Appendix

Public Court Documents

October 9, 1967 - December 11, 1967

100 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Green v. New Kent County School Board Working files. Appendix, 1967. e63e01e5-6c31-f011-8c4e-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/50a340e7-057a-49fd-a0c5-6d4ff202260d/appendix. Accessed February 12, 2026.

Copied!

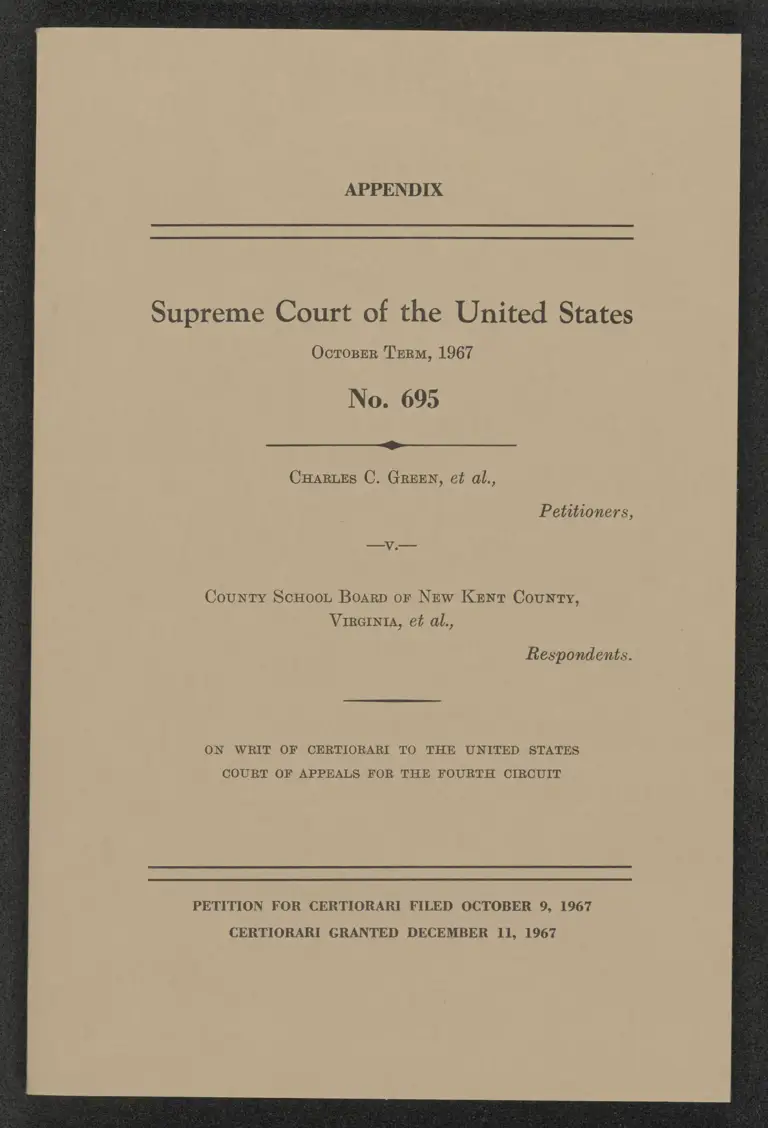

APPENDIX

Supreme Court of the United States

OctoBER TERM, 1967

No. 695

afm

CuaArLEs C. GREEN, et al.,

Petitioners,

County ScHoOoL Boarp or NEw KENT CouNTy,

VIRGINIA, et al.,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

PETITION FOR CERTIORARI FILED OCTOBER 9, 1967

CERTIORARI GRANTED DECEMBER 11, 1967

—

—

—

—

—

c

m

e

S

E

NE

E

s

R

E

t

e

5

0

HIS

o

t

t

SR

el

E

S

m

o

r

a

c

o

en

os

3

P

S

:

R

r

T

m

e

e

T

T

—

.

—

.

R

—

_

on

m

n

ncn

eine

.

a

INDEX

PAGE

District Court Docket heel . .....o......ccoemeresrmrenensgonnoranns la

COMPIAINL ch oes ster iessirminnineserssissnssiesamonssnrspsargeasmashinsan 3a

Motion to Dismiss ..... wa abies Rah teed 13a

Order on Motion {0 Dismiss .i....cciceeerirrinnciiiiimsnmorinesns 14a

Plaintiffs’ Interropalorion i. ii cscdmmmnnrmnmmes 15a

ANBWOL .......ccoconviisionesemisaciasnsterioisssmpsntonsoidssciammmssssrsnsiisutnss 21a

Defendants’ Answers to Plaintiffs’ Interrogatories .... 23a

Plan for School Desegregation ........ccsmmmoesscessmreoanseace 34a

First Memorandum of the Distriet Court .................... 47a

Wiret Order of the Distriet Court ............c.onccncionines 49a

Defendants’ Plan Supplement ...................cn iia, 50a

Plaintiffs’ Exception to Plan Supplement ................. 52a

Final Memorandum of the District Court .................. 53a

Pinal Order of the District Court .............oonea..n.. 62a

|

ii

Decision of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Clrenit 2. lif oi

Opinions of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Clremit .........oocors tiie iiss ssenzensibiominss

Judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Hourth Clrenit «............cc..c.cic ci iieeiini soc nensienninns

Order Extending Time to File Petition for Writ of

COTLIOYAYE .......i.voo0vsioeinsieissiicvrssmsisiessonpisnsni fos doiiotioni are asia

Order Allowing Cerliorari ..........coeudimschiiminmiimis

PAGE

63a

65a

90a

District Court Docket Sheet

4266—New Kent

DATE

1965

March 15

Apr. 5)

May 3

[13 53

[44 Z

[14 24

June 1

[44 8

1966

May 4

PROCEEDINGS

Complaint filed, summons issued.

* * *

Motion to dismiss filed by County School Board

of New Kent Co., W. R. Davis, E. P. Binns,

Jr., W. J. Wallace, Jr. and Harry S. Mount-

castle, ind. & as members of the County

School Board and Byrd W. Long, Div.

Supt. of Schools of New Kent Co., Va.

Motion for consolidation of motion to dismiss

with hearing on merits, for requirement of

answer by defts and for fixing of trial date

filed by pltfs.

Order deferring ruling on motion to dismiss;

directing defts. to answer on or before 6-1-65;

directing Clerk to call case at next docket

call, ent. 5-5-65. * * *

Interrogatories filed by plfs.

Order extending time to 6-8-65 for deft. School

Board to file answers to interrogatories ent.

5-24-65. * * *

Answer filed by defts.

Answer to interrogatories filed by County

School Board of New Kent Co., Va. Exhibits

attached

* * ¥

Tria Proceebpings—Butzner, J.: Parties ap-

peared by counsel. Issues joined. Discussion.

Court to enter order.

2a,

DATE PROCEEDINGS

May 4 * * * Motion of defendants for 30 days within

which to file Plan, granted.

3 10 Plan of desegregation filed by School Board.

17 Memorandum of the court filed

4 “ Order that defts/ motion to dismiss denied;

Pltfs. prayer for an unjunction restraining

school construction & purchase of school sites

denied; Defts. granted leave to submit on or

before June 6, 1966 amendments to their plan

which will provide for employment & assign-

ment on non-racial basis. Pending receipt of

these amendments to their plan which will

defer approval of plan & consideration of

other injunctive relief; Pltfs. motion for

counsel fees denied; Case will be retained

upon docket with leave granted to any party

to petition for further relief; Pltfs. shall re-

cover their costs to date.; ent. & filed; * * *

June 6 Motion for leave to file & request for approval

of a plan supplement filed by defts. together

with plan supplement.

4 10 Exceptions to plan supplement filed by pltf.

June 10 Ix Open Courr—Butzner, J.: Counsel dis-

cussed exceptions to Plan. Court will ap-

prove Plan.

py 16 Notice of Appeal from order of 5-17-66 filed by

plfs.

* % @

# 28 Memorandum of the Court filed.

Order approving Plan adopted by the New

Kent County School Board, ent. 6-28-66.

Case to be retained on docket. * * *

3a

Complaint

(Filed March 15, 1965)

1

1. (a) Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Title

28, United States Code, Section 1331. This action arises

under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States, Section 1, and under Title 42, United

States Code, Section 1981, as hereafter more fully appears.

The matter in controversy, exclusive of interest and costs,

exceeds the sum of Ten Thousand Dollars ($10,000.00).

(b) Jurisdiction is further invoked under Title 28, United

States Code, Section 1343(3). This action is authorized by

Title 42, United States Code, Section 1983 to be commenced

by any citizen of the United States or other person within

the jurisdiction thereof to redress the deprivation under

color of state law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom

or usage of rights, privileges and immunities secured by

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States and by Title 42, United States Code, Seec-

tion 1981, providing for the equal rights of citizens and

of all persons within the jurisdiction of the United States,

as hereafter more fully appears.

II

2. Infant plaintiffs are Negroes, are citizens of the

United States and of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and

are residents of and domiciled in the political subdivision

of Virginia for which the defendant school board maintains

and operates public schools. Said infants are within the

4a

age limits or will be within the age limits to attend, and

possess or upon reaching such age limit will possess all

qualifications and satisfy all requirements for admission

to, said public schools.

3. Adult plaintiffs are Negroes, are citizens of the United

States and are residents and taxpayers of and domiciled

in the Commonwealth of Virginia and the above mentioned

political subdivision thereof. Kach adult plaintiff who is

named in the caption as next friend of one or more of the

infant plaintiffs is a parent, guardian or person standing

in loco parentis of the infant or infants indicated.

4. The infant plaintiffs and their parents, guardians and

persons standing in loco parentis bring this action in their

own behalf and, there being common questions of law and

fact affecting the rights of all other Negro children attend-

ing public schools in the Commonwealth of Virginia and,

particularly, in the said political subdivision, similarly sit-

uated and affected with reference to the matters here in-

volved, who are so numerous as to make it impracticable

to bring all before the Court, and a common relief being

sought as will hereinafter more fully appear, the infant

plaintiffs and their parents, guardians and persons stand-

ing in loco parentis also bring this action, pursuant to Rule

23(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, as a class

action on behalf of all other Negro children attending or

who hereafter will attend public schools in the Common-

wealth of Virginia and, particularly, in said political subdi-

vision and the parents and guardians of such children sim-

ilarly situated and affected with reference to the matters

here involved.

Ha

5. Further, the adult plaintiffs bring this action pursu-

ant to Rule 23(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

as a class action on behalf of those of the citizens and tax-

payers of said political subdivison who are Negroes; the

tax raised contribution of persons of that class toward the

establishment, operation and maintenance of the schools

controlled by the defendant school board being in excess

of $10,000.00. The interests of said class are adequately

represented by the plaintiffs.

III

6. The Commonwealth of Virginia has declared public

education a state function. The Constitution of Virginia,

Article 1X, Section 129, provides:

“Free schools to be maintained. The General As-

sembly shall establish and maintain an efficient system

of public free schools throughout the State.”

Pursuant to this mandate, the General Assembly of Vir-

ginia has established a system of public free schools in the

Commonwealth of Virginia according to a plan set out in

Title 22, Chapters 1 to 15, inclusive, of the Code of Vir-

ginia, 1950. The establishment, maintenance and adminis-

tration of the public school system of Virginia is vested

in a State Board of Education, a Superintendent of Public

Instruction, Division Superintendents of Schools, and

County, City and Town School Boards (Constitution of

Virginia, Article IX, Sections 130-133; Code of Virginia,

1950, Title 22, Chapter 1, Section 22-2).

IV

7. The defendant School Board exists pursuant to the

Constitution and laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia as

6a

an administrative department of the Commonwealth, dis-

charging governmental functions, and is declared by law

to be a body corporate. Said School Board is empowered

and required to establish, maintain, control and supervise

an efficient system of public free schools in said political

subdivision, to provide suitable and proper school build-

ings, furniture and equipment, and to maintain, manage

and control the same, to determine the studies to be pur-

sued and the methods of teaching, to make local regulations

for the conduct of the schools and for the proper discipline

of students, to employ teachers, to provide for the trans-

portation of pupils, to enforce the school laws, and to per-

form numerous other duties, activities and functions essen-

tial to the establishment, maintenance and operation of the

public free schools in said political subdivision. (Constitu-

tion of Virginia, Article IX, Section 133; Code of Virginia,

1950, as amended, Title 22.) The names of the individual

members of the defendant School Board are as stated

in the caption and they are made defendants herein in their

individual capacities.

8. The defendant Division Superintendent of Schools,

whose name as such is stated in the caption, holds office

pursuant to the Constitution and laws of the Common-

wealth of Virginia as an administrative officer of the pub-

lic free school system of Virginia. (Constitution of Vir-

ginia, Article IX, Section 133; Code of Virginia, 1950, as

amended, Title 22.) He is under the authority, supervision

and control of, and acts pursuant to the orders, policies,

practices, customs and usages of the defendant School

Board. He is made a defendant herein as an individual

and in his official capacity.

Ta

9. A Virginia statute, known as the Pupil Placement

Act, first enacted as Chapter 70 of the Acts of the 1956

Extra Session of the General Assembly, viz. Article 1.1 of

Chapter 12 of Title 22 (Sections 22-232.1 through 22-232.17)

of the Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended, confers or pur-

ports to confer upon the Pupil Placement Board all power

of enrollment or placement of pupils in the public schools

in Virginia and to charge said Pupil Placement Board to

perform numerous duties, activities and functions per-

taining to the enrollment or placement of pupils in, and the

determination of school attendance districts for, such pub-

lic schools, except in those counties, cities or towns which

elect to be bound by the provisions of Article 1.2 of Chapter

12 of Title 22 (Sections 22-232.18 through 22-232.31) of

the Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended.

10. Plaintiffs are informed and believe that in execut-

ing its power or purported power of enrollment or place-

ment of pupils in and determination of school districts

for the public schools of said political subdivision, the

Pupil Placement Board will follow and approve the recom-

mendations of the defendant School Board unless it appears

that such recommendation would deny the application of a

Negro parent for the assignment of his child to a school

attended by similarly situated white children.

11. The procedures provided by the Pupil Placement

Act do not provide an adequate means by which the plain-

tiffs may obtain the relief here sought.

v

12. Notwithstanding the holding and admonitions in

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) and

8a

349 U. S. 294 (1955), the defendant School Board main-

tains and operates a biracial school system in which certain

schools are designated for Negro students only and are

staffed by Negro personnel and none other, and certain

schools are designated for white students or primarily for

white students and are staffed by white personnel and none

other. This pattern continues unaffected except in the few

instances, if any there are, in which individual Negroes

have sought and obtained admission to one or more of the

schools designated for white students. The defendants have

not devoted efforts toward initiating nonsegregation in the

public school system, neither have they made a reasonable

start to effectuate a transition to a racially nondiscrimina-

tory school system, as under paramount law it is their duty

to do. Deliberately and purposefully, and solely because of

race, the defendants continue to require or permit all or

virtually all Negro public school children to attend schools

where none but Negroes are enrolled and none but Negroes

are employed as principal or teacher or administrative

assistant and to require all white public school children

to attend school where no Negroes, or at best few Negroes,

are enrolled and where no Negroes teach or serve as prinei-

pal or administrative assistant.

13. Heretofore, petitions signed by several persons

similarly situated and conditioned as are the plaintiffs with

respect to race, citizenship, residence and status as tax-

payers, were filed with the defendant School Board, asking

the School Board to end racial segregation in the public

school system and urging the Board to make announcement

of its purpose to do so at its next regular meeting and

promptly thereafter to adopt and publish a plan by which

racial discrimination will be terminated with respect to

9a

administrative personnel, teachers, clerical, custodial and

other employees, transportation and other facilities, and

the assignment of pupils to schools and classrooms.

14. Representatives of the plaintiff class forwarded

said petitions to the defendant School Board with a letter,

copy of which was sent to each member of the defendant

School Board, part of which is next set forth:

“ 2 % % In the Light of the following and other court

decisions, your duty [to promptly end racial segrega-

tion in the public school system] is no longer open to

question:

Brown v. Bd. of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) ;

Brown v. Bd. of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955) ;

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958);

Bradley v. School Bd. of the City of Richmond,

317 F 2d 429 (4th Cir. 1963);

Bell v. Co. School Ed. of Powhatan Co., 321 F

2d 494 (4th Cir. 1963).

“We call to your attention the fact that in the last

cited case the unyielding refusal of the County School

Board of Powhatan County, Virginia, to take any

initiative with regard to its duty to desegregate schools

resulted in the board’s being required to pay costs of

litigation including compensation to the attorneys for

the Negro school children and their parents. We are

advised that upon a showing of a deliberate refusal

of individual school board members to perform their

clear duty to desegregate schools, the courts may re-

quire them as individuals to bear the expense of the

litigation.

10a

“In the case of Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S.

526 (1963) the Supreme Court of the United States

expressed its unanimous dissatisfaction with the sloth-

fulness which has followed its 1955 mandate in Brown

v. Board of Education, saying: ‘The basic guarantees

of our Constitution are warrants for the here and now

and, unless there is an overwhelmingly compelling rea-

son, they are to be promptly fulfilled.” ”

15. More than two regular meetings of the defendant

School Board have been held since it received the petitions

and letter above referred to. Neither by word or deed has

the defendant School Board indicated its willingness to end

racial segregation in its public school system.

74 §

16. In the following and other particulars, plaintiffs suf-

fer and will continue to suffer irreparable injury as a

result of the persistent failure and refusal of the defen-

dants to initiate desegregation and to adopt and implement

a plan providing for the elimination of racial discrimina-

tion in the public school system.

17. Negro public school children are yet being edu-

cated in inherently unequal separate educational facilities

specially sited, built, equipped and staffed as Negro schools,

in violation of their liberty and of their right to equal

protection of the laws.

18. Negro adult citizens are yet being taxed for the

support and maintenance of a biracial school system the

very existence of which connotes a degrading classification

of the citizenship status of persons of the Negro race, in

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

11a

19. Public funds are being spent and will be spent by

the defendants for the erection of schools and additions to

schools deliberately planned and sited so as to insure or

facilitate the continued separation of Negro children in the

public school system from others of similar age and quali-

fication solely because of their race, contrary to the pro-

visions of the Fourteenth Amendment which forbid gov-

ernmental agencies, whether acting ingeniously or ingenu-

ously, to make any distinctions between citizens based

on race.

20. This action has been necessitated by reason of the

failure and refusal of the individual members of the defen-

dant School Board to execute and perform their official

duty, which since May 31, 1955 has been clear, to initiate

desegregation and to make and execute plans to bring about

the elimination of racial discrimination in the public school

system.

yu

WHEREFORE, plaintiffs respectfully pray:

A. That the defendants be restrained and enjoined from

failing and refusing to adopt and forthwith implement

a plan which will provide for the prompt and efficient elimi-

nation of racial segregation in the public schools operated

by the defendant School Board, including the elimination of

any and all forms of racial discrimination with respect to

administrative personnel, teachers, clerical, custodial and

other employees, transportation and other facilities, and

the assignment of pupils to schools and classrooms.

B. That pending the Court’s approval of such plan the

defendants be enjoined and restrained from initiating or

12a

proceeding further with the construction of any school

building or of any addition to an existing school building

or the purchase of land for either purpose to any extent

not previously approved by the Court.

C. That the defendants pay the costs of this action in-

cluding fees for the plaintiffs’ attorneys in such amounts

as to the Court may appear reasonable and proper and that

the plaintiffs have such other and further relief as may be

Just.

/s/ S. W. Tucker

Of Coumsel for Plaintiffs

* #* *

13a

Motion to Dismiss

(Filed April 5, 1965)

Now come the County School Board of New Kent County,

Virginia, W. R. Davis, KE. P. Binns, Jr., W. J. Wallace, Jr.,

and Harry S. Mountcastle, individually and as members of

the County School Board, and comes Byrd W. Long, Divi-

sion Superintendent of Schools of New Kent County, Vir-

ginia, and move the Court to dismiss the Complaint herein

upon the following grounds:

1. The Complaint fails to state a claim upon which

relief can be granted.

(Signature of Counsel Omitted)

14a

Order on Motion to Dismiss

The Court defers ruling on the motion to dismiss. The

defendants are directed to answer on or before June 1,

1965.

The Clerk is directed to call this case at the next docket

call.

Let the Clerk send copies of this order to counsel of

record.

/s/ JorN D. BuTzNER, JR.

United States District Judge

May 5, 1965

15a

Plaintiffs’ Interrogatories

(Filed May 7, 1965)

Plaintiffs request that the defendant School Board, by

an officer or agent thereof, answer under oath in accordance

with Rule 33, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, the follow-

ing interrogatories:

1. List for each public school operated by the defendant

School Board the following:

a. Date on which each school was erected;

b. Grades served by each school during the 1964-65

school term;

c. Planned pupil capacity of each school;

d. Number of white pupils in attendance at school

in each grade level as of most recent dates for which

figures are available for 1964-65 term;

e. Number of Negro pupils in attendance at school

in each grade level as of most recent date for which

figures are available for 1964-65 term;

f. Number of Negro teachers and other administra-

tive or professional personnel and the number of white

teachers, ete., employed at each school during 1964-65

school term;

g. Pupil-teacher ratio at each school during 1964-

65 school term (most recent available figures);

h. Average class size for each school during 1964-

65 school term (most recent available figures);

i. Name and address of principal of each school.

16a

2. Furnish a map or maps indicating the attendance

areas served by each school in the system during the 1963-

64 term and the 1964-65 term. If no such map or maps can

be furnished, state where such maps or other descriptions

of the attendance areas may be found and inspected.

3. State the number of Negro pupils and the number of

white pupils, by grade level, residing in each attendance

area established by the School Board during the 1964-65

school term. If definite figures are unavailable, give the

best projections or estimates available, stating the basis

for any such estimates or projections.

4. State whether any pupils are transported by school

buses to schools within the school division, and if there are

any, give the average daily attendance of transported stu-

dents during 1964-65 term, stating separately the number

of white pupils and the number of Negro pupils in the ele-

mentary grades and in the high schools and in the junior

high schools.

5. Furnish a map or maps indicating the bus routes in

effect throughout the school division during the 1963-64

term and for the 1964-65 term (indicate for each bus route

the name and address of the bus driver and the race of the

students transported).

6. State with respect to the 1964-65 term, the total num-

ber of white pupils who reside in the attendance area of

an all-Negro school, but were in attendance at an all-white

or predominantly white school. Indicate with respect to

such pupils the following:

a. Number, by grade, residing in the attendance

area of each Negro school;

17a

b. The schools actually attended by white pupils

residing in the attendance area of each Negro school.

7. State the total number of Negro pupils who were

initially assigned to attend all-white or predominantly white

schools for the first time during either the 1963-64 school

term or the 1964-65 term. Give a breakdown of these totals

by schools and grades.

8. State whether during the 1964-65 term it was neces-

sary at any schools to utilize for classroom purposes any

areas not primarily intended for such use, such as library

areas, teachers’ lounges, cafeterias, gymnasiums, ete. If so,

list the schools and facilities so utilized.

9. State whether a program or course in Distributive

Education is offered in the school system and if so at what

schools it is offered.

10. Are any special teachers for subjects such as art and

music provided ¢

11. If so, state:

a. The number of such special teachers in the sys-

tem;

b. The number of full-time special teachers;

c. The number of part-time special teachers;

d. The schools to which they are assigned for the

current school year;

e. The schools to which they were assigned for the

preceding school year.

18a

12. Indicate whether a program of vocational education

was offered in any school or schools in the system during

the 1963-64 or the 1964-65 school term.

13. If so, state for each such year the name of each vo-

cational education course at each school and the number

of pupils enrolled therein; and give the number of indi-

viduals teaching vocational education at each school.

14. Furnish a statement of the curriculum offered at each

junior high school and each high school in the system dur-

ing the 1964-65 term.

15. Furnish a list of the courses of instruction, if any,

which are available to seventh grade students who attend

junior high schools in the system but are not available to

those seventh grade pupils assigned to elementary schools.

16. State whether any summer school programs operated

by the School Board have been operated on a desegregated

basis with Negro and white pupils attending the same

classes.

17. Are any buildings of frame construction presently

being utilized for schools? If so, which ones?

18. Are any of the school buildings in need of major

repairs? If so, which ones?

19. State with respect to any new school construction

which is now contemplated, the following with respect to

each such project:

a. Location of contemplated school or addition;

19a

b. Size of school, present and proposed number of

classrooms, grades to be served, and projected ca-

pacity;

c. Estimated date of completion and occupancy;

d. Number of Negro pupils and number of white

pupils attending grades to be served by such school

who reside in existing or projected attendance area

for such school.

20. State as to each teacher and principal first employed

by the School Board during the school year 1964-65 and

each of the four preceding school terms the following:

a. His or her name, age at time of such employment,

sex, race;

b. Initial date of employment by the defendant

School Board;

c. Teaching experience prior to employment by de-

fendant School Board;

d. College from which graduated and degrees

earned ;

e. Major subjects studied in college and in graduate

school;

f. Certificate from State Board of Education held

at time of initial employment by defendant School

Board, date thereof, and specific endorsements thereon;

g. The school and (elementary) grade or (high

school) subjects which he was assigned to teach at

time of initial employment;

h. Ratings earned for each year since initial employ-

ment by defendant School Board.

20a

21. Are any records maintained which reflect the turn-

over of teachers in each school?

22. If so, state:

a. Type of records maintained;

b. For what periods such records are maintained;

c. Where they are located;

d. In whose custody they are maintained.

23. Are any records maintained which reflect the mobil-

ity of children in and out of the school system and in and

out of specific schools, including transfers and dropouts?

24. If so, state:

a. Type of records maintained;

b. Where these records are located;

c. In whose custody they are maintained.

25. State the amount of funds received through programs

of Federal assistance to education during each of the school

sessions 1963-64 and 1964-65.

26. State whether any pledge of non-discrimination has

been signed by or on behalf of defendant School Board.

27. Give a copy of any plans for desegregation submitted

to the Department of Health, Education and Welfare or

to any other agency of the State or Federal Government.

PLease TAKE NOTICE that a copy of such answers must

be served upon the undersigned within fifteen days after

service.

/s/ HENRY L. Marsa III

Of Counsel for Plaintiff's

21a

Answer

(Filed June 1, 1965)

The undersigned defendants for Answer to the Complaint

exhibited against them say as follows:

1. These defendants deny that the amount in contro-

versy herein exceeds the sum of Ten Thousand Dollars

($10,000.00) as alleged in paragraph 1 (a) of the Com-

plaint.

2. These defendants deny that this Court has jurisdie-

tion under Title 28, United States Code, Section 1331 or

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1343(3) or Title 42,

United States Code, Section 1983 to grant any of the relief

prayed for in the Complaint.

3. The allegations of paragraphs 2 and 3 of the Com-

plaint are neither admitted or denied but the defendants

believe the allegations to be essentially true.

4. These defendants specifically deny that there are

questions of law and fact affecting the rights of all other

Negro children attending public schools in the said po-

litical subdivision and call for strict proof thereof and of

the fact that it is impracticable to bring all before the

Court who desire the relief being sought. These defen-

dants affirmatively allege that, as will hereinafter more

fully appear, the Constitutional and statutory rights of

all children in the said political subdivision, in so far as

public schools are concerned, are protected by the defen-

dants and the desire for the relief being sought is common

only to the named plaintiffs.

5. These defendants deny that grounds for a class ac-

tion exist as alleged in paragraph 5 of the Complaint and

22a

deny that those constituting the group seeking relief herein

contributed taxes in excess of $10,000.00 and call for strict

proof.

6. The allegations of paragraphs 6, 7, 8 and 9 of the

Complaint are admitted insofar as they assert the existence

of various Constitutional and statutory provisions of the

Commonwealth of Virginia. These defendants are not re-

quired and therefore do not admit or deny the accuracy

of the plaintiffs interpretation of the provisions of law to

which reference is made.

7. These defendants believe the allegations of paragraph

10 to be correct except that they believe that the Pupil

Placement Board would refuse to follow any recommen-

dations which denied an application due to the race of the

applicant whether the applicant be Negro or white.

8. These defendants, in answer to paragraph 11 of the

Complaint, assert that the assignment procedures avail-

able to the plaintiffs afford an adequate means for ob-

taining all rights to which they are entitled.

9. The allegations of paragraphs 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17,

18, 19 and 20 are denied except that the defendants admit

having received the petition and letter referred to in para-

graphs 13 and 14.

10. Infant plaintiffs and all others eligible to enroll in

the pupil schools in the political subdivision are permitted,

under existing policy, to attend the school of their choice

without regard to race subject only to limitations of space.

WaHaEREFORE, defendants pray to be dismissed with their

costs.

(Signature of Counsel Omitted)

| 23a

Defendants’ Answers to Plaintiffs’ Interrogatories

(Filed June 8, 1965)

Now comes Byrd W. Long, Division Superintendent of

schools of New Kent County, Virginia, and submits the

following answers to interrogatories filed by the plaintiffs,

said answers correspond to the numbered paragraphs in

| the interrogatories, to-wit:

1. a. Date on which each school was erected:

1. New Kent High School erected 1930 (Addi-

tion 1934). Elementary Building erected 1954 (Ad-

dition 1961).

2. George W. Watkins High School erected 1950.

Elementary Building erected 1958 (Addition 1961).

b. Grades served by each school during the 1964-65

school term:

1. New Kent served grades one through twelve.

2. George W. Watkins served grades one through

twelve.

c. Planned pupil capacity of each school:

1. New Kent High School 207, New Kent Ele-

mentary School 330.

2. George W. Watkins High School 207, George

W. Watkins Elementary School 420.

d. Pupils by grades—New Kent (All White)

Elementary: 1-54; 2-61; 3-51; 4-57; 5-48; 6-54;

7-42.

High School: 8-41; 9-49; 10-42; 11-33; 12-20.

24a

e. Pupils by grades—George W. Watkins (All

Colored)

Elementary: 1-87; 2-73; 3-94; 4-79; 5-60; 6-77;

7-68.

High School: 8-49; 9-43; 10-34; 11-37; 12-38.

f. Negro school—1 Principal, 1 Librarian, 26 Teach-

ers, 1 Supervisor, 1 Counselor

White school—1 Principal, 1 Librarian, 26 Teach-

ers, 1 Supervisor, 1 Counselor

g. Pupil-teacher ratio at each school during 1964-65

school term: New Kent-22—George W. Watkins-28

h. Average class size for each school during 1964-65

school term, Grades 1-12: New Kent-21—George W.

Watkins-26

i. Name and address of principal of each school : Ger-

ald W. Tudor, New Kent High School, New Kent Vir-

ginia; Todd W. Dillard, George W. Watkins High

School, Quinton, Va.

2. New Kent County has no attendance areas. A map

of the County may be obtained from the Virginia Depart-

ment of Highways.

3. As stated in No. 2 above, New Kent County is not

divided into school attendance areas.

4. Eleven school buses transport pupils to the George

W. Watkins school. Ten school buses transport pupils to

the New Kent School. One bus transports 18 Indian chil-

dren to a Charles City School. By agreement this bus also

transports 60 Charles City children.

25a

White pupils transported—548

Negro pupils transported—710

5. Bus routes in 1963-64 and 1964-65 are the same.

See attached maps—mnames of drivers of buses are shown

on maps. (Exhibits A and B)

6. As stated in No. 2 and 3 above, New Kent County

is not divided into attendance areas.

7. New Kent County Schools have been operated on a

Freedom of Choice Plan administered by the State Pupil

Placement Board since the establishment of the Pupil Place-

ment Board. To September 1964, no Negro pupil had applied

for admission to the New Kent School and no White pupil

had applied for admission to the George W. Watkins School.

8. Both schools are crowded beyond capacity in the

high school departments.

New Kent High School: Two basement areas, a

conference room, stage dressing room, and the audi-

torium are used for classes.

George W. Watkins High School: Two basement

areas, clinic room, and a part of the Vocational Shop

are used for classes.

9. Distributive Education is not offered in either school.

10. There are special teachers for subjects such as art

and music.

11. a. New Kent High School—Part-time music teach-

er. George W. Watkins High School—Part-time music

26a

teacher. New Kent Elementary School—Part-time music

teacher.

b. One—New Kent School—Full time.

c¢. One—George W. Watkins School—Part-time.

d. Stated in b. and ec.

e. Same as stated in b. and ec.

12. Vocational Home Economics and Vocational Agri-

culture were offered in both schools during 1963-64 and

during 1964-65.

13. Substantially the same for 1964-65 and 1963-64.

New Kent High School offered Vocational Agricul-

ture and Home Economics. Vocational Agriculture:

1 teacher, 63 pupils. Home Economics: 1 teacher, 32

pupils.

George W. Watkins High School offered Vocational

Agriculture and Home Economics. Vocational Agri-

culture: 1 teacher, 52 pupils. Home Economics: 1 teach-

er, 56 pupils.

14. New Kent County has no junior high schools. Each

of the two schools are operated on the plan called the 7-5

plan, which consists of 7 elementary grades and 5 high

school grades.

Each high school offers the following: Academic

Curriculum, Vocational Curriculum, General Course.

The Academic Curriculum is geared mainly for pupils

preparing for college.

27a

The Vocational Course is offered pupils not planning for

college, and a boy may major in Agriculture; a girl in Home

Making; and a boy or girl may major in Commercial

courses.

Those pupils planning to seek work in general employ-

ment may enroll in a general course.

Each high school has a guidance counselor who attempts

to aid the pupil and parent in the selection of a course ac-

cording to the pupil’s aptitude and his desired type of

employment after graduation.

15. New Kent County has no Seventh grade pupils who

take courses in the high school department.

Each school in New Kent County is a combination high

school and elementary school, but teachers do not work

partly in high school and partly in elementary school.

16. The School Board of New Kent County offers no

summer school program in any school.

17. At the George W. Watkins School the Agriculture

building is a frame building.

18. Extensive repairs were made at both schools during

the summer of 1963 and 1964. No major repairs are needed

at either school at the present time.

19. a. New Kent School-—campus type addition. George

W. Watkins School campus type addition.

b. New Kent School—4 classrooms planned: 2 sev-

enth grade classrooms; 2 sixth grade classrooms; two

toilets to serve the four rooms. This addition will serve

6th & 7th grade pupils at the above school. George

28a

W. Watkins School—4 classrooms planned: 2 seventh

grade classrooms; 2 sixth grade classrooms; two toilets

to serve the four rooms. This addition will serve 6th &

7th grade pupils at the above school.

c. A completion date has not been set for this project

as State Literary Loan funds have not been released.

The two above projects will be let to bid at the same

time and one contract will be executed for both of the

projects.

d. New Kent County has no attendance areas.

20. George W. Watkins High School and Grade School:

a. Todd W. Dillard, Principal, Male, age 30, Negro

b. Employed April, 1964, effective July 1, 1964

c. Four years experience

d. B.S. Virginia State College—Work completed

for Masters Degree

e. Science and Mathematics Major

f. Collegiate Professional Certificate

g. Does not teach—full-time Principal

h. Rated as superior

New Kent High School and Grade School:

a. Gerald W. Tudor, Principal, Male, age 28, White

b. Employed July 14, 1964

c. Five years experience

d. B.S. East Carolina College—Work completed for

Masters Degree

29a

e. Physical Education

f. Collegiate Professional Certificate

g. Does not teach—full-time Principal

For information regarding teachers, see attached

Exhibit “0”,

21. Records in the School Board Office will reflect the

turnover of teachers in each school.

22. Contract with teachers are executed annually for

a period of one year. A report of teachers contracted with

for each year is filed in the school board office.

a. As stated above

b. For past 5 years

c. School Board Office

d. The Clerk of the School Board

23. Teachers’ attendance registers record entries, re-

entries and withdrawals. No other special records are kept.

24. Teachers registers

a. Same as above

b. School Board Office

c. Clerk of School Board

25. Federal Funds 1963-64

School Lunch ..................coccceemmsemsmimspmnsseces $ 4,554.68

Oy RE ARR RR 9,612.00

NDA ieee cence 1,572.00

BUWIAANCE o.oo ciniitecie tenses rs anninesas 2,000.00

otal $17,738.68

30a

Federal Frunds—Estimated—1964-65

School LUNCH... oi ioovreisinisrossincsessessnnivesos $ 5,500.00

PB... ceeovinicaviniircuntmnsiuisainsavnse bon sremsscnnonngys 9,800.00

2g 2100 BE DA RE in LR LS Me 7 1,750.00

CMIAINCE ..ocrcriocrersicinseiemsmesonrdies srsnisssiniionss 2,000.00

IPALOT oiosiiomsiinenssrcnursarvisbasnnissmivsnsinnreinsont iosnigencas $19,050.00

26. Yes

HEW Form 441

27. Plan to accompany HEW Form 441 has not been

completed at this date.

/s/ Byrp W. Long

Byrd W. Long, Division Superin-

tendent of Schools of New Kent

County, Virginia

*® * * 3* *

3la

Exhibit C

20. Continued

Paul Gilley, age 22, white, male, b. 1963, c¢. None, d.

V.P1, B.S, e. Agriculture, f. Collegiate Professional,

Agricultural, g. Agriculture, New Kent High School, h.

Teachers are not rated in this Division.

Edward J. Stansfield, age 24, white, male, b. 1961, c.

None, d. Houghton, B.A., e. Sociology, f. Collegiate, Soci-

ology, History, English, g. History, English, New Kent

High School.

Billy R. Ricks, age 21, white, male, b. 1964, c. None, d.

East Carolina, B.A., e. History and Social Science, f. Col-

legiate History and Social Science, g. History, New Kent

High School.

John E. Averett, age 25, white, male, b. 1963, c. 2 years,

d. University of Richmond, no degree, e. Physical Educa-

tion, f. Special License, g. Math, Physical Education, New

Kent High School.

Jayne P. Thomas, age 31, white, female, b. 1962, c. 2

years, d. Madison, B.M. Education, e. Music, f. Collegiate

Professional, Music, g. Music, New Kent High and Ele-

mentary School.

Mary W. Potts, age 38, white, female, b. 1963, c. 4 years,

d. Longwood, B.S., e. English, Chemistry, f. Collegiate

Professional 6th and 7th grades, g. 7th grade, New Kent

Elementary School.

Alice V. Fisher, age 56, white, female, b. 1963, c. 16

years, d. Mary Washington, no degree, e. Elementary Edu-

cation, f. Special License, g. Hth grade, New Kent Ele-

mentary.

32a

Shirley F. Francisco, age 31, white, female, b. 1964, ec. 2

years, d. Madison, no degree, e. Elementary Education, f.

Special License, g. 2nd grade, New Kent Elementary.

Patricia B. Averett, age 20, white, female, b. 1963, e.

None, d. Ferrum, no degree, e. Elementary Education, f.

Special License, g. 1st grade, New Kent Elementary School.

Murray Carson, age 53, white, male, b. 1964, c¢. None,

d. Averett, no degree, e. English and History, f. Special

License, g. 1/2 day English, New Kent High School.

Laurenstine Porter, age 22, Negro, female, b. 1964,

c. None, d. North Carolina College B.S., e. Library, f. Col-

legiate, Health and Physical Kducation, Library Science,

g. Librarian, G. W. Watkins High & Elementary School.

Guy A. Boykins, age 57, Negro, male, b. 1960, c. None,

d. Virginia Union University, A.B., e. Social Studies and

History, f. Collegiate Professional, English, g. Social Stud-

ies and History, G. W. Watkins High School.

James E. Coleman, age 23, Negro, male, b. 1964, c¢. None,

d. Virginia Union, no degree, e. Chemistry, f. Special Li-

cense, Science and Physical Education, g. Science and Phys-

ical Education, G. W. Watkins High School.

Edith Jackson, age 24, Negro, female, b. 1960, ¢. None,

d. Virginia Union, B.S., e. Business, f. Collegiate Profes-

sional, Business, g. Commercial, G. W. Watkins High

School.

Gloria Miller, age 41, Negro, female, b. 1964, c. 2 years,

d. Virginia Union, B.A., e. Elementary, f. Collegiate Pro-

fessional—English and History, g. English and French,

G. W. Watkins High School.

John A. Baker, age 39, Negro, male, b. 1961, c. 13 years,

d. Wilburforce University, B.S., e. Agriculture, f. Collegiate

Professional, g. Agriculture, G. W. Watkins High School.

33a

Charles J. Washington, Sr., age 53, Negro, male, b. 1962,

c. None, d. Virginia Union, B.A., e. English, f. Collegiate

Professional—English and Latin, g. English, G. W. Wat-

kins High School.

Seth Pruden, age 37, Negro, male, b. 1960, c. None, d.

Virginia Union, B.S., e. History, f. Collegiate Professional

—French and History, g. 7th grade, G. W. Watkins

Elementary School.

Phillip Battle, age 24, Negro, male, b. 1963, c. None, d.

St. Paul’s, B.A., e. History and Social Sciences, f. Col-

legiate—History and Social Sciences, g. 7th grade, G. W.

Watkins Elementary School.

Natalie Boykins, age 24, Negro, female, b. 1964, c¢. 2

years, d. Virginia State, B.A., e. Sociology, f. Collegiate—

Sociology, g. 6th grade, G. W. Watkins Elementary School.

Julia Boyce, age 34, Negro, female, b. 1961, c. 10 years,

d. Virginia State, B.S., e. English and Physical Education,

f. Collegiate Professional—All grade subjects in 6th and

7th, g. 5th grade, G. W. Watkins Elementary School.

Willie Gillenwater, age 34, Negro, female, b. 1963, c. 2,

d. Virginia Union, B.A., e. Elementary Education, f. Col-

legiate Professional—Knglish, g. 4th grade, G. W. Wat-

kins School—Elementary.

Audrey Dillard, age 28, Negro, female, b. 1963, c. 6 years,

d. Virginia State, A.B., e. Social Studies, f. Collegiate Pro-

fessional—History, g. 4th Grade, G. W. Watkins School

—Elementary.

Dorothy Joyner, age 28, Negro, female, b. 1961, ec. 3

years, d. Winston Salem, B.S., e. English & History, f. Col-

legiate Professional—KElementary, g. 2nd grade, G. W.

Watkins School—Elementary.

Susie Bates, age 23, Negro, female, b. 1962, c¢. None,

d. Virginia State, B.S., e. Elementary, f. Collegiate Pro-

fessional—Grades 1-7, g. 1st grade, G. W. Watkins School

—Elementary.

34a

Plan for School Desegregation

(Filed May 10, 1966)

New Kent County PusLic ScHOOLS

ProviDENCE FoRGE, VIRGINIA

I. AxxvuaL FreepoMm oF CHOICE OF SCHOOLS

A. The County School Board of New Kent County

has adopted a policy of complete freedom of

choice to be offered in grades 1, 2, 8, 9, 10, 11,

and 12 of all schools without regard to race, color,

or national origin, for 1965-66 and all grades

after 1965-66.

. The choice is granted to parents, guardians and

persons acting as parents (hereafter called

“parents”) and their children. Teachers, prin-

cipals and other school personnel are not per-

mitted to advise, recommend or otherwise in-

fluence choices. They are not permitted to favor

or penalize children because of choices.

II. PuriLs ExTERING FIRST GRADE

Registration for the first grade will take place,

after conspicuous advertising two weeks in ad-

vance of registration, between April 1 and May

31 from 9:00 A. M. {02:00 P, M.

When registering, the parent will complete a

Choice of School Form for the child. The child

may be registered at any elementary school in

this system, and the choice made may be for that

35a

school or for any other elementary school in the

system. The provisions of Section VI of this plan

with respect to overcrowding shall apply in the

assignment to schools of children entering first

grade.

IIT. PuriLs ExTeErRING OTHER GRADES

A. Each parent will be sent a letter annually ex-

plaining the provisions of the plan, together with

a Choice of School Form and a self-addressed

return envelope, by April 1 of each year for

pre-school children and May 15 for others.

Choice forms and copies of the letter to parents

will also be readily available to parents or stu-

dents and the general public in the school offices

during regular business hours. Section VI ap-

plies.

B. The Choice of School Form must be either mailed

or brought to any school or to the Superintend-

ent’s Office by May 31st of each year. Pupils

entering grade one (1) of the elementary school

or grade eight (8) of the high school must ex-

press a choice as a condition for enrollment. Any

pupil in grades other than grades 1 and 8 for

whom a choice of school is not obtained will be

assigned to the school he is now attending.

IV. PuriLs Newry ENTERING ScHOOL SYSTEM OR CHANG-

ING RESIDENCE WITHIN IT

A. Parents of children moving into the area served

by this school system, or changing their residence

within it, after the registration period is com-

36a

pleted but before the opening of the school year,

will have the same opportunity to choose their

children’s school just before school opens during

the week of August 30th, by completing a Choice

of School Form. The child may be registered at

any school in the system containing the grade

he will enter, and the choice made may be for

that school or for any other such school in the

system. However, first preference in choice of

schools will be given to those whose Choice of

School Form is returned by the final date for

making choice in the regular registration period.

Otherwise, Section V1 applies.

. Children moving into the area served by this

school system, or changing their residence within

it, after the late registration period referred to

above but before the next regular registration

period, shall be provided with registration forms.

This has been done in the past.

V. REesmENT AND NON-RESIDENT ATTENDANCE

This system will not accept non-resident students,

nor will it make arrangements for resident stu-

dents to attend public schools in other school

systems where either action would tend to pre-

serve segregation or minimize desegregation.

Any arrangement made for non-resident students

to attend public schools in this system, or for

resident students to attend public schools in an-

other system, will assure that such students will

be assigned without regard to race, color, or na-

tional origin, and such arrangement will be ex-

37a

plained fully in an attachment made a part of

this plan. Agreement attached for Indian chil-

dren.

VI. OVERCROWDING

A. No choice will be denied for any reason other

than overcrowding. Where a school would be-

come overcrowded if all choices for that school |

were granted, pupils choosing that school will be |

assigned so that they may attend the school of

their choice nearest to their homes. No preference

will be given for prior attendance at the school.

B. The Board plans to relieve overcrowding by

building during 1965-66 for the 1966-67 session.

VII. TRANSPORTATION Transportation will be provided on an equal basis

without segregation or other discrimination be-

cause of race, color, or national origin. The right |

to attend any school in the system will not be

restricted by transportation policies or practices. |

To the maximum extent feasible, busses will be |

routed so as to serve each pupil choosing any |

school in the system. In any event, every student

eligible for bussing shall be transported to the

school of his choice if he chooses either the for-

merly white, Negro of Indian school.

VIII. Services, FaciLiTies, ACTIVITIES AND PROGRAMS

There shall be no discrimination based on race,

color, or national origin with respect to any ser-

38a

vices, facilities, activities and programs spon-

sored by or affiliated with the schools of this

school system.

IX. STAFF DESEGREGATION

A. Teacher and staff desegregation is a necessary

part of school desegregation. Steps shall be taken

beginning with school year 1965-66 toward elimi-

nation of segregation of teaching and staff per-

sonnel based on race, color, or national origin,

including joint faculty meetings, in-service pro-

grams, workshops, other professional meetings

and other steps as set forth in Attachment C.

. The race, color, or national origin of pupils will

not be a factor in the initial assignment to a par-

ticular school or within a school of teachers, ad-

ministrators or other employees who serve pupils,

beginning in 1966-67.

. This school system will not demote or refuse to

reemploy principals, teachers and other staff

members who serve pupils, on the basis of race,

color, or national origin; this includes any de-

motion or failure to reemploy staff members be-

cause of actual or expected loss of enrollment in

a school.

. Attachment D hereto consists of a tabular state-

ment, broken down by race, showing: 1) the num-

ber of faculty and staff members employed by

this system in 1964-65; 2) comparable data for

1965-66 ; 3) the number of such personnel demoted,

discharged or not reemployed for 1965-66; 4)

39a

the number of such personnel newly employed for

1965-66. Attachment D further consists of a cer-

tification that in each case of demotion, discharge

or failure to reemploy, such action was taken

wholly without regard to race, color, or national

origin.

X. Pusricity AND CoMMUNITY PREPARATION

Immediately upon the acceptance of this plan by

the U. S. Commissioner of Education, and once a

month before final date of making choices in 1966,

copies of this plan will be made available to all

interested citizens and will be given to all tele-

vision and radio stations and all newspapers

serving this area. They will be asked to give

conspicuous publicity to the plan in local news

section of the Richmond papers. The newspaper

coverage will set forth the text of the plan, the

letter to parents and Choice of School Form.

Similar prominent notice of the choice provision

will be arranged for at least once a month there-

after until the final date for making choice. In

addition, meetings and conferences have been and

will be called to inform all school system staff

members of, and to prepare them for, the school

desegregation process, including staff desegre-

gation. Similar meetings will be held to inform

Parent-Teacher Associations and other local com-

munity organizations of the details of the plan,

to prepare them for the changes that will take

place.

XI. CERTIFICATION

This plan of desegregation was duly adopted by

the New Kent County School Board at a meeting

duly called and held on August 2, 1965.

Signed: a is

(Chairman, Superintendent or

other authorized official)

41a

Attachment A

(School Board Letterhead)

Date Sent to Parents

and Guardians:

May 15, 1966

CHOICE OF SCHOOL FORM

This form is provided for you to choose a school for your

child to go to next year. The form must be either mailed

or brought to any school or to the Superintendent’s office

at the address above by May 31, 1966.

I. Name'of CIQ =. FF dais an tea

Last First Middle

2. Date of Pupil’s Birth (if entering first grade)

3. Grade Pupil Blizibhle for... esecccieiiiee i venne

4 School Last Atlended ..............

42a

5. School Chosen (Mark X beside school chosen)

ou George W. Watkins High and Elementary

1-12 Quinton, Virginia

1] New Kent High and Elementary

1-12 New Kent, Virginia

A Samaria School (Indian)

1-12 Charles City, Va.

Bionature |...

Address

This block is to be filled in by the Superintendent’s office,

not by porents. School chosen: ............. coves School as-

gizned* or coi Yi different, explain: ...............

43a

Attachment B

(School Board Letterhead)

May 15, 1966

Dear Parent:

A plan for the desegregation of our school system has been

put into effect so that our schools will operate in all re-

spects without regard to race, color, or national origin.

The desegregation plan provides that each pupil and his

parent or guardian has the absolute right to choose each

year the school the pupil will attend. No teacher, prineci-

pal, or other school official is permitted to advise you, or

make recommendations or otherwise influence your deci-

sion. No child will be favored or penalized because of the

choice made.

Attached is a Choice of School Form listing the names and

locations of all schools in our system and the grades they

include. Please mark a cross beside the school you choose,

and return the form in the enclosed envelope or bring it

to any school or the Superintendent’s office by May 31, 1966.

No choice will be denied for any reason other than over-

crowding. Anyone whose choice is denied because of over-

crowding will be offered his choice from among all other

schools in the system where space is available in his grade.

School bus routes will be on a desegregated basis. There

will be no discrimination based on race, color, or national

origin in any school-connected services, facilities, activities

and programs.

44a

For pupils entering grades one (1) and eight (8) a Choice

of School Form must be filled out as a requirement for

enrollment. Children in other grades for whom no choice is

made will be assigned to the school they are presently at-

tending.

Sincerely yours,

Superintendent

45a

Attachment C

Additional Steps Toward Staff Desegregation

Below are possible steps toward faculty and staff desegre-

gation which have been taken in other school systems and

one or more of which you may deem appropriate for your

system to adopt at this time. Please indicate by checking

the appropriate box or boxes and attach this page to the

plan when submitting it.

L All members of the supervisory staff will be as-

signed to serve schools, teachers and pupils without

regard to race, color or national origin.

2. [1 Teachers and staff members who serve more than

one school, such as librarians, music and art teach-

ers, nurses, counselors will be assigned to serve

schools, teachers and pupils without regard to race,

color, or national origin.

3. [1 During the first semester of 1965-66, “pioneer teach-

ers” of both races will be selected and given special

preparation and, during the second semester of

school year 1965-66, assigned to exchange -class-

rooms and schools periodically.

4. [1 Institutions, agencies, organizations and individuals

that refer teachers and staff to school systems in

this State will, during school year 1965-66 be in-

formed of this school system’s policy of nondis-

crimination in filling positions for serving pupils

in this school system and they will be asked to so

inform persons seeking referrals.

es

oo

46a

In the future, there will be no requirement or re-

quest for the photograph of or racial identification

of applicants for employment, reemployment or

reassignment.

All teaching vacancies will be prominently posted

in all schools and applicants will be considered with-

out regard to race, color or national origin.

No new teacher will hereafter be employed who is

not willing to work on a completely desegregated

basis.

. [1 Other steps as follows:

47a

First Memorandum of the District Court

(Filed May 17, 1966)

The infant plaintiffs, as pupils or prospective pupils in

the public schools of New Kent County, and their parents

or guardians have brought this class action asking that the

defendants be required to adopt and implement a plan

which will provide for the prompt and efficient racial

desegregation of the county schools, and that the defen-

dants be enjoined from building schools or additions and

from purchasing school sites pending the court’s approval

of a plan. The plaintiffs also seek attorney’s fees and costs.

The defendants have moved to dismiss on the ground that

the complaint fails to state a claim upon which relief can

be granted. They have also answered denying the material

allegations of the bill.

The facts are uncontested.

New Kent is a rural county located east of the City of

Richmond. Its school system serves approximately 1,300

pupils, of which 740 are Negro and 550 are White. The

school board operates one white combined elementary and

high school, and one Negro combined elementary and high

school. There are no attendance zones. Each school serves

the entire county. Indian students attend a school in

Charles City County.

On August 2, 1965 the county school board adopted a

freedom of choice plan to comply with Title VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U. S. C. §2000.d-1, ef seq. The

choices include the Indian school in Charles City County.

The county had operated under the Pupil Placement Act,

§822.232.1, et seq., Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended.

As of September 1964 no Negro pupil had applied for

48a

admission to the white school. No Negro faculty member

serves in the white school and no white faculty member

serves in the Negro school.

New construction is scheduled at both county schools.

The case is controlled by the principles expressed in

Wright v. School Bd. of Greenville County, Va., No. 4263

(E. D. Va,, Jan. 27, 1966). An order similar to that en-

tered in Greenville will deny an injunction restraining con-

struction and grant leave to submit an amendment to the

plan for employment and assignment of staff on a non-

racial basis. The motion for counsel fees will be denied.

/s/ JorN D. BuTzNER, Jr.

United States District Judge

49a,

First Order of the District Court

(Filed May 17, 1966)

For reasons stated in the Memorandum of the Court this

day filed in the Memorandum of the Court in Wright

v. County School Board of Greenville County, Virgima,

Civil Action No. 4263 (E. D. Va., Jan. 27, 1966),

It 1s ADJUDGED and ORDERED:

1. The defendants’ motion to dismiss is denied;

2. The plaintiffs’ prayer for an injunction restraining

school construction and the purchase of school sites is

denied;

3. The defendants are granted leave to submit on or be-

fore June 6, 1966 amendments to their plan which will pro-

vide for employment and assignment of the staff on a non-

racial basis. Pending receipt of these amendments, the

court will refer approval of the plan and consideration of

other injunctive relief;

4. The plaintiffs’ motion for counsel fees is denied;

5. The case will be retained upon the docket with leave

granted to any party to petition for further relief.

The plaintiffs shall recover their costs to date.

Let the Clerk send copies of this order and the Memo-

randum of the Court to counsel of record.

/s/ JoHN D. BUTzNER, JR.

United States District Judge

50a

Defendants’ Plan Supplement

(Filed June 6, 1966)

The School Board of New Kent County recognizes its

responsibility to employ, assign, promote and discharge

teachers and other professional personnel of the school

systems without regard to race, color or national origin.

We further recognize our obligation to take all reasonable

steps to eliminate existing racial segregation of faculty

that has resulted from the past operation of a dual system

based upon race or color.

The New Kent Board recognizes the fact that New Kent

County has a problem which differs from most counties in

that the white citizens are the minority group. The Board

is also cognizant of the fact that race relations are gen-

erally good in this county, and Negro citizens share in

county government. A Negro citizen is a member of the

County Board of Supervisors at the present time.

In the recruitment, selection and assignment of staff, the

chief obligation is to provide the best possible education

for all children. The pattern of assignment of teachers and

other staff members among the various schools of this sys-

tem will not be such that only white teachers are sought

for predominantly white schools and only Negro teachers

are sought for predominantly Negro schools.

The following procedures will be followed to carry out

the above stated policy:

1. The best person will be sought for each position with-

out regard to race, and the Board will follow the policy

of assigning new personnel in a manner that will work

toward the desegregation of faculties. We will not

select a person of less ability just to accomplish de-

segregation.

(S

|

~3

5la

Institutions, agencies, organization, and individuals

that refer teacher applicants to the school system will

be informed of the above stated policy for faculty de-

segregation and will be asked to so inform persons

seeking referrals.

The School Board will take affirmative steps to allow

teachers presently employed to accept transfers to

schools in which the majority of the faculty members

are of a race different from that of the teacher to be

transferred.

No new teacher will be hereafter employed who is not

willing to accept assignment to a desegregated faculty

or in a desegregated school.

All Workshops and in-service training programs are

now and will continue to be conducted on a completely

desegregated basis.

All members of the supervisory staff will be assigned

to cover schools, grades, teachers and pupils without

regard to race, color or national origin.

All staff meetings and committee meetings that are

called to plan, choose materials, and to improve the

total educational process of the division are now and

will continue to be conducted on a completely desegre-

gated basis.

All custodial help, cafeteria workers, maintenance

workers, bus mechanics and the like will continue to

be employed without regard to race, color or national

origin.

Arrangements will be made for teachers of one race to

visit and observe a classroom consisting of a teacher

and pupils of another race to promote acquaintance

and understanding.

52a

Plaintiffs’ Exception to Plan Supplement

(Filed June 10, 1966)

The plaintiffs take exception to the defendants’ Plan

Supplement adopted May 23, 1966 and filed herein pur-

suant to leave granted in this Court’s order of May 17,

1966 to submit amendments which will provide for employ-

ment and assignment of the staff on a non-racial basis.

I

The Supplement does not contain well-defined procedures

which will be put into effect on definite dates. The Supple-

ment does not even provide the “token assignments” which

this Court warned would not suffice.

41

In all reality, the Supplement states the defendant school

board’s refusal to take any initiative to desegregate the

faculties of the several schools.

WHEREFORE, the plaintiffs pray that their exceptions be

sustained and that the defendants be required to forthwith

eliminate all facets of racial segregation and discrimination

with respect to administrative personnel, teachers, clerical,

custodial and other employees, transportation and other

facilities, and the assignment of pupils to schools and class-

rooms in the public schools of New Kent County and that

the defendants be required to establish geographic attend-

ance areas for each public school in said county and assign

each child to the school so designated to serve his area of

residence.

/8/ S. W. Tucker

Of Counsel for Plaintiffs

53a

Memorandum of the Court

(Filed June 28, 1966)

This memorandum supplements the memorandum of the

court filed May 17, 1966. The court deferred ruling on the

school board’s plan of desegregation until after the board

had an opportunity to amend the plan to provide for

allocation of faculty and staff on a non-racial basis. The

board has filed a supplement to the plan to accomplish

this purpose.

The plan and supplement are:

1.

Ax~NuaL F'reepom or CHOICE oF SCHOOLS

A. The County School Board of New Kent County has

adopted a policy of complete freedom of choice to be offered

in grades 1, 2, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12 of all schools without

regard to race, color, or national origin, for 1965-66 and all

grades after 1965-66.

B. The choice is granted to parents, guardians and per-

sons acting as parents (hereafter called ‘parents’) and their

children. Teachers, principals and other school personnel

are not permitted to advise, recommend or otherwise in-

fluence choices. They are not permitted to favor or penalize

children because of choices.

1.

PuriLs EnTERING OTHER GRADES

Registration for the first grade will take place, after con-

spicuous advertising two weeks in advance of registration,

between April 1 and May 31 from 9:00 A.M. to 2:00 P.M.

When registering, the parent will complete a Choice of

54a

Memorandum of the Court

School Form for the child. The child may be registered at

any elementary school in this system, and the choice made

may be for that school or for any other elementary school

in the system. The provisions of Section VI of this plan

with respect to overcrowding shall apply in the assignment

to schools of children entering first grade.

111.

PupriLs ENTERING OTHER GRADES

A. Each parent will be sent a letter annually explaining

the provisions of the plan, together with a Choice of School

Form and a self-addressed return envelope, by April 1 of

each year for pre-school children and May 15 for others.

Choice forms and copies of the letter to parents will also

be readily available to parents or students and the general

public in the school offices during regular business hours.

Section VI applies.

B. The Choice of School Form must be either mailed

or brought to any school or to the Superintendent’s Office

by May 31st of each year. Pupils entering grade one (1)

of the elementary school or grade eight (8) of the high

school must express a choice as a condition for enrollment.

Any pupil in grades other than grades 1 and 8 for whom

a choice of school is not obtained will be assigned to the

school he is now attending.

y.

PuriLs NewLy ENTERING ScHOOL SYSTEM OR

CuaNciNng ResipENce WitHIN IT

A. Parents of children moving into the area served by

this school system, or changing their residence within it,

55a

Memorandum of the Court

after the registration period is completed ‘but before the

opening of the school year, will have the same opportunity

to choose their children’s school just before school opens

during the week of August 30th, by completing a Choice

of School Form. The child may be registered at any school

in the system containing the grade he will enter, and the

choice made may be for that school or for any other such

school in the system. However, first preference in choice of

schools will be given to those whose Choice of School Form

is returned by the final date for making choice in the regular

registration period. Otherwise, Section VI applies.

B. Children moving into the area served by this school

system, or changing their residence within it, after the late

registration period referred to above but before the next

regular registration period, shall be provided with regis-

tration forms. This has been done in the past.

V.

RESIDENT AND NON-RESIDENT ATTENDANCE

This system will not accept non-resident students, nor

will it make arrangements for resident students to attend

public schools in other school systems where either action

would tend to preserve segregation or minimize desegre-

gation. Any arrangement made for non-resident students

to attend public schools in this system, or for resident stu-

dents to attend public schools in another system, will assure

that such students will be assigned without regard to race,

color, or national origin, and such arrangement will be ex-

plained fully in an attachment made a part of this plan.

Agreement attached for Indian children.

dba

Memorandum of the Court

VI.

OVERCROWDING

A. No choice will be denied for any reason other than

overcrowding. Where a school would become overcrowded

if all choices for that school were granted, pupils choosing

that school will be assigned so that they may attend the

school of their choice nearest to their homes. No preference

will be given for prior attendance at the school.

B. The Board plans to relieve overcrowding by building

during 1965-66 for the 1966-67 session.

VII.

TRANSPORTATION

Transportation will be provided on an equal basis with-

out segregation or other discrimination because of race,

color, or national origin. The right to attend any school in

the system will not be restricted by transportation policies

or practices. To the maximum extent feasible, busses will