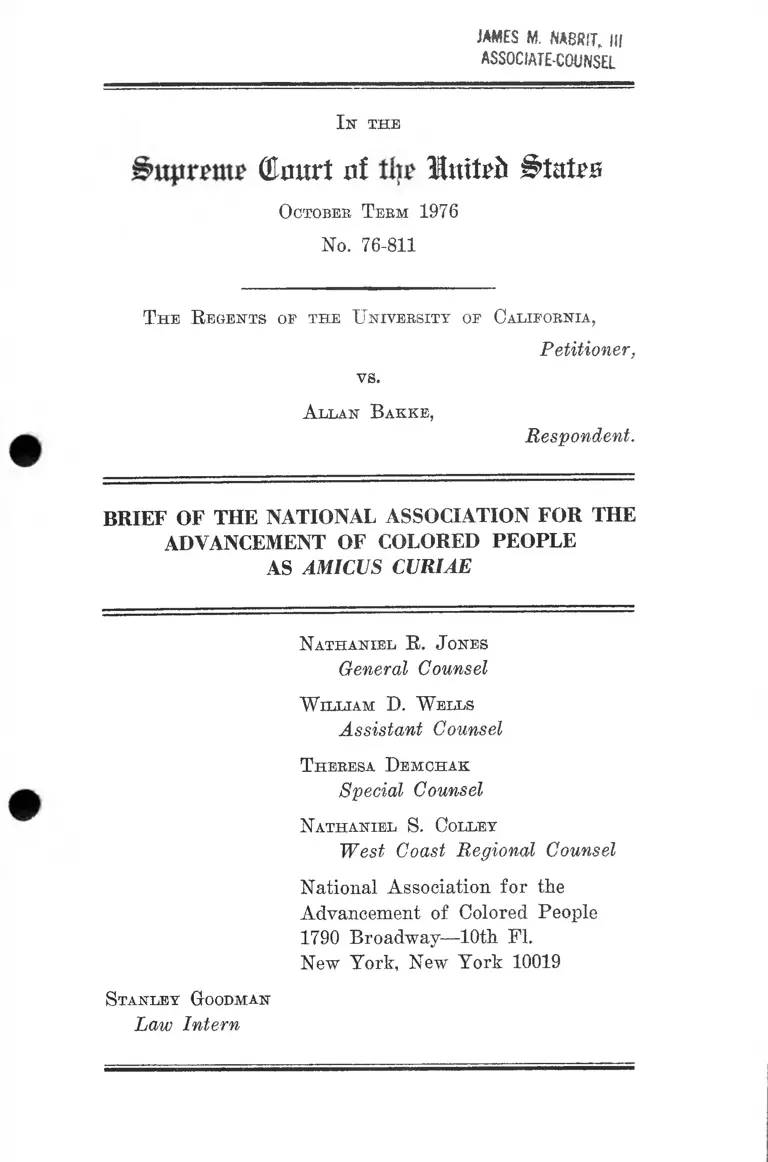

Bakke v. Regents Brief of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bakke v. Regents Brief of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People as Amicus Curiae, 1977. 758fb83b-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4df4d6ec-f823-443a-aed1-168d17733180/bakke-v-regents-brief-of-the-national-association-for-the-advancement-of-colored-people-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

JAMES M. NA8SIT, III

ASSOCIATE-COUNSEL

I k t h e

(Burnt af H&nitvb B u Xbb

O ctobeb T erm 1976

Mo. 76-811

T h e R eg en ts oe t h e U n iv ersity op Ca lifo rn ia ,

Petitioner,

vs.

A lla n B a k k e ,

Respondent.

BRIEF OF THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE

ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE

AS AMICUS CURIAE

N a t h a n ie l R. J ones

General Counsel

W illia m D. W ells

Assistant Counsel

T h eresa D e m c h a k

Special Counsel

N a t h a n ie l S. C olley

West Coast Regional Counsel

National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People

1790 Broadway—10th FI.

New York, New York 10019

S ta nley G oodman

Law Intern

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Interest of tlie Amicus .................................... ............. 1

Consent of the Parties ................................................. 2

Introduction and Summary of the Argument ............ 3

A rg u m en t

I. The Special Admissions Program Should Be

Upheld as a Permissible, Voluntary Effort

of the Davis Medical School to Desegregate

Its Institution ..................„........................... 5

A. The Federal Standard ................. ......... 5

B. Under Established Federal Law, The

California Regents Were Permitted to

Initiate Voluntary Methods of Desegre

gation to Eliminate Present Effects of

Past Discrimination ................................ 6

II. The Actions of the Regents Were Not Only

Permitted But Were Required Under Cali

fornia Law .................................................... 9

A. The Duty Owed ............... ................. ..... 9

B. The Method Chosen.................... :......... . 14

C. Summary ............................... ................. 18

III. The Use of Race Conscious Criteria For Ad

mitting Qualified Minority Applicants to

Scarce Educational Opportunities Is Not

Rendered Unconstitutional by the Absence

of a Judicial Finding of Past Discrimination 22

11

PAGE

IV. The Use of Race Conscious Selection Tech

niques For the Admission of Medical Stu

dents Is Authorized by Title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §2000d et seq.,

in the Circumstances of This Case ............. 25

C on clu sio n .............................. .................................... 34

T able oe Cases

Arvizu v. Waco Independent School District, 373 F.

Supp. 1264 (W.D. Tex. 1973), aff’d, 495 F.2d 499

(5th Cir. 1974) ....................... .................................17

Associated General Contractors of Massachusetts v.

Altshuler, 490 F.2d 9 (1st Cir. 1973), cert, den., 416

U.S. 957 (1974) ........................................................ 23

Beer v. United States, 425 U.S. 130 (1976) ................. 22

Bob Lo Excursions Co. v. Michigan, 333 U.S. 28 ...... 20

Booker v. Special School District #1, Minneapolis,

351 F. Supp. 799 (D.C. Minn. 1972) ...................... 17

Bradley v. Milliken, 484 F.2d 215 (6th Cir. 1973), aff’d

in part and rev’d in part, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) ___ 7

Briggs v. Elliot, 374 U.S. 483 (1954) ...... ..................... 5

Brinkman v. Gilligan, 539 F.2d 1084 (6th Cir. 1976),

cert, denied, 423 U.S. 1000 (1976) .......................... 7

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) .... 5

Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsylvania v.

Secretary of Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (3rd Cir. 1971),

cert, denied, 404 U.S. 854 (1971) ................ ........... 23

Crawford v. Board of Education of the City of Los

Angeles, 17 Cal. 3d 280, 130 Cal. Rptr. 724, 551 P.2d

28 (1976) ..................................................8,10,11,12,14

Ill

PAGE

Davis v. Baton Rouge Parish School District, 398 F.

Supp. 1013 (D.C. La. 1975) ..................................... 17

Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward, Vir

ginia, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) .............. ......................... 5

EEOC v. A.T.&T.,-----F.2d------ , 14 EPD Para. 7506

(3rd Cir. 1977) ................ -.... ............ ........................ 23

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747

(1976) ........................................................................ 22

Gebhart v. Belton, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ...................... 5

Goss v. Board of Education, Knoxville, 301 F.2d 164

(6th Cir. 1962), vacated, 373 U.S. 683 (1963) ...... 17

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968) .............................................. 9

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) ----- 31

Hart v. Community School Board of Education, N.Y.

School Dist. #2, 512 F.2d 37 (2nd Cir. 1975) .......... 17

Hills v. Gautreaux, 425 U.S. 284 (1976) ..................... 22

Jackson v. Pasadena City School District, 59 Cal, 2d

876, 31 Cal. Rptr. 606, 382 P.2d 878 (1963) ............. 9,11

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, 413 U.S. 189

(1973) ............. ..... .......................................... ........... 6,14

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974) .................... 20, 30? 33

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 317 F. Supp.

103 (M.D. Ala. 1970) .............................................. 17

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) .......... 22

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) ....................6,14

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U.S. 373 .......................... ..... 19

IV

PAGE

North Carolina Board of Education v. Swann, 402

U.S. 43 (1971) ................................................... 7,8,23,24

Oliver v. Kalamazoo, 508 F.2d 178 (6th Cir. 1974),

cert, denied, 421 U.S. 963 (1975) .................... ........ 7

People v. Superior Court, 38 Cal. App. 3d 966, 113

Cal. Rptr. 732 (Court of Appeals 1974) .... ............ 11,12

San Francisco Unified School District v. Johnson, 3

Cal. 3d 937, 92 Cal. Rptr. 309, 479 P.2d 669 (1971) .. 10

Santa Barbara School District v. Superior Court, 13

Cal. 3d 315, 118 Cal. Rptr. 637, 530 P.2d 605 (1976) .. 10

Serrano v. Priest, 5 Cal. 3d 584, 96 Cal. Rptr. 601, 486

P.2d 1241 (1971) ..................... ........... ........... ..........10-11

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966) .... 22

Southern Illinois Builders Association v. Ogilvie, 471

F.2d 680 (7th Cir. 1972) ........... ........... ................. 23

Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of Education, 311

F. Supp. 501 (C.D. Cal. 1970) ................ ............... 17

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) ........ ............................ .....6, 7, 8, 9, 22

United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh, Inc.

v. Carey,-----U.S.------, 45 U.S.L.W. 4221 (1977) ..22, 24

United States v. Montgomery County Board of Educa

tion, 395 U.S. 225 (1969) .......................................... 22

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) 24

V

PAGE

S tatutes and R egulations

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§2000(1 ............................................... 4, 5, 25, 26, 30, 31, 32

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§2000e .......................................................-...............30,31

45 C.F.R. §80 .... ..............................27,28,29,30,31,32,33

35 Fed. Reg. §1607 ......... ........................... -.......... -....... 31

1964 U.S. Code, Cong. & Admin. News ...................... 26, 27

R eports and A rticles

“Report of the Association of American Medical Col

leges Task Force to the Inter-Association Committee

on Expanding Educational Opportunities for Blacks

and Other Minority Students,” (Washington: As

sociation of American Medical Colleges, April 22,

1970) 32

I n t h e

g>itprpmp CHoxtrt of tlje Mnitefc S tates

O ctobeb T erm 1976

No. 76-811

T h e R eg en ts op t h e U n iversity op Califo rn ia ,

Petitioner,

vs.

A lla n B a k k e ,

Respondent.

BRIEF OF THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE

ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE

AS AMICUS CURIAE

Interest of the Amicus

The National Association for the Advancement of Col

ored People (NAACP) is a nonprofit membership asso

ciation representing the interests of approximately 500,000

members in 1800 branches throughout the United States.

Since 1909, the NAACP has sought through the courts to

establish and protect the civil rights of minority citizens.

In this respect, the NAACP has often appeared before

this Court as an amicus in cases involving employment,

voting rights, jury selection, capital punishment and other

cases involving civil rights. More frequently, however,

the NAACP has appeared here as counsel to parties in

school desegregation suits.

2

The present case is of particular interest to the NAACP

as it involves the review of a decision which, if affirmed,

will in all likelihood put an end to the recent efforts of

some institutions of higher learning to voluntarily and

effectively desegregate their facilities. At the very least,

affirmance would serve to discourage such efforts and will

deprive this nation of yet another generation of highly

educated, highly qualified minority professionals. The

NAACP has repeatedly appeared before Congress, suc

cessfully pleading the interests of its members for ob

taining sweeping legislation requiring the integration of

all publicly financed education facilities. Court-ordered

elimination of the affirmative action device chosen by the

Davis medical school on grounds that it violates the 14th

Amendment would render the efforts of the amicus and

the legislation obtained largely meaningless.

The true import of this case is that affirmance by the

Court will cast a direct burden upon the amicus and upon

other civil rights organizations who have chosen litigation

as our primary means of ending racial discrimination.

Frequently characterized as “private attorneys general,”

we have almost singlehandedly enforced the nation’s com

mitment to equal educational opportunities. An adverse

decision in this case will redouble our burden of litigation,

requiring us to seek in the courts what a growing number

of educational institutions have recently been willing to

accomplish voluntarily.

Consent of the Parties

With the consent of both parties pursuant to Rule 42

of the Supreme Court Rules, Amicus respectfully submits

this brief in support of the Petitioner, the Regents of the

University of California.

3

Introduction and Summary of the Argument

The most fundamental fact in this case is that if the

Davis medical school had adhered strictly to its regular

admissions program for the tilling of all available posi

tions, there would have been few, if any, black or Chicano

medical students admitted. Although there would have

been no dearth of perfectly qualified minority applicants,

they would have virtually all been screened out by the

regular admissions criteria. These criteria, admitting two

thirds of the students based upon a ranking of “bench

mark” scores and one third of the students based upon

such otherwise extraneous factors as marital status, loca

tion of intended medical practice, and “balance”,1 have

only a limited basis for predicting medical school per

formance for most students,2 and no basis for predicting

performance of minority students.3

Having the prescience to anticipate the absence of minor

ity students, the Regents approved a special admissions

program for admitting qualified students who were both

disadvantaged and of minority background. Sixteen per-

1 Only two out of three of the applicants offered admission

through the regular admission ranking process chose to attend the

Davis Medical School. The remaining students were selected from

the “alternate list” by the Dean of Admissions, which list was not

ranked according to numerical “qualifications.” Declaration of

George H. Lowery, p. 4.

2 Dr. Lowery stated that only one of the four scores obtained

on the Medical College Admissions Test was useful in predicting

academic performance during the first two years of medical school,

and that “there is not very much correlation beyond that.” Deposi

tion of George H. Lowery, CT-152.

3 Dr. Lowery stated that “quantifiable data, such as the test

scores and grades of applicants do not necessarily reflect the capa

bilities of disadvantaged persons.” Declaration of George H.

Lowery, p. 8.

4

cent of the available positions were reserved for these

applicants.

The California Supreme Court determined that the spe

cial admissions program, based in part on racial classi

fications, was invidious discrimination under the Four

teenth Amendment. Without reaching the question of

whether the program fulfilled compelling state interests,

the court below reasoned that there were less intrusive

alternatives available. The court suggested that the school

could expand its student capacity and that the admissions

process could become more subjective, embracing covert

decision making calculated to increase the proportion of

minority students regularly admitted.

The Amicus argues that it was not necessary to consider

whether there were less intrusive alternatives or whether

there was a compelling state interest, because the special

admissions device is a constitutionally permitted and

statutorily authorized device for ameliorating the racial

exclusion that would otherwise exist. Numerous decisions

of this Court interpreting the Fourteenth Amendment and

of the court below interpreting state lav/ warrant the

use of race conscious remedies to desegregate a public

educational institution. Through Title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 F.S.C. §2000d et seq., Congress has

required the desegregation of any institution receiving

federal financial assistance. The Department of Health,

Education and Welfare, exercising its statutory authority

to issue regulations under Title VI, has specified that race

conscious devices must be utilized to overcome the effects

of past racial exclusion, whether or not that past exclusion

was purposeful,4 Thus, the court below erred in its con-

4 In the trial court, both the Respondent in his complaint and

the Petitioner in its cross-complaint alleged Title VI as a juris

dictional basis. The trial court determined that the special ad-

5

sideration of the parameters of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, and the decision of the Supreme Court of Cali

fornia must be reversed.5

ARGUMENT

I.

The Special Admissions Program Should Be Upheld

as a Permissible, Voluntary Effort of the Davis Medical

School to Desegregate Its Institution.

A. The Federal Standard

Since its landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) this Court has consistently up

held the notion that:

. . . in the field of public education the doctrine of

“separate but equal” has no place. Separate educa

tional facilities are inherently unequal. Id. at 495.

While Brown and its companion cases6 dealt with specific

statutes which required or permitted the segregation by

missions program violated Title VI, but the issue was not discussed

by the Supreme Court of California. Although the record is tech

nically silent with respect to whether the D.avis Medical School

receives federal financial assistance and is therefore subject to

Title VI, the Court may take notice of the fact, may establish the

fact through questioning at oral argument, or may remand the

case for the limited purpose of making such a determination.

6 The Respondent, Allan Bakke, has not challenged the special

admissions program on the ground that a reservation of sixteen

percent or any other number is arbitrary or unreasonable, only

that it is per se unconstitutional. Although the Amicus fully con

cedes that the use of race, while permissible, is only a “starting

point” and cannot be arbitrarily or unreasonably used, the Court

need not reach the issue of whether it was so used in this case.

6 Briggs v. Elliott; Davis v. County School Board of Prince Ed

ward County, Va.; and Gebhart v. Belton, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

6

race of public school students, this Court has construed

the concept of de jure segregation to include situations

in which the actions and/or inactions of local and state

officials have had the foreseeable effect of creating, main

taining or perpetuating racial segregation within the

schools.7 Moreover, where school officials, through policies

and practices such as assignment patterns, site selections,

and the like incorporate within the schools the segregative

results of public and private residential discrimination,

such school officials become liable for the racial segrega

tion within the schools.8

As this Court noted in Sw ann v. Charlotte-M ecklenburg

Board o f Education, 402 U.S. 1, 16 (1971), before the

equity powers of the federal courts may be invoked to

provide relief to students attending segregated schools,

there must first be a showing of a constitutional violation:

.. . . . judicial powers may be exercised only on the basis

: of a constitutional violation . . . Judicial authority

enters only when local authority defaults.

B. Under Established Federal Law, The California Regents

W ere Perm itted to Initiate Voluntary Methods o f

D esegregation to Elim inate Present Effects o f Past

Discrim ination

In Sw ann, supra, this Court found the powers of school

officials to be plenary and held it to be within the broad

discretionary powers of school officials to conclude, as an

educational policy, that:

. . . to prepare students to live in a pluralistic society

each school should have a prescribed ratio of Negro

7 Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, 413 U.S. 189 (1973).

8 Keyes, supra; Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974).

7

to white students reflecting the proportion for the

district as a whole,9

In North Carolina Board of Education v. Swann, 402

U.S. 43, 45 (1971), decided on the same day as Swann v.

Charlotte-Mechlenburg, supra, this Court affirmed its find

ings with regard to the powers of school authorities and

further stated that such officials may conclude:

. . . that some kind of racial balance in the schools is

desirable quite apart from any constitutional require

ment.

Thus, although there must first be a constitutional viola

tion before a federal court may be called upon to order the

desegregation of schools and other public institutions,

school and other public officials may, within their plenary

powers, take it upon themselves to voluntarily desegregate

their institutions.

While this Court has never had occasion to determine

whether such voluntary desegregation plans as have been

adopted by school officials have been valid, both this Court

and lower federal courts have consistently held that the

recission of such voluntary desegregation plans by subse

quently elected or appointed school officials is, in and of

itself, a constitutional violation which warrants the inter

vention of the federal courts.10

In the action now before this Court, the Regents at

Davis acknowledged that the student enrollment at the

9 Id. at 16.

10 Brinkman v. Gilligan, 539 F.2d 1084 (6th Cir. 1976), cert,

denied 423 U.S. 1000 (1976) ; Bradley v. Milliken, 484 F.2d 215

(6th Cir. 1973) (en banc), aff’d in part and rev’d in part, 418

U.S. 717 (1974) ; Oliver v. Kalamazoo, 508 F.2d 178 (6th Cir.

1974), cert, denied, 421 U.S. 963 (1975).

8

school was almost exclusively white, and further, that this

segregated condition was likely to continue, absent their

intervention. In California, as in most other states, school

authorities have plenary powers over the operation of the

schools, including admissions and assignment powers.11

Before initiating the special admission program, the

Regents identified several factors which were contributing

to the segregated condition of the school’s enrollment. In

cluded among these factors was the use of quantitative

data in admissions determinations, which data the Regents

admitted did not truly measure the capabilities of minor

ities and other persons from disadvantaged backgrounds.

In initiating the special admission program, the Regents

were seeking to overcome the discriminatory results in

herent in the regular admissions program and to provide

minorities and other disadvantaged students with the op

portunity to compete on an equal basis with students in

the regular admissions program. A further stated purpose

of the special admissions program was to promote diver

sity within the student body and medical profession.12

It is thus clear that under the language of Swann v.

Charlotte-Mechlenburg, supra, and North Carolina Board

of Education v. Swann, supra, that while there has been no

judicial determination as to whether the Regents Avere con

stitutionally liable for the segregation at Davis prior to

the initiation of the special admission program, the Regents

were, in any event, permitted to voluntarily desegregate

their institution.

In determining methods by Avhich public officials may

desegregate their facilities, this Court has said:

11 See Crawford v. Board of Education of the City of Los

Angeles, 17 Cal.3d 280, 130 Cal. Rptr. 724, 551 P.2d 28 (1976).

12 Declaration of Dr. George H. Lowery, p. 7.

9

There is no universal answer to complex problems of

desegregation; there is obviously no one plan that will

do the job in every case. The matter must be assessed

in light of the circumstances present and the options

available in every instance.

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430, 439 (1968). Among the options available to state

officials in remedying segregation is the use of race

conscious criteria, as a starting point, in effecting a broader

remedial plan. As this Court has noted:

Awareness of the racial composition of the whole

school system is likely to be a useful starting point in

shaping a remedy to correct past constitutional viola

tions.

Swann v. Charlotte-Meclclenburg, 402 U.S. at 25,

The limited use of racial criteria, as one of a number of

considerations used in weighing the applications of dis

advantaged students seeking acceptance through the spe

cial admissions program, is a wholly permissible device for

desegregation.

II.

The Actions of the Regents Were Not Only Permitted,

But Were Required Under California Law.

A. The Duty Owed

Since at least 1963, public officials in California, includ

ing school authorities, have been required to eliminate

segregation within public institutions regardless of the

cause of such segregation. The elimination of the de jure/

de facto distinction in California was first set out in Jack-

son v. Pasadena City School Dist., 59 Cal. 2d 876, 880, 31

10

Cal. Rptr. 606, 608-609, 382 P.2d 878, 880 (1963), where the

State Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, declared

that:

[T]he segregation of school children into separate

schools because of their race, even though the physical

facilities and the method and quality of instruction in

the several schools may be equal, deprives the children

of the minority group of equal opportunities for ed

ucation and due process of law.

Jackson and its progeny have consistently held that minor

ity children suffer serious harm when their education takes

place in segregated public schools and that such harm is

equally present whether such segregation is de jure or

de facto in nature. Id. at 59 Cal.2d 876, 31 Cal. R p t r . 606,

383 P.2d 878; San Francisco Unified School District v.

Johnson, 3 Cal.3rd 937, 92 Cal. Rptr. 309, 479 P.2d 669

(1971); Santa Barbara Sch. Dist. v. Superior Court, 13

Cal.3rd 315, 118 Cal. Rptr. 637, 530 P.2d 605 (1975). In

Crawford v. Board of Education of the City of Los Ange

les, 17 Cal.3d 280, 130 Cal. Rptr. 724, 551 P.2d 28 (1976),

the California Supreme Court’s most recent decision in

this area, the Court stated that:

. . . the importance of adopting and implementing

policies which avoid “racially specific” harm to minor

ity groups takes on special constitutional significance

with respect to the field of education, because at least

in this state, education has been explicitly recognized

for equal protection purposes as a “fundamental in

terest.” 17 Cal.3d at 297, 130 Cal. Pptr. at 734-735, 551

P.2d at 38-39.

The Crawford Court then went on to quote from its de

cision in Serrano v. Priest, 5 Cal. 3d 584, 96 Cal. Rptr. 601,

11

486 P.2d 1241 (1971), where it had emphasized that the

“fundamental” nature of the right to an equal education

derives in large part from the crucial role that education

plays in “preserving an individual’s opportunity to com

pete successfully in the economic market-place, despite a

disadvantaged background . . . [T]he public schools of

this state are the bright hope for entry of the poor and

oppressed into the mainstream of American Society.” 5

Cal. 3d at 609, 96 Cal. Rptr. at 619, 487 P.2d at 1259. Thus,

based upon its previous holdings in Jackson and Serrano,

the California Supreme Court in Crawford held that:

Given the fundamental importance of education, par

ticularly to minority children, and the distinctive ra

cial harm traditionally inflicted by segregated educa

tion, a school board bears an obligation under article

1, section 7, subdivision (a) of the California Constitu

tion, mandating the equal protection of the laws, to

attempt to alleviate segregated education and its harm

ful consequences, even if such segregation results

from the application of a facially neutral state policy.

17 Cal.3d at 297, 130 Cal. Rptr. at 735, 551 P.2d at 39.

While Jackson and Crawford dealt with the obligations

of school districts, those holdings have been expanded to

impose upon other California public officials in some cir

cumstances an affirmative obligation to design programs

or frame policies so as to avoid discriminatory results.

17 Cal.3d at 296-297, 130 Cal. Rptr. at 734, 551 P.2d at 38.

See also, People v. Superior Court, 38 Cal. App. 3rd 966,

113 Cal. Rptr. 732 (Court of Appeals 1974).

From this brief discussion of California law, several

points become clear. First, as a predicate for liability, the

de jure/de facto distinction has been abandoned in Cal

ifornia. Consequently, a finding of past racially discrimina-

12

tory action is not necessary for the assumption of an

affirmative duty by public officials to eliminate segregation

within public institutions in the State. As the Court in

Crawford found:

. . . local school boards are “so significantly in

volved” in the control, maintenance and ongoing super

vision of their school systems as to render any exist

ing school segregation “state action” under our state

constitution equal protection clause.

17 Cal.3d at 294, 130 Cal. Rptr. at 732, 551 P.2d at 36.

Secondly, public officials in California have been held,

in numerous circumstances, to be under an affirmative duty

to eliminate segregation within their respective institu

tions. Thus, these officials must do more than merely ab

stain from intentional discrimination. 38 Cal. App. 3rd

966, 972, 113 Cal. Rptr. 732, 736. School officials in Cal

ifornia have repeatedly been held to bear a constitutional

obligation to take reasonable, feasible steps to alleviate

school segregation regardless of its cause. Similarly, offi

cials charged with formulating a panel for a grand jury

selections have been found to :

. . . have an affirmative duty to develop and pursue

procedures aimed at achieving a fair cross-section

of the community. Id.

Third, to the extent that education is a “fundamental

interest” in California, it would logically follow that school

officials at all levels, i.e., elementary, secondary, college,

and post-graduate, bear the same affirmative obligation to

assure that equal opportunities exist within public educa

tional facilities.

Finally, and most significantly in relation to the case

now before this Court, the California Supreme Court has

13

repeatedly interpreted the State’s equal protection clause

as guaranteeing to minorities and other victims of past

discrimination the right to equal opportunities and access

to public institutions in California. Applying these prin

ciples to the case at bar, it is clear that the Regents’

actions were mandated by state law.

Having concluded that their 1968 and 1969 admissions

policies were resulting in an almost exclusively white

institution, and further concluding that such policies were

not providing to minorities and other disadvantaged stu

dents, equal opportunities for access to the medical school

at Davis, the Regents were not only permitted under Cal

ifornia law, but were required to take affirmative steps to

alleviate such conditions. The record below clearly indi

cates that the regular admissions policy serves to eliminate

virtually all otherwise qualified minority applicants from

admission to the School of Medicine. The record further

establishes that in the opinion of the Chairman of the

Admission Committee, such a condition was likely to con

tinue under the then-existing admissions policy.13

Having acknowledged the segregated condition of the

school, it was not necessary, under California law, for the

Regents to make an inquiry into the causes of such segre

gation. Clearly, under established case law of the state,

the Regents bore an affirmative obligation to alleviate the

segregation existing at Davis, regardless of the cause. It

should be noted, however, that even though a finding of

“state action” was not necessary before a duty to act was

imposed upon the Regents, the record clearly establishes

that the segregation at Davis in 1969 was not adventitious.

Such a condition was clearly the result of specific policies

of the university. While not specifically denying admission

18 Declaration of Dr. George H. Lowery, pp. 7-8

14

to minorities and other disadvantaged individuals, the ad

mission criteria prior to the special admission program had

an admittedly racially discriminatory effect. As Dr. Low

ery stated in his Declaration:

Another reason special consideration may need to be

given to minorities is that quantifiable data, such as

the test scores and grades of applicants do not neces

sarily reflect the capabilities of disadvantaged per

sons.14

The use of the regular admission criteria and its effect

upon minority and other disadvantaged applicants may be

likened to the practice of school authorities in drawing

school attendance zones and making student assignments.

While such policies may, on their face, appear to be neutral,

where the result is to incorporate and build upon residen

tial segregation caused by public and private discrimina

tion, racial neutrality is lost and such segregatory prac

tices become illegal state action. Keyes, supra; Bradley,

supra; Crawford, supra. Likewise, where university officials

adhere to an admission policy which they acknowledge

does not truly measure the capabilities of minority and

other disadvantaged students, such officials are no longer

free to continue to follow such policies, but must take

affirmative steps to alleviate the segregatory results

thereof.

B. The Method Chosen

School official have considerable discretion in devising

method to eliminate segregation within California schools.

As the California Supreme Court recently stated in Craw

ford v. City School District of Los Angeles, supra at 17

Cal.3d at 305-306, 130 Cal. Rptr. at 724, 551 P.2d 45:

14 Declaration of Dr. George H. Lowery, p. 8.

15

. . . so long as a local school board initiates and imple

ments reasonably feasible steps to alleviate school

segregation in its district, and so long as such steps

produce meaningful progress in the alleviation of such

segregation and its harmful effects, we do not believe

the judiciary should intervene in the desegregation

process. Under such circumstances, a court thus should

not step in even if it believes that alternative desegre

gation techniques may produce more rapid desegrega

tion in the school district . . . In our view, reliance

on the judgment of local school boards in choosing

between alternative desegregation strategies holds so

ciety’s best hope for the formulation of desegregation

plans which will actually achieve the ultimate constitu

tional objective of providing minority students with

the equal opportunities potentially available from an

integrated education.

The formulation of desegregation plans and programs do,

by necessity, involve the use of race conscious criteria, and

such criteria have been approved as a starting point by

both California courts and this Court. Swann, supra;

Keyes, supra; Crawford, supra.

It is indeed ironic that the same Court which, over

seventeen years ago, abolished the de jure/de facto dis

tinction as a requisite for the desegregation of its public

school facilities, and six years ago declared that education

in California was a “fundamental interest,” would strike

down the special admission program, as implemented at

Davis, as unconstitutional. Such a decision is clearly not

consistent with a long line of cases previously decided by

the California Supreme Court. The Court below attempts

to distinguish Bahhe from its previous holdings in several

ways. First, the Court found that absent any showing of

past discrimination, any preferential treatment of minori

ties and other disadvantaged individuals is invalid. Yet,

as already discussed, the California Supreme Court has

long held that no showing of discriminatory or de jure

action is necessary before public officials come under an

affirmative duty to eliminate the segregation existing with

in their respective institutions. Crawford, supra. More

over, the racially discriminatory results of the regular

admission policy were not only shown in the record below,

but were admitted by the Regents. Thus, as already noted

above, not only were the Regents permitted to initiate a

voluntary desegregation program, they were required to

do so under the law of the State.

A second objection of the Court belowT was that the spe

cial admission program served to totally deprive Bakke of

a medical school education solely because of his race. It

is on this basis that the California Supreme Court distin

guishes Bakke from school desegregation litigation. The

distinction, according to the Court, is that in a school de

segregation remedy, no child is absolutely deprived of an

education, while that is exactly the loss suffered by Bakke

as a result of the actions of the Regents. It can only be

said that in finding that Bakke or any other medical school

applicant has an absolute right to attend medical school,

the California court erred. While education is a “funda

mental interest” in California, no state court has yet inter

preted such an interest to include an absolute right to

attend medical school. Additionally, while the Court below

states that no student attending schools in a system under

going desegregation is precluded from attending school,

the Court fails to note that such attendance, until a mini

mum age, is compulsory under state law. Moreover, Bakke

was in no way absolutely deprived of a right to attend medi

cal school by the actions of the Regents; rather, he was

17

only precluded from attending Davis, beeause lie did not

meet the admissions criteria.

As the California courts, as well as this Court, have

held on numerous occasions, many remedies in a desegre

gation plan may be exclusionary. For example, and as

was noted in the dissent below, magnet schools have been

upheld as valid desegregative tools.15 To be effective, how

ever, these schools have to have controlled admissions pol

icies to insure that the student population of the school

will not become one-race, thus defeating the desegregative

objective. The “magnets” used to attract students to these

schools are usually specialized or unique programs or

courses not offered in other schools in the district. Thus,

a student who is precluded from attending a particular

magnet school because his or her attendance there will

negatively effect the desegregation of the school, suffers

the same loss as Bakke, i.e., the “right” to attend a school

of one’s choice.

Controlled transfers are also incorporated, in many in

stances, in desegregation plans.16 Under this type of

transfer, a student wishing to transfer to a particular

school may do so only if such a transfer will promote de~

16 See, 18 Cal.3d at 73, 132 Cal. Rptr. at 707, 553 P.2d at 1179-

1180 (Dissent) ; Hart v. Comm,. School Board of Ed. N.T. Sch. Dist.

# 2 , 512 F. 2d 37, 42-43, 54-55 (2nd Cir. 1975); Spangler v.

Pasadena City Bd. of Ed., 311 F.Supp. 501, 519 (C.D. Cal. 1970) ;

Goss v. Bd. of Ed. of Knoxville, 301 F.2d 164, 168 (6th Cir. 1962),

vacated on other grds, 373 IT.S. 683 (1963); Lee v. Macon County

Bd. of Ed., 317 F. Supp. 103 (M.D, Ala. 1970) (three-judge court) ;

Arvizu v. Waco Independent Sch. Dist., 373 F.Supp. 1264 (W.D.

Tex. 1973), aff’d in part, revised as to other issues, 495 F.2d 499

(5th Cir. 1974) ; Booker v. Special School Dist., # 1 , Minneapolis,

351 F.Supp. 799 (D. Minn. 1972); Davis v. Baton Rouge Parish

School Bd., 398 F.Supp. 1013 (D.La. 1975).

16 Cases cited note 15, supra.

segregation. That student, as Bakke, is denied attendance

at a school of his or her choice because of race. Such

controlled transfers likewise have been upheld by numerous

courts as valid desegregation components.17 Therefore,

the proposition that one may he excluded from the school

of his choice on account of his race, in the context of a

valid desegregation plan, is not new in the law. As a re

sult, Mr. Bakke has suffered no constitutionally cogniz

able harm.

C. Summary

The decision reached in the Court below is inconsistent

with a long line of decisions of the same Court involving

school desegregation. In California, public officials, includ

ing school officials, have been since at least 1963, under

an affirmative duty to alleviate racial segregation in their

institutions regardless of the causes of such segregation.

Moreover, while education has been declared to be a funda

mental interest in California, no court in that state has

interpreted the principle as providing every individual in

the state the right to attend medical school. Indeed the

fundamental interest in education to be protected is that

minorities be afforded equal opportunities and access to

integrated educational facilities in the State.

In section I-B and II A-B of the Argument portion of

this Brief, pages 6-18, there is an extended discussion of

the question of how the California Supreme Court has

interpreted that state’s constitution. Under ordinary cir

cumstances, such would be inappropriate here because this

court only becomes involved when such an interpretation

runs afoul of the Supremacy Clause of the United States

Constitution. However, the discussion becomes essential

because the California Supreme Court in effect held that

17 Cases cited note 15, swpra.

19

the 14th Amendment prohibits the regents of the univer

sity from doing that which state law clearly requires.

As we have shown, neither the due process nor the equal

protection clause of the 14th Amendment contains any

such prohibition.

The nobility of purpose behind the adoption of the

special admissions program is conceded by all. That pur

pose was to guarantee that from a large pool of appli

cants, each of whom was wholly and fully qualified to

pursue medical studies, and predictably, to perform satis

factorily in the medical profession, at least a few would

be from ethnic minority groups. This is not the case in

which a qualified white person was rejected, while an

unqualified ethnic minority person was accepted. Here,

the 16 ethnic minority students were in every way qual

ified as university medical students. Thus, the question,

on a policy basis, is reduced to whether a court or the

university should determine priority in the acceptance of

students from the pool of qualified applicants. In a con

stitutional sense, the question is whether the 14th Amend

ment somehow dictates the order in which qualified ap

plicants must be admitted to a state university’s medical

school.

If the purpose of the special admissions program had

been to exclude white persons from the medical school

we would be the first to concede that it could not survive

the strict scrutiny to which such racial classifications are

traditionally subjected. Where, however, as here, the clear

and express intent is to effectuate the original purpose

of the 14th Amendment, the situation is vastly different.

Proof that the same test is not applied in all situations

is demonstrated by a comparison of two cases. In Morgan

v. Virginia, 328 U.S. 373, a Yirgina statute which re-

20

quired racial segregation in interstate commerce was in

validated under the commerce clause. In Bob Lo Excur

sion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U.S. 28, however, a Michigan

statute was upheld under the same clause. Both affected

interstate commerce, but the purpose of one was to re

quire segregation, while that of the other was to prevent

it. The difference in purpose was crucial.

In a number of recent cases this Court has weighed

heavily the intent involved in state action under a 14th

Amendment challenge. Such action has usually passed

constitutional muster when the purpose was not to dis

criminate because of race or color, even though such dis

crimination may well have been an incidental result of

the protested action. These cases recognize that in an

immensely complicated society the vast complexities in

volved in competing claims preempt any reasonable pos

sibility that any affirmative action effort, no matter how

great the need or just the cause, will function without

incidental disadvantage to someone. Yet, this fact of

life need not render a great university impotent to deal

with the urgent task of bringing meaningful equality of

opportunity to its constituency.

When we use the phrase “meaningful equality of op

portunity” we imply an opportunity of which a person

may take advantage. That is the meaning this Court gave

the phrase in Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974). There,

pupils of Chinese decent admittedly had a theoretical

equality of opportunity to attend the public schools of

San Francisco. That, however, was not enough. It was

held that steps had to be taken to remove language bar

riers so that these pupils could take advantage of the

theoretical equal opportunity.

Here, we admit that from the outset all ethnic minor

ities had a theoretical equality of opportunity to attend

21

the medical school at Davis. What happened was that

the university itself found that for number of reasons

unrelated to one’s ability to perform in school or in the

profession certain ethnic minorities were being excluded.

The special admissions program had as its sole purpose

the correction of that situation. It was an effort to make

the theoretical right to enter that medical school a mean

ingful reality for those for whom it had previously been

only a dream.

In its decision the California Supreme Court completely

overlooked the original purpose of the 14th Amendment.

Though much debate has been engaged in over the years,

there is now a general consensus that the 14th Amend

ment was originally a measure designed to facilitate the

movement of former slaves into the mainstream of Amer

ican life. Graham, Howard J., “Everyman’s Constitution”,

State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1968.

Congressional debates during the adoption of that

amendment fully substantiates the foregoing determina

tion of purpose. While we recognize the obvious fact that

the benefits of equal protection and due process are the

just due of all Americans of every race or color, we flatly

assert that it is an outright perversion of the original

intent of that sacred document to hold that, as a matter of

law, it must now be altered from a shield for the pro

tection of black people seeking entry into the mainstream

of American life, into a sword for use in cutting off their

legitimate hopes and aspirations to become professionals

also, and not merely hewers of wood and drawers of water

for a white society.

22

III.

The Use of Race Conscious Criteria For Admitting

Qualified Minority Applicants to Scarce Educational

Opportunities Is Not Rendered Unconstitutional by the

Absence of a Judicial Finding of Past Discrimination.

The power of the federal judiciary to order race con

scious remedies where past statutory or constitutional vio

lations have been found has been firmly established, for

it is precisely that finding of past illegal conduct which

confers such jurisdiction upon the courts. Swann v. Char-

lotte-MecMenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971);

United States v. Montgomery County Board of Education,

395 U.S. 225 (1969); Hills v. Gautreaux, 425 U.S. 284

(1976); Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S.

747 (1976); Beer v. United States, 425 U.S. 130 (1976);

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966); United

Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh, Inc. v. Carey,

----- U.S. ----- , 45 U.S.L.W. 4221 (1977). Indeed, upon

a finding of illegal racial discrimination, it has been held

that, “the court has not merely the power but the duty

to render a decree which will so far as possible eliminate

the discriminatory effects of the past as well as bar like

discrimination in the future.” Louisiana v. United States,

380 U.S. 145, 154 (1965).

This Court has recently held that the constitution does

not require absolute color-blindness on the part of state

officials in establishing electoral districts, but rather that

they are permitted, even in the absence of a finding of past

discriminatory conduct, to focus entirely upon race and

ethnicity in their decisionmaking. United Jewish Organi

zations of Williamsburgh, Inc. v. Carey, supra. The Carey

case was not the first instance in which the Court has

23

enunciated this principle. In North Carolina Board of

Education v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43 (1971), the Court was

presented with a statute requiring absolute color-blind

ness in assigning school children to schools, specifically

prohibiting racial assignments “for the purpose of creat

ing a balance or ratio of race, religion or national origins.”

Id. at 44, n. 1. The Court struck the statute down, com

menting that the “apparently neutral form” of the statute

“against the background of segregation, would render il

lusory the promise of Brown v. Board of Education . .

Id. at 45-46. The Court held that while the Constitution

does not prescribe any particular racial mix or balance,

state officials are permitted wide latitude to take race

into account as a “starting point” in achieving a racial

balance in the schools.

This principle of approving officially sanctioned, race

conscious decisionmaking where past exclusion has been

found by state or federal officials has been applied as

well in the lower courts. In Southern Illinois Builders

Association v. Ogilvie, 471 F.2d 680 (7th Cir. 1972), and

Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsylvania v. Sec

retary of Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (3rd Cir. 1971), cert, denied,

404 U.S. 854 (1971), the use of race in the allocation of

future employment opportunities was permitted in the ab

sence of a judicial finding of past discrimination. In As

sociated General Contractors of Massachusetts v. A ltshuler,

490 F.2d 9 (1st Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 416 U.S. 957 (1974),

the Circuit Court approved the use of race conscious cri

teria imposed by state authorities which exceeded in

scope the applicable federal regulations promulgated pur

suant to an executive order. Recently, in EEOC v. A.T.ST.,

■----- F.2d ----- , 14 EPD Para. 7506 (3rd Cir. 1977), the

Court upheld the use of race in making promotions where

it was required by a Consent Decree.

24

On the record of the present case before the Court, the

Regents of the University of California made an emperical

determination that the Davis Medical School would remain

a white enclave unless racial or ethnic factors were taken

into account in the admissions process. Its past conduct

in 1968 and 1969 may not have resulted in a violation of

the Fourteenth Amendment as articulated in Washington

v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976), hut once realizing the

ethnic impact and lack of utility of the selection criteria,

its continued use of those criteria may well have met

the standards articulated. In any event it is not neces

sary for the Medical school to have engaged in uncon

stitutional conduct before it is permitted to take steps

to prevent such conduct from occurring in the fu

ture. As this Court has repeatedly explained, the per

missive scope of the Fourteenth Amendment is much

broader when applied to state officials attempting to in

tegrate a school or an electoral district than it is with

respect to a federal court imposing a remedy for past

unconstitutional conduct. North Carolina Board of Edu

cation v. Swann, supra; United Jewish Organisations of

Williamsburgh, Inc. v. Carey, supra. The decision of the

California Supreme Court requiring color-blind decisions

and prohibiting efforts to achieve racial balance would

have the same effect as the statute struck down in the

Swann companion case. Consequently, it must be reversed.

25

IV.

The Use of Race Conscious Selection Techniques For

the Admission of Medical Students Is Authorized by

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§2000d et seq., in the Circumstances of This Case.

As part of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Congress enacted

Title VI prohibiting discrimination on account of race, color

or national origin in the exclusion of persons from par

ticipation in any program or activity receiving Federal as

sistance.18 Enforcement responsibility was given to those

Federal agencies which extend financial assistance, and

with the approval of the President, they were empowered

to issue rules, regulations or orders of general applica

bility to achieve the objectives of the statute.19

The legislative history of Title VI clearly indicates that

the purpose of the statute was to accomplish racial and

ethnic integration of federally financed facilities as quickly

as possible, relying heavily on the encouragement of volun-

18 Section 601 of Title VI provides:

No person in the United States shall, on the ground of race,

color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in,

be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination

under any program or activity receiving Federal financial

assistance.

19 Section 602 of Title VI provides, in p a r t :

Bach Federal department and agency which is empowered to

extend Federal financial assistance to any program or activity,

by way of grant, loan, or contract other than a contract of

insurance or guaranty, is authorized and directed to effectuate

the provisions of section 2000d of this title with respect to

such program or activity by issuing rules, regulations, or or

ders of general applicability which shall be consistent with

achievement of the objectives of the statute authorizing the

financial assistance in connection with which the action is

taken.

26

tary compliance. The House Report accompanying H.R.

7152 noted that continued discrimination against Negroes

was the “most glaring” problem to be addressed, and that

while voluntary progress had been made on the State and

local level, “it has become increasingly clear that progress

has been too slow.” House Report No. 914, 1964 TJ.S.

Code, Cong, and Admin. NewTs, p. 2393. Specifically dis

cussing Title VI, the House report stated that federal

agencies could utilize the termination of financial assistance

as well as “any other means authorized by law” in enforc

ing the statute. Id. at 2401. Congressional proponents of

the bill recognized its applicability to increasing the rate

of entrance of Negroes into medical schools,20 and oppo

nents shared this recognition, stating in addition their

concern for an expansive definition of “discrimination” as

well as the burden which minority rights would cast upon

the rights which the majority had always enjoyed.21

20 Seven Representatives submitted a joint statement of support

for H.R. 7152 which accompanied the House Report. Their com

mentary stated:

“Negro patients are denied access to hospitals or are segregated

within such facilities. Negro doctors are denied staff privileges

—thereby precluding them from properly caring for their

patients. Qualified Negro nurses, medical technicians, and

other health personnel are discriminated against in employ

ment opportunities. The result is that the health standards

for Negroes to become doctors or to remain in many commu

nities, after gaining a medical education, is reduced. . . . Re

grettable as it may seem, a number of universities and other

recipients of these grants continue to segregate their facilities

to the detriment of Negro education and the Nation’s welfare.”

(Emphasis added) Additional Views on H.R. 7152 of Hon.

William M. McCullouch, Hon. John V. Lindsay, Hon. William

T. Cahill, Hon. Garner E. Shriver, Hon. Clark MacGregor,

Hon. Charles McC. Mathias, and Hon. James E. Bromwell,

1964 U.S. Code Cong, and Admin. News, p. 2511.

21 The Minority Report accompanying H.R. 7152, characterizing

the entire bill as “the greatest grasp for executive power conceived

in the 20th century,” pointed out that “The right of boards of

27

Exercising the authority granted by Section 602 of Title

VI, the Department of Health, Education and Welfare

(hereafter, HEW) has published regulations effectuating

its obligations under the statute and giving some guidance

to financial recipients with respect to the kinds of dis

crimination prohibited under the Act. The guidelines in

effect in 1969, for example, prohibited discrimination in

the provision of training or other services provided by

recipients of federal support.22 The guidelines specifically

applied to the admissions practices of institutions of

higher learning,23 and the concept of racial or other dis-

trustees of public and private schools and colleges to determine

the handling of students and teaching staffs” would be seriously

impaired by Title V i’s strictures. Minority Report Upon Proposed

Civil Rights A ct of 1963, Committee on Judiciary Substitute for

H.R. 7152, 1964 U.S. Code, Cong, and Admin. News, p. 2433. The

Minority Report of the House Judiciary Committee also expressed

great concern that the concept of discrimination was not defined

in the bill and that the concept of “racial imbalance” would be

come a controlling factor in defining discrimination. I d . at 2436.

The Report additionally expressed concern that the granting of

rights under the Civil Rights Act may curtail some of the advan

tages which the majority had always enjoyed:

“In determining whether this bill should be adopted, it must

be remembered that when legislation is enacted designed to

benefit one segment or class of a society, the usual result is

the destruction of coexisting rights of the remainder of that

society. One freedom is destroyed by governmental action to

enforce another freedom. The governmental restraint of one

individual at the behest of another implies necessarily the

restriction of the civil liberties and the destruction of civil

rights of the one for the benefit of the other. . . .” Id . at 2437.

22 45 C.P.R. §80.3(a) (1969) stated:

“No person in the United States shall, on the ground of race,

color, or national origin be excluded from participation in,

be denied the benefits of, or be otherwise subjected to dis

crimination under any program to which this part applies.”

23 45 C.P.R. §80.4(d) (1) stated:

“In the case of any application for Federal financial assistance

to an institution of higher education . . ., the assurance re-

28

crimination was referred to broadly as the utilization of

any criteria which has the effect of excluding persons on

account of race or which otherwise has the effect of de

feating the objectives of the program.24

The regulations were republished each year essentially

unchanged until 1973, when provisions were added to place

an affirmative obligation upon recipients to correct the

effects of past racial or ethnic exclusion, regardless of

whether the recipient considered the past exclusion to

have been discriminatory. From that year to date, re

cipients were instructed that they “must take affirmative

action to overcome the effects of prior discrimination” and

that they “may take affirmative action to overcome the

effects of conditions which resulted in limiting partieipa-

quired by this section shall extend to admission practices and

to all other practices relating to the treatment of students.”

Appendix A to the regulations listed the types of programs to

which the regulations applied, and included were a variety of

grants for health and medical services, including teaching facilities

for medical, dental, and other health personnel.

24 45 C.F.R. §80.3(b )(2 ) stated:

“A recipient . . . may not, directly or through contractual or

other arrangements, utilize criteria or methods of administra

tion which have the effect of subjecting individuals to dis

crimination because of their race, color, or national origin,

or have the effect of defeating or substantially impairing

accomplishment of the objectives of the program as respects

individuals of a particular race, color or national origin.”

In the illustrative applications included in the regulations, ex

clusion accomplished indirectly through the use of criteria having

a disparate impact upon racial or ethnic groups were described:

“A recipient may not take action that is calculated to bring

about indirectly what this part forbids it to accomplish di

rectly. Thus a State, in selecting or approving projects . . .

may not base its selections or approvals on criteria which have

the effect of defeating or of substantially impairing accom

plishment of the objectives of the Federal assistance program

as respects individuals of a particular race, color, or national

origin.” 45 C.F.R. §80.5 (h).

29

tion by persons of a particular race, color, or national

origin.” 26 Illustrative applications of these two new sec

tions describe in some detail the affirmative obligations to

correct for past exclusion, and the use of race or ethnicity

as a corrective factor granting “special consideration” is

specifically approved by HEW.26

26 45 C.F.R. §80.3(6) was added to the regulations stating:

“ (i) In administering a program regarding which the recipient

has previously discriminated against persons on the ground

of race, color, or national origin, the recipient must take affir

mative action to overcome the effects of prior discrimination,

“ (ii) Even in the absence of such prior discrimination, a re

cipient in administering a program may take affirmative action

to overcome the effects of conditions which resulted in limiting

participation by persons of a particular race, color, or national

origin.”

26 45 C.F.R. §80.5(i) and (j) were added, stating:

“ (i) In some situations, even though past discriminatory prac

tices attributable to a recipient or applicant have been aban

doned, the consequences of such practices continue to impede

the full availability of a benefit. I f the efforts required of

the applicant or recipient under §80.6 (d) . . . have failed to

overcome these consequences, it will become necessary under

the requirement stated in (i) of §80.3 (b) (6) for such ap

plicant or recipient to take additional steps to make the bene

fits fully available to racial and nationality groups previously

subject to discrimination. This action might take the form,

for example, of special arrangements for obtaining referrals

or making selections which will insure that groups previously

subjected to discrimination are adequately served.

“ (j) Even though an applicant or recipient has never used

discriminatory policies, the services and benefits of the pro

gram or activity it administers may not in fact be equally

available to some racial or nationality groups. In such cir

cumstances, an applicant or recipient may properly give spe

cial consideration to race, color, or national origin to make

the benefits of its program more widely available to such

groups, not then being adequately served. For example, where

a university is not adequately 'serving members of a particular

racial or nationality group, it may establish special recruit

ment policies to make its program better known and more

readily available to such group, and take other steps to provide

that group with more adequate service.”

30

Title VI, like its legislative companion in the 1964 Civil

Rights Act, Title VII, therefore was enacted with a

broadly stated prohibition on discrimination. Congress

relied upon administering agencies such as HEW to define

discrimination and develop the mechanics of enforcement

through regulation. Until 1973, HEW’s regulations did not

contain references to remedial steps necessary to cure past

exclusion of protected racial or ethnic groups, but they

clearly established the “effects test” for defining what is

and what is not a discriminatory practice under the stat

ute. Since 1973, HEW’s regulations have left no doubt

that in the distribution of federally financed programs

and services, any criteria applied to exclude beneficiaries

which has the effect of disproportionately excluding an

identifiable racial or ethnic group is prohibited. Whether

this exclusion has taken place in the past on account of

purposeful discrimination or whether it has simply oc

curred unintended is of limited distinction,27 the regula

tions require corrective measures including race conscious

decisions designed to include the groups previously ex

cluded.

In Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974), the Court applied

Title VI, as given substance by HEW’s regulations, to

prohibit the exclusion of Chinese-speaking minorities in

San Francisco from receiving a meaningful, federally

financed education. Applying the agency’s regulations to

the exclusionary language barrier, the Court stated that,

“Discrimination is barred which has that effect even though

27 C.F.R. §80.5 (i) states that “it will become necessary” to take

corrective measures where past discrimination has existed, while

subsection (j ) states that such steps “may” be taken in the absence

of past discrimination. It is significant to note, however, that sub

section (j) , applying as it does to situations lacking a history of

discrimination, is the more specific of the two subsections in terms

of approving race conscious decisionmaking in the future to cor

rect the effects of the past.

31

no purposeful design is present . . . ” Id. at 568. Thus,

the Court has upheld HEW’s interpretation of what is

prohibited by Title VI, adopting an “effects test” some

what analogous to that held applicable to Title VII.28

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971).

Although the Supreme Court of California refrained

from reviewing the trial court’s decision as it was based

in part upon Title VI, it is clear that the statute applied

to the conduct of the Davis medical school and that any

evaluation of Davis’ special admissions program must in

clude the school’s Title VI obligations.

Utilization of the school’s traditional entrance criteria—

an amalgam of grade point averages, Medical College Ad

missions Test scores and interview performance29—have

had a sharp exclusionary effect on identifiable minority

racial and ethnic groups since the opening of the school.

During the years 1968, and 1970-1974, a total of 429 stu-

28 Title VI and the implementing HEW regulations are actually

much broader than the Guidelines on Employee Selection Proce

dures published by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commis

sion under Title VII, 35 F.R. 1607 et seq. (1970). HEW regula

tions yui’rently provide that if the application of a particular

criteria or standard has resulted in disproportionate exchision,

remedial steps are to be taken. EEOC Guidelines, however, provide

that if an employment standard or criteria has a disproportionate

effect, it may continue to be utilized despite that effect if the

standard or criteria has validity as defined in the Guidelines.

29 The regular admissions criteria as described in the opinion

below were not always controlling, and variances were made from

the “benchmark” ratings of candidates. Dr. Lowery, the admis

sions officer, had the authority to override the committee selection

process when some other factor such as a particularly strong recom

mendation or a candidate’s marital circumstances so persuaded

him. Deposition of George H. Lowery, CT-183. The California

Supreme Court^ acknowledged that the alternate list of regular

admissions applicants, used for selection of slots which first-round

offerees refused, was not formulated in order of “benchmark”

ratings. ̂533 P.2d 1158. Selection from this alternate list was made

at the discretion of the dean of admissions. D i d .

32

dents were admitted through the regular admissions pro

gram. Only one of these admittees was black and 6 were

Chieanos. State officials responsible for determining ad

missions criteria could well he justified in determining, as

they in fact did determine, that exclusive reliance upon

traditional entrance standards would produce few, if any,

minority medical students.30 This realization, based upon

emperical data and without any further considerations,

would stand the school in violation of 45 C.F.R. §80.3 (b)

(2), particularly as illustrated in §80.5 (h), and subject it

to a potential loss of federal assistance or litigation. By

1973, when the statistical pattern of ethnic exclusion was

well entrenched in the regular admissions program, and

in addition when 45 C.F.R. §80.3(6) (i) and (ii) and §80.5

(i) and (j) were added to the HEW regulations, there

could be no doubt that a race conscious ameliorative device

was not only authorized but required by Title VI.

The Davis medical school’s response to the disappoint

ing absence of minority students was the implementation

of its special admissions program—in effect, a reservation

of 16 percent of available positions for applicants who were

qualified in absolute terms for admission but who possessed

the two additional characteristics of being disadvantaged

and members of racial or ethnic minorities. This was done

primarily in order to provide integrated learning experi

ences for its students, and it was done with the knowledge

30 The emperical results of the first two years of admissions

following the opening of the medical school would have alone led

to this conclusion. The Davis medical school’s minority admissions

after the first two years was also substantially below the 1969

national average of 4.8 percent, a national average greatly de

plored by the Association of American Medical Colleges. See,

“Report of the Association of American Medical Colleges Task

Force to the Inter-Association Committee on Expanding Educa

tional Opportunities for Blacks and Other Minority Students,”

(Washington: AAMC, April 22, 1970).

33

that the “objective” regular admissions criteria bore little

relationship to any student’s performance in medical

school.31

The medical school’s special admissions program was a

blunt but effective means of avoiding the exclusive reliance

upon “criteria or methods of administration which have the

effect of subjecting individuals to discrimination because

of their race, color, or national origin,” 45 C.F.R. §80.3(b)

(2) (1969). Subsequent additions to HEW regulations

governing the Davis medical school made it crystal clear

that the special admissions program with its racial and

ethnic criteria of application was precisely the “special

consideration to race, color, or national origin” required

of the medical school in order “to make the benefits of its

program more widely available to such groups, not then

being adequately served.” 45 C.F.R. §80.5(j) (1973).

The race conscious admissions program is therefore

approved by the HEW regulations published pursuant to

statutory authority, Lau v. Nichols, supra, the statutory

foundation for the regulations is well within Congress’

legislative domain, and the regulations are reasonably re

lated to the statutory objective—the hasty elimination of

racially segregated training opportunities financed by the

federal government.

81 Dr. Lowery acknowledged that only one of the four scores

computed from the Medical College Admissions Test correlated

with academic performance in the first two years of medical school.

Deposition of George H. Lowery, CT-152. He stated, “there is not

very much correlation beyond that.” I bid.

34

CONCLUSION

W h er efo r e , for the reasons stated above, Amicus re

spectfully urges the Court to reverse the decision of the

Supreme Court of the State of California below.

Respectfully submitted,

N a t h a n ie l R. J ones

General Counsel

W illia m D . W ells

Assistant Counsel

T h eresa D e m c h a k

Special Counsel

N a t h a n ie l S . Colley

West Coast Regional Counsel

National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People

1790 Broadway—10th FI.

New York, New York 10019

S ta nley G oodman

Law Intern

.i ®'

a V

t-o^d ’ '

tvs® , Tc^® V

C*-T_«oV$

*̂ .0

■$©■*

i,C? *l rv C0^ $ .-

to ,T*»

MEIIEN PRESS INC-— N. Y. C. 219