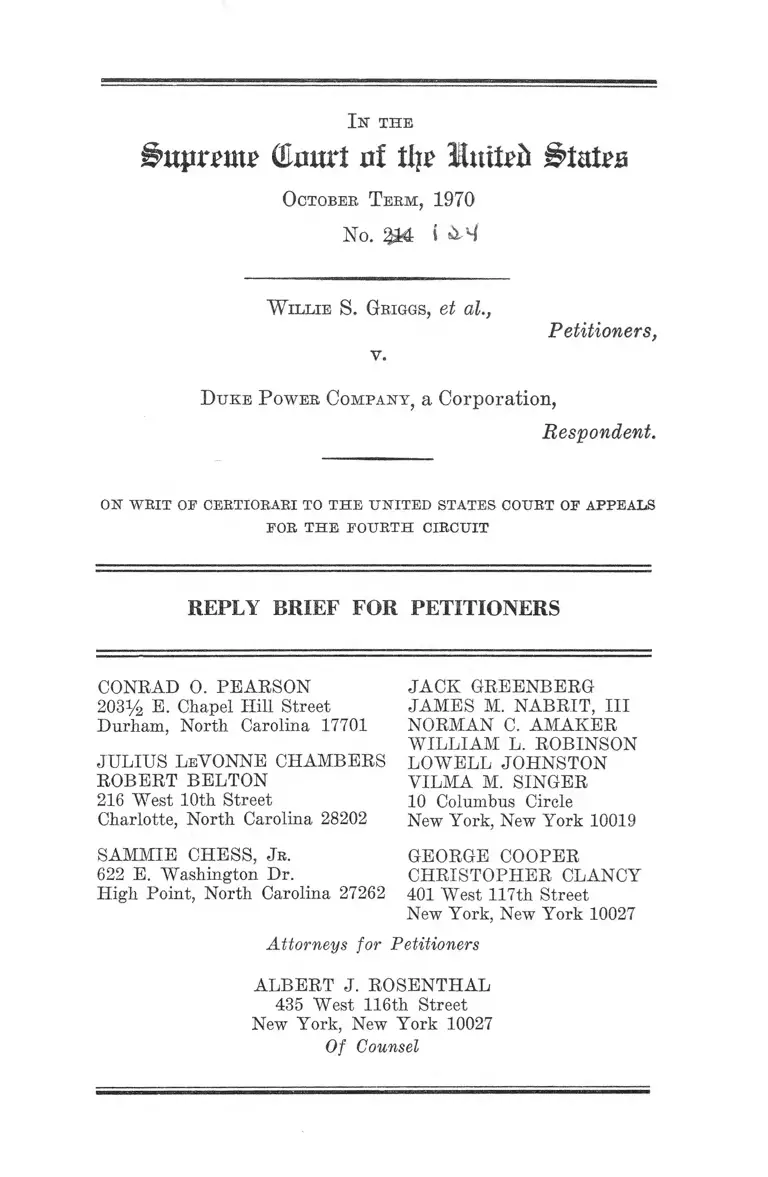

Griggs v. Duke Power Company Reply Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Griggs v. Duke Power Company Reply Brief for Petitioners, 1970. 363ebcd1-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5076ab3b-5a1f-49c7-9473-b973253e0cfe/griggs-v-duke-power-company-reply-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

(EmirJ at % llniUb States

October T erm, 1970

No. <m »^

W illie S. Griggs, et al.,

v .

Petitioners,

Duke P ower Company, a Corporation,

Respondent.

ON W R IT OE CERTIORARI TO T H E U N ITED STATES COURT OE APPEALS

EOR T H E EO U RTH CIRCUIT

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

CONRAD 0. PEARSON

2031/2 E. Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina 17701

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

ROBERT BELTON

216 West 10th Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

SAMMIE CHESS, J k.

622 E. Washington Dr.

High Point, North Carolina 27262

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN C. AMAKER

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

LOWELL JOHNSTON

VILMA M. SINGER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

GEORGE COOPER

CHRISTOPHER CLANCY

401 West 117th Street

New York, New York 10027

Attorneys for Petitioners

ALBERT J. ROSENTHAL

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Argument

I. The Record Does Not Substantiate, and, if

Anything, Contradicts Respondent’s Claim

That the Test/Diploma Requirement Is Ne

cessitated by Its Business Needs ................. 3

II. The Respondents’ Tests Are Not Given a

Privileged Status by § 703(h) of Title VII .... 7

III. The Legal Precedents Support the Peti

tioner’s Position ............................................. 10

Conclusion ......................... 12

T able op Authorities

Cases:

Arrington v. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Au

thority, 306 F. Supp. 1355 (D. Mass. 1969) .............. 11

Dobbins v. Electrical Workers Local 212, 292 F. Supp.

413 (S.D. Ohio 1968) ................................................ 11

Gregory v. Litton Systems, Inc., ----- F. Supp. ------ ;

63 Lab. Cas. (J9485 (C.D. Calif. July 28, 1970) ...... 11

Hicks v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 3 CCH Emp. Prac.

Dec. ([8037 (E.D. La. Nov. 6, 1970) ........................ 2,11

Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers v.

United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969), cert,

denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970) ....................................... 12

H

PAGE

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., 3 CCH

Emp. Prac. Dec. H8021 (8th Cir. Oct. 28, 1970) ...... 2

United States v. Sheetmetal "Workers, Local 36, 416

F.2d 123 (8th Cir. 1969) ........................................... 12

Statute:

42 U.S.C. §2000e et seq., Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 ................................................................. 7, 8

Section 703(h), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(h) ..................... 7,8

Federal Regulations on Testing:

EEOC, Guidelines on Employment Selection Proce

dures, 35 Fed. Reg. 12333 (Aug. 1, 1970) ................. 10

Other Authorities:

91st Cong., 2d Sess. 23, H.R. Rep. No. 91-1434 (1970) .... 10

91st Cong., 2d Sess. S. Rep. No. 91-1137 (1970) ...... 8

In the

Supreme (Emtrt nf % Itttteb States

Octobeb Teem, 1970

No. i t e f

W illie S. Griggs, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

Duke P qweb Company, a Corporation,

Respondent.

ON W EIT OP OEETIOEAEI TO T H E U N ITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS

POE T H E PO U E TH CIRCUIT

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Argument

The respondents in the lower courts in this case suc

ceeded in reducing Title YII to dealing only with situations

where there is a- showing of racial animus and they continue

to pursue that notion in their briefs here. This approach

has been rejected by the vast majority of District Courts

and Courts of Appeals, which have made it clear that the

focus must be on the impact and effect of practices rather

than merely the motivation behind those practices. Where

an apparently neutral practice has a serious discriminatory

impact and effect, it has repeatedly been held to violate

Title YII unless a continuation of the practice is neces

sitated by the employer’s job performance needs. These

cases involved seniority, nepotism, and use of arrest rec

2

ords, as well as tests, and they make it clear that to know

ingly and consciously persist in a practice having dis

criminatory impact and not necessitated by job performance

needs is to engage in discrimination within the meaning of

Title VII. (See the discussion at pp. 25-28 of brief for

Petitioner.)

Two important new decisions, released after the filing of

our main brief, reaffirm and expand this body of authority

supporting petitioners. First, in Parham v. Southwestern

Bell Telephone Co., 3 CCH Emp. Prac. Dec. H8021 (8th

Cir. Oct. 28,1970), the Court of Appeals reversed a District

Court decision strongly relied upon in Brief for Respon

dent (p. 44-45). The District Court had supported the em

ployer’s use of a high school diploma requirement; but the

Court of Appeals pointed out that the record contained in

sufficient data to rule on this point. 3 CCH Emp. Prac. Dec.

at p. 6051. The Court of Appeals went on to hold that the

recruitment system of the employer which appeared racially

neutral was unlawful because of its statistical impact and

effect. 3 CCH Emp. Prac. Dec. at p. 6050-51. The second

new decision, Hicks v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 3 CCH Emp.

Prac. Dec. 8037 (E.D. La. Nov. 6, 1970), is even more on

point. The Crown Zellerbach case involved a use of the

same Wonderlic and Bennett tests used by defendant Duke

Power Co. here. The court plainly held that such tests

could not be used unless justified by business necessity es

tablished after full study and evaluation. The court

explained:

“Without such study, no employer can have any con

fidence in the reasonableness or validity of his tests;

and he therefore cannot in good faith assert that busi

ness necessity demands that these tests of unknown

value be used. Title VII does not permit an employer

to engage in unsubstantiated speculation at the expense

of Negro workers.

3

Since it is clear that Crown Zellerbach has engaged

in no significant study to support its testing program,

the program is unlawful.” 3 CCH Bmp. Prac. Dec. at

p. 6108

Precisely the same analysis should he controlling here.

In the present case, the discriminatory impact of the test/

diploma requirement is clear and incontrovertible. The only

justification for this requirement advanced by respondents

is their wishful thinking, wholly unsubstantiated and, if

anything, contradicted by the record. The decision below

can be affirmed only if Title YII is to be narrowly limited

to precluding only racially motivated practices—which as

Judge Sobeloff, dissenting below, warns, would reduce the

law to “mellifluous but hollow rhetoric.”

The Brief for Respondent attempts to develop three

arguments in support of its position: (I) that the test/

diploma requirement is based upon “legitimate business

purpose,” (II) that the company’s tests are privileged under

§ 703(h) of Title YII, and (III) that legal precedents do

not support petitioner’s position. As already explained in

petitioner’s main brief, each of these arguments is un

founded. However, we will briefly reply here to each of

these arguments in the order set out by respondents.

I. The record does not substantiate, and, if anything,

contradicts respondent’s claim that the test/diploma re

quirement is necessitated by its business needs.

First, contrary to respondent’s claim, their expert wit

ness, Dr. Dannie Moffie, did not participate in establishing

either the diploma or test requirement and he offered no

conclusion that either of these requirements were necessi

tated by the company’s job performance needs. (See Brief

for Respondent at pp. 15-16, 18)

4

As to the high school diploma requirement, Dr. Moffie

testified only that “the assumption is” that the requirement

is job-related, not that he had verified or even supported

the assumption (A. 181a). This is understandable since

Dr. Moffie did not participate in establishing the require

ment in the mid-1950’s (A. 177a) and was never asked to

ratify it. He was qualified as an expert only in “Industrial

and Personnel Testing” (A. 164a). He was asked on direct

examination to testify only to the appropriateness of the

tests used by the company (E. 162a-175a). Eespondents

have tried to read an endorsement of their diploma require

ment into Dr. Moffie’s testimony, but he clearly did not give

such endorsement. See Brief for Petitioner at page 42

n. 51.

As to the test requirement, on which Dr. Moffie did testify

specifically, even the respondents are not able to claim that

Dr. Moffie endorsed the requirement as being required by

job performance needs. Eather, Dr. Moffie testified only

that the test was a reasonable substitute for the diploma

requirement (A. 180a-182a). He rendered no judgment on

the reasonableness of the test as an independent require

ment. This was a relatively easy judgment to make since

test scores correlate well with academic level, as compared

to their poor correlation with industrial job potential. Dr.

Moffie could not responsibly comment on the test as an in

dependent requirement in relation to job performance needs

because of insufficient study and evaluation. See Brief for

Petitioner at pp. 31-37.

Second, although the respondents make much of the fact

that “minimum occupational scores in the utility industry”

on the Wonderlie test generally coincide with the score re

quired by the company, see Brief for Despondent at p. 18,

this claim is fully nonsensical. These so-called “minimum

occupational scores” are merely the “number of questions

5

correctly in 12 minutes reported by one or more companies

participating in the study” (A. 138b). Since the Duke

Power Co. participated in the study (A. 169a), these mini

mum scores may only be confirming what Duke itself re

ported. It is difficult to imagine a more obvious case of

attempting to lift oneself by one’s own bootstraps.

Thus, the only thing in the record truly offering any

support for the company’s diploma/test requirement is

the testimony of its official, Mr. A. C. Theis.

As to the diploma requirement, Mr. Theis merely testi

fied that the Company had found in the past that certain

employees were unable to progress in certain jobs because

of the limited reading and reasoning abilities. “This,” he

said, “was why we embraced the High School education as

a requirement” (A. 93a). This fond hope was, and still is,

unsupported by any study, evaluation, or substantiation.

Mr. Theis did not even determine that the poor employees

were non-high school graduates. The record indicates, if

anything, that non-high school graduates are able to pro

gress just as well and perform just as well in the jobs at

the Duke Power Co. as high school graduates. See data

cited in Brief for Petitioner at p. 37 n.47 and Brief for the

United States as Amicus Curiae at p. 20 n.22. This data

confirms findings made in numerous professional studies

that requirements like that of a high school diploma bear

no significant relationship to job success. See Brief for

Petitioner at p. 37. As to the test requirement, the testi

mony of Mr. Theis is even weaker. He said only that he

adopted these tests “because the white employees that hap

pened to be in Coal Handling at the time, were requesting

some way that they could get from Coal Handling into the

Plant jobs. . . .” (A. 200a).

There may be other times and other places where the use

of a diploma/test requirement can be justified despite its

6

gross discriminatory impact on black employees. However,

it is intolerable that unsubstantiated speculation which is

inconsistent with the facts in the record and which is based

on a desire to help some white employees, should be ac

cepted as a sufficient basis of justification.

The unreasonableness of permitting these requirements

to stand in this case is further compounded by the fact that

the primary effect of the requirements here is to deny black

employees their only opportunity for good paying jobs.

The good paying jobs which petitioners seek in the coal

handling department are ones staffed primarily with non-

high school graduates. These jobs were traditionally re

served for whites under the Duke Power Company’s prior

practice of naked racial segregation of jobs. Each of the

petitioners has worked for many years for Duke in the

traditionally black category of “semi-skilled laborer,” per

forming a wide variety of mechanical and industrial tasks

which are analogous to duties in the coal handling depart

ment. See Brief for Petitioner at pp. 39-41. The diploma/

test requirement is the only thing standing between these

blacks and a decent job opportunity. On the other hand,

no white employee in the plant is cut off from a good pay

ing job by the diploma/test requirement since all white em

ployees are in departments which lead to well paying jobs.

See Brief for Petitioner at pp. 4-7.1

1 Respondents argue that the number of Negroes affected by the

test requirement was not disproportionately greater than the num

ber of whites so affected, because the requirement applied to 11

Negroes and 9 whites. Brief for Respondent at p. 23. Respondent

neglects to note, however, that all of the whites were in the coal

handling department where they were eligible for promotion to

jobs paying as much as $3.31 per hour even if they failed to meet

the diploma/test requirement, while all of the Negroes were in the

labor department where they could expect to earn no more than

$1,895 per hour unless they met the diploma/test requirement

(A. 72b). (The foreman job in the labor department is reserved

for high school graduates (A. 63b). Thus the burden of the re

7

II. The respondents’ tests are not given a privileged

status by %703(h) of Title VII.

Our view of the legislative history of the §703 (h) is fully

developed in our main brief (pp. 46-50), as well as in the

brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae (pp. 21-30),

the brief of the Attorney General of the State of New

York as Amicus Curiae in Support of Reversal (pp. 15-20),

and Judge Sobeloff’s dissenting opinion below. We believe

that this legislative history clearly shows that §703(h) was

not intended to offer any protection for tests which are

not justified by job performance needs. At the very least,

.however, the legislative history can be said to be conflicting

and uncertain as to the precise nature of the justification

required for test use. In such a situation, a subsidiary

clause like §703(h) must be harmonized with the overall

purpose of the statute and cannot be read to undercut that

overall purpose as respondents suggest.

The one thing that is undisputably clear about §703 (h)

is that it was directed at the problem raised by the Motorola-

Illinois FEPC case. This case involved a situation where

tests were struck down because of their adverse impact on

black applicants without considering whether in fact that

adverse impact was related to Motorola’s job performance

needs. The question raised by that case was very different

from that raised by this case where petitioners concede that

job performance needs are a reasonable and acceptable

justification for test use. Because of ambiguous draftsman

ship, §703(h) could be read to apply to the problem

quirement on the black employees is of a much different magni

tude than that imposed on white employees. Moreover, even putting

aside this differential burden, the imposition of a requirement

which would adversely affect 11 blacks and 9 whites is dispropor

tionately affecting the Negroes in the context of a plant with only

14 black employees and 81 white employees.

8

presented in this ease, bnt to do so would take the pro

vision out of its legislative context and cause a result

which was not really being considered or focused upon by

Congress in its consideration of §703(h). We submit that

it would be a distortion of §703 (h) to apply it to create a

privileged status for the tests used in this case.

Subsequent legislative developments bear out petitioner’s

view of §703(h). The respondents have attempted to but

tress their argument by referring to the fact that a May,

1968, amendment to Title VII requiring that tests be job-

related was not enacted. Brief for Respondent at p. 35.

Respondents’ reliance is misplaced. First, the May, 1968

amendment was not defeated, as respondents claim, but

rather was not acted upon by Congress. Since the amend

ment was only a minor part of a larger bill designed to

give the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission cease

and desist powers, the fact that the bill died without Con

gressional action can hardly be read to say much about

the test amendment. Subsequently, on August 21, 1970

(after the filing of our main brief), the Senate Committee

on Labor and Public Welfare reported out a new bill giv

ing cease and desist powers to the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission. See S. Rep. No. 91-1137, 91st

Cong., 2d Sess. (1970). The Committee report makes it

clear that this new bill is directed at precisely the kind of

problem raised in this case.

“In 1964, employment discrimination tended to be viewed

as a series of isolated and distinguishable events, for

the most part due to ill-will on the part of some iden

tifiable individual or organization. It was thought that

a scheme that stressed conciliation rather than com

pulsory processes would be most appropriate for the

resolution of this essentially ‘human’ problem, and that

litigation would be necessary only on an occasional

9

basis in the event of determined recalcitrance. This

view has not been borne out by experience.

“Employment discrimination, viewed today, is a far

more complex and pervasive phenomenon. Experts

familiar with the subject generally describe the prob

lem in terms of ‘systems’ and ‘effects’ rather than

simply intentional wrongs, and the literature on the

subject is replete with discussions of, for example, the

mechanics of seniority and lines of progression, per

petuation of the present effects of pre-act discrimina

tory practices through various institutional devices,

and testing and validation requirements. In short, the

problem is one whose resolution in many instances re

quires not only expert assistance, but also the tech

nical perception that a problem exists in the first place,

and that the system, complained of is unlawful.”

The Committee report goes on to explain that, this recogni

tion of the scope of discrimination requires the creation

of an expert commission with cease and desist powers.

However, and this is the crucial point for us, the Commit

tee did not think it necessary to include any significant

amendment in the substantive violation provisions of Title

VII in order to enable this commission to accomplish its

purposes. In other words, the Senate Committee believed

that discriminatory “systems” and “effects” were already

covered by the substantive provisions of the Act. The bill

proposed by this Committee report was passed by the

whole Senate in September, 1970. ----- Cong. Ree. ------

(daily ed. September, 1970).

A similar bill has also been reported out of Committee

in the House of Representatives. The House bill specifically

requires that tests be “directly related to the determination

of bona fide occupational qualifications reasonably necessary

10

to perform the normal duties of the particular position con

cerned.” H. R. Rep. No. 91-1434, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. 23

(1970). The House Committee report makes it clear that

the present language of Title VII already requires that tests

he related to job performance needs, but that this amend

ment is necessary to legislatively overrule the misinterpre

tation given the statute by the Court of Appeals in this case

below. Id. at 10-11. At this date, the House bill is pending

in the Rules Committee. Because of the vagaries of the

legislative process, the eventual outcome of this legislation

giving cease and desist powers to the EEOC will have to

await further developments. Whatever the outcome, how

ever, the crucial lesson for this case is that the substantive

committees of both houses of Congress and the entire

Senate are on record as supporting the interpretation of

Title YII being advanced by petitioners in this case. If

subsequent legislative developments are ever to cast any

light on the proper interpretation of a statute, it is clear

that this case presents the strongest possible instance of

such subsequent legislative development supporting the pe

titioners’ position.

III. The legal precedents support the petitioner’s posi

tion.

First, contrary to respondents’ claim, it is clear that the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission opposes the

imposition of tests and/or diploma requirements under cir

cumstances such as those presented here. This is made

clear in the Amicus brief filed by the Solicitor General on

behalf of the EEOC. Moreover, the EEOC Guidelines

on Employee Selection Procedures, 35 Fed. Reg. 12333

(Aug. 1,1970) are unmistakeable in this regard. The EEOC

guidelines cover both tests and educational requirements.

See id. at §1609.2. In this regard, the EEOC is fully sup

ported by the Office of Federal Contract Compliance in its

11

order covering Validation of Tests by Contractors and Sub

contractors, 33 Fed. Reg. 14392 (1968).

Furthermore, it is clear that the decisions in numerous

analagous cases below affirm the correctness of petitioners’

interpretation of Title VII. On the specific question of

tests, the decisions in Hicks v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 3

CCH Emp. Prac. Dec. f[8037 (E.D. La. Nov. 6, 1970) (dis

cussed at p. 2 supra) and Arrington v. Massachusetts

Bay Transportation Authority, 306 F. Supp. 355 (D. C.

Mass. 1969), are foursquare in requiring substantial study

and evaluation to justify use of tests having a discrimina

tory impact. To the same effect is Bobbins v. Electrical

Workers Local 212, 292 F. Supp. 413 (S. D. Ohio 1968).

Respondents attempted to distinguish Dobbins on the

ground that the purpose of the tests there was to discrim

inate. However, among the things held unlawful in Dobbins

was a test which the court acknowledged to be “objectively

fair and objectively fairly graded” on the ground that it

was unnecessarily difficult. Id. at 433-34. That of course

is the precise problem here: the test is unnecessarily and

unreasonably difficult in relation to many, if not all, of the

jobs to which it applies. It is also clear that numerous cases

involving analogous practices, rather than tests as such,

support petitioners’ position. Thus, in striking down the

use of arrest records as a hiring criterion, the court in

Gregory v. Litton Systems, Inc., 63 Lab. Cas. 1J9485 held:

“In a situation of this kind, good faith in the origina

tion or application of the policy is not a defense. An

intent to discriminate is not required to be shown so

long* as the discrimination shown is not accidental or

inadvertent. The intentional use of a policy which in

fact discriminates between applicants of different races

and can reasonably be seen so to discriminate, is inter

dicted by the statute, unless the employer can show

12

a business necessity for it. In this context, ‘business

necessity’ means that the practice or policy is essential

to the safe and efficient operation of the business.

Paper-makers Local 189 v. United States [416 F.2d 980

(5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970)] As

previously stated, no such justification or necessity has

been shown for the policy involved in this case.”

Similarly, in cases involving seniority and nepotism the

courts have found that the particular practices involved

were adopted innocently by the employer and bore some

relationship to the employer’s business. However, require

ments were struck down under Title VII because the em

ployer’s business interests could be adequately protected

by excluding unqualified employees without the imposition

of an arbitrary requirement which had a great discrimina

tory impact on black workers. See Local 189, United Paper-

makers and Paper Workers v. United States, 416 F. 2d 980

(5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied 397 U.S. 919 (1970); United

States v. Sheetmetal Workers, Local 36, 416 F.2d 123 (8th

Cir. 1969). This point is more fully described and docu

mented in our main brief at pp. 22-29.

CONCLUSION

Respondent’s brief persists in misconceiving the issue

raised by this case. The company believes that we seek

to “attribute to the respondent a base motive and sinister

intent to discriminate against its Negro employees.” Brief

for Respondent at p. 54. As we have tried to make clear,

that is not our purpose. It would serve the interests of no

one if Title VII were reduced to a statute requiring claims

of malice and sinister intent to be established. Rather, it is

petitioners’ position that respondents have taken a set of

requirements which are neutral on their face and may be

13

reasonably applied in certain situations, and misapplied

those requirements to the disadvantage of its black workers

in the Labor Department. This misapplication of a neutral

practice, whether maliciously intended or not, has the effect

of and does discriminate within the meaning of Title VII.

It has denied petitioners the opportunity which Title VII

extends to every man and woman—the right to be judged

on his or her own individual merits rather than under

arbitrary and discriminatory requirements. It should be

declared unlawful.

Respectfully submitted,

CONRAD 0. PEARSON

203% E. Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina 17701

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

ROBERT BELTON

216 West 10th Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

SAMMIE CHESS, J r .

622 E. Washington Dr.

High Point, North Carolina 27262

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN C. AMAKER

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

LOWELL JOHNSTON

YILMA M. SINGER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

GEORGE COOPER

CHRISTOPHER CLANCY

401 West 117th Street

New York, New York 10027

Attorneys for Petitioners

ALBERT J. ROSENTHAL

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

Of Counsel

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 219