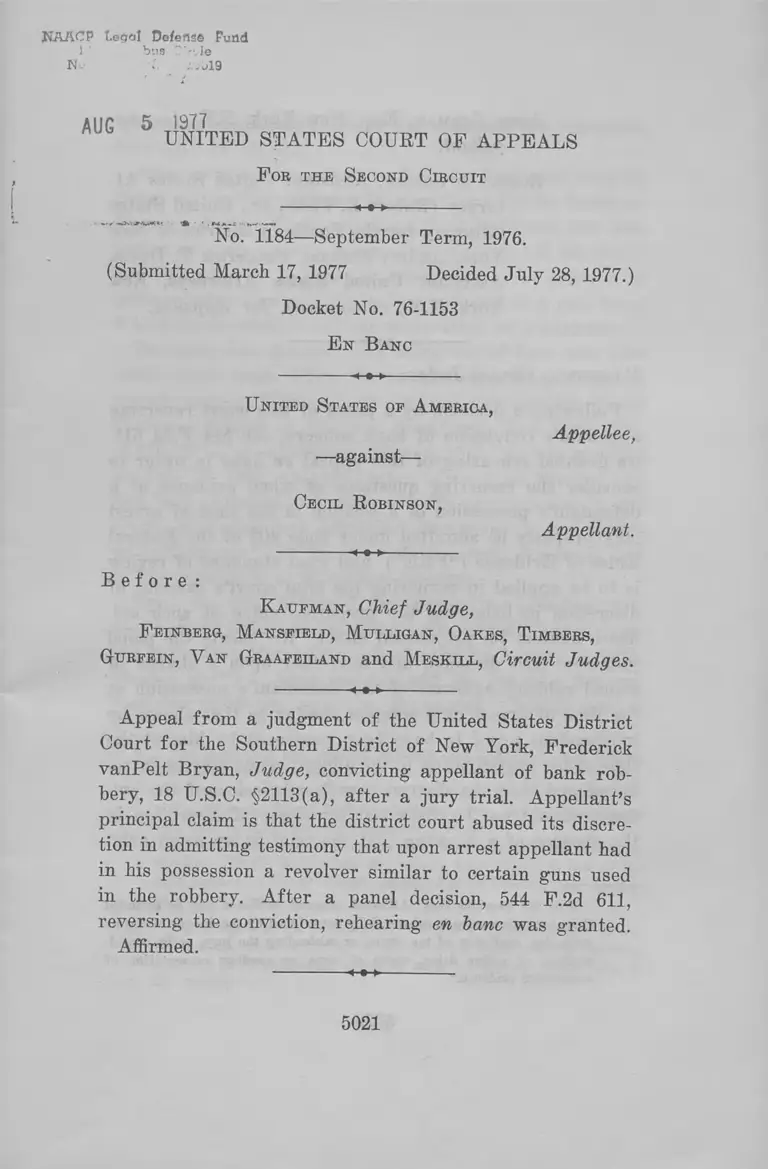

United States v. Robinson Opinion

Public Court Documents

March 17, 1977 - July 28, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Robinson Opinion, 1977. 636774c4-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4de4dd10-1b46-4540-9a17-135d1aa1337c/united-states-v-robinson-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

UAACP Defense Fund

! ' bus

N- ..019

AUG 5 1977

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F or the Second Circuit

-----------------------------< -e -> -----------------------------

No. 1184—September Term, 1976.

(Submitted March 17, 1977 Decided July 28, 1977.)

Docket No. 76-1153

E n B a n c

United S tates op A merica,

•— against—

Appellee,

Cecil R obinson,

Appellant.

B e f o r e :

K aufman , Chief Judge,

F einberg, Mansfield, M ulligan, Oakes, T imbers,

Gurfein, V an Graafeiland and M eskill, Circuit Judges.

Appeal from a judgment of the United States District

Court for the Southern District of New York, Frederick

vanPelt Bryan, Judge, convicting appellant of bank rob

bery, 18 U.S.C. §2113(a), after a jury trial. Appellant’s

principal claim is that the district court abused its discre

tion in admitting testimony that upon arrest appellant had

in his possession a revolver similar to certain guns used

in the robbery. After a panel decision, 544 F.2d 611,

reversing the conviction, rehearing en lane was granted.

Affirmed.

5021

Jesse Berman, Esq., New York, N.Y., for Ap

pellant.

R obert J. J ossen, Assistant United States At

torney (Robert B. Fiske, Jr., United States

Attorney for the Southern District of New

York, Audrey Strauss, Frederick T. Davis,

Assistant United States Attorneys, New

York, N.Y., of counsel), for Appellee.

M a n s f i e l d , Circuit Judge:

Following a decision by a panel of this court reversing

appellant’s conviction of bank robbery, see 544 F.2d 611,

we granted rehearing of this appeal en banc in order to

consider the recurring questions of when evidence of a

defendant’s possession of a weapon at the time of arrest

may properly be admitted under Rule 403 of the Federal

Rules of Evidence (“FRE” )1 and what standard of review

is to be applied in reviewing the trial court’s exercise of

discretion in balancing the probative value of such evi

dence against its prejudicial effect. We vacate the panel

judgment and decision, and hold that upon a charge of

armed robbery evidence of the defendant’s possession at

the time of arrest of a weapon similar to that shown by

independent proof to have been possessed by him at the

time of his participation in the alleged crime may be intro

duced and that the district court’s admission of the evi

dence should not be disturbed for abuse of discretion in

the absence of a showing that the trial judge acted arbi-

1 Rule 403 provides that "Although relevant, evidence may be excluded

i f its probative value is substantially outweighed by the danger of unfair

prejudice, confusion of the issues, or misleading the jury, or by consid

erations of undue delay, waste of time, or needless presentation of

cumulative evidence.”

5022

trarily or irrationally. Under this standard the conviction

here must he affirmed.

After trial before a jury and Judge Frederick vanPelt

Bryan of the United States District Court for the Southern

District of New York, appellant Cecil Robinson was con

victed of bank robbery in violation of 18 U.S.C. §2113(a)2

and sentenced to 12 years imprisonment. An earlier trial

before Judge Kevin T. Duffy had resulted in a jury hung

8 to 4 for conviction and the declaration of a mistrial.

Robinson was charged with being one of four men (the

other three were Allen Simon, Edward Garris, and a

person named “Karim” ) who robbed the Bankers Trust

Company branch at 177 East Broadway, New York City,

of $10,122 on the morning of May 16,1975. He was arrested

on July 25, 1975, 10 weeks later, after Allen Simon, who

had been arrested and charged with participation in the

crime, confessed and identified Robinson as one of his

co-participants.3 At the time of his arrest Robinson had

in his possession a .38 caliber revolver.

Upon the trial before Judge Bryan the principal wit

ness against Robinson was Simon, who admitted participat

ing in the May 16 robbery and who had on August 19, 1975,

pleaded guilty to bank robbery and the use of a firearm,

receiving an 18-year sentence. He agreed to testify against

2 The indictment also charged Bobinson and a fugitive co-defendant,

Edward Garris, with conspiracy to commit bank robbery, 18 U.S.C. $371,

and armed bank robbery, 18 U.S.C. $2113(d ). Upon Bobinson’s con

viction o f bank robbery, 18 U.S.C. $2113(a), these other charges against

him were dismissed with the government's consent.

The indictment against Bobinson and Garris superseded an earlier in

dictment (75 Cr. 635) which also named Allen Simon as one o f the

bank robbers. A fourth alleged participant in the robbery, one "Karim,"

has not been indicted.

3 The evidence at the trial showed that Simon named Bobinson as one

o f the conspirators on the day of his arrest and again when he identified

Bobinson as a participant shown in bank surveillance photographs of

the robbery.

5023

Robinson in return for government aid in gaining a re

duction in his sentence, which was subsequently reduced

to 10 years.

Simon testified that he and Robinson (known as “Merci

ful” ) along with Edward Garris (known as “A.E.” ) and

a person named “Karim,” planned and carried out the

robbery. According to Simon, Robinson selected a Bankers

Trust branch located two blocks away from the Gouverneur

Hospital, where Robinson worked as a laboratory tech

nician, as the bank to be robbed. Robinson also introduced

“Karim,” who was to drive the getaway car, to Garris and

Simon, and suggested that he and “Karim” wear white

jackets during the robbery in order to blend in with the

hospital employees who frequented the bank. In addition,

Robinson offered to obtain a getaway car. Simon also

testified that on the night before the robbery the conspira

tors assembled four guns to be used in carrying out the

crime: one shotgun, one .32 caliber hand gun, one .38 cal

iber revolver, and one revolver that “looked like it might

have been a .38.” The guns were hidden in a vacant apart

ment and picked up by the conspirators later that night

for use in the robbery. During the robbery Simon used

the shotgun and “Karim” used the .32 caliber revolver,

which he accidentally discharged, wounding a teller. Im

mediately after the robbery, Robinson passed his gun to

Garris in the back seat of the getaway car.

The government also introduced proof that Robinson’s

fingerprint had been found on the right rear cigarette panel

of the red 1974 Pontiac used as the getaway car, which

was abandoned 20 minutes after the robbery. The Pon

tiac’s owner was identified as Otis Brown, a friend of

Robinson and a fellow student at Bronx Community Col

lege, which Robinson attended on a part-time basis. Pull-

face bank surveillance photographs taken during the com

mission of the crime revealed a man wearing a hat and

5024

a white hospital-type jacket, who appears to have facial

features quite similar to those of Robinson and to be

scooping money into a paper bag. It was also established

that Robinson had failed to appear for work as scheduled

at the hospital on the day of the robbery. Two Human Re

sources Administration employees testified that Robinson

was a long standing acquaintance of Garris, the fourth

robber.

After the foregoing evidence (except for the testimony

of the Human Resources Administration employees), in

cluding proof of the guns used in the robbery, had been

introduced, Judge Bryan admitted testimony by FBI agents

that, when arrested on July 25, 1975, Robinson had a .38

caliber revolver in his possession. The court refused to

permit the gun itself to be put in evidence or shown to

the jury, and carefully instructed the jury that this evi

dence was received solely on the issue of Robinson’s iden

tity as one of the robbers.4 At the first trial Judge Duffy

had excluded similar evidence but did not have before him

the proof of the assembling and calibers of the guns used

in the robbery (including the use of a .38 caliber and one

4 Judge Bryan’s charge on the evidentiary value of the gun was as

follows:

"In certain instances evidence may he admitted for a particular,

limited purpose only. Now, you have heard testimony about a .38

calibre hand gun which was found when the defendant was arrested

on these charges, some two months after the robbery. That testi

mony was admitted for a very limited purpose. It may be con

sidered only for whatever value, if any, it has on the issue of

defendant’s identity as one of the robbers, that is, on the question

of whether this defendant was the person who committed the crimes

charged. You may not draw any conclusions or inferences or engage

in any speculation as to the defendant’s character or reputation

on the basis of this testimony or about anything else other than

the narrow thing that I have just mentioned to you. You may

consider this evidence solely for the limited purpose I have described

and give it such weight, i f any, for that purpose as you think it

may deserve.”

5025

that “looked like” a .38 caliber), which was introduced at

the second trial.

The only evidence offered by Robinson m his defense

was the testimony of several employees of the bank that

the photo-spreads they were shown by the FBI prior to

Simon’s arrest did not include Robinson’s photograph.

None of the bank witnesses was asked by the government

or the defense whether they could identify Robinson as

one of the robbers or as the robber wearing the white

jacket and hat in the bank surveillance photos. However,

those bank witnesses who were called testified that they

would not be able to identify the robber shown in the

surveillance photos as wearing the hat and white jacket

because they did not concentrate on him or get a good

look since their attention was diverted by the shooting of

one of the tellers and because they were concentrating on

the robber who held the shotgun. The trial judge excluded

the government’s proffer of testimony by persons who had

seen Robinson on numerous occasions to the effect that

the robber shown in the bank surveillance photographs as

wearing a hat was Robinson.

After hearing all the evidence and Judge Bryan’s charge,

the jury deliberated for about five hours,5 after which in

a note to the court it reported itself deadlocked “ 11-1 for

conviction on Count Two [bank robbery].” After advising

counsel of the note, but not of the precise division of the

jury, Judge Bryan delivered a modified Allen charge,6 see

5 This was the estimate of defense counsel.

6 "The Court: Well, ladies and gentlemen, this case has been tried

for quite a number of days before the Court here, and it is eminently

desirable that you reach an agreement on a verdict in this case, if

you possibly can.

"The case is an important one for the parties. It involved a

great amount of time and effort on the part of both the parties,

5026

Allen v. United States, 164 U.S. 492, 501-02 (1896). After

three more hours, one juror in a note to the court sought

advice on the ground that “ regardless of honest efforts

of my co-jurors to persuade me, I am unable to reach a

decision without a strong reasonable doubt.” After sealing

the note, Judge Bryan informed counsel of its existence.

Both sides agreed that jury deliberations should continue

but, since it was after 6:30 P.M., the jury was sent home

for the night.

the time of the Court and the time of you citizens who are serving

on the jury.

"Now, if you fail to agree on a verdict, the case is going to

have to be tried, I expect, before another jury, and I see no reason

to suppose that another jury would be more competent to determine

the issues here than you ladies and gentlemen are.

"As I say, it is wholly desirable and it is your duty to reach

a verdict here if you possibly can. Of course, by pointing out the

desirability of your reaching a verdict here and your duty to do

so if you possibly can, I am not suggesting that any of you should

surrender a conscientious conviction as to where the truth lies here

or as to the weight and effect of all the evidence.

"However, while each of you must decide the question for him

self or herself and not merely acquiesce in the conclusions o f your

fellow jurors, I think you ought to examine the issues here with

candor and frankness and with proper deference and regard for

the opinions of one another.

" I will put it to you this way:

"You should examine the questions submitted to you with candor

— and I am repeating— and with a proper regard and deference

for the opinions of each other. You should listen to each others’

views with a disposition to be convinced.

"Now, that does not mean that you should give up any conscien

tious views that you hold, but it is your duty, after full deliberation

here, to agree, if you can do so, without violating your individual

conscience and judgment.

"So I am going to ask you to go back— I know how tedious these

things are, but I am going to ask you to go back at this thing

and work at it again in the spirit and atmosphere that I have

suggested to you. It is important that a decision, a verdict be

reached here, and I really see no good reason why a decision can

not be reached, bearing in mind what I have said and my cautions

to you.

"Please, now, go back and try once more.”

5027

At 10:00 A.M. the following morning, as part of his

opening remarks, Judge Bryan delivered a short modified

Allen-type charge, stating that

“the only response that I can give to that note is to

state again for you some of what I stated yesterday

afternoon, that is, you should examine the questions

submitted to you with candor and with a proper regard

for and deference to the opinions of one another;

you should listen to one anothers’ views with a dis

position to be convinced.

“That does not mean that you should give up any

conscientious views that you hold, but it is your duty

after full deliberation, to agree upon a verdict, if you

can do so without violating your individual judgment

and your individual conscience.”

At 2 :45 P.M. the jury reached a verdict finding Robinson

guilty of Count Two of the indictment. The government

did not oppose dismissal of the other counts.

Appellant’s principal contentions on appeal are that the

district judge erred in admitting testimony concerning

the gun found in Robinson’s possession at the time of the

arrest and in sealing the juror’s note and giving a second

AWeM-type charge.

D is c u s s io n

The principal issue at trial, as happens so often in bank

robbery cases, was the identification of appellant as one

of the bank robbers. As the panel majority conceded, see

544 F.2d at 615, the proof that upon arrest he had had a

.38 caliber revolver in his possession was “relevant” to

5028

that issue, as the term is defined in FRE 401.7 As evi

dence linking him to the crime, it tended to make his par

ticipation in the robbery “more probable . . . than it would

be without the evidence,” id. According to Simon, whose

testimony must be accepted as credible for present pur

poses, Robinson, within minutes after the robbery and as

the robbers were speeding away in the getaway car, handed

over a gun to Garris, one of the robbers. Since four guns

had been assembled by the four robbers for use in the rob

bery (a shotgun, a .32 caliber gun, a .38 caliber gun, and

a gun that “ looked like” a .38 caliber) and during the

robbery Simon carried the shotgun while Garris held the

.32 caliber gun, the gun in Robinson’s possession was by

the process of elimination either the .38 caliber or the gun

that “ looked like” a .38 caliber. The remarkable co

incidence that he possessed a .38 caliber gun some weeks

later thus tended directly to identify appellant as one of

the participants, corroborating Simon’s testimony.8 As we

7 FEE 401 defines "relevant evidence” as follows:

" 'Eelevant evidence’ means evidence having any tendency to make

the existence of any fact that is o f consequences to the determina

tion o f the action more probable or less probable than it would be

without the evidence.”

8 Our dissenting colleague, Judge Oakes, repeatedly states, without any

record or judicially noticeable support, that "hundreds of thousands of

persons . . . possess the same caliber gun” as the .38 caliber hand gun

used in the crime according to Simon's testimony and found on Eobinson

at the time of arrest, which is characterized by the dissent as 'undis-

tinetive,’ 'common’ and ’unremarkable.’ In a similar vein Judge Oakes

states that we do not dispute his earlier panel majority opinion charac

terizing the .38 caliber gun evidence as 'very weak’ for the purpose of

establishing appellant’s identity.

Our views on these matters are best summarized by reiterating with

approval the following statement from the earlier panel dissent:

"While hand guns may be all too plentiful in our society, the ma

jority would imply that they are as common as subway tokens. In

fact, the vast majority of people do not possess a hand gun, much

less one of .38 caliber. To find such a gun in the possession of

the very person against whom there is independent proof that he

5029

said in United States v. Ravich, 421 F.2d 1196, 1204 (2d

Cir. 1970) :

“Nevertheless, a jury could infer from the posses

sion of a large number of guns at the date of arrest

that at least some of them had been possessed for a

substantial period of time, and therefore that the de

fendants had possessed guns on and before the date

of the robbery. See United States v. Consolidated

Laundries Corp., 291 F.2d 563, 569 (2 Cir. 1961), and

2 Wigmore, Evidence §437(1) (3d ed. 1940).”

See also United States v. McKinley, 485 F.2d 1059, 1060

(D.C. Cir. 1973) (sawed-off shotgun similar to that used

in crim e); United States v. Cunningham, 423 F.2d 1269,

1276 (4th Cir. 1970) (similarity of weapons); Walker v.

United States, 490 F.2d 683, 684 (8th Cir. 1974) (evidence

of similar weapon “has been regularly admitted as rel

evant” ).

Regardless of the relevance of the evidence as cor

roborating Simon’s testimony, Robinson’s possession of the

gun was also admissible under FRE 404* 9 on the indepen

dent ground that it tended to show he had the “ oppor

tunity” to commit the hank robbery, since he had access to

an instrument similar to that used to commit it. This

ground was recognized by us in United States v. Ravich,

used a .38 caliber hand gun in the bank robbery is sufficiently co

incidental to be extraordinary. I cannot agree with the majority

that this evidence 'established only a very weak inference that ap

pellant was one of the bank robbers.’ ” United States v. Robinson,

544 F.2d 611, 622 (2d Cir. 1976).

9 FRE 404(b) provides in pertinent part:

” (b ) . . . Evidence o f other crimes, wrongs, or acts is not ad

missible to prove the character of a person in order to show that

he acted in conformity therewith. It may, however, be admissible

for other purposes, such as proof o f motive, opportunity, intent,

preparation, plan, knowledge, identity, or absence of mistake or

accident.” (Emphasis added).

5030

421 F.2d 1196 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 400 U.S. 834 (1970),

where we upheld the admission of the defendant’s pos

session upon arrest of guns and ammunition other than

those used in the alleged hank robbery.

“Direct evidence of such possession would have been

relevant to establish opportunity or preparation to

commit the crime charged and thus would have tended

to prove the identity of the robbers, the only real issue

in this trial.” 421 F.2d at 1204.

See also United States v. Wiener, 534 F.2d 15 (2d Cir.

1976), cert, denied, ------ U.S. ------ (1977) (loaded gun

found with narcotics in burlap hag in apartment of de

fendant charged with narcotics law violations admitted “ as

tools of the trade” ) ; United States v. Campanile, 516 F.2d

288 (2d Cir. 1975) (admission of Luger handgun seized

upon search upheld); United States v. Walters, 477 F.2d

386, 388-89 (9th Cir.), cert, denied, 414 U.S. 1007 (1973);

United States v. McKinley, 485 F.2d 1059 (D.C. Cir. 1975);

Walker v. United States, 490 F.2d 683 (8th Cir. 1974).

The proof of Robinson’s possession of the .38 caliber

gun at the time of arrest, while relevant on two separate

grounds, also posed the “ danger of unfair prejudice” with

in the meaning of FRE 403, which provides that “ [A]l-

though relevant, evidence may be excluded if its probative

value is substantially outweighed by the danger of unfair

prejudice . . . .” The Advisory Committee Notes define

“unfair prejudice” as “an undue tendency to suggest de

cision on an improper basis, commonly, though not neces

sarily, an emotional one.” Evidence that a defendant had

a gun in his possession at the time of arrest could in some

circumstances lead a juror to conclude that the defendant

should he punished for possession of the gun rather than

because he was guilty of the substantive offense, 1 Wig-

5031

more on Evidence §57 (3d ed. 1940). Absent counterbal

ancing probative value, evidence having a strong emo

tional or inflammatory impact, such as a “bloody shirt” or

“dying accusation of poisoning,” see United States v.

Leonard, 524 F.2d 1076, 1091 (2d Cir. 1975), cert, denied,

425 U.S. 958 (1976), may pose a risk of unfair prejudice

because it “ tends to distract” the jury from the issues in

the case and “permits the trier of fact to reward the good

man and to punish the bad man because of their respective

characters despite what the evidence in the case shows

actually happened.” Advisory Committee Notes, FRE 404,

quoting with approval the California Law Revision Com

mission. The effect in such a case might be to arouse the

jury’s passions to a point where they would act irrationally

in reaching a verdict.

The duty of weighing the probative value of the gun-

at-arrest evidence against its prejudicial effect rested

squarely on the shoulders of the experienced trial judge.

To determine whether he committed error requiring re

versal by admitting proof of appellant’s possession of the

.38 caliber gun upon arrest, we must first consider what

standard of review should be applied. We have repeatedly

recognized that the trial judge’s discretion in performing

this balancing function is wide. See, e.g., United States v.

Ravich, supra, where we upheld the admission of six guns

seized from the defendants at the time of arrest, stating:

“The trial judge must weigh the probative value of the

evidence against its tendency to create unfair prej

udice and his determination will rarely be disturbed

on appeal. Cotton v. United States, 361 F.2d 673, 676

(8 Cir. 1966); Wangrow v. United States, 399 F.2d

106, 115 (8 Cir.), cert, denied, 393 U.S. 933, 89 S.Ct.

292, 21 L.Ed.2d 270 (1968).

* * * * #

5032

“Notwithstanding the relevance of the guns and the

ammunition, the trial judge would have been justified

in excluding them if he decided that their probative

value was outweighed by their tendency to confuse

the issues or inflame the jury. He might -well have

done so in this case, in view of the overwhelming ev

idence that the defendants were the robbers, the rather

small addition which the guns provided, and the un

doubted effect on the jury of seeing all this hardware

on the table. However, the trial judge has wide dis

cretion in this area, see United States v. Montalvo,

supra, 271 F.2d at 927, and we do not find that it was

abused here.” 421 F.2d at 1204-05.

See in accord United States v. Dwyer, 539 F.2d 924 (2d

Cir. 1976); United States v. Leonard, supra; United States

v. Cheung Kin Ping, Dkt. No. 76-1362, Slip Opin. 2071 (2d

Cir. Feb. 28, 1977).

Broad discretion must be accorded to the trial judge in

such matters for the reason that he is in a superior posi

tion to evaluate the impact of the evidence, since he sees

the witnesses, defendant, jurors, and counsel, and their

mannerisms and reactions. See United States v. Leonard,

supra, 524 F.2d at 1094. He is therefore able, on the basis

of personal observation, to evaluate the impressions made

by witnesses, whereas we must deal with the cold record.

For instance, on the vital issue of identification of the de

fendant, Judge Bryan, based on his own personal observa

tion of the accused and comparison with bank surveillance

photos, could form a clearer impression than that which

we might gain from only a comparison of photographs.

Though we may strive most diligently and with all of our

accumulated experience to obtain from the black and white

of transcripts before us a perspective equivalent to that

of the experienced and able district court judge who tried

5033

this case, unless complete videotaped trial records become

available, see United States v. Weiss, 491 F.2d 460, n.2 (2d

Cir.), cert, denied, 419 U.S. 833 (1974), we simply cannot

successfully put ourselves in his position. Specifically, we

cannot weigh on appeal, as he could at trial, the intonation

and demeanor of the witnesses preceding the testimony in

issue, particularly the strength of Simon’s testimony, nor

can we determine the emotional reaction of the jury to

other pieces of evidence such as the surveillance photo

graphs, or judge the success of impeachment by cross-

examination through observation of the jurors. As Pro

fessor Maurice Rosenberg has cogently observed:

“ The final reason—and probably the most pointed and

helpful one—for bestowing discretion on the trial

judge as to many matters is, paradoxically, the su

periority of his nether position. It is not that he

knows more than his loftier brothers; rather he sees

more and senses more. In the dialogue between the

appellate judges and the trial judge, the former often

seem to be saying: ‘You were there. We do not think

we would have done what you did, but we were not

present and may be unaware of significant matters,

for the record does not adequately convey to us all

that went on at the trial.’ ” Rosenberg, Judicial Dis

cretion Viewed From Above, 22 Syracuse L. Rev. 635,

663 (1971).

For these reasons we are persuaded that the preferable

rule is to uphold the trial judge’s exercise of discretion

unless he acts arbitrarily or irrationally. See United States

v. McWilliams, 163 F.2d 695, 697 (D.C. Cir. 1947). We

thus adhere to the traditional formulation of the abuse of

discretion standard, which is based on the premise that

“the Court of Appeals should not and will not substitute

its judgment for that of the trial court "Atchison, Topeka

5034

and Santa Fe Rwy. v. Barret, 246 F.2d 846, 849 (9th Cir.

1957).10 In a different context Judge Waterman, in Napo-

litano v. Compania Sud Americana de Vapores, 421 F.2d

382, 384 (2d Cir. 1970), expressed the general philosophy

of this broad grant of discretionary power as follows:

“Had any one of us been in a position to exercise the

discretion committed to a trial judge . . . we would

have no hesitancy in stating that the decision would

have been otherwise; but as appellate judges we can

not find that the action of the district judge was so

unreasonable as to amount to a prejudicial abuse of

the discretion necessary to repose in trial judges dur

ing the conduct of a trial.”

Similar views were expressed by Judge Adams of the Third

Circuit:

“The task of assessing potential prejudice is one for

which the trial judge, considering his familiarity with

the full array of evidence in a case, is particularly

suited. . . . The practical problems inherent in this

balancing of intangibles—of probative worth against

the danger of prejudice or confusion—call for a gen

erous measure of discretion in the trial judge. Were

we sitting as a trial judge in this case, we might well

have concluded that the potentially prejudicial nature

of the evidence . . . outweighed its probative worth.

However, we cannot say that the trial judge abused

his discretion in reaching the contrary conclusion.”

10 United States v. Ortiz, Dkt. No. 76-1460, Slip Opin. 2789, 2800-03

(2d Cir. April 11, 1977), which is repeatedly referred to by Judge Oakes

in his dissent, involved the wholly unrelated issue of whether a witness'

prior narcotics convictions have any probative value for impeachment

purposes. Aside from its irrelevancy, we there upheld the trial judge’s

exercise of discretion in ruling that the convictions were admissible under

Eule 609(a) of the Federal Eules of Evidence, which is consistent with

the majority opinion here.

5035

Construction Ltd. v. Brooks-Skinner Building Co., 488

F.2d 427, 431 (3d Cir. 1973).

Applying the arbitrary-irrational standard for abuse of

discretion to the present case, Judge Bryan’s ruling clearly

must be upheld. He carefully considered arguments of

counsel and weighed the competing interests before admit

ting the evidence of Robinson’s possession of the .38 cali

ber gun upon arrest. In line with suggestions made by us

in United States v. Leonard, supra■, at 1092, be delayed its

admission until virtually all of the other proof bad been

introduced, by which time be was in a better position to

weigh the probative worth of the evidence against its

prejudicial effect. Although there were competing consid

erations, it was neither unreasonable nor arbitrary to con

clude that a sound basis existed for a probative inference

to be drawn from the evidence which outweighed its prej

udicial effect. He was, moreover, in a position to appraise

Simon’s testimony and the other incriminating evidence

against Robinson, including his fingerprints in the getaway

car, his similarity in appearance before the court to that

of the white-jacketed robber wearing a hat shown in the

surveillance photos, his absence from his job at the Gouver-

neur Hospital on the day of the robbery, and his prior

acquaintanceship with Karim and Brown, the owner of the

stolen car used for the getaway.11 In addition, Judge Bryan

XI Appellant also argues that the ease against him was close and that

because of this "closeness” the evidence of his possession of the .38

caliber handgun upon arrest should have been excluded as too prejudicial

since it may have tipped the scales against him. To the extent that

appellant relied upon the 8 to 4 deadlock at the first trial, which led

to a mistrial, the argument ignores the additional incriminating evidence

adduced at the second trial (including the calibers of the guns used

in committing the robbery and the proof of prior close acquaintanceship

between Simon, Garris and Robinson). Moreover, appellant confuses

the factors to be considered by the court in the weighing process, which

5036

took positive steps to minimize the potential impact of the

evidence by precluding the government from introducing

the gun itself or any ammunition* 12 and hy carefully in

structing the jury that the testimony in question was in

troduced for a limited purpose only.13 Under these cir

cumstances Judge Bryan did not abuse his discretion in

concluding that the balance weighed in favor of admitting

the evidence.14

Appellant next contends that the court committed re

versible error in sealing the contents of the note received

from one juror on the second day of deliberations, advis

are (1) the probative value of the proffered evidence, and (2) whether

the evidence, either inherently or when considered with other proof, would

so inflame the jury that it might act irrationally.

Although it has often been suggested that where the other evidence

o f guilt is overwhelming the jury may have less need to consider evi

dence of a prejudicial nature, even though relevant, see, e.g., United

States v. Ravioli, supra; United States v. Leonard, supra, the "close

ness” of the case is irrelevant to this weighing process.

12 In this respect the potential for prejudice fell far short of that pre

sented in United States v. Ravich, supra, where a small arsenal of

weaponry seized from the defendants upon arrest was introduced as

real evidence and lay in full view o f the jury on the courtroom table

and was available for examination by it, or United States v. Wiener,

supra, where the loaded gun found by police at the time of the defen

dant’s arrest was displayed to the jury.

13 The Advisory Committee Notes to Rule 403 state that "in reaching

a decision whether to exclude on the grounds o f unfair prejudice, con

sideration should be given to the probable effectiveness or lack o f effec

tiveness of a limiting instruction.”

14 Nor do we find it necessary to determine whether Judge Bryan applied

the correct standard in performing his weighing function. Two standards

have been suggested. Judge Weinstein advocates that the "better ap

proach” is to "give the evidence its maximum reasonable probative force

and its minimum reasonable prejudicial value.” Weinstein's Evidence

11403 [03] (1975). On the other hand, Professor Dolan, in Rule 40S:

The Prejudice Rule in Evidence, 49 So. Cal. L. Rev. 220, 233 (1976),

suggests that courts should "resolve all doubts concerning the balance

between probative value and prejudice in favor of prejudice.” Judge

Bryan’s ruling would satisfy either standard.

5037

ing the court that she had “a strong, reasonable doubt”

and in giving a second Allen-type charge. The Sixth

Amendment and Rule 43 of the Federal Rules of Crimi

nal Procedure require that ordinarily a message from the

jury be answered in open court and that counsel be given

the opportunity to be heard before the trial judge responds

to the jury’s questions. Rogers v. United States, 422 U.S.

35, 39 (1975). Here appellant does not claim a violation

of his right to be present at every stage of the trial. How

ever, he does contend that Judge Bryan should not have

sealed the note, arguing that if its contents had been known

his counsel would not have consented to the second Allen-

type charge or might have proposed other charges.

Ordinarily the better procedure is for the trial judge to

disclose the contents of a juror’s note to the parties. How

ever, the failure to do so here was hardly prejudicial error.

Since the court Avas already aware that the jury stood 11-1

for conviction and no new questions of law were raised by

the note, there was little or no need for Judge Bryan to

consult with counsel concerning his response. Moreover,

disclosure of the lone hold-out juror’s name to counsel

might, if this became known to her, embarrass her and

have the contrary effect of leading her to yield rather than

adhere to her views. In addition, appellant’s counsel at

no time sought to have the note unsealed. Nor did he sug

gest that Judge Bryan charge the jury in any other

manner.

The propriety of an Allen-type charge depends on

Avhether it tends to coerce undecided jurors into reaching

a verdict by abandoning without reason conscientiously

held doubts. See United States v. Green, 523 F.2d 229, 236

(2d Cir. 1975). In United States v. Hynes, 424 F.2d 754,

757 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 399 U.S. 933 (1970), we held

that proper Allen-type charges amount to

5038

“no more than a restatement of the precepts which the

trial judge almost invariably gives to guide the jurors’

deliberations in his original charge. Its function is to

emphasize that a verdict is in the best interests of

both prosecution and defense, and we adhere to the

view that ‘ [t]he considerable costs in money and time

to both sides if a retrial is necessary certainly justify

an instruction to the jury that if it is possible for

them to reach a unanimous verdict without any juror

yielding a conscientious conviction . . . they should

do so. United States v. Rao, 394 F.2d 354, 355 (2d

Cir. 1968).”

As Judge Oakes stated in United States v. Bermudez, 526

F.2d 89,100 (2d Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 425 U.S. 970 (1976),

such a charge is “permissible” when it provides “ encour

agement to the jurors to pursue their deliberations toward

a verdict, if possible, in order to avoid the expense and

delay of a new trial.” No fixed period of time must nec

essarily elapse before the charge may properly he given.

Moreover, the charge is “acceptable not only when the

jury has informed the judge that it cannot agree . . . but

also when [as in the present case] the judge has learned

that the jury was deadlocked 11 to 1 in favor of convic

tion. . . .” United States v. Martinez, 446 F.2d 118, 119-20

(2d Cir. 1971). As Judge Moore stated in United States

v. Meyers, 410 F.2d 693, 697 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S.

944 (1971), where the jury also had advised the trial judge

it was deadlocked 11 to 1:

“The judge’s warning that ‘under no circumstances must

any juror yield his conscientious judgment’ makes the

use of the Allen charge proper and not coercive, United

States v. Kenner, 354 F.2d 780 (2d Cir. 1965), cert,

den. 383 U.S. 958 (1966). The fact that the judge

knew that there was a lone dissenter does not make

5039

the charge coercive inasmuch as the nature of the

deadlock was disclosed to the Court voluntarily and

without solicitation. See Bowen v. United States, 153

F.2d 747 (8th Cir. 1946). To hold otherwise would un

necessarily prohibit the use of the Allen charge. . . . ”

See also United States v. Jennings, 471 F.2d 1310, 1313-14

(2d Cir.), cert, denied, 411 U.S. 935 (1973) (where jury

advised that it stood 11 to 1 for conviction).

Although the chances of coercion may increase with each

successive appeal by the court to the jurors to try to reach

a verdict, we are unwilling to hold that a second A Mew-type

charge is error per se. Rather, we believe that an individu

alized determination of coercion is required. Applying that

principle here, Judge Bryan’s second charge was far short

of being coercive. Its brevity and failure to mention any

“need” to reach a verdict, while studiously emphasizing

the “duty” to adhere to “ individual judgment” and “ in

dividual conscience,” reduced any potential for coercion

to the point where the charge might even had been con

strued as encouraging the dissenter not to abandon her

views. Finally, the fact that the jury deliberated for three

hours between the AMew-type charges and for more than

four hours after the second such charge before reaching

its verdict are strong indications that the effect of the

charge was minimal. We therefore hold that the trial court

did not abuse its discretion.16

Finally, we find no merit in appellant’s claim that the

government violated Brady v. Maryland, 373 IT.S. 83

(1963), by failing to disclose that Simon, who testified he

did not “know” Otis Brown, the owner of the getaway

car, had once been introduced to him as “Hakim” by Rob

inson. Since this information was already known to Robin-

15 Nor can we accept Judge Oakes' characterization of our opinion as

not disputing his view that "the second charge was not necessary.”

5040

son, who introduced the two, disclosure was not required

under Brady, United States v. Steivart, 513 F.2d 957, 960

(2d Cir. 1975), and cases cited therein. Second, the ev

idence was of minimal relevance or materiality on the

issue of possible access to Brown’s automobile since there

was no evidence that Simon knew that Brown owned a

car, much less the getaway car. See Moore v. Illinois, 408

U.S. 786, 794-97 (1972). Finally, since the exact informa

tion under consideration here was read to the jury by

stipulation of counsel during deliberations,16 it tended in

such a context to fully counteract the arguments that had

been made by the government in summation.

The conviction is affirmed.

O a k e s , Circuit Judge with whom Judge Gurfein concurs

(dissenting):

The panel majority opinion sets forth Judge Gurfein’s

and my views on the principal issues in this case. 544

F.2d 611 (2d Cir. 1976). I stated there that the case was

“exceedingly close” on its facts. Id. at 616. Without ev

idence that Robinson was in possession of a gun at the

time of his arrest (because the trial judge in the exercise

of his discretion excluded it), there was a hung jury in

the first trial. With such evidence (admitted by another

trial judge in the exercise of his discretion), it still took 16

16 "There is one other matter I want to call to your attention.

"Counsel have stipulated that i f Mr. Simon were recalled to the

stand, he would testify that in late 1974 he was once introduced

to Otis Brown by Robinson on the ground floor o f Harlem Hospital.

Simon was introduced as Arova, and the name 'Simon’ was not

mentioned. Edward Gams was present at that introduction but

was not introduced.

"Simon would also testify that he saw Brown from a distance

at Harlem Hospital on a subsequent occasion.”

5041

a second Allen charge and further deliberation to move

the second jury to vote for conviction. One is led to infer

that the testimony as to possession of the gun made a

crucial difference (despite limiting instructions). Since I

believe that admission of the gun evidence constituted

reversible error, I dissent.

As will be seen, this case turns to a large extent on its

facts, which the en banc majority views differently from

the panel majority. Because this case, insofar as it relates

to the exercise of trial court discretion, must be resolved

on its facts, and because, as would be expected, the en banc

majority opinion establishes no new principles of law in

the process, a disinterested observer might inquire as to

purpose of en banc treatment. Obviously the court must

either have a new, more liberal test for what is to be

reheard en banc or a great deal of free time to engage in

this type of exercise. But see Gilliard v. Oswald No. 76-

2109, slip op. 4227 (2d Cir. June 17, 1977) (denial of rehear

ing en banc in prisoners’ rights case). Of course, I recog

nize that the court does make new— and I think bad—law

in its disposition of the double Allen charge point, see

Part IV infra, but that point was not the basis of the

petition for rehearing en banc or its grant.

L

Review of Trial Court Discretion

The en banc majority opinion cites many authorities,

from this circuit and others, for the unexceptionable propo

sition that we should not substitute our judgment for that

of the trial judge on matters within his discretion, par

ticularly matters dependent on personal observation at

5042

trial. This proposition by repetition hardly takes on new

meaning. If the nse of the words “arbitrary or irrational”

is designed somehow to change this circuit’s standard for

review of trial court discretion, the majority opinion does

not say so. The rule in this circuit, restated not long ago

in the context of the provision here involved, Fed. E. Evid.

403, is that “great discretion in the trial judge . . . does

not mean immunity from accountability.” United States

v. Dwyer, 539 F.2d 924, 928 (2d Cir. 1976). See also

Michelson v. United States, 335 U.S. 469, 480 (1948)

(“ [w]ide discretion is accompanied by heavy responsibility

on trial courts” ) ; Rosenberg, Judicial Discretion of the

Trial Court, Vieived From Above, 22 Syracuse L. Rev. 635,

665-66 (1971).

Recognizing this rule, we held under Fed. R. Evid. 403

that a trial judge’s “wide discretion” in the “balancing of

probative value against unfair prejudice” had been abused

in a particular factual context, United States v. Divyer,

supra, 539 F.2d at 927-28, without making any claim that

the trial judge had acted irrationally. Nor did the author

of the en banc majority opinion make any such claim in his

recent opinion arguing that a specific weighing of pro

bative value and prejudice amounted to an abuse of dis

cretion. United States v. Ortiz, No. 76-1460, slip op. 2789,

2800-03 (2d Cir. Apr. 11, 1977) (dissenting opinion). See

also Contemporary Mission, Inc. v. Famous Music Corp.,

No. 76-7403, slip op. 3591, 3609-10 (2d Cir. May 18, 1977) ;

Marx & Co. v. The Diners’ Club, Inc., No. 76-7050, slip op.

2013, 2024-26 & nn.18-19 (2d Cir. Feb. 25, 1977). For the

balance of this discussion I will assume that the standard

established by these cases and others and not departed

from in the majority opinion is the proper one for review

ing the exercise of trial court discretion here.

5043

Relevance, Probative Value and Prejudicial Impact

Before the balancing1 process mandated by Fed. R. Evid.

403 can begin, the court must determine that the evidence

in issue is “ relevant,” as that term is defined in Rule 401.

The relevancy test of Rule 401 is an extremely modest one,

so that the en banc majority’s assertion of a “concession”

of relevancy by the panel majority, ante,------F.2d a t ------- ,

provides no help at all in resolving this case. Since the

bank robbers here carried guns, evidence of appellant’s

later possession of a gun does meet the rule’s test of having

“any tendency” to make appellant’s participation in the

robbery “more probable,” but so would evidence of, e.g.,

appellant’s sex (assuming identification of the sex of the

robbers), despite the fact that millions of others share that

characteristic. Relevancy under Rule 401 is nothing more

than a threshold test, a starting point in the determina

tion of admissibility.1

Once evidence is deemed relevant, the trial court must

then weigh carefully its probative value against the danger

of unfair prejudice that evidence creates. The probative

value of evidence cannot, of course, be assessed in a

vacuum; the value must always be measured in terms of

the purpose for which the evidence was introduced. See

Dolan, Rule 403: The Prejudice Rule in Evidence, 49 S.

Cal. L. Rev. 220, 233 (1976). In this case, as Judge Bryan’s

charge to the jury makes clear, see ante,------ F.2d a t -------

II.

1 Relevancy in the sense used in Fed. It. Evid. 401 was frequently

called, in pre-Federal Rules days, "logical relevancy,” which was then

contrasted with "legal relevancy,” a term referring to the balancing

process now incorporated in Fed. R. Evid. 403. See, e.g., Cotton v.

United States, 361 F.2d 673, 676 (8th Cir. 1966); Hoag v. Wright, 34

App. Div. 260, 266, 54 N.Y.S. 658, 662 (1898). See generally Mc

Cormick’s Handbook o f the Law o f Evidence § 185 (2d ed. E. Cleary

1972).

5044

n.4, the evidence was admitted “ solely for the limited

purpose” of establishing “ defendant’s identity as one of

the robbers.” The en banc majority offers two indirect

ways in which the gun evidence might have helped to estab

lish appellant’s identity, neither of which was mentioned

by the trial court. The majority contends that the evidence

helped to corroborate Simon’s testimony and that it was

relevant to appellant’s “opportunity” to commit the crime

charged. Significantly, the majority does not discuss the

degree of probative value of the gun evidence for either of

these purposes, nor does it discuss whether the evidence

provided any genuine direct proof of appellant’s identity,

pursuant to the trial court’s charge.

The majority opinion first states that the gun evidence

“tended directly to identify appellant as one of the par

ticipants, corroborating Simon’s testimony.” Ante, ------

F.2d a t ------ . The majority does not explain how corrob

oration of an accomplice’s testimony can amount to “di

rect” identification of a defendant from his later possession

of a gun. Such corroboration at best is an indirect form

of identification, but even for this corroborative purpose

the evidence here lacked probative value. Once Simon had

decided to link appellant to the robbery,2 it stands to

2 Early in his interrogation by the Federal Bureau o f Investigation

(F B I), Simon was given reason to believe that the F B I wanted him

to implicate appellant. FBI Agent McLaughlin showed Simon bank sur

veillance photographs of the robber with the white coat and hat and

said, apparently in the first mention of appellant’s name in this ease,

"That’s Cecil Robinson.” Simon at the time said, "No,” but he later

changed his mind after being asked if the robber in question was one

Corley, a person whom Simon, according to his testimony, desired to

protect because of his innocence. Later that day, however, Simon failed

to implicate appellant in an interview with an Assistant United States

Attorney.

Simon had strong motivation to testify about appellant in a manner

that would ensure appellant’s conviction. Simon had received an 18-year

sentence from Judge Duffy for his part in the bank robbery, and he

had a motion to reduce sentence, pursuant to Fed. R. Crim. P. 35, pend-

5045

reason that he would provide the authorities with support

ing details that would help to implicate appellant in the

crime. Thus the fact that appellant was found with a .38

caliber gun after Simon had said such a gun was prepared

for use in the robbery may show nothing more than that

Simon knew that appellant owned a .38. To use the ex

ample referred to above, it is as if Simon had told the

authorities that all the robbers were men. We would then

not be surprised if Simon identified a man as a robber,

but we would hardly argue that Simon’s statement had

been significantly corroborated merely because the one

identified turned out to be a man.

The alternative purpose alleged in the majority opinion,

that of showing that appellant had the “ opportunity” to

commit the robbery, see Fed. R. Evid. 404(b), is also

indirectly linked to identity, see United States v. Ravich,

421 F.2d 1196, 1204 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 400 U.S. 834

(1970), but the gun evidence is of virtually no probative

significance in this regard. Neither the en banc majority

nor the Government attempts to demonstrate that the gun

evidence had any more probative value than that necessary

to meet Rule 401’s test of relevancy, discussed above. Ap

pellant did possess, when arrested, a single .38 caliber gun,

and that fact does show that “he had access to an instru

ment similar to that used to commit [the robbery],” ante,

------ F.2d at ------ . But had any one of the hundreds of

ing before the judge at the time he testified. He stated at appellant's

retrial his understanding that the Assistant United States Attorney

prosecuting appellant would be telling Judge Huffy whether he (the

prosecutor) was satisfied with Simon’s testimony.

Finally, it should be noted that Simon was hardly the type of person

who would have strong moral scruples against testifying falsely. In

addition to his bank robbery conviction, he had earlier weapons and

narcotics convictions, had violated the terms of bail and of conditional

discharge, and had used and sold heroin. At the time o f appellant’s

retrial, Simon had spent 12 of his 29 years in custody.

5046

thousands of persons who possess the same caliber gun—

no one contends that the gun here was other than undis-

tinctive and unremarkable—been arrested for this crime,

his possession of the gun would have been just as pro

bative of his “ opportunity” as was appellant’s possession

here.3

The possession of a single gun of a common type is

manifestly different from the situation in a case like United

States v. Ravich, supra, where a number of handguns were

found together with a large amount of ammunition, see

421 F.2d at 1204. Such an arsenal is unusual enough to

give its finding some probative value on the question of

opportunity or preparation. Similarly, the gun found in

United States v. Wiener, 534 F.2d 15 (2d Cir.), cert, denied,

429 U.S. 820 (1976), was seized from a distinctive burlap

bag that also contained the narcotics and paraphernalia

which were the principal items of evidence in the case,

see id. at 17 & n.3, 18. The gun in United States v. Cam

panile, 516 F.2d 288 (2d Cir. 1975), was the particular gun

that the defendant himself admitted taking to the area

of the robberies.4 Such guns, found in unusual situations

or closely linked to the crimes in question, have a degree

of probative value that is entirely missing in this case,

where the gun was undistinctive and no evidence linked it

3 It is o f course true that certain other factors tended to link appellant

to the crime, factors that would not have been present for other indi

viduals who own .38 caliber guns. But these factors do not and cannot

make the gun evidence more probative o f appellant’s opportunity, for

then we would assume the conclusion in the minor premise; we would

m effect be asserting that the gun evidence shows that appellant had

the opportunity to commit the crime because other evidence shows that

he did commit the crime.

4 The Campanile court, in admitting the gun evidence, noted that it

"was on the borderline o f admissibility in view of its tendency to

create unfair prejudice.” 516 P.2d at 292.

5047

to the commission of the crime.5 The gun here thus showed

no more about appellant’s “ opportunity” to commit the

crime than it would have shown about the opportunity of

anyone else found in possession of such a gun.

In view of the thinness of the gun evidence from both

“ corroboration” and “ opportunity” standpoints, it is per

haps not surprising that the trial judge’s charge did not

mention either of these purposes in connection with that

evidence. One would think that, had the judge intended

to allow the jury first to link the gun evidence to Simon’s

testimony or to appellant’s “ opportunity” and then to rea

son from there to appellant’s identity as a robber, he

would have instructed the jury accordingly, particularly in

view of the relative complexity or sophistication of such

analysis. Instead, Judge Bryan stated that the “ only”

purpose for the evidence’s admission was for the light it

shed on the question of identity. This statement, combined

with the obvious weakness of the evidence in terms of

other purposes, led the panel majority to focus on the ev

idence’s probative value in directly establishing appellant’s

identity, something that the en banc majority opinion (as

I read it) fails to do.

Since the panel majority’s characterization of the evi

dence as “very weak” for this purpose, 544 F.2d at 616,

is not disputed by the en banc majority, a short summary

of the panel majority’s reasoning should suffice here. We

recognized in United States v. Ravich, supra, 421 F.2d at

1204 n.10, that “ [t]he length of the chain of inferences

necessary to connect the evidence with the ultimate fact to

be proved necessarily lessens the probative value of the

5 Simon did not testify that Eohinson carried a gun in the hank; no

other witness testified that the robber, whom only Simon identified as

Robinson, carried a gun; the surveillance photographs showing the man

Simon identified as Bobinson do not show him carrying a gun.

5048

evidence.” Here the “chain of inferences” contained two

tenuous links. First, from appellant’s possession of a .38

ten weeks after the robbery, the jury would have had to

infer that he possessed a .38 at the time of the robbery,

when he might just as well have purchased the gun in the

interval between the robbery and his arrest.6 See 2 J.

Wigmore, Evidence § 410, at 384 (3d ed. 1940) (“ this in

ference is always open to doubt” ) ; id. §437, at 413 (“ the

disturbing contingency is that some circumstance operat

ing in the interval may have been the source of the sub

sequent existence” ). Second, even assuming that appel

lant, along with thousands of other New Yorks, possessed

a .38 on the date of the robbery, and assuming that a .38

was actually used in the robbery, see 544 F.2d at 617 n.8;

note 5 supra, the jury would then have had somehow to

infer that appellant’s undistinctive .38 was the .38 used in

the robbery. This inference was highly problematic on

the facts of this case, since no evidence was introduced

linking appellant’s gun to the robbery or indicating that

appellant carried a gun during the robbery, see note 5

supra. With two such difficult inferences to be overcome,

“the probative value of the testimony that appellant pos-

6 The majority opinion, ante, ------- F.2d at -------, quotes United States

v. Ravich, 421 F.2d 3 496, 1204 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 400 U.S. 834

(1970), for the proposition that the jury may draw such an inference

of prior possession from the fact of later possession. In context, how

ever, this Ravich statement is plainly not meant to stand on its own,

as an independent reason for admission of gun evidence, but rather is

a necessary precondition to the Ravich holding that possession of guns

prior to the robbery is evidence of opportunity to commit the crime

charged. See id. The applicability of this latter aspect of Ravich to

the instant case is discussed supra. In any event, it is certainly true

that an inference of prior possession may be drawn from the fact of

later possession. The problem, implicitly acknowledged in Ravich, see

id. (noting "rather small” probative value of gun evidence), is that

the inference is quite weak, as discussed in text, and is here compounded

by the necessity for making a second very weak inference before the

evidence can be held to have any direct bearing on the identity question.

5049

sessed a .38 ten weeks after the robbery must be character

ized as slight.” 544 F.2d at 618.

I believe that this slight probative value “ is substan

tially outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice.” Fed.

R. Evid. 403. I need not dwell here on the likelihood of

prejudice from admission of the gun evidence, since the

en banc majority opinion essentially agrees with the

analysis of the panel majority opinion, 544 F.2d at 618-19.

The danger, as the en banc majority points out, ante,------

F.2d a t ------ , is that such inflammatory evidence may dis

tract the jury from the question of guilt or innocence of a

specific crime, leading it to return a conviction not be

cause the defendant committed a particular robbery, hut

rather in order to punish him for carrying a gun or for

being an unsavory character. See Contemporary Mission,

Inc. v. Famous Music Corp., supra, slip op. at 3613 (Van

Graafeiland, J., concurring and dissenting) (“Evidence

which may he arguably relevant should not be admitted

if it tends . . . to mislead rather than enlighten the jury.” ).

The trial court’s limiting instruction here was directed

at dispelling this danger, hut, in my view, was inadequate

for this purpose. It mentioned the proper use of the gun

evidence, the identification purpose, only once and did not

mention any of the intermediate inferences necessary to

connect the gun evidence to appellant’s identity as a rob

ber, e.g., whether appellant had the gun on the date of the

robbery. Moreover, as Judge Mansfield has recently noted,

certain types of evidence are likely to be used “improp

erly” by a jury, “notwithstanding instructions.” United

States v. Ortiz, supra, slip op. at 2801 (dissenting opin

ion), citing United States v. Puco, 453 F.2d 539, 542 (2d

Cir. 1971) (“The average jury is unable, despite curative

instructions, to limit the influence of a defendant’s crimi

nal record to the issue of credibility.” ). Indeed, Rule 403

5050

“by its terms concedes the possibility that the negative

aspects of some evidence may simply be unmanageable

for the factfinder regardless of instructions,” for the rule

would be wholly unnecessary if cautionary instructions

could always dispel the possibility of unfair prejudice.

Dolan, supra, 49 S. Cal. L. Rev. at 250. See generally

Bruton v. United States, 391 U.S. 123, 129 (1968), quoting

Krulewitch v. United States, 336 U.S. 440, 453 (1949)

(Jackson, J., concurring) (“ ‘The naive assumption that

prejudicial effects can be overcome by instructions to the

jury . . . all practicing lawyers know to be unmitigated

fiction.’ ” ). Given the probable inefficacy of the cryptic

limiting instruction here, the slight probative value of the

gun evidence, and the very real danger of unfair prejudice,

I believe that admission of the gun evidence constituted

error.

m .

Reversible Error: Tine Relevance

of Other Evidence in the Case

The en banc majority opinion displays a certain ambiv

alence on the question of how evidence other than the gun

evidence is relevant to the Rule 403 assessment. On the

one hand, it asserts that the fact that this was a close case

before the jury is “ irrelevant to [the] weighing process.”

Ante, ------ F.2d at ------ n.9. On the other, it seems pre

occupied with showing that a strong case for conviction

existed apart from the gun evidence, summarizing the other

evidence against appellant in the same paragraph that it

approves the Rule 403 balancing done by the trial judge.

Id. a t ------ .

The majority cannot have it both ways. I f indeed there

were substantial other evidence against appellant, then the

already slight probative value of the gun evidence is further

5051

diminished to the vanishing point, since the Government

would have less need for this evidence in order to win its

case. See United States v. Ravich, supra, 421 F.2d at 1204.

But I believe that the other evidence against appellant was

weak, a fact that, while making the gun evidence of some

what more value to the Government, also makes it more

likely that the trial court’s error in admitting the gun ev

idence affected the judgment, see R. Traynor, The Riddle

of Harmless Error 28 (1970).

The weakness of the Government’s case becomes immedi

ately apparent when the evidence summarized in the en

banc majority opinion is placed in its proper context. The

principal witness against appellant, Simon, had strong

motivation to help the prosecution in order to reduce his

own sentence, as the majority recognizes, ante, ------ F.2d

at ------ ; the majority fails to note certain other ways in

which Simon’s credibility was diminished, summarized in

note 2 supra. Cf. United States v. Ortiz, supra, slip op. at

2800-01 (Mansfield, J., dissenting) (noting “unsavory back

ground” of crucial Government witness in context of weigh

ing probative value and prejudice). As for other evidence,

the majority mentions that appellant’s fingerprint was

found on the right rear cigarette lighter panel of Brown’s

car, but it fails to note that Simon had appellant riding in

the left rear position going to the robbery and testified

that appellant was not in the rear at all after the robbery.

Hence the fingerprint evidence, which could not be dated,

see 544 F.2d at 614, proves nothing more than that appel

lant had at some point ridden in Brown’s car, a fact that

is undisputed and unsurprising in view of Brown’s testi

mony that he had given appellant, an acquaintance and fel

low student, rides a half-dozen times prior to the robbery.

As for the use of “hospital-type jackets,” from which the

Government implies some sort of connection with appellant,

who worked at a hospital, it is undisputed that the jackets,

5052

while white, were actually butchers’ jackets and in fact had

“meat market” written on them. The bank surveillance

photographs of the robber alleged to be appellant were

described by Simon as “hazy” and have provoked substan

tial uncertainty on this court, see 544 F.2d at 614. The

robber in those photographs, as is noted above, note 5

supra, does not appear to be carrying any gun, whereas

appellant allegedly carried the infamous .38, which he later

“handed over” to Garris in the car, according to Simon and

as emphasized by the majority, ante,------ F.2d a t------- . This

latter fact is particularly surprising because it is incon

sistent with appellant’s possession of a .38 at the time of

arrest. If he handed it over after the robbery, how did he

get it back? Why, if it were his gun as Simon claimed,

would he hand it over to someone else after the robbery?

I note, as the majority does not, that none of the eight non

participant eyewitnesses to the crime identified appellant

as one of the robbers. Only Simon did so.

In view of the infirmities in the Government’s case, it is

not surprising that a hung jury resulted at appellant’s first

trial, where the jury was not exposed to the gun evidence,

and that the jury at appellant’s second trial nearly hung,

requiring extensive deliberations over three days and two

Allen-type charges before it could reach a verdict. While

there were some minor differences between the evidence

adduced at the two trials, there is little doubt that the intro

duction of the gun evidence was by far the most significant

difference. Given the weakness of the Government’s other

evidence, the gun evidence had to have had an impact on

the jury. There is simply no way to view its admission as

harmless, and the majority does not argue otherwise. Con

cluding that the error in admitting the gun evidence af

fected the judgment, I would reverse.

5053

IV.

The Juror’s Note and the

Two Allen Charges

Because the panel majority reversed on the Buie 403

ground, Judge Gurfein and I did not have to reach the

questions whether the court below committed reversible

error either in sealing the juror’s note expressing her

“ strong reasonable doubt” or in giving two Allen-type

charges after knowing of the jury’s 11-1 split, with the

second charge obviously directed at the particular woman

who had written the judge of her doubt. The en banc

majority concludes that neither issue provides ground for

reversal.

The majority’s conclusion as to the first issue is ap

parently based on the harmless error doctrine. The

majority states that “ the better procedure is for the trial

judge to disclose the contents of a juror’s note to the

parties,” but that “ the failure to do so here was hardly

prejudicial error.” Ante, ------ F.2d at — —. This latter

conclusion may be supported on the record before us, but

the seriousness of the trial court’s failure to disclose the

note’s contents should be emphasized. This court recently

held that a trial court’s failure to disclose the substance

of its communications with a juror constituted error,

United States v. Taylor, No. 76-1210, slip op. 2805, 2840

(2d Cir. Apr. 13, 1977), noting that such private com

munications violate a defendant’s right to be present at all

stages of the proceedings, id. at 2839; see Fed. R. Crim. P.

43(a); Illinois v. Allen, 397 U.S. 337, 338 (1970). In

another recent opinion, this court stressed the importance

of “an informed discussion [between court and counsel]

on the proper course to follow,” United States v. Van

Meerhehe, 548 F.2d 415, 418 (2d Cir. 1976), cert, denied, 45

U.S.L.W. 3691 (U.S. Apr. 18, 1977), citing the Robinson

5054

panel opinion for this proposition, id. at 418 n.2; see 544

F.2d at 621 (“benefits” of “ informed discussion and debate

between court and counsel . . . even where a court may be

aware in the abstract of its own alternatives” ). The trial

court here should have revealed to counsel the substance

of the juror’s note, without disclosing the individual juror’s

name or the jury vote.7 See United States v. Dellinger, 472

F.2d 340, 377-80 (7th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 410 U.S. 970

(1973).

With regard to the trial court’s giving of two Allen-type

charges after knowing of the jury’s 11-1 split, the majority

emphasizes parts of the court’s second charge and ignores

the overall potential for coercion. The charge did mention

“individual judgment” and “ individual conscience,” hut

it also instructed the jurors—and in reality only the one

juror whose note the court was explicitly answering by

giving the second Allen charge—that they should have “a

proper regard for and deference to the opinions of one

another,” that they “ should listen to one another’s views

with a disposition to he convinced,” and that they had a

“duty . . . to agree upon a verdict” if they could do so.

The charge here, in short, was quite similar to the charge

of Allen v. United States, 164 U.S. 492, 501 (1896), a charge

that, “ [1] ike dynamite . . . should be used with great

caution, and only when absolutely necessary,” United

States v. Flannery, 451 F.2d 880, 883 (1st Cir. 1971).

7 The majority’s reference to the problems that might arise were the

juror’s name to be disclosed, a n te,-------F.2d a t -------- , is puzzling. There

simply was no reason for the name to be revealed; the note’s contents

could have been read to counsel by the court with the name at the

bottom of the note withheld. The majority opinion also states that

appellant's counsel did not seek to have the note unsealed. Id. He did,

however, make clear his belief that the sealing prejudiced his ability to

act on behalf o f his client. In response to the court’s request for advice

as to how to answer the note, appellant’s counsel stated: "Without my

knowing what is in her note, I can’t comment too intelligently, except

that I believe it is premature to give an Allen charge.”

5055

Here the second charge was not necessary and could not

he otherwise than coercive. While the majority cites cases

in which we have upheld the giving of one Allen charge

after trial court notice of an 11-1 jury division, ante,------

F.2d at ------there is apparently no case, in this or any

other circuit, upholding the giving of two Allen charges

after the jury informs the judge of its 11-1 split. The

fact that such a case has not arisen is itself indicative of

a well-founded reluctance on the part of trial judges twice

to tell a lone holdout to listen to other jurors’ views “with

a disposition to be convinced.” When the judge so in

structs the lone holdout, “ the effect . . . is unavoidably to

add the judge’s influence to the side of the majority . . . .,”

with the sole minority juror “develop [ing] a sense of isola

tion and the impression that [he or she is] the special

object of the judge’s attention.” United States v. Sawyers,

423 F.2d 1335, 1349 (4th Cir. 1970) (Sobeloff, J., dissent

ing) ; see United States v. Meyers, 410 F.2d 693, 697 (2d

Cir.) (Smith, J., dissenting), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 835

(1969); Mullin v. United States, 356 F.2d 368, 370 (D.C.

Cir. 1966); Note, The Allen Charge: Recurring Problems

and Recent Developments, 47 N.Y.U.L. Rev. 296, 306-08

(1972); Note, Due Process, Judicial Economy and the

Hung Jury: A Reexamination of the Allen Charge, 53 Va.

L. Rev. 123, 130-32 (1967).

Here the lone holdout quite obviously knew that she was

“ the special object of the judge’s attention.” Her note

told the judge that she was the holdout, so that he knew

to whom his remarks were addressed, and she knew that he

knew. This aspect of our case, coupled with the giving of

two Allen charges, differentiates it from the cases cited by

the majority. Making “an individualized determination of

coercion,” as the majority opinion suggests, ante, ------

F.2d a t ------ , I cannot avoid the conclusion that there was

impermissible coercion here.

5056

V.

I would reverse and remand for a new trial. In the light

of two legal questions that by any stretch of the imagina

tion have to he treated as close, a weak Government case,

one hung jury, and one temporarily hung jury, a new trial

for appellant seems to me to be just as desirable in the

overall interests of justice, as it did at the time this case

was heard, like any other, by a panel of this court.

G u r f e in , Circuit Judge (concurring in Judge Oakes’ dis

senting opinion) :

I concur in Judge Oakes’ strong dissenting opinion. I

wish to add that I am sorry the court saw fit to take this

case en banc. The only rule of law that has emerged is one

that will he of little help in reviewing future rulings on

evidence under Rule 403. Nobody disagrees that generally

the ruling of the trial judge on his weighing of probative

value against the substantial prejudice is entitled to great

weight. But to say that he may not be reversed unless his

decision is “arbitrary or irrational,” in my view, simply

detracts from meaningful review. For unless we can de

fine what is “arbitrary” or “ irrational,” the use of such

pejorative words simply tends to support an utter abdica

tion of appellate review. I think that when we are weighing

“ prejudice” our duty as a first reviewing court should go

somewhat further, for, as Judge Mansfield puts it, “ the

effect in such a case might be to arouse the jury’s passions

to a point where they would act irrationally in reaching

a verdict.” And I predict that occasions will arise when