United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education Brief for Intervenors and Motion for Leave to File

Public Court Documents

April 22, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education Brief for Intervenors and Motion for Leave to File, 1966. 2f971f88-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/4ffb814f-0400-4500-9f8b-708ff9252880/united-states-v-jefferson-county-board-of-education-brief-for-intervenors-and-motion-for-leave-to-file. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

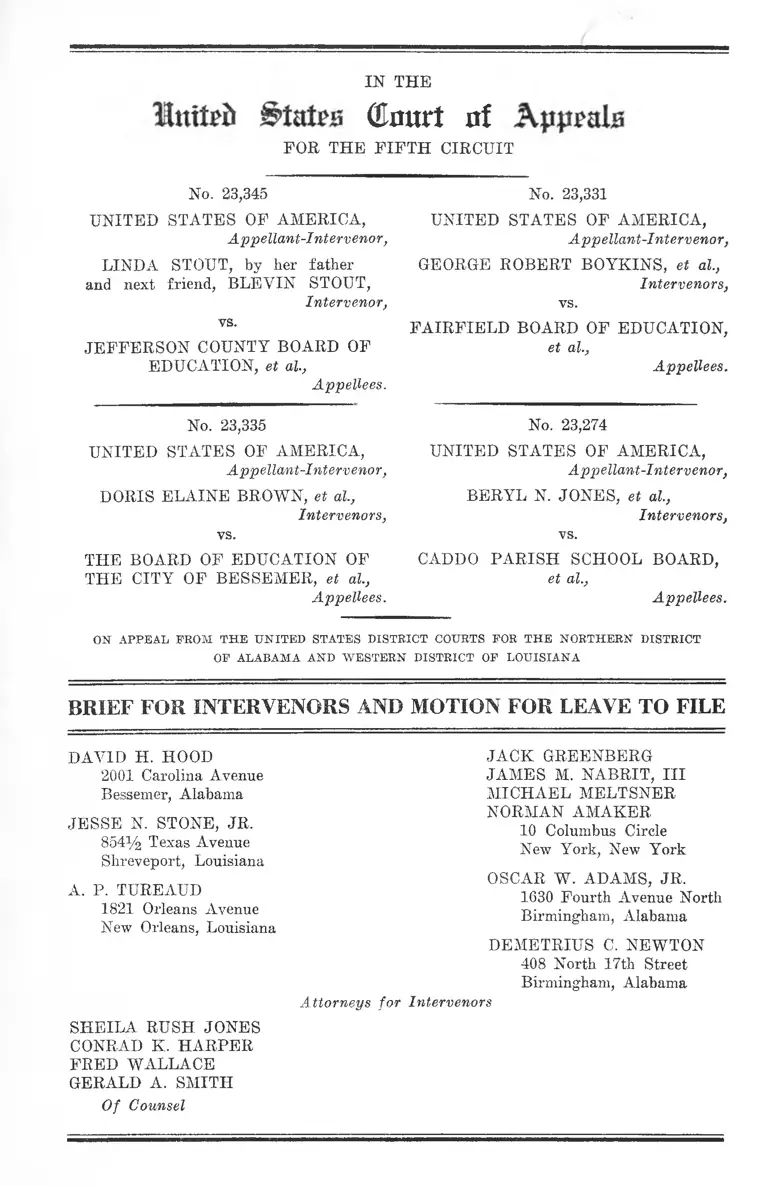

IN THE

Court at

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 23,345

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellant-Intervenor,

LINDA STOUT, by her father

and next friend, BLEVIN STOUT,

Intervenor,

vs.

JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD OF

EDUCATION, et al.,

Appellees.

No. 23,335

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellant-Intervenor f

DORIS ELAINE BROWN, et at,

Intervenors,

vs.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF

THE CITY OF BESSEMER, et at,

Appellees.

No. 23,331

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellant-Intervenor,

GEORGE ROBERT BOYKINS, et a t,

Intervenors,

vs.

FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION,

et al.,

Appellees.

No. 23,274

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellant-Intervenor,

BERYL N. JONES, et a t ,

Intervenors,

vs.

CADDO PARISH SCHOOL BOARD,

et at.

Appellees.

ON APPEAL PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURTS FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT

OP ALABAMA AND WESTERN DISTRICT OP LOUISIANA

BRIEF FOR INTERVENORS AND MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE

DAVID H. HOOD

2001 Carolina Avenue

Bessemer, Alabama

JESSE N. STONE, JR.

854% Texas Avenue

Shreveport, Louisiana

A. P. TUREAUD

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana

SHEILA RUSH JONES

CONRAD K. HARPER

FEED WALLACE

GERALD A. SMITH

Of Counsel

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

MICHAEL MELTSNER

NORMAN AMAKER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

OSCAR W. ADAMS, JR.

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

DEMETRIUS C. NEWTON

408 North 17th Street

Birmingham, Alabama

Attorneys for Intervenors

I N D E X

PAGE

Motion for Leave to File Interveners’ Brief or in the

Alternative to File Brief Amicus Curiae ............... . 1

Statement ........................................................................ 3

A. No. 23,345 Jefferson County Board of Educa

tion .................................-.................................... 3

The Original Desegregation P la n ........ ............ 4

The Amended Desegregation Plan ................... 5

General Transfer Procedure ............................. 5

Attendance Zones .............................................. 6

Teacher and Staff Segregation......................... 8

Unequal Negro Schools ................................... 9

B. No. 23,335 Board of Education of The City

of Bessemer ...................................................... 10

Summary of Litigation ............ 10

Summary of the Hearings ............... 13

Transfer Procedure Under the Plan ....... 14

Comparison of White and Negro Schools .... . 15

Faculty Desegregation ......... 18

C. No. 23,331 Fairfield Board of Education.......... 19

D. No. 23,274 Caddo Parish School Board .......... 25

Specification of Error ................... 29

l/

y

ii

PAGfi

A r g u m e n t

I. The Plans Approved by the District Courts

Fall Short of This Court’s Standards With

Regard Both to Pupil and Teacher Desegre

gation .............——-............................ ................ 30

II. The Inferiority of Negro Schools (1) Entitles

Negro Students to a Right of Immediate Trans

fer In All Grades and (2) Requires the School

Board to Devise a Plan Which Maximizes

Desegregation ............................. 45

C o n c lu sio n .................................................................... 48

Certificate of Service...................................................... 49

T able of C ases

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399 .................................. 42

Armstrong v. Board of Education of City of Birming

ham, 323 F.2d 333 (5th Cir. 1964) ........................ . 11

j Armstrong v. Board of Education, Birmingham, Ala.,

333 F.2d 47 (5th Cir. 1964) ...................................... 3

Beckett v. School Board of Norfolk, Civ. No. 2214

(E.D. Va.) ............................ 40

Boson V. Rippy, 285 P.2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960) ..... ..... . 37

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 382 U.S.

103 ........................................................................30,37,41

Brooks V. County School Board of Arlington, Vir

ginia, 324 F.2d 303 (4th Cir. 1963) ..... ...................... 37

Brown V. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ....25,45

Carr, et al. v. Montgomery Board of Education, Civ.

No. 2072-N (N.D. Ala. March 22, 1966) ..... .......... . 47

lU

PAGE

Dove V. Parham, 282 F.2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960) .......... 37

Dowell V. School Board of Oklahoma City Public

Schools, 244 F. Supp. 971 (W.D. Okla. 1965) .......38,44

Goss V. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683 ..................37, 42

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 377 U.S. 218 ......................................... ........ 37

Houston Independent School District v. Ross, 282 F.2d

95 (5th Cir. 1960) ..................................................... 37

Kemp V. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14 (8th Cir. 1965) .............. 44

Kier v. County School Board of Augusta County, Vir

ginia, 249 F. Supp. 239 (W.D. Va. 1966) ..............38, 44

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938) .. 45

Price V. Denison Independent School District Board

of Education, 348 F.2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1965) ....3,13, 30, 44 ^

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 ........ ........... ................... 45

Ross V. Dyer, 312 F.2d 191 (5th Cir. 1963) ............... . 37 '

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 355 F.2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966) .... .....30, 31, 32, 36, 37

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir. 1965) ..............3,13,35,44

Sipuel V. Board of Regents, 332 U.S. 631 (1948) ......... . 45

Sweat! v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) ......... .......... . 45

United States v. Bossier Parish School Board, 349

F.2d 1020 (5th Cir. 1965) ............... ........................ 28 1/

IV.

S ta tu tes

PAGE

Title VI, Civil Rights Act of 1964 ................................ 42

42 U.S.C. §2000h-2 ............................... .......................... 28

Rule 24, P.R. Civ. P ........................................................ 28

O t h e r A u t h o r it ie s

Opinion of Attorney General of California, 8 Race Rel.

L. Rep. 1303 (1963) ................................................ 39

Revised Statement of Policies for School Desegrega

tion Plans Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964

§§181.13 .................................................................. 42

181.13(b) .......................................... 38

181.13(d) ............................................................. 38

181.15 ....... 48

Statistical Summary of School Segregation-Desegre

gation in Southeim and Border States, 15th Revi

sion, December 1965 (Southern Education Report

ing Service) ........................................... 41

IN THE

Court of

FOE THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 23,345

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellant-Intervenor,

LINDA STOUT, by her father

and next friend, BLEVIN STOUT,

Intervenor,

vs.

JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD OF

EDUCATION, et ah,

Appellees.

No. 23,335

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellant-Intervenor,

DORIS ELAINE BROWN, et al,

Intervenors,

vs.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OP

THE CITY OP BESSEMER, et a l,

Appellees.

No. 23,331

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellant-Intervenor,

GEORGE ROBERT BOYKINS, et al.,

Intervenors,

vs.

FAIRFIELD BOARD OP EDUCATION,

et al..

Appellees.

No. 23,274

UNITED STATES OP AMERICA,

Appellant-Intervenor,

BERYL N. JONES, et al,

Intervenors,

vs.

CADDO PARISH SCHOOL BOARD,

et al..

Appellees.

ON APPEAL PEOM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURTS EOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT

OF ALABAMA AND WESTERN DISTRICT OP LOUISIANA

Motion for Leave to File Intervenors’ Brief or in

the Alternative to File Brief Amicus Curiae

April 8, 1966, Negro school children and parents, here

inafter referred to as intervenors, moved this Court for

leave to intervene as party-appellants in Stout, et al. v.

Jefferson County Board of Education, (No. 23,345); Brown,

et al. v. Board of Education of the City of Bessemer,

(No. 23,335); Boykins, et al. v. Fairfield Board of Educa-

tion, (No. 23,331); Jones, et al. v. Caddo Parish School

Board, (No. 23,274); on the ground that as original party-

plaintiffs in each of these actions they had failed, through

inadvertence, to file timely notice of appeal, but were

desirous of making their views known to the Court and

aiding the Court in adjudication of the serious constitu

tional questions involving their interests which are raised.

As of April 21, 1966, intervenors have not received

notice of action by the Court with respect to the motion

to intervene and have been informed by the Office of the

Clerk that action by the Court is unlikely before April 25,

1966, the date on which appellant’s (United States of

America) brief is due to be filed with the Court. In order

not to cause delay should the motion to intervene be

granted, intervenors adopt and incorporate their motion

to intervene herein, lodge copies of this brief with the

Clerk, and serve copies upon all counsel prior to learning

of the disposition of the motion to intervene. Should the

motion to intervene be denied, Negro school children and

their parents, original plaintiffs below, respectfully move

the Court to grant leave to file this brief amicus curiae.

Because of the presence of common questions of law

and fact, the attached brief combines intervenors’ argu

ments No. 23,345 (Jefferson); No. 23,335 (Bessemer);

No. 23,331 (Fairfield); No. 23,274 (Caddo).

Respectfully submitted,

M ic h a e l M e l t sn e b

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Attorney for Intervenors

BRIEF FOR INTERVENORS

Statement

A. No, 2 3 ,3 4 5 Jefferson County Board o f Education

On June 4, 1965, Linda Stout, by her father and next

friend Blevin Stout, filed a class action against the Jef

ferson County, Alabama, Board; of Education and Dr.

Kermit Johnson, Superintendent (E. 9), seeking deseg

regation of all schools under the appellees’ control. A

motion for preliminary injunction was also filed seeking

complete desegregation either by court order or by a

desegregation plan (E. 17-19). Appellees filed an answer

June 22, 1965 (R. 20) and a hearing was held the same

day (R. 77-149). On June 24, 1965 (R. 23-28), the district

court ordered appellees to file a desegregation plan parallel

ing the plan required by this Court in Armstrong v. Board

of Education, Birmingham, Ala., 333 F.2d 47 (5th Cir.

1964), not later than June 30, 1965. Appellees filed their

plan June 30, 1965 (R. 29-37) and objections were filed

July 9, 1965 (R. 38-40). On July 12, 1965, the United

States moved to intervene as a party. The motion was

granted by the district court, and the United States filed

objections to the plan (R. 41-45). The district court over

ruled all objections in an opinion filed July 23, 1965

(R. 52-53).

On August 17, 1965, this Court vacated and remanded

the district court’s judgment in the light of Singleton v.

Jachson Municipal Separate School District, 348 F.2d 729

(5th Cir. 1965), and Price v. Denison Independent School

District Board of Education, 348 F.2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1965)

(R. 56-57). On August 20, 1965, the government filed a

motion in the district court for an order in conformity

with this Court’s mandate (R. 58-59). Appellees filed an

amendment to their desegregation plan August 27, 1965

(E. 66-68) and on the same day the district court, over

ruling objections, required appellees to report on the ob

jections by December 31, 1965 (R. 70-71). The government

filed a notice of appeal from the August 27, 1965 order

of the district court on October 25, 1965 (R. 72). Appellees’

counsel filed a statement in the district court December 28,

1965, noting that without further court order, appellees

would not report on the objections to the plan because

of the pending appeal (R. 74-75).

The Jefferson County school system consists of 117

schools and about 18,000 Negro students and 45,000 whites.

The system serves all of the territory in Jefferson County

except the cities of Birmingham, Bessemer, Torrant,

Mountain Brook, and Fairfield (R. 80). Until the time

this suit was filed, no desegregation had taken place in

the school system. The superintendent testified that no

application for a transfer designed to effect desegregation

had ever been received by the board (R. 94-95), but he

later conceded that no notice had ever been given that

pupils could transfer in order to effect desegregation

(R. 143).

T he O riginal D esegregation Plan

Appellees’ original desegregation plan provided for

desegregation of first, ninth, eleventh, and twelfth grades

for the 1965-66 school year; second, third, eighth and tenth

grades for 1966-67; and fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh

grades for 1967-68. Desegregation of ninth, eleventh, and

twelfth grades in 1965-66 was to be accomplished by

processing of applications requesting transfer from a

segregated school to one where the transfer will result

in desegregation. All other students in the ninth, eleventh,

and twelfth grades were to remain in segregated schools.

As to first grade, parents were to take their child to the

segregated school in their vicinity on the first school day.

At that time, they were to apply for assignment of

the child to any school and appellees were thereafter to

rule on the applications. Students whose parents failed

to make such applications were to be enrolled in the school

to which they initially reported (R. 31-37). No provision

was made for admission of named plaintiff to a formerly

white school.

T he A m ended D esegregation P lan

Appellees filed August 27, 1965, an amended desegrega

tion plan following this Court’s vacating of the district

court’s judgment approving the original plan. The amended

plan simply included the seventh grade among those to

be desegregated, varied the notice requirements and the

times for filing applications, and explicitly provided that

students new to the school system could transfer to the

school of their choice in the desegregated grades (R. 66-68).

General T ransfer Procedure

The Jefferson County school system has no definite

attendance zones. In general students go to the nearest

school serving their race (R. 88, 90). As to transfers

between segregated schools, no particular time is set

(R. 93); of the total of 200 transfer requests filed, only

10 were rejected and of the 15 requests by Negroes, only

one was rejected (R. 208-10). Under the plan, and in

accordance to prior transfer procedure, the parents of

first graders must apply in person at the superintendent’s

6

office to request a transfer. Most transfers are subject

to the seventeen criteria similar to those found in the

Alabama Pupil Placement Law, e.g., morals and psycho

logical state of the child (R. 103-04).

A ttendance Zones

The superintendent testified that g'eographical zoning,

i.e., assignment of pupil to school nearest his home regard

less of race, has not been adopted because of its in

flexibility and the fact that it would mean more segrega

tion (R. 239-40, 244) in a system having no desegregation

prior to this action. The superintendent said that geo

graphic zoning would be “difficult to administer from the

standpoint of working with the public, having to satisfy

the parents” (R. 134). He also said g’eographic zoning

would make student assignment easier but that it would

not solve the problems of teacher load, building use (R.

177) and “forcing people to go to school where they prefer

not to go” (R. 187). The plan does not envisage assigning

white children to Negro schools (R. 174-75).

The superintendent was disputed regarding his con

clusions on geographic zoning by appellant’s expert. Dr.

Myron Lieberman, a professor at Rhode Island College.

Dr. Lieberman testified (R. 255-66) that the plan failed

to utilize schools properly, thus Negroes were bussed to

overcrowded Negro schools when there were much closer

white schools. ̂ In this respect, he found the plan wasteful.

Dr. Lieberman further testified that the plan was deficient

in not informing the public of which schools were and

which were not overcrowded. The plan neglected to in

clude the tenth grade where there is the greatest number

’ The superintendent testified that all students living over two miles

from their schools were bussed and that bus routes overlapped because of

segregated passengers (E, 123-24, 127).

of drop-outs in the school system. Other than community

opposition to desegregation, no justification was offered

in the plan for limiting the number of grades to be deseg

regated.

Dr. Lieberman observed that the criteria for transfers

seemed to be different from the criteria for initial assign

ment to a school; for such a dilference he saw no educa

tional justification. None of the 17 criteria similar to those

of the Alabama Pupil Placement Law would aid an edu

cational administrator in determining whether a student

should be allowed to transfer or should be assigned to a

particular school. The best criteria would be the proximity

of the pupil to the school. At best, appellees’ plan would

result, stated Dr. Lieberman, in token desegregation. No

educational justification existed for the requirement that

a pupil’s parents attempt to secure transfers in person.

Dr. Lieberman testified that Negro pupils attending

the following schools, lived, as shown by exhibits, maps

and enrollment figures, closer to white schools having the

capacity to absorb them; Sumpter, Johns, Agder, Mc-

Adory, Shannon, Alliance Elementary, North Collie, Do-

cena, Cahaha Heights, Eoebuek Plaza and Trafford Ele

mentary. Dr. Lieberman gave the following examples:

[T]he Negro Muscoda School, has a capacity of 231

and an enrollment of 311, which means it is 80 students

over capacity, according to figures given by the Board.

There are three white schools very close by, Bayview,

Docena and Mulga and Bayviev/ is 153 under capacity,

Docena 241 and Mulga White School 260 under.

The Brighton white elementary school is listed as

having a capacity of 330 students and enrollment of

64 . . . that means it had a capacity of 266 students.

In the general area, Wilkes School is listed as having

a capacity of 231 and enrollment of 137. In that area,

the Negro schools are all over capacity. Eavine has

a capacity of 198 and enrollment of 266. Brighton

has a capacity of 330 and enrollment is 543. Pipe

Shop has a capacity of 363 and an enrollment of 518.

Ketona High School and Springdale both are listed

as having the same capacity, 528. They are very

close, practically touching each other on the map . . .

The Negro school is shown to have an enrollment of

912, Ketona, and the other school which is supposed

to have the same capacity, has only 583 students.

Dr. Lieberman emphasized that in a geographical zone

system a more effective utilization of school buildings

and buses could be effected. Transfers are allowed for

legitimate reasons in such a system and that “no over

whelming reason” exists which would bar the adoption

of this type of plan in the Jefferson County School System.

T eacher and Staff Segregation

The superintendent revealed that he considered it dif

ficult for a teacher to teach children of different races

(R. 190). He believed that a Negro teacher would find

it more difficult to teach an all-white class than a white

teacher having an all-Negro class (E. 139; cf. R. 144-45,

147-48). This belief was based on problems arising from

the “traditions and practices of our people” (R. 144),

particularly the reaction of parents (R. 144-45). Ap

pellees’ plan does not mention faculty desegregation for

the system’s 2268 teachers, of whom 600 are Negroes

(R. 118). All Negro teachers have the requisite degrees

for teacher’s certificates but not all of the white teachers

are so qualified (R. 119-20). Negro and white supervisory

9

personnel not only have different jurisdictions, they also

are segregated from each other; thus white personnel

work at the central staff office and Negroes are in other

places (R. 122-23).

U nequal Negro Schools

The superintendent testified that although there is only

one vocational school for white boys, Negro high schools

have comparable vocational subjects not offered in white

schools (R. 146). The only high school not accredited by

the Southern Association is Negro Praco high which the

superintendent said had not applied for an accreditation

(R. 220). The Negro Rosedale school has grades 1-12;

white Shades Valley school has grades 10-12 (R. 221).

The two schools are about half a mile from each other.

Rosedale has five or six acres; Shades Valley has about

twenty acres. Shades Valley has an auditorium, a stadium

and a separate gymnasium; Rosedale lacks a stadium and

a gymnasium (221-22, 232)." Although the superintendent

could name five white schools having summer school ses

sions, he could not “recall” other schools having such ses

sions (R. 232). In Negro Docena Junior High School, there

are pot-bellied stoves rather than central heating and stu

dents must go a block away to use toilet facilities (R. 233-

34). Because of alleged “ground absorption”, Negro Gary-

Ensley Elementary School has outdoor toilet facilities

(R. 234). The superintendent could not recall a Negro

school which had a stadium with seats and lights. He stated

that Negroes have not wanted to play football at night

(R. 235). Most stadiums and lights, including an $80,000

stadium at white Berry High School, have been provided,

according to the superintendent, by citizen efforts (R. 235-

2 By way of contrast to the Eosedale-Shades Valley situation, the super

intendent testified that Negro Wenonah High School had facilities superior

to white Lipscomb Junior High School (E. 240-41).

10

36). He did state, however, that the school system gives

assistance to such efforts by grading the ground and fur

nishing the light fixtures (R. 236).

In an apjoendix to Intervening Plaintiff’s Exhibit No. 1,

the government showed that of the 79 white and 32 Negro

schools listed, 81.3% of the Negro schools and only 54.4%

of the white schools had a student enrollment above ca

pacity. This meant that 33.3% of the Negro students or

4,587 Negroes were enrolled in schools having over capacity

population, but that only 10.1% of the white students or

4,125 whites were enrolled in such schools. The govern

ment also showed that 45.6% of white schools but only

18.7% of the Negro school enrollments were under capacity

(R. 203).

B. No. 2 3 ,3 3 5 Board o f E ducation o f T he City o f B essem er

In May 1955, a petition requesting changes in the Bes

semer school board’s practice of assigning students to

schools on the basis of race was presented to the Board

(R. 110-111, 184). No action was taken by the Board to

desegregate the school system. On March 23, 1965, a sec

ond petition, signed by Bessemer Negro organizations,’* re

questing the desegregation of the system was presented to

the board. No answer had been received by the time the

complaint was filed (R. 15).

Sum m ary o f L itigation

On May 24, 1965, a complaint was filed by Negro parents

and pupils residing in Bessemer, against the school author

ities requesting relief against the school board’s policy of

8 Bessemer Branch of the N.A.A.C.P., Colored Masonic Lodge, Bessemer

Civil League, Bessemer Voters League, Bessemer Business Professional

Men and Women (R. 111).

11

maintaining a segregated school system. Plaintiffs specifi

cally requested, inter alia, to attend the schools closest to

their homes and to be relieved from transfer criteria not

required of white pupils seeking assignment or transfer

(E. 16-17). In the alternative, they requested a plan re

organizing the dual racial zones into single, nonracial,

geographic zones for all grades, with students assigned

to the schools closest to their residence (E. 17).

The answer admitted that the Bessemer school system

was segregated and that a petition requesting desegrega

tion had been filed. The board asserted there had been no

request by a Negro student for a transfer to a white school

(E. 28). On June 21, 1965, the motion of the United States

of America to intervene Avas granted (E. 20-21).

At a June 30, 1965 hearing on the request for injunctive

relief. Judge Seybourn Lynne stated he would require

prompt submission of a plan rather than grant the specific

relief requested (E. 90, 128-129). He further stated that

his order avouH meet the minimum standards set forth in

Armstrong v. Board of Education of City of Birmingham,

323 F.2d 333 (5th Cir., 1964) (E. 179). The order enjoined

defendants “from requiring segregation of the races at any

school under their supervision from and after such time as

may be necessary to make arrangements for admission of

children to such schools on a racially, non-discriminatory,

basis” (E. 41). The board was ordered to submit a plan

which would commence September, 1965 and eventually ap

ply to all grades and pupils newly entering the system

(E. 41-42).

The plan filed July 9, 1965 provided for the transfer to

a school attended by pupils of another race by pupils in

three grades—4th, 7th, and 10th. Negro children entering

the first grade were required to report to a Negro elemen-

12

tary school to register. After registering, the parents could

then apply for transfer to another school. The filan re

quired that transfer applications be filed by the parents at

the office of the Superintendent before August 13, 1965.

For the following year when the plan reached grades 2,

5, 8, and 11, applications were to be filed between May 1

and May 15 (B. 43-45). By the 1967-68 school year, students

in all grades would be eligible to apply for transfer. The

plan specifically provided for all other students to remain

in schools to which they were assigned (R. 45-46). All

applications were to be filed “in accordance with the regula

tions of the Board” (E. 45). Notice of the time for ap

plication to transfer was to be published once in a city

newspaper (R. 46).

Objections to defendants’ plan were filed on July 15, 1965,

and July 19, 1965, pointing out, inter alia: (a) failure to

provide for nonracial, initial assignment for students newly

entering the Bessemer school system, (b) failure to include

grade 12 to insure Negro students still in school would have

“some measure of desegregation before graduation”, (c)

absence of any provision abolishing dual racial zones, (d)

failure to provide for transfer by Negro students in order

to obtain a course not offered at a Negro school, (e) ab

sence of a provision for transfer by Negro students who

attend educationally inferior schools, (f) failure to provide

that if the number of students desiring transfers exceeded

a school’s capacity, assignment would be based on prox

imity to the school, and (g) failure to provide for the

desegregation of teachers and supervisory personnel. A

hearing on the objections to the plan was held on July 29,

1965 (E. 181). Subsequently, Judge Lynne overruled plain

tiffs’ objections and approved the plan after modifying it

to include grade 12 instead of grade 4 for the 1965-66 school

13

year and to require that the notice be published for three

days instead of one day (E. 64-67). On August 17, 1965, this

Court vacated the district court’s judgment and remanded

the case for further consideration in light of Singleton v.

Jackson Municipal Separate School District, 348 F.2d 729

(5th Cir., June 22, 1965) and Price v. Denison Independent

School District, 348 F.2d 1010 (5th Cir., July 2, 1965) (R.

68-72).

On August 27, 1965, the board filed an amended plan in

corporating modifications ordered by the district court, by

adding grade 4 to the three grades to be desegregated for

1965-66, and extending the deadline until September 1 for

4th graders desiring transfers. On the same day the court

approved the amended plan. Noting that objections deal

ing with initial assignments had merit the court required

the board to restudy the plan and report its conclusions be

fore December 31, 1965 (R. 86).

The United States filed notice of appeal on October 25,

1965 (E. 88).

Sum m ary o f the H earings

Although prior to filing a desegregation plan Bessemer

school assignments were based on attendance zones, the

school board submitted and the court approved a desegrega

tion plan which, according to Dr. Janies 0. Knuckles, the

superintendent, switched the Bessemer schools to a free

dom of choice system (R. 237-245). He testified that under

the new system:

All those who feel . . . that the programs are differ

ent . . . or better .. . will have an opportunity to request

transfer and/or assignment to another school. They

will not be bound to attend the school nearest to them

under the freedom of choice program (E. 245).

X4

Dr. Knuckles admitted that under the existing school at

tendance zone lines, which were in no way changed or abol

ished under the desegregation plan, white and Negro zones

overlapped with Negro students sometimes living closer to

white schools and vice-versa (E. 108-109). Dr. Knuckles

further testified that to maintain meaningful attendance

zones all that was required was a map of student residences

as of a particular date (E. 238-239). While it was more

burdensome to administer a freedom of choice system than

to redraw the attendance zones, he and the board were

willing to undertake the burden (E. 242-249).

In the past, however, school attendance zone lines have

been changed after the school semester started, even where

the change involved shifting students from one school to

another, transferring teachers, setting up makeshift class

rooms, and closing other classrooms (E. 242-244). To ac

complish this, the board simply decided what needed to be

done without a public hearing and attempted to enlist pub

lic acceptance of the change. Before he could change at

tendance zones to accomplish desegregation, however, Dr.

Knuckles stated he would have to consider whether the

school patrons would willingly accept such a change (E.

241).

T ransfer Procedure Under the Plan

At the June 30, 1965 hearing on the motion for injunctive

relief. Dr. Knuckles testified that no desegregation steps

had been taken except the adoption of a transfer form and

procedure (E. 153-155, 253-254). That procedure required

principals to refer any applicants whom they “questioned”

to the superintendent. The parents of any student thus

referred was required to apply in person at the superin

tendent’s office. The application form, which included space

15

for standard test scores, grades, and record of behavior

and citizenship, would be reviewed by both the superin

tendent and the board and assignments made in accordance

with the Pupil Placement Law (R. 253-254). Although Dr.

Knuckles stated that the new procedure and fonns would

apply to whites, it became clear at the hearing on objec

tions that they applied only when a Negro applied to attend

a white school, or a ŵ hite airplied to attend a Negro school

(R. 261).

The transfer procedures and policies for non-racial trans

fers remained unchanged. According to Dr. Knuckles,

under the regular transfer policy the board attempted to

accommodate the desires of parents provided no over

crowding resulted (R. 149). Dr. Knuckles stated transfers

were initiated by letters or phone calls, that there were no

fixed times to apply and no fixed criteria other than the

guidelines enumerated in the Pupil Placement Law (R.

107). Proximity to the school requested and the child’s

capacity to learn were considered but no tests were re

quired (R. 150-153). After one year of operation, 13 Negro

pupils attended former white schools under the plan. (See

affidavit attached to memorandum in support of motion to

consolidate and expedite Nos. 23,173; 23,192; 23,274; 23,-

331; 23,335; 23,345; and 23,365 filed by the United States

in this court Ajjril 4, 1966.)

C om parison o f W hite and Negro Schools

Although all Bessemer schools have been accredited by

the Alabama Department of Education, the only school ac

credited by the Southern Association is Bessemer High

School, the white high school (R. 161-163). Accreditation

by the Southern Association is based upon requirements

concerning libraries, materials, minimum equipment and

16

laboratory space, and in years past, according to Dr.

Knuckles, has entitled the graduate of such a high school

to automatic admittance to many colleges and universities

(R. 161).

Dr. Knuckles admitted that many more electives are of

fered at Bessemer High School than at the Negro high

schools, including Latin, Spanish, and Journalism (R. 167-

168, 227-229). Dr. Knuckles explained that such courses

were available as a result of community pressure and stu

dent demand (R. 166-167, 176). However, two Negro stu

dents stated that they and others had requested second

year French at Carver High School but it was not made

available (R. 229, 234). Another Negro student attending

Carver High School testified that he wanted to attend

Bessemer in order to take courses unavailable at the Negro

school (R. 223). The Carver students also testified that

they conducted very few experiments in chemistry and

physics (R. 227-228), with one student testifying that only

the students who purchased their own materials conducted

experiments (R. 235). The pupil-teacher ratio at Bessemer

High School was 19.08 while at Carver and Abrams, the

ratio was 25 plus. The Negro ratio includes vocational

teachers (R. 162-163). Only the white schools operated

on the 6-3-3 system with junior high schools bridging the

gap between elementary and secondary schools, although

the system improves educational opportunities (R. 145).

At the hearing on the objections to the plan, Mr. Wil

liam L. Stormer, of the United States Office of Education,

Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, an expert"

̂Mr, Stormer spent 2% years working with the Department of Health,

Education and Welfare evaluating and estimating the need for school

facilities throughoixt the nation. He received his Master’s Degree in 1954,

at the University of Wyoming. During 1957-58 he was associated with

Ohio State University Plant Division, and from 1959 until taking the job

17

in evaluating and estimating the need for school facilities

throughout the country, testified that all four white ele

mentary schools in Bessemer ranked higher than the four

Negro schools with one exception, and that both Negro

high schools were lower than the white high school. In

making his evaluation, Mr. Stormer considered school site,

building structure, classrooms, special instructional space,

and the general use of facilities. He testified that the

Negro Abrams School, the newest building housing Negro

students, showed signs of structural deterioration and was

questionably located. He also found Abrams science and

storage facilities questionable, and science classroom space

limited (R. 194-195).

Dr. Knuckles also admitted that railroad tracks bordered

five of the six Negro schools (E. 138) and that only Negro

students were taught in frame buildings (R. 115). On

the basis of photographs offered into evidence (R. 138),

he also testified that the auditorium at Abrams High

School is partitioned into 8 sections and used for classes.

The partitions go % of the way to the ceilings and lighting

is supplied by bare globes suspended from the ceiling.

He admitted that more adequate lighting was needed,

that paint was peeling “pretty badly” from the building,

and that the windows badly needed repair (R. 139-140).

A photograph showed rainstained cardboards in some of

the broken windows.

Other photographs showed the Carver High School site,

with two wooden frame buildings used for classrooms,

illuminated by single light bulbs hanging from drop-cords,

and heated by coal stoves located in each room. Although

with the United States, he was Director o£ School Plant Planning- and

Studies for the State Department of Education for West Virginia. He is

a member of the National Council of School Housing Construction (E.

188-190).

18

Dr. Knuckles testified that it was the janitor’s respon

sibility to refuel the stoves (E. 141, 142-143), Morris

Thomas, a Negro student attending Carver High School,

testified that the students fired the stoves (R. 219-221).

Another student stated that a classroom was partitioned

into two sections (R. 224). Dr. Knuckles admitted that

neither of the frame buildings on the Carver site provided

adequate classroom facilities. Carver also is immediately

adjacent to an automobile junk yard (R. 143).

Photographs of Dunbar, a Negro elementary school,

showed many broken windows and considerable broken

glass around the building (R. 136-137). Dr. Knuckles

stated that the School Board planned to remodel Dunbar

although the money was not yet available and there would

be no renovation by Pall 1965 (R. 137-138).

Faculty D esegregation

Dr. Knuckles testified that all Negro teachers in the

Bessemer school system met the minimum requirements of

the board but no steps had been taken to desegregate

teaching staff and other supervisory personnel because

of “community pressure” and “the desire on the part of

the teacher” (R. 120-123). Also, nothing had been done

to desegregate a system-wide monthly teachers general

meeting (R. 249-251).

The only Negro in a supervisory capacity other than

the principals of the Negro schools is Walter Branch,

Director of Educational Services for the four largest Ne

gro schools, who had held the position “only a few months”

as of the hearing on injunctive relief. Although the board

has a central office, Mr. Branch’s office is located at Abrams

High School, a Negro school. Dr. Knuckles testified that

no Negroes held clerical positions at the board’s central

office in Bessemer (R. 116-118).

19

C. No. 2 3 ,3 3 1 Fairfield Board o f Education

The board maintains nine public schools in the City

of Fairfield, Alabama which serviced a total school-age

population of 3,095 children during the 1964-65 school term

(Intervenor’s Exhibit No. 3). Of this number 2273 were

Negro and 1822 were white (Ibid). By long term policy

and practice, the board segregates Negro school children

from white school children through the use of dual school

attendance areas or zones.

The white schools in the City of Fairfield are organized

on a 6-3-3 plan i.e. the first six grades being contained

in one elementary school; the seventh, eighth, and ninth

grades being contained in a junior high school; and the

tenth, eleventh, and twelfth grades in a senior high school

(R. 87, 96, 189-190). The 6-3-3 system is thought to be

the most educationally sound school-organization plan by

the school authorities of the State of Alabama and the

City of Fairfield (R. 87, 96). The Negro schools are not

organized on a 6-3-3 plan (R. 87, 96, 189-190). The schools

serving Negro children are Englewood Elementary School

(grades 1-8); Robinson Elementary School (grades 1-6);

Interurban Heights Junior High School (grades 7 & 8);

and Industrial High School (grades 9-12). (Intervenor’s

Exhibit No. 3).

The teacher-pupil ratios for the 1964-65 school term at

the various schools were these:

Grades 1-6

Negro White

Robinson 34/Teaeher Forest Hills 26/Teacher

Englewood 25/Teacher Donald 26/Teacher

20

Grades 7-9

Interurban 35/Teacher Fairfield Junior High

28/Teacher

Grades 10-12

Industrial High 29/Teacher Fairfield 20/Teaeher

(Computed from Intervenor’s Exhibits No. 3)

The plant facilities provided for the Negro children are

greatly inferior to those provided for white students. The

buildings are in disrepair (R. 217-218, 207-210); the

lavatory facilities are unusable, in part, or otherwise of

inferior quality or condition (B. 108-109 and Defendant’s

Exhibits 7 & 8). The eating facilities are infested with

vermin (R. 164-167, 218) and there is little if any recrea

tional areas provided around the Negro schools while

each white school is provided with ample grounds (B. 91-

93, 97, 98, 210, 211, 212, 218). The per pupil values of

the plant facilities of the Fairfield School System are

these:

White Negro

Donald Elementary $ 753 Robinson Elementary $ 258

Forest Hills Englewood

Elementary 920 Elementary 492

Glen Oaks

Elementary 817

Fairfield Junior Interurban

High 699 Junior High 130

Fairfield High 2,476 Industrial High 1,525

(Computed from Defendant’s Exhibit No. 11)

21

Numerous courses which are offered to the white students

in the junior and senior high schools are not offered to

the Negro students in comparable grades in the various

Negro schools (R. 90, 131-132, 215, 201). Guidance coun

selors are provided for the white students at Fairfield

High School and none are provided for the Negro students

at Industrial High School. (Intervenor’s Exhibit No. 3).

In 1954 Negro parents petitioned the board to desegre

gate the schools (R. 125-127, 220-223). Again in May,

1965 Negro parents petitioned for desegregation (R. 125-

127, 220-223). The board did not respond to either peti

tion (R. 125-127, 220-223).

On July 21, 1965 Negro parents and school children

brought suit against the board asking for a preliminary

and permanent injunction against continuing segregation

of the schools and teaching staffs (R. 14-23). On July 30,

1965 the United States moved to intervene as a party

and requested that the Fairfield school system be deseg

regated (R. 24-29). On August 12, 1965 the board filed its

answer admitting that Negro children are assigned to

Negro schools and white children to white schools and

that extra-curricular activities of the school are segregated

by race (R. 30-33, see R. 31).

The cause came on for a hearing in the United States

District Court for the Northern District of Alabama, South

ern Division, on August 16, 1965 (R. 75). At that time, by

agreement of the parties, the motion of the United States

to intervene was accepted and the hearings were stipulated

to stand as basis for a permanent injunction (R. 76). The

district court found that there was an illegally segregated

system in Fairfield and ordered the board to submit a plan

during the two days next following August 16, 1965 (R. 84).

The court then adjourned the hearing to August 20, 1965

22

at which time the plan and objections to it could be con

sidered.

On August 17,1965, the board filed a Plan for Desegrega

tion of Fairfield School System (R. 48), which provided in

part that

(1) Negro children in the 9th, 11th, and 12th grades

would be permitted to apply for transfers which transfers

would “be processed and determined by the board pursuant

to its regulations . . . ” (R. 49).

(2) Negro children entering the 1st grade would be as

signed to Negro schools, but if both parents accompany

the child and sign an application on the first day of school,

the child would be permitted to apply to a white school

(R. 50, 151-155).

(3) Applications to be acted upon for the 1965-66 term

had to be filed at the office of the board between 8 :00 A.M.

and 4:30 P.M. on August 30, 1965 (R. 50, 151).

(4) During the 1966-67 terms, the 2nd, 3rd, 8th and 10th

grades would be desegregated. During the 1967-68 terms

the remaining 4th, 5th, 6th and 7th grades would be deseg

regated. Applications by students entering desegregated

grades would be accepted from the period of May 1 through

May 15 preceding the September school term opening for

the desegregated grades (R, 50-51).

(5) Unless Negro students applied for and obtained

transfer, they would be assigned to Negro schools (R. 51).

(6) The Board would publish in a newspaper of general

circulation the provisions of the plan on three occasions

prior to August 30, 1965 (R. 51).

23

On August 18, 1965 and on August 19, 1965 tliG Nogro

plaintitfs and the United States respectively filed objec

tions to the plan (E. 34, 38).

Pursuant to an order of the court the board filed an

Amended Plan for Desegregation of Fairfield School Sys

tem (R. 59). This plan provided that (1) Negro students

in the 7th, 8th, 10th and 12th would be allowed to apply for

transfer to white schools if their applications were sub

mitted to the board on or before August 30, 1965, the ap

plications to be processed by the board “pursuant to its

regulations” (R. 60). (2) Negro children entering the 1st

grade must attend a Negro school unless the parents of the

child on the first day of school apply for his assignment

at a white school (R. 61). (3) Applications of Negro chil

dren for admission to white schools or white children to

biegro schools are to be reviewed by the Superintendent

“pursuant to the regulations of the board” (R. 61), (No

similar process is required for applications of Negroes for

transfer to Negro schools or white children to white schools.)

(4) During the entire month of May 1966 applications by

Negro children for transfer to white schools in the 2nd, 3rd,

9th, and 11th grades for the 1966-67 school term will be

accepted. (No time limit was provided by which Negro stu

dents must be informed of whether their application has

been accepted. No provision is made for publication of no

tice prior to May of 1966) (R. 61-62 and 157-158). (5)

During May of 1967 applications by Negro students for

transfer to the remaining segregated 4th, 5th, and 6th

grades will be accepted by the board for the 1967-68 school

term. (No time limit is provided by which these Negro stu

dents must be informed of whether their application is ac

cepted. No provision is made for publication of notice prior

to May of 1967) (E. 62 and 157-158). (6) Except for those

students applying for and receiving transfer, the schools

24

within the Fairfield system will remain segregated. (7)

One notice of the plan is to be published for three days

prior to August 30, 1965 (R. 63).

By Order of August 23, 1965, the District Court over

ruled the objections of the Negro plaintiffs and the United

States and approved the amended plan of the board (E. 65).

By opinion and decree of September 8, 1965 the court

formalized its finding of a racially segregated school sys

tem in the City of Fairfield and ordered the desegregation

of that system jjursuant to the amended plan (R. 67-72).

These objections were in part, that the plan (1) sub

jected Negro children to a screening process before allow

ing them to transfer (R. 34, see 145, 147-151); (2) made

no provision for the desegregation of bus transport to and

from the schools (R. 35); (3) continued the dual zoning

system (R. 35); (4) excluded six of the minor plaintiffs

(R. 36); (5) failed to give sufficient notice (R. 36); and (6)

did not provide for the enrollment of Negro children in

wdiite schools offering courses which are not available in

Negro schools (R. 39).

On August 20, 1965 the court considered the objections

raised by the Negro plaintiffs and the United States (R.

84). The United States sought to show that the inferior

condition of the Negro schools should have some effect

upon the rate of desegregation and the provisions of the

plan submitted by the board but the district court held this

evidence to be irrelevant (R. 169-170).

On October 22, 1965, the United States filed a Notice of

Appeal from the order of the district court overruling its

objections and approving the plan of the Fairfield Board of

Education (R. 73).

25

D. No. 2 3 ,2 7 4 Caddo Parish School Board

As of the May 4,1965 filing of the Complaint in this case,

the Caddo Parish School Board operated and maintained

a system of public schools in which students, teachers, and

other personnel were assigned on the basis of their race

(R. 74-81, 91-92). No Negro child attended any school in

which white children were in attendance; no Negro teacher

was employed at any school at which white children were

in attendance (R. 74-75). Negro supervisors within the sys

tem were charged with resjjonsibility only for Negro schools

(R. 106). Athletic facilities and bus transportation were

segregated (R. 107-08, 110-12). Racial separation within

the system was maintained through the use of dual at

tendance zones (R. 69, 81).

After the decision of the United States Supreme Court

in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, the parish

school board made no etfort whatsoever to end the practice

of racial segregation in the schools under its jurisdiction

(R. 87). The board was of the opinion that it had no d u t^

or responsibility to end racial discrimination in its schools

until, and only to the extent that, it was ordered to do so

by a court of the United States (R. 87-89).

There are approximately 72 schools under the jurisdic

tion of the board (R. 191). Attending these schools are

approximately 55,000 children of whom 24,000 are Negroes

(R. 191, 189). There are 3,700 employees of the Parish

School Board (R. 191) and of these, 2,200 are teachers

(R. 191). — —^ /V ___ - W

By letter of March 23, 1965, Negro school children and

their parents, by their attorney, notified the President of

the board that they and other Negro children within the

Parish desired to attend the public schools of the Parish

without discrimination on the basis of their race (R. 60).

26

The board did not resijond to the request of these Negro

children and their parents (E. 73), and complaint was filed

in the United States District Court for the Western District

of Louisiana, May 4, 1965 (R. 10). Suit was brought on

behalf of the named Negro school children and on behalf

of the other Negro children in Caddo Parish who were sim

ilarly segregated and discriminated against by the parish

school board (E. 3) and the complaint asked that the board

be enjoined from (1) continuing to operate a compulsory

biracial school system, (2) assigning students initially on

a racial basis, (3) assigning teachers, principals and other

professional personnel on the basis of race, and (4) requir

ing or supporting segregated athletic and other extra

curricular activities (R. 7-10).

The board filed answer to the complaint on May 24, 1965

(R. 11) and hearing was held June 14, 1965, on the motion

of the schoolchildren and their parents for preliminary

injunction (R. 63). By agreement of the parties, the evi

dence adduced served as basis for final adjudication on the

merits (R. 117). On June 14, 1965, the district court found

that the school board had operated a compulsory biracial

system and had thereby violated the rights of Negro school

children. The court enjoined the board from continuing

and maintaining a racially segregated school system and

ordered the board to submit a plan to desegregate the

schools of the parish (E. 133-36). The board submitted

a desegregation plan on July 7, 1965 (R. 138-50). Objec

tions were filed July 21, 1965 (R. 158-60) and hearing was

held on the objections August 3, 1965 (R. 161 et seq.).

As a result of the hearing, the plan was approved, as

modified, and incorporated into an Order On Plan for

Desegregation handed down by the District Court Au

gust 3, 1965 (R. 291-98). The Order provided for the

27

1965-66 term (1) that all initial assigiiTnents of school

children, both those entering the first grade and those

presently enrolled from prior years, would “be considered

adequate” subject only to certain transfer provisions (R.

291-95); (2) Negro children coming into the first grade

and those graduating(mto^the twelfth grade could apply

for transfer to white schools if they applied within a

five-day period extending from August 9, 1965 through

August 13, 1965 and if their applications met transfer

criteria (R. 292-94) such as available space,® age of the

pupil as compared with ages of pupils already attending

the school to which transfer is requested, availability of

desired courses of instruction, and an aptitude test (R.

147, 243-48) which is part of “the procedures pertaining

to transfers currently in general use by the Caddo Parish

School Board” (R. 292). In addition, the Board was

granted the right to reassign a transfer applicant to a

“comparable” school nearer his residence.® Students en

tering the parish would be initially assigned to formerly

all-white or all-Negro schools (R. 177-78, 295). The order

did not provide for assignment of named plaintiffs to

white schools.

v / '

The order further provided that for the 1966-67 term,

students in the first, second, eleventh, and twelfth grades

would be free to choose whatever school they wished to i

attend, subject to the power of the Board to assign the

student to a “comparable” school closer to the student’s

̂All schools in the Parish are overcrowded (E. 258-59).

® There was much testimony to the effect that Negro and white schools

^■Eere_uniformIy equal and comparabje_ (E. 62, 9l7''27^J~ana~EBlI'‘a]ror'

VI ̂ O *1̂1 TT o il VK10 TTT 1*1 T +0 « ..a*.......! ^ ^ _ .T T . "i” I • 1

n

^ ___ J ^ ^ ............ - T LJ I u J C l x i lA V l K l l / <111 111

nearlyldrfKe’ white chi'raJBjr'TroinTEe rural area of Caddo Parish were

bussed into Shreveport from as much as 19 miles av/ay. Eural NegTo '̂

children were provided with three Negro high schools located at various

points about the county closer to their residence than the Shreveport] 1 / •

schools (E. 274-75). '—b*

28

'■vV ^

residence (R. 296). The order specified that the desegrega

tion be completed for all grades by the 1968-69 school term

(R. 296).

August 18, 1965, Negro school children moved the Dis

trict Court to vacate and reconsider its order and decree

of August 3, 1965 in light of the decision of this Court in

the case of United States v. Bossier Parish School Board,

349 F.2d 1020(2) (5th Cir. August 17, 1965) (R. 300). On

August 20, 1965, the District Court granted the motion

aj^^and ordered (1) desegregation of grades two and eleven,

in addition to grades one and twelve, during the 1965-66

term and (2) shortened the desegregation period by one

year so that all grades would he covered by the choice

plan by the 1967-68 term (R. 303-04).

The plan approved by the District Court has been in

operation for nearly an entire school term. Of the 24,467

(R. 78) Negro children attending public schools in Caddo

Parish (of whom approximately 1,720 are entering first-

graders) only one Negro child has been admitted to a

formerly white school. (See the affidavit attached to the

memorandum in support of motion to consolidate and

expedite. Nos. 23,173; 23,192; 23,274; 23,331; 23,335;

j 23,345; and 23,365 filed by the United States in this Court

I April 4, 1966.)

‘ July 19, 1965, the United States sought leave to inter

vene as of right as party plaintiff (pursuant to 42 U.S.C.

§2000h-2 and Rule 24, P.R. Civ. P.) and to file objections

to the desegregation plan submitted by the Board. At the

August 3, 1965 hearing on the plan, the district court

denied the motion to intervene (R. 166) on October 4, 1965,

the United States filed notice of appeal to this court from

the order denying intervention (R. 305).

4 H

29

Specification o f Error

The district courts erred in:

, a

1. Refusing to find that the school hoards, having es-

iS tablished and maintained racially segregated school sys

tems, are constitutionally obligated to submit desegregm’

tion plans which, in fact, completely disestablish spgrpgarpd

^ a^ rn s^ n d ''e rad icate Negro and white__schoo]s.

2. Approving the so-called free choice provisions con

tained in the plans over objections that such provisions

failed to disestablish racial segregation and despite undis-

putable evidence that:

a. Approval of the plans retains(yirtuallj^ intact Negro

and white schools;

b. The alleged free choice provisions are in reality

transfer schemes perpetuating dual zone lines; ^

c. The plans fail to permit students new to the school

systems to exercise free choice regardless of the grades

affected by the plans;

d. The plans fail to provide for desegregation of facili

ties such as bus transportation;

e. The plans fail to provide notice of their provisions

other than in newspapers of general circulation;

;■ f̂ -tnxeept in Caddo Parish! The plans ̂ f^ilJ^-^rcmde ^

for the upgrading c^liegrm-sdinOlFso^tTrTnake^tr^sfers \

' a--realisthrx5onsideration for all pupils;

g. The plans fail to provide for alternative assignment

criteria where facts reveal such criteria would lead to

significant desegregation.

30

3. Approving gradual so-called free choice desegrega

tion plans despite the absence of valid administrative

factorsjustifying such delay knd (except in Caddo EaxSET'N

^desp ite the fact th a t i^ ^ educational facilitie^ r e cleaxly

inferior.

4. Refusing to find that staff desegregation is a pre

requisite for etfective school desegregation requiring the

immediate submission of specific plans providing for both

(a) nonracial hiring and assignment of staff personnel

and (b) assignment of staff personnel based on race in

order to correct the past effects of segregation and dis

crimination.

A R G U M E N T

V /

V

V'

I.

The Plans Approved by the District Courts Fall Short

of This Court’s Standards With Regard Both to Pupil

and Teacher Desegregation.

In Price v. Denison Independent School District, 348

F.2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1965), this Court adopted the United

States Office of Education’s Statement of Policies for

School Desegregation under Title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 (April 1965) as its minimum desegregation

standards. In March 1966, a Revised Statement of Policies

for School Desegregation was issued, which revised state

ment is no less appropriate to current school desegrega

tion questions than was the statement issued in April 1965.

See Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103

and Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 355 F.2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966).

31

A.

The Tnim'mnTn standards for school desegregation plans

were set out in extenso in Singleton v. Jachson Municipal

Separate School District, 355 F.2d 865, 870-71 (5th Cir.

1966). Those standards briefly are as follows:

1. All grades must he desegregated by September 1967;

2. Individuals in segregated grades are permitted to

transfer to schools from which they were originally ex

cluded or would have been excluded because of their race;

3. Services, programs and activities, including buses,

shall be available without discrimination on the basis of

race;

4. An adequate start must be made toward elimination

of race as a basis for staff employment so that school sys

tems will be totally desegregated by September 1967;

5. Proper notice, including use of newspapers, radio

and television facilities, must be given to children and their

parents of the desegregation plan;

6. Dual geographic zones must be abolished as a basis

for assignment;

7. Additional choices of schools must be made available

where the first choice is unavailable.

The plans in these cases fail to meet these criteria. Al

though every plan provides for complete pupil desegTega-

tion by September, 1967, no plan permits individuals in

segregated grades to transfer to schools from which they

were originally excluded or would have been excluded be

cause of their race. Thus the Jefferson County plan makes

32

no provision, other than for grades desegregated by the

plan, for immediate transfers in cases where initial assign

ment is based on race. The Bessemer plan specifically

provides that all students are to remain in their assigned

schools unless their grades are desegregated under the

plan. The Fairfield plan makes no mention of a pupil’s

right to transfer from a segregated grade which is not

desegregated under the plan. 1 Under the Caddo parish

plan, no provision is made for" transfers other than in

grades assertedly desegregated under the plan. In addi

tion, Negro children moving to Caddo Parish during the

school year can only attend Negro schools. All of the

plans are, therefore, deficient under Rogers v. Paul, 382

U.S. 198; Singleton v. Jackson Muniqj^l Separate School

District, 355 F.2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966).\

None of the plans provides for desegregation of services,

programs, and activities, such as bus transportation. For

example, the Jefferson County plan is silent on the ques

tion of bus transportation even though the superintendent

testified that bus routes overlapped because of passenger

segregation. Bessemer’s pupils needing bus transportation

receive the school board’s aid in obtaining reduced fares

on buses not operated by the board. The Fairfield plan

does not mention bus desegregation. j^ d d o Parish’s bus

transportation is racially segregated and the plan was

silent as to measures corrective of this condition.)

None of the plans provide for proper notice to children

and parents of their contents. The second Singleton

case found notice adequate where radio and television

facilities were used in addition to newspaper announce

ments. The Jefferson County plan specifies only that news

paper announcements would be made. The Bessemer plan

provides for one newspaper announcement. Thq,,Fairfield

plan requires only newspaper announcements. pile Caddo

33

Parish original plan provided for newspaper announce

ments in 1965-66 and for individual notices to parents via

their children’s report cards for later school years. The

district court’s order in the Caddo Parish case, however,

made effective most of the original plan with the notable

exception of the notice provisions.]

All of the plans give insufficient time to pupils and their

parents desiring to implement the desegregation formulae.

The Jefferson County plan provided for three regularly

spaced newspaper announcements of the plan between

July 22 and August 9, 1965. Transfer requests in the

ninth, eleventh and twelfth grades were to be filed with

the school board on or before August 9, 1965; transfer

requests for the seventh grade were to be filed on or before

September 1, 1965, following three newspaper announce

ments between August 27, and 31, 1965 (E. 31, 33-34, 53,

67-68). Transfer requests for students entering the school

system for the first time are to be filed the first day of

school in segregated schools (R. 31-33, 67-68). For school

years subsequent to September, 1965, three newspaper

notices published some time in April each year are sup

posed to alert pupils and parents to file transfer applica

tions between May 1-15, 1966 or May 1-15, 1967 (R. 33-34,

68).

The Bessemer plan merely provided for a single news

paper announcement between July 9, 1965 and August 13,

1965. Parents of children in grades four, seven and ten

desiring transfers were required to file an application on

or before Augnst 13, 1965. Parents of first grade children

could apply for transfers on the first day of school. For

school years after September, 1965, notice of the time

(May 1-15) for filing applications to transfer is to be pub

lished only once at an unspecified date in a city newspaper.

34

In Fairfield, the plan’s provisions were to be published

in a newspaper three times between August 23 and August

30, 1965, and applications for transfers were to be filed

for the seventh, eighth, tenth and twelfth grades on or

before August 30, 1965. Students enrolling in the first

grade were to report to the nearest segregated school on

the first day of school (September 1, 1965) and apply for

transfers. For school years after September, 1965, appli

cations must be filed for desegregated grades in May, 1966

or May, 1967, but the plan does not provide for notice in

any respect after August, 1965.

\^ n Caddo Parish, the plan’s provisions were to be pub

lished three consecutive days not later than Augnist 5,

1965. Applications for transfers in the first and twelfth

grades were to be filed August 9 through August 13, 1965.

Notice of desegregation in the second and eleventh grades

was to he published in a newspaper August 20, 21 and 22,

1965. From August 23 to August 25, 1965, applications

for transfer were to be made at the school board. For

school years after September 1965, the original Caddo

Parish plan provided that six months after the beginning

of the school year, a letter would be sent via each pupil

to his home specifying the plan’s provisions and giving

each parent thirty days to file an application. The plan

ordered by the district court omitted these provisions and

provided'ToF’ no notlceof the plan after September, 1965.

None of the plans abolishes dual geographic zones for

purposes of pupil assignment. The Jefferson County plan

is quite explicit in providing that pupils may transfer from

the school to which they are initially assigned on a racial

basis to another school. The Bessemer plan also permits

merely a transfer, after initial assignment to a segregated

school, to effect desegregation. The Fairfield plan likewise

permits only transfers from segregated schools to effect de-

35

segregation. \The Caddo Parish plan not only contains simi

lar transfer p?imsions after an initial racial assignment to

a segregated scho.aLhnt also attaches such additional cri-

'teria as the passing of an aptitude test. Thus all plans

perpetuate dual racial zones and permit transfers between

them under the guise of “freedom of choice.”

None of the plans specifies that additional choices of

schools are available where a pupil’s first choice is not.

The Jelferson County plan is silent on the question of

additional choices. Equally silent on this question are the

plans in Bessemer, Fairfield, and Caddo Parish.

This Court has now clearly held that school boards

operating a dual system are required by the Constitution,

not merely to eliminate the formal application of racial

criteria to school administration, but must by affirmative

action seek the complete disestablishment of segregation

in the public schools. Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Sep

arate School District, 348 P.2d 729 (5th Cir. 1965), 355 P.2d

865 (5th Cir. 1966). As succinctly stated in the first Single-

ton case, “ . . . the second Brown opinion clearly imposes

on public school authorities the duty to provide an inte

grated school system.” 348 F.2d at 730 n. 5.

None of the plans effectively desegregates its pupil

population. Thus, in Jefferson County, only twenty-four

Negroes have been admitted during the 1965-66 school

year to formerly all-white schools, in a student popula

tion of 18,000 Negroes and 45,000 whites.’ In the Jefferson

County case, an expert testified that “the best criteria for

effecting desegregation would be the proximity of the pupil

’ Affidavit of St. John Barrett, attached to the Motion to Consolidate

and Expedite Appeals (in Nos. 23173, 23192, 23274, 23331, 23335, 23345,

and 23365) filed by the United States in this Court April 4, 1966 [herein

after cited as Barrett].

36

to the school.” He went into some detail to show that many

Negro schools were situated so that they were farther

away from their pupils than were white schools and that

the best way to effect desegregation was by a geographical

;/ijfeone system based on nonracial assignment. This Court

I i^noted in the second Singleton case, 355 F.2d at 871. that a

I I ffeedum—of'^oice plan is an acceptable method provided

HI dual zones are eliminated. No such abolition has taken

place in Jefferson County, thus making its plan essentially

a transfer scheme rather than a freedom of choice plan.

Since the goal of any school plan must be desegregation,

a so-called freedom of choice plan is contrary to this re

quirement where it does not in fact lead to desegregation

and where it conflicts with a procedure which would so lead,

ie., geographic attendance zones. It is not here urged that

freedom of choice is necessarily an unworkable plan, but

that where freedom of choice fails to accomplish the goal

of desegregation, other methods must be found to attain

the goal. In the case of Jefferson County, the method would

be geographic attendance zones.

In Bessemer, only thirteen Negroes have been admitted

to formerly all-white schools during the 1965-66 school year

in a school system having a student enrollment of 2,920

whites and 5,284 Negroes. In Fairfield, only thirty-one

Negroes have been admitted during the 1965-66 school year

to formerly all-white schools in a school system having

1,779 whites and 2,159 Negroes.! In Caddo Parish, just one

Negro has been admitted to amm’merly all-white school

in a school system having 30,680 whites and 24,467

Negroes^These statistics demonstrate for Bessemer, Fair-

field anS^Caddo Parish the same conclusion as was made

in Jefferson County, namely, that the so-called freedom

* Barrett.

37

of choice plans have not worked and that either exten

sive revision is needed, or another method of desegre

gation should be adopted, such as geographic non-racial

zoning. This Court and other courts have frequently held

that if the application of educational principles and theories

result in the preservation of an existing system of imposed

segregation, the necessity of vindicating constitutional

rights will prevent their use. Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d

256 (8th Cir. 1960); Ross v. Dyer, 312 F.2d 191, 196 (5th

Cir. 1963) and Brooks v. County School Board of Arlington,

Virginia, 324 F.2d 303, 308 (4th Cir. 1963).

The district courts’ acceptance of these plans reflects a

failure to grasp the considered principle that schemes

which technically approve desegregation but retain the

school system in its dual form must be struck down. Goss

V. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 683; Griffin v. County

School Board of Prince Edward County, 377 U.S. 218;

Boson V. Rippy, 285 F.2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960) and Houston

Independent School District v. Ross, 282 F.2d 95 (5th Cir.

1960).

B.

No plan in any of the district courts made provision for

staff desegregation. Failure of the district courts to order

an adequate start towards the elimination of teacher and

other staff segregation is in direct conflict with holdings

of the Supreme Court and this Court. Bradley v. School

Board of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103; Singleton v. Jackson

Municipal Separate School District, 355 F.2d 865, 870 (5th

Cir. 1966).

Prompt faculty desegregation is also required by revised

school desegregation guidelines, issued by the United

States Office of Education, which make each school system

responsible for correcting the effects of all past discrim-

38

n

o\

inatory teacher assignment practices and call for “signifi

cant progress” toward teacher desegregation in the 1966-67

school year. Thus, new assignments must be made on a

nonracial basis “ . . . except to correct the effects of past

discriminatory assignments.” Revised Statement of Pol

icies For School Desegregation (March 1966), <̂ 181.13(b).

The ijattern of past assignments must be altered so that

schools are not identifiable as intended for students of a

particular race and so that faculty of a particular race

are not concentrated in schools where students are all or

p^onderantly of that race. Supra at Sec. 181.13(d).

-f" In view of the desired goal of desegregation, whether by

free choice or unitary geographic zoning, it is imperative

that the school systems here discussed be required promptly

^ to adopt effective faculty desegregation plans. See Dowell

V. School Board of Oklahoma City Public Schools, 244 F.