumni reqdlre a minimum ACT score of 21 for eligibility These scholarships are distinct from the nonresident fee waivers but Plaintiffs challenge the use of the ACT cutoff sJore and ?Ae

scholarshipsCas°well.dGterm^n^n9 eligibility for these

39

forms of financial aid, the scholarships challenged by plaintiffs

are generally awarded on the basis of academic achievement, not

financial need, and do not require repayment by the recipient.

The district court found a significant disparity in the

percentage of nonresident fee waivers awarded by race in any

given year. 1^. at 1433. The evidence indicated similar

disparities in the award of academic scholarships. The district

court concluded, however, that

waiveri^to hi k S 1 y of allowing [nonresident fee ] to be based on ACT cutoffs and the use of ACT cutoff scores as the sole criterion for the receipt of

liikigiCwith°iirS!jiP in0nieS haS n0t been Proven to have linkage with the de ~]ure system, and there is no

tha ̂th6Se Practices currently foster

Shoi“ ?hirp^he raC6i such.as influencing student c a n n o t TheJefo5e' reformation of these policies cannot be ordered consistent with the law of the case

c o ^ f f i n d s T * °f liscriminatory purpose of which ?h4 court finds none. The use of ACT scores in awardina

ls.wldesPread throughout the United Stltes and generally viewed as educationally sound.

— at 1434-35 (footnote omitted). The district court did not

make a specific finding with regard to the traceability of the

alumni connection requirement for nonresident fee waivers. The

remedial decree does not order alteration of any of the

challenged scholarship policies.

b- Arguments on apppai

Plaintiffs argue that the district court clearly erred in

finding that the use of ACT cutoffs in the award of academic

scholarships and nonresident fee waivers at the HWIs is not

traceable to the dual system and does not have segregative

effects. Although the district court's findings and conclusions

40

with respect to academic scholarships focus specifically on

policies that establish an ACT cutoff score as the sole criterion

for award, plaintiffs' challenge encompasses all instances in

which the HWIs require a minimum ACT score for scholarship

eligibility.44 Accordingly, plaintiffs have identified on

appeal numerous scholarships at various HWIs that are available

only to students with certain minimum ACT scores. Plaintiffs

contend that the use of ACT cutoff scores for scholarship

eligibility is traceable to the de jure system because under that

system ACT cutoff scores were implemented for the purpose of

excluding black students from the HWIs. The segregative effects

of this practice, plaintiffs argue, are evident in the racial

disparity in scholarship awards. Because black students receive

only a very small proportion of such scholarships, yet are more

likely than white students to be in need of financial aid, the

policy effectively reduces the number of black students able to

attend the HWIs. Moreover, plaintiffs argue that the record does

, -̂n Pretrial Order, private plaintiffs listed ac a

sP?pi!;fnged remnant “[t]he policy of using ACT cutoff scores in selecting persons to receive particular scholarships at the

idenSifdaJh leV?? aV ach HWI*” The United States similarly ACT L « B J alleged remnant as “[t]he practice of using the ACT m selecting persons to receive scholarships at the 9 undergraduate level.” p

u . si^nificantiy, plaintiffs do not challenge any of the scholarship policies at the HBIs and no party argues on appeal that such policies either are traceable to the d ^ W e ~

have present segregative effects. Accordingly, we^xpress no opinion on the scholarship policies at the HBIs or their

relevance in reforming scholarship policies to eliminate present

segregate effects. m fashioning the most appropriate K m e d f

court may £ind i c

41

not support the district court's finding that the use of ACT

cutoff scores in the award of scholarships is widespread.

Plaintiffs also contend that the district court erred in

upholding the practice of limiting nonresident fee waivers to

children of an institution's alumni. Plaintiffs maintain that

the alumni connection reguirement is traceable to the de jure

system in that parents of today's students were systematically

excluded from the HWIs under the de -jure system.

c- Analysis

Although it is clear from the record that undergraduate

scholarship policies were litigated on remand, the district court

made virtually no fact findings with regard to specific policy

criteria or operation. The parties' original briefing of this

issue on appeal was also scant.45 in response to our request

for supplementary briefing, plaintiffs provided a summary of the

challenged policies along with the racial breakdown of their

distribution for the 1992-93 year (and in one instance, for the

1991-92 year). Defendants have not contested the accuracy of

this summary, which is drawn from defendants' answers to

interrogatories and from other evidence introduced by defendants.

We therefore accept plaintiffs’ factual summary. According to

that summary, the scholarships alleged to be traceable to de jure

segregation and to have present discriminatory effects are as

45

“ “ p p - r rw % ^ e ssetded°,f and

schola?ship=PP tal briefi"9 the issue of undergraduate

42

follows:

DELTA STATE UNIVERSITY First-time freshman enrollment 1992-93: 21% black

ScholarshipName" MinimusACTScore

Nuabe' of Recsipients Dollars Received

Black White Total Black White Total

Dean's and

Presidential 26 2 160 162 $1,375 $131,175 $132,550

1% black 1H black

MISSISSIPPI ST#TE UNIVERS][TY First-time freshman enrollment 1992-93: 16% blank

ScholarshipName MinimusACTScore

Number of Recipients Dollars Received

Black White Total Black White Total

Entering

Freshman ACT 8,000

31 1 294 299 $2,000 $546,000 $555,000

Sharp Forestry 31 0 3 3 0 7,500 7,500Entering

Freshman ACT 5,000 and Schillig

29 5 454 468 16,250 596,836 626,836

Ramsey &

Elaine O'Neal and Hearin- Hess

26 0 41 41 0 115,500 115,500

Entering

Freshmen ACT

4,000, South

Central Bell,

and Jesse &

Lillian Tims

28 5 248 267 7,944 239,444 261,388

Leadership 20 8 71 80 3,600 34,450 38,550John C.

Stennis 24 1 6 8 1,000 6,000 8,000

Alumni 21 N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/ATOTAL 20 1117 1166 $30,794 $1,545,730 $1,612,774

2% black 2% black

46, , Plaintiffs advise in their brief that in some instances

h»C hf°r “0re than °ne scholarship with the same ACT cutoff score

SScJSShiTSEf'l ThiS re“ eCtS the ”ay defendants p r o v e d ”scholarship data in response to interrogatories.

43

MISSISSIPPI UNIVERSITY FOR WOIIEN

First-tiae freshaan enrollaent 1992-93: 21% black

ScholarshipNaas MiniauaACT Nuaber of Recipients Dollars Received

Score Black White Total Black White Total

Centennial and

Eudora Welty 26 0 26 26 $0 $142,464 $142,464

Regional 21 _____2 68 70 1,200 74,400 75,600Aluani 21 2 50 52 600 32,540 33,140Academic 21 10 208 218 3,402 111,500 114,902Valedictorian 21 0 6 6 0 7,075 7,075Salutatorian 21 0 6 6 0 4,125 4,125TOTAL 14 364 378 $5,202 $372,104 $377,306

4% black 1% black

First-time freshman enrollment 1991-92: N/A

ScholarshipNaae MiniauaACT

Score

Nuaber of Rec: ipients Dollars Received

Black White Total Black White TotalSpecial

Conditions 21 34 154 188 $40,820 $139,163 $179,983

Academic 25 0 79 79 0 130,425 130,425 |TOTAL 34 233 267 $40,820 $269,588 $310,408 I

13% black 135b black

UNIVERSITY OF IIISSISSIPPI First-time freshman enrollment 1992-93: 7% black

ScholarshipNaae MiniauaACT

Score

Nuaber of Rec.Lpients Dollars Received

Black White Total Black White TotalChildren of

Nonresident Alumni

21 1 305 307 $1,960 $529,512 $533,432

Children of

Faculty &

Staff Post- 1977

18 10 106 118 14,092 88,540 104,196

Children of

Faculty & Staff Pre-

1977-76

19 10 104 116 19,780 195,263 215,783

Academic 28 6 683 701 14,130 1,608,555 1,641,805Academic 30 2 27 29 9,500 105,000 114,500Academic 22 9 240 253 11,350 244,467 258,642

44

Special

Conditions 22 6 130 140 6,810 211,550 224,240

TOTAL 44 1595 1664 $77,622 $2,982,887 $3,092,598

3% black 3% black

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN III !S51SSIPPI First-time freshman enrollment 1992-93: 27% bind

ScholarshipName MinimumACTScore

Number of RecLpients Dollars Received

Black White Total Black White Total

Presidential, Schillig-

Baird, Pulley, Pulley, and Gough

29 0 36 36 $0 $194,043 $194,043

AcademicExcellence 28 7 352 371 8,375 773,490 816,860

Regional 25 0 43 47 0 72,914 79,774Alumni 21 1 143 146 1 ,960 230,333 236,213TOTAL 8 574 600 $10,335 $1,270,780 $1,326,890

1% black 1% black

The district court found that basing scholarship eligibility

on ACT cutoff scores is not traceable to the dual system and does

not have current segregative effects. We agree with the

principle articulated by the district court that use of an ACT

cutoff is not unlawful in all circumstances. “Rather, its

particular use in any circumstance must be examined to consider

whether as a component of the policy challenged, the same is

traceable to prior de,jure segregation.” Avers IT. 879 F. Supp.

at 1434. In light of the facts set out above, however, we

conclude that the district court erred in arriving at its

findings regarding traceability and segregative effects.47

47

cutoffs Our conclusion in this regard applies to the in all challenged scholarships. use of ACT

45

The district court may have applied an erroneous view of

traceability. As defendants point out in their supplemental

letter brief, a traceable policy is one “rooted in” the prior

dual system. See Fordice, 505 U.S. at 730 n.4, 732 n.6, 7 4 3 . it

is only “surviving aspects” of de, jure segregation that a state

need remedy, gee .liL. at 733. That is not to say, however, that

a challenged policy as it exists today must have been in effect

during the de jure period in order to be constitutionally

problematic. The undergraduate admissions criteria that the

district court found to be traceable, for instance, had been

modified several times since the de jure era but nonetheless were

found to be rooted in the prior system. Similarly, the Supreme

Court found Mississippi's scheme of institutional mission

classifications to be traceable to de jure segregation even

though it was not put in place until several years after

termination of official segregation. See id^ at 732-33, 739-41.

The Court noted that “[t]he institutional mission designations

adopted in 1981 have as their antecedents the policies enacted to

perpetuate racial separation during the de -jure segregated

regime.” Id^ at 739. m United States v, Louisian* this court

implicitly recognized that Louisiana's open admissions policy

could be traceable to that state's prior de jure system despite

its adoption only after de.jure segregation had ended. See 9

F.3d at 1167. Because the district court had not addressed the

policy s traceability, we left the issue open for resolution on

remand. id.

46

record does notIn this case, plaintiffs concede that the

contain evidence directly linking the use of ACT cutoffs for

scholarship purposes with any time prior to 1980. Such evidence

apparently was not developed because plaintiffs concluded, in our

view correctly, that the discriminatory use of ACT cutoffs to

exclude black students from the HWIs during the de jure period

establishes traceability with respect to all current practices

that limit black student access to the HWIs by setting ACT cutoff

scores at a level that disproportionately favors white students.

Defendants contend that plaintiffs have failed to prove

traceability because they have not produced evidence establishing

that the practice of using ACT cutoffs in the award of

scholarships was initiated either “(i) during de jure

segregation, (ii) as an integral component of de jure

segregation, (iii) to continue, perpetuate, or further

segregation, or (iv) because of some intentionally segregative

policy which formerly existed.”48 This argument misses the

mark. First, to the extent defendants suggest it is lacking,

evidence of discriminatory purpose is required to establish a

constitutional violation only for present policies that are not

traceable to the prior system; discriminatory purpose is not an

element of traceability itself. Fordice. 505 U.S. at 733 n.8.

Second, this argument ignores the relationship between

" ^yp0n motion Plaintiffs, the district court placed the

this Respect ?h°Ut a i s t r ^ c o ^ d i f

47

scholarship awards and grants of admission, an element nissing

from the district court's analysis as well.

Scholarship decisions are not wholly independent of

admissions in the way that most financial aid determinations are.

Indeed, the record indicates that at University of Mississippi,

Delta State University, and Mississippi University for Women, the

application for admission also constitutes the application for

scholarships. it is because scholarships are intended to reward

exemplary academic achievement, as defendants point out, that

scholarship decision criteria overlap more with those for

admission than for financial aid. By their nature, scholarships

are designed to attract outstanding students to the awarding

institution; that scholarships need not be repaid is a powerful

incentive for students to both pursue and accept them. As a

component of admissions, scholarship policies further the process

that ultimately culminates in matriculation. In finding that the

use of ACT cutoffs in the scholarship context is not traceable to

the de_ -jure system, the district court may have distinguished

scholarships too strictly from admissions, although its opinion,

which addresses scholarships as a component of admissions,

suggests otherwise. See Ayers II, 879 F. Supp. at 1424, 1431-35.

As presented by plaintiffs, the challenged scholarships

require students to achieve a certain minimum ACT score to be

eligible for the award. Accordingly, a student who has not

achieved the requisite ACT score will not be considered,