Ayers v. United States Brief of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund as Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitions for Writs of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ayers v. United States Brief of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund as Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitions for Writs of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1990. 48dd2d7f-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4decd394-43a5-45ac-bcc9-aac8d1240ff1/ayers-v-united-states-brief-of-the-naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-as-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-petitions-for-writs-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

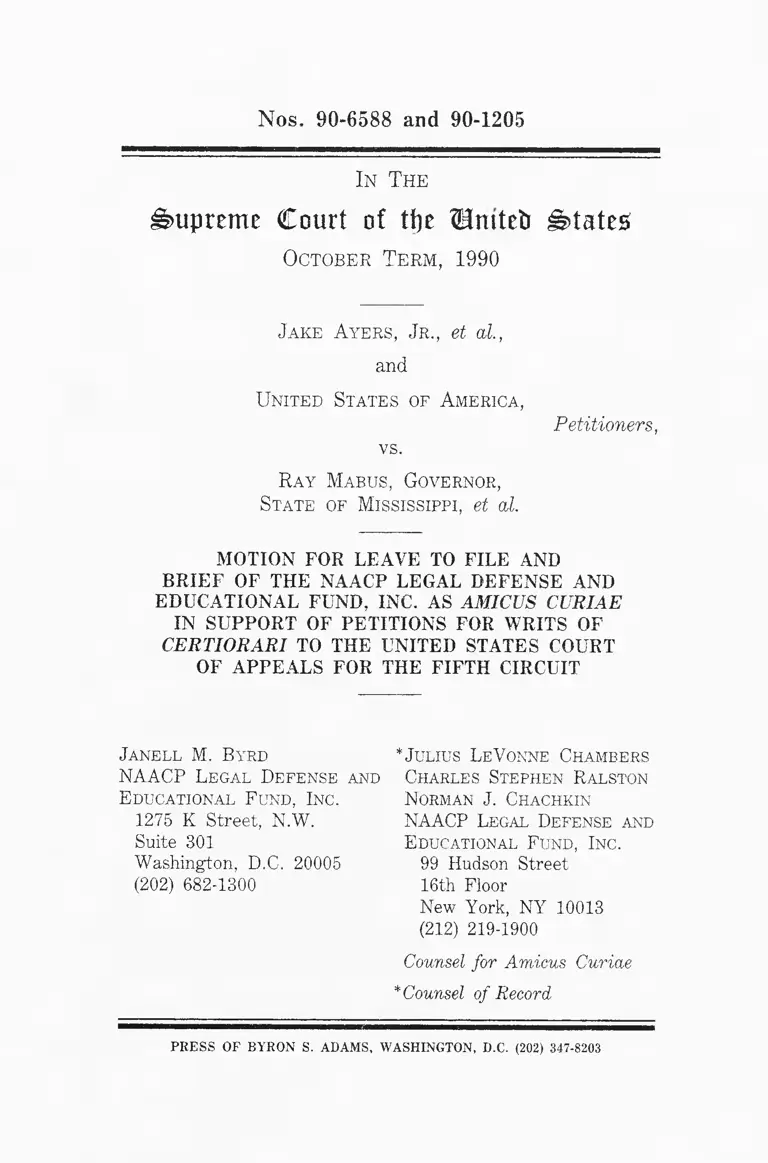

N os. 90-6588 and 90-1205

In T h e

Supreme Court of tf)c Brntetr states

Octo ber T e r m , 1990

J ake Ayers, J r ., et a l,

and

United States of America,

vs.

Ray Mabus, Governor,

State of Mississippi, et al.

Petitioners,

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE AND

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. AS AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONS FOR WRITS OF

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT

OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Janell M. Byrd

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational F und, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

* Julius LeVonne Chambers

Charles Stephen Ralston

Norman J. Chachkin

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

* Counsel of Record

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

Nos. 90-6588 and 90-1205

In the

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1990

Jake Ayers, Jr., ex a!.,

and

United States of America,

Petitioners,

vs.

Ray Mabus, Governor,

State of Mississippi, et al.

M OTION OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. FOR LEAVE TO FILE

BRIEF AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONS

FOR WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

(LDF) respectfully moves the Court for leave to file the

2

attached brief as amicus curiae in support of the petitions for

writs of certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit. Both the Ayers petitioners and the United

States have consented to the filing of this brief. Respondents,

Ray Mabus, Governor of the State of Mississippi, et al., have

denied consent.

LDF is a non-profit corporation organized under the laws

of the State of New York. It was formed to assist black

citizens in securing their rights under the Constitution. LDF

has significant interests in this litigation. LDF has litigated

extensively in the area of school desegregation.* It litigated

the five cases whose interpretation is directly involved in

determining a state’s obligation to dismantle a formerly

de jure segregated system of higher education — the central

issue raised in these petitions.

Further description of the interests of amicus LDF appears at pages

2-5 of the attached brief, including a description of LDF’s history of

involvement in school desegregation litigation.

3

LDF believes that the decision entered below is in error

and will have substantial adverse effects on the educational

opportunities for black citizens that LDF’s litigation seeks to

expand. Because of the direct effect on LDF’s litigation

efforts and LDF’s extensive involvement in the development

of the law in this area, LDF’s participation as amicus curiae

in this case will be of assistance to the Court.

Janell M. Byrd

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 682-1300

Respectfully submitted,

/s/ Janell M. Byrd

* Julius LeVonne Chambers

Charles Stephen Ralston

Norman J. Chachkin

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Counsel fo r Amicus Curiae

* Counsel o f Record

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .............................................. ii

Interest of the NAACP Legal

Defense Fund As Amicus Curiae .................................... 1

STATEMENT OF RELEVANT FA C T S............... ... 6

SUMMARY OF THE A R G U M EN T..................... .. . 11

A R G U M EN T..................................................................... 12

CONCLUSION ................................................................... 19

l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cas es Pa o

Adams v. Lucy, 228 F.2d 619 (5th Cir. 1955),

cert, denied, 351 U.S. 931 (1956) . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Adams v. Richardson, 356 F. Supp. 92

(D.D.C.), modified and a ff’d

unanimously en banc, 480 F.2d 1159

(D.C. Cir. 1973), dismissed sub nom.

Women’s Equity Action League v.Cavazos,

906 F.2d 742 (D.C. Cir. 1990)................................. 2, 3

Alabama State Teachers Association v.

Alabama Public School and College

Authority, 289 F. Supp. 784 (M.D. Ala.

1968), aff’d per curiam, 393 U.S. 400

(1969)............... .. ................. ... 3

Ayers v. Attain, 914 F.2d 676 (5th

Cir. 1990) (en banc) ....................................... 4, 14, 17, 18

Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385

(1986)..................... .. ................. .................. 3

Board o f Education o f Oklahoma City Public

Schools v. Dowell, 111 S. Ct. 230

(1991).................................... ... 13, 14

Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954).................. .. .2 , 12, 14, 15, 16

ii

Page

Brown v. Board o f Education, 349 U.S. 294

(1955).............................................................................. 13

Geier v. Alexander, 801 F.2d 799 (6th Cir.

1986).............................................................................. 3, 14

Geier v. University o f Tennessee,

597 F.2d 1056 (6th Cir.), cert, denied,

444 U.S. 886 (1979).............................. .. ................. 14

Green v. County School Board o f

New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430

(1968)............................................ ................................. 3, 14

Keyes v. School District No. 1,

413 U.S. 189 (1973)...................................................... 18

League o f United Latin American Citizens

v. Clements, No. 12-87-5242-A,

filed December 2, 1987 (107 Dist. Ct. T e x .) ............ 19

Lee v. Macon County Board o f Education,

267 F. Supp. 458 (M.D. Ala.), a ff’d sub

nom. Wallace v. United States, 389

U.S. 215 (1967)............ .................................................. 14

McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971)........................ 18

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents,

' 339 U.S. 637 (1950)......................................................... 2

Meredith v. Fair, 305 F.2d 343 (5th Cir.)

cert, denied, 371 U.S. 828 (1962)..................... ... 2

iii

Page

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267

(1977)................................................................................. 14

Norris v. State Council o f Higher Education

fo r Virginia, 327 F. Supp. 1368

(E.D. Va.), a ff’d mem., 404 U.S. 907

(1971)......................................... 3

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950)........................... 2

United States v. Hinds County School Board,

417 F.2d 852 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied,

396 U.S. 1032 (1970), delaying order-

reversed sub nom. Alexander v. Holmes

County Board o f Education, 396 U.S. 19

(1969)................................................................................. 9

United States v. Louisiana, 380 U.S. 145

(1965)............... .. .................................................. . . . . 14

United States v. Louisiana, 692 F. Supp. 642

(E.D. La. 1988), order vacated,

751 F. Supp. 606 (E.D. La. 1990).................. 14, 16, 17

United States v. Scotland Neck City Board o f

Education, 407 U.S. 484 (1972)................................ 14

Wright v. Council o f City o f Emporia,

407 U.S. 451 (1972)................................. 14

IV

Page

Constitution, Statutes and Regulatory Materials:

U.S. Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment..................... 3

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. § 2 0 0 0 d ..................... .. ................................ 3

Revised Criteria Specifying the Ingredients

of Acceptable Plans to Desegregate State

Systems of Public Higher Education,

43 Fed. Reg. 6658 (Feb. 15, 1978)...........................4, 14

Other Authorities:

Bureau of Education, United States Department of the

Interior, Survey o f Negro Colleges and Universities

(1928)................................................................................. 7

Kujovich, Equal Opportunity in Higher Education and the

Black Public College: The Era o f Separate But Equal,

72 Minn. L. Rev. 29 (1987) . . ' .................................... 7

Payne, Forgotten . . . but not gone: The Negro

Land-Grant colleges, Civil Rights Digest 12

(Spring 1970)..................................................................... 7

W.E. Trueheart, The Consequences o f Federal and

State Resource Allocation and Development

Policies fo r Traditionally Black Land-Grant

Institutions: 1862-1954 (University Microfilms

International, Ann Arbor, Michigan) (1979)................... 7

v

Nos. 90-6588 and 90-1205

In the

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1990

Jake Ayers, Jr., et al.,

and

United States of America,

Petitioners,

vs.

Ray Mabus, Governor,

State of Mississippi, et al.

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. AS AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONS FOR WRITS OF

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT

OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Interest of the NAACP Legal

Defense Fund As Amicus Curiae

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

(LDF) is a non-profit corporation established to assist African

2

American citizens in securing their constitutional and civil

rights. LDF historically has had and continues to have a

major role in litigation efforts challenging discrimination and

segregation in education.1

The interests of LDF are significant in this case. LDF

successfully litigated the first court challenge to racial

segregation in Mississippi’s higher education system,

Meredith v. Fair, 305 F.2d 343 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 371

U.S. 828 (1962). The central question presented here

regarding the scope of a state’s duty to desegregate a formerly

1 See, e.g., Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

LDF represented the plaintiffs in the litigation that resulted in the initiation

of desegregation efforts in public higher education systems in 18 states,

including the State of Mississippi. Adams v. Richardson, 356 F. Supp.

92 (D.D.C.), modified and a ff’d unanimously en banc, 480 F.2d 1159

(D.C. Cir. 1973), dismissed sub nom. Women’s Equity Action League v.

Cavazos, 906 F.2d 742 (D.C. Cir. 1990). Other LDF higher education

desegregation cases include: Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950);

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637 (1950); Adams v.

Lucy, 228 F.2d 619 (5th Cir. 1955), cert, denied, 351 U.S. 931 (1956).

3

de jure segregated system of higher education involves the

interpretation of five cases litigated by LDF.2

As a result of litigation brought by LDF,3 in 1978 the

Office for Civil Rights of the United States Department of

Health, Education and Welfare (HEW)4 promulgated remedial

standards for desegregating formerly de jure state systems of

higher education pursuant to the Fourteenth Amendment and

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d.

The "HEW Guidelines" imposed an "affirmative duty to take

effective steps to eliminate the de jure segregation," and

required "more than mere abandonment of discrimination

2 Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. 385 (1986); Green v. County School

Board o f New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968); Geier v. Alexander,

801 F.2d 799 (6th Cir. 1986); Norris v. State Council o f Higher Education

fo r Virginia, 327 F. Supp. 1368 (E.D. Va.), aff’d mem., 404 U.S. 907

(1971); and Alabama State Teachers Association v. Alabama Public School

and College Authority, 289 F. Supp. 784 (M.D. Ala. 1968), aff’d per

curiam, 393 U.S. 400 (1969).

3 Adams v. Richardson, supra note 1.

4 The Department of Education subsequently was substituted for HEW

in the litigation.

4

through the state’s adoption of passive or race neutral

policies."5

Under these standards, as well as decisions of several

federal courts, progress toward equal opportunities in higher

education for African Americans began to be made. Some

states moved not just to open the doors of formerly white

institutions, but also took gradual steps to enhance their long-

neglected and under-funded historically black colleges, which

continue to educate a substantial portion of black college

students.6

This litigation marks the first time that the Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit en banc has considered the duty

owed by formerly de jure states in higher education. Instead

of requiring the progress that has occurred elsewhere,

3 Revised Criteria Specifying the Ingredients of Acceptable Plans to

Desegregate State Systems of Public Higher Education, 43 Fed. Reg. 6658

(Feb. 15, 1978) reprinted in the Ayers Petitioners’ Appendix ("Ayers

App.") A90.

6 Id. at 6660, Ayers App. A92.

5

however, the decision in Ayers v. Attain, 914 F.2d 676 (5th

Cir. 1990) (en banc), effectively cuts off the desegregation

process. The court below requires only that formerly de jure

segregated state systems of higher education implement what

are described as good faith, race-neutral policies. In so

holding the court ignored the massive overlay of entrenched

disadvantage and inequity caused by the vestiges of the prior,

overtly dual system and the consequent continued existence in

Mississippi, in practice if not in theory, of the dual system.

Because of the important goal of providing full

educational opportunity for African American citizens free

from the vestiges of past discrimination and segregation, LDF

urges the Court to grant the pending petitions for certiorari

in order to reverse the Ayers decision.

6

STATEMENT OF RELEVANT FACTS7

Opportunities for higher education for freed slaves and

their descendants following the Civil War were first provided

in Mississippi in 1878, when the Mississippi State Legislature

designated Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College for

the education of black youth (United States’ Appendix "U.S.

App." 110a-11a). Since 1844, the State had operated the

University of Mississippi, which was solely for white persons.

The same year that Alcorn was designated for African

Americans, the state established Mississippi Agricultural and

Mechanical College (later Mississippi State University) for

white persons only.

Thereafter, the State established the Mississippi

University for Women for whites in 1884, the University of

Southern Mississippi for whites in 1910, Delta State

We adopt the detailed factual review provided by the Ayers

petitioners.

7

University for whites in 1924, Jackson State University for

the training of black teachers for black public schools in

1940, and Mississippi Valley State University for the training

of black teachers and for vocational training for black students

in 1946.8

That funding and support for the institutions dedicated for

the education of African Americans was grossly inferior to

that for whites is undisputed.9 That this severely and

adversely affected the quality of life for Mississippians of

African descent is admitted by the State.

8 U.S. App. 109a-114a.

9 U.S. App. 65a-66a, 151a-52a; Bureau of Education, United States

Department of the Interior, Survey o f Negro Colleges and Universities 416-

17 (1928) (Alcorn A & M "is largely a school of preparatory grade,

concentrating its efforts on vocational and manual training. . . . [It] is

lacking a properly qualified teaching staff and educational equipment for

standard college work."). For a review of the grossly disparate funding

provided public institutions for blacks during the "Jim Crow” era and

thereafter see also generally Kujovich, Equal Opportunity in Higher

Education and the Black Public College: Hie Era o f Separate But Equal,

72 Minn. L. Rev. 29 (1987); W.E. Trueheart, Tlte Consequences of

Federal and State Resource Allocation and Development Policies for

Traditionally Black Land-Grant Institutions: 1862-1954 (University

Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, Michigan 1979); Payne, Forgotten

. . . but not gone: The Negro Land-Grant Colleges, Civil Rights Digest 12

(Spring 1970).

8

[W]hen the 1945 survey was made there were 22

times as many white doctors in Mississippi in

proportion to the white population as Negro (doctors

in proportion to the Negro population; 13 times as

many dentists, 5 times as many pharmacists, 420

times as many lawyers, and 40 times as many social

workers.

From 1948-1953, the institutions for white students

in the State conferred 14,205 degrees, one for every

131.1 white persons in the population; whereas the

colleges for Negroes conferred 1,268 degrees, or one

for every 778.1 Negroes in the total population.10

In 1980, African Americans comprised 35.4 percent of

the total population of Mississippi, and 41.3 percent of all

person ages 16-21 in the State (Ayers App. A113-117).

Nonetheless, in 1984-85, African Americans received 23.9

percent of all undergraduate degrees and 20.6 percent of

graduate degrees. Only 4.4 percent of the law degrees

awarded during the period 1982 to 1986 went to African

Americans. Of the medical and dental degrees awarded in

10 "Higher Education in Mississippi," Board of Trustees of State

Institutions of Higher Learning of the State of Mississippi (Ayers App

A102-04).

9

1985-86, only 4.5 percent went to African Americans.

(Ayers App. A179-204.) The poverty rate for African

Americans in Mississippi in 1980 was 44.4 percent compared

to 12.6 percent for whites (Ayers App. A114-116).

Educational opportunities for African Americans in

Mississippi today are directly reflective of and limited by

Mississippi’s history of race discrimination and segregation in

its education system.11 Today, African American students

continue to be channelled systematically to the historically

black institutions,12 and pursuant to "mission designations"

11 Disparities in the quality of the educational offerings at historically

black institutions (HBIs) and historically white institutions (HWIs) are well

documented and continue at every level as proved at trial: level of faculty

education (U.S. App. 55a); faculty salaries (U.S. App. 56a), program

offerings (U.S. App. 57a-61a); funding (U.S. App. 66a); and facilities

(U.S. App. 68a). These inequities in higher education simply extend the

inequities spawned in Mississippi’s longstanding dual system at the

elementary and secondary level of education. See, e.g., United States v.

Hinds County School Board, 417 F.2d 852 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied,

396 U.S. 1032 (1970), delaying order reversed sub nom. Alexander v.

Holmes County Board o f Education, 396 U.S. 19 (1969).

12 Shortly after the court ordered the admission of James Meredith to

the University of Mississippi in 1962, the Board of Trustees of State

Institutions of Higher Learning of the State of Mississippi and the HWIs

adopted a new admissions requirement of a score of 15 on the ACT, a

(continued...)

10

tied directly to prior inequities resulting from overt

discrimination, financial support continues to be channelled

disproportionately to the historically white institutions.13

Thus, hardly a dent has been made in Mississippi’s

entrenched racial caste system in higher education.14 Yet the

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ruled that Mississippi

need do no more than adopt good faith, race-neutral policies,

12(... continued)

standardized college admission examination. The purpose of this change

was to deter black enrollment. (U.S. App. 51a.) Despite strong evidence

that the ACT should not be used as the sole criterion for admission and

the existence of better predictors of success in college with less adverse

effect on black students, the HWIs continue to rely exclusively on the

ACT. Racially identifiable student enrollments (U.S. App. 50a-51a) and

racially identifiable faculties (U.S.App. 56a), continue to correspond

strongly with the original racial designation of each institution.

13 The en banc court found that the "mission designations had the

effect of maintaining the more limited program scope at the historically

black universities," (U.S. App. 31a), and that "the disparities are very

much reminiscent of the prior system. The inequalities among institutions

largely follow the mission designations" (U.S. App. 37a). See also U.S.

App. 66a.

14 Mississippi is among the states most recalcitrant to higher education

desegregation efforts, requiring the United States to sue the state for its

failure to adopt adequate desegregation measures. The desegregation plan

adopted by the state has always been under-funded (U.S. App. 58a).

11

irrespective of results.15 Mississippi is not required to take

affirmative measures to correct its wrong; black citizens are

not entitled to an effective remedy.

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

This is a case of tremendous importance. Higher

education has increasingly become the key to breaking the

cycle of poverty, gaining full employment in the growing

technical and highly skilled workforce, and developing

healthy, responsible and productive communities. Equal

access to this education free from the burdens and limitations

of past and present discrimination and segregation is essential

if African Americans are to enjoy the full rights and

privileges to which all citizens are entitled.

This Court should grant the petitions for writ of

certiorari because of the conflict in the circuits regarding the

15 U.S. App. 2a.

12

duty to correct state-mandated, separate and inferior

educational systems for blacks, the broad impact of the case,

the legal error committed below, and the real and substantial

harm caused if the Ayers decision is allowed to stand.

ARGUMENT

Prior to and following Brown, the federal courts made

some efforts to open the doors of formerly all-white higher

education institutions to "qualified" minority students.16 This

Court, however, has never actually examined the dimensions

of the problem created by decades of no higher educational

opportunities for African Americans followed by drastically

inferior opportunities and mandatory segregation throughout

the Southern and border state systems of higher education.17

16 See, e.g., supra note 1.

17 As late as 1940, seventy-seven percent of the nation’s African

American population resided in the seventeen southern and border states

and comprised twenty-two percent of the region’s population. But the ten

million African Americans in the region received less than four percent of

(continued...)

13

The Court has not explored the necessity for remedies to

eliminate the vestiges of those higher education systems in the

same way that it has for elementary and secondary schooling

in the series of decisions from Brown v. Board o f Education,

349 U.S. 294 (1955) (Brown II), to Board o f Education o f

Oklahoma City Public Schools v. Dowell, 111 S. Ct. 630

(1991). It is necessary and appropriate that the Court address

these issues in this case.18

17(... continued)

the federal land grant monies allocated to these states. Overall these

African American citizens were limited to colleges receiving just over five

percent of total expenditures for public higher education. In eight states,

accounting for forty percent of all African Americans in the nation, there

were no accredited public colleges available to persons of African descent.

Kujovich, supra note 9 at 98-101.

18 It is essential that the Court fully hear this case and not limit the

grant of the private plaintiffs’ petition to specified questions. This will

ensure that the Court has the benefit of a thorough discussion of all record

facts and evidence that will be useful in considering the legal questions

presented. Additionally, this will provide the Court the flexibility to

determine after briefing on the merits and oral argument whether it is

necessary to decide all issues.

14

Not only is there a conflict in the circuits,19 legal error by

the court below,20 and broad impact21 as explained in the

19 The decision of the Fifth Circuit en banc in Ayers conflicts with

the Sixth Circuit decision in Geier v. Alexander, 801 F.2d 799 (6th Cir.

1986).

20 The standard applied in school desegregation cases heretofore has

been one where the state actor has an affirmative duty to dismantle the

formerly de jure segregated system "root and branch," by eliminating all

vestiges of the dual system to the extent practicable. See Board o f

Education o f Oklahoma City Public Schools v. Dowell, 111 S. Ct. 630

(1991); Wright v. Council o f City o f Emporia, 407 U.S. 451 (1972);

United States v. Scotland Neck City Board o f Education, 407 U.S. 484

(1972); Green v. County School Board o f New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430 (1968); Revised Criteria for Specifying the Ingredients of Acceptable

Plans to Desegregate State Systems of Higher Education, 43 Fed. Reg.

6658 (Feb. 15, 1978). While the methods of desegregating or eliminating

the vestiges of past discrimination in higher education systems will be not

be identical to those employed in elementary and secondary school

systems, the obligation of a state with a de jure history to eliminate those

vestiges is just as exacting in higher education as it is at the elementary

and secondary level. See Ayers v. Allain, 914 F.2d at 692 (Goldberg, J.,

dissenting); id. at 693 (Higginbotham, J., concurring in part and dissenting

in part); Geier v. Alexander, 801 F,2d at 802; Geier v. University o f

Tennessee, 597 F,2d 1056, 1065 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 444 U.S. 886

(1979); United States v. Louisiana, 692 F. Supp. 642, 653-58 (E.D. La.

1988) (per curiam, three-judge district court), order vacated, 751 F. Supp.

606 (E.D. La. 1990) (pursuant to Ayers)-, Lee v. Macon County Board o f

Education, 267 F. Supp. 458, 474-75 (M.D. Ala.) (per curiam, three-

judge district court) (state colleges have an "affirmative duty to effectuate

the principles of Brown"), ajf’d sub nom. Wallace v. United States, 389

U.S. 215 (1967). See also Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267, 280 (1977)

(decree "must be designed as nearly as possible ‘to restore the victims of

discriminatory conduct to the position they would have occupied in the

absence of such conduct’" [citations omitted]); United States v. Louisiana,

380 U.S. 145, 154 (1965) (remedy should be shaped "so far as possible

to eliminate the discriminatory effects of the past as well as bar like

discrimination in the future").

15

petitions for certiorari, but the special and important nature

of this case to the Nation’s history and its will to correct

serious constitutional wrongs justifies granting the writ.

With respect to higher education, the Court is in much

the same position now as it was in 1954 with respect to

elementary and secondary education. At that time, in Brown,

the Court said:

In approaching this problem, we cannot turn the

clock back to 1868 when the Amendment was

adopted, or even to 1896 when Plessy v. Ferguson

was written. We must consider public education in

the light of its full development and its present place

in American life throughout the Nation. Only in this

way can it be determined if segregation in public

schools deprives these plaintiffs of the equal

protection of the laws.

Today, education is perhaps the most important

function of state and local governments. . . . It is

:i The impact extends beyond the states of Mississippi, Louisiana and

Alabama, which are all currently involved in litigation. Numerous other

state systems, including Maryland, Kentucky, Texas, and Pennsylvania,

are pending before the Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights,

for a determination whether they have satisfied their duty to dismantle

formerly de jure segregated systems of higher education. A determination

from the Court of the proper standard would apply to these states in

administrative proceedings as well.

16

required in the performance of our most basic public

responsibilities, even service in the armed forces. It

is the very foundation of good citizenship.

347 U.S. at 492-93.

In the thirty-six years since Brown, a college education

has become a necessary prerequisite, not only to attain upper

level jobs, but for basic employability in large numbers of

positions with employers that increasingly require a highly

skilled and intelligent workforce. As the three-judge district

court stated in United States v. Louisiana, 692 F. Supp. 642

(E.D. La. 1988):

In vast, ever-growing segments of the American

workforce, a high school diploma is not enough; a

college education is often more critical than a high

school education. The argument that the State

requires students to attend primary and secondary

school but cannot, or at least does not, require them

to attend college fails to acknowledge the realities of

our nation today. The purpose for a State’s broad

police power to enact truancy and other regulatory

school laws . . . is to promote an educated, self-

supporting citizenry that can effectively and

intelligently participate in our society. . . . [T]hese

underlying interests of American society are what

compel persons to seek higher education on their

own volition. If blacks and other minorities are to

17

compete in the market place for more attractive and

higher paying jobs in business and industry and to

avail themselves of the benefits of corporate

affirmative action programs, they need a college

degree.

Id. at 656-57 (citations omitted).

Because higher education has become a public necessity

today much in the same way that elementary and secondary

education had become a public necessity by 1954, it is

essential that every citizen have access to higher education

free from the vestiges and limitations posed by past and

continuing racial discrimination and segregation.

At a time when progress in attaining that goal is just

beginning, the Ayers decision erects a solid barrier to further

advancement. The Fifth Circuit’s finding of compliance

where a state has done nothing but adopt "good faith, race-

neutral policies,"22 simply locks in existing, very substantial

vestiges of past discrimination and segregation. It is ironic

22 Mississippi falls short of even that low standard given its

discriminatory use of ACT scores and mission designations.

18

that this barrier to further progress has been erected for

Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas,23 several of the states that

have been the most resistant to desegregating their higher

education systems.

The Ayers decision is contrary to this Court’s

requirement that affirmative and effective measures be used

to dismantle segregated school systems.

[W]here a dual system was compelled or authorized

by statute at the time of our decision in Brown v.

Board of Education, . . . the State automatically

assumes an affirmative duty ‘to effectuate a transition

to a racially nondiscriminatory school system, . . .

that is, to eliminate from the schools within their

school system ‘all vestiges of state-imposed

segregation. ’

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189, 200 (1973)

(citations omitted). "Any other approach would freeze the

status quo that is the very target of all desegregation

processes." McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39, 41 (1971).

23 Texas operates under a desegregation plan entered with the

Department of Education but also has been sued by private plaintiffs under

state law in League o f United Latin American Citizens v. Clements,

No. 12-87-5242-A, filed December 2, 1987 (107 Dist. Ct., Tex.).

19

If left intact the Ayers decision will assure that the

consequences of the serious and longstanding constitutional

violations in the critical area of higher education will continue

uncorrected and with incalculable harmful effects on the lives

of African American citizens.

CONCLUSION

For these reasons, LDF urges the Court to grant both

petitions for writ of certiorari.

Respectfully submitted,

Janell M. Byrd

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 682-1300

* Julius LeVonne Chambers

Charles Stephen Ralston

Norman J. Chachkin

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Counsel fo r Amicus Curiae

* Counsel o f Record

C (£cjZ -^Picl •

K f r n u

'1 ay.. <Y ^ d f ■

Wo . £ - f f 5 S 3

7 7 ? S'. 5 7 /

■ / ? H

7