Garner v. Louisiana Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Garner v. Louisiana Brief for Petitioners, 1961. 72afe9c7-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4fe0ca8a-cc06-4087-937a-f89a969508fe/garner-v-louisiana-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

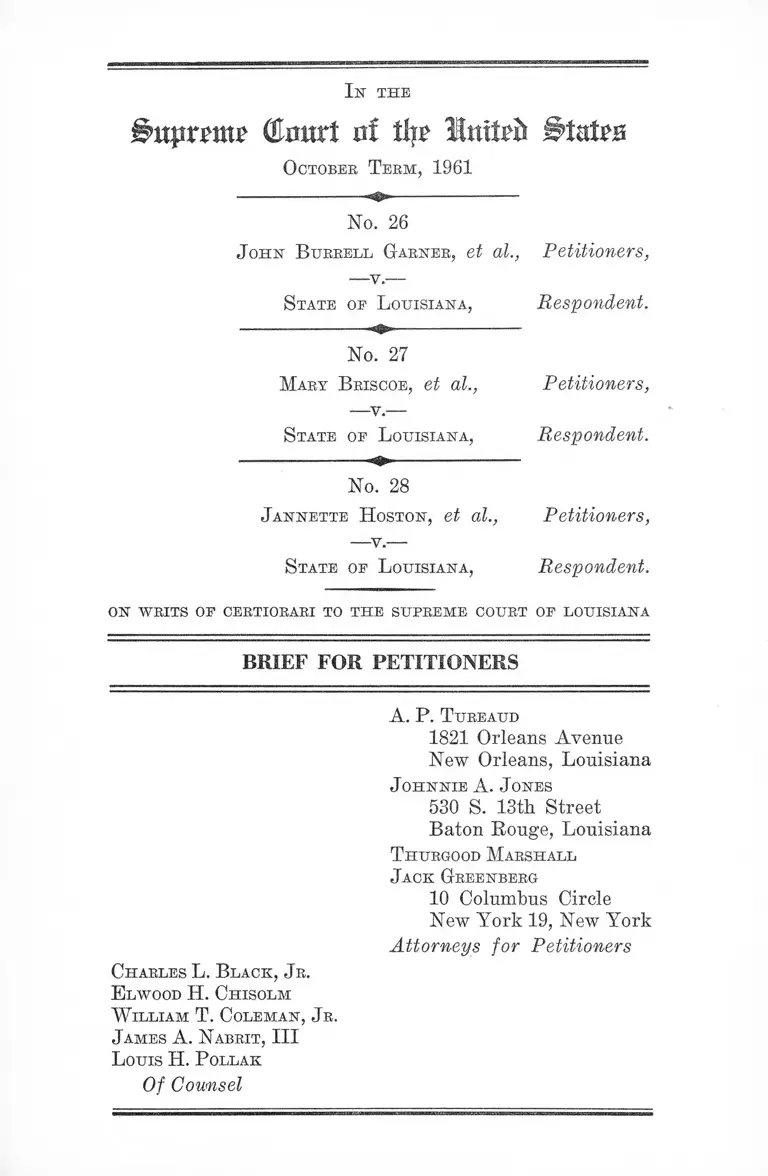

I n t h e

Isuprme (Hiwrt ni tlje Imtpft Btutm

O ctober T erm , 1961

No. 26

J o h n B urrell Garner, et al.,

— v.—

S tate op L ouisiana ,

Petitioners,

Respondent.

No. 27

M ary B riscoe, et al., Petitioners,

S tate of L ouisiana , Respondent.

No. 28

J a n nette H oston, et al., Petitioners,

—v.—

S tate op L ouisiana , Respondent.

O S’ W R IT S O P C ER TIO R A R I TO T H E S U P R E M E CO U RT O P L O U IS IA N A

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

A. P . T ureaud

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana

J o h n n ie A . J ones

530 S. 13th Street

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

T hurgood M arshall

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Petitioners

Charles L, B lack , J r.

E lwood H . Ch iso lm

W illiam T. C olem an , J r.

J ames A. N abrit, III

Louis II. P ollak

Of Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinions Below........................................ 1

Jurisdiction .................................................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved...... 2

Questions Presented ...................................................... 3

Statement ................. 4

Summary of Argument .................................................. 7

Argument ........................................................................ 8

A. Petitioners were convicted on the theory that

their failure to obey the custom of segregation

was itself unlawful; their convictions therefore

clearly contravene the decisions of this Court

that racial segregation, enforced by state author

ity, violates the Fourteenth Amendment.............. 8

(1) Enforcement of segregation in these cases

was both formally and substantially by “state

action” ............... ............................................. 8

(2) Even if it be urged that there is in these cases

a relevant component of formally “private”

action, that action is substantially infected

with state power. “Private” segregation in

these cases was in obedience to a statewide

custom, which in turn has long enjoyed the

support of Louisiana as a polity ................. 18

B. Petitioners’ convictions denied due process of law,

in that they rested on no evidence of an essential

element of the crime .................... ........................ 24

C. Petitioners were convicted of a crime under the

provisions of a state statute which, as applied to

their acts, is so vague, indefinite, and uncertain

as to offend the due process clause of the Four

teenth Amendment ................................................ 28

D. The decision below conflicts with the Fourteenth

Amendment, in that it unwarrantedly penalized

petitioners for the exercise of their freedom of

expression .................................... 36

Conclusion ...................... 38

T able of Cases

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60................................18, 27

Burstyn v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495 ................................... 37

Civil Bights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 ................................19, 20, 24

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 .......................................18, 27

Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315................................ 37

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903 ..................................... 8

Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879 ..................... 8

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451............................ 29

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501................................. 19, 36

Munn v. Illinois, 94 U. S. 113......................................... 19

Napue v. Illinois, 360 U. S. 264 ..................................... 16

New Orleans City Park Improvement Assn. v. Detiege,

, 358 U. S. 54 ...................................... .......................... 8

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587 ........... ............... ......... 16

11

PAGE

I l l

Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U. S. 319........ ....................... 29

Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 147.................................. 37

State v. Sanford, 203 La. 961, 14 So. 2d 778 (1943) .....28, 32

State v. Truby, 211 La. 178, 29 So. 2d 758 (1947).......... 34

Stromberg v. California, 283 IT. S. 359 .........................17, 36

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 ................................ 37

Terry v. Adams, 345 U. S. 461 ..... .......... ....................... 20

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 ............... .........26, 28

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88................................ 36

Town of Ponchatoula v. Bates, 173 La. 824, 138 So.

851 (1931) ................ ..... .............................................. 33

Williams v. North Carolina, 317 IT. S. 287 ..................... 17

Winters v. New York, 333 IT. S. 507 ................................ 37

PAGE

S tatutes and Constitutional P rovisions

United States Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment .... 2

28 U. S; C. §1257(3) ....... ............................................... 2

Louisiana Acts, 1934, No. 227, §1... ....... 32

Louisiana Acts, 1960, No. 630 ...... 22

LSA-R.S. 4:5 .................................................................. 23

LSA-R.S. 4 :451, Acts 1956, No. 579 ................ 22

LSA-R.S. 14:3 ................................................................ 31

LSA-R.S. 14:8 ................................................................ 31

LSA-R.S. 14:56, Act 1960, No. 77.... 31

LSA-R.S. 14:79 .............................................................. 23

IV

LSA-R.S. 14:103 ....................................... 2,6,11,15,17,24,

30, 31, 32, 34, 35

LSA-R.S. 14:103.1, Acts 1960, No. 69, §1.....................31, 32

LSA-R.S. 14:104 ............................................................. 34

LSA-R.S. 15:752 ................................................ -........ . 23

LSA-R.S. 17:443, 17:462, 17:493, 17:523 ....................... 23

LSA-R.S. 23:971-23:972 .................................................. 23

LSA-R.S. 33:4558.1 ....................................................... 23

LSA-R.S. 45:1301-45:1305 .............................................. 23

Ot h er A utho rities

Hand, The Bill of Rights ............................................... 20

New Orleans Times-Picayune, May 11,1960, p. 2, Sec. 3,

Col. 1-7 ........................................................................ 22

Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow (Oxford

Univ. Press, 1957) ....................................................... 22

PAGE

I n t h e

Supreme Court of % luttrb

O ctobee T e e m , 1961

No. 26

J o h n B urrell Garner, et al.,

S tate of L ouisiana ,

No. 27

M ary B riscoe, et al.,

S tate of L ouisiana ,

No. 28

J a n nette H oston, et al.,

■—v.—

S tate of L ouisiana ,

on writs of certiorari to t h e suprem e court

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Petitioners,

Respondent.

Petitioners,

Respondent.

Petitioners,

Respondent.

O F L O U IS IA N A

Opinions Below

The brief opinions rendered in these cases by the Su

preme Court of Louisiana, refusing petitioners’ applications

2

for writs of certiorari, mandamus and prohibition, and

finding no error in the rulings of law by the Nineteenth

Judicial District Court, Parish of East Baton Rouge, Lou

isiana, are not reported. These identical opinions are set

out in each printed record (R. Darner 53; R. Briscoe 56;

R. Hoston 55).

The “Findings of Guilt” by the Nineteenth Judicial Dis

trict Court in the respective cases also appear in the printed

records (R. Garner 37; R. Briscoe 38-39; R. Hoston 38-39).

Jurisdiction

The judgments of the Supreme Court of Louisiana in

these cases were rendered on October 5, 1960. On March 20,

1961, this Court granted petitions for writs of certiorari to

the Supreme Court of Louisiana, and ordered these eases

consolidated for argument. The jurisdiction of this Court

rests on 28 U. S. C. §1257(3).

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

2. The Louisiana statutory provision involved is LSA-

R.S. 14:103:

“Disturbing the peace is the doing of any of the fol

lowing in such a manner as would foreseeably disturb

or alarm the public:

(1) Engaging.in a fistic encounter; or

(2) Using of any unnecessarily loud, offensive, or in

sulting language; or

(3) Appearing in an intoxicated condition; or

3

(4) Engaging in any act in a violent and tumultuous

manner by three or more persons; or

(5) Holding of an unlawful assembly; or

(6) Interruption of any lawful assembly of people; or

(7) Commission of any other act in such a manner as

to unreasonably disturb or alarm the public.

Whoever commits the crime of disturbing the peace

shall be fined not more than one hundred dollars, or

imprisoned for not more than ninety days, or both.”

Questions Presented

1.

Whether conviction of petitioners for disturbing the

peace, on the ground that their mere presence at counters

reserved by custom for whites constitutes in itself such an

offense, amounts to an unconstitutional enforcement of

racial segregation by state power.

2.

Whether conviction of petitioners of disturbance of the

peace, on records barren of evidence of present or threat

ened disturbance, deprived them of due process of law, in

that they were convicted of a crime without evidence of

guilt.

3.

Whether the application to petitioners of a statute setting

highly vague standards of guilt deprived them of liberty

without due process.

4.

Whether petitioners’ constitutionally protected right to

free expression was violated by the application to them of

4

the disturbance of the peace statute, under the circum

stances of this case.

Statement

On March 29,1960, petitioners in Gamer (No. 26) entered

Sitman’s Drug Store, an establishment in Baton Rouge

which served Negroes without discrimination at the coun

ters in the drug store section and considered them “very

good customers” (R. Garner 30, 32). They seated them

selves at the lunch counter and one of them ordered coffee

(R. Garner 30). The owner refused to serve them, but he

neither requested them to move nor did he call the police

(R. Garner 30-31). They were arrested by Captain Weiner

(R. Garner 34), the arresting officer in all of these cases

(see also R. Briscoe 34; R. Hoston 35). He had been sum

moned by the police officer on the beat (R. Garner 34), who

made the call on his own initiative, without having received

a complaint from any civilian (R. Garner 34-35). The

arrests were made because petitioners “were sitting at a

counter reserved for white people” and their “mere pres

ence” there constituted a disturbance of the peace (R. Gar

ner 35, 36).

In the Briscoe case (No. 27) petitioners sought service

at a lunch counter at the Greyhound Bus Station in Baton

Rouge on March 29,1960 (R. Briscoe 30). The waitress told

them “they would have to go on the other side to be served” :

“colored people are supposed to be on the other side” (R.

Briscoe 30). When they “just kept sitting there” (R. Bris

coe 31), and they “didn’t do anything else” (R. Briscoe 33),

a bus driver or “some woman” called the police department

(R. Briscoe 33, 34). Captain Weiner responded to the call

and “saw these people sitting at the lunch counter” (R.

Briscoe 34). Forthwith, without having any conversation

with the proprietors or employees, he asked these “stu

5

dents” to move (R. Briscoe 36) and, when they didn’t take

this “opportunity to get up and leave” or “say anything”

(R. Briscoe 35), he placed them under arrest because “They

were disturbing the peace by the mere presence of their

being there [‘in the section reserved for wdiite people’ (R.

Briscoe 36)]” (R. Briscoe 38).

Petitioners in the Boston case (No. 28), on March 28,

1960, seated themselves as customers at a lunch counter at

the S. H. Kress & Company in Baton Rouge (R. Hoston 29),

a store which customarily allowed all white and colored cus

tomers to “make other purchases [save food] at the same

counters at the same time” (R. Hoston 31). No signs indi

cated this, but the existence of this “custom” was communi

cated somehow to petitioners and other Negro students

or customers by waitresses and stewards (R. Hoston 32).

On this occasion, the waitress did not ask them to move, nor

were they distinctly refused service; rather they were

“offer[ed] service at the counter across the aisle” (R. Hos

ton 29, 32, 34). When petitioners “continued to sit”, the

store manager “advised the police department that they

were seated at the counter reserved for whites, and within

a short time the officers [Captain Weiner and Chief Arrighi

(R. Hoston 35-36)] came in . . . and spoke to some of

them” (R. Hoston 30). The officers “asked them to leave

. . . the lunch counter reserved to white people. One of the

[petitioners] said something about wanting to get a glass

of tea but she was told they were disturbing the peace [‘by

sitting there’ (R. Hoston 37)] and asked to leave again,

and when none of them made a move to get up and leave

Chief Arrighi told [Captain Weiner] to place them under

arrest” (R. Hoston 36).

In each of these three cases, the information filed against

petitioners indicated their race by adding “CM” or “CF”

after their names (R. Garner 2; R. Briscoe 2; R. Hoston 2)

6

and, charged that they “feloniously did unlawfully violated

Article 103 (Section 7) of the Louisiana Criminal Code in

that they refused to move from a cafe counter seat . . .

after being requested to do so by the agent of [the establish

ment] ; said conduct being in such a manner as to unreason

ably and foreseeably disturb the public . . . ” (E. Garner 1;

E. Briscoe 1; E. Hoston 1).

Thereafter, following denials of their motions to quash

and applications for writs of certiorari, mandamus and

prohibition to review the denials of said motions (E. Garner

11-12, 25; E. Briscoe 11-12, 25; E. Hoston 10-11, 24), peti

tioners were tried and convicted in the Nineteenth Judicial

District Court on June 2, 1960 (E. Garner 29, 37, 38; E.

Briscoe 29, 38-39, 40-41; E. Hoston 28, 38-39, 40). On July

5, 1960, the trial court overruled petitioners’ motions for

new trials and sentenced each of them to 30 days in jail and

to pay a fine of $100.00 and costs, or, in default of payment

thereof, to 90 days in jail, with both parts of the jail sen

tence to run consecutively in the event of non-payment of

the fine and costs (E. Garner 41-42; E. Briscoe 43-44; E.

Hoston 43-44). Timely applications for a writ of certiorari,

mandamus and prohibition made to the Supreme Court of

Louisiana, inviting its supervisory jurisdiction to review

the judgments and sentences entered against petitioners by

the trial court, were refused in an opinion and judgment

filed on October 5, 1960 (E. Garner 53; E. Briscoe 56; E.

Hoston 55-56). At each stage of the proceedings in the

Nineteenth Judicial District Court and the Supreme Court

of Louisiana, petitioners objected to the criminal prosecu

tions on the ground that the same deprived them of privi

leges, immunities and liberties without due process of law

as well as the equal protection of the laws under the Four

teenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution (E. Garner

7, 14, 17, 23, 40, 43, 45-46, 51; E. Briscoe 8, 14, 16-17, 23,

42, 45, 47-48, 53-54; B. Hoston 7, 13, 15-16, 22, 42, 45, 47-48,

53-54). These constitutional objections, however, as afore-

shown, were rejected at all stages of the litigations.

Summary o f Argument

A.

These records show clearly that petitioners were con

victed of not observing the custom of segregation. A change

in name cannot make such a conviction less obnoxious to

the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

“State action” is present, both through police and court

action and because the nominally “private” segregation that

was in the background of these cases was followed in

obedience to statewide custom which, for decades and con

tinuously to the present, has been supported by official state

law and policy.

B.

These petitioners were convicted of “disturbing the

peace”. But the records decisively establish that no dis

turbance of the peace either took place or was threatened,

and that the actions of petitioners were in every respect

decent and orderly. The only “disturbance” shown was the

bare presence of petitioners in a place where Negroes were

not “supposed” to be. Unless, therefore, the showing of

this “presence” alone be held to support a finding of dis

turbance (and in that event Point A, supra, is clearly

applicable), the petitioners have been convicted without

any evidence of criminality—the most elementary denial of

due process.

C.

The statute under which petitioners were convicted is too

vague to set any standard for the guidance of persons sub

8

ject to it, or of officials. Nothing in its history or in state

judicial constructions clears up its ambiguities. It therefore

fails to meet one of the most fundamental requirements of

due process.

D.

The primary function of petitioners’ conduct was that of

expressing belief and of claiming what they conceived to

be fair treatment. Such an expression enjoys federal con

stitutional protection. The state has infringed this right to

free expression by punishing petitioners solely because of

its exercise, without any valid state interest in such repres

sion.

ARGUMENT

A. Petitioners were convicted on the theory that their

failure to obey the custom o f segregation was itse lf un

lawful; their convictions therefore clearly contravene

the decisions o f this Court that racial segregation, en

forced by state authority, violates the Fourteenth Amend

ment.

( 1 ) E n fo rc e m e n t o f seg reg a tio n in these cases was b o th

fo rm a lly an d su b stan tia lly by “ sta te ac tio n ” .

These cases on their own records present a very simple

situation. Beyond doubt, Louisiana cannot make it a crime

for a Negro to seek service at a counter reserved by custom

for whites, for such a law is simply and solely a state law

commanding segregation. Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903;

New Orleans City Park Improvement Assn. v. Detiege,

358 IT. S. 54; Holmes v. City of Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879. But

that is exactly what Louisiana has done in these cases.

Very little skill in algebra is required to reach the conclu

sion that a law making a given action a “disturbance of the

9

peace”, and then punishing this “disturbance of the peace”,

is the very same thing as a law punishing the same action

under a more ingenuous nomenclature.

In each of these eases, the police and the state courts

proceeded to arrest and conviction on the clear theory that

the mere presence of a Negro at a “white” counter was

unlawful in itself. This is enough to vitiate the convictions,

though petitioners will shortly show (Point A(2), infra)

that the same result must follow even if full account be

taken of the nominally “private” segregation followed by

the proprietors of the establishments concerned.

In the Hoston case (No. 28), the petitioners were charged

with a disturbance of the peace “in that they refused to

move from a cafe counter seat at Kress’ Store . . . after

having been ordered to do so by the agent of Kress’ Store;

. . . ” But the transcript of testimony unequivocally and

clearly shows, on the State’s own testimony, that no such

order was ever given. Mathews, the store manager, testi

fied for the State on direct, that the petitioners sat next

to him at the “white” counter, that they were denied service

there, and were told they would be served at the “colored”

counter. Then he testified as follows:

Q. Were they requested to move over to the counter

reserved for colored people? A. No, sir.

Q. They weren’t asked to go over there? A. They

were advised that we would serve them over there

(R. Hoston 29).

And again, on cross:

A. As I stated before, we did not refuse to serve them.

We merely advised them they would be served on the

other side of the store (R. Hoston 33).

10

This is careful testimony; in the absence of anything

tending to weaken it, it leaves it very clear that this man

ager followed a compromise course. He did not serve these

petitioners, but did not tell them to move. The trial court,

summing up this witness’ testimony, shows clear apprecia

tion of this distinction. Again on cross, the following was

said:

Q. Then why did you ask these defendants to move

from this cafe counter?

The Court: I think he hasn’t testified to that. He

said he advised them that they would be served else

where, over at the other counter. He said he did not

refuse to serve them at this particular counter. What

he did was, he advised them they would be served

over at the other counter. . . . (R. Hoston 34)

When Capt. Weiner of the Baton Rouge City Police took

the stand, the nature of the offense came clear. On direct:

A. Chief Arrighi and I had gone to the store and we

entered the store from the Main Street entrance which

was the closest to the lunch counter, and we noticed

several of these people sitting at the counter. Chief

Arrighi proceeded to the counter where they were

sitting and asked them to leave.

Q. What counter were they seated at? A. They were

seated at the lunch counter reserved for the white

people. One of the defendants said something about

wanting to get a glass of ice tea but she was told they

were disturbing the peace and violating the law by

sitting there and asked to leave again, and when none

of them made a move to get up and leave Chief Arrighi

told me to place them under arrest (R. Hoston 36).

11

And again on cross:

Q. Do I take by that that they hadn’t done anything

other than sit at these particular cafe counter seats

that yon consider disturbing the peace? A. That’s the

only thing that I saw happen.

# # # # *

Q. How were they disturbing the peace? A. By sit

ting there.

Q. By sitting there? A. That’s right.

# # * # #

Q. It is your testimony their mere sitting there was

disturbing the peace, is that right sir? A. That’s right.

Q. And that is because thej7 were members of the

negro race? A. That was because that place was re

served for white people (R. Boston 37).

In its statement accompanying the finding of guilty, the

trial court showed its clear appreciation of the nature of

the offense:

The Court: . . . they took seats at the lunch

counter which by custom had been reserved for white

people only. They were advised by an employee of

that store, or by the manager, that they would be

served over at the other counter which was reserved

for colored people. They did not accept that invita

tion; they remained seated at the counter which by

custom had been reserved for white people. The offi

cers were called and the defendants continued to

remain seated at this particular counter. That testi

mony is uncontradicted, and, in the opinion of the

Court, the action of these accused on this occasion

was a violation of Louisiana Revised Statutes, Title

14, Section 103, Article 7, in that the act in itself,

12

their sitting there and refusing to leave when re

quested to, was an act which foreseeably could alarm

and disturb the public, . . . (R. Hoston 38, 39)

Here, then, is the Hoston case: Petitioners, Negroes, were

seated at a counter customarily frequented by whites. No

private person told them to move or to leave. A policeman

entered and told them to leave, on the ground that, merely

by being at the white counter, they were “disturbing the

peace.” They remained, and were arrested and convicted

of disturbance of the peace, on the ground, stated by the

trial court, “that the act in itself, their sitting there and

refusing to leave when requested to [by a policeman] ” was

such disturbance. (Emphasis supplied.)

This is simple and pure segregation by state power in the

most classic sense, and it is nothing else. The state, acting

throughout by its own formal agents, has ordained that it is

a crime for a Negro to sit at a “white” counter, and then has

tried the petitioners for that very crime, and convicted

them.

The Garner case (No. 26) is similar. The information

charged a disturbance of the peace, in that petitioners “re

fused to move from a cafe counter seat at Sitman’s Drug

Store . . . after having been ordered to do so by the agent

of Sitman’s Drug Store.” Again, the record affirmatively

shows, on the State’s own uncontradicted testimony, that

no such order was given. Willis, the drug store owner,

testified:

Q. Go ahead. A. They occupied two seats and their

presence there caused me to approach them a short

time later and advise them that we couldn’t serve

them, and I believe after that the police came and ar

rested them and took them away.

[fol. 39] Q. Now, when you advised them you couldn’t

13

serve them did they get up and leave or,— A. No, one

asked for coffee,—said they just wanted coffee.

Q. That was after you told them you couldn’t serve

them? A. That was the conversation they had with me.

I told them we couldn’t serve them and one of the boys

said he wanted some coffee (R. Garner 30). (Emphasis

supplied.)

Willis did not call the police, but Captain Weiner was

summoned, as he testified on direct for the State:

Q. Tell the Court exactly what was done? A. Well,

I received a call at police headquarters from the officer

on the beat, Officer Larsen. He told me that there

were two negroes, sitting at the lunch counter at Sit-

man’s Drug Store. I told him to just stand by until

we arrived at the scene. Major Bauer approached them

and told them that they were violating the law by sit

ting there and asked them to leave. One of them men

tioned something about an umbrella that he had bought

and he couldn’t see why he couldn’t sit at the lunch

counter. He told them again that they were violating

the law and when they didn’t make any effort to leave

we placed them under arrest and brought them to police

headquarters.

Q. Did you see Mr. Willis over there? A. No, I

didn’t see Mr. Willis. I ’m assuming Mr. Willis is the

manager, but we didn’t talk to anyone in the place other

than the two defendants (R. Garner 34).

The reason for the warning and arrest appears clearly in

Weiner’s testimony on cross:

Q. And when you arrived on the scene you saw these

defendants sitting at this lunch counter? A. That’s

right.

14

Q. And based upon what you call a violation of the

law you arrested them, is that correct? A. That’s right

(E. Garner 35).

# * # # #

Q. Is it a fact that they were negroes that you ar

rested them? A. The fact that they were violating the

law.

Q. In what way were they violating the law? A. By

the fact that they were sitting at a counter that was

reserved for white people.

̂ ^

Q. . . . Do you know positively that there is such

a law? A. The fact that they were sitting there and

in my opinion were disturbing the peace by their mere

presence of being there I think was a violation of Act

103.

# # # # *

By Counsel Jones:

Q. The mere presence of these negro defendants sit

ting at this cafe counter seat reserved for white folks

was violating the law, is that what you are saying ?

A. That’s right, yes (R. Garner 35, 36).

Again, the trial court, in its remarks accompanying the

finding of guilt, shows clear appreciation of the fact that

the culpability of the petitioners had to rest on their mere

failure to observe the custom of segregation:

. . . these two accused were in this place of business on

the date alleged in the bill of information, and they

were seated at the lunch counter in a bay where food

was served and they were not served while there, and

officers were called and after the officers [fol. 47] ar

rived they informed these two accused that they would

15

have to leave, and they refused to leave. Whereupon,

the officers placed them under arrest for violating the

law, specifically Title 14, Section 103, subsection 7. The

Court is convinced beyond a reasonable doubt of the

guilt of the accused from the evidence produced by

the State, for the reason that in the opinion of the

Court, the action and conduct of these two defendants

on this occasion at that time and place was an act done

in a manner calculated to, and actually did, unreason

ably disturb and alarm the public (R. Garner 37).

This, again, is segregation by state power simpliciter,

with only a change of name.

In the Briscoe case (No. 27), based on events occurring

in the Greyhound Bus Station in Baton Rouge, the waitress

who dealt with petitioners repeatedly testified, when not

led, that what she told petitioners was that they would not

be served unless they went over to the other side. On direct:

Q. All right. Tell the judge what happened. A.

They came in there and they sit down on the front

seven seats and they start ordering and I told them

they would have to go to the other side to be served,

[fol. 39] Q. Why did you tell them that! A. Because

we are supposed to refuse the service of anyone that is

not supposed to be on that side (R. Briscoe 30).

This account of what she said is twice repeated (R. Bris

coe 31, 33).

It is true that, in response to leading questions, this wit

ness adopted, by short affirmative answers, a different mode

of describing this same conversation, the tenor of which she

had already given in her own words. On direct:

Q. And you told them you couldn’t serve them and

asked them to move, is that correct? A. Yes, sir.

16

[fol. 40] Q. And when they refused to move yon

called the officers? A. Yes, sir (R. Briscoe 31).

And on cross:

Q. Miss Fletcher, is that the only reason you asked

them to leave is because they were Negroes? A. Yes,

sir (R. Briscoe 31).

But it is evident that she is referring to the same utter

ance, which she thrice describes in her own words as a

statement to petitioners that “they would have to go to the

other side to be served.” This is not an order to leave, or

indeed to do anything.

When Captain Weiner enters, the true nature of the com

plaint against these petitioners comes clear. Succinctly:

By Counselor Jones:

Q. You requested them to move then because they

were colored, is that right, sitting in those seats? A.

We requested them to move because they were disturb

ing the peace.

Q. In what way were they disturbing the peace?

A. By the mere presence of their being there (R. Bris

coe 38). (Emphasis supplied.)

In this case, the trial court., in its “Finding”, predicated

guilt both upon the waitress’ “request” that the petitioners

“leave” (cf. the analysis of her testimony, above) and the

police request of the same tenor. These ingredients are

intermixed in indeterminable proportions. This Court may

independently evaluate the waitress’ testimony as support

for the trial court’s finding of a “request” on her part.

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587, Napue v. Illinois, 360

U. S. 264, 272. But even if such a “request” be granted, and

given the force of an order, it remains unquestionable that,

17

on the trial court’s own statement, an ingredient1 in the

guilt of these petitioners was their sitting at a “white”

counter after the agents of the State had determined that

they were not to sit at the “white” counter—pure segrega

tion by state power.

The record shows no consequential relation between the

waitress’ “request to leave” (if that was ever given), and

the parallel request on the part of the police. Captain

"Weiner testified:

Q. Officer, you testified that they were seated at this

cafe counter seat in the section or the side that was

reserved for white, is that correct? A. That’s right.

Q. Now, how did you know that this particular side

in which they were sitting was reserved for whites?

A. Well, it is pretty obvious from the people there.

# # * # #

Q. Why did you arrest them, officer? A. Because

according to the law, in my opinion, they were disturb

ing the peace.

# # # # *

Q. What was your answer to that officer? A. That

in my opinion they were disturbing the peace.

Q. Within your opinion. Explain your opinion. A.

The fact that their presence was there in the section

one of the grounds for conviction is invalid under the

Federal Constitution, the conviction cannot be sustained.” Wil

liams v. North Carolina, 317 U. S. 287, 292. Stromberg v. California,

283 U. S. 359, 370. The trier of fact in the present case had to make

a whole judgment—whether the conduct of petitioners in all its

bearing and under all the circumstances, met the very general

standards of §14:103(7). His findings tell us that he took into

account their failure to leave when ordered by the police, pure

state agents. We know from the companion cases, where this is the

whole of the basis for conviction, that this was a significant and

highly material factor. It is mixed in this ease in indeterminable

proportions with the other factor referred to—failure to obey the

waitress’ supposed “request”—and affects the whole conviction.

18

reserved for white people, I felt that they were dis

turbing the peace of the community (R. Briscoe 36).

This testimony makes it entirely clear that the police,

in enforcing segregation in this case, were acting on their

own responsibility and judgment as public agents of the

state within the scope of their authority.

In these three cases, then, we have to do with the enforce

ment of segregation as a state policy having the force of

law, by agents of the state. As petitioner will later show

more at large (Point B, infra) there is not the ghost of evi

dence, in any of these cases, of any breach of the peace, or

any threat of disturbance, other than such as might be in

ferred from the mere fact that petitioners were not observ

ing the custom of segregation. Even if the records con

tained such a showing, it would be of no avail, for the out

lawing of segregation by the Fourteenth Amendment is of

course a rejection of all the reasons why segregation might

be thought good, including the fear of disorder. Buchanan

v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1. But

there is nothing of that tenor to consider. These petitioners,

in everything but name, were convicted of the simple offense

of not following the custom of segregation, and their con

victions cannot be sustained without sustaining segregation

by the direct force of state law and authority.

(2) E ven if i t b e u rg e d th a t th e re is in th ese cases a

re le v a n t co m p o n en t o f fo rm a lly “ p riv a te ” ac tion ,

th a t a c tio n is su b stan tia lly in fec ted w ith sta te

pow er. “ P riv a te ” seg reg a tio n in these cases was

in o bed ience to a sta tew ide custom , w hich in tu r n

h as lo n g en jo y ed th e s u p p o r t o f L ou is ian a as

a po lity .

In the preceding Point, A (l), petitioners have urged

that these cases on their own records present no novel ques

tions of “state action”, since the enforcement of obedience

19

to the custom of segregation was the work throughout of

formal agencies of the state. It is true, however, that a

formally “private” pattern of segregation is in the back

ground of each case, even though, as shown above, no right

of private property was distinctly asserted or claimed, and

the connection between the “private” pattern and the inde

pendent police and judicial action remains vague.

If it be thought that this vague connection between the

action of private proprietors and the actions of the State

suffices to put in issue the question whether these “private”

patterns of segregation were themselves infected with state

power, then petitioners contend that that question must be

answered in the affirmative.

To begin, the “property” interest of these proprietors

was an exceedingly narrow one. In each case, petitioners

were not only “invited” but welcomed as cash customers on

the premises, everywhere but at the lunch counters. The

“property” right at stake was simply the right to segregate.

These establishments—a busy drug store, a large depart

ment store, a bus terminal restaurant—are a part of the

public life of Baton Rouge. The subjection of their policies

to constitutional control raises no real issues of individual

privacy or freedom of association. Munn v. Illinois, 94

U. S. 113; Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501.

It is against this background that the “state action” ques

tion here must be set. And it ought further to be noted that

the “state action” doctrine has proven far from satisfactory

as a guide among the pervasive realities of state power

intermixed in nominally “private” activities widely affecting

public life. The basic trouble is adumbrated in the Civil

Bights Cases opinion itself, where it is laid down that

“some” state action is enough, 109 U. S. 3, 13; since total

absence of state involvement rarely if every occurs in mat

ters of public importance, the “state action” doctrine was

20

from its inception certain to create vast problems. It is

far from clear, moreover, that “state” action must always

be “political” action; “custom” is mentioned in the Civil

Bights opinion as one of the forms of state action, 109 II. S.

17, and it may be that this rests on a conception of the

“State” as a community, acting through firm customs as

well as by formal law. Even verbally, “state action” may

not be a validly inferred requirement in equal protection

cases, for denial of protection can be accomplished by inac

tion as well as by action, and in many cases the proper

question may be not whether the state has “acted”, but

whether it has failed to act when it should have done so.

The late Judge Learned Hand, writing on a question of

constitutional construction, said that “ . . . for centuries

it has been an accepted canon in interpretation of documents

to interpolate into the text such provisions, though not ex

pressed, as are essential to prevent the defeat of the venture

at hand . . . ” Hand, The Bill of Rights, p. 14. Where for

mally ‘“private” actions would defeat the constitutional ob

jectives of equality and freedom in the public life, this

principle surely has some applicability. Cf. Terry v. Adams,

345 U. S. 461.

But in these cases the State of Louisiana is so intimately

involved, even in the formally “private” segregation pat

tern followed by these proprietors, that we need not reach

these ultimate problems.

The intervention of police in support of the segregation

pattern, and the invocation of the criminal prosecution ma

chinery, are the immediate and obvious state involvements.

“Whether the statute book of the State actually laid down

any such rule . . ., the State, through its officers, enforced

such a rule; . . . ” Civil Rights Cases, supra, 109 U. S. at

15. But the deeper involvement of Louisiana arises from

two facts: (1) These proprietors, in segregating, were not

21

acting on whim, or in obedience to personal taste as to

association, but were following a custom that characterizes

Louisiana as a community; (2) the maintenance of this

custom, by law and other official action, is the policy of

Louisiana as a political body.

The only rational or imaginable ground for the “private”

segregation followed by these proprietors was obedience to

state custom. Though this background fact is assumed

rather than explicitly stated in testimony, its presence in

the background can be inferred from these records, if such

support be thought necessary in regard to a matter of

such common knowledge. In Hoston, Kress, a nationwide

chain which as a matter of common knowledge does not

segregate outside the South, is found segregating; the man

ager testified that he feared a disturbance if petitioners sat

in the white section, “Because it isn’t customary for the

two races to sit together and eat together” (R. Hoston 30).

In Garner, the owner testified that he could not serve

Negroes because he had “facilities for only the one race”—

a statement which makes sense only against the background

of the assumption that Negroes and whites are by custom

not to be served together (R. Garner 30, 31). In Briscoe,

we have to do with the terminal of a national bus company;

the facilities of such an enterprise are, as a matter of com

mon knowledge, segregated only in states where such

segregation is customary. The interventions of the police

in these cases were obviously based on their knowledge of

the customary character of this segregation. There is not a

scintilla of evidence to rebut the inference that the segre

gation practiced by these proprietors was a direct conse

quence, and indeed a part, of the Louisiana custom of public

segregation of the races.

The State of Louisiana as a community was thus in

dispensably involved in this segregation pattern. But Lou

22

isiana as a polity is in the same causal chain of involvement,

for the State has given to the segregation custom the full

support of state law and policy.

There is even good historic ground for the belief that the

segregation system, of which the segregation followed as a

“custom” in these eases is a part, was brought into being, or

at least given firm lines in its inception, by state law.

Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow, Oxford Uni

versity Press (1957) 15-25, 81-87, “ . . . [Sjtateways,

apparently changed the folkways,” id. at 92.

Louisiana has long maintained a system of segregation

by law. A joint resolution of the legislature in 1960 has

recently restated the official policy of the state.

“W hereas, Louisiana has always maintained a policy

of segregation of the races, and w hereas, it is the inten

tion of the citizens of this sovereign state that such a

policy be continued.” Acts 1960, No. 630.

In his inaugural address the present Governor succinctly

stated the policy of the State: “We will maintain segrega

tion.” New Orleans Times-Pieayune, May 11, 1960, p. 2,

Sec. 3, col. 1-7.

It is true that Louisiana’s segregation laws, as such, are

no longer enforceable de jure. In view of the utterances

just quoted, the importance of this fact is hard to evaluate.

But in any case it could not break the casual nexus between

state support of the custom of segregation and the preva

lence of that custom. Effects outlive their causes, but do

not thereby cease to be effects of those causes.

Louisiana has a law, passed in 1956, making it a crime to

permit mixed white and Negro dancing, social functions,

entertainments, “and other such activities involving per

sonal and social contacts” (LSA-E.S. 4:451, Acts 1956,

23

No. 579). It is uncertain whether the quoted phrase makes

it generally unlawful for whites and Negroes to eat to

gether ; certainly it would seem to make it unlawful for them

to eat together under many circumstances. But this point

need not be resolved. For segregation is a system rather

than a series of isolated provisions. And a State which

enacts that whites and Negroes may not eat together on the

job or use the same sanitary facilities (LSA-R.S. 23:971-

972), go to prison together (LSA-B.S, 15:752), buy a ticket

at the same window ■ (LSA-B.S. 4:5), wait in a station to

gether (LSA-R.S. 45:1301-1305), go to a public park or

other public recreational facility together (LSA-R.S. 33:

4558:1), marry one another (LSA-R.S. 14:79) or even

advocate integration, if they are employed in the school

system (LSA-R.S. 17:493, 17:523, 17:443, 17:462)—is at

least making it vastly more likely that the general custom

of segregation will be observed. (The foregoing sampling

is of laws currently in force, save as to constitutionality;

of course Louisiana has until recently had and enforced

segregation laws as to transportation, etc., and the causal

effect of these in creating and supporting the interconnected

segregation system seems clear, as brought out above.)

The formally “private” segregation practiced in these

cases is therefore unbreakably connected with state law, for

it is the creature of state custom, and the support of that

custom is itself the keystone policy of Louisiana as a polit

ical entity. This course of action is not only touched by but

permeated with the power of the state.

If the element of “private” choice be thought material on

these records, petitioners insist that the quantum and kind

of genuine “private” choice in this pattern is negligible, a

mere bridge from statewide custom, fostered by state law

and policy, into the state criminal machinery. No private

interest of these proprietors is at stake, other than the gain

24

they may look to from following the state-fostered segre

gation custom. On any view, “state action” permeates the

whole pattern. A contrary holding would turn upside down

the criterion of the Civil Bights Cases, for it would have

to rest on the proposition that action is “private” unless it

is wholly public—that any small component of nominally

“private” choice robs a public pattern of its public char

acter.

B. Petitioners’ convictions denied due process o f law,

in that they rested on no evidence o f an essential ele

m ent o f the crime.

Louisiana Bevised Statutes 14:103, under which peti

tioners were convicted, reads, in relevant part :

“disturbing the peace is the doing of any of the follow

ing in such a manner as would foreseeably disturb or

alarm the public:

^

(7) Commission of any other act in such a manner as

to unreasonably disturb or alarm the public.”

(Petitioners’ conviction was had under subsection (7),

evidently the only one which could conceivably apply to

them.)

In each case, the information contained substantially the

following allegation:

“ . . . said conduct being in such a manner as to unrea

sonably and foreseeably disturb the public. . . . ”

In each of the cases, the “Finding of Guilt” contains

a recital corresponding (roughly, and with variations, see

infra p. 26) to these allegations.

25

Thus the State of Louisiana formally recognized at every

crucial stage that (as indeed is patent as the statute’s face)

a conviction can be had under the statute only on a find

ing and a showing that the conduct complained of was

performed, in the words of the informations, “in such man

ner as to unreasonably and foreseeably disturb the public.”

There is no evidence in any of the records that this

conduct bore any such character. There is much in these

records, on the other hand, that tends strongly to rebut

the hypothesis.

In the Garner case, the owner of the store had received

no complaints, and did not summon the police (R. Garner

33, 31). The police witness, Captain Weiner, when asked

the general question “Tell the Court exactly what was

done?” described a scene of profound peace. He knew of

no complaints (R. Garner 34). The rest of his testimony

contains no hint of an actual, threatened, or even antici

pated breach of the peace. Yet he was being examined on

direct by a prosecutor whose duty it was to show through

this experienced witness, if he could, that this indispensable

element of the crime was present. On cross the questions

of counsel repeatedly sought, and never received, some

thing other than the “mere presence” of these Negroes as

a ground for the arrest.

In Briscoe, again, the waitress’ testimony contains no

hint of anything other than an occasion profoundly peace

ful in its surrounding circumstances. She gave no evidence

of so much as grumbling on the part of anyone. Her re

fusal to serve petitioners was based solely on their race

in itself (R. Briscoe 32). Captain Weiner, again (though

with every reason to allude to circumstances of disorder or

threatened disorder if they were present) describes a peace

ful scene, and gives “the mere presence of their being

26

there” as the sole factor constituting a breach of the peace

(R. Briscoe 38).

In Boston, the situation described in the testimony is

one containing no elements of present or threatened dis

turbance. The manager, it is true, “feared” a disturbance,

but he “feared” it, as he testified, solely because “it isn’t

customary for the two races to sit together and eat to

gether” (R. Hoston 30). The imminence in his mind of

what he “feared” may be assessed by his distinct testi

mony that he did not even ask the petitioners to move

(id at 34). Weiner’s testimony, again, distinctly negates

any factor of disturbance of the peace, other than “their

mere sitting there” (id at 37).

It is on this evidence, and nothing else, that the trial

judge made the findings, indispensable under the statute,

that “the conduct of the defendants on this occasion at

that time and place was an act done in a manner calculated

to, and actually did, unreasonably disturb and alarm the

public” (R. Garner 37, emphasis added), that “their actions

in that regard in the opinion of the Court was an act on

their part as would unreasonably disturb and alarm the

public” (R. Briscoe 39), that the same conduct “was an

act which foreseeably could alarm and disturb the pub

lic. . . . ” (R. Hoston 39, emphasis added). These findings,

essential to conviction under the statute, are unsupported

by evidence, and a conviction without evidence of guilt is

the most elementary possible denial of due process. Thomp

son v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199.

Since the trial court jumped this gap merely by using

conclusory language, and since the State Supreme Court’s

brief opinion sheds no light on the problem, it is hard to

make out on what theory the state courts considered that

petitioners could be convicted on testimony so palpably not

containing evidence of an essential element of guilt. The

27

only reasoned utterance of any organ of the State of Louisi

ana on this question is found in the State’s Brief in Opposi

tion to Petition for Writ of Certiorari, filed in this ease.

On pp. 11-13 of that document the thought is developed

that petitioners, having access to newspapers and having

lived in Baton Rouge, should have known that their actions

were likely to produce trouble, and that they were not

welcome.

The first of these points goes pretty far. It amounts,

for the purposes of these cases, to an assertion that the

formation of mobs to attack peacefully protesting Negroes

is so expectable a phenomenon in Louisiana that the trial

judge, absent any support in the record, must be assumed

to have taken judicial notice, svib silentio, not only of the

likelihood of such trouble but also of the petitioners’ knowl

edge of that likelihood. In the absence of any assertion

to this effect by any court in Louisiana, it would be going

pretty far for this Court to supply the clear defect of these

records by an assumption so gratuitously insulting to the

people of Louisiana. Disturbances there have been, in Lou

isiana as elsewhere, but nothing has yet happened to make

it suitable for this Court to assume a position so hopeless.

But even if this assumption be made, the sole upshot,

in application to the facts of these cases, is that public

protest may be anticipated where Negroes sit with whites,

and that fear is not on any view a sufficient ground for

state support of segregation. Buchanan v. Warley, 245

U. S. 60; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1.

As to petitioners’ imputed knowledge, suggested by the

Brief in Opposition, that they were “not welcome”, it is to

be observed, first, that this falls far short of proving a

threat to the peace, or a public disturbance or alarm. More

fundamentally, this argument ignores the essence of the

sit-in demonstration, which is addressed to the conscience

2 8

and to the self-interest of the proprietor. Petitioners may

have guessed or known they were “not welcome”, in the

sense that the proprietors of these stores would rather

the whole thing had never come up; but the whole point of

the demonstrations was that petitioners wanted to try

whether, by solemn protest, they could gain the “welcome”

—in the cash-nexus sense in which that word may meaning

fully here be used—to which they believed themselves mor

ally entitled. Again, the austere utterances of the state

courts give no guidance; it is asking a great deal of this

Court to ask it to supply the deficiency of these records

by guesses as to the degree of “unwelcome” felt by these

proprietors, and the connection of that, in turn, with a fore

seeable tendency of petitioners’ actions unreasonably to

“disturb and alarm” the public.

These are speculations, justified only by the correspond

ing speculations in the Brief in Opposition. The hard fact

remains that these records are fatally defective as a matter

of the simplest due process, for they contain no evidence

of an essential element of the crime charged. Thompson v.

Louisville, supra.

C. Petitioners were convicted o f a crime under the

provisions o f a state statute which, as applied to their

acts, is so vague, indefinite, and uncertain as to offend

the due process clause o f the Fourteenth Amendment.

The requirement of civilized law with respect to clarity

of the commands in criminal statutes has never been better

stated than by the Louisiana Supreme Court:

“ . . . it is well-settled that no act or conduct, however

reprehensible, is a crime in Louisiana, unless it is

defined and made a crime clearly and unmistakably

by statute.” State v. Sanford, 203 La. 961, 970, 14 So.

2d 778, 781 (1943).

29

This requirement, as a minimum component in our con

cepts of ordered liberty, Palko v. Conn., 302 U. S. 319, 325,

is an indispensable ingredient of due process of law under

the Fourteenth Amendment. Lametta v. New Jersey, 306

U. S. 451.

On its face and as applied, this statute entirely fails to

meet this test. To begin with, all seven of the categories

of offenses proscribed are subject, by the introductory

clause, to the overriding requirement that the act be done

“in such a manner as would foreseeably disturb or alarm

the public.” Presumably this language embodies some lim

itation ; not every “fisticuff”, not every “interruption of any

lawful assembly of people,” is an offense, but only such as is

“done” in the proscribed “manner.” But what is the scope

and tenor of this limitation? Does the introductory lan

guage refer (as it seems to, in the use of the phrase “in

such a manner”) to some aggravated characteristic of the

act itself? Or does it refer (as seems more natural where

“foreseeability” is at stake) to the surrounding circum

stances?

“Foreseeability”, moreover, is in criminal law and in the

law of private obligations usually a criterion of responsi

bility for what actually takes place; to speak of the “fore

seeability” of what never happened is at the least a bit

unusual. Does this language, then, limit criminal respon

sibility to the case where the public disturbance and alarm

actually take place, and where these might have been “fore

seen”? That is the construction suggested by the phrase

being defined, “disturbing the peace”, for the conclusion

goes down hard that “disturbing the peace” can be found

to have occurred when the peace is not actually disturbed.

Yet the mind remains unsatisfied that this limited construc

tion was (or was not) the one in the legislative mind.

30

When we get to the very subsection under which these

petitioners were charged, a puzzling partial redundancy

occurs. The requirement of a connection with public dis

turbance and alarm is reiterated, though under a different

verbal form. The act proscribed by (7) must be committed

“in such a manner as to unreasonably disturb or alarm the

public.” Does this “as to” look toward actual result or does

it refer to tendency? Both usages are normal English.

The requirement of foreseeability moreover, dropped out

in the special definition of (7), though it doubtless still rides

through from the introductory phrase. Does this mean that

the actual consequence of public disturbance must be pres

ent under (7), while foreseeable tendency to disturbance is

enough, say, to bring a “fisticuff” under the statutory ban?

Finally, is the rule eiusdem generis applicable to (7) ?

The other actions prohibited by (l)-(6) are all to some

degree disorderly or blameworthy in themselves. Does this

limitation subsist as to (7)? Or does the subsection really

penalize “any other act” if its further vague criteria are

met? (Subsection (4) of this same section penalizes “three

or more persons” for any “act” done in a “violent and tumul

tuous manner” ; is it reasonable to suppose that subsection

(7) was meant to penalize acts by any number of persons

done in a non-violent manner ?)

These multifarious indeterminacies, impossible of reso

lution save by fiat, function in series with the almost total

vagueness of each word in the phrase “unreasonably dis

turb or alarm the public.”

The Louisiana Criminal Code contains directions for its

own interpretation, but these help very little, or even tend

to establish that the application of §14:103(7) to petitioners

would contravene the canons of construction ordained. For

example:

31

LSA-A.R. 14:3—Interpretation of Criminal Code.

“ . . . all of its provisions shall be given a genuine

construction, according to the fair import of their

words, taken in their usual sense, in connection with

the context, and with reference to the purpose of the

provision.”

The “context” in which §14:103(7) occurs is mainly or

entirely one of violence or indecency in the proscribed ac

tion itself, a characteristic entirely missing in these cases.

In LSA-R.S. 14:8, it is enacted that:

Criminal conduct consists of an act or failure to act

which produces criminal consequences.

This would tend to suggest that the actual ensuing of dis

turbance is a defining character of an offense under §14:103

(7). The main thrust of these passages, however, is their

confirming of the vagueness of §14:103(7).

The Louisiana Legislature must have been doubtful

whether §14:103(7) could apply to peaceful sit-ins, for

an elaborate new §14:103.1, added by Acts 1960, No. 69,

§1, provides, among other things that:

“A. Whoever wfith intent to provoke a breach of the

peace, or under circumstances such that a breach of

the peace may be occasioned thereby:

. . . (4) refuses to leave the premises of another when

requested so to do by any owner, lessee or any em

ployee thereof, shall be guilty of disturbing the peace.

And Act 1960, No. 77, amending LSA-R.S. 14:56, added

to the categories of “criminal mischief” a new one:

32

“(6) Taking temporary possession of any part or parts

of a place of business, or remaining in a place of

business after the person in charge of such business

or portion of such business has ordered such person

to leave the premises and to desist from the temporary

possession of any part or parts of such business.”

As petitioners have already shown, even these new sec

tions would not apply to them because they were not

ordered to leave. (Supra, Point A (l), passim). But the

fact that the legislature conceived it necessary to spell out

even this more concrete offense in new legislation makes

it most unlikely that any clear command was thought to he

embodied in §14:103(7), forbidding the less definite offense

of simply being where Negroes are not “supposed” to be.

The introductory part of the new §14:103.1, quoted above,

also shows a contrast with the attempted definitions in

§14:103(7) “Intent to provoke a breach of the peace”, and

“circumstances such that a breach of the peace may be

occasioned thereby”, are far from precise in their reference.

But at least it is made clear that either the state of mind

of the actor or the potentialities in the situation are being

referred to. By contrast, in our §14:103(7), as is shown

above, it is impossible even to be sure what the field of

reference is.

Prior Louisiana statutes and decisional law are not help

ful. The leading case under a prior act roughly similar

to §14:103 was State v. Sanford, 203 La. 961, 14 So. 2d 778

(1943). Defendants, Jehovah’s Witnesses were convicted

under the phrase “ . . . who shall do any other act, in a

manner calculated to disturb or alarm the inhabitants . . .

or persons present. . . ” Acts 1934 No. 227, §1. Their “act”

was being in town and handing out magazines after city

officials had warned them that their “presence” might cause

33

trouble. Beversing the convictions, the Supreme Court of

Louisiana said:

“ . . . the defendants went about their religious mission

ary and evangelistic work in an orderly, peaceful and

quiet way and did not demand or insist that the per

sons approached either listen to them or make a con

tribution. Briefly, their acts and conduct were lawful

and orderly and did not tend to cause a disturbance

of the peace. The Mayor and the Chief of Police had

no legal right to insist that these defendants forego

either their religious beliefs and works, or remain away

from the town, as long as they conducted themselves

in a lawful and orderly manner. . . . ” 203 La. 961,

967,14 So. 2d 778, 780.

This language seems to make the orderly character of the

defendants’, own actions a defining characteristic of non

culpability. In Town of Ponchatoula v. Bates, 173 La. 824,

at 827-828, 138 So. 851 at 852 (1931), the same court up

holding as against a vagueness claim a town ordinance

making it a crime to “engage in a fight or in any manner

disturb the Peace,” said:

“It was not necessary that the ordinance define the

offense for the reason that no better definition for

the offense could be found than that contained in the

ordinance itself. To disturb means to agitate, to

arouse from a state of repose, to molest, to interrupt,

to hinder, to disquiet. . . . A disturbance of the peace

may be created by any act or conduct of a person which

molests the inhabitants in the enjoyment of that peace

and quiet to which they are entitled, or which throws

into confusion things settled, or which causes excite

ment, unrest, disquietude, or fear among persons of

ordinary, normal temperament. Such acts to come

34

within the purview of the ordinance must be voluntary,

unnecessary, and outside or beyond the ordinary course

of human conduct.”

Here the criterion of actual result is obviously in the

court’s mind.

In State v. Truby, 211 La. 178 at 184, 192, 29 So. 2d 758

at 759, 762 (1947) the same court, interpreting a “dis

orderly place” statute (LSA-R.S. §14:104) said:

“It is so well settled that citation of authority is

unnecessary that in Louisiana there are no common-

law crimes, and that nothing is a crime which is not

made so by statute . . . . [A] penal statute must be

strictly construed and cannot be extended to cases

not included within the clear import of its language,

and . . . nothing is a crime which is not clearly and

unmistakably made a crime.” (Emphasis added.)

Nothing in any of the above decisions has the slightest

tendency to bring the petitioners’ conduct “clearly and

unmistakably” under §14:103(7).

Section 14:103(7), then, is not a warning to the public.

It is not a guide to policemen or to courts. It says nothing

except perhaps “You’d better watch out,” or “Bad actions

are to be punished.” The legislature, in language impos

sible of rational construction, has simply furnished a

means of convicting those whom it seems desirable to

convict.

It is unnecessary to consider how much curative power

might have resided in a firm and intelligible judicial con

struction, channeling the sprawl of these words into per

missibly narrow grounds, for, as these cases illustrate,

confusion is worse confounded in the application of the

statute to petitioners. In its Findings of Guilt, the trial

35

court used three different formulae, one for each case,

though the problem was exactly the same in all. In Garner,

the act of the petitioners was said to be “an act done in

a manner calculated to, and actually did, unreasonably

disturb and alarm the public” (R. Garner 37). (These

references to manner and calculation, and to actual result,

are, of course, in the teeth of the evidence; see Point B,

supra.) In Briscoe, the very same conduct is said to be

“an act on their part as would unreasonably disturb or

alarm the public” (R. Briscoe 39). In Boston, it “was

an act which foreseeably could alarm and disturb the

public” (R. Hoston 39). It would be tedious and un

needful to subject these utterances to narrow verbal crit

icism; the least that can be said of them is that they

bring no clarity whatever to the total ambiguity and

vagueness of the statute.

The brief opinion of the Supreme Court of Louisiana

casts no light on any of these questions. The testimony

in these cases, as shown supra under Point B, has no ten

dency to connect these petitioners in any way to public

disturbance or alarm—wdiether by way of their intent,

or of their foreknowledge, or of actual result, or of prob

able I’esult. It remains entirely unclear, therefore, how

this statute could possibly apply to them.

It is impossible to imagine any statute more pressingly

calling for clarity than 14:103(7), for that subsection, on

its face, makes criminal any act performable by man, so

long as it meets the other tests of the subsection and of

the section as a whole. That these tests are not tests at

all, but merely a sort of automatic writing putting entire

discretion into the hands of the police, has already been

shown. This Court has never had under its hand a statute

more obnoxious to the due process requirement of definite

ness, nor one which reached further into the whole lives

of those subject to it.

36

D. The decision below conflicts with the Fourteenth

Amendment, in that it unwarrantedly penalized peti

tioners for the exercise o f their freedom o f expression.

There could be no serious doubt that petitioners, in

peacefully taking their places at the “white” counters, were

solemnly expressing their belief that they were morally

entitled to be treated on terms of full equality by the

establishments that solicited and enjoyed their patronage

at other counters. Such a non-verbal expression on a mat

ter of solemn moment is in every way equivalent to speech,

and is entitled to constitutional protection. Stromberg v.

California, 283 U. S. 359, Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S.

88. It is entirely immaterial at this point whether they

had a legal or constitutional right to enjoy unsegregated

service; what is at issue here is something quite different,

their right to indicate their conviction that in fairness

they should be served. Their expression wTas completely

peaceful, and was exactly adapted to time and place.

Nor is there, in these cases, any problem of the ac

commodation between private property rights and the right

to free expression, cf. Marsh v. Alabama, 326 IT. S. 501,

for these petitioners were not convicted, in name or in

substance, for trespass, but solely for being in a place

reserved by custom for whites. This has already been

conclusively shown, under Point A, su)pra.

We have to do then with a very clear suppression and

penalization of expression, by state authority. This fact

necessitates a reiteration of Point C, supra, in a context

which deeply intensifies its impact. The statute invoked

in this case is, as shown under Point C, supra, so vague

and uncertain as to offend against due process, when con

sidered simply as a criminal statute. When it is applied,

as here, to the suppression of constitutionally protected

utterance, its unacceptability is even more plain. It is,

37

in fact, in the field of free expression that this Court has

most vigorously applied the rule against vagueness. Smith

v. California, 361 U. S. 147, 151; Winters v. New York,

333 U. S. 507, 517-18; see Mr. Justice Frankfurter, con

curring in Burstyn v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495, 533.

No valid state interest appears in this case to over

balance the extremely weighty Fourteenth Amendment in

terest in personal freedom of expression. The state interest

in the preservation of the peace can have no application

to these records, for they fail to show, or even to hint,

that a breach of the peace was threatened. This has been

fully shown under Point B, supra. In this connection,

Femer v. New York, 340 U. S. 315, and Termimello v.

Chicago, 337 U. S. 1, may be adverted to, not for their

specific holdings, nor for selection among the divergent

views expressed in the opinions, but for exhibiting that

the debatable ground, on the present point, is miles away

from the terrain occupied by the cases here at bar. In

Feiner, there was some evidence at least of actual danger

of outbreak at the very time and place concerned. In

Terminiello, a situation fraught with imminent possibility

of violence was shown to exist. In both Feiner and Ter

miniello, moreover, the expressions themselves were in

trinsically provocative. In our cases, the whole situation

exhibited by these records is one of peaceful conduct on

petitioners’ part, and peaceful surroundings.

The only “breach of the peace” interest the State argu

ably had in these cases rested on the remote and in

ferential possibility, undeveloped in the records or in any

judicial utterance below, that somebody might later get

ungovernably upset at what petitioners were doing. To

sustain these convictions on such a ground would amount

to no less than holding that free utterance may be sup

pressed as a breach of the peace, if it can be guessed

that public disagreement with the utterance may be in

38

tense. This would be simply the abolition of the guarantee

of free expression in America.

The other assertable state interest implemented by these

convictions is the interest (abundantly evidenced in the

case of Louisiana) in the maintenance of segregation. But

this interest can have no constitutional standing, for it

takes effect only (as here) as a form of the use of state

power to support segregation.

In the aspect now under scrutiny, then, these cases con

stitute state suppression of expression, under a statute

maximally vague, and with no state interest appearing.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated, it is respectfully submitted

that the judgments o f the court below should be re

versed.

A. P . T ureaud

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana

J o h n n ie A. J ones

530 S. 13th Street

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

T hurgood M arshall

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Petitioners

C harles L. B lack , J r .

E lwood H. Chisolm

W illiam T. Colem an , J r.

J ames A. N abrit, III

Louis H . P ollak

Of Counsel