Bryan v Koch Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

May 27, 1980

74 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bryan v Koch Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1980. e6ac4afa-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/50d1b670-9608-40dd-ac80-d64f47ee3a67/bryan-v-koch-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

1

2

4

5

8

15

15

16

18

23

23

D w id tr. & r Y *

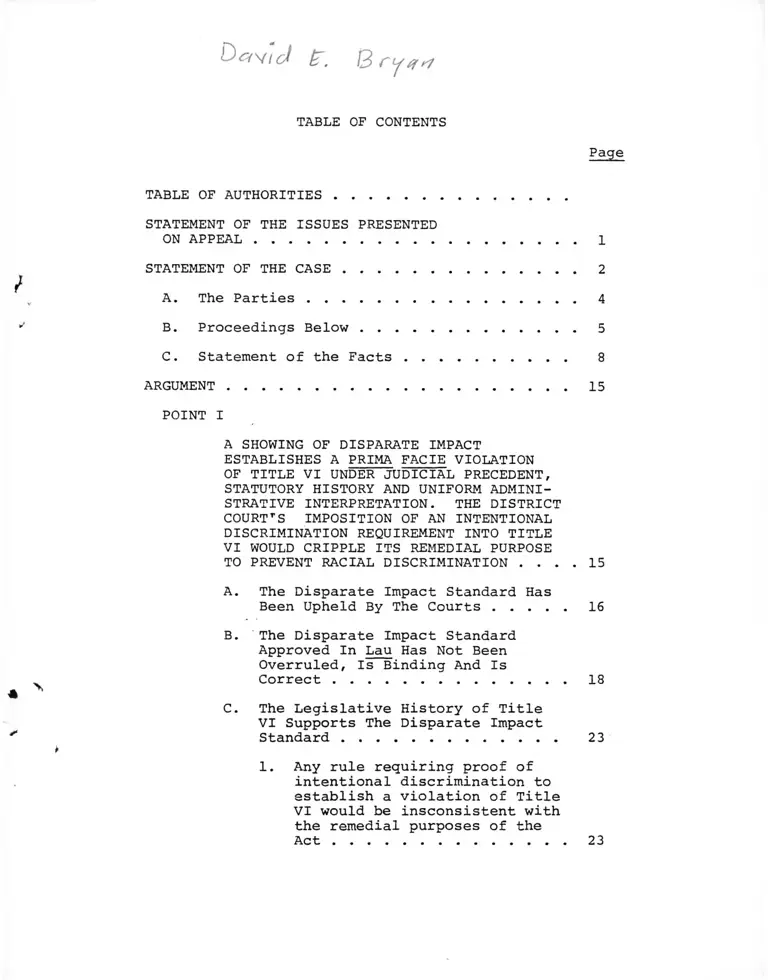

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ...........

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES PRESENTED

ON APPEAL .....................

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ...........

A. The Parties ...............

B. Proceedings Below ........

C. Statement of the Facts . .

ARGUMENT .......................

POINT I

A SHOWING OF DISPARATE IMPACT

ESTABLISHES A PRIMA FACIE VIOLATION

OF TITLE VI UNDER JUDICIAL PRECEDENT,

STATUTORY HISTORY AND UNIFORM ADMINI

STRATIVE INTERPRETATION. THE DISTRICT

COURTTS IMPOSITION OF AN INTENTIONAL

DISCRIMINATION REQUIREMENT INTO TITLE

VI WOULD CRIPPLE ITS REMEDIAL PURPOSE

TO PREVENT RACIAL DISCRIMINATION . . . .

A. The Disparate Impact Standard Has

Been Upheld By The Courts ........

B. The Disparate Impact Standard

Approved In Lau Has Not Been

Overruled, Is Binding And Is

Correct ............................

C. The Legislative History of Title

VI Supports The Disparate Impact

Standard ..........................

1. Any rule requiring proof of

intentional discrimination to

establish a violation of Title

VI would be insconsistent with

the remedial purposes of the

A c t ............................

Page

r

2. Sponsors of Title Vi refused to limit

its scope to the Equal Protection

standard.................................... 2 6

3. Congress enacted Title VI at a time

when the Equal Protection Clause was

believed to prohibit actions having

a discriminatory impact ..................... 28

4. Regulations issued by seven Rederal

agencies within months of the Act's

passage and again in 1973 indicate

their unanimous view that Title VI

prohibited conduct which had a dis

parate impact upon minorities............... 30

5. Congressional enactments subsequent to

1964 reflect a continued Congressional

understanding that Title VI prohibits

conduct having a disparate impact upon

minorities..................................... 32

H. Retention Of The Disparate Effect Standard

Is Necessary If Title VI Is To Be An

Effective Remedy To Prevent Racial Discrim

ination ............................................ 34

I. This Court Should Reach The Issue Of The

Proposed Standard Under Title VI To Govern

The Future Proceedings In This And Other

Cases ............................................... 39

POINT II

PLAINTIFFS ESTABLISHED A SUBSTANTIAL LIKELIHOOD

OF PREVAILING ON THEIR TITLE VI CLAIM; THE

DISTRICT COURT ERRONEOUSLY FAILED TO REQUIRE

DEFENDANTS TO PROVIDE ASSURANCES OF ALTERNATE

ACCESS TO ESSENTIAL SERVICES AND RELIED INSTEAD

ON A HYPOTHETICAL ACCESS CONSTRUCT ................. 40

A. The District Court Found And The

Unrebutted Evidence Established,

That The Impact Of The Closing Of

Sydenham Hospital Will Fall Exclu

sively On Minorities 41

Page

B. The Lack Of Assurance Of Alternate

Access For The Sydenham Patient Popula

tion Is Demonstrated By The Insufficiency

Of The Findings B e l o w ........................ 46

1. The Court below relied upon a

hypothetical construct that gave

no assurance that it was financially

feasible for private hospitals to

accept Sydenham patients ................. 47

2. The lack of assurance of available

beds for Sydenham patients............... 50

3. The clearly erroneous findings on access

to alternative emergency room services . .

C. In

Of

To

Light Of Plaintiffs' Unrebutted Evidence

Feasible Alternatives To Save Money And

Improve Health Care Without Closing

Sydenham, A Title VI Violation Has Been

Established ............................

1. Plaintiffs presented unrebutted evidence

that the City has ignored ways of

reducing HHC's deficit by millions of

dollars through mergers of municipal

hospitals..................................

2. The City ignored proposals for the

revision and expansion of services at

Sydenham Hospital..........................

3. The City Ignored Hospital Reductions and

Partial Closings as Alternatives To

Closing Entire Hospitals .................

CONCLUSION ,

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) . . . .

Arthur v. Nyquist, 573 F.2d 134 (2nd Cir. 1978) .........

Blackshear Residents Organization v. Housing

Authority of City of Austin, 347 F.Supp.

1138 (W.D. Tex. 1971) ..............................

Blake v. City of Los Angeles, 595 F .2d 1367 (9th

Cir. 1979) ...........................................

Board of Education v. Califano, 584 F.2d 576 (2nd Cir.

1978), aff'd on other grounds sub nom, Board of

Education v. Harris, U.S. , 100 S.Ct.

363 (1979)...........................................

Board of Education v. Harris, U.S. , 62 L.Ed. 2d

275 (1979)...........................................

Cannon v. University of Chicago, U.S. ' , 99

S.Ct. 1946 (1979) ..................................

Castenada v. Partita, 97 S.Ct. 1272 (1979) .............

Child v. Beame, 425 F.Supp. 194 (S.D.N.Y. 1977) .........

City of Mobile v. Bolden, ' U.S. , 48 U.S.L.W. 4436,

4437 (April 22, 1980)................................

City of Rome v. United States, ___ U.S. __, No. 78-1840

(U.S. Supreme Court slip opinion, April 22, 1980) . .

De La Cruz v. Tormey, 582 F.2d 45 (9th Cir. 1978) . . . .

Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321 (1977) ...............

Erlenbaugh v. United States, 409 U.S. 239 (1972) . . . .

Flood v. Kuhn, 407 U.S. 258 (1972) .....................

Ford Motor Credit Co. v. Millhollin, 48 U.S.L.W. 4145,

(U.S. Supfeme Court February 20, 1980). .'...........

Guadalupe Organization, Inc. v. Tempe Elementary School

District, 587 F.2d 1022 (9th Cir. 1 9 7 8 ) ........ ..

Page

Page

Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424 (1971)..............................

Guardians Association v. Civil Service Commission,

466 F.Supp. 1273 (S.D.N.Y. 1979) ...............

Hawkins v. Town of Shaw,

461 F .2d 1171 (5th Cir. 1972) ...................

Hicks v. Weaver, 302 F.Supp. 619 (E.D.La. 1969) . . . .

Hill v. Texas,

316 U.S. 400 (19421 ..............................

Johnson v. City of Arcadia,

450 F.Supp. 1363 (M.D.Fla. 1978) .................

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974).............

Lora v. Board of Education,

456 F.Supp. 1273 (S.D.N.Y. 1979) .................

Metropolitan Housing Development Corp. v. Village of

Arlingon Heights, 373 F.Supp. 208 (N.D. 111. 1974).

Metropolitan Housing Development Corp. v. Village of

Arlington Heights, 558 F.2d 1283 (7th Cir. 1977). .

Moor v. County of Alameda,

411 U.S. 693 (1973) ................................

Mourning v. Family Publications Service,

411 U.S. 356 (1973) ................................

NAACP v. Wilmington Medical Center,

453 F.Supp. 280 (D.Del. 1978) ................... .

Oklahoma v. Civil Service Commission, 330 U.S. 127 (1947).

Oppen v. Aetna Insurance Co.,

485 F .2d 252 (9th Cir. 1973) ........................

Owens v. City of Independence, Missouri,

___U.S. ____, 48 U.S.L.W. 4384 (April 16, 1980). . .

Patent Association of Andrew Jackson High School v .

Ambach, 598 F.2d 705 (2nd Cir. 1979) ...............

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co.,

494 F .2d 211 (5th Cir. 1974) ........................

Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. FCC,

395 U.S. 367 (1969) ..................................

Page

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 (1978)..................................

Resident Advisory Board v. Rizzo,

564 F .2d 126 (3rd Cir. 1977)........................

Rhem v. Malcolm,

507 F .2d 333 (2nd Cir. 1974) .....................

Robinson v. Lorrilard Corp.,

444 F .2d 791 (4th Cir. 1971) .....................

Robinson v. 12 Lofts Realty, Inc.,

610 F .2d 1032 (2nd Cir. 1979) .....................

Shannon v. U.S. Dept, of Housing and Urban Development,

436 F .2d 809 (3rd Cir. 1970)........................

Serna v. Portales Municipal Schools, 499 F.2d 1147

(10th Cir. 1974) ....................................

Smith v. Texas,

311 U.S. 128 (1940) ..................................

Steward Machine Co. v. Davis,

301 U.S. 548 (1937) ..................................

St. Louis-San Francisco Ry. Co. v. Willard Mirror Co.,

160 F.Supp. 895 (W.D.Ark. 1 9 5 8 ) ............... .. . .

Udall v. Tallman,

380 U.S. 1 (1965) ....................................

United Farmworkers v. City of Delray Beach,

493 F .2d 799 (5th Cir. 1974) ........................

United States v. Barbera, 514 F.2d 294 (2nd Cir. 1975) . .

United States v. Chase, 281 F.2d 225 (7th Cir. 1960) . . .

United States v. City of Black Jack,

508 F .2d 1179 (8th Cir. 1974) ........................

United States ex rel. Gockley v. Myers, 450 F.2d 232

(3rd Cir. 1971) . . . . . . . . . ...................

United States v. San Franciso,

310 U.S. 16 (1940) ..................................

Wade v. Mississippi Cooperative Extension Service,

528 F .2d 508 (5th Cir. 1976) ........................

Page

UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION

Fourteenth Amendment

FEDERAL STATUTES

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972,

20 U.S.C.A. §1681 ................................

§ 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, 29 U.S.C.A. "

§729 (1973) .........................................

§ 1681 of the Revenue Sharing Act, 31 U.S.C.A §1242 (1976)

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ...........................................

Title III of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. §2000b ..................................

Title IV of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. §2000c ....................................

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. §2000d ....................................

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. §2000e ....................................

Fair Housing Act,

42 U.S.C. §§3601, et seq............................

Crime Control Act of 1973,

42 U.S.C. §3766 .......................................

Housing and Community Development Act of 1974,

42 U.S.C. §5309 .......................................

Juvenile Justice Act of 1974,

42 U.S.C. § 5672 ....................................

The Age Discrimination Act,

42 U.S.C.A. §6101 (1975) ............................

Public Works Employment Act,

42 U.S.C. §6727 ....................................

Energy Conservation and Resource Renewal Act of 1976,

42 U.S.C. § 6870 ....................................

Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act

of 1976, 45 U.S.C. §803 ............................

passim

passim

Page

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD

100 Cong. Rec. 8979 .

109 Cong. Rec. 1161 .

110 Cong. Rec. 2467 .

110 Cong. Rec. 2469 .

110 Cong. Rec. 5251 .

110 Cong. Rec. 5612 .

110 Cong. Rec.. 5863 .

110 Cong. REc. 6052 .

110 Cong. Rec. 6543 .

110 Cong. Rec. 6544 .

110 Cong. Rec. 6546 .

110 Cong. Rec. 6561 .

110 Cong. Rec. 6566 .

110 Cong. Rec. 7055 .

110 Cong. Rec. 7058 .

110 Cong. Rec. 7064-65

110 Cong. Rec. 7101 .

FEDERAL REGULATIONS

31 C.F.R. § 51.52 . . .

45 C.F.R. § 80.3(b)(1)

45 C.F.R. § 80.3 (b)(2)

45 C.F.R. § 80.3 (b) (3)

45 C.F.R. § 90.12 . . .

45 C.F.R. § 1232.4 . .

FEDERAL REGISTER

29 Fed. Reg. 16274-16305 .................

38 Fed. Reg. 17920-17997 .................

42 Fed. Reg. 18365, April 16, 1977 . . . .

44 Fed. Reg. 31018, May 30, 1979 . . . .

44 Fed. Reg. 33776, March 12, 1979 . . . .

MISCELLANEOUS

90 HARV.L.REV. 1, 28-29 (1976) ...........

The New York Times, May 19, 1980 editorial

The Washington Post, May 24, 1980, A15

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

No. 80-7041

DAVID E. BRYAN, JR., et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

V.

EDWARD I. KOCH, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

DISTRICT COUNCIL 37, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

V.

EDWARD I. KOCH, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District

Court For The Southern District Of New York

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

Statement of the Issues

Presented on Appeal

1. Do the decisions of the Supreme Court and this Circuit

and the regulations of HEW that require a showing of disparate

impact, but not intentional discrimination, to establish a

prima facie violation of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, remain in force?

2. Did the district court err in basing its conclusion

that the minority patient population would receive guaranteed

care at other hospitals if Sydenham closed on a hypothetical

construct which provided no assurances that other hospitals

had the physical capacity or financial ability to accept

Sydenham patients?

3. Where the applicable regulations of HEW provide that

action which has an adverse disparate impact on minorities is

a violation of Title VI and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 if

feasible and less onerous alternatives are available, did the

district court err in concluding that plaintiffs did not estab

lish a Title VI violation under the "impact" standard where it

failed to make findings on the availability of feasible alterna

tives to closing Sydenham Hospital?

Statement of the Case

This brief is submitted by plaintiffs-appellants in Bryan

v. Koch, 79 Civ. 4274, and District Council 37 v. Koch, 79

Civ. 4329 ("plaintiffs") in support of their appeal from the

2

deanial of their motion for a preliminary injunction enjoining

the closing of Sydenham Hospital pendente lite, or, alterna

tively, until City defendants provide adequate assurances that

the black population served by Sydenham will have alternate

access to health services. By order and opinion dated May 15,

1980, the district court denied plaintiffs relief, but granted

a stay to allow plaintiffs to pursue an injunction pending

appeal.

On May 20, 1980, after hearing oral argument, the court

of appeals (per Judges Oakes and Meskell and Judge Bonsai,

D.J.) issued an order granting a stay of the closure of Sydenham

until May 30, 1980, when this Court will hear oral argument.

Subsequent to the issuance of that order, the district court on

May 23, 1980, issued an amended opinion with substantial revi

sions. All references to the "opinion" herein are to the

amended opinion unless otherwise indicated.

Plaintiffs request that the order staying the closing of

Sydenham Hospital continue until this Court determines the

merits of their appeal.

3

A. The Parties

These consolidated actions, Bryan v. Koch and District

Council 37 v. Koch, were instituted by black and Hispanic resi

dents of New York City and by District Council 37, AFSCME,

AFL-CIO, on behalf of its black and Hispanic members- Bryan v .

Koch is a class action on behalf of poor and low-income black

and Hispanic residents of New York City who depend on the muni

cipal hospital system for their health care. The district court

indicated its intention to certify the class. Opinion, fn.

(App. p. ).

Defendants-appellees are the City of New York and the New

York City Health and Hospitals Corporation, the public agency

which operates the municipal hospital system, and certain of

their officials (hereafter collectively "City defendants"). In

addition, the Bryan case joined as defendants the State of New

York, its Department of Health and two of its officials. Bryan

also joined the U. S. Department of Health, Education and

Welfare (HEW) as an interested party defendant but asserted no

claim against it. HEW recently was renamed the Department of

Health and Human Services. Neither the state defendants nor

HEW are appellees on this appeal from denial of a preliminary

injunction sought only against City defendants. HEW is a party

4

to an appeal in a related case, Boyd v. Koch, to be argued

following this appeal. The district court consolidated the

Boyd case with the Bryan and District Council 37 cases on its

own motion. Opinion p. (App. p. ).

B . Proceedings Below

On June 28, 1979, City defendants gave final approval to a

plan to close two municipal hospitals in Harlem (Sydenham and

Metropolitan) and reduce beds in two other municipal hospitals

(Kings and Queens). In August, 1979, these actions were insti

tuted to enjoin the implementation of the plan.

The complaints allege that the hospital closings would vio

late the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause and Title

VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d and the

regulations thereunder, 45 C.F.R. Part 80. Other claims, not

pertinent to this appeal, are asserted in the Bryan case relating

to application of federal and state health planning laws to the

hospital closings.

In October, 1979, plaintiffs moved for a preliminary injunc

tion to restrain the closing of Metropolitan Hospital. After

affidavits and memoranda were filed and argument held, the dis

trict court declined to proceed with an evidentiary hearing

because City defendants represented they had not yet made a final

decision to close Metropolitan.

On January 25, 1980, City defendants gave the State

5

Commissioner of Health ninety days notice of intention to close

Sydenham Hospital, as required by State regulations, 10 NYCRR

V§401.3 (f). Plaintiffs promptly moved for a preliminary injunc

tion against City defendants only, to restrain the closing of the

hospital pendente lite or at least until adequate assurances of

access to in-patient and emergency care for the minority popula-

tion served by Sydenham is demonstrated to the satisfaction of

the district court.

Following an evidentiary hearing, the district court denied

the preliminary injunction. Contrary to existing precedent, see

infra pp. / i t is determined that the anti-discrimination pro

visions of Title VI required a showing of racial animus, the same

intentional discrimination needed to establish a violation of the

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In so doing,

it invalidated long-standing regulations of HEW which required

only a finding of disparate impact to establish a prima facie case

of discrimination under Title VI. Under the regulations, a find

ing of adverse disparate impact then requires a determination of

justification and the feasibility of less onerous alternatives.

See infra pp.

Plaintiffs introduced substantial evidence from which racial

animus could be inferred, but the district court found in favor of

defendants on the point. In deference to the applicatipn of the

^_/ The State subsequently granted approval.

- 6 -

"clearly erroneous" standard to the lower court's finding on

intentional discrimination, plaintiffs do not pursue this matter

on appeal. Rather, plaintiffs assert that intent was not a

requirement for establishing a violation of Title VI, that under

the disparate effect standard a substantive likelihood of success

on the merits of their Title VI claim has been established, and

the other requirements for a preliminary injunction have been

met. Accordingly, the district court erred in denying the pre

liminary injunction.

The opinion of the district court was devoted almost exclu

sively to the legal question of whether a showing of intent was

required and an examination of whether the facts established sub

jective racial animus on the part of City defendants. Only one

page of the Opinion, pp. 46-47, touches on the application of the

disparate impact standard to the case.

In the district court, HEW at first presented legal memoranda

to the court supporting the legal position of plaintiffs on the

appropriate standard under Title VI but took no position on the

facts. At the conclusion of the hearing, HEW advised the court

that it had determined that there was sufficient evidence of a

violation of Title VI developed by the hearing and its own inves

tigation to warrant the granting of the preliminary injunction

sought by plaintiffs herein. HEW letter, May 14, 1980, App. p.

Since January 1978, HEW had been investigating a complaint

by plaintiff Bryan on behalf of the Metropolitan Council of

7

Branches of the NAACP that the closing of Sydenham ai

actions of City defendants affecting the municipal ho

violate Title VI. The investigation is still continui— -); HEW

has asserted to the district court that the lack of cooperation

and unwarranted delays by City defendants are the causes of the

failure to complete the investigation. Id.

C. Statement of the Facts

The City of New York operates a municipal hospital system

consisting of thirteen acute care hospitals and four long termycare facilities for thp chronologically ill. These hospitals'■"V-

j*/ • The district court statement (Opinion p. 1, App. p.

that New York City operates 17 of the 27 municipal hospitals

in the country is grossly misleading. There are 1,900 public^

hospitals run by local government but most are run by counties

rather than cities, a meaningless distinction. For example,

major public institutions such as Cook County Hospital and Los

Angeles County Hospital are municipal hospitals operated by

county government. The opinion is also misleading by describing

the budget of the City's municipal hospitals as 10% of the

expense budget of the City, i<3., without noting that 75% of

the hospital budget is covered by third part reimbursement, e.g.

Blue Cross, Medicare and Medicaid. Similarly, the reference to

$500,000,000 in tax "subsidies," idL , ignores the fact that

approximately half that amount the City'£>ays" to itself for which

it receives almost three times as much in federal and state

matching funds, under the Medicaid program. Further, the

City's share of Medicaid payments would be equal or greater if

the Medicaid patients were treated in private hospitals.

8

are the major source of in-patient, emergency room and out

patient care for a predominately black and Hispanic population

which is poor or low income in New York City. Two-thirds of

the in-patients in the municipal hospitals are black and

Hispanic, as compared with one-third in all of the hospitals,

public and private, in the City.

On June 20, 1979, a Task Force appointed by Mayor Koch

two months earlier issued a report, Ex. A, App. pp.

recommended closure of two of the three municipal hos

pitals in the Harlem communities, Sydenham in Central Harlem

and Metropolitan in East Harlem. It also recommended reduction

of beds in two other municipal hospitals, Kings County Hospital

and Queens Hospitals and the replacement of two municipal hos

pitals in Brooklyn, Greenpoint and Cumberland, with a newly

built but as yet unopened municipal hospital, Woodhull. The

choice of only hospitals located in Harlem to be closed led to

the filing of these lawsuits. Sydenham has virtually 100%

minority patients. Under the latest available figures,

Metropolitan is approximately 80% black and Hispanic (Ex. 57,

App. pp. ).

The Mayor's Plan or Task Force Report, as the June 20

report came to be called, was rammed through the Board of

Directors of the defendant Health and Hospital Corporation in

9

only eight days, with little opportunity for discussion by

board members, let alone the public.

The Mayor's Plan was premised on the notion that there

existed excess acute care hospital beds in New York City and

that closing beds would save the City money. However, two

other official agencies, the New York City Health Systems

Agency (HSA) and the City's Legislative Office of Budget Review

reviewed the data and concluded that the number of excess beds

were insignificant. Ex. 39a, p. 3; Ex. 44a, pp. 20-21. The

HSA, utilizing much more sophisticated methodology than the

Mayor's Plan, found that whatever excess beds existed did not

justify closing hospitals, with few exceptions (Ex. 39a, p. 3).

Whatever the facts as to the City as a whole, the City

defendants themselves have documented that there are no excess

beds in the Northern Manhattan area serving Harlem, the rele

vant area to Sydenham and Metropolitan Hospitals. See the

defendants' proposal, "The Health Care Financing Experiment for

Harlem,"Ex. 76, pp. 22, 24, 51, 65-71, App. pp. . Since

1978, 834 beds have been closed in Northern Manhattan, including

the closure of two complete voluntary hospitals, Logan and

Flower Fifth Avenue. In 1975, Delafield, a municipal hospital

in Northern Manhattan was closed. In the City as a whole, since

1976, twenty-eight hospitals have closed and 5,000 beds taken

10

out of the system. (Aff. Dr. Pomrinse, President, Greater

N.Y. Hospital Ass'n.)

In addition, further evidence of the need for all remain

ing hospital beds serving Harlem was shown by the fact, found

by the district court, that most of the hospitals serving

Harlem are now at or near operational capacity. Opinion, fn.

14, App. p .

The proposal to close two of the three municipal hospitals

in Harlem must be assessed in light of fact, acknowledged by

City defendants, that Harlem is both the sickest and most

medically underserved area in the City, and perhaps the nation.

Ex. 76. It is also one of the poorest. As defendants' own

computations show, Harlem, and particularly the areas within

Harlem served by Sydenham, have the highest rates of morbidity

and mortality on almost every test employed by health planning

experts. Ex. 76, pp. 35-46. In addition to disease and sick

ness, the poverty of the area breeds a plague of crime, drug

addiction and alcoholism which is reflected in Sydenham's

patients. They create special needs for immediate emergency

and in-patient services without delay, and they greatly reduce

the mobility of the patient population. Like most hospitals,

many of the emergency room visits are not true emergencies,

but as the district court found (Opinion p. , App. p.

11

at least 5% of the cases, 1,300 people annual'

life threatening situations where a few mini-

difference between life and death. Most of these v.

or are carried into the Sydenham emergency room from the irtiu.

diate vicinity. A total of 3,900 cases annually are rated

V

emergent, requiring care without undue delay.

The unusual nature of the patient population is also shown

by the fact that 75 percent of the in-patients are admitted

through the emergency room. In addition to the victims of

crime and drugs, many Harlem residents lack access to regular

out-patient care and so end up with serious conditions that

create emergencies and require hospitalization that might other—

wis e be avoided.

Sydenham Hospital is a relatively small institution but one

which plays a vital role in the community it serves. Despite

chronic understaffing and insufficient funding imposed by City

defendants, and an older building, Sydenham received the highest

rating in its latest survey by the Joint Commission on Hospital

Accreditation, the national agency charged with rating the *

* y Sydenham served 3,757 in-patients in 1979 for a total of

35,000 patient days, Adams affidavit. Its emergency room pro

vided 26,000 visits in 1979. Ex. EEE.

12

functioning and quality of hospitals throughout the country.

Plaintiffs' testimony as to quality of care corroborated the

Joint Commission on Hospital Accreditation. Defendants

attempt to introduce evidence of poor quality, through its

own officialC!resulted in most of the testimony being stricken

f

and the court below made no finding on the quality of in-patient

care. Its finding that the emergency room had limited capacity

to treat life threatening emergencies was shown by City defend

ants' own exhibit to the affidavit of Bradley Sachs to be the

result of imposed staff shortages.

City defendants sought to justify closing Sydenham because

it would save some money. The Mayor's Plan estimated saving

3.2 million dollars, but by trial this claim had inflated to

nine million dollars. Plaintiffs' expert testified that

savings would amount to approximately two million dollars, but

that substantially greater savings could be achieved in a

number of ways, including mergers of Sydenham and Harlem and

of Metropolitan and Lincoln, retaining all facilities but

regionalizing specialties and increasing Medicaid reimburse

ment. City defendants offered no evidence that they had con

sidered these alternatives or sought alternatives themselves

which could achieve the goal of fiscal savings without a

13

on the black and Hispanicdevastating and

population of Harlhscu The court Taelow found that closing

Sydenham was a reasonable, method of saving money but made insuf

ficient findings as to the aA^ilabili^y of less onerous

alternatives. The court also foumT thab s people served

at Sydenham, such as ictims of crime, w suffhr if the

hospital closed (meaning that some would ) but' described

these numbers as small.. Opinion p. , App.

14

I. A SHOWING OF DISPARATE IMPACT ESTABLISHES

A PRIMA FACIE VIOLATION OF TITLE VI UNDER

JUDICIAL PRECEDENT, STATUTORY HISTORY AND

UNIFORM ADMINISTRATIVE INTERPRETATION. THE

DISTRICT COURT'S IMPOSITION OF AN INTENTIONAL

DISCRIMINATION REQUIREMENT INTO TITLE VI

WOULD CRIPPLE ITS REMEDIAL PURPOSE TO PREVENT

RACIAL DISCRIMINATION

This Court has stated unambiguously that "Title VI findings

of discrimination may be predicated on disparate impact without

proof of unlawful intent." Board of Education v. Califano,

584 F .2d 576, 589 (2d Cir. 1978), aff'd on other grounds sub

nom Board of Education v. Harris, ___U.S. ___, 62 L.Ed.2d 275

(1979). The Supreme Court has expressly found a violation of

Title VI "even though no purposeful design is present," Lau v.

Nichols, 414 U.S. 563, 568 (1974). The determination that a

prima facie violation of Title VI requires only a showing of dis

parate impact on minorities is consistent with, indeed required by

the statutory history and the uniform federal administrative inter

pretations over fifteen years. Once a disparate adverse impact

is shown, the burden shifts to the recipient of federal funds

"to establish that (1) the closings are nec

essary to achieve legitimate objectives un

related to race, color or national origin;

and (2) these objectives cannot be achieved

by other measures which have a less dispro

portionate adverse effect." ]_/

1_/ Supplemental Memorandum of HEW in the District Court, p. 5,

cited in the Opinion below, p. 44. The standard was applied for

hospital closures and relocations in the July 5, 1977 OCR-HEW

Letter of Findings issued to Wilmington Medical Center, pp. 6-7,

annexed to the Motion for a preliminary injunction as to Metro

politan Hospital as Exhibit F and the June 29, 1978 OCR-HEW

Letter of Findings to Indiana State Department of Health, annexed

to the motion as Exhibit I, both of which were incorporated into

the present motion concerning Sydenham Hospital.

15

(See in fra p p . _____ ). That determination is necessary if Title

VI is to serve serious broad remedial purpose of protecting

minorities. The court below for the first time finds otherwise

and does so by predicting that Lau might one day be overruled.

A. The Disparate Impact Standard Has Been Upheld by

the Courts

The disparate impact standard embodied in Title VI and its

regulations have been repeatedly upheld by the courts. In Lau

v. Nichols, supra, the Court explicitly relied upon HEW's disparate

impact regulation to hold unanimously that a school system's

failure to provide bilingual or remedial English instruction to

non-English speaking students violated Title VI even though no

purposeful design was present. Id_. This Court and every court

that has previously ruled on the issue has upheld the disparate

impact standard. See, e.g., Board of Education v. Califano,

2/ Parent Ass'n of Andrew Jackson High v. Ambach, 598 F .2d

705 (2d Cir. 1979) is not to the contrary. That case involved the

limitation imposed by Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000c-6, in the context of whether the extraordinary remedy of

school busing was available under a Title VI action. This Court

held "that Title VI does not authorize federal judges to impose a

school desegregation remedy where there is no constitutional trans

gression ... Having denied the Attorney General and the federal

judiciary any authority to correct de facto imbalances under Title VI, it would have been illogical for Congress to grant

broader power to private plaintiffs in the same courts. We must

conclude, therefore, that even if there is a private right

of action to desegregate schools under Title VI, an affirmative

judicial desegregation order without a showing of de jure dis

crimination would not be authorized." 598 F .2d at 715 and 716.

See discussion of the legislative history, infra, pp. ___ ).

16

supra; Serna v. Portales Municipal Schools, 499 F .2d 1147, 1154

(10th Cir. 1974); Shannon v. U.S. Dept, of Housing and Urban

Development, 436 F .2d 809, 816-817, 820 (3d Cir. 1970); Guardians

Association v. Civil Service Commission, 466 F. Supp. 1273 (S.D.

NY. 1979); Lora v. Board of Education, 456 F. Supp. 1211, 1277-78

(E.D. N.Y. 1978); Child v. Beame, 425 F. Supp. 194, 199 (S.D. N.Y.

1977); Johnson v. City of Arcadia, 450 F. Supp. 1363, 1379 (M.D.

Fla. 1978).

At least three courts have also upheld a Title VI regulation

issued by the Department of Housing and Urban Development based on

a disparate impact principle. Shannon v. HUD, supra; Johnson v.

City of Arcadia, supra; Hicks v. Weaver, 302 F. Supp. 619 (E.D. La.

1969); Blackshear Residents Organization v. Housing Authority of

City of Austin, 347 F. Supp. 1138, 1146 (W.D. Tex. 1971).

In addition, the Second , Third, Seventh and Eighth Circuits

have all held that practices having a disparate impact upon

minorities violate Title VIII of the Fair Housing Act, regardless

of whether there is a showing of discriminatory intent. Robinson

v. 12 Lofts Realty, Inc., 610 F .2d 1032 (2d Cir. 1979); Resident

Advisory Board v. Rizzo, 564 F .2d 126, 146-147 (3d Cir. 1977);

Metropolitan Housing Development Corporation v. Village of

Arlington Heights, 558 F .2d 1283, 1288-1290 (7th Cir. 1977);

United States v. City of Black Jack, 508 F .2d 1179, 1184-1185

(8th Cir. 1974).

Similarly in employment discrimination cases brought under

Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e

17

e_t seq. , the courts have held that employment requirements

having a disparate impact on minorities are illegal, despite

the absence of discriminatory intent, unless the employer can show

that requirements are a business necessity. See, e.g., Griggs

v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971); Albemarle Paper Co.

v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975); Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S.

321 (1977). In his opinion in Regents of the University of Califor

nia v. Bakke, Justice Stevens, writing for himself and three other

Justices, expressly analogized the policy behind Title VII to that

underlying Title VI 438 U.S. 265, 416, n.19 (1978).

B. The Disparate Impact Standard Approved In Lau

Has Not Been Overruled, Is Binding And Is Correct

Although the district court acknowledged that Lau v. Nichols,

suPra upheld the HEW Title VI regulation establishing an "effect"

standard, opinion, p. 27, it went on to predict that the Supreme

Court would ultimately overrule Lau. In so doing, the District

Court violated its duty to adhere to decisions of higher courts

until overruled. U.S. v. Chase, 281 F .2d 225, 230 (7th Cir. 1960).

Further, its prediction was tinged with speculation.

Only three members of the Supreme Court (Justices Stewart,

Powell and Rehnquist) have expressed a view on the applicability

of the intent requirement of Title VI in a case involving discrimi

natory effects of facially neutral decisionmaking. Board of Educa

tion v. Harris, supra, 62 L.Ed.2d at 291 (dissenting opinion).

The district court erred in adding to the ranks of these three

Harris dissenters, Justice Brennan and the three Justices who

joined his opinion in Bakke. In so doing, it contradicted this

18

Court's statement in Parent Ass'n of Andrew Jackson High School

v. Ambach, 598 F . 2d 705, 716 (2d Cir. 1979), that "Lau was not

expressly overruled in Bakke."

It is speculative at best whether those four Justices would

agree with the Harris dissenters in a case of the nature now before

this Court. Although Justice Brennan's opinion in Bakke contains

language equating the Title VI standard with the intent re

quired in equal protection cases, it does so in the context of

the use of explicit racial criteria which favor the admission of

minority medical students. Justices Brennan, White, Marshall and

Blackmun argued that the Equal Protection Clause did not outlaw

such a preferential racial classification to assist minorities.

Therefore, they concluded that Title VI, as a remedial statute

"designed to eliminate discrimination against racial minorities,"

should not be construed "in a manner which would impede efforts to

obtain this objective" (438 U.S. at 355). Having concluded that

the Constitution did not prohibit race—conscious remedies for

societal discrimination, they argued that Congress did not intend

Title VI to prevent such remedial programs either. The disparate

impact issue was not before the Justices in Bakke and the opinion

never considers whether a showing of intent is always necessary

to establish a prima facie violation of Title VI where the

legality of intentional racial classifications is not at issue.

Indeed, immediately after the reference to Lau, Justice Brennan

emphasized and relied upon the Court's prior holdings under

"statutes containing nondiscrimination provisions similar to that

contained in Title VI" that a showing of disparate impact was

19

sufficient to establish discrimination even if the policies

resulting in that impact were racially colorblind. 438 U.S. at

353.

Justice Brennan also recognized that Title VI regulations

are entitled to considerable deference when construing the

statute. at 342.

It is also important to note that in Justice

Stevens' concurring opinion he states:

it seems clear that the proponents of Title

VI assumed that the Constitution itself required

a colorblind standard on the part of government,

but that does not mean that the legislation only

codifies an existing constitutional prohibition.

The statutory prohibition against discrimination

in federally funded projects contained in § 601

is more than a simple paraphrasing of what the

Fifth or Fourteenth Amendment would require.

Id. at 416.

This Court considered the impact of the Bakke decision and

reaffirmed the vitality of the disparate impact rule under Title

VI in Board of Education v. Califano, supra, 584 F .2d at 588-589

Accord, Guadalupe Organization v. Tempe Elementary School District,

587 F .2d 1022, 1029 & n.7 (9th Cir. 1978); De La Cruz v. Tormey,

582 F .2d 45, 61 & n.16 (9th Cir. 1978); Guardians Assoc, v. Civil

Service Commission, supra, 466 F. Supp. at 1285-1287.

Board of Education v. Harris, supra, was decided not under

Title VI but under the Emergency School Aid Act (ESAA). While

this Court had considered the status of the disparate impact rule

under Title VI highly relevant to its decision regarding ESAA, the

20

Supreme Court found no necessity to decide the Title VI issue and

it therefore explicitly declined to reach the Title VI issue. Id.

Turning its attention directly to ESAA, the court applied the rule

that remedial statutes should not be construed in ways which

impede the accomplishment of their broad objectives. Because the

purpose of ESAA was to remedy segregation of minorities, the Court

held that its prohibitions focused on "actual effect, not on

discrimination on consequences, not on intent. Id. 62 L.Ed.2d at

285. The one sentence in the opinion upon which defendants place

such heavy reliance was essentially an argument that even if Title

VI requires a showing of intentional discrimination, that standard

would be inapplicable to ESAA.

The Court's comment that it is likely Title VI might require

a more stringent showing was explicitly based on an assumption that

Title VI unlike ESAA, would require a "drastic" cutoff of all

federal funds, rather than merely those funds associated with a

particular kind of assistance program. Id_. at 290. This erroneous 3_/

assumption provides a forceful reminder that while "the

question actually before the court is investigated with care

... other principles which may serve to illustrate it are consider

ed in their relation to the case decided, but their possible

3/ It is apparent that none of the parties had called to the

Court's attention the requirement of 42 U.S.C. § 2000d-1(1) that

fund termination "be limited in its effect to a particular program,

or part thereof, in which such non-compliance has been so found..."

Senator Humphrey explicitly stated that this section was intended

to make clear that cutoffs "should be pinpointed .. to the situa

tion where discriminatory practices prevail...." 100 Cong. Rec.

21

bearing on all other cases is seldom completely investigated"

Cohen v. Virginia, 6 Wheaton 264, 399-400 (1821).

Moreover, it is apparent that the dicta focuses on the stan

dard required to justify use of fund termination, a remedy the

majority found exceptionally harsh. The court did not consider

even in dicta the appropriate standard where, as here, plain

tiffs seek only injunctive relief under 42 U.S.C. § 2000d-1(2).

Justice Steven emphasized this difference in his opinion

in Bakke, 438 U.S. at 419 and n.26. The difference is dramatically

illustrated in this case by the difference between a cut-off of

Medicaid and Medicare funds, which would cost the City close to two

hundred million dollars annually, and the savings of approximately

three million dollars which the City projected in making its

decision to close Sydenham. (May 15th opinion, p. 16.).

In short, while there is dicta in both Bakke and Harris, it

is clear that the Court has not overruled Lau. Accordingly Lau

remains the controling precedent. A district court is bound

to follow a decision of its own court of appeals or the Supreme

Court, unless there is a clear majority opinion of the appellate

court holding otherwise on the very question in issue. Neither

propositions advanced in concurring opinions, nor dicta, may

properly be followed by a district court in the face of a control

ling opinion. See, e.g. , U.S. ex rel. Gockley v. Myers, 450 F .2d

232 (3rd Cir. 1971); Oppen v. Aetna Insurance Co., 485 F .2d 252

(9th Cir. 1973); U.S. v. Chase, supra; U.S. v. Barbera, 514 F .2d

294, 300 (2nd Cir. 1975); St. Louis-San Francisco Ry. Co. v.

Willard Mirror Co., 160 F. Supp. 895, 899, 900 (W.D. Ark., 1958).

22

Indeed, this would be true even if it were extremely doubtful that

the earlier position would be followed by the Supreme Court when

it reconsiders the issue (U.S. v. Chase. 281 F .2d at 230). it is

the function of the appellate court, not the district court to

overrule an appellate decision. The district court violated this

proposition so basic to the orderly process of judicial decision

making. A careful review of the purpose, legislative history and

administrative interpretation demonstrates that the interpretation

of Title VI in Lau is correct.

C. The Legislative History of Title VI Support

the Disparate Impact Standard

1. Any rule requiring proof of intentional

discrimination to establish a violation

of title VI would be inconsistent with

the remedial purposes of the act.

President Kennedy's June 19, 1963 message to

Congress proposing the legislation which ultimately became the

1964 Civil Rights Act, declared:

Simple justice requires that public funds, to which

all taxpayers of all races contribute, not be spent

in any fashion which encourages, entrenches, sub

sidizes or results in racial discrimination.

109 Cong. Rec. 1161 (emphasis added).

The legislative history of the Civil Rights Act of 1 964 indi

cates that Congress contemplated a discriminatory impact standard

would be applied in cases brought under Title VI and supports the

standard enunciated in Califano and Lau. The proponents of the

Civil Rights bill asserted that Title VI was, and should be, its

23

4/

strongest and most far-reaching provision, effectuate

5/

broad non-discrimination principle" in order to remove "a* *.̂

jv

vestige of discrimination from federally-funded activities."

In enacting Title VI, Congress relied on its power to attach

reasonable conditions to a grant of federal funds not on the

7/

implementing clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Lau v.

Nichols, 414 U.S. at 569. It is clear that those conditions can

afford greater protection than is embodied in the constitution.

Steward Machine Co. v. Davis, 301 U.S. 548 (1937). In the eyes of

its supporters, it was the source of these funds — the taxpayers,

black and white — which mandated that Title VI be the strongest

part of the bill. Thus President Kennedy and Senator Humphrey

both stressed that Title VI prohibited actions which result in

discrimination, 110 Cong. Rec. 6543. Similarly, Senator Kuchel

focused not on motivation but on distribution of benefits,

emphasizing:

The taxes which support these programs are collected

from all citizens regardless of their race. It is

simple justice that all citizens should derive equal

bene fits from these programs without regard to the

color of their skin.

4/ "This is a strong bill and this is the strongest provision in

the bill." 110 CONG. REC. 2469 (9164) (remarks of Rep. Libonati).

5/ Id_. at 7058 (remarks of Sen. Pastore) ; JEd. at 6544 ("a broad

principle that is right and necessary") (remarks of Sen. Humphrey).

See id. at 7064-65 (remarks of Sen. Ribicoff.).

*

6/ 110 CONG. REC. 6561 (remarks of Senator Kuchel, referring to

promises of the 1960 Republican platform which Title VI would carry

out) .

7/ 110 CONG. REC. 2467 (9164) (remarks of Rep. Celler, Chairman

of the House Judiciary Committee, citing U.S. v. San Francisco, 310

U.S. 16 (1940), and Oklahoma v. Civil Service Commission, J30 U.S.

127 (1947).

24

Id. at 6561 (emphasis added) (remarks of Sen. Kuchel, in the

process of making a comprehensive presentation of the Civil Rights

Act to the Senate, jointly with Senator Humphrey).

Title VI, in effect, provides that the taxes paid

to the Federal Government by all Americans shall

be used to assist all Americans on an equal basis.

110 Cong. Red. 6566 (9164). (Memorandum prepared by the

Republican membership of the House Committee on the Judiciary).

Indeed, in describing discrimination in the federally-funded

8/

school lunch program, Senator Pastore explained:

I am not talking now about the fact that the program is

administered in segregated schools. That is a different

issue. I am talking about situations such as that in

Greenwood Separate School District of Mississippi, where

during the years 1960-62 Negro children, who make up half

the average daily attendance in Greenwood schools, re

ceive only one fifth of the free lunches served.9/

Id. at 7055.

The language of the statute itself supports a broad disparate

1 0/

impact construction, since it speaks of the participation in

and the receipts of benefits from federally funded programs.

8/ Sen. Pastore was one of two bipartisan captains whose job it

was to explain Title VI. His comments cited there were praised

as constituting an "outstandingly able and valuable contribution

to the legislative history of this title ." 11 CONG. REC. 7064

(9164) (remarks of Sen. Boggs); see, similarly, id. at 7064

(remarks of Senators Hart, Ribicoff and Pell).

9/ See, similarly, _ic3. at 7101 (remarks of Sen. Javits).

12/ The Supreme Court has repeatedly held— and indeed reaffirmed as

recently as last month — that statutory language prohibiting

discrimination "because of" of "on the ground of", or "on account

of" race contains no hint that a showing of intention is required.

See, e.g., Griggs v. Duke Power Co., supra; City of Rome v.

United States, No. 78—1840 (U.S. Supreme Court slip opinion,

April 22, 1980), pp. 14-15).

25

2. Sponsors of title VI refused to limit its

scope to the equal protection standard.

The sponsors of Title VI refused to limit Title Vi's prohibi

tions to the vagaries of future constitutinal interpretation.

Much of the opposition to Title VI focused upon its failure

to define the word "discrimination." 110 Cong. Rec. 5863. See

also, 110 Cong. Rec. 6052 (Sen. Johnston); _ic3. at 5612 (Sen.

Ervin); rd. at 5251 (Sen. Talmadge).

Despite the criticism, supporters of Title VI refused

to include a more explicit statement of what Title VI prohibited.

Had they wanted its provisions to be coextensive with those

of the Constitution, they could have prohibited simply those

actions by recipients of federal funding which, if taken by a

state, would have violated the Equal Protection Clause. Instead,

they thought it "wise to leave the (executive) agencies a good

deal of discretion as to how they (would) act." (110 Cong. Rec.

6546 (Sen. Humphrey).

Congress knew full well how to require constitutional stan

dards in the Civil Rights Act for it incorporated constitutional

reference into both Titles III and IV but declined to do so

in Title VI. One year later Congress again incorporated a con-11/

stitutional standard into § 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

1_1 / The legislative history of § 2 of the Voting Rights Act of

i~9l>5, as set forth in the recent Supreme Court opinion in City

of Mobile v. Bolden, ___ U.S. ___, 48 U.S.L.W. 4436, 4437

(April 22, 1980) is markedly different from that of Title V. As

the court noted,

26

At the time Title VI was enacted, school busing had already

come to be regarded as an extraoridnary remedy which should only

be used in cases of intentional discrimination. Busing opponents

were concerned that Title VI would permit the courts or agencies

to require busing in cases of de facto segregation even if the

Supreme Court ultimately decided tht the Constitution did not

require busing under those circumstances. Accordingly, they

sought language which would make clear that Title VI did not

authorize busing to achieve racial balance or in any way enlarge

whatever the Supreme Court might ultimately decide was the consti

tutional authority to require busing. A compromise was reached

under which Title VI itself was not altered. Title IV, however,

was changed to include the explicit limitation codified at 42

U.S.C. § 2000c-6:

tP]rovided that nothing herein shall empower any

official or court of the United States to issue

any order seeking to achieve a racial balance in

any school by requiring the transportation of

pupils or students from one school to another or

one school district to another in order to achieve

such racial balance, or otherwise enlarge the

existing power of the court to insure compliance with constitutional standards.

In addition, Title III of the 1964 Act, 42 U.S.C. § 2000(b)

(2) (a), expressly refers to the deprivation of the "equal protec-

11/ cont'd.

"[t]he view that this section simply restated the pro

hibitions already contained in the Fifteenth Amendment

was expressed without contradiction during the Senate

hearings. Attorney Gneral Katzenbach agreed with

Senator Dirksen that the section was "almost a re

phrasing of the 15th [A]mendment." Id.

27

tion of the laws." In contrast, when Senator Ervin introduced

legislation in 1966 which would have amendecyTitle VI to explictly

require a showing of intent was defeated . l a the Houe and never

r oajJLpemerged from committee in the Senate 111(0 Cong. Rec. 1 0061 ,

18701 , 1 8715 ( 1966). The statutory history demonstrates that JJlV'

Congress was well aware that the broad sweep of Title VI would

not automatically be limited by the constitutional definition of

discrimination, let alone by the "floating" definition suggested

by the district court. In cases where Congress wanted to impose

constitutional limitations it did so explicitly.

3. Congress enacted Title VI at a time when

the equal protection clause was believed to

prohibit actions having a discriminatory

impact.

As the Supreme Court stated in Cannon v. University of

Chicago, ___ U.S. ___, 99 S. Ct. 1946, 1957-58 (1979), Congress

must have presumed to have intended that its acts be interpreted

in conformity with then existing precedents. See also, Regents

of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 416

n.18 (Stevens, J. , concurring and dissenting). The Court stated

in Moor v. County of Alameda, 411 U.S. 693, 709 (1973), "... we

must construe the statute in light of the impressions under which

Congress did in fact act."

Although it is now established that intentional discrimination

is required to prove a violation of the Constitution, the case law

in 1964 did not reflect that requirement.

28

In Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940), an equal protection

case, the Court stated that"[i]f there has been discrimination,

whether accomplished ingeniously or ingenuously, the conviction

cannot stand." Id_. at 132. And in Hill v. Texas, 316 U.S. 400

(1942), another equal protection case, the Court used language,

now paralleled in the Title VI regulations, see 45 C.F.R. § 80.3-

(b)(2) that the state may not "pursue a course of conduct in the ad

ministration of their office which would operate to discriminate in

the selection of jurors on racial grounds." Id_. at 404. Indeed,

in 1964 discrimination was still practiced in such blatant forms

that the idea of a requirement of intent was simply not presented

to the courts in those days. In 1961, the Supreme Court in

Monroe v. Pape, 364 U.S. 167, discarded the rule that a showing

of intent was necessary to establish a violation of the 14th

Amendment in a § 1983 damage action. Although this latter case

involved Fourth Amendment violations, no distinction from the

Equal Protection Clause violations in § 1983 actions was then

perce i ved.

Thus, even assuming arguendo that Title VI supporters had

believed that Title VI was co-extensive with the scope of the

Equal Protection Clause as it was then understood, they would

not have assumed that intentional discrimination was required to

establish a violation.

29

4. Regulations issued by seven Federal agencies

within months of the Act's passage and again in

1973 indicate their unanimous view that Title

VI prohibited conduct which had a disparate

impact upon minorities.

On December 4, 1964, just five months after final passage of

the Civil Rights Act, seven Federal agencies issued regulations,

approved by the President pursuant to 42 U.S.C § 2000d-1, constru

ing the statute (29 Fed. Reg. 16274-16305). All seven agencies

included in their regulations a provision identical to HEW's

broad disparate impact regulation, 45 CFR § 80.3(b)(2). Although

the issuance of Title VI regulations by seven agencies on a

single day so soon after the Act's passage can hardly have

slipped by Congress unnoticed, yet there is no indication in the

Congressional record for that period that any of the legislators

who voted for Title VI felt the disparate impact regulations

exceeded the scope of Congressional intent.

Eight years later, on July 5, 1973, every federal agency

published amendments to its Title VI regulations (38 Fed. Reg.

17920-17997).. One of the principal purposes for these amendments

was to ensure that each agency had a provision similar to 45

C.F.R. § 80.3(b)(3) prohibiting decisions on location of facili

ties which had a disparate impact upon minorities. Again, there

was no indication that publication of these amendments raised any

Congressional eyebrows.

As the district court recognized, these regulations explicitly

adopt an "effects" standard. The HEW Title VI regulations appear

in 45 C.F.R. 80.3(b), and are divided into two principal parts.

30

45 C.F.R. 80.3(b)(1) contains a non-inclusive definition of some

specific discriminatory practices. It explicitly prohibits

actions which "restrict any individual in any way in the enjoy

ment of any advantage or privilege enjoyed by others receiving

any service..." (45 CFR § 80. 1 (b) ( 1 ) ( i v) ) , or afford them an

opportunity to participate in a federal assisted program "which

is different from that afforded others under the program " (45

CFR § 80.3(b)(1)(vi)).

Subsequent portions of those regulations make clear that

actions which result in any of the kinds of discrimination

described in § 80.3(b)(1) or which otherwise have a disparate

adverse impact upon minorities constitute a prima facie violation

of Title VI. Thus 45 C.F.R. § 80.3(b) further provides:

(2) A recipient, in determining the types of

... or in determining the situations in which

such serices ... or facilities will be provided

... may npt ... utilize criteria or methods of

administration which have the effect of sub

jecting individuals to discrimination ... or have

the effect of defeating or substantially impairing

accomplishment of the objectives of the program

as respect individuals of a particular race,

color, or national origin.

(3) In determining the site or location of

facilities, an applicant may not make selections

with the effect of excluding individuals from,

denying them the benefits of, or subjecting them

to discrimination .. or with the purpose or effect

of defeating or substantially impairing the ac

complishment of the objectives of the Act or this

regulation.

The Title VI regulations were promulgated pursuant to the

express mandate of § 1602 of Title VI, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d-1, and

were approved by the President. Regulations issued pursuant to

Congressional mandate are presumptively valid and ordinarily will

31

be upheld unless inconsistent with the statute. "The validity of

a regulation. . . will be sustained so long as it is reasonably

related to the purpose of the enabling legislation" Mourning v.

Family Publications Service, 411 U.S. 356, 369 (1973). The

presumption of validity accorded federal regulations also applies

with special force to regulations which constitute a consistent

and contemporaneous interpretation of the statute by those agencies

charged with its enforcement Udall v. Tallman, 380 U.S. 1, 16

(1965). Moreover, an agency's own interpretation of its own

regulations is entitled to almost conclusive deference. Ford

Motor Credit Co. v. Milhollin, ___U.S. ___, 48 U.S.L.W. 4145 (Feb.

20, 1980).

5. Congressional enactments subsequent to

1964 reflect a continued Congressional

understanding that Title VI prohibits

conduct having a disparate impact upon

minorities.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly held that subsequent legis

lation reflecting Congressional interpretation of an earlier act

is entitled to great weight in determining the meaning of the

earlier statute. Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. FCC, 395 U.S. 367,

380-381 (1968); Erlenbaugh v. United States, 409 U.S. 239, 243-

244 (1972). It is thus significant that well after it was aware

that Title VI had been interpreted to prohibit disparate impact

discrimination, Congress enacted virtually identical language

32

. . 12/in ten additional statutes.— 7 Each of these statutes was

explicitly patterned after Title VI. Presumably, if Congress had

been disturbed by the construction accorded Title VI, it would

have taken steps to assure that the other statutes were interpret

ed differently. There is no indication in the language or

history of any of these Title VI offspring which would indicate

that Congress felt Title VI had been incorrectly construed by the

regulations.

The district court brushed aside the impressive statutory and

regulatory history supporting the effect standard by suggesting

that Congressional inaction was consistent with a Congressional

intention that the standard for Title VI change with changing

judicial interpretations of the constitutional standard under the

Fourteenth Amendment. (2d opinion, p. 38). But in 1977 and

1979, well after the Title VI effect standard was approved in Lau

(1974) and the differing constitutional standard was established

in Washington v. Davis (1976), regulations explicitly adopting

the effect standard were promulgated under the Revenue Sharing

Act (31 C.F.R. § 51.52, 42 Fed. Reg. 18365, April 16, 1977), the

Age Discrimination Act (45 C.F.R. §90.12, 44 Fed. Reg. 33776,

March 12, 1979) and the Rehabilitation Act (45 C.F.R. § 1232.4,

1_2/ § 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, 29 U.S.C.A. § 729 (1 973),

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, 20 U.S.C.A. § 1681,

the Revenue Sharing Act, 31 U.S.C.A. § 1242 (1976), and the Age

Discrimination Act, 42 U.S.C.A. § 6106 (1975). Public Works r

Employment Act, 42 U.S.C. § 6727; Railroad Revitalization aricU-^^

Regulatory Reform Act of 1976, 45 U.S.C. § 803; Emergency Con

servation and Resource Renewal Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C. § 68701;

Housing and Community Development Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C. § 5309;

Juvenile Justice Act of 1974, 42 U.S.C. § 5672; Crime Control

Act of 1973), 42 U.S.C. § 3766.

33

44 Fed. Reg. 31018, May 30,1979), the very acts with anti-dis

crimination provisions modeled after Title VI. And, of course,

the Title VI standards remained in force and were enforced by the

courts. See, e.g., NAACP v. Wilmington Medical Center, 453 F.

Supp. 280, 308 (D. Del. 1978), rev'd on other grounds, 599 F .2d

1247 (3d Cir. 1979). If Congress intended that the standard for

Title VI and its offspring required intentional discrimination it

most certainly would have acted under these regulations. It did

not do so. "[W]here Congress, by its positive inaction has allowed

those decisions to stand for so long and, far beyond mere inference

and implication, has clearly evinced a desire not to disapprove

them legislatively," the courts should not usurp Congress.

Flood v. Kuhn, 407 U.S. 258, 283-284 (1972).

H. Retention Of The Disparate Effect Standard Is

Necessary If Title VI Is To Be An Effective

Remedy to Prevent Racial Discrimination.

If Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 is to retain any

vitality as a means of combating racial discrimination it must

address itself to the reality of the forms of discrimination, that

perpetuate inequality in our society and how those forms change

with time. The New York Times editorial on May 19, 1980, comment-

13/

ing on the recent voting rights cases of the Surpeme Court,

put the matter succinctly and graphically:

1_3/ City of Mobile, Alabama v. Bolden, ___U.S. ___ (April

22, 1980) and City of Rome v. United States, U.S.

(April 22, 1980).

34

The truth is, nowadays, that a racially improper

motive is very hard to prove. Anyone setting out

to discriminate no longer says openly, as the mayor

of Richmond, Va., said just a decade ago, 'Niggers

won't take over this town.'.

See also Metropolitan Housing Development Corp. v. Village of

Arlington Heights, 558 F .2d 1283, 1288 (7th Cir. 1977).

Whether or not conduct which results in denial of equal benefits

to minorities can be shown to be the product of an intentional

design to discriminate, its impact on blacks, Hispanics, and other

minority Americans is destructive. The consequences of unequal

distribution of federally supported programs falls heaviest on the

poorest of the minority groups, which have already suffered from

societal discrimination that has mired them in poverty.

The litigation in the Arlington Heights case demonstrates

the necessity of adhering to the disparate impact standard.

After the Supreme Court ruled that no Fourteenth Amendmetn viola

tion was shown, the Seventh Circuit on remand found that a viola

tion of the Fair Housing Act had occurred even absent discrimina

tory intent, because otherwise racial discrimination would go

unremedied. 558 F .2d 1283, 1290. It stated:

14/ David Tatel, Director of HEW's Office of Civil Rights

from 1977 to 1979, reminds us that "the nation must deal with the

fundamental problem of its racism. In the words of the Kerner

Commission: 'What white American have never fully understood what

the Negro can never forget— is that white society is deeply

implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white

institutions maintain it and white society condones it.'" (Washing

ton Post, May 24, 1980, p. A15.)

35

Moreover, a requirement that the plaintiff prove

discriminatory intent before relief can be granted

under the statute is often a burden that is impos

sible to satisfy. "[I]ntent, motive and purpose

are elusive subjective concepts," Hawkins v. Town

of Shaw, 461 F .2d 1171, 1172 (5th Cir. 1972) (en

banc) (per curiam), and attempts to discern the

intent of an entity such as a municipality are at

best problematic... (citations omitted). A

strict focus on intent permits racial discrimina

tion to go unpunished in the absence of evidence

of overt bigotry. As overtly bigoted behavior

has become more unfashionable, evidence of intent

has become harder to find. But this does not

mean that racial discrimination has disappeared.

We cannot agree that Congress in enacting the

Fair Housing Act intended to permit municipali

ties to systematically deprive minorities of

housing opportunities simply because those

municipalities act discreetly. See Brest, The

Supreme Court, 1975 Term -- Forward: In Defense

of the Antidiscrimination Principle, 90 Harv. L.

Rev. 1 , 28-29 ( 1 976). Id. 1_5/

If intent were required to be shown, the minorities constituting

the plaintiff class in Arlington Heights would have been denied

the benefits of federal housing programs for low income persons.

Requiring justification from recipients of federal funds

where the adverse impact of their actions will significantly and

disproportionately burden minorities explicitly and directly

implements the Congressional intent under Title VI to foster

equitable use of federal funds. In Owens v. City of

Independence Missouri, ___ U.S. ___, 48 U.S.L.W. 4389 (April 16,

1980), the Supreme Court held that municipalities sued for

damages under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for constitutional violations are

not entitled to qualified immunity based on good faith of

1_5/ Accord, Robinson v. 12 Lofts Realty, Inc. , 610 F . 2d

1032 (2d Cir. 1979).

36

their officials. In doing so, the Court emphasized the public

policy considerations which compel holding municipalities

accountable:

The knowledge that a municipality will be liable

for all of its injurious conduct, whether com

mitted in good faith or not, should create an

incentive for officials who may harbor doubts

about the lawfulness of their intended actions

to err on the side of protecting citizens'

constitutional rights ....

More important, though, is the allegation

that consideration of the municipality's lia

bility for constitutional violations is quite

properly the concern of its elected or ap

pointed officials. Indeed, a decisionmaker

would be derelict in his duties if, at some

point, he did not consider whether his deci

sion comports with constitutional mandates and

did not weigh the risk that a violation might

result in an award of damages from the public

treasury. As one commentator aptly put it,

"whatever other concerns should shape a par

ticular official's actions, certainly one of

them should be the constitutional rights of

individuals who will be affected by his actions.

To criticize section 1983 liability because it

leads decisionmakers to avoid the infringement

of constitutional rights is to criticize one of

the statute's raisons d 'etre." 48 U.S.L.W.

at 4397, 4398 (footnotes omitted).

What was stated in Owens regarding § 1983 is no less

applicable in the context of this case: to criticize the

Title VI standard urged by HEW and heretofore unanimously

adopted by courts, is to criticize the reason for its

passage. Before a decision is made which disproportionately

tucdens minorities, the decision-maker — be it a governmen

tal or private recipient of federal funds — should carefully

consider whether the decision is a reasonable, justifiable

one and whether there are not other alternatives whose

37

consequences are less onerous to minorities.

The district court's exaggerated fear at page 43 of its

amended opinion (App. P. ___) that the spectre of an impact

standard under Title VI will discourage "essential decisions"

is unfounded. First, "essential" decisions imply no alterna

tives; hence no violation of Title VI. Second, since 1964,

HEW and the courts have interpreted Title VI to have the very

standard the district court holds for the first time to be invalid.

Yet no one, asserts that Title VI has in fact hamstrung governmen

tal decision-making. Indeed, the correctness of the Title VI

impact standard has perhaps been at no time as evident as in

present day circumstances. As the district court recognized, the

guarantees of Title VI become increasingly important in "present

time, when reductions in government services have become increasing

ly common, particularly in areas heavily populated by minorities."

(Op. pp. 3-4, App. p. ___). As the district court noted, these

decisions are political in nature. It has been the role of

federal civil rights law to protect minorities from discrimination

in majoritarian decisions.

When essential services such as federally-funded hospital

services are to be cut, decisionmakers should not ignore the race

of the persons affected nor should they ignore and fail to consider

alternative actions. Where the municipality has ignored the

impact on minorities, whether intentionally or not, the need for

justification operates as an effective restraint on discrimina

tion. C_f. Robinson v. 12 Lofts Realty, Inc., supra, 610 F . 2d at

38

1040-43. In considering the added burden such exploration entails

the additional thought processes and action required must be

weighed against the harm to minorities who depend upon these

services to save lives. C_f. Owens v. City of Independence, supra,

48 U.S.L.W. at p. 4398.

I. This Court Should Reach The Issue Of the Proposed

Standard under Title VI To Govern The Future

Proceedings in This and Other Cases

.S'This Court must reach the isue of the legal standard underA

Title VI. The plaintiffs established a violation of Title VI

under the proper "effect" standard. As the following section

demonstrates, the district court's findings of facts were insuffi

cient to support its brief ultimate conclusion that the standard

was not satisfied.

Moreover Under the Mayor's Plan, approved by the Board of

Directors, of the Health and Hospitals Corporation, Metropolitan

Hospital is to be closed. Metropolitan is the major health care

institution for the Hispanic community of East Harlem. The court

below stated that "if Metropolitan were closed a far more serious

problem of access for minority patients would be presented. (Op.

p. 23, App. p. ___). The closing could be announced any day and

plaintiffs would be forced to begin an immediate hearing on its

motion for preliminary hearing which has been deferred until now

by the district court.

39

II. PLAINTIFFS ESTABLISHED A SUBSTANTIAL LIKELI

HOOD OF PREVAILING ON THEIR TITLE VI CLAIM;

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRONEOUSLY FAILED TO

REQUIRE DEFENDANTS TO PROVIDE ASSURANCES OF

ALTERNATE ACCESS TO ESSENTIAL SERVICES AND

RELIED INSTEAD ON A HYPOTHETICAL ACCESS

CONSTRUCT

16/

Under the Title VI regulations promulgated by HEW, and

11/interpreted by them, the determination of whether a Title VI

violation occurs requires a three part analysis:

(1) Does a disproportionate adverse impact result

from the closings or reductions in service;

(2) If so, are the closings and reductions nec

essary to achieve legitimate objectives unrelated to

race, and

(3) Can these objectives be achieved by other

measures which have a less disproportionate adverse

e f fe ct.

As shown below, the District Court's found there is a dis

parate impact on minorities from the closing of Sydenham Hospital

(pp. ), and that the impact will have adverse effects on the

health and lives of those affected (pp. ). The unrebutted

evidence also demonstrated that City defendants did not exploure