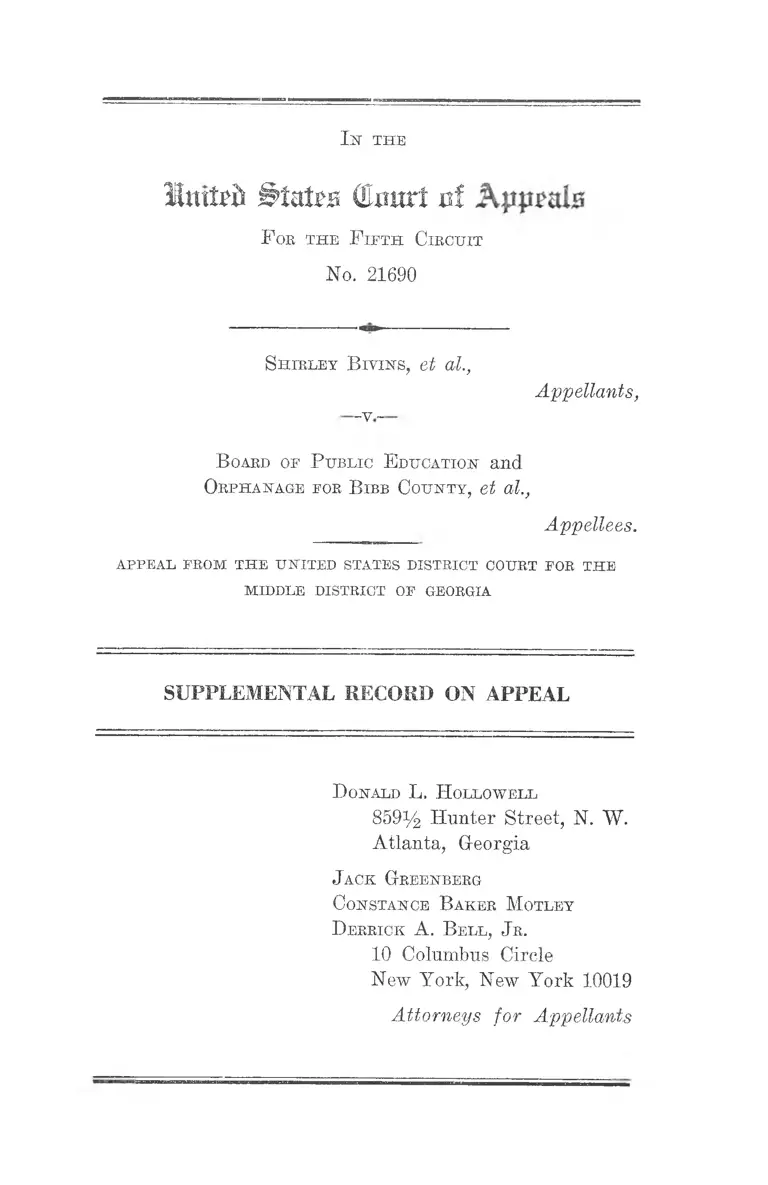

Bivins v. Board of Public Education and Orphanage for Bibb County Supplemental Record on Appeal

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bivins v. Board of Public Education and Orphanage for Bibb County Supplemental Record on Appeal, 1964. 7d3199f2-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4e76cbb7-aff9-4b61-bdac-cac5fbc3ec18/bivins-v-board-of-public-education-and-orphanage-for-bibb-county-supplemental-record-on-appeal. Accessed February 15, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

llttttdi Urates ( to r t cl

F oe the F ifth Circuit

No. 21690

Shirley B ivins, et al.,

- Y -

Appellants,

B oard of P ublic E ducation and

Orphanage for B ibb County, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

SUPPLEMENTAL RECORD ON APPEAL

D onald L. H ollo well

859% Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia

J ack Greenberg

Constance Baker Motley

Derrick A. Bell, J r.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

SUPPLEMENTAL INDEX

PAGE

Defendants’ Motion for Certification and Transmittal

of Additional Record on Appeal ....... ...................... 301

Defendants’ Written Argument .......... ......................... 304

Defendants’ Exhibits

Exhibit 1—Plaintiffs’ First Petition, December 9,

1954 ________ _______ ____________________ 322

Exhibit 2—Plaintiffs’ Second Petition, August 25,

1955 ........ ........... ......... ................................. ......... 324

Exhibit 3—Preliminary Report of Defendants’

Special iCommittee ............................................ 326

Exhibit 4—Letter and Statement from Macon

Council on Human Relations, February 23, 1961 .. 328

Exhibit 5—Letter of Dr. H. (}. Weaver, February

27, 1961 ____ __________ _______- ........ ......... 332

Exhibit 6—Letter from Petitioners, March 8, 1963

and Letter of Response from Dr. H. G. Weaver,

March 12, 1963 .............. ..................................... 333

Exhibit 7—Statement and Petition to Defendant

Board March 14, 1963 ..................................... ...... 336

Exhibit 8—Letter from Defendant Board’s Attor

ney on Legality of Desegregation, April 13, 1963 .. 338

Exhibit 9—Report of Rules and Regulations Com

mittee and Special Committee, April 24, 1963 ___ 343

Exhibit 10—Defendant Board’s Petition to the

Superior Court of Bibb County, April, 1963 ...... 345

11

PAGE

Exhibit 11—Declaratory Judgment—Superior

Court of Bibb County, July, 1963 ......................... 354

Exhibit 12—(See Exhibit A to Defendants’ An

swer at E. 23)—Resolution of Defendant Board .. 359

Exhibit 13—Procedure for Executing Student

Transfer Request .................. ................................. 360

Exhibit 14—Principles of High School Transfers.

Page 104 of 91st Annual Report of Defendant

B oard..... .............. .................................................. 374

Exhibit 15—Vocational Education and the Plan

for Integration, April 12, 1964 ............................ 376

Exhibit 16—Statement of Defendant Board.......... 382

301

Defendants’ Motion for Certification and Transmittal

of Additional Record on Appeal

I n the

DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Middle D istrict of Georgia

Macon Division

Civil Action No. 1926

Shirley B ivins, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

—v.—

B oard of P ublic E ducation and

Orphanage for B ibb County, et al.,

Defendants.

Defendants respectfully represent to the Court:

1.

The Clerk of this Court on designation by plain tiffs-

appellants of “the entire record in the subject case” has

certified and transmitted to the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit the complete reporter’s

stenographic transcript of the proceedings at the hearing

of said case together with the pleadings and orders of the

Court in said case.

2.

Included in the stenographic transcript so certified is

plaintiffs’ oral argument at the conclusion of the hearing,

commencing at page 319 thereof, but numbered by the re-

302

Defendants’ Motion for Certification and Transmittal

of Additional Record on Appeal

porter as page 1 following page 318. Said complete steno

graphic transcript, including plaintiffs’ oral argument, is

included in the printed record in the Court of Appeals which

was supplied by plaintiffs pursuant to Eule 23 (9) of the

Court of Appeals.

At the conclusion of the hearing on April 14, 1964, both

sides were given by the Court the privilege of oral argu

ment or written argument, as they might elect, and pur

suant thereto defendants elected to reduce their argument

to writing, which was filed with the Clerk and supplied to

the Court on April 17, 1964, within the time provided.

Plaintiffs elected to make oral argument which was re

corded and transcribed by the reporter and included in his

stenographic transcript.

4.

Whether plaintiffs’ oral argument included in the tran

script and certified and transmitted by the Clerk of this

Court and defendants’ written argument not so included or

transmitted are technically parts of the entire record desig

nated by plaintiffs-appellants may be questionable, but

defendants consider in the nature of the subject case that

both are pertinent and material to a clear understanding of

the case on appeal, and that defendants’ written argument

as well as plaintiffs’ oral argument should be certified and

transmitted.

W herefore, defendants present this motion pursuant to

Eule 75 (b) of the Eules of Civil Procedure and pray that

the Clerk of this Court be directed to certify and transmit

303

Defendants’ Motion for Certification and Transmittal

of Additional Record on Appeal

to the Court of Appeals a supplemental record to include

defendants’ written argument on file in this Court.

Respectfully submitted,

C. B axter J ones

1007 Persons Building

Macon, Georgia 31201

Attorney for Defendants

—4—

The within and foregoing Motion is hereby allowed and

the Clerk of this Court is directed to supplement this

record on appeal as requested. This 14 day of July, 1964.

W. A. B ootle,

U. 8. Judge.

304

—5—

Defendants’ Written Argument

April 17, 1964

Honorable W. A. Bootle

United States Judge

United States District Court

Macon, Georgia

B,e: Shirley Bivins, et al, Plaintiffs

v. Board of Public Education and Orphanage

for Bibb County, et al, Defendants

Civil Action No. 1926

Dear Judge Bootle:

In lieu of the usual oral argument at the conclusion of

the evidence we are “dictating” the argument in our office

so that it can be transcribed and presented in written form.

It is essentially informal, and is presented in this informal

manner without particular effort at organization. We have

attempted to condense it within reasonable limits.

Plaintiffs as representatives of a class filed this com

plaint against the Board, the 'Superintendent and the in

dividual members of the Board seeking relief from alleged

discrimination against the members of their race. Subse

quently the individual members of the Board were elim

inated by amendment.

The defendants, who will be referred to herein merely as

the Board, admitted without qualification that schools for

white and Negro children had been and were being operated

— 6—

separately and that plaintiffs were entitled to appropriate

relief as class representatives.

305

Defendants’ Written Argument

This court and the public generally are aware of the

historical and traditional pattern of public school education

in this area within the judicially approved concept of sepa

rate but equal facilities, specifically required until 1961 by

the Constitution and statutes of the State, and even there

after until July, 1963, by defendants’ charter, and of the

violence and travail that has followed the Supreme Court

decision in Brown and which still continues in lessening

degree. If nothing else these facts bear upon the good faith

and past conduct of the Board in dealing with the subject.

We think, however, that they continue to bear upon the

immediate and future plans and programs of the Board as

they are now presented to the court.

Mr. Hollowell argues for the plaintiffs that the Board

has been preparing for this transition for nearly ten years

and is now so well along that minimal additional time

should be required. That is a misinterpretation of the testi

mony. It is true that there has been recognition and dis

cussion of the problem but not until recently directed to

ward the solution of the problem in Bibb County. Until

1961, following Brown, state and legislative resistance to

change was intensified. By that time, whether to our credit

or merely from resignation to the inevitable, the climate

in the State, including the legislative climate, was changing.

—7—

Prior to 1961 a complaint had been filed in Atlanta, the

capital and the most concentrated urban area in the State.

All other communities were watching that case and nothing

was being done elsewhere.

Desegregation of the Atlanta system actually commenced

in September of 1961 and it was another year before the

results of the Atlanta program could be evaluated on the

306

Defendants’ Written Argument

basis of actual experience. The fact that the Atlanta plan

has progressed in an atmosphere of reasonable calm by no

means indicates that it would have done so under a more

precipitous or broader plan. It does indicate the proba

bility that something comparable may now be done in Bibb

County, but not that more sudden or more drastic steps may

be taken here. That is to say, something was possible in

Atlanta in 1961 which would have been utterly impossible

only a few years earlier, and something more became pos

sible in the 1963-64 school year, but the very fact that

these accomplishments have been achieved proves the wis

dom of the gradual approach to the problem which was and

still is contemplated under the Atlanta plan.

Bibb County is now substantially in the position of

Atlanta as late as two and one-half years ago, and there is

absolutely no reason to think that anything is capable of

accomplishment at the present time in Bibb County over and

beyond that which was then accomplished in Atlanta. Even

at that the Bibb County plan proposes the complete elim-

—8—

ination of the innumerable tests based on personality and

psychological factors with which the Atlanta plan com

menced. Actually the Bibb County plan proposes the com

pletely liberal and unbiased and non-discriminatory treat

ment of transfer applications which after two and one-half

years of effort and experience the Atlanta Board now

claims to be applying. In other words, on the basis of

factors to be considered and tests to be applied we are

today where Atlanta has been able to come after two and

one-half years of effort and experience. Furthermore, we

propose during the total transition period to actually catch

up with Atlanta by doubling the number of grades to be

desegregated in some years.

307

Defendants’ Written Argument

Just as it is in error to assume that preparations hereto

fore made by the Bibb County Board now make it possible

to proceed without preparation, neither is it permissible to

say that the Board’s conduct in the past or at the present

time condemns its motives or good faith. There is no point

in arguing whether separate schools are g'ood or bad. It

is not a question whether the Board approves or disap

proves the steps which it proposes and which it recognizes

as being required. In the fall of 1961 when desegregation

commenced in Atlanta no Negro pupil had applied in

Bibb County to attend a white school, nor has any applied

since unless the present complaint constitutes such an

application. No request or petition had been received from

any group of Negro parents or citizens since 1955. It may

—9—

have been wishful thinking but at that time and until March

of 1963 it seemed entirely possible to the Board that there

was substantial satisfaction with the situation as it then

existed in the local system. For reasons covered by the

evidence the general communication from the Macon Coun

cil on Human Relations of February 23, 1961, to various

governmental units and authorities was not so considered.

Even after the legislative session of 1961 there remained

the prohibition in the charter of the local Board with

respect to which we now wish to comment. Following the

communication of March 8, 1963, the Board of its own voli

tion took steps to obtain a State Court interpretation of

its charter and of its rights and powers thereunder. The

objective of this proceeding was not to avoid or to delay

desegregation but rather to make it possible. We believe

this is made crystal clear from the documents and testi

mony in evidence, including the letter from the Board’s

attorney, the state court petition itself, the extract from

the brief in the state court, and the order itself.

308

Defendants’ Written Argument

This order was obtained promptly in July of 1963, and

thereupon the Board immediately faced up to the question

whether it would really be better under all the circum

stances for the Board to voluntarily initiate a program of

desegregation or to act under court direction. We do

not think this requires elaboration. It has been suggested

that the Board could have worked out an agreement with

representatives of the Negro race, but with whom would

— 10—

the agreement have been made, and upon whom would it

have been binding?

If we have failed to impress the court with the Board’s

good faith intention to comply with the orders of this court

in this case it is due to the lack of skill of the Board’s

attorney in presenting the Board’s case and not to the

absence of such good faith intentions on the part of the

Board. When the Board decided to await court action it

was with the notice and knowledge that a petition had

been prepared by plaintiffs and that it would be filed im

mediately. The Board has done everything it could to

expedite the proceeding since that time.

We hope that we have been able to demonstrate to the

court that the Board is even more interested in the welfare

and educational opportunities of the children of the County,

both white and colored, than are the children themselves or

their parents. The members of the Board are dedicated to

that course. Particularly is this manifested in the area of

vocational education which is under the direction of Mr.

Kelley and who presented to the court the vocational pro

gram in operation in the County, and we call the court’s

attention to the fact that in the adult program Negroes

attend classes with white persons. In the school-work pro

gram and preparatory courses in the high schools the plan

proposed by the Board will apply.

309

Defendants’ Written Argument

We have not attempted by evidence or otherwise to

describe the disruptions and ill feelings which have been

associated with desegregation of schools in our section, or

— 11—

to predict or project the extent to which they will continue

in the future. Opposing counsel on cross examination

pressed some of the witnesses rather closely on that sub

ject, to name times and places, etc. The facts are that such

terms as crisis, critical, violence, disorder and similar

terms are found in almost every newspaper issue and in

numerous articles and court decisions. In Bush, referred

to by counsel, 308 F. 2d 491, as late as 1962, the court

reviewed the turbulence of the climate in New Orleans and

in the State of Louisiana in detailed and graphic terms.

Actually the Board does not think of itself as a litigant

in this case but rather as a supplicant to the court for

guidance and direction in a delicate and difficult field, and

for approval of the plan submitted by the Board as one

which under all the circumstances is reasonably designed

to recognize and afford to the plaintiffs, and to the class

represented by them, the rights to which they are entitled,

and at the same time to accomplish the Board’s primary

objective of providing the highest possible quality of public

education to all the children of the county.

The court expects us to comment on Bush, supra, from

which Mr. Hollowell quoted certain selected passages, and

we certainly will. We think that Bush, and also Augustus,

306 F. 2d 862, decided by the same court earlier in 1962,

both support rather than disapprove the Board’s plan. But

first certain clarifications are necessary.

We do not see how there can be any misinterpretation

—12—

of the Board’s plan, or what it purports or is intended to

accomplish. Mr. Hollowell professes confusion as to cer-

310

Defendants’ Written Argument

tain of its provisions. If the language is not clear and

adequate we want to make it entirely clear. As a “transi

tion” plan it is a transfer plan. In its ultimate goal it

ceases to be a transition plan. "We think this is well illus

trated by a consideration of the precise questions which

were dealt with in Bush (308 F. 2d 491), as we will later

point out.

If there is any doubt we want to make the following

things clear. In the initial year students now attending and

registered in the 11th grade of any high school in the

system will be afforded the right and ample opportunity

immediately, while they are still registered in the 11th

grade, to transfer for the 1964-65 school year to the 12th

grade of another high school. Having so transferred they

will then register in September of 1964 in the school to

which they have been transferred. If prior to September,

1964, they have not transferred to another school they will

register in the school which they previously attended. Even

then, under the Board’s rules at page 104 of its Annual

Report, but within the limitations of those rules, a student

may request transfer during the 1964-65 year. Any student

who enters the school system for the first time in or for

the 12th grade may choose the school which he wishes to

attend and will register initially at that school. All of this

is entirely without distinction based on race. As is true of

any student in the system this is subject to questions of

—1 3 -

eligibility, availability of the facility, and the capacity of

the school at which the student registers. In succeeding

years as the plan becomes applicable to additional grades

what we have said will continue to apply to the grade or

grades already brought within the plan as well as to the

additional grade or grades to be brought within the plan

311

Defendants’ Written Argument

that year. No student entering the system for the first time

in any grade to which the plan has become or is then to

become effective will be required to register at any school

designated on the basis of race.

Furthermore, when the plan becomes effective in the first

grade, applicable to students entering the system in that

grade, there is complete freedom of choice on the part of

the student to select the school which he wishes to attend.

This also will be subject to non-discriminatory factors

based on eligibility, availability and capacity. Thereafter

the plan will continue to be a transfer plan as to students

who have previously entered the system and who have

previously enrolled in grades higher than the first grade.

However, it will no longer be a transfer plan as to the

first grade, or as to the students who enter the first grade

under the plan, and as the first grade progresses through

the system it will cease to be a transfer plan as to all

students subsequently enrolling in the system.

Coming to Bush, supra, it was not until 1960, six years

after Brown, that a plan of desegregation was considered in

—14—

Louisiana. There had been extensive litigation involving

injunctions and contempts. The New Orleans plan involved

in Bush started at the first grade and was to progress

through the system at the rate of one grade per year. The

court said:

“If dual school system had been done away with in

first grade and plan of desegregating a year at a time

beginning with first grade had been initiated six years

after the 1954 desegregation decision, plan would have

complied with ‘deliberate speed’ concept established by

United States Supreme Court.” Id. 491.

312

Defendants’ Written Argument

Before the decision in 1962 the plan had been variously

dealt with by the trial and appellate courts, to enlarge and

then reduce the number of grades to which it would initially

apply, but as finally approved in 1962 by the Court of Ap

peals it embraced the first two grades, apparently to catch

up after a delay of one year, and subsequent progression

was at the rate of one grade per year. The vice in the plan

which caused it to be disapproved in part was that students

entering the first grade had to first register in a racially

segregated school and then seek transfer to another school.

The portion of this decision which was quoted by Mr.

Hollowell is relied on by him as condemning the Pupil

Placement Act of that State. The court referred to a 6th

Circuit case which tended to do so. However, the 5th Cir

cuit Court condemned the Act only “when, with a fanfare

—15—

of trumpets, it is hailed as the instrument for carrying out

a desegregation plan while all the time the entire public

knows that in fact it is being used to maintain segregation

by allowing a little token desegregation.” It condemned

the Plan only to the extent that it required the first grade

student to first register at a segregated school before he

could seek transfer to a non-segregated school.

All courts have referred to a transition period and to

“deliberate speed”. We do not think that decisions relating

to systems in New York or California have significant ap

plication to our local situation. They have their problems

and are the ones to deal with them. In our area transfer

plans during a transition period have consistently been ap

proved and have never been rejected because they were

transfer plans. Witness Atlanta. Counsel may have in

mind that this court should try to guess what the Supreme

Court may do in the Atlanta case now pending in that

313

Defendants’ Written Argument

court, or in the Virginia case argued at the same time, or

what the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals may do in cases

now pending in that court. We can only proceed on the

decided cases, plus the recognized fact that the judicial dis

cretion to be exercised is vested primarily in this court to

determine at what speed and over what period of time and

on what basis desegregation is to be accomplished in Bibb

County.

The Supreme Court recognized in Brown, and has recog

nized in all subsequent decisions, that time is required.

The plaintiffs themselves do so in the pre-trial order of

—16—

this court. This is not a denial of the Negro’s rights but

is a recognition that in common sense different conditions

in different parts of the country must be considered in

working out the plan under which those rights are realis

tically obtainable. Certain language of Justice Goldberg

in a recent case was quoted by Mr. Hollowell suggesting

that what would have constituted deliberate speed in 1954

is not necessarily the same thing today. We acknowledge

that. Actually the climate has somewhat changed, and that

which would have been hopelessly impossible then is now

possible. There is nothing in what Justice Goldberg said

or in what the Supreme Court has said which means that

the brakes should now be thrown away and all restraints

removed. It still is for this court to decide what constitutes

a reasonable and acceptable plan for Bibb County.

Many erroneous claims are made, some in this case, on

the basis of what the advocate thinks the Supreme Court

said and meant in the Brown case. Brown was interpreted

by the late Judge Parker of the 4th Circuit in Briggs v.

Elliott, 132 F. Sup. 776, as deciding only that a state may

not deny to any student on the basis of race the right to

314

Defendants’ Written Argument

attend any school that the state maintains, and this inter

pretation still stands. The state cannot deprive the student

on that basis of the right to choose.

In the Columbus case decided by Judge Elliott, a co

judge of this court, there are several pertinent statements

which we think bear quoting:

— 17—

“In testing the plan submitted we should remind

ourselves of a fact seemingly often overlooked by those

who are anxious for rapid social change, this being

that the chief function and primary concern of the

Board of Education is not the preservation of the

status quo in race relations, nor is it the advancement

of social revolution. The Board’s primary duty is to

provide good educational facilities and operate them

in an orderly manner and in an atmosphere free from

turmoil and tension. While it is this Court’s duty to

order an end to the segregated system, which we have

done, we deem it no less proper that we accord to the

local school authorities superior knowledge with re

spect to the mechanics of a plan and the timing of its

effectiveness.

* # * # #

“Counsel for the Plaintiffs have criticized the plan

as being an ‘illusion’, suggesting that this freedom to

register in the school of the pupil’s choice is not bona

fide and that those responsible for assigning the pupils

will hide behind a pretense of lack of building capacity,

absence of proximity and fictitious transportation

problems as justification for refusing to assign Negro

— 18-

pupils to the school of their choice. In other words,

we are asked to simply presume that the members of

315

Defendants’ Written Argument

the Board have submitted the plan hypocritically and

in bad faith. Let us consider this.

“Another contention of counsel for Plaintiffs is that

there is no guarantee under this plan that there will

be any actual integration of the races in the first grade

in the year 1964, counsel pointing out that there is no

assurance that any Negro child will choose to register

at what has previously been an all-white school. We

do not deem it the duty of the Board of Education to

enforce integration. We do deem it their duty not

to enforce segregation. By making it possible for

children of both races to choose the school which they

prefer to attend and by assigning the pupils to the

schools without regard to racial consideration the

Board will have discharged their duty.”

Judge Elliott refused to assume that the Columbus

Board would not proceed in good faith. Judge Elliott

found the plan submitted to be reasonable and adequate to

accomplish the desired results. It is also interesting to

note that Judge Elliott ruled, and we think correctly, that

—19—

the nominal plaintiffs in the Columbus case, of various

ages and grades, were not individually entitled to special

or separate consideration beyond the class which they rep

resent, and that they were not entitled to any different

treatment from that accorded to other children who are

members of the class which they represent.

Twelfth Grade versus First Grade Approach

It is not actually disclosed by the record that the plain

tiffs are questioning the 12th grade approach as against

316

Defendants’ Written Argument

the first grade apioroach, and it may he outside of the record

for us to say that there are differences of opinion on that

question. Plaintiffs would have the plan applied immedi

ately to all grades in the system. However, there is testi

mony in the record bearing on the question and we think

we should deal with it briefly.

Plans of both types have been approved as valid. Under

either approach there is a transition and a period of time

involved. Under either plan the test is not what the plan

does immediately, or by steps, but what it does ultimately.

If it were necessary to completely eliminate discrimination

immediately and abruptly neither plan would accomplish

that purpose.

Who is to say which is better? Under the first grade

approach a grade a year plan will never touch the students

presently in the system above the first grade. Under the

12th grade approach it will at some time touch every stu

dent presently in the system, commencing in 1964. Under

— 20—

either plan it will touch all students hereafter entering the

system.

The Board has decided that the 12th grade approach is

the better of the two, and has stated its reasons. Plaintiffs

have not really indicated a choice as between the two.

Accordingly we request that the 12th grade approach be

accepted by the court as a basic approach to desegregation.

Teachers, Principals and Administrative Personnel

Within the past year or slightly more it has become

routine to include in school petitions a prayer substantially

to the effect that in the assignment of teachers, principals

and administrative personnel the defendant Board be en-

317

Defendants’ Written Argument

joined from making such assignments on the basis of the

race. That prayer is contained in this case.

Generally the courts have considered it unnecessary to

rule on that question for the time being, deferring it for

later consideration. Witness Judge Elliott’s decision in

the Columbus case, and also in the Albany case, 222 F.

Sup. 166. A number of such cases are reported in the Fall,

1963, issue of Race Relations Law Reporter, Yol. 8, No. 3.

There are a number of reasons for this. One is that such

an order might be hopelessly incapable of enforcement.

Another is that it would be extremely difficult if not impos

sible even to frame such an order. Third, the question may

be more deliberately and properly considered at a later

- 21-

date. As classes are desegregated the question may become

moot.

Whatever the reason for deferment there are other seri

ous and vexing questions which have not been passed upon,

such as whether in a class action brought in behalf of school

children the civil rights of the classes are really involved.

Certainly the class does not include teachers or adminis

trative personnel and their rights cannot be asserted.. For

one treatment of the question along this line we refer the

court to the proceedings in Monroe v. Jackson, Tennessee,

which are reported in Race Relations Law Reporter, Yol.

8, No. 3, commencing at page 1008. The court said at page

1017, citing Mapp v. Board of Education of Chattanooga,

decided by the 6th Circuit on July 8, 1963, that the applica

tion for desegregation of supporting personnel should be

stricken completely as not included in the rights to be

protected, and that the plaintiffs could not assert the rights

of Negro principals and teachers, but that they could assert

(contend is a better word) that their own rights include

318

Defendants’ Written Argument

the desegregation of teachers and principals as part of

their right to an abolition of discrimination in the public

schools.

Actually plaintiffs in the counter-plan which they have

filed do not propose that this alleged right be dealt with

immediately, but merely propose to come back and deal

with it later. We have no reason to suggest any different

disposition. The court will undoubtedly retain jurisdiction

of the case and if the question should come up at some later

date it is entirely satisfactory to the Board to defer the

question until that time.

— 22—

Injunction

Whether or not an injunction should be granted can be

decided only on the basis of rules applicable generally to

the grant of injunctions. It is not a matter of absolute

right. Chief among these is the necessity for the injunc

tion. Injunctions have been granted in appropriate cases

and have been denied as unnecessary in others. Each case

must stand on its own facts.

If the Board should be enjoined in general language

from denying to the plaintiffs all rights guaranteed to

them by the Constitution the Board would immediately

be in violation of the injunction, because during the transi

tion period there is obviously a limited recognition of those

rights. If the injunction should be couched more narrowly

in terms of the order of this court there is absolutely no

reason for this court or for the plaintiffs to doubt that the

order will be complied with.

Furthermore, should any question arise at any time as

to the Board’s compliance either the complainants or the

defendants can return to this court for interpretation and

direction.

319

Defendants’ Written Argument

The only real purpose of an injunction would be to ex

pose the defendants to the perils of a contempt citation if

at any time it should act in a manner not thought by the

plaintiffs to constitute adequate compliance. When that

situation arises it will be time enough for this court to

grant whatever additional protective decree is necessary.

—23—

Conclusion

In conclusion we point to certain distinctions which we

feel should be clearly made.

Opposing counsel refers repeatedly to “complete” de

segregation, to a “uni-racial” rather than a “dual” system,

and to the integration of all school facilities at all levels,

including staff and teaching personnel. He speaks of these

things as something to which the plaintiffs are immediately

entitled, today rather than tomorrow, and as something

which can be afforded to them immediately, today rather

than tomorrow.

What we are really dealing with is a program, obviously

a program in steps, during the course of which over a

period of time their constitutional rights will be fully recog

nized and afforded.

Further it seems to us that counsel for the plaintiffs

misconceives the rights of the plaintiffs and the duty of

the Board. There is no State duty under the Constitution

to bring about integration. There is an affirmative duty

to abolish compulsory segregation. There is no affirmative

duty on the Board to eliminate all designations of people

or of schools by reference to race. It is implicit in the fact

that this case is before the court that the rights of Negroes

are designated as such. It would be absurd to close our

eyes to that fact. The rights asserted are claimed in behalf

of Negroes. The operation of a dual school system may be

320

Defendants’ Written Argument

material in passing on the validity of a plan, but is not

—24—

per se prohibited. What would constitute discrimination

may be determined in the light of the dual system. The

Constitution does not require that we forget or disregard

racial distinctions or identifications, but merely that we do

not discriminate on that basis.

I would like very much to invite the court to read the

proceedings in the Monroe case, supra, starting at page

1008 of the current Yol. 8, No. 3, of Race Relations Law

Reporter. Some eight or ten successive orders of the Dis

trict Court in that case are set forth. We have already

used some of the language appearing on page 1009 re

lating to compulsory racial integration. We particularly

invite attention to the language of Judge Brown’s decision

at page 1016 and at page 1020. We quote one paragraph

from page 1020:

“With respect to the contention that the law requires

more than an abolition of compulsory segregation

based on race and that it sets up an affirmative duty to

bring about integration, this Court heretofore had

occasion to point out in the Obion County, Tennessee,

school case, Vick v. County Board of Education of

Obion County, 205 F. Supp. 436, 7 R. Rel. Rep. 380

(WD Tenn. 1962) that the language of the Supreme

Court in the leading cases of Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, 347 U. S. 483, (1954) and 349 U. S. 294 (1955),

and Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958) does not sup

port this contention.”

—25—

We call to the attention of the court the fact that what

ever plan is now approved it is subject to review and pos

sible modification at a later date if the situation be-

321

Defendants’ Written Argument

comes such that a modification is indicated. We respect

fully submit that the Board has made a fair and reasonable

proposal for the commencement of a plan of desegregation

which in all respects complies with the deliberate speed

concept which has been announced by the Supreme Court,

and we urge the court to approve the Board’s plan as sub

mitted, including the implementing forms and documents

filed in connection therewith.

Finally, and in closing, we comment on the fact that

plaintiffs have offered no evidence on the trial of this case.

All of the documents and testimony in the record were

placed there by the Board. Defendants’ witnesses have

been cross examined, but their testimony has not been dis

credited. Certainly it is credible. It is not contradicted.

We realize that the burden is on the Board to support

the plan which has been proposed. We feel that we have

done so.

Respectfully submitted,

C. Baxter J oxes

C. Baxter Jones

1007 Persons Building

Macon, G-eorgia

Attorney for the Board

CBJ :R

322

Defendants’ Exhibit D-l

P E T I T I O N

To Bibb County School Board of (District No. or County,

State)

and

Superintendent of Schools of Bibb County

We, the undersigned, are the parents of children of school

age entitled to attend and attending the public elementary

and secondary high schools under your jurisdiction. Pur

suant to state law racially segregated public schools are

now being maintained by you for children of Negro parent

age. As you undoubtedly know, the United States Supreme

Court on May 17, 1954, ruled that the maintenance of ra

cially segregated public schools is a violation of the Con

stitution of the United States and that “. . . in the field of

public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no

place. Separate educational facilities are inherently un

equal.”

We, therefore, call upon you to take immediate steps to

reorganize the public schools under your jurisdiction in

accordance with the constitutional principles enunciated by

the Supreme Court on May 17. As we understand those

principles, children of public school age attending and

entitled to attend public schools cannot be denied admission

to any school or be required to attend any school solely

because of race and color.

We request a hearing before the Board for the purpose of

discussing this petition. We further wish to point out our

availability as parents and citizens of this community to be

323

Defendants’ Exhibit D-l

of whatever assistance we can to you in devising and im

plementing a program of desegregation in accordance with

the Supreme Court’s decision.

We are further authorized to advise you that Macon

Branch of the NAACP at a membership meeting on 11

November, 1954, voted to offer its services to the Board to

aid you in the implementation of a plan of desegregation,

and we request that Dr. J. S. Williams, President of the

Branch, be notified of the date of the meeting on this peti

tion and be invited to be present.

[Signature omitted]

324

Defendants’ Exhibit D-2

P E T I T I O N

TO: School Board of Bibb County

(District No. or County)

and

Superintendent of Schools

We, the undersigned, are the parents of children of school

age entitled to attend and attending the public elementary

and secondary high schools under your jurisdiction. As

you undoubtedly know, the United States Supreme Court

on May 17, 1954, ruled that the maintenance of racially seg

regated public schools is a violation of the Constitution of

the United States and on May 31, 1955 reaffirmed that prin

ciple and requires “good faith compliance at the earliest

practicable date” with the federal courts authorized to de

termine whether local officials are proceeding in good faith.

We, therefore, call upon you to take immediate steps to

reorganize the public schools under your jurisdiction on a

nondiscriminatory basis. As we understand it, you have

the responsibility to reorganize the school system under

your control so that the children of public school age attend

ing and entitled to attend public school cannot be denied

admission to any school or be required to attend any school

solely because of race and color.

The May 31st decision of the Supreme Court, to us, mean

that the time for delay, evasion or procrastination is past.

Whatever the difficulties in according our children their

constitutional rights, it is clear that the school board must

meet and seek a solution to that question in accordance with

325

Defendants’ Exhibit D-2

the law of the land. As we interpret the decision, you are

duty bound to take immediate concrete steps leading to

early elimination of segregation in the public schools.

Please rest assured of our willingness to serve in any way

we can to aid you in dealing with this question.

Please sign:

[Signatures omitted]

326

Defendants’ Exhibit D-3

PRELIMINARY REPORT OF SPECIAL COMMITTEE

There has been filed with this Board two petitions pro

posing integration of the races in our schools. One of these

petitions was filed some months prior to the implementing

decision of the Supreme Court of the United States in May

1955, and was obviously premature. The second petition,

undoubtedly filed in recognition of the prematurity of the

first, was filed with the Board on August 25, 1955, and we

take as superseding the first petition. On September 6,1955

(prior to any meeting of the Board after receipt of the sec

ond petition) a letter reciting that it was written in behalf

of the petitioning parents was received by the Board. It

requested an answer from this Board (in the nature of a

commitment) as to this Board’s concern with the matters

contained in the letter and the petition.

That court decision specifically states that as to the

“varied local school problems, school authorities have the

primary responsibility for elucidating, assessing and solv

ing these problems.” It further provides that consideration

shall be given to “problems related to administration, aris

ing from the physical condition of the school plant, the

school transportation system, personnel * # * and revision

of local laws and regulations which may be necessary.”

Of course, for some months (and prior to the filing of

any petition) the members of this Board have concerned

themselves over the situation referred to, and at the present

time this committee is charged with the specific task of in

vestigation and report; but in our considered judgment any

commitment by this Board at this time, or at any time before

completion of such study of the overall situation as this

Board may find necessary, would be inappropriate, unwise

327

Defendants’ Exhibit D-3

and entirely out of harmony with the intent of the Supreme

Court decision.

This being the first meeting of the Board since the ap

pointment of this committee, we wish to report at this time

that it is the opinion of the committee that to properly fulfill

the assignment given it by the Board and to cover all of the

complexities and ramifications involved will require an

amount of time, effort and study, the extent of which we

cannot presently appraise.

Before this committee proceeds further toward the per

formance of the task assigned, we felt it proper to submit

this preliminary report.

Respectfully submitted,

McK ibben Lane

W allace Miller, J r.

Charles C. H ertwig

George P. Rankin, Jr.

J . D. Crump, Ex-officio

Mallory C. Atkinson,

Chairman Committee

328

Defendants’ Exhibit D-4

MACON COUNCIL ON HUMAN RELATIONS

391 Monroe Street Macon, Georgia

February 23,1961

Dr. H. G. W eaver, President

Bibb County Board of Public Education and Orphanage

700 Spring Street

Macon, Georgia

Dear Dr. Weaver :

At its regular meeting on February 20, 1961, the Macon

Council on Human Relations unanimously adopted the en

closed resolution.

Since the Macon Council is an interracial organization

and has traditionally interpreted its role and function as

that of promoting good human relations, we feel that we

are strategically oriented to help preserve order and good

will in the period of transition which most certainly lies

ahead of us. We would, therefore, be pleased to know of

any way in which we could be of assistance to you or any

other governmental official in the implementation of the

transition called for by this resolution.

Thanking you very much for your sympathetic considera

tion of this matter, we are

Respectfully yours,

/ s / E. B. P ascal

E. B. Pascal, Co-chairman

/s / J oseph M. H endricks

J oseph M. H endricks, Co-chairman

Macon Council on Human Relations

329

Defendants’ Exhibit D-4

STATEMENT

The new realism in Georgia’s official approach to the con

stitutional prohibition against racial discrimination by action

of state and local governments as enunciated by the Su

preme Court calls for a re-examination of the policies, prac

tices and plans for the future of each community within our

state. The Macon Council on Human Relations respectfully

suggests to the authorities of the City of Macon and of Bibb

County, including the Bibb County Board of Public Educa

tion and Orphanage, that such a re-examination here not

only is logically called for as a result of changed state laws

and abandonment of a state legal stance of unflinching re

sistance, but that it is imperative to continued well being

and to the preservation of the traditional racial harmony of

our community.

We fully recognize that our state officials came reluctantly

to the present stance. However, regardless of one’s stand,

it appears most unlikely that any early reversal of the court

interpretation of the law is in prospect, and the new realism

has compelled our political leadership to recognize that

compliance with federal court orders is unavoidable, since

armed resistance is the only alternative and is obviously

futile and unthinkable. As one Georgia editor has said,

“Absurdities, pro or con, in the racial field are becoming

casualties of the new era in Georgia.”

Our local officials generally have supported the state po

sition before the new realism, though they have been far

less vocal than most politicians on the state level and in

many other localities in Georgia. Some of our officials have

worked to promote a continuance of racial harmony in the

community and those who have made no real contribution

in this respect at least have done nothing to stir ill feeling,

with the amazing exception of a pronouncement last year

from a high judicial quarter.

330

Defendants’ Exhibit D-4

To this date there have been no incidents in Macon and

Bibb County of the sort which have disturbed other South

ern communities, such as bus boycotts, sit-in demonstra

tions, demands for admission to golf courses, libraries,

swimming pools and other governrnentally-operated serv

ices. Some of Macon’s Negro citizens and some of their

more dedicated white friends react with shame to this fact,

believing they should have acted “to secure these rights,”

as a report in the 1940’s put it. But the temper of our com

munity so far has preserved the status quo. That this can

not continue unchallenged now is apparent. With the full

backing of federal authority, some change is bound to come.

The question in Macon, as in all of Georgia, no longer is

whether we can continue as in the past. It is whether change

will come under community planning and control, or whether

it shall come under the explicit direction of a federal court.

The Macon Council on Human Belations is successor to

an organization which has existed in this community for

many years—long before the present crises and contro

versies arose—and it has been essentially conservative in

the best sense of that often-abused term. During the past

years when defiance and resistance-at-all-costs were the offi

cial policy of Georgia, we made no public effort to reverse

a trend which was quite apparently beyond our power to

influence. We spoke out only occasionally and then only in

specific instances of injustice which we felt demanded a

voice against the tide.

Now that realism is the order of the day in Georgia and

absurdities are casualties of the new era, we believe that

the time has come to make a truly conservative voice heard

in Macon and Bibb County.

That our Negro citizens soon will make new demands for

compliance locally with rules of law which have been laid

331

Defendants’ Exhibit D-4

down time and again by the federal courts, both the Supreme

Court and our own Middle District of Georgia and Fifth

Circuit Court of Appeals, is beyond question. It equally is

beyond question that under these legal interpretations

many of our local practices are highly vulnerable. Our

community can continue to operate and control its essential

and desirable services to all its people—if our officials will

begin now to plan for an orderly transition. Any other

course can only result in irreparable harm to us all, and it

will matter not at all on whom the blame is placed.

Our local school problem is a case in point. It is well

known that some of our legal worthies have argued that the

1872 charter of our board of education would be voided by

integration or that the Alexander Schools would be for

feited. These arguments, if pursued, could close our local

schools even though state law has been changed and in the

face of strong local sentiment for continuing public educa

tion. The closure would be temporary, but of dire conse

quence. If absurdities really are casualties these days, this

folly will be avoided.

We call upon our mayor and council, the board of county

commissioners, all county officials, the board of education,

our state and local judges, and our state legislators to join

immediately in planning to meet the new era with sense and

realism on the local scene.

332

D e fe n d a n ts ’ E x h ib it D-5

DR. H. G. WEAVER

700 Spring Street

Macon, Ga.

February 27,1961

E. B. Paschal and Joseph M. Hendricks, Co-Chairmen

Macon Council On Human Relations

391 Monroe Street

Macon, Georgia

Dear Sirs:

This is to acknowledge receipt of your letter and state

ment of February 23, 1961. This will be referred to the

proper committee for study and if we need your help we

will call on you.

Tours truly,

HGW/w

/ s / H. G. W eaver

H. G. Weaver, M. D.

D e fe n d a n ts ’ E x h ib it D-6

845 Forsyth Street

Macon, Georgia

March 8, 1963

Dr. H. G. Weaver, President

Board of Education and Orphanage of Bibb County

Macon, Georgia

Dear S ir:

We the undersigned, hereby request the privilege of appear

ing at the next duly constituted meeting of the Board of

Public Education, for the purpose of airing certain griev

ances pertaining to public education in Macon and Bibb

County.

We firmly believe that the alleviation of the conditions which

gives rise to our grievances is in the best interest of our

community, and therefore demand your attention.

May we hear from you at your earliest convenience, regard

ing our appearance at the next Board Meeting.

Sincerely yours,

/« / Rev. E. S. E vans

/ s / W alter E. Davis

/ s / Lewis PI. W ynne

/ s / J . L. K ey

/ s / W illiam P. Randall

/ s / B. W. Chambers

/ s / T. M. J ackson

334

Defendants’ Exhibit D-6

March. 12,1963

R ev. E. S. E vans

Mr. W alter E. Davis

Mr. L ewis H. W ynne

Mr. J . L. K ey

Mr. W illiam P. R andall

Mr. B. W. Chambers

Mr. T. M. J ackson

845 Forsyth Street

Macon, Georgia

Dear Sirs:

This will acknowledge receipt of your letter of March 8,

1963.

Your request comes rather late for an appearance at our

meeting on Thursday of this week. Our agenda is already

set for this meeting, hut if you desire to appear at this time

we will rearrange our business and allow you five minutes

if you can arrive promptly at 4:30 p.m.

However, it would be more in keeping with the procedure

of our Board if you would present your matters in writing.

This would then be assigned to the appropriate committee

for recommendation to the Board. Or if you will present

your views in writing the committee to whom it will be re

ferred could undoubtedly give you more time for presenta

tion of your matters prior to our regular April meeting.

335

Defendants’ Exhibit D-6

If the time we can allow you at our Thursday meeting is

not sufficient for you to present what you have, we could

arrange more time for you at our April meeting.

Yours truly,

Ii. G. "Weaver, President

Bibb County Board of Education

HGW/JGr/s

Blind copies: Mr. Miller

Mr. Baxter Jones

336

D e fe n d an ts ’ E x h ib it D-7

Macon, Georgia

March 14, 1963

Mr. Chairman and Gentlemen of the Board:

We would like to present a petition from adult citizens of

Bibb County, relative to the present status of the school

system.

We had hoped that after presenting this petition we might

be able to discuss with you some of the reactions in the

Negro community on this subject; and to submit ourselves

to questioning from you gentlemen. But with a restriction

of five minutes to do these things is impossible. We would

wish that we could convince you gentlemen that we are

desperately anxious to have this situation resolved by the

board and local citizens, rather than by the Federal Courts.

We appreciate your suggestion that we reduce this matter

to writing for referal to a proper committee. But we would

respectfully remind you gentlemen that we did this very

same thing nine years ago. The matter was refered to a

committee. Said committee seems to have been the grave

yard for the petition, as we have heard nothing from this

committee as of this very moment.

You can appreciate the fact that time is of the essence in

this instance, and to delay our appearance until your next

meeting might have seriously restricted us in our efforts

to have this matter settled by the next September term of

school.

337

Defendants’ Exhibit D-7

PETITION

We the undersign, being adult citizens of the United States

residing in or around the city of Macon and Bibb County

Georgia, do hereby petition the members of the Bibb County

Board of Education and the Superintendent of Schools of

such Board to take notice of the following:

1. That on May 17, 1954, the United States Supreme

Court in the decision titled Brown v. Board of Education,

held that racial segregation in the public schools is a viola

tion of rights guaranteed to Negro citizens by the Four

teenth Amendment of the United States Constitution.

2. Since 1954, a period of almost nine (9) years, the

Board of Education of Bibb County has continued to op

erate on a completely segregated basis. The public schools

in Macon and Bibb County, with Negro children and teach

ing personnel being assigned to schools designated solely

for Negroes, and white children and teaching personnel

being assigned to schools designated solely for whites.

3. The operation of the public schools by the Bibb County

Board of Education on a racially segregated basis consti

tutes a continuing violation of the constitutional rights of

all Negro children forced to attend such racially segregated

schools.

Therefore, the undersigned persons petition the Bibb

County Board of Education to take immediate action to

comply with the decision of the United States Supreme

Court and to desegregate the public schools of Macon and

Bibb County, Georgia, and to inform the undersigned peti

tioners what plans have been formulated to achieve such

desegregation.

We would therefore request that you place this matter on

the agenda of your next Board meeting and consider same

as soon as possible.

338

D e fe n d a n ts ’ E x h ib it D-8

Law Offices

JONES, SPARKS, BENTON & CORK

P ersons B uilding

Macon, Georgia

April 13,1963

Mr. Wallace Miller, Jr.

Chairman, Special Committee

Bibb County Board of Education

Macon, Georgia

Dear Wallace:

My opinion as attorney for the Board of Education has

been requested with reference to the matters indicated

below.

The Bibb County Board was chartered by the Georgia

Legislature in 1872, to direct and control the education in

Bibb County of white and colored children between the ages

of six and eighteen.

As a body corporate the Board is a creature of the State.

It has no rights of property and no powers except those

granted to it by the State. It exists as a corporation within

the control of the State and subject to such conditions and

restrictions as are imposed by the State. To clarify the

point, we are not concerned with what the State can or can

not do in the area of public education but solely with the

question what the State has authorized the Bibb County

Board to do, and within what limitations, restrictions and

conditions.

339

Defendants’ Exhibit D-8

Section 5 of the Board’s charter reads as follows:

“See. 5. That the said Board shall establish distinct

and separate schools and orphans’ homes for white and

colored children, and shall not, in any event, place chil

dren of different colors in the same school or orphans’

home.”

The immediate question is whether this limitation in the

Board’s charter is valid or invalid. If we assume it to be

invalid, or that it will be so held, the question remains

whether the Board under its charter has the power from

the State to operate the Bibb County school system con

trary to this provision in its charter. Bestated in blunt

language, the question is whether the power given to the

Board to operate segregated schools is a power to operate

non-segregated schools if segregated schools cannot be op

erated because of the invalidity of Section 5.

The following rules may be stated as rules of general

application. If desired they can be amply supported.

(1) Where a statute (in this case the Board’s charter)

is partly unconstitutional it will nevertheless be upheld as

to that part which is constitutional if the constitutional

part standing alone is sufficient to accomplish the legislative

purpose and does not contravene that purpose.

(2) If the unconstitutional part is indispensable to the

legislative purpose the whole statute must fall.

(3) If a statute is in part valid and in part invalid, and

the invalid part is so connected with the general legislative

intent that without it the legislative intent cannot be accom

plished, or can be accomplished only in a manner which

contravenes the legislative intent, the whole statute must

fall.

340

Defendants’ Exhibit D-8

These general rules could be restated with varying em

phasis, but the question which they pose is rather obvious.

If a main purpose of the 1872 Act was to provide separate

schools for white and colored children that purpose is de

feated if white and colored children are educated in the

same schools. If “the” main purpose was to provide for

the education of children, the separation of the races being

incidental or secondary to the main purpose, then the limita

tions of Section 5 are incidental and secondary and the

invalidity of that section does not void the Act as a whole.

Was the purpose to provide an education or was it an

essential part of the purpose that education be provided

in separate schools for white and colored children? The

meaning of Section 5 is clear but whether it is essential to

the Act as a whole is debatable on either side.

If Section 5 is so connected with the legislative purpose

that no power is granted to the Board except under the

conditions of that section then the entire charter stands or

falls with that section. The result is the same whether the

Board voluntarily violates Section 5 or does so under court

order, viz., the possible complete loss of the Board’s cor

porate powers and the forfeiture of its charter.

Since the Board’s powers are derived from the State the

interpretation of its charter powers is essentially a state

and local question. Ordinarily a federal court will permit

such questions to be decided by the state courts if that is

practical, and will be bound by the state court rulings, but

where the construction of a state statute is involved in a

case properly pending in a federal court there is no doubt

that the federal court may itself construe the statute and

its construction will bind the parties to that particular ease.

It probably would not protect the parties as against others

who are not parties.

341

Defendants’ Exhibit D-8

The gravity of the question cannot be overstated. If the

Board acts in violation of Section 5, either voluntarily or

under federal court order, by placing white and colored

children in the same school it might thereby forfeit its

charter, completely destroy itself, and leave no other local

state agency to act in its place, thus disrupting the whole

school system in Bibb County. This could follow whether

the Board acts voluntarily or under the decree of a federal

court. That is, regardless of the construction placed on

the charter by a federal court the state would not thereby

be deprived of its right to forfeit or revoke the charter.

In addition to the effect on the Board’s charter, possibly

voiding its powers to receive and expend school funds, and

affecting its titles, the individual members of the Board,

and the Board’s agents and employees, would find them

selves acting at their individual perils.

There is no particular point in my stating how I would

decide this question if I had to make a decision. I might

study it further and come up with some sort of answer.

The point is that no authoritative answer can be given. It

can be argued with some persuasion that Section 5 is so

much a part of the legislative purpose that the Board has

no powers which can be exercised if the conditions of that

section are stricken out. On the other hand it can be argued

with some persuasion that Section 5 is so far secondary to

the main purpose that it may be stricken without otherwise

affecting the powers of the Board.

It may be that irrespective of the answer itself the Board

is bound to observe its own charter conditions. As between

the State and the Board the conditions of the charter are

binding and the Board cannot challenge or deny the validity

of its own charter. To voluntarily mix the races in the

342

Defendants’ Exhibit D-8

same schools would constitute a denial by the Board of the

validity of Section 5 of its charter, or on any other ground

would be a deliberate violation of that section.

I am sorry that I cannot supply more definite answers,

but I believe you are aware that some measure of doubt

and uncertainty will remain until the answers are supplied

by an authoritative court ruling.

Yours truly,

/s / C. Baxter J ones

C. Baxter Jones

CBJ:B

343

D e fe n d a n ts ’ E x h ib it D-9

REPORT OF

RULES AND REGULATIONS COMMITTEE

AND SPECIAL COMMITTEE

Tlie President of the Board referred to these two com

mittees, for recommendation to the full Board, the petition

of certain citizens of Bibb County, Georgia, pertaining

to the Board’s operation of the public schools of Bibb

County on a basis of separate schools for white and

colored children.

The Board has only such authority as is contained in its

charter.

Section 5 of its charter provides:

“That the said Board shall establish distinct and

separate schools and orphans’ homes for white and

colored children, and shall not, in any event, place

children of different colors in the same school or

orphans’ home.”

The two committees were and are gravely concerned

as to whether, within the charter powers granted by the

State of Georgia, the Board, as distinguished from the

State, can legally operate schools other than separate

schools for white and colored children.

Legal counsel of the Board was consulted on this ques

tion, and such counsel advises that no definite resolution

of the question can be had without an adjudiction by a

court of competent jurisdiction, with proper parties be

fore it, and such counsel recommends the Board initiate

such action.

The two committees concur in the recommendation of

the Board’s counsel, and hereby recommend to the full

Board the adoption of the following resolution:

344

Defendants’ Exhibit D-9

“Be it resolved by the Board of Public Education and

Orphanage for Bibb County that its counsel forthwith

institute in the name of the Board, against such parties

as such counsel deems necessary, a court action in the

Superior Court of Bibb County, Georgia, to obtain an

adjudication from such court as to whether the Board can

legally operate schools other than separate schools for

white and colored pupils, as provided in its charter.”

So recommended to the full Board, this April 24, 1963.

R ules and Regulations Committee

B y /&/ W m. A. F ickling

Chairman

Special Committee

B y / s/ W allace Millek, J r.

Chairman

345

D e fe n d a n ts ’ E x h ib it D -10

State of Georgia

County of B ibb

To the Superior Court of Said County:

The petition of the Board of Public Education and

Orphanage for Bibb County, a corporation, respectfully

shows: 1.

It was incorporated by an Act of the General Assembly

of Georgia approved August 23, 1872, entitled:

“An Act to establish a permanent Board of Educa

tion and Orphanage for the County of Bibb, and to

incorporate the same; to define its duties and powers,

and for other purposes.”

Its principal and only office is located in Bibb County,

Georgia.

2.

This petition is brought by proper action and resolution

of the petitioner, invoking the power of the Court to de

clare rights and other legal relations of your petitioner.

Tour petitioner shows to the Court that the ends of justice

require that such declaration should be made.

The petition is brought also in an invocation of the

visitorial power over corporations which is vested in the

superior court of the county where such corporation is

located.

This visitorial power vested in the superior courts of

the counties where corporations are located empowers them

to decide controversies pertaining to the proper exercise

of the charter powers of such corporations.

346

Defendants’ Exhibit D-10

3.

Certain Negro citizens residing in Bibb County, Georgia,

have filed their petitions with your petitioner in which

they assert that the public schools directed and controlled

by your petitioner are operated on a segregated basis,

that is, with Negro children being assigned to schools

designated for Negroes, and white children being assigned

to schools designated for whites.

These Negro citizens have requested your petitioner to

take action toward desegregating the public schools of

Bibb County, Georgia.

4.

Among the Negro citizens who have so petitioned your

petitioner are E. S. Evans, Walter E. Davis, Lewis H.

Wynne, J. L. Key, Wm. P. Randall and B. W. Chambers,

all of whom are residents of Bibb County, Georgia. They

are named as defendants herein as representatives of the

class of persons so petitioning.

5.

Since its incorporation in 1872, your petitioner has stead

fastly and conscientiously sought to perform the duty with

which it was charged by Sections 1 and 2 of the Act afore

said, and specifically to direct and control the education

of white and colored children in Bibb County between the

ages of six and eighteen years; and to provide a system

of education for white and colored children of said ages

in said county.

6.

In the performance of its duties, and in its direction and

control of the education of white and colored children in

347

Defendants’ Exhibit D-10

said county, your petitioner lias for over ninety years

observed the explicit provisions of Section 5 of its charter

as contained in the aforesaid Act, which are:

“That the said board shall establish distinct and

separate schools and orphan homes for white and

colored children, and shall not, in any event, place

children of different colors in the same school or

orphan home.”

7.

Petitioner has been advised by its counsel that it is doubt

ful whether it has the corporate power under its charter

to grant the petitions aforesaid, and thus operate a system

of public schools other than as prescribed in Section 5 of

its charter, to-wit, a system of distinct and separate schools

for white and colored children, and petitioner is in doubt

whether it does or does not have this power.

8.

More succinctly stated, petitioner is in doubt whether its

grant of corporate powers from the State of Georgia to

operate a system of public schools for white and colored

children in Bibb County is so far conditioned upon com

pliance with the limitations and restrictions of Section 5

of its charter that it may not exercise its powers, and has

no powers which it may lawfully exercise, in any other

manner, that is in a manner which violates the limitations

of said Section; or whether if separate schools cannot be

established as required by said Section powers are granted

under which public schools may be established and oper

ated by petitioner under its charter in disregard of said

Section.

348

Defendants’ Exhibit D-10

9.

In the absence of an authoritative construction of its

charter by this Court, in specific relation to the foregoing

questions as to which petitioner is in doubt, petitioner can

act in the premises only at its peril; in that its charter might

be subject to forfeiture if it grants the petitions aforesaid,

and in that all of its acts in such event might be invalid and

ultra vires and the entire operation of a system of public

schools in Bibb County might be threatened. The individ

uals who comprise petitioner, and who exercise petitioner’s

public and corporate functions and powers, can act only at

their peril as such members, and are in danger of incurring

individual liability if they act beyond petitioner’s powers.

10.

Section 3 of petitioner’s charter aforesaid provides in

part:

. . and said board shall further have the power to

assess such tax upon the taxable property of said

County of Bibb as they may think necessary to support

the system of schools and orphan homes which they may

establish, which tax when approved by the grand jury

at the spring term of the Superior Court of Bibb

County, shall be levied by the Ordinary of said County

and collected like other taxes of said county.”

By an amendment to petitioner’s charter approved Feb

ruary 19, 1876, the words “grand jury at the spring term

of the Superior Court of Bibb County” were stricken and

the words “Board of County Commissioners of Bibb

County” were substituted, and the words “and the said

Board is hereby required to approve or disapprove of said

349

Defendants’ Exhibit D-10

tax before the first Monday in Jane of each year” were

added at the end of said Section. Under said Section funds

received by petitioner from the levy of taxes as therein pro

vided, and from other sources mentioned in said Section,

are used by petitioner for the operation of the public schools

of Bibb County, and because of the uncertainty as to peti

tioner’s powers the danger also exists that petitioner will

not be able to lawfully levy taxes for the support of the

system of schools or receive and expend school funds for

such purpose.

11.

If petitioner, by unanimous vote or by majority vote,

should grant the aforesaid petitions, and place children of

different colors in the same school or schools contrary to

the provisions of Section 5 of its charter, petitioner faces

the probability, if not the certainty, of judicial proceedings

against petitioner and the individual members of petitioner,

and against petitioner’s agents and employees, challenging