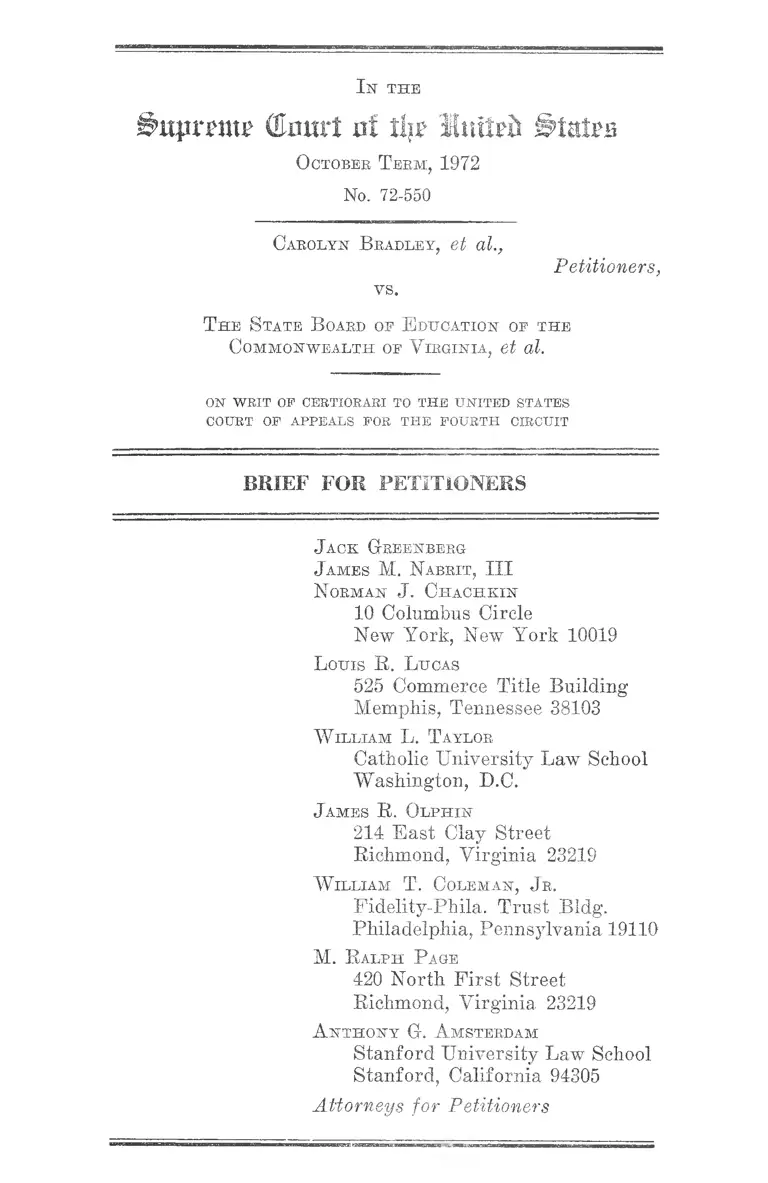

Bradley v. State Board of Education of Virginia Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bradley v. State Board of Education of Virginia Brief for Petitioners, 1973. 4c57a4a2-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4dc48eb4-cc77-46b5-a052-af5faea77f31/bradley-v-state-board-of-education-of-virginia-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

§at|irjmu> (Emir! ni tljr lu itri Stairs

O ctober T e r m , 1972

No. 72-550

C arolyn B radley , et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

T h e S tate B oard op E du ca tio n of t h e

C o m m o n w e a l t h of V ir g in ia , et al.

ON w r i t o f c e r t i o r a r i t o t h e u n i t e d s t a t e s

COURT OF APPEALS FOE T H E FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

J ack G reen berg

J a m es M. N a brit , III

N orm an J . C h a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Louis R . L ucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

W il l ia m L. T aylor

Catholic University Law School

Washington, D.C.

J a m es R. Ol p h in

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

W il l ia m T. C o lem a n , J r.

Fidelity-Phila. Trust Bldg.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19110

M. R a l p h P age

420 North First Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

A n t h o n y G. A m sterdam

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions Below....................................... 1

Jurisdiction ........ .........— ............. -.............................. 4

Question Presented ................................. 4

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved........ 4

Statement ................... 5

I. Segregation in tlie Schools of the Greater Rich

mond Area .............................................. 5

A. Maintenance and Expansion of the Dual

School Systems ....................... 11

1. Delays in Compliance with Brown ........ 11

2. Perpetuation of the Dual System Through

School Construction.................................. 16

3. The Role of the State ....... ..... ................. 18

4. Crossing Division Lines for Segregation 22

B. The Metropolitan Context .......... 24

1. Unity of the Metropolitan A rea .............. 25

2. Demographic Trends ................................ 30

II. The Proceedings Below........ .............................. 35

A. Litigation from 1961 to 1970 ......................... 35

B. Proceedings on the Motions for Further Re

lief and to Add Parties ........ 36

C. The Findings and Order of the District Court 42

D. The Court of Appeals’ Decision................... 50

11

PAGE

Summary of Argument ................................................ 51

Argument—•

I. Introduction .......................... ........... ................... 56

II. The District Court Did Not Lack Power to Order

an Inter-Division Desegregation P la n ............... 62

A. The Scope of Federal Judicial Power to Ter

minate Dual School Systems ......................... 62

B. The Court of Appeals’ Objections to an Inter-

Division Desegregation Plan .................... 73

III. The District Court Did Not Abuse Its Discretion

in Ordering an Inter-Division Desegregation

Plan ...................................................................... 82

A. Crossings of the Lines to Promote Segrega

tion and Other State Interests ..................... 84

B. The Indurate Quality of Segregation in the

Bichmond Area Schools ................................ 86

Conclusion .............................................. 99

Appendix A—•

The Constitutional Basis of the District Court’s

Desegregation O rder........ .............. l a

Appendix B—

The Basis of the District Court’s Approval of

Consolidation as a Means of Inter-Division Deseg

regation ...................................... 16

Ill

PAGE

A p p e n d ix C—

The Bole of Virginia State School Authorities in

School Administration and Policy Making............ 1c

A p p e n d ix D—

The Practical Operation of the District Court's

Desegregation Order ........... ........... ...... .... ............ Id

A p p e n d ix E—

The History of Localism and Centralism in Vir

ginia Educational Administration and Policy___ le

Ap p e n d ix P —

Forces Containing Blacks Within Richmond........ If

T able of A u t h o b it ie s

Cases:

Adkins v. School Bd. of Newport News, 148 F. Supp.

430 (E.D. Va.), aff’d 246 F.2d 325 (4th Cir.), cert.

denied, 355 U.S. 855 (1957) ............... .......... ............ 19n

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S. 19

1969) ________ ________ _______ ________ _...38n, 68n

Allen v. County School Bd., 207 F. Supp. 349 (E.D. Va.

1962) ........................................................................... 2e

Atkin v. Kansas, 191 U.S. 207 (1903) ...... .................. 78n

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962) ___________ ____ 77

Board of Supervisors v. County School Bd., 182 Va.

266, 28 S.E.2d 698 (1944) _____ _____ ____ ______ le

Bradley v. Milliken, 6th Cir. Nos. 72-1809, 1814, decided

December 8, 1972 (rehearing en banc pending) ...... 78n

IV

PA G E

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103

(1965) ...............................................................13n, 36, 91n

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 462 F.2d 1058 (4th

Cir. 1972) — .......... ................................................ passim

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 456 F.2d 6 (4th

Cir. 1972) ............................................ ....................... 3

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 345 F.2d 310 (4th

Cir.), rev’d 382 U.S. 103 (1965) ........................... .....3,35

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 317 F.2d 429 (4th

Cir. 1963) ................................ ....................................3, 35

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 338 F.Supp. 67

(E.D. Ya. 1967) ...........— .....................................passim

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 325 F.Supp. 828

(E.D. Ya. 1971) ........... .............................................. 3

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 324 F.Supp. 456

(E.D. Ya. 1971) ........... ............. .............. ............. . 2

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 324 F.Supp. 439

(E.D. Va. 1971) ................. ....................................... 2

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 324 F.Supp. 401

(E.D. Ya. 1971) ......................................... ................ 3

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 324 F.Supp. 396

(E.D. Ya. 1971) .......... .............................. ................ 3

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 51 F.R.D. 139

(E.D. Va. 1970) ...................................... ................... 2

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 317 F.Supp. 555

(E.D. Ya. 1970) ........ ................................. ............... 2

Brewer v. School Bd. of Norfolk, 456 F.2d 943 (4th

Cir.), cert, denied, 406 U.S. 905 1972 ........ ................ 9 On

Brewer v. School Bd. of Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37 (4th Cir.

1968) ..................................................... ............33n,3f

Broughton v. Pensacola, 93 U.S. 266 (1876) ............ 77n

Brown v. Bd. of Educ., 349 U.S. 294 (1955) _______passim

Brown v. Bd. of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ......... passim

v

PA G E

Brown, v. Swann, 35 U.S. (10 Pet.) 497 (1836) .......... 63n

Buchanan v. War ley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917) .... If

Calhoun v. Cook, 451 F.2d 583 (5th Cir. 1971) .......... 78n

Calhoun v. Cook, 430 F.20 1174 (5th Cir. 1970) ___ 38n

Camp v. Boyd, 229 U.S. 530 (1913) ................. .............. 63

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd., 396 U.S.

290 (1970) ....... ................... ........................ .......... 38n

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282 (1950) _______ __ ____ 72n

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 458 F.2d 1167 (2d Cir.

1972) ............................. .............................................. 72n

City of Richmond v. Deans, 281 U.S. 704 (1930) ......... If

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, 426 F.2d 1035

(8th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 402 U.S. 952 (1971) .... 4f

Comanche County v. Lewis, 133 U.S. 198 (1890) ___ 77n

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ..... ............... ....... 80

Davis v. Board of School Commr’s, 402 U.S. 33

(1971) ........................................ ....... ................ .passim

Davis v. County School Bd., Q.T. 1954, No. 3 ....... ...... 19n

Drummond v. Acree, 409 U .S .----- (1972) ................... 59n

Ford Motor Co. v. United States, 405 U.S. 562 (1972) .. 74n

Franklin v. Quitman County Bd. of Educ., 288 F.Supp.

509 (N.D. Miss. 1968) ................ ......... ............ ....... 81n

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (I960) ................. 78n

Graham v. Folsom, 200 U.S. 248 (1906) .................. 78n

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430 (1968) .... ......... ............... .......... ...............passim

Griffin v. County School Bd. of Prince Edward County,

377 U.S. 218 (1964) ............... ....................... .20n, 64, 80n

Griffin v. State Bd. of Educ., 296 F. Supp. 1178 (E.D.

Va. 1969) ..................................................... .............. 91n

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) .......... 72n

V I

PA G E

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Bd., 197 F. Snpp.

649 (E.D. La. 1961) (three-judge court), aff’d 368

U.S. 515 (1962) .......................... ..............-............... 80n

Haney v. County Bd. of Educ., 429 F.2d 364 (8th Cir.

1970) ................ ................. .................................. ....... 77

Haney v. County Bd. of Educ., 410 F.2d 920 (8th Cir.

1969) ............................-.....-.... ............ -.... - 78n

Harrison v. Day, 200 Va. 439, 106 S.E.2d 636 (1959).... 20n

Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, 461 F.2d 1171 (5th Cir.

1972) ......................................................................-.... 72n

Hecht v. Bowles, 321 U.S. 321 (1944) ........ .................. 63

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dist.,

433 F.2d 387 (5th Cir. 1970) ...................................... 85n

Hobson v. Hansen, 269 F. Supp. 401 (D.D.C. 1967)

aff’d sub nom. Smuck v. Hobson, 408 F.2d 175 (D.C.

Cir. 1969) .......... .......... ..................................-........... 72n

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 IJ.S. 385 (1969) ..................... 77

Hunter v. Pittsburgh, 207 U.S. 161 (1907) ......... ........ 77

James v. Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331 (E.D. Va.) appeal

dismissed, 359 U.S. 1006 (1959) ...........................20n, 91n

Kennedy Park Homes Assn., Inc. v. City of Lacka

wanna, 436 F.2d 108 (2d Cir. 1970) _____ ___ ____ 72n

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 448 F.2d 746 (5th

Cir. 1971), 455 F.2d 978 (5th Cir. 1972) .................. 78n

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 267 F. Supp. 458,

aff’d sub nom. Wallace v. United States, 389 U.S. 215

(1967) .................................. .. ............................. ...... 81n

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) ..... ... 64

Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803) .... 63n

McLeod v. County School Bd. of Chesterfield County,

Civ. No. 3431 (E.D. Va.) .......... ............ ................11,14n

V1X

PA G E

MeNeese v. Board of Educ., 373 U.S. 668 (1963) ........ 64

Mitchell v. Robert De Mario Jewelry, Inc., 361 U.S. 288

(1960) ......................................................................... 64

Mobile v. Watson, 116 U.S. 289 (1886) ......................... 77n

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961) ................. .... ...... 63n

Mount Pleasant v. Beckwith, 100 U.S. 514 (1879) ....... 77n

N.A.A.C.P. v. Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503 (E.D. Va. 1958),

rev’d on other grounds sub nom. Harrison v.

N.A.A.C.P., 360 U.S. 167 (1959) .......... .............. ....... 88n

North Carolina State Bd. of Educ. v. Swann, 402 U.S.

43 (1971) ....................................... 59n, 60n, 76, 77, 82n, 84

Palmer v. Thompson, 403 U.S. 217 (1971) ................... 72n

Porter v. Warner Holding Co., 328 U.S. 395 (1946) ... 63

Raney v. Board of Educ. of the Gould School Dist.,

391 U.S. 443 (1968) ..................................................64, 74

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) ........ ................ 78n

Robinson v. Shelby County Bd. of Educ., 330 F. Supp.

837 (W.D. Tenn. 1971), aff’d 467 F.2d 1187 (6th Cir.

1972) ........................................................................ 78n

School Bd. of Prince Edward County v. Griffin, 204 Va.

650, 133 S.E.2d 565 (1963) ................... .......... ......... 20n

Shapleigh v. San Angelo, 167 U.S. 646 (1897) ............ 77n

Spencer v. Kugler, 326 F. Supp. 1235 (D.N.J. 1971),

aff’d per curiam, 404 U.S. 1027 (1972) ..................... 74

Swann v. Charlotte-Meeklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S.

1 (1971) ...................................... .............. .......... passim

Swann v. Charlotte-Meeklenburg Bd. of Educ., 431

F.2d 138 (4th Cir. 1970), rev’d 402 U.S. 1 (1971) ....37, 3f

Taylor v. Coahoma County School Dist., 330 F. Supp.

174 (N.D. Miss. 1970-1971), aff’d 444 F.2d 221 (5th

Cir. 1971) ............ 78n

V U 1

PAGE

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.8. 346 (1970) ......................... 72n

United States v. Armour & Co., 402 U.S. 673 (1971) .... 74n

United States v. Board of Educ. of Baldwin County,

423 F.2d 1013 (5th Cir. 1970) .................................... lb

United States v. Board of Public Instruction of Polk

County, 395 F.2d 66 (5th Cir. 1968) ......................... 17n

United States v. Board of School Comm’rs, 332 F.

Supp. 655 (S.D. Ind. 1971) ........ ................ ........... .. 72n

United States v. Crescent Amusement Co., 323 U.S.

173 (1944) ................................................................... 75n

United States v. Darby, 312 U.S. 100 (1941) .............. 77n

United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ., 372

F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966); aff’d en banc, 380 F.2d 385

(5th Cir. 1967) ................... ....................................... 79

United States v. Loew’s, Inc., 371 U.S. 38 (1962) ...... 75n

United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc., 334 U.S.

131 (1948) ................... ............................. .............. . 75n

United States v. Scotland Neck City Bd. of Educ., 407

U.S. 484 (1972) .......................... ..................74n, 78n, 99n

United States v. Texas, 321 F. Supp. 1043 (E.D. Tex.

1970), 330 F. Supp. 235 (E.D. Tex. 1971), modified

and aff’d, 447 F.2d 441 (5th Cir. 1971) ..............78n, 81n

United States v. United Shoe Machinery Corp., 391

U.S. 244 (1968) ............ 74n

United States v. United States Q-ypsum Co., 340 U.S.

76 (1950) ........................................ 75n

Virginian Railway Co. v. System Federation No. 40,

300 U.S. 515 (1937) _______ ___ ____ ______ ____ 64

Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451

(1972) ............................................... 'passim

IX

PA G E

Wright v. County School Bd. of Greensville County,

309 F. Supp. 671 (E.D. Va. 1970), rev’d 442 F.2d 570

(4th Cir. 1971), rev’d sub nora. Wright v. Council of

the City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451 (1972) ...........— 62n

Federal Statutes:

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) ......... .......................................... - 4

28 U.S.C. §2281 ............................................................. 42n

42 U.S.C. §1983 .......... .......... ............... -............ -----.... 63n

Rule 19, F.R.C.P...........................-.........................~~.... 38

State Statutes:

Virginia Acts 1959, Ex. Sess., ch. 32, p. 110 .............. 20n

Virginia Acts 1956, Ex. Sess., ch. 68, p. 69, 1 Race Rel.

L. Rep. 1103 ................... .............. ................- .........- 19n

Virginia Acts 1956, S.J.R. 3, p. 1213, 1 Race Rel. L.

Rep. 445 ................. .................................. -.......... ----- 19n

Va. Code Anno. §§22-1, -2, -7, -30, -34, -100.1 through

-100.12 (Repl. 1969) ................ ............. ..................... 5

Va. Code Anno. §§22-1.1, -2, -7, -21.2, -30, -32, -100.1,

-100.3 through -100.11, -126.1, -127 (Sapp. 1972) ..... 5

Va. Code Anno. §22-2, (Repl. 1969) ....... ............ ........ lc

Va. Code Anno. §22-6 (Repl. 1969) ------- ------- ------ 2c

Va. Code Anno. §22-7 (Repl. 1969) ......................—- 62n

Va. Code Anno. §22-21 (Repl. 1969) ............... ......... 3c

Va. Code Anno. §22-21.2 (Supp. 1972) ........................ 2c

Va. Code Anno. §§22-29.2 to 22-29.15 (Supp. 1972) .... 2c

Va. Code Anno. §22-30 (Supp. 1972) ............ 76, 91n, lc, Id

Va. Code Anno. §22-31 (Repl. 1969) ........ 2c

Va. Code Anno. §22-33 (Supp. 1972) ........................... 2c

Va. Code Anno. §22-37 (Supp. 1972) ....................... 2c

X

PA G E

Va. Code Anno. §22-99 (Repl. 1969) ......... ..... ........... 62n

Va. Code Anno. §22-100.1 (Snpp. 1972) ......... Id

Va. Code Anno. §22-100.3 (Snpp. 1972) .......... 2d

Va. Code Anno. §22-100.4 (Repl. 1969) .......... 2d

Va. Code Anno. §22-100.5 (Repl. 1969) .......... 2d

Va. Code Anno. §22-100.6 (Supp. 1972) ........ 2d

Va. Code Anno. §22-100.7 (Supp. 1972) .. . 2d

Va. Code Anno. §22-100.8 (Repl. 1969) .......... 2d

Va. Code Anno. §22-100.9 (Supp. 1972) ........ 2d

Va. Code Anno. §22-100.10 (Repl. 1969) ..................... 2d

Va. Code Anno. §22-117 (Supp. 1972) ........................... 2c

Va. Code Anno. §22-126.1 (Supp. 1972) . 2c

Va. Code Anno. §22-146.1 (Repl. 1969) ........... 3c

Va. Code Anno. §22-152 (Repl. 1969) .................. 3c

Va. Code Anno. §22-166.1 (Repl. 1969) ............ 3c

Va. Code Anno. §22-191 (Repl. 1969) ...... 2c

Va. Code Anno. §22-202 (Repl. 1969) ................... 2c

Va. Code Anno. §§22-232.18-232-31 ......................... 20n

Va. Code Anno. §22-276 (Repl. 1969) ........... 2c

Va. Code Anno. §§22-295, et seq. (Repl. 1969) .... 2c

Virginia Constitution of 1971, Art. V III, §§1-7.............5, lc

Virginia Constitution of 1902, §§129, 130, 132, 133 ....... 5

Other Authorities:

[1972] Ayer Directory of P ublications ....................... 27

W. Gates, The Making of Massive Resistance (1964).. 94n

B. Muse, Virginia’s Massive Resistance (1961) ......... . 94n

Rand, McNally & Co., [1972] Commercial Atlas &

Marketing Guide ................... .................. ....... ......... . 27n

K. and A. Taeuber, Negroes in Cities (1965) .......... .... 2f

XI

PAGE

United. States Bureau of the Budget, Office of Statis

tical Standards, S tandard M etro po lita n S ta tistica l

A reas (1967) ......... -.....— .......... -.......-..... .....-.......- ^9n

United States Comm’n on Civil Rights, 1 R e p o r t :

R acial I solation in t h e P u b l ic S chools (G.P.O.

1967 0-243-637) (1967) ......................... -.................- ?2n

U n it e d S tates D e p t , of C o m m er c e , B ureau o r t h e

Ce n s u s , C e n s u s of P o pu la tio n : 1970, Detailed Char

acteristics (G.P.O. PC(l)-48, 1972) .........—-......-...... 3f

U n it e d S tates D e p t , of C o m m er c e , B u rea u of t h e

C e n s u s , C e n s u s T racts, C e n s u s of P o pu la tio n and

H o u sin g , Richmond, V a. SMS A (G.P.O. PHC (1)-

173, 1972) ......................-.............................. 27n, 92n, 93n

U n it e d S ta tes D e p t , of C o m m er c e , B u rea u of t h e

C e n s u s , CENSUS OF POPULATION: 1970 (G.P.O.

PC(1)-B48, October, 1971) ................ -..................... 80n

U n it e d S ta tes D e p t , of C o m m er c e , B u rea u of t h e

C e n s u s , CENSUS OF POPULATION: 1970 (G.P.O.

PCH(2)-48, 1971) .................................... -................ •’In

U n it e d S ta tes D e p t , of C o m m er c e , B u rea u of t h e

C e n s u s , I CENSUS OF POPULATION: 1960

(G.P.O. 1961) ...................... ....................... -............. 80n

U n it e d S ta tes D e p t , of C o m m er c e , B u rea u of t h e

C e n s u s , I I C E N SU S OF P O P U L A T IO N : 1950

(G.P.O. 1952) ...... ............ ................... -........ -....... 3,On

I n t h e

gnjprm? (tart ni % Imtrin BtvlUb

O ctober T e r m , 1972

No. 72-550

C arolyn B radley , et al.,

vs.

Petitioners,

T h e S tate B oard oe E d ucation of t h e

C o m m o n w ea lth of V ir g in ia , et al.

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR T H E FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Opinions Below

The opinions of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit are reported at 462 F.2d 1058 and are reprinted

at pp. 557-602 of the Appendix to the Petition for Writ of

Certiorari filed by the School Board of the City of Rich

mond, Virginia, et al., in No. 72-549.1 The opinion of the

1 Citations in this brief in the form “A. ——” refer to the Joint

Appendix filed by Petitioners in this case and No. 72-549. Trial

exhibits are designated “PX” for plaintiffs’, “RX” for the Rich

mond School Board’s, “CX” for exhibits of the Chesterfield School

Board or Board of Supervisors, “HX” for exhibits of the Henrico

School Board or Supervisors, and “SX” for exhibits of the State

Board of Education and State Superintendent of Public Instruc

tion. In addition, citations to exhibits reprinted as part of the

Appendix in a separate volume are given in the form “Ex. A. —”.

Citations in the form “Pet. A —” refer to the separate Appendix

2

United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Virginia rendered on January 5, 1972 and its implementing

order entered January 10,1972 are reported at 338 F. Supp.

67 and are reprinted in the same Appendix at pp. 164-545.

Other opinions and orders of the courts below related to

this litigation are reported or reprinted as follows:

1. District Court opinion and order entered August 17,

1970, approving interim plan of desegregation for Bich-

mond, reported at 317 F. Supp. 555 and reprinted at Pet.

A. 1-47.

2. District Court opinion and order entered December

5, 1970, granting motion for joinder of additional parties

defendant and directing the filing of an amended complaint,

reported at 51 F.B.D. 139 and reprinted at Pet. A. 48-57.

3. District Court opinion of January 8, 1971 denying

motion to recuse, reported at 324 F. Supp. 439 and reprinted

at Pet. A. 58-90.

4. Unreported District Court order of January 8, 1971,

as entered nunc pro tunc January 13, 1971, on pre-trial

motions, reprinted at Pet. A. 91-93.

5. Unreported District Court order of January 13, 1971

on additional pre-trial motions, reprinted at Pet. A. 94-97.

6. District Court opinion of January 29, 1971, denying

motion to implement further desegregation at midyear and

continuing pendente lite construction injunction in effect,

reported at 324 F. Supp. 456.

of Opinions Below and relevant state statutes filed with the Peti

tion in No. 72-549. Citations to portions of the record not re

printed in the Joint Appendix are given by volume number and

page, e.g., “28 R. 713.” Transcripts of earlier hearings are cited

by date and page.

3

7. District Court opinion and order entered February

10,1971, declining to convene three-judge court, reported at

324 F. Supp. 396 and reprinted at Pet. A. 98-106.

8. District Court opinion and order entered February

10, 1971 denying motion to dismiss as to certain defendants

in their individual capacities, reported at 324 F. Supp. 401

and reprinted at Pet. A. 107-09.

9. District Court opinion and order entered April 5,

1971 approving further desegregation plan for Richmond

schools, reported at 325 F. Supp. 828 and reprinted at Pet.

A. 110-55.

10. Unreported District Court opinion and order entered

July 20, 1971 denying renewed motion to convene three-

judge court, reprinted at Pet. A. 156-62.

11. Unreported District Court order entered September

15, 1971 denying evidentiary motion, reprinted at Pet. A.

163.

12. Unreported District Court opinion and order issued

January 19, 1972 denying stay of January 10 order, re

printed at Pet. A. 546-52.

13. Court of Appeals order granting partial stay of

District Court decree, entered February 8, 1972, reported

at 456 F.2d 6 and reprinted at Pet. A. 553-56.

14. Amended judgment of the Court of Appeals, entered

August 14, 1972, reprinted at Pet. A. 603.

Other reported opinions in this case are as follows: 317

F.2d 429 (4th Cir. 1963); 345 F.2d 310 (4th Cir.), rev’d

382 U.S. 103 (1965).

4

Jurisdiction

The opinion of the Court of Appeals was entered June

5, 1972 and its amended judgment filed August 14, 1972.

On August 29, 1972, Mr. Justice Marshall extended the

time within which a Petition for a Writ of Certiorari might

be filed to and including October 5, 1972. The Petition

was filed on October 5 and was granted on January 15,

1973. On the same date, this case was consolidated with

No. 72-549 by order of the Court. The Court’s jurisdiction

rests upon 28 TT.S.C. §1254(1).

Q uestion Presented

Is the constitutional power of a federal court to remedy

racial discrimination in the public schools confined within

the geographic boundary lines of a single State-created

school district in the absence of a showing of racial motiva

tion in the drawing of the district lines ?

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

The case involves the application of the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States, which provides as follows:

. . . nor shall any State . . . deny to any person within

its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

This matter also involves the Tenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States, which reads as follows:

The powers not delegated to the United States by the

Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are

reserved to the States respectively or to the people.

5

Various provisions of Virginia’s Constitutions of 1902

and 1971 and Virginia statutes relating to education are

set out at Pet. A. 604-23. These are; Constitution of 1902,

§§ 129, 130,132,133 ; Constitution of 1971, Art. VIII, §§ 1-7;

Va. Code Anno. §§ 22-1, -2, -7, -30, -34, -100.1 through -100.12

(Eepl. 1969); Va. Code Anno. §§ 22-1.1, -2, -7, -21.2, -30,

-32, -100.1, -100.3 through -100.11, -126.1, -127 (Supp. 1972).

Statem ent

The basic issue in this case is whether the remedy pro

posed by the Richmond School Board and adopted by the

district court to end racially identifiable schools in the

greater Richmond area was beyond the power of the dis

trict court in view of its findings that the Richmond school

system, as well as the Henrico and Chesterfield County

school systems, were in violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment in 1970 (when the county school authorities were

joined as defendants) and at the time of final decision by

the district court. We begin by describing the extent and

the history of the public school segregation that the district

court undertook to remedy.

I. Segregation in th e Schools o f th e

G reate r R ichm ond A rea

In 1961, at the commencement of this litigation, the

schools administered by the Richmond, Chesterfield and

Henrico School Boards were completely segregated. A

decade later, the district court found that the same boards

were still operating non-unitary systems (338 F. Supp., at

103-04, 70-72, 78-79, 169-71, 174-76, Pet. A. 237-38, 165-69,

183-84, 383-86, 393-97) :

During the school year 1970-71 (when the Chesterfield

and Henrico boards were added as defendants [see pp. 38-

6

41 infra]), the School Board of the City of Richmond

administered 54 regular school facilities.2 Twelve schools

enrolled more than 70% white students, including six

schools which were more than 90% white (EX 30; 338 F.

Supp., at 232-33, Pet. A. 522-23). Four schools were at

tended solely by black students, an additional eight by

more than 95% black students, and another three by more

than 90% black students {ibid.). Thus, in a system of

47,988 pupils, 64.2% of whom were black (EX 75, Ex. A.

21; Pet. A. 417), nearly one-quarter of the schools were

more than 70% white (half of these more than 90% white)

and another quarter of the schools enrolled in excess of

90% black students.3

During the same 1970-71 school year, the Chesterfield

County School Board operated 39 schools, of which nine

teen were more than 90% white and one over 99% black

(PX 115; 338 F. Supp., at 234-36, Pet. A. 524-26). The

black school retained an all-black faculty while six other

Chesterfield County schools had no black faculty members,

and an additional nine schools had only one black faculty

2 Excluding programs and classes for handicapped, special edu

cation students, etc.

3 This was the result obtained from the implementation of a

partial plan of desegregation limited to the City schools pursuant

to an August 17, 1970 decree of the District Court (Pet. A. 1-47).

In comparison, during the 1969-70 school year, prior to the issu

ance ^of the first judicial decree in this lawsuit which required

the City School Board to assign students mandatorily to achieve

desegregation (see pp. 36-37 infra), the City Board operated

61 facilities: 22 were all-black and six others more than 90%

black; two were all-white and 17 more than 90% white- and

faculties were similarly segregated (RX 30; 338 F. Supp at 232-

33, 240-42, Pet. A. 522-23, 530-32, 6-7)

7

member (PX 102; 20 E, 132a-35, 338 F. Supp., at 170, 234-

36, Pet. A. 384, 524-26).4

Daring the 1970-71 school year, the Henrico County

School Board was responsible for the operation of 39

schools. Twenty-eight were more than 90% white but Cen

tral Gardens Elementary School was over 96% black, and

enrolled more than two-fifths of all black elementary stu

dents residing in the system (PX 116; 338 F. Supp., at 175,

237-39, Pet. A. 395, 527-29). Central Gardens had the

largest proportion of black faculty members of any facility

operated by Henrico, while ten schools had no blacks on

their faculties and another 20 had only one black staff

person (PX 116; 338 F. Supp., at 176, 237-39, Pet. A. 397,

527-29).6

To summarize, of 132 schools operated during the 1970-

71 year by the three local boards, 53 had student bodies

more than 90% white; 17 schools were more than 80%

black.6 All but three of the black schools were located

within the City of Richmond,7 and all but sis of the 90%-

4 During the 1968-69 school year, Chesterfield operated 9 all

black schools, and during the 1969-70 school year, 5 all-black or

virtually all-black facilities (PX 115; 338 F. Supp., at 234-36,

Pet. A. 524-26). The reduction in number was brought about by

closing the black schools as part of an HEW-approved plan (PX

118, pp. 214, 217-18).

5 Henrico in 1968-69 had 5 all-black or more-than-90%-black

schools (PX 116; 338 F. Supp., at 237-39, Pet. A. 527-29). Four

of these five schools were closed at the end of the 1968-69 school

year after HEW commenced enforcement proceedings, leaving

Central Gardens virtually all-black during the 1969-70 and 1970-

71 years {ibid,.; PX 120, pp. 318-19, 321-22).

6 The overall student population was 33.7% black, a change of

only one-tenth of one percent from the figure of the previous decade

(RX 78; Ex. A. 26; Pet. A. 418).

7 One black school was administered by the School Board of

Richmond but located in Henrico County; another black school

facility was located partly within Henrico County (338 F. Supp.,

8

white schools in the surrounding counties.8 Schools of

substantially differing racial composition were located

within reasonably short distances of each other (two to

five miles): in most instances, the boundary line between

the Richmond and county systems fell between them. The

following Table comparing the enrollments of neighboring-

Richmond and Henrico schools by race in 1970-71 is illus

trative :

TABLE I s

1970-71, and Distances Between Them

Richmond Henrico

Distance

(miles)

School % Black School % Black

Armstrong High 75% 5.0 Highland Springs High 13%

Kennedy High 93% 4.9 Henrico High 4%

John Marshall High 73% 1.4 Henrico High 4%

Mosby Middle 95% 3.6 Fairfield Jr. High 18%

East End Middle 68% 3.6 Fairfield Jr. High 18%

Fulton-Davis Elem. 53% 1.8 Montrose Elem. 0%

Mason Elem. 100% 3.1 Adams Elem. 14%

Highland Park Elem. 90% 1.3 Glen Lea Elem. 1%

Stuart Elem. 91% 2.2 Laburnum Elem. 20%

Because of the 1970 annexation of a portion of Chester

field County containing several white schools, the new Rich-

at, 172, Pet. A. 388; cf. 24 R. 69; PX 117, 338 F. Supp., at 164,

Pet. A. 371 [1954 request by Richmond Board for permission of

Chesterfield Supervisors to build white Richmond high school in

the county]; A. 581; PX 120; 338 F. Supp., at 172, Pet. A. 388

[1957 action of Henrico Board directing its Superintendent to

negotiate with Richmond to permit Henrico black students to

attend Richmond schools]).

_ 8 Approximately 85% of all black pupils in the area were as

signed to schools administered by the Richmond Board.

9 Derived from PX 97, 97A; see 338 F. Supp., at 190, Pet. A.

428-29; 23 R. 30-36.

9

mond-Chesterfield boundary line did not separate Richmond

and Chesterfield schools of markedly different racial com

position during the 1970-71 school year. However, the

previous boundary line fell between such schools. For

example, Richmond’s Franklin Elementary School (100%

black in 1969-70) is shown by the maps (RX 64, Ex. A. 27)

utilized by the Richmond School Board in presenting its

proposed plan (see pp. 46-48 infra) to have been within

three miles of the sites of Chesterfield County’s Green Ele

mentary School and Redd Elementary School (100% white

and 92% white, respectively, in 1969-70).

The decree proposed by the Richmond School Board and

approved by the district court to disestablish these segre

gated schools is described more fully below (see pp. 42-49

infra). It suffices here to note that that decree—whose law

fulness is the issue before this Court—sought to desegre

gate all of the schools, no matter which side of the boundary

lines they fell. The decision of the Court of Appeals re

versing that decree and restricting the desegregation proc

ess to the Richmond side of the boundary lines essentially

perpetuates the pre-1971 pattern of black Richmond schools

closely adjoining white county schools, as illustrated by

Table 2. Indeed, there would be an even greater number of

schools of substantially differing racial composition located

within short distances of one another, separated by the

Richmond boundary:

10

TABLE 2

Enrollments10 of Selected Schools Adjoining Each Other On

Either Side of Richmond Boundary

Richmond School County School

School % Black School % Black

Armstrong High 72% Highland Springs High 13%

Kennedy High 88% Henrico High 4%

John Marshall High 78% Henrico High 4%

Mosby Middle 86% Fairfield Jr. High 18%

East End Middle 66% Fairfield Jr. High 18%

Pulton Elementary 50% Montrose Elem. 0%

Mason Elementary 83% Adams Elem. 30%

Highland Park Elem. 84% Glen Lea Elem. 30%

Stuart Elem. 79% Laburnum Elem. 20%

Wythe High 57% Manchester High 5%

Elkhardt Middle 45% Providence Interm. 2%

Broad Rock Elem. 57% Falling Creek Elem. 0%

Oak Grove & Annex Elem. 42% Chalkley Elem. 5%

Southampton Elem. 68% Crestwood Elem. 1%

Fisher Elem. SRGOCO Bon Air Elem. 3%

10 The record contains 1971-72 enrollment data only for the

Richmond schools together with projected 1971-72 enrollments

for the schools paired with Central Gardens in Henrico County.

The figures listed for the other county facilities are those of the

1970-71 school year, the latest in the record. We believe the sig

nificance of the comparison for 1971-72 remains substantially accu

rate since neither county planned any change in method of pupil

assignment between 1970-71 and 1971-72 (with the exception of

the attempt to sever all formal ties between the Chesterfield County

School Board and the Matoaca Laboratory School [A. 1021-24]

and the Central Gardens pairing [RX 88; A. 961], the results

of which are reflected in the Table). We further note that the

same comparison was made by the Court of Appeals in con

nection with its conclusion that when the two steps referred to

parenthetically above were taken, each of the county systems

would be “unitary,” as the Court of Appeals used that term (462

F.2d, at 1065, Pet. A. 571-72).

11

The net result of the Court of Appeals’ ruling is that,

out of 131 schools which would now be operated by the three

local boards, 44 would be attended by more than 90% white

students, and 11 by more than 80% black students. All of

the black schools would be part of the Eichmond system,

and all of the white schools would be in the counties.

A. M aintenance and E xpansion o f the D ual School System s

1. D elays in Com pliance w ith B row n

The development of identifiable white schools and black

schools within the greater Eichmond area was not adven

titious. Prior to Brown v. Board of Education, 347 IT.S.

483 (1954), Virginia’s public schools vTere racially segre

gated by statute. Following Brown, none of the three

school boards in the Eichmond region made any move to

end their traditional segregatory practices until required

to do so by either judicial or administrative proceedings.11

In both Eichmond City and Chesterfield County, the first

modification of the pre-Brown form of dual system resulted

from federal judicial decrees requiring the local boards

and the State’s pupil placement agency (see p. 19 infra;

Appendix E infra) to allow certain individual black

pupils to transfer to white facilities from the black schools

to which they had been assigned. In Henrico, no desegre

gation occurred until after the passage of the 1964 Civil

Eights Act (PX 115, 116, 120; 338 F. Supp., at 173, Pet. A.

390-91 ;12 317 F.2d 429 [4th Cir. 1963] ; McLeod v. County

11 This is not surprising in light of the encouragement local

authorities were given by State officials to resist compliance with

the law (see p. 21 infra).

12 The ruling of the District Court (338 F. Supp., at 67-248,

Pet. A. 164-545) contains extensive detailed findings of fact (338

F. Supp., at 116-230, Pet. A. 185-532) including specific findings

as to matters about which there is little dispute, such as the time

when the first desegregation occurred. The District Court on

several occasions expressed its dismay that such factual matters

12

School Bd. of Chesterfield County, Civ. No. 3431 [E.D.

Va.]).

From 1954 to 1966, the Richmond School Board persisted

in maintaining all its policies and practices of the pre-

Brown era except insofar as judicial decrees required their

abandonment. White students and black students were

assigned to white schools and black schools, respectively,

without any change until 1961. At that time, pursuant to

a federal court decree, black children who complied with

pupil placement procedures were permitted to transfer to

white schools but initial assignments by the School Board

continued to be made on a segregated basis.

In 1966 the Richmond Board agreed to a consent decree

in this litigation which, while embodying a freedom-of-

choice plan of pupil assignment, also committed school

authorities to examine other methods of student assign

ment if significant desegregation did not occur. No such

action was ever taken. Yet in 1970, after a motion for

further relief had been filed, the School Board conceded

that its free choice plan did not meet constitutional re

quirements13 (338 F. Supp., at 70-72, Pet. A. 165-69). The

Board then embraced a plan based strictly on geographic

zoning, although aware of the drastic residential segrega

tion within the City of Richmond (338 F. Supp., at 74-75,

Pet. A. 173-76). Not until 1971-72 did the Richmond Board

propose a plan of mandatory, race-conscious pupil assign

ments to all Richmond schools for desegregation (338 F.

Supp,, at 78-79, Pet. A. 182-83; Pet. A. 119-27).

could not be stipulated (e.g., 25 R. 14, 62) but since they were

not, undertook to make the requisite specific findings. For this

reason, and given the enormity of the record and the necessity

to limit the Joint Appendix, insofar as possible, to manageable

dimensions, we shall from time to time refer the Court to the

lower court’s findings on factual matters rather than the record.

13 Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430 (1968).

13

Faculty and staff continued to be assigned to particular

schools on the basis of their race and that of the student

body (338 F. Supp., at 72, Pet. A. 168-69) ;14 affirmative

reassignments of faculty and staff in a manner designed to

eradicate the racial labelling of schools accomplished

through past practices did not commence until the 1970-71

school year.

The Richmond Board also promoted continuation of the

dual system through the rapid transformation of schools

from white to black. Prior to 1960, it had formally redesig

nated white schools as black. Thereafter, under its free

choice plan, it acquiesced in the wholesale transfer of re

maining whites away from schools of increasing black

concentration.15 School site locations continued to be

chosen so as conveniently to serve predominantly one-race

residential areas, or without consideration of the tendency

of the locations to perpetuate or aggravate school segre

gation in view of pre-existing residential segregation (338

F. Supp., at 75-76; Pet. A . 177; 324 F. Supp. 456, 461-69).

Next door in Chesterfield County, the county school

board and the Board of Supervisors had repeatedly memo

rialized their support of the various “massive resistance”

tactics (see pp. 18-21 infra) developed and implemented by

Virginia state officials to avoid school desegregation fol

lowing Brown (PX 117, pp. 82, 97; PX 118, pp. 76-79, 82;

338 F. Supp., at 167-68, Pet. A. 377-81). The School Board

14 This pattern continued even after this Court in this case held

the plaintiffs had standing to challenge continued racial faculty

assignments, Bradley v._ School Bd. of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103

(1965), and continued in substance even after the School Board

pledged in the 1966 consent decree, see p. 36 infra, that it would

take steps to desegregate faculties.

16 See Chart from Richmond School Board’s submission of

“HEW” plan in 1970; 317 P. Supp. 855, and relevant testimony

of Superintendent, 6/19/70 Tr. 248-53.

14

continued to refer to its schools as white schools and

“colored schools” (A. 528; PX 93,117; EX 92; 338 F. Supp.,

at 135-37, Pet. A. 307-12), and to assign faculties accord

ingly (see 338 F. Supp., at 234-36, Pet. A. 524-26).

Although a 1962 federal district court decree required

the Chesterfield Board and the Pupil Placement Board (see

p. 19 infra) to admit certain black pupils to the formerly

white facilities for which they had made application,16 the

Board took no steps of its own to bring about any desegre

gation until after the passage of the 1964 Civil Eights Act.17

It finally agreed in 1966 to adopt a freedom-of-choice pro

posal (PX 118; 338 F. Supp., at 168-69, Pet. A. 381)

after having first- sought to convince the Department of

Health, Education and Welfare that the Chesterfield schools

were in compliance with the Act because they were oper

ated pursuant to the 1962 decree (which applied to the

named plaintiffs only) {ibid.). That year the Board ad

ministered 47 schools, including an all-black secondary

school serving the entire county and eight all-black ele-

mentaries (PX 115; 338 F. Supp., at 234-36, Pet. A. 524-26).

These schools remained all-black while freedom-of-choice

was in effect {ibid.). All faculties were completely segre

gated except for one white teacher at a black school, and

one black teacher at a white school {ibid.).

In 1968, after having been advised by the Department of

HEW that the school system faced termination of federal

funding because of the failure of the free choice plan to

16 McLeod v. County School Bd. of Chesterfield County, Civ. No.

3431 (E.D. Va.).

17 There were no further proceedings in the McLeod ease after

the 1962 decree, which was not accepted by the Department of

Health, Education and Welfare as evidence of compliance with

the Act. See text infra. Accordingly, the Department undertook

Title VI enforcement.

15

bring about effective desegregation, the Chesterfield School

Board proposed closing eight of the nine all-black ele

mentary schools effective with either the 1968-69 or 1969-70

school year, and the establishment of geographic zones for

the formerly white facilities (PX 118, pp. 214, 217-18). The

ninth black elementary school was still all-black at the

time of the hearing below (PX 115; 338 F. Supp., at 236,

Pet. A. 526). While the faculties of the closed black schools

were generally absorbed within the system, most of the

principals were assigned to lesser positions at the white

schools (20 R. 85-89, 105-09). Extensive segregation in the

assignment of faculties is apparent through at least the

1969-70 school year (338 F. Supp,, at 234-36, Pet, A. 524-26;

PX 115).

A similar course of events occurred in Henrico County:

continuation of segregation policies after 1954 (e.g., PX

120, p. 141 [segregated faculty conferences]) together with

expressions of support for the State’s anti-desegregation

efforts (Id. at p. 89; PX 121, at p. 83). The first desegrega

tion in the county did not occur until after the passage of

the 1964 Civil Rights Act; then, from 1965-66 through

1968-69 the schools were operated under a freedom-of-

choice plan (PX 120, pp. 212, 218, 267, 285-89). Of 42

schools administered in 1966-67, four elementary schools

and a county-wide secondary school remained all-black.

Faculties were completely segregated. (338 F. Supp., at

237-39, Pet. A. 527-29). The Board of Supervisors denied

assertions by HEW that county black schools were inferior

facilities offering inadequate programs (PX 121, p. 15;

338 F. Supp., at 174, Pet. A. 392-93); but the School Board’s

response to the commencement of administrative proceed

ings to terminate federal funding to the county school

system in 1968 was to propose the closing of all of these

schools beginning in the 1969-70 school year, and the en-

16

largement of the zones for adjacent white facilities (PX

120, pp. 318-19, 321-22). The School Board did not pro

pose to desegregate Central Gardens Elementary School

although it was over 90% black (see 338 P. Supp., at 239,

Pet. A. 529).

As late as the 1970-71 school year, two-fifths of Henrico’s

black elementary school students were assigned to the

virtually all-black Central Gardens School, which also had

the greatest concentration of black faculty members

throughout the system (Ibid.; 23 E. 13). Indeed, while it

was continuing to operate its other black facilities as late

as the 1968-69 school year, the Board was increasing the

black faculty component at Central Gardens as the number

of black students increased (PX 116; 338 F. Supp., at 175,

238, Pet. A. 395, 529).

2. Perpetuation o f the D ual System T hrough School

Construction

The period since Brown has seen a steady increase in

pupil population in the three divisions; from 1961 to 1971

alone, the number of pupils in the greater Richmond area

increased by nearly 24,000 (EX 78, Ex. A. 26; 338 F.

Supp., at 185, Pet. A. 418). School construction programs

which responded to this growth extended and entrenched

segregation in the public schools.

Virtually none of the new facilities built in any of the

three school divisions since 1954 opened with any substan

tial degree of desegregation (HX 29; PX 116, 117; 338 F.

Supp., at 232-42, Pet. A. 522-32; Answers to Interroga

tories, 3 R. 653, 4 E. 10; 324 F. Supp., at 461-69). Indeed,

applications submitted to the State Department of Educa

tion for approval of construction projects long after 1954

continued to characterize proposed facilities as intended

for black or white students (EX 90, 92; PX 117, p. 133;

17

PX 118, pp. 107, 111-12, 116, 132, 137, 169; 338 F. Supp.,

at 127-38, Pet A. 289-313). No consideration was given,

in the process of site selection, to the effect of placing new

schools in residentially segregated settings. School con

struction and expansion in Henrico, for example, was re

peatedly premised upon Negro population increases in

specific areas of the county (EX 90; see 29 E. 167-80).

And none of the new Chesterfield school construction in

the planning stages at the time of trial in 1971 had been

developed with any consideration of its effects upon de

segregation (A. 494).

Virginia state officials’ role in school construction was

direct. Their approval of sites and building plans was

required before bonds could be sold, state construction aid

funds released, or facilities erected (21 E. 82, 89-92; PX

117, PX 122, pp. 63, 115-19, 158 ; EX 83, p. 26; 338 F. Supp.,

at 124-26, Pet. A. 283-86). The responsible state officials

published a planning handbook designating criteria to be

used by local administrators in evaluating plans for addi

tional construction. But they did not require that the

impact of proposed new construction in perpetuating segre

gation or retarding desegregation be considered.18 While

the State Superintendent did notify local officials of a

1968 judicial decision requiring that school planning take

account of the effects of new locations upon desegregation,19

that consideration was never incorporated into the State’s

evaluation process (A. 513-14), and the current planning

handbook makes no mention of it (SX 4, § 10.31).

18 Not only did the handbook contain no such requirement, but

in actual practice the State officials were as derelict as local ad

ministrators in assessing impact on segregation. E.g., RX 90; 338

F. Supp., at 130, Pet. A. 295-96).

19 United States v. Board of Public Instruction of Polk County

395 F.2d 66 (5th Cir. 1968).

18

3. T he R ole o f the State

Segregatory institutions and policies dating from the

era prior to 1954 continued to be supported by State au

thorities long after this Court’s decision in Brown. Black

regional schools created and maintained with the assistance

of the State Board of Education (PX 122, pp. 70a-71; 338

F. Supp., at 155-57, Pet. A. 352-56) remained in operation

as late as 1968. No action was taken by State authorities

either to desegregate or to close them (21 B. 132); indeed,

the State Board approved expansion of one such facility

in 1955 (PX 119, p. 44; PX 122; 338 F. Supp., at 157, Pet.

A. 355). The State Education Department continued to

hold its statewide conferences on a segregated basis until

1965 (PX 122, pp. 230, 237, 240, 251, 267, 280-81; A. 535).

Prior to the passage of the Civil Eights Act of 1964, the

State Board of Education (which had responded to Brown

by officially opposing it and endorsing “massive resistance”

devices under legislative consideration at the time (PX

119, pp. 42-43; 338 F. Supp., at 139, Pet. A. 316)), desig

nated no Education Department staff personnel to work

with local divisions to accomplish integration because, as

an Assistant State Superintendent agreed, in the 1950’s

Virginia was not desegregating its schools (A. 679-80).

And, as noted above, assessment of school construction

proposals for their impact upon desegregation has never

been made a part of the State’s review procedures.

The State intervened directly to maintain segregation,

however. Immediately after the Brown decision, the State

Board and Superintendent directed local districts to op

erate as they had, until Virginia’s school segregation laws

were changed (PX 122, pp. 161-64; PX 119, pp. 42-43; EX

82, 83; A. 525-27, 533-35). They never were.

Instead, the 1956 Virginia Legislature enacted a series

of measures designed to prevent school desegregation. It

19

began with an interposition resolution20 attempting to

nullify Brown, It authorized the Governor to close any

school which became integrated,21 whether by local initiative

or federal court order.22 It. withdrew pupil assignment

power from the local school division Boards23 and vested

all authority over assignments in a newly created inde

pendent agency known as the State Pupil Placement

Board24 in order to preserve segregation25 (PX 122, p.

171). The Board continued to function until 1968 (23 R.

20 Va. Acts 1956, S.J.R. 3, p. 1213, 1 Race Rel. L. Rep. 445.

21 Va. Acts 1956, Ex. Sess., eh. 68, p. 69; 1 Race Rel. L. Rep.

1103. See PX 144-1; 338 F. Supp,, at 243-44, Pet. A. 533-36.

22 Exercising this authority in 1958, the Governor ordered the

State Police to prevent the enrollment of seventeen Negro students

in six formerly white Norfolk schools (PX 144, p. 122; 338 F.

Supp., at 140, Pet. A. 318).

23 A December 29, 1956 telegram from the Pupil Placement

Board to then Chesterfield County Superintendent of Schools Fred

D. Thompson began:

Under the provisions of Chapter 70, Acts of Assembly, extra

session of 1956, effective December 29, 1956, the power of

enrollment or placement of pupils in all public schools of

Virginia is vested in the Pupil Placement Board. The local

school board, Division Superintendents, are divested of all

such powers.

(A. 521-22; PX 122, p, 91).

24 The State Department of Education undertook to publicize

the regulations and procedures of the Pupil Placement Board (PX

122, p. 171; A. 522-24) and one of its employees also served the

Placement Board on a part-time basis (A. 693).

25 See PX 144-F; 338 F. Supp., at 138, Pet. A. 313-14 [letter

from Attorney General] ; Adkins v. School Bd. of Newport News,

148 F. Supp. 430 (E.D. Va.), aff’d 246 F.2d 325' (4th Cir.), cert,

denied, 355 U.S. 855 (1957). Compare the Attorney General’s

reference to a “state-wide policy” with the following passage from

the Brief for Appellees in No. 3, Davis v. County School Bd., O.T.

1954, at p. 15:

In general, education in Virginia has operated in the past

pursuant to a single plan centrally controlled with regard to

the segregation of the races.

20

58-59; 338 F. Supp., at 138, Pet. A. 313) ;26 but, following

invalidation of the Governor’s school-closing powers by

the Virginia courts in 1959,27 the Legislature vested those

same powers in the local school boards.28

The 1956 legislature also passed tuition grant legislation

(338 F. Supp., at 141, Pet. A. 321). In 1958 the State

Board of Education adopted regulations for the distribu

tion of tuition grants, specifying their availability to pupils

desiring to avoid attending desegregated public schools

operated by the division of their residence (PX 122, pp.

181, 188; PX 119, p. 74; 338 F. Supp., at 141-42, Pet. A.

321-22). The program was expanded by enactment in 1960

of a pupil scholarship statute making grants available to

attend nonpublic schools (PX 122, p. 210; 338 F. Supp.,

at 142-43, Pet. A. 323-25), and providing that the cost

would be shared by the State and the local division. The

act called for deduction of a local division’s share of grants

from State aid funds otherwise due it, if it refused to

participate in the scholarship programs and thereby forced

the State to make the full payment to individual parents

(PX 122, pp. 213-17, 225-26).

26 In 1960 the General Assembly authorized local divisions to

resume making pupil assignments in accordance with criteria to

be promulgated by the State Board of Education. Va. Code Anno.

§§ 22-232.18 to -.31. The following year, the State Board adopted

regulations virtually identical to those of the Pupil Placement

Board (PX 122, p. 218; A. 523-24).

27 In Harrison v. Day, 200 Va. 439, 106 S.E.2d 636 (1959), the

Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia held the statute uncon

stitutional under the Virginia Constitution insofar as it authorized

a State officer to discontinue local schooling over the objections

of a division board.

28 Va. Acts 1959, Ex. Sess., eh. 32, p. 110. The Virginia courts

subsequently upheld the power of a division board to close all of

its schools rather than desegregate them. School Board of Prince

Edward County v. Griffin, 204 Va. 650, 133 S.E.2d 565 (1963).

Compare James v. Almond, 170 P. Supp. 331 (E.D. Va.), app.

dism’d, 359 U.S. 1006 (1959); Griffin v. County School Board, 377

U.S. 218 (1964).

21

Meanwhile, the State made the services of its legal

officers available to divisions resisting school desegregation

efforts, and shared in the cost of retaining private counsel

to fight desegregation suits. This financial support of

segregation continued through the date of the District

Court’s decision below (PX 122, pp. 287-88, 304; PX 149,

149A, 149B, 149D, 149E; 338 F. Supp., at 155, Pet. A. 351).

The State Department of Education circulated the anti

desegregation speeches of Virginia Governors (PX 122,

p. 327; EX 83, pp. 38-41; 338 F. Supp., at 148, Pet. A. 336),

but not information about the decisions of this Court which

successively spelled out the scope of the constitutional duty

to desegregate (A. 717-20; 338 F. Supp., at 155, Pet. A.

350). It supported continuing segregation in many ways:

for example, by assisting Henrico to redraw segregated

pupil transportation routes in 1957 (PX 120, pp. 102-38)

and by making retroactive tuition grants to Prince Edward

County whites in 1964 (PX 119, pp. 87-88; 338 F. Supp., at

143-44, Pet. A. 326).

Passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and execution

of a compliance agreement between the United States De

partment of Health, Education and Welfare and the State

Department of Education brought little change. Not only

did the State fail to take affirmative action to facilitate

desegregation, but it threw roadblocks in the way of HEW

enforcement.29 The tuition grant and pupil scholarship

programs continued (PX 112). No sanctions were brought

to bear at the State level against divisions which refused

29 In 1971 the State Board of Education still denied it had an

affirmative duty to assist in the creation of unitary systems through

out the Commonwealth (A. 95, 113 [ffll]) . Compare PX 96, Ex.

A. 75, wherein the Assistant Attorney General of the United

States expressed the view to State Superintendent Wilkerson that

“the State Board of Education is the appropriate agency to be

called upon to adjust the conditions of unlawful segregation and

racial discrimination existing in the public school systems of

Virginia . . . . ”

22

to cooperate with HEW (A. 684-88, 700-01). The only

official within the State Education Department with re

sponsibility for desegregation efforts was critical of HEW

(PX 136; 338 F. Supp., at 148, Pet. A. 336-37) and sought

to have the Department make HEW’s job as difficult as

possible (PX 123; EX 87; PX 136A; A. 681-84; 338 F.

Supp., at 152-53, Pet. A. 344-36). Despite the State’s assur

ance in its agreement with HEW that it would secure and

facilitate local school-division compliance with non-discrim

ination requirements (SX 7), it left matters entirely up

to division officials (PX 144-G; 338 F. Supp., at 149, Pet.

A. 337-38). And the State stood by while the ranks of

black principals and teachers were decimated in the process

of such desegregation as occurred at all (PX 139; A. 930-

31; 338 F. Supp., at 155, Pet. A. 351-52).

4. Crossing D ivision Lines fo r Segregation

Of particular significance to this case are the many

instances in which black and white students were assigned

across school division lines to maintain school segregation.

Three regional high schools for Negro students established

with State approval and support30 continued to operate a

decade after Brown (PX 109; EX 86, Ex. A. 79).31 Such

30 For example, in 1946 the State Board of Education contributed

$75,000 toward the cost of building the Carver High School to serve

Negro students from Orange, Madison, Greene, Rappahannock, and

Culpeper Counties (RX 82, p. 2; 338 F. Supp., at 155-56, Pet.

A. 352).

31 Carver (see n. 30 supra), Manassas (serving Prince William,

Fairfax, Fauquier Counties), Christiansburg Institute (serving

Montgomery County, Pulaski County, and Radford City). A fourth

regional high school, Jackson P. Burley (serving Charlottesville

and Albemarle County) operated until the 1959-60 school year

(A. 510, PX 109; RX 86, Ex. A. 79). Many other joint schools for

black students were countenanced in Virginia, including those oper

ated by the Lancaster and Northumberland County divisions, and

the Rockbridge and Lexington divisions (see 338 F. Supp., at 155-57,

Pet. A. 352-56). See A. 508-09.

23

facilities were jointly administered by up to five school

divisions, which sent all of their black students to the

school. Often, travel distances were great:32 in several

instances, black students had to be housed in dormitories

during the week to avoid inordinate daily transportation

(PX 119, pp. 15, 19, 23; PX 122, pp. 70a-71; 338 F. Supp.,

at 157, Pet. A. 356). Where school divisions did not con

struct regional facilities, they often sent Negro pupils to

classes in other districts by contractual agreement (PX 94,

pp. 4, 7-8, 20, 30-31, 34-35, 39-41, 45, 49, 50, 57, 60; 338 F.

Supp., at 159-61, Pet. A. 360-64).33 This practice continued,

in some instances, until 1969—and even involved the trans

portation of blacks to West Virginia or Tennessee districts

to preserve segregation (ibid.).

Large numbers of individual student transfers across

school division boundaries to attend segregated facilities

resulted from the tuition grant and pupil scholarship pro

grams (see p. 20 supra).34 For example, within a few

months after the Norfolk schools were closed,36 nearly

6,500 grant applications had been approved to permit Nor

folk students to attend South Norfolk and other school

systems (PX 119, pp. 60-65; 338 F. Supp., at 142, Pet A.

323). The funds were used to permit students to attend

out-of-State schools as well (PX 110, 111). From 1954 to

32 The Carver High School, for example, served five counties and

a total area of 1338 square miles. See A. 508-10.

33 The district court’s opinion details numerous examples from the

exhibits in the case at 338 F. Supp. 159-61, Pet. A. 360-64.

84 The 1960 statute contained a declaration of legislative purpose

stating that

it is desirable and in the public interest that scholarships

should be provided from the public funds of the State for

the education of the children in non-sectarian private schools

in or outside, and in public schools located outside, the locality

where the children reside. (A. 938).

35 See note 22 supra and accompanying text.

24

1971, almost $25 million in State and local funds were ex

pended under the grant and scholarship programs (PX

112; 338 F. Supp., at 145, Pet A. 329); substantial amounts

were paid to Eichmond, Henrico and Chesterfield students

(PX 101, 112, 117, 118, 120; 338 F. Supp., at 145, Pet A.

329-30).

Pupils have crossed lines to attend segregated schools

through a variety of other means. For example, as previ

ously noted,36 a black Eichmond high school is located

within Henrico County, and a black elementary school

partly within the county. As the result of annexations,

numbers of students have temporarily attended classes in

school divisions in which they did not reside, on a segre

gated basis. The 1970 annexation decree, for example, pro

vided that some Chesterfield residents would attend schools

now located within the Eichmond system during a transi

tional period. As long as those schools remained identi-

fiably white, no difficulty ensued; but after Eichmond im

plemented its interim plan of desegregation37 for the 1970-

71 school year, the County Superintendent publicly invited

county residents attending Eichmond schools to return and

enroll in county schools (A. 485-90).

B. The M etropo litan C on text

We have several times spoken in this Brief of the

“greater Eichmond area.” We now summarize the evi

dence which supports that characterization and describes

the two principal relevant features of the Eichmond-

Chesterfield-Henrico complex: (1) intense and increasing

cohesion as a single, functioning economic and social com

munity, marked, however, by (2) intense and increasing

differentials in racial concentration as between the City

and its two surrounding counties.

36 See note 7 supra.

37 See note 4 supra; pp. 36-37 infra.

25

1. U nity o f the M etropolitan Area

The City of .Richmond, encompassing approximately

sixty-three square miles, lies nearly at the geographic

center of the area made up by the Counties of Henrico

(244 square miles) and Chesterfield (445 square miles),

which surround the City on all sides. Other counties to

the north and south of Henrico and Chesterfield, respec

tively, are separated from this greater Richmond region

in whole or in part by the Appomattox and Chicahominy

Rivers (see maps at Ex. A. 27-31).38 Virtually all of Hen

rico and most of Chesterfield County39 lie within thirty

minutes’ travel of Capitol Square in Richmond, using

regular streets and averaging twenty to forty miles per

hour (A. 154-56; RX 60, Ex. A. 13; HX 36-A).

The two counties and Richmond are highly interrelated

and mutually dependent. As is typical of most urban

areas,40 the central core city has ceased to register in

creases in population in the decennial censuses; the major

population growth from 1950 to 1960 occurred in Henrico

County, and in 1960 to 1970 in Chesterfield County (A. 156-

57; PX 17, Plates 8, 10-11, 15; RX 46; CX 21; HX 24). The

most densely populated areas of each county are contiguous

to Richmond (PX 17, Plates 17-24; HX 38, 38-A; see also,

38 The entire area was originally a part of Henrico (A. 798);

Richmond and Chesterfield County, among other political entities,

were created from it. Subsequently, the city annexed various

portions of each county (HX 5; CX 2).

39 This includes all of the areas which, under the plan approved

by the district court (see pp. 46-49 infra), would send any students

to a school or schools presently located within the boundaries

of the City of Richmond (see A. 236; RX 95). Although parts

of Chesterfield County are also within thirty minutes’ travel

time of other Virginia municipalities (CX 20), there was no

showing of the same degree of mutual interdependence that exists

between the county and Richmond.

40 See discussion at pp. 55-60 of the Petition for Writ of

Certiorari in this matter.

26

PX 17, Plates 42-44). The 1970 Census reveals a total

population of 480,840: 249,430 in Richmond, 154,364 in

Henrico and 77,046 in Chesterfield.41

A variety of historical, economic and social indicators

demonstrates the close functional unity of the region de

spite its division into three independent political entities.

For example, evidence introduced at the trial indicates that

prior to the 1970 annexation,42 over three-quarters of the

jobs in the region (78% of those covered by Virginia’s

unemployment compensation program) were in Richmond

(RX 55, Ex. A. 3) and that half or more of the residents

of each county worked in Richmond (A. 160-61).48 1970

Census data44 confirms the continuation of these patterns.45

41 See table at p. 30 infra.

42 Effective January 1, 1970, Richmond annexed an area of

Chesterfield County containing 47,262 persons, 97% white. See

Holt v. City of Richmond, 459 F.2d 1093 (4th Cir. 1972).

,43 The evidence introduced below was prepared in connection

with annexation proceedings against Henrico and Chesterfield

Counties in 1964 and 1969, respectively, and showed that in 1962,

66% of Henrico residents, and in 1968, 48% of Chesterfield resi

dents were employed in Richmond (RX 56, 56A, Ex. A. 5-6). It

was also shown that 90% of all attorneys listed in the 1970

Greater Richmond Telephone Directory” had their offices within

the city, and of those, 51.4% lived in Richmond, 42% in either of

the two counties, and 6.6% elsewhere (A. 161) ; and that approxi

mately one-third of the State Education Department employees

in 1971 lived in each of the three political entities (ibid.).

44 Statistics compiled from the 1970 United States Census were

not available to the parties or the district court at the time of trial

(see A. 160). Throughout this Brief, we shall refer to the latest

figures available from judicially noticeable sources because they

update those available at the time of trial and have the added

virtue that they were compiled following the 1970 annexation of a

portion of Chesterfield County by the City of Richmond (note 42

supra; see 3,38 F. Supp., at 180-82, Pet. A. 406-10).

45 According to the 1970 Census, 48% of Chesterfield workers

are employed in Richmond, 30% in Chesterfield and 6% in Henrico;

65% of Henrico residents work in Richmond, 27% in Henrico and

27

Similarly, pre-annexation Eiclimoncl accounted for 62%

of the region’s retail sales (A. 163; RX 54, 54A, Ex. A. 1-2)

and later figures demonstrate its continued preponderance

as the commercial and mercantile center of the area.46

The daily newspapers of general circulation throughout

the area are in Richmond (A. 775-76),47 as are most local

television and radio stations and a disproportionate num

ber of public and private educational and cultural facilities:

3% in Chesterfield. United States D ept , op Commerce, B ureau

op th e Census, Census Tracts, Census op P opulation and H ous

ing , Richmond, Va. SMSA (G.P.O. PHC(1)-173, 1972), p. 11,

Table P-2, Social Characteristics of the Population: 1970. (These

figures omit workers whose place of work is unreported). Analyses

performed for a Richmond Regional Transportation Study pro

jected that the City would retain a similar proportion of metro

politan employment in the future (A. 160, 163; RX 54, 55, Ex.

A. 1-4).

46 Richmond is responsible for $698,123,000 (72%) in retail

trade as compared to $89,226,000 in Chesterfield and $186,021,000

in Henrico. Richmond’s preponderance is still greater in regard

to “shopping goods”—those purchased from department and ap

parel stores and thus comprising routine consumer items. Rich

mond accounts for $213,671,000 of such purchases, five times the

amount of Henrico’s $39,253,000 and almost seventeen times Ches

terfield’s $12,704,000. R and, McNally & Co., [1972] Commercial

A tlas & Marketing Guide 76. Compare 338 P. Supp., at 178, 182,

Pet. A. 402, 411.

47 Newspapers are a good index of the independent identity of

subparts of a region, because they are relatively inexpensive to

establish (less expensive, for example, than television stations—all

six of which in the Richmond SMSA are located in Richmond

City), and are directly responsive to the demand of the ̂ local

populace for news about their neighbors, about local political issues,

and about the doings in the community as that is perceived by

its inhabitants. Henrico County apparently has no newspapers;

Chesterfield has only one: a weekly published in Chester, which

is a town of about 5,500 residents. The Richmond newspapers

therefore serve the counties. There are an estimated 83,100 house

holds in Richmond City, and 74,200 in the counties, op. tit. supra,

at 76 n. 77; Richmond’s morning Times-Dispatch has a daily circu

lation of 140,618 and a Sunday circulation of 193,540, Richmond’s

evening News-Leader a circulation of 118,410. [1972] Ayer D irec

tory op P ublications 1084, 1122.

28

for example, six of seven, institutions of higher learning,

including a medical college (A. 164), and the major li

braries and museums of the area (A. 164; EX 59, Ex. A.

9-11). Health services for the entire area are concen

trated in Richmond (which includes within its boundaries

17 of the community’s 18 hospitals (A. 165)); most resi

dents of the region are born in and die within Richmond.48

Such public transportation as is available in each of the

counties is almost exclusively directed toward travel be

tween suburb and city rather than within each county

(see A. 885-86).

While the subdivision of the region among three politi

cal units naturally creates a competitive spirit in various

affairs, there has been a great deal of concerted action for

mutual benefit. Henrico County offices are located in Rich

mond, and its employees there depend upon the City’s police

and fire services (A. 805-06). Parts of the county’s territory

have in the past received fire protection from Richmond

pursuant to agreement, and there is presently a reciprocal

fire assistance pact between Richmond and Chesterfield