Shuttlesworth v Birmingham AL Brief for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

March 8, 2024

24 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Shuttlesworth v Birmingham AL Brief for Writ of Certiorari, 2024. 43766f4e-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4cd0bb4f-4d1e-4694-9cd5-7d16ac742bc3/shuttlesworth-v-birmingham-al-brief-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

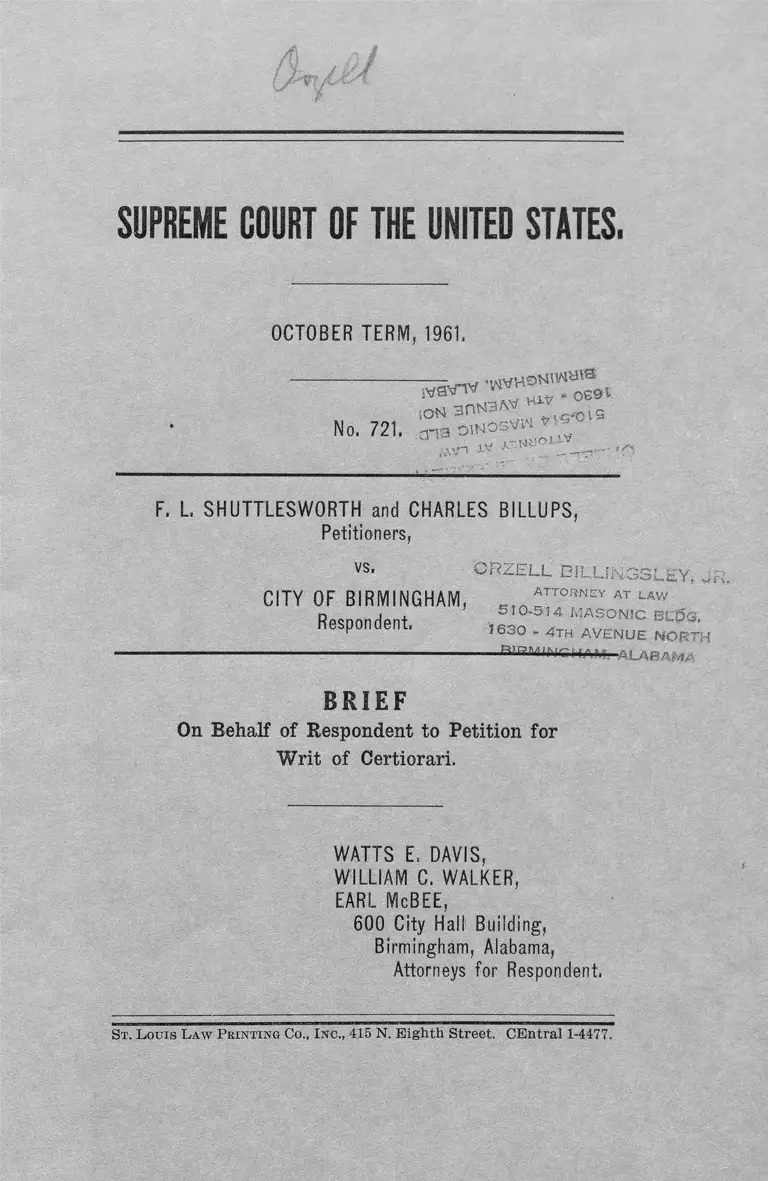

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

OCTOBER TERM, 1961.

---------------

No. 721.

F. L. S H U TTLE S W O R TH and CHARLES BILLUPS,

Petitioners,

vs. C E 2E LL DILLIiNi3SLEY,

a tto rn ey a t l a w

Resnondent " . 51 ° '514 m asonic blog . Kespondent. 1630. 4th a v e n u e n o r t

-------------------------------- ALASAft*/-

C ITY OF BIRMINGHAM,

B R I E F

On Behalf of Respondent to Petition for

Writ of Certiorari.

W A TTS E. DAVIS,

WILLIAM C. WALKER,

EARL McBEE,

600 City Hall Building,

Birmingham, Alabama,

Attorneys for Respondent.

St. Louis Law Printing Co., Inc., 415 N. Eighth Street. CEntral 1-4477.

INDEX.

Page

Statement in opposition to question presented for re

view .................................................................................. 1

Statement in opposition to constitutional and statutory

provisions involved ...................................................... 3

Statement in opposition to petitioners’ statement of

the case .......................................................................... 3

Argument:

Re: Lack of jurisdiction of the C ou rt......................... 4

Re: Constitutional and statutory provisions involved 5

Re: Question presented ............................................ 8

Re: Petitioners’ reasons for granting the w r it ......... 16

Certificate of service ...................................................... 19

Cases Cited.

Allen-Bradley Local, etc., v. Wisconsin Employment

Relations Board, 315 U. S. 740, at page 746, 62

S. Ct. 820, at page 824, 86 L. Ed. 1154 ..................... 6

Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707 ............................. 17

Bullock v. U. S., 265 P. 2d 683, cert, denied 79 S. Ct.

1294, 1452, 360 IT. S. 909, 932, 3 L. Ed. 2d 1260, re

hearing denied 80 S. Ct. 46, 361 U. S. 855, 4 L. Ed.

2d 95 ............................................................................... 17

Crane v. Pearson, 26 Ala. App. 571, 163 So. 821............ 6

Davis v. State, 36 Ala, App. 573, 62 So. 2d 224 .......... 11

Dudley Brothers Lumber Company v. Long, 109 So. 2d

684, 268 Ala. 565 .......................................................... 15

H

Garner v. State of Louisiana, 82 S. Ct. (1961) .7, 8,10,15,18

Gibson v. Mississippi, 16 S. Ct. 904, 162 U. S. 565, 40

L. Ed. 1075 ...................................................................... 7

Holle v. Brooks, 209 Ala. 486, 96 So. 341 ................. 6

Jones v. State, 174 Ala. 53, 57 So. 31, 3 2 ..................... 11

Local No. 8-6, Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers In

ternational Union, AFL-CIO v. Missouri, 80 S. Ct.

391, 361 II. S. 363, 4 L. Ed. 2d 373 ............................. 6

Martin v. Struthers, 319 U. S. 147, 63 S. Ct. 862, 87

L. Ed. 1313 .................................................................... 17

McNulty v. California, 13 S. Ct. 959, 149 U. S. 645, 37

L. Ed. 882 ...................................................................... 6

National Labor Relations Board v. Fansteel Metal

lurgical Corp., 306 U. S. 240 .....................................10,14

Ohio Bell Telephone Co. v. Public Utilities Commis

sion, 301 U. S. 292, 302, 57 S. Ct. 724, 729, 81 L. Ed.

1093 ................................................................................. 7,8

O ’Neil v. Vermont, 12 S. Ct. 693, 144 U. S. 323, 36

L. Ed. 450 .................................................................... 6,7

Parsons v. State, 33 Ala. App. 309, 33 So. 2d 164 . . . . 11

Pruett v. State, 33 Ala. App. 491, 35 So. 2d 1 1 5 .......... 11

Schenck v. United States, 249 IT. S. 47 ...................... 16,18

Swinea v. Florence, 28 Ala. App. 332, 183 So. 686 . . . . 6

Thompson v. City of Louisville, 80 S. Ct. 624, 625

(1960) ............................................................................ .13,15

Thorington v. Montgomery, 13 S. Ct. 394, 147 U. S.

490, 37 L. Ed. 252 ........................................................ 6

Williams v. Howard Johnson, 268 F. 2d 845 .............. 17

Statutes and Rules Cited.

Alabama Supreme Court Rule 1, Code of Alabama

(1940), Title 7, Appendix 6

I l l

City Code of Birmingham (1944):

Section 369 ..................................................................3, 5, 13

Section 824 ...............................................................10,11,15

Section 1436 ................................................................. 10,11

Code of Alabama (1940), Title 7, Section 225 .......... 7

Code of Alabama (1940), Title 14, Section 1 4 ............. H

Supreme Court Rule 21 (1), 28 IT. S. C. A .................... 4

Supreme Court Rule 24 (2), 28 U. S. C. A..................... 5

Supreme Court Rule 33 (1), 28 U. S. C. A .....................4, 5

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

OGTOBER TERM, 1961.

No. 721.

F. L. S H U TTLE S W O R TH and CHARLES BILLUPS,

Petitioners,

vs.

C ITY OF BIRMINGHAM,

Respondent.

B R I E F

On Behalf of Respondent to Petition for

Writ of Certiorari.

STATEMENT IN OPPOSITION TO QUESTION

PRESENTED FOR REVIEW.

Petitioners present a single question for the review of

this Court (p. 2).#

* Page references contained herein and preceded by the letter

‘ ‘P” designate pages in petitioners’ Petitions for Writ of Certiorari.

Page references contained herein and preceded by the letter “ R ”

refer to pages in the Records o f the proceedings below, which Rec

ords have common page numbers.

__o __

This question is predicated upon the supposition that

“ Alabama has convicted petitioners” of inciting1 or aid

ing1 or abetting another to go or remain on the premises

of another after being warned not to do so.

Petitioners then propose for review by the Court the

question of whether, in convicting and sentencing the pe

titioners, “ has Alabama denied liberty, including free

speech, secured by the due process clause of the Four

teenth Amendment ? ’ ’

The State of Alabama is not a named party in the case,

and so far as City of Birmingham, the respondent named

in this cause, is aware, no effort has been exerted at any

time to make the State of Alabama a party. Since “ Ala

bama” was not a party to the case below, and is not a

named party before this Court, the sole question presented

here for review seems entirely and completely moot and

ungermane, leaving thereby no question related to any

events taking1 place in the courts below for review by this

Court. The case below was a quasi-criminal proceeding

wherein the City of Birmingham sought to enforce one of

its local ordinances.

Petitioners take occasion to also predicate their ques

tion presented for review (p. 2) upon the hypothesis that

“ a Birmingham ordinance requires racial segregation in

restaurants.”

The petitioners’ reference to such an alleged ordinance

is mentioned here before this Court for the very first time

since the initial fding of the complaint by respondent in

the county circuit court below, and is not an appropriate

matter to be considered here under a petition seeking writ

of certiorari.

STATEMENT IN OPPOSITION TO CONSTITUTIONAL

AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED.

Petitioners contend tliat a section 369 of the 1944 Gen

eral Code of City of Birmingham is one of three ordinances

involved in this proceeding.

As mentioned above, this alleged ordinance has been

injected into this case for its first and only time in the

petition for writ now before this Court, and is not a proper

subject for consideration by the Court. The petition for

writ of certiorari should seek only a review of what lias

transpired below and is not properly an arena for intro

ducing new defenses which were not, exhausted in the state

courts.

STATEMENT IN OPPOSITION TO PETITIONERS’

STATEMENT OF THE CASE.

Respondent wishes to supplement petitioners’ statement

of the case by pointing out to the Court additional perti

nent testimony which, though brief, is not in petitioners’

statement:

“ . . . Rev. Billups came to his school, Daniel Payne

College, in a car and carried him (Davis) to Rev.

Shuttles worth’s house” (R. 28).

The record further shows “ that in response to Rev.

Shuttlesworth asking for volunteers to participate in the

sit down strikes that he (Davis) volunteered to go to

Pizitz at 10:30 and take part in the sit down demonstra

tions” (R. 29).

As noted by petitioners, Billups was present at the meet

ing and others in attendance at the meeting’ at Rev. Shut

tlesworth’s house participated in sit down demonstrations

the day following the meeting (p. 4).

— 4 —

ARGUMENT.

Re: Lack of Jurisdiction of the Court.

Respondent insists the Court is without jurisdiction to

entertain the “ petition for writ of certiorari” in this

cause, for that the petition was not served upon either of

the counsel of record for respondent, namely, Watts E.

Davis or Bill Walker, later referred to as William C.

Walker, whose names clearly appear upon the face of the

title pages appearing in each of the respective records now

before the Court in this cause as the only counsel of

record.

These two cases below, before the Alabama Court of Ap

peals, are reported respectively in 134 So. 2d 213 and 134

So. 2d 215; and, before the Supreme Court of Alabama, in

134 So. 2d 214 and 134 So. 2d 215. Each of the four re

ported cases show “ Watts E. Davis and William C. Walker

for Appellee” .

The proof of service, Form 75 (8-61-10M), as supplied

by the Clerk and subsequently filed with the Clerk of this

Court, demonstrates clearly that notice of the filing of the

petition, the record and proceedings and opinion of the

Court of Appeals of Alabama and of the Supreme Court

of Alabama, was served upon “ Hon. MacDonald Gallion,

Mr. James M. Breckenridge” . Service of the notice, which

is required by Supreme Court Rule 21 (1), 28 U. S. C. A.,1

to be made as required by Supreme Court Rule 33 (1), 28

IT. S. C. A.,2 was attempted to be accomplished by use of

1 The pertinent provision of Supreme Court Rule 21 (1 ) reads,

“ Review on writ of certiorari shall be sought by filing with the

clerk, with proof of service as required by Rule 33, forty printed

copies of a petition, . .

2 The pertinent provision of Supreme Court Rule 33 reads,

“ Whenever any pleading, motion, notice, brief or other document is

required by these rules to be served, such service may be made per

the mail. Supreme Court Rule 33 (1), 28 U. S. C. A., re

quires that service by mail shall be addressed to counsel

of record (emphasis supplied) at his postoffice address,

which, as shown supra, was not done in this case.

It is your respondent’s position that the petitioners’

failure to comply with the reasonable rules of this Court

in the above regard, whether done through carelessness

or indifference to the rules of this Court, leaves the re

spondent without notice of the proceedings pending in this

cause, as required by law, and that the Court is without

jurisdiction to proceed without the necessary parties to

the writ before the Court. The petition for writ seeking

certiorari should therefore be dismissed or denied.

The rules of this Court, Supreme Court Rule 24 (2),:!

28 II. S. C. A., do not provide for a separate motion to dis

miss a petition for writ of certiorari, and absent the rem

edy of any such motion, respondent prays that- nothing

contained in its reply brief shall be considered as a waiver

of its objection presented here to the jurisdiction of the

Court.

ARGUMENT.

Re: Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved.

It is contended by petitioners that “ Section 369 (1944)”

of the respondent’s city code is involved in the case now

before the Court.

sonally or by mail on each adverse party. If personal, it shall con

sist o f delivery, at the office of counsel of record, to counsel or a

clerk therein. If by mail, it shall consist of depositing the same

in a United States post office or mail box, with first class postage

prepaid, addressed to counsel of record at his post office address

“ No motion by a respondent to dismiss a petition for writ of

certiorari will be received. Objections to the jurisdiction of the

court to grant writs of certiorari may be included in briefs in opposi

tion to petitions therefor.”

Petitioners contend that the ordinance requires the sepa

ration of white and colored persons in eating establish

ments.

Assuming such to be true, the propriety of suggesting

the ordinance for the first time in this Court is completely

out of harmony with past decisions of this Court. In the

case of Local No. 8-6, Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers

International Union, AFL CIO v. Missouri, 80 S. Ct. 391,

361 U. S. 363, 4 L. Ed. 2d 373, this Court said, “ Constitu

tional questions will not be dealt with abstractly. * # *

They will be dealt with only as they are appropriately

raised upon a record before us. * * * Nor will we assume

in advance that a State will so construe its law as to bring

it into conflict with the federal Constitution or an act of

Congress.” The foregoing quote was adopted from the

earlier case decided by this Court in Allen-Bradley Local,

etc. v. Wisconsin Employment Relations Board, 315 U. 8.

740, at page 746, 62 S. Ct. 820, at page 824, 86 L. Ed. 1154.

It has been stated under Alabama Supreme Court Rule 1,

Code of Alabama (1940), Title 7, Appendix, in assigning

error on appeal, “ it shall be sufficient to state concisely,

in writing, in what the error consists” .

It has been uniformly held under Alabama Supreme

Court decisions that “ no question is reserved for decision

which is not embraced in a due assignment of error” .

Holle v. Brooks, 209 Ala. 486, 96 So. 341; Swinea v. Flor

ence, 28 Ala. App. 332, 183 So. 686; Crane v. Pearson, 26

Ala. App. 571, 163 So. 821.

This Court has many times repeated its established

doctrine that, “ A decision of a state court resting on

grounds of state procedure does not present a federal ques

tion.” Thorington v. Montgomery, 13 S. Ct. 394, 147 U. S.

490, 37 L. Ed. 252; McNulty v. California, 13 S. Ct. 959,

149 IT. S. 645, 37 L. Ed. 882; O’Neil v. Vermont, 12 S. Ct.

— 6 —

I —

693, 144 U. S. 323, 36 L. Ed. 450; Gibson v, Mississippi, 16

S. Ct. 904, 162 U. S. 565, 40 L. Ed. 1075.

The records before this Court clearly show that peti

tioners have never placed before the state courts the mat

ter of any such ordinance requiring separation of the

races although lengthy and detailed pleadings were inter

spersed throughout all of the student sit-in eases (Gober

et al., now here in No. 694), as well as the instant case.

At best, as argued in the Gober case, the question of

judicial notice by the court below might conceivably find

its way into the controversy.

Bearing in mind that judicial notice is a rule of evidence

rather than a rule of pleading, the suggested ordinance,

to have served some defensive purpose (see Code of Ala

bama (1940), Title 7, Section 225), would of necessity have

had to be incorporated into a plea or answer to the com

plaint. If then, after the supposed ordinance was properly

made an issue in the trial below petitioners sought judi

cial notice by the Court, rules of evidence making it un

necessary to prove by evidence the existence of such an

ordinance would have been entirely applicable. The record

before the Court clearly demonstrates, of course, that pe

titioners did not place the question of such ordinance be

fore the lower court, nor was any assignment of error di

rected to the proposition before the state appellate court.

This question is not a new one for this Court. In the

recent case of Garner v. State of Louisiana, 82 S. Ct.

(1961), Mr. Chief Justice Warren, in delivering this

Court’s opinion, stated, “ There is nothing in the records

to indicate that the trial judge did in fact take judicial

notice of anything. To extend the doctrine of judicial

notice to the length pressed by respondent * * * would be

‘ to turn the doctrine into a pretext for dispensing with a

trial’ ” , citing Ohio Bell Telephone Co, v. Public Utilities

— 8 —

Commission, 301 U. S. 292, 302, 57 S. Ct. 724, 729, 81 L. Ed.

1093. The foregoing opinion further recited the inherent

danger of a court taking upon itself the prerogative of

unsolicited judicial notice in the absence of inserting same

into the record by saying a party, “ * # * is deprived of

an opportunity to challenge the deductions drawn from

such notice or to dispute the notoriety or truth of the facts

allegedly relied upon.”

In light of the Garner opinion, supra, and in light of

the fact that the record discloses nowhere that the court

below, either upon solicitation of counsel or otherwise,

took or refused to take judicial notice of any such ordi

nance, and further, that no assignment of error before

the state appellate court makes any reference whatever

to the existence of such an ordinance, thereby affording

the state appellate court an opportunity to rule on any

question related to the ordinance, your respondent re

spectfully urges that no constitutional or other questions

dependent upon such an ordinance are properly present

able before this Court for review.

ARGUMENT.

Re: Question Presented.

Petitioners submit one question for review (p. 2) by

this Court.

The question is predicated upon the assumption of fact

that “ Alabama has convicted petitioners” for inciting,

aiding or abetting another person to remain upon the

premises of another after being warned not to do so; and

upon the further assumption of fact that there was no

evidence that either of the petitioners “ persuaded anyone

to violate any law” (ibid).

Following the foregoing assumptions of fact, petitioners

present for review the following question:

“ In convicting and sentencing petitioners respec

tively to 180 and 30 days hard labor, plus fines, has

Alabama denied liberty, including freedom of speech,

secured by the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment! ”

The City of Birmingham was the plaintiff in the trial

court below (R. 2). The City handled the prosecution of

the petitioners in the trial court and represented the city

in the appellate courts of Alabama. So far as the record

discloses, and so far as the respondent is aware, the State

of Alabama has never been a party to any phase of this

proceeding nor has the State of Alabama at any time

interceded in the matter in any manner disclosed by the

record. It would therefore appear that the only question

presented to this Court for review is a moot one.

As to the proposition that there was “ no evidence”

(p. 2) to support the conviction of petitioners, your re

spondent is unwilling to concede this to be true.

The testimony offered by respondents in the trial below

was neither disputed by petitioners nor was same sub

jected to any cross-examination (R. 31).

Petitioners present extracts of the testimony below in

Appendix to their petition (pp. 13a-16a). In brief, the

evidence is shown to be as follows: A student (Gober)

went to Rev. Shuttlesworth’s house on March 30th (p.

13a); a student (Davis) went to the house with Rev.

Billups, who came to his school in a car and carried him

there (p. 15a); Rev. Shuttlesworth and Rev. Billups were

both present at Rev. Shuttlesworth’s house (p. 14a); that

there was a meeting in the living room and that Rev.

Shuttlesworth participated in the discussion about sit-

down demonstrations and Rev. Billups was at this meet

ing also (ibid); that when the student (Davis) arrived

at the meeting there were several people there including

— 10

Rev. Shuttlesworth and a number of other students (p.

15a); Rev. Shuttlesworth asked for volunteers to par

ticipate in the sit-down strikes (ibid); a student (Davis)

volunteered to go to Pizitz (a department store in the

Pity of Birmingham) at 10:30 and take part in the sit-

down demonstrations (ibid); that Rev. Shuttlesworth an

nounced at that time that he would get them out of jail

(pp. 15a, 16a); both James Albert Davis and James Gober

did participate in sit-down demonstrations on March 31,

1960, as well as other students who attended the meeting

at Rev. Shuttlesworth’s house on March 30, 1960 (p. 16a).

The foregoing is the evidence contained in the record

before the Alabama Court of Appeals, and in the petition

under consideration.

The opinion of the state court of appeals (pp. la, 2a)

stated (p. 2a), “ A sit-down demonstration being a form

of trespass after warning, denotes a violation of both

State law and especially of Section 1436 of the City Code,

supra. * * * There is a great deal of analogy to the sit-

down strikes in the automobile industry referred to in

National Labor Relations Board v. Fansteel Metallurgical

Corp., 306 IT. S. 240.”

Mr. Chief Justice Warren, in the Court’s opinion in

Garner v. State of Louisiana, 82 S. Ct. 248, 253 (1961),

stated, “ We of course are bound by a state’s interpreta

tion of its own statute and will not substitute our judg

ment for that of the state’s when it becomes necessary to

analyze the evidence for the purpose of determining

whether that evidence supports the findings of a state

court.”

The gravamen of the offense (City Code, Section 824)

charged against petitioners was that petitioners incited,

aided or abetted another to violate the city law or ordi

nance. The law or ordinance which petitioners were

— 11 —

charged with inciting another to violate was Section 1436

of the City Code, which latter section makes it unlawful

to remain on the premises of another after warning not

to do so.

The evident objective of Section 824 of the City Code

was the curtailment of City law violations by making it

unlawful to incite or assist others to violate city laws.

While there has been no occasion for the Alabama ap-

pellate courts to interpret Section 824 of the City’s Code,

a very similar state statute, Section 14 of Title 14, Code

of Alabama, 1940, contains an aiding and abetting statute

very similar to the city’s law, which says in part as fol

lows: “ * * * And all persons concerned in the commission

of a crime, whether they directly commit the act consti

tuting the offense, or aid or abet (emphasis supplied) its

commission, though not present, must hereafter be in

dicted, tried and punished as principals, as in the case of

misdemeanors. ’ ’

The foregoing state statute has been construed by the

state courts on many occasions. Davis v. State, 36 Ala.

App. 573, 62 So. 2d 224, states, “ The words ‘ aid and

abet’ comprehend all assistance rendered by acts or words

of encouragement or support. . . . Nor is it necessary to

show prearrangement to do the specific wrong complained

of.” (Emphasis supplied.)

In Pruett v. State, 33 Ala. App. 491, 35 So. 2d 115, the

court said, “ Aid and abet comprehend all assistance ren

dered by acts or words of encouragement * * citing

Jones v. State, 174 Ala. 53, 57 So. 31, 32.

Alabama has further ruled, “ The participation in a

crime and the community of purpose of the perpetrators

need not be proved by direct or positive testimony, but

may be inferred from circumstantial evidence. ’ ’ Parsons v.

State, 33 Ala. App. 309, 33 So. 2d 164.

While the state statute differs from the city law pri

marily in the fact that the word “ incite” is not found in

the state statute, the net effect of the inclusion of the

word “ incite” in the city law could do no less than

strengthen and enlarge the scope of the city’s law.

The salient features of the state decisions, supra, are

that acts or words of encouragement are sufficient to bring

an offender within the scope of the statute; that it is not

necessary to show prearrangement to do the specific wrong

complained of; and, that the community of purpose may be

inferred from circumstantial evidence.

As to whether there is any evidence in the record to dis

close that petitioners did incite or aid others to violate a

city law, the petition admits in a summary of the evidence

(p. 4), and in appendix (p. 14a), that a meeting was held

at the home of Rev. Shuttlesworth; that Rev. Billups had

driven one student to the meeting and was present during

the meeting (p. 15a), at which meeting other students were

in attendance, and that after one student volunteered to

go to Pizitz at a certain hour, a list was made (ibid). The

sit-downs were discussed at the meeting (p. 14a); Rev.

Shuttlesworth made the announcement “ that he would get

them out of ja il” (p. 16a), and that other students at the

meeting participated in the sit-downs (ibid).

It is most difficult in view of the foregoing evidence to

agree with petitioners’ predicate of fact, upon which they

base their one question for review by this Court (p. 2),

namely, that there was “ no evidence” upon which to rest

the convictions of the petitioners in the trial court below.

Every conceivable element of the offense of inciting the

students to go upon the premises of another and partici

pate in sit-downs is established by the evidence as admit

ted in the petition (supra) and as shown in the record.

The sit-downs were prearranged, volunteers were sought,

and the volunteers were promised they would be released

from jail. No other rational inference could be drawn from

the promise of release from jail than that the volunteers

were to continue their sit-downs on the premises of others

until they were arrested for trespass, for under the re

spondent’s general City Code there was no other punitive

provision in the code under which they could be arrested

and jailed. Petitioners assert the respondent has a segre

gation ordinance, which is copied into their petition as

Section 369 (144) (p. 3), which has already been discussed

here at length, which petitioners say requires restaurant

owners or operators to make certain provisions for sepa

ration of the races in their eating establishments. Cer

tainly the students could not have been arrested under

any such ordinance as this, for, as shown in the petition

(ibid), it only proposes a burden upon the person who

“ conducts” the restaurant and imposes no sanction or pen

alty upon would be customers in the eating establishments.

There is no evidence in the record that the students were

boisterous or obtrusive in their conduct so as to create a

breach of the peace.

The solicitation of Rev. Shuttlesworth for volunteers for

the sit-downs and the promise to get them out of jail

(supra) left the state court no alternate but to reason

ably conclude from the evidence that the sit-down demon

strators were to trespass and be arrested.

In Thompson v, City of Louisville, 80 S. Ct,. 624, 625

(1960), cited by petitioners, this Court said, “ Decision on

this question turns not on the sufficiency of the evidence,

but on whether this conviction rests upon any evidence at

all.”

In view of the evidence above outlined, the attempt by

petitioners to parallel the instant case with the Thompson

case, supra, appears highly incongruous.

It must also be remembered that the same trial court

which rendered judgment against these two petitioners had

—14 —

before it for consideration and the rendition of judgment,

ten cases involving trespasses committed by the sit-down

demonstrators who were counseled by Rev. Shuttlesworth,

all of whom were sentenced together with these petitioners

in a common sentencing proceeding (R. 35-39). The ten

cases (Gober et al., now here in No. 694), involving tres

pass after warning, together with the two instant cases,

all involved common counsel and developed out of near

identical circumstances occurring in different stores. If,

indeed, the trial court had no knowledge or concept of the

meaning of the term “ sit-down demonstration” , after hav

ing just completed hearing ten cases involving nothing but

“ sit-down” cases, it would of necessity have to be assumed

that the trial judge was something more than naive. In

context with the promised release from jail (pp. 4, 15a,

16a), there was only one inescapable interpretation which

the trial court could place upon the term “ sit-down dem

onstrations” and that was—a device of remaining on an

other’s premises after being told to leave, as in Fansteel,

supra.

Not to be overlooked is the matter of how the question

of the sufficiency of the evidence was raised in the state

court. Petitioners’ motion to exclude the evidence, ground

No. 4 (R. 6), in attacking the sufficiency of the evidence,

alleged as follows:

“ 4. The evidence against the defendant, a Negro,

in support of the charge of his violation of 824 the

General City Code of Birmingham of 1944, clearly in

dicates (emphasis supplied) that those persons al

leged to have acted as a result of the aiding and abet

ting of the defendant, had accepted an invitation to

enter and purchase articles in the various department

stores in the City of Birmingham, stores open to the

public, but had not been allowed to obtain food service

on the same basis as that offered white persons, be

cause of their race or color; and, that in furtherance

of this racially discriminatory practice of the various

department stores (emphasis supplied) in the City of

Birmingham, the defendant was arrested. * * *”

In the foregoing motion to exclude the evidence (R. 6),

which motion is not reviewable by the state appellate

court, Dudley Brothers Lumber Company v. Long, 109

So. 2d 684, 268 Ala. 565, the petitioners themselves have

interpreted the evidence in the trial below as being in

clusive of the activities of the demonstrators in the de

partment stores, in adopting the language (R. 6), “ The

evidence against the defendant(s), a Negro, in support

of the charge of violation of 824 the General City Code

of Birmingham of 1944, clearly indicates (emphasis sup

plied) that those persons alleged to have acted as a re

sult of the aiding and abetting of the defendant(s) had

accepted an invitation to enter and purchase articles in

the various department stores * * etc., and proceeds

then to state that because of the discrimination of the

“ various department stores” the defendants were subse

quently arrested (ibid).

In conclusion, on the subject of whether there was “ any

evidence” , Garner and Thompson, supra, to support the

state court’s finding of guilt, your respondent strongly

urges that every element of the offense of violating Section

824 of the General City Code of Birmingham of 1944 has

been more than adequately substantiated by the evidence

presented below as shown in the record and petition.

To hold that there was no evidence, as contended by

petitioners, to support the conviction would, as stated by

Mr. Justice Harlan in Garner v. State of Louisiana, 82 S. Ct.

248, 265, “ * * * in effect attribute(s) to the (Louisiana)

Supreme Court a deliberately unconstitutional decision

* # * ? ?

— 16

ARGUMENT.

Re: Petitioners’ Reasons for Granting- the Writ.

Petitioners’ argument concerning reasons for granting

the writ should, of course, be confined to their “ Question

Presented” (p. 2) for the review of the Court, the sub

stance of which is, “ * * * has Alabama denied liberty,

including freedom of speech, secured by the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment f ”

For very obvious reasons, petitioners have not elabo

rated upon the rights of property owners as guaranteed

under the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Con

stitution.

Petitioners concede that the doctrine of free speech

protection has many limitations and cite well known au

thority in support thereof (p. 7), perhaps the most famous

of which is Schenck v. United States, 249 U. S. 47. As

the Court well knows, the defendant in this case was con

victed for mailing circulars during World War I, which

circulars were found to be detrimental to this country’s

war effort. On the circular, among other things, were the

words, “ Assert Your Rights” , and described arguments

in support of the war effort “ as coming from cunning

politicians.” The right of free speech was not upheld by

this Court because a danger to the substantive rights of

others was involved.

In the instant cases, petitioners claim they were assert

ing their rights in seeking volunteers to test the sub

stantive rights of private property owners, or, as they

express it, to perform “ sit-down demonstrations” (p. 8),

which are commonly known to be a sitting upon the

premises of another and refusing to leave until they

become trespassers and are arrested. Rev. Shuttles-

■— 17

worth’s promise to free the demonstrators from jail con

clusively establishes this fact. Attention is also invited

to this fact as borne out in the ten cases involving* the

demonstrators now here in Gober, et al., before the Court

under No. 694. The demonstrators in Gober (Parker, R.

21; West, R. 18) said “ they were not going* to leave” ; a

demonstrator (Gober, R. 39; Davis, R. 40) was quoted as

saying “ they were instructed to go into the store and sit-

down at a white lunch counter, and that they would

probably be or would be asked to leave, and not to leave

but remain there until the police arrested them and took

them out” ; an assistant store manager (Parker, R. 23;

West, R. 20) quoted demonstrators as saying, “ We have

our rights,” when told to leave.

The inciting* of this type of demeanor is what petitioners

refer to as “ constitutionally protected free expression”

(p . 1 0 ) .

This Court made it clear in Martin v. Struthers, 319

IT. S. 147, 63 S. Ct. 862, 87 L. Ed. 1313, that, “ Tradition

ally the American law punishes persons who enter onto

the property of another after having been warned to keep

off.”

In Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707, it is clearly stated

that individuals may elect persons with whom they will do

business unimpaired by the Fourteenth Amendment.

The case of Williams v, Howard Johnson, 268 F. 2d 845,

states clearly that restaurants not involved in interstate

commerce are “ at liberty to deal only with such persons

as it may elect.”

In the case of Bullock v. U. S., 265 F. 2d 683; cert, denied

79 S. Ct. 1294, 1452, 360 U. S. 909, 932, 3 L. Ed. 2d 1260;

rehearing denied, 80 S. Ct. 46, 361 U. S. 855, 4 L. Ed. 2d 95,

it was emphasized that, “ The right of free speech is not

absolute and this amendment to the Federal Constitution

does not confer the right to persuade others to violate the

law.” (Emphasis supplied.)

The evident intent in the meeting sponsored and par

ticipated in by Rev. Billups and Rev. Shuttlesworth was

to determine whether private ownership and control of

property was to endure in this country or whether the

power of a large minority political block could overrule

this traditional heritage of a free enterprise system.

Protection of one’s property under the Fifth and Four

teenth Amendments are “ substantive” rights and any

threat to this substantive right presents a “ clear and

present danger,” Schenck v. United States, supra.

Whatever may or may not be morally right in the use

of one’s own property, sit-down demonstrations have no

place there if not consented to by the owner, as stated in

Garner, snpra, in the opinion delivered by Mr. Justice

Harlan; and whether the act involves racial intolerance,

prejudice or bias is not of concern under the Fourteenth

Amendment, where the property is private. See Mr. Jus

tice Douglas’ concurring opinion in Garner, supra.

In conclusion, and for the foregoing reasons, it is re

spectfully submitted that the petition for writ of certio

rari should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

WATTS E. DAVIS,

WILLIAM C. WALKER,

M r

EARL McBEE,

600 City Hall Building,

Birmingham, Alabama,

Attorneys for Respondent.

19 —

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

OCTOBER TERM, 1961.

F. L. SHUTTLESWORTH and CHARLES

BILLUPS,

Petitioners,

vs.

CITY OF BIRMINGHAM,

Respondent.

Certificate of Service.

I, Earl McBee, one of the Attorneys for Respondent,

City of Birmingham, and a member of the Bar of The

Supreme Court of the United States, hereby certify that

on the . & . day of March, 1962, I served a copy of Brief

on behalf of respondent to Petition for Writ of Certiorari,

in the above styled and numbered cause, on Jack Green

berg and on Constance Baker Motley, Attorneys for

Petitioners, by depositing the same in a United States Post

Office or mail box, with air mail postage prepaid, ad

dressed to them at their post office address, namely, 10

Columbus Circle, New York 19, New York; and on the

following respective Attorneys of Record for Petitioners

whose addresses are known to Respondent by depositing

the same in a United States Post Office or mail box, with

first class postage prepaid, addressed to Arthur D. Shores,

1527 5th Avenue, North, Birmingham, Alabama; Orzell

Billingsley, Jr., 1630 4th Avenue, North, Birmingham,

Alabama; Peter A. Hall, Masonic Temple Building, Bir

mingham, Alabama; Oscar W. Adams, Jr., 1630 4th

Avenue, North, Birmingham, Alabama; and J. Richmond

Pearson, 415 North 16th Street, Birmingham, Alabama.

...............

Earl McBee,

Attorney for Respondent.

V No. 721.

DRZF LT BILLINGSLEY,

ATTORNEY AT LAW

3510-514 MASONiC BLDG&

JE3Q » 4th AVENUE NORTH'

BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA