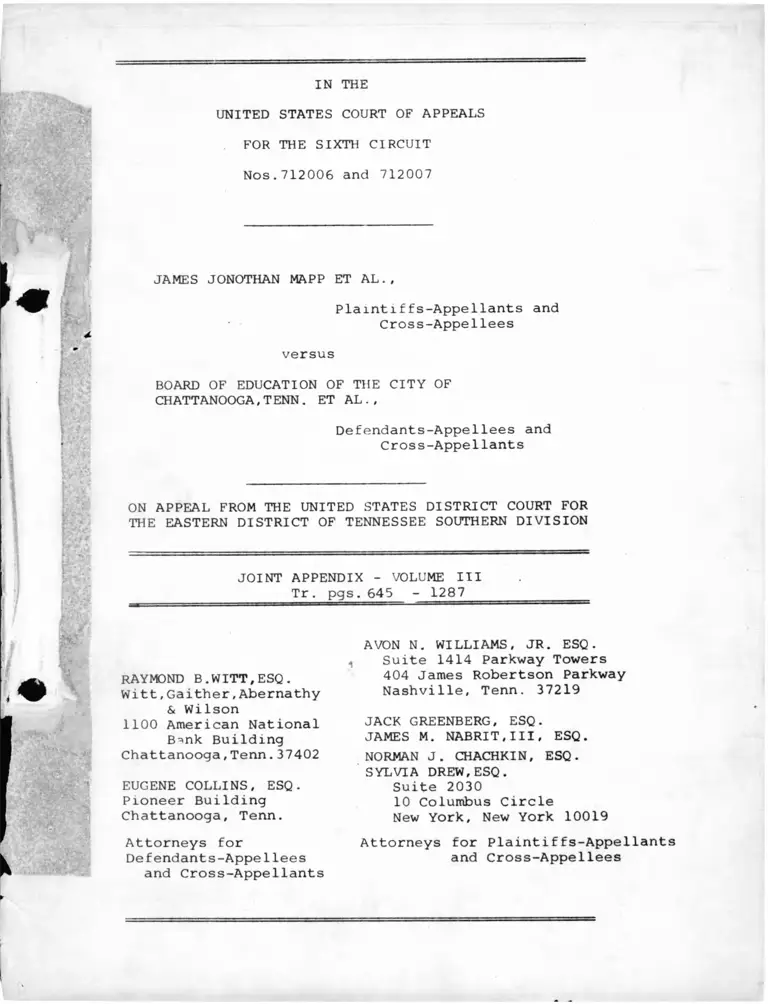

Mapp Et Al v Board of Education of the City of Chattanooga TN Joint Appendix Volume III

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964 - January 1, 1971

649 pages

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Mapp Et Al v Board of Education of the City of Chattanooga TN Joint Appendix Volume III, 1964. 8c677302-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4d7ea6a5-6c55-4d57-be25-e873e4089062/mapp-et-al-v-board-of-education-of-the-city-of-chattanooga-tn-joint-appendix-volume-iii. Accessed February 01, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Nos.712006 and 712007

JAMES JONOTHAN MAPP ET AL. ,

Plaintiffs-Appellants and

Cross-Appellees4

versus

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF

CHATTANOOGA,TENN. ET AL.,

Defendants-Appellees and

Cross-Appellants

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE SOUTHERN DIVISION

JOINT APPENDIX - VOLUME III

Tr. pgs. 645 - 1287

RAYMOND B.WITT,ESQ.

Witt.Gaither,Abernathy

& Wilson

1100 American National

B^nk Building

Chattanooga,Tenn.37402

EUGENE COLLINS, ESQ.

Pioneer Building

Chattanooga, Tenn.

Attorneys for

Defendants-Appellees

and Cross-Appellants

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR. ESQ.

Suite 1414 Parkway Towers

404 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tenn. 37219

JACK GREENBERG, ESQ.

JAMES M. NABRIT,III, ESQ.

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN, ESQ.

SYLVIA DREW, ESQ.

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

and Cross-Appellees

I N D E X

Witness Page

GEORGE W. JAMES

Direct Examination by Mr. Witt............... 645

Cross Examination by Mr. Williams............ 671

Redirect Examination by Mr. Witt............. 702

Recross Examination by Mr. Williams.......... 704

Redirect Examination by Mr. Witt............. 708

Recross Examination by Mr. Williams.......... 709

CLIFFORD LEE HENDRIX, JR.

Direct Examination by Mr. Witt............... 711

Cross Examination by Mr. Williams............ 716

FRANKLIN SCANLON McCALLIE

Direct Examination by Mr. Witt............... 720

Cross Examination by Mr. Williams............ 730

Redirect Examination by Mr. Witt............. 746

Recross Examination by Mr. Williams.......... 754

CLAUDE CONKLIN BOND

Direct Examination by Mr. Witt............... 758

Cross Examination by Mr. Williams............ 769

Redirect Examination by Mr. Witt............. 817

Recross Examination by Mr. Williams.......... 827

Redirect Examination by Mr. Witt............. 835

Recross Examination by Mr. Williams.......... 836

JAMES B. HENRY

Direct Examination by Mr. Witt............... 839

NO. Description

For

Id.

In

Evd.

49 Letter mailed to Director of

requesting recruiting date

Placement

647 647

50 Follow-up letter to visit on campus 649 649

M I f H I ' M K H I <• i H > Nfr P< ■ f H

1 n i l s I n S I M I M ( \ " M!

j

itjjj ii.

I N D E X (continued)

;i

No.

j

EXHIBITS (continued)

For InDescription Id. Evd.

«ii "Recruiting, 1970-71" 650 650

t 52i

J

"Chattanooga Public Schools Offer

You" 652 652

i 53

1

Eligibility evaluation form 653 653

•1 5 4 Application forms 654} 654

y 55 Form letter A, Recruiting 657 657

‘ 56 Form letter B, Recruiting 659 659

1 : 57 Form letter C, Recruiting 660 660

I I j 58 Form letter D, Recruiting 661 661

i | < 59 Form letter K, Recruiting 662 662

1i

' 1

|

60 Reference forms 666 666

1 . ! 61 Portfolio of school policies at■i Howard High School 714 714

1

i 62 Document 725 725

i •.

63 Statement 736 736

•

1 1

64 Press clipping 737 737

•

65 Materials containing transfer policies

used by School Board 796 796

i

|

1- |!

j

•

66 Civil Rights Coassittion * s publication 832 832

V

ji

ii ' 1 ^ ’ 1 M . ' . l A i f t , L>l S f W l*’. T f O i w i

i.

I N D E X

Witness Page

JAMES B. HENRY

Cross Examination by Mr. Williams..

Redirect Examination by Mr. Witt...

Recross Examination by Mr. Williams

Redirect fixami nation by Mr. Witt...

Recross Examination by Mr. Williams

858

892

915

930

935

JAMES HENRY HEUSTESS

Direct Examination by Mr. Witt....

Cross Examination by Mr. Williams..

Redirect Examination by Mr. Witt...

Recross Examination by Mr. Williams

946

1015

1026

1027

j a m e s d . m c c u e l o u g h

Direct Examination by Mr. Witt...

Cross Examination by Mr. Williams

Redirect Examination by Mr. Witt.

1028

1039

1061

No.

EXHIBITS

inscription

For

Id.

In

Evd.

67 Letter from Dr. Martin to Director

of Equal Educational Opportunities

of the State of Tennessee 860 860

68 Newletter from the Nashville Center

for Research and Information on Equal

Education Opportunity 930 930

69 Current status of desegregregating

teaching staffs 960 960

70 "Chattanooga Public Schools, Chatta-

nooga, Tennessee, Statistical Reports

on Staff Desegregation, Chattanooga

Public Schools, 1970-71" 974 974

71 "Vacancies to Date, 76“ 1006 1006

• A l C O O « *■ p o m i e h

MRS. NITA LAWSON NARDO

Direct Examination by Mr. Witt............. 1072

Cross Examination by Mr. Williams.....!.!.! 1127

Redirect Examination by Mr. Witt........... 1167

HOUSTON CONLEY

Direct Examination by Mr. Witt............. 1169

Cross Examination by Mr. Williams.......... 1181

Redirect Examination by Mr. Witt........... 1186

ROBERT ARMSTRONG TAYLOR

Direct Examination by Mr. Witt............. H89

Cross Examination by Mr. Williams.......... 1216

Redirect Examination by Mr. Witt........... 1231

RecroBS Examination by Mr. Williams........ 1234

DEAN HOLDEN

Direct Examination by Mr. Witt............. 1236

YALE RAVIN

Direct Examination by Mr. Williams......... 1239

DEAN HOLDEN

Direct Examination by Mr. Witt (continued)... 1265

EXHIBITS

For InNo. Description Id. .

i.

I N D E X

Witness pn3?

72 Proposal of Chattanooga Board of

Education dated December 30, 1964 1075 1075

73 Proposal regarding School Board

grant for programs in education

submitted to HEW on May 19, 1965 1086 1086

74 Team-teaching proposal transmitted

April 27, 1966 1094 1094

ii.

I N D E X (continued)

EXHIBITS (continued)

t-

o'!Z

1 Description

For

Id.

In

Evd.

75

!

"Chattanooga Public Schools, Chatta

nooga, Tennessee, Staff Desegregation

Report, May 1, 1967 1105 1105

76

i

List of teachers 1110 1110

• 77 "Staff Desegregation Report" 1110 1110

78

i

Memorandum from Dr. Martin to

all professional staff personnel 1115 1115

i 7 9

t

"Proposal for School Board Grant

Program on School Desegregation

Problems" 1124 1124 1

80 "Special Program for Educational

Executive Development Prospectus" 1173 1173

■ 81 In-service training pamphlet 1179 1179

i 82 Document dated April 12, 1971,

addressed to Dr. James B. Henry 1178 1178

83 Summary statement 1199 1200

, 84 Listing of personnel of Clara

Carpenter Elementary School 1206 1206

•

85 Material regarding students

currently being trm s ferred to

areas by race 1235

i1

l<si35

86!

|

Information regarding applications

on file as of May 12, 1971, for

teaching positions 1236

•i

1236

i 87 Request form for transfer 1238 1238 |

1 88 Resume of Mr. Ravin's experience 1241 1241

i

i 89 Census map 1245 1256

| 90 Tabular representation of the census 1248 1248

iii.

I N D E X (continued)

EXHIBITS (continued)

No. Description

For

Id.

In

Evd.

91 Document 1255 1255

92 Form 1266 1266

93 "Revised Policies Governing Out-of-

Zone Enrollment" 1271 1271

94 "Zoning Policies" 1272 1272

95 School Year Bulletin, 1970 1274 1274

96 "Pupil Accounting, Part 1" 1275 1275

97 Policy governing the transition

of single school zone lines

implementing the Chattanooga plan

of desegregation 1276 1276

98 Information regarding transfers 1279 1279

1 645

2

4

5

(i

7

8

!)

10

11

12

FOURTH DAT OF TRIAL

May 12, 1971

WtdMiday,

9:00 O'clock, A. M.

(Thereupon, pursuant to adjournment on Tuesday,

May 11, 1971, court reconvened, and the following proceedings

were had, to-wit:)

GEORGE W. JAMES,

called as a witness at the instance of the defendant, being

first duly sworn, was examined and testified as follows:

BY MR. HITT:

DIRECT EXAMINATION

14

r>

Hi

17

IS

I '•

20

21

Q State your name, please.

A George W. Jams.

Q By whom are you employed?

A Presently employed by the Chattanooga Public

Schools.

Q And, in what capacity are you employed?

A I am Director of Professional Personnel.

Q How long have you been in that capacity?

A About 13 months.

Q Now, in your present capacity as Director of

Professional Personnel with the Chattanooga school system,

would you describe your present responsibilities?

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

1

2

3

4

5

(i

7

8

!)

10

11

12

13

14

1'.

Hi

IT

18

1 ! »

20

21

23

21

•j . i

James - Direct 646

A My present responsibilities primarily are

coordinating teacher recruitment, teacher placement, and

working very closely with principals and other administrative

heads of — to determine their needs.

Q Now, how do you go about attempting to discharge

this responsibility?

A Hell, we visit the various colleges and universitd

in primarily the southeastern part of the United States.

MR. WILLIAMS: I am not hearing very well.

THE WITNESS: He visit the colleges and university

in the southeastern part of the United States, primarily.

BT MR. WITT:

Q Do you communicate with these colleges prior to

your visit?

A Yes, we correspond with the placement directors

and schedule recruiting dates and visit them — visit the

campuses to talk with prospective graduates.

Q I hand you a document on the letterhead of the

Chattanooga Public Schools. Would you please identify this?

A Yes, this is one of the letters that we mailed

to the Director of Placement at the various institutions

requesting a recruiting date.

Q Would you make this an exhibit to your testimony?

THE COURT: Exhibit 49.

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L . C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

2

1 is - Direct 647

a

(i

7

8

!)

10

11

12

l.'i

14

l r»

in

17

18

l!l

20

21

2't

21

(Thereupon, the document referred

to above was marked Exhibit Mo.

49 for identification. Witness

Mr. Janes, and received in evident

BY MR. WITT:

Q Mow, Mr. Janes, vould you nans the institutions

to tWxon this letter or siailar letter was sent?

A Sane of the institutions that the letters wore

sent to and that we have visited included Lane College at

Jackson, Tennessee; Alabama State University at Montgomery,

Alabama; Memphis State University at Memphis; Lambert College,

Jackson; Tuskegee Institute at Tuakegee, Alabama; Auburn

University at Auburn; University of Tennessee at Chattanooga;

North Georgia College at Dahlonega; University of Alabama,

Tuscaloosa; Alabama A&M University at Normal, Alabama; Atlanta

University System, which includes, of course, Clark, Morehouse

Spelman, and Morris Brown; West Georgia College at Carlton;

Berry College at Rome; Tennessee State University at Nashvilli

Tennessee Tech at Cookeville; David Lipscomb at Nashville;

Middle Tennessee State at Murfreesboro; Austin Peay at

Clarkvilla; Peabody at Nashville; University of Tennessee at

Athens; East Tennessee State at Johnson City; Knoxville at

Knoxville, Tennessee; Berea at Berea, Kentucky; Kentucky Statl,

Prank fort; Carson-Newman at Jefferson City; Fisk University an

Nashville; Port Valley State, Port Valley, Georgia.

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T F R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

James - Direct 648

I an hoping to leave today for Florida State

University at Tallahassee and Florida A6M University at

Tallahassee and Payne College in Augusta, Georgia, along with

a few others that 1 failed to none.

Q How, are you aware of the publicity that's given

to the student body in advance of your visit?

A Yes.

Q What form does this usually take?

A Usually the placement directors of the various

institutions will circulate the information concerning the

♦’■he interviewers visiting their campuses so that it

will be accessible and made available to the student body.

Q The institutions that you listed, what is the

racial composition? Are you aware of the racial composition

in general of the institutions that you visited?

A Yes, to some extent. I think of the number of

campuses that we have visited or we plan to visit this year,

18 of them are predominately black colleges of the 40, I

believe was 40 — 42 or 43 colleges and universities.

Q Mr. James, I hand you another, appears to be a

form letter over your signature and ask you to identify this,

please.

A Yes, this is a follow-up letter that we sent

after having confirmed the date of our visit and acknowledging

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

1

2

3

4

5

(i

7

8

!l

10

11

12

13

14

ir>

10

17

18

lit

jo

21

• >•>

23

24

2">

Jamas - Direct 649

to visit the campus.

THE COURT: Exhibit No. 50.

(Thereupon, the document referred

to above was marked Exhibit No.

50 for identification, witness Mr.

___ James, and received in evidence.)BY MR. WITT:

Q Now, are the students advised of your visit in

our appreciation to them for providing ua with the opportunity

advance?

A Yes.

0 What — in what manner, what procedure is usually

followed to advise the students that you are ooming?

A Well, prior to our visit, we would have made

contact with the placement officer at least a month or two

in advance. A week prior to our visit, we, of course, will

send them our printed material, a small brochure, and two or

three days in advance, we will call them long distance to

ask how many persons we have on our schedule. This is done

to determine the number of interviewers that we should send.

Q I hand you a document entitled "Recruiting, 1970-'

Would you please identify this?

A Yes. This recruiting schedule was completed

about the first of September. We began to work on this in

July and completed it about the first of September. If you

know, we begin our recruiting in October and will terminate

i 1

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

Janes - Direct 650

it mid-May. t

0 Mould you maka this exhibit, I believe, mould be

No. 51, to your testimony?

(Thereupon, the document referred

to above vas marked Exhibit No.

51 for identification, witness Mr.

James, and received in evidence.)

BY MR. WITT;

Q At Memphis state, do you recall approximately

the number of students that indicated interest in interview?

A I believe w talked with possibly ten or twelve

persons at Msmphis State.

Q Would there be — would this be an average number

or would there be such a thing as an average number?

A That is approximately the average number. We

could possibly have talked with maybe twelve or thirteen.

0 Bow long would the average interview require?

A Twenty-five to thirty minutes. Actually, it*a

at 30-minute intervals, but we allow 25 minutes for the

interview and 5 minutes to evaluate the interview and co^ile

our material.

0 During this interview, you give any material to

the — excuse me. I hand you a document, printed pamphlet,

entitled "Chattanooga Public Schools Offer You.* Would you

please identify this?

A Yes, this is a little samll, we cell it, brochure,

R I C H A R D S M I T H O E F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

James - Direct

really, nothing but a pamphlet. It was dona very hurriedly

just prior to our beginning recruiting schedule. He nailed

this to thee prior to the interview to give thee soae back-

ground and some information about the Chattanooga Public

Schools.

At the termination of the interview, we also give

fK— one of these as well as an application and suggest that

they read this carefully as they consider us and also complete

an application.

q nr. James, what kind of questions do the students

n««k you during the course of these interviews?

A Well, normally they will ask something about the

public schools, the Chattanooga public schools, the type of

system, something about the pay scale, something about the

community, its climate, and very seldom, we anticipate

questions about the cultural climate of the community, but

we don't often get that.

We do find sometimes a greatly number of them

are interested in their continuing — their continuing their

education. They will ask something about our graduate school

the close proximity to nearby metropolitan cities where

they can continue with their education and this type of thing.

q Do you have an evaluation form to use during the

course of these on-campus —

*51

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

J

4

■)

(i

s

10

11

12

12

14

l.r*

Hi

17

18

1!>

20

21

20

21

2'*

Jess»s - Direct 652

A (Interposing) Yea.

0 (Continuing) — evaluations?

A Yes, we do. And —

0 (Interposing) I beg your pardon. Would you make

the pamphlet exhibit —

THE COURT: (Interposing) Pifty-two.

(Thereupon, the document referred

to above tree marked Exhibit Ho,

52 for identification. Witness Mr.

James, and received in evidence.)

BY MR, WITT:

Q Pifty-two, please.

A We have what we call an on-ernepus eligibility

evaluation form and on this form, of course, we get oartain

personal data information such as permanent address, because

most of them are graduating seniors and we need to know their

permanent addressi the type of degree that they are getting,

their major, something about their overall academic record.

Some institutions provide us with an on-campus

interview form that we can keep and some don't, so depending

upon whether or not we can bring this on-campus form with us

is dependent upon whether we get this information. Of course,

we need to get some feedback as to their interest and extra

curricular activities. Along with that, we get some other

information about their physical and personal personality

characteristics as well as aptitude and professional outlook

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

1 653

R

f

from a standpoint of najor fiald interests and teaching

philosophy and thsir intsrsst in teaching and it’s a checklist

Janes - Direct

4 typo of thing, dealing with behavioral patterns primarily.

5 Q would you make this Exhibit Ho. 53 to your

11 testimony?

i

s

!>

(Thereupon, the document referred

to above was marked Exhibit No. 53

for Identification, Witness Mr.

James, and received in evidence.)

10

11

12

i:t

H

15

BY MR. WITT:

Q Now, as a result of this interview, do you prepare

this evaluation?

A Well, it is prepared in the Division of Staff

Personnel.

Q well —

ir. A (Interposing) You talking about the —

17 Q (Interposing) Directing your attention to the

18 reverse side of the interview record?

10 A Yes, yes, yes , the suasoary comments.

20 Q Yes.

21 A Yes, yes.

*>•> Q And, you make the determination with reference

28 to your judgment as to —

21 A (Interposing) Right.

Q (Continuing) — the appearance and poise and

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

Janes - Direct 654

other Betters?

A Right, tie do this.

Q And, these are subjective judgments upon your

part?

A Right.

Q Are they?

A Yes, yes, sir.

Q Mow, in the course of these interviews, do you

deliver to the interviewees an application form?

A Yes, we do, we do. And, we give all of the

persons that we interview an application form and suggest that

they cocaplete it and indicate to them that we will be very

happy to process it for then.

Q You have one of these application forms —

A (Interposing) Yes, I do.

Q (Continuing) — available? Mould you make this

Exhibit 55?

THE COURT: Fifty-four.

(Thereupon, the document referred

to above was marked Exhibit Mo.

54 for identification, Witness Mr.

James, and received in evidenoe.)

BY MR. WITT:

Q Does this application have instructions attached

to it?

A Yes, we have instructions enclosed.

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

1

I

(i

i

8

!>

10

I I

1J

1.5

n

in

10

17

IS

10

•JO

Jl

J.t

Jl

j;>

Q And, this is — believe this is a pert of this

exhibit, although it's not attached to it?

A Tea, it's included on the inside, separate sheet.

q Do you go over these instructions with the

interviewee, usually?

A Yes, yes, we tell them that the instructions are

enclosed and suggest that they look at thee and if there are

any questions, we will try to answer them for them.

q Mr. James, I notice that at the bottom of the

page entitled "important Instructions to Applicants," there

is a reference to national teacher examination scores. Would

you describe what this is, briefly, the national teacher —

A (Interposing) The national teachers examination

is an examination that is given by the Educational Testing

Service out of Princeton, New Jersey, we, as a school system,

do not require that you make a certain score nor is it a

prerequisite for employment. However, we do require that you

take it during your first year of employment in the Chatta

nooga public school system.

q What does this particular examination attempt to

determine?

A Actually, I would think that maybe — you —

Attorney Witt addressed this question to the Assistant

Superintendent.

Janes - Direct 655

R I C H A R D S M I T H O J C I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

10

11

1:2

l:t

11

ir»

m

17

1H

10

•JO

J1

j:t

J»

jr»

Q Nell, just your understanding of what it attempts

to do.

A I think it measures aptitude and your — measure

area of concentration as well as other areas, allied areas.

Q Is it a guarantee that the person will be a good

teacher?

A I don't think so, personally.

Q Are there other similar tests that could have

been used in addition to the national teacher examination

test?

A Nell, possibly there are; but I think this is the

most acceptable one.

q This is considered the most reliable, then —

A (Interposing) Right, yes, sir.

Q (Continuing) — test? Now, what is the next

step in this recruitment process after you have returned to

Chattanooga?

A The next step in the recruitment process is a

follow-up letter that we send all persons that we have talked

with on the campus. And, of course, we have four types of

letters that we send; and, of course, we refer to them as

A, D, C, D, and £.

The A letter is the more encouraging one. This

is the top letter, of course. This is the one that the

James - Direct 65S

R I C H A R D S M I T H . O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E O S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

1

' I

4

5

(i

7

8

!)

10

11

12

i:s

14

ir»

Hi

17

18

1 ! »

20

21

•>•>

20

21

2>

prospect, we really want.

0 I hand you a form lattar that haa tha lattar "A*

on it.

A Right.

Q Would you identify this?

A Tea, this is the one that is more encouraging to

the applicant, to the person that we have talked with.

Q Would you make this Exhibit 55?

THE COURT: Fifty-five.

(Thereupon, the document referred

to above was marked Exhibit No. 55

for identification. Witness Mr.

Janes, and received in evidence.)

BY MR. WITT:

Q Now, would you explain to the Court the signiflean

of this letter as compared with the other letters?

A Well, this letter here indicates that we are

highly encouraging to the applicant, to the person that we

have interviewed for an early commitment for employment. Hie

other one, the other ones are not as encouraging as possibly

this one, and we rate them A, B, C, D — actually there is

five — E.

And, what we do, we look at the on-campus evaluati

form and we will grade them, and, of course, give them to the

secretary. And, she will in turn send this letter to, whether

it's an A, B, or C, or D, or E letter.

J«m > - Direct 657

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

Direct <>58

Q What individuals participate in this evaluation

process that you have described other than yourself?

A well, no one but ayself, really, in this particular

type of evaluation, see, because on an occasion, Z night not

have been the person to visit campus. We have principals and

others who will on occasion do sons of the recruiting. There

will be sons ta— recruiting by scow other persons.

Q But, this, you use the tern "we,* Z assume you

meant —

A (Znterposing) Well, Z mean we can determine from

their sum&ary comments and how they have checked the

personality traits of the person that they have talked with

as to whether or not they would, of course, be classified or

rated A, B, C, or d .

Q Why the need for an early commitment?

A Because these persons, Z am sure, are being

considered by other school systems, because they are top

priority people. And, we, of course, want to get them in our

school system.

Q The competition for the good prospect is —

A (Znterposing) Very, very keen.

Q Is this true at most of the institutions that

you visit?

A Yes, yes.

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

1

*»

I

ii

7

8

!l

10

11

12

1.1

14

ir.

n;

17

IS

10

20

21

. »•»

20

24

2f>

James Direct 659

Q Are there any particular exceptions?

A Tes, particularly for black teachers.

Q In what way?

A They are very difficult to recruit, black teachers

are.

Q Now, you nade a reference to another category

letter which you describe as B. I hand you a forts letter that

contains the alphabet letter "B" on it. Is this the B-type

letter that you referred to?

A Tea, yea, this is the B-type letter that we

refer to.

Q Would you sake this Exhibit No. 56 to your

testimony?

(Thereupon, the document referred

to above was marked Exhibit No.

56 for identification. Witness Mr.

James, and received in evidence.)

BY MR. WITT:

Q Now, how is this letter different from letter A?

A Well, actually, there is a difference in —

possibly rather difficult, if you notice, the last paragraph

will explain it and if you would like, I can read it.

Q All right.

A Letter A says, "If there are any steps which you

have not taken to casqplete an application, we hope you will

do so immediately so that we can have the opportunity of

R I C H A R D S M I T H O M I C I A L C O U R T R f c P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

Janes - Direct 660

evaluating your credentials early. Please feel free to call

us — call on us at any time if we can be of assistance to

you."

The B letter says, "If there are any steps which

you have not taken to complete the application, we hope you

will do so immediately. Please feel free to call on us at

any time if we can be of assistance to you."

See, we are not pushing them quite as hard in

B as we are in A.

Q All right. Mow, I hand you another form letter

which ha8 the letter "C" on it. This would be — would you

identify this?

A Yes.

Q This is the C letter that you referred to earlier?

A Yes, this is the letter.

Q All right. Would you make this Exhibit Mo. 58?

THE COURT: Fifty-seven.

(Thereupon, the document referred

to above was marked Exhibit Mo.

57 for identification. Witness Mr.

James, and received in evidence.)

BY MR. WITT:

Q All right. Now, just identify the distinguishing

difference between this letter and letter B.

A All right. The distinction here, as you know I

mentioned A and B, that we had said something about being

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

1 James - Direct 661

encouraging at all. The last sentence in the eeoond paragraph

4 in D A says, "On the basis of your interview, we can be

o highly encouraging to you if you decide that Chattanooga is

<• the place you would like to start your teaching career."

In latter C, the last sentence says, "We hope you

will consider our schools as a place where you would like to

begin your teaching career."

Just a little word difference there, that's all.

q All right. Now, I hand you a form letter labeled

"D." Would you — is this a form letter that you use?

A Tes, this is the form letter.

Q Would you make this Exhibit No. 58?

(Thereupon, the document referred

to above was marked Exhibit No.

58 for identification, Witness Mr.

James, and received in evidence.)

BY MR. WITT:

2 highly encouraging. Well, in letter C, we don't Mention highly

IS

l!l

20

21

*>■>

22

2 t

2"»

q Now, call your attention to the principal dis

tinction — difference between this letter and letter C.

A In this letter we really let them have it. We

say, "Your field of specialization is a crowded one and we

will have limited vacancies; however, we would be happy to

process an application for you and will give it serious

consideration if vacancies do occur."

q All right. Can you identify the fields of

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

ItIf

specialization that are crowded?

A rlelds like social studies, English, health and

physical education, business education.

Q Mow, would this be true for black and white

applicants?

A Yes.

Q There's no distinction here?

A Mo distinction.

Q Now, I hand you a form letter labeled "E. * is thin

a form letter that you use in your process?

A Yes, this is a form letter that we use in our

process.

Q Would you make this Exhibit No. 59 to your

testimony, please?

(Thereupon, the document referred

to above was marked Exhibit No.

59 for identification. Witness Mr.

James, and received in evidence.)

BY MR. WITT:

Q Now, explain, please, Mr. James, the message of

this letter.

A Well, essence of this letter reads thusly, however

well, I will start at the — pardon me — "Vacancies in our

system are usually rather limited and we cannot be too

encouraging to you about a position; however, places do come

open during the lste summer end if you desire to complete an

Jaws - Direct 462

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

Janes - Direct 663

application, we shall be glad to prooess it for our considera

tion. Please accept our best wishes to you as you go forward

to beginning your career."

Q Mow, Mr. Janes, what's the next step in the

recruitnent prooess after these letters are nailed back?

A Mall, the next step is to acknowledge our apprecia

tion to the placement director of the personal contacts at

the college or university that we have visited. We will write

then a letter acknowledging our appreciation for providing us

with a good schedule in making available to us the use of

their facilities for recruiting.

Q In this recruiting process, do you — do you

compete with recruiters from other public schools?

A Definitely.

Q Are these recruiters from one particular area or

otherwise?

A No# they come from all over, as far away as

California, eastern part of the United States, New York,

Connecticut, as far south as Miami, Dade County — highly

competitive out there.

U All right. When do you start receiving actual

applications, generally?

A Usually about two to three weeks after we have

visited a campus. WO ask the applicant to wait until he has

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

664

begun his student teaching if he has not already done so — if

he or she has not already done so. And, this gives us an

opportunity to get some feedback, a little more valid informa

tion frost the standpoint of reference from the supervising and

critic teacher. So sometimes this slows the process.

But, normally if they have met all requirements

including student teaching, we get them back in about two

weeks.

Q

A

Q

A

Is student teaching a requirement for consideration?

Yes, it is.

Mould you explain why this is important?

Well, it is important because of the fact that

we have, in trying to upgrade the professional staff of the

Chattanooga public schools, we are attempting to employ those

persons with professional teachers' certification only; and

in order to do so, they must or should have followed a teacher

education curricula and student teaching is a basic require

ment for such, and we prefer to employ persons who have

actually classroom experience as student teachers, because

we feel that those persons would have made the mistakes as

student teachers prior to employment rather than come in and

not have had any actual teaching experience and make it on the

job.

q Does this student teaching, is it limited to the

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

10

11

12

]:$

14

1.1

1(i

17

15

1 ! )

20

21

2.'t

21

last year in college or last semester or when?

A It's usually limited to the last senior year, the

last year in oollege.

Q Do you seek, the evaluation of the person that

supervised the student teaching of each applicant?

A Yes, yes, yes. On the application, we ask them

to give the name of the critic teacher and usually they will

list the supervising teacher, that is, the college supervising

teacher. The critic teacher is the regular classroom teacher

that they are working with.

Q All right. Once you have received these applica

tions , do you take any steps to evaluate and verify the

information?

A Well, not until we have — not until we have

processed and by that we mean that we would have sent references

materials to all persons listed for references including the

critic teacher. Occasionally they will have this information

in their pi ■ resinnt file in the placement office at the various

colleges and universities and we can request it from that

source.

Q Do you have copies of the material that you use

to — for evaluation of these people that are represented?

Do you have that with you?

A No, I don't. I don't have that. I think you

J i m s - Direct *65

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

1

•I

• >

• »

1

;>

(i

7

S

!t

ID

11

12

l:f

14

ir.

ID

17

18

1!)

20

21

•>■>

2'f

21

2*>

▼

eight h m those.

0 Mr. Janas, I hand you a form.

A Yes.

Q That on« is pink, one is green and one is blue and

one is yellow. You have all four?

A I have pink, blue, and green. I don't have a

yellow.

Q Mould you identify these, please?

A Yes, these are the fores — reference fores that

m nail.

Ju m s - Direct 666

Q All right. Mould you make these together Exhibit -

THE COURT: (Interposing) Sixty.

(Thereupon, the documents referred

to above were marked Exhibit No.

60 for identification, Witness Mr.

James, and received in evidence.)

BY MR. WITT:

Q All right. Mr. James?

A Yes.

Q First one, I believe, is pink?

A Right.

Q What is its use?

A The pink one is for teaching experience primarily.

Q To whom is it sent?

A Sent to the previous employer.

Q All right.

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

1

•>

:t

4

5

<;

7

8

!>

10

I I

12

14

14

i:>

1<i

17

18

1!)

20

21

■ >•>

24

24

2f>

667

A And, the next copy, I b s l i m , is blue or is that

grssn?

0 Grssn. What is its use?

A Its oss is primarily for tbs student teaching

sxpsrisnos reference, and I would think that it would be sent

to the critic teacher or the college supervisor teacher.

q All right. Then, the next copy is the blue copy?

A Mall, this would be a non-teaching experience,

somebody that they would list as a reference, maybe a neighbor

or minister or a friend or roaestate or somebody like this.

q All right. And then what use is made of the

yellow form?

A The same, really, a friend. They list godparent

or somebody like this.

Q Are there any other means of following up on this

information?

A Well, I mentioned on an occasion they won't list

references. They will say that the reference is in the

office of placement at the institution that they would have

graduated from. We find that this is becoming more and more

popular with the college graduate. They will complete this

information while in college and it remains there over a

period of years just as a transcript, you see. You just write

bade to the placement officer, ask that they send the placemec

R I C H A R D S M I T H O E M C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E O S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

1

»>

•»

• >

I

f>

i;

7

s

!l

10

11

12

|:i

14

1"»

1<i

17

18

1!)

*_'(]

21

* »* :

21

*>■

668

file for a partitular applicant.

And, even if the pzofesaor is no longer there, the

person that, of coarse, would give then a recosssendation, this

inf creation will remain with the institution. So, ns get this

information fran placeswnt quite often now.

q Do you recall approximately how many students

that you interviewed in the last — since, say, September,

approximately?

A Let me see, I would think that we have visited

approximately 35 colleges and universities and we have talked

with, on the average, 10 to 12 students. So, we can assess

it from that.

q Do you — are you aware of how many applications

you have actually received as of this time as a result of your

efforts?

A I am not — but I really don't know. I knew how

many we have on file.

q How many?

A At this time?

q How many applications do you have on file?

A Well, as of April 7th, we had about 800 applicants

applications on file.

q How would you age these applications?

A Well, none of these were more than two years old.

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

:iois

Jammu - Direct 669

q I I M . Ordinarily, about hem many teacher® are

employed each year, new teachers?

X For the opening of school last year, we employed

140 teachers. During the school year, I think we would have

employed approximately 200 or a little more, and these posit

of course, were created by persons having taken leaves of

absence or resigned.

q Is the 200 figure, does it include the earlier

figure or is that —

A (Interposing) That is included in the 140 that

we opened school with back in August.

q so, as of now, you have approximately 200 teachers

that were not in the system last year?

A Yea, maybe a little more than that; but I know

we opened school with 140.

q Approximately how many teachers are there in the

city school system?

A Thirteen hundred and something, I don't recall

the exact number.

q Hr. James, believe I forgot to ask you about

your earlier educational experience. Where did you attend

college?

A I graduated from Clark College at Atlanta, Georgia

I received my undergraduate bachelor's degree; my master's

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T K R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

670

from Indiana Univarsity. Blockington.

q And what waa your master's in?

A Health and physical education.

0 When were you first employed by the Chattanooga

school system?

A 1951.

q And what was your assignment?

A I was director of athletics and head football coach

at Howard High School for some 14 years. And, for the last

two years prior to my coming back to city schools, I was

employment adviser, public relations aide to the Chattanooga

Manufacturing Association and last April 1 came back to

Qiattanooga public schools as Director of Professional

Personnel.

q Mr. James, in your activities as athletic director

at Howard High School, are you generally aware of the athletic

situation in the high schools in the City of Chattanooga?

A Tes, to some extent I am.

q d o you recall the approximate time that the

athletic leagues in the city — in the city school system

were desegregated?

A Yes, it was 1966-67 that the HIL was desegregated.

That was the original, local athletic league, comprising, of

course, city and county schools, Hamilton County interscholastic

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

671

league and the predominately black schools were taken in.

However, 1 understand — well, I know that the HIL

presently is still in existence. However, the county schools

are no longer members of the HIL. They are now referred to

as the HCL, Hamilton County League, and they are no longer in

existence or a part of HIL.

So, the city schools are primarily HIL, now, I

think. Five, along with, I think, Baylor is a member of HIL.

MR. WITT: I have no further questions of this

witness.

CROSS EXAMINATION

BY MR. WILLIAMS:

Q Mr. James, has there always been a director or

coordinator of personnel in the Chattanooga school systems?

A No, I have not. I became Director of Professional

Personnel last April.

Q Which is it, director or coordinator?

A Director. It was coordinator when I was first

employed, but they changed the title about a month afterwards.

Q All right.

A All coordinators have now become directors.

Q You were the first Director of Personnel, is that

right? There was no one before you?

A To my knowledge, there was no one.

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E O S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

II)

11

12

111

11

ir»

Hi

17

IS

Q All right. You do not have complete charge of

personnel in the Chattanooga school system, do you?

A Professional personnel, yes.

U What is the function of the Assistant Superintendent

for Staff and Personnel?

A It is ay understanding that he is directly in

charge of the entire division of staff personnel.

Q Oh, I see. So, then, you are not in charge of

personnel. You are simply a recruiter?

A Hot necessarily, I don't think.

Q Hell, what do you do in addition to recruiting?

A I recommend persons for employment. I —

Q (Interposing) Is that all?

A Ho, I communicate with principals on their employ

ment needs.

Q But, you do not actually have the total and final

responsibility?

James - Cross 672

H>

20

21

*j:l

21

A Ho, no.

Q For the personnel department?

A No, I do not. You see, there are two divisions

in two departments in the division of staff personnel —

classified and professional.

Q You don't have the full and total responsibility

for professional personnel either, do you? In other words.

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

673

you don't date rains what teachers shall be assigned to what

schools, do you, and how many teachers shall be assigned to

the schools?

A No.

Q And, you say there was no one before you were

employed doing exactly what you are doing?

A To ay knowledge, I don't know what was happening

before X went there.

Q Is it your primary function to try to recruit

black teachers?

A No, I recruit black and white.

Q You try to recruit all teachers, all right.

A (Witness moves head up and down.)

Q in the 13 months during which you have been

Director of — coordinator or director of personnel, have

any measures bean taken to integrate the faculty employed

prior to 1967?

MR. WITT: X believe that's beyond the subject of

the direct examination.

THE COURT: Well, he may ask his question. You,

of course, would not be permitted to cross examine about matters

that were not covered in direct, but he made direct examina

tion to those matters.

THE WITNESS: Would you repeat that question.

R I C H A R D S M I T H . O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

674

Mr. Witt?

BY HK. WILLIAMS:

Q In th« 13 Months during which you havs hnsn

coordinator or diroctor of profsssional personnel, have any

Measures been taken to integrate the faculty employed prior to

1967?

A Yes.

Q What Measures?

A Well, we have attenpted to discuss with the

principals and let then know that they, of course, needed to

adhere to the Supreme Court's decision of desegregation

that they needed to cross racial lines a little s o n than what

has been done.

Q Any crossing of racial lines, though, in reference

to faculty employed prior to 1967 has been on a voluntary

basis?

A I don't know what happened prior to 1967. See,

Z was not on the scene. I was not in this position.

Q I don't think you understand the question.

A Maybe I didn't.

Q Any crossing of racial lines since 1967 in

reference to teachers who were already employed prior to 1967

has been on a purely voluntary basis, hasn't it?

A I don't follow your question.

R I C H A R D S M I T H . O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

1

2

:{

4

. i

(I

7

8

!>

10

1 1

1 i!

14

14

ir>

Hi

17

IK

1!>

‘JO

‘Jl

*»•>

j : i

•J1

• jr>

Jamas - Cross 675

Q All right. Do you have any understanding of

the Meaning of the word "crossovers"?

A Definitely.

0 What does that mean?

A that M a n s that you cross over with teachers,

racial crossover.

0 Means the employment of a teacher in a formerly

white — a white teacher in a formerly black school or a

black teacher in a formerly white school?

A Right.

Q Have any assignments of crossover teachers, to

your knowledge, been made in the 13 months that you have been

coordinator or director of personnel of — in reference to

teachers who were employed prior to 1967 on any basis other

than a voluntary basis?

A I don't recall.

Q So far as you know, there have been none?

A I don't recall.

Q If there have been, you don't recall any, is

that it?

A I don't recall.

Q You don't recall what, now, what does that mean?

A I don't recall whether or not there have been

any crossovers.

R I C H A R D S M I T H O E T I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

James - Cross 676

Q So then, so far as you know, you —

A (Interposing) I said as far as I know.

Q there have been none?

A As far as I know. I don’t recall whether there

has been any crossovers.

Q All right. Hell, is it a part of your function

to try to secure integrated personnel and secure the assignments

of integrated personnel?

A It is part of ay function to recruit black and

white teachers. I recruit on predominately black canpuses,

I recruit on predominately white campuses.

Q All right. Do you recruit mostly at formerly

black schools?

A Ho, I recruit at predominately white campuses.

Q But, in any event, Mr. James, so far as you know,

there have been no unvoluntary assignments of teachers prior

to 1967?

A I don't recall, Mr. Williams.

Q All right, sir. Do you have any different

approach when you recruit on black campuses than when you

recruit on white campuses?

A Mo, I don't.

0 All right.

A I am looking for good teachers.

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

1

•>

:s

4

">

(i

7

8

!»

10

11

12

18

14

ir>

Hi

17

18

1!)

20

21

22

21

2 . «

Jamas - Cross 677

0 You don't recognize any difference in the recruit-

ment of black teachers than in the recruitment of white

teachers, any difference in approach?

A Mo. I recognize that the black teachers are n o n

difficult to coerce.

Q Do you coerce teachers?

A Well, it becomes a competitive thing, you know,

when you are dealing with blacks from the standpoint of

salaries and what not, and we don't have as many.

Q Why do you say that black teachers are more

difficult?

A Everybody is looking for them and the better

student, black, is going into industry. The free land country

of the east and the midwest, they are grabbing them.

Q The better white teachers are also going into

industry and business, better white college students doing

that also?

A Well, not those that have followed the teacher

education curriculum. I wouldn't think so.

Q Well, the black students who have followed the

teacher education curriculum are not going into other fields,

are they, any more than white?

A Mo, but the top black students not following the

teacher education curriculum, they are going into other

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

J a m s - Cross

professions.

g pfii you have anything to do with recruitment

prior to the desegregation of scdxools?

A Ho, I did not.

q Well, do you know hoe it c a m about that the

school syston > u Able to eoploy bl.de toschws before th.

schools were desegregated?

A Ho, I don't.

q Didn't have any problem employing black teachers

for black schools, did they, did they. Hr. Jams?

A I don't think — I don't think so, I wouldn't

67S

think.

Q a s a natter of fact, Mr. Jams, isn't it true that

traditionally it has been easier to secure staff personnel

when the schools were segregated for black schools than for

white schools because of the wider choice of opportunities

offered the white college graduates, isn't that a fact?

^ you repeat that statement?

q Traditionally, wasn't it much easier to recruit

faculty for black schools under the segregated system than

for white schools because of the wider choices of occupational

opportunities offered to white college graduates?

A Well, I agree to some extent, yes.

O Yes. And, there is still considerable limitation

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T H t P O H I L K

James - Cross 679

an the choices of occupations applicable to black college

graduates as compared to whites, isn't there?

A That's difficult for me to answer, Mr. Williams.

I have been on both sides of the fence with business and

industry and education. I know what's happened with industry.

q Well, when you say industry, what are you talking

about? You talking about the manufacturing industry?

A Yes.

q Is it your statement that the choices of

opportunity are so wide in manufacturing industry as to limit

the number of blade graduates who are available for teaching

capacity?

A Mot necessarily.

q All right, sir. As a matter of fact, you have

no statistical data on that, have you, Mr. James?

A I did when I was with the manufacturing associa

tion.

q Bare you collected any statistical data at all

with regard to limitation on the number of black college

graduates who are available for the teaching profession?

A Yes, I have.

q Mlie re is that data?

A Those that would meet the types of requirements

that we are looking for.

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F M C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

-

!)

10

11

11*.

M

1 1

ir.

Hi

17

1H

10

1*0

•21

l*:t

21

2 ' »

jamm* - Cross 680

q Have tbs requirements been chanqtd since school

desegregation case about, Mr. Janes?

A Professional teacher requirements, I would think.

are the

0

A

Q

Then, they have not been changed?

As far as the State of Tennessee.

All right. Well, have they been changed insofar

as the Chattanooga school aysten is concerned?

A I would think so.

q Why?

A. Because of an attempt to upgrade.

q Why did the attenpt to upgrade have to ocne about

at the tine the schools were going to be desegregated?

A I don't know. Schools have been desegregated

in Chattanooga for two or three years supposedly, anyway.

q Well, is Howard and Riverside, are those schools

desegregated, in your opinion?

A Wo, no.

q Then, all the schools have not been desegregated,

have they?

A Mo, that's obvious.

q Then, I repeat, why do we all of a sudden have to

begin worrying about so much upgrading of teacher qualifica

tions at a tine when school desegregation is coning about?

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O W T f c R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

Ja m s - Cross 681

A The purpose is quality education.

q Thsn, is it your position that quality sduoation

is mads availabls only whan black children have to go to

school with whits children?

A No, school's for black students as wall as whits

children.

q i ass. Do you have any knowledge as to idiy

quality education, then, wasn't nads available to black

children when they hadn't desegregated the schools?

A Repeat that, please.

0 You have any idea, then, as to »diy this quality

education wasn't made available to black children when we

had segregated black schools?

A I don't know. I am aware of the fact that it was

not, but I don't know why.

q All right. Is it your idea that quality educa

tion has anything to do with the employment of black teachers?

A I think it's important that we have good teachers,

whether they are black or white. We don't want academicians.

We want good teachers.

q Mr. James, of the 800 teachers that you presently

have, how many of them are black, and the teacher applications,

I am sorry, that you presently have, how many of those are

►

black and how many are trfiite?

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

HI

1 I

12

i.:

i t

r>

Mi

17

1H

l!l

20

A Z don't think w tuns — I don't have a breakdown.

Let m see if we do. If I have, I night havn — Z don't

believe Z do, though. Z think about 38 percent of our total

on, you nean applications?

0 Yes.

A That we have? Z would roughly say about 30, 30 or

35 percent of then.

Q Thirty-five percent?

A Or less than 30 percent, about 30 percent or less.

q About 30 percent? Well, would you say it's close

to 30 percent?

A Yes.

Q Of your applications for black teacher s?

A Right.

Q All right. Nov, how many of those black teacher

applications are ones which were submitted in response to

letter type A?

A Hr. williams, that would be rather difficult to

answer, because —

James - Cross 682

q (Interposing) Why were —

A (continuing) — sane of those — son* of those

applications were already on file when I began my recruiting

efforts in October of '70.

q Approximately how many of those of the 800 were

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

Janes - Cross 683

already an file?

A Z wwil^ say s o n than half of thee.

Q All right.

A See, because the persons that I have recruited,

we have applications for, are just now coning in.

0 All right. Thsn, you had — you had about 400

applications on file when you took over?

A Had an abundant nunber.

q All right, were any of those — were any of those

on file of people who professionally were highly acceptable?

A No, and —

q (Interposing) Were any of those on file of

people who were acceptable?

acceptable?

A Sene were acceptable, yes.

q What percentage of those on file

A well, this is difficult for me to

q well, do you keep records on this, Mr. Janes?

A Yes, I do.

q you do operate your office in a professional

fashion, do you not?

A Yes.

q Do you not consider it important to keep record

of those applications that you consider acceptable and those

you consider noneocaptabla?

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D 6 T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

Janas - Cross 684

A Taa, X do.

Q All right. Can y m furnish --

A (interposing) But, I want to say this to you,

that a vary — 11 psrcsntag® of this 800 applicants wars black

if this is what you ara specifically talking about, a vary,

vary snail percentage.

q You said approximately 30 percent, didn't you?

A Yeah.

q Yes.

A But, about 10 percent of then are persons that

1 recruited — that were recruited under the efforts of

which I coordinated the recruiting efforts.

q Mall, are you aware of the — of the research

of the release that was recently acconplished by Mr. Ernest

Griggs, the Commissioner for the State of Tennessee Employment

Security from research done by Dr. Eberling of Vanderbilt

who is handling research for the State in this area and is

finding that there was a large nuaber of teachers on the

unemployed list and that teachers headed the list of the

unemployed, you ware not aware of that?

A No.

Q YOU do not keep abreast of the literature in this

area, then, right ?

A As I said, we are only concerned about the

R I C H A R D S M I T H . O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

Janas - Cross 6SS

professional certificated person, and you say — when you

M y teacher, you know you oould be talking about a Sunday

School teacher or anybody. We are concerned about professions.,

certificated teachers.

q It is ny understanding that this release, this

publication, related to public school teachers.

^ Pour-year degree? Professional certificated

people?

q Yes. Have you made any survey — can you tell the

Court, now, how sany of the 800 applications on file are

teachers who hold degrees, who hold college degrees, and who

are certificated by the State for teaching in their areas?

A

Q

A

Q

A

ninety-nine percent of then.

Ninety-nine percent of then?

Either professional or tenporary certification.

So — so, and how many?

Ito won't even process an application unless they

4-year degree people.

q Then, many of those teachers — teacher applica

tions on file relate to black teachers who live right here

in the City of Chattanooga, don't they, who are unemployed?

A Wot with professional certification.

q Sir?

A Not with professional certification.

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

file of black teachers?

A With professional certification.

q With professional certification?

A Right.

q who live in the City of Chattanooga?

A To ay knowledge.

q Well, do you know or do you not know?

A That have consulted with ne, sir?

q Then, you concede the possibility that there nay

be acne of those applications?

A There could be. 1 said that have consulted with

ne •

Q h o w frequently do you review your application

file?

A Well, 95 percent of the interviewing I do, so

if they have been interviewed, they have been interviewed by

o You M Y you have no black teacher applications on

Q

A

Q

Do you actually employ the teachers or does Mister

(Interposing) I recommend for employment.

But, it's actually Mr. Heustess who employs then.

is that correct?

A Well, the Board employs.

q Well, what does Mr. James U. Heustess do?

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

687

A He is the Assistant Superintendent.

0 Charge of personnel? Isn't he the one who actually

recommends to the Board?

A I recommend to him.

Q And then he recommends to the Board?

A To the Board.

Q And he can countermand your recommendation?

A Yes.

Q Yes. And, he is a white man. isn't he?

A Yes, very much so.

Q You are a black man?

A Right.

Q Yes. You have indicated that in the current

year you employed approximately 200 new teachers, 140 in

September and 60 as a result of attrition in the course of the

year?

A Uh-huh.

Q Based on your of course, you weren't here in

prior years; but based on your examination of the records,

is that about par for the course?

A I would think so.

Q So, that the Chattanooga school system can expect

to employ approximately 200 new teachers each year?

A Maybe a few more this year, I would think, because

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

Jammu - Cross 688

or 200 is a little nore than the average?

A No, a few more this coning school year, 1 would

think, because of the number.

q Difference between 200 and 225?

A Sonsthing like that.

Q All right, sir. So that — can you furnish the

Court a breakdown of the number of the applications on file

by race which are acceptable in terns of the Chattanooga schoo..

system standards for teachers?

A You speaking of those we have on file at this time''

q Yes. You have already said you have 800 on file.

You said that 99 percent of those are acceptable insofar as thn

State is concerned. They are certificated, they have 4-year

college degrees, and so —

A (Interposing) 1 would think that in certain areas

we have approximately — well, overall, we would have about 30J

of those 800.

g All right. About 300 of those 800 are acceptable

insofar as the Chattanooga — the City of Chattanooga school

system standards?

A Right.

Q Por quality education —

A (Interposing) Right-

Q (Interposing) So that 200 was a few sore than 200

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

Jamas - Cross 689

Q (Continuing) — are concerned?

A Right.

Q Mow, of that 300, approximately what percentage

would you say would be black teachers?

A About 75.

Q Then, you do — you apply a different standard

with regard to black teachers?

A MO.

Q Than you do white teachers?

A No.

a Can you account for the disparity in reference?

A Me have —

a (Interposing) Black and white teachers according

to the City of Chattanooga standards as compared to the State

standards?

A

teacher.

We have just not been able to recruit the black

Q All right. What, are the standards over and above

the State standards that you are applying in this subjective

quality education thing that you are talking about?

A The standards are the sane, but, Mr. Millions, we

go to a college campus to recruit a student. And, we encounter

recruiters, a number of the metropolitan communities that are

paying a beginning salary of nine-one.

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

690

Q Mister —

make this comparison if you would, please, and try to get my

point over. May I?

A (Interposing) And eight-five. Well, I just vent to

q I am sure the Court would permit you to do so, but

right now we are talking about teacher applications.

A Well —

0 (Interposing) And —

A (Interposing) If you would permit me to do this,

then maybe I can get it over.

Q All right.

A And, in attempting to talk with the students and

they see that we are at a beginning salary of 6,600 and

primarily the black student, as I was, I guess most blacks

were economically deprived — and one thing that they are

going to look at is salary — money. They won't even cone in

and talk to me. They are going in and talk with the recruiter^

that's offering the most money, not taking under consideration

the cost of living in that community as compared to what it

will cost to live in Chattanooga.

And this is why I have been trying to get over

to you that it is difficult to recruit the black teacher.

Q Well, you have said that.

A In comparison, I will give you another example if

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R t P O R T L H

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

J

2

•>

•»

i

r.

ii

7

H

!l

11*

11

12

l . i

1 I

r>

i<;

it

IS

1!)

•JO

J1

J'l

21

J'»

you will permit ms, please. Tennessee State, we have visited

Tennessee State University on two occasions this year. We

talked with three students the first time. The second time

we talked with sir.

At Tennessee Tech, we had to send two recruiters.

In Middle Tennessee State, we had to sand two recruiters. At

the University of Tennessee, we had to send two recruiters.

At Fisk, we talked with some students. One was a boy that I

had formerly coached that was in health and phys ed, and we

don't need any health and phys ed majors. And the other was

a foreigner majoring in chemistry — speaking an unknown tongui

I mean, this is the comparison I have been trying

to make all day long with the types of students that — we

go to Austin-Peay, and I talk with 15 students. This is why

it's so difficult for us to recruit the black student. I go

to Atlanta University, they have got three colleges, and X hav

a daughter in one. And, I spend the entire afternoon talking

with her because nobody else will come over for the interview.

Now, this is one of the reasons why we have

difficulty recruiting the black student. X don’t know what

the problems are and they know far «head in advance that we

are to cone.

Q All right. Mr. Janes, the question X asked, now,

to relate to recruiting, please listen to the question.

Janas - Cross 691

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

All right, sir.

You have stated that you have 800 applications

Crocs 692

on file and you believe that approximately 240 of those applies

tiona are 30 percent black?

A Yes.

i

12

i::

11

is

if

JO

21

22

21

0 How, then, I an asking about the standards that

you are applying. You have said that only approximately 75 of

those 240 applications are acceptable according to the City of

Chattanooga standards?

A Right.

Q Although you concede that they are all certified

by the State?

A Either temporary professional, see, 70 of the 75

could be temporary certification, and we are requiring

professional certification for the whites, so ve are going to

require the same for the blacks.

Q Are we talking — are we talking about facts or

are we talking about guesses?

A We are talking about facts.

Q Wliat are the qualifications that the City of

Chattanooga applies that are not applied by the State?

A Mr. Williams, 1 just don't know what to say to

try to get this point over to you.

Q Well, is the point that some of these 240 teachers

R I C H A R D S M I T H O F F I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

II)

11

12

l:l

1l

i r,

in

IT

18

1M

20

21

*>•>

2'!

21

have professional certificates and s

A

Q

A

Q

have?

A

Q

A

James - Cross 693

do not?

Tee.

Is that what you are saying?

A great percentage of them don't have, that's —

(Interposing) What kind of certificates do they

They have temporary.

All right. Explain what a temporary —

(Interposing) A temporary certificate is — a

temporary is a certificate granted to any college graduate

who has completed four years of college that will have an

equivalent of six hours of accumulated work in education and

it can be in psychology or anything. In other vords, you can

take pro-mod and get a temporary certificate with no preparation

for teacher education or no preparation for teaching and this

certificate will permit you to teach two years.

Q All right. And, will you not have been required

to have practice teaching in order to have —

A (Interposing) No, sir.

Q A temporary certificate? No practice teaching?

A None whatsoever. „

Q All right. Now, have you made — can you tell the

Court how many of those 300 teachers have temporary certificates?

A It's difficult for me to say, but I would think —

R I C H A R D S M I T H O M - I C I A L C O U R T R E P O R T E R

U N I T E D S T A T E S D I S T R I C T C O U R T

Janos - Cross t »4

A Hall, I don't really know. I tall you what, all

of this school year, tha oonmmnication that wa nailed to the

placement directors back in August requesting that wa visit

their campus for purposes of recruiting, we asked then told

then that we only wanted to talk with students who were in

th*» teacher education program, and who Diet, of course, the

Tennessee professional teachers certification requirements.

And, of course, we listed them.

q Mr. James, can you make a review of your teacher

quick review of the teacher application files and furnish to

this Court a listing of the actual number of black and white

teacher applications on file and the actual number of blade