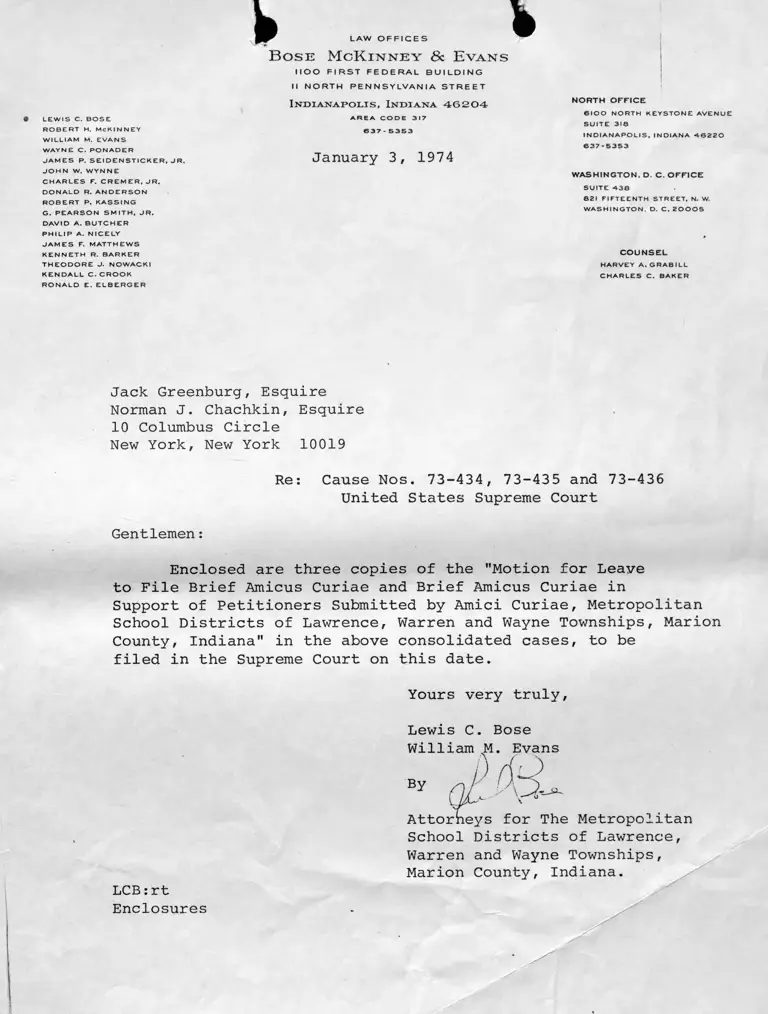

Letter to Greenberg and Chachkin from Bose and Evans RE: Copies of Motion and Brief

Public Court Documents

January 3, 1974

1 page

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Letter to Greenberg and Chachkin from Bose and Evans RE: Copies of Motion and Brief, 1974. 67cadb6f-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4f7988c8-7280-46a0-b767-6bcfe5c3ff87/letter-to-greenberg-and-chachkin-from-bose-and-evans-re-copies-of-motion-and-brief. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

<* L E W I S C. B O S E

R O B E R T H. M c K I N N E Y

W I L L I A M M. E V A N S

W A Y N E C . P O N A D E R

J A M E S P. S E I D E N S T I C K E R , J R .

J O H N W. W Y N N E

C H A R L E S F. C R E M E R , J R .

D O N A L D R. A N D E R S O N

R O B E R T P. K A S S I N G

G. P E A R S O N S M I T H , J R .

D A V I D A . B U T C H E R

P H I L I P A . N I C E L Y

J A M E S F. M A T T H E W S

K E N N E T H R. B A R K E R

T H E O D O R E J. N O W A C K I

K E N D A L L C . C R O O K

R O N A L D E. E L B E R G E R

L A W O F F I C E S

B o s e M c K i n n e y <3c E v a n s

I I O O F I R S T F E D E R A L B U I L D I N G

II N O R T H P E N N S Y L V A N I A S T R E E T

Indianapolis, Indiana 46204

A R E A C O D E 31 7

6 3 7 - 5 3 5 3

January 3, 1974

NORTH OFFICE

6 1 0 0 N O R T H K E Y S T O N E A V E N U E

S U I T E 3 1 S

I N D I A N A P O L I S , I N D I A N A - 4 6 2 2 0

6 3 7 - 5 3 5 3

WASHINGTON, D. C. OFFICE

S U I T E 4 3 6

8 2 1 F I F T E E N T H S T R E E T , N. W.

W A S H I N G T O N . D. C . 2 0 0 0 5

C O U N S E L

H A R V E Y A . G R A B I L L

C H A R L E S C. B A K E R

Jack Greenburg, Esquire

Norman J. Chachkin, Esquire

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Re: Cause Nos. 73-434, 73-435 and 73-436

United States Supreme Court

Gentlemen:

Enclosed are three copies of the "Motion for Leaye

to File Brief Amicus Curiae and Brief Amicus Curiae in

Support of Petitioners Submitted by Amici Curiae, Metropolitan

School Districts of Lawrence, Warren and Wayne Townships, Marion

County, Indiana" in the above consolidated cases, to be

filed in the Supreme Court on this date.

Yours very truly,

Lewis C. Bose

William M. Evans

w at

Attorneys for The Metropolitan

School Districts of Lawrence,

Warren and Wayne Townships,

Marion County, Indiana.

LCB:rt

Enclosures