McGhee v. Sipes Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1947

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McGhee v. Sipes Brief for Petitioners, 1947. 032e9590-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4d8d6001-4e15-4c87-b6c7-6007d925ee0e/mcghee-v-sipes-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

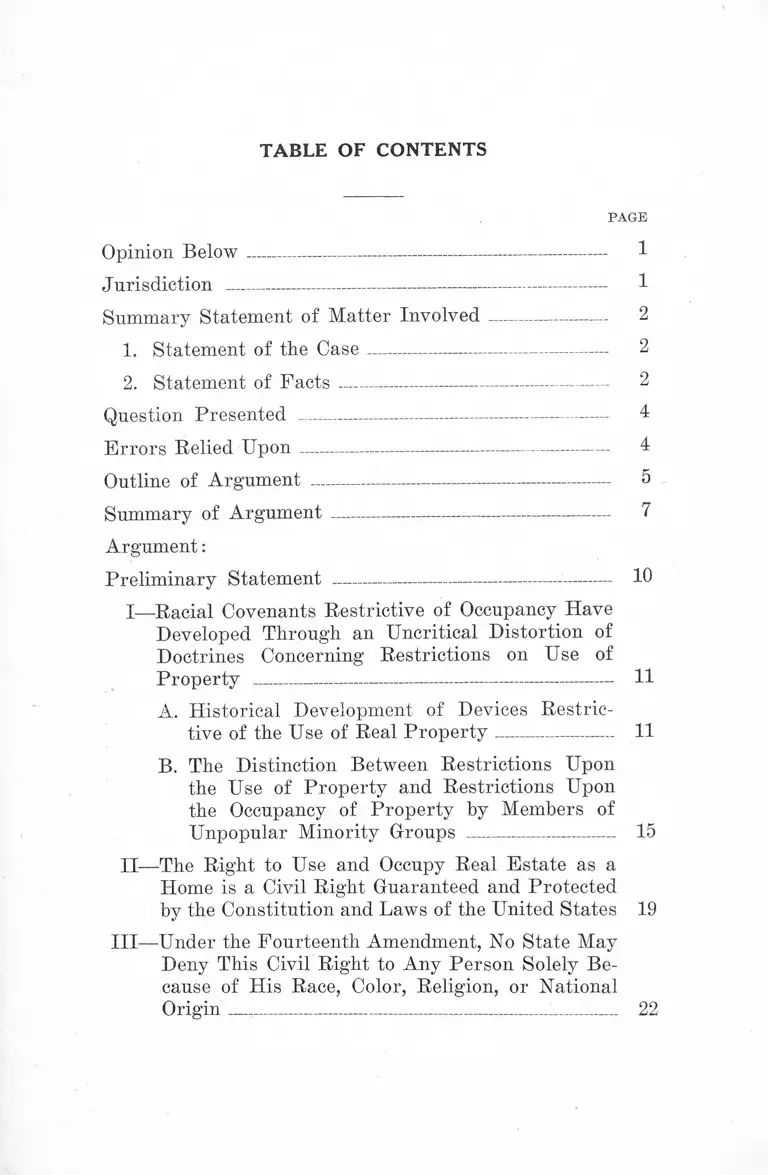

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Opinion Below ______________________________________ 1

Jurisdiction ------------ 1

Summary Statement of Matter Involved------------------ 2

1. Statement of the Case —--------------------- ----- ------- 2

2. Statement of F a cts ------------------ ----- ■------------------- 2

Question Presented ------- ----- ---------------------------- ------- 4

Errors Belied U p on ------- -------------------- ----- ---------------- 4

Outline of Argument ------------------------------------------------ 5

Summary of Argument --------------------------------------- --— 7

Argument:

Preliminary Statement --------------------------------------------- 10

I— Racial Covenants Restrictive of Occupancy Have

Developed Through an Uncritical Distortion of

Doctrines Concerning Restrictions on Use of

Property ______________________________________ 11

A . Historical Development of Devices Restric

tive of the Use of Real Property------------------- 11

B. The Distinction Between Restrictions Upon

the Use of Property and Restrictions Upon

the Occupancy of Property by Members of

Unpopular Minority Groups ________________ 15

II— The Right to Use and Occupy Real Estate as a

Home is a Civil Right Guaranteed and Protected

by the Constitution and Laws of the United States 19

III—Under the Fourteenth Amendment, No State May

Deny This Civil Right to Any Person Solely Be

cause of His Race, Color, Religion, or National

Origin

PAGE

2 2

11

A. It is Well Settled That Legislation Condition

ing the Eight to Use and Occupy Property

Solely Upon the Basis of Eace, Color, Eeligion,

or National Origin Violates the Fourteenth

Amendment__________________________ _______ 22

B. Civil Eights Are Guaranteed by the Fourteenth

Amendment Against Invasion by the Judiciary 27

IV—Judicial Enforcement of the Eacial Eestrictive

Covenant Here Involved is a Denial by the State

of Michigan of the Petitioners’ Eights Under the

Fourteenth Amendment_______________ _______ 32

A. The Decree of the State Court Was Based

Solely on the Eace of Petitioners___________ : 32

B. It is the Decree of the State Court Which De

nies Petitioners the Use and Occupancy of

their Home _____________________ ________ ___ 33

C. Neither the Existence of the Eestrictive

Agreement Nor the Fact That the State’s Ac

tion Was Taken in Eeference Thereto Alters

in Any Way the State’s Eesponsibility Under

the Fourteenth Amendment for Infringing a

Civil Eight _________________________________ 36

The Fact That Neither Petitioners Nor

Their Grantors Were Parties to the Cove

nant Further Emphasizes the State’s Ee-

sponsible and Predominant Eole in the Ac

tion Taken Against Them _________________ 40

D. Petitioners’ Eight to Eelief in This Case Is

Not Affected by the Decision in Corrigan v.

Buckley ___1________________________________ 42

V—While No State-Sanctioned Discrimination Can

Be Consistent With the Fourteenth Amendment,

the Nation-Wide Destruction of Human and

Economic Values Which Eesults From Eacial

Eesidential Segregation Makes This Form of

Discrimination Peculiarly Eepugnant __________ 47

I l l

PAGE

A. Judicial Enforcement of Restrictive Cove

nants Has Created a Uniform Pattern of Un

precedented Overcrowding and Congestion in

the Housing of Negroes and an Appalling

Deterioration of Their Dwelling Conditions.

The Extension and Aggravation of Slum Con

ditions Have in Turn Resulted in a Serious

Rise in Disease, Crime, Vice, Racial Tension

and Mob Violence --------------------------- ------------

1. The Immediate Effects of the Enforcement

of Covenants Against Negroes ----------------

2. The Results of Slum Conditions in Negro

Housing _________________________________

a. The Effect of Residential Segregation

on Health ---------- ------------------- -- -------

b. Cost of Residential Segregation to the

Community as a Whole ----------------------

c. Racial Residential Segregation Causes

Segregation in All Aspects of Life and

Increases Group Tensions and Mob

Violence_______________________ _____

B. There Are No Economic Justifications for Re

strictive Covenants Against Negroes. Real

Property Is Not Destroyed or Depreciated

Solely by Reason of Negro Occupancy and

Large Segments of the Negro Population Can

Afford to Live in Areas From Which They

Are Barred Solely by Such Covenants. The

Sole Reason for the Enforcement of Cove

nants Are Racial Prejudice and the Desire on

the Part of Certain Operators to Exploit

Financially the Artificial Barriers Created by

Covenants __________________________________

1. The Effect of Negro Occupancy Upon Real

Property ________________________________

2. The Ability of Negroes to Pay for Better

Housing _________________________________

63

66

71

72

77

IV

V I—Judicial Enforcement of This Restrictive Cove

nant Violates the Treaty Entered Into Between

the United States and Members of the United

Nations Under Which the Agreement Here

PAGE

Sought to Be Enforced Is V o id _________________ 84

Conclusion____________________________ 90

Appendix____________________________________________ 92

Table of Cases

American Federation of Labor v. Swing, 312 U. S.

321 _______________________________ _____________30,38

Austerberry v. Oldham, 29 Ch. D. 750 _______________ 14

Bacon v. Walker, 204 U. S. 311 ____________________ 17

Bakery Drivers Local v. Wohl, 315 U. S. 769 ________ 31

Bridges v. State of California, 314 U. S. 252______i___ 31

Brinkerhoff Faris Co. v. Hill, 281 U. S. 673__________ 28

Brown, Ellington & Shields v. Mississippi, 297 U. S.

278 __________________ 28

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60______ 10,17,18, 20, 21. 22,

23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 35

Cafeteria Employees Union, Local 302 v. Angelos, 320

U. S. 293__________ 31

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296______________ 29, 38

Carter v. Texas, 177 U. S. 442_______________________ 28

Crist v. Henshaw, 196 Okla. 168____________________ 17

City of Dallas v. Liberty Annex Corp., 295 S. W. 591 __ 35

City of Richmond v. Deans, 281 U. S. 704________17, 22, 25

City of Richmond v. Deans (C. C. A.—4th), 37 F. (2d)

712 ______________________________________________ 26

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3___________ ____________ 21

Clark v. Allen, 67 Sup. Ct. 1431 (Advance Sheets) __ 86

Corrigan v. Buckley, 271 U. S. 323 _______ __ 10, 43, 45, 46

Corrigan v. Buckley, 55 App. D. C. 30, 299 F. 899

(1924)

Drummond Wren, In Re, 4 D, L. R. (1945) 674

44

90

Erie v. Tompkins, 304 U. S. 64 — ------------------------------ 32

Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., 272 U. S. 365------------------- 17

Ex Parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339_____________________ 27

Fisher v. St. Louis, 194 TJ. S. 361-------------------------------- 17

Gandolfo v. Hartman, 49 Fed. 181----------------------------- 89

Geoffroy v. Riggs, 133 U. S. 258-,-.--------- -------------------- - 86

Gorieb v. Fox, 274 U. S. 603—— ------------------------------- - 17

Hadacheck v. Sabastian, 239 IT. S. 394--------------------- -— 17

Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U. S. 668----------------------- 17, 22, 26, 27

Hauenstein v. Lynham, 100 U. S. 483------------------------- 86

Holden v. Hardy, 169 TJ. S. 366------ ---------------------------- 24

Home Telegraph v. Los Angeles, 227 IT. S. 278________ 36

Hurd v. Hodge, No. 290 Nov. Term 1947- _________ 52

Hysler v. Florida, 315 U. S. 411____ — ___,_______a_____ 28

Kennett v. Chambers, 55 TJ. S. 38—---- -------- ---------------- 88

Laurel Hill Cemetery v. San Francisco, 216 TJ. S. 358 — 17

Lord Grey v. Saxon, 6 Ves. 106------------------------------ — 14

Los Angeles Investment Co. v. Gary, 181 Cal. 680, 186

P. 596 (1919)____ ___________ -_____________ ___ _ _ 16

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 IT. S. 501--- ---------------------------- 39

Martin v. Nutkin, 2 P. Wms. 266---------------------------------- 14

Mayer v. White, 65 U. S. 317________________________ 88

Mays v. Burgess, 147 F. (2d) 869 (Dist. of Columbia

1944) ....... ................. ...... -___- ______ — _______ 10

Milk Wagon Drivers Union of Chicago, Local 753 v.

Meadowmoor Dairies, Inc., 312 U. S. 287__________ 30

Moore v. Dempsey, 261 IT. S. 86______________ ___— 28

Norris v. Alabama, 294 TJ. S. 587_____________________ 28

Northwestern Laundry Co. v. .Des Moines, 239 U. S.

486 _____________________ 1_______________________ 17

Phillips v. Wearn, 226 N. C. 290 (1946)______________ 10

Pierce Oil Co. v. Hope, 248 IT. S. 498...—__________ — 17

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U. S. 45______ ___:____-_________ 28

Purvis v. Shuman, 273 111. 286, 112 N. E. 679 (1916)-. 13

Reinman v. Little Rock, 237 IT. S. 171_____________ _■___ 17

Republic Aviation Corp. v. N. L. R. B., 324 IT. S. 793__ 39

V

PAGE

VI

Spencers’s Case, 5 Coke 16___________________________ 13

St. Louis Poster Advertising Co. v. St. Louis, 249 U. S.

269 ______________________________________________ 17

Standard Oil Co. v. Marysville, 279 U. S. 582___ _______ 17

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303____________ 20

The Bello Corrunes, 19 U. S. 152..__-__________________ 89

The Schooner Peggy, 5 U. S. 103_____________________ 86

Thomas Cusack Co. v. Chicago, 242 IT. S. 526__________ 17

Tulk v. Moxhay, 2 Phil. 774, 41 Eng. Rep. 1143________ 14

Trustees of the Monroe Ave. Church of Christ, et al. v.

Perkins, No. 153, Oct. Term, 1947___ -____________ 10

Twining v. New Jersey, 211 IT. S. 78_________________ 28

IT. S. v. Belmont, 301 IT. S. 324_____________________ .... 86

ITrciola v. Hodge, No. 291, Nov. Term, 1947__________ 52

Ware v. Hylton, 3 Hall. 199__________________________ 86

Welch v. Swasey, 214 U. S. 91_________________________ 17

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356_____________________ 36

Zahn v. Board of Public Works, 274 U. S. 325__________ 17

Statutes Cited

Civil Rights Acts------------------------------------------------ 19, 20, 27

32 Hen. VIII, c. 34 (1540)___________________________ 13

51 Stat. 1031________________________________________ 85

8 H. S. C. 42_____________________________________ 19, 20, 44

28 U. S. C. 344 (b )______ 1___________________________ 1

United States Constitution:

Article IV, Section 2

V Amendment ---------- ------------------------------------------- 44

X III Amendment ____________________ ___________19, 44

X IV Amendment ---------------------2,4,19, 20, 21, 23, 27, 28,

29, 31, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 39, 44

PAGE

V l l

Treaties

PAGE

Potsdam Declaration ----- 88

United Nations Charter:

Article 2, paragraph 2------------,-------- -------------------- 84

Article 6, Section 2________________________________ 85

Article 55 _______________________ 1------------------------ 84

Article 56 ______ -________________________________ 84

Authorities Cited

Abrams, Charles, Discriminatory Restrictive Cove

nants—A Challenge to the American Bar, address

before Association of the Bar of the City of New

York, Feb. 1947_______ __________ .________________ 47

Acheson, Dean, Letter of F. E. P. C., F inal Report or

FEPC (1945) ____________________________________ 87

A nnals op the A merican A cademy of Political and

Social S cience, Yol. 243 (1946)__________________84,85

A rchitectural F orum, October, 1947___________________ 58

Beebler, Color Occupancy Raises Values, R eview oe

the Society of Residential A ppraisers (Sept.

1945) _____________ s____________________________ 75,78

Blackstone’s Commentaries ___—------ 19

Blandford, J. B., Jr.,

The Need for Low Cost Housing, Speech before An

nual Conference, National Urban League, Colum

bus, Ohio (Oct. 1, 1944)___________________ ....... 80

Testimony before Subcommittee on Housing and

Urban Redevelopment, Senate, 79th Congress,

H earings, Part 6 --------- 63

Britton, New Light on the Relation of Housing to

Health, 32 A merican Journal of Public H ealth

193 (1942) ____________________ ____ _______ ______ 59

V l l l

Britton & Altman, Illness and Accidents among Per

sons Living under Different Housing Conditions, 56

Public H ealth Reports 609 (1941)______ ._________ 59, 60

B uilding Reporter & Realty News, The Urban Negro,

Focus of the Rousing Crisis (Nov. 1945)_____li__ 75, 76

Bureau of Census

H ousing Supplement—

Bloch Statistics, Detroit, March, 1940...________ 57, 76

General Characteristics, Michigan, 16th Census,

1940 ____________________________________ :____ 51,54

Negroes in the U nited States, 1920-1932 (1935)___ 48

Population Reports

Sixteenth Census, 1940 ___________________________ 48

Current Population Reports, Detroit, April,

1947 _________________________________________ 48, 55

Special Census, Race, Sex, by Census T racts

August, 1945 ______________________________________ 49

January, 1946 1____________________________________ 49

Burgess, Residential Segregation in American Cities,

A nnals of A merican A cademy of Social and Po

litical Science (N ov. 1928)_________________________ 50

Cardozo, The Judge as A Legislator, T he Nature of

the Judicial Process__________________________ ._____ 32

Cayton, Housing for Negroes, Chicago Sun , Bee. 13,

*1943 ____ 52

Negro Housing in Chicago, Social A ction (April

15, 1940)_______________________...________ ______ 78

Chicago, Cook County, H ealth Survey: Report on

H ousing _____________ 59

Chicago Park District, T he P olice and M inority

Groups (1947)________ — ....______________ 67, 70

PAGE

IX

Corbin, 29 Y ale L. Journal, 771—Note---------------------- 32

Clark, Covenants and I nterest Running with Land

12,13,14

Cobb, Medical Care and the Plight of the Negro, Crisis,

July, 1947______________________ _________________ 69

Committee on Hygiene of Housing of American Public

Health Association, Basic Principles of Healthful

Housing _____________________________________ _—59, 63

Cooper, The Frustration of Being a Member of a Minor

ity Group, 29 Mental Hygiene 189 (1945)_________ 62

Congressional Globe, 39th Congress, 1st Session,

Part 1 ________________________I_________________ 19, 20

Cressey, T he Succession oe Cultural Groups in the

City oe Chicago (1930)___________________________ 76

Detroit F ree Press, March 20, 1945--------------------------- 80

3 E lliots Debates, 515___________________________________ 85

Farris & Dunham, Mental Disorders in Urban A reas :

An Ecological Study of Schizophrenia and Other

Psychoses (1939)__________________________________ 62

Federal Works Agency, Postwar Urban Development

(1944) ____________________________________________ 63

Flack, A doption oe the F ourteenth A mendment (1908) 19

Frazier, N egro Y outh at the Crossway (1940)________ 70

Gover, Negro Mortality II, The Birth Rale and Infant

and Maternal Mortality, 61 Public Health Reports

43 (1946)_____________________ _____________________ 61

Hadley, Medical Psychiatry; an Ecological Note, 7

Psychiatry 379 (1944)____________ |j_____________ 61

H ealth Data Book for the City oe Chicago ---------------- 59

Hyde & Chisholm, Relation of Mental Disorders to

Race and Nationality, 77 N. E. Journal oe M edicine

612 (1944)

PAGE

62

PAGE

Hyde & Kingley, Studies in Medical Sociology; The Re

lation of Mental Disorders to Population Density,

77 N. E. Journal of Medicine 571 (1944)___________

Johnson, Patterns of Negro Segregation (1943) __ .1_„

Kiser, Sea Island to City (1932) ____________________

Lemkin, Genocide as a Crime Under International Law,

41 A merican Journal of International Law 145

(1947) _________________________________________ 86,

McDiarmid, The Charter and the Promotion of Human

Welfare, 14 State Department Bulletin 210 (1946)

Making the Peace Treaties 1941-1947, Department of

State Publications 2774, European Series 2 4 ______

Miller, Covenants for Exclusion, Survey Graphic (Oct.

1947) ____________________________________________

Moran, Where Shall They Live, T he A merican City

(April 1942)_____________________________________

Mummy and Phillips, Negroes as Neighbors, Common

Sense, April 1944 __________________ _____________

Myrdal, A n A merican Dilemma (1944) ______________

National A ssociation of Real E state Boards, Press

Release No. 78, Nov. 15, 1944_____________________

National H ousing A gency

Housing Facts, 1940 ______________________________

McGraw, Wartime Employment, Migration and

Housing of Negroes in U. S. 1941-1944, Race Re

lations Service Documents Series A, No. 1,

1946 _________________________________ _______ 71,

National P ublic H ousing Conference, Race Relations

in Housing Policy (1946) __________________ _____

National Urban L eague, Economic and Cultural Prob

lems in Evanston, Illinois, as They Relate to the

Colored Population, Feb. 1945___ . ... , ......

61

67

76

87

87

87

68

78

74

69

73

66

80

66

69

X I

Newcomb & Kyle. The Housing Crisis in a Free Econ

omy, Law and Contemporary Problems (Winter,

1947) __________________________________ * ..—_ 77

Oakland Kenwood Property Owners Association of

Chicago, President’s Annual Report for 1944_____ 67

Park, Burgess & McKenzie, T he City (1925)-------------- 50

Paul, The Epidemeology of Rheumatic Fever and some

of Its Public Health Aspects, Metropolitan Life In

surance Co. (1943)________________________________ 60

People oe Detroit, Master Plan Reports, Detroit City

Planning Commission (1946)______________ 51, 66, 68, 69

President’s Conference on H ome B uilding and H ome

Ownership, Report of Committee on Negro Housing

(1932) ___________________________________________ 50

Robinson, Relation between Conditions of Dwellings

and Rentals by Race, Journal of Land and Public

U tility E conomics (Oct. 1946)__________________53,56

Rumney & Shuman, The Cost of Slums in Newark,

Newark Housing Authority, 1946_________________ 64

1 Sm ith ’s L eading Cases (8th Ed.) 150_______________ 13

Smillie, Preventive Medicine and Public H ealth

(1946) _________________________________________ 59,62

Stern, Long Range Effect of Colored Occupancy, Re

view of Society of Residential A ppraisers Jan.

1945 _________ 76

Stettinius, 13 State Department Bulletin, 928 (1945) 87

Stone, Equitable Rights and Liabilities of Strangers to

a Contract, 18 Col. L. Rev. 291 (1918)________ 12,40,41

Ibid, Part II, 19 Col. L. Rev. 177 (1919)___________ 41

The F ederation of Neighborhood A ssociations (Chi

cago), Restrictive Covenants (1944)______________ 67

T he Slum— Is Rehabilitation Possible? (Chicago Hous

ing Authority 1946)_____________________________ 52, 80

PAGE

Tiffany, Landlord and Tenant, I____________________ 13,14

Real Property (3rd ed.)___________________ '___ ___ 14

U nited Nations, Resolution of General Assembly, Dec.

11, 1946 ______________________________________________ 87

xii

PAGE

Urban H ousing, Federal Emergency Adm. of Public

Works ___________________________________________ 63

U nited States Childrens Bureau, Our Nations Chil

dren, No. 8 (August 1947)_______________________ 60

United States Department op Commerce

Survey of World War II Veterans and Dwelling

Unit Vacancy and Occupancy in the Detroit

Area, Oct. 31, 1946 _____________ ______________ 82

Survey of World War II Veterans and Dwelling

Unit Vacancy and Occupancy in the St. Louis

Area, Missouri, Nov. 26, 1946_______________ ____ 82

U nited States Department oe Labor

Survey of Negro World War II Veterans and Va

cancy and Occupancy of Dwelling Units Avail

able to Negroes in the Detroit Area, Michigan,

Jan. 1947 ____________________________________ 81, 82

Survey of Negro World War II Veterans and Va

cancy and Occupancy of Dwelling Units Avail

able to Negroes in St. Louis Area, Missouri and

Illinois, November-December, 1946____________ 82

Velie, Housing: Detroit’s Time Bomb, Collier’s Maga

zine, Nov. 23, 1946_______________________ ____ 55, 65, 78

X l l l

Walker, Urban Blight and Slums, 1938_____________ 63

Weaver, Chicago, A City of Covenants, Crisis Maga

zine, March, 1946____________________________ 70, 71, 83

Negro Labor, A National Problem (1946)________ 64, 79

PAGE

Planning for More Flexible Land Use, Journal of

Land and Public Utility E conomics, Feb., 1947 65

Race Restrictive Housing Covenants, Journal op

Land and P ublic Utility E conomics, Aug.,

1944 ________ 49,73,74

Wedum & Wedum, Rheumatic Fever in Cincinnati in

Relation to Rentals, Crowding, Density of Popula

tion, and Negroes, 34 A merican Journal op Public

H ealth 1065 (1945) _________________________________ 60

What Caused the Detroit Riot, NAACP Publication

(July, 1943) __ 71

1 W m . Saunders (1st Am. ed.) 240a__________________ 13

Winslow, H ousing por H ealth (The Milbank Founda

tion, 1941) _______________________________________59, 63

Wood, Introduction to H ousing (1939)____________ 51

Slums and Blighted A reas in U nited States (1935) 63

Woofter, N egro P roblems in C ities (1928) ________ __ 78

IN THE

(Hour! of % TUnxtvb

October Term, 1947

No. 87

Obsel M cGhee and M in n ie S. M cGhee, M s wife,

Petitioners,

v.

Benjamin J. Sipes, and A nna C. Sipes, James A. Coon and

A ddie A. Coon, et al.,

Respondents.

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of the State of Michi

gan appears in the Record (E. 60-69) and is reported at 316

Mich. 614.

Jurisdiction

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under section

237b of the Judicial Code (28 U. S. C. 344b).

The date of judgment of the Supreme Court of the State

of Michigan is January 7, 1947 (R. 70), and petitioners’ mo

tion for a rehearing was denied on March 3, 1947 (R. 80).

A Petition for Certiorari was duly presented to this Court

on May 10, 1947 and was granted by this Court on June 23,

1947 (R. 81).

2

Summary Statement of Matter Involved

1. Statement of the Case

In the Circuit Court of Wayne County, Michigan, in

Chancery, the respondents herein sought and obtained a de

cree requiring the petitioners to move from property which

they owned and which they were occupying as their home,

and thereafter restraining them from using or occupying

the premises, and further restraining petitioners from vio

lating a race restrictive covenant upon such land, set forth

more fully below (R. 52-53).

In their amended answer to the bill of complaint peti

tioners duly raised the defense that the enforcement by the

court of such restrictive covenant would contravene the

Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution

and that the restrictive covenant relied upon by the respon

dents was void as against public policy (R. 16-17). On ap

peal to the Supreme Court of the State of Michigan the

petitioners’ Reasons and Grounds of Appeal specifically as

signed as errors of the lower court the holding that the

enforcement of such restrictive covenant by a court of

equity was not violative of the Fourteenth Amendment of

the Constitution of the United States and that the race re

strictive covenant was not void as against public policy

(R. 5-6).

The Supreme Court of Michigan affirmed the decree

entered by the trial court and in its opinion considered

and adjudicated, in favor of the respondents, the issues

raised (R. 60-69).

2. Statement of Facts

Petitioners are citizens of the United States and are

Negroes (R. 48, 53). They own and occupy as a residence

3

Lot 52 in Seebaldt’s Subdivision of the City of Detroit,

Michigan, commonly known as 4626 Seebaldt Avenue (R. 7).

■Respondents are the owners of lots in the same subdivision

and an adjoining subdivision (E. 7). At various times dur

ing the year 1934 the predecessors in title of the petitioners

and respondents had executed and recorded an instrument

relating to their respective lots in such subdivisions, pro

viding in its essential parts as follows:

“ We, the undersigned, owners of the following

described property:

Lot No. 52 Seebaldt’s Sub. of Part of Joseph Tire-

man’s Est. % Sec. 51 & 52 10 000 A T and Fr ’l Sec.

3, T. 2S, E 11 E.

for the purpose of defining, recording, and carrying

out the general plan of developing the subdivision

which has been uniformly recognized and followed,

do hereby agree that the following restriction be im

posed on our property above described, to remain in

force until January 1, 1960—to run with the land,

and to be binding on our heirs, executors, and as

signs :

“ This property shall not be used or occupied by

any person or persons except those of the Caucasian

race.

“ It is further agreed that this restriction shall

not be effective unless at least eighty percent of the

property fronting on both sides of the street in the

block where our land is located is subjected to this

or a similar restriction” (R. 42).

Such restriction was sought to be imposed upon 53 lots

in the two subdivisions in which respondents reside (R. 34).

Petitioners purchased their property from persons who did

not sign the restrictive agreement (R. 13).

4

Question Presented

Does the enforcement by state courts of an agreement

restricting the disposition of land by prohibiting its use and

occupancy by members of unpopular minority groups, where

neither the willing seller nor the willing purchaser was a

party to the agreement imposing the restriction, violate the

Fourteenth Amendment and treaty obligations under the

United Nations Charter?

Errors Relied Upon

The Supreme Court of Michigan erred in holding:

1. That the due process clause of the 14th Amendment

afforded petitioners no rights other than notice, a

day in court and reasonable opportunity to appear

and defend, and was not violated by the issuance of

the injunction enforcing the race restrictive agree

ment (R. 65-66).

2. That court enforcement of the restriction in question

does not violate the equal protection clause of the

14th Amendment, because “ we have never applied

the constitutional prohibition to private relations and

private contracts ’ ’ and that on the contrary to refuse

to enforce the agreement would deny equal protection

to the plaintiffs below (R. 66).

3. That the human rights provisions of United Nations

Charter are “ merely indicative of a desirable social

trend and an objective devoutly to be desired by all

well-thinking peoples.” It is not “ a principle of law

that a treaty between sovereign nations is applicable

to the contractual rights between citizens of the

United States when a determination of these rights

is sought in State courts” (R. 67).

5

OUTLINE OF ARGUMENT

I. Racial covenants restrictive of occupancy have

developed through an uncritical distortion of

doctrines concerning restrictions on use of prop

erty.

A. Historical development of devices restrictive of use

of real property.

B. The distinction between restrictions upon the use

of property and restrictions upon the occupancy of

property by members of unpopular minority groups.

II. The right to use and occupy real estate as a home

is a civil right guaranteed and protected by the

Constitution and laws of the United States.

A. Originating in ancient common law, this civil right

is expressly protected by the Fourteenth Amend

ment and the Civil Rights Act.

B. This civil right includes the right to own, use and

occupy real estate as a home.

III. Under the Fourteenth Amendment no state may

deny this civil right to any person solely because

of his race, color, religion or national origin.

A. It is well settled that legislation conditioning the

right to use and occupy property solely upon the

basis of race, color, religion or national origin vio

lates the Fourteenth Amendment.

B. A civil right guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amend

ment against invasion by a legislature is also pro

tected against invasion by the judiciary.

6

IV. Judicial enforcement of the racial restrictive cove

nant here involved is a denial by the State of

Michigan of the petitioners’ civil rights.

A. The decree below was based solely upon race.

B. It is the decree of the state court which denies

petitioners the use and occupancy of their home.

C. Neither the existence of the restrictive agreement

nor the fact that the state’s action was taken in

reference thereto alters in any way the state’s re

sponsibility under the Fourteenth Amendment for

infringing a civil right.

The fact that neither petitioners nor their

grantors were parties to the covenant further

emphasizes the state’s responsible and predom

inant role in the action taken against them.

D. Petitioners’ right to relief in this case is not affected

by the decision in Corrigan v. Buckley.

V. While no state-sanctioned discrimination can be

consistent with the Fourteenth Amendment, the

nation-wide destruction of human and economic

values which results from racial residential segre

gation makes this form of discrimination pecu

liarly repugnant.

A. Judicial enforcement of restrictive covenants has

created a uniform pattern of unprecedented over

crowding and congestion in the housing of Negroes

and an appalling deterioration of their dwelling

conditions. This extension and aggravation of slum

conditions have in turn resulted in a serious rise in

disease, crime, vice, racial tension and mob violence.

7

B. There are no economic justifications for restrictive

covenants against Negroes. Real property is not

destroyed or depreciated solely by reason of Negro

occupancy and large segments of the Negro popu

lation can afford to live in areas from which they are

barred solely by such covenants. The sole reason

for the enforcement of covenants are racial prej

udice and the desire on the part of certain operators

to exploit financially the artificial barriers created

by covenants.

VI. Judicial enforcement of this restrictive covenant

violates the treaty entered into between the United

States and other members of the United Nations

under which the agreement here sought to be

enforced is void.

Summary of Argument

Eacial restrictive covenants of the type involved in this

case have developed through the uncritical distortion of

doctrines concerning restrictions on the use of property.

Equitable enforcement of covenants restricting the use of

land was an innovation introduced into the law of England

to accomplish socially desirable delimitations of the func

tions which might be carried on in particular areas. Such

restrictions affected all persons equally and in the same way.

During this century, however, equitably enforced restrictive

covenants have been used in America for the new and en

tirely unrelated purpose of preventing the ownership and

occupancy of homes by unpopular minority groups. The

discriminatory effect of these latter day covenants and the

absence of any resulting advantage to society prevent the

earlier use covenants from affording any analogy justify

ing the enforcement of racial covenants restricting occu

pancy.

8

Beyond their lack of historical or analogical justification

in the common law, the judicial enforcement of racial restric

tive covenants infringes the civil right to use and occupy

real property as a home without legally sanctioned racial

impediments. The right freely to acquire and occupy land,

early declared by Blackstone and other common law writers,

survives today under protection of the Constitution and laws

of the United States. After discussion in Congress, this

right was expressly protected in the Civil Bights Act against

all restrictions based on race. From the Civil Rights Cases

to Buchanan v. Warley, this Court has protected the right

of a willing buyer to acquire property from a walling seller

and to use it freely as his own, without state imposed im

pediment based upon race, as a fundamental civil right pro

tected by the Fourteenth Amendment.

While Buchanan v. Warley protected the right in ques

tion against infringement by statute and Harmon v. Tyler

protected it against infringement by a combination of pri

vate action and statutory sanction, the rationale of these

cases leaves no room for a different conclusion where ju

dicial action in the absence of statute has accomplished the

same result. In a growing body of analogous situations this

Court has protected fundamental civil rights against judicial

infringement.

The sole argument against applying a doctrine which

struck down racial zoning statutes to the case at bar is based

upon the fact that the court’s action here is founded upon

a private agreement. But the private agreement is not self

executing. The determination of the state to enforce the

agreement involves the subordination of a fundamental civil

right to considerations of public interest promoted by giving

covenantors the benefit of their bargain. The obligations

of the Fourteenth Amendment may not thus be diminished

9

or evaded. This Court has consistently so ruled in a variety

of cases involving conflicts between fundamental civil rights

on the one hand and various interests of property and pub

lic security on the other.

The significance of the private agreement is further

minimized, and the role of the state as the effective engineer

of discrimination is further emphasized by the fact that

neither the petitioner grantees in this case nor their grant

ors were signers of the restrictive agreement. A special

legal doctrine and an extraordinary application of state

force were necessary to make effective the racial discrimina

tion of which petitioners complain.

A vast amount of authoritative sociological data demon

strates that health, morals and safety are impaired on a

national scale as a consequence of the widespread racial

restrictive covenants. Property values are also impaired.

Evils affecting the segregated minorities inevitably injure

the community as a whole. Thus, although no state sanc

tioned discrimination can be consistent with the Fourteenth

Amendment, the nationwide destruction of human and eco

nomic values which results from racial residential segre

gation makes this form of discrimination peculiarly repug

nant.

The human rights provisions of the United Nations

Charter, as treaty provisions, are the supreme law of the

land and no citizen may lawfully enter into a contract in

subversion of their purposes. The restrictive agreement

here presented for enforcement falls within this proscrip

tion.

10

A R G U M E N T

Preliminary Statement

In 1917, after the decision of this Court in Buchanan v.

Warley, it could reasonably have been predicted that life in

these United States would not be disfigured by the zoning of

human beings. But seekers after legal means to accomplish

what the Court had proscribed were persistent in their ef

forts to bring the ghetto to America, and courts, misled by

the presumed license of Corrigan v. Buckley, have too often

assisted them in doing so.

The areas affected have become so large and so numer

ous, the groups restricted so diverse, that the restrictive

covenant today must be recognized as a matter of gravest

national concern. Aspects of the problem have been liti

gated in at least twenty-one states during the last twenty

years. These cases reveal covenants affecting areas as

large as one thousand lotsa and twenty-six city blocks.1*

These restrictions do not run only against Negroes. Courts

have been asked to exclude from the ownership or occu

pancy of land persons of Arabian, Armenian, Chinese,

Ethiopian, Greek, Hindu, Korean, Persian, Spanish and

Syrian ancestry as well as American Indians, Hawaiians,

Jews, Latin Americans and Puerto Eicans, irrespective of

citizenship. A petition for certiorari now pending before

this Court shows a clergyman excluded from occupancy of

the parsonage of his church.0 Such are the consequences

of the restrictive covenant.

Surely, a device of unreason and bigotry cannot be per

mitted to destroy the essential character and oneness of

America as a community,—“ not while this Court sits.”

a Mays v. Burgess, 147 F. (2d) 869 (Diitrict of Columbia— 1944)~

b Phillips v. Wearn, 226 N. C. 290 (1946).

c Trustees of the Monroe Avenue Church of Christ et al. vT Perkins

et al., No, 153, October Term, 1947,

j :

I

Racial Covenants Restrictive of Occupancy Have

Developed Through an Uncritical Distortion

of Doctrines Concerning Restrictions

on Use of Property.

Doctrines originating in and having proper application

to limitations of how property shall be used have in recent

years been distorted and unjustifiably applied to limitations

of who shall occupy property.

A. Historical Development of Devices Restrictive

of the Use of Real Property,

While the law relative to restrictions on the use of real

property developed along lines historically different from

those which led to the development of the doctrines relative

to illegal restraints on alienation, the basic considerations

of policy underlying each are essentially the same. A wise

and ancient policy, which promotes those principles of law

which permit the most beneficial use of the land resources

of the country, is best served by allowing property to be

freely alienable so that it may come into the hands of him

who can best use it, and the same policy allows a person to

put the property to the lawful use which he considers most

advantageous.

The law has extended no greater favor to restrictions

on the free use and enjoyment of land than to restrictions

upon the free alienation of land. This is evidenced by the

reluctance and, in some cases, the refusal, of courts to ex

tend traditional devices or to create new devices whereby

a more complete and simpler expedient for controlling use

of another’s land would be afforded.

12

The development of the law relative to restrictions on

use is more obscure than that relative to restrictions on

alienation. Two devices, perhaps, antedated the restric

tive covenant. An owner of land might convey a part

thereof subject to a condition subsequent that the land con

veyed should not be used in a particular manner so as to af

fect the part retained, upon breach of which condition the

conveyor might exercise his power to terminate the

grantee’s estate. Or the owner of one parcel might ac

quire by grant or reservation an easement restricting uses

to be made upon another parcel. Neither could accomplish

a restriction of land use save within narrow limits.1

Covenants respecting the use of land developed slowly,

and within similarly circumscribed areas. Enforcement

in the law courts of covenants, except as between the par

ties thereto, was a deviation from the common law rules

that a chose in action was nonassignable, and that only a

party to a contract can be held liable thereon.2

It appears that prior to the middle of the sixteenth cen

tury, both the benefit and burden of a covenant contained

in a lease ran to an assignee of the leasehold, so that the as

1 Both devices necessitated an instrument under seal. The power

of termination for breach of condition could neither be assigned inter

vivos nor devised, and easements the benefit of which was in gross

did not run either as to benefit or burden. Common law easements

could be created only in a limited class of cases, the law not favoring

the creation of new forms of easements not known to the early law.

Neither device was afforded a remedy by which actual or literal per

formance of the restriction could be judicially compelled. Stone,

Equitable Riqhts and Liabilities of Stranqers to a Contract, 18 Col.

L. Rev. 291-293.

2 “ The terms ‘real covenants’ or ‘covenants running with the land’

are of course metaphorical. The covenants are always personal in

the sense that they are enforced in personal actions for damages, etc.;

and they cannot actually run with the land as Coke seemed to think;

the question is merely how far the transfer of an interest in land will

also transfer either the benefit or the burden of covenants concerning

it.” Clark, Covenants and Interests Running with Land, 73,

13

signee of tlie lessee might be held liable on the covenant,

and became entitled to enforce it. But, neither the benefit

of the covenant passed to, nor the burden of the covenant

was imposed upon, the assignee of the reversion.3 In 1540,

the Statute of Covenants4 declared that lessors and their

assigns should have the right to enforce covenants and con

ditions against lessees and their assigns, and conferred

reciprocal rights upon lessees and their assigns to enforce

covenants against lessors and their assigns.5 6 Limitations

upon the running of such covenants were imposed in

Spencer’s case,0 which declared that the covenant must

“ touch or concern” the land demised, otherwise it would

not run, and that even though the covenant touched or con

cerned the land, if it concerned likewise a thing which was

not in being at the time of the demise, but which was to be

built or created thereafter, assignees would not be bound

unless they were expressly mentioned.7 Where the covenant

was made between owners in fee simple, not in connection

with a lease, the additional requirement of “ privity of

3 1 Wms. Saunders, (1st Am. ed.) 240a, n. 3 ; 1 Sm ith ’s L eading

Cases ('8th ed.) 150; 1 T iffany, Landlord & T enant, 968-969.

4 32 Hen. V III, c. 34 (1540).

8 This statute was not enacted entirely out of a desire to broaden

the covenant device. “ The reason for the enactment of the statute

was that the monasteries and other religious and ecclesiastical houses

had been dissolved and their lands had come into the possession of the

king, who distributed them to the lords. Much of the lands was sub

ject to leases when they fell into the hands of the king, and the monks

had inherited in leases various covenants and provisions for their

benefit and advantage. At the common law no person could take the

benefit of any covenant or condition except such as were parties or

privies thereto, so that the grantees of the king could not enforce the

covenants in the leases. These things were recited in the preamble,

and the statute was enacted to give to the grantees of the king the

same remedies that the original lessors might have had." Purvis v.

Shuman, 273 111. 286, 112 N. E. 679 (1916).

6 5 Coke 16.

7 These limitations caused no little confusion in the law. Clark,

op. cit. supra note 8, 74 et seq.

14

estate” must be satisfied8 and, even when all requirements

were satisfied, the English courts refused to permit the

running of the burden of such a covenants so as to be en

forceable against a transferee of the land.9 Until equity

commenced the exercise of its peculiar powers in the cov

enant field, the sole remedy in event of breach was, of

course, an action for damages.

Prior to the middle of the nineteenth century, covenants

not to use land in a particular manner were specifically en

forceable in equity by injunction against the promisor where

the requisite inadequacy of a legal remedy existed.10 11 New

developments followed the decision in 1848 in Tulk v. Mox-

hay,u which established that a covenant as to the use of land

might affect a subsequent purchaser who takes with notice

thereof, equity in such cases enjoining a use of the land in

violation of the covenant.12 The requirements of touching

and concerning privity of estate were swept aside13 and a

more workable restrictive device created.

With the urbanization of the population, and the more

crowded conditions of modern life, the desire to secure suit

8 Here again the requirement was not exact, and divergent views

followed. Clark, op. cit. supra note 8, 91 et seq.

9Austerberry v. Oldham, 29 Ch. D. 750; Clark, op. cit. supra

note 8, 113; 3 T iffany, R eal Property (3rd ed.) 445.

10 Martin v. Nutkin, 2 P. Wms. 266; Lord Grey v. Saxon, 6

Ves. 106.

11 2 Phil. 774, 41 Eng. Rep. 1143.

12 Whether these restrictions are enforced as contracts concerning

the land, or as servitudes or easements on the land, is still a subject

of Speculation. The opposing theories are analyzed in Clark, op. cit.

supra note 8, 149 et seq.

13 Clark, op. cit. supra note 8, 150.

15

able home surroundings led to a demand for real estate

limited solely to development for residential purposes. This

natural desire of householders has been exploited by land

developers and realtors so that the restriction of particular

areas of property in or near American cities to residential

use is now becoming- the rule rather than the exception. The

legal machinery to achieve this end has been found in the

main not in the ancient rules of easements or covenants

enforceable only at law, but in the activities of courts of

equity in enforcing restrictions as to use of land when

reasonable. Within its historical framework, the covenant

enforceable in equity has thus achieved widespread success

and popularity as a device capable of accomplishing a

measurable control over uses to which a neighbor’s land

might be put. Its accomplishments in this wise advanced

the public weal by promoting healthier, safer and morally

superior residential areas through specialization of use

activities upon propinquous lands. Such limited use restric

tions were accomplished without entrenchment upon the

tenet of individual freedom of use and enjoyment of prop

erty.

B. The Distinction Between Restrictions Upon the

Use of Property and Restrictions Upon the

Occupancy of Property by Members of Un

popular Minority Groups.

From its inception until the wane of the last century,

the restrictive covenant enforceable in equity was always

and only an agent selective of the type of use which might

be made of another’s land. Neither the history of its de

velopment nor the economic or social justifications for its

judicial enforcement disclose a basis for its employment as

a racially discriminatory preventive of occupancy. This

novel twist in the law wTas introduced by historical acci

16

dent,14 and has survived only because of judicial indifference

toward the consequent distortion of fundamental concepts

and principles and the economic and social havoc thereby

wrought:

1. The distinction between restrictions on use and those

on occupancy is fundamental, but is completely ignored.

The concept of use restrictions before the birth of racial

restrictive covenants had been, and with their sole excep

tion, still is in terms of type of structure or type of activity

upon the land. Property was left open to occupancy by

any person, including him who engaged in the inhibited

activity in another place. The distinction is between who

occupies the land, and what he does with it. Restrictions

against manufacturing uses prevented the operation of

factories on the restricted land, but industrialists and em

ployees might nevertheless establish their residences there;

those against taverns, gambling dens and houses of prosti

tution did not prohibit occupany by tavernkeepers, gamblers

and prostitutes who plied their trade elsewhere.

2. The cases enforcing nonracial covenants dealt with

restrictions possessing the equality of personal applica

tion implicit in reasonableness. Race or other personal

14 The law relative to the enforceability in equity of racial restric

tions against occupancy stems from Los Angeles Investment Co. v.

Gary, 181 Cal. 680, 186 P. 596 (1918), which followed two years

behind Buchanan v. Worley. The decision was 3-2 and, as the court

expressed in its opinion, it was not “ favored by either brief or argu

ment on behalf of the respondents,” (186 Cal. 681) the Negro occu

pants. The restriction was sought to be imposed by condition subse

quent, rather than by covenant, and the court pointed out that “ what

we have said applies only to restraints on use imposed by way of

condition and not to those sought to be imposed by covenant merely.

The distinction between conditions and covenants is a decided one and

the principles applicable quite different.” (Id., 683). Nevertheless,

and notwithstanding the fallacy in analogizing a restriction on occu

pancy to one on use, courts subsequently faced with the racial occu

pancy covenant followed the lead supplied by this case.

17

considerations could not be factors in such an equation;

only type of use could be important. All persons, irrespec

tive of race, were alike bound by the restriction and alike

free to make any unrestricted use of the land. Irrespective

of race, every owner of the restricted land possessed a

perfect privilege to put the land to any use uninhibited by

the covenant; nor was race ever an exemption from the

operation of the restriction for, irrespective of race, every

owner of the restricted land was bound to observe the

restriction. Racial covenants, however, ignore all reason

able considerations and ground their discriminations point

edly on race alone.

3. Nonracial covenants effected only prohibitions which

accorded with the public good. The proscribed uses were

usually illegal, immoral, or unsafe to the community.

Many constituted indictable offenses or abateable nuisances.

All were of such character that they could better be con

ducted elsewhere. The same prohibitions could be, and

frequently were, effected by legislation.15 But occupancy

of land by members of unpopular minority groups does

not fall within the above categories.16 The absence of all

relation to the public health, morals, safety or general wel

fare precludes its prohibition by statute.17

15 Standard Oil Co. v. Marysville, 279 U. S. 582; Gorieb v. Fox,

274 U. S. 603 ; Zahn v. Board of Public Works, 274 U. S. 325 ; Euclid

v. Ambler Realty Co., 272 U. S. 365; St. Louis Poster Advertising

Co. v. St. Louis, 249 U. S. 269; Pierce Oil Co. v. Hope, 248 U. S.

498; Thomas Cusack Co. v. Chicago, 242 U. S. 526; Northwestern

Laundry Co. v. Des Moines, 239 U. S. 486; Hadacheck v. Sabastian,

239 U. S. 394; Reinman v. Little Rock, 237 U. S. 171; Laurel Hill

Cemetery v. San Francisco, 216 U. S. 358; Welch v. Swasey, 214

U. S. 91; Bacon v. Walker, 204 U. S. 311; Fischer v. St. Louis, 194

U. S. 361.

16 Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60; Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U. S.

668- City of Richmond v. Deans, 281 U. S. 704; Crist v. Henshaw,

196 Old. 168 (1945).

17 See Point V of this brief.

18

4. Nonracial covenants did not subvert individual rights

of property. They affected only a single constituent of

property—use; all other attributes of property, including

occupancy, retained their traditional freedom. The curtail

ment in freedom of user thus effected was a compromise

justified by the benefit flowing from the reconciliation of

the innumerable and conflicting freedoms of use possessed

by others. Racial covenants destroy the essence of prop

erty ; they represent an obliteration, not a compromise.

5. Nonracial covenants drew the substance of their

validity from their purpose and effect as engineers of su

perior residential areas. Racial occupancy restrictions

cannot reasonably be considered as improving the health,

morals, safety or general welfare of the occupants of the

restricted area.18 On the contrary, and at the same time,

their cumulative economic and social effects have impaired

the health, morals, safety and general welfare of all.19

Such use of land as is characteristically proscribed by

nonracial restrictive covenants is likely to constitute a

serious injury to the neighboring landowner and a matter

of concern to the state. But in our democratic society the

skin color, national origin or religion of the occupant of

property cannot be a legal injury to a neighbor or a matter

of concern to the state.

The constitutional consequence of the foregoing distinc

tions is that this Court has upheld state statutes imposing

various reasonable restrictions on use20 but, beginning with

Buchanan v. Warley, has uncompromisingly struck down

every effort of the states to impose racial residential restric

tions by legislation.21 That conclusion was inevitable.

18 See cases cited in footnote 16 supra.

19 See Point V of this brief.

20 See cases cited in footnote 15 supra.

21 See cases cited in footnote 16 supra.

19

II

The Right to Use and Occupy Real Estate as a Home

is a Civil Right Guaranteed and Protected by the

Constitution and Laws of the United States.

Blaekstone pointed out that the third absolute right “ is

that of property, which consists in the free use, enjoyment,

and disposal of all his acquisitions, without any control or

diminution, save only by the laws of the land.” 22 This

right is expressly protected by the Fourteenth Amendment

and the Civil Rights Acts23 against invasion by the states

on racial grounds.

The Congressional debates after the adoption of the

Thirteenth Amendment and preceding the enactment of the

Civil Rights Act of 1866 show that Congress intended to

protect the fundamental civil rights of the freedmen. High

on the list of rights to be protected was the right to own

property. Some doubts were expressed by the opponents

of the measure as to its constitutionality, and particularly

the right of Congress to confer citizenship upon the former

slaves without an amendment.24 But neither the proponents

of the Civil Rights Act nor its opponents doubted that citi

zens of the United States had an inherent right to acquire,

own and occupy property.25 After the enactment of the

Fourteenth Amendment, Congress reenacted the Civil

22 Blackstone’s Commentaries, p. 138.

23 See: 8 U. S. C. 42.

24 Flack, Adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment (John Hopkins

Press, 1908), p. 21.

25 See: Debate between Senators Cowan and Trumbull, Congres

sional Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Session, Part 1, pp. 499-500.

20

Rights Act with a few modifications, expressly stipulating

therein:

“ All citizens of the United States shall have the

same right in every State and Territory as is en

joyed by white citizens thereof to inherit, purchase,

lease, sell, hold and convey real and personal prop

erty. ’ ’ 26

Throughout the debates on the Amendment and the

Civil Rights Bill there is a clear perception that freedom

for the former slave without protection of his fundamental

right to own real or personal property was meaningless.

One of the Senators cited as an example of the oppression

from which the freedmen must be protected the fact that in

1866 in Georgia “ if a black man sleeps in a house over

night, it is only by leave of a white man,” 27 and another

asked: “ Is a freeman to be deprived of the right of ac

quiring property, having a family, a wife, children,

home ? ” 28

In 1879 this Court construed the Fourteenth Amendment

as containing a positive immunity for the newly freed slaves

against “ legal discriminations * * * lessening the security

of their enjoyment of the rights which others enjoy” 29 and

in 1917 this Court construed the Civil Rights Act as deal

ing “ with those fundamental rights in property which it

was intended to secure upon the same terms to citizens of

every race and color. ’ ’ 30

In the Civil Rights Cases this Court, while holding

that sections of the Civil Rights Act were unconstitutional

26 8 U. S. C. 42.

27 Congressional Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Session, Part 1, p. 589.

28 Senator Howard, Ibid., p. 504.

29 Strauder v. W est Virginia, 100 U. S. 303, 308.

30 Buchanan V, Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 79.

2 1

because they applied to individual action, at the same time

emphasized the application of the Fourteenth Amendment

to state action of all types, whether legislative, judicial or

executive.

“ In this connection it is proper to state that civil

rights, such as are guaranteed by the Constitution

against state aggression, cannot be impaired by the

wrongful acts of individuals, unsupported by state

authority in the shape of laws, customs or judicial or

executive proceedings. ’ ’ 31

It was thus made clear that the Fourteenth Amendment does

prohibit the wrongful acts of individuals where supported

“ by state authority in the shape of laws, customs, or ju

dicial or executive proceedings.” (Italics ours.)

Among the rights listed as protected against legislative,

judicial and executive action of the states was the right “ to

hold property, to buy and to sell.”

The right that petitioners assert is their civil right to

occupy their property as a home—the same right recognized

by this Court in Buchanan v. Warley:

“ The Fourteenth Amendment protects life, lib

erty, and property from invasion by the States with

out due process of law. Property is more than the

mere thing which a person owns. It is elementary

that it includes the right to acquire, use, and dispose

of it. The Constitution protects these essential at

tributes of property * * * ” 32

In the instant case the respondents seek by means of

state court action to evict petitioners from the property

they own and are occupying as a home. On the face of the

31 109 U. S. 3, 17.

82 245 U. S. 60, 74.

pleadings they do not seek to divest petitioners of title.

But the effect of denying to petitioners the right to occupy

their property as a home in a residential neighborhood,

under any circumstances, is a denial of the civil right set

out above.

Ill

Under the Fourteenth Amendment, No State May Deny

This Civil Right to Any Person Solely Because of

His Race, Color, Religion, or National Origin.

A. It is Well Settled That Legislation Condition

ing the Right to Use and Occupy Property

Solely Upon the Basis of Race, Color, Religion,

or National Origin Violates the Fourteenth

Amendment.

Racial restrictions by states of the right to acquire, use,

and dispose of property are in direct conflict with the Con

stitution of the United States. The first efforts to establish

racial residential segregation were by means of municipal

ordinances attempting to establish racial zones. This

Court, in three different cases, has clearly established the

principle that the purchase, occupancy, and sale of prop

erty may not be inhibited by the states solely because of

the race or color of the proposed occupant of the prem

ises. 33

In Buchanan v. Warley, supra, an ordinance of the City

of Louisville, Kentucky, prohibited the occupancy of lots by

colored persons in blocks where a majority of the residences

were occupied by white persons and contained the same

88 City of Richmond v. Deans, 281 U. S. 704; Harmon v. Tyler,

273 U. S. 668; Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60.

prohibition as to white persons in blocks where the majority

of houses were occupied by colored persons. Buchanan

brought an action for specific enforcement of a contract of

sale against Warley, a Negro, who set up as a defense a

provision in the contract excusing him from performance

unless he should have the right under the lawTs of Kentucky

and of Louisville to occupy the property as a residence and

contended that the ordinance prevented him from occupy

ing the property. Buchanan replied that the ordinance

was in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In a unanimous opinion by Mr. Justice D ay, this Court

decided the following question:

“ The concrete question here is: May the occu

pancy, and, necessarily, the purchase and sale of

property of which occupancy is an incident, be in

hibited by the states, or by one of its municipalities,

solely because of the color of the proposed occupant

of the premises ? That one may dispose of his prop

erty, subject only to the control of lawful enactments

curtailing that right in the public interest, must be

conceded. The question now presented makes it

pertinent to inquire into the constitutional right of

the white man to sell his property to a colored man,

having in view the legal status of the purchaser and

occupant” (245 U. S. 60, at p. 75).

The decision in the Buchanan case disposed of all of the

arguments seeking to establish the right of a state to restrict

the sale of property by excluding prospective occupants be

cause of race or color:

Use and occupancy is an integral element of ownership

of property:

“ * * * Property is more than the mere thing

which a person owns. It is elementary that it in

cludes the right to acquire, use, and dispose of it.

24

The Constitution protects these essential attributes

of property. Holden v. Hardy, 169 U. S. 366, 391,

42 L. ed. 780, 790, 18 Sup. Ct., Eep. 383. Property

consists of the free use, enjoyment, and disposal of

a person’s acquisitions without control or diminu

tion save by the law of the land. 1 Cooley’s Bl. Com.

127.” (245 IT. S. 60, at p. 74.)

Racial residential legislation can not he justified as a

proper exercise of police power:

“ We pass, then, to a consideration of the case

upon its merits. This ordinance prevents the occu

pancy of a lot in the city of Louisville by a person of

color in a block where the greater number of resi

dences are occupied by white persons; where such

a majority exists, colored persons are excluded. This

interdiction is based wholly upon color; simply that,

and nothing more # #

“ This drastic measure is sought to be justified

under the authority of the state in the exercise of the

police power. It is said such legislation tends to pro

mote the public peace by preventing racial conflicts;

that it tends to maintain racial purity; that it pre

vents the deterioration of property owned and oc

cupied by white people, which deterioration, it is

contended, is sure to follow the occupancy of ad

jacent premises by persons of color.

“ It is urged that this proposed segregation will

promote the public peace by preventing race conflicts.

Desirable as this is, and important as is the preserva

tion of the public peace, this aim cannot be accom

plished by laws or ordinances which deny rights cre

ated or protected by the Federal Constitution.” (245

IT. 8. 60, at p. 81.)

Race is not a measure of depreciation of property:

“ It is said that such acquisitions by colored per

sons depreciate property owned in the neighborhood

25

by white persons. But property may be acquired by

undesirable white neighbors, or put to disagreeable

though lawful uses with like results.” (245 U. S. 60,

at p. 82.)

The issue of residential segregation on the basis of race

was squarely met and disposed of in the Buchanan case.

Each of the arguments in favor of racial segregation was

carefully considered and this Court, in determining the con

flict of these purposes with our Constitution, concluded:

“ That there exists a serious and difficult problem

arising from a feeling of race hostility which the law

is powerless to control, and which it must give a

measure of consideration, may be freely admitted.

But its solution cannot be promoted by depriving

citizens of their constitutional rights and privileges. ’ ’

(245 IT. S. 60, at pp. 80-81.)

The determination of this Court to invalidate racial resi

dential segregation by state action regardless of the alleged

justification for such action is clear from two later cases.

In the case of City of Richmond v. Deans, a Negro who

held a contract to purchase property brought an action in

the United States District Court seeking to enjoin the en

forcement of an ordinance prohibiting persons from using

as a residence any building on a street where the majority

of the residences were occupied by those whom they were

forbidden to marry under Virginia’s Miscegenation Statute.

The Circuit Court of Appeals, in affirming the judgment of

the trial court, pointed out: “ Attempt is made to distin

guish the case at bar from these cases on the ground that

the zoning ordinance here under consideration bases its

interdiction on the legal prohibition of intermarriage and

not on race or color; but, as the legal prohibition of inter

marriage is itself based on race, the question here, in final

analysis, is identical with that which the Supreme Court

26

has twice decided in the cases cited. [Buchanan v. Warley

and Ilarmon v. Tyler.] ” 84 This Court affirmed this judg

ment by a Per Curiam decision.85

The principles of the Buchanan case have also been ap

plied in cases involving the action of the legislature coupled

with the failure of individuals to act. In Ilarmon v. Tyler,

a Louisiana statute purported to confer upon all municipali

ties the authority to enact segregation laws, and another

statute of that state made it unlawful in municipalities

having a population of more than 25,000 for any white per

son to establish his residence on any property located in a

Negro community without the written consent of a majority

of the Negro inhabitants thereof, or for any Negro to estab

lish his residence on any property located in a white com

munity without the written consent of a majority of the

white persons inhabiting the community.

An ordinance of the City of New Orleans made it unlaw

ful for a Negro to establish his residence in a white com

munity, or for a white person to establish his residence in

a Negro community, without the written consent of a ma

jority of the persons of the opposite race inhabiting the

community in question. Plaintiff, alleging that defendant

was about to rent a portion of his property in a community

inhabited principally by white persons to Negro tenants

without the consent required by the statute and the ordi

nance, prayed for a rule to show cause why the same should

not be restrained.

Defendant contended that the statutes and the ordinance

were violative of the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. The trial court sustained defendant’s posi

tion. On appeal, the Supreme Court of Louisiana reversed,

85 281 TJ SiC7Q4°nd V' Deans’ C- C- A-—4th, 37 F. (2d) 712, 713,

27

and upheld the legislation. On appeal to this Court, the de

cision of the Supreme Court of Louisiana was reversed on

authority of Buchanan v. Warley. A like disposition of the

same legislation was had in the Circuit Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit in an independent case.

In the instant case, all of the alleged evils claimed to flowT

from mixed residential areas which are relied upon for

judicial enforcement of racial restrictive covenants were

advanced in the Buchanan and the other two cases as justifi

cation for legislative action to enforce residential segrega

tion. In the Buchanan case, this Court dealt with each of

the assumed evils and held that they could not be solved by

segregated residential areas and did not warrant the type

of remedy sought to be justified. Efforts to circumvent this

decision have been summarily disposed of by this Court.30

The right petitioners here assert is the civil right to

occupy their property as a home—the same right which was

recognized and enforced in Buchanan v. Warley.

B. Civil R igh ts A r e G u aran teed b y th e F ou rteen th

A m en d m en t A ga in st Invasion b y th e Judiciary.

It is equally well settled that the limitations of the Four

teenth Amendment apply to the exercise of state authority

by the judiciary. As long ago as 1879, in Ex Parte Vir

ginia,87 this Court specifically recognized that the judiciary

enjoyed no immunity from compliance with the require

ments of the Fourteenth Amendment. In that case the state

judge was held to he subject to the federal Civil Rights Act,

despite the plea that in selecting a jury in a manner which

excluded otherwise qualified persons solely on account of

their color, the judge was exercising a function of his judicial * 37

86 Harmon v. Tyler and City of Richmond v. Deans, supra.

37100 U. S. 339.

office. In an unbroken line of precedents since that time,

this Court has again and again reaffirmed this proposition.

For example, in Twining v. New Jersey,38 this Court said:

“ The law of the state, as declared in the case at

bar, which accords with other decisions # * per

mitted such an inference to be drawn. The judicial

act of the highest court of the state, in authoritatively

construing and enforcing its laws, is the act of the

state. * * # The general question, therefore, is,

whether such a law violates the Fourteenth Amend

ment, either by abridging the privileges or immuni

ties of citizens of the United States, or by depriving

persons of their life, liberty or property without due

process of law.” (211 U. S. 78, at pp. 90-91.)

It is readily conceded that the “ law” to which the Court

there referred was actually one of a series of rules, common

law as well as statutory, which had been developed by the

state authority, legislative and judicial, for the conduct of

criminal trials. So classified, the opinion demonstrates the

complete acceptance by this Court of the proposition orig

inally announced in Ex Parte Virginia, that the procedure

of state courts, whether provided by legislation or rule of

decision by state courts, must meet the requirements and

limitations of the Fourteenth Amendment.39

The obligation of the state judiciary to comply with the

limitations of the Fourteenth Amendment, however, is not

confined to procedure. On the contrary this Court has fre

quently tested decisions of state courts on matters of sub

stantive law against the requirements of the federal Consti

38 211 U. S. 78.

39 See also: Hysler v. Florida, 315 U. S. 411; Brmvn, Ellington &

Shields v. Mississippi, 297 U. S. 278 ; Moore v. Dempsey, 261 U. S.

86; Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587; Powell v. Alabama, 287 U. S.

4 5 ; Brinkerhoff Fans Co, v. Hill, 281 U. S. 673 ; Carter v. Texas,

177 U. S. 442,

29

tution and has equally frequently recognized that it was

obliged so to do by the Fourteenth Amendment. This is

aptly demonstrated by the opinion of this Court in Cant

well v. Connecticut,40 In that case, it will be remembered,

the petitioner had been convicted on an indictment which

contained four counts charging violation of express statu

tory prohibitions, and a fifth count which charged a common

law breach of the peace. The petitioner contended in apply

ing for certiorari that his conviction on each of these counts

violated the Fourteenth Amendment. This Court recognized

that both the express statutory provisions and the substan

tive determination of the common law obligation by the

state court raised similar constitutional questions under

the Fourteenth Amendment. In fact, this Court stated:

“ Since the conviction on the fifth count was not based

upon a statute, but presents a substantial question

under the federal Constitution, we granted the writ

of certiorari in respect of it.” (310 U. S. 266 at p.

301.)

Again, at pp. 307-308:

“ Decision as to the lawfulness of the conviction (on

the fifth count) demands the weighing of two con

flicting interests. The fundamental law declares the

interest of the United States that the free exercise

of religion be not prohibited and that freedom to

communicate information and opinion be not

abridged. The state of Connecticut has an obvious

interest in the preservation and protection of peace

and good order within her borders. We must de

termine whether the alleged protection of the State’s

interest, means to which end would, in the absence

of limitation by the federal Constitution, lie wholly

within the State’s discretion, has been pressed, in

this instance, to a point where it has come into fatal

40 3 1 0 U. S. 296.

30

collision with the overriding interest protected by the

federal compact.”

At the next term this Court, even more forcibly enunci

ated the requirement that decisions by state courts on sub

stantive matters satisfy the requirements of due process.

In Milk Wagon Drivers Union of Chicago, Local 753 v.

Meadowmoor Dairies, Inc.,41 this Court granted certiorari

to review an injunction of an Illinois court issued on the

authority of that state’s common law which prohibited

picketing, peaceful and otherwise, by a labor union. Despite

a disagreement among the members of the Court as to the