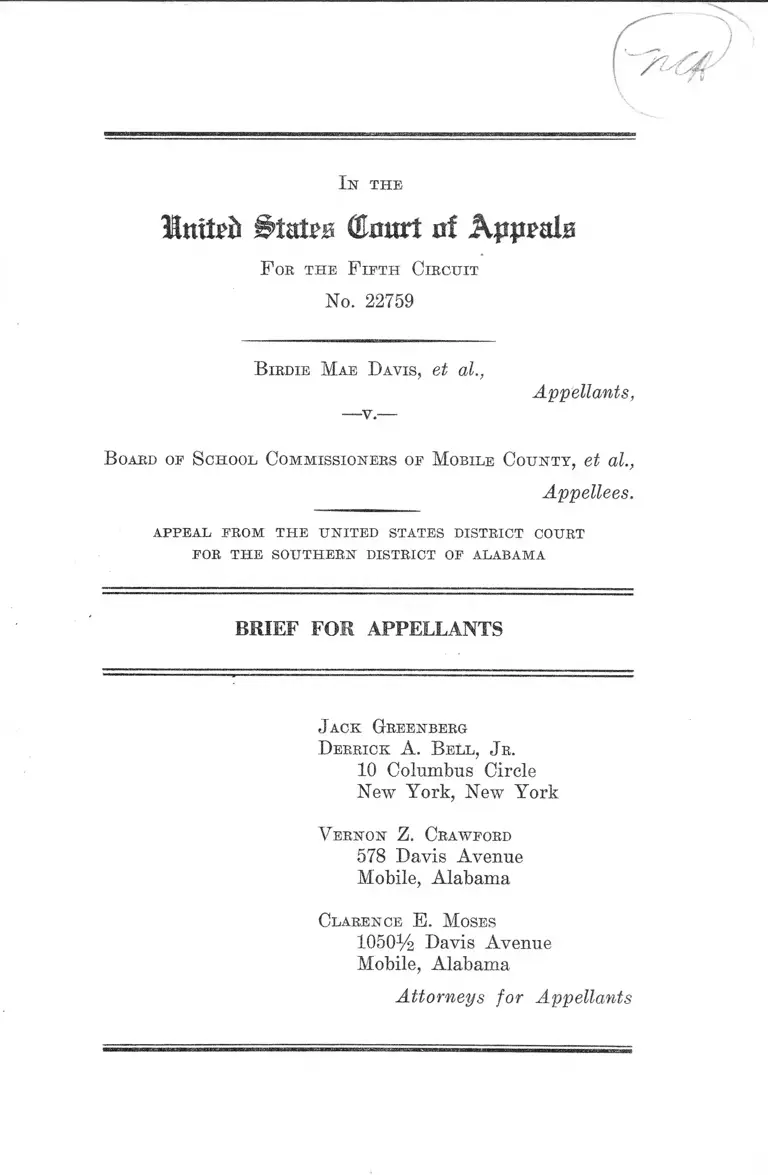

Davis v. Mobile County Board of School Commissioners Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

September 27, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Davis v. Mobile County Board of School Commissioners Brief for Appellants, 1965. a22f070a-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4d2dcd25-a0ad-4b3d-91ca-6e3745443ef2/davis-v-mobile-county-board-of-school-commissioners-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

In the

Htut£& # tate (Enurt 0! Appeals

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 22759

B irdie Mae Davis, et al.,

— v .—

Appellants,

Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County, et al

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Jack Greenberg

Derrick A. Bell, Jr.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

V ernon Z. Crawford

578 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama

Clarence E. M oses

1050% Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama

Attorneys for Appellants

INDEX TO BRIEF

PAGE

Statement of the Case ........... ........................................ 1

Summary of Previous Litigation ----------------- ----- 2

The Board’s Desegregation Plans ....... .... ............ 3

1963- 64 Plan .................-........ ........ -............... 3

1964- 65 Plan ................. -.........-...... - -...... —- 3

1965- 66 Plan ........ -......... .............. - .............. 6

Analysis of the Board’s Plan ........ ......... ................ 6

Zone Lines ........ ................. -......... .................... 6

Rural Bus Routes ............................................ 9

Initial Assignment Option ............................... 9

The Feeder System ................. ................. - 10

The Transfer Procedure ..................... -........... U

Hardships Under the Plan .............................. U

Desegregated Experiences ...................... - ....... 12

Teacher Desegregation ........................ -......... - 13

Inequality in Negro Schools --------- --------------- - 14

The District Court’s Opinion ------- --------------- ---- 14

Specifications of Error ------------ ---- ------------ ---- --------- 15

A bgument—

To Insure the Relief to Which Appellants Are

Entitled Under Brown Will Require a Plan De

signed to Integrate the Mobile School System .... 16

Relief ............................. -....... -......................................... 28

Conclusion ......... ........... ......... -................................................ - 31

Table of Cases:

page

Acree v. County Board of Education of Richmond

County, Georgia, ------ F. 2 d ------ (5th Cir., No.

22723, June 30, 1965) ........-........ -------- ------- ---- -----

Armstrong v. Board of Education of City of Birming

ham, 323 F. 2d 333 (5th Cir. 1963) ........ - ........ -2.

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction, 306 F. 2d 862

(5th Cir. 1962) ...... ..... ....................... -....... - ...............

Bell v. School City of Gary, Ind., 324 F. 2d 209 (7th

Cir. 1963), cert. den. 377 U. S. 924 ...........................— 17

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County v.

Braxton, 326 F. 2d 616, 620 (5th Cir. 1964) cert.

den. 377 IT. S. 924 ___ ___~~~...... -...... -......... -......... - 22

Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County v.

Davis, stay denied 11 L. ed. 2d 26, cert, den., 375

IT. S. 894, pet. for reh. den., 376 U. S. 928 ------- ---- 3,16

Bosun v. Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43, 46 (5th Cir. 1960) ----- 20

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776, 777 (E. D. S. C.

1955) ................ -...... ...... ......... ....... ..... -..... -................. 2®

Brooks v. County School Board of Arlington, Vir

ginia, 324 F. 2d 303, 308 (4th Cir. 1963) ......... -....... 17

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) —.2, 28

Calhoun v. Latimer, 321 F. 2d 302 (5th Cir. 1963) - - 20

Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsborough, 228

F. 2d 853 (6th Cir. 1956) ........................... - ....... - ... 17

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 IT. S. 1 ................. ........ ......—- 2^

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 318 F. 2d 63, 64 (5th Cir. 1963) --------------- 2

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 322 F. 2d 356 (5th Cir. 1963) -............... --- 2

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 333 F. 2d 53, 55 (5th Cir. 1964) ...........2, 3, 5,17

PAGE

in

Dowell v. Board of Education of the Oklahoma City

Public Schools,------F. Supp.------- (No. 9452, W. D.

Okla., Sept. 7, 1965) .........................-..... -..........- - ..... 29

Downs v. Board of Education of Kansas City, 336

F. 2d 988 (10th Cir. 1964), cert, den., ----- - U. S.

------ (1965) ................ ..............-..........-----................... - 17

Gaines v. Dougherty County Board of Education, 329

F. 2d 823 (5th Cir. 1964) ........................... - ............... 22

Gaines v. Dougherty County Board of Education, 334

F. 2d 983 (5th Cir. 1964) ................................... -~19, 28

Goss v. Board of Education of City of Knoxville, 373

U. S. 683 (1963) ................. -................................ ........ 20

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction, 258 F. 2d 730

(5th Cir. 1958) ........... -.............. -..................... ........... 17

Lockett v. Muscogee County Board of Education, 342

F. 2d 225, 229 (5th Cir. 1965) ........-................ -20, 22, 28

Northcross v. Board of Education of City of Memphis,

333 F. 2d 661 (6th Cir. 1964) ....................... .............. 17

Price v. Denison Independent School District, ------

F. 2 d ------ (5th Cir., No. 21632, July 2, 1965) .......21, 22,

23, 29

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, ------F. 2 d ------- (5th Cir. No. 22527, June 22,

1965) ....................................... -.................................... - 26

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Educa

tion of Birmingham, 333 F. 2d 55, 65 (5th Cir.

1964) .............................. ....... ..........-.... - .... -......2, 5, 20, 21

Taylor v. Board of Education of New Rochelle, 191

F. Supp. 181, 192 (S. D. N. Y., 1961), aff’d 294 F. 2d

36 (2nd Cir. 1961), cert. den. 368 U. S. 940 .............. 17

Isr the

Ittifri* U tate ©our! nf Appeals

F ob the F ifth Circuit

No. 22759

B irdie Mae Davis, et al.,

-v .~

Appellants,

B oard op School Commissioners of Mobile County, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement o f the Case

This is an appeal from the March 31, 1965 decree of

Southern District of Alabama District Judge Daniel H.

Thomas, the effect of which enables the appellee Board of

School Commissioners of Mobile County to maintain almost

complete segregation of the 79,000 pupils attending the

94 schools in its system (R. 29). Despite directions and

mandates issued by this Court and the United States

Supreme Court on twelve different occasions during the

course of the three previous appeals which appellants

have been required to file since this suit was filed in March

1963, only 36 Negro pupils were enrolled in white schools

for the 1965-66 school year. The earlier litigation provides

a necessary background to this appeal.

2

Summ ary o f Previous Litigation

Despite petitions from Negroes in 1955, 1962 (R. 103),

and efforts by some appellants to obtain desegregated

transfers in January 1963 (R. 90, 104) the appellee Board

refused to recognize any duty to comply with the Supreme

Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S.

483. The first appeal followed the district court’s refusal

to either promptly grant or deny appellants’ motion for a

preliminary injunction. This Court dismissed the appeal

but noted in doing so that the schools are segregated,

that the amount of time available for the transition to

desegregated schools is sharply limited, and that prompt

action would be necessary. Davis v. Board of School Com

missioners of Mobile County, 318 F. 2d 63, 64 (5 Cir. 1963).

But despite this admonition, the district judge denied

injunctive relief for the 1963-64 school year, citing both

the impossible administrative burden such action would

impose on the Board and his belief that the problem would

work itself out without strife if action was not too hastily

taken. Trial was set for November 14, 1963.1 Again ap

pellants returned to this Court, which on July 9, 1963,

granted their request for an injunction pending appeal,

requiring desegregation to begin in at least one grade

for the 1963-64 school year. Davis v. Board of School

Commissioners of Mobile County, 322 F.2d 356 (5th Cir.

1963), modifying its order on petition for rehearing to

conform with a similar mandate entered a few days earlier

1 The trial took two days during most of which appellees compiled a

record intended to justify segregated schools because of asserted in

tellectual inferiority o f Negro pupils. The district court never entered

a decision in the case, but the issues were settled by this Court in Stell

v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Education, 333 F. 2d 55 (5th

Cir. 1964), and Armstrong v. Board of Education o f City of Birmingham,

333 F. 2d 47 (5th Cir. 1964).

3

in Armstrong v. Board of Education of City of Birming

ham, 323 F.2d 333 (5th Cir. 1963),2

The third appeal was filed following the district court’s

approval with a few modifications of a desegregation plan

which, appellants maintained, failed to meet this Court’s

standards as contained in its July 1963 amended mandate.

On June 18, 1964, this Court ruled in appellants’ favor on

the second appeal by vacating the district court’s order

denying injunctive relief and the third appeal by order

ing the Board to present forthwith a desegregation plan

meeting certain definite minimum standards as contained

in its opinion. Davis v. Board of School Commissioners

of Mobile County, 333 F.2d 53 (5th Cir. 1964).3

The Board’s D esegregation Plans

1963-64 Plan— Filed August 17, 1963, the Board’s origi

nal plan limited transfers to high school students in the

City about to enter their twelfth and final year (R. 4).

Transfer requests were to be made in writing by July 31,

1963 (a date already past when the plan was published)

on forms prescribed and supplied by the Board to parents

of pupils on request (R. 5, 8-9). All transfer applications

were judged by pupil placement act criteria including

2 Appellee Board, after unsuccessfully seeking a stay from Judge

Wisdom of this Court, applied for a stay of the mandate from Supreme

Court Justice Hugo L. Black pending consideration of a petition for

writ o f certiorari. The application for a stay was denied by Justice

Black, Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County v. Davis, 11

L. ed. 2d 26, and certiorari was denied on October 28, 1963, 375 U. S.

894. A motion for leave to file a petition for rehearing was denied on

February 17, 1964, 376 U. S. 928.

3 Appellees’ petition for rehearing was denied by this Court on July

21, 1964, as was an application for a stay of the mandate, pending ap

plication to the Supreme Court for a writ of certiorari on August 20,

1964. A stay was then sought from Justice Black and vrns denied on

September 3, 1964. The petition for writ of certiorari was denied

October 12, 1964. 13 L. ed. 2d 49.

4

availability of room in the school, transportation, suit

ability of curricula, pupil’s interests, reason assigned for

request by parents, effect of transfer on established or

proposed programs, adequacy of pupil’s academic prep

aration, pupil’s scholastic aptitude and relative intelli

gence, psychological qualifications of pupil, effect of trans

fer upon academic progress of other students, and on

prevailing academic standards, possibility of threat of

friction or disorder among pupils, psychological effect of

transfer upon other students, possible community breaches

of peace or ill will, pupil’s home environment, maintenance

or severance of established social and psychological rela

tionships with other pupils and teachers, and the pupil’s

morals, conduct, health and personal standards. In addi

tion, the Board could consider “other relevant factors” ,

and the transfer applicant was subjected to tests or exam

inations by the Board, which could also require interviews

with the parents or the pupil (R. 6-7).

Denial of transfer requests was to be final unless review

was requested in writing within 10 days of the date when

notice of the denial was received by mail. In 1963, deci

sions on transfer applications was to be taken on Sep

tember 3rd, one day before schools opened. Hearings,

within 20 days before the Board, required presence of

parents and pupil, with decisions within another 15 days.

In addition to overruling or affirming the denial, the plan

permitted the Board to find the pupil “physically or

mentally incapacitated” to benefit from further normal

schooling and could assign the pupil to a special school

or terminate his enrollment completely (R. 7-8).

Initial assignments for first graders (when the plan

reached the first grade) and for pupils entering the sys

tem for the first time (in grades to which the plan had

become applicable) could “apply for attendance at the

5

school in the district of their residence, or the nearest

school formerly attended exclusively by their race, at

their option” (R. 8).

Despite appellants’ objections, the district court on

August 23, 1963 approved the Board’s plan, modifying it

only to permit transfer applicants from August 23rd to

request transfers, and requiring that processing of appli

cations be completed prior to the opening of school. The

Board approved 2 of 29 Negro applicants for the 1963-1964

school year (R. 104).

1964-65 Plan—Despite the minimum standards for de

segregation plans contained in this Court’s June 18, 1964

opinions in Davis, Armstrong and St ell, the Board sub

mitted and the district court approved for the 1964-65

school year a plan only slightly altered from that in effect

the year before. This Court’s mandate required desegrega

tion in grades 1, 10, 11, and 12 for the 1964-65 school

year, but the Board announced that pupils scheduled to

enter the first grade had been pre-registered near the end

of the previous term and that tentative enrollments had

been developed for both the 1st grade and, following the

April 1-15 transfer request period, for the 11th and 12th

grades (E. 10). Evidently for this reason, the Board’s

plan failed to provide for the reassignment on a desegre

gated basis of pupils scheduled to enter the 1st grade who

had already been pre-registered in schools on the basis of

race, and no further transfer period was provided for

students entering the 11th and 12th grades. A three-day

period (August 4-6) was provided for transfer requests

from 1st and 10th grade pupils in the city schools only.

The Board limited desegregation in the county schools

to grades 11 and 12 even though no authorization for such

limitation was contained in this Court’s June 18, 1964 opin

ion and a petition for rehearing filed by the Board and

6

containing on pp. 4-5 a specific request for such limitation

was denied by this Court on July 21, 1964.

In approving this plan, the district court extended the

transfer period from three to six days and permitted

county pupils in the 10th, but not the 1st, grade to request

transfers (R. 15). Publication of the plan’s provisions

was required for three consecutive days instead of just

one as proposed by the Board (R. 15-16). Only 16 Negro

pupils sought transfer to desegregated schools for the

1964-65 school year. The Board granted seven requests

and denied nine (R. 21).

1965-66 Plan—Appellants in December 1964, filed a mo

tion for further relief seeking a desegregation plan for

the 1965-66 school year that -would effectively desegregate

the school system (R. 17-20). The Board responded deny

ing both that their plan which would encompass grades

1, 2, 9, 10, 11 and 12 for the 1965-66 school year failed to

meet judicial standards, and that the Supreme Court had

affirmed “ . . . any ‘right’ to a desegregated education to

the exclusion of all other proper factors” (R. 22). The

Board maintained that its plan was being fairly adminis

tered and sought to be “freed from the constant harass

ment of annual motions to completely revamp and radically

alter the administration of a large and complicated sys

tem” (R. 23). Nevertheless, the court below with minor

modifications discussed below approved the Board’s plan

(R. 45).

Analysis o f the Board’s Plan

Zone Lines—In recent years, Mobile’s neighborhood pat

terns have become quite strongly segregated (R. I ll , 113).

Since elementary school zones have been drawn to main

tain a homogeneous community, and elementary school

pupils are initially assigned to schools serving their resi

7

dential areas, the result is that most Negroes reside in

zones served by Negro schools (R. 83-84, 145). On this

point, Superintendent Burns testified:

“Q. I will ask you whether it is generally true that

the actual make up of the school district tends to

conform with the race of the school within that dis

trict? A. Yes, sir.” (R. 65).

The school zones presently in use are, with some excep

tions, similar to those utilized before this suit was filed.

At that time, Negro pupils residing within zones served

by white schools attended Negro schools located outside

the zones of their residences. For example, the Super

intendent testified that Negroes residing in the Saraland

elementary school zone attended the Negro Cleveland ele

mentary school (R. 59-60). This procedure is still fol

lowed as to elementary grades three to six not yet in

cluded within the plan.

Appellees admitted their desire to maintain racially

homogeneous neighborhoods seeking to justify this by

explaining the role played by the school as a center of

community activities. Since community functions are gen

erally segregated, the Board deems it important to con

sider community desires in locating or operating a school

so as to maintain a “ satisfactory relationship with the

community” (R. 76-77).

But the Board maintained such considerations were only

one factor utilized in drawing elementary school zone lines

(R. 83) and maintain that other criteria such as safety

hazards, natural boundaries and efficient school utilization

were also considered (R. 75, 83). The elementary zone map

(R. 253) illustrates however, that maintenance of homo

geneous racial communities was a prime consideration when

8

the zone lines were drawn, and appears to enjoy a continu

ing priority notwithstanding the fact that several addi

tional elementary schools have been constructed since the

map was prepared (R. 140-44). For example, the Negro

Warren school zone (located near the center of the max)

R. 253, at the convergence of sections G and 7) was, until

this year, divided into two sections by the white Crichton

school zone (E. 64-65). Testimony indicates that the War

ren and Crichton school zones have been redrawn with the

result that some Negroes are now residing within the

Crichton zone (E. 250), but the white Craighead school zone

(located at sections K and 14 on the map) continues to be

split by the Negro Williamson school zone (R. 253), and

the small Negro Cottage Hill school zone (located at sec

tions B and 16 on the map) is entirely enclosed within the

large Shepherd elementary school zone which serves white

pupils (R. 118, 178). The Superintendent testified that the

Cottage Hill facility although underutilized with an en

rollment of only 119 pupils and 4 teachers (R, 179) was

retained at the request of N egroes living in the community

(R. 178,184-85).

Appellants’ efforts to obtain detailed information as to

how many Negro and white pupils resided within each

elementary school zone were frustrated. First, by the

Board attorney’s interpretation of interrogatories designed

to produce this information (R. 147, 231) and later by the

asserted lack of knowledge of Board witnesses on such

figures (R. 145, 151, 155-56, 230-31). While the Superin

tendent contended that there were many zones within which

both Negroes and whites resided (R. 145, 150-51) he con

ceded that the zone lines follow racial neighborhoods “to

a considerable degree” (R. 145), acknowledging again that

a majority of pupils reside in zones which are either all

white or all Negro (R. 151).

9

Rural Bus Routes. No school zone lines are drawn by the

Board for the rural sections of Mobile County (B. 139, 153).

Instead, bus routes serve neighborhood areas, and since

neighborhoods, as in the urban areas of the county, tend

to be structured along separate racial lines, racial patterns

similar to those identifiable in the urban school zone lines

are found in the rural bus routes (B. 70, 154).

Initial Assignment Option—If there is room for debate

as to what percentage of the Board’s elementary school

zones contain either all Negroes or all whites, there is no

doubt that all white pupils within the desegrated elemen

tary grades continue to attend white schools regardless of

their residence and that virtually all Negro elementary

pupils attend Negro schools even though a few of them

may reside in zones serving white schools. The key to the

continuing segregated patterns at the elementary level is

found in the provision of the Board’s plan providing an

option to pupils entering the system at the first grade or

for the first time in grades being desegregated (B. 8, 273).

This option enables pupils to choose either the school lo

cated within the zone where they reside or the nearest

school previously serving members of their race. Thus, a

Negro first grade pupil residing within the Negro Cottage

Hill zone may choose to enter either Cottage Hill or the

nearest Negro school (B. 148). A Negro child residing

within the white Austin school zone (B. 64) may choose

either Austin or the nearest Negro school (B. 149).

To the extent that Board witnesses who maintain there

were zones in which both Negroes and Whites reside are

correct, the option provision permits all pupils who other

wise would be assigned to a school serving mainly the

opposite race to transfer back to a school where their race

is in the majority. Apparently, virtually all pupils able to

10

make an effective choice for segregation under this option

provision have done so (R. 311-12).

The Feeder System. High school assignments are con

trolled basically by a system of feeder schools, by which

several elementary schools in an area send their graduat

ing students to a particular junior high school, and one or

more junior high schools feed their graduates to a senior

high school (R. 254-63). The feeder system, originally con

structed on a segregated basis, has never been reorganized,

nor does the Board have any definite plans to do so (R. 138-

39, 236-37). As a result, not only are all pupils assigned

from elementary to junior high and from junior to senior

high school on a segregated basis, but high school pupils,

including some of the appellants, seeking to obtain a deseg

regated education, have found it next to impossible to

determine the white school to which they should apply for

transfer. Thus, prior to the 1964-65 school year four of the

nine students whose transfer applications were denied were

informed by the Board that they did not reside in one of

the attendance areas served by the school to which they

sought transfer (R. 271-72). Indeed, the Assistant Super

intendent indicated that had appellant Birdie Mae Davis,

whose request for a transfer to the Murphy School was

granted, chosen another school, say Davidson, her transfer

request would have been denied (R. 241-42).

Appellants and others seeking transfer have never been

informed as to which school they should apply for admis

sion (R. 177), a shortcoming understandable in the light

of testimony by both the Superintendent and his assistant,

neither of whom was able to state how the determination

was made as to which white school a Negro student should

apply (R. 173-77). Apparently, judgments are made on a

case-to-case basis although such information was not made

11

available to transfer applicants whose applications to the

“wrong” school had been denied.

The Transfer Procedure. Board transfer procedures are

strict and are strictly adhered to. For the 1963-64 school

year, 25 to 30 pupils sought desegregated educations at

varying periods during the year (R. 210), but the Board

considered only the four applications received during the

five day period permitted for transfer requests in the

district court’s order (R. 270). For the 1964-65 school

year, the Board plan required all transfer applications

to be filed between April 1-15 for grades 11 and 12 (R. 4).

After this Court’s opinion of June 18, 1964, requiring

desegregation of grades 1 and 10, the Board provided

three days (R. 12) (extended to six days by the district

court) to receive transfer applications, but limited those

to pupils in either grades 1 and 10. The three pupils

seeking transfer during this period in grades 11 and 12

were turned down (R. 271-72).

Transfer application forms were almost as difficult to

obtain as the transfers themselves. For the 1964-65 school

year, a parent had to appear in person at the school board

office, obtain a transfer application form (R. 319), take

it home, complete it and obtain the signatures of both

parents, and then return the form to the Board (R. 5).

This requirement (eliminated for the 65-66 applications

by the district court order (R. 45-46) permitting the forms

to be returned to the school board offices by mail or other

convenient method) caused great inconvenience to parents

seeking to comply, including in one case travel of approxi

mately 60 miles (R. 109-10). The Board sought to meet

this complaint by extracting from the witness the fact

that the distance traveled was over good roads (R. 115).

Hardships Under the Plan. John LeFlore, a Negro ac

tive in civil rights in the Mobile area for over 35 years

12

(R. 102), testified that fear of loss of job, violence and

other reprisals from a community that clearly did not

favor such desegregation, was a more important factor

than inconvenience in understanding why so few Negro

parents had applied for transfers (R. 105-06). Both he

and Algea Bolton, the father of one of the minor appel

lants, reported that they had gone door to door in Negro

communities explaining to parents their rights under the

desegregation order (R. 94, 97, 107-09), but that prior to

the 1964-65 school year, fewer Negro children were willing

to transfer because of instances of violence which caused

many to advise that they were afraid to attend mixed

schools (R. 107). Mr. LeFlore testified:

“We found that there was a growing interest on the

part of the Negroes for desegregation, although it

was not manifested in the number we were able to

get to attend schools other than Negro schools, be

cause, as we pointed out, apparently there was a fear

that developed on the part of one parent or another

or upon the part of the student, which served as a

handicap to the desegregation effort” (R. 109).

Efforts to interest Negro parents in applying for trans

fers to white schools, according to Mr. LeFlore, were

further handicapped by the apparent inconsistency of

Board policy. Thus Negroes whose children had been

bussed miles past available white schools in order to reach

Negro schools were denied transfers to those schools when

new schools for Negroes were built closer to their homes

(R. 117-18).

Desegregated Experiences

Two Negro girls who had obtained transfers in the 12th

grade to a formerly all-white school testified that the

13

work was harder and called for more study (R. 123-124,

133), that there was much more equipment, and that the

equipment was more quickly obtained upon order (R. 125-

132). In comparing their progress with their former class

mates from the predominantly Negro schools, they con

sidered themselves “much more advanced in all subjects”

(R. 113, 124). They were harassed considerably by white

students and some teachers (R. 122, 126, 128-32), and

unable to use public transportation because of the danger

(R. 106, 113). One of the students, appellant Birdie Mae

Davis, testified that they were treated better by those

students with whom they attended classes, but met con

stant expressions of hostility from those with whom they

had no classroom contact (R. 130).

She expressed the view that such treatment results from

fear on the part of the white students that the bjegioes

will do better than they (R. 129-30), adding that condi

tions would improve if there were more Negroes attend

ing the white school (R. 133). She has made efforts to

communicate the advantages of a desegregated education

to other Negro students, indicating that this is necessary:

“ . . . because most of the children I talk to have the

idea that they are afraid to go, because of the things

that they [the white students] do, but I try to tel]

them that it is not as hard as it really seems, because

once you get used to it you can take it” (R. lo3-34).

Teacher Desegregation

Teacher and personnel desegregation has not been at

tempted, according to the Board Superintendent because of

difficulties flowing from the delicate relationship between

parents, teachers, and students (R. 201). There are no

differences in the educational qualifications of white and

14

Negro teachers (R. 78), but there is a separate Negro

official in charge of coordinating instruction for Negro

schools (R. 86). The Superintendent commented that dif

ferences in socio-economic backgrounds between Negroes

and whites are reflected in the habits and abilities of the

students and this may account for any difference in teach

ing levels in Negro and white schools (R. 204-205).

Inequality in Negro Schools

Of the 75 nonstandard courses, such as shorthand, Latin,

industrial arts, and journalism, offered by Mobile public

schools, 45 are not offered at any Negro school. Eight other

courses generally available at white schools are offered at

only a few Negro schools (R. 322), and while 17 schools

have classes for “exceptional” (handicapped or retarded)

children, 14 of the total are white schools (R. 169). Super

intendent Burns testified that certain courses were offered

only at predominantly white schools because of the prefer

ence of the students (R, 203). He also assigned the differ

ences between predominantly Negro and predominantly

white schools to the disparity in conditions and opportu

nities which had been prevalent in the past. He considered

most important the difference in the backgrounds of the

students and their parents (R. 206). He admitted that most

Negro schools were smaller than white schools, that only

larger schools could feasibly offer the special courses, and

that as a rule school systems tend to move toward larger

units (R. 179).

The District Court’s Opinion

With the exception of altering the requirement that

parents must both request the form at the Board offices and

return the completed form in person so that the completed

form could be returned by mail or other convenient method,

15

striking as improper transfer criteria concerning the psy

chological qualifications and effects of the pupil and his

classmates, the possibility or threat of friction or disorder

in the school or community, and requiring additional notice

to parents as to their rights under the plan (R. 45-47).

The lower court approved the plan as “constitutional” and

deemed its administration “non-diseriminatory” (R. 46).

Specifications of Error

1. The lower court erred in failing either to require the

Mobile County School Commissioners to make initial as

signments in accordance with zone lines and other criteria

not based on race, or to allow all pupils, regardless of race,

the choice of enrolling in the nearest desegregated school

until capacity is reached.

2. The lower court erred in failing to require the Board

to conform its plan to the standards concerning transfer,

notice and other particulars established by this Court in

its decision of June 18, 1964, and in subsequent applicable

opinions.

3. The lower court erred in failing to require the Board

to present a plan which, based on a consideration of all

legally relevant factors, was fairly capable of disestablish

ing the segregated school system maintained by the Board

and providing within the time permitted in current inter

pretations of the Supreme Court’s “all deliberate speed”

standard, the integrated school system to which appellants

and their class are constitutionally entitled.

16

A R G U M E N T

To Insure the Relief to Which Appellants Are En

titled Under Brown Will Require a Plan Designed to

Integrate the Mobile School System.

Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black reviewing a motion

for stay filed by the Board in August 1963, wrote that the

record “ . . . fails to show the Mobile board has made a

single move of any kind looking towards a constitutional

public school system.” Board of School Commissioners of

Mobile County v. Davis, 11 L. ed. 2d 26, 28 (1963). Appel

lants submit that despite the subsequent orders issued by

the district court and this Court, and notwithstanding the

token desegregation that has resulted under the Board’s

reluctantly produced plan with its amendments, additions,

deletions and supplements, the conclusion of Justice Black

is as accurate today as it was more than two years ago.

A review of the Board plan which the court below ap

proved as “constitutional” and “non-discriminatory” reveals

at least a dozen clear violations of the minimum standards

for desegregation plans required by this Court:

1. The assignment of pupils in accordance with elemen

tary school zone lines drawn so as to conform to racial

neighborhoods (R. 65) effectively maintain race as the basis

of initial assignment. While Mobile has few integrated

communities (R. I l l ) , the Board has relied on the most

flagrant kinds of gerrymandering which include enclosing

a school zone in a Negro neighborhood entirely within the

boundaries of a white school zone (R. 178) and dividing a

school zone into two sections in order to contain all of one

racial population within one school (R. 64-65). As a result

of such zoning policies, Board officials concede that a great

majority of school zones contain either all Negro pupils or

all white pupils (R. 151), and while maintaining that there

were zones which contain both Negroes and whites (R. 145,

17

150-51), were able to cite only a few such instances even

in the face of both testimony showing Negroes are consis

tently assigned to Negro schools located further from their

homes than white schools (R. 117-18), and tables of ele

mentary school enrollments for the 1964-65 school year

showing only Negroes in Negro schools and only white

pupils in white schools (R. 311-12).

School zone lines drawn to conform to racial neighbor

hoods were early condemned by this Court in Holland v.

Board of Public Instruction, 258 F. 2d 730 (5th Cir. 1958).

See also, Brooks v. County School Board of Arlington,

Virginia, 324 F. 2d 303, 308 (4th Cir. 1963); Northeross v.

Board of Education of City of Memphis, 333 F. 2d 661 (6th

Cir. 1964); Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsborough,

228 F. 2d 853 (6th Cir. 1956); Taylor v. Board of Education

of New Rochelle, 191 F. Supp. 181, 192 (S. D. N. Y., 1961),

affirmed 294 F. 2d 36 (2nd Cir. 1961), cert, den., 368 U. S.

940; cf. Downs v. Board of Education of Kansas City, 336

F. 2d 988 (10th Cir. 1964), cert, den., —— U. S. ----- - (1965);

Bell v. School City of Gary, Ind., 324 F. 2d 209 (7th Cir.

1963), cert, den., 377 U. S. 924.

For the last few years, the Board has been on the verge

of adopting completely revised zone lines. Based on the

Record in appeal No. 20657, this Court noted the Superin

tendent’s testimony at trial held in November, 1963, that

most dual zones had been redrawn, and “that a major re-

evaluation and redraft of the school districts was in

progress, or about to commence, which would eliminate even

those few dual districts that existed.” Based on this state

ment, the Court concluded appellants’ objections to this

aspect of the plan were more of letter than substance.

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County,

333 F. 2d 53, 55 (5th Cir. 1964).

But in responding to plaintiffs’ interrogatories in Janu

ary 1965, the Board reported that the revision of the at

18

tendance areas was still in the planning and development

stage, although it was expected to be submitted for Board

approval in February 1965 (R, 273). Testimony at the

hearing, concluded March 5, 1965, indicated that only a few

zones have been redrawn (R. 250), but the expected com

plete revision was frequently cited to explain why many

zones remained unchanged (R. 140, 154-56, 222-24).4

4 While the Board promised to provide appellants with the revised

attendance areas upon publication (R. 273), they have not done so to

date. Moreover, appellants’ attorneys are advised that several Negroes

were denied admission to desegregated schools for the 1965-66 school

year because they did not reside in zones served by white schools. At

least one of these parents, Mrs. Gwendolyn Jones, 343 N. Ozark Street,

Whistler, Alabama, wrote the Board on April 23, 1965, protesting their

refusal to enroll her son, Brian Jones, in the white Whistler School.

Following is Mrs. Jones’ affidavit recording her efforts to obtain a de

segregated education for her son in 1965:

State of A labama )

County of Mobile )

Before me the undersigned authority personally came and ap

peared and after being by me first duly sworn deposes and says:

My name is Mrs. Gwendolyn Jones. I live at 343 N. Ozark Ave

nue, Whistler, Alabama. I am 25 years of age.

On April 22, 1965, about 1 :00 p.m., I went to the Whistler Ele

mentary School, white, to pre-register my son, Brian Jones.

After arriving at the school, I entered a class room where other

parents, all white, were registering their children. Three white

women and one white man were registering the children.

I was given some papers to fill out. After I had finished with

the papers, they asked about the birth certificate. Two of the

ladies said that the birth certificate was not the right color. They

gave it to the man and he said that it was in order. The man then

went and pulled out a map and said that I was not in the district

for my son to attend the Whistler Elementary School. I then left

the campus of the school.

My son must go to the Martha Thomas Elementary School, Negro,

which is about two miles from my home. I only live about three

blocks from the Whistler Elementary School.

I am hopeful that something may be done to prevent the enforce

ment of this ridiculous and discriminatory assignment of my child.

/ s / Mbs. Gwendolyn J ones

Mbs. Gwendolyn J ones

Subscribed and sworn to before me

this 27th day of April 1965.

19

2. Pupils in rural sections of Mobile County are effec

tively retained in segregated schools by bus routes which

serve neighborhoods generally defined by race (R. 70, 154).

The Board has not provided pupils in such rural areas with

any information as to how they can obtain initial assign

ment to desegregated schools. Their continued assignment

in accordance with segregated bus routes is no less a vio

lation of standards set by this Court than is the maintenance

of urban zone lines based on race.

3. The assignment of high school pupils in accordance

with segregated feeder lines (R. 138-39, 336-37), clearly

violates both the general requirements to terminate racial

criteria in assignments and specifically violates standards

set by this Court requiring either that pupils be permitted

to choose the nearest Negro or white school, or that they

be assigned to the nearest school to their residence without

reference to race or color. Gaines v. Dougherty County

Board of Education, 334 P. 2d 983 (5th Cir. 1964). Such

standards may not be met by granting transfers to pupils

residing in formerly dual zones (R. 37, 151), particularly

when such policy is not contained in the Board’s plan, was

said to have been applied to students whose transfer re

quests were granted (R. 224), and was not applied in at

least two cases where the white school was overcrowded

(R. 271-72), even though overflow white pupils within the

zone were transported to another white school (R. 158-60).

4. The option to attend either the elementary school

serving the zone of the pupils’ residence, or the school

formerly serving members of the pupils’ race (R. 8) can

serve only to maintain segregation providing as it does a

choice between two Negro or two white schools for virtually

all pupils, and enabling only an effective choice of a seg

regated school for the few students who reside in school

zones in which the opposite race predominates. This Court

20

condemned such one way transfer options in Bosun v. Rippy,

285 F. 2d 43, 46 (5th Cir. 1960), for reasons little different

than those used by the Supreme Court in voiding a similar

provision in Goss v. Board of Education of the City of

Knoxville, 373 U. S. 683.

5. The right to transfer from schools to which pupils

are initially assigned by race is severely hampered by the

transfer criteria included in the Board’s plan. Applica

tion of any of the myriad of these standards (R. 5-6) to

transfer requests filed by Negro pupils seeking admis

sion to white schools is invalid under the decisions of this

Court when white pupils may gain admission to such

schools merely by showing up when school opens (R. 193,

215), or even weeks after school has begun (R. 284-86).

6. The Board’s requirement that transfer applications

can be obtained only at the School Board offices by parents,

constitutes an onerous requirement which effectively lim

its desegregation. While the district court eliminated the

further Board requirement that parents must personally

return the transfer applications to the Board office, the

failure of the Board to permit Negro parents to request

transfers to obtain a desegregated education for their

children on the same basis by which parents are able to

obtain transfers for change of residence, i.e., by bringing

the child to the school on opening day (R. 193, 215) vio

lates standards set by this Court in Lockett v. Board of

Education of Muscogee County, 342 F.2d 225, 229 (5th

Cir. 1965); Calhoun v. Latimer, 321 F.2d 302 (5th Cir.

1963); Stell v. Savannah-Chatham Board of Education,

333 F.2d 55, 65 (5th Cir. 1964).

7. For the same reason, the Board’s requirement that

pupils seeking desegregated transfers must apply during

a two week period from April 1 to April 15 constitutes an

“onerous requirement” in the light of uncontradicted testi

21

mony that Negro parents, upon whom the Board’s plan

places the major burden for any desegregation that occurs,

are handicapped by the early transfer period (R. 107).

While the Board maintains that planning for the forth

coming school year requires the early date, the number

of persons seeking desegregated transfers has been small

in relation to the 500 transfer requests for reasons other

than desegregation, and far smaller than the two to four

thousand pupils who each year are permitted to change

schools by the Board when they change residences (R. 215,

192-93).

8. Transfer criteria utilized by the Board include stand

ards subjecting pupils seeking desegregated assignments

to the possibility of tests (R. 5-6) and evaluation of achieve

ment records (R. 6-7) not required students assigned to

schools on the basis of race, and exposes them to at least

the threat that the Board may conclude the applicant

physically or mentally incapacitated to benefit from further

normal schooling, a determination that could terminate

the pupils’ enrollment at any school (R. 7-8).

9. The small number of applicants seeking admission to

desegregated schools, due appellants submit, to the rigidity

of the Board’s assignment and transfer policies, justifies

departure from the minimum standards set by this Court

for stair-step desegregation in Stell v. Savannah-Chatham

Board of Education, 333 F. 2d 55 (5th Cir. 1964), and

acceleration to enable pupils in all twelve grades to obtain

such transfers by the 1966-67 school year as authorized

by the federal standards adopted in Price v. Denison In

dependent School District, ------ F. 2d ------ 5th Cir. No.

21632, July 2, 1965).

10. Students entering the system for the first time are

not permitted to enroll in desegregated schools under the

Board’s plan unless they are eligible to attend grades

22

already desegregated (R. 4). This Court, for several years

has required that students coming new to the system must

not be required to enter a segregated school. Lockett v.

Board of Education of Muscogee County, supra, at 228;

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction of Escambia

County, Florida, 306 F. 2d 862 (5th Cir. 1962).

11. The Board’s plan fails to contain a provision

enabling Negro students to obtain transfers to desegre

gated schools in order to obtain courses not available at

the schools where they were initially assigned, as required

by this Court. Acree v. County Board of Education of

Richmond County, Georgia,------F. 2 d ------- (5th Cir. No.

22723, June 30, 1965); Price v. Denison Independent School

District, ------ F. 2d ------ (5th Cir., No. 21632, July 2,

1965) (App. §V , E4a(4)) ; Gaines v. Dougherty County

Board of Education, 329 F. 2d 823 (5th Cir. 1964). Such

a provision is particularly needed in appellees’ school sys

tem in which 75 special courses are offered, 45 of which

are available only in white schools (R. 322-25). The

Board contention that no requests for transfer to obtain

special courses have been received is less than adequate

in the absence of some notice that such requests would

be honored.

12. The Board not only fails to provide for teacher

desegregation in its plan, but contends that assignment of

teachers on a non-racial basis would create serious prob

lems connected with race, both in the classroom and the

community (R. 200-01). While this Court had not reversed

district courts who failed to require teacher desegregation

at the time the Board’s plan was approved, there has

never been doubt in this Circuit that teacher desegrega

tion is an appropriate and necessary component of the

relief required by the Brown decision (Board of Public

Instruction of Duval County v. Braxton, 326 F. 2d 616

23

(5th Cir. 1964), cert, denied 377 U. S. 924), and resistance

to any aspect of school desegregation based on fear and

community opposition has never been condoned. Cooper

v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1. In adopting as its minimum stand

ards for desegregation plans, the Guidelines published by

the United States Department of Health, Education, and

Welfare, see Price v. Denison Independent School District,

supra, the question of whether teacher desegregation would

be included as a part of this Court’s minimum standards

was removed from the area of debate.

Appellants do not here complain about mere technical

violations of abstract principles. The invalid provisions

of the Board’s plan reviewed above serve to bar an ascer

tainable number of appellants and other Negroes from

enjoying their constitutional right to complete their pub

lic school education in desegregated schools, and the plan’s

complexity, contradictions combined with the Board’s arbi

trary method of administration doubtless discouraged many

others from even applying.

During the 1963-64 school year when the Board finally

was required by court order to produce a desegregation

plan on August 19, 1963 (R. 1), the transfer period dead

line previously set for July 31 (R. 8-9), was not altered

until the district court specifically required the Board to

accept transfer requests for a five day period (R. 99,

Appeal No. 20657). No further consideration was given

to the 25 or 30 applications filed earlier in the year and

denied (R. 104). Two Negro students wTere admitted to

one high school and were subjected to harassment and

threats throughout the school year (R. 106).

During the 1964-65 school year, the Board received ap

plications for transfer to desegregated schools from only

16 Negro pupils (R. 270-72). But despite the small nurn-

24

ber of applicants, the Board granted only seven transfers

and denied nine.

Four Negroes were turned down because they did not

reside in the attendance area served by the school to

which they sought transfer (R. 271), even though (1) the

Board’s pupil transfer form indicated that any school

could be requested (R. 319), (2) Board personnel from

whom parents had to both obtain and submit the forms

in person (R. 5), failed to advise them that their request

must be made to a particular school, and (3) neither the

Superintendent, nor his assistant in charge of transfer

procedures, was able or even willing (R. 221) to provide

information as to which schools Negro high school pupils

seeking desegregated educations should apply.

Three applications of pupils in the 11th or 12th grade

were denied because filed during the 6 day transfer period

in August required by district court order. Notwith

standing both the express wording and clear intention of

this Court’s June 18, 1964 opinions, the Board took the

position that the additional transfer period would be lim

ited to pupils in the first and 10th grade because pupils

in the 11th and 12th grades had been given the April 1-15

period in which to apply for transfer (R. 107).

Finally two transfer applications were denied because,

according to the Board, facilities at the Adelia Williams

High School where transfer had been sought were already

beyond capacity and children were being transported

from the Williams School because of this condition (R.

271-272). Despite letters from the parents of both trans

fer applicants specifically requesting transfer to either of

two other high schools, which letters clearly show that

the parents’ primary desire was to obtain transfers to

desegregated schools rather than any particular school

25

(R. 313, 316), the Board took no further action on the

transfer requests.

But a better understanding of the difficulties the Board’s

plan posed for Negro parents will be found by tracing

the efforts appellant Algea Bolton made to enroll his

daughter May Wornie in a desegregated school. Early in

1963, appellant sought to obtain a transfer for his daugh

ter from the Negro St. Elmo High School located 17 miles

from her home (R. 93) to the white Baker High School,

4 miles away. The Negro high school principal refused

the transfer. Subsequently, Bolton’s daughter attempted

to enroll at the Baker School but was turned down by the

school principal. A further letter to the Assistant Super

intendent was also denied. The Superintendent testified

that over-crowded conditions at Baker prompted denial

(R. 81), but conceded that white pupils seeking admission

at Baker were assigned to another white school (R. 82).

Mr. Bolton’s experiences were set forth in the com

plaint of this case in which he and his daughter became

plaintiffs. During the transfer period for the 1964-65

school year, in April 1964, appellant Bolton requested a

transfer for his daughter to Davidson School (R. 91-92).

Unaware that the transfer application had to be signed

by both parents, Mr. Bolton was required to make two

trips to the Board’s offices located 10 miles from his home,

a total of 40 miles (R. 92). The transfer request was

subsequently denied and the Board advised him that he

did not reside in one of the attendance areas served by

the Davidson School (R. 271). For the 1964-65 school

year, May Wornie Bolton was assigned to the just com

pleted all Negro Hillsdale Heights High School located

quite close to her home (R. 93). Mr. Bolton again applied

for a transfer to the Davidson school for the 1965-66

school year (R. 94). The transfer request was denied.

26

This was the Bolton girl’s last chance. She is enrolled in

the Hillsdale Heights School for her senior year (E. 74,

95) and is scheduled to graduate in June 1966. Thus, May

Wornie Bolton who entered the segregated Mobile public

schools only a few months after the Supreme Court’s

historic school desegregation decision in 1954 will gradu

ate without having ever enjoyed the rights it was intended

to confer, and this despite the courage and perseverance

exhibited by both she and her father. Is it any wonder

that a majority of Negro parents in Mobile reach the

conclusion that their children can receive an education in

a segregated school no different than that offered the

Bolton child and with far less effort, expense, worry and

risk?

The Bolton’s experience is not unique, nor unfortunately

is the record in this case. This Court has reviewed the

Bolton-type experience and the Birdie Mae Davis-type

record on many occasions during the years since 1955. In

deed, appellants suggest that it was after reviewing the

quite similar record in the Jackson, Mississippi school case

that this Court, while granting an injunction pending that

case’s third appeal in two years, decided in retrospect that

“the second Brown opinion clearly imposes on public school

authorities the duty to provide an integrated school sys

tem,” and concluded that Judge Parker’s frequently quoted

dictum (“The Constitution,. . . does not require integration.

It merely forbids discrimination.” ) must be laid to rest.

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District,

------ F. 2d ------ (5th Cir. June 22, 1965).

The Board’s contrary position as to its obligations to

appellants and their class under Brown provides a major

clue to what to date has been the utter failure of school

desegregation in Mobile. Their pleadings deny that Negroes

have a “ right” to a desegregated education to the exclusion

27

of other proper factors (R. 22), and at the hearing, the

Board’s attorney strenuously denied that the court orders

in this case provided Negro pupils assigned by segregated

feeder lines to Negro schools with a right to choose white

schools (R. 163, 174). In the same vein, the Superintendent

repeatedly sidestepped direct questions as to whether new

elementary zones (R. 84, 273), would be drawn with a con

scientious effort to alter the uniracial characteristics of

present zones (E. 154-56), and his assistant blithely an

nounced that assignment of high school pupils by segregated

feeder system would continue (E. 236-37).

But the district court approved the elementary zone lines,

the initial assignment options, and the general transfer

procedures as non-discriminatory (R. 28-31). Despite the

Superintendent’s admission of widespread use of long

distance busing such as that used to transport Negro high

school students from the Hillsdale area 34 miles each day

past white schools to the St. Elmo School (E. 156-57), and

the effect of the option plan, the only worthwhile use of

which enabled pupils to choose segregated schools when

the school to which thejr otherwise would be assigned were

populated by pupils of the opposite race, the court below

found the Board was adhering to a longstanding practice

of “neighborhood school organization” (R. 29). The court

noting Board denial of more than half of 500 pupils seeking

transfers for reasons not connected with desegregation,

concluded that denial of nine of sixteen Negroes seeking

transfers under the Board’s desegregation plan was a “nor

mal proportion of denials” (R. 30), and in similar fashion,

found no fault with Board procedures and policies, all of

which are contrary to the standards set by this and other

federal courts.

As with the Board perhaps the real basis for the errors

in the district court’s ruling is its use of fallacious stan

dards. The court quoted from Briggs v. Elliott, supra, and

its progeny (R. 35-40), and tested the Board’s actions hy

these early opinions, ignoring the more recent and, appel

lants submit, more enlightened standards contained in

Lockett v. Board of Education of Muscogee County, supra;

Gaines v. Dougherty County Board of Education, supra,

and the Supreme Court decisions upon which these deci

sions rely.

Relief

For appellant Mae Wornie Bolton and a great number

of other Negro pupils there can be no effective reversal of

the district court’s approval of the Board’s plan. Their

opportunity to obtain the educational and psychological

benefits of a desegregated public school education to which

they were constitutionally entitled are forever lost. The

immeasurable value of competing in the same classroom

with white children experienced by Birdie Mae Davis and

Rosetta Gamble are lost as well. They are lost despite the

Supreme Court’s decision in Brown written more than 11

years ago, and lost despite the many decisions by this Court

intended to secure the rights established in 1954. The cou

rageous efforts of a civil rights worker like John LeFlore

and determined parents like appellant Algea Bolton are

simply not enough to break through the maze of adminis

trative barriers erected by the Board.

Indeed, in Mobile, as in Atlanta, New Orleans, Houston,

Dallas and other large urban centers, the school systems

are too complex and the quality of legal skill available to

school boards too high to effect meaningful school deseg

regation without constant litigation, during most of which

the school board assignment and transfer policies remain

at least one full step ahead of the Negro plaintiffs’ efforts

to contest them in court.

29

This Court thus may invalidate the appellee Board plan,

provisions of which obviously are contrary to established

standards, but such relief will not cure harm already done

under the plan nor, based on its past record, will the Board

lack the ingenuity to replace the stricken policies with new

procedures equally effective, probably more sophisticated,

and likely to result in far more litigation than desegre

gation.

Thus the issues presented in this the fourth appeal of

this case in three years raise the further issue as to what

form of relief is necessary to bring about effective school

desegregation in large school systems such as Mobile.

Perhaps eventually procedures in enforcing Title VI of

the 1964 Civil Bights Act will enable federal courts to dele

gate such problems to technical agencies qualified to handle

them in expert fashion. But at present the Office of Edu

cation is too small and too overburdened to undertake such

a task. For the present, appellants suggest the gap be

filled by a procedure adopted by District Judge Luther

Bohanon in the Oklahoma City school desegregation case.

Seeing the need for a detailed desegregation plan and fail

ing in efforts to get the school board to prepare such a

plan, Judge Bohanon permitted plaintiffs to suggest names

of well-qualified educators who, after a hearing on their

qualifications, were appointed by the court to conduct an

objective, impartial survey of the Oklahoma City School

system and prepare a report containing educationally sound

recommendations as to how the school system could be

effectively desegregated. A report was prepared and, after

a further hearing, at which time the educational experts

were closely examined by both school board attorneys and

the court, their report was adopted and the board ordered

to submit a desegregation plan incorporating recommenda

tions in the report. Dowell v. Board of Education of the

30

Oklahoma City Public Schools, ------ F, S u pp .------ (No.

9452, W. D. Okla., Sept. 7, 1965).

School officials may and probably will oppose the rec

ommendations contained in the report (the Oklahoma

City School Board on September 20, 1965 appealed Judge

Bohanon’s decision), and not every district court will ap

prove the recommendations made, but at the least, the

procedure followed in Oklahoma City will enable this

Court to review on appeal plans designed by well-qualified

experts in the field to eliminate school segregation. This,

appellants submit, will be a worthwhile and hopefully

beneficial change from the constant parade of schemes

designated as “desegregation plans” but actually intended

to maintain segregation for as long as possible.

Appellants realize their suggestion for relief places on

them at least a share of the burden of desegregating the

public schools which the Supreme Court in Brown placed

on school boards. But the burden assumed does not ma

terially increase the burden of continuous litigation with

which appellants have already been burdened for so long

with so little result.

CONCLUSION

W herefore, for all the foregoing reasons, appellants

submit that the order of the court below approving the

Board’s desegregation plan be reversed with instructions

to require the Board to prepare for the 1966-67 school

year an interim freedom of choice plan for all twelve

grades with criteria at least as broad as those contained

in the H.E.W. Guidelines adopted by this Court in Price

v. Denison Independent School District, ------ F. 2d ------

(5th Cir. 1965). This plan shall remain in effect while

qualified educational experts sleeted by appellants and

31

approved by the district court conduct an objective, im

partial survey of the school system and prepare a report

containing recommendations for the elimination of racial

segregation. If after hearing these recommendations are

found to be educationally sound and administratively

feasible, the court shall order the board to incorporate

them in a final desegregation plan.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

Derrick A. Bell, Jr.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

V ernon Z. Crawford

578 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama

Clarence E. M oses

1050% Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama

Attorneys for Appellants

32

Certificate of Service

This is to certify that the undersigned, one of appel

lants’ attorneys, on this date, September 27, 1965, has

served two copies of the foregoing Brief for Appellants

on George F. Wood, Esq., 510 Van Antwerp Building,

Mobile, Alabama, by mailing same to the above address

by United States air mail, postage prepaid.

Attorney for Appellants

MEIIEN PRESS INC, — N. Y. C. an.