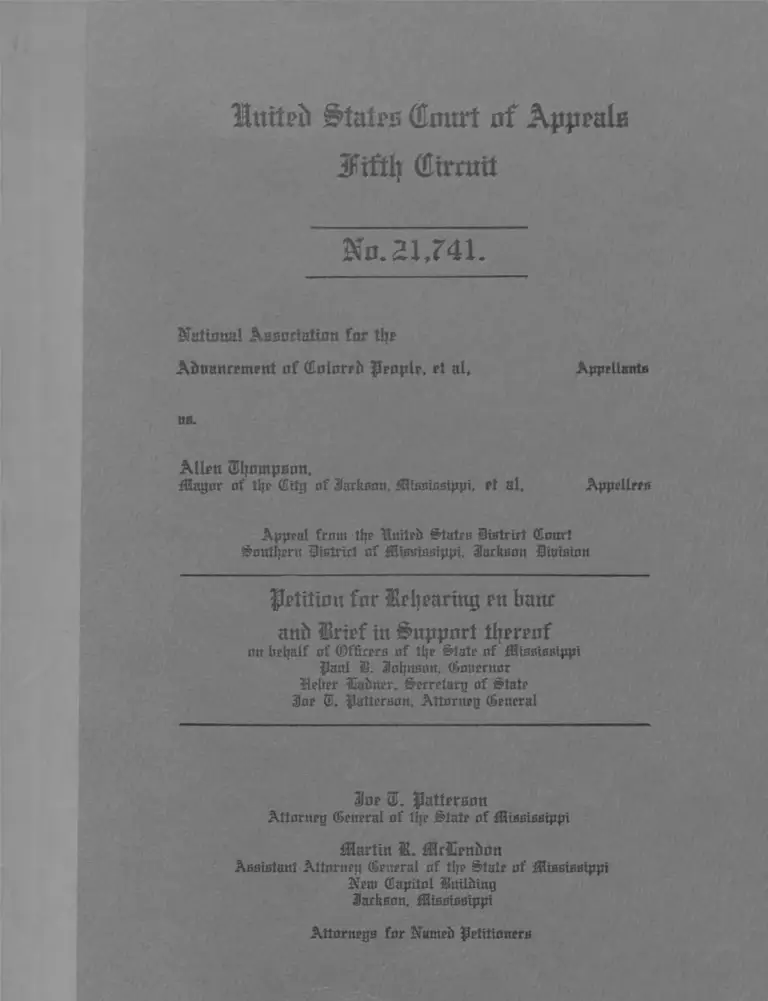

NAACP v. Thompson Petition for Rehearing En Banc and Brief in Support Thereof

Public Court Documents

March 25, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP v. Thompson Petition for Rehearing En Banc and Brief in Support Thereof, 1966. e733111c-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4e6b716d-a13f-411d-b551-c0d49e55da9f/naacp-v-thompson-petition-for-rehearing-en-banc-and-brief-in-support-thereof. Accessed March 11, 2026.

Copied!

Intteb Staffs (Enurt nf Appeala

Jffifitf (Etrruit

Nn. 21,741.

Matinnal Assoriatum far %

A&ttannmtrnt nf CEnlnrrh prnplr, rt alf Appellants

ns.

A lim StynmpBnn,

fHaynr nf tlje (Eity nf Sarkantt, fHtaaiaatppi, ft al, Appellrea

Appeal frnm tlje liniteb Staten Sistrirt (Emtrt

Southern Stsrtrid nf Mtasiaaippi, ilarkamt Simainn

Jfetitum fnr faring rtt hatur

attli Irirf tit gaippnrt tfymnf

nn behalf nf (Officers nf the Stale nf fHiaaiaatppt

Paul S . ilntjnamt, (Snnernnr

•Heber Hiabner, Secretary nf State

3Jne ®. Paiterann, Attnrnpg (general

3nr uL |lattrrflim

Attnrneg General nf ttye State nf fHisBiaaippi

Ulartin 2L mdEenbnn

Aaaiatant Attnrney (general nf ttye State nf iHtaataatppi

New (Eapitnl Untlbtng

Sarkann, iHtaaiaaxppt

Attnrneya fnr Narneb Petitinnera

1.

I N D E X

SUBJECT INDEX: Page.

PETITION FOR REHEARING EN BANC 1

COUNSEL'S CERTIFICATE 3

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PETITION FOR REHEARING EN BANC

ARGUMENT:

4

Proposition I: APPELLATE COURTS CANNOT MAKE

FACTUAL DETERMINATIONS WHICH MAY BE

DECISIVE OF VITAL RIGHTS WHERE THE CRUCIAL

FACTS HAVE NOT BEEN DEVELOPED 6

Proposition II: THE COURT IS WITHOUT JURISDICTION

OF THE PARTIES, THESE APPELLEES 12

Proposition HE: THE DOCTRINE OF EXCLUSION, WHEREBY

A STATE IS AUTHORIZED TO IMPOSE CONDITIONS

UPON THE RIGHT OF FOREIGN CORPORATIONS TO

DO BUSINESS WITHIN THE STATE OR TO EXCLUDE

THEM ALTOGETHER, IS A VALID SUBSISTING DOC

TRINE OF THE SUPREME COURT AND THE OPINION

OF THE PANELAND ORDER DIRECTED THEREBY

IS IN CONFLICT THEREWITH 15

CONCLUSION 19

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE 20

APPENDICES:

A: Opinion District Court, pertinent parts

B: Opinion this Court, pertinent parts

C: Section 5319, Mississippi Code 1942, Recom p.,

D: Section 5340, Mississippi Code 1942, Recomp. ,

TABLE OF CASES:

21

25

29

31

Asbury Hospital v. Cass County, N .Dak., 326 U.S. 207,

90 L. ed. 6 17

Bates v. City of Little Rock, 361 U.S. 516,

4 L. ed. 2d 480, 80 S.Ct. 412 6

Brown Shoe Co. v. U. S. , 370 U.S. 294, 8 L. ed. 510, 82S.Ct. 1502 12

11.

INDEX. (Cont'd): Page.

Connecticut Gen. Life Ins. Co. v. Johnson,

303 U.S. 77, 79, 80, 82 L .ed. 673, 676, 677, 58 S.Ct. 436 16

Hague v. Committee for Ind. Organizations,

307 U.S. 496, 83 L. ed. 1423, 59 S. Ct. 954 10

Hanover F. Ins. Co. v. Harding (Hanover F. Ins. Co. v. Carr),

272 U.S. 494, 507, 71 L .ed. 372, 379, 47 S.Ct. 179,

49 A. L .R . 179 16

Larson v. Domestic and Foreign Com. Corp. ,

337 U.S. 682, 93 L. ed. 1628 13, 14

Louisiana, ex rel, Jack Gremillion v. NAACP, et al,

366 U.S. 293, 6 L .e d .2d 301, 81S.Ct. 1333 6

Malone v. Bowdoin, 369 U.S. 642, 8 L. ed. 2d 168, 82 S.Ct. 980 13, 14

Mar bury v. Madison, 1 C ranch 137, 2 L .ed. 60 12

Miguel v. McCarl, 291U.S. 442, 78 L. ed. 902, 54 S.Ct. 465 11

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449,

2 L .e d .2d 1488, 78 S.Ct. 1163 6, 7, 17

New Orleans & N. E. R. Co. v. Harris,

247 U.S. 367, 63 L.Ed. 1167 8

Panama Canal Co. v. Grace Line, Inc.,

356 US 309, 2 L. ed. 2d 788, 78 S.Ct. 752 11

Price v. Johnson, 334 U.S. 266, 92 L .ed. 1356, 68 S.Ct. 1049 8

Terral v. Burke Construction Co. , 257 U.S. 529,

66 L.ed. 352, 42 S.Ct. 188, 21 A. L .R . 156 16

U. S. v. Greene County Bd. of E d., 332 Fed. Rep. 2d, 40 18

U. S. ex rel, v. Hitchcock, 190 U.S. 316,

47 L.ed. 1074, 23 S.Ct. 698 12

Work v. U. S. ex rel Rives, 267 U.S. 175, 69 L .ed. 651,

45 S.Ct. 252 12

OTHER AUTHORITIES:

31A C .J.S . , 164, et seq. , Evidence, §103, et seq. 8

Mississippi Code 1942, Recompiled,

Section 5319 [Appendix C, p. 29] 6

Section 5340 [Appendix D, p. 31] 10

22 U .S .C .A . , 2281, et seq. 6

28 U. S. C ., 1652 11

111.

INDEX (Continued):

OTHER AUTHORITIES (Continued): Page

United States Constitution,

Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 16

Eleventh Amendment 13, 14, 15

Fourteenth Amendment 7, 9, 17

Words and Phrases, Permanent Edition,

Vol. 7, page 261 10

Vol. 32, page 351 10

[Emphasis herein in quoted matter is supplied].

1 .

PETITION FOE REHEARING EN BANC

AND BRIEF IN SUPPORT THEREOF

Come now the officers of the State of Mississippi, Paul B. Johnson,

Governor; Heber Ladner, Secretary of State; and Joe T. Patterson, At

torney General; who are appellees in Count II of the above-entitled case,

and respectfully petition this Court for a rehearing en banc on the matter

of Count n of the original Complaint in this case, for the reasons herein

after set forth.

1. On March 8, 1966, a division of this Court rendered an Opinion

written by Judge Samuel E. Whitaker, of the U. S. Court of Claims, sit

ting by designation, finding: (1) That the Secretary of State notified the

corporate appellant that it was required to domesticate (Slip Opinion, p.

17); (2) That the legal reasons shown by the record to have been given

by the Attorney General and his assistant were not sufficient to warrant

a denial of the application for domestication (Slip Opinion, pp. 18, 19 &

20); and a gratia (3) the Governor, who gave no reason for the exercise

of his executive discretion in withholding his approval entirely, must

with the other officials approve the application. The panel of this Court

then ordered the District Court to issue a mandatory injunction whereby

these appellees are " . . . required to approve the application for domes

tication of the NAACP and to take all necessary and proper steps to en

title it to do business in the State of Mississippi. " (Slip Opinion, pp. 22

& 24).

2. The ruling ignored the holding of the District Court, that it, the

District Court, was without jurisdiction to enter such an order; and the

panel of this Court ordered the entry of the mandatory injunction without

giving the District Court the benefit of advising it wherein jurisdiction

to do so would lie.

2.

3. The ruling ordered these appellees to approve the application of

the foreign corporation to do business within the State of Mississippi;

which is contrary to and in direct conflict with the doctrine of exclusion

whereby a State can impose such conditions as it chooses on the right of

a foreign corporation to do business within the State or can exclude it

from the State altogether; a principle of law recognized and followed by

the Supreme Court since its organization down to and including the case

relied upon by the panel as authority for its order.

4. Since the Opinion of the panel is based upon a decision that is fac

tually not applicable here, and departs from applicable precedent by the

Supreme Court, both as to jurisdiction and subject matter, a rehearing

en banc is warranted under Rule 25(a) of the Rules of this Court and is

necessary to secure and maintain uniformity and continuity of the deci

sions of this Court with the decisions of the Supreme Court.

WHEREFORE, it is respectfully submitted that a rehearing en banc

should be ordered in this case.

Respectfully submitted this the 25th day of March, 1966.

PAUL B. JOHNSON, GOVERNOR OF THE

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

HEBER LADNER, SECRETARY OF STATE OF THE

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

JOE T. PATTERSON, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF

THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

APPELLEES—PETITIONERS.

B Y ------------------------------------------------------------------- —

MARTIN R. McLENDON, Assistant Attorney

General, Attorney for Appellees--Petitioners

P. O. Box 220

Jackson, Mississippi

3.

CERTIFICATE OF COUNSEL

I, MARTIN R. McLENDON, Counsel of record in this case for

the appellees--petitioners seeking a rehearing, do hereby certify that

the foregoing petition for rehearing en banc is presented in good faith

and not for delay.

MARTIN R. McLENDON

P. O. Box 220

Jackson, Mississippi

4.

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PETITION

FOR REHEARING EN BANC

No petition for rehearing has been filed asking for a re-examination

of the judgment of the Court with regard to Count I of the original com

plaint. Since there was no proof whatsoever connecting the facts upon

which Count I was brought with these appellees to Count II, the matter

presented herewith is limited solely to the right of an appellate Federal

Court to order a state to approve an application of a foreign non-profit

corporation to become a domesticated corporation of that state when

there is no showing whatsoever of any need for such approval to protect

the membership of that corporation of their right to associate and be af

filiated with the corporation.

Questions presented:

I. What, if anything, is shown by the record to have been done by

these appellees to the corporate appellant to deny it of due process or to

the individual appellants denying them privileges and immunities guaran

teed to them by the Constitution?

II. Wherein does jurisdiction of the District Court lie to order a

state to approve an application for domestication of a foreign non-profit

corporation?

III. Has the doctrine of exclusion, whereby a state is authorized to

impose conditions upon the right of foreign corporations to do business

within the state or to exclude them altogether, been abolished by the Su

preme Court and, if not, is the opinion of the panel and the order direct

ed thereby in conflict with that doctrine?

5.

INTRODUCTION TO ARGUMENT

These appellees will first show that there is no factual basis whatso

ever for the entry of an order against the State of Mississippi as contem

plated by the Opinion of the panel of this Court, and that the Opinion of

the Supreme Court relied upon by the panel is wholly foreign to the is

sues presented by this case.

We will next show that the District Court is without jurisdiction to

enter the order as directed and suggest that if the Opinion of the panel is

not re-examined and reversed, that it at least should be re-examined

and the District Court given the benefit of being advised wherein juris

diction to enter the order directed to be entered would lie.

Finally, these appellees will show that the doctrine of exclusion is

a valid and subsisting doctrine of the Supreme Court and the entry of the

order as directed by the panel of this Court is in conflict with that doc

trine.

For the convenience of the Court, the parts of the Opinion of the

District Court dealing with Count II have been reproduced and same is

attached hereto as Appendix A, and the parts of the Slip Opinion of the

panel of this Court dealing with Count n have been reproduced and same

is attached hereto as Appendix B. All of the evidence adduced in suppor

of Count II of the Complaint, and some of the argument of counsel, is

found on pages 312-370 of the record. Appellees offered only their Ex

hibit D -1.

ARGUMENT

Proposition I

APPELLATE COURTS CANNOT MAKE FACTUAL

DETERMINATIONS WHICH MAY BE DECISIVE OF

VITAL RIGHTS WHERE THE CRUCIAL FACTS

HAVE NOT BEEN DEVELOPED.

The Panel Opinion states:

"Prior to 1963 it (corporate appellant) carried on

these activities in the State of Mississippi through

unincorporated affiliates, although it maintained its

own offices in the state; while in 1962 it received

notice from the Secretary of State that the M issis

sippi Code had been amended, effective January 1,

1963, to require foreign non-profit corporations to

domesticate in order to do business in the State. "

That finding by the Panel cannot be based upon any fact developed

in the record for the reason that the record fails wholly to reflect that

any such notice was given to the corporate appellant, or anyone for that

corporation, by the appellee Secretary of State. Indeed, the complaint

does not even allege that such notice was given.

Sec. 5319, Miss. Code of 1942. Recp. , as amended in 1962, ef

fective January 1, 1963, was a part of the enactment of the "Mississippi

Business Corporation Act. " A copy of the statute currently in force is

attached hereto as Appendix C. This Court cannot enjoin the enforce

ment of that statute, 28 USCA 2281. et seq. , and the State has not sought

to enforce its provisions against the corporate appellant. The appellee

Attorney General has not attempted to enjoin the activities of corporate

appellant or any of its members.'1' The record is clear that the activities

1 - N. A A .C .P . v. Alabama. 357 U.S. 449, 2 L. Ed. 2d 1488, 78 S.Ct.

1163; Bates v. City of T ittle Rock. 361 U.S. 516, 4 L. Ed. 2d 480, 80

S.Ct. 412; Louisiana, ex rel. Jack Gremillion v. N. A. A .C .P . . et

al, 366 U.S. 293, 6 L. Ed. 2d 301, 81 S.Ct. 1333.

7.

of the corporate appellant and its members go on unabated.

It is emphasized at this point that no showing whatsoever is made in

this record of any attempt on the part of any of these appellees to deprive

any of the individual members of corporate appellant of their right to

free speech, assembly, protest and peaceful picketing or indeed to de

prive them of their right to membership in the corporate appellant. The

rights of individual citizens of the United States to enjoy privileges and

immunities guaranteed to them by the Fourteenth Amendment are not in

volved in this petition for rehearing. No such deprivation of constitu

tional rights or attempt at such deprivation is shown by the record to

exist insofar as these appellees and Count II of the original complaint

are concerned. The language of the Attorney General quoted in the Slip

Opinion of differences between the corporate appellant and its approach

to problems and his own is not entitled to be compared with the allega

tions for injunction as was done by the Panel Opinion to substantiate its

2application of NAACP v. Alabama to the case at bar.

NAACP v. Alabama. 377 U.S. 288, does not support the conclusion

reached by the panel for the reasons that: (1) jurisdiction of the Court

to enter the order that it did was waived by Alabama having brought the

suit; (2) granting the right to foreign corporations to do business in

Alabama is, by virtue of Alabama statutes, a ministerial function on the

part of the Secretary of State; and (3) the order directed to be entered

in that case was the result of the case having been brought before the

2 - N .A .A .C .P . v. Alabama. 377 U.S. 288, 12 L .e d .2d 325, 84 S.Ct.

Supreme Court four different times and could be considered in the nature

of the Court's version of justice to a vanquished foe in order to finally

dispose of the matter.

The testimony that foreign non-profit corporations have been treat

ed alike in all respects by the office of the Attorney General is not dis

puted by any evidence offered on behalf of the corporate appellant. In

fact, the total dirth of evidence on behalf of the corporate appellant real

ly presents a question of law for determination because the facts devel

oped show only that the application for domestication was filed and that it

was subsequently denied.

Appellate courts cannot make a factual determination which may be

3

decisive of vital rights where the crucial facts have not been developed.

The burden of proof was on the corporate appellant to show that it,

as a corporate entity as distinguished from its members, was entitled to

the relief sought in this case both as a matter of fact and as a matter of

law.^

There is a total absence of proof that the denial of the application of

the foreign non-profit corporation to become domesticated in Mississippi

effects or affects the constitutional rights of any individual member

thereof or of any citizen of the United States. As heretofore observed, * 4

3~ Price v, Johnson. 334 U.S. 266, 92 L.Ed. 1356, 68 S.Ct. 1049.

4- The United States Supreme Court held in New Orleans & Northeastern

E. Co. v. Harris. 247 U.S. 367, 63 L. Ed. 1167: "The burden of

proof is on the plaintiff in making out its cause of action, and this

burden of proof must be satisfied in order to sustain the decision or

finding in favor of the party on whom the burden rests. " 31A C. J. S.

164, et s e q ., Evidence, §103, et seq.

the only issue presently pending is the right of a foreign non-profit co r

poration through the good offices of this Court to force itself upon the

State of Mississippi.

The question then is not whether any constitutional right of any in

dividual citizen has been violated but whether the corporate appellant is

vested with a constitutional or statutory right to do business in the State

of Mississippi and the propriety of the issuance of the permanent manda

tory injunction to accomplish that result.

The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

has never been construed to vest "privileges and immunities" in corpor

ations. "Privileges and immunities" protected by that constitutional

amendment are limited to " . . . citizens of the United States, . . . " The

very nature of the "privileges and immunities" granted by the amend

ment are such that an artificial legal entity, i. e. , a corporation, is in

capable of exercising or enjoying them. The "privileges and immuni

ties" of citizenship can only be enjoyed by citizens. Corporations are

not and cannot be made citizens capable of exercising "privileges and

immunities" of citizenship.

That a corporation is not a citizen entitled to privileges and immun

ities has been consistently upheld by the United States Supreme Court.

"-A corporation is not a citizen, within the meaning

of the constitutional provision, and hence has not

the privileges and immunities secured to citizens

against state legislation. Orient Ins. Co. v. Dagqs.

19 S.Ct. 281, 282, 172 U.S. 557, 43 L .ed. 552, cit

ing P au lj£^ _S taJ^ O ii3M 75 U.S. (8 Wall.) 168,

19 L. ed. 357."

(Citing numerous ca se s .)

10.

"A corporation is not a 'citizen', within U.S. C. A.

Const. Amend. 14, as to the abridgment of privi

leges and immunities of citizens, . . . ". 5

(Citing numerous ca se s .)

It is elementary that a corporation cannot assert for others rights

g

which it itself does not have or enjoy.

It is equally well established that corporations are persons within

the Federal and State Constitutions guaranteeing to all persons due pro

cess of law,''7 as it is that corporations are not citizens possessing "priv

ileges and immunities" as such.

The record clearly reflects in this case that the corporate appellant

has been treated equally and in the same manner as all other foreign non

profit corporations similarly situated and that equal protection of the law

is therefore satisfied.

The approval or disapproval of applications for domestication of

foreign non-profit corporations is vested by State statute in the Governoi.

A copy of the statute, §5340, Miss. Code of 1942, R ecp ., is attached

hereto as Appendix D. The Court will note that the statute authorizes

the Governor, in the exercise of his executive discretion, to withhold

his approval entirely when acting upon corporate charter applications.

This is exactly what has been done in the instant case, and the exercise

of that executive discretion should not be the subject of the issuance of

Words and Phrases. Permanent Edition, Volume 7, page 261.

°~ Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organizations, 307 U.S. 496,

83 L .ed. 1423, 59 S.Ct. 954.

Words and Phrases. Permanent Edition. Volume 32, page 351.

11.

a permanent mandatory injunction as directed by the Panel Opinion.

The issuance of a permanent mandatory injunction to affirmatively

require a public official to perform an act is, in effect, equivalent to a

O

writ of mandamus, and is governed by like considerations.

§5340, supra, clearly and beyond question vests discretion in the

Governor of the State of Mississippi as to whether or not he will grant an

application for domestication of a foreign corporation when it provides

for the granting of such an application and then provides " . . . or if

deemed expedient by him he may withhold his approval entirely. "

"The remedy of mandamus is, in the main, restricted

to situations where ministerial duties of a non-discre-

tionary nature are involved, as where the matter is

per adventure clear, or an administrative agency is

clearly derelict in failing to act, or the action or in

action turns on a mistake of law. "9

As heretofore shown, the act performed by the former Governor of

Mississippi in rejecting the application of corporate appellant was clear

ly the exercise by him of discretion vested in him by the statutes and

laws of the State, which said laws shall be regarded as rules of decision

10by this Court.

Where an officer is given discretion, mandamus and permanent man

datory injunction being comparable and governed by like consideration,

neither will issue to control a public officer in discharging an official

8~ Miguel v. McCarl. 291 U.S. 442, 78 L .ed . 902, 54 S.Ct. 465.

Panama Canal Co. v. Grace Line. Inc. , 356 US 309, 2 L. ed. 2d 788,

78 S.Ct. 752.

10- 28 U .S.C . 1652.

12.

duty which requires the exercise by him of judgment and discretion .^

Proposition II

THE COURT IS WITHOUT JURISDICTION

OF THE PARTIES. THESE APPELLEES

District Courts are courts of limited jurisdiction. Jurisdiction of

the Court is fundamental and ". . . a review of the sources of the

Court's jurisdiction is a threshold inquiry appropriate to the disposition

12

of every case that comes before u s ."

These appellees, the Governor, the Attorney General and the Sec

retary of State of the State of Mississippi, in withholding the approval

of the application for domestication of the appellant corporation, acted

in accordance with authority vested in them as such state officials and

their action therefor was state action. Section 5340, supra, authorizes

the Governor to take the advice of the Attorney General and to approve,

require amendments prior to approval, " . . . or if deemed expedient

by him he may withhold his approval entirely. "

The record shows without dispute that the application for domestica

tion has, in fact, been denied and the approval of the state withheld en

tirely.

There cannot then be any doubt that the Panel of the Court by order

ing the issuance of the permanent mandatory injunction is ordering the

Work v. United States ex rel. R ives. 267 U.S. 175, 69 L.Ed. 651,

45S .C t. 252; United States ex rel. Riverside Oil Co. v. Hitchcock.

190 U.S. 316, 47 L.Ed. 1074, 23 S.Ct. 698; Marburv v. Madison.

1 Cranch 137, 2 L.Ed. 60.

Brown Shoe Company v. United States. 370 U.S. 294, 8 L.Ed. 510,

82 S.Ct. 1502.

District Court to exercise jurisdiction over one of the United States in

a suit by citizens and persons of another state.

Jurisdiction of the Court to grant such relief was removed by the

Eleventh Amendment, which provides:

"The Judicial power of the United States shall not be

construed to extend to any suit in law or equity, com

menced or prosecuted against one of the United States

by Citizens of another State, or by Citizens or sub

jects of any Foreign State. "

This amendment and the principle of sovereign immunity have been

the subject of considerable litigation in the Courts of the United States.

13In Malone v. Bowdoin the Court said:

"While it is possible to differentiate many of these

cases upon their individualized facts, it is fair to

say that to reconcile completely all the decisions

of the Court in this field prior to 1949 would be a

Procrustean task.

"The Court's 1949 Larson decision makes it unneces

sary, however, to undertake that task h ere ."

14In Larson v. Domestic and Foreign Commerce Corporation. the

Court announced the rules applicable to this case:

"The question becomes difficult and the area of con

troversy is entered when the suit is not one for dam

ages but for specific relief: i . e . , the recovery of

specific property or monies, ejectment from land,

or injunction either directing or restraining the de

fendant o fficer 's action. In each such case the ques

tion is directly posed as to whether, by obtaining

relief against the officer, relief will not, in effect,

be obtained against the sovereign. For the sovereign

can act only through agents and, when an agent's ac

tions are restrained, the sovereign itself may, through

him, be restrained. As indicated, this question does

not arise because of any distinction between law and

equity. It arises whenever suit is brought against an

Malone v. Bowdoin. 369 U.S. 642, 8 L. ed. 2d 168, 82 S.Ct. 980.

Larson v. Domestic and Foreign Com. Corp. , 337 U.S, 682, 93 L. ed. 16

13

28

officer of the sovereign in which the relief sought from

him is not compensation for an alleged wrong but, rath

er, the prevention or discontinuance, in rem, of the

wrong. In each such case the compulsion, which the

court is asked to impose, may be compulsion against

the sovereign, although nominally directed against

the individual officer. If it is. then the suit is barred.

not because it is a suit against an officer of the Govern

ment. but because it is. in substance, a suit against

the Government over which the court, in the absence of

consent, has no .jurisdiction.

* * *

"In a suit against ah agency of the sovereign, as in

any other suit, it is therefore necessary that the plain

tiff claim an invasion of his recognized legal rights.

If he does not do so, the suit must fail even if he al

leges that the agent acted beyond statutory authority

or unconstitutionally. Eut, in a suit against an agency

of the sovereign, it is not sufficient that he make such

a claim. Since the sovereign may not be sued, it

must also appear that the action to be restrained or

directed is not action of the sovereign. The mere al

legation that the officer, acting officially, wrongfully

holds property to which the plaintiff has title does not

meet that requirement. True, it establishes a wrong

to the plaintiff. But it does not establish that the o ffi

cer, in committing that wrong, is not exercising the

powers delegated to him by the sovereign. If he is

exercising such powers the action is the sovereign's

and a suit to enjoin it may not be brought unless the

sovereign has consented."

Even though the Court, in both Malone, supra, and Larson, supra,

was dealing with sovereign immunity as it applies to agencies of the

Federal Government, the principles announced are equally applicable

to an action against state officers because such action not only involves

sovereign immunity but this Court is prohibited by the Eleventh Amend

ment, supra, from exercising jurisdiction in such cases.

Since the relief ordered is a permanent mandatory injunction direct-

ex against the State, it is clear that the rules quoted above and relied

upon by the District Court are opposed to granting of the relief sought.

The action of these appellees in this matter were acts of the State

of Mississippi. These appellees were only acting for the State in dealing

with the corporate appellant. If the Court approves the order of the

Panel, the District Court will be forced to act against the State. The

State will be the party compelled to act as effectively as though it were

a party in name as well as in fact.

The compulsion, which the Panel of the Court ordered, if imposed,

will be compulsion against the sovereign, although nominally directed

against the individual officers. It cannot be considered otherwise be

cause the present Governor, against whom the compulsion is directed,

has not even considered the matter.

The compulsion sought is clearly against the sovereign, which has

not consented to being so compelled, and is therefore barred by the

Eleventh Amendment, supra.

Proposition III

THE DOCTRINE OF EXCLUSION, WHEREBY A STATE

IS AUTHORIZED TO IMPOSE CONDITIONS UPON THE

RIGHT OF FOREIGN CORPORATIONS TO DO BUSINESS

WITHIN THE STATE OR TO EXCLUDE THEM ALTO

GETHER, IS A VALID SUBSISTING DOCTRINE OF THE

SUPREME COURT AND THE OPINION OF THE PANEL

AND ORDER DIRECTED THEREBY IS IN CONFLICT

THEREWITH.____________________________________________

One of the fundamental legal differences between a natural-born

citizen and a corporation in this country is that a natural-born citizen

can move freely from state to state, whereas a corporation, being a

creature of the state of its creation, moves from that state to all other

states by the grace and permission of the state into which it seeks to

move. The two exceptions to that distinction are: (1) that corporations

engaged in interstate commerce may not be restricted to the state of

16.

their creation; ^ and (2) the right of exclusion may not be exercised

so as to deprive the corporation of any constitutional right which it, the

corporation, may have as distinguished from the constitutional rights

of the shareholders or members of the corporation . ^

Corporate appellant produced no evidence to show that it came with

in either of the exceptions noted above. The corporate appellant pro

duced no evidence to show that the denial of its application for domesti

cation in Mississippi had any effect whatsoever upon the constitutional

rights of any of the individual members thereof.

Instead, the corporate appellant demanded that the District Courts

assume jurisdiction and order the State of Mississippi, through its

proper officials, to approve the application as though and as if the co r

poration had a right in and of itself to engage in intrastate business with-

in the State of Mississippi and have and receive corporate franchise tax

exemptions and other benefits bestowed upon domestic corporations by

the State.

In its opinion, the District Court recognized the long-settled prin

ciples that a state is not required to admit foreign corporations to carry

on intrastate business within its borders, and that the State may arbi

trarily exclude them or may license them upon any terms that it sees

fit, apart from exacting a surrender of a recognized right of the corpor-

17ation derived from the Constitution of the United States.

Art. I, Sec. 8, Cl. 3, U. S. Constitution.

16- Terral v. Burke Construction Co. . 257 U.S. 529, 66 L. Ed. 352,

42 S.Ct. 188, 21 A .L .R . 156.

^ ~ Hanover F. Ins. Co. v. Harding (Hanover F. Ins. Co. v. C arr).

272 U.S. 494, 507, 71 L.Ed. 372, 379, 47 S.Ct. 179, 49 A .L .E .

179: Connecticut Gen. Life Ins. Co. v. Johnson. 303 U.S. 77, 79,

80, 82 L. Ed. 673, 676, 677, 58 S. Ct. 436.

17.

The right of exclusion was not changed by the adoption of the

Fourteenth Amendment:

"The Fourteenth Amendment does not deny to the

state power to exclude a foreign corporation from

doing business or acquiring or holding property

within it. Horn Silver Min. Co. v. New York, 143

US 305, 312-315, 36 L. ed. 164, 167, 168, 12 S.Ct.

403, 4 Inters. Com. Hep. 57; Hooper v. California,

155 US 648, 652, 39 L. ed. 297, 298, 15 S.Ct. 207,

5 Inters. Com. Rep. 610; Munday v. Wisconsin

Trust C o ., 252 US 499, 64 L. ed. 684, 40 S. Ct. 365;

Crescent Cotton Oil Co. v. Mississippi, 257 US

129, 137, 66 L. ed. 166, 171, 42 S.Ct. 42."

Indeed, the doctrine of exclusion was recognized in the case relied

upon by the Panel of this Court as its sole authority for directing that

the order of approval of the application for domestication be entered. ^

The issue in that case was the right of a state to enjoin the association

of the members of the corporate appellant with the corporation. The

issue in this case is the right of that corporation to force itself upon

the state when no attempt has been made to interfere with its activities

or the rights of its members.

As heretofore shown, in distinguishing that case from the case at

bar (pages 7-8 hereof), the relief ordered to be granted in that case

was a result of militant aggressiveness on the part of the State of Ala

bama. In the case at bar, the only militancy shown is the testimony of

the State Attorney General that he does not agree with the corporate

appellant's approach to problems and for that reason does not believe

that the State should place its stamp of approval on the corporation. No

militancy whatsoever has been shown toward the individual members of

the corporate appellant by any of these appellees. Notwithstanding the

Asbury Hospital v. Cass County, North Dakota. 326 U.S. 207, 90

L. Ed. 6.

19- N .A .A .C .P . v. Alabama. 377 U.S. 288, 12 L. ed. 2d 325, 84 S.Ct.

1302.

total lack of any factual showing of entitlement to the relief sought, and

ordered by the Panel of this Court, we submit that the Panel miscon

strued the applicable law as announced by the Supreme Court and its o r

der to the District Court is contrary to the rule announced by this Court

in such cases.

20In United States v. Greene County Board of Education. this Court

summarized the rule for appellate review of a District Court's denial of

a permanent mandatory injunction in the following language:

"The rule applicable to injunctions was announced

early in the history of this country by Justice Bald

win, sitting at Circuit in 1830 in Bonaparte v. Cam

den (C.C.N . J. 1840) Fed. Cases No. 1617: 'There

is no power the exercise of which is more delicate,

which requires greater caution, deliberation, and

sound discretion, or more dangerous in a doubtful

case, than the issuing an injunction; * * *. ' The

rule applicable in the Fifth Circuit was succinctly

stated by Judge Hutcheson in Reliable Transfer

Company v. Blanchard, (5th Cir. 1944) 144 F.2d 551.

"'In thus arguing, appellant proceeds upon the wholly

incorrect assumption that, conceding power, the is

suance of the injunctions was mandatory. It is horn

book law that "'"Courts of equity exercise discretion

ary power in the granting or withholding of their ex

traordinary remedies, and that although this d iscre

tionary power is not restricted to any particular

remedy, it is particularly applicable to injunction

since that is the strong arm of equity and calls for

great caution and deliberation on the part of the

cou rt.'" " [Citing cases] Here again it is horn book

law that whether an injunction will or will not issue

rests within the sound discretion of the court, and

that the exercise of this discretion will not be dis

turbed unless there has been a clear abuse of it,

45 Am. Jur., Sec. 180, p. 936."

* * *

"Discretion of the Trial Court must clearly be abused

before appellate courts will reverse for failure to

grant a mandatory injunction. United States v. W. T.

Grant C o.. 345 U.S. 629. 73 S.Ct. 894. 97 L.Ed.

1303 (1952): 'The chancellor's decision is based on

all the circumstances: his discretion is necessarily

20- U. S. v. Greene County Bd. of Ed. , 332 Fed. Rep. 2d, 40.

19.

broad and a strong showing of abuse must be made to

reverse it.

CONCLUSION

It is, therefore, respectfully submitted that this Court should grant

to these appellees a rehearing en banc, and direct that the issues here

in be re-argued orally before the Court sitting en banc, and that the

Opinion of the Panel of this Court be re-examined by the full Court for

the purpose of determining whether the Panel Opinion is in conformity

with decisions of the Supreme Court.

It is further submitted that on a re-examination of that Opinion,

that the Court determine that jurisdiction of the District Court to enter

the order directed to be entered by the Panel as against these appellees

does not exist; and, in the event the full Court determines that juris

diction to enter the order does exist, that it will render its Opinion ad

vising the District Court wherein such jurisdiction does lie.

It is further submitted that the full Panel of this Court should re

examine the Panel Opinion to determine whether or not it is in harmony

with the long-established doctrine of exclusion laid down and consist

ently followed by the Supreme Court insofar as states and corporate

entities are concerned; and, in the event the full Court should deter

mine that the opinion of the Panel is not in harmony with the doctrine

of exclusion, that the full Court render its Opinion vacating the order

of the Panel.

20.

Respectfully submitted, this the 25th day of March, 1966.

PAUL B. JOHNSON, GOVERNOR OF THE STATE

OF MISSISSIPPI

HEBER LADNER, SECRETARY OF STATE OF

THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

JOE T. PATTERSON, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF

THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

APPELLEES—PETITIONERS

MARTIN R. McLENDON, Assistant

Attorney General, Attorney for

Appellees--Petitioners

P. O. Box 220

Jackson, Mississippi

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, MARTIN R. McLENDON, attorney of record for these appellees—

Petitioners, do hereby certify that I have this day served a true and

correct copy of the above and foregoing Petition for Rehearing en banc

and Brief thereon upon the attorneys of record for the appellants by

mailing copies to them, United States postage prepaid, at the ad

dresses shown in appellants' brief.

This the 25th day of March, 1966.

MARTIN R. McLENDON.

APPEN DIX A . (T itle O m itted).

OPINION

The corporate plaintiff. . . The complaint is in

two counts. . .

Count 2 of the complaint is basically a claim against

the Governor, State Attorney General and Secretary of

State to compel those authorities to approve the applica

tion of the corporate plaintiff, as a non-stock, non-profit

corporation chartered under the laws of New York, to

qualify to engage in business in Mississippi. Those

state officials are vested by the state with the adminis

tration of the laws of the State of Mississippi governing

domestic and foreign corporations qualified to do busi

ness within the state. Those officials rejected such ap

plication of said foreign corporation to do business in

this state, although it has admittedly done business in

Mississippi for many years. . .

As to the second count, the defendants contend that

the charter of the corporate plaintiff does not comply

with important requirements of the laws of Mississippi

regulating the incorporation of non-stock, non-profit

corporations; that they have not discriminated against

this corporation in denying it authority to do business

in Mississippi, but that they have denied such authority

in like manner to other foreign corporations from dif

ferent states. The defendants further say that this

claim in this count is effectually a suit against the State

of Mississippi against its wishes in violation of the

Eleventh Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States. . .

This case has not been heard by the Court on its

merits, and after hearing all of the testimony adduced

by the parties and receiving and considering all of the

evidence of both parties, the Court was furnished with

able briefs by counsel for the parties, and after hearing

oral arguments of counsel, the Court examined all of

their authorities and presently makes its finding of

facts and conclusions of law thereon. . .

FINDING OF FACTS. . .

The burden of proof is on the plaintiffs to show by

a preponderance of the evidence the necessity for an

injunction and their right to such extraordinary process

in this case. . .

22.

APPENDIX A (Cont'd):

The corporate plaintiff has not shown by a prepon

derance of the evidence that its application to do business

in Mississippi was arbitrarily and capriciously denied.

The Governor of the State refused to sign the permit au

thorizing this New York corporation to engage in business

in Mississippi because the Attorney General of M issis

sippi advised him that the corporation did not meet the

statutory requirements therefor; and that it was not in

the best interest of the State of Mississippi to authorize

such corporation to engage in its intrastate business

within Mississippi. No fact or circumstance is shown

by the evidence to support any claim of this foreign co r

poration to a vested right to do business within M issis

sippi, and it is not shown factually that any constitutional

right of this New York corporation is violated by such re

fusal. The suit is in this respect essentially a suit against

the State of Mississippi, which though not a party to the

suit in name is a party in effect, against its wishes and

in violation of the Eleventh Amendment of the Constitution

of the United States.

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

The NAACP, a New York corporation, seeks to sue

in the first count of the complaint for the use of its mem

bers. The defendants resist that procedure on the ground

that constitutional rights may be asserted only by the per

son entitled thereto and not by one for another. The

NAACP relies for its authority upon NAACP v. Alabama.

357 US 449. That was a proceeding by a state to compel

the NAACP to disclose its membership list. The corpor

ation advanced the interest of its members in secrecy of

association as a defense and was sustained by the Court

in that position. That decision is a far cry from the right

of the corporation to file a suit, as here asserted, to have

adjudicated certain affirmative constitutional rights of its

members. That simply may not be done. Hague. Mayor,

et al v. CIO. 307 US 496. That is the unmistakable man

date of Civil Rule 17(a) and is controlling on the point here.

The right of free speech, assembly, worship, protest,

peaceful picketing, and any other right conferred by the

Federal Constitution is not in issue, and is not disputed,

or questioned here. . .

Nobody questions plaintiffs' undoubted rights to free

speech, assembly, protest and peaceful picketing. . .

23.

APPENDIX A (Cont'd):

Finally, as to the status of the corporate plaintiff as

a New York corporation seeking to domesticate in M issis

sippi, no contract right is involved, or impinged upon in

this case. No employment by the Federal government is

present. A state may not only regulate the entry of a for

eign corporation into intrastate commerce, but it may ex

clude it all together. A state may in the exercise of its

police power exclude any foreign corporation and deny it

the right to do intrastate business for any reason deemed

to be necessary and proper, short of arbitrary action.

Mississippi would not grant a certificate of incorporation

to a non-stock, non-profit corporation with a set up iden

tical to that of the NAACP here. Pursuant to an opinion

of the Attorney General, the Governor declined to admit

the NAACP to do business in Mississippi. That refusal

on this record is not shown by a preponderance of the evi

dence to be arbitrary.

The function of the Governor in domesticating a fo r

eign corporation is not a ministerial or perfunctory act.

It is a question committed to the exercise of a sound and

reasonable discretion. Neither an injunction, nor a man

damus may be used to control or direct the exercise of

such discretion in a particular way. Both writs are ex

traordinary processes, and are to issue only under the

most impelling circumstances to prevent irreparable in

jury. The writ will not issue as a matter of right but is

committed to the sound discretion of the Court. Moor v.

Texas & N .Q .R .R . . 297 US 101, 56S.Ct. 372. The co r

poration has not shown by a preponderance of the evidence

that it is entitled to an injunction. It cannot be said with

any degree of assurance that the refusal to domesticate it

is arbitrary. The Attorney General furnished the Govern

or with his legal opinion to the effect that the NAACP did

not have the requisite membership in Mississippi, and

that their domestication was not in the public interest.

He could have referred to instances such as its incitement

to the disorders before the Court in this case, or the like,

but plaintiffs say he objected to their Civil Rights suits.

Surely, the corporation had the right to aid and encourage

and assist negroes in the realization and enjoyment of

their full constitutional rights, short of violating local

laws in doing so. In any event, it has not been shown to

the reasonable satisfaction of the Court that the NAACP

was unlawfully denied the right to domesticate in M issis

sippi. It is the opinion of the Court on this record that

the state had the right to reject its application to domes

ticate within the state under the circumstances here.

24.

APPENDIX A (Cont'd):

Ashbury Hospital v. Cass County. 326 US 207, 66 S.Ct.

61; State of Washington v, Superior Court. 289 US 361,

53S.Ct. 624; Atlantic Refining Co. v. Virginia. 302 US

22, 58 S.Ct. 75; Bank of Augusta v. Earle. 13 Peters

519, 10 L. Ed. 274; Lafayette v. French. 18 Howard 404,

15 L.Ed. 451. This suit by this corporate plaintiff for

this purpose cannot be maintained for another reason.

This suit is in effect a suit against the State of M issis

sippi itself. The state is here through its officials ob

jecting to being sued in violation of the Eleventh Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States. That ob

jection must be and is sustained. Larson v. Domestic

& Foreign Coro. . 337 US 682.

Accordingly, the entire complaint in this case is

without merit and should be dismissed at plaintiffs' cost

to be taxed according to the rules of the Court. A judg

ment accordingly may be presented.

________/ s / Harold Cox_____________

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

June 1, 1964

[Title Omitted].

(March 8, 1966.)

.APPENDIX B .

Eefore WHITAKER, Senior Judge,* WISDOM and THORNBERRY,

Circuit Judges.

WHITAKER, Senior Judge: This is an action brought in

two counts by the corporate plaintiff, a New York corporation.

. . . In the second count, they seek a mandatory injunction

against the Governor, the Attorney General, and the Secre

tary of State of Mississippi to require them to permit the co r

porate plaintiff to domesticate in order to do business in the

State of Mississippi. . .

In the second count plaintiffs allege that the corporate

plaintiff has taken all steps, which are enumerated, requisite

for domestication in the State of Mississippi, but that its ap

plication has not been granted because plaintiff's chief ob

jective is to eliminate all forms of racial discrimination in

Mississippi and elsewhere in the United States, and to assist

its members and others of the Negro race to protest against

such discrimination in various and sundry ways. Wherefore

it prays that a mandatory injunction issue against the Govern

or, the Attorney General, and the Secretary of State to re

quire them to license plaintiff corporation to do business

within the State, and for other relief. . .

In the second count of their petition, plaintiffs complain

of the refusal of the Governor to permit the corporate plain

tiff, a New York corporation, to domesticate. It is a non

profit, non-share corporation, organized to promote the

end of racial discrimination in the various States of the

Union. It has been actively engaged in this effort for many

years and in many areas of the United States, utilizing boy

cotts, picketing, mass demonstrations, and other means.

Prior to 1963 it carried on these activities in the State of

Mississippi through unincorporated affiliates, although it

maintained its own office in the State; but in 1962 it received

notice from the Secretary of State that the Mississippi Code

had been amended, effective January 1, 1963, to require

foreign non-profit corporations to domesticate in order to

do business in the State. In an effort to comply therewith,

it filed a copy of its charter of incorporation and of a reso

lution designating an agent for the service of process, both

duly authenticated, paid the required filing fees, and applied

Of the U. S. Court of Claims, sitting by designation.

APPEN D IX B . (C ont'd ).

for domestication.

The Mississippi law provides that upon receipt of an

application for domestication, it shall be referred to the

Attorney General for his opinion on whether there has been

compliance with the law and whether it is to the best inter

est of the State to grant it or deny it. If he expresses the

opinion that it is not in the best interest of the State to grant

it, he is required to give his reasons therefor.

Upon receipt of plaintiff's application, the Attorney

General wrote the Governor that, upon examination of the

application and the statutes of the State, he was of the

opinion that the application "is not authorized to be approved

by our office. " He did not give his reasons therefor.

In the Attorney General's testimony on the trial of this

case, he stated that in his opinion he "did not deem it to be

to the best interest of the State of Mississippi. " He was

asked if the requirements of Section 4065.3 of the M issis

sippi Code, requiring all State officers to undertake to

maintain segregation of the races, or if the fact that the

purpose of the NAACP was to aid and assist and develop the

citizenship rights of Negro citizens without segregation and

discrimination were factors influencing his determination.

He replied in the negative but added:

My observation and experience with the

NAACP which now covers about fourteen years

led me, convinced me, that it is not to the best

interest that the NAACP be domesticated, author

ized to do' business within the State of Mississippi.

I have found that the NAACP, like a good many

organizations of that kind, do not stick to the

stated purposes of their corporate charter but go

far beyond what their stated objectives and pur

poses is [sic]. For instance, your charter says

nothing about the method in which the NAACP will

employ in attempting to attain their objectives, it

says nothing about promoting riotous parades and

disorders, inflammatory speeches, meetings and

things of that kind that they do indulge in, none of

which is referred to of course in the charter of

incorporation. That's the reason I said it was not

to the best interest of the State of Mississippi for

this organization to have the stamp of approval of

the State of Mississippi placed upon it.

APPEN DIX B , (C on t'd ).

He said that that was one of the things he took into considera

tion in arriving at his opinion, but that there were others.

He said that the application for domestication showed

that plaintiff did not meet the requirements of Section 5310.1,

which provided that three of those who applied for incorpor

ation of a company must be residents of the State of M issis

sippi. Mr. McLendon, the Assistant Attorney General, said

that this was the sole basis for his recommendation that

plaintiff's application be denied.

This latter objection to plaintiff’s application is obvious

ly untenable, since Section 5310.1 clearly has no application

to foreign corporations seeking domestication. It applies only

to persons seeking an original charter from the State of M is

sissippi. The statute says that corporations "may * * * be

incorporated on the application of any three members, all

of whom shall be adult resident citizens of the State of M is

sissippi, authorized by any of the said organizations, in its

minutes, to apply for the charter. " [Emphasis supplied. ]

Manifestly, this has no application to a foreign corporation

seeking to domesticate. To so apply it would prevent most,

if not all, foreign corporations from domesticating.

Nor is the Attorney General's first reason, stated above,

adequate grounds for denying the application. In NAACP v.

Alabama. 377 U.S. 288 (1964), the Court in its opening state

ment in this case said it involved the right of the NAACP to

carry on its activities in Alabama. In 1956 the State Attorney

General had filed a bill in equity in the State court to oust the

NAACP from the State and the court had issued a temporary

restraining order prohibiting it from doing any business in

the State and from taking any steps to qualify it to do so. The

complaint detailed a number of activities of the defendant cor

poration, which, it was alleged, justified its ouster, among

which were:

* * * that it had "encouraged, aided, and

abetted the unlawful breach of the peace in many

cities in Alabama for the purpose of gaining nation

al notoriety and attention to enable it to raise funds

under a false claim that it is for the protection of

alleged constitutional rights"; [377 U.S. at 303]

These acts were alleged

* * * to be "causing irreparable injury to the

property and civil rights of the residents and citizens

APPEN D IX B (C ont'd ):

of the State of Alabama for which criminal prosecution

and civil actions at law afford no adequate relief. . .

The complaint stated also that "the said conduct, pro

cedure, false allegations, and methods used by Respond

ent render totally unacceptable to the State of Alabama

and its people the said Respondent corporation and the

activities and business it transacts in this State. " [377

U.S. at 303]

It will be observed that the reasons given by the Attorney

General of Alabama for seeking the ouster of the corporation

from the State closely parallel the reasons given by the Attor

ney General of Mississippi for recommending the disapproval

of its application for domestication in that State. . .

There is no occasion in this case for us to con

sider how much survives of the principle that a State

can impose such conditions as it chooses on the right

of a foreign corporation to do business within the State,

or can exclude it from the State altogether. E. q . .

Crescent Cotton Oil Co. v. Mississippi. 257 U.S. 129,

137. This case, in truth, involves not the privilege of

a corporation to do business in a State, but rather the

freedom of individuals to associate for the collective

advocacy of ideas. . .

We think that this case is controlling here, and on its author

ity, a mandatory injunction must issue directing the Governor to

approve plaintiff's application and directing the Secretary of State

to take all needful steps to authorize the plaintiff corporation to do

business in the State.

We are of the opinion that the District Court was in error

in dismissing plaintiffs' complaint. The judgment of the D is

trict Court is reversed and the case is remanded to it with di

rections to issue the following injunction, . . .

II. The defendants, Ross R. Barnett, Governor of the State

of Mississippi; Joe T. Patterson, Attorney General; and Heber

Ladner, Secretary of State; their successors in office, their

agents, servants and employees, are hereby required to approve

the application for domestication of the NAACP and to take all

necessary and proper steps to entitle it to do business in the

State of Mississippi.

[Mississippi Code 1942, Recompiled!.

§5319. Resident agent of nonprofit nonshare or nonprofit

or nonshare corporations: How designated.

Every nonprofit nonshare or nonprofit or nonshare corpor

ation, organized or domesticated under the laws of the State of

Mississippi, shall maintain an office in the county of its domi

cile in this state, in charge of an officer or officers of the cor

poration, or designate and appoint a resident agent for the ser

vice of process by the directors (by whatever named called) of

such corporation, a duly certified copy of the resolution desig

nating such resident agent, and the written acceptance of such

agency by the agent, to be filed with the Secretary of State, and

the Secretary of State and his successors in office may be desig

nated and appointed such agent in said manner and such designation

and appointment may be so accepted and if accepted shall be so filed.

A fee of Five Dollars ($5. 00) shall be paid to the Secretary of State

for each designation and appointment of agent filed by him.

No such corporation shall do any business in the State of

Mississippi until and unless it shall so maintain an office in the

county of its domicile in this state, in charge of an officer or

officers of the corporation, or it shall have filed a written

power of attorney designating the Secretary of State of the State

of Mississippi, or in lieu thereof an agent as above provided in

this section upon whom service of process may be had in event

of any suit against said corporation. The Secretary of State shall

be allowed such fees therefor as are provided by law for desig

nating resident agents.

Any such corporation failing to comply with the above pro

visions as to maintaining an office or agent for process shall not

be permitted to bring or maintain any action or suit in any of the

courts of this state. The failure of any such corporation to com

ply with the foregoing provisions shall constitute a violation of

the laws of the State of Mississippi and subject said corporation

to a penalty of not more than One Hundred Dollars ($100.00) to

be recovered by the Attorney General of Mississippi, or any

District Attorney at the request of the Attorney General, in the

Chancery Court of the county where such corporation has done

such business or wherever such corporation may be found.

In the event of death, resignation or removal of such res i

dent agent, another shall be substituted within thirty (30) days

in the same manner and accompanied by the same fee as in the

form er appointment; and until such substitution or, in the event

APPEN D IX C .

APPENDIX C (C ont'd ):

of the failure of such corporation to designate and qualify a res

ident agent where one is required by this Act, the Secretary of

State shall be the resident agent for the service of process upon

such corporation without resident agent until one shall have been

designated as herein provided.

The resident agent of any such corporation shall be a person

or persons residing in this state or a corporation, domestic or

foreign, duly authorized to do business in this state and authorized

by its charter or articles of incorporation or other instrument by

which it is created to act as such agent. If the resident agent be

a corporation, service of process upon it as such agent may be

made at its registered office in this state by service on the presi

dent, vice-president, an assistant vice-president, the secretary

or an assistant secretary of such resident agent.

No foreign nonprofit nonshare or nonprofit or nonshare cor

poration shall do business in the State of Mississippi until it has

first been domesticated according to the laws of the State of M is

sissippi, and any such corporation so doing business without such

domestication shall not be permitted to bring or maintain any ac

tion or suit in any of the courts of this state.

Any such corporation or any person or group of persons found

carrying on any of such corporations businesses or functions by

soliciting funds, holding meetings, maintaining offices, circulating

literature, or performing any other business or function in the

name of such corporation that has not qualified to do business in

this state in the manner provided by law may be enjoined by suit

in the Chancery Court of the First Judicial District of Hinds

County brought by the Attorney General in the name of the State

of Mississippi.

SOURCES: Laws, 1958, ch. 200; 1962, ch. 235, §150,

eff from and after January 1, 1963.

APPEN DIX P .

[Mississippi Code 1942, Recompiled]

§5340. Foreign corporations may be domesticated--attorney-

general and the governor to approve charter.

When said copy has been filed with the governor of this

state, he shall first take the advice of the attorney-general of

the state as to the constitutionality and legality of the provisions

of such charter or articles of incorporation or association, and

if the attorney-general shall certify to the governor that he finds

nothing in said charter or articles of incorporation or association

that are violative of the constitution or laws of this state, the

governor of the state may approve the same, and he shall write

his approval at the bottom of said charter or articles of incor

poration or association or certificate of incorporation, and

shall sign his name thereto, and shall cause the great seal of

the state to be thereto affixed by the secretary of state; but the

governor may require amendments or alterations to be made

previous to signing same, or if deemed expedient by him he

may withhold his approval entirely.

SOURCES: Codes, 1906, §916; Hemingway's 1917, §4090;

1930, §4161.