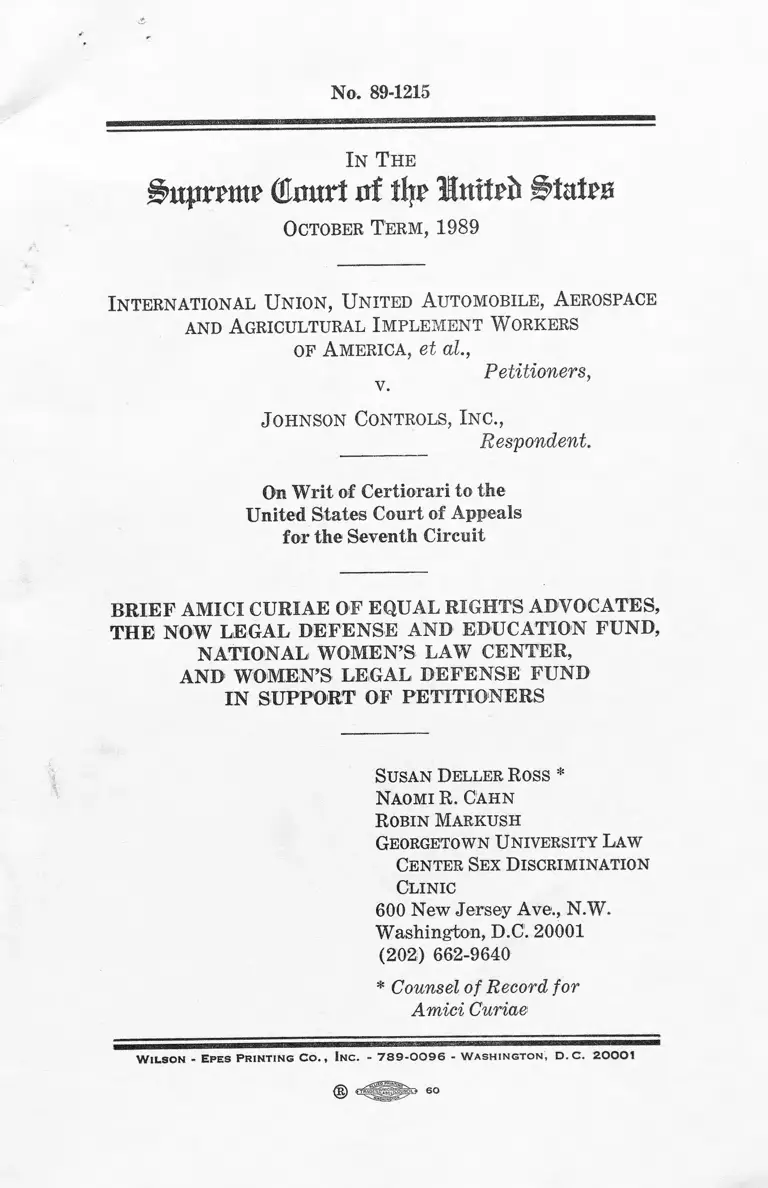

International Union v. Johnson Controls, Inc. Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. International Union v. Johnson Controls, Inc. Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Petitioners, 1989. e0b400ce-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/50325de6-6ed3-4250-bd37-ae1dd5043dc2/international-union-v-johnson-controls-inc-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-petitioners. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

No. 894215

I n T h e

(tart td tty §iatns

October T e r m , 1989

I n ter n a tio n a l U n io n , U n it ed A u tom obile , A erospace

and A gricultural I m p l e m e n t W orkers

of A m erica , et at.,

Petitioners,v.

J o h n so n Controls, I n c .,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Seventh Circuit

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF EQUAL RIGHTS ADVOCATES,

THE NOW LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND,

NATIONAL WOMEN’S LAW CENTER,

AND WOMEN’S LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS

Susan Deller Ross *

Naomi R. Ca h n

Robin Markush

Georgetown U niversity Law

Center Sex D iscrimination

Clin ic

600 New Jersey Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20001

(202) 662-9640

* Counsel of Record for

Amici Curiae

W 1L .S O N - E P E S P R IN T IN G C O . , IN C . - 7 S 9 - 0 0 9 6 - W A S H IN G T O N , D . C . 2 0 0 0 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE AND PARTY SUP

PORTED .........................................................................

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ....... ........... ....... -...........

ARGUMENT .......... ......... ............................. -...................

I. IN ENACTING THE PREGNANCY DISCRIM

INATION ACT, CONGRESS INTENDED TO

MAKE A POLICY OF EXCLUDING ALL FER

TILE WOMEN FROM EMPLOYMENT BASED

ON THEIR PREGNANCY OR POTENTIAL

PREGNANCY A FACIAL VIOLATION OF

SECTION 703 (a) OF TITLE V II.......................

A. Congress Explicitly Considered the PDA’s

Impact on the Johnson Gontrols-Type Policy,

Understood That the PD A’s Language Pro

hibited Such Policies, and Enacted the PDA

Without Change and With Full Understand

ing of Its Reach ...... .......................... -............

B. Congress Made Clear That the PDA’s Pro

hibition on Pregnancy-Based Discrimination

Had the Broadest Possible Application to All

Pregnancy-Related Policies, Rendering Them

Per Se Violations of Section 703(a) of Title

V I I .......................................................-............

II. BECAUSE THE PDA’S SECOND CLAUSE

AND ITS LEGISLATIVE HISTORY MADE

CLEAR THAT THE PREGNANT WOMAN’S

OWN JOB PERFORMANCE ABILITIES, AND

NOT FETAL HEALTH CONCERNS, ARE

THE ONLY RELEVANT CRITERIA FOR

ESTABLISHING A BFOQ, JOHNSON CON

TROLS HAS NO BFOQ DEFENSE TO ITS

FACIAL VIOLATION OF SECTION 703(a)....

11

Page

III. TO PROVIDE FETAL PROTECTION CON

SISTENT WITH TITLE VII, JOHNSON CON

TROLS MUST ADOPT A SEX-NEUTRAL

POLICY THAT APPLIES EQUALLY TO ITS

MALE AND FEMALE WORKERS; SUCH A

POLICY WILL ALLOW THE EMPLOYER

BOTH TO COMPLY WITH TITLE VII AND TO

MAKE THE WORKPLACE SAFE FOR THE

CHILDREN OF BOTH MALE AND FEMALE

TABLE OF CONTENTS—Continued

EMPLOYEES ___ ___ ____ ____ _______ ____ 25

CONCLUSION ............................................................... 30

I ll

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Arizona Governing Committee v. Norris, 463 U.S.

1073 (1983) __________ • ...... -..... - ...... -----..... 28

General Electric Co. v. Gilbert, 429 U.S. 125

(1976)...... ..................... ............. - .......- - .......- 17

International Union, UAW v. Johnson Controls,

886 F.2d 871 (7th Cir. 1989), cert, granted, 110

S.Ct. 1522 (1990) (No. 89-1215) ......... ..-13, 20, 28, 29

Johnson Controls, Inc. v. California Fair Empl.

and Housing Committee, 218 Cal. App. 3d 517,

267 Cal. Rptr. 158 (1990), petition for rev. de

nied, No. S014910 (Cal. May 17, 1990) (LEXIS,

States library, Cal. file)------- ------- ---------- ----- 7, 27

Los Angeles Department of Water & Power v. Man-

hart, 435 U.S. 702 (1978)...................-......... ----- 28

Muller v. Oregon, 208 U.S. 412 (1908) ................... 14

Statutes:

Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978, Pub. L. No.

95-555, 92 Stat. 2076 (1978) (codified in part

at 42 U.S.CL § 2000e(k) (1982)) ________ -..... passim

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e et seq. (1982) ........... .............. - - .......-passim

Toxic Substances Control Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 2601,

2603 (1988) .................... -....................................... 11

Legislative History:

Discrimination on the Basis of Pregnancy, 1977:

Hearings on S. 995 Before the Subcomm. on

Labor of the Senate Comm, on Human Resources,

95th C'ong., 1st Sess. (1977) ....---------- -----------passim

Legislation to Prohibit Sex Discrimination on the

Basis of Pregnancy: Hearings on H.R. 5055 and

H.R. 6075 Before the Subcomm. on Emploijment

Opportunities of the House Comm, on Education

and Labor, Part 1, 95th Cong., 1st Sess. (1^11) ..passim

Legislative History of the Pregnancy Discrimina

tion Act of 1978, 96th Cong., 2d Sess. (Comm.

Print 1979) ........... -........ - .... -......... - ................. passim

XV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Regulations: Page

OSHA, Final Standard for Occupational Exposure

to Lead, 43 Fed. Reg. 52,951 (1978) __ ___ __ 26

Miscellaneous:

Ashford, New Scientific Evidence and Public

Health Imperatives, 316 N. Engl. J. Med. 1084 ... 26

Becker, From Muller v. Oregon to Fetal Vulner

ability Policies, 53 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1219 (1986).. 27

Williams, Firing the Woman to Protect the Fetus:

Reconciliation of Fetal Protection with Employ

ment Opportunity Goals under Title VII, 69

Geo. L.J. 641 (1981) ...... ........ ................ ........ . 27

BRIEF FOR EQUAL RIGHTS ADVOCATES,

ET AL., AS AMICI CURIAE

This brief amici curiae is filed with the consent of the

parties as provided for in this Court’s Rules,

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE AND

PARTY SUPPORTED

The statement of the Interest of Amici is included in

the Appendix. This brief supports the UAW, et al.,

Petitioners.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The Seventh Circuit erred in omitting any discussion

of the legislative history of the Pregnancy Discrimination

Act (PDA), which makes clear that the PDA was in

tended to prohibit the Johnson Controls’ policy of exclud

ing all fertile women from employment based on their

pregnancy or potential pregnancy.

In enacting the PDA, Congress was fully informed

that its language would prohibit a policy of “refusing

certain work to a pregnant employee where such work

posed a threat to the health of either the mother-to-be

or her unborn child,” and enacted the PDA without

change and with full understanding of its reach. The

Chamber of Commerce informed both the House and

Senate that the second clause of the PDA, requiring that

“women affected by pregnancy, childbirth, or related

medical conditions shall be treated the same for all

employment-related purposes . . . as other persons not

so affected but similar in their ability or inability to

work,” would prohibit such policies. Senator Hatch

explored the topic with Dr. Andre Hellegers, who

urged that “if we are talking about untoward effects of

industrial processes on human procreation, we have to

look at the effects on testicles, the effects on ovaries and

the effects on fetuses, all three” in order to protect the

children of both male and female workers. Dr. Hellegers

also discussed the harm that could flow from denying

2

income to pregnant workers; he documented an increase

in premature births, with accompanying risks of mental

retardation and learning disabilities, that was associated

with a decrease in the pregnant worker’s income. Dr.

Hellegers’ views prevailed, for while Senator Hatch was

the leading proponent of narrowing amendments to the

PDA, he did not attempt to accommodate the Chamber

of Commerce’s “fetal protection” concerns.

In defining the term “sex” as it appears in Title VII

to include “pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical con

ditions,” Congress chose the broadest possible definition

of pregnancy-related discrimination. Since the ability to

become pregnant and bear children is a “medical condi

tion” which is “related” to pregnancy and childbirth, the

PDA explicitly prohibits the Johnson Controls’ ban on all

women who are either pregnant or who might become

pregnant. The legislative history of the PDA, including

the witnesses who testified, the Committee Reports, and

the floor debate, overwhelmingly confirm that view. They

all documented the source of pregnancy discrimination as

including employers’ attitudes about women’s capacity for

childbearing and their potential pregnancies, which led

to discrimination against both pregnant women and

women who might become pregnant. They made clear

that refusing to hire women for such reasons would be

illegal. Thus, in refusing to employ any woman who is

pregnant or who might become pregnant, Johnson Con

trols engaged in a per se violation of Section 703(a) of

Title VII, as amended by the PDA definition, which the

Seventh Circuit erred in refusing even to discuss or

acknowledge.

The Seventh Circuit also erred in ruling that fetal

health concerns can be taken into account in deciding

whether Johnson Controls established a Section 703(e)

bona fide occupational qualification (BFOQ) defense to

its facial violation of Title VII. The second clause of the

PDA applies equally to the Section 703(e) defense, and

requires that the BFOQ decision be grounded solely in

the job performance criterion of an employee’s “ability

3

or inability to work,” as the Chamber of Commerce un

derstood. The testimony, Committee Reports, and floor

debate all make clear that Congress intended that under

the PDA, in Representative Hawkins’ words, “if an em

ployer permits other employees to continue working un

less their doctors regard them as physically unable to

work, it may not force pregnant women off the job, as

many employers have done in the past, while they are

perfectly able to perform their jobs.” As a matter of

law, therefore, under the PDA there can be no BFOQ

defense based on fetal heath concerns. Instead, the sole

criterion for establishing a BFOQ is the employee’s job

performance abilities.

Title VII, as amended by the PDA, requires that em

ployers adopt sex-neutral policies applying equally to

both male and female workers; such policies will enable

the employer genuinely concerned with fetal health to

make the workplace safe for the children of both male

and female employees. Such policies will also avoid the

scientific irrationality of ignoring the effects of male

workers’ exposure to lead. The Occupational Safety and

Health Administration has found “conclusive evidence of

miscarriage and stillbirth in women . . . whose husbands

were exposed” to lead. These problems can arise through

the effect of lead on sperm and through male workers

failing to exercise proper hygiene, thus carrying home

lead on their bodies and clothes and affecting the fetus

of their wives through intimate contact. Stereotypes make

it easy for employers to ignore the role of men in the

area of fetal health and to ignore the role of women in

assuring adequate family income. These were precisely

the kinds of stereotypes that the Pregnancy Discrimi

nation Act was designed to eradicate from the workplace.

4

ARGUMENT

I. IN ENACTING THE PREGNANCY DISCRIMINA

TION ACT, CONGRESS INTENDED TO MAKE A

POLICY OE EXCLUDING ALL FERTILE WOMEN

FROM EMPLOYMENT BASED ON THEIR PREG

NANCY OR POTENTIAL PREGNANCY A FACIAL

VIOLATION OF SECTION 703(a) OF TITLE VII.

The Seventh Circuit’s decision upholding the Johnson

Controls’ policy of refusing employment to all pregnant

women and all women capable of becoming pregnant

scarcely mentioned the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of

1978.1 Even more conspicuously absent from the Seventh

Circuit’s decision is any analysis of the legislative history

of the PDA. That legislative history reveals, however,

as we show below, that Congress intended to prohibit

precisely the employer ban on fertile women workers that

the lower court upheld.

A. Congress Explicitly Considered the PDA’s Impact

on the Johnson Controls-Type Policy, Understood

That the PDA’s Language Prohibited Such Policies,

and Enacted the PDA Without Change and With

Full Understanding of Its Reach.

On the very first day of testimony (April 6, 1977) on

the proposed PDA, the first opponent of the legislation

to speak highlighted as his first reason for opposing the

bill its effect on “Occupational Health.” In both his oral

and written statements, the Chamber of Commerce rep

resentative explained to Chairman Hawkins and the other

Members of the House Subcommittee on Employment

Opportunities:

[The bill] requires that “women affected by preg

nancy, childbirth or related medical conditions shall

be treated the same for all employment related pur

poses.” This would prevent an employer from refus

ing certain work to a pregnant employee where such

1 Pub. L. No. 95-555, 92 Stat. 2076 (1978) (codified in part at

42 U.S.C. § 2000e(k) (1982)) [hereinafter cited as the PDA].

5

work posed, a threat to the health of either the mother-

to-be or her unborn child.

Even though the prospective mother might argua

bly be considered to have assumed the risk by asking

to work in such circumstances, injury to the fetus

might give the child a cause of action against the

employer who, under the bill, would be powerless to

deny the work to the child’s mother during the preg

nancy.

Legislation to Prohibit Sex Discrimination on the Basis

of Pregnancy: Hearings on H.R. 5055 and H.R. 6075

Before the Subcomm. on Employment Opportunities of

the House Comm, on Education and Labor, Part 1, 95th

Cong., 1st Sess. 84, 88 (1977) [hereinafter cited as

House Hearings] (statement and testimony of C. Brock-

well Heylin, labor relations attorney, Chamber of Com

merce of the U.S.). The Chamber submitted a virtually

identical statement to the Senate Subcommittee on Labor

the next month. Discrimination on the Basis of Preg

nancy, 1977: Hearings on S. 995 Before the Subcomm.

on Labor of the Senate Comm, on, Human Resources, 95th

Cong., 1st Sess. 482 (1977) [hereinafter cited as Senate

Hearings] (statement of C. Brockwell Heylin). Thus,

from the opening days of the Congressional hearings,

Congress was on notice that the largest U.S. association

of business and professional organizations, id., believed

that the second clause of the PDA 2 prohibited a policy

virtually identical to the Johnson Controls’ policy, and

that the Chamber opposed the bill for that reason.

Senator Hatch, who later became the leading (though

unsuccessful) proponent of amendments to narrow the

scope and coverage of the PDA, quickly pursued the

Chamber’s points. On the very first day of the Senate

hearings (April 26, 1977), Senator Hatch explored them

2 The second clause provides that “women affected by pregnancy,

childbirth, or related medical conditions shall be treated the same

for all employment-related purposes, including receipt of benefits

under fringe benefit programs, as other persons not so affected but

similar in their ability or inability to work. . . .” 42 U.S.C. § 2000e

(k) (1982).

6

with Dr. Andre Hellegers, a Professor of Obstetrics and

Gynecology and Director of the Joseph and Rose Ken

nedy Institute for the Study of Human Reproduction and

Bioethics at Georgetown University. Senator Hatch’s

questions were based on the Chamber’s, points about the

PDA’s second clause and occupational health:

Senator Hatch: What problems, i f any, do you fore

see in treating pregnant women the same as other

employees who have disabilities that continue to work?

Dr. Hellegers: I can see none. I don’t see any. I

think it is just a question of having a physical exam.

Senator Hatch: Do you think there would arise a

whole slew of OSHA problems, occupational safety

and health problems as a result of pregnant women?

Dr. Hellegers: Let me put it this way: I have long

been an advocate for a massive increase in research

to deal with the effects of poisons, chemicals, physical

or other agents on pregnant working women. How

ever, two other things: Those agents are just as likely

to affect the ovaries of nonpregnant women and there

are in fact today companies that will not hire women

on that specific basis.

But you never dream of thinking that the same

agents may also affect the testicles of men. So if we

are talking about untoward effects of industrial proc

esses on human procreation, we have to look at the

effects on testicles, the effects on ovaries and the

effects on fetuses, all three, and we aren’t doing much

of that.

Senate Hearings at 67 (emphasis added).

With this vivid and cogent remark, Dr. Hellegers

struck at the heart of the stereotype underlying the John

son Controls-type policy: that male participation in the

reproductive cycle is irrelevant to fetal harm and may

therefore be disregarded:3 What Dr. Hellegers recom

3 See Section III infra for a discussion of the scientific data

showing that the sperm of male workers can be affected by their

exposure to lead, thus leading- to fetal harm, and for a discussion

of how male workers who fail to take the appropriate hygiene rneas-

7

mended instead was to examine fetal harm caused by both

male and female worker exposure to chemicals and other

agents, so that the children of both men and women

employees could be protected.

Shortly before this exchange, Dr. Hellegers’ testimony

dealt with another stereotype underlying the Johnson

Controls-type policy: that the denial of jobs to preg

nant women will not harm developing fetuses. The

mother’s income is important to fetal well-being, he ex

plained :

I am secondly in favor of this bill on the grounds

of social good, and I have attached to my testimony a

table on a study that we did in the Kennedy Institute

which relates income to infant outcome. It is ex

tremely clear that as income increases prematurity

decreases, in some instances by almost 50 percent.

What this means, in other words, is that the

penalty of this kind of policy [loss of income during

pregnancy] is paid not just by the woman, it is paid

by the unborn child. One lawyer, incidentally, in one

ures after exposure to lead on the job can bring home lead on theii

bodies and clothes and affect the developing fetus of their wives

through intimate contact. The Johnson Controls-type' steieotype

undoubtedly arises because of the centrality and strength of the

mother-infant relationship in our culture, leading employers simply

to forget about fathers. This is especially so during pregnancy,

-when the fetus is enclosed in the woman’s body, and the father’s

connection to the fetus has no such visible and obvious manifesta

tion.

The tendency to ignore the father’s role in causing fetal harm

was noted by the California Court of Appeal in discussing one of

Johnson Controls’ expert witnesses: “Dr. Noren cavalierly char

acterized the situation this way: ‘If you don’t look for a problem,

you don’t find it.’ ” Johnson Controls, Inc. v. California Fair Empl.

and Hous. Comm., 218 Cal. App. 3d 517, ----- ; 267 Cal. Rptr.

158, 168 (1990), petition for rev. denied, No. S014910 (Cal. May 17,

1990) (LEXIS, States library, Cal. file). Dr. Noren took this posi

tion to explain his belief that there w7as a lack of recent studies on

the “effect of lead in male workers’ reproduction systems,” despite

his recognition that “old studies did link lead exposure in male

lead workers with a high death rate among offspring in the first

years of life.” Id. (emphasis added).

8

ease afterwards said the women can always get

aborted. I happen to be opposed to abortion. All I

can say is that this is a policy which harms not only

women but harms the unborn, either whether you

abort or you do not abort, and markedly increases

the incidence of prematurity.

That goes to the issue of cost because what it

really comes down to is that you pay a penalty either

before birth by keeping income up at that time, or

you pay a penalty after birth in terms of facilities

*for the mentally retarded, learning disabilities on

which millions and millions are spent in this country.

Senate Hearings at 64. His written statement amplified

on these concerns:

The National Institute for Child Health and Human

Development has estimated that prematurity costs

the nation $1 billion per year. A task force report

to Secretary of H.E.W. Califano puts a price tag of

$130 million on each percentage point of prematurity

in the nation. Those costs refer to the cost of care

in hospital nurseries only. They do not reflect the

well known relationship between premature births

and subsequent central nervous system disabilities,

such as mental retardation and learning defects. Its

cost is immense. . . .

. . . On a national scale one does well to remember

that today 40% of all pregnant ivomen work and

large numbers of them are heads of households or

have unemployed husbands so their loss of income

affects their own health and their unborn children's,

at great cost to the nation. . . .

Senate Hearings at 75-76 (emphasis added). Dr. Helle-

gers made the identical point in the hearings before the

House Employment Opportunities Subcommittee. House

Hearings at 54, 58-59.4

4 The American Nurses’ Association also documented the con

nection between loss of income and fetal health, and expanded on

the fetal and neo-natal harms caused by premature birth. “Low

birth weight [due to premature birth] is associated with almost

half of all infant deaths and substantially increases the likelihood

of birth defects,” the Association informed the Senate. Senate

9

On the same day that Senator Hatch explored the

OSHA problems with Dr. Hellegers, he explored several

of the concerns that led him later to offer his narrowing

amendments. For example, he asked a panel of govern

ment witnesses (from the EEOC, the Justice Depart

ment’s Civil Rights Division, and the Labor Department)

a series of questions about whether the bill should con

tain limitations on the “length of time” during which

pregnant workers could receive disability insurance cov

erage—e.g., of “3 weeks for pregnancy disability.” Sen

ate Hearings at 39-45.

Later that day, the Senator returned to his concerns

about limiting the “length of time” for receipt of dis

ability insurance benefits and about possible OSHA prob

lems in a discussion with Clarence Mitchell, the Chair

man of the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights. He

explained to Mr. Mitchell that

maybe there should be some limitations so people

know where they stand and that does literally bother

me. There are many problems that arise in this. It

is a complicated area.

If we grant this particular bill we may have OSHA

problems that we hadn’t thought of, and maybe we

should. These are questions I legitimately have and

want to have answers. But since the vast majority of

insurers in America put a set time because of the

overwhelming mass of statistical evidence showing

that pregnancy is not really a disability but a natural

occurrence in the overwhelming majority of cases

that perhaps there might need to be a limitation

rather than an unlimited generalized bill.

Senate Hearings at 109-10.

Significantly, during the floor debate, Senator Hatch

did indeed offer an amendment to cap disability benefits

at 6 weeks, and thereby attempted to limit the “length

Hearings at 466, 470. Some of the defects listed were “mental

retardation, cerebral palsy, and other neurological disorders.” Id.

at 471. Others included “IQ deficiency and antisocial behavior.” Id.

10

of time” for which women workers who had had babies

could receive disability benefits. He also proposed other

amendments to cover other concerns he had raised from

the first day of the Senate hearings.5 Senator Hatch

did not, however, propose an amendment to allow em

ployers with occupational health concerns to treat fertile

women differently than fertile men, by excluding the

women from employment. He was apparently persuaded

by Dr. Helleger’s point that it is important to examine

the effects of toxic agents on men as well as women, in

order to protect male workers’ children and not just

those of female workers. He may also have been per

suaded by Dr. Hellegers’ eloquent statement about low

income among pregnant women workers causing pre

mature birth, with its attendant risks of learning dis

abilities and mental retardation. Whatever his motiva

tion, however, the significant fact remains that he was

clearly informed about the occupational health issue the

Chamber of Commerce so prominently raised, and knew

which clause of the PDA the Chamber was concerned

about. Yet he chose not even to suggest amending the

PDA to accommodate the Chamber’s concern, despite his

role as the leading proponent of narrowing amendments

to the PDA.

In sum, despite the Chamber of Commerce’s clear warn

ing that the second clause of the PDA “would prevent

5 His proposed amendments included: 1) the six-week limitation

on pregnancy disability benefits discussed swpra- (Amendment No.

830) (rejected), Senate Comm, on Labor and Human Resources,

Legislative History of the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978,

96th Cong., 2d Sess. 56, 96-111, 122-24 (Comm. Print 1979) [here

inafter cited as Leg. H ist.]; 2) an amendment to clarify that a

requirement of covering pregnancy in insurance plans did not apply

to pre-existing conditions (Amendment No. 831) (withdrawn), id.

at 57, 82-84; and 3) an extension of the date of compliance (Amend

ment No. 832) (adpoted), id. at 58, 84-86. Senator Hatch also dis

cussed the enactment of a special pregnancy bill instead of an

amendment to the Civil Rights Act, although this suggestion never

materialized into a proposed amendment. See Senate Hearings at

44.

11

an employer from refusing certain work to a pregnant

employee where such work posed a threat to the health of

either the mother-to-be or her unborn child,” and despite

the fact that a highly visible Senator who offered other

narrowing amendments publicly examined the Chamber’s

concerns, Congress left intact its requirement that

“women affected by pregnancy, childbirth, or related medi

cal conditions shall be treated the same for all employ

ment-related purposes . . . as other persons not so affected

but similar in their ability or inability to work.” And in

the entire legislative history of the PDA, no person or

organization ever suggested to Congress that a different

interpretation of this statutory language than the one

offered by the Chamber applied to the occupational health

problem. Nor did a single Member of Congress or a single

Committee Report indicate any disagreement with the

Chamber’s interpretation.

Moreover, two important Senators were clearly in

fluenced by Dr. Hellegers’ approach of being concerned

about the health of all children.6 Senator Williams, the

Chairman of the Senate Committee on Human Resources,

had been present during Dr. Hellegers’ Committee testi

mony and during Senator Hatch’s questioning of Dr.

Hellegers, When the Senator presented the bill to the

full Senate in his role as floor manager, he pointedly

focused on and used Dr. Hellegers’ testimony at the very

beginning of the PDA floor debate:

Finally, Mr. President, I want to emphasize testi

mony received by the Committee from the American

6 Indeed, fetal health had been the subject of concern in the

Congressional session immediately preceding the one in which the

PDA was introduced. The Toxic Substances Control Act, 15 U.S.C.

§§2601, 2603 11988), enacted on October 11, 1976. specifically ad

dressed concerns for fetal safety by imposing strict reporting and

testing requirements on industry in the production and use of tera

togens and other toxins which present health and environmental

hazards. Clearly such concerns were still fresh in the minds of

the Members of Congress who* began consideration of the PDA less

than six months later.

12

Nurses’ Association,7 and from an eminent obste

trician, Dr. Andre Hellegers, which documented the

concrete connection betiveen loss of income during

the disability phase of pregnancy and a. deterioration

of the health of the pregnant woman and of her child

which results from impaired access to a healthful life

situation.

In addition, there is a relationship between infant

prematurity and income. It is estimated that pre

maturity costs the Nation $1 billion per year for

care and hospital nursing alone, not to mention the

cost of certain lasting effects which can result from

prematurity.

These problems can affect an enormous number of

our Nation’s children. Approximately W percent of

all pregnant wom,en work and, as we know, a large

number of them are heads of households, or have

unemployed or low-income husbands. . . .

. . . We must also consider the cost which is im

posed on society when working women and their

families are denied adequate income for a decent

standard of living. This cost is felt in terms of

medical complications for both the women and their

children. . . .

Leg. Hist, at 65, 66 (emphasis added). Senator Williams’

remarks were soon followed by those of another influential

member of the Committee reporting out the bill, Senator

Kennedy. Senator Kennedy told the Senate:

Since ivomen work to support their families, de

priving them of such coverage at a time they and

their families are very much in need of it discrimi

nates not only against these women but against their

families as well. This discrimination handicaps chil

dren who are born into families where a paycheck—

possibly the only paycheck—has arbitrarily vanished.

Senate Floor Debate, Leg. Hist, at 70 (emphasis added).

Surely these remarks reflect the Senators’ agreement with

Dr. Hellegers’ position that anyone with true concern for

fetal harm would not bar pregnant women from working

and would be sure to look at the impact of toxic chemicals

7 See n.4, supra.

13

on the male reproductive system. Instead, such persons

would make sure that employment environments would be

safe for the children of both the male and female workers

who might be exposed to toxic substances, by reducing the

toxic substances to safe levels or taking other appropriate

measures.

B. Congress Made Clear That the PDA’s Prohibition on

Pregnancy-Based Discrimination Had the Broadest

Possible Application to All Pregnancy-Related Poli

cies, Rendering Them Per Se Violations of Section

703(a) of Title VII.

The Johnson Controls’ fetal protection policy, adopted

in 1982, prevents all women who are “capable of bearing

children” from working in “jobs involving lead exposure

or which could expose them to lead through the exercise

of job bidding, bumping, transfer or promotion rights.”

International Union, UA W v. Johnson Controls, 886 F.2d

871, 877 (7th Cir. 1989). The only women who are

exempted are those who can prove, with medical docu

mentation, that they are infertile. Id. at 876 n.8. Thus,

all pregnant women and all women who might ever become

pregnant are excluded from work in this group of jobs.

Conversely, no men are excluded from these jobs. Even

fertile men are permitted to work in a job in which they

might be exposed to lead.

In defining the term “sex” as it appears in Title VII

to include “pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical con

ditions,” 42 U.S.C. § 2000e(k) (1982), Congress chose

the broadest possible definition of pregnancy-related dis

crimination. The definition does not stop with pregnancy

and childbirth, but is expanded to include any “related

medical conditions.” Since the ability to become pregnant

and bear children is surely a “medical condition” which

is “related” to pregnancy and childbirth, the PDA ex

plicitly prohibits the Johnson Controls’ ban on all women

who are either pregnant or who might become pregnant.8

8 The expansiveness of the definition is further demonstrated

by the second clause, which extends its reach to all “women affected

14

The legislative history of the PDA overwhelmingly con

firms that view. The witnesses who testified before the

relevant Committees, the Committee Reports, and the

floor debate all reflected a single, unanimous, perspective.

First, the source of pregnancy discrimination was em

ployers’ attitudes about women’s capacity for childbear

ing and their potential pregnancies, and these attitudes

led to discrimination against both pregnant women and

women who might become pregnant. Second, the PDA

should ban all such discrimination.

This perspective was developed from the very first day

of hearings and the opening panel of witnesses. The lead

panel included the Co-Chair of the Campaign to End Dis

crimination Against Pregnant Workers (a broad-based

coalition of women’s rights organizations, civil rights

groups, labor unions, and other public interest groups

working to enact the PDA) and a law professor who

worked closely with the Campaign. Professor Wendy W.

Williams’ statement started by describing the history of

protective labor laws and their relationship to attitudes

about pregnancy. As the prime example, she quoted from

this Court’s holding in Muller v. Oregon, 208 U.S. 412,

421 (1908), justifying restrictive labor laws for women

only on the early “fetal-protection” theory that since

“healthy mothers are essential to vigorous offspring, the

physical well-being of woman becomes an object of public

interest and care in order to preserve the strength and

vigor of the race.” 9 She then recounted the history of em

ployers’ policies towards pregnancy and summarized that

history in the following terms:

by . . . related medical conditions,” 42 U.S.C. § 200Qe(k) (1982)

(emphasis added), as the House Report agreed. See text at n.10,

infra,.

9 House Hearings at 6 (statement of Wendy Williams) ; Senate

Hearings at 124 (same). This quote should be read in light of the

Court’s position that women were properly placed in a class by

themselves because of their “physical structure” and “performance

of maternal functions.” Muller v. Oregon, 208 U.S. at 420.

15

[T] he common thread of justification running

through most policies and practices that have dis

criminated against all women in the labor force

rested ultimately on the capacity of women to become

pregnant and the roles and behavior patterns of

women that were assumed to surround that fact of

pregnancy.

. . . Moreover, even women who don’t actually

become pregnant are, until they pass childbearing

age, viewed by employers as potentially pregnant

and all women are subject to the effects of the stereo

types that women are marginal workers with all the

multifaceted consequences this has for hiring, job

assignment, promotion, pay, and fringe benefits.

House Hearings at 11-13, 43 (statement and testimony

of Wendy Williams) (emphasis added). The Campaign’s

Co-Chair made a similar point:

The Campaign supports H.R. 5055 because it will

restore Title VII as an effective tool in eradicating

sex discrimination in employment. It will reinstate

what we believe Congress always intended—that all

sex discrimination be eliminated, root and branch,

from the market place, especially including discrimi

nation focussed on that one condition which makes

women different from men—their childbearing ca

pacity.

Home Hearings at 82, 47 (statement and testimony of

Susan Deller Ross) (emphasis added). Both women made

the same points before the Senate. Senate Hearings at

113, 118, 129-31, 151.

Other witnesses repeated this theme. The Vice-Chair

and Acting Chair of the EEOC explained:

There can be no question that the wide range of

employment policies directed at pregnant women—

or at all women because they might become pregnant

—constitutes one of the most significant hindrances

to women’s equal participation in the labor market.

16

Policies which disadvantage women when they

become pregnant— or even because they might become

pregnant—endanger the limited financial security

they now have.

House Hearings at 122-23 (testimony of Ethel Bent

Welsh) (emphasis added) ; Senate Hearings at 32.

Drew Days, the Assistant Attorney General in charge

of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, testi

fied that “loss of income and employment opportunities,

and limitations on reinstatement rights all operate to

make women, whether pregnant, potentially pregnant, or

formerly pregnant, second-class citizens in the employ

ment sphere.” Senate Hearings at 56 (statement) (em

phasis added) ; House Hearings at 135. Laurence Gold,

Special Counsel for the AFL-CIO, noted that “the overall

affect [sic] of the special disadvantages imposed on preg

nant women, and women workers because they might

become pregnant, is to relegate women in general, and

pregnant women particularly, to a second-class status

with regard to career advancement and continuity of em

ployment and wages.” Senate Hearings at 209 (state

ment) (emphasis added) ; House Hearings at 65. Ms.

Ruth Weyand, also a Co-Chair of the Campaign, explained

that “employers rely on pregnancy to justify all forms

of discrimination against women . . . Unfair treatment

because of potential pregnancy, actual pregnancy, or

recent pregnancy touches [women workers] at every

point, and they feel very, very deeply the need to say that

discrimination because of pregnancy is discrimination be

cause of sex. Senate Hearings at 300-01 (testimony)

(emphasis added). Senator Clark stated that he was

cosponsoring S. 995

because it is clear to me that discriminating against

working women on the narrow basis of their capacity

to become pregnant is not consistent with the goals

set forth in the Civil Rights Act. . . . The significance

of this legislation is that it deals with one of the

most important causes of employment discrimination

against women; namely, the age-old belief that a

17

woman’s primary role is to give birth and to care

for the children.

Senate Hearings at 393-95 (testimony) (emphasis added).

Faced with this overwhelming consensus that the Act

must eradicate practices based on women workers’ ca

pacity to become pregnant, both the Senate and House

Committee Reports made absolutely clear that the Act

would have this effect. The Senate Report first described

this Court’s decision in General Electric Co. v. Gilbert,

429 U.S. 125 (1976), and then stated:

In the committee’s view, the following passages

from the two dissenting opinions in the case cor

rectly express both the principle and the meaning of

title VII. As Mr. Justice Brennan stated: “Surely

it offends commonsense to suggest . . . that a classifi

cation revolving around 'pregnancy is not, at the mini

mum, strongly ‘sex related’.” Likewise, Mr. Justice

Stevens stated that, “ (b)y definition, such a rule

discriminates on account of sex; for it is the capacity

to become pregnant which primarily differentiates the

female from the male.”

Thus, S. 995 was introduced to change the defini

tion of sex discrimination in title VII to reflect the

“commonsense” view and to insure that working

women are protected against all forms of employ

ment discrimination based on sex.

S. Rep. No. 95-331, 95th Cong., 1st Sess. 2-3 (1978)

[hereinafter cited as S. Rep.], Leg. Hist, at 39-40 (em

phasis added). The House Report agreed that “the dis

senting Justices correctly interpreted the Act,” and ex

pressly quoted Justice Stevens’ point about the “capacity

to become pregnant.” H.R. Rep. No. 95-948, 95th Cong.,

2nd Sess. 2 (1978) [hereinafter cited as H.R. Rep.], Leg.

Hist, at 148. It went on to specify that “in using the

broad phrase ‘women affected by pregnancy, childbirth,

and related medical conditions,’ the bill makes clear that

its protection extends to the whole range of matters

concerning the childbearing process.” 10 Id. at 151. And it

expressly referred to the historical patterns:

10 See n.8, supra.

18

[T]he consequences of other discriminatory employ

ment policies on pregnant women and women in gen

eral has historically had a persistent and harmful

effect upon their careers. Women are still subject to

the stereotype that all women are marginal workers.

Until a woman passes the child-bearing age, she is,

viewed by employers as potentially pregnant. There

fore, the elimination of discrimination based on preg

nancy in these employment practices in addition to

disability and medical benefits will go a long way

toward providing equal employment opportunities for

women. . . .

H.R. Rep. at 6-7, Leg. Hist, at 152-53 (emphasis added).

Both Senator Williams and Representative Hawkins,

the chairmen respectively of the Senate Committee on

Human Resources and the House Subcommittee on Em

ployment Opportunities, repeated these points in their

presentations to the full Congress. Senator Williams

pointed out tha t:

Because of their capacity to become pregnant,

women have been viewed as marginal workers. . . .

The reported title VII cases reveal a broad array

of discriminatory practices based upon erroneous as

sumptions about pregnancy and the effect it has on

the capacity of women to work.

In some of these cases, the employer refused to

consider ivomen for particular types of jobs on the

grounds that they might become pregnant, even

though the evidence revealed that pregnant women

are perfectly capable of performing the work in

question.

[T]he overall effect of discrimination against

women because they might become pregnant, or do

become pregnant, is to relegate women in general,

and pregnant women in particular, to a second-class

status with regard to career advancement and con

tinuity of employment and wages.

These practices reach all working women of child

bearing age.

19

Senate Floor Debate, Leg. Hist, at 61-62 (emphasis

added). Representative Hawkins spoke in a similar vein

in presenting the bill to the House of Representatives:

“many of the disadvantages imposed on women are predi

cated upon their capacity to become pregnant.” House

Floor Debate, Leg. Hist, at 168 (emphasis added). And

in the moments before final passage of the legislation,

when a compromise had been reached on the abortion

issue,11 even the concluding speaker addressed these same

concerns, in words that speak directly to the Johnson

Controls’ policy:

The legal status of the past often forced women to

choose between having children and working. For

many, wanting children could not outweigh the eco

nomic realities that her income was essential. This

legislation gives her the right to choose both, to be

financially and legally protected before, during, and

after her pregnancy.

Leg. Hist, at 208 (comments of Rep. Sarasin) (emphasis

added).

In the face of this, overwhelmingly consistent legisla

tive history, there simply can be no doubt that Congress

intended to proscribe broadly-defined employer policies

such as that used by Johnson Controls. In refusing to

employ any woman who is pregnant or who might be

come pregnant, the company has engaged in a per se

violation of Section 703(a) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C.

§20Q0e-2(a) (1982), as amended by the PDA’s defini

tion that se-x includes “pregnancy, childbirth, or related

medical conditions.” 42 U.S.C. § 2000e(k) (1982). The

Seventh Circuit clearly erred in refusing even to dis

cuss or acknowledge this language and history.

ii See Section III infra for a discussion of the abortion issue.

20

II. BECAUSE THE PDA’S SECOND CLAUSE AND ITS

LEGISLATIVE HISTORY MADE CLEAR THAT THE

PREGNANT WOMAN’S OWN JOB PERFORMANCE

ABILITIES', AND NOT FETAL HEALTH CON

CERNS, ARE THE ONLY RELEVANT CRITERIA

FOR ESTABLISHING A BFOQ, JOHNSON CON

TROLS HAS NO BFOQ DEFENSE TO' ITS FACIAL

VIOLATION OF SECTION 703(a).

Without discussing any of the relevant statutory lan

guage or legislative history of the PDA, the Seventh

Circuit erroneously held that the PDA allowed it to take

account of fetal risks in determining whether Johnson

Controls had a Section 703(e) BFOQ defense to its policy

of banning all fertile women from employment. Its sole

PDA discussion was as follows:

In the context of the Pregnancy Discrimination

Act, application of the bona fide occupational qualifi

cation defense requires a court to consider the special

concerns which pregnancy poses. A proposed BFOQ

relating to capacity for pregnancy (or actual preg

nancy) will exclude fewer employees than a BFOQ

excluding all women. The court must also consider

the physical changes caused by pregnancy, i.e., the

presence of the unborn child, in determining whether

the employee’s continuance in a particular employ

ment assignment will endanger the health of her

unborn child.

Johnson Controls, 886 F.2d at 893-94 (footnote omitted)

(emphasis added). This conclusion is flatly contradicted

by the PDA and its legislative history.

The BFOQ exception of Section 703(e) of Title VII,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(e) (1982), must be read in light

of the second clause of the PDA. Just as the first clause

of the PDA (defining “sex” to include “pregnancy, child

birth, or related medical conditions” ) applies through

out Title VII wherever the term “sex” is found, so too

does the second clause. Thus, it applies equally to the

BFOQ section, and indeed gives content to the applica

tion of the BFOQ in the pregnancy context.

21

The second clause provides that “women affected by

pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions shall

be treated the same for all employment-related purposes

. . . as other persons not so affected but similar in their

ability or inability to work.” 42 U.S.C. § 2000e(k)

(1982) (emphasis added). It was precisely this clause

that the Chamber of Commerce identified as preventing

“an employer from refusing certain work to a pregnant

employee where such work posed a threat to the health

of . . . her unborn child.” House Hearings at 84; Senate

Hearings a t 482.

The legislative history reveals that the Chamber’s as

sessment was correct, because of the clear meaning of

the term “ability or inability to work.” At the beginning

of both Committee hearings, the Co-Chair of the Cam

paign to End Discrimination Against Pregnant Workers

explained this core concept of the legislation:

[The bill] defines the appropriate standard for elimi

nating . . . discrimination [based on pregnancy,

childbirth, and related medical conditions], by pro

viding that pregnant workers who are able to work

shall be treated the same as other able workers, and

that pregnant workers who are unable to work shall

be treated the same as other disabled workers.

The point here is that no conclusions about a

woman’s medical ability to work can be drawn from

the fact of pregnancy per se. Most women are able

to work through most of their pregnancies (although

less than 5% do suffer some complications that pre

vent them from working). Those pregnant women

who are able to work should be allowed to work like

all other able workers. Conversely, all pregnant

women have some period of medical disability, be

ginning in a normal pregnancy with labor itself and

continuing through the normal recuperation period

of 3 to 8 weeks after childbirth.

Senate Hearings at 151-52, 153 (statement of Susan

Deller Ross) (emphasis added) ; House Hearings at 32-

33, 34. Clearly, the focus of the suggested standard was

22

on the effect of the woman’s pregnancy on her ability

to perform job duties, and the standard contemplated that

any woman who was physically able to perform her job

duties should be allowed to do so. The references to

“medical ability to work” and the examples of medical

inability to work—including labor itself, the 3 to 8 weeks

recuperation period after childbirth, and complicating

medical conditions of pregnancy affecting less than 5

percent of all pregnant women—particularly clarify that

the ability to work concept refers to the woman’s individ

ual ability to perform her job duties.

Different employer stereotypes could affect employers’

decisions to forbid pregnant women to work despite their

ability to do so. Professor Williams discussed a variety

of such stereotypes in her testimony, and specifically in

cluded that of “fetal protection,” in describing a Chil

dren’s Bureau study from the early 1940’s which ex

amined “the practice of firing women when they become

pregnant.” House Hearings at 9; Senate Hearings at

127. The study noted that “the reason often given for

the practice was the protection of the mother and fetus,”

Id.

The theme of equal treatment based on comparable

ability to work—that is, job performance ability—was

reiterated in the Committee Reports and the floor de

bate. Thus, the Senate Report stated:

By defining sex discrimination to include discrimi

nation against pregnant women, the bill rejects the

view that employers may treat pregnancy and its

incidents as sui generis, without regard to its func

tional comparability to other conditions. Under this

bill, the treatment of pregnant women in covered em

ployment must focus not on their condition alone

but on the actual effects of that condition on their

ability to work. Pregnant women who are able to

work must be permitted to work on the same condi

tion as other employees; and when they are not able

to work for medical reasons, they must be accorded

the same rights, leave privileges and other benefits,

as other workers who are disabled from working.

23

S. Rep. at 4, Leg. Hist, at 41 (emphasis added). In

explaining when disability benefits would have to be

paid, the Report clarified that they would be paid “only

on the same terms applicable to other employees-—that is,

generally, only when the employee is medically unable to

work.” Id. (emphasis added). Examples of times when

workers would not have to be paid disability benefits be

cause they were not medically disabled included a preg

nant woman who “wishes, for reasons of her own, to stay

home to prepare for childbirth, or, after the child is born

to care for the child.” Id. (emphasis added). And while

disability benefits would normally be paid for “'4-8 weeks”

after childbirth, since that is “the period of disability

for a normal pregnancy,” on the other hand, “if there

are medical complications of pregnancy or childbirth

which prevent a woman from working for more than the

normal period, the entire disability period . . . would

have to be covered.” S. Rep. at 4, Leg. Hist, at 41-42.

Similarly, in discussing employers’ leave policies, the

Report pointed out, in language that could apply directly

to the Johnson Controls’ policy, that “employers will no

longer be permitted to force women who become pregnant

to stop working regardless of their ability to continue;

. . . and they will not be able to refuse to hire or promote

women simply because they are pregnant.” S. Rep. at 6,

Leg. Hist, at 43 (emphasis added).

The House Report contained virtually identical dis

cussions. See H.R. Rep. at 4-5, Leg. Hist, at 150-51.

And like the Senate Report, the House Report specifically

rejected “mandatory leave for pregnant women arbi

trarily established at a certain time during their preg

nancy and not based on their inability to work.” H.R.

Rep. at 6, Leg. Hist, at 152 (emphasis added).

While the Committee Reports alone would be decisive

on the point that it is solely the pregnant woman’s job

performance abilities that count in determining employer

rights to force her into unemployment, the statements of

the two floor managers during the floor debates reempha

size the unified approach of the Reports. Thus, Represen

tative Hawkins stated:

[EJmployers . . , must treat pregnant women as they

treat other employees similar in their ability or

inability to work. This means, for example, that

if an employer permits other employees to continue

working unless their doctors regard them as physi

cally unable to work, it may not force pregnant

women off the job, as many employers have done in

the past, while they are perfectly able to perform

their jobs.

Leg. Hist, at 24-25 (emphasis added). Senator Williams

explained: “ [t]he central purpose of this bill is to re

quire that women workers be treated equally with other

employees on the basis of their ability or inability to

work.” Senate Floor Debate, Leg. Hist, at 62-63.

These statements make clear that, far from allowing

courts to consider fetal health concerns which have no im

pact on the woman’s job performance abilities, Congress

mandated equal treatment based solely on the pregnant

employee’s ability to work in comparison to other em

ployees not so affected but similar in their ability to

work. In requiring this equality of treatment, Congress

intended to prohibit employers from considering anything

other than the employee’s actual ability to perform the

job—concerns about the health of fetuses or potential

fetuses are simply not relevant. That was a point that

the Chamber of Commerce understood on a first reading

of the second clause of the PDA, but which the Seventh

Circuit entirely ignored. Accordingly, it erred in ruling

that Johnson Controls had established a BFOQ based

solely on fetal health concerns; as a matter of law, these

concerns cannot justify a BFOQ.

Finally, while Johnson Controls has sought tô justify

its policy with scientific data, not even the scientific evi

dence supports a. fetal protection policy that excludes

only fertile women. As shown below, the Johnson Con

trols’ policy is scientifically irrational.

24

25

III. TO PROVIDE FETAL PROTECTION CONSISTENT

WITH TITLE VII, JOHNSON CONTROLS MUST

ADOPT A SEX-NEUTRAL POLICY THAT APPLIES

EQUALLY TO ITS MALE AND FEMALE WORK

ERS; SUCH A POLICY WILL ALLOW THE EM

PLOYER BOTH TO COMPLY WITH TITLE VII AND

TO MAKE THE' WORKPLACE SAFE FOR THE

CHILDREN OF BOTH MALE AND FEMALE EM

PLOYEES-.

Even though the current Johnson Controls’ policy is

invalid under Title VII, Johnson Controls has several

options if it genuinely seeks to adopt policies consistent

with Title VII which also protect the fetus. First, it can

study the hazards caused by the exposure of fertile work

ers of either sex to lead, and adopt a policy which ap

plies equally to all male and female workers. In develop

ing its current policy, the company has focussed only on

the exposure to lead of fertile women, and not of fertile

men. It discounted, or ignored, studies showing the po

tential impact of lead on the male reproductive system

and the concrete ways in which male exposure could af

fect fetal development. As the UAW’s and other amicus

briefs show, the scientific evidence simply does not sup

port a fetal protection policy that applies only to fertile

women, and not to fertile men, and that does not consider

the harms caused by loss of income.

In 1978, less than a month after enactment of the

PDA, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration

found:

There is conclusive evidence of miscarriage and still

birth in women who were exposed to lead or whose

husbands were exposed. Children born of parents

either of ivhom were exposed to lead are more likely

to have birth defects, mental retardation, behavioral

disorders or die during the first year of childhood.

A. Lead has profoundly adverse effects on the

reproductive ability of male and female workers in

the lead industry.

26

B. Lead exerts its effects prior to _ conception

through genetic damage (germ cell alteration), effects

on menstrual, and ovarian cycles and decreased fer

tility in women, decreased libido and decreased fer

tility in men through altered spermatogenesis.

The record in this rulemaking is clear that male

workers may be adversely affected by lead^as well

as women. Male workers may be rendered infertile

or impotent, and both men and women are subject to

genetic damage which may affect both the course and

outcome of pregnancy. Given the data in this record,

OSHA believes there is no basis whatsoever for the

claim that women of childbearing age should be ex

cluded from the workplace in order to protect the

fetus or the course of pregnancy. . . . There is no

evidentiary basis, nor is there anything in this final

standard, which would form the basis for not hiring

workers of either sex in the lead industry.

OSHA Final Standard for Occupational Exposure to

Lead, 48 Fed. Reg. 52,951, 52,954, 52,960, 52,966 (1978)

(emphasis added). Professor Williams has explained

some of the other ways in which the exposure of male

workers to' lead can affect their children:

[T]he pregnant woman, and as a consequence, her

fetus, can be exposed through a male worker to toxic

substances found in the workplace. One well docu

mented way in which such exposure occurs is by male

transportation of hazardous substances from work to

home on his clothes, shoes, or hair.ia Another route,

theoretically likely but as yet unconfirmed, is ex

posure of the pregnant woman and fetus through 12

12 The footnote for this statement cited “A. Hrieko, .[Working

For Your Life: A Woman’s Guide To Job Health Hazards] C-8,

0-9 [(1976)] (children exposed to lead carried home on parent’s

clothing land] Stellman, [The Effects of Toxic Agents on

Reproduction, Occ. Health and Safety 36.] 42 [(Apr. 1979)] (ex

posure to lead carried home on worker’s clothing).’ See also Ash

ford, Netv Scientific Evidence and Public Health Imperatives, 316

N. Engl. J. Med. 1034-85 (1987) (not only is the male reproduc

tive system at risk but men may carry home lead-contaminated

clothing or objects and expose wives and children).

27

vaginal absorption of toxic substances carried in the

seminal fluid of the exposed male worker.13

Williams, Firing the Woman to Protect the Fetus: Recon

ciliation of Fetal Protection with Employment Opportu

nity Goals under Title VII, 69 Geo. L.J. 641, 657 (1981).

These routes of transmission would help explain the

studies linking “lead exposure in male lead workers with

a high death rate among offspring in the first year of

life.” Johnson Controls, 218 Cal. App. 8d at ----- , 267

Cal. Rptr. at 168.

Adopting a policy that applies only to women is scien

tifically irrational if the children of males exposed to lead

can also be harmed. Stereotype, not science, best explains

why Johnson Controls developed such a policy, for many

employers believe that there is an “exclusive connection”

between the mother and birth defects, notwithstanding

scientific studies and common sense about the male role

in reproduction.14 15 Moreover, one author has noted that

“fertile women will be excluded only from higher-paying,

traditionally male jobs and not from lower-paying, tradi

tionally female jobs, even if fetal risks are the same.” ^

The author also discussed the pesticide DBCP; when it

was linked to infertility and sterility in men, it was

banned by the EPA. That suggests a second stereo*

13 The footnote for this assertion stated:

J. Man son & R. Simon, Influence of Environmental Agents

on Male Reproductive Failure, Work and Health op Women

171 (V. Hunt ed. 1979). The authors state: “. . . [D]rugs trans

mitted via the semen during coitus are likely to enter the

systemic circulation of the female. This may constitute a sig

nificant route of exposure for the female as well as the em

bryo.” Id. at 332-33. See also J. Bell & J. Thomas, Effects of

Lead on Mammalian Reproduction in Lead Toxicity 169, 174

(Singha.1 & Thomas, eds. 1980 (“ [TJhere may be a passage of

lead from the male via the semen which could influence the

conceptus directly”).

14 Williams, 69 Geo. L.J. at 660.

15 Becker, From Muller v. Oregon to Fetal Vulnerability Policies,

53 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1219, 1257 (1986).

2 8

type: male workers must be accommodated because their

income is vital to their families, but female workers need

not be, because they are merely secondary workers seek

ing pin money whose income will not be missed. Stereo

typical policies that apply only to women under the cover

of pseudo-science indicate an attempt to discriminate

against women, not an attempt to genuinely help the chil

dren of those workers. To insure genuine protection for

all children, Johnson Controls’ best option is to make the

workplace safe for all workers, by adopting a policy that

applies equally to men and women. Only that option

accords with Senator Williams’ statement during the floor

debates on the PDA that “ [n]o special restrictions ap

plicable to pregnancy or childbirth alone will be per

mitted under this legislation.” Senate Floor Debate, Leg.

Hist, at 103.

It is possible, of course, that Johnson Controls’ policy

was motivated not by fetal health concerns but by cost

considerations. The record below includes no evidence as

to the cost of lowering workplace exposure to lead; there

is merely a conclusory statement that no company has

been able to make batteries without using lead. Cost,

however, is not an excuse for discrimination. See Arizona

Governing Committee v. Norris, 463 U.S. 1073, 1085 n.14

(1983) ; Los Angeles Dept, of Water & Power v. Man-

hart, 435 U.S. 702, 716-17 (1978). In fact, the PDA

was enacted despite projections that its cost would range

from $130 million to $2.5 billion. S. Rep. at 11, Leg.

Hist, at 48; Senate Floor Debate, Leg. Hist, at 98. As

Senator Javits stated: “ [a]s in all legislation designed to

correct social injustices, this bill will entail some costs

to employers and to the public . . . . [T]he costs entailed

are quite insignificant in light of the principle that

underlies this bill.” Senate Floor Debate, Leg. Hist.

at 68.

As yet another justification for its fetal protection

policy, Johnson Controls claimed at the Seventh Circuit

oral argument “that it is morally required to protect chil

dren from their parents’ mistakes.” Johnson Controls,

29

886 F.2d at 912 (Easterbrook, J., dissenting). However,

the legislative history of the PDA shows that Congress

intended to prohibit employers from using a morality

rationale as justification for a policy of refusing to hire

and promote female employees whose morality offended

them. The Congressional intent to prevent employers

from justifying hiring, firing, and no-promotion policies

based on their aversion to the woman’s moral decisions

can be seen from how Congress handled the issue of

abortion.

When the Senate first considered the abortion issue, it

rejected an amendment by Senator Eagleton, which would

have added the following sentence to the first section:

“As used in this subsection, neither ‘pregnancy’ nor ‘re

lated medical conditions’ may be construed to include

abortions except where the life of the mother would be

endangered if the fetus were carried to term.” Senate

Floor Debate, Leg. Hist, at 112. Those opposing the

amendment emphasized, in urging its defeat, that it

would allow employers to impose their moral beliefs on

their employees. As Senator Javits explained, the Eagle-

ton amendment

leaves the employer in a position where, if any em

ployee determines to have an abortion, that employer

can take any adverse discriminatory action. He can

refuse to hire, he can fire, he can demote, he can

deny promotion, he can cut pay. In effect, therefore,

the conscience of the employer would be foisted upon

the employee, and I cannot conceive of our acquiescing

in any such result.

. . . [The amendment] would superimpose the

right of the employer over the constitutionally pro

tected individual conscience of the employee.

Senate Floor Debate, Leg. Hist, at 118-19 (emphasis

added). The Senate then tabled the amendment. Id. at

120. It thus made very clear that an employer could

not “foist” its moral beliefs on an employee through a

policy of firing or refusing to hire women who had had

abortions.

30

While the House bill did contain an abortion exception,

it applied only to fringe benefits, not to hiring and firing

policies. Leg. Hist, at 145. The Conference Committee

narrowed the House’s language even further, to an excep

tion for health insurance benefits alone. House Con

ference Report, Leg. Hist, at 194. This left intact the

original PDA provision barring employers from firing or

from refusing to hire or promote women who had had

abortions. Senator Javits explained: “since the abortion

proviso specifically addresses only health insurance, the

proviso in no way affects an employee’s right to sick pay

or disability benefits or, indeed, the freedom from dis

crimination based on abortion in hiring, firing, seniority,

or any condition of employment other than medical in

surance itself.” Senate Floor Debate, Leg. Hist, at

203. Thus, under the PDA as enacted, employers may not

refuse to hire or promote women who have had abortions.

The policy of refusing to hire or promote women who are

pregnant, or who may become so, out of a claimed moral

concern for the health of their fetuses, fares no better.

In neither case does the employer have a right to foist

its conscience on the woman.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this Court should not disturb the policy

decisions that Congress made in enacting the PDA—

policies that are so clearly spelled out in the comprehen

sive legislative history that the Seventh Circuit simply

ignored. Thus, for the reasons stated above, this Court

should reverse the decision of the Seventh Circuit, grant

summary judgment to the UAW, and rule that the John

son Controls’ policy of banning all fertile women from

employment in the alleged interest of fetal health is a

facial violation of Title VII, as amended by the PDA,

that cannot be justified by a BFOQ.

Respectfully submitted,

31

Susan Deller R oss *

Naomi R. Ca hn

R obin Markush

Georgetown U niversity Law

Center Sex Discrimination

Clin ic

600 New Jersey Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C'. 20001

(202) 662-9640

* Counsel of Record for

Amici Curiae

Thanks are extended to attorney Resa Goldstein, and Georgetown

University Law Center students Chris Jacobson and Edwin Rod

riguez for their help in preparing this brief.

APPENDIX

la

APPENDIX

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

This brief amici curiae is submitted on behalf of

Equal Rights Advocates, NOW Legal Defense and Edu

cation Fund, the National Women’s Law Center, and the

Women’s Legal Defense Fund, These organizations were

leaders in the Campaign to End Discrimination Against

Pregnant Workers, the coalition which was the principal

proponent of the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, and/or

have represented women with claims of pregnancy-based

discrimination. Amici believe that the decision below

has the potential for causing great harm to enforcement

of the PDA. This brief amici curiae is filed in support

of the Petitioners in this case.

Equal Rights Advocates, Inc. (ERA) is a San Fran

cisco based public interest law firm dedicated to securing

legal and economic equality for women through litiga

tion, advocacy and public education. A major portion of

ERA’s work over the last sixteen years has been dedi

cated to the elimination of sex discrimination in the

workplace. ERA was a member of the Campaign to End

Discrimination Against Pregnant Workers, a broad-

based coalition that worked to enact the PDA. ERA be

lieves that employment discrimination based on preg

nancy and a woman’s reproductive capacity adversely

affects large numbers of women workers and their right

to equal employment opportunities.

The NOW Legal Defense and Education Fund (NOW

LDEF) is a non-profit civil rights organization that per

forms a broad range of legal and educational services

nationally in support of women’s efforts to eliminate sex-

based discrimination and secure equal rights. NOW

LDEF was founded in 1970 by leaders of the National

Organization for Women, a membership organization of

over 250,000 women and men in more than 750 chapters

throughout the country. A major goal of NOW LDEF

is the elimination of barriers that deny women economic

2a

opportunities. Discrimination against women based upon

reproductive capacity, as a major barrier to women’s full

and equal employment, is a central concern to NOW

LDEF.

The National Women’s Law Center is a non-profit or

ganization founded in 1972 as the Women’s Rights Proj

ect of the Center for Law and Social Policy, and it be

came an independent organization in 1981. The Center

first became actively involved in the issue of pregnancy

discrimination in 1973, through its representation of

amici curiae in support of the plaintiffs at the trial level

in General Electric Co. v. Gilbert, 429 U.S. 125 (1976).

The Center continued its participation in this landmark

case in the Court of Appeals and Supreme Court, Fur

ther, once Gilbert was decided, the Center became active

first in developing and then participating in the Cam

paign to End Discrimination Against Pregnant Workers.

In this capacity, the Center closely monitored the progress

of the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, and provided tech

nical assistance in support of its passage. Since that

time, the Center has participated in numerous cases ad

dressing problems of pregnancy discrimination, counseled

victims of such discrimination, and served as a legal re

source to combat pregnancy discrimination in many

forums.

The Women’s Legal Defense Fund (WLDF) is a non

profit, membership organization founded in 1971 to ad

vance women’s equality. WLDF combats gender-based

discrimination in employment through litigation of sig

nificant cases, the operation of a counseling program,

and agency advocacy before the EEOC and other agen

cies charged with enforcement of the equal opportunity

laws. WLDF has had a particular interest in the issue

of pregnancy-based employment discrimination because

of its theoretical and practical centrality to equal em

ployment opportunity for women. Thus, after this Court’s

decision in General Electric Co. v. Gilbert, supra, WLDF

played a leading role in the coalition formed to enact the

3a

Pregnancy Discrimination Act. After the PDA’s enact

ment, WLDF advocated issuance of strong guidelines in

terpreting the PDA by the Equal Employment Oppor

tunity Commission, and instituted a Pregnancy Rights

Monitoring Project to educate the public about their

rights under the PDA and to monitor government agen

cies’ enforcement of that Act; WLDF continues this role

to the present day. In 1979, WLDF began to advocate

that the EEOC issue guidelines on the application of

Title VII, as amended by the PDA, concerning employ

ers’ exclusion of fertile women based on alleged occupa

tional reproductive health hazards, and founded a Coali

tion on the Reproductive Rights of Workers to promote

public policy that ensures workplaces safe for all work

ers, including pregnant women. Again, WLDF has con

tinued to comment on and monitor the development of

EEOC policy regarding reproductive health hazards.

WLDF has also participated as amicus in the two cases

that have come before this Court on the proper interpre

tation of the PDA: Netvport News Shipbuilding & Dry

Dock Co. v. EEOC, 462 U.S. 669 (1983), and California

Federal Savings & Loan Assoc, v. Guerra, 479 U.S. 272

(1987). Finally, WLDF has led the efforts to secure

passage of the federal Family and Medical Leave Act in

Congress and of similar laws in the states.

The American Civil Liberties Union, which was also

a major participant in the Campaign to End Discrim

ination Against Pregnant Workers, fully endorses this

amid curiae brief, but is submitting a separate brief on

behalf of itself and other amici.