Plaintiffs Exhibit Proposals for School Integration and Desegregation

Public Court Documents

November 24, 1970

14 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Plaintiffs Exhibit Proposals for School Integration and Desegregation, 1970. ca89ee6d-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4f40fea4-ce46-4524-b7a0-eeee471edb05/plaintiffs-exhibit-proposals-for-school-integration-and-desegregation. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

7?

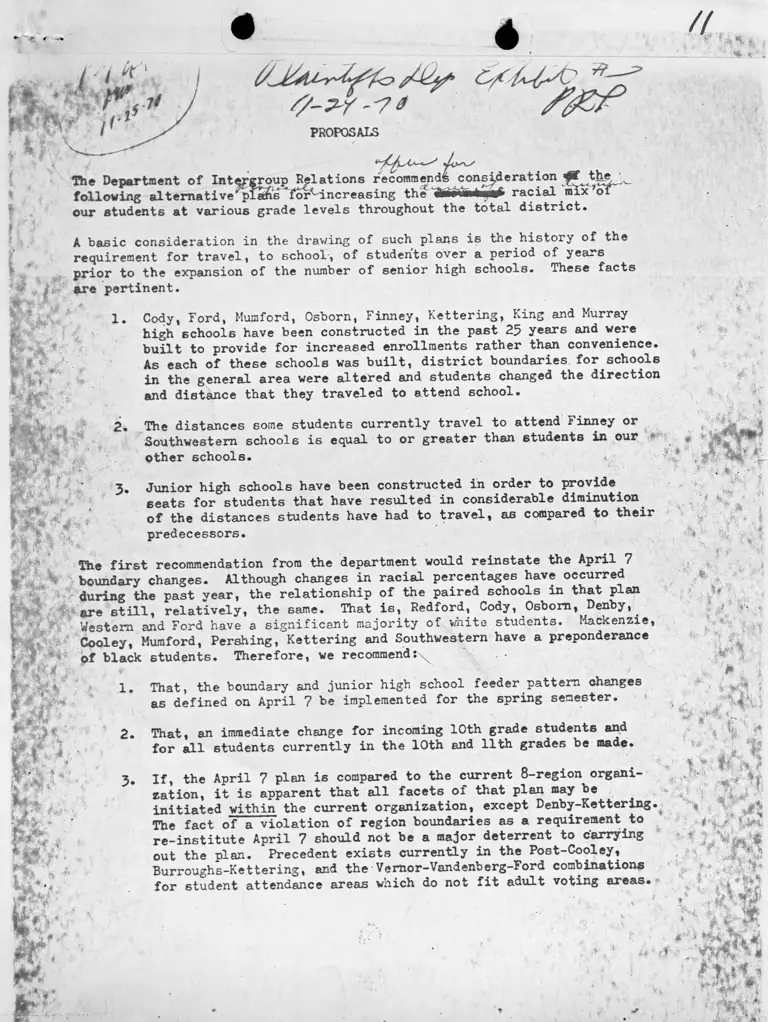

PROPOSALS

<Lo>ŝS

The Department of Intergroup Relations recommends consideration

^ ^ " ‘fSrMncreasing th^ifati^itW racial raix*of^following alternative'pi sens forVincreasing

our students at various grade levels throughout the total district*

A basic consideration in the drawing of such plans is tne history of the

requirement for travel, to school-, of students over a period of years

prior to the expansion of the number of senior high schools. These facts

are pertinent.

1. Cody, Ford, Mumford, Osborn, Finney, Kettering, King and Murray

high schools have been constructed in the past 25 years and were

built to provide for increased enrollments rather than convenience.

As each of these schools was built, district boundaries, for schools

in the general area were altered and students changed the direction

and distance that they traveled to attend school.

2. The distances some students currently travel to attend Finney or

Southwestern schools is equal to or greater than students in our

other schools.

3. Junior high schools have been constructed in order to provide

seats for students that have resulted in considerable diminution^

of the distances students have had to travel, as compared to their

predecessors.

The first recommendation from the department would reinstate the April 7

boundary changes. Although changes in racial percentages have occurred

during the past year, the relationship of the paired schools in that plan

are still, relatively, the same. That is, Redford, Cody, Osborn, Denby,^

Western and Ford have a significant majority of white students. Mackenzie,

Cooley, Mumford, Pershing, Kettering and Southwestern have a preponderance

of black students. Therefore, we recommend:x

1. That, the boundary and junior high school feeder pattern changes

as defined on April 7 be implemented for the spring semester.

2. That, an immediate change for incoming 10th grade students and

for all students currently in the 10th and 11th grades be made.

3. If, the April 7 plan is compared to the current 8-region organi

zation, it is apparent that all facets of that plan may be

initiated within the current organization, except Denby-Kettering.

The fact of a violation of region boundaries as a requirement^to

re-institute April 7 should not be a major deterrent to carrying

out the plan. Precedent exists currently in the Post-Cooley,

Burroughs-Kettering, and the Verhor-Vandenberg-Ford combinations

for student attendance areas which do not fit adult voting areas.

*■"' - > <9 4

\

f -

i&

■t

Vv

* 1

Jt

M

w •

' »v»f■V

> . ■ f I

- 2-

In the effort to maximize the amount of integration, we recommend that

junior high schools be paired in such a manner as in the following examples:

1. The pattern of alternate grades attending each school be

instituted in the following schools:

Richard-Von Steuben-Burroughs, Goodale-Joy, Farwell-Grant,

Earhart-Pelham, Condon-Wilson, Drew-Brooks-Ruddiman,

Etoerson-Winship, Nolan, Farwell1', Grant and further that

additional schools be added, if possible to this list.

A third alternative would be to close, as regular junior or senior high schools,

those schools with seriously declining enrollments, and reorganize them as

specialized'trade schools or as experimental "open” schools with a city-wide

enrollment. Some of these school plants might be:

Durfee, Longfellow, McMichael, Hutchins, Northeastern, Murray,

Chadsey and Northern.

In each case cited, the neighboring schools have capacity to share or absorb

entirely the enrollment of the school to be closed. Each of these schools

has availability to public transportation which would allow them to function

a6 a magnet school. For instance, the relationship with Michigan Bell Telephone

Company and Northern High School might be better exploited by the school's role

as a magnet school with a city-wide draw. The existence of such schools with a

free and open transfer policy would act as a pressure relief for those parents

and students now in serious disagreement with the program of the "comprehensive”

high school.

*

-

"H M *■ ■ *■

Some principles of the magnet school concept are as follows:

1. The school program must be so planned that it will receive

recognition as one of real strength and special value to students,

cleanly superior in one or more vital respects to the neighborhood

high school.

2. Such schools would utilize innovative and sound patterns of organi

zation, curriculum, student government, personnel, housing and other

areas of school life.

• * • • a*

3. The name of the school should be changed, so it is no longer identified

as an old neighborhood school, and it is viewed as a new school identified

with a new and most promising specialized program.

k. Attention should be directed to the lines of transportation, to insure

that students and parents would consider these among the best and most

desirable.

5. The student and staff membership must be well integrated racially.

;

Hi

Hr r

^ it? #

J v * 4 *

- >

6m The school should be advertised as open to suburbanites. There may well

be some objections, however, the advantages derived would clearly out

weigh the objections. The enrollment of a number of suburbanites would

do wonders for the schools image and reputation.

7. The school would have a free and open transfer policy, crossing

regional and even district lines.

8. These schools could be given some special prestigious label, such as

"the metropolitan schools."

m s

k %

In response to the NAACP appeal to the court for a structured student ratio

reflective of the city enrollment as a whole, the Department of Intergroup

Relations recommends the practices below:

1. One approach might be a bussing structure as demonstrated in

Berkeley, California, a cross-bussing of grades with a series

of planned steps as detailed in the many reviews of that plan.

This plan would require considerable logistical preparation,

community preparation and professional staff orientation.

Appropriate descriptions of the Berkeley plan may be found in the

attached articles.

2m Some principles which ought to apply to such a plan are as follows!

%

— schools with up to bO% of either race would not be involved

in the pairing program

— all schools to be paired should involve all of the children

in order to build identification with the program.

ft

•

V- r'. ■ % "* I <

fT\

J Mi.

f *

f iN $

m

.. ‘ * *

ml

f 4 *

■ - k

$■ % ■ if

v j

; i 'V >1

f - A %

) t * ‘

- 'W,

*, - f .

$ 4 ' % i

i p f . i

- i'

* '• 4, f f

: i f ]w

J ^ # 'f I

$

I

I

f

Y 7-? *

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. School Management

November, 19^^ •*

"When the Buses Began to Roll" by Don Wegars

2. Phi Delta Kappan

March, 1968

"Should Administrators Seek Racial Balance in the Schools?" by Neil Sullivan,

$, r\

fV * 4.

i

f *

f /. ;*,%

:

5.

6.

r . -

4

t •

4',"

I <•>»•

> V

* ' * ■ •- :

t,' .

*'* , A,

| if

L#

V-

* ■ Si

Phi Delta Kappan

May, 19^9

"A Landmark in School Racial Integration: Berkeley, California” by Mike M.

Milstein and Dean E. Hoch

Nation’s Schools

September, 19^7

"These Integration Approaches Work— Sometimes" by Robert J. Havighurst

CTA Journal

January, 1969

"The Black Tree That Grows in Berkeley" by Harold J . Maves

* -

« 1,ri- t

The Instructor

January, 19 69

"Follow Through in Berkeley" by Louise C. Brown

November 2, 1970^ c {aA ^

■ / / ~ 3 - y - 7 / J

PBOPOSALS IN THE HATTER OF SCHOOL INTEGRATION

Submitted by

DIVISION OF SCHOOL-COMMUNITY RELATIONS

w>^.*V

The Department of Intergroup Relations offers for consideration the

following alternative proposals for increasing the degree of racial

desegregation at various grade levels throughout the total district.

Certain fundamentals must be taken into account in planning alternatives:

(l) the amount of racial mix of students and (2) the degree to which

regional boundaries are held inviolate so that parents can vote and help

to determine policies of the schools which their children attend. The

following five (5) proposals are offered for consideration.

Proposal 1:

Implementation of April 7 plan as originally conceived as of

February, 1971* Although changes in racial percentages have

occurred during the past year, the relationship of the paired

schools in that plan are still, relatively, the same. That is,

Bedford, Cody, Osborn, Denby, Western and Ford have a significant

majority of white students. Mackenzie, Cooley, Mumford, Pershing,

Kettering and Southwestern have a preponderance of black students.

Advantages:

1.

2.

Minimizes violence to decentralization. Only Denby-KAtterixig

fail to fit within the regional boundaries as presently drawn.

A greater racial mix will occur than presently exists at the

high school level.

-

■ t

* $

y v

it$

& :■ A

■

W: i

r. ■' 'ffi-

M; '

m ’

,

I ■ *Disadvantages:

1. No steps are planned in this proposal for increasing integration

at the junior high school and elementary school levels.

...., ... , jjf2. Adequate planning time for implementation of this proposal is

missing. If the proposal is to be successful, in-service training V *

programs to develop the instructional curricular and attitudinal

changes must be instituted. Involvement of the affected communities

in all of the preparatory steps would also be of crucial importance

and this, too, would lengthen the planning process.

Proposal 2 :

Implement April 7 plan with the following additions:

a . That, an immediate change for incoming 10» grade students and

for all students currently in the 10U> and life grades be made.

p;

ps -JL !

■

^ rdtf i

School Integration Proposals

Page 2

b. If, the April 7 plan is compared to the current 8-region

organization, it is apparent that all facets of that plan

nay be initiated within the current organization, except

Denby-Kettering. The fact of a violation of region boundaries

as a requirement to re-institute April 7 should not be a major

deterrent to carrying out the plan. Precedent exists currently

in the Post-Cooley, Burroughs-Kettering, and the Vernor-Vandenberg-

Ford combinations for student attendance areas which do not fit

adult voting areas.

c. It is obvious that there is room for debate as to the extent

that the 8-region organization may be abridged. Citizen discontent

has been expressed with the several discontinuous areas noted

in Item b above. The court will be hearing the NAACP case after

the region boards have been elected.

Unfortunately the boundaries for Regions 6, 7 and 8 are such as

to cut the Kettering constellation in two major parts, and also

, to leave the Denby area without an adjacent area from which to

draw black students. If, region boundaries cannot be altered,

and if the high school plan is altered as a consequence, then

integration in the April 7^ concept, cannot be carried out, on

the east side, in any manner equal to that on the west side.

Therefore, exploration of the possibility of court-ordered changes

in t.h« ef"5 ryp boundaries ought tc be explored in order to make the

April 7^ plan feasible.

Advantages:

1. A greater integrated student population than currently exists

or that would exist by the implementation of the April 7^

boundary changes only.

2. A continuum of disfunction between school attendance and

region authority exists between Proposal #1 and #2. This

same disfunction occurs in varying degrees in each proposal.

3. laess busing would be required under this proposal, than Proposal 1.

Therefore, money and student travel time would be required.

Proposal 3 «

Pairing of elementary and junior high schools.

In the effort to maximize the amount of integration, we recommend that

schools be paired in such a manner as in the following examples:

School Integration Proposals

P»«e 3

1. The pattern of alternate grades attending each school be

instituted in the following schools:

Richard-Von Steuben-Burroughs, Goodale-Joy, Earhart-Pelham,

Condon-Wilson, Drew-Brooks-Ruddiman, Emerson-Winship, and

further that additional schools be added, if possible, to

this list.

2. Pairing of the schools which have less than 5# of either

white or black students can move towards the NAACP position.

Thirty-nine elementary schools have less than 5% black students

and 94 schools have less than 5% white students.

Similarly, a bussing program might bring together the following:

Junior Highs

Taft

Beaubien

Arthur-Richard

Foch

Lessenger

Webber

Elementary

All White

White

970

13

464-672

74

943

1

Black

7

1,255

10-23

1,564

86 (bussed, now)

1,385

All Black

Cooke 996 Angell 1,282

Gompers 461 Brady 1,125

Healy 298 Glazer 753

McLean 214 Sanders 669

Proposal 4:

Magnet School

A third alternative would be to close, as regular junior or senior

high schools, those schools with seriously declining enrollments,

and reorganize them as specialized trade schools or as experimental

"open" schools with a city-wide enrollment. Some of these school

plants might be:

Durfee, Longfellow, McMichael, Hutchins, Northeastern, Murray,

Chadsey and Northern.

Some principles of the magnet school concept which should be applied

include the following:

School Integration Proposals

Page k

x. The school program must be so planned that it will receive

recognition as one of real strength and special value to

students, clearly superior in one or more vital respects to

the neighborhood high school*

2* Such schools would utilize innovative and sound patterns

of organization, curriculum, student government, personnel,

housing and other areas of school life*

3* ' The name of the school should be changed, so it is no longer

identified as an old neighborhood school, and it is viewed

as a new school identified with a new and most promising

specialized program*

Jf* Attention should be directed to the lines of transportation, -

to insure that students and parents would consider these among

the best and most desirable*

5* The student and staff membership must be well integrated racially*

6* The school should be advertised as open to suburbanites* There

may Well be some objections; however, the advantages derived would

clearly outweigh the objections* The enrollment of a number of

suburbanites would do wonders for the school's image and reputation*

7* The school would have a free and open transfer policy, crossing

regional and even district lines.

8. These schools could be given some special prestigious label,

such as "the metropolitan schools*"

’ Advantages:

In each case cited, the neighboring schools have capacity to share

or absorb entirely the enrollment of the school to be closed* Each

of these schools has availability to public transportation which

would allow them to function as a magnet school. For instance,

the relationship with Michigan Bell Telephone Company and Northern

High School might be better exploited by the school's role as a

magnet school with a city-wide draw. The existence of such schools

with a free and open transfer policy would act as a pressure relief

for those parents and students now in serious disagreement with

the program of the "comprehensive" high school.

School Integration Proposals

Page 5

Disadvantage s:

1* Jeopardy to principle of decentralization,

2, Under Proposal b integration of students probably will not

immediately result from the magnet school concept. The city-wide

attraction to both white and black parents is a function of

sufficient time to '‘prove" to the community the educational

strength and the merit of the specialized magnet schools,

. ' ’ • ..1Proposal 5:

NAACP Plan.

• ’ ...

In response to the NAACP appeal to the court for a structured student

ratio reflective of the city enrollment as a whole, the Department of

Intergroup Relations recommends the practices below:

1. One approach might be a bussing structure as demonstrated in

Berkeley, California, a cross-bussing of grades with a series

of planned steps as detailed in the many reviews of that plan.

This plan would require considerable logistical preparation,

community preparation and professional staff orientation.

Appropriate descriptions of the Berkeley plan may be found in

the attached articles,

2, Some observations which might be made about such a plan are

as follows:

— schools with up to bO% of either race would not be involved

in the program.

— all schools should involve all of the children in order to

build identification with the program,

• - : ■**

— Cody, Ford, Mumford, Osborn, Finney, Kettering, King and

Hurray high schools have been constructed in the past 25 years

and were built to provide for increased enrollments rather than

.convenience. As each of these schools was built, district

boundaries for schools in the general area were altered and

students changed the direction and distance that they traveled

to attend school.

— the distances some students currently travel to attend Finney

or Southwestern schools is equal to or greater than students

would probably be asked to travel.

School Integration Proposals

Page 6

— Junior high schools have been constructed in order to provide

seats for students that have resulted in considerable diminuti

of the distances students have had to travel, as compared to their

predecessors*

The maximum racial mix in Detroit Public Schools would occur by < * * * £ • *

students in each public school in the racial proportions t^atexist

the svstem as a whole. The current student enrollment as of October, 1970,

Sdicates a racial proportion of 62* black, 38* white. Therefore, students

iSuid be assigned i f a manner that the enrollment In

be 62* black and 38* white. This has been done inEerkeiey, cal;forn .

Description of the Berkeley plan may be found in the attached articles.

Advantages:

1. A completely integrated student population to the degree allowable

based on the total number of black and white students.

Disadvantage s:

Funds

1. The sheer size of Detroit indicates that such a proposal would

necessitate a massive busing program.

SUMMARY

s g s s -

£ £ " s ^ T g i v e s maximum"planned^considerŝ i o ^ for° the* i n t e ^ ^ i o n o f

element^ y SShool students. Reposals 2 and 3 predominantly deal with the

racial rate at the junior and senior high school levels.

For more than a year our school system has been d e e p l y P*anS

for decentralization. The five proposals presentedaisoconstitute a

continuum in terms of difficulties encountered by the 8-region plan as

prescribed by the legislature.

The Division of School-Community Relations urges that any of the above£s?*rsr ssa-ssraa « «M d orientation of students, community and staff so that the prognosis

for success of the adopted plan is maximized.

We would urge that as of January, 1971, regional boards be dir®oJ®dclosely, the possibilities of increasing integration within their

Individual boundaries. The central board should reserve, through the

adoption of guidelines, the authority to mandate movement toward integration

of the entire district.

*

... ' • . _ > • - j

*

%

. . School Integration Proposals

Page 7

A final word of concern is directed specifically to the critical need,

as we see it at this time, to balance satisfactorily both the aims and

implementation of integration goals on the one hand and decentralization

, goals on the other.

&>• : : ;• ■ . . ,f • 5,-V.' ...>.

_ • t; /jSjL...

. ' ̂

Ijlk ... ....

f

ft' 17-p g

November 9> 1970

PPOPOS/L FOR SCHOOL DESEGREGATION

The staff task force of Detroit Public Schools, after considering

various alternative proposals submitted by the Division of School-

Community Relations, offers for consideration the following recom

mendation for increasing the degree of racial desegregation at

various grade levels in the school district. Certain fundamentals

must be taken into account in considering this proposal: (1) the

amount of racial mix of students, and (2) the degree to which

regional boundaries are held inviolate so that parents can vote

and help to determine policies of the schools which their children

attend.

1.

2 .

The School Board should adopt a High School Desegregation

Plan, and change high school attendance boundaries as defined

by School Board action on April 7> 1970, to take effect for

all students entering the affected schools in February, 1971.

Although changes in racial percentages have occurred during

the past year, the relationship of the paired schools in that

plan are still, relatively, the same. That Is, Redford, Cody,

Osborn, Denby, Western and Ford have a significant majority

of white students. Mackenzie, Cooley, Mumford, Pershing,

Kettering and Southwestern have a preponderance of black

students. It should be noted that all boundary changes occur

within the established eight regions, with the exception of

the Denby-Kettering areas.

'"fu\w »

& 4"t-’"■4 ■ >

■ V iw * JW

% m: m

NOTE: This part of the plan will include approximately 800

to 1,000 students in February and'another 3>200 In

September. ! -

As part of a long-range plan to provide further desegregation *

we also propose a reorganization of the schools to include

adjustment of grade level organization. The reasons for edu

cational groupings In the past have varied, but have rarely

included the basic purpose of desegregation. With desegregation

as a basic aim, it is possible to reorganize a number of

schools in pursuit of this objective. This reorganization also

requires redrawing of school attendance areas.

It Is proposed In this movement towards reorganization that we

direct our efforts towards implementation of the following:

, , ^ V ^1. A modification of a h-h—h school concept.

2. Refinement and expansion of a magnet school

approach.

’ '' ĵL

VI

*

I

t

i ^

f f i \

p «

St * ‘

r ;

I Lf1

JI . %

5 r'

•

6 ;■■

y>-:,;

#'

W

% r

;^ '

ic ••, I A

\ ...

i •lip.

r

# # t ?■

Ji .::■

- 2 -

It should be noted that the l»-l|̂l* plan is receiving national

acceptance of its educational validity and in line with this,

previous Board of Education action has resulted in the adoption

of the 4-year high school. Modifications of this plan will,

of course, be necessary to take into account the unique housing

and boundary situations of individual school communities.

V:;' v: *';• ';w

The magnet school plan would close, as regular junior or

senior high schools, those schools with seriously declining

enrollments, and reorganize them as specialized schools or as

experimental nopen!' schools with a city-wide enrollment.

Some of these school plants might be:

Durfee, Longfellow, McMichael, Hutchins,

Northwestern, Murray, Chadsey and Northern

>.fy:

*■; &

Some principles of the magnet school concept which should be

applied include the following:

! ■ ■: t' 6

1. The school program must be so planned that it

will receive recognition as one of real strength

and special value to students, clearly superior

in one or more vital respects to the neighbor

hood high school.

2. Such schools would utilize innovative and sound

patterns of organization, curriculum, student L

government, personnel, housing and other areas

of school life. - * m

3.

■' T̂v .

The name of the school should be changed, so

it is no longer identified as an old neighbor

hood school, and it is viewed as a new school

identified with a new and most promising

specialized program.

Attention should be directed to the lines of. .____ „ J--a kf4. U W vy A i V A -------- ■ ..

transportation, to insure that students andU X a i i o p w i U U U J . W U * -*-***-' ~ "

parents would consider these among the best

i _ _ J 4 — t— "1 a «and most desirable. V . J F

5.

6 .

The student and staff membership must be well

integrated racially.

.. ' ■' ' . f

The school should be advertised as open to

suburbanites.

7. The school would have a free and open transfer

policy, crossing regional and even district

lines.

8. These schools could be given some special

prestigious label, such as Mthe metropolitan

schools.”

NOTE: This part of the plan may well include as many as

25,000 in the portion and the magnet plan could

well involve several thousand more.

SUMMARY

The success of this plan of action is dependent upon clear policy

commitment and in-service training programs to develop the

Instructional, curricular and attitudinal changes. Involvement

of the affected communities In all of the preparatory steps would

also be of crucial importance.

The strength of this proposal Is that a greater degree of racial

desegregation is achieved within the currently established regions.

This reinforces the processes of integration and decentralization.

The high school desegregation component extends the continuing

effort tovrard desegregation as a major goal of the Detroit Public

Schools. The modified middle school component extends that effort

within established regional boundaries, including all grade levels,

and will require in many instances the busing of students.

Although the magnet school encompasses the total district, it

encourages voluntary integration by attracting Interested students

to its specialized programs.

We recommend that as of January, 1971, regional boards be directed

to examine closely, the possibilities of increasing integration

within their boundaries. The central board should reserve, through

the adoption of guidelines, the authority to mandate movement

toward integration of the entire district.