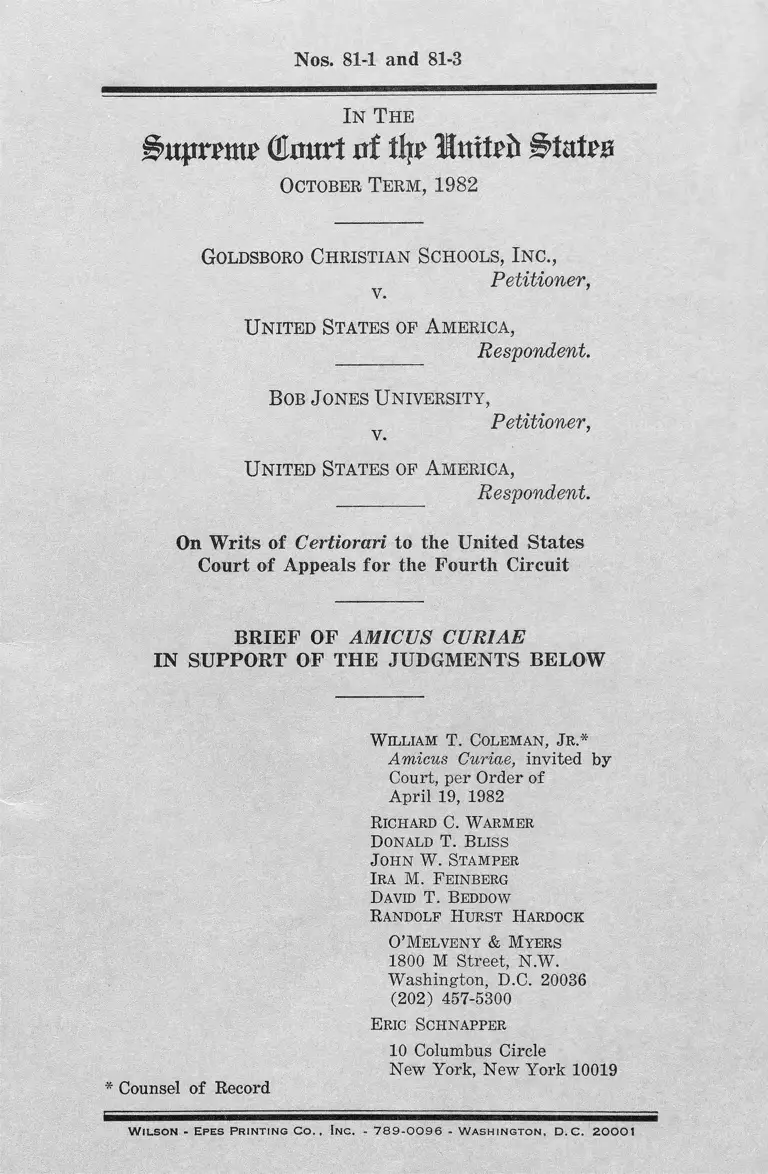

Goldsboro Christian Schools, Inc. v. United States Brief of Amicus Curiae in Support of the Judgements Below

Public Court Documents

August 25, 1982

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Goldsboro Christian Schools, Inc. v. United States Brief of Amicus Curiae in Support of the Judgements Below, 1982. 41cd538f-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/50c82b27-5bbe-4148-9b16-99944252ca79/goldsboro-christian-schools-inc-v-united-states-brief-of-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-the-judgements-below. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

Nos. 81-1 and 81-3

I n T h e

( ta r t uf % Imtrfc ^tatris

October Term, 1982

Goldsboro Ch r istia n Schools, I n c .,

Petitioner,v.

U n it ed States of A m erica ,

Respondent.

B ob J o nes U n iv ersity ,

Petitioner, v. ’

U n it ed States of A m erica ,

Respondent.

On Writs of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF THE JUDGMENTS BELOW

William T. Coleman, J r.*

Amicus Curiae, invited by

Court, per Order of

April 19, 1982

Richard C. Warmer

Donald T. Bliss

J ohn W. Stamper

Ira M. F einberg

David T. Beddow

Randolf Hurst Hardock

O’Melveny & Myers

1800 M Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 457-5300

Eric Schnapper

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

* Counsel of Record

W ilson - Epes P r i n t i n g C o . , In c . - 7 8 9 -0 0 9 6 - W a s h i n g t o n . D.C. 20001

AMICUS CURIAE9S COUNTERSTATEMENT

OF THE QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Do Sections 501(c)(3) and 170 of the Internal

Revenue Code authorize recognition of tax benefits for

private schools that discriminate on the basis of race in

the admission of students and adhere to other racially

discriminatory policies and practices?

2. Does the recognition of tax-exempt status and

eligibility to receive tax-deductible contributions for ra

cially discriminatory private schools violate the Govern

ment’s constitutional obligation to steer clear of giving

significant aid to schools that practice racial discrimina

tion?

3. Does the First Amendment require that private

schools which practice racial discrimination because of

religious beliefs be afforded tax benefits under Sections

501(c) (3) and 170 of the Code even though such benefits

are properly withheld from schools that claim no religious

basis for their racially discriminatory policies?

(i)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

AMICUS CURIAE’S COUNTERSTATEMENT OF

THE QUESTIONS PRESENTED ___________ i

TABLE OF CONTENTS .................... ....................... . iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.................. v

P R E L IM IN A R Y STATEMENT OF AMICUS

CURIAE _______ 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.......................... 6

ARGUMENT_________________ 11

I. THE IRS RULING DENYING TAX-EXEMPT

STATUS TO RACIALLY DISCRIMINATORY

PRIVATE SCHOOLS WAS A NECESSARY

RESULT OF FUNDAMENTAL DEVELOP

MENTS IN STATUTORY AND CONSTITU

TIONAL LAW _____ ___________________ ___ _ 11

II. CONGRESS INTENDED TO GRANT TAX

BENEFITS UNDER §§501 (e)(3 ) AND 170

TO CHARITABLE ORGANIZATIONS IN THE

COMMON LAW SENSE AND THUS NOT

TO ORGANIZATIONS WHOSE ACTIVITIES

ARE UNLAWFUL OR VIOLATE FUNDA

MENTAL NATIONAL POLICIES __________ 17

A. The Language of §§ 501(c) (3) and 170 Re

flects Their Origins in the Common Law and

in English and State Tax Exemption Stat

utes _________ ________ ___ ____ _________ 18

B. The Legislative History of §§ 501 (c) (3) and

170 Demonstrates That Congress Intended

to Enact an Exemption Only for Organiza

tions Charitable at Law .......... ...................... . 24

(iii)

IV

C. Consistent Judicial and Administrative Con

struction of §§ 501(c) (3) and 170 Makes

Clear That They Were Intended to Provide

Tax Benefits Only to Organizations Chari

table at L aw ____________________ ______ 28

D. The Language of the Code Supports the Con

clusion That Congress Intended That Exempt

TABLE OF CONTENTS—Continued

Page

Organizations Must Satisfy the Standards

of the Law of Charity__________________ 35

E. Petitioners Do Not Qualify for Favored

Tax Treatment as Charitable Organizations.. 40

III. RECOGNITION OF TAX EXEMPTION FOR

RACIALLY DISCRIMINATORY PRIVATE

SCHOOLS WOULD DISREGARD THE JUDI

CIAL PRESUMPTION AGAINST ALLOWING

TAX BENEFITS THAT SEVERELY FRUS

TRATE SHARPLY DEFINED FEDERAL

POLICY .......... ...................... ................................... 44

IV. SINCE 1970 CONGRESS HAS EXPLICITLY

RATIFIED AND APPROVED THE IRS AC

TIONS CHALLENGED BY PETITIONERS.... 48

V. THE FIFTH AMENDMENT BARS GRANT

ING THE TAX BENEFITS OF §§ 501 (c) (3)

AND 170 TO SCHOOLS THAT DISCRIMI

NATE ON THE BASIS OF RACE ............ ....... 57

VI. THE FIRST AMENDMENT DOES NOT RE

QUIRE THAT RACIALLY DISCRIMINA

TORY RELIGIOUS SCHOOLS BE AFFORDED

THE TAX BENEFITS OF §§ 501 (c) (3) AND

170 ________________ ______________ _______ 63

CONCLUSION ___ ________ _______________________ 69

APPENDIX A _______ ______________________ ____ _ la

APPENDIX B ............................. ............ ........... ............ . lb

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES: Page

Alessi v. Raybestos-Manhattan, Inc., 451 U.S. 504

(1981) .................................... .................. ---- --------- 52

Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freema

sonry v. Board of County Commissioners, 122

Neb. 586, 241 N.W. 93 (1932) ____ ___________ 23

Board of Education v. Allen, 392 U.S. 236 (1968).. 60

Board of Governors v. First Lincolnwood Corp.,

439 U.S, 234 (1978) ____ ________ _________ 55

Bob Jones University v. Johnson, 396 F. Supp.

597 (D.S.C. 1974), aff’d, 529 F.2d 514 (4th Cir.

1975)______________ ___ ________ __________ 41, 66

Bob Jones University v. Simon, 416 U.S. 725

(1974) ____________________-........................ ......passim

Bob Jones University v. United States, 468 F. Supp.

890 (D.S.C. 1978) ....... ................................. ...2, 3,15, 42

Bob Jones University v. United States, 639 F.2d

147 (4th Cir. 1980).............................. ...........— passim

Bok v. McCaughn, 42 F.2d 616 (3d Cir. 1930) .... 29, 31

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954)___ ____ 11

Bowles v. Weiner, 6 F.R.D. 540 (E.D. Mich. 1947).. 37

Braunfeldv. Brown, 366 U.S. 599 (1961)______ 63-64

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954) ..... ............... ........... ............... - ........... ..........passim

Brown v. Dade Christian Schools, Inc., 556 F.2d

310 (5th Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1063

(1978)________ ____________ ____________ 40, 66, 68

Brown v. Hartlage, 102 S. Ct. 1523 (1982) _____ 5

Bruton v. United States, 391 U.S. 123 (1968)___ 5

CBS, Inc. v. FCC, 453 U.S. 367 (1981)________ 55

C.F. Mueller Co. v. Commissioner, 190 F.2d 120

(3d Cir. 1951) ___ ___________ ______________ 29

Cammarano v. United States, 358 U.S. 498 (1959).. 31

Chapman v. Commissioner, 618 F.2d 856 (1st Cir.

1980), cert, dismissed, 451 U.S. 1012 (1981)..... 56

Cheng Fan Kwok v. INS, 392 U.S. 206 (1968) ..... 5

Christian Manner International, Inc. v. Commis

sioner, 71 T.C. 661 (1979)................................... 43

The Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883) ______ 47

Coit v. Green, 404 U.S. 997 (1971) ......... ......... ......passim

vi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

Commissioner v. Bilder, 369 U.S. 499 (1962)....... 52

Commissioner v. Portland Cement Co., 450 U.S.

156 (1981) ........................... .............................. .. 33

Commissioner v. Tellier, 383 U.S. 687 (1966) __ 44

Commissioners v. Pemsel, [1891] A.C. 531 ............ 20-22

Committee for Public Education v. Nyquist, 413

U.S, 756 (1973) ............... ................... ............... 59-61, 68

Congregational Church v. Attorney General, 376

Mass. 545, 381 N.E.2d 1305 (1978)___ _____ 24

Consumer Product Safety Commission v. GTE Syl-

vania, Inc., 447 U.S. 102 (1980) ...................... . 52

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958)......................... 6,11

Costanzo v. Tillinghast, 287 U.S. 341 (1932) ___ 39

Crellin v. Commissioner, 46 B.T.A. 1152 (1942)..... 31

De Sylva v. Ballentine, 351 U.S. 570 (1956)____ 36

Duffy v. Birmingham, 190 F.2d 738 (8th Cir.

1951) ......................................................................... 29-30

Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974) ________ 56

Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1 (1947).. 60

FBI v. Abramson, 102 S. Ct. 2054 (1982) .............. 36

FCC v. Pacifica Foundation, 438 U.S. 726 (1978).. 36

Fales, Herbert E., 9 B.T.A. 828 (1927)___ _____ 39-40

Faraca v. Clements, 506 F.2d 956 (5th Cir.) cert.

denied, 422 U.S. 1006 (1975) _____ ____ ______ 41

Fiedler v. Marumsco Christian School, 631 F.2d

1144 (4th Cir. 1980) ______________________ 40,41

Fifth-Third Union Trust Co. v. Commissioner, 56

F.2d 767 (6th Cir. 1932) ______ 31

Gilbert v. United States, 370 U.S, 650 (1962) ........ 24

Gillette v. United States, 401 U.S. 437 (1971) .....64, 67, 68

Gilmore v. City of Montgomery, 417 U.S. 556

(1974)......... .'_______ ___ ____ __________ .......57, 58, 62

Girard Trust Co. v. Commissioner, 122 F.2d 108

(3d Cir. 1941) ______ 30

Goldsboro Christian Schools, Inc. v. United States,

436 F. Supp. 1314 (E.D.N.C. 1977)_____ ____ 2, 67

Goldsboro Christian Schools, Inc. v. United States,

No. 80-1473 (4th Cir. Feb. 24, 1981) 3

V ll

Granville-Smith v. Granville-Smith, 349 U.S, 1

(1955) ..................................... ........... ........................ 5

Green v. Connally, 330 F. Supp. 1150 (D.D.C.)

aff’d per curiam sub nom. Coit v. Green, 404

U.S. 997 (1971) ....................... ................... .....passim

Green v. Kennedy, 309 F. Supp. 1127 (D.D.C.),

appeal dismissed sub nom. Cannon v. Green, 398

U.S. 956 (1970) .......... ............. . .... ............ ......passim

Griffin v. Breckenridge, 403 U.S. 88 (1971) ............ 13

Griffin v. County School Board, 377 U.S. 218

(1964) .............................................. ........... ..........13, 60, 66

GTE Sylvania, Inc. v. Consumers Union, 445 U.S.

375 (1980) _____ ____ ______ ____ _________ 5

Haig v. Agee, 453 U.S. 280 (1981) _____ ______ 9, 50, 55

Hamling v. United States, 418 U.S. 87 (1974).... 36

Harris v. Commissioner, 340 U.S. 106 (1950)___ 17

Harris v. McRae, 448 U.S. 297 (1980)..................... 67

Harrison v. Barker Annuity Fund, 90 F.2d 286

(7th Cir. 1937)___ ___ ______ _________ _______ 30

Hazen v. National Rifle Association, 101 F.2d 432

(D.C. Cir. 1938) ___________ ____ ___________ 30

Heffron v. International Society for Krishna Con

sciousness, 452 U.S. 640 (1981)______________ 66

Helvering v. Bliss, 293 U.S. 144 (1934) ________ 28-29

Helvering v. Winmill, 305 U.S. 79 (1938)__ __ _ 55

Hicks v. Miranda, 422 U.S. 332 (1975) ................ 56

Hodges v. United States, 203 U.S. 1 (1906)____ 13,43

Holt v. Commissioner, 69 T.C. 75 (1977), aff’d,

611 F.2d 1160 (5th Cir. 1980)_______ __ ____ 45

Hoover Motor Express Co. v. United States, 356

U.S, 38 (1958)_______ _________ _________ 44,45

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969) ......... ...... 47

Hutterische Bruder Gemeinde, 1 B.T.A. 1208

(1925) ........................... ............. .......... .............. . 30

Illinois Brick Co. v. Illinois, 431 U.S. 720 (1977).... 56

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

via

International Reform Federation v. District Unem

ployment Compensation Board, 131 F.2d 337

(D.C. Cir. 1942) ____________ ___ ___________ 20

Jackson v. Phillips, 96 Mass. (14 Allen) 539

(1867)------------ ---------------------- ------------ ---- 20, 27, 28

James Sprunt Benevolent Trust v. Commissioner,

20 B.T.A. 19 (1930) .............................................. . 31

Jarecki v. G.D. Searle & Co., 367 U.S. 303 (1961).. 8, 37

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, 421 U.S.

454 (1975) ________________ _______________ 12

Johnson v. Robison, 415 U.S. 361 (1974)..... .........._ 65

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409

(1968) --------------------------- --- ---------- ----------- 12,13

Kentucky v. Indiana, 281 U.S. 163 (1930) .............. 5

Keystone Automobile Club v. Commissioner, 181

F.2d 402 (3d Cir. 1950)______ __________ ___ _ 38

Knowlton v. Moore, 178 U.S. 41 (1900)___ __ ___ 36

Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602 (1971).... .......... 60

Lorillard v. Pons, 434 U.S. 575 (1978)_________ 34

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967)..... ............... 41

Lynch v. Overholser, 369 U.S. 705 (1962)............... 39

M.E. Church, South v. Hinton, 92 Tenn, 188, 21

S.W. 321 (1893) ___________ ________________ 23

McDonald v. Hovey, 110 U.S. 619 (1884)_______ 24

McCulloch v. Maryland, 4 Wheat. 316 (1819) ___ 36

McGlotten v. Connally, 338 F.Supp. 448 (D.D.C.

1972) -------------------------- ---- ------ ------------------- 50,57

McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U.S. 420 (1961)......... 67, 68

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637

(1950)____________________ ____________ _ 41

Maguire v. Commissioner, 313 U.S. 1 (1941) ....... 35-36

Massachusetts League v. United States, 59 F. Supp.

346 (D. Mass. 1945)_______________________ 40

Mazzei v. Commissioner, 61 T.C. 497 (1974) ....... 45,46

Mississippi University for Women v. Hogan, 102

S. Ct. 3331 (1982) ________ ____________ ____ 47

Molly Varnum Chapter, D.A.R. v. City of Lowell,

204 Mass. 487, 90 N.E. 893 (1910)_________ _ 23

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

ix

Monell v. Department of Social Services, 436 U.S.

658 (1978) _______ _________ _______ _______ 55

Morgan v. Nauts, 6 AFTR 8011 (N.D. Ohio 1928).. 31

NLRB v. Amax Coal Co., 453 U.S. 322 (1981)...... 24

NLRB v. Catholic Bishop of Chicago, 440 U.S.

490 (1979) _____________ _____________ _____ 57

NLRB v. Gullett Gin Co., 340 U.S. 361 (1951) ...... 34

National Lead Co. v. United States, 252 U.S. 140

(1920) _________________ __ ___________ ____ 34

National Muffler Dealers Association v. United

States, 440 U.S. 472 (1979)................. ........... ...8 , 33, 38

Neal v. Clark, 95 U.S. 704 (1878) ......................... 37

North Haven Board of Education v. Bell, 102 S. Ct.

1912 (1982) ______________________ _________ 5

Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 (1973) _____ passim

Ould v. Washington Hospital for Foundlings, 95

U.S. 303 (1877) __ _____________ __________.7,28,29

Patsy v. Board of Regents, 102 S. Ct. 2557 (1982).. 56

Pennock v. Dialogue, 2 Pet. 1 (1829) ______ ____ 24

Pennsylvania Co. v. Helvering, 66 F.2d 284 (D.C.

Cir. 1933)_______ ________ __ _________ __ ___ 29

People ex rel. Doctors Hospital, Inc. v. Sexton, 267

App. Div. 736, 48 N.Y.S.2d 201 (1944) ......... 23

Perin v. Carey, 24 How. 465 (1861)___________ 7, 28, 37

Personnel Administrator v. Feeney, 442 U.S. 256

(1979) _____ __________ ______________ __ _ 58

Peters v. Commissioner, 21 T.C. 55 (1953) ...... . 29

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510 (1925).. 67

Pierson v. Ray, 386 U.S. 547 (1967) ________ __ 24

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896)__ ______ 43

Plyler v. Doe, 102 S. Ct, 2382 (1982)__________ 11

Poindexter v. Louisiana Financial Assistance Com

mission, 275 F. Supp. 833 (E.D. La. 1967), aff’d,

389 U.S. 571 (1968)______ _________ __ _____ 13, 66

Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Co., 158 U.S. 601

(1895) .............. ...................... ........... ............. ......... 18

Prince Edward School Foundation v. United

States, 450 U.S. 944 (1981) ___ __________ _ 35

Prince v. Massachusetts, 321 U.S. 158 (1944) ....... 64, 67

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

X

Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. FCC, 395 U.S. 367

(1969) ...................................... ............................... . 9, 55

Reed v. Reed, 404 U.S. 71 (1971)________ ______ 47

Reiter v. Sonotone Corp., 442 U.S. 330 (1979) 35

Reynolds v. United States, 98 U.S. 145 (1878)___ 64

Richmond Television Corp. v. United States, 382

U.S. 68 (1965)......... ......... ....................................... 5

Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973) ___ _____ 4

Rogers v. Herman Lodge, 102 S. Ct. 3272 (1982).. 58

Rose v. Lundy, 102 S. Ct. 1198 (1982) .................. 39

Rosengart v. Laird, 405 U.S. 908 (1972) .............. 5

Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976) ...........passim

St. Louis Union Trust Co. v. Burnet, 59 F.2d 922

(8th Cir. 1932) ........................... ............... ........... „ 29

St. Louis Union Trust Co. v. United States, 374

F.2d 427 (8th Cir. 1967)...................... ......... ....... 30

Samuel Friedland Foundation v. United States,

144 F. Supp. 74 (D.N.J. 1956) ........... ........... . 30

Schlesinger v. Ballard, 419 U.S. 498 (1975)_____ 47

Scripture Press Foundation v. United States, 285

F.2d 800 (Ct. Cl. 1961), cert, denied, 368 U.S.

985 (1962) ...... ....................................... .................. 43

Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398 (1963)_____ __ 65

Sibley v. Commissioner, 16 B.T.A. 915 (1929)...... 29

Slee v. Commissioner, 15 B.T.A. 710 (1929), aff’d,

42 F.2d 184 (2d Cir. 1930)__________________ 31, 39

Slee v. Commissioner, 42 F.2d 184 (2d Cir. 1930).. 30

Stafford v. Briggs, 444 U.S. 527 (1980) .............. . 38

Stockton Civic Theatre v. Board of Supervisors,

66 Cal.2d 13, 423 P.2d 810, 56 Cal. Rptr. 658

(1967) .............................. .................. ............. - ....... 23

Storti v. Commonwealth, 178 Mass. 549, 60 N.E.

210 (1901) ______ ____________ __ ___________ 37

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U.S.

229 (1969) ______________ ______ __ _____ 12

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Educa

tion, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) __________ - .............. - 13

Swearingen v. United States, 161 U.S. 446 (1896).. 36

Tank Truck Rentals, Inc. v. Commissioner, 356

U.S. 30 (1958).........................................................passim

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

Textile Mills Securities Corp. v. Commissioner, 314

U.S. 326 (1941) ..................................... .............. . 44

Thomas v. Review Board, 450 U.S, 707 (1981)___ 65

Tillman v. Wheaton-Raven Recreation Associa

tion, 410 U.S. 431 (1973)__________________ 12

Tilton v. Richardson, 403 U.S. 672 (1971)_____ _ 68

Travelers’ Insurance Co. v. Kent, 151 Ind. 349,

50 N.E. 562 (1898) _______________ _____ _ 23

Trinidad v. Sagrada Orden, 263 U.S. 578 (1924).. 28, 43

Turnipseed v. Commissioner, 27 T.C. 758 (1957).. 45

Turnure v. Commissioner, 9 B.T.A. 871 (1927).... 29

Underwriters’ Laboratories, Inc. v. Commissioner,

135 F.2d 371 (7th Cir. 1943)____ ____________ 30

Union Insurance Co. v. United States, 6 Wall. 759

(1867) _________________ __________________ 36

United States v. Byrum, 408 U.S. 125 (1972)____ 56

United States v. Clark, 445 U.S. 23 (1980)______ 57

United States v. Correll, 389 U.S. 299 (1967) ___ 33, 55

United States v. Euge, 444 U.S. 707 (1980)_____ 24

United States v. Fisk, 3 Wall. 445 (1865)_______ 36

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Educa

tion, 372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966) ___________ 13

United States v. Lee, 102 S. Ct. 1051 (1982)___63, 64, 67

United States v. Leslie Salt Co., 350 U.S. 383

(1956)____________________________________ 38

United States v. Lovett, 328 U.S. 303 (1946)____ 5

United States v. Moore, 613 F.2d 1029 (D.C. Cir.

(1979), cert, denied, 446 U.S. 954 (1980) ......... 37

United States v. Morris, 125 F. 322 (E.D. Ark.

1903)__________________________________ __ _ 13

United States v. Price, 383 U.S. 787 (1966) .......... 13

United States v. Proprietors of Social Law Library,

102 F.2d 481 (1st Cir. 1939) ................................ 30

United States v. Rutherford, 442 U.S. 544 (1979).. 50

United States v. Ryan, 284 U.S. 167 (1931) .......... 34

United States v. Scrimgeour, 636 F.2d 1019 (5th

Cir.), cert, denied, 102 S. Ct. 359 (1981) ............ 37

United States v. Stewart, 311 U.S. .60 (1940).... . 17

United States v. W.T. Grant Co., 345 U.S. 629

(1953) ........... ....... .......... .................. ‘...................... 5

Walz v. Tax Commission, 397 U.S. 664 (1970)...... . 29, 59

x i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

xii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976)--- ------ 58

Washington v. Seattle School District No. 1, 102

S. Ct. 3187 (1982) ..................... ................... .......... H , 58

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works, 427 F.2d 476

(7th Cir.), cert, denied, 400 U.S. 911 (1970)----- 12

Weber v. United States, 119 F.2d 932 (9th Cir.

1941), aff’d per curiam by an equally divided

Court, 315 U.S. 787 (1942)____________ _____ 5

Winters v. Commissioner, 468 F.2d 778 (2d Cir.

1972) ---- --------------------- ---------------------------- 64

Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205 (1972)_______ 65, 68

Wright v. Regan, 656 F.2d 820 (D.C. Cir. 1981),

petitions for cert, filed, 50 U.S.L.W. 3353 (Oct.

20, 1981) (No. 81-757), 3467 (Nov. 23, 1981)

(No. 81-970) _______ ___ __________________ 62

Wright v. Regan, No. 80-1124, Order (February

18, 1982) ...............- ................................... - ......... 4

Young v. United States, 315 U.S. 257 (1942)----- 5

CONSTITUTION AND FEDERAL STATUTES:

United States Constitution:

First Amendment......... ....... passim

(Establishment Clause)--------------10, 63, 67-69

(Free Exercise Clause)------------------------ 63-67

Fifth Amendment----------------- ------------ ........passim

Thirteenth Amendment ----------------- ----- - —6,12, 47

Fourteenth Amendment----------------------------- 6,11

Act of July 1, 1862, ch. 119, 12 Stat. 432 ________ 19

Act of June 30, 1864, ch. 173, 13 Stat. 223 _____ 19

Act of June 27, 1902, ch. 1160, 32 Stat. 406____ 25

Act of October 20, 1976, Pub. L. No. 94-568, 90

Stat. 2697.... .............. ............... .................- ............. 49, 50

Civil Rights Act of 1866:

42 U.S.C. § 1981________________________ passim

42 U.S.C. § 1982 _______________________ - 12

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000a et

seq. ..... .............. — .........------------------------- 12

Title IY, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000c ___________ 12

Title VI, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000d ......... ................... . 12, 41

Civil Rights Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C. §§ 3601 et seq... 12

xm

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

Education Act Amendments of 1972, Title IX, 20

U.S.C. § 1681(a) ( 5 ) ............................... -.............. - 47

Internal Revenue Code (I.R.C.) of 1954 (26 U.S.C.

(1976)) :

. 45,46

.'passim

.passim

50

18

36

8, 50-52

- 18,36

18

18

18

18

36

18

18

18

18

18

17

17

36

18

. 47,49

Pub. L. No. 91-618, § 1, 84 Stat. 1855 (1970)............. 49

Pub. L. No. 92-418, § 1 (a ) , 86 Stat. 656 (1972).... 49

Pub. L. No. 93-310, § 3 (a ), 88 Stat. 235 (1974).... 49

Pub. L. No. 93-625, § 10 (c ) , 88 Stat. 2108, 2119

(1975) ...... .............. .................. ............ .......... ......... 49

Pub. L. No. 95-227, § 4 (a ) , 92 Stat. 11, 15 (1978).. 49

Pub. L. No. 95-345, § 1(a), 92 Stat. 481 (1978).... 49

Pub. L. No. 95-600, § 703(b) (2), 92 Stat. 2763,

2939 (1978) ______ _________________ ______ _ 49

Pub. L. No. 96-222, § 108(b) (2) (B), 94 Stat. 194,

226 (1980) _________________________ _______ 49

§ 162______ ________

§ 1 70____ ____

§501 (c )(3 ) ...............

§ 5 0 1 (c)(7) ......... - .....

§ 501(c) (10) ........... .

§ 501(h) ........... .......

§ 501 ( i ) ___________

§ 642(c) -----------------

§ 2055(a) (2) .......... .

§ 2055(a) (3) .............

§2106 (a) (2) (A) (ii)

§2106 (a) (2) (A) (hi)

§ 2522 ...........................

§ 2522(a )(2) ______

§2522 (a) (3) .......... .

§ 2522 (b )(2) ............

§ 2522(b) (3) .............

§ 2522(b )(4) ______

§ 3121(b) (8) (B) .... .

§ 3306(c) (8) ........ .

§4911 ...........................

§ 4911(e) (1) (A) .......

§ 7428 ......... .................

XIV

Pub. L. No. 96-364, §209 (a), 94 Stat. 1208,

1290 (1980) _______________ ____ ________ _ 49

Pub. L. No. 96-601, § 3 (a), 94 Stat. 3495, 3496

(1980) ____________ ___ ____ _________ ______ 49

Pub. L. No. 96-605, §106 (a), 94 Stat. 3521,

3523 (1980) _____________ __________ ___ ___ 49

Pub. L. No. 97-119, § 103 (c)(1 ), 95 Stat. 1635,

1638 (1981) ....... ............... ................... ........... - ..... 49

Revenue Act of 1918, ch. 18, 40 Stat. 1057 (1919).. 39

Revenue Act of 1921, ch. 136, 42 Stat. 227 (1921).. 31, 39

Revenue Act of 1934, ch. 277, 48 Stat. 680 --------- 40

Tariff Act of 1894, ch. 349, 28 Stat. 509 (1894).... 18, 20

Tariff Act of 1909, ch. 6, 36 Stat. 11 (1909) _____ 18

Tariff Act of 1913, ch. 16, 38 Stat. 114 (1913) ....... 18, 39

Tax Reform Act of 1969, Pub. L. No. 91-172, 83

Stat. 487 (1969) _________________ ___ ____ _ 7, 34

Tax Reform Act of 1976, Pub. L. No. 94-455, 90

Stat. 1520 (1976)_______ ____________________ 17,49

Treasury, Postal Service, and General Govern

ment Appropriations Act of 1980, Pub. L. No.

96-74, 93 Stat. 559 (1979) __ _____ __________ 52

Section 103, 93 Stat. at 562 (Ashbrook

Amendment) ...................... ............................ 9, 52

Section 615, 93 Stat. at 577 (Doman Amend

ment) ___ ___________ _________ ______ 9, 52

18 U.S.C. § 241 ............... ...................................... 13

28 U.S.C. § 2201 ___ _______ ________ _ 4

42 U.S.C. § 1985(3) ________ _________________ 13

Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1971 et

se q .___________ __________ ____ ____________ 12

War Revenue Act, ch. 63, 40 Stat. 300 (1917) ___ 18

War Revenue Act of 1898, ch. 448, 30 Stat. 448

(1898) _______________ ______ ______________ 25

STATE STATUTES:

Ind. Rev. Stat. ch. 98, § 8525 (1892)________ ___ 22

Mass. Pub. St. ch. 11, § 5 (1882).......... .......... ........ 22

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

XV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

FOREIGN STATUTES: Page

Income Tax Act of 1842, 5 & 6 Viet. c. 35, s. 61,

No. VI, Sehed. A ..... ................................. .............. 21

FEDERAL REGULATIONS:

Treas. Regs. Ser. 4, No. 4, Special Taxes § 27 (Jan.

1868) .......................... ....................... ..................... . 19

Treas. Reg. 45, Art. 517 (1921)_______________ 31, 40

Treas. Reg. § 1.501(e) (3 )-l(c ) (1) (1959) ............. 43

Treas. Reg. § 1.501(c) (3 )-l(d ) (1) (ii) (1959)..... 32

Treas. Reg. § 1.501(c) (3 )-l(d ) (2) (1959) ..... ..25, 32, 33

LEGISLATIVE MATERIALS:

H.R. 68, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1971) ........................ 49

H.R. 2352, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1971)......... 49

H.R. 5350, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1971) ...... 49

H.R. 1394, 93d Cong., 1st Sess. (1973)_____ 49

H.R. 3225, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. (1975) _________ 49

H.R. 96, 96th Cong., 1st Sess, (1979) ______ ____ 49

H.R. 1905, 96th Cong., 1st Sess. (1979) ___ __ _ 49

H.R. 95, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. (1981)________ _ 48

H.R. 332, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. (1981) __________ 48

H.R. 802, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. (1981) __________ 48

S. 995, 96th Cong., 1st Sess. (1979)_______ __ _ 49

Administration’s Change in Federal Policy Regard

ing the Tax Status of Racially Discriminatory

Private Schools: Hearing Before the House

Comm, on Ways and Means, 97th Cong., 2d

Sess. (1982) (“1982 Hearing”) _____________passim

Equal Educational Opportunity: Hearings Before

the Senate Select Comm, on Equal Educational

Opportunity, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. (1970)

(“1970 Hearings”) __ ____________ passim

Hearings on H.R. 82A5 Before the Senate Comm,

on Finance Committee, 67th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1921) ..................... ........ ...................... ................. . 40

Hearings on H.R. 12863 Before the Senate Comm.

on Finance, 65th Cong., 2d Sess. (1918)______ 26

Hearings on the Revenue Bill Before the House

Comm, on Ways and Means, 65th Cong., 2d Sess.

(1918) .......................................................... ........... . 26-27

Miscellaneous Tax Bills V: Hearings Before

the Subcomm. on Taxation and Debt Manage

ment of the Senate Comm, on Finance, 96th

Cong., 2d Sess. (1980)........ .............................. . 51

Tax Exempt Status of Private Schools: Hearings

Before the Subcomm. on Oversight of the House

Comm, on Ways and Means, 96th Cong., 1st

Sess. (1979)............................ ................................. 53,54

Tax Exempt Status of Private Schools: Hearings

Before the Subcomm. on Taxation and Debt

Management of the Senate Comm, on Finance,

96th Cong., 1st Sess. (1979) ............„___ _____ 53, 54

Tax Exemptions for Charitable Organizations A f

fecting Poverty Programs: Hearings Before the

Subcomm. on Employment, Manpower and Pov

erty of the Senate Comm, on Labor and Public

Welfare, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. (1970) _____ ___ 48

H.R. Rep. No. 276, 53d Cong., 2d Sess. (1894) ...... 20

H.R. Rep. No. 1702, 57th Cong., 1st Sess. (1902) ... 25, 39

H.R. Rep. No. 1681, 74th Cong., 1st Sess. (1935)... 26

H.R. Rep. No. 1860, 75th Cong., 3d Sess. (1938)... 27

H.R. Rep. No. 2333, 77th Cong., 2d Sess. (1942) .. 26

H.R. Rep. No. 2514, 82d Cong., 2d Sess. (1952).... 26

H.R. Rep. No. 413 (Part 1), 91st Cong., 1st Sess.

(1969) _________________ ___ ____ _________ 34

H.R. Rep. No. 658, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. (1975) .... 49

H.R. Rep, No. 1353, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. (1976) .. 50

House Comm, on Ways and Means, 89th Cong., 1st

Sess., Treasury Department Report on Private

Foundations (Comm. Print 1965)____________ 62

S. Rep. No. 52, 69th Cong., 1st Sess. (1926) ..... . 26

S. Rep. No. 665, 72d Cong., 1st Sess. (1932)____ 26

S. Rep. No. 1567, 75th Cong., 3d Sess. (1938) ...... 26

S. Rep. No. 1631, 77th Cong., 2d Sess. (1942) ...... 26

S. Rep. No. 1318, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. (1976) ..... 8, 50

S. Rep. No, 1033, 96th Cong., 2d Sess. (1980)___ 51

xvi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

Senate Select Comm, on Equal Educational Oppor

tunity, 92d Cong., 2d Sess., Toward Equal Edu

cational Opportunity (Comm. Print 1972).... . 48

26 Cong. Rec. 584-88, 1609-10, 1612-14, 3562, 3781,

6612-15, 6693, Appendix 418-19 (1894) ............. 20

35 Cong. Rec. 5565 (1902)........ 19,25

44 Cong. Rec. 4150 (1909)..................... 26

50 Cong. Rec. 1306 (1913)... 39

55 Cong. Rec. 6728-29 (1917)............ .......... 26

56 Cong. Rec. 10,418-28 (1918) .......... 26,27

61 Cong. Rec. 5294 (1921) ................ 27

79 Cong. Rec. 12,423-24 (1935) _..____ 26

116 Cong. Rec. 24,120-22, 24,427-33, 24,836, 24,906-

07 (1970) ______ _____ ________ _____________ 48

125 Cong. Rec. H5879 (daily ed. July 13, 1979) .... 53

H5882 (daily ed. July 13, 1979)..... 53

H5884 (daily ed. July 13, 1979)..... 54

H5980 (daily ed. July 16, 1979) .... 53

H5982 (daily ed. July 16, 1979).... 54

S l l ,979-80 (daily ed. Sept. 6,

1979) ...................... ............ .......... . 53,54

127 Cong. Rec. H5395 (daily ed. July 30, 1981)..... 53

REVENUE RULINGS AND PROCEDURES:

A.R.M. 104, 4 C.B. 262 (1921) ___ 31

A.R.R. 477, 4 C.B. 264 (1921)............. 31

Decision No. 110 (May 1863), reprinted in Bout-

well, A Manual of the Direct and Excise Tax

System of the United States 273 (1863)___ __ 19

G.C.M. 15778, XIV-2 C.B. 118 (1935) ___ __ _ 31

G.C.M. 19715, 1938-1 C.B. 499 ______________ _ 40

I.T. 1800, II-2 C.B. 152 (1923)________________ 32-33

O.D. 510, 2 C.B. 209 (1920) ..... ............ .................... 31

Rev. Proc. 72-54, 1972-2 C.B. 834 .............. 14

Rev. Proc. 75-50, 1975-2 C.B. 587 ..................... 14

Rev. Rul. 55-656, 1955-2 C.B. 262 _______ 25

Rev. Rul. 59-310, 1959-2 C.B. 146 .............. ........... . 25, 34

Rev. Rul. 66-323, 1966-2 C.B. 216... ........................ 25

xvii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

xviii

Rev. Rul. 67-825, 1967-2 C.B. 113 ............................. 32, 84

Rev. Rul. 69-545, 1969-2 C.B. 117 ___ 25

Rev. Rul. 71-447, 1971-2 C.B. 230_________ passim

Rev. Rul. 75-231, 1975-1 C.B. 158_____ passim

Rev. Rul. 76-204 1976-1 C.B. 152 ...... ............... . 25, 30

Rev. Rul. 77-126, 1977-1 C.B. 48 ____ _____ _____ 46

Rev. Rul. 78-85, 1978-1 C.B. 150.......... ................... 25

S. 992,1 C.B. 145 (1919) .............. .......... .................... 30, 40

S. 1176, 1 C.B. 147 (1919) ....... .................. 31

S. 1362, 2 C.B. 152 (1920) ......................................... 31

S.M. 1836, III-l C.B. 273 (1924)_____ _________ 31-32

Sol. Op. 159, III-l C.B. 480 (1924) ___ _______20, 30, 33

MISCELLANEOUS:

15 Am. Jur. 2d Charities §26 (1976) __________ 23

42 Am. Jur. 2d Inheritance, Estate and Gift Taxes

§§ 209,234,439 (1969) _________________ ___ 22

12 The American and English Encyclopedia of Law

(2d ed. 1899)____________________________ _ 27

Appendix, Norwood v. Harrison, No. 72-77 (U.S.

1973) .......... ......................... ..................................... 59

Appendix, Boh Jones University v. Simon, No. 72-

1470 (U.S. 1974) __________________________ 42

Brief for Petitioner, Bob Jones University v.

Simon, No. 72-1470 (U.S. 1974) ........................... 56

Brief for Respondents, Bob Jones University v.

Simon, No. 72-1470 (U.S. 1974) ______ __ ____ 59

Bittker & Kaufman, Taxes and Civil Rights: “Con

stitutionalizing” the Internal Revenue Code, 82

Yale L.J. 51 (1972) _____ _________ _________ 62

Bittker & Rahdert, The Exemption of Nonprofit

Organizations from Federal Income Taxation,

85 Yale L.J. 299 (1976)____________________ 19

Black, A Treatise on Federal Taxes (4th ed. 1919).. 22

Black’s Law Dictionary (rev. 5th ed. 1979) ...... 37

Bogert & Bogert, Law of Trusts (5th ed. 1973) .... 27

Bogert & Bogert, Trusts and Trustees (rev. 2d ed.

1977)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

39,43

XIX

Brown, Regulations, Reenactment, and the Reve

nue Acts, 54 Harv. L. Rev. 377 (1941) .............. 55

Brunyate, The Legal Definition of Charity, 61 Law

Q. Rev. 268 (1945) .... ................ ............. .............. 20

Carter & Crawshaw, Tudor on Charities (5th ed.

1929)—- .... - ............... .............. ........... .............. ....... 21

Eliot, The Exemption from Taxation (1874), in 2

Charles W. Eliot, The Man and His Beliefs 667

(1926)..... .......... .................. ............. ......................... 23

48 Fed. Reg. 37,296 (1978).......................... ............. 52

44 Fed. Reg. 9451 (1979)....... .................................. 52

Fiseh, Freed & Schachter, Charities and Char

itable Foundations (1974).............................22, 23-24, 48

Foster, A Treatise on the Federal Income Tax

under the Act of 1913 (2d ed. 1915) ..... —........... 22

Hopkins, The Law of Tax-Exempt Organizations

(3d ed. 1979) -------- ---- -------- -------- --- -....... ----- 19

2 Perry, Trusts and Trustees (2d ed. 1874) — .... 20, 28

Reiling, Federal Taxation: What Is a Charitable

Organization? 44 A.B.A. J. 525 (1958) ..20,22,37,40

Restatement (Second) of Judgments (1982).......... 4

Restatement (Second) of Trusts (1959)............. 28,43-44

Ross, Inheritance Taxation (1912).......... ............ - 23

26 Rul. Case Law § 281 (Perm. Supp. ed. 1929).... 23

4 Scott, Law of Trusts (3d ed. 1967 & Interim

Supp. 1981).... ....................................20, 23, 28, 39, 40, 43

Simon, The Tax-Exempt Status of Racially Dis

criminatory Religious Schools, 36 Tax L. Rev.

477 (1981) .....................................-........-----.........- - 43-44

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Southern School

Desegregation 1966-67 (1967) ..... ..................... . 13,14

Zollman, American Law of Charities (1924)......... 19

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

I n T h e

Supreme (&mrt at % Imftit

October T e r m , 1982

Nos. 81-1 and 81-3

Goldsboro Ch r istia n Schools, I n c .,

Petitioner,

U n ited States of A m erica ,

_______ Respondent.

B ob J ones U n iversity ,

Petitioner,

U n it ed States of A m erica ,

Respondent.

On Writs of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF THE JUDGMENTS BELOW

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT OF AMICUS CURIAE

The Internal Revenue Service has ruled that

§§ 501(c) (3) and 170 of the Internal Revenue Code do

not authorize recognition of tax benefits for racially dis

criminatory private schools. Rev. Rul. 71-447, 1971-2

C.B. 230; Rev. Rul. 75-231, 1975-1 C.B. 158. The Gov

ernment has defended this well-established position suc

cessfully in the Court of Appeals and previously before

this Court, but the present Administration, without any

2

change in the Code, now contends that the IRS position is

unauthorized. This Court therefore appointed an amicus

curiae to defend the judgments below. A summary of the

pertinent facts leading to that development is appropriate

to explain the interest that amicus curiae has thereby

come to represent.

These cases stem from the denial of tax-exempt status

under § 501(c) (3) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1954

(the “Code” ), 26 U.S.C. § 501(c) (3), to petitioners

Goldsboro Christian Schools, Inc. (“Goldsboro” ) and Bob

Jones University (“Bob Jones”) on the basis of their

racially discriminatory practices. Goldsboro denies ad

mission to all black applicants. J.A. 9. Bob Jones de

nied admission to all blacks prior to 1971 and to all un

married blacks until 1975, the last tax year in question.

J.A. A32-33. It continues to deny admission to persons

who marry or date outside their race and to enforce other

racially discriminatory rules. J.A. A197, A208.

Petitioners instituted separate tax refund actions.1 The

district court in Goldsboro ruled for the Government and

entered judgment against Goldsboro in the amount of

$116,190.99 for federal social security (“FICA”) and

unemployment (“FUTA” ) taxes due. J.A. 115; 436 F.

Supp. 1314 (E.D.N.C. 1977). The district court in Bob

Jones held that the school was entitled to an exemption,

relieving Bob Jones of the Government’s FICA and FUTA

claims totalling approximately $490,000 for the years

1970 through 1975. 468 F. Supp. 890 (D.S.C. 1978).2

1 If successful, petitioners would pay no federal income, social

security or unemployment taxes, would be eligible to receive charita

ble contributions deductible from the donor’s gross income or estate,

and would be included in the IRS publication of organizations hav

ing advance assurance of eligibility for charitable contributions.

2 In a separate action filed following the district court’s decision,

Bob Jones obtained preliminary injunctive relief compelling the IRS

to restore its tax-exempt status under § 501(c) (3) and to provide

advance assurance of the deductibility of contributions under § 170

by including Bob Jones in the Cumulative List of Organizations

published by the IRS. J.A. A3; Pet. App. A72-86. This order was

3

The district court concluded that Bob Jones’ “primary

purpose is religious,” but also found that it “serves educa

tional purposes,” 468 F. Supp. at 895. Bob Jones’ present

assertion that it is exclusively a religious organization,

B.J. Br. at i, is not supported by the record, which shows

that the school provides accredited, secular instruction at

all grade levels, offering courses in mathematics, science,

fine arts, history, education, literature, business adminis

tration and other subjects. See, e.g., J.A. A63, A127-28,

A227; U.S. Br. at 2-3. Goldsboro concedes that it is an

educational organization. G. Br. at i, 8.

On appeal, the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit held in both cases that § 501(c) (3) does

not authorize the granting of tax-exempt status to ra

cially discriminatory schools, regardless of the religious

basis for their practices, and that denial of this tax bene

fit does not infringe upon First Amendment religious

freedoms. Boh Jones, 639 F.2d 147 (4th Cir. 1980) ;

Goldsboro, No. 80-1473 (4th Cir. Feb. 24, 1981) (per

curiam) (Pet. App. la-3a).

Petitioners sought review here. In response, the Gov

ernment argued that the Fourth Circuit decisions were

correct but urged the Court to grant the petitions for

certiorari in order to “dispel the uncertainty surrounding

the propriety of the Service’s ruling position and foster

greater compliance on the part of the affected institu

tions,” U.S. Br., Sept. 9, 1981, at 17. The petitions were

granted on October 13,1981.

Just before its brief on the merits was due, however,

the Administration reversed its position.3 On January 8,

stayed by the Fourth Circuit pending appeal. J.A. A17; Pet. App.

A97-99. The appeal was later consolidated with the Government’s

appeal from the district court’s original decision, J.A. A8, and is

before this Court on Bob Jones’ petition for certiorari.

s For the circumstances surrounding the change in position, see

Administration’s Change in Federal Policy Regarding the Tax

Status of Racially Discriminatory Private Schools: Hearing Before

4

1982, the Acting Solicitor General filed a memorandum

informing the Court that the Department of the Treas

ury intended to initiate the steps necessary to revoke

Rev. Rul. 71-447 and other pertinent rulings and to rec

ognize § 501(c) (3) exemptions for petitioners, suggest

ing that these cases therefore were moot. But legal con

straints made implementation of the Administration’s

changed position impossible. In an action against

the Government in 1971, a three-judge court had

rendered a declaratory judgment that racially dis

criminatory private schools are ineligible for tax-exempt

status under § 501 (c) (3) and as donees of deducti

ble charitable contributions under § 170. Green v. Con-

nally, 330 F. Supp. 1150, 1179 (D.D.C. 1971). Upon

appeal by intervening white parents and school children,

this Court unanimously affirmed without opinion. Coit v.

Green, 404 U.S. 997 (1971). This declaratory judgment

remains in effect and is binding on the Government.* 4 5

Moreover, in a case involving similar issues, the Court

of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, on Feb

ruary 18, 1982, enjoined the Government from granting

1501(c)(3) tax-exempt status to any school that dis

criminates on the basis of race. Wright v. Regan, No.

80-1124, Order (per curiam).

Because of the injunction in Wright the United States

informed the Court that it would not revoke the revenue

rulings and would not grant petitioners tax-exempt status.

It therefore withdrew its request that these cases be dis

missed as moot and instead suggested appointment of an

amicus curiae to support the judgments below in favor

of the United States.® The United States filed its brief

the House Comm, on Ways and Means, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982)

{“1982 Hearing”) .

4 28 U.S.C. § 2201 (“declaration shall have the force and effect

of a final judgment”) ; see Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113, 166 (1973);

Restatement (Second) of Judgments § 33 (1982).

5 The Government and petitioners are correct in concluding that

these cases are not moot. The Government has not granted exemp

tions under § 501(c) (3) to petitioners, nor refunded the taxes paid,

5

on the merits on March 3, 1982, urging reversal of the

Fourth Circuit’s decisions. The Court, by its order of

April 19, 1982, invited William T. Coleman, Jr. “to brief

and argue these cases, as amicus curiae, in support of

the judgments below.” 50 U.S.L.W. 3837. Accordingly,

amicus curiae files this brief in support of the position

heretofore taken in these and other proceedings by the

United States.

nor revoked the revenue rulings which deny such exemptions. The

Administration’s changed view, therefore, does not moot the litiga

tion. North Haven Bd. of Educ. v. Bell, 102 S. Ct. 1912, 1918 n.12

(1982). Even if the Government were to implement its changed posi

tion the case would not be moot. See United States v. W.T. Grant

Co., 345 U.S. 629, 632-33 (1953); Green v. Connally, 330 F. Supp.

at 1170.

The cases come to this Court on records developed through the

adversary process. They are still adversarial in the operative sense

because the Administration has not granted the relief petitioners

seek and cannot do so while the declaratory judgment in Green and

the injunction in Wright are in effect. There remains, therefore, a

justiciable controversy. Kentucky v. Indiana, 281 U.S. 163, 173

(1930); see GTE Sylvania, Inc. v. Consumers Union, 445 U.S. 375,

382-83 (1980); cf. United States v. Lovett, 328 U.S. 303, 306 (1946).

The Court has properly invited an amicus curiae to present the

opposing view which had been successfully argued by the Govern

ment in the court below. Cheng Fan Kwok v. INS; 392 U.S. 206,

210 n.9 (1968); see also Granville-Smith v. Granville-Smith, 349

U.S. 1 (1955); Brown v. Hartlage, 102 S. Ct. 1523, 1526 n.l

(1982). Finally, the Court could not accept the present Adminis

tration position, vacate the judgments below and order refund of

the FICA and FUTA taxes paid by petitioners without conducting

an independent review of the merits. See Rosengart v. Laird, 405

U.S. 908 (1972) ; Richmond Television Corp. v. United States, 382

U.S. 68 (1965); Weber v. United States, 119 F.2d 932 (9th Cir.

1941), aff’d per curiam by an equally divided Court, 315 U.S. 787

(1942) ; id. at 935 (dissenting opinion); see also Bruton v. United

States, 391 U.S. 123, 125-26 (1968); Young v. United States, 315

U.S. 257, 258-59 (1942).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Since Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954), the actions of Congress and the decisions of this

Court have expressed a fundamental national policy, de

rived from the Fifth, Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amend

ments, condemning racial discrimination in education—

public and private. This Court has consistently and un

equivocally ruled that government support of segregated

schools “through any arrangement, management, funds,

or property” is unconstitutional. Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U.S. 1, 19 (1958); see Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455

(1973). In Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976),

the Court squarely held that Section 1 of the Civil Rights

Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1981, prohibits racially discrim

inatory practices in private schools.

Recognizing the development of this fundamental na

tional policy, the IRS, in light of the statutory require

ments governing charitable organizations, decided in

1970 that private schools practicing racial discrimi

nation are not entitled to tax-exempt status under

§ 501(c) (3) of the Code or eligible for deductible chari

table contributions under § 170. See J.A. A235-239; Rev.

Rul. 71-447, 1971-2 C.B. 230. Contrary to the Govern

ment’s suggestion, this decision was not a reversal of

previous IRS practice. Rather, given the evolution of

constitutional and statutory law after Brown, this rul

ing followed inevitably from the long-standing position

of the IRS that §§ 501(c) (3) and 170 provide tax bene

fits only for organizations charitable in the common law

sense. A three-judge court upheld the denial of tax-

exempt status to racially discriminatory private schools

in Green v. Connolly, 330 F. Supp. 1150 (D.D.C. 1971).

This Court’s affirmance of the three-judge court ruling,

Coit v. Green, 404 U.S. 997 (1971), was a correct decision

on the merits, and nothing has occurred since which sug

gests any basis for overruling it. On the contrary, con

gressional actions since 1970 have expressly ratified the

IRS ruling upheld in Green.

6

7

The Commissioner’s obligation under the Code to deny

tax-exempt status to private schools that discriminate on

the basis of race is supported by several distinct but

mutually reinforcing statutory grounds:

1. As the IRS ruled, § 501(c) (3) was intended to pro

vide tax-exempt status only for charitable organizations

in the common law sense. It is a basic precept of the

common law that the special privileges afforded to chari

table organizations are based upon their contribution

to the general welfare, and thus that an organization is

not entitled to charitable status if its purposes are incon

sistent with law or fundamental public policy. Oulcl v.

Washington Hospital for Foundlings, 95 U.S. 303, 311

(1877) ; Perm v. Carey, 24 How. 465, 501 (1861). The

language and legislative history of 1501(c)(3) reflect

congressional intent to adopt this principle. The courts

and the IRS have been guided accordingly and have long

relied upon common law concepts of charity to determine

the applicability of § 501(c) (3) to “educational” organi

zations. This long-standing construction of § 501(c) (3)

was adopted by Congress when it re-enacted the Code in

1954 and again in enacting the Tax Reform Act of 1969.

In this light, there is no merit to the argument of

the Government and petitioners that the term “educa

tional” in § 501(c) (3) must be construed as entirely

independent of the law of charity solely because the

terms of the statutory expression “religious, charitable

. . . or educational purposes” are separated by the dis

junctive. This argument tears the term “educational”

from its statutory context and historic origins in the

common law, ignores the statute’s legislative history, and

disregards its long-standing judicial and administrative

construction. Even in strictly grammatical terms, the

more reasonable interpretation of the statute is that

its specific terms provide descriptive examples of or

8

ganizations that are charitable in the generic sense.

See 26 U.S.C. § 170(c) (2) (defining “charitable con

tributions” as contributions to “religious, charitable, . . .

or educational” organizations). In interpreting other

Code provisions listing terms sharing a common denom

inator but separated by the word “or,” the Court has

often held that a single word in the list—here “educa

tional”—“does not stand alone, but gathers meaning from

the words around it.” Jarecki v. G.D. Searle & Co., 367

U.S. 303, 307 (1961) ; see National Muffler Dealers Asso

ciation v. United States, 440 U.S. 472 (1979).

2. Recognition of tax-exempt status for racially dis

criminatory private schools, moreover, would contravene

the established judicial presumption against congressional

intent to allow tax benefits where they would frustrate

a sharply defined governmental policy. Tank Truck

Rentals, Inc. v. Commissioner, 356 U.S. 30, 33-35 (1958).

Here, recognition of tax exemption would be utterly

inconsistent with federal law and fundamental national

policy condemning racial discrimination in public and

private education, severely undermining the Court’s man

date to desegregate the public schools as well as the con

stitutionally-based policy against government support for

segregated private schools.

3. Congress has been fully aware of the IRS decision

on this issue since the day it was made, and has re

peatedly refused to alter the IRS ruling, even while

amending § 501(c) (3) in other respects. Furthermore,

in enacting § 501 (i) in 1976, Congress expressly adopted

the IRS’ decision as “national policy.” S. Rep. No. 1318,

94th Cong., 2d Sess. 8 (1976). Congress recognized that

the court in Green had held that the existing language of

1501(c)(3) barred tax-exempt status for racially dis

criminatory schools and thus saw no need to adopt addi

tional language to this effect. Instead, Congress extended

this policy to private social clubs practicing racial dis

crimination, a positive legislative action plainly signal

9

ing approval of the IRS ruling on discriminatory

schools. It is inconceivable that the Congress which

mandated denial of tax-exempt status for discrimina

tory social clubs, including school fraternities, could

have intended to permit discriminatory practices by

the tax-exempt schools themselves. Congress reaffirmed its

support for the IRS ruling in 1979 when it enacted the

Dornan and Ashbrook Amendments to bar implementa

tion of proposed new “affirmative action” requirements

for private schools. A fair reading of these develop

ments since 1970 can leave no reasonable doubt that

Congress has ratified and approved the IRS policy in

Rev. Ruls. 71-447 and 75-231. Haig v. Agee, 453 U.S.

280, 300-01 (1981) ; Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. FCC,

395 U.S. 367, 381-82 (1969).

Indeed, if § 501(c) (3) were construed to permit tax

exemptions for racially discriminatory schools, the provi

sion would be unconstitutional under the Fifth Amend

ment. The Government has an affirmative constitutional

duty to steer clear of providing significant aid to

such schools, even in the absence of any purpose to further

the schools’ racially discriminatory practices. Norwoodl v.

Harrison, 413 U.S. 455, 465 (1973).

For all these reasons, the IRS properly concluded that

racially discriminatory private schools are not entitled

to exempt status under § 501(c) (3). There is no ques

tion that both petitioners engage in racially discrimina

tory practices. While Bob Jones argues that it is entitled

to exempt status under § 501(c) (3) as a “religious” or

ganization, the record demonstrates that it is not a church

or seminary engaged exclusively in religious activities,

but rather a school providing accredited secular education

at all levels.

Ultimately, petitioners argue that the First Amend

ment’s protection of religious freedom requires that they

10

be excepted from the rulings barring tax-exempt status

for all other racially discriminatory private schools. But

the right to free exercise of religion does not guarantee

entitlement to tax-exempt status. Rev. Ruls. 71-447 and

75-231 do not restrict petitioners’ right to hold or teach

their religious beliefs, nor do these rulings prevent them

from continuing their discriminatory practices without the

benefit of government subsidy. If there is any burden

on petitioners’ free exercise here, it is far outweighed by

the compelling governmental interest in eliminating all

forms of official support for racial discrimination in

education. Norwood v. Harrison, supra. If the Establish

ment Clause has any bearing here, it is to prohibit spe

cial tax preferences for religiously-motivated racial dis

crimination. To give favored tax treatment to racially

discriminatory sectarian schools while denying tax bene

fits to private schools that claim no religious basis for

their racially discriminatory practices would impermissi

bly entangle government with religion.

Since the United States does not support petitioners

on their First Amendment claims, the principal issue

here, as framed by the Government, is whether the Court

should overrule Coit v. Green and the Commissioner’s

firmly established practice, ratified by Congress, of deny

ing tax-exempt status to racially discriminatory schools.

The Government states that it fully subscribes to “the

strong national policy in this country against racial dis

crimination in any and all forms.” U.S. Br. at 11. But

this is an empty assurance if schools that admittedly dis

criminate on the basis of race are nonetheless afforded

significant tax benefits. Surely, the constitutional and

congressional command to eradicate the badges and inci

dents of slavery demands more.

11

ARGUMENT

I. THE IRS RULING DENYING TAX-EXEMPT

STATUS TO RACIALLY DISCRIMINATORY PRI

VATE SCHOOLS WAS A NECESSARY RESULT

OF FUNDAMENTAL DEVELOPMENTS IN STAT

UTORY AND CONSTITUTIONAL LAW

On May 17, 1954, this Court established the funda

mental principle that racial segregation in public educa

tion violates the Fourteenth and Fifth Amendments.

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ;

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954). In the interven

ing 28 years, the courts and Congress have spelled out a

national commitment to eliminate racial discrimination

from virtually all institutions of American life. Nowhere

is this commitment greater than in the field of education.

From Brown, 347 U.S. at 493, to Washington v. Seattle

School District No. 1, 102 S. Ct, 3187, 3196 (1982), and

Plyler v. Doe, 102 S. Ct. 2382, 2397-98 (1982), the Court

has repeatedly emphasized the surpassing importance of

education in providing minority groups with a meaningful

opportunity to achieve their rightful place in American

society, and the devastating impact that racial segrega

tion in education can have on children subjected to it.

Accordingly, as the Court held in Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U.S. 1,19 (1958) :

State support of segregated schools through any ar

rangement, management, funds, or property cannot

be squared with the [Fourteenth] Amendment’s com

mand that no State shall deny to any person within

its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

The right of a student not to be segregated on racial

grounds in schools so maintained is indeed so fun

damental and pervasive that it is embraced in the

concept of due process of law.

Throughout the 1960’s, Congress translated the na

tional policy against racial discrimination into legisla

tion reaching most areas of American society. In the

12

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000a ei seq.,

Congress put the full force of federal law behind pro

hibitions against racial segregation in public accommoda

tions, employment and education. See Titles IV and VI,

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000c & 2000d; see also, e.g., the Voting

Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1971 et seq; and the

Civil Rights Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C. §§ 3601 et seq.

(housing).,

This Court, at the same time, recognized that the Civil

Rights Acts adopted in the post-Civil War era had al

ready made private discrimination unlawful in many

walks of life. In Jones v. Alfred. H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S.

409 (1968), the Court held that 42 U.S.C. § 1982 pro

hibits private racial discrimination in the sale or rental

of property. The Court concluded that the Civil Rights

Act of 1866 prohibited private interference with the

enumerated rights and that this broad prohibition was

within Congress’ power under the Thirteenth Amend

ment to determine “the badges and the incidents of slav

ery, and . . . to translate that determination into effec

tive legislation.” 392 U.S. at 440.

The conclusion of Jones—that the Civil Rights Act of

1866 “operates upon the unofficial acts of private individ

uals,” Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U.S.

229, 235 (1969)—clearly applied as well to 42 U.S.C.

§ 1981, a companion provision which guarantees black

citizens other equal rights, including the right to make

contracts. Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, 421 U.S.

454, 459-60 (1975) ; Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven Recrea

tion Association, 410 U.S. 431, 439-40 (1973) ; Waters

v. Wisconsin Steel Works, 427 F.2d 476, 483 (7th Cir.),

cert, denied, 400 U.S. 911 (1970). Thus, when in 1970

the IRS issued the ruling here challenged by petitioners,

there was a sound basis upon which to conclude that

racial discrimination by private schools in their admis

sion of students violated 42 U.S.C. § 1981. In Runyon v.

McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976), this Court so held. In

deed, by the time Runyon was decided, the Court could

13

state that § 1981’s prohibition of racial discrimination

in the making and enforcement of private contracts was

“now well established,” id at 168, and that a segregated

private school’s discrimination against blacks “amounts

to a classic violation of § 1981,” id. at 172.®

While the national policy against racial discrimination

in education, public and private, was thus being articu

lated, implementation of the Brown decision proved to be

far more difficult than anticipated. Swann v. Chariotte-

Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 13 (1971).

The widespread proliferation of segregated white private

schools, often supported by substantial state assistance,

seriously undermined efforts to desegregate the public

schools. See Griffin v. County School Board, 377 U.S.

218 (1964).6 7 Throughout the 1960’s, the federal courts

repeatedly struck down state and local efforts to provide

financial assistance to such schools, usually in the form

of tuition grants; this Court consistently affirmed these

decisions summarily. See Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S.

455, 463 & n.6 (1973), and cases cited. In consequence,

the tax benefits provided by §§ 170 and 501(c) (3) as-

6 Although the Court, has not squarely ruled on the point, concerted

activity to deprive blacks of rights secured by § 1981 may constitute

a criminal conspiracy under 18 U.S.C. § 241. See Jones v. Alfred

H. Mayer Co., supra, 392 U.S. at 441-43 n.78, overruling Hodges v.

United States, 203 U.S. 1 (1906); United States v. Morris, 125

F. 322 (E.D. Ark. 1903). See also United States v. Price, 383 U.S.

787, 800-05 (1966). Such activity may also constitute a civil con

spiracy under 42 U.S.C. § 1985(3). See Griffin v. Breckenridge,

403 U.S. 88 (1971).

7 See also United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ., 372

F.2d 836, 848-49 (5th Cir. 1966); Green v. Kennedy, 309 F. Supp.

1127, 1133-36 (D.D.C.), appeal dismissed sub nom. Cannon v. Green,

398 U.S. 956 (1970) ; Poindexter v. Louisiana Financial Assistance

Comm’n, 275 F. Supp. 833, 851, 856-57 (E.D. La. 1967), aff’d,

389 U.S. 571 (1968); U.S. Comm’n on Civil Rights, Southern

School Desegregation 1966-67 at 70-76 (1967); Equal Educational

Opportunity: Hearings Before the Senate Select Comm, on Equal

Educational Opportunity, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. 1931 et seq. (1970)

(“1970 Hearings”).

14

sumed a “critical significance” in enabling these schools

to flourish. Green v. Kennedy, 309 F. Supp. 1127, 1135

(D.D.C.) (three-judge court), appeal dismissed sub nom.

Cannon v. Green, 398 U.S. 956 (1970). See U.S. Com

mission on Civil Rights, Southern School Desegregation

1966-67 at 75-76 (1967); 1970 Hearings, supra note 7,

at 1941-43, 1954-55, 1966, 1983-84.

Thus, in 1969 black parents and students in Mississippi

brought the Green action challenging the IRS’ continued

recognition of tax-exempt status for segregated private

schools in that state. The three-judge court recog- -

nized that tax-deductible contributions had become the-

major source of funding for these private schools, pro

viding crucial support to meet the schools’ capital needs

and operating expenses and thus allowing the schools

to expand segregated education at the expense of the de

segregated public schools. 309 F. Supp. at 1135. Finding

that plaintiffs’ challenge raised “grave constitutional

questions,” id. at 1133, the court preliminarily enjoined

the IRS in early 1970 from continuing to recognize tax-

exempt status for segregated private schools in Mississippi.

Against this background, the IRS in July 1970 con

cluded that it could “no longer legally justify allowing

tax-exempt status to private schools which practice racial

discrimination” under § 501(c) (3), “nor [could] it treat

gifts to such schools as charitable deductions for income

tax purposes” under § 170. J.A. A235. The IRS formally

adopted this position in Rev. Rul. 71-447, 1971-2 C.B.

230, the full text of which is set out in Appendix A to

this brief.8 The IRS explained: “Both the courts and the

Internal Revenue Service have long recognized that the

8 The IRS made clear at the outset that its position applied to all

private schools, whether church-related or not. J.A. A237-239; see

Rev. Rul. 75-231, 1975-1 C.B. 158. Procedures relating to enforce

ment of these revenue rulings were promulgated in Rev. Proc. 72-

54, 1972-2 C.B. 834; Rev. Proc. 75-50, 1975-2 C.B. 587.

15

statutory requirement of being ‘organized and operated

exclusively for religious, charitable, . . . or educational

purposes’ was intended to express the basic common law

concept [of charity].” In particular, the IRS emphasized

the common law principle that an organization is not

“charitable” if its purposes are illegal or contrary to

fundamental national policy. The IRS found that “ [t]he

Federal policy against racial discrimination is well-

settled in many areas of wide public interest,” particu

larly “in education, whether public or private.” 9

This ruling was not a product of mere IRS “whim,”

Bob Jones, 468 F. Supp. at 905, nor was it simply a

reaction to the preliminary injunction entered in Green.

Rather, it was the outcome of years of serious considera

tion of the issue in light of the emerging national policy

against racial discrimination in education. 1982 Hear

ing, supra note 8, at 84, 88-97; 1970 Hearings, supra

note 7, at 2001.10 The decision was personally approved

by President Nixon, 1982 Hearing at 84-85; 1970 Hear

ings at 1998, and has been enforced consistently by every

Administration until now.

9 Rev. Ruls. 71-447 and 75-231 remain in effect and had the sup

port of the IRS, the agency charged with enforcement of the Code,

as well as of the Tax Division of the Department of Justice, through

out the debate leading to the Administration's change in position.

See, e.g., 1982 Hearing* supra note 3, at 153, 156, 178, 226, 256, 259,

454,472-531.

10 The IRS in iti& M is study of this issue in the late 1950’s and

began to impleineni^Jchanges regarding racially discriminatory

schools in 1965. ‘|j|ll969, at the urging of Congress, a blue ribbon

Advisory Committee on Exempt Organizations was appointed to

analyze federal law and policy governing tax-exempt organizations.

The Committee’s reaffirmation that tax-exempt status was intended

only for organizations charitable in the common law sense, which

do not violate fundamental national policy, was influential in the

IRS’ 1970 decision. See 1982 Hearing at 84, 88, 90-94; 1970 Hear

ings at 2001.

16

The IRS ruling was upheld by the three-judge court

in Green v. Connally, 330 F. Supp. 1150 (D.D.C. 1971).

The court recognized the force of the IRS’ reliance on

the common law background of § 501(c) (3), id. at

1157-61, but rested its holding on the well-established

presumption against the allowance of federal tax bene

fits that would frustrate other sharply defined govern

mental policies. Tank Truck Rentals, Inc. v. Commis

sioner, 356 U.S. 30 (1958). Noting that Tank Truck

held that business expense deductions were properly denied

on this ground, the court stated:

This public policy limitation on tax benefits applies

a fortiori to the case before us, involving the charita

ble deduction whose very purpose is rooted in help

ing institutions because they serve the public good.

The Internal Revenue Code does not contemplate the

granting of special Federal tax benefits to trusts or

organizations . . . whose organization or operation

contravene Federal public policy.

330 F. Supp. at 1162. Concluding that the recognition

of tax-exempt status for segregated private schools would

frustrate the most fundamental and clearly established

national policies, id. at 1163-64, the court in Green issued

a declaratory judgment upholding the IRS’ interpretation

of § 501(c) (3) and granted permanent injunctive relief

barring tax-exempt status for discriminatory private

schools in Mississippi. Intervenors appealed, raising

arguments similar to those upon which petitioners and

the Government here rely. See 1982 Hearing at 275-353.

This Court affirmed per curiam, without opinion. Coit

v. Green, 404 U.S. 997 (1971). For the reasons which

follow, that decision was correct and should not now be

overruled.

17

II. CONGRESS INTENDED TO GRANT TAX BENE

FITS UNDER §§ 501(c)(3) AND 170 TO CHARITA

BLE ORGANIZATIONS IN THE COMMON LAW

SENSE AND THUS NOT TO ORGANIZATIONS

WHOSE ACTIVITIES ARE UNLAWFUL OR VIO

LATE FUNDAMENTAL NATIONAL POLICIES

Section 501(c) (3) of the 1954 Internal Revenue Code,

as it was in effect during the relevant period,11 provided

an exemption from federal income tax for

Corporations, and any community chest, fund, or

foundation, organized and operated exclusively for

religious, charitable, scientific, testing for public

safety, literary or educational purposes, or for the

prevention of cruelty to children or animals, no part

of the net earnings of which inures to the benefit of

any private shareholder or individual . . . .

Tax-exempt status under § 501(c) (3) controls the Code’s

exemption for charitable organizations from federal so

cial security taxes, § 3121(b) (8) (B), and from federal

unemployment taxes, § 3306(c) (8), the taxes directly at

issue here.

Eligibility to receive tax-deductible charitable contri

butions under § 170 of the Code is determined in accord

ance with a substantially identical standard. Section

170(c) (2) (B) provides a deduction for income tax pur

poses for a “charitable contribution,” defined to include

contributions to organizations “operated exclusively for

religious, charitable, scientific, literary, or educational

purposes.” These two closely-related provisions must be

construed in pari materia. U.S. Br. at 14. See Harris v.

Commissioner, 340 U.S. 106, 107 (1950) ; United States v.

Stewart, 311 U.S. 60, 64 (1940).12

11 Section 501(c) (3) was amended in 1976 also to embrace organi

zations “to foster national or international amateur sports competi

tion.” Tax Reform Act of 1976, Pub. L. No. 94-455, § 1313(a), 90

Stat. 1520, 1730 (1976).

12 Thirteen other provisions of the Code contain similar or identi

cal references to “religious, charitable . . . or educational purposes”

18

A. The Language of §§ 501(c)(3) and 170 Reflects Their

Origins in the Common Law and in English and

State Tax Exemption Statutes

The operative language in §§ 501(c) (3) and 170 is

derived from the earliest federal revenue statutes. The

first general income tax law passed by Congress, the

Tariff Act of 1894, exempted “corporations, companies,

or associations organized and conducted solely for chari

table, religious or educational purposes.” Ch. 349, § 32,

28 Stat. 509, 556 (1894). That Act was held unconstitu

tional, Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Co., 158 U.S.

601 (1895), and was never implemented. But in enacting

a tax on corporate incomes in 1909, Congress exempted

“any corporation or association organized and operated

exclusively for religious, charitable, or educational pur

poses, no part of the net income of which inures to the

benefit of any private stockholder or individual.” Tariff

Act of 1909, ch. 6, § 38, 36 Stat. 11, 113 (1909). After

the Sixteenth Amendment, Congress enacted the Tariff

Act of 1913, the first modern income tax law. Chapter

16, § (G) (a), 38 Stat. 114, 172 (1913), the direct prede

cessor of § 501(c) (3), provided an exemption virtually

identical in terms to the 1909 exemption, only adding

“scientific” to the statutory phrase. The terms of the

exemption have been carried forward in each subsequent

income tax act without basic change.13

These exemption provisions are part of a long-standing

practice in common law jurisdictions. The federal ex

in establishing exemptions from, or eligibility for deductions under,

income, estate, gift and excise taxes. 26 U.S.C. §§ 170(c) (4);

501(c) (10); 642(c); 2055(a)(2) & (3); 2106(a) (2) (A) (ii) & ( ii i) ;

2522(a)(2) & (3); 2522(b)(2), (3) & (4); 4911(e)(1)(A).

13 A deduction for charitable contributions to “religious, charitable

. . . or educational” organizations, equivalent to that now contained

in § 170(c), was first enacted in 1917, War Revenue Act, ch. 63,

§ 1201(2), 40 Stat. 300, 330, and has likewise been carried forward

without substantial change in each succeeding income tax law.

19

emption has “roots reaching back to the British Statute

of Charitable Uses of 1601 and to early state constitu

tional provisions.” Bittker & Rahdert, The Exemption

of Nonprofit Organizations from Federal Income Taxa

tion, 85 Yale L.J. 299, 301 (1976). See Hopkins, The

Law of Tax-Exempt Organizations § 1.2, at 5 (3d ed.

1979); Zollmann, American Law of Charities §§ 678, 701

(1924). Indeed, the practice of exempting charitable or

ganizations from tax was so well settled at common law

and in legislative practice that when Congress failed to

enact any express exemption in the 1862 income tax law

passed to help finance the Civil War, Act of July 1, 1862,

ch. 119, §§ 89-93, 12 Stat. 432, 473 (1862), the Commis

sioner of Internal Revenue nevertheless ruled that it was

not intended to apply to “ [t]he income of literary, scien

tific, or other charitable institutions.” Decision No. 110