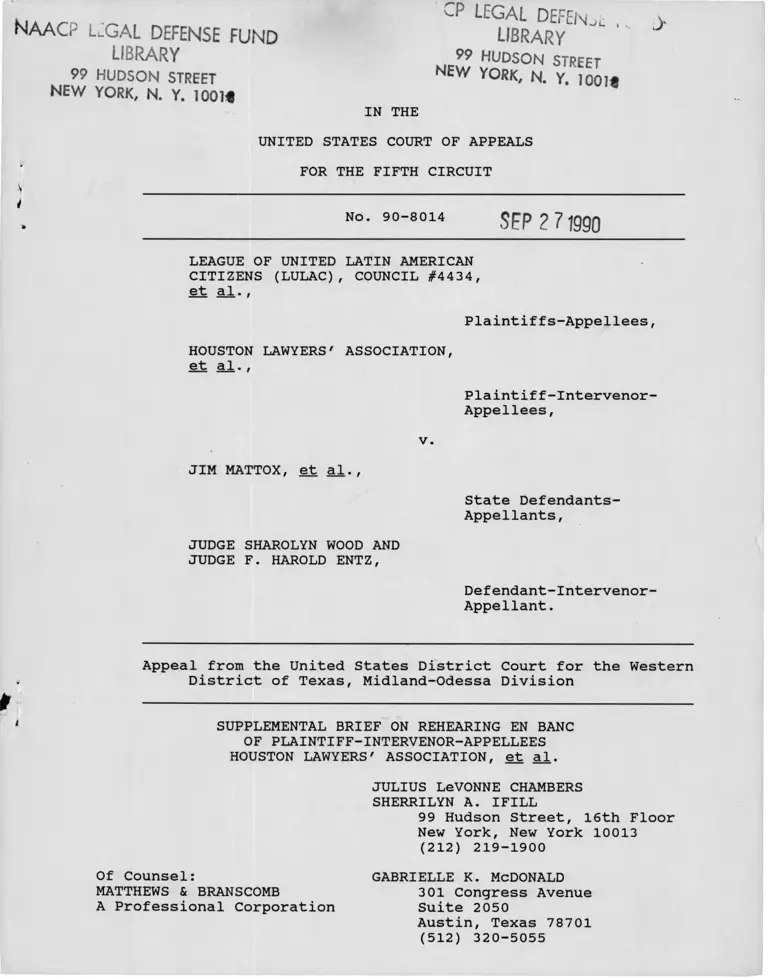

League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), Council #4434 v. Mattox Supplemental Brief on Rehearing En Banc of Plaintiff-Intervenor-Appellees

Public Court Documents

September 27, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), Council #4434 v. Mattox Supplemental Brief on Rehearing En Banc of Plaintiff-Intervenor-Appellees, 1990. c5346ec8-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5050b3bd-1a26-4f5f-8e75-741010302339/league-of-united-latin-american-citizens-lulac-council-4434-v-mattox-supplemental-brief-on-rehearing-en-banc-of-plaintiff-intervenor-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Naacp llgal defense fund

library

99 HUDSON STREET

NEW YORK, N. Y. 10014

library

n f w ™ D$ON STREETNEW YORK, N. Y. 1001«

>

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 90-8014 SEP 2 2 1990

LEAGUE OF UNITED LATIN AMERICAN

CITIZENS (LULAC), COUNCIL #4434,

et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

HOUSTON LAWYERS' ASSOCIATION,

et al.,

Plaintiff-Intervenor-

Appellees,

V.

JIM MATTOX, et al..

State Defendants-

Appellants,

JUDGE SHAROLYN WOOD AND

JUDGE F. HAROLD ENTZ,

Defendant-Intervenor-

Appellant.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the Western

District of Texas, Midland-Odessa Division

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF ON REHEARING EN BANC

OF PLAINTIFF-INTERVENOR-APPELLEES

HOUSTON LAWYERS' ASSOCIATION, et al.

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

SHERRILYN A. IFILL

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

GABRIELLE K. MCDONALD

301 Congress Avenue

Suite 2050

Austin, Texas 78701

(512) 320-5055

Of Counsel:

MATTHEWS & BRANSCOMB

A Professional Corporation

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES........................................ ii

SUPPLEMENTAL STATEMENT OF FACTS ............................ 1

* INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT .................. 2

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT.................................... 3

ARGUMENT .................................................. 6

I. Section 2 Covers the Election of Judges .......... 6

II. The Application of Section 2 is Not Dependent on the

Function of the Elected Officer .................. 11

A. The Trial Judges in the Challenged Counties Are

Not Single Person Officers .................. 13

2. Butts Does Not Support Limiting Section 2's

Scope to Collegial Decision-Makers . . . 17

3. Butts Erroneously Interprets Amended §2 . 18

III. Remedial Concerns Are Not Properly Addressed at the

Liability Stage of a Voting Rights Case ........ 21

A. The Proper Scope of the Liability Inquiry . . . 22

B. The LULAC Panel's Analysis of Sub-Districts

as a Remedy is Critically F l a w e d ............ 23

1. The LULAC Panel's Analysis of the

Plaintiffs' District Plan Fails on Its

Own T e r m s ................................ 2 5

C. The LULAC Panel's Focus on a Sub-Districting

i Remedy is Particularly Inappropriate in

This C a s e .................................... 28

I 1. Limited Voting.......................... 3 0

2. Cumulative Voting .................... 32

IV. The District Court's Finding of a §2 Violation is

Not Clearly Erroneous .................... 32

CONCLUSION................................................ 3 6 l

l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Bell v. Southwell, 376 F.2d 659

(5th Cir. 1967) .................................. 20, 21

Blaikie v. Power, 13 N.Y.2d 134,

243 N. Y. S . 2d 185 (1963)................................ 31

Bolden v. City of Mobile, 571 F.2d 238 rev'd on other grounds,

Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980) .................. 15

Buchanan v. City of Jackson, 683 F.Supp.

1515 (W.D. Tenn., 1988) .............................. 15

Butts v. City of New York, 614 F.Supp. 1527 (S.D.N.Y. 1985) . 13

Butts v. City of New York, 779 F.2d

141 (2d. Cir. 1985).......................... 11, 19, 21

Campos v. City of Baytown, 840 F.2d 1240,1243

(5th Cir. 1988) cert denied 109 S. Ct.

3213 (1989).................................... 2, 6, 35

Carrollton Branch of NAACP v. Stallings, 829 F.2d

1547 (11th Cir. 1987)cert, denied sub nom. Duncan v.

Carrollton. 485 U.S. 936 (1988) ...................... 10

Chisom v. Edwards, 839 F.2d 1056,

cert denied, 109 S.Ct. 390 (1988) ................ passim

Cintron-Garcia v. Romero-Barcelo, 671 F.2d

1,6 ( 1st Cir. 1982) ................................ 31

Citizens for a Better Gretna v. City of Gretna,

636 F.Supp. 1113, (E.D. La. 1986), aff'd,

834 F. 2d 496 (5th Cir. 1987) .......................... 35

City of Port Arthur v. United States,

459 U.S. 159 (1975).................................... 18

City of Richmond v. United States, 422 U.S. 358 (1975) . . . . 18

Cox v. Katz, 22 N.Y.S.2d 545 (1968) ........................ 28

Dillard v. Chilton County Bd. of Educ., 699 F.Supp.

870 (M.D. Ala. 1988) . ............................... 29

iii

Dillard v. Crenshaw County, 831 F.2d 246

(11th Cir. 1987)............................ 12, 22, 29

Dillard v. Town of Cuba, 708 F.Supp. 1244 (M.D. Ala. 1988) . . 29

Gingles v. Edmisten, 590, F.Supp. 345 (E.D. N.C. 1984) . 35, 36

Gray v. Sanders, 372 U.S. 368 (1963)........................ 21

Haith v. Martin, 477 US 901 (1986).......................... 13

Hechinger v. Martin, 411 F.Supp.

650 (D.D.C 1976) aff'd per curiam

429 U.S. 1030 (1977) .................................. 31

Holhouser v. Scott, 335 F.Supp. 928 (M.D.N.C. 1971) ........ 28

Kaelin v. Warden, 334 F.Supp. 602 .......................... 31

Kirksey v. Allain, 635 F.Supp. 347 (S.D. Miss., 1986) . . . . 13

Kirksey v. City of Jackson, Miss., 663 F.2d.,

659 (5th Cir. 1981) rehearing and

rehearing en banc denied 669 F.2d.

316 (5th Cir. 1982).....................................37

LoFrisco v. Schaffer, 341 F.Supp. 743 (D. Conn., 1972) . . . . 31

LULAC v. Mattox, No. 90-8014, (May 11, 1990) . ........... passim

LULAC v. Midland ISD, 812 F.2d 1494,

(5th Cir. 1987), vacated on other grounds,

829 F. 2d 546 (5th Cir. 1987) 35

Mallory v. Eyrich, 839 F.2d 275 (6th Cir. 1988) 8

Martin v. Allain, 658 F.Supp. 1183 (S.D. Miss 1987) 11

Martin v. Allain, 700 F.Supp. 327 (S.D.Miss. 1988) . . . 22, 28

Martin V . Haith, 477 U.S. 901 (1986), aff'g. 618 F.Supp.

410 (E.D.N.C.1985) .................................... 7

Nipper v. U-Haul, 516 S.W.2d 467 (Tex. Civ. App. 1974) . . 27, 28

Orloski v. Davis, 564 F.Supp. 526 (M.D. Pa. 1983) 31

Overton v. City of Austin, 871 F.2d 529,

538 (5th Cir. 1989)................................ 6, 35

Reed v. State of Texas, 500 S.W.2d 137

(Tex. Crim. App. 1973) .......................... 27, 28

iv

SCLC v. Siegelman, 714 F.Supp. 511, (M.D. Ala. 1989) . . . 14, 15

Smith v. Allwright 321 U.S. 649 (1944)...................... 2

Solomon v. Liberty County, No. 87-3406

(11th Cir. April 5, 1990).............................. 36

Terry v. Adams 345 U.S. 461 (1952).......................... 2

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986)................ passim

Upham v. Seamon, 456 U.S. 37 (1982) ........................ 2

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973).................. 2, 38

Whitcomb v. Chavis 403 U.S. 124 (1971).................... 38

Voter Information Project v. City of

Baton Rouge, 612 F.2d 208 (5th Cir., 1980) ........ 38, 39

Zimmer v. McKeithan 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973) .......... 38

STATUTES

Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §1973 ....................... passim

Tex. Gov't Code §74.047 (Vernon 1988) .................... .16

Tex. Gov't Code §74.091 (Vernon 1988 & Supp.1990) .......... 16

LEGISLATIVE

House Report No. 97-227, 9th Cong., 1st Sess.,

at p. 19 (1982) .............................. 2, 20, 37

S. Rep. No. 97-417, 97th Cong.,

2nd Sess., at p. 30 (1987)........................passim

Voting Rights: Hearings Before Subcommittee No. 5

of the House Judiciary Comm., Testimony of

Attorney General Katzenbach, 89th Cong.,

1st Sess. (1965) ...................................... 7

v

OTHER

Issacharoff, The Texas Judiciary and

the Voting Rights Act: Background

and Options, at 18, Texas Policy Research

Forum (December 4, 1989) .............. 30, 31

Karlan, Maps and Misreadings: The Role

of Georgraphic Compactness in Racial

Vote Dilution Litigation, 24 Harv.

C.R.-C.L.L.Rev. 173 (1989) . . . . 30, 32

Office of Court Administration, Texas Judicial

Council, Texas Minority Judges, Feb. 10, 1989 2

R. Engstrom, D. Taebel & R. Cole, Cumulative

Voting as Remedy for Minority Vote Dilution:

The Case of Alamogordo, New Mexico, The Journal

of Law & Politics, Vol. V., No. 3 (Spring 1989) . . . 29, 32

State Court Organization 1987, National

Center for State Courts, 1988 .......................... 2

vi

SUPPLEMENTAL STATEMENT OF FACTS

Plaintiff-intervenor appellees Houston Lawyers' Association,

et al. , directs this court to the Statement of Facts which appears

in their original Brief on Appeal, as well as the Statement of

Facts in the original Brief on Appeal for the United States as

Amicus Curiae, describing in detail the structure of the court

system in Texas.

SUPPLEMENTAL STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Plaintiff-intervenor appellee Houston Lawyers' Association

incorporates by reference the Statement of the Case which appears

in its original Brief on Appeal, and supplements that statement as

follows.

This case was heard on appeal before a panel of the Fifth

Circuit on April 30, 1990. On May 11, 1990, the panel issued an

opinion reversing the decision of the district court. That panel

opinion did not address the district court's finding that African-

American voters in Harris County, Texas do not enjoy an egual

opportunity to elect their preferred candidates to the judiciary.

Rather, the panel opinion, relying principally on Second Circuit

case law, held that the election of trial judges cannot be

challenged under §2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C.

§1973, because trial judges are independent decisionmakers.

On May 16, 1990, this court, sua sponte, vacated the panel

opinion and ordered that the case be heard in banc. Oral argument

was set by the court for June 19, 1990. The parties were invited

to file simultaneous supplemental briefs to the court on or before

June 5, 1990.

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

INTRODUCTION

Texas has a long history of enacting and maintaining electoral

structures and practices which inhibit the political and electoral

participation of African Americans and other minorities. See,

Smith v. Allwriaht. 321 U.S. 649 (1944); Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S.

461 (1953); White v. Regester. 412 U.S. 755 (1973); Upham_Vj_

Seamon. 456 U.S. 37 (1982); Campos v. City of Baytown, 840 F.2d

1240 (5th Cir. 1988). See also House Report No. 97-227, 9th Cong.,

1st Sess., at p. 19 (1982) [hereinafter "House Report"]. The case

before this court challenges the electoral structure of one of the

last nearly all-white elected bodies in the Texas government — the

judiciary.

Of the 9,977 appellate and general jurisdiction trial court

judges in the United States, 6,466 are elected to office. State

Court Organization 1987. at 127-142, 271-302, National Center for

State Courts, 1988. These judges are elected in nearly forty

states across the county. .Id. at 7-10. In Texas alone, there are

375 elected district court trial judges. Only 7 of these judges

are African American. Office of Court Administration, Texas

Judicial Council, Texas Minority Judges, Feb. 10, 1989. In Harris

2

County, the largest and most populous judicial district in the

State, only 3 African Americans have ever served as district

judges. African Americans, however, make up nearly 20% of the

population of Harris County, and 18% of the voting age population.

Under the current county-wide method of electing district

judges, African American voters are submerged in a district of

nearly 2.5 million people and over 1,200,000 registered voters.

Because white voters in Harris County district judge elections do

not vote for African American judicial candidates who face white

opponents, African American voters in the county cannot elect their

preferred representatives to the bench.

If based on these facts and those in the record, this case

involved a challenge to city council elections, the district

court's judgment would have been upheld, and this case would be

before the district court for a determination of the appropriate

remedy. But alone among all appellate courts, a panel of this

court has created an exemption for the election of trial judges

from the strictures of §2 of the Voting Rights Act.

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

As "the major statutory prohibition of all voting rights

discrimination" in the United States, Senate Report No. 97-417,

97th Cong., 2nd Sess., at p. 30 (1982) [hereinafter "S. Rep."] §2

of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. §1973, prohibits the

use of discriminatory election structures and practices in every

3

election in which electors are permitted to cast votes. Section

2 of the Voting Rights Act is violated whenever electoral

structures or procedures "result in a denial or abridgement of the

right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of

race or color." 42 U.S.C. §1973.

Congress intended §2 of the Voting Rights Act to be

comprehensive in scope and application. The only limiting language

in the Act cautions that lack of proportional representation does

not constitute a §2 violation. Congress did not exempt, neither

explicitly nor implicitly, particular elected offices from the

purview of the Act. In particular, the Act covers the election of

judges - both appellate and trial. Nothing in the legislative

history indicates that Congress intended to exclude nearly 10,000

elected offices from the reach of African American voters. In

fact, the legislative history of the Act makes reference to both

the election of judges and the creation of judicial districts.

Almost all of these references are to trial judge elections and

districts. See discussion in original Brief on Appeal for the

United States as Amicus Curiae at 16-17, LULAC v. Mattox, No. 90-

8014 (May 11, 1990).

The Act also applies to the election of single-person

officers, or offices for which only one person is elected in the

geographical district. There is no legislative history to the

contrary.

The Supreme Court has instructed that in order to prevail in

a §2 claim, plaintiffs must show: that the minority population in

4

the challenged district is sufficiently large and geographically

compact to constitute a majority in a fairly drawn single-member

district; that the minority group in the district is politically

cohesive; and that whites in the district vote sufficiently as a

bloc so as to usually defeat the candidate of choice of minority

voters, absent special circumstances. Thornburg v. Gingles, 478

U.S. 30, 50-51 (1986). Once plaintiffs have made this threshold

showing, they may further support their claim by demonstrating

through objective factors, how the challenged electoral structure

"interacts with social and historical conditions to cause an

inequality in the opportunities enjoyed by black and white voters

to elect their preferred representatives." Id. at 47. To guide

courts in their analysis, Congress has provided a list of objective

factors which, if proven, tend to support the existence of

impermissible vote dilution. Most important among these factors

is the extent to which minorities have been elected to office in

the challenged jurisdiction and the existence of racially polarized

voting. Gingles, 478 U.S. at 45 n.15. While this list is not

exhaustive, Congress specifically excluded highly subjective

factors from consideration. House Report at 30.

In proving the first prong of Gingles, plaintiffs are not

required to provide the court with actual remedial plans to cure

the alleged violation. Therefore, remedial concerns based on the

plaintiffs' illustrative plans are not a basis for rejecting a

liability finding. The trier of fact must limit its liability

determination to the "impact of the contested structure or practice

5

on minority electoral opportunities." Gingles. 478 U.S. at 44.

Plaintiffs may prove the existence of the second and third

prong of the Gingles test through standard statistical analyses for

determining racial vote dilution, supported by lay testimony. See

Gingles. 478 U.S. at 53 n.20. Accord Overton v. City of Austin,

871 F.2d 529 (5th Cir. 1989); Campos v. City of Baytown, 840 F.2d

1240 (5th Cir. 1988), cert. denied. 109 S.Ct. 3213 (1989).

Congress deliberately excluded subjective inquiries into the

motives of white voters who do not vote for African American

candidates from the proper scope of a vote dilution analysis.

In the case at hand, the district court, based on the record

and the proper application of the relevant law, correctly found

that the county-wide election of district judges in Harris County

violates §2 of the Voting Rights Act.

ARGUMENT

I. Section 2 Covers the Election of Judges

There is no reason for this court to reconsider the issues

briefed, argued and decided in Chisom v. Edwards, 839 F.2d 1056,

(5th Cir. 1988), cert, denied. 109 S.Ct. 390 (1988). Chisom1s

conclusions were based on an exhaustive analysis of "the language

of the [Voting Rights] Act itself; the policies behind the

enactment of section 2; pertinent legislative history; previous

6

judicial interpretations of section 5, a companion section to

section 2 in the Act; and the position of the United States

Attorney General on this issue." 839 F.2d at 1058. Both the

Chisom and LULAC panels' comprehensive review of the relevant

legislative history of amended §2 found no indication that Congress

contemplated the creation of an exemption for elected judges from

the purview of §2. This court's decision in Chisom therefore

applied the general and undisputed principle that Congress intended

the Voting Rights Act to cover "[e]very election in which

registered electors are permitted to vote"1 to the particular

elections at issue in that case (Louisiana Supreme Court Judges).

The defendants in this case raise no new arguments or subseguent

history which could alter this court's holding in Chisom that

judicial elections are covered by §2.

Every appellate court to address the issue has concluded that

judicial elections are covered by the Voting Rights Act. See

Martin v. Haith, 477 U.S. 901 (1986), aff'g, 618 F.Supp. 410

(E.D.N.C 1985)(three judge court) (holding that §5 covers the

Voting Rights; Hearings Before Subcommittee No. 5 of the

House Judiciary Comm., Testimony of Attorney General Katzenbach,

89th Cong., 1st Sess. (1965) [hereinafter "House Hearings"].

Section 14 (c)(1) of the Act defines "voting" for purposes of the

Act as:

all action necessary to make a vote effective in any

primary, special or general election, including, but not

limited to, registration, listing pursuant to this sub

chapter or other action required by law prerequisite to

voting, casting a ballot, and having such ballot counted

properly and included in the appropriate totals of votes

cast with respect to candidates for public or party

office and propositions for which votes are received in

an election.

7

election of superior court trial judges in North Carolina) ;

Mallorv v. Evrich. 839 F.2d 275 (6th Cir. 1988) (holding that §2

covers the election of Cincinnati municipal trial judges); LULAC

v. Mattox. No. 90-8014, (May 11, 1990) [hereinafter "LULAC Panel

Op."] (holding, in relevant part, that judicial elections are

covered by §2), vacated and reh'g en banc granted (May 16, 1990);

Chisom v. Edvards. 839 F.2d 1056 (5th Cir. 1988), cert, denied, 109

S.Ct. 390 (1988) (holding that §2 covers judicial elections). Cf.

Voter Information Project v. City of Baton Rouge, 612 F.2d 208 (5th

Cir. 1980) (holding that intentionally discriminatory election

scheme for Baton Rouge trial judges violates Fifteenth Amendment).

* * * * * *

The defendants' argument that the election of trial judges,

in particular, must be exempt from the strictures of the Voting

Rights Act has never been endorsed by any court. Even the panel

majority in LULAC concedes that there is no rationale for drawing

a distinction between trial judges and other judges for the

purposes of §2 coverage. LULAC. Panel Op. at 24.

In LULAC. the plaintiffs prevailed in the district court on

proof of discriminatory results.2 In Voter Information Pronect,

the plaintiffs proceeded under the Fifteenth Amendment intent

discriminatory intent in violation of §2 may be proven

"through direct or indirect circumstantial evidence, including the

normal inferences to be drawn from the foreseeability of

defendant's actions." S.Rep. at 27 n.108.

8

standard. In essence, therefore, the only difference between the

cause of action brought in Voter Information Project and the cause

of action in LULAC is the intent behind the adoption and

maintenance of at-large judicial systems.

The defendants and the LULAC panel view the absence of intent

as fatal to the LULAC plaintiffs' claim under §2. Apparently, if

the plaintiffs in LULAC had presented "smoking gun" evidence of

the existence of an intentionally discriminatory motive in the

enactment of the county-wide district judge election system in

Texas, defendants would concede that this method of election would

violate both §2 and the Fifteenth Amendment. See LULAC, Panel Op.

at 34 n.10. Absent such a showing of intent, the defendants and

the LULAC majority argue that §2 cannot be applied to the election

of trial judges.

But Congress has specifically instructed that the presence or

absence of discriminatory intent is irrelevant to the question

whether §2 has been violated. The very essence of amended §2

negates the relevance of intent. See House Report at p. 29-30.

Therefore, given that this Court has found that the election of

trial judges may not intentionally discriminate against African

American voters, a trial judge electoral system that results in

African Americans having an unequal opportunity to participate and

elect candidates of their choice must be an equally invalid under

§2. No other of the Act interpretation is consistent with

Congress' intent in amending §2 and this court's prior

interpretation of vote dilution law. The LULAC panel mistakenly

9

relies on Carrollton Branch of NAACP v. Stallings, 829 F.2d 1547

(11th Cir. 1987), cert, denied sub nom. Duncan v. Carrollton, 485

U.S. 936 (1988) to support its distinction between the application

of the Voting Rights Act to intentionally discriminatory electoral

structures and its in—applicability to electoral schemes which

result in an unequal opportunity for African Americans to elect

their candidates of choice. The LULAC panel interprets Stallinqs

to hold that a single-person office may be challenged on grounds

of racial discrimination only if such a challenge is based on a

claim of impermissible intent. LULAC. Panel Op. at 34 n. 10. This

reading of Stallings is clearly contradicted at the very outset of

the Stallings opinion: "[w]e consider the single-member county

commission here to be in all essential respects comparable with the

multi-member district discussed by the court in Gingles." 829 F_.2d

at 1549 (referring to Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986)).

The court in Stallings then engages in an exhaustive review and

analysis of the results test under Gingles for determining whether

the one person commissioner form of government in Carroll County

violates §2. 829 F.2d at 1553-1562. Finally, the Eleventh Circuit

remanded the case to the district court, not only because it found

a constitutional violation, but also "for consideration in light

of Gingles." and its interpretation of the test set out in

Gingles. 829 F.2d at 1563. See also LULAC. Dissent at 5, n.4.

Both the trial court's and the Eleventh Circuit's reliance on

Gingles makes clear that Stallings did not require proof of intent.

10

II. The Application of Section 2 Does Not Depend on the

Function of the Elected Officer

At its core, this Court's decision in Chisom is a rejection

of the view that the function of the elected officer determines

the applicability of section 2. The court in Chisom specifically

disavowed the approach advocated by the defendants, which focussed

on the function of the elected officer as determinative of the

applicability of section 2. The Chisom panel, finding the

defendants' view "untenable" 839 F.2d at 1063, explained that:

Judges, while not 'representatives' in the

traditional sense, do indeed reflect the

sentiment of the majority of the people

as to the individuals they choose to entrust

with the responsibility of administering

the law.

Id. The Chisom panel endorsed the view of the court in Martin v

Allain. 658 F.Supp 1183 (S.D. Miss 1987), that §2's use of the word

representatives "denotes anyone selected or chosen_by_popular

election from among a field of candidates to fill an office,

including judges." 839 F.2d at 1063,(emphasis added) (quoting

Martin v. Allain. 658 F.Supp at 1200). Chisom never referred to

the function of the Louisiana Supreme Court judges as "collegial"

decision-makers as a rationale for the inclusion of those elections

under the purview of §2.

No appellate court since Butts v. City of New York, 779 F.2d

141 (2d. Cir. 1985), cert, denied. 478 U.S. 1021 (1986), has

conditioned application of the Voting Rights Act to an elected

11

office on the function of the elected officers at issue. The

Eleventh Circuit, in particular, has recognized that the function

of an elected official is irrelevant to a court's inquiry under §2.

The Eleventh Circuit's decision in Dillard v. Crenshaw

County. 831 F.2d 246 (11th Cir. 1987), clearly contradicts the

analysis endorsed by the LULAC panel. Dillard rejects the

defendants' attempt to carve out a §2 exemption for elected

officers performing administrative functions. The court found that

§ 2 applies to all elected offices, whether the function performed

by the officer is either legislative or administrative. As the

Dillard court explains,

Nowhere in the language of Section 2 nor in

the legislative history does Congress

condition the applicability of Section 2

on the function performed by an elected

official. The language is only and

uncompromisingly premised on the fact

of the nomination or election. Thus, on

the face of Section 2, it is irrelevant

that the chairperson performs only

administrative or executive duties. It

is only relevant that Calhoun County has

expressed an interest in retaining the

post as an electoral position. Once a

post is open to the electorate, and if it

is shown that the context of that election

creates a discriminatory but corrigible

election practice, it must be

open in a way that allows racial groups to

participate equally, (footnote omitted)

831 F 2d at 250-251. Following the reasoning of Dillard, the

Eleventh Circuit would not, as the LULAC panel does, foreclose a

finding of §2 liability based on the functions performed by the

12

elected official.3

Nevertheless, the LULAC panel adopts the radical analysis of

the Second Circuit in Butts. and holds that the function of trial

judges warrants exemption from §2. The LULAC panel reconstructs

the analysis and holding of Chisom to apply only to the election

of judges who serve, like legislators, on collegial decision

making bodies. Butts is completely inapposite to the case at hand

and, in any event, seriously misinterprets §2.

A. The Trial Judges in the Challenged Counties Are Not

Single Person Officers

The holding in Butts cannot be applied to the facts in this

case. In Butts, the district court held that the 40% vote

requirement in party primaries for the offices of Mayor, City

Council President and Comptroller violated §2 of the Voting Rights

Act, in that it denied African American and Hispanic voters in New

York City an equal opportunity to elect candidates to those three

city-wide offices. Butts v. City of New York, 614 F. Supp. 1527

(S.D.N.Y. 1985). The Second Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the

district court's holding on the grounds that "there can be no equal

opportunity for representation within an office filled by one

person." 779 F.2d at 148. The court in Butts found that "there

3This conclusion is consistent with the way courts have

construed §5 cases. See Haith v. Martin. 477 U.S. 901 (1986) ;

Kirksev v. Allain. 635 F. Supp. 347 (S.D. Miss. 1986) (three-judge

court). In accordance with Congressional intent, "[sjections 2

and 5 operate in tandem." LULAC. Panel Op. at 23. The function

of the elected officer has no part in the application of any

section of the Voting Rights Act.

13

is no such thing as a 'share' of a single-member office". Id.

The offices at issue in Butts were offices for which only one

candidate was elected to serve the entire city. "[T]here would

not, for example, be two comptrollers serving that geographic

area." LULAC, Dissent at 7. At issue in the case at hand are at-

large elections for district judges in counties served by more than

one district judge. In Harris County, for example, 59 district

judges are elected in staggered elections for six—year terms. Each

judge runs for a numbered post — but each judge is elected by all

voters in the county and each judge has statewide jurisdiction.

"Unlike the election for mayor or comptroller in Butts, the instant

case is concerned with the election, within discrete geographic

areas, of a number of officials with similar, and in most cases

identical, functions." LULAC, Dissent at 9; see also SCLC_v_;_

Sieaelman. 714 F.Supp 511,518 n.19 (M.D. Ala. 1989) ("what is

important is how many positions there are in the voting

jurisdiction") .

If Harris County elected only one district judge to serve

the entire county, then plaintiffs might find it difficult to prove

that there should be 59 judges, and the Butts analysis would

arguably be relevant, though not controlling. But that is not this

case. Counties in Texas that elect only one district judge are not

at issue in this case. The LULAC majority correctly points out

that "it is no accident" that those counties' electoral systems

were not challenged by the plaintiffs. Panel Op. at 38. The State

of Texas has decided to have 59 district judges serve Harris

14

County. The at-large system of electing district judges in the

challenged counties in Texas therefore, is simply not comparable

to the elected offices at issue in Butts. See SCLC v. Siegelman,

supra.

The specialization of family, civil and criminal court judges

does not support the argument made by the LULAC panel that district

judges are single-person officers exempt from §2. Section 2 has

been applied to the election of commissioners who, like the judges

in this case, are elected at-large by all the voters in the

jurisdiction, to serve special functions. See e.g ., Bolden v. City

of Mobile. 571 F.2d. 238 (5th Cir. 1978) (upholding application of

§2 to three-member city commission, each assigned particular city

wide functions) rev'd on other grounds, 446 U.S. 55 (1980) on

remand. 642 F.Supp. 1050 (S.D. Ala. 1982) (striking down Commission

system based on discriminatory intent); Buchanan v. City__of

Jackson. Tenn.■ 683 F.Supp. 1515 (W.D. Tenn.1988) (striking down

as violative of §2, at—large method of electing three-member

commission, where the city charter assigned each commissioner

specific duties).4

A review of the function of district judges in Texas also

suggests that district judges do not, in fact, exercise the full

4In Mobile. the administration of the Department of Finance

and Administration, the Department of Public Safety, and the

Department of Public Works and Services, were assigned to each of

the three commissioners respectively. In Buchanan, "The Mayor

served as Commissioner of Public Affairs, Public Safety, Revenue

and Finance, and the other commissioners served as the Commissioner

of Streets, Sewers, Public Improvements and Public Utilities, and

the Commissioner of Health, Education, Parks, and Public Property."

683 F.Supp. at 1522

15

authority of their offices independently. Trial judges engage in

a number of collegial decision-making functions. Panel Op. at 27 —

30. Some of these collegial administrative functions are minor,

while others affect the structure and function of the entire trial

judge electoral system in the county.5

Even after trial judges are assigned cases they do not

function as exclusive and independent decision-makers.6 "Cases

can be freely transferred between judges...and any judge can work

on any part of a case including preliminary matters." Panel Op.

at 28. In addition, case assignments, jury empaneling and case

record-keeping are handled on a county—wide collective basis. Tr.

at 3-267; Tr. at 4-255-256. These collegial functions within the

county-wide electoral structure demonstrate that district judges

do not, in fact, exercise the full authority of their offices

5For instance, the Governor appoints a presiding

administrative judge to correspond to the nine administrative

judicial regions in Texas, from among the sitting district judges.

Panel Op. at 28. This judge "is the key administrative officer in

the Texas judicial system." Id. The presiding administrative

judge is responsible for assigning judges within his region. Id.

at 29. This judge also calls two meetings at which all of the

judges in his/her region meet "to promulgate administrative rules,

rules governing the order of trials and county-wide recordkeeping,

and other rules deemed necessary." Id. at 29, quoting Tex. Gov't

Code §74.048 (b)-(c) (Vernon 1988). The presiding judge is also

endowed with the more general power to initiate action which will

"improve the management of the court system and the administration

of justice" in his region. Tex. Gov't Code §74.047 (Vernon 1988).

In addition, a local administrative judge, whose duties are

similar to those of the presiding judge on a local level, is

elected by a majority vote of all the judges in the county. Tex.

Gov't Code §74.091 (Vernon 1988 & Supp.1990). District judges are

also responsible for the appointment of a county auditor. LULAC,

Dissent at 8.

6A11 cases are filed in a central "intake" for the county.

Cases are then assigned randomly to a trial judge. Tr. at 4-255.

16

exclusively.

The LULAC panel's suggestion that "other rules attending the

election of single officials, such as majority vote requirements,

anti-single-shot voting provisions, or numbered posts," can be

challenged under §2 reveals the weaknesses in its reasoning. Panel

Op. at 39. First, as the dissent points out, "voting structures

such as numbered posts do not logically apply to a single office

position." LULAC. Dissent at 8-9 n.9. Indeed, a majority vote and

numbered post requirement are two of the three factors specifically

identified in the Senate Report as electoral features which in an

at—large system tend to "enhance the opportunity for discrimination

against the minority group." S.Rep. at 29. The LULAC panel

implicitly recognizes therefore, that district judges in Texas are

elected in an at-large system. Secondly, if the LULAC panel

believes that the majority vote requirement can be challenged under

§2, then it cannot rely on Butts, because Butts held precisely the

opposite.

2. Butts Does Not Support Limiting Section 2's Scope to

Collegial Decision-Makers

The court's reliance on Butts to advance the view that

only collegial decision-makers are covered by §2 is also faulty.

"Butts was not based on a 'collegial decisionmaking' rationale,

nor was this concept even discussed. The Butts exception is

premised simply on the number of elected officials being elected

and the impediment to subdividing a single position so that

17

LULAC.minority voters have the opportunity to elect a 'share'."

Dissent at 9. The interpretation that only collegial-

decisionmaking offices elected at-large can be challenged under §2

is of the LULAC panel's own creation.

3. Butts Erroneously Interprets Amended §2

In carving out an exemption for single-person offices from

the restrictions of the Voting Rights Act, the Second Circuit in

Butts suggests that Congress was not concerned with ensuring that

minority voters have an equal opportunity to participate in the

election of a particular group of elected office-holders — single

person officeholders. Nothing in the legislative history of the

Voting Rights Act, nor in the Supreme Court's decision in Ginqles,

in fact, suggests that single-person offices, such as mayor or

governor, are entitled to greater deference than other offices open

to the electorate. The Butts court cites no statutory language,7

legislative history or even relevant §2 cases8 which support its

radical approach to interpreting the scope of amended §2.

The legislative history of the Act shows, in fact, that

7The statutory language of the Act in defining "voting"

clearly contradicts the Butts court's holding. See Voting Rights

Act, Section 14 (c)(1) supra at n.l.

8The Butts court rests its conclusion'entirely on two §5 cases

neither of which involved a challenge to a majority vote

requirement for a single—person office. See City of Richmond_v .

United States. 422 U.S. 358 (1975)(finding that §5 was not violated

by annexation of white suburb) ; City of Port Arthur v._United

States. 459 U.S. 159 (1982) (affirming district court's order

enjoining use of majority vote requirement for at-large

councilmanic elections).

18

Congress was concerned with eradicating discrimination

"comprehensively and finally" from every election in which voters

were eligible to cast ballots. S. Rep at 13. Even elections for

referenda, therefore, must comply with §2. See Voting Rights Act,

Section 14(c)(1), 42 U.S.C. §1973 1 (c)(1); see also S.Rep. at 37.

The Butts court further errs in its interpretation of the

focus of the Act. According to the Butts court, the Voting Rights

Act was not meant to abolish electoral laws or structures that

"make it harder for the preferred candidate of a racial minority

to be elected . . . the Act is concerned with the dilution of

minority participation and not the difficulty of minority victory."

779 F. 2d at 149. The Supreme Court in Ginqles, expressly

contradicts this interpretation of the focus of amended §2. In

Ginqles. the Court struck down the use of an electoral scheme

precisely because it made it difficult for African American voters

to elect their preferred candidate to the North Carolina

legislature. The at-large structure in Ginqles did not entirely

inhibit African American voters from electing some candidates.

African American voters, in fact, "enjoyed. . . sporadic success

in electing their representatives of choice." 478 U.S. at 53. The

at-large structure combined with white bloc voting made it

difficult, absent special circumstances, for African American

voters to elect their preferred candidates.

Butts' creation of a single-member office exception is simply

inconsistent with the comprehensive scope of amended §2. If a New

York City law explicitly stated that candidates for mayor must run

19

in election after election until a white candidate received a

majority of the vote, §2 would clearly be violated. Similarly, if

Harris County were divided into fifty-nine judicial districts which

fragmented politically cohesive geographically compact communities

of African American voters, this districting scheme could also be

challenged under §2, even if that fragmentation were not the result

of intentional discrimination. A change from the election of

district judges to an appointive system could also be challenged

under §2.9 See House Report at 18 (identifying shifts from

elective to appointive systems as a potentially discriminatory

election practice). The function of judges as single or collegial

decision-makers would be irrelevant to whether such a cause of

action could be sustained under §2.

Discriminatory election schemes for single-person offices have

been struck down by this Court. In Bell v. Southwell, 376 F.2d 659

(5th Cir. 1967) , for example, this Court voided the results of a

Justice of the Peace election in which a white candidate defeated

a African American candidate, because the voting lists and booths

for that election were segregated. In that case, this court did

not analyze the role or function of the official on the ballot.

9Plaintiffs would have to prove either that the change was

enacted intentionally to discriminate against minorities or that

the effect of the change resulted in the inability of African-

American voters to participate in the political process. Such a

change, of course, would first be subject to the preclearance

requirements of §5 of the Voting Rights Act. Preclearance of this

change could be denied on the grounds that the change from an

elected to an appointive system violates §2. See Letter from

Assistant Attorney General, April 25, 1990, Attached at Appendix

"A" (objecting to changes in superior court judge elections in

Georgia based, in part, on their apparent violation of §2).

20

The court was only concerned with the fact that segregated election

practices offend the Constitution. Id. at 663. In fact, the

results of the election were voided, even though the African

American voting population was so small that if all the qualified

African Americans had voted in the election, the results would not

have been changed, and the white candidate would still have won.

Id. at 662. The holding in Butts that the rules for the election

of single-person offices are immunized from §2 application

therefore, is wrong in light of the statutory language, legislative

history and subsequent Supreme Court decision in Ginqles 10. It is

also inconsistent with the law of this Circuit.

III. Remedial Concerns Are Not Properly Addressed at the

Liability Stage of a Voting Rights Case

Despite its lengthy inquiry into the independent decision

making role of trial judges, the LULAC panel is clearly most

troubled by the prospect of carving up each of the challenged

counties into single-member judicial districts. Conceding the lack

of minority representation in the judiciary, the panel argues that

10The Supreme Court, in fact, has never focussed on the

function of an elected officer in striking down a discriminatory

election scheme. In Gray v. Sanders. 372 U.S. 368 (1963), for

instance, the Supreme Court struck down the use of Georgia's county

unit electoral system for the nomination for single-person

(Governor) and multi-member (legislators) officers. In finding that

the county unit system violated the Equal Protection Clause, the

Supreme Court drew no distinction between the function of the

multi-member and single-member officers at issue.

21

"the problems inherent in attempting to create a remedy for lack

of minority representation" in the challenged counties

"emphasiz[es]" the character of trial judges as single-office

holders. LULAC. Panel Op. at 35. The Panel's preoccupation with

the appropriateness and legality of a single-member district remedy

in this case is premature, and taints its review of the District

Court's finding of liability under §2.

A. The Proper Scope of the Liability Inquiry

Undoubtedly, the fashioning of an appropriate remedy which

will completely remedy the §2 violation with "certitude" is a

complex and daunting task for the parties and the reviewing court.

See, e.g.. Dillard v. Crenshaw. 831 F.2d at 252. In part because

of the complex and important nature of the task, the reviewing

court at the liability stage need not adopt, review or otherwise

engage in an analysis of the remedy best suited to cure the proven

violation. The trier of fact and the reviewing court at the

liability stage must limit its inquiry to an assessment of the

"impact of the contested structure or practice on minority

electoral opportunities." Ginqles. 478 U.S. at 44. At a separate

remedy hearing, the trier of fact has an opportunity to assess the

feasibility of the plans offered by the parties and rule on those

plans according. See. e.g.. Martin v. Allain, 700 F.Supp. 327

(S.D.Miss. 1988).

The LULAC panel's profound misgivings about a single-member

judicial district remedy underscores the importance of separating

22

the liability inquiry from the question of remedy. In a separate

remedial hearing, a full factual record related to a particular

remedial plan can be developed and reviewed. To cure the

violation, the State will also have the opportunity to submit its

own plan which protects its bona fide interests. At the liability

stage, the illustrative district maps offered by the plaintiffs at

trial do not provide any sound basis upon which the court may rule

on the appropriateness of a sub-districting remedy.

B. The LULAC Panel's Analysis of Sub-Districts

as a Remedy is Critically Flawed

As the basis for its analysis of remedy, the LULAC panel

refers to the illustrative sub-district plans offered by the

plaintiffs as actual remedial plans for each county. That is

incorrect. These plans by the plaintiffs solely to illustrate the

way in which the current system dilutes the voting strength of

African American voters. Plaintiff—intervenors showed, that

African Americans in Harris County are sufficiently numerous and

geographically compact to constitute a majority in a fairly drawn

single-member district plan. These maps were not intended to serve

as actual remedial plans. In sum, the illustrative hypothetical

plans show the possibility of alternatives to the existing

electoral structure that could provide African American voters with

a more equal opportunity to elect their preferred candidates.

["Gingles I districts"]. See Plaintiffs Exhibit H-04 ; HLA Exhibits

2a-2c. Unilaterally transforming these maps into actual remedial

23

plans, the LULAC panel concludes that "the remedy in this case

seems to lessen minority influence instead of increasing it."

Panel Op. at 35.

In creating illustrative Ginqles I districts both the

plaintiffs and Harris County plaintiff-intervenors developed sub

district maps which divided the county into districts equalling

the number of currently sitting district judges. For example,

plaintiffs' and plaintiff-intervenors' experts created 59

illustrative judicial electoral districts for Harris County, since

the county is served by 59 district judges. Referring specifically

to the plaintiffs' suggested plan for Harris County, which showed

that if the county-wide electoral system were changed, politically

cohesive African American voters could constitute a majority in at

least nine districts,11 the LULAC panel argues that "[m]inority

voters would have very little influence over the election of the

other 50 judges, for the minority population is concentrated in

those 9 subdivisions." Panel Op. at 36. An appropriate remedy

for Harris County, however, might not include the creation of 59

separate electoral districts in Harris County. So long as the

creation of a sub-districting plan fully cured the §2 violation,

it might take a number of different forms and might contain fewer

than 59 electoral districts in Harris County. The conclusions

drawn by the LULAC panel from the plaintiffs illustrative maps

11Plaintiff-intervenors ' expert testified that African American

in Harris County could constitute a majority in thirteen [13]

single-member districts. See. Plaintiff-Intervenor HLA Exhibits

2, 2a, 2b.

24

would be relevant only if these maps were submitted as remedial

plans once the liability phase of this case had been completed.

The LULAC panel's concerns about the creation of an appropriate

remedy should be properly considered by the district court on

remand. These legitimate concerns, however, should not infect this

court's review of the presence of underlying §2 liability.

1. The LULAC Majority's Analysis of the Plaintiffs'

District Plan Fails on Its Own Terms

Assuming that 59 separate judicial electoral districts would

be created in Harris County, the LULAC panel argues that African

American voters in Harris County would suffer greater injury under

a sub-district plan because "it is much more likely than not that

a minority litigant will be assigned to appear before a judge who

is not elected from a voting district with a greater than 50%

minority population." Panel Op. at 36. The panel calculates that

in Harris County, "a minority member would have an 84.75% chance

of appearing before a judge who as no direct political interest in

being responsive to minority concerns." Panel Op. at 36-37. Under

the current system, the panel reasons that "[m]inority voters.

. have some influence on the election of each judge," because they

are permitted to vote for every judicial race in their county.

Panel Op. at 36.

The panel's analysis simply does not hold up under close

scrutiny. Since all cases in the county are assigned to judges

randomly, Tr. at 4-255-256, no litigant in Texas should anticipate

25

appearing before a judge that he or she elected. In fact, no

evidence was introduced at trial to suggest that voters vote for

particular candidates because they expect to appear before them as

litigants. It would seem more likely that voters vote for

candidates who they anticipate will "administer and interpret the

law" in accordance with the voter's philosophy about the rules

under which their society should be governed. Chisom, 839 F.2d at

1065.

Moreover, maintaining the countywide election system gives

white litigants a virtual guarantee that they will appear before

judge who are the candidates of choice of the white community. If,

as the LULAC panel argues, a sub-district remedy would be

"perverse," Panel Op. at 38-39, then maintaining the current system

which, in effect, rewards whites who vote as a bloc against African

American sponsored African American candidates, would be obscene.

If indeed the panel is concerned that African American

litigants will not, under a sub-districting plan, appear before

African American judges, the its own analysis contradicts itself.

12The panel's entire discussion assumes that minority judges

will decide cases on the basis of race, instead of in accordance

with the law, and that African American litigants will therefore

wish to appear before African American judges. Nothing in the

record supports this assumption. It is offensive to the many

qualified minority candidates to assume that they will not apply

the law as impartially as currently sitting white judges do. No

witness or party in this case has ever claimed that he or she seeks

to influence the outcome of litigation by electing minority judges.

That is neither the anticipated nor desired outcome of this §2

challenge. Instead, the plaintiffs in this action simply seek an

equal opportunity to participate in all phases of the electoral and

political process. In keeping with that goal, plaintiffs seek the

right to elect candidates of their choice as district judges. As

the dissent points out, "[t]he majority's discussion approaches the

26

Under the current electoral system, only two African Americans have

been elected to serve as district judges in Harris County since

1980.13 It is difficult to understand how African Americans would

fare worse under an electoral scheme that would give them the

opportunity to elect 9 of the 59 judges.

The panel's concern that white judges outside the majority

African American sub-districts will not feel responsible to the

African American community merely supports the need for change in

the current system. Under the county-wide election scheme, none

of the 59 district judges in Harris County has any incentive to be

responsive to the minority community because African Americans make

up only 18% of the County's 1,266,655 registered voters.

Therefore, under the current system, district judges in Harris

County may "ignore minority interests." Ginqles, 478 U.S. at 48

n. 14.

Contrary to the defendants' argument, the election of judges

from sub-districts with countywide jurisdiction would not violate

the constitutional rights of voters. District judges in Texas

currently have statewide jurisdiction. See Nipper v. U—Haul, 516

S.W .2d 467 (Tex. Civ. App. 1974). This means that district judges

may hear cases anywhere in the State of Texas. Id.; see also, Reed

problem from the wrong direction; quite simply, the focus should

be on the rights of the voter, not the litigant." Dissent at 12-

13, n.12 .

130f the three sitting African American district judges in

Harris County, two are criminal court judges, and one is a family

law judge. No African American has ever been elected to a district

civil court bench. Tr. at 3-207.

27

v. State of Texas. 500 S.W.2d 137 (Tex. Crim. App. 1973). Often

judges sit in counties from which they were not elected in order

to help with docket control. Tr. at 5-120. Therefore, litigants

in Texas frequently appear before trial judges over whom they have

no electoral control. This political reality has been upheld in

a number of cases challenging the power of district judges in Texas

to hear cases outside their electoral district. See, e. q . , Nipper;

Reed. Other states have also upheld the constitutionality of

similar judicial electoral systems. See e.q., Holhouser v. Scott,

335 F.Supp. 928 (M.D.N.C. 1971) (upholding statute permitting

judges with statewide jurisdiction to be elected statewide or from

districts; also upholding transfer of district judges from one

district to another for temporary or specialized duty); Cox v .

Katz. 294 N .Y.S.2d 544 (1968) (upholding constitutionality of

electing judges with citywide jurisdiction from districts within

each borough). Moreover, in Martin v. Allain. the District Court

approved the election of chancery, circuit and county court judges

from sub-districts, while maintaining countywide jurisdiction for

the judges. 700 F.Supp 327,332 (S.D. Miss. 1988).

C. The LULAC Panel's Focus on a Sub-Districting Remedy

is Particularly Inappropriate in This Case Where

Plaintiff-intervenors Proposed Alternative Remedies

The Panel's reversal of the district court's decision, based

primarily on its analysis of a sub-districting remedy, is

particularly inappropriate in this case, where plaintiff-

intervenors in their complaint specifically pleaded that "the use

28

of a non-exclusionary at-large voting system could afford African

Americans an opportunity to elected judicial candidates of their

choice." HLA Complaint at ^42. The HLA plaintiff-intervenors

specifically stated that an at-large system using limited or

cumulative voting would give African American voters a more equal

opportunity to elect district judges. Id. The HLA plaintiff-

intervenors, therefore, recognized that alternative at—large

election schemes provide a viable alternative to sub—districting

to cure a proven §2 violation. So long as these modified at-large

methods of electing judges could completely cure the violation with

"certitude," they too would be acceptable remedies. See Dillard

v . Crenshaw County; see also Dillard v. Chilton County_Bd.— of

Educ.. 699 F.Supp 870 (M.D. Ala. 1988) summarily aff'd, 868 F.2d

1274 (1989) (adopting magistrate's recommendation that cumulative

voting be used for election of county commission and school board);

Dillard v. Town of Cuba, 708 F.Supp. 1244 (M.D. Ala. 1988) (limited

voting scheme acceptable under §2 for city council elections).

As the HLA plaintiff-intervenors alleged in their complaint,

single-member districts "are by no means the only alternative

electoral system" that can give minority voters the potential to

elect candidates of their choice. R. Engstrom, D. Taebel & R.

Cole, Cumulative Voting as Remedy for Minority Vote Dilution:__The

Case of Alamogordo, New Mexico. The Journal of Law & Politics, Vol.

V., No. 3 (Spring 1989).14 Both cumulative and limited voting

14In the case at hand, Dr. Engstrom testified as an expert for

plaintiffs and plaintiff-intervenors and Dr. Taebel testified for

both the State defendants and defendant-intervenors.

29

undercut the "winner-take-all" quality of at-large elections

whereby "a bare political majority of the electorate can elect all

the representatives and totally shut out a minority." Karlan, Maps

and Misreadings: The Role of Geographic Compactness in Racial

Vote Dilution Litigation. 24 Harv. C.R.-C.L.L.Rev. 173 (1989); see

also HLA Complaint at f39 ("district judges in Harris County run

in exclusionary at-large, winner-take-all, numbered place

elections."). Both these alternative at-large systems would

maintain the countywide election district, thus preserving the

State's articulated interest in avoiding the creation of sub

districts .

1. Limited Voting

In a limited voting electoral scheme the multimember district

is maintained, but "each voter has fewer votes than there are seats

to be filled: the voter is limited to voting for less than a full

slate." Karlan, supra at 224 (emphasis in original). Using a

mathematical equation, experts can calculate "the percentage of the

vote that will guarantee the winning of a seat [for the minority

group] even under the most unfavorable circumstances. '" Id. at 222

This calculation yields the number of votes which should be

allotted to each elector for that election. Each elector receives

the same number of votes.

One expert has concluded that "[ljimited voting is a viable

remedial system" for Harris County. Issacharoff, The Texas

Judiciary and the Voting Rights Act: Background and Options, at

30

18, Texas Policy Research Forum (December 4, 1989) attached at

Appendix "B". According to Professor Issacharoff, "voters would

be allowed to cast a number of ballots equal to roughly 60 percent

of the judicial offices to be filled at any given time." Id.

The constitutionality of limited voting systems has been

upheld in a number of states. See e.g.. Cintron-Garcia v. Romero-

Barcelo. 671 F.2d 1,6 ( 1st Cir.1982) (holding that limited voting

scheme for election of Commonwealth representative is "reasonable"

and facilitates minority representation); Hechinger v. Martin, 411

F.Supp. 650 (D.D.C 1976) (three-judge court) (upholding limited

voting scheme for District of Columbia city council elections)

aff'd per curiam. 429 U.S. 1030 (1977); LoFrisco v. Schaffer, 341

F.Supp. 743 (D.Conn 1972) (three-judge court) (limited voting

scheme for Conn, school boards upheld); Kaelin v. Warden, 334

F.Supp. 602, 605 (E.D. Pa. 1971) (Equal Protection Clause is not

violated by limited voting scheme, so long as each voter casts the

same number of votes); Blaikie v. Power. 243 N.Y.S.2d 185 (1963)

(upholding limited voting for some New York City Council elections

seats), appeal dism'd. 375 U.S. 439 (1964). Limited voting has

also been approved for the election of trial judges. In Orloski

v. Davis. 564 F.Supp. 526 (M.D. Pa. 1983), for instance, the

district court upheld the use of a limited voting scheme to elect

Pennsylvania's Commonwealth Court.15

15The Commonwealth Court's jurisdiction includes, in part,

"original jurisdiction over civil actions brought against the

Commonwealth and its officials... concurrent jurisdiction with the

Courts of Common Pleas over all actions brought by the

Commonwealth; exclusive (with specific exceptions) appellate

31

2. Cumulative Voting

A cumulative voting electoral scheme permits each voter "to

cast as many votes as there are seats to be filled,. . . [but]. .

a voter may cumulate or aggregate her support by giving preferred

candidates more than one vote." Karlan, supra at 231. A

mathematical equation can calculate "the percentage or proportion

of the electorate that a group must exceed in order to elect a

candidate of its choice, regardless of how the rest of the

electorate votes." R. Engstrom, D. Taebel, & R. Cole, supra at

478. (emphasis in original). Cumulative voting was used

successfully for over 100 years to elect the Illinois House of

Representatives. See Karlan, supra at n.250.

These modified at-large electoral systems, although best

explored at the remedy stage, clearly provide alternatives to

single-member district schemes. In light of these alternatives,

the LULAC panel's remedy concerns are both premature and unfounded.

IV. The District Court Properly Held that Under the Totality

of the Circumstances African American Voters in Harris

County Do Not Enjoy an Equal Opportunity to Elect Their

Preferred Candidates in District Judge Elections

jurisdiction over all appeals from Courts of Common Pleas involving

the Commonwealth, Commonwealth officials; secondary review of

certain appeals from Commonwealth agencies.... and exclusive

original. . . jurisdiction over election contests." 564 F.Supp.

526,532.

32

While implicitly recognizing the existence of underlying §2

liability in the election of district judges in Texas, see e.g.,

Panel Op. at 35; Dissent at 17-18, n.15 ("trial record is replete

with evidence [that] minorities are seldom ever able to elect

minority candidates to any of the at-large district court judge

positions available in the districts"), the LULAC panel opinion

never reached the question whether African Americans, in fact, have

an equal opportunity to elect their candidates of choice as

district judges in Harris County. In light of some of the

questions raised at oral argument however, HLA plaintiff—

intervenors will address below the only factual defense offered by

the defendants16 — that is, that African Americans lose district

judge elections because they vote and run as Democrats.

Despite their failure to prove this claim as either a matter

of fact or law, the defendants persist in arguing that partisan

politics rather than race explains the outcome of district judge

elections in Harris County. According to the defendants, elections

in Harris County are politically polarized, not racially polarized.

The defendants further argue that Judge Bunton's findings of

racially polarized voting were clearly erroneous, because he failed

to consider the role of partisan politics to explain the outcome

16The District Court's opinion and the original briefs of the

plaintiff-intervenors on appeal, detail the plaintiffs' proof of

the threshold Gingles factors and the existence of relevant Senate

Report Factors in Harris County. The only issue about which there

remains controversy regarding underlying §2 liability in Harris

County, is the District Court's analysis of existence of racially

polarized voting.

33

Defendants' argument, which seeks toof the elections analyzed.17

import a causation requirement into a §2 analysis squarely rejected

by Ginales and this Court, is wrong both as a matter of law and

fact.

Judge Bunton's findings are not clearly erroneous. The

district court properly applied, to the record in this case, the

standard methods for determining racially polarized voting and vote

dilution approved by the Supreme Court in Gingles and in every

decision in this Circuit. The unquestionable outcome of the

court's analysis revealed that white bloc voting in Harris County,

in combination with other Senate Factors, prevents African American

voters from electing district judges to office.

A. Congress Has Expressly Rejected a Causation Analysis

Every decision in this Circuit which has addressed the

question of the role of causation in an analysis of polarized

voting, has concluded that a court need not engage in an inquiry

into the motives of white voters in rejecting African American

17The Court relied on the testimony of plaintiff-intervenors'

expert, Dr. Richard Engstrom. Dr. Engstrom testified that voting

in district judge elections in Harris County is racially polarized.

In support of his conclusion, Dr. Engstrom analyzed the 17

contested district judge elections involving white and African

American candidates in Harris County since 1980. In 16 of those

17 elections, African American voters gave more than 95% of their

vote to the Black candidate. In those same elections, white voters

never gave more than 40% of their vote to the African American

candidate. Only 3 African American candidates have been successful

in contested district judge races in Harris County since 1980. Dr.

Engstrom concluded that district judge elections in Harris County

are racially polarized.

34

candidates. See Overton v. City of Austin. 871 F.2d 529,538 (5th

Cir. 1989); Campos v. City of Baytown. 840 F.2d 1240,1243 (5th Cir.

1988); Citizens for a Better Gretna v. City of Gretna. 636 F.Supp.

181113,1130 (E.D. La. 1986), aff'd. 834 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1987).

In Overton v. City of Austin, in particular, this Court held

that the analysis used by the district court in this case, which

focuses on the results of bivariate regression and homogenous

precinct analysis and supporting lay testimony, rather than

extrinsic factors such as political party, is an appropriate method

of determining the existence of legally significant racial bloc

voting. 871 F.2d at 538. Furthermore, a multi-variate analysis

while perhaps "helpful in determining whether racial polarization

exists,. . . in no way negate[s] the use of bi-variant regression

analysis to determine whether in fact polarization exists."

Gretna,. 636 F.Supp. at 1130.

This conclusion is compelled by Thornburg v. Ginqles. In

Gingles, the Supreme Court upheld the district court's finding of 18 * *

18This Circuit has consistently affirmed findings of racially

polarized voting in the lower court based on a statistical review

of white vs. minority candidate contests, using bivariate

regression and homogenous precinct analyses. See Campos v. City

of Baytown. 840 F.2d 1240,1243 (5th Cir. 1988); Gretna; LULAC v.

Midland ISP. 812 F.2d 1494,1501 n.14 (5th Cir. 1987), vacated on

other grounds. 829 F.2d 546 (5th Cir. 1987). These statistical

methods are standard in the literature for the analysis of racially

polarized voting. Gingles. 478 U.S. at 53 n.20. The causation

inguiry advocated by the defendants is at odds with these standard

methods of analysis. Attempting to determine the motive of white

voters in rejecting Black candidates "flies in the face of the

general use, in litigation and in the general social science

literature, of correlation analysis as the standard method for

determining whether vote dilution in the legal... sense exists."

Ginqles v. Edmisten. 590 F.Supp 345 at 368 n.32.

35

racially polarized voting, despite the defendants' arguments in the

lower court that experts must "factor in all of the circumstances

that might influence particular votes in a particular election,"

including political party. 19 Gingles v. Edmisten, 590, F.Supp. 345

(E.D. N.C. 1984) (three-judge court). Over these arguments, the

Supreme Court unanimously affirmed the District Court's findings.20

The approach advocated by the defendants and recently by Chief

Judge Tjoflat in an Eleventh Circuit concurrence in Solomon v.

Liberty County. No. 87-3406 (11th Cir. April 5, 1990),21 * is fraught

with dangers already anticipated by Congress. First, a test which

focused on the motives of white voters in voting against African

American candidates "would make it necessary to brand individuals

as racist in order to obtain judicial relief." S.Rep. at 36.

Congress specifically sought to avoid this outcome in amending §2.

19The District Court in Gingles, specifically found that the

white bloc vote which tended to defeat Black candidates was made

up of both Republicans and Democrats. 590 F.Supp at 368-369.

20In their Jurisdictional Statement to the Supreme Court, the

Gingles appellants specifically argued, as do the defendants in

this case, that extrinsic factors besides race best explained the

outcome of elections in the North Carolina legislative districts

at issue. See, Jurisdictional Statement of Appellants at 17-18,

Thornburg v. Gingles. The Supreme Court was not persuaded by this

argument.

21In Solomon v. Liberty County. No. 87-3406 (11th Cir. April

5, 1990), the Eleventh Circuit remanded to the district court a

claim brought by African American voters challenging the at-large

election of county commissioners and school board members. In one

of the three concurring opinions, Chief Judge Tjoflat argued that

the objective factors which make up the §2 results test "must show

that the voting community is driven by racial bias and that the

challenged scheme allows that bias to dilute the minority

population's voting strength," in order for plaintiffs to prevail.

Solomon v. Liberty County. Slip Op. at 22, (Tjoflat, J.,

concurring)(emphasis deleted).

36

Mindful of the fact that levelling charges of racism against

individual officials or entire communities" leads to divisiveness

in the commmunity, Congress specifically "avoid[ed the inclusion

of] highly subjective factors" in the "results" test. House Report

at 30; S.Rep. at 36 It is difficult to imagine a more potentially

divisive inquiry than attempting to prove that individual white

voters voted against a African American candidate because of the

candidate's race.22.

In addition, although under the defendants' analysis of racial

bloc voting the motives of each and every white voter who voted

against a African American candidate would be relevant to the

plaintiffs' case, it would be impossible for plaintiffs to meet

their burden because "[t]he motivation(s) of . . . individual

voters may not be subjected to. . . searching judicial inquiry."

Kirksev v. City of Jackson. Miss., 663 F.2d 659,662 (5th Cir 1981)

rehearing and rehearing en banc denied 669 F.2d 316 (5th Cir.

19 8 2 ) 23.

22Personal accounts of racial discrimination involving elected

officials, community leaders, neighbors, shopkeepers, banks and

ordinary citizens would also be relevant to establishing "the

interaction between racial bias in the community and the challenged

[electoral] scheme."

23Congress cited the near impossibility of meeting an intent

burden as a factor necessitating a return to a results-oriented

standard under §2. S.Rep. at 36; see also Gingles, 478 US at 43.

Congress was concerned, for instance, that "plaintiffs may face

barriers of 'legislative immunity' both as to the motives involved

in the legislative process, and as to the motives of the majority

electorate when an election law has been adopted or maintained as

the result of a referendum." S.Rep. at 37 (emphasis added).

Similar barriers would be faced by plaintiffs attempting to discern

the motives of white voters who did not vote for Black candidates.

37

Finally, contrary to the defendant's repeated assertions,

Congress' stated return to the standards developed in White,

Whitcomb and Zimmer does not support the introduction of extrinsic

factors into an analysis of racially polarized voting. Congress

has expressly interpreted White. Whitcomb and Zimmer as results

cases. S.Rep. at 28 (concluding that "White and the decisions

following it" required no proof of intent). Congress noted, in

fact, that "[i]n Whitcomb. plaintiffs conceded that there was no

evidence of discriminatory intent. If intent had been required to

prove a violation the opinion would have ended after it

acknowledged plaintiffs' concession." S.Rep. at 21. The courts

in White, Whitcomb and Zimmer simply recognized that "[i]t would

be illegal for an at-large election scheme for a particular... local

body to permit a bloc voting majority over a substantial period of

time consistently to defeat minority candidates or candidates

identified with the interests of a racial or language minority."

House Report at 30. Moreover, Congress clearly instructed that,

"[r]egardless of differing interpretations of White and Whitcomb.

. . . the specific intent of this amendment [to §2] is that the

plaintiffs may choose to establish discriminatory results without

proving any kind of discriminatory purpose." S.Rep. at 28

(emphasis added).

The arguments offered by the defendants in this case,

therefore, were expressly addressed and rejected by Congress in

amending §2.

Finally, even if defendants arguments were well-founded they

38

failed to prove at trial that, in fact, factors other than race

explain the loss of African-American candidates in district judge

elections. The defendants' own expert, Dr. Taebel, articulated the

proper test to determine whether party and not race explains the

outcome of these elections: "the minority candidate who run [sic]

on a partisan basis should receive the same support as any White

candidate or any other candidate might." Tr. at 5-189. "In other