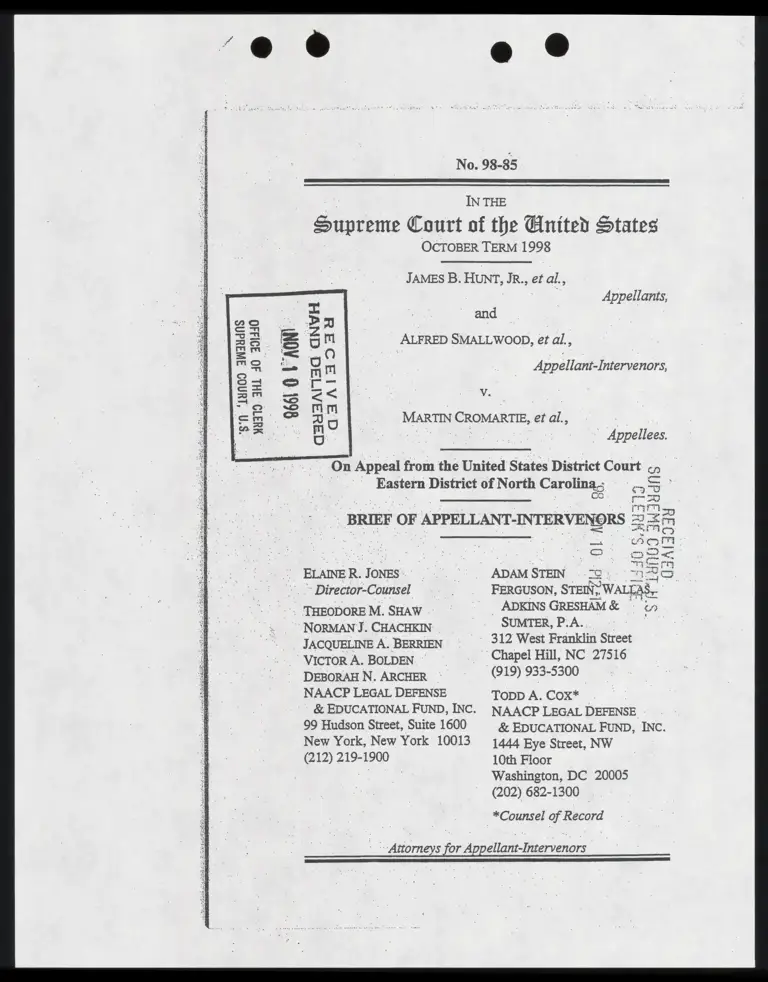

Brief of Appellant-Intervenors with Certificate of Service

Public Court Documents

October 10, 1998

55 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Brief of Appellant-Intervenors with Certificate of Service, 1998. ed2a8319-d90e-f011-9989-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4fd9b575-f686-4420-80f4-5f265eeb08d0/brief-of-appellant-intervenors-with-certificate-of-service. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

No. 98-85

IN THE

4 Court of the Anited States

OCTOBER TERM 1998

JAMES B. HUNT, JR., et al.,

Appellants,

and

B

y

ALFRED SYA IVO0D o1 al.,

Appellant-Intervenors,

ie.

14

n0

9

IN

UA

NS

96

61

0

V

AO

N!

a

m

u

a

A

I

a

a

N

V

H

a

a

A

l

a

o

a

d

Hi

ya

)

3H

L

40

30

1

MARTIN CROMARTIE, et al., gi

8

nN

a * dppeless

“On Appeal from the United States District Court 2% |

j Eastern District of North Caroling; 4AM

go BRIEF OF APPELLANT-INTERVENORS Ege

poi

™y 5,

“c

Fm

: © ELANER. JONES - ADAM STEIN =o 1:

" Director-Counsel |

Lis, WatosciaM. SHAW

“NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

JACQUELINE A. BERRIEN

VICTOR A. BOLDEN. ©

DEBORAH N. ARCHER

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

& EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

FERGUSON, STE WALTAS,

ADKINS GRESHAM & 4 eh

SUMTER, P.A.. :

"- 312 West Franklin Street

Chapel Hill, NC 27516

(919) 933-5300

ToDD A. COX*

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

& EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

1444 Eye Street, NW |

10th Floor

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 682-1300

*Counsel of Record

a Attorneys for Appellant-Intervenors |

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

In a racial gerrymandering case, is an inference drawn

from the challenged district’s shape and racial

demographics, standing alone, sufficient to support

summary judgment for the plaintiffs on the contested

issue of the predominance of racial motives in the

district’s design, when it is directly contradicted by the

affidavits of the legislators who drew the district?

Does a final judgment from a court of competent

jurisdiction, which finds a state’s proposed

congressional redistricting plan does not violate the

constitutional rights of the named plaintiffs and

authorizes the state to proceed with elections under it,

preclude a later constitutional challenge to the same

plan in a separate action brought by those plaintiffs and

their privies?

Is a state congressional district subject to strict scrutiny

under the Equal Protection Clause simply because it is

slightly irregular in shape and contains a higher

concentration of minority voters than its neighbors,

when it is not a majority-minority district, it complies

with all of the race neutral districting criteria the state

purported to be following in designing the plan, and

there is not direct evidence that race was the

predominant factor in its design?

R

l

A

e

i

m

m

S

A

E

B

A

S

E

L

E

i

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDINGS

Actual parties to the proceeding in the United States

District Court were:

(1) James B. Hunt, Jr, in his capacity as Governor

of the State of North Carolina, Dennis Wicker in his official

capacity as Lieutenant Governor of the State of North Carolina,

Harold Brubaker in his official capacity as Speaker of the North

Carolina House of Representatives, Elaine Marshall in her

official capacity as Secretary of the State of North Carolina, and

Larry Leake, S. Katherine Burnette, Faiger Blackwell, Dorothy

Presser and June Youngblood in their capacity as the North

Carolina State Board of Elections, defendants, appellants

herein,

(2) Alfred Smallwood, David Moore, William M.

Hodges, Robert L. Davis, Jr., Jan Valder, Barney Offerman,

Virginia Newell, Charles Lambeth and George Simkins,

defendant-intervenors, appellant-intervenors herein, ;

(3) Martin Cromartie, Thomas Chandler Muse, R.O.

Everett, J.H. Froelich, James Ronald Linville, Susan Hardaway, -

Robert Weaver and Joel K. Bourne, plaintiffs, appellees herein.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Questions Presented ......................

Parties to the Proceedings ..................

Table of Authorities ............... + Sg

Opinions Below .., . Jos ie vivsininivian dain wiv

JURSACHON . » oh esi, 4 sbois nisin aires 3 + 08% 7

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

Statement ofthe Case... .... cova divs wrnns

A. Events leading to Adoption of the

1997 Remedial Plan ...........

B. The 1997 Remedial Plan .......

C. The Legal Challenge to the 1997

Remedial Plan ..... 00h

Summary of Argument ................000n

ARGUMENT -

1 Summary Judgment was Inappropriate

inthisCase ...L..0 0 Jee aus e vin:

S

E

A

ge

d

3

T

r

B

a

h

e

h

F

t

d

So

d

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued)

Page

ARGUMENT (continued)

A. Because this case involves an inquiry

into the intent of the North Carolina

legislature, it should not have been

resolved through summary judgment . . . . . 17

B. Because this case necessarily concerns

issues arising under the Voting Rights

Act, it should not have been resolved

through summary judgment ........... 23

II The District Court Erred in Ruling That Race

Was the Predominant Factor in the Creation

of the Twelfth Congressional District .......... 27

A. The court erred in sanctioning the

Appellees’ argument that race

predominated in the development of

the 1997 Remedial Plan because that plan did

not evidence legislature’s complete

abandonment of the 1992 plan as a

starting point for fashioning the

remedy ..... ee BS anh ha ole 4 27

Vv

TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued)

Page

ARGUMENT (continued)

B. In jurisdictions such as North Carolina,

with a history of prior discrimination

and minority vote dilution, and in which

voting patterns remain racially polarized,

districting must be sufficiently race-

conscious to avoid violating Section 2

of the Voting Rights Act, but that

circumstance does not establish that

race “predominates” so as to trigger

BStrict SOrUbInY? 0... on a 32

III . Even if Race Predominated in its Creation, the

District Court Erred in Never Determining if the

State had a Compelling Justification for Creating a

Nagrowly Tailored District 12... ci cei e ane es 40

Conclusion” 8... .... 0A Con LN SH NE A a 42

vi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Page

Abrams v. Johnson,

SAMUS. F4Q997) ......hciiiactvnnanrans 36

Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc.

ATTIUS. 2421088) . 0. sein delesianis avs vie 18

Bronze Shields, Inc. v. New Jersey Department

of Civil Service, 667 F.2d 1074 (3d Cir.

1981), cert. denied, 458 U.S. 1152 (1982) ites 18

Burns v. Richardson,

2384S. 739086). . - «elvis sine vais So nains 29

Bush v. Vera,

517 U.S. 952 (1996) ....... Dh passim

City of Rome v. United States,

450 F. Supp. 378 (D.D.C. 1978) ............. 26

Clark v. Calhoun County,

88 F. 3d. 1393 (5th Cir. 1996) ..............- 38

County Council v. United States,

555 F. Supp.694 (D.D.C. 1983) ............-: 26

vii

CASES (continued)

DeWitt v. Wilson,

856 F. Supp. 1409 (E.D. Cal. 1994),

afd, 3150.8. 117001993)..." ..... 5,

Gingles v. Edmisten,

590 F. Supp. 345 (E.D.N.C. 1984),

aff'd in part and rev'd in part, sub. nom.,

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) . .

Growe v. Emison,

S07 US 251093).

Jeffers v. Clinton,

839 F. Supp. 612 (E.D. Ark. 1993)

Johnson v. DeSoto County Board of Commissioners,

863 F. Supp. 1376 (M.D. Fla. 1994)

Johnson v. Miller,

864 F. Supp. 1354 (S.D. Ga. 1994),

ard, 515U8.900(1995). ........... is

King v. State Board of Elections,

Use 1188.0 2771998)

Lawyer v. Department of Justice,

Lipsett v. University of Puerto Rico,

8364 F.24 881 (1st Cir. 1988) ........ cc... 0

ea eo oo 9 ° eo a eo a o

SA US S67(1997) vo. il... i

e

s

m

m

R

I

e

S

Ln

a

T

y

er

Eo

S

e

E

C

a

r

hn

A

S

A

R

CASES (continued)

Mallory v. Eyrich,

707 F. Supp. 947 (S.D. Ohio 1994) .....

McDaniel v. Sanchez,

ABIUE 130A) 0 ih ale Saas

McGhee v. Granville County,

860 F.2d 110 (4th Cir. 1988) ..........

Miller v. Johnson,

$15 U.8.900(1995) ......... hl

Poller v. Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc.,

S688 464 (1962) ....... iis

Pullman-Standard v. Swint,

BEUSIIBOBY oid ll ives

Ross v. Communications Satellite Corp.,

759 F.2d 355 (4th Cir. 1985) . ........ ;

Scott v. United States,

920 F. Supp. 1248 (M.D. Fla. 1996),

aff'd sub. nom., Lawyer v. Department

of Justice, 521 U.S. 567 (1997) ..... te

Shaw v. Hunt,

S17U.S 300006). has iv ies

a

ix

CASES (continued)

Page

Shaw v. Hunt,

No. 92-202-CIV-5-BR (E.D.N.C.

September 12,1997) ....... Che Lh 9

Shaw v. Hunt,

861 F. Supp. 408 (E.D.N.C. 1994),

revd, 5170.8. 8091996) ............. a 1

Shaw v. Reno,

S300.13.8.630 (1993) &.. .. vnus ni TH passim

Shaw v. Reno,

808 F. Supp. 461 (ED.N.C.1992) ............. 1

Smith v. Beasley,

946 F. Supp. 1174 (D.S.C. 1996) .......... 21.25

Smith v. University of North Carolina,

632F.24316 (4th Cir 1980). ............... 18

Stepanischen v. Merchants Despatch Transportation

Corp., 722 F.2d 922 (1st Cir. 1983) .......... 18

Tallahassee Branch of NAACP v. Leon County,

827F2d1436 (1th Cir 1987) +... . isis hus 29

Thornburg v. Gingles,

4730S. 301986)... h.. ie 23, 37

At

E

N

A

T

C

T

Sd

X

CASES (continued)

Page

. United States v. Hayes,

SISUS.737(1995) ............ 5. 33

Upham v. Seamon,

456 1.8. B7 (1082) un... oli. ir anid ne ue 30

Vera v. Richards,

861 F. Supp. 1304 (S.D. Tex. 1994),

aff'd sub. nom., Bushv. Vera,

51700.8. 9521998) uit. «iin a passim

Voinovich v. Quilter,

5070.8. 148. (1093) ii uu i citi mine ov aug 29

White v. Weiser,

4120.8. 783 (3073) 0.0. . . «vie wine an aii, ws 22,30

Wilson v. Eu,

1 Cal. 4th 707, 823 P.2d 545,

4Ca Rotr.24379(1992) .... 00. ova ivi 37

Wise v. Lipscomb,

A37 U.S. 5351078) vk ooo iv cis diaiaie sin inin y nis 29

STATUTES & RULES

NOS C S153 By. Er Be 2

A SIC. SB 1073. a. hy nis ar Ne ia 23, 32

n

m

STATUTES & RULES (continued)

Page

RUS.C. 8197300. 6 i i ti ES

1997 N.C. Sess. Laws, Ch. 11 be 4° fui

Fed RCOIV.R. S58... otun cP oh on a 52

OTHER AUTHORITIES

10B Charles A. Wright, Arthur R. Miller, &

Mary K. Kane, Federal Practice

and Procedure (1998ed.) .................... 19

BRIEF OF APPELLANT-INTERVENORS

Alfred Smallwood, David Moore, William M. Hodges,

Robert L. Davis, Jr., Jan Valder, Barney Offerman, Virginia

Newell, Charles Lambeth and George Simkins (“Smallwood

Appellants”), white and African-American citizens and

registered voters residing in either North Carolina’s First or

Twelfth Congressional District, were granted leave by this

Court to intervene as Appellants from the final judgment of the

three-judge United States District Court for the Eastern District

of North Carolina, entered April 6, 1998, in Cromartie v. Hunt.

The Cromartie three-judge court held that the Twelfth

Congressional District of North Carolina’s 1997 congressional

reapportionment plan, 1997 N.C. Sess. Laws., Ch. 11 (“1997

Remedial Plan”), violates the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution.

OPINIONS BELOW

The April 14, 1998 opinion of the three-judge district

court appears in the Appendix to the Jurisdictional Statement on

Behalf of the State of North Carolina (“NC. J.S. App.”) at 1a.

The district court’s order and permanent injunction, entered on

April 3, 1998, and the district court’s final judgment, entered

April 6, 1998, are unreported and appear at NC. J.S. App. at

45a and NC. J.S. App. at 49a, respectively. Previous decisions

of earlier phases of related litigation are reported at Shaw v.

Hunt, 517 U.S. 899 (1996); Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630

(1993); Shaw v. Hunt, 861 F. Supp. 408 (E.D.N.C. 1994); and

Shaw v. Reno, 808 F. Supp. 461 (E.D.N.C. 1992).

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the court below was entered on April

6, 1998. The State of North Carolina filed an amended notice

of appeal to this Court on April 8, 1998. This Court noted

probable jurisdiction on September 29, 1998. The jurisdiction

A

h

E

X

A

S

2

a

of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1253.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND

STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This appeal involves the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment and Rule 56 of the Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure, reproduced at NC. J.S. App. at 169a and 171a,

respectively.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Events leading to Adoption of the 1997 Remedial

Plan

This case is a challenge to the 1997 Remedial Plan,

which is the third congressional redistricting plan enacted by the

North Carolina General Assembly since the 1990 Census.’

On remand, the North Carolina General Assembly

~ convened to develop a redistricting plan to remedy the

constitutional infirmities found by this Court. While the State

has identified many factors, especially political concerns, that

were considered by the General Assembly, the legislature also

had before it an extensive record concerning the historical

exclusion of black voters, continuing racial appeals in North

Carolina election contests, the socio-economic disparities

affecting African-American voters’ opportunities to participate

in the political process, the lack of success of African-American

*

®)

Ril

a

a

¥

Is

4

xX

i

i

’

N

af

efi

Ki

ik

if

SF

FE

ahi

Wi py

ou

Fa El.

bi

ba 4

Sil

af,

XE

af

wp

Ff.

i:

fit a

hy!

Fi 43

3"

wl

bl

gr

hi

if

3

py

i

"This Court’s ruling in Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899 (1996),

concerned the 1992 Congressional Redistricting Plan (“1992 Plan”) enacted

by the North Carolina legislature following the 1990 Census. In Shaw, this

Court held that the 1992 Plan was unconstitutional because the location and

configuration of District 12 violated the equal protection rights of some of

the plaintiffs in the action. Shaw, 517 U.S. at 902. A map of the 1992 Plan

is reproduced at NC. J.S. App. at 61a.

3

candidates, and the continuing prevalence of racially polarized

voting. See, e.g., Affidavit of Gary O. Bartlett, Section 5

Submission, Attachment 97C-28F-3B, North Carolina

Congressional Redistricting Public Hearing Transcript, February

26, 1997 at 19-22; Id., Ex. 6 (Statement of Anita Hodgkiss) at

2-7,1d., Ex. 6, Tab 2 (Expert Report of Dr. Richard Engstrom)

(“Engstrom Report”).

Indeed, the General Assembly was aware that for nine

decades, from 1901 until 1992, no African-American candidate

had been elected to Congress in North Carolina, even when they

enjoyed the overwhelming support of African-American voters.

Moreover, African-American voters were disenfranchised as a

result of conscious, deliberate and calculated state laws that

both denied African-American voters access to the ballot box

and effectively diluted their votes. See Gingles v. Edmisten,

590 F. Supp. 345, 359 (E.D.N.C. 1984), aff'd in part and rev'd

in part sub nom. Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986).

The State utilized measures such as poll taxes, literacy tests,

anti-single shot voting laws, and at-large and multi-member

election districts to exclude African-Americans from the

political process. Id. See also Affidavit of Gary O. Bartlett,

Section 5 Submission, Attachment 97C-28F-3B, North Carolina

Congressional Redistricting Public Hearing Transcript, February

26, 1997 at 19-22; Id., Ex. 6, Tab 17 (Expert Report of Dr. J.

Morgan Kousser) (“Kousser Report”); Affidavit of Dr. David

R. Goldfield (“Goldfield Report”), filed as Tab 3 to Defendants’

Brief in Opposition to Plaintiffs’ Motion for Summary Judgment

and in Support of Their Cross-Motion for Summary Judgment.-

Specifically, with regard to congressional districting, in its 1970

and 1980 reapportionment plans, the General Assembly

intentionally fragmented the African-American vote in the

4

northeastern portion of the state to make sure African-American

voters could not garner enough support to elect their preferred

candidate to Congress. Kousser Report at 34-46. Also, racial

appeals in campaigns were used by white candidates to dissuade

white voters from supporting African-American candidates.

Affidavit of Gary O. Bartlett, Section 5 Submission, Attachment

97C-28F-3B, North Carolina Congressional Redistricting Public

Hearing Transcript, February 26, 1997, Ex. 6, Tab 17 (Expert

Report of Dr. Harry L. Watson).

To this day, the ability of African-American voters to

participate in congressional elections has continued to be

hindered by the persistent effects of past official discrimination.

For example, the legacy of literacy tests, in use until the mid-

1970s, and poll taxes continues to be reflected in the fact that

African-American voters are registered to vote in lower

percentages than white voters.> African-American voters asa

whole are less well-educated, lower-paid, more likely to be in

poverty, and have less access to basic instruments of political

participation such as telephones, cars, and money than do their

white counterparts, which adversely affects their ability to

participate effectively in the political process. Affidavit of Gary

O. Bartlett, Section 5 Submission, Attachment 97C-28F-3B,

North Carolina Congressional Redistricting Public Hearing

2In 1960, statewide only 39.1 percent of the African-American

voting- age population was registered to vote, compared to 92.1 percent of

the white voting-age population. Gingles v. Edmisten, 590 F. Supp. at 360.

In the majority-black counties, all located in eastern North Carolina, less

than 20 percent of the African-American population was registered to vote

in 1960. Goldfield Report at 5. By 1980, statewide 51.3 percent of age-

qualified blacks and 70.1 percent of whites were registered. Gingles, 590

. F. Supp. at 360. In 1993, 61.3 percent of blacks and 72.5 percent of whites

who were eligible to vote were registered. Stipulation No. 63.

5

Transcript, February 26, 1997, Ex. 6, Tab 17 (Shaw v. Hunt,

Defendant-Intervenor Stipulations) (“Stipulations™) Nos. 1-58,

64-67).

Elections in North Carolina in the 1990’s are still

marked by direct appeals to race designed to discourage white

voters from voting for African-American candidates. Affidavit

of Gary O. Bartlett, Section 5 Submission, Attachment 97C-

28F-3B, North Carolina Congressional Redistricting Public

Hearing Transcript, February 26, 1997, Ex. 6, Tab 17 (Expert

Report of Dr. Alex Willingham) at 17-26. In fact, in 1990,

large numbers of qualified African-American voters were

anonymously sent post cards which misrepresented state law

and threatened them with criminal prosecution if they tried to

vote after having recently moved. Affidavit of Gary O. Bartlett,

Section 5 Submission, Attachment 97C-28F-3B, North Carolina

Congressional Redistricting Public Hearing Transcript, February

26, 1997, Ex. 6, Tab 16 (Shaw v. Hunt Defendant-Intervenor

Ex. 522-531).

In North Carolina elections, white voters tend not to

support the candidates of choice of African-American voters.

In this century, no African-American candidate other than Ralph

Campbell, State Auditor, has ever won a statewide election

contest for a non-judicial office. No single-member majority-

white state legislative district has ever elected an African-

American candidate to the state legislature. Stipulation Nos.

13, 18. A study of 50 recent elections in which voters have

been presented with a choice between African-American and

white candidates, including congressional elections, statewide

elections and state legislative elections, found that 49 of the 50

were characterized by racially polarized voting. See Engstrom

Report. In every statewide election since 1988 where voters

6

were presented with a biracial field of candidates, voting

patterns indicated significant white-bloc voting. Id. In all

except two low-profile contests, racially polarized voting was

sufficient to defeat the candidate chosen by African-American

voters. Id.

A pattern of racially polarized voting continued in the

1996 U.S. Senate campaign between Harvey Gantt and Jesse

Helms. The regression and homogeneous precinct analyses

show that statewide, Gantt received between 97.9 percent and

100 percent of the African-American vote, but only 35.7

percent to 38.1 percent of the non-African-American vote. See

Affidavit of Gary O. Bartlett, Section 5 Submission at

Attachments 97C-28F-3B and 97C-28F-D(3), p.6.

B. ‘The 1997 Remedial Plan

The first post-1990 Census North Carolina

congressional reapportionment plan, enacted in 1991, contained

one majority-black district that was 55.69 percent black in total

population and 52.18 percent black in voting age population.’

The second post-1990 Census reapportionment plan, enacted in

1992, contained two majority-black districts (the First and

Twelfth Congressional Districts), but the Twelfth Congressional

District was held unconstitutional in Shaw v. Hunt.

The North Carolina General Assembly enacted the 1997

Remedial Plan to remedy the constitutional violation found in

Shaw v. Hunt. District 12 in the 1997 Remedial Plan is no

longer a majority-black district. In fact, by every measure, the

African-American population in District 12 is approximately ten

>This Court discussed the history of the first plan in Shaw v. Reno,

509 U.S. 630 (1993) and Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899 (1996).

7

percentage points lower than it was in the 1992 Plan:

Population 1992 Dist. 12 1997 Dist. 12

Total Black 56.63% 46.67%

Total White 41.80% | 51.59%

Voting Age 53.34% 43.36%

Black

Voting Age 45.21% 55.05%

White

Jt. App. at 111 - 115.

In 1997, the General Assembly had two primary

redistricting goals. The first was to remedy constitutional

defects found by this Court in the 1992 Plan, including the

predominance of racial considerations underlying the shape and

location of District 12. NC. J.S. App. at 63a. The General

Assembly accomplished this goal by utilizing a variety of

different redistricting techniques (including several that were

not used in 1992), id.,

1.

including:

Avoiding any division of precincts and

of counties to the extent possible;

Avoiding use of narrow corridors to

connect concentrations of minority

voters;

Striving for geographical compactness

without use of artificial devices such as

double cross-overs or point contiguity;

P

a

A

A

A

S

le

A

a

S

A

rt

F

n

ir

es

4. Pursuing functional compactness by

grouping together citizens with similar

interests and needs; and

5. Seeking to create districts that provide

easy communication among voters and

their representatives.

The second primary goal was to preserve the even (six

Republican and six Democratic members) partisan balance in

North Carolina’s then-existing congressional delegation, which

reflected the existing balance between Democrats and

Republicans in the State. Id. at 64a. In addition, with the State

House of Representatives controlled by Republicans and the

State Senate controlled by Democrats, preserving the same

partisan balance in the congressional delegation was essential to

ensure that the General Assembly would be able to agree on a

remedial plan. Preserving the political status quo in the

congressional delegation was necessary to avoid dissension

from either party, see id., and, therefore, an entirely new

configuration would not have been politically acceptable.

However, the General Assembly felt, as a matter of policy, that

the legislature, rather than the Shaw district court, had a

constitutional duty to devise a new remedial plan, conducting

the necessary balancing of the various interests necessary in

redistricting. See id.

During the 1997 redistricting process, the General

Assembly considered, but ultimately rejected, proposed plans

that would have created a second majority-minority district in

the area east of Charlotte toward Cumberland and Robeson

Counties. Several groups and individuals, including the North

0

Carolina Association of Black Lawyers and State

Representative Mickey Michaux, objected to the 1997 Remedial

Plan because, in their view, it diluted the voting strength of

African-Americans in certain areas of the state and “deliberately i fa

separates large politically cohesive African-American PRE an

communities.” See Shaw v. Hunt, No. 92-202-CIV-5, AR ae

Memorandum in Support of Motion to Intervene (E.D.N.C.

filed April 15, 1997). The plan favored by these groups was

designed to avoid dilution; it also would have combined

African-American voters in Charlotte with voters, including

African-American and Native American voters, in rural areas

southeast of Charlotte. The General Assembly concluded that

such a district would have combined urban and rural voters with

disparate and divergent economic, social and cultural interests

and needs. NC. J.S. App. at 66a. Also, the proposed district

lacked a natural means of communication and access among its

residents. In addition, that district would have thwarted the

goal of maintaining partisan balance in the State’s congressional

delegation. Jd. Although this plan was not enacted, the State

has recognized the need to preserve an equal opportunity for

African-American voters to elect their candidates of choice in

District 12. See NC. J.S. App. at 66a.

The General Assembly enacted the 1997 Remedial Plan

on March 31, 1997 and submitted it to the three-judge court in

Shaw v. Hunt, No. 92-202-CIV-5-BR (E.D.N.C.) the following

day. The State also submitted the plan for preclearance by the

United States Department of Justice pursuant to Section 5 of

the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973c. On June 9, 1997,

the Department of Justice precleared the plan. See NC. J.S.

App. at 162a (Shaw v. Hunt, No. 92-202-CIV-5-BR,

Memorandum Opinion (E.D.N.C. September 12, 1997)).

10

On September 12,1997, the three-judge district court in

Shaw v. Hunt unanimously approved the 1997 Remedial Plan as

“a constitutionally adequate remedy for the specific violation

found by the Supreme Court in [Shaw v. Hunt].” NC. J.S. App.

at 167a. A map of the 1997 Remedial Plan is reproduced at

NC. J.S. App. at 59a.

C. The Legal Challenge to the 1997 Remedial Plan

On July 3, 1996, following the decision of this Court in

Shaw v. Hunt, three residents of Tarboro, North Carolina,

Appellees herein, filed the complaint in this action (Cromartie

v. Hunt), challenging District 1 in North Carolina’s 1992 Plan

on the ground that it violated their equal protection rights

because race predominated in the drawing of the district. A stay

was entered pending the resolution of the remand proceedings

in Shaw v. Hunt. On July 9, 1996 the same Tarboro residents

joined the original plaintiffs in Shaw in filing an Amended

Complaint in Shaw, raising a similar challenge to and asserting

the same claims against the First Congressional District as they

raised in Cromartie v. Hunt. On July 11, 1996, the members of

the Smallwood Appellant group (three voters from the First

District and six voters from the Twelfth District) sought to

intervene in the Cromartie suit as defendants.

The Shaw case was dismissed by the three-judge court

on September 12, 1997, and the Cromartie three-judge court

lifted its stay of proceedings on October 17, 1997. On the same

day, two of the three original plaintiffs, along with four

residents of District 12, filed an amended complaint in the

“The Smallwood Appellants participated fully as intervenors in

Shaw v. Hunt in the trial court and in this Court, including in the remedial

proceedings which resulted in the approval of the 1997 Remedy Plan.

11

Cromartie action, challenging the 1997 Remedial Plan as a

violation of the Equal Protection Clause and still seeking a

declaration that District 1 in the 1992 Plan is unconstitutional.’

Within the time allowed for answering that amended complaint,

the Smallwood Appellants filed a renewed motion to intervene

as defendants.

On March 31, 1998, the court below heard arguments

on cross-motions for summary judgment and on the Cromartie

plaintiffs’ request for preliminary injunction. At the time of this

hearing, the district court had not ruled on the motions to

intervene of the Smallwood Appellants which had then been

pending for over twenty months and four months, respectively.

The court issued its permanent injunction and granted summary

judgment without ruling on these unopposed motions or holding

a hearing on intervention. In fact, the district court refused to

allow counsel for the Smallwood Appellants an opportunity to

bring the motion to intervene before it and expressly denied -

counsel for the Smallwood Appellants an opportunity to speak

at the hearing.

In their summary igen: papers and at the hearing.

Appellees contended that the 1997 Remedial Plan should be

declared unconstitutional because it is the “fruit of the

poisonous tree” of the redistricting plan held to be

unconstitutional in Shaw v. Hunt. See, e.g., Plaintiffs’ Brief in

Support of Motion for Preliminary Injunction at 4-5.

Analogizing the 1997 redistricting process to a criminal trial in

which evidence discovered as a result of information gained by

While Appellees Cromartie and Muse were also plaintiffs in Shaw

v. Hunt, they chose not to present their claims that the 1997 Remedial Plan

was unconstitutional to the Shaw three-judge court.

Mi i a ER SR a es

12

an illegal search is admitted, Appellees argued that any remedial

plan drawn by the legislature must be held unconstitutional

unless the legislature completely discards the invalidated plan

and develops its new plan without reference to even the lawful

aspects of the prior plan. Id.

On April 3, 1998, a three-judge United States District

Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina issued an order

granting summary judgment to plaintiffs, declaring North

Carolina’s Twelfth Congressional District unconstitutional,

permanently enjoining elections under the 1997 Remedial Plan,

and ordering the State of North Carolina to submit a schedule

for the General Assembly to adopt a new redistricting plan and

to hold elections under that plan. NC. J.S. App. at 45a. The

district court issued its judgment on April 6, 1998. NC. J.S.

App. at 49a. Neither the order nor the judgment was

accompanied by a memorandum opinion from the court.

Although the court had not yet released an opinion, the

State moved for a stay of the injunction pending appeal. The

district court denied this motion. ‘The State then filed an

application with this Court for a stay pending appeal, and the

Smallwood Appellants filed an amicus curiae memorandum in

this Court in support of the application. This Court denied the

request for a stay on April 13, 1998, with Justices Stevens,

Ginsburg, and Breyer dissenting.

On April 14, 1998, the district court issued its opinion

explaining its April 3, 1998 order. The court accepted the

uncontested affidavit testimony of Senator Roy A. Cooper, ITI

that the legislature “aimed to identify a plan which would cure

the constitutional defects and receive the support of a majority

of the members of the General Assembly.” NC. J.S. App. at 5a.

The court also accepted the uncontroverted affidavit testimony

13

of Senator Cooper and Gary O. Bartlett, Executive Secretary-

Director, State Board of Elections, that “[i]n forming a

workable plan, the committees were guided by two avowed

goals: (1) curing the constitutional defects of the 1992 plan by

assuring that race was not the predominant factor in the new

plan, and (2) drawing the plan to maintain the existing partisan

balance in the State’s congressional delegation.” Jd,

The court below found that the 1997 Remedial Plan met

the goal of maintaining the existing partisan balances by

“avoid[ing] placing two incumbents in the same district” and

“preserv[ing] the partisan core of the existing districts to the

extent consistent with the goal of curing the defects in the old

plan.” Id. at 5a-6a. Further, the court received no evidence

that directly contradicted the testimony introduced by the State

to the effect that the legislature sought, in creating the 1997

Remedial Plan, to cure the constitutional defects found by this

Court by ensuring that race did not predominate in its creation

while minimizing partisan and political disruption. See id. at

63a-64a. Nevertheless, the court below found that race was the

predominant factor in the creation of the 1997 Remedial Plan

based upon its own assessment of (a) District 12°s racial

demographics and shape, (b) the racial characteristics of a

limited number of precincts that were included in or excluded

from the district, and (c) mathematical measures of District 12’s

relative compactness. Id. at 6a-11a.

While the court asserted that “[a] comparison of the

1992 District 12 and the present District is of limited value

here,” id. at 19a, it concluded that District 12 in the 1997

Remedial Plan is as “unusually shaped” as was District 12 in the

1992 Plan. Id. Focusing exclusively on demographic data and

the district’s configuration, the court held that “the General

14

Assembly, in redistricting, used criteria with respect to District

12 that are facially race driven.” Id. at 21a. Finally, despite

extensive conflicting factual evidence, the court below

concluded that “[t]he legislature disregarded traditional

districting criteria such as contiguity, geographical integrity,

community of interest, and compactness in drawing District 12

in North Carolina’s 1997 plan.” Id. at 21a-22a.

The court never proceeded to assess whether District 12

was narrowly tailored to satisfy a compelling justification, even

though such inquiry is necessary upon a finding that strict

scrutiny should apply to the redistricting plan.® Instead, the

court concluded that the predominance of race in the creation

of the district alone proved fatal to the district: “the General

Assembly utilized race as the predominant factor in drawing the

District, thus violating the rights to equal protection guaranteed

in the Constitution to the citizens of District 12.” Id. at 22a

(emphasis added). Consequently, the court granted Appellees

summary judgment as to District 12.

On May 26, 1998, with their two prior unopposed

intervention motions still pending, the Smallwood Appellants

Therefore, the court never considered or discussed whether the

creation of District 12 could be justified by the State's compelling interest

in remedying the current effects of North Carolina’s long history of political

exclusion and in avoiding dilution of minority voting strength. The court

ignored evidence presented by the State that its “primary goals [of remedying

the constitutional defects found in the 1992 Plan and preserving partisan

balances in the congressional delegation] were accomplished while still

providing minority voters a fair opportunity to elect representatives of their

choice in at least two districts (Districts 1 and 12),” NC. J.S. App. at 64a,

and that “[d]istrict 12 in the State’s plan also provides the candidate of

choice of Affican-American citizens a fair opportunity to win election.” Id.

at 66a.

15

filed a third motion to intervene as defendants in the case. On

June 20, 1998, after the deadline for filing a timely notice of

appeal of the district court’s April 3, 1998 order and April 6,

1998 judgment, the district court ruled that the Smallwood

Appellants were entitled to intervene as of right in this action.

As the delay in granting the motions to intervene prevented

them from fully participating as parties in the district court and

prevented them from being able to exercise their right to appeal,

the Smallwood Appellants filed in this Court on October 2,

1998 a motion to intervene as Appellants in this case. This

Court granted the motion on October 19, 1998.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

In holding that District 12 of the 1997 North Carolina

Congressional Redistricting Plan (“1997 Remedial Plan”) is

unconstitutional, the court below erred in several critical

respects. First, the court erred in resolving this case in favor of

Appellees on their motion for summary judgment. The

jurisprudence developed by this Court after Shaw v. Reno

dictates that, in evaluating whether a redistricting plan violates

the strictures of the Fourteenth Amendment, a court must

engage in a searching evaluation into the intent of the legislature

in creating the plan. This inquiry is fact-intensive and, as such,

is particularly inappropriate for resolution through summary

judgment. In this case, the State of North Carolina introduced

substantial documentary and testimonial (affidavit) evidence to

rebut the Appellees’ allegation that race predominated in the

legislative redistricting process. Without hearing any live

witnesses or explicitly resolving the conflicts over material facts

created by the parties’ submissions, the court below granted

summary judgment to the Appellees, thus committing reversible

error.

3

16

Second, the court below erred in holding that race was

the predominant factor in the creation of the Twelfth

Congressional District. Appellees argued below that the 1997

Remedial Plan must be declared unconstitutional because it was

the “fruit of the poisonous tree” (the plan invalidated by Shaw

v. Hunt). In essence, Appellees assert that a State remedying a

Shaw violation is required to do significantly more than correct

the constitutional defect found in a challenged district.

According to Appellees, the State must abandon every feature

of the challenged plan and construct a new plan without regard

to traditional districting concerns such as the partisan political

makeup of the State’s congressional delegation, incumbent

protection, and avoiding unnecessary disruption of communities

of interest. Appellees’ theory is fundamentally at odds with this

Court’s precedents, finding no support in Shaw or its progeny

or in the case law defining how courts evaluate remedial

redistricting plans.

The lower court in effect endorsed this theory,

according no deference to the State’s policy choices in the

redistricting process. This also was error. To the extent that

the 1997 Remedial Plan did not violate any federal or state

constitutional or statutory requirements, the district court was

bound to approve the legislature’s decisions.

The court further erred in holding the 1997 Remedial

Plan unconstitutional based solely on its finding that race was

one factor among many considered by the legislature in

redistricting. In so ruling, the court failed to give any weight to

the State’s obligation to avoid minority vote dilution in

redistricting, which necessarily meant that the legislature would

have to be conscious of race in shaping the plan. This ruling is

inconsistent with the Court’s decisions in Shaw and its progeny

17

that require plaintiffs to show that race predominated in the

redistricting process and subordinated traditional redistricting

principles. Thus, the court’s determination that the mere

awareness of race in the redistricting process rendered the 1997

Remedial Plan unconstitutional is erroneous and must be

reversed.

Third, even if the district court had correctly found that

race was the predominant factor in the creation of the Twelfth

District, it erred by not engaging in the required strict scrutiny

analysis to determine if the State had a compelling justification

and narrowly tailored the district to achieve that purpose

ARGUMENT

L Summary Judgment was Inappropriate in this Case

A. Because this case involves an inquiry into the

intent of the North Carolina legislature, it

should not have been resolved through

summary Judgment

Under this Court’s decisions, the “analytically distinct”

claim recognized in Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993) requires

a particularly fact-intensive inquiry and is therefore ill-suited to.

determination by summary judgment. Many factors influence

the redistricting process, but only the predominance of one

factor -- race -- will trigger strict scrutiny. See Miller v.

Johnson, 515 U.S. 900, 913 (1995). Accordingly, a “searching

inquiry is necessary before strict scrutiny can be found

applicable.” Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952, 958 (1996).

In particular, resolution of this case will involve an

inquiry into the intent of the North Carolina legislature through

an examination of the motivation of legislators and an inquiry

18

into the justifications for creating the challenged districting plan.

The ultimate conclusion about the predominance or non-

predominance of race in the districting process is, as in other

cases of intentional discrimination, purely factual. Pullman-

Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273, 289 ( 1982). But because the

crucial facts at issue involve intent, they are rarely appropriate

for determination on summary judgment. See Poller v.

Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc., 368 U.S. 464, 473 (1962)

("We believe that summary procedures should be used sparingly

in complex antitrust litigation where motivation and intent play

leading roles, the proof is largely in the hands of alleged

conspirators, and hostile witnesses thicken the plot”).’

The lower federal courts have found summary judgment

procedures particularly inappropriate in cases where intent is a

critical issue and have made sparing use of the remedy. E.g.,

~ Lipsett v. University of Puerto Rico, 864 F.2d 881, 895 (1st

Cir. 1988) (citing Poller). See Stepanischen v. Merchants

Despatch Transportation Corp., 722 F.2d 922, 928 (1st Cir.

1983); Bronze Shields, Inc. v. New Jersey Department of Civil

Service, 667 F.2d 1074, 1087 (3d Cir. 1981), cert. denied, 458

U.S. 1152 (1982). See also Smith v. University of North

Carolina, 632 F.2d 316, 338 (4th Cir. 1980) (lower court did

not err in denying motion for summary judgment where genuine

issue of material fact existed regarding the reasons underlying

~ "Tobe sure, such cases may still be resolved on summary judgment

where the party opposing summary disposition fails to “offer[] any concrete

evidence from which a [factfinder] could return a [judgment] in his favor.”

Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 256 (1986) (distinguishing

Poller). As we discuss below, however, that was not at all the situation in

the instant matter. The State of North Carolina introduced substantial

evidence that would support a judgment in its favor and was certainly

sufficient to prevent entry of summary judgment for Appellees.

19

the defendant’s decision not to appoint or promote the plaintiff).

Courts have noted that when the disputed issues concern intent

or motivation, judgments about the credibility of witnesses by

the finder of fact are of special importance and utility. See, e.g.,

Ross v. Communications Satellite Corp., 759 F.2d 355, 364

(4th Cir. 1985). Consequently, the need for a court to engage

in the difficult process of assessing the motivation, state of

mind, and credibility of a decision maker is, by itself, a sufficient

basis for denying summary judgment. See 10B Charles A.

Wright, Arthur R. Miller & Mary Kay Kane, Federal Practice

and Procedure § 2730 (1998 ed.).

Attempting to determine the role that race played in the

redistricting process is a necessarily fact-intensive inquiry,

requiring a court to engage in an exhaustive review of the

legislative process. See Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. at 959 (in

“mixed motive” cases, “careful review” is necessary to

determine application of strict scrutiny to electoral districts).

Resolving the difficult question of legislative intent requires a

review of direct evidence, such as the statements and testimony

of legislators, as well as circumstantial evidence, such as district

shape and demographics.

These principles are reflected in the post-Shaw

jurisprudence. In every case where a court has struck down a

district pursuant to Shaw, it has relied on evidence, gained after

a thorough review of the redistricting process, that race was the

predominant factor in districting. For example, in Johnson v.

Miller, 864 F. Supp. 1354 (S.D. Ga. 1994), aff'd, 515 U.S. 900

(1995), the district court determined that race was the

legislature’s dominant consideration in districting only after

engaging in a detailed review of Georgia’s submissions to the

Department of Justice in the preclearance process under Section

20

5 of the Voting Rights Act. Recognizing that legislative

redistricting is the end result of balancing many factors, 864 F.

Supp. at 1363, the court conducted an exhaustive review of

committee meetings and debates, id. at 1363-68, competing

proposals considered by the legislature, id. at 1363, the extent

and type of computer assistance utilized during the redistricting

process, id. at 1363 n.2, advocacy positions adopted by

individual legislators, id. at 1363, Section 5 submission

materials, id. at 1376, and legislative reaction to the denial of

preclearance, id. at 1363-66. The court reviewed documentary

evidence on each of these subjects and also heard direct

testimony from those involved with the legislative process in

order to put that evidence in its proper context.

The district court in Vera v. Richards, 861 F. Supp.

1304 (S.D. Tex. 1994), aff'd sub nom. Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S.

952 (1996), also premised its determination that race

predominated on a thorough review of the intricacies of the

challenged redistricting process. The court reviewed transcripts

of and testimony about the legislature’s floor debates and

regional outreach hearings, id. at 1313-14, Section 5

submissions, id. at 1315, alternative redistricting plans

considered during the legislative process, id. at 1330-31,

newspaper articles published before and during the redistricting

process, id. at 1319, and the use of racial data in the drawing of

boundary lines, id. at 1318-19. Moreover, the court looked

beyond the bounds of the challenge at issue to review testimony

of legislators in previous litigation regarding the same

redistricting process. Id. at 1319-21, 1324. As a result, the

court was able to ferret out inconsistencies and conclude that

“the testimony submitted in this racial gerrymandering case is at

first glance starkly at odds with the explanation for the district’s

21

severely contorted boundaries offered in [the previous

litigation].” Id. at 1321.

In Smith v. Beasley, 946 F. Supp. 1174 (D.S.C. 1996),

the district court conducted a similar review of the entire

legislative process before determining that race dominated the

redistricting experience, including a review of statements and

evidence presented in related litigation and testimony before

legislative committees. See, e.g., id., 946 F. Supp. at 1178-87.

In making this thorough review, the court took note of the lack

of legislative “hearings or evidence or findings as to”

compliance with traditional redistricting factors and compliance

with Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, concluding that these

omissions were evidence that race was the predominant factor.

Id. at 1192-93.

Courts have not reviewed the statements and actions of

legislators in a vacuum, nor have they focused solely on

legislators’ or observers’ statements regarding the role of race

in the redistricting process. Rather, consistent with this

Court’s Shaw jurisprudence, they have also examined the

influence of “traditional” redistricting factors and alternative

justifications for district configurations. See, e.g., Bush v. Vera,

517 U.S. at 959 (discussing significance of traditional districting

principles). In determining the extent to which traditional

districting factors have played a role, courts have looked to

demographic data, the shape of the challenged districts, the

legislature’s use of racial data, the legislature’s consideration

and protection of communities of interest, protection of

incumbent interests, and the history of discrimination in the

jurisdiction. See, e.g., Vera, 861 F. Supp. at 1311 (review of

racial demographics and comparison of 1980 and 1990 census);

id. at 1309 (examining availability of racial data relative to

22

availability of data on other districting factors); Miller, 864 F.

Supp. at 1375-76 (reviewing substantial evidence received from

expert witnesses, religious leaders, community activists, and

legislators regarding communities of interest); Vera, 861 F.

Supp. at 1322 (same); Vera, 861 F. Supp. at 1312, 1317

(extensive review of incumbency interests including historical

accommodations, alternative incumbent-sponsored plans,

negotiations, and maps). It is only after finding that the

evidence “advertises ‘disregard’ for these considerations in

favor of race-based line drawing,” that a court can safely

conclude that race was the predominant factor affecting a given

districting plan. Miller, 864 F. Supp. at 1369.

No such intensive factual inquiry was conducted by the

court below, despite substantial conflicting evidence on the key

issues of purpose and intent submitted by the parties, which

should have occasioned an evidentiary hearing. Instead, and

contrary to the decisional principles announced and applied in

the cases discussed above, the court ignored all factual

complexities, disregarded state legislators’ sworn affidavits

- without hearing their testimony and judging their credibility, and

granted summary judgment to plaintiffs. Unlike the courts

discussed above, each of which weighed a substantial body of

evidence and considered the multiplicity of factors relevant to

a legislature’s redistricting efforts, the court below reached its

conclusion merely by reviewing the configuration of the

, challenged district and examining statistics about a few of the

more than 150 precincts included within it -- then ruling

summarily in favor of the Appellees. That error warrants

reversal of its judgment.

23

B. Because this case necessarily concerns issues

arising under the Voting Rights Act, it

should not have been resolved through

summary judgment

Evidence was presented in this case that the

configuration of the 1997 Remedial Plan was justified by the

State’s need to comply with Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act,

42 U.S.C. § 1973, so as to ensure that minority voting strength

was not diluted during the redistricting process. In order to

determine if compliance with the Act is a compelling

justification for a particular plan in a particular jurisdiction, a

district court would be required to examine the evidence

relating to proving a vote dilution claim under Section 2. This

inquiry is also not well suited for summary adjudication.

In assessing whether a given plan dilutes minority voting

strength, this Court requires trial courts to engage in “a

searching practical evaluation of the past and present reality”

based on a “functional view of the political process.”

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30, 45 (1986) (internal citation

and quotation omitted). The Court has instructed that this

inquiry should include an examination of the history of political

discrimination in the jurisdiction, the extent of racially polarized

voting, and the extent to which minorities have been elected to

political office. Id. at 44-45. This inquiry is fact-intensive and,

given the depth of the analysis required, courts are reluctant to

grant summary judgment in cases involving Section 2, preferring

instead to evaluate disputes over the three Gingles

preconditions, and conclusions based upon the totality of the

circumstances, after a trial. See, e.g., Jeffers v. Clinton, 839 F.

Supp. 612, 616 (E.D. Ark. 1993) (denying summary judgment

in Section 2 case where material issues remained unresolved

24

since “information needed to determine district lines and

population percentages” in hypothetical plan offered by

plaintiffs to establish first Gingles precondition was disputed by

the parties); Johnson v. DeSoto County Board of

Commissioners, 868 F. Supp. 1376, 1382 (M.D. Fla. 1994)

(summary judgment denied because “under the totality of the

circumstances, Plaintiffs’ ability to meet the third necessary

condition is a genuinely disputed material issue of fact which

precludes summary judgment”), rev'd on other grounds, 72

F.3d 1556 (11th Cir. 1996); Mallory v. Eyrich, 707 F. Supp.

947, 954 (S.D. Ohio 1994) (denial of summary judgment to

permit full development of record in order to determine the

proper interpretation of the facts and to resolve disputed expert

analysis). Indeed, the district court in Johnson v. DeSoto

County Board of Commissioners held that “[t]he degree of

racial bloc voting that is cognizable as an element of a § 2 vote

dilution claim will vary according to a variety of factual

circumstances.” 868 F. Supp. at 1382 (citing Gingles, 478 U.S.

at 57-58). In denying the motion for summary judgment in the

DeSoto case, the court noted that under the totality of the

circumstances, determining minority voters’ ability to

participate equally in the political process necessarily requires

“an intense local appraisal of the design and impact” of the

disputed electoral schemes. Jd. (citing Gingles, 478 U.S. at 79).

In deciding cases brought under the Shaw regime,

district courts typically inquire and draw conclusions regarding

the role of Voting Rights Act considerations in the redistricting.

process only after a trial on the merits. For example, in Vera,

the district court acknowledged that “the Legislature embarked

upon Congressional redistricting against the legal backdrop of

the Voting Rights Act,” 861 F. Supp. at 1314, and proceeded

25

to examine factors typically at issue in voting rights litigation.

Relying on testimony before the legislature on the requirements

of the Voting Rights Act and the narrative included with the

State’s Section 5 submissions, the court sought to ascertain the

legislature’s interpretation of the requirements of the Voting

Rights Act. Id. at. 1315-16. The court’s review also included

consideration of Texas’ “well-documented history of

discrimination” in the electoral process, as well as extensive, yet

conflicting, evidence from social scientists, community activists,

and legislators regarding racial polarization in Texas and the

existence of coalition voting between African-American and

Hispanic voters, as well as white bloc voting. Id. at 1315-17.

Similarly, in Smith v. Beasley, the court sought to

determine the role the Voting Rights Act played in the South

Carolina redistricting process through a review of the

redistricting subcommittee’s guidelines for addressing the

requirements of Sections 2 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act, and

evidence establishing that “in South Carolina, voting has been,

and still is, polarized by race.” 946 F. Supp. at 1179, 1202.

The district court in this case never engaged in the level

of analysis necessary to evaluate whether the creation of the

1997 Remedial Plan was justified in light of the State's

responsibilities under the Voting Rights Act. Indeed, if the

district court had timely recognized the Smallwood Appellants’

right to intervene before ruling, they would have occupied a role

similar to the one assumed by the defendant-intervenors in Shaw

v. Hum}? introducing evidence and presenting arguments

concerning the State’s responsibilities under the Voting Rights

Act. For example, as parties, the Smallwood Appellants would

8See supra note 4.

26

have presented evidence regarding the history of political

exclusion of the State’s African-American population and would

have argued that the State was required to consider this history,

and take particular care not to dilute minority voting strength,

in fashioning a remedy for the constitutional violation found by

this Court. Also, the Smallwood Appellants could have

introduced evidence showing that the Appellees’ proposed plans

might be vulnerable to an attack under Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act.

Because Shaw cases often involve issues arising under

the Voting Rights Act, they require full development of the

underlying facts for proper resolution, which will ordinarily

necessitate evidentiary hearings. See County Council v. United

States, 555 F. Supp. 694, 706 (D.D.C. 1983) (resolution of

issues raised by violations of Section 5 and Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act “depends on facts which should be

developed at trial”); City of Rome v. United States, 450 F.

Supp. 378, 384 (D.D.C. 1978) (determination of issues raised

by the Voting Rights Act should be resolved after a full

opportunity for discovery). For this reason, the grant of

summary judgment below was erroneous.

27

II. The District Court Erred in Ruling that Race Was

the Predominant Factor in the Creation of the

Twelfth Congressional District

A. The court erred in sanctioning the Appellees’

argument that race predominated in the

development of the 1997 Remedial Plan

because that plan did not evidence the

legislature’s complete abandonment of the

1992 Plan as a starting point for fashioning

the remedy.

The Appellees proposed below, and the district court

tacitly approved, a requirement that the State abandon the

previously challenged plan in its entirety and develop a remedial

‘plan without reference to any of the features of the prior plan,

including even the race-neutral redistricting principles the State

chose to recognize in fashioning the earlier plan. As discussed

supra in the Statement of the Case, Appellees argued below that

the 1997 Remedial Plan must be declared unconstitutional

because it was the “fruit of the poisonous tree” (the plan

invalidated by Shaw v. Hunt).

Appellees’ “fruit of the poisonous tree” theory would

require a state remedying a Shaw violation to do substantially

more than correct the constitutional defect found in a

challenged district; under Appellees’ approach, nothing less than

the complete reconstruction of the invalidated plan is an

adequate remedy for the constitutional violation. This novel

theory is fundamentally at odds with this Court’s precedents.

There is no support in the decisions of this Court for the

contention that a redistricting plan drawn to remedy a

constitutional violation under Shaw is constitutionally invalid

unless the State completely discards its original plan and

28

abandons even the traditional, race-neutral redistricting

considerations that were recognized in the original plan.

Appellees are entitled only to have the legislature devise

a plan in which traditional, race-neutral redistricting principles

are not needlessly subordinated to racial considerations. The

“fruit of the poisonous tree” argument places the State in the

untenable position of ignoring the complicated mix of factors

that necessarily and legitimately influence the redistricting

process, in order to cure the prior constitutional violation. This

approach makes little real-world sense. The drafter of a

remedial plan designed to cure a defect in one district in a prior

plan must, of necessity, consider a substantial body of political,

geographic, and demographic data, as well as one-person, one-

vote requirements and traditional redistricting policies in the

jurisdiction. Decisions about reshaping the challenged district

simply cannot be made without regard to their effect on the

overall plan, including their effect on prior partisan political

balances. It would, therefore, be entirely realistic for a State to

seek to make the fewest alterations possible to a plan, if doing

so would assist in meeting its other redistricting goals.

Appellees’ argument would seriously impact settlement

and remedial possibilities in voting rights cases, as it would

dramatically limit States’ abilities to develop plans that cure

statutory and Constitutional objections while also taking into

consideration legitimate political interests and other race-neutral

redistricting criteria.

Rather than demand that a State forsake the myriad

interests that it attempted to recognize and promote in a

challenged plan, this Court has consistently accorded great

deference to the States’ policy choices in the redistricting

process and has repeatedly held that the redistricting policy

29

choices of the State should be set aside by a federal court only

to the extent necessary to remedy a violation of federal law.

See, e.g., White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. 783, 795 (1973) (in

devising a remedy for a federal constitutional violation, a court

“should follow the policies and preferences of the State,

expressed in statutory and constitutional provisions or in

reapportionment plans proposed by the state legislature,

whenever adherence to state policy does not detract from the

requirements of the Federal Constitutions”); see also Voinovich

v. Quilter, 507 U.S. 146, 156 (1993) (“[F]ederal courts are

bound to respect the States’ apportionment choices unless those

choices contravene federal requirements”).

When a legislative body devises a remedial plan, a court

must “accord great deference to legislative judgments about the

exact nature and scope of the proposed remedy.” McGhee v.

Granville County, 860 F.2d 110, 115 (4th Cir. 1988). See also

White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. at 795-96 (1973); Tallahassee

Branch of NAACP v. Leon County, 827 F.2d 1436, 1440 (11th

Cir. 1987). Where, as here, the State has enacted a new plan

that fully remedies the Shaw violation and complies with all

applicable federal and state constitutional and - statutory

provisions, there is no basis for federal judicial interference with

its implementation. Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 U.S. 535, 540

(1978), see also Burns v. Richardson, 384 U.S. 73, 85 (1966)

(“A State’s freedom of choice to devise substitutes for an

apportionment plan found unconstitutional, either as a whole or

in part, should not be restricted beyond the clear commands of

the Equal Protection Clause”); Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. at 899

n.9 (“states retain broad discretion in drawing districts to

comply with the mandate of § 2”) (citing Voinovich v. Quilter,

507 U.S. 146 (1993) and Growe v. Emison, 507 U.S. 25

30

(1993)).

Moreover, States such as North Carolina have a

legitimate interest in minimizing disruption to their political

process by, for example, ensuring that incumbents are

protected, prior partisan balances are maintained, and districts

surrounding the invalidated district(s) are preserved intact to the

extent possible in a remedial plan.’ In fact, this Court and lower

courts have recognized the necessity for jurisdictions to

consider these issues as they devise remedial plans and have

thus accorded states broad deference in the redistricting

process. See, e.g., Lawyer v. Department of Justice, 521 U.S.

___,117 8. Ct. at 2192-3 (1997), aff’g Scott v. United States,

920 F. Supp. 1248, 1255 (M.D. Fla. 1996); Shaw v. Hunt, 517

US. at 899 n.9; Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. at 915; Upham v.

Seamon, 456 U.S. 37, 42 (1982); White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. at

794-95 (1973).%°

® Although it is undisputed that the State sought to protect all of the

incumbent members of the congressional delegation and preserve the

partisan balance of six Democrats and six Republicans that resulted from

elections held under its original plan, Appellees have suggested that the State

must exclude the Twelfth District's African-American Congressman from

such protection. See Motion to Dismiss or, in the Alternative, to Affirm at

27. By arguing that it was per se unconstitutional for the State to protect the

incumbency of the Twelfth District’s African-American Congressman to the

same extent as it protected other incumbent members of Congress, Appellees

urge the adoption of a double standard that is intolerable under the decisions

of this Court. See, e.g., Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. at 928 (O'Connor, J.,

concurring); Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. at 996 (Kennedy, J., concurring).

1%This is consistent with this Court’s longstanding view that the

governmental entity must be given the first opportunity to propose a remedial

plan after a voting rights violation is found. McDaniel v. Sanchez, 452 U.S.

130, 150 n.30 (1981). -

31

This Court’s decision last term in Lawyer underscores

the district court’s error in adopting Appellees’ “fruit of the

poisonous tree” theory. Both the district court in Scott and this

Court in Lawyer upheld a Florida state legislative district that

was redrawn after a finding of a Shaw violation. This Court

upheld the remedial district notwithstanding (a) its resemblance

to the original plan’s 21st Senate District, (b) the fact that the

plan’s drafters used the original 1992 redistricting plan as a

starting point, and (c) the district’s continued majority-minority

status. Neither this Court nor the district court deemed

Florida's remedial plan “tainted” simply because it used the

challenged plan as its base. Moreover, neither court questioned

Florida's stated, race-neutral interest in preserving electoral

stability by avoiding needless disruption of the political

relationships that had developed between the time of the

original enactment of the challenged plan and the date that the

remedial plan was devised.

If the court below had properly applied these principles,

it would have rejected appellees’ “fruit of the poisonous tree”

argument and approved the 1997 Remedial Plan. The district

court was bound to approve the legislature’s remedial plan to

the extent that it did not violate any federal or state

constitutional or statutory requirements. The court below did

not have the remedial power, and the Appellees do not have a

constitutional right, to dictate the State’s redistricting priorities

beyond what is required to eliminate the equal protection

violation this Court initially found in Shaw v. Hunt. This Court

should therefore reverse the district court’s erroneous adoption

of the “fruit of the poisonous tree” theory and approve the 1997

Remedial Plan enacted by the North Carolina legislature.

R

E

L

A

nF

SORT

32

B. In jurisdictions such as North Carolina, with

a history of prior discrimination and

minority vote dilution, and in which voting

patterns remain racially polarized,

districting must be sufficiently race-

conscious to avoid violating Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act, but that circumstance

does not establish that race “predominates”

so as to trigger “strict scrutiny.”

As noted supra in the Statement of the Case, the court

below failed to assess most of the evidence presented by the

parties on Appellees’ motion for summary judgment. Instead,

the court recited statistics concerning the racial composition and

political party registration of voters in a small number of

‘precincts placed within or without the Twelfth District by the

1997 Remedial Plan adopted by the North Carolina General

Assembly. Without even addressing the other factors that state

legislators took into account in the redistricting process, the

court concluded from its limited factual recitation not only that

the Remedial Plan was race-conscious, but also that it must be

struck down.

In the circumstances of this case, this ruling amounted

to a holding, contrary to this Court’s repeated admonitions, that

race-conscious districting is presumptively unconstitutional.

Because such a rule is incapable of rational application, would

eviscerate the protections against minority vote dilution

provided by Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42

U.S.C. § 1973, and is flatly inconsistent with this Court’s Shaw

decisions, the judgment below must be reversed.

As this Court has held, Appellees’ evidentiary burden in

this case is to show that “race for its own sake, and not other

33

districting principles, was the legislature’s dominant and

controlling rationale in drawing its district lines,” Bush v. Vera,

517 U.S. at 952, quoting Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. at 913,

and “that other, legitimate districting principles were

‘subordinated’ to race.” Bush, 517 U.S. at 958. See generally

id. at 259-68. It is insufficient for Appellees to show, as they

attempted to do here, merely that inclusion of African-American

voters was one factor influencing the contours of a district in

the plan adopted by the legislature — or even that the entire

districting process was carried out “with consciousness of race,”

Bush, 517 U.S. at 1051. As Justice O’Connor has observed:

States may intentionally create majority-minority

districts and may otherwise take race into consideration,

without coming under strict scrutiny. Only if traditional

districting criteria are neglected, and that neglect is

predominantly due to the misuse of race, does strict

scrutiny apply.

Bush, 517 U.S. at 993. (O’Connor, J., concurring) (emphasis

in original); see also United States v. Hays, 515 U.S. 737, 745

(1995) (“We recognized in Shaw. . .that the ‘legislature always

is aware of race when it draws district lines, just as it is aware

of age, economic status, religious and political persuasion, and

a variety of other demographic factors. That sort of race

consciousness does not lead inevitably to impermissible race

discrimination’) (citation omitted) (emphasis in original).

In Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. at 653, this Court held that

it would be the extraordinary case in which strict scrutiny would

apply. Indeed, in Shaw, Miller, and Bush, the district courts

applied strict scrutiny only after they determined that race

played a predominant role in the design of the districts at issue.

Miller, 515 U.S. at 928 (O’Connor, J., concurring); Shaw v.

34

Hunt, 517 U.S. at 903; Bush, 517 U.S. at 952. And those

determinations were not based upon mere “race consciousness.”

For example, in Shaw, a full trial on the merits developed what

this Court termed sufficient “direct evidence” that the State’s

“overriding purpose” was to “create two congressional districts

with effective black voting majorities” and that other

considerations “came into play only after the race-based

decision had been made.” Shaw, 517 U.S. at 906 (original

emphasis omitted and emphasis added). In Miller, the State

conceded that the district at issue was the “product of a desire

by the General Assembly to create a majority black district,”

Miller, 515 U.S. at 918 (emphasis added), and that the creation

of the district would “violate all reasonable standards of

compactness and contiguity.” Id. at 919. In granting summary

judgment to Appellees in this matter, the court below made no

such findings.

Equally significant, the court below failed to give any

consideration — much less appropriate weight — to the need of

the North Carolina General Assembly, in any redistricting that

it undertook, -to be sufficiently “race conscious” so as to avoid

diluting minority voting strength. Although the General

Assembly’s primary goals in enacting the 1997 Remedial Plan

were to correct the prior constitutional violation found by this

Court in Shaw v. Hunt and to preserve the congressional

delegation’s partisan balance, the State was also under an

obligation to fulfill these objectives without diluting minority

voting strength.

In Shaw v. Hunt, the Court assumed without argument

that “§ 2 could be a compelling interest” justifying even a plan

drawn predominantly on a racial basis, if the “[North Carolina]

. General Assembly believed a second majority-minority district

33

was needed in order not to violate § 2, and. . .the legislature at

the time it acted had a strong basis in evidence to support that

conclusion” when it created the 1992 plan. Shaw, 517 U.S. at