J. Greenberg Statement on Why a National Office for the Rights of the Indigent

Press Release

November 22, 1966

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 4. J. Greenberg Statement on Why a National Office for the Rights of the Indigent, 1966. 56a0ed56-b792-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4d9e7afc-ca56-4033-9986-212dff04c034/j-greenberg-statement-on-why-a-national-office-for-the-rights-of-the-indigent. Accessed March 10, 2026.

Copied!

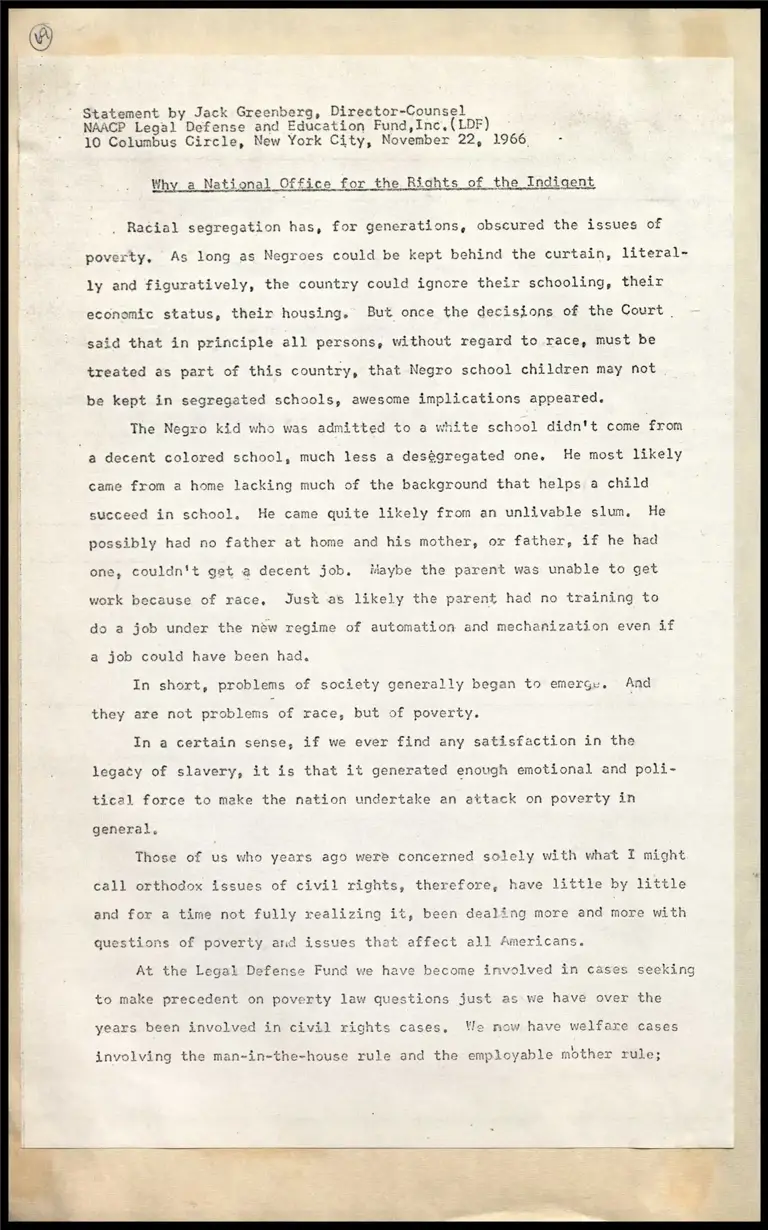

Statement by Jack Greenberg, Director-Counsel

NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund,Inc. (LDF)

10 Columbus Circle, New York City, November 22, 1966. é

Why a National Office for the Rights of the Indigent

Racial segregation has, for generations, obscured the issues of

poverty, As long as Negroes could be kept behind the curtain, literal-~

ly and figuratively, the country could ignore their schooling, their

economic status, their housing. But once the decisions of the Court .

said that in principle all persons, without regard to race, must be

treated as part of this country, that Negro school children may not

be kept in segregated schools, awesome implications appeared.

The Negro kid who was admitted to a white school didn't come from

a decent colored school, much less a deségregated one. He most likely

came from a home lacking much of the background that helps a child

succeed in school. He came quite likely from an unlivable slum, He

possibly had no father at home and his mother, or father, if he had

one, couldn't get a decent job. ilaybe the parent was unable to get

work because of race, Just as likely the parent had no training to

do a job under the néw regime of automation and mechanization even if

a job could have been had.

In short, problems of society generally began to emergu. And

they are not problems of race, but of poverty.

In a certain sense, if we ever find any satisfaction in the

legaty of slavery, it is that it generated enough emotional and poli-

tical force to make the nation undertake an attack on poverty in

general.

Those of us who years ago were concerned solely with what I might

call orthodox issues of civil rights, therefore, have little by little

nd more with

questions of poverty and issues that affect al] Americans.

car

ome involved in cases seeking 3 At the Legal Defense und we have bec

to make precedent on poverty law questions just as we have over the

years been involved in civil rights cases, “le mow have welfare cases

» involving the man-in-the-house rule and the employable mother rule;

JACK GREENBERG

housing cases, involving the rights of public housing agencies to evict

without a hearing, or to refuse to house mothers with illegitimate

children; in private housing, there is litigation over the right of

poor persons to defend eviction proceedings without having to post a

bond in twice the amount of the rent; in criminal prosecutions, there

are suits over the right of an indigent to be released without bail

where an affluent person would have been released because he had the

money to put up bail; and the right of an accused misdemeanant to

request and have granted court appointed counsel.

How the National Office for the Rights of the Indigent Will Work

It will work in conjunction with all local law offices concerned

with the problems of the poor in an attempt to provide thorough and

expert advocacy of major appellate cases, consistent and controlled

development of precedent, and where appropriate, coordination of legal

approaches to comparable problems.

Many cases for poor clients will be settled simply by proper

advice or by litigation that does not go beyond a trial or negotiation.

But the real task of making new law for the poor will of necessity

require much appellate work and the fashioning of strategy and goals

which have as much nationwide impact as possible.

<30=