Background on Phillips v. the Martin Marietta Corp. and Griggs v. the Duke Power's Dan River Steam Station

Press Release

December 3, 1970

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 6. Background on Phillips v. the Martin Marietta Corp. and Griggs v. the Duke Power's Dan River Steam Station, 1970. cf4e954c-ba92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/510e6652-e7f1-4826-a944-3ea0e7da6c89/background-on-phillips-v-the-martin-marietta-corp-and-griggs-v-the-duke-powers-dan-river-steam-station. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

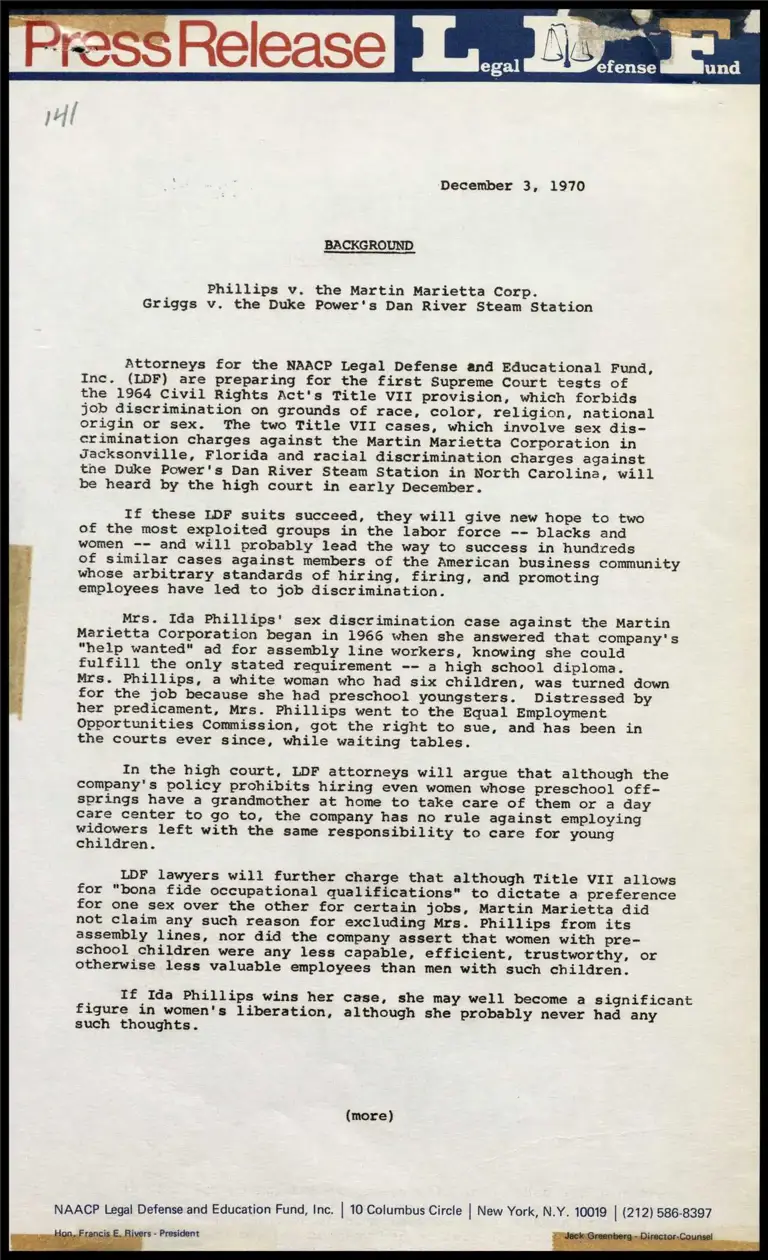

ressRelease p iat an a

December 3, 1970

BACKGROUND

Phillips v. the Martin Marietta Corp.

Griggs v. the Duke Power's Dan River Steam Station

Attorneys for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. (LDF) are preparing for the first Supreme Court tests of

the 1964 Civil Rights Act's Title VII provision, which forbids

job discrimination on grounds of race, color, religion, national

origin or sex. The two Title VII cases, which involve sex dis-

crimination charges against the Martin Marietta Corporation in

Jacksonville, Florida and racial discrimination charges against

the Duke Power's Dan River Steam Station in North Carolina, will

be heard by the high court in early December.

If these LDF suits succeed, they will give new hope to two

of the most exploited groups in the labor force -- blacks and

women -- and will probably lead the way to success in hundreds

of similar cases against members of the American business community

whose arbitrary standards of hiring, firing, and promoting

employees have led to job discrimination.

Mrs. Ida Phillips' sex discrimination case against the Martin

Marietta Corporation began in 1966 when she answered that company's

“help wanted" ad for assembly line workers, knowing she could

fulfill the only stated requirement -- a high school diploma.

Mrs. Phillips, a white woman who had six children, was turned down

for the job because she had preschool youngsters. Distressed by

her predicament, Mrs. Phillips went to the Equal Employment

Opportunities Commission, got the right to sue, and has been in

the courts ever since, while waiting tables.

In the high court, LDF attorneys will argue that although the

company's policy prohibits hiring even women whose preschool off-

springs have a grandmother at home to take care of them or a day

care center to go to, the company has no rule against employing

widowers left with the same responsibility to care for young

children.

LDF lawyers will further charge that although Title VII allows

for "bona fide occupational qualifications" to dictate a preference

for one sex over the other for certain jobs, Martin Marietta did

not claim any such reason for excluding Mrs. Phillips from its

assembly lines, nor did the company assert that women with pre-

school children were any less capable, efficient, trustworthy, or

otherwise less valuable employees than men with such children.

If Ida Phillips wins her case, she may well become a significant

figure in women's liberation, although she probably never had any

such thoughts.

NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. | 10 Columbus Circle | New York, N.Y. 10019 | (212) 586-8397

= President

Phillips v. Martin Marietta

Griggs v. Duke Power's Dan River Steam Station -2-

A few statistics reveal the implications of her challenge.

While 29% of the mothers of preschool children work, the majority

of these are nonwhites who work out of need, rather than choice.

Ida Phillips is making a fight for the equal rights of all women,

but it is minority women who have the most to gain from her claim.

In the second test case, Willie S. Griggs, a black man:who

works as a power company laborer, is charging racial discrimination

against his employer, the Duke Power's Dan River Steam Station. His

complaint attacks testing and formal educational requirements at

Duke where their effect is to disqualify a disproportionate number

of blacks from jobs or promotions, and where these requirements

have no demonstrable relationship to the skills needed to perform

the job.

LDF lawyers hope to show that these testing and educational

requirements kept Griggs pinned at the lowest level in his

company, where, after seven years of employment and earning top

pay in his company's traditionally black Labor Department, he was

still making less than the minimum any white employee took home.

Duke, which generates and sells electricity, is a company that

Maintained separate drinking, toilet, and locker facilities labelled

“white" and "colored" until a few years ago.

Not until a year after passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act

did the first black man escape from the Labor Department to a

position one peg above in the Coal Handling Department. That

man had 13 years' seniority and a high school education. Almost

immediately afterward, the company laid down additional requirements

for transferring a step up from the black Labor Department: either

you had to have a high school diploma, management said, or achieve

a specific score on one of two (highly abstract) intelligence

tests -- the "Wonderlic" or the "Bennett."

A lower court and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit have already ruled that the policy placed an unfair

burden on Duke's long-tenured black employees, since tenured white

workers had been permitted for years to transfer throughout the

plant without passing tests or having a high school diploma.

Now, LDF lawyers hope the Supreme Court will find that the

kinds of tests and educational requirements Duke adopted violate

Title VII because they (1) exclude blacks disproportionately and

(2) have nothing to do with the ability to do the job in question.

Underlying this challenge to the discriminatory policies of

Duke, are the conditions under which most blacks get their education

in the South, which make it less likely for black people than for

whites to be able to satisfy such testing and schooling requirements.

Statistics point to the fact that only a third as many black

men as whites graduate from high school in North Carolina. Segregated,

inferior education serves to remove a great deal of the inclination

to learn. Add to that the evidence that formal education often does

little to improve a black man's chances in the South, and the common

need to bring some money into a poor household at an early age, and

the high rate of early dropoutism there becomes easy to understand.

That was even more true in Griggs' school days than now.

=30=