Milliken v. Bradley Brief for Bradley Respondents

Public Court Documents

January 28, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Milliken v. Bradley Brief for Bradley Respondents, 1977. 7bb40dbe-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/503aecc1-9ea0-430e-9dda-0f0278a90729/milliken-v-bradley-brief-for-bradley-respondents. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

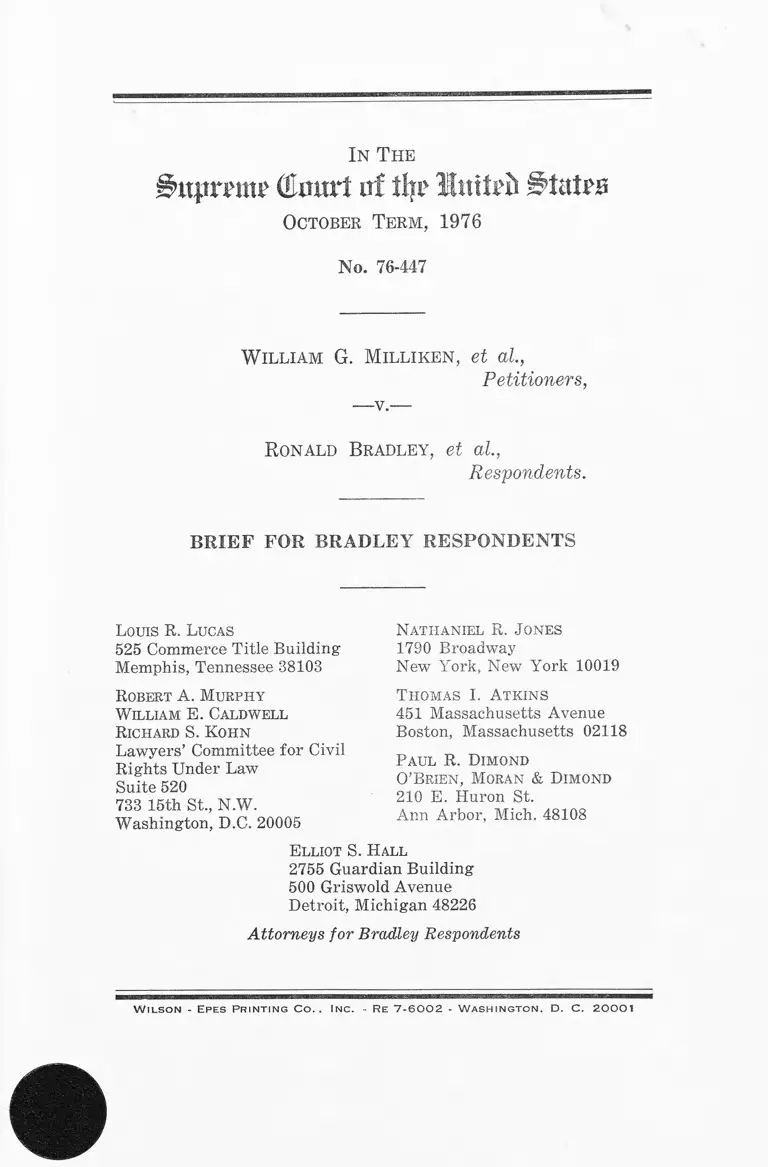

In T he

Batpnw (ttmul uf life Hutted Bint?#

October Term , 1976

No. 76-447

W illiam G. M illiken , et al,

Petitioners,

R onald Bradley, et al,

Respondents.

BRIEF FOR BRADLEY RESPONDENTS

Louis R. Lucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Robert A. Murphy

William E. Caldwell

Richard S. Kohn

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

Suite 520

733 15th St., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

Nathaniel R. Jones

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

Thomas I. Atkins

451 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02118

Paul R. Dimond

O’Brien, Moran & Dimond

210 E. Huron St.

Ann Arbor, Mich. 48108

Elliot S. Hall

2755 Guardian Building

500 Griswold Avenue

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Attorneys for Bradley Respondents

W il s o n - Ep e s Pr in t in g C o . . In c . - R e 7 - 6 0 0 2 - W a s h in g t o n . D . C . 2 0 0 0 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES...... ................... - ....... ........... . IV

COUNTER-STATEMENT OF THE QUESTIONS

PRESENTED ........................... 1

CONSTITUTIONAL, STATUTORY AND REGULA

TORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED.......................... 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE................................. 2

A. Introduction .................. ................................ .......... 2

B. The Pre-Milliken Proceedings ______ 4

C. The Post-Milliken Proceedings in the District

Court ............................. 9

D. The Judgment of the Court of Appeals.... ........ 14

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .....___ 17

ARGUMENT ................... 18

INTRODUCTION..._______ _______ ___________ ___ _ 18

I. RELIEF ANCILLARY TO PUPIL DESEG

REGATION IS APPROPRIATE TO REM

EDY THE CONTINUING HARMFUL EF

FECTS OF THE DE JURE SEGREGATION

VIOLATION AND OTHERWISE TO INSURE

THE TRANSITION TO AND MAINTE

NANCE OF A RACIALLY NONDISCRIMIN-

ATORY DETROIT PUBLIC SCHOOL SYS

TEM. ___________________ _________________ ____ 24

II. APART FROM THE COST IMPACT, THERE

IS NO TENABLE CLAIM THAT CONSTITU

TIONAL PRINCIPLES OF FEDERALISM,

THE TENTH OR THE ELEVENTH AMEND

MENT BAR STATE DEFENDANTS’ PAR

TICIPATION IN IMPLEMENTING THE AP

PROPRIATE ANCILLARY RELIEF_________ 30

II

TABLE OF CONTENTS—Continued

Page

III. THE ELEVENTH AMENDMENT DOES NOT

IMMUNIZE STATE DEFENDANTS FROM

BEING REQUIRED TO IMPLEMENT JOINT

LY WITH THE DETROIT BOARD THE PRO

SPECTIVE ANCILLARY RELIEF, INCLUD

ING SHARING IN THE COSTS OF IMPLE

MENTATION. _____________ - ........... ------- ------- 34

A. The Judgment Below Is Not Barred by

the Eleventh Amendment Because the Im

pact on the State Treasury Is a Conse

quence of Complying with Prospective In

junctive Relief.................................... - ----------- 34

B. In the Alternative, Congress Has Specific

ally Lifted Any Sovereign Immunity from

this Suit Otherwise Enjoyed by the De

fendant State Board of Education Pursu

ant to Congress’ Enforcement Powers Un

der Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment; and, in Any Event, the State Has

Specifically Waived Its Immunity to Suit

H ere._______________ ________—------------ ---- 38

C. In the Alternative, the Judgment Below Is

Not Barred by the Claim of Sovereign Im

munity Because Section 1 of the Four

teenth Amendment, Both in Its Direct Im

pact and as Enforced by Congress Through

42 U.S.C. § 1983, 28 U.S.C. §1331 and

Other Reconstruction Legislation, Super

cedes the Eleventh Amendment.------ -----— 42

IV. IN THE PARTICULAR CIRCUMSTANCES

OF THIS CASE THE LOWER COURTS DID

NOT ABUSE THEIR EQUITABLE DISCRE

TION IN ORDERING THE STATE DEFEND

ANTS TO IMPLEMENT ANCILLARY RE

LIEF JOINTLY WITH THE LOCAL DE

FENDANTS............................................................... 44

in

Page

CONCLUSION ................... 50

APPENDICES

A. The Impact of the Fourteenth Amendment

and Ensuing Reconstruction Legislation on

State Sovereignty—................................ la

B. Constitutional, Statutory, and Regulatory

Provisions Involved ........ 9a

TABLE OF CONTENTS— Continued

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

Adams V. Rankin County Board of Education, 485

F.2d 324 (5th Cir. 1973) _____ _____ ___________ 17n

Adickes V. S.H. Kress & Co., 398 U.S. 144 (1970).. 2a, 4a

Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405

(1975) ___________________ __ _____________ 25, 45n, 49

Alexander V. Holmes County Board of Education,

396 U.S. 19 (1969)_________________________ _- 38

Bell v. Hood, 327 U.S. 678 (1946) _________ ___ ...26, San

Bigelow V. RKO Radio Pictures, 327 U.S. 251

(1945) ___________________________ 25n

Blue V. Craig, 505 F.2d 830 (4th Cir. 1974)_____ 4a, 6an

Bradley V. Milliken, 484 F.2d 215 (6th Cir. 1973),

rev’d in part, 418 U.S. 717 (1974)________ 2, 3, 27, 31

Bradley V. School Board, 416 U.S. 696 (1974)......40, 41n

Brinkman V. Gilligan, 518 F.2d 853 (6th C'ir.

1975), cert, denied, 423 U.S. 1000 (1976)_____ 41n

Brown V. Board of Education (Brown I), 347

U.S. 483 (1954) __________________________ __ _ 6n, 44

Brown V. Board of Education (Brown II), 349

U.S. 294 (1955)___________________25, 33n, 36, 45n, 48

Brown V. Swann, 10 Pet. [U.S.] 497 (1836)_____ 25

Carter V. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 327 (8th Cir.

1971) ________________________________________ 33n

Chisolm V. Georgia, 2 U.S. 419 (1793)__________ la

City of Kenosha v. Bruno, 412 U.S. 507 (1973)__ 5a

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883)............. ........ 2a, 7a

Dandridge V. Williams, 397 U.S. 471 (1970)_____ 8n, 23,

41n, 44

Davis V. Board of School Comm’rs, 402 U.S. 33

(1971) 45n

District of Columbia V. Carter, 409 U.S. 418

(1973) _________________________ 7a

Edelman V. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974) ....3,16,19, 31,

33, 34-38, 39, 42, 43, 4a-6a

Elrod V. Burns, 49 L.Ed.2d 547 (1976)__________ 4

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339 (1880) .33, 39, 43, 2a, 6a

Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908)___ 3,19, 31, 32, 33,

35-37, 43

V

Fitzpatrick V, Bitzer, 49 L.Ed.2d 614 (1976)___ 3,19, 33,

39, 40, 41, 43, 2a, 3a-6a

Ford Motor Co. V. Dept, of Treasury, 323 U.S.

459 (1945) _____________ 37n

Ford Motor Co. V. United States, 405 U.S. 562

(1972) ___________________________ ________ ...._. 25

Franks V. Bowman Transp. Co., 44 U.S.L.W.

4356 (U.S. 1976) .................. ............... ......_ .... . 25n

Gaston County y. United States, 395 U.S. 285

(1969) ___________________________ ___________ _ 27n

Gautreaux V. City of Chicago, 480 F.2d 210 (7th

Cir. 1973) ___________________ 33n

Gilmore V. City of Montgomery, 417 U.S. 556

(1974) ................. 27n

Griffin V. County School Board, 377 U.S. 218

(1964) ................... .............................. ...................17n, 33n

Haney V. County Bd. of Educ., 429 F. 2d 364 (8th

Cir. 1971) .............................................. ................. 33n

Hans V. Louisiana, 134 U.S. 1 (1890) ...........19, 40, 43, la

Hills V. Gautreaux, 425 U.S. 284 (1976)_______ 31,33,46

Jagnandan v. Giles, 538 F.2d 1166 (5th Cir.

1976), petition for cert, pending, No. 76-832.... 3a

Katzenbach V. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966)_____ 41n

Keyes V. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189

(1973) ................................. ...................................... 25n

Keyes V. School District, 521 F. 2d 465 (10th Cir.

1975), cert, denied, 44 U.S.L.W. 3399 (U.S.

Jan. 12, 1976) ............................. ........................ . 16,29

Langnes V. Green, 282 U.S. 531 (1931)______ 8n, 23, 38n

Lee V. Macon County Board of Educ., 267 F.Supp.

458 (M.D. Ala. 1967) 317 F.Supp. 103 (M.D.

Ala. 1970) ______________ 27n

Lindheimer v. Illinois Bell Telephone Co., 292

U.S. 151 (1934) .................................................. 8n

Lynch v. Household Finance Corp., 405 U.S. 538

(1972) __________ 7a

Minnesota State Senate V. Reems, 406 U.S. 187

(1972) ................................. 45n

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

VI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

Mitchum V. Foster, 408 U.S. 225 (1971)................. 7a

Monroe V. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961)--------- 2a, 4a, 5a-6a

Morgan V. Kerrigan, 401 F.Supp. 216 (D. Mass.

1975), aff’d, 530 F.2d 401 (1st Cir. 1976).....27n, 36n,

41n

Mt. Healthy City School District V. Doyle, 45

U.S.L.W. 4081 (U.S. Jan. 11, 1977)..3, 24n, 43, 5a, 7a

National League of Cities V. Usery, 49 L.Ed.2d

245 (1976) ______________ --3 ,4 ,3 1 -3 3 ,4 3

North Carolina V. Swann, 402 U.S. 43 (1971)___ 33n

Oliver V. Kalamazoo Board of Education, --------

F.Supp. ------ (W.D. Mich. Nov. 5, 1976), ap

peal pending __________________ 41-42

Plaquemines Parish School Bd. V. United States,

415 F.2d 817 (5th Cir. 1969)________________ 27n

Porter V. Warner Holding Co., 328 U.S. 395

(1946) .................... 25

Reagan V. Farmers Loan & Trust Co., 154 U.S.

362 (1884) ______________ ___ _____ -____ ______ 42

Rizzo V. Goode, 423 U.S. 362 (1976)__________ 31, 32, 33

Rogers V. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965)-................. . 27n

Soni V. Board of Trustees, 513 F.2d 347 (6th

Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 44 U.S.L.W. 3702 (U.S.

June 7, 1976) ________________________________ 41, 42

Steffel V. Thompson, 415 U.S. 452 (1974)_______ 7a

Strauder V. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880)— 7a

Story Parchment Co. v. Patterson Paper Co., 282

U.S. 555 (1931)____ __ ____________ ___ ______ 25n

Swann V. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) _______ ____ ___15, 25, 26, 27n, 45n

United States V. American Ry Express Co., 265

U.S. 425 (1924)______ __ ____________________ 8n, 23

United States V. Duke, 332 F.2d 759 (5th Cir.

1964) ___________________ __________ ____ ____ _ 33n

United States V. E.I. Dupont de Neumours Co.,

366 U.S. 316 (1961).............................................. 25n

United States V. Greenwood Municipal School Dis

trict, 406 F.2d 1086 (5th Cir. 1969) 33n

VII

United States V. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ.,

372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1967)________________ 27n

United States V. Louisiana, 380 U.S. 145 (1065) - 25

United States V. Mississippi, 339 F.2d 679 (5th

Cir. 1964) ________________ ___ _____ _________ _ 33n

United States V. Missouri, 523 F.2d 885 (8th Cir.

1975) ____________ __ ____ _____________ _______ 27n

United States V. Schooner Peggy, 1 C'ranch 103

(1801) ___________________ _________ _____ ______ 40

United States V. Scotland Neck, 407 U.S. 484

(1972) __________________________________ _____ 33li

United States V. Texas, 330 F.Supp. 235 (E.D.

Tex. 1971) ___________________________ ____ ___ 27n

Usery v. Allegheny County Institution Dist., No.

76-1079 (3d Cir. Oct. 28, 1976) ____________ ___ 7a-8a

Wright V. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S.

451 (1972) .................................................... .........27n, 33n

Whitcomb V. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971)_______ 45n

Zenith V. Hazeltine, 395 U.S. 100 (1969)........ ..... 25n

Zwickler v. Koota, 389 U.S. 241 (1967)__________ 7a

TABLE OP AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

Statutes, Rules and Regulations

Emergency School Aid Act, 20 U.S.C. §§ 1601

and 1606(a) ____________ _______________ 1 In, 27-28

20 U.S.C. § 881 (k) .. 19,39

Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974__ 14n, 28n,

39, 40, 3a

20 U.S.C'. §1702

20 U.S.C. § 1703

20 U.S.C. §1706

20 U.S.C. § 1708

20 U.S.C. §1720

___ 41n

19,39,40n

19, 39, 40n

39

...... 19,39

28 U.S.C. § 455(a) .

28 U.S.C. § 1292(b)

28 U.S.C. §1331.....

________ 12n

- ................ ................. 8

19, 42, 2a, 3a, 7a

VIII

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

28 U.S.C. § 1343.............-.................................— 3a, 4a, 5an

42 U.S.C. § 1983 .....................................— 19, 42, 2a, 3a-6a

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000c-2 and c-4......................... .........- l l n , 28

Mich. Stat. A n n . § 15.1023(7) ............................ - 41

Act 48 of Michigan Public Acts of 1970.......... ....... 5

Canon 3A, ABA Code of Judicial Conduct----------- 12n

Rule 54 (b ), Fed. R. Civ. P........ -.............................- 8

Rule 12(h) (1 ), Fed. R. Civ. P.............. .................... 5an

Supreme Court Rule 23(1) (c) ................................ 45n

Supreme Court Rule 40 (1) (d) (2) .......... ....... .....- 49n

45 C.F.R., Part 180 ............................. ........................ 28

45 C.F.R., Part 185 „ ...........-.............. -........ ............... lln , 28

Other Authorities

W. Prosser, Law of Torts (4th ed. 1971)..... ....... 45

The Supreme Court, 1975 Term, 90 HARV. L. Rev.

56 (1976) ........................... ................................ -..... 32

Stern, When To Cross-Appeal or Cross-Petition,

87 Harv. L. Rev. 763 (1974)___________ ______ 8n

B. Schwartz, Statutory H istory of the United

States: Civil Rights (1970)................ —.......— 2a

In T he

|§upron£ (Emirt sit t!|? Imtfb States

October T erm , 1976

No. 76-447

W illiam G. Milliken , et al.,

Petitioners,

— v.-

R onald Bradley, et al.,

Respondents.

BRIEF FOR BRADLEY RESPONDENTS

COUNTER-STATEMENT OF QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Given the de jure segregation of the Detroit Public

Schools, did the courts below have the equitable authority

to include such ancillary administrative and educational

relief in the desegregation remedy as was shown neces

sary to begin to eliminate the continuing effects of the

segregation violation and to assure the transition to and

maintenance of a racially non-discriminatory school dis

trict?

2. Do constitutional principles of federalism, the

tenth amendment, or the eleventh amendment shield

State defendants, who have previously been adjudicated

to have contributed substantially to the de jure segrega

tion of the Detroit Public Schools, from participating

generally in implementing appropriate ancillary relief?

2

3. Does the eleventh amendment particularly bar the

State defendants from sharing in the fiscal consequences

of implementing such prospective relief?

4. Assuming arguendo the equitable authority and

constitutional power, did the courts below properly exer

cise their equitable discretion in ordering such relief

against State defendants in the particular circumstances

of this case?

CONSTITUTIONAL, STATUTORY, AND

REGULATORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The pertinent provisions of the Constitution, statutes,

and regulations involved are reprinted in Appendix B

attached hereto. They include the tenth, eleventh, and

fourteenth amendments to the Constitution; 20 U.S.C.

§§1601 and 1606(a); 20 U.S.C. §§ 1702(b), 1703(a),

(b), (f) , 1706, 1708, 1720(a); 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331, 1343

(3) and (4) ; 42 U.S.C. § 1983; 42 U.S.C. §§ 20Q0c-2 and

c-4; 45 C.F.R. §§180.12, .31, .41; 45 C.F.R. §§185.01

and .12.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Introduction

As this Court knows, the Detroit school case has not

heretofore been marked by procedural simplicity nor gen

eral agreement on the controlling constitutional or equi

table principles. See, e.g., Bradley v. Milliken, 484 F.2d

215 (6th Cir., 1973) (en banc), rev’d in part sub nom.

Milliken v. Bradley, 484 U.S. 717 (1974) (opinion of

Burger, C.J., for the Court), 753 (Stewart, J., separate

concurring opinion), 757 (Douglas, J., dissenting), 762

(White, J., dissenting), 781 (Marshall, J., dissenting).

The remedial proceedings in the district court following

this Court’s remand in Milliken for elimination of the

de jure segregation within the Detroit Public Schools can

only be characterized as procedurally flawed and, in sev

3

eral respects, substantively bizarre. Fortunately, the

Court of Appeals, despite its express misgivings with the

limitations set in Milliken (PA 5a-6a and 151a-152a,

158a n. 3), has acted to reverse the substantive errors

and has remanded for further proceedings (PA 182a).*

Among the numerous parties, only the State defend

ants have petitioned this Court to review any portion of

the judgment of the Court of Appeals, and then only

with respect to the requirement that they pay a share of

the costs of four aspects of desegregation relief ancillary

to pupil reassignments. Without unduly belaboring the

prior history and record in this cause, we believe that a

review of the case will show that the State Petitioners

present considerably narrower equitable and constitu

tional issues than their rhetoric would admit.

Moreover, such review will provide grounds for this

Court to find substantial, if not unanimous, agreement

with the judgment of the Court of Appeals, without

reaching the monumental constitutional issues expressly

left open in Ex parte Young, Edelman v. Jordan, Na

tional League of Cities v. Usery, Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer,

and Mt. Healthy City School District v. Doyle. Notwith

standing the representations of State Petitioners and

their amici curiae friends, this is not the case for the

Court to decide either to rend or to mend the very fabric

* The opinions and orders contained in the Appendix to the Peti

tion for Certiorari will be cited in the form, for example, PA 151a;

reference to prior opinions will be to the official reports, e.g., 484

F.2d 215 or 418 U.S. 717. Reference to record materials contained

in the joint appendix will be in the form A 53. Reference to other

record evidence will be in the following form : e.g., VPX 3 and 22

VTr 2506 for plaintiffs’ exhibit 3 and volume 22, page 2506, of the

transcribed testimony from the 1972 violation hearings; MTr 35

and MSX 5 for page 35 of the transcribed testimony and State

defendants’ exhibit 5 from the 1973 remedy hearings on Detroit-

only and metropolitan plans; and RTr 5/20/75 at 65 for page 65

of the testimony transcribed on May 20, 1975, during the 1975

remedy hearings on remand from Milliken.

4

of the Constitutional Union with respect to the claim of

State sovereignty. To put the point somewhat differ

ently, a review of the prior proceedings will show that

this is not the case by which to determine under our

Constitution whether “the States [have been denigrated]

to a role comparable to the departments of France” rela

tive to the enumerated National powers, Elrod v. Burns,

49 L.Ed.2d 547, 567 (1976) (Burger, C.J., dissenting),

or whether the States have recently been promoted to

sovereignty virtually as complete as that of France it

self, even on matters specifically delegated by the Con

stitution to the previously supreme authority of the Fed

eral government. See National League of Cities v. Usery,

49 L.Ed.2d 295, 260-74 (Brennan, J., dissenting).

B. The Pre-Milliken Proceedings

Plaintiffs Ronald Bradley, et al., Detroit school chil

dren and their parents, filed their Complaint on August

18, 1970, against the Superintendent and Board members

of the Detroit Public Schools and against the State Board

of Education, Superintendent of Public Instruction, At

torney General, and Governor.1 Plaintiffs alleged that

defendants and their predecessors in office acted with the

purpose and effect to foster and to maintain a de jure

segregated public school system and denied plaintiffs

equal educational opportunities along racial lines. Plain

tiffs prayed for complete relief from these unconstitu

tional practices including, inter alia, complete desegrega

tion; elimination of the racial identity of every school in

all respects; maintenance now and hereafter of a uni

tary, racially non-discriminatory school system; and such

1 Prior to the evidentiary hearings on violation, the Detroit Fed

eration of Teachers and a white citizens’ group intervened as parties

defendant. During the remedial hearings following the violation

findings, the Treasurer of the State of Michigan was joined as a

party defendant and various suburban school districts were per

mitted to intervene as parties defendant.

5

further relief as would appear to the district court to

be equitable and just. See Complaint.

During preliminary proceedings and appeals, portions

of Act 48 of Michigan Public Acts of 1970 were declared

unconstitutional because they obstructed and nullified a

partial, voluntary high school desegregation plan adopted

by the Detroit Board and “had as their purpose and

effect the maintenance of segregation.” 343 F. Supp. 582,

589 (1972) ; 433 F.2d 897 (1970). Upon direction from

the Court of Appeals, 438 F.2d 945 (1971), evidentiary

hearings on the merits began in the district court on

April 6, 1971, and continued for forty-one trial days

through July 22, 1971. Plaintiffs introduced substantial

evidence to show not only the pervasive and long-standing

de jure segregation of pupils, but also racial discrimina

tion in other aspects of schooling, including faculty and

staff assignment and the allocation of educational re

sources. Plaintiffs also introduced substantial evidence

of the harmful consequences of all these racially discrim

inatory practices and conditions on the educational oppor

tunities currently enjoyed by black pupils.2

2 See, e.g., VPX 3 at 72-134, VPX 107 at 294-98, VPX 177-78,

VPX 154C, YPX 161-66, VJXFFFF, 15 VTr 1611-21, 16 VTr 1805-

10, 20 VTr 2:180-86, 22 VTr 2506-18, 38 Tr. 4340 (faculty and staff

segregation) ; 8-9 VTr passim, 16 VTr 1779-91, 37 VTr 4148-56, 41

VTr 4665-66, 41 VTr 4677-78, VPX 107 at 298, VPX 134, VPX 161-

64, VDX NNN (allocation of educational resources and opportuni

ties along racial lines and harmful effects of segregated schooling

on the pupils). In summary, plaintiffs’ proof showed that the racial

composition of faculty and staff still mirrored the racial composition

of student bodies; through 1955 the Detroit Board never assigned

black teachers to majority white schools; and through 1965, the

Board assigned black teachers to predominantly white schools only

if acceptable to that particular school community. Plaintiffs’ proof

also showed that educational resources were allocated in a pattern

of “ systematic differentiation parelleling racial lines” 41 VTr less

ee. Thus, for example, substantially more emergency substitutes

and inexperienced teachers were assigned to black schools than to

white; and the average teacher salary in black schools was $1,400

to $1,800 less than in white schools, VPX 161-64. Finally, plain

6

On September 27, 1971, the district court, Hon. Stephen

J. Roth sitting, issued its opinion on violation. 338 F.

Supp. 582. The court found that both State and local

defendants, as well as the State of Michigan, acted di

rectly, jointly and severally through a variety of tradi

tional segregation practices “with a purpose of segrega

tion” to create and to aggravate the then current condi

tion of almost total segregation of pupils. 338 F. Supp.

at 587-89, 592. The district court, however, rejected the

similar allegations and evidence with respect to faculty

and staff assignments, 338 F. Supp. at 589-91, and made

no findings with respect to the proof of racial discrimi

nation in the allocation of educational resources and

opportunities and the harmful effects on the pupils of

the de jure segregation. On October 4, and November 5,

1971, the court ordered the State and local defendants to

submit Detroit-only and area-wide plans to remedy the

de jure segregation found.3

At the evidentiary hearings in March and April, 1972,

on the Detroit-only and area-wide plans, the district court

received substantial evidence from all parties on the need

for relief ancillary to pupil desegregation. The evidence

on such ancillary relief supported, inter alia, faculty and

staff desegregation; elimination of racial discrimination

tiffs proof showed the harmful and stigmatizing consequences of the

pervasive racial discrimination on “ the hearts and minds’’ (Brown

v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483, 493-94 (1954)) of the pupils and

the educational opportunities of black pupils, including particularly

with respect to reading. E.g., 8 YTr 863-86, 895, 920-21, 935-40,

950-69 ; 9 VTr 960; VPX 134.

3 The Detroit Board and State defendants filed notices of appeal

from this order and the violation opinion. Plaintiffs filed a protec

tive cross-appeal and a motion to dismiss these appeals because the

order and opinion were not “ final,” adjudicated no substantial rights

of the parties, and represented no “ judgment” from which to per

mit appellate review. On February 23, 1972, the Court of Appeals

dismissed the appeals because there was “ no final order from which

an appeal may be taken.” 468 F.2d 902, 903, cert, denied, 409 U.S.

844.

7

in school facilities and other educational resources; elimi

nation of racial discrimination from curriculum, tests,

programs, and counseling services; multi-racial and

remedial curriculum; and in-service training for faculty

and other staff. No party, including State defendants,

presented any contrary evidence on the need for such

ancillary relief as a part of implementing desegregation

relief.4

In its June 14, 1972, opinion in support of “ Ruling

on Desegregation Area and Development of Plans” re

quiring area-wide relief extending beyond the Detroit

School District, the district court made findings concern

ing the harmful consequences of de jure segregation on

the school children and the need for restructuring facili

ties and reassigning staff incident to pupil reassignment,

345 F. Supp. 914, 921, 931-33. The court entered appro

priate school equalization and staff desegregation orders

“so as to prevent the creation or continuation of [racial]

identification of schools by reference to past racial com

position.” 345 F. Supp. at 919. Citing the “uncontro

verted evidence” received, the court also found that the

“following additional factors are essential to implemen

tation and operation of an effective plan of desegrega

tion,” including, inter alia, multi-racial and other cur

riculum reforms, in-service training for faculty and staff,

and nondiscriminatory testing and counseling designed to

overcome the effects of de jure segregation and residual

racial discrimination. 345 F. Supp. at 935-36. In its

order, the court included specific provisions for such an

cillary relief “to insure the effective desegregation of the

schools . . .” 345 F. Supp. at 919.

4 See, e.g., MTr 35-36, 312, 353, 404-07, 470-71, 495-96, 586-87,

782, 1342-43; MSX 5, 8, 10; MPX 2. Some of the added suburban

defendants, and one of the State Board plans (MSX 8), however,

proposed equalizing education opportunities as an adequate substi

tute for pupil desegregation. See 345 F. Supp. 914, 921 n.l.

8

Subsequently, on July 20, 1972, the district court made

these rulings and orders final pursuant to Rule 54(b),

Fed. R. Civ. P., and appealable pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

§ 1292(b). The State, Detroit Board, and intervening

suburban school district defendants appealed.5 These

appeals focused on the de jure segregation violation find

ings and the propriety of the area-wide pupil desegrega

tion relief ordered. The Court of Appeals, sitting en

bane, basically affirmed the judgment of the district court

but vacated and remanded to provide all potentially af

fected suburban school districts with the opportunity to

be heard. 484 F.2d 215 (1973).

The State and intervening suburban school district

defendants petitioned this Court to review the violation

findings against the State defendants and/or the pro

priety of ordering area-wide relief based upon findings

of de jure segregation within the Detroit School District.

Upon reviewing the judgment of the Court of Appeals,

this Court, on July 25, 1974, reversed that portion of

the judgment permitting inter-district relief based on

violation findings that State and Detroit defendants

caused de jure segregation within the Detroit School Dis

5 Plaintiffs did not cross-appeal because the “ final” order grant

ing relief (in contrast to some of the particular findings and rea

soning) provided all relief prayed for in their initial complaint

and supported by their evidence: pupil desegregation, faculty and

staff desegregation, and other ancillary relief designed to overcome

the harmful effects of de jure segregation on the children, to avoid

racially discriminatory provision of education opportunities, and

otherwise to assure the effective transition to and maintenance of

a unitary, racially non-discriminatory school system. Being a pre

vailing party entirely satisfied with the “ final” judgment, plaintiffs

could not appeal to review findings of fact or interim rulings they

did not like, Lindheimer v. Illinois Bell Telephone Co., 292 U.S.

151, 176 (1934), and did not need to appeal to preserve their right

to argue any ground in support of the judgment. Dandridge v. Wil

liams, 397 U.S. 471, 475-76 n.6 (1970) ; Langnes v. Green, 282 U.S.

531, 535-59 (1931); United States v. American Ry. Express Co.,

265 U.S. 425, 435-36 (1924). See generally, Stern, When to Cross-

Appeal or Cross-Petition, 87 Harv. L. Rev. 763 (1974).

9

trict, 418 U.S. at 745-53; provided guidelines for and

examples of area-wide and boundary violations necessary

to support interdistrict relief, 418 U.S. at 744-45; and

remanded for “prompt formulation of a decree directed

to eliminating the segregation found to exist in Detroit

City schools,” 418 U.S. at 753.

C. The Post-Milliken Proceedings in the District Court

The State Petitioners suggest (Brief at 18-19) that

plaintiffs and their experts either opposed or did not

support, in the courts below, the ancillary relief here at

issue. This misrepresents plaintiffs’ position in the courts

below and the testimony of their experts in the district

court. It also misconceives the dynamics of the remand

proceedings following Milliken. For throughout the re

mand proceedings, plaintiffs and their experts supported

such ancillary relief as a proper adjunct to the primary

relief of actual pupil desegregation where necessary to

remedy the continuing harm resulting from the segrega

tion violation and to insure the transition to and mainte

nance of a racially non-discriminatory system of school

ing. Plaintiffs, however, were repeatedly forced to focus

the attention of the defendants and the district court on

the primary desegregation remedy lest it be limited by

the apparent preoccupation with ancillary relief and re

lated financial concerns. Only with this understanding

of the context may the remand proceedings be fairly

understood.

Following the death of District Judge Roth on July

11, 1974, the case was assigned to District Judge Robert

E. DeMascio for remand proceedings consistent with

Milliken. Pursuant to the district court’s order, the De

troit Board and plaintiffs submitted pupil reassignment

plans in Spring, 1975:6 The Detroit Board plan operated

6 On April 16, 1975, the district court “granted the motions to

dismiss filed by the intervening suburban defendants and simul

taneously granted plaintiffs’ motion to amend their complaint to in

10

on the novel premise that only identifiably white schools

need be “desegregated,” thus proposing to maintain over

100 de jure segregated, all-black schools. The Detroit

Board plan also included extensive discussion, without

documentation but with “excessive” (PA 13a) cost esti

mates, of purportedly necessary ancillary relief.

On April 20, 1975, the State defendants submitted a

“critique” of the Detroit Board’s plan which queried

whether any ancillary relief was appropriate but con

ceded that several aspects of the proposed relief (includ

ing in-service training of staff and non-discriminatory

guidance, counseling, and curriculum) “deserve special

emphasis in connection with implementation of a deseg

regation plan.” Critique at 39, 50. Evidentiary hearings

on the plans submitted and ancillary relief continued

from April 29 through June 27, 1975J Substantial evi- 7

clude allegations of inter-district de jure violations.” PA 13a. Sub

sequently, plaintiffs filed their second amended complaint alleging

general causes of action for inter-district relief under Milliken.

Proceedings on a more definite, third amended complaint have been

stayed pending conclusion of the remand proceedings on Detroit-

only remedy and of a cost dispute between the parties. See 411 F.

Supp. 937; PA 168a.

7 During these hearings, plaintiffs moved the court to order

acquisition of 150 school buses, the minimum number necessary to

implement either pupil reassignment plan. By order of May 21,

1975, the district court ordered the State defendants to acquire

the buses. PA la-2a. On expedited appeal, the Court of Appeals

affirmed this order with the modification that the Detroit Board

acquire the buses, with the State defendants to bear 75% of the

cost. PA 3a-5a, 519 F.2d 679, cert, denied, 423 U.S. 930 (1975).

This modification was made pursuant to State defendants’ repre

sentations of their willingness to conform to that procedure con

sistent with State practice. PA 4a. The district court subsequently

followed this modified procedure and formula for sharing the costs

in ordering the acquisition of 100 additional school buses. PA 161a

n.4. It should also be noted, however, that the Court of Appeals

specifically directed that State defendants take all necessary steps,

including utilizing existing funds already allocated, or to be allo

cated, and reallocating existing or new funds, to pay or reimburse

the State’s share of such transportation acquisition. PA 5a. The

11

dence was introduced showing the real need for the an

cillary relief here at issue—in-service training of staff,

non-discriminatory testing, guidance and counseling, and

remedial reading—to eliminate the continuing effects of

the de jure segregation and discrimination and to insure

the effective transition to non-discriminatory schooling.

See, e.g., A 7-9, 30-42, 51-61, 67-68, 72-82, 86-89; RTr

5/8/75 at 24, 66, 95-100; RTr 5/9/75 at 61-62, 72-75;

RTr 5/15/75 at 42-49; RTr 5/20/75 at 127; RTr 6 /12 /

75 at 116-17.8

On August 15, 1975, the district judge issued his opin

ion on remedy. He held that ancillary relief was appro

priate and would be ordered only to the extent necessary

to overcome the continuing, harmful effects of the viola

tion, to remedy continuing racial discrimination in edu

cational opportunities, or to insure the successful imple

mentation of a non-discriminatory plan of pupil desegre

gation (PA 13a, 35a-37a, 55a, 64a-74a, 78a-79a, 81a-

82a). However, the district judge rejected the constitu

tional requirement that the plan of pupil reassignments

must itself eliminate the primary pupil segregation vio

State defendants concede the propriety of their sharing in these

costs, did not seek review from these orders, and do not ask this

Court to review these orders as part of this appeal. See State Peti

tioners’ Brief at 8 and n.6.

8 The State Petitioners’ suggestion (Brief at 18) that plaintiffs’

experts were of the opinion that no ancillary relief was necessary

to remedy the de jure pupil segregation is incredible. The testimony

of Drs. Foster and Stolee, only some of which is cited above, was

that the four aspects of ancillary relief here at issue were essential

to an effective pupil desegregation remedy and were regularly in

cluded by school districts throughout the country as necessary

components in implementing pupil desegregation plans. As the

former and current directors of the University of Miami Title IV

School Desegregation Center, they had personal knowledge of these

facts; for they have assisted literally hundreds of school districts

in implementing pupil desegregation plans pursuant to their man

dates from Congress and HEW, and federal funding. See, e.g., 42

U.S.C. § 2000c-4(a), 20 U.S.C. § 1606(a), and 45 C.F.R. §185.

12

lation found. Thus, the district court adopted the thesis

that only racially identifiable white schools need be elimi

nated, and rejected even the Detroit Board’s limiting

pupil reassignment plan because it accomplished too much

desegregation (PA 51a-52a, 61a). The district court

simultaneously issued a Partial Judgment and Order

denying the relief requested in plaintiffs’ pupil desegre

gation plan and establishing guidelines and a timetable

for further planning and submission of a revised plan

by the Detroit Board.9

Plaintiffs filed their notice of appeal, a stay applica

tion, and a motion seeking summary reversal of the dis

trict court’s rejection of their plan. Plaintiffs particu

larly challenged the premise that pupil reassignments

need not be extended to black schools, which thereby ex

cluded from desegregation over 100 all-black schools in

the three administrative regions of the school district at

9 The district judge in his August 15, 1975, opinion and appendices

noted that he had proceeded ex parte and entirely outside the record

with meetings and communications with defendant parties, court

experts, and non-parties to make specific fact findings and to

marshall support throughout the State for “his plan” prior to its

entry. See, e.g., Appendices A-G to the district court’s August 15,

1975, opinion and PA 13a, 15a, 50a-51a. After the August 15,

1975, opinion, the district judge’s non-judicial conduct became,

if anything, even more openly the rule than the exception. These

extraordinary ex parte contacts with the defendants and non-parties

were rationalized by the district court as “ reflect [ing] the fact that

the adversarial phase of this litigation has ended” (PA 116a n.2),

despite plaintiffs’ specific request for a hearing to present evidence

on their objections to the revised plans submitted by the Detroit

Board pursuant to the August 15 guidelines. (Plaintiffs have pend

ing a motion to recuse the district judge for cause under 28 U.S.C.

§455 (a) because, inter alia, of such repeated violations of Canon

3A of the ABA Code of Judicial Conduct.)

[Note: After the preparation of this brief for the printer, the

district judge, on January 21, 1977, entered an order denying plain

tiffs’ motion to recuse, except with respect to further proceedings

on the faculty segregation issue; on that issue, the district judge

referred questions about his impartialty for decision by the Chief

Judge of the Eastern District of Michigan.]

13

the very heart of the de jure violation. These matters

were taken under advisement by the Court of Appeals

and a briefing schedule set on all appeals.10

On October 16 and October 29, the district court

issued orders concerning a monitoring commission to be

implemented by State defendants and a uniform code of

student conduct to be implemented in conjunction with

the new pupil desegregation plan. On November 4, 1975,

the district court entered a memorandum and order ap

proving with modification the revised pupil reassignment

plan submitted by the Detroit Board. On November 10,

1975, the district court issued an order concerning mag

net vocational schools. On November 20, 1975, the dis

trict court entered a judgment ordering the Detroit

Board to implement these plans. During the Fall, the

Detroit Board also submitted revised proposals for each

aspect of ancillary relief authorized in the district court’s

August 15 opinion and order; however, no hearings were

held and no record was made on these submissions. See

note 9, supra; and State Petitioners’ Brief at 11 n.7.

On May 11, 1976, while the various appeals of the

plaintiffs, Detroit Board, and Teacher Federation were

still pending in the Court of Appeals, the district court

filed a memorandum, order, and final judgment on magnet

10 Plaintiffs, as well as the Detroit Board and the intervening

Detroit Federation of Teachers, also appealed from the district

court’s August 28, 1975, order requiring in each school no more

than 70% faculty of either race. Cf. PA 83. Plaintiffs believed

that this order could serve to maintain the continuing racial identi-

fiability (e.g., RDX 6) of schools solely by reference to staff racial

composition. (Plaintiffs thus appealed from the first judgment or

order which denied them complete faculty relief. Contrast note 5,

supra, with State Petitioners’ Brief at 9.) The Detroit Board appeal

argued that it should be allowed to implement complete faculty de

segregation as it had requested, while the Detroit Federation of

Teachers argued that the district court was without authority to

order any faculty desegregation.

14

vocational centers,11 uniform code of student conduct, re

medial reading, in-service training, counseling and ca

reer guidance, testing, and school-community relations.

PA 115a-150a. Adhering to the view expressed in its

August 15, 1975 opinion, the district court was “ careful

to order only what is essential for a school district un

dergoing desegregation. . . [T] he court has examined

every detail in each proposal to ensure that the com

ponents we order are necessary to repair the effects of

past segregation, assure a successful desegregation effort

and minimize the possibility of resegregation.” (PA

117a). With respect to each component of ancillary re

lief, the district court made specific findings of their

necessity under these standards. PA 127a (reading),

128a (in-service training), 129a (counseling and career

guidance), 130a (testing).

The State defendants and Detroit Board appealed this

judgment insofar as it required the State defendants

and Detroit Board to “equally bear the burdens” of the

“ excess cost imposed by the provision” (PA 146a-147a)

requiring these defendants jointly to implement the an

cillary desegregation relief of remedial reading, in-service

training, testing, and counseling and career guidance.

D. The Judgment of the Court of Appeals

In resolving the numerous appeals and cross-appeals

of the parties, the Court of Appeals affirmed, modified,

reversed, and vacated various parts of the district court’s

orders, remanding for further proceedings not inconsis

tent with its opinion. In summary, the Court of Appeals

11 The district court apparently resolved the sharing of costs

and administration of these magnet vocational centers to the satis

faction of the State defendants and the Detroit Board. PA 117a-

119a. Contrary to State Petitioners’ suggestion (Brief at 12 n.8),

however, there can be no question that this was an aspect of desegre

gation relief, both direct and ancillary. Compare PA 76a-78a,

118a, n.5 with 20 U.S.C. ■§§ 1701 et seq.

15

held that the defendant school authorities and the district

court totally failed to justify the exclusion of over 100

all-black schools in three administrative regions from the

pupil reassignment plan. As these schools and regions

were among those “most affected by the acts of de jure

segregation” (PA 163a), the Court of Appeals held that

under Swann v. Charlotte Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

402 U.S. 1, 26 (1971), defendants bore the burden of

justifying their maintenance as one-race schools; and

that they had totally failed to explain the continuation

of such de jure segregation (PA 163a-164a). The Court

of Appeals affirmed the other portions of the plan for

pupil reassignments (PA 167a) and affirmed the equita

ble authority of the district court to order staff desegre

gation (but vacated for the hearing of additional evi

dence on the issue (PA 181a-182a)). No party seeks

review of these judgments in this Court.

With respect to the issues concerning the four particu

lar “ educational components” before this Court for re

view, the Court of Appeals held that the district court’s

findings of fact concerning their necessity as essential

parts of an effective remedy providing complete relief

were “not clearly erroneous, but to the contrary [were]

supported by ample evidence.” PA 170a. After review

ing the record and the precise claims of error presented

by the parties, the Court of Appeals held that the in-

service and testing components were essential to insure

that staff can “work effectively in a desegregated envir

onment” and that “ students are not evaluated unequally

because of built-in bias in the tests administered in for

merly segregated schools.” PA 170a. Similarly, the Court

of Appeals “agree[d] with the District Court that the

reading and counseling programs are essential to the

effort to combat the effects of segregation.” PA 170a.

The Court of Appeals concluded (PA 171a) :

[T]he findings of the District Court as to the Edu

cational Components are supported by the record.

16

This is not a situation where the District Court

“ appears to have acted solely according to its own

notions of good educational policy unrelated to the

demands of the Constitution.” See, Keyes v. School

District, 521 F.2d 465, 483 (10th Cir. 1975), cert,

denied, 44 U.S.L.W. 3399 (U.S. Jan. 12, 1976).

The Court of Appeals also rejected State defendants’

claim of immunity from sharing in the actual costs of

implementing this ancillary relief. In essence, the Court

of Appeals held that the order requiring State defend

ants to bear a share of the costs of implementation was

in form and in actual effect an ancillary consequence of

implementing prospective injunctive relief and, under

Edelman v. Jordan, was therefore not barred. PA 172a-

178a. Reviewing the State defendants’ substantial con

tribution “ to the unlawful de jure segregation that

exists” in the Detroit Public Schools, the State defend

ants’ sharing in other costs incident to pupil desegrega

tion (e.g., acquisition of buses and construction of mag

net vocational centers), and the relative resources of the

State and local defendants, the Court of Appeals found

no abuse of discretion in the district court’s order re

quiring the State and local defendants to share equally

in the cost of implementing ancillary relief. PA 178a-

180a.12

12 The Court of Appeals added:

Our affirmance of the District Court on this issue is not in

tended as a mandate for a cutback in essential educational

programs [in the Detroit Public Schools] in order to meet the

expenses of implementing the desegregation plan. We affirm

that part of the judgment relating to the costs of the plan,

but without prejudice to the right of the District Court to

require a larger proportional payment by the State . . . if

found to be required by future developments.

PA 180a (emphasis added). Yet the State defendants claim that it

is just this supposed “ judicially decreed blank check, to be filled in

and drawn upon the Treasury of the State . . . to pay for court-

ordered educational program expansion, that is before this Court for

review.” State Petitioners’ Brief at 17. Such hyperbole does not fit

17

Following Justice Stewart’s denial of the State de

fendants’ application for a stay on September 1, 1978,

the defendant State Treasurer paid over to the Detroit

Board the State defendants’ share of the projected im

plementation costs of ancillary relief. On November 15,

1976, this Court granted State defendants’ petition for

writ of certiorari to review the judgment of the Court

of Appeals concerning the propriety of ancillary relief

and the State defendants’ sharing in the cost burdens of

its implementation.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Plaintiffs appear as Respondents in this Court to de

fend the judgment of the Court of Appeals on several

alternative grounds, some of which were not considered

or relied upon by the courts below. Pursuant to the set

tled practice of this Court, we do this to assist review

of a judgment which is correct and raises neither the

spectre nor the issue of destroying any sovereignty en

joyed by the State Petitioners under present interpreta

tions of the Constitution and laws of the United States.

Contrary to the State Petitioners’ claim that the judg

the actual judgment which is before this Court for review. First,

this supposed “judicial decree [sic]" is mere obiter dictum con

cerning some possible hypothetical “ future developments” which

have not yet occurred and, therefore, have not yet been fully

plumbed by the record nor made the subject of any injunction,

order, or decree. Second, no “blank check” for any “court-ordered

educational program expansion” was contemplated by the Court of

Appeals; to the contrary, only a portion of the “ excess costs,” the

actual increase in costs from present programs incident to imple

mentation of ancillary relief necessary to remedy the violation,

was approved by the Court of Appeals. There will be time enough

to argue this supposed “blank check” issue if the dictum is ever

reduced to an order. Upon, a proper showing, however, we have no

doubt that there is substantial support for the proposition that

educational services may not be substantially reduced as a result

of desegregation, at least during the transition to a unitary system

of schooling. See, e.g., Griffin V. Prince Edward County School Board,

377 U.S. 218 (1964) and Adams v. Rankin County Board of Edu

cation, 485 F.2d 324, 327-28 (5th Cir. 1973).

18

ment below constitutes a federal judicial raid on the

State treasury, the issues actually raised although impor

tant are much narrower and discrete. (See Introduction,

pp. 21-23, infra).

1. For purposes of analysis, we first address the is

sue of plaintiffs’ right to relief ancillary to actual pupil

reassignments wholly apart from any order compelling

State Petitioners to participate in such relief. A review

of prior decisions and the record, including the State

defendants’ representations to the district court, shows

that non-discriminatory testing and counseling, in-service

training, and remedial reading are necessary and justi

fied in this case to overcome the continuing consequences

of the long-standing and pervasive de jure segregation

violation and to assure a smooth transition now and ef

fective maintenance hereafter of a racially non-discrimi

natory public school system. Thus, the State Petitioners

entirely misconceive the need for an independent “edu

cational” violation as a prerequisite for ordering such

relief as an adjunct to pupil desegregation. (See Argu

ment I, pp. 24-29, infra.)

2. Assuming arguendo that the ancillary relief or

dered is proper, we next consider the issue of federal

judicial power to compel responsible State officials to

participate in providing such relief generally, without

regard to the particular money consequences. A review

of the prior decisions and the record will show that the

courts below had the constitutional power—notwithstand

ing principles of federalism, and the tenth and eleventh

amendments— to order the State Petitioners as active

constitutional tort-feasors in the de jure violation to

participate in implementing relief. State Petitioners may

be ordered to take action beyond or in derogation of

their authority and duty under State law in order to

effectuate relief. (See Argument II, pp. 30-34, infra.)

3. We then examine directly whether State Petition

ers are immunized under the eleventh amendment from

19

the particular participation here ordered, which in

cludes sharing in any cost burdens incurred in imple

menting the ancillary relief. There are a number of

alternative grounds, each of which shows that the

eleventh amendment does not bar the State Petitioners

from sharing in these costs. Although this may have

an impact on the State treasury, the cost aspect of the

relief is a consequence of complying with a prospective

injunctive decree and not a payment of an accrued

monetary liability by the State. Under Edelman v. Jor

dan and Ex parte Young, therefore, the eleventh amend

ment does not apply to this form of relief. Assuming,

arguendo, that the eleventh amendment might apply,

there are two alternative grounds upon which the Court’s

prior decisions show that any immunity of Petitioner

State Board of Education has been lifted or waived.

First, Congress has specifically authorized federal courts

to entertain suits against state boards of education for

such ancillary relief in school desegregation cases. 20

U.S.C. §§ 1703(a) (b) (f), 1706, 1720 (and 881 ( k ) ).

Under Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, the State Board has thereby

been deprived of any immunity it might otherwise

possess. Second, by state statute, and perhaps its own

conduct, Petitioner State Board of Education has waived

immunity to this suit.

There are several additional, alternative grounds

which sustain the power of the lower courts here to

order the relief with cost consequences against State

Petitioners in the face of their claim of sovereign im

munity. However, these grounds raise substantial con

stitutional or jurisdictional issues never previously re

solved by this Court relating to the direct impact of

section 1 of the fourteenth amendment, 28 U.S.C. § 1331,

42 U.S.C. § 1983 and other Reconstruction statutes, and

Ex parte Young on claims of State sovereignty; and they

implicate as well the vitality of Hans v. Louisiana with

respect to federal-question determinations concerning de

2 0

jure racial discrimination. We believe the Court should

not address these questions in this case unless it cannot

agree to sustain the judgment below against claims of

sovereign immunity on the several other alternative

grounds suggested above. Even then, we respectfully

submit that this Court’s prior practice counsels that

these monumental issues not be resolved prior to remand

to the Court of Appeals for initial determination of its

views or additional briefing and reargument in this

Court on these subjects. (See Argument III, pp. 34-44,

infra.)

4. Finally, assuming arguendo the propriety of an

cillary relief and the constitutional power of the courts

below to order the State Petitioners to share in the im

plementation costs, we address the non-constitutional is

sue of whether the lower courts abused their equitable

discretion in the particular circumstances present here.

A review of the record will show that the lower courts,

particularly the Court of Appeals, were solicitous of

State policy in framing relief. Thus, for example, the

orders directing acquisition and payment for buses, a

monitoring commission, and magnet vocational schools

were conformed to State practice and are not at issue in

this Court. However, State policy was appropriately

modified to the extent of requiring State Petitioners to

bear a share of the costs of implementing a portion of

ancillary relief, given the relative resources and viola

tions of the parties defendant and the alternatives avail

able. Although State Petitioners made no claim of error

in the Court of Appeals and make none in this Court

on the amount assessed, it may still be appropriate to re

mand to the district court for hearings to allow State

defendants to make a record to insure that the actual

costs previously assessed against State defendants do not

exceed their share of the costs which have been incurred

in implementing appropriate ancillary relief over the

past year. (See Argument IV, pp. 44-49, infra.)

21

ARGUMENT

INTRODUCTION

Plaintiffs Ronald Bradley, et al., appear as Respond

ents in this Court to defend that portion of the judg

ment of the Court of Appeals here put in issue by the

State Petitioners. That judgment requires the Detroit

Board and State defendants to implement four aspects

of relief ancillary to actual pupil reassignments:

1. Remedial reading, which is necessary (a) to

begin to overcome the continuing, harmful educa

tional effects of the de jure segregation on the

plaintiff school children, and (b) to insure that

the transition to desegregated schooling is effec

tive (PA 170a; 127a; 72a).

2. Non-discriminatory guidance and counseling

which is essential for a school system undergoing

desegregation in order (a) to overcome the resid

ual effects of the de jure segregation which would

limit the educational opportunities of black

students and taint the attitudes of all students,

and (b) to encourage all students to participate

in a non-discriminatory and non-segregated fash

ion in the various magnet and vocational schools

and programs designed to alleviate the de jure

segregation (PA 170a; 128a-129a; 81a).

3. In-service training for staff, which is necessary

(a) to enable them to cope with the transition to

desegregated schools, and (b) to overcome their

own racial attitudes which have been tainted by

the de jure segregation experience (PA 170a;

128a; 73a).

4. Non-discriminatory testing, which is necessary to

insure that black students (a) are not penalized

in their present schooling for the harmful effects

of the prior de jure segregation or by the contin

uing racial bias inhering in the testing program

22

of the Detroit Public Schools, and (b) are not

resegregated from whites in separate educational

programs during the desegregation process (PA

170a; 130a; 78a-79a).

At almost every page of their Brief, however, State

Petitioners challenge the requirement that they “bear

equally [with the Detroit Board] the burdens of . . .

excess cost imposed” (PA 147a, 169a) in implementing

the decree. See Brief at 16-17, 23-39. This fixation on

the dollar consequences of injunctive relief hides rather

than reveals the real interests and issues at stake. Thus,

for example, the issue of whether relief ancillary to pupil

desegregation is appropriate has, in the first instance,

nothing to do with which parties are to be enjoined to

provide such relief. Rather, the issue is whether plain

tiffs are entitled to such ancillary relief at all. Yet at

the outset of State Petitioners’ argument on this issue

(Brief at 17), they rail against the “judicially decreed

blank check” on the state treasury.

As another example, the propriety of ordering the

State defendants to provide such ancillary relief jointly

with the Detroit Board includes two discrete questions:

First, is there constitutional power to order state-level

constitutional tort-feasors to provide injunctive relief

jointly with local defendants? Second, if so, do the

State defendants enjoy some special immunity from shar

ing in any fiscal consequences of implementing injunctive

relief? But State Petitioners focus their argument (Brief

at 23-37) almost exclusively on their asserted immunity

from supposed federal judicial raids on the State

treasury.

As a final example, assuming the power of the courts

below to enter the order challenged here, there is still

a non-constitutional issue: what equitable considerations

should guide the shaping of the injunction when State

fiscal policy or administrative practice come into con

23

flict with such complete relief? Yet State Petitioners in

their Brief bury such non-constitutional considerations in

their quest for blanket protection.

We therefore urge this Court to review the discrete

and much narrower issues actually presented rather than

State Petitioners’ rhetorical assertions. As will be shown

in Argument hereafter, this will allow the Court to re

view, and to sustain, the judgment below without im

plicating the monumental constitutional issues expressly

left unresolved by this Court since the adoption of the

Civil War Amendments and the ensuing Reconstruction

Legislation.

This narrower approach is particularly appropriate in

the circumstances of this case where the non-judicial con

duct of the district judge (see note 9 and discussion,

supra, pp. 12-13) has prevented the making of a full

record, even though State Petitioners make no claim of

procedural error. Plaintiffs therefore appear here as Re

spondents not to defend the procedures of the district

court, but to defend the judgment of the Court of Ap

peals based on the substantial evidentiary support for

the particular ancillary relief at issue. A review of the

evidence shows the propriety of ancillary relief in school

desegregation cases such as this.

In support of the judgment, plaintiffs also urge several

grounds “whether or not that ground was relied upon

or even considered by the [lower] court.” Dandridge v.

Williams, 397 U.S. 471, 475-76 n. 6 (1970). See also

United States v. American Ry. Express Co., 265 U.S.

425, 435-36 (1924) ; Langnes v. Green, 282 U.S. 531,

535-39 (1931). Application of this settled approach to

appellate review will materially assist the Court in de

ciding this case based on existing precedent without

reaching the unresolved constitutional issues on which

State defendants and the State amici seek a final, and

in our view constitutionally destructive, advisory opinion.

24

I.

RELIEF ANCILLARY TO PUPIL DESEGREGATION

IS APPROPRIATE BECAUSE ESSENTIAL TO REM

EDY THE CONTINUING HARMFUL EFFECTS OF

THE DE JURE SEGREGATION VIOLATION AND

OTHERWISE TO INSURE THE TRANSITION TO

AND MAINTENANCE OF A RACIALLY NON-

DISCRIMINATORY DETROIT PUBLIC SCHOOL

SYSTEM.

State Petitioners’ broadside at all relief ancillary to

actual pupil reassignments is unwarranted given the

record below and settled case law. As Petitioners would

have it, the remedy for a long and pervasive history of

almost total, de jure segregation is limited exclusively

to pupil reassignments— regardless of the proof concern

ing the harmful effects of such state-imposed segregation

on the educational opportunities of plaintiff children, of

the record showing the need for ancillary relief to insure

an effective transition to a non-discriminatory system of

pupil attendance and schooling, and of the other evidence

concerning aspects of racial discrimination already exist

ing in the school district or likely to appear during the

desegregation process. See Statement, supra, at notes 2,

4, and 8, and accompanying text.13

The Petitioners’ novel view would also disregard the

traditional equitable authority and duty of the federal

13 The sweep of Petitioners’ challenge to the authority of the

chancellor sitting in equity to order any necessary relief beyond

pupil reassignments may result solely from their concerns about

the State treasury rather than the propriety of such ancillary

relief. For that reason, it may be helpful for purposes of analysis

to consider the propriety of the ancillary relief apart from the State

sovereignty claims by assuming, arguendo, that the injunction

runs only against the Detroit Board. Cf. Mt. Healthy City School

District v. Doyle, 45 U.S.L.W. 4081 (U.S. Jan. 11, 1977) (school

district “not entitled to assert any Eleventh Amendment immunity

from suit in federal courts.” )

25

courts to root out the violation by rendering “ a decree

which will so far as possible eliminate the discriminatory

effects of the past as well as bar like discrimination in

the future.” United States v. Louisiana, 380 U.S. 145,

154, 156 (1965). “For it is the historic purpose of equity

to ‘secur[e] complete justice/ Brown v. Swann, 10 Pet.

[U.S.] 497, 503 (1836).” Albemarle Paper Co. V. Moody,

422 U.S. 405, 418 (1975). This principle of “'complete

justice” has always guided federal equity courts:

where federally protected rights have been invaded,

it has been the rule from the beginning that courts

will be alert to adjust their remedies so as to grant

necessary relief.

Bell v. Hood, 327 U.S. 678, 684 (1946). See also Porter

v. Warner Holding Co., 328 U.S. 395, 397-98 (1946);

Brown II, 349 U.S. 294, 300-01 (1955) ; Swann v.

Charlotte-MecJclenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1, 15

(1971) ; Ford Motor Co. v. United States, 405 U.S. 562,

575-78 (1972). And the burden is on the discriminator

not the victim to show that the injury and harm reason

ably feared to result from the discrimination did not in

fact occur, at least for purposes of insuring that the

continuing harmful effects of the violation are remedied.14

Once plaintiffs have proven a substantial violation, doubts

about what remedies will provide effective and lasting-

relief should be resolved in favor of the victims rather

than the perpetrators of the unlawful conduct.15

In the face of the uncontroverted evidence and settled

principles of equity, State Petitioners argue that, because

14 E.g., Franks v. Bowman Tramp. Co., 44 U.S.L.W. 4356, 4363

(U.S. 1976) ; cf. Keyes V. School District No. 1, 413 U.S, 189, 211

(1973).

15 E.g., Ford, Motor Co. V. United States, supra, 405 U.S. at 575;

Zenith v. Hazeltine, 395 U.S. 100, 123-24 (1969) ; United States v.

E. I. Dupont de Nemours Co., 366 U.S. 316, 334 (1961); Bigelow

V. RKO Radio Pictures, 327 U.S. 251, 265 (1945) ; Story Parch

ment Co. v. Patterson Paper Co., 282 U.S. 555, 563 (1931).

26

the only violation found in the first violation opinion was

de jure pupil segregation, Milliken and Swann limit the

remedy solely to pupil reassignments. In support of this

argument, State Petitioners (Brief at 18) parrot the

phrase that “the scope of the remedy is determined by

the nature and extent of the constitutional violation,”

Milliken, 418 U.S. at 744. Thus, under State Petition

ers’ wooden view of violation and remedy, the courts

below lacked authority to order any relief ancillary to

pupil reassignments because “there has not been any

adjudicated constitutional violation with respect to edu

cational programs in the Detroit school system.” Brief

at 18.

Yet State defendants’ own conduct and evidence belie

this unprecedented argument. First, State defendants

have acquiesced and assisted in implementing other “ an

cillary relief” ordered in this case—construction of voca

tional centers, acquisition of and payment for buses, and

operations of a monitoring commission. See Statement,

supra, at pp. 13-14; and State Petitioners’ Brief at 8 and

11-12. Second, the managing agent of State defendants,

offered as their expert, readily admitted at trial that the

four aspects of ancillary relief here at issue were either

“required” or “ deserve some special emphasis” in imple

menting a pupil desegregation plan and may otherwise

serve as a vehicle for beginning to “repair damage done

by segregation.” A 85-97. Indeed, given the State de

fendants’ experience with such ancillary relief in the

many other school desegregation cases in Michigan and

the testimony of administrators from a Title IV school

desegregation center that such ancillary relief is regu

larly included as part of the relief in school systems

undergoing desegregation, the Petitioners’ argument is,

literally, incredible. They have no basis for implying

(Brief at 20-21) that in the twenty-two years since

Brown, such ancillary relief has had no place in the

school desegregation process. Thus, State defendants’ ad

27

missions and experience, as well as the substantial evi

dence, support the holding of the courts below that such

ancillary relief is necessary to remedy the continuing

consequences of the violations found, and is essential in

the transition to a racially non-discriminatory system of

schooling.

This conclusion is also supported by case law, express

congressional authorization, and HEW regulations. First,

courts have regularly included such ancillary relief in

desegregation decrees in order (1) to eradicate the re

sidual resource and educational opportunity discrimina

tions, as well as the continuing harm resulting from the

primary pupil segregation violation, and (2) to insure

the effective implementation of pupil desegregation and

transition to effective racial non-discrimination in public

schooling.16 Such essential ancillary relief is included in

school desegregation decrees precisely because it is “de

signed . . . to restore the victims of discriminatory con

duct to the position they would have occupied in the

absence of such conduct.” Milliken, 418 U.S. at 746.

Second, Congress and HEW have on several occasions

analyzed the need for precisely such ancillary relief to

insure effective desegregation. They have not only found

it essential, but have provided funding and technical as

sistance to state and local educational agencies for that

purpose. See, e.g., Emergency School Aid Act, 20 U.S.C.

16E.g., Morgan v. Kerrigan, 401 F. Supp. 216, 231, 234-35 (D.

Mass. 1975), aff’d, 530 F.2d 401 (1st Cir. 1976); United States v.

Jefferson County Bd. of Educ., 372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966), 380

F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967) ; Plaquemines Parish School Bd. v. United

States, 415 F.2d 817 (5th Cir. 1969); United States v. Texas, 330

F. Supp. 235 (E.D. Tex. 1971); Lee v. Macon County Board of

Educ., 267 F. Supp. 458 (M.D. Ala. 1967), 317 F. Supp. 103 (M.D.

Ala. 1970) ; United States v. Missouri, 523 F.2d 885, 887-88 (8th

Cir. 1975). Cf. Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969)

and Swann, 402 U.S. at 18-20; Wright V. Council of City of Emporia,

407 U.S. 451, 465 (1972) ; Gilmore V. City of Montgomery, 417

U.S. 556, 571 (1974); Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965).

28

§§1601 and 1606(a); 45 C.F.R. §§180.12, .31, .41; 42

U.S.C. §§ 2000c-2 and c-4; 45 C.F.R. § 185.12(a) (re

printed in Appendix B attached hereto).17 Congress and

HEW, like the courts, have thus expressly recognized

that the elimination of de jure pupil segregation requires

more than just pupil reassignments to be effective in

beginning to overcome the harm inflicted by the violation

as well as to insure the transition to racially non-dis-

criminatory schooling.

The point of this judicial, congressional, and adminis

trative authority is not to give federal judges a roving-

commission to order general improvements in the educa

tion offered students in school districts found guilty of

de jure segregation. Due at least in part to the critical

examination given the Detroit Board’s initial proposals

by the plaintiffs (and by the State defendants), plaintiffs

(and this Court) can be certain that the ancillary relief

contemplated by the parties and the district court prior

to the district judge’s remarkable exclusion of plaintiffs

from further proceedings (see note 9, supra) was care

fully limited to the equitable tasks at hand— to remedy

the harmful effects and residual discrimination inhering

in the de jure segregation violation, to overcome the

other racial discriminations in schooling of record, and

to assist the transition to a racially non-discriminatory

system of schooling. And the Court of Appeals was

17 See also 116 Cong. Rec. 18109-10 (1970); S. Rep. 92-61 at

8, 13 (1971); H. Rep. 92-576 at 5, 13 (1971); Toward, Equal Edu

cational Opportunity, Report of the Select S. Comm., on Equal Edu

cational Opportunity, 92 Cong., 2d Sess, at 129-40, 233-37 (1972)

(Comm. Print). Cf. Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974,

particularly 20 U.S.C. §■§ 1703(a) (b ) ( f ) and 1713(a). It is also

relevant that two of the most experienced professionals from one

of the authorized Title IV School Desegregation Centers carefully

examined the ancillary relief here at issue to insure that its pur

poses, programs, and costs were limited to essential adjuncts of

the pupil desegregation relief rather than providing only generally

improved educational opportunities. See note 8, supra.

29

thereafter careful to insure that the ancillary relief as

finally decreed does not present “ a situation where the

District Court appears to have ‘acted solely according to

its own notions of good educational policy unrelated to

the demands of the Constitution.’ See, Keyes v. School

District, 521 F.2d 465, 483 (10th Cir. 1975).” PA 171a.

Aside from presenting a stone wall to the ancillary

relief here, State Petitioners therefore offer no reason,

authority, nor record evidence to suggest any abuse of

equitable discretion or excess of judicial authority in the

relief ordered by the lower courts.18 To put the point

bluntly, State Petitioners’ challenge to the authority of

the courts below to order any ancillary relief is naught

but a frolic or detour on the way to consideration of

their primary claim that they alone among the culpable

defendants should be free from judicial compulsion to

implement such manifestly appropriate relief.

18 Thus, State defendants do not argue, for example, that special