Lee v. Talladega County Board of Education Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

December 16, 1988

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lee v. Talladega County Board of Education Brief for Appellants, 1988. 17538bf8-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4cf82f5f-6d85-4fde-b66d-5182cfef2240/lee-v-talladega-county-board-of-education-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

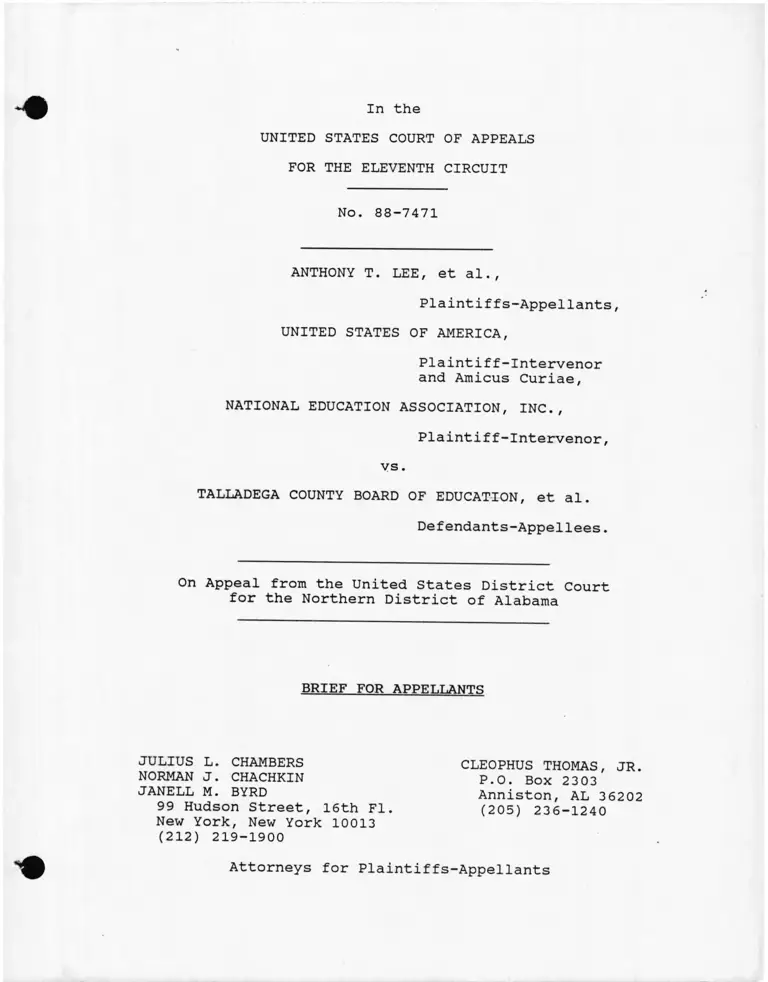

In the

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 88-7471

ANTHONY T. LEE, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

NATIONAL EDUCATION ASSOCIATION, INC.,

Plaintiff-Intervenor,

v s .

TALLADEGA COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Alabama

Plaintiff-intervenor and Amicus Curiae,

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN CLEOPHUS THOMAS, JR. P.O. Box 2303

Anniston, AL 36202 (205) 236-1240

JANELL M. BYRD

99 Hudson Street, 16th FI.

New York, New York 10013 (212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

Pursuant to Eleventh Circuit Rule 28-2(b) the undersigned

counsel of record certifies that the following is a complete list

of all trial judges in the proceedings in Lee v. Macon Countv

Board of Education, Civ. No. 604-E (M.D. Ala.)(state-wide case)

and Lee v. Macon County Board of Education. No. 70-AR-0251-S

(N.D. _ Ala.) (Talladega County), and of all attorneys, persons,

associations of persons, firms, partnerships, or corporations

that may have an interest in the outcome of these proceedings:

Hon. Frank M. Johnson, Jr.; Hon. William M. Acker, Jr.; Hon. Sam C. Pointer, Jr.; Hon. H.H. Grooms; Hon. Virgil Pittman; and Hon. James H. Hancock (trial judges).

Anthony^ T. Lee, Henry A. Lee, Detroit Lee, Hattie M. Lee,

Palmer Sullins, Jr., Alan D. Sullins, Marsha Marie Sullins,

Palmer Sullxns, Della D. Sullins, Gerald Warren Billes, Heloise

Elaine Billes, I.V. Billes, Willie M. Jackson, Jr., Mabel H.

Jackson, Willie B. Wyatt, Jr., Brenda J. Wyatt, Willie B. Wyatt,

Thelma A. Wyatt, Nelson N. Boggan, Jr., Nelson Boggan, Sr., Mamie

Boggan, Willie C. Johnson, Jr., Brenda Faye Johnson, Dwight W. Johnson, Willie C. Johnson, Ruth Johnson, William H. Moore,

Edwina M. Moore, L. James Moore, Edna M. Moore, Robert Judkins^

Jr., Willie_ B. Wyatt, Jr., Patricia Jones, Shelby Chambliss,

Carmen Judkins, Janice Carter, Ellen Henderson, Harvey Jackson,

Wilmar Jones, John W. Nixon, Alabama State Teachersf Association,

National Education Association, Alabama Interscholastic Athletic

Association, Quintin Elston, Rhonda Elston, Tiffanie Elston,

Augustus Elston, Cardella Elston, Ernest Jackson, Rayven Jackson^

Rollen Jackson, Helen Jackson, Wendell Ware, John W. Ware*

Jeffery Morris, Lela Morris, Vernon Garrett, Estella Garrett,'

Delicia Beavers, _Loretta Beavers, Dorothy Beavers, Carla Jones' Paul Jones, Willie Jones, Bertha Jones, Lecorey Beavers, Ronnie

Beavers, Stephanie Y. Hill, Connally Hill, Jacgues Turner,

William Tuck, Jr., Veronica Tuck, Danielle Jones, Donald Jones\

Torrance Beck, Albert Beck, Jr., Quinedell Mosley, Quinell

Mosley, Kereyell_Glover, Delilah Glover, Tiffani Swain, Kedrick

Swain, Terry Swain, Donyae Swain, Gwendolyn Swain, Darius Ball,

Kierston Ball, Gwynethe Ball, Damien Garrett, Althea Garrett^

Tonya Shepard, Mary Alice Jemison, Cora Tuck, Louise Tuck, Jerrk

Evans, Kate Evans, Montina Williams, Richard Williams, Angie

Williams, Roslyn Cochran, Johnnie Cochran, Quinton Morris, Datrea Morris, Torry Morris, Willie Morris.

Macon County Board of Education, Wiley D. Ogletree, Madison

Davis, John M. Davis, Harry D. Raymon, F.E. Guthrie, C.A. Pruitt,

B.O. Dukes, John M. Davis, Joe C. Wilson, Governor George C.

Wallace, Alabama State Board of Education, Alabama High School

Athletic Association, Austin R. Meadows, James D. Nettles, J.T.

Albritton, J.P. Faulk, Jr., Fred L. Merrell, W.M. Beck, Victor P.

Poole, W.C. Davis, Cecil Ward, Harold C. Martin, Governor Lurleen

1

Burns Wallace, Governor Albert Brewer, Ernest Stone, Ed Dannelly,

Mrs. Carl Strang, Talladega County Board of Education, J. R.

Pittard, Jim Wallis, C.L. Hall, E.C. Hutto, A.O. Riser, M.R.

Watson, Lance Grissett, Kenneth Armbrester, M. R. Watson, Gay Langley, Joseph Pomeroy, Larry Morris, Dan Limbaugh.

Jack Greenberg, Constance Baker Motley, Norman Amaker, Leroy

D. Clark, Charles H. Jones, Charles Stephen Ralston, Melvyn Zarr,

Henry Aronson, Fred Gray, Solomon S. Seay, Julius L. Chambers,

Norman J. Chachkin, Janell M. Byrd, Oscar W. Adams, Jr., Robert

L. Carter, Cleophus Thomas, Jr., Reid & Thomas, Donald V.

Watkins, Gray, Seay & Langford, Gray, Seay, Langford & Pryor, Howard Mandell, Frank D. Reeves.

Richmond M. Flowers, MacDonald Gallion, Robert P. Bradley,

Gordon Madison, Goodwyn & Smith, Goodwyn, Smith & Bowman, James

T. Hardin, Hugh Maddox, John C. Satterfield, Maury D. Smith,

Nicholas S. Hare, Ralph D. Gaines, Jr., George C. Douglas, Jr. \

Ralph D. Gaines, III, Gaines, Gaines & Gaines, Hill, Hill'

Stovall & Carter, Hill, Hill, Whiting & Harris, Hill, Robinson[

Belser & Phelps, Steiner-Crum & Baker, Rushton, Stakely &

Johnston, John C. Satterfield, Satterfield, Shell, Williams, &

Buford, Martin Ray, McQueen, Flowers & Ray, Orzell Billingsley

David H. Hood, Oakley Melton, T. W. Thagard, Jr., Charles m !

Crook, Alabama Education Association, Hon. Truman M. Hobbs Hobbs, Copeland, Franco, Riggs & Screws. '

United States of America, Ben Hardeman, St. John Barrett,

David L. Norman, Alan G. Marer, Brian K. Landsberg, Charles S.

Bentley, James C. Foy, John Doar, Kenneth Franklin, James Taylor

Hardin, J. Mason Davis, Peter A. Hall, Pauline Miller, John

Moore, William Bradford Reynolds, Roger Clegg, Frank W.

Donaldson, Caryl Privett, Ramsey Clark, John Mitchell, Alexander C. Ross, Reuben Ortenberg, Frank D. Allen, Stephen J. Poliak

Charles Quaintance, Alexander C. Ross, Ira DeMent, Jerris

Leonard, Robert Pressman, Joseph D. Rich, Angela Schmidt, Dennis J. Dimsey, Thomas E. Chandler.

11

Statement Regarding Oral Argument

Pursuant to Eleventh Circuit Rule 28-2(c), plaintiffs-

appellants request oral argument because the issues raised by

this appeal are of substantial public importance and may recur in

other school desegregation cases pending in this Circuit.

Certificate of Interested Persons .................... i

Statement Regarding Oral Argument .................... iii

Table of Contents ..................................... j_v

Table of Authorities ............................... . v

Jurisdiction .......................................... ^

Issues Presented for Review ................. ........ 2

Statement of the Case ....................... ......... 2

Procedural History ................ . 2

Relevant Facts ......................... . 6

Scope of Review ....................... .............. . 9

Summary of Argument ......................... 10

1 • ........ 10

11 ........................................ ............. 10

1 1 1 .......................................... 11

ARGUMENT

Introduction .......................... 12

I The District Court Erred In Refusing To

Reopen The Litigation And To Enforce The

Terms Of The 1985 Settlement Agreement

Which It Had Approved As The Basis ForDismissal Of This Action ....... 13

II The District Court Erred In Ruling That It Was Without Jurisdiction To

Entertain The Motion To Reopen ..... is

III The District Court Eerred In Ruling

That Plaintiffs-Appellants Could Not Reopen The Case Pursuant To Fed. R. Civ. P.60 (b) (5) or (b)(6) 21

CONCLUSION ....... .......... . 00

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

*Aro Corporation v. Allied Witan Company, 531 F.2d

1368 (6th Cir.), cert, denied. 429 U.S.

862 (1976) 20

Berman v. Denver Tramway Corporation, 197 F.2dF. 2d 946 (10th Cir. 1952) ....................... 21

Bonner v. Prichard, 661 F.2d 1206 (11th

Cir. 1981 (en banc) ............................. 2.9

C & C Products, Inc. v. Messick, 700 F.2d 635(11th Cir. 1983) 6

Cathbake Investment Company v. Fisk Electric

Company, 700 F.2d 654 (11th Cir. 1983) .......... 9

Combs v. Ryan's Coal Company, 785 F.2d 970 (11th

Cir.), cert, denied. 107 S.Ct. 187 (1986) ..... . 9

*D.H. Overmyer Company v. Loflin, 440 F.2d 1213

(5th Cir.), cert, denied. 404 U.S. 851(1971) .......................................... . 14

*Dowell v. Board of Education of Oklahoma City,

795 F.2d 1516 (10th Cir.), cert, denied.

107 S.Ct. 420 (1986) ................... .......... 11,19

*Fairfax Countywide Citizens Association v.

County of Fairfax, 571 F.2d 1299 (4th Cir.),

cert, denied. 439 U.S. 1047 (1978) ...... ........ 17,20

Georgia State Conference of Branches of NAACP

v. Georgia, 775 F.2d 1403 (11th Cir. 1985) ...... 25

Humble Oil & Refining Company v. American

Oil Company, 405 F.2d 803 (8th Cir. 1969) ....... 24

Joy v. Manufacturing Company v. National Mine

Service Company, 810 F.2d 1127 (Fed. Cir.

1 9 8 ? ) .............................. ............................... 21

*Lee v. Hunt, 631 F.2d 1171 (5th Cir. 1980). cert.

denied. 454 U.S. 834 (1981) ..................... 11,19

Page

v

Page

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 267 F. Supp.

458 (M.D. Ala.) (3-judge court), aff'd sub nom.

Wallace v. United States, 389 U.S. 215(1967) ........................................... 6

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 448 F.2d 746(5th Cir. 1971) .................................. 3

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education (Nunnelley

State Technical College), 681 F. Supp.

730 (N.D. Ala. 1988) ............................ 16,26

Local Number 93, International Association of

Firefighters v. City of Cleveland, 478

U.S. 501 (1986) 14,17,19

*Meetings and Expositions, Inc. v. Tandy Corp.,

490 F. 2d 714 (2d Cir. 1974) ..................... 20

Monteilh v. St. Landry Parish School Board, 848

F.2d 625 (5th Cir. 1988) ............... . 25

Morgan v. Roberts, 702 F.2d 945 (11th Cir. 1983) ...... 6

*Paradise v. Prescott, 767 F.2d 1514 (11th Cir.

1985), aff'd, 107 S.Ct. 1053 (1987) .... .........9,14,17,19

*Pasadena City Board of Education v. Spangler,

427 U.S. 424 (1976) 11,27

Pearson v. Ecological Science Corporation, 522 F.2d

171 (5th Cir. 1975), cert, denied. 425 U.S. 912 (1976)................................. 14

Riddick v. School Board of Norfolk, 784 F.2d 521 (4th Cir.), cert, denied. 107 S.Ct.

420 (1986) ........................................... . i7

Ridley v. Phillips Petroleum Company, 427 F.2d

19 (10th Cir. 1970) 24

Theriault v. Smith, 523 F.2d 601 (1st Cir.

1975) 22,25

Turner v. Orr, 759 F.2d 817 (11th Cir. 1985) ......... 10

United States v. Board of Education of Jackson

County, 794 F.2d 1541 (11th Cir. 1986) .......... 17,25

- vi

Page

United States v. City of Miami, 664 F.2d 435

(5th Cir. 1981) (en banc) ........................ 14,19

United States v. Georgia, 691 F. Supp. 1440

(M. D. Ga. 1988) ................................ . 25

*United States v. Georgia Power Company, 634 F.2d

929 (5th Cir. [Unit B] 1981), vacated on other

grounds, 456 U.S. 952 (1982), original opinion

affirmed and reinstated. 695 F.2d 890

(5th Cir. 1983) .............................. ...10,11,24,27

United States v. Lawrence County School District,

799 F. 2d 1031 (5th Cir. 1986) ............. . 25

United States v. Overton, 834 F.2d 1171 (5thCir. 1987) 17

United States v. Swift & Company 189 F. Supp. 885

(N.D. 111. 1960), aff'd per curiam. 367

U.S. 909 (1961) 24

United States v. Timmons, 672 F.2d 1373 (11thCir. 1982) 23

Westmoreland v. National Transportation Safety

Board, 833 F.2d 1461 (11th Cir. 1987) ...... . 5

W.J. Perryman & Company v. Penn Mutual Fire

Insurance Company, 324 F.2d 791 (5th Cir.1963) ........................................... . 14

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 1291 ........................... x

28 U.S.C. § 1343 (3) ±

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ................................. 1

Rules and Regulations:

Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(1).............................. 23

Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(2).............................. 23

Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(2).............................. 23

- vii -

*Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(5) .................. 2,11,21, 22, 23, 24,

*Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(6) ....................2,11,20,21,22,23,24

Eleventh Circuit Rule 28-2(b) .................... .

Eleventh Circuit Rule 28-2(c) ........................

Other Authorities;

C. Wright & Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure (1973) ................................ .

* Indicates authorities primarily relied upon.

27.28

27.28

i

iii

24

Page

- viii

In the

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 88-7471

ANTHONY T. LEE, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor and Amicus Curiae,

NATIONAL EDUCATION ASSOCIATION, INC.,

Plaintiff-Intervener,

vs.

TALLADEGA COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Alabama

BRIEF FOR APPET.TAWTS

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction in the district court was invoked pursuant to

28 U.S.C. § 1343(3) and 42 U.S.C. § 1983. Jurisdiction over this

appeal is established pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1291. On July 25,

1988, the district court issued its opinion and entered final

denying plaintiffs—appellants' motion to reopen the case

and attendant motions (Rl-1; Rl-2; Rl-3; Rl-7). Timely notice of

appeal was filed on July 29, 1988 (Rl-9).

Issues Presented for Review

The issues presented by this appeal are as follows:

1. Whether a district court may refuse to implement the

explicit terms of its own order approving dismissal of a case

pursuant to a settlement agreement.

2. Whether, after dismissal of an action pursuant to a

court-approved settlement agreement, a district court has

inherent authority to enforce the agreement.

3. Whether a final order of dismissal should be set aside

pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(5) or (6) (so as to allow

enforcement of a settlement agreement) if the district court

has, since approving the agreement and dismissing the action

according to its terms, changed its view of the applicable law

regarding the settlement agreement's enforceability.

Statement of the Case

Procedural History

This appeal involves the Talladega County, Alabama school

system1 and is part of the state-wide class action, Lee v. Macon

County Board of Education, commenced in 1963 to challenge racial

By Order of this Court on December 1, 1988, thisappeal was consolidated with appeals No. 88-7551, 88-7552, and

88-7553. The Court instructed that separate briefs could be

and because of the uniqueness of this appeal it' is separately presented.

2

segregation and discrimination in the public schools of the State

of Alabama. A three-judge court in the late 1960's and early

1970's entered injunctive orders, including desegregation orders

for each jurisdiction covered by the litigation. In most

instances, after detailed desegregation orders had been

implemented for a period of several years, the district court2

entered findings that each of the districts were operating "a

unitary school system,"3 substituted general permanent

injunctions for the detailed orders, and placed the cases on the

inactive docket.

The Talladega County School System, however, had significant

ongoing litigation and continued to operate under its detailed

desegregation plan, as modified over the years. On March 13,

1985, the district court endorsed as "Approved" and "Entered" a

Joint Stipulation of Dismissal agreed to by all parties.4

Incorporated in that Joint Stipulation was the Resolution of the

Talladega County Board of Education, which states that the

"Talladega County System shall be operated at all times so as to

conform with . . . all previous orders of [the District] Court"

and commits the school system "to adopt, maintain and implement

2 By this time, the cases involving the individual school systems throughout the state had been transferred from the three-

judge^ court to the respective federal judicial districts and

divisions throughout Alabama and assigned to individual judges.

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education. 448 F.2d 746 748 n 1(5th Cir. 1971).

3 See, e^g., lSR-29-Exhs. F, G, and H at 1.

lSR-29-Exh. D, Joint Stipulation of Dismissal.

3

affirmative action programs designed to improve racial

integration among students, faculty and administrative staff of

the School System."5

A separate Judgment and Order6 was issued on the same date.

It dismissed the case "in view of" the Joint Stipulation of

Dismissal and recited that the school district had achieved

"unitary status." Neither the Joint Stipulation nor the

Judgment and Order provided that prior court orders were to be

vacated or dissolved.

On July 22, 1988, plaintiffs, seeking to enforce the orders

which they believed defendants were violating, filed a "Motion to

Reopen, and Motions for Preliminary Injunction and for an Order

Directing Compliance With Outstanding Court Orders" [referred to

hereafter as "Motion to Reopen"]; a Motion for Expedited

Discovery; a Motion to Add Parties; and discovery requests (Rl-

i' Rl~2; Rl-3; Rl-4; Rl-5; Rl-6). On July 25, 1988, the district

court summarily denied all of plaintiffs' motions. It stated

that there were no residual injunctive orders to enforce

following dismissal of the case in 1985, and that there was no

retention of jurisdiction which would permit the court to reopen

the case or to grant relief from the order of dismissal (which

the district court now interpreted to have ipso facto

extinguished all prior orders in the case); the court stated that

5 lSR-29-Exh. D, Resolution at 23.

zT lSR-29-Exh. D, Judgment and Order. The district court

judge described this separate judgment issued pursuant to Fed.' R. Civ. P. 54 as a "redundancy" (Rl-ll-l).

4

plaintiffs could challenge the school board's actions only by

filing a new lawsuit (Rl-7).

On July 29, 1988, plaintiffs noticed this appeal and moved

in the district court for an injunction pending appeal (Rl-9;

Rl-10). On July 30, 1988, (order entered August 1, 1988), the

district court denied this request, stating that inasmuch as it

had held on July 25, 1988, that it was without jurisdiction to

entertain an "untimely post-judgment motion," the court also was

without jurisdiction to consider a motion for an injunction

pending appeal. The district court elaborated upon the basis for

its July 25 ruling by stating that the dismissal order entered in

1985 "necessarily meant" that there are no outstanding court

orders applicable to the Talladega County Board of Education

(Rl-11). On August 8, 1988, plaintiffs filed an Emergency Motion

for Injunction Pending Appeal in this Court. That motion was

denied by an order dated November 3, 1988.^

In order to protect plaintiffs' substantive rights, following the denial of the Motion for Injunction Pending Appeal

m this Court, plaintiffs-appellants have filed a new lawsuit and

a motion for preliminary injunction against the proposed new

school construction. If this Court reverses the district court

order with respect to reopening, we will seek to consolidate these two actions in the district court.

On December 12, 1988, plaintiffs-appellants received theMotion of Talladega County Board of Education to Dismiss Appeal

as Moot. We will set out fully in our opposition to that motion,

which will be_filed shortly, the reasons why there remains a live

controversy in this action and the appeal should not be

dismissed. The short answer to the Board's contention is that

until such time as there is a ruling in the new suit which makes

it impossible for this Court to grant effective relief to

appellants, the pending appeal is not moot. See, e.o.

Westmoreland_v. National Transportation Safety Board. 833 F.2d

(continued...)5

Relevant Facts

Plaintiffs alleged, in support of the Motion to Reopen,

that Talladega County school officials were violating prior court

orders prohibiting them from discriminating against black school

children on the basis of race, Lee v. Macon Countv Board of

Education, 267 F. Supp. 458, 480 (M.D. Ala.) (3-judge court),

'd sub nom. Wallace v. United States. 389 U.S. 215 (1967),

requiring the assignment of students to schools based on

specified attendance zones, and requiring the Board of Education

to adopt affirmative action plans to integrate faculty and staff

(Rl-1-2).

Specifically, plaintiffs alleged that defendants' plan to

construct a new elementary school on property adjacent to the

site of the historically white Idalia School, and thereafter to

close all or a portion of the historically black Talladega

County Training School, is part of a racially discriminatory

pattern of closing historically black schools in order to avoid

assigning white students to them.® This practice, plaintiffs 7

7 (...continued)

1461, 1462 (11th Cir. 1987); Morgan v. Roberts. 702 F.2d 945

946-47 (11th Cir. 1983); C & C Products. Inc, v. Messick. 7nnF.2d 635, 637 (11th Cir. 1983).

In 1970 the Board of Education frankly told the district court that its key problem in devising a desegregation

plan wap the size of the black population, which would require that white students be assigned to black schools:

I am sure you realize that the implementation of a plan

to abolish the dual school system is more difficult in

some school systems than in others because of the

racial composition of the school system. It is

(continued...)

6

asserted, devalues the black citizens of the County by

systematically eliminating, downgrading, or limiting the schools

in the black community or those with historical connections to

blacks, although white citizens and the white community have not

been treated similarly (Rl-1).

In 1970, when the Talladega County desegregation plan was

approved by the district court, eight8 9 of the twenty schools in

the system were maintained as separate schools for black school

children: Charles R. Drew (1-9), Hannah Mallory (1-6), Mignon (1-

6), Nottingham (1-6), Ophelia S. Hill (1-12), Phyllis Wheatley

8 (...continued)

anticipated that the implementation of the plan in the

Talladega County School System will be difficult

because of the size of our Negro population.

Implementation of the plan in the Talladega County

School System will require us to send white students to

all Negro schools with the exception of one school.

Our problem is further intensified by the fact that of

the five county school systems bordering this county,

it will not be necessary for four of these systems to

send white students to Negro schools. I hope,

therefore, that you will have some understanding of our situation and of the problems involved.

(Plaintiffs' Exhibit A. [Plaintiffs' Exhibits, which are part of the record on appeal, will be referred to hereinafter as "PX."])

In addition, when the Idalia Elementary School, which had a student population over 50% white (PX-C-18) burned down

approximately two years ago, the Board of Education decided to

house the Idalia children in trailers rather than send them to

the historically black Talladega County Training School, which

had space available and was about a five-minute ride away. CSee

PX-B [Composite Facilities Report attached to Talladega County-

Desegregation Plan] for capacities; PX-C for 1984 school

enrollments.) The Idalia students have remained in trailers since their school burned down (Rl-1-6).

9 Plaintiffs alleged that prior to 1970, the Board of

Education had closed five historically black schools: Pine Hill,

Sweet Home, Lane Chapel, Union Springs, and Hall Grove (Rl-1-4)/

7

(1-9), R. R. Moton (1-9), and the Talladega County Training

School (1-12) (PX-B-9,10). Since 1970, the Board of Education

has closed outright four of these eight schools: Mignon (1972),

Nottingham (1974), Hannah J. Mallory (1985), and Phyllis Wheatley

(1988). The Board also has closed parts of three other

historically black schools: grades 7-12 at the Ophelia S. Hill

School, grades 1-4 and 9 at the Charles R. Drew School, and grade

9 at the R.R. Moton School (named for a black person), which the

board had also redesignated as the Sycamore School (PX-B-9, 10;

PX-C-17, 18). Today, the only historically black school

remaining unaltered in grade structure or name is the Talladega

County Training School, which serves grades K-12 (Rl-1-4).

Plaintiffs alleged, and defendants admitted, that the

Talladega County Board of Education intends to build a new, 500-

pupil elementary school adjacent to the former site of the

Idalia Elementary School, to close the elementary section of the

County Training School, and to close the Jonesview Elementary

School (the Training School's only remaining feeder school10).

Rather than having the new facility feed the Training School, the

Board of Education plans to give students completing the sixth

grade at the new school "freedom of choice" for the secondary

grades (Rl-1-5).11

10 In 1985, the Board closed the other feeder school to the Training School — Hannah Mallory Elementary School (Rl-l- 6 ) .

Under the proposed plan, it is clear that the very existence of the Training School is in jeopardy. Closing the

(continued...)

8

Plaintiffs also alleged that since dismissal of the case in

1985, defendants have adopted a new student transfer policy that

circumvents the attendance zone plan ordered by the court and

which will facilitate white students' avoidance of historically

black schools (Rl-1-6,7), and they challenged defendants' failure

to comply with the promise to adopt affirmative action plans.12

Scope of Review

The first and second issues set out above present guestions

of proper application or formulation of the law and therefore are

subject to independent review by this Court. See Combs v. Ryan's

Coal Company, 785 F.2d 970, 976 (11th Cir.), cert, denied. 107 S.

Ct. 187 (1986), citing Cathbake Investment Company v. Fisk

Electric— Company, 700 F.2d 654, 656 (11th Cir. 1983). Appellate

review of a district court's construction of a consent decree is

a question of law subject to de novo review. See Paradise v.

Prescott, 767 F.2d 1514, 1525 (11th Cir. 1985), aff'd. 107 S. Ct. 11 12

11(...continued)

elementary division of the County Training School and Jonesview

(the latter school, as of 1984, enrolled a total of only 158

students) (PX-C-18), and adopting a "free choice" plan with

respect to attendance at the Training School on the secondary level, is likely to result in there being few -- and almost

certainly no white -- students enrolled in its upper grades.

This can readily be seen in the pattern of white secondary

attendance following completion of the sixth grade at Jonesview

Elementary School. in 1984, Jonesview had 70 white students

(44% of its enrollment), while the County Training School for

that year had only 13 white students (3% of enrollment) (PX-C-

18) -- suggesting that whites, for the most part, do not attend

the Training School after completion of the sixth grade at Jonesview.

12 Rl-l-9. Plaintiffs repeatedly requested a copy of the

Board s affirmative action plans. None were ever provided I'RT—i — 9; PX-L; PX-D). v

9

1053 (1987), citing Turner v. Orr. 759 F.2d 817, 821 (11th Cir.

1985) . The third issue is reviewed under an "abuse of

discretion" standard. See United States v. Georgia Power

Company, 634 F.2d 929 (5th Cir. [Unit B] 1981), vacated on other

grounds, 456 U.S. 952 (1982), original opinion affirmed and

reinstated. 695 F.2d 890 (5th Cir. 1983).

Summary of Argument

I

The district court erred in failing to adhere to the terms

of its own order — the Joint Stipulation of Dismissal, which

the court specifically approved and entered. The Joint

Stipulation clearly contemplated the continued existence of the

court orders as well as specifically providing a new

commitment by defendants to obey them. The district court never

vacated nor dissolved any of these orders, nor did it find them

unenforceable for any reason except the 1985 dismissal of the

lawsuit. The district court was not free to ignore these orders

when plaintiffs sought to reopen the case in order to enforce

them.

II

The district court's perception that it lacked jurisdiction

even to entertain the motion to reopen, and a fortiori to reopen

the case, is clearly in error. Federal courts retain the

inherent power to enforce injunctive decrees and court-approved

agreements entered into in settlement of litigation, either in

10

supplemental proceedings in the same case or in a separate

ancillary proceeding, notwithstanding whether the original

action was closed or dismissed after entry of the initial relief.

See, e. q. , Dowell v. Board of Education of Oklahoma Citv. 795

F•2d 1516 (10th Cir.), cert, denied. 107 S.Ct. 420 (1986); Lee v.

Hunt, 631 F. 2d 1171 (5th Cir. 1980), cert, denied. 454 U.S. 834

(1981).

Ill

Assuming arguendo that the district court lacked the

inherent equitable authority to enforce the terms of the Joint

Stipulation, it erred in refusing to vacate the dismissal order

pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(5) and (b)(6). This Court held

in United States v. Georgia Power Company. 634 F.2d 929, 934 (5th

Cir. [Unit B] 1981), that Rule 60 applies where there has been a

"significant modification in decisional law" upon which a final

judgment was based. Here the district court's 1988

interpretation of the law governing the effect of a dismissal in

a school desegregation case upon the vitality of prior decrees in

the case which were never explicitly vacated -- an interpretation

which it applied to plaintiffs' motion to reopen — is based

upon legal precedents that postdate the Joint Stipulation, and

which are contrary to the prior law in this Circuit and the clear

intentions of the parties at the time the Joint Stipulation was

entered. Similarly, the Supreme Court has indicated that in such

circumstances, where a district court's interpretation of its own

orders is at odds with the parties' prior understanding, relief

11

from the orders should be granted. Pasadena City Board of

Education v. Spangler. 427 U.S. 424, 437-38 (1976).

ARGUMENT

Introduction

This appeal, while focusing upon procedural questions,

involves an extremely serious issue: whether black schoolchildren

and black citizens of Talladega County, Alabama are to be

afforded the same treatment, respect, and services as the white

citizens of that county. It is ironic, indeed, that the same

black citizens who fought a long battle to desegregate the

schools of their community now find themselves saddled with new

burdens and discriminatory treatment by the Talladega County

School System.13 Unless the judgment below is reversed, however,

they will be deprived of the protections and benefits achieved in

their school desegregation lawsuit, in spite of the care which

they took in conditioning dismissal of that case in 1985 upon the

School System's explicit commitment to abide by the prior court

orders in the case.

. Plaintiffs' Motion to Reopen, Rl-1, alleged a pattern of racially discriminatory and stigmatizing practices, including:

the closing of two historically black schools within a three-year

period, choosing to teach white children in temporary trailers

rather than send them to a historically black school less than a

five-minute drive away; choosing to build a new school and to

close two facilities to avoid assigning white children to a

historically black school; adopting a student transfer policy

which circumvents the_court orders designed to attain a unitary

school system; and ignoring the school system's promise to

implement affirmative action plans to integrate the faculty and staff of the schools.

12

I

The District Court Erred In Refusing To

Reopen The Litigation And To Enforce The

Terms Of The 1985 Settlement Agreement

Which It Had Approved As The Basis

_____ For Dismissal Of This Action______

On March 13, 1985, the district court "Approved" and

"Entered" a Joint Stipulation of Dismissal executed by the

parties (lSR-29-Exh. D, Joint Stipulation of Dismissal at 2) -

The Stipulation attached a Resolution of the Talladega County

Board of Education adopted November 22, 1983, and "incorporated

[it] herein" (Id.)- The final paragraph of the Joint

Stipulation recited that in view of the parties' agreement that

prior court orders had been effectuated in a satisfactory manner

and "in view of the attached Resolution, the parties conclude

that dismissal of this cause of action, as it applies to the

Talladega County School System, is appropriate at this time" (id.

at 2 [emphasis supplied]).

The Board of Education's resolution was quite specific. It

resolved that:

1. The Talladega County System shall be operated at all times so as to conform with the United States

Constitution, laws passed by Congress, and all previous

orders— of_this Court and the following paragraphs of

this resolution are adopted subject to this policy.

4. Every member of this Board, and all officers and employees of the Talladega County System shall

continue to adopt, maintain and implement affirmative

action programs designed to improve racial integration

among students, faculty and administrative staff of the School System.

13

(Id., Resolution at 2-3 [emphasis supplied].)

The Joint Stipulation of Dismissal, which thus embodied the

terms upon which the parties consented to dismissal of the

action, became an enforceable judgment once it was "Approved" by

the district court and "Entered."14 "A consent decree, although

founded on the agreement of the parties, is a judgment." United

States v ._City of Miami. 664 F.2d 435, 439 (5th Cir. 1981) (en

bamc)(opinion of Rubin, J .).15 "it therefore has the force of

res judicata, and may be enforced by judicial sanctions,

including a citation for contempt." Paradise v. Prescott. 767

F•2d 1514, 1525 (11th Cir. 1985), aff'd. 107 S. Ct. 1053 (1987).

Moreover, "[settlement agreements are highly favored in the law

and will be upheld whenever possible because they are a means of

amicably resolving doubts and uncertainties and preventing

lawsuits." D.H. Overmver Company v. Loflin. 440 F.2d 1213, 1215

(5th Cir.), cert, denied. 404 U.S. 851 (1971).15

The separate Judgment and Order entered on the same date recites that "The parties have submitted to this Court a

Joint Stipulation of Dismissal. In view of that submission, it

is appropriate that the above captioned case should be dismissed"

(lSR-29-Exh. D, Judgment and Order at 1) (emphasis supplied).

Significantly, the Judgment and Order did not vacate any of the

prior decrees that had ̂ been issued in the suit, including the

Joint Stipulation of Dismissal "Approved" and "Entered" by the court on the same date.

_15_ See Local--Number 93, International Assnr.iatinn 0f

Firefighters— v.— City_of Cleveland. 478 U.S. 501, 518 (1986}citing Miami. ' '

See e. g. , Pearson v. Ecological 522 F.2d 171, 176 (5th Cir. 1975) , cert,

(1976)7 W.J. Perryman & Company v. Penn

Company, 324 F.2d 791, 793 (5th Cir. 1963).

Science Cornorationr

denied. 425 U.S. 912

Mutual Fire Insurance

14

In accordance with these principles, the district court

should have carried out the terms of the Stipulation of Dismissal

by reopening the case upon plaintiffs' allegations that the

Stipulation's terms were being violated by the defendants.

Instead, the trial court — without explanation, supporting legal

precedent, or even express acknowledgement — issued a ruling

that treats the Joint Stipulation of Dismissal as if it is either

void or unenforceable. This action is indefensible.

First, the district court specifically "approved" and

entered the Joint Stipulation of Dismissal which incorporated

and was dependent upon the Board's commitment to continue to

comply with "all previous orders of th[e] Court." As we have

above, the court thereby adopted the Board's commitment

as its own decree.

Second, the district court never vacated either the Joint

Stipulation of Dismissal nor any other decree previously entered

in the action. The Judgment and Order of dismissal (1SR-29—Exh.

D) is silent on the issue of vacating or dissolving the

injunctive decrees, in stark contrast to orders of dismissal

entered by the same district judge several years later in three

other school desegregation actions on appeal to this Court

(Etowah County, Talladega City, and Sylacauga City)(R2-26; R3-25;

R4-27) . In each instance except for the Talladega County case

dismissed in 1985, the orders recite that "any and all

injunctions previously entered herein are hereby DISSOLVED

• • • *" the very least, this explicit language puts the

15

parties on notice of the consequences of the dismissal so that

they may determine whether or not an appeal is appropriate.

Third, the district court has never suggested that the Joint

Stipulation is, for some reason, void or unenforceable.

Fourth, the Board of Education agreed to be bound by the

prior court orders and to adopt affirmative action plans,

incorporating this commitment into a new decree. For these

reasons, there simply is no basis for concluding that the prior

court orders and the commitments embodied in the Joint

Stipulation of Dismissal were sub silentio extinguished or

withdrawn by the Judgment and Order of dismissal entered on the

same date as the Joint Stipulation, March 13, 1985.

It appears from the language of the district court's

opinion17 and its subsequent order18 that the court was applying

to this case the precept, set out in several of its recent

opinions, that once a school district is declared unitary and a

desegregation case is dismissed, all prior injunctive decrees

must be vacated or dissolved.19 It was error for the court to do

. 17 ."?n March 15 [sic], 1985 . . . there remained no residual injunction requiring Talladega County Board of Education to do anything" (Rl-7-2).

18 "The action as against Talladega County Board of Education was dismissed by consent in 1985. This necessarily

meant, and still means, that there are no 'outstanding court

orders' . . . applicable to Talladega County Board of Education" (Rl-11-3 [emphasis in original]).

19 The district judge in Lee v. Macon County Board ofEducation_(Nunnelley State Technical College^ . 681 F. Supp. 730

(N.D. Ala. 1988) and in the cases resulting in appeals Nos. 88-

7551, 88-7552, and 88-7553 (consolidated with this case) has

(continued...)

16

so, however, because in this case the dismissal was pursuant to a

valid consent agreement and was conditioned upon continued

adherence to the prior orders.

The district court's duty, upon the submission of

plaintiffs' Motion to Reopen, was to construe and apply the terms

of the Joint Stipulation. See Paradise v. Prescott. 767 F.2d at

1525.19 20 Thus, the district court need not have reached (nor need

this Court reach) the question of the effect — in the absence of

a court-approved dismissal agreement — of a judicial finding

that a school district has achieved unitary status.

19(...continued)

agreed with the reasoning of the Fourth and Fifth Circuits in

Riddick— v^_School Board of Norfolk. 784 F„2d 521 (4th Cir.)

cert.— denied, 107 S. Ct. 420 (1986) and United States v.

Overton, 834 F;2d 1171 (5th Cir. 1987) (dictum) that once a

finding of unitary status is made, all injunctive decrees

previously issued must be vacated. But see United States v.

Bp.ard— of_Education of Jackson Countv. 794 F,2d 1541, 1543 (lith

Cir. 1986)("That school districts have become unitary, however, does not inevitably require the courts to vacate the orders upon which the parties have relied in reaching that state").

Because the Joint Stipulation of Dismissal was "approved" and "entered" by the court, there is no question that

it is enforceable following dismissal of the action, pursuant to

its terms. .See Fairfax Countvwide Citizens Association v. County

of Fairfax, 571 F.2d 1299, 1303-04 (4th Cir.), cert, denied. 43Q U.S. 1047 (1978).

Even if the district court believed that it could not itself

have dismissed the action in 1985 without vacating prior injunctive orders, it was bound to apply the terms of the Joint

Stipulation of Dismissal since the parties to a case, through

consent, may obtain relief broader than that which a court itself

may grant. Local Number 93, International Association of

Firefighters v. City of Cleveland. 478 U.S. at 524-28. Thus,

where the parties have reached a compromise and the court has

expressly approved it, the agreement embodied in the judicial

decree governs matters covered by the decree in the future.

17

In exchange for plaintiffs' consent to dismissal of the

action, the Talladega County Board of Education agreed to

continue to comply with all prior court orders in this case and

to implement affirmative action plans. They remain bound to

those promises, and the district court committed clear error in

simply ignoring its own order approving the parties' agreement.

II

The District Court Erred In Ruling That

It Was Without Jurisdiction

To Entertain The Motion To Reopen

In its Memorandum Opinion of July 25, 1988, the district

court stated that when the case was dismissed in March of 1985,

"there was no retention of jurisdiction" (Rl-7-2) . In its July

30, 1988 Order denying plaintiffs' motion for an injunction

pending appeal, the court explained that it had held on July 25,

1988 that it was "without jurisdiction to entertain [plaintiffs'

original] motion, [and, therefore,] it [was] equally without

jurisdiction to consider [the motion for injunction pending

appeal]" (Rl-li-2). The conclusion that the district court

lacked jurisdiction even to entertain plaintiff's motion to

reopen is simply and clearly wrong as a matter of law and must be

reversed.

The law is well-established in this and other Circuits that

federal courts retain the inherent power to enforce, in either

separate ancillary proceedings or supplemental proceedings in -the

18

same case, injunctive decrees and court-approved agreements

entered into in settlement of litigation, irrespective of whether

the action was closed or dismissed after entry of the initial

relief.

Paradise v. Prescott. 767 F.2d 1514 (11th Cir. 1985), holds

that a consent decree "has the force of res judicata. and may be

enforced by judicial sanctions, including a citation for

contempt." Id. at 1525.21 Applying the same principle, the Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ruled in Lee v. Hunt. 631 F.2d

1171, 1173-74 (5th Cir. [Unit A] 1980), cert, denied. 454 U.S.

834 (1981),22 that "federal courts possess the inherent power to

enforce agreements entered into in settlement of litigation."

Id. at 1173-74.

Likewise, the Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, on

facts similar to those presented here, held in Dowell v. Board of

Education of Oklahoma Citv. 795 F.2d 1516 (10th Cir.), cert.

denied, 107 S.Ct. 420 (1986), that the district court committed

reversible error in not granting plaintiffs' motion to reopen23

to enforce injunctive decrees, even after entry of an "Order

21 Accord United States v. Citv of Miami. 664 F.2d at 440

n*8/ cited— in Local— Number 93, International Association ofFirefighters v . Citv of Cleveland. 478 U.S. at 518.

22 Decisions of the Fifth Circuit prior to creation of the

Eleventh Circuit have binding precedential weiqht. See Bonner v

City of Prichard, 661 F.2d 1206, 1209-11 (11th Cir. 1981)(enbanc). ' v—

The Tenth Circuit later characterized plaintiffs' motion to reopen in Dowell as being in the nature of a petition for a contempt citation. 795 F.2d at 1523.

19

Terminating Case." The Tenth Circuit specifically acknowledged

the "inherent equitable power of any court to enforce orders

which it has never vacated." Id. at 1520.

The Courts of Appeals for the Second, Fourth, and Sixth

Circuits have all held that the federal courts possess inherent

authority to enforce such agreements. Aro Corporation v. Allied

Witan Company, 531 F.2d 1368 (6th Cir. ) , cert, denied. 429 U.S.

862 (1976) (after dismissal of complaint and counterclaim, court

retained inherent power to enforce settlement agreement entered

in litigation)24; Fairfax Countvwide Citizens Association v.

County of Fairfax, 571 F.2d at 1302-03 ("[UJpon a repudiation of

a settlement agreement which had terminated litigation pending

before it, a district court has the authority under Rule 60(b)(6)

to vacate its prior dismissal order and restore the case to its

docket. . . . once the proceedings are reopened, the district

court is necessarily empowered to enforce the settlement

agreement against the breaching party [if] . . . the agreement

had been approved and incorporated into an order of the

court")(footnote omitted); Meetings and Expositions. Inc. v.

Tandy— Corporation, 490 F.2d 714, 717 (2d Cir. 1974) (after

dismissal district court had not only the power but the duty to

Aro— Corporation. and some other cases, rely on Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(6) in recognizing the court's authority to enforce

(by reopening a case) a settlement agreement based upon which

dismissal was obtained. ̂ (Rule 60(b)(6) provides: "On motion and

upon such^ terms as are just, the court may relieve a party .

from a final judgment, order, or proceeding for the following

reasons . . . (6) any other reason justifying relief from theoperation of the judgment.") See infra § III.

20

enforce a settlement agreement); see also Joy v. Manufacturing

Company v. National Mine Service Company. 810 F.2d 1127 (Fed.

Cir. 1987) (court has ancillary jurisdiction to enforce terms of

settlement agreement not incorporated into decree dismissing case

without prejudice); Berman v. Denver Tramway Corporation. 197

F.2d 946, 950 (10th Cir. 1952) ("A federal court is clothed with

power to secure and preserve to parties the fruits and advantages

of its judgment or decree . . . jurisdiction of the court to

entertain such a supplemental proceeding is not lost by the

intervention of time or the discharge of the res from the custody

of the court").

Thus the district court erred in denying, for lack of

jurisdiction, plaintiffs' motion to reopen.

Ill

The District Court Erred In Ruling

That Plaintiffs-Appellants Could Not Reopen The Case Pursuant To Fed. R. Civ. P. 60rbW5) or (bjl6J

-̂he district court, plaintiffs moved to reopen in order

"to enforce existing court orders" (Ri-i-i).25 In addition,

In their Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support of Motion to Reopen, (lSR-29-Exh. C at 10), plaintiffs explained:

The injunctions entered in this case have not been

vacated and remain binding on defendants. As a

condition of dismissal, defendants consented to abide

by _ the outstanding court orders. (Exhibit A).

Plaintiffs seek to reopen this case to enforce the

outstanding relief granted and consented to by defendants.

21

plaintiffs alternatively sought relief under Fed. R. Civ. P.

60(b)(5) and (b)(6) from the final judgment of dismissal, in

order to permit the court to enforce the terms of the parties'

settlement agreement. The district court refused to grant any

relief, although it is somewhat difficult to identify the grounds

for its refusal to act under Fed. R. Civ. P. 60.

In its memorandum opinion of July 25, 1988, the district

court appears to have assumed that plaintiffs had not invoked

Rule 60.26 The district court went on, however, to describe

relief from judgment through a rule 60 motion as not being

available "under the allegations made by plaintiffs" in this case

(Rl-7-2). In its subsequent order denying the request for

injunction pending appeal, the court described its July 25

opinion as holding that "it was without jurisdiction to entertain

an untimely post-judgment motion" (Rl-ll-2). The apparent

26 The district court stated that plaintiffs "invoke neither Rule 59, F.R.Civ.P., nor Rule 60, F.R.Civ.P.," as a. basis for reopening the case (Rl-7-2). This statement is incorrect.

Plaintiffs' Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support of

Motion to Reopen specifically cited the Rule (lSR-29-Exh. C at

11-12), quoted the language of sections (b)(5) and (b)(6), and

explained its ̂ applicability, with supporting precedent.

Plaintiffs explicitly advised the district court, for example that: '

An alternative ground for reopening the case exists

pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b). Rule 60(b)(5)

provides relief from a final judgment "where [quoting

language]." Thus, where there has been a fundamental

change in the legal predicates upon which a dismissal

is based, it is appropriate for the court to grant

relief under Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(5). Theriault v.

Smith, 523 F,2d 601 (1st Cir. 1975) . There has beensuch a change in this case.

Id. at 11.

22

grounds for the district court's denial of Rule 60(b) relief in

this case cannot withstand scrutiny.

We first consider the timeliness of plaintiffs' Motion to

Reopen. It appears that the district court may have mistakenly

believed that the one-year time limit applicable to motions under

Rule 60(b)(1), (b)(2), or (b)(3), governed plaintiffs' motion.

However, motions under Rule 60(b)(5) and (6) are not governed by

the one-year time limit; rather, the only limit is that the

motion be brought within a "reasonable" time:

The motion shall be made within a reasonable time, and

for reasons (1) , (2) , and (3) not more than one year

after the judgment, order, or proceeding was entered or taken.

(Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b).) The district court did not state that

plaintiff-appellants' motion was not brought within a reasonable

time, nor could it have justified such a holding on the facts

alleged by plaintiffs (where the Motion to Reopen was filed

promptly after plaintiffs learned of the School System's planned

school construction and closing plan).

The mere passage of time after entry of the original

judgment does not control the reasonableness of invoking Rule

60(b)(5) or (b)(6) at any particular point. Thus, for example,

in United— States v. Timmons. 672 F.2d 1373, 1377 (11th Cir.

1982) , the district court adjudicated, on the merits, a Rule

60(b)(4) and (b)(6) motion filed some thirty-three years after

the initial judgment, and this Court gave res iudicata effect to

23

the district court's substantive ruling.27 Plaintiffs' motion

was clearly brought within a reasonable time.

It is equally well settled that relief under Rule 60(b)(5)

or (b) (6) should have been granted by the district court "under

the allegations made by plaintiffs" (Rl-7-2). These provisions

authorize a court to grant relief from a final judgment "where a

prior judgment upon which it is based has been reversed or

otherwise vacated, or it is no longer equitable that the judgment

should have prospective application; or (6) any other reason

justifying relief from operation of the judgment."28 The Court

i-n United_States v. Georgia Power Company. 634 F.2d 929, 932-34

(5th Circuit [Unit B] 1981), vacated on other grounds. 456 U.S.

952 (1982), original opinion affirmed and reinstated. 695 F.2d

890 (5th Cir. 1983), held, after extensive discussion, that Rule

60(b)(5) provides a proper basis for granting relief from a

judgment where there has been a "significant modification in

See, £-• 9 • , Ridley_v. Phillips Petroleum Company. 427F.2d 19 (10th Cir. 1970)(motion filed fourteen years afterjudgment); Humble Oil & Refining Company v. American Oil Company

405 F.2d 803 (8th Cir. 1969)(complaint seeking Rule 60(b) relief

filed twenty-six years after issuance of injunction)? UnitedStates— v_.--Swift_&_Company. 189 F. Supp. 885, 906 (N.D. 111.

1960)(thirty-six years after entry of consent decree). aff'd npr curiam. 367 U.S. 909 (1961). ------H--

. -̂s clear that plaintiffs could proceed by way of amotion to reopen, rather than through an independent action. Rule 60 "provides two types of procedure to obtain relief from

judgments. The usual procedure is by motion in the court and in

the action in which the judgment was rendered. . . . The other

procedure is by a new and independent action to obtain relief

from a judgment, which action may, but need not, be begun in the

court that rendered the judgment." 11 c. Wright and A. Miller Federal Practice and Procedure § 2851, at 141-42 (1973).

24

decisional law" upon which a judgment was based. Accord

Theriault v. Smith. 523 F.2d 601 (1st Cir. 1975). As we describe

below, these conditions were met in the present case.

The language of the 1985 Joint Stipulation of Dismissal

indicates that all parties understood that the prior court

orders, and the new promise of the school district to comply with

them and to adopt affirmative action plans, would survive the

dismissal of the action. Moreover, that expectation was

consistent with substantial precedent in this Circuit. For

example, in nearly every individual school district's Lee v.

^acon— County case in the Northern District of Alabama except

Talladega County, the school system was declared "unitary" in the

mid-1970's and, simultaneously, the district court substituted a

general permanent injunction for the previous detailed regulatory

decrees and placed the case on the inactive docket -- rather than

vacating all injunctive orders and dismissing the action.29

Similarly, in the Georgia state—wide school desegregation case

declarations of unitariness were made pursuant to consent and the

court simultaneously entered general permanent injunctions.30

Dismissal was therefore not the common, much less inevitable,

O Q See e.g., lSR-29-Exhs. F, G, and H.

30 See United States v. Georgia. 691 F. Supp. 1440 (M.D.Ga. 198 8) ; Georgia State Conference of Branches of NAACP v.

Georgia, 775 F.2d 1403, 1413 n.ll (11th Cir. 1985). See also!

Monteilh_v. St. Landry Parish School Board. 848 F.2d 625*

629, text at nn. 8, 9 (5th Cir. 1988); United States v. Board of

Education of Jackson County. 794 F.2d 1541 (11th Cir. 1986);

United_States v. Lawrence County School District. 799 F 2d 10311037-38 (5th Cir. 1986). '

25

nor were such findingsresult of a finding of "unitariness,"

regarded as the signal to dissolve all court orders.

When the Motion to Reopen was submitted, however, the

district court attached different collateral legal consequences

to the 1985 dismissal order by virtue of its recitation that the

school system had achieved "unitary status." See supra note 19

and accompanying text. Specifically, the district court held

that the order "made it perfectly clear, if it were not already

clear, that this case was in all respects concluded as to

Talladega County Board of Education" (Rl-7-1), and that even

though the 1985 order did not explicitly vacate prior injunctive

decrees "there was no retention of jurisdiction by this court and

there remained no residual injunction requiring Talladega County

Board of Education to do or not to do anything" (Ri-7-2).31

The district court appears to have focused upon the recitations in the March 13, 1985 Joint Stipulation of Dismissal,

and the Judgment and Order entered on the same date, concerning

the operation of a "unitary school system" or "unitary status"__

and to have applied_ rulings from other Circuits announced

subsequent to the dismissal of this case that require termination

of ^11 jurisdiction and dissolution of all court orders when a

of "unitary status" is made. See Lee v, Macon County Board— of— Education (Nunnelley State Technical College^ . 681 F.

Supp. 730, 736-38 (N.D. Ala 1988) (discussing cases) and the

opinions entered by the district court in the three cases

consolidated on appeal with this one (R2-25; R3-24; and R4-26).

As we have earlier suggested (supra at 17), it is

unnecessary for the Court to consider these issues in the

Talladega_County matter. Plaintiffs are entitled to reversal of

the judgment below either because of the explicit terms of the

Joint Stipulation of Dismissal (§ I of this Brief) , because the

court should have enforced the Stipulation as a settlement

agreement (§ II of this Brief), or because they were entitled to

relief from the dismissal, and any collateral consequences

thereof, under Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(5) and (b)(6) (seediscussion in this section).

26

Even if we were to assume that the district court correctly

interpreted and stated the present law, its holding represents

the very sort of change which Rule 60(b)(5) is intended to reach.

See United States v. Georgia Power Company. It indeed would be

"no longer equitable" to enforce the final order of dismissal if

the terms upon which plaintiffs consented to that dismissal in

1985 no longer apply in 1988. Otherwise, by virtue of the

district court's recently adopted position, without any notice

plaintiffs will have lost everything they bargained for in 1985.

In similar circumstances involving an ultimate

interpretation of a decree by the district court that was at odds

with the interpretation of the parties and inconsistent with an

intervening substantive ruling, the Supreme Court in Pasadena

City Board of Education v. Spangler. 427 U.S. 424, 437-38 (1976)

(Rehnquist, J.), reversed the district court's refusal to modify

its earlier injunction, relying on the "well-established rules

governing modification of even a final decree entered by a court

of equity" and "the fact that the parties to the decree

interpreted it in a manner contrary to the interpretation

ultimately placed upon it by the District Court."

Accordingly, the district court's current interpretation of

the effect of the dismissal, which is based upon legal decisions

that postdate the Joint Stipulation and which is clearly at odds

with the plain language of the Joint Stipulation, provides the

basis upon which relief from the judgment of dismissal should

hsve been granted. It was an abuse of discretion for the

27

district court not to grant relief under Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(5)

and (6).

For the reasons stated above, plaintiffs-appellants

respectfully pray that the July 25, 1988 orders of the district

court denying their Motion to Reopen this case to enforce the

terms of the Joint Stipulation of Dismissal and the attendant

requests to add parties and take discovery be reversed.

Conclusion

Anniston, AL 36202

(205) 236-1240

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

NORMAN J . CHACHKIN

JANELL M. BYRD

99 Hudson Street, 16th FI.

New York, New York 10013 (212) 219-1900

December lb , 1988 Counsel for Plaintiffs- Appellants

28

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that on this day of December, 1988

served two copies of the Brief for Appellants upon counsel

the other parties to this appeal, by depositing the same in

United States mail, first-class postage prepaid, addressed follows:

George C. Douglas, Jr., Esq. Ralph Gaines, Jr., Esq.

Gaines, Gaines & Gaines, P.C. Attorneys at Law

127 North Street

Talladega, Alabama 35106

Thomas E. Chandler, Esq. Dennis J. Dimsey, Esq.

Appellate Section

Civil Rights Division

U.S. Dept, of Justice P. O. Box 66078

Washington, D.C. 20035-6078

Frank Donaldson, Esq.

Caryl Privett, Esq.

Office of the U.S. Attorney

1800 Fifth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Solomon S. Seay Jr., Esq.

P. 0. Box 6215

Montgomery, Alabama 36106

Donald B. Sweeney, Jr., Esq.

Rives & Peterson

1700 Financial Center

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

James R. Turnbach, Esq.

Pruitt, Turnbach & Warren P.O. Box 29

Gadsden, Alabama 35902

, I for

the

as

29