Davidson v. City of Cranston, RI Brief of Amici Curiae in Support of Plaintiffs-Appellees and Affirmance

Public Court Documents

August 31, 2016

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Davidson v. City of Cranston, RI Brief of Amici Curiae in Support of Plaintiffs-Appellees and Affirmance, 2016. 669103fe-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/513a2b5f-5cca-463c-8926-0209f0b57b45/davidson-v-city-of-cranston-ri-brief-of-amici-curiae-in-support-of-plaintiffs-appellees-and-affirmance. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

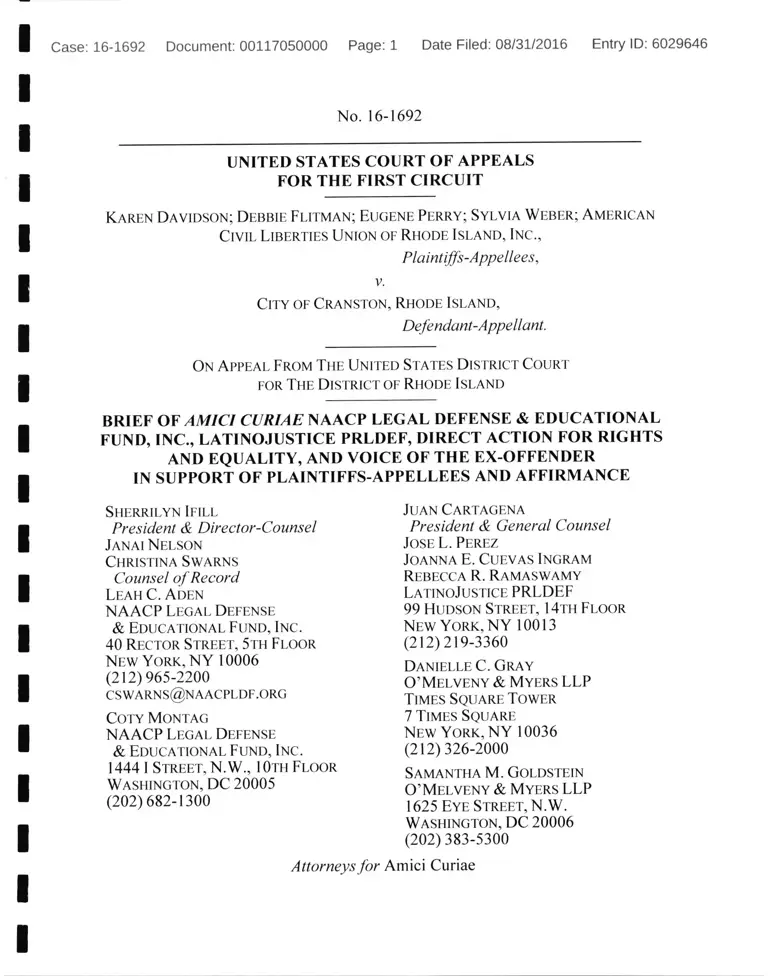

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 1 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

No. 16-1692

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIRST CIRCUIT

Karen Davidson; Debbie Flitman; Eugene Perry; Sylvia Webf.r; American

Civil Liberties Union of Rhode Island, Inc.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

City of Cranston, Rhode Island,

Defendant-A ppellant.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

for The District of Rhode Island

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC., LATINOJUSTICE PRLDEF, DIRECT ACTION FOR RIGHTS

AND EQUALITY, AND VOICE OF THE EX-OFFENDER

IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES AND AFFIRMANCE

Sherrilyn Ifill

President & Director-Counsel

Janai Nelson

Christina Swarns

Counsel o f Record

Leah C. Aden

NAACP Legal Defense

& Educational Fund, Inc.

40 Rector Street, 5th Floor

New York, NY 10006

(212) 965-2200

CSWARNS@NAACPLDF.ORG

Coty Montag

NAACP Legal Defense

& Educational Fund, Inc.

1444 I Street, N.W., 10th Floor

Washington, DC 20005

(202)682-1300

Juan Cartagena

President & General Counsel

JoseL. Perez

Joanna E. Cuevas Ingram

Rebecca R. Ramaswamy

LatinoJustice PRLDEF

99 Hudson Street, 14th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212)219-3360

Danielle C. Gray

O'Melveny & Myers LLP

Times Square Tower

7 Times Square

New York, NY 10036

(212)326-2000

Samantha M. Goldstein

O'Melveny & Myers LLP

1625 Eye Street, N.W.

Washington, DC 20006

(202)383-5300

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

mailto:CSWARNS@NAACPLDF.ORG

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 2 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

STATEMENT REGARDING LEAVE TO FILE, JUSTIFICATION FOR

SEPARATE BRIEFING, AUTHORSHIP, AND MONETARY

CONTRIBUTIONS

The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc., LatinoJustice

PRLDEF, Direct Action for Rights and Equality, and Voice of the Ex-Offender file

this brief as amici curiae, pursuant to this Court's July 28, 2016, order inviting

amici briefs to be filed in this case. See Fed. R. App. P. 29(a), (c)(4).1 Amici curiae,

as organizations dedicated to promoting civil rights and racial equality throughout

the United States, are uniquely situated to provide context and perspective on why

prison-based gerrymandering dilutes the political power ot communities of color

and violates the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

Pursuant to Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure 29(c), amici curiae state

that no counsel for any of the parties authored this brief in whole or in part; neither

the parties nor their counsel contributed money that was intended to fund the

preparation or submission of this brief; and no person, other than the amici curiae,

1 Although this Court’s July 28, 2016, order invited amicus briefs to be filed in this

case, out of an abundance of caution, counsel for amici sought the consent of

defendant-appellant, the City of Cranston, to amici s participation. According to

the City’s attorneys, the City has not responded to their inquiry regarding am icis

request for consent. The City’s attorneys, however, indicated that they do not

believe the City’s consent is necessary, and that they would not object to amici's

filing of an amicus brief should an objection be raised. Again out of an abundance

of caution, amici filed, with this brief, a motion for leave to file a brief as amici

curiae in this case.

i

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 3 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

their members, or their counsel, contributed money that was intended to fund this

brief s preparation or submission. See Fed. R. App. P. 29(c)(5).

u

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 4 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Pursuant to Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure 26.1 and 29(c)(1), amici

curiae are non-profit organizations that have not issued shares or debt securities to

the public, and they have no parents, subsidiaries, or affiliates that have issued

shares or debt securities to the public.

iii

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 5 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

STATEMENT REGARDING LEAVE TO FILE, JUSTIFICATION FOR

SEPARATE BRIEFING, AUTHORSHIP, AND MONETARY

CONTRIBUTIONS...................................................................................................... '

CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT........................................................ iii

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE.............................................................................xiii

INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................... 1

ARGUMENT............................................................................................................... 3

I. PRISON-BASED GERRYMANDERING IS A NATIONWIDE

CONSTITUTIONAL PROBLEM OF STAGGERING

MAGNITUDE................................................................................................... 3

A. Prison-based gerrymandering disconnects legislative districts

from the people they are meant to represent..........................................3

B. Prison-based gerrymandering distorts the building blocks of our

democracy............................................................................................... 6

C. Prison-based gerrymandering transfers political power from

diverse urban communities to largely white, rural areas....................9

D. Prison-based gerrymandering dilutes the political power of all

communities, including rural ones, without prison facilities..............11

E. The Supreme Court repeatedly has held that distortions like

those caused by prison-based gerrymandering are

unconstitutional..................................................................................... 13

II. PRISON-BASED GERRYMANDERING

DISPROPORTIONATELY HARMS VOTERS OF COLOR AND

THE COMMUNITIES IN WHICH THEY LIVE......................................... 17

A. Prison-based gerrymandering disempowers Black and Latino

communities...........................................................................................17

IV

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(continued)

Page

B. Prison-based gerry mandering harms communities of color not

only by diluting their voting and representational strength, but

also by impeding remedial redistricting and criminal justice

reform.................................................................................................... 22

C. The race-based harms of prison-based gerrymandering resemble

the unconscionable three-fifths compromise.......................................26

CONCLUSION..........................................................................................................29

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 6 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

v

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page(s)

CASES

Bartlett v. Strickland,

556 U.S. 1 (2009).................................................................................................. 18

Bd. o f Estimate o f City o f New York v. Morris,

489 U.S. 688 (1989)...............................................................................................16

Brown v. Thomson,

462 U.S. 835 (1983)............................................................................................... 15

Calvin v. Jefferson Cnty. Bd. o f Comm 'rs,

2016 WL 1122884 (N.D. Fla. Mar. 19, 2016).....................................................25

Chisom v. Roemer,

501 U.S. 380 (1991)............................................................................................. xiii

Fletcher v. Lamone,

831 F. Supp. 2d 887 (D. Md. 2011), aff’d,, 133 S. Ct. 29 (2012)...............xiii, 22

Franklin v. Massachusetts,

505 U.S. 788 (1992)................................................................................................. 1

Gomillion v. Lightfoot,

364 U.S. 339(1960)............................................................................................. xiii

Gray v. Sanders,

372 U.S. 368 (1963)..............................................................................................14

Kirkpatrick v. Preisler,

394 U.S. 526(1969)..............................................................................................13

League o f United Latin Am. Citizens v. Perry,

548 U.S. 399 (2006)............................................................................................xiii

Mahan v. Howell,

410 U.S. 315 (1973)............................................................................................... 4

Reynolds v. Sims,

377 U.S. 533 (1964)............................................................................. 1, 13, 14, 16

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 7 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

vi

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 8 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(continued)

Page(s)

Roman v. Sincock,

377 U.S. 695 (1964).............................................................................................. 17

Shelby Cnty. v. Holder,

133 S. Ct. 2612 (2013)......................................................................................... xiii

Smith v. Allwright,

321 U.S. 649(1944)............................................................................................. xiii

Terry v. Adams,

345 U.S. 461 (1953)............................................................................................. xiii

Thornburg v. Gingles,

478 U.S. 30 (1986)............................................................................................... xiii

Utah v. Strieff,

No. 14-1373 (U.S. June 20, 2016), slip opinion..................................................25

Voinovich v. Quilter,

507 U.S. 146 (1993)............................................................................................... 16

VOTE v. Louisiana,

No. 6499587 (La. 19th Jud. D. Ct. July 1,2016)................................................xv

STATUTES

52 U.S.C. § 10301....................................................................................................... 18

R.I. Gen. Laws § 17-1-3.1(a)(2)................................................................................ 28

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS

U.S. Const, art. 1, § 2, cl. 3, amended by U.S. Const, amend. XIV........................26

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Alison Walsh, The Formerly Incarcerated and Convicted People’s

Movement objects to being counted in the wrong jurisdictions (July

27, 2016)................................................................................................................ 27

vii

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 9 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(continued)

Page(s)

Alison Walsh, “Over a dozen prisons in several different states

Letter to Census Bureau describes temporary nature o f

incarceration, Prison Pol’y Initiative (Aug. 5, 2016)...........................................5

Andrea L. Maddan, Enslavement to Imprisonment: How the Usual

Residence Rule Resurrects the Three-Fifths Clause and Challenges

the Fourteenth Amendment, 15 Rutgers Race & L. Rev. 310 (2014)................24

Anthony C. Thompson, Unlocking Democracy: Examining the

Collateral Consequences o f Mass Incarceration on Black Political

Power, 54 How. L.J. 587 (201 1 )..................................................................... 8, 26

Anthony Thompson, Democracy Behind Bars, N.Y. Times (Aug. 5,

2009)........................................................................................................................ 9

Brent Staples, The Racist Origins o f Felon Disenfranchisement, N.Y.

Times (Nov. 18,2014).......................................................................................... 28

Brief of Amici Curiae Direct Action for Rights and Equality, et al., in

Support of Affirmance, Evenwel v. Abbott, No. 14-940, 2015 WL

5719754 (U.S. Sept. 25,2015)........................................................................ 7, 18

Brief of the Howard University School of Law Civil Rights Clinic, et

a l, as Amici Curiae Supporting Respondents, Fletcher v. Lamone,

831 F. Supp. 2d 887 (D. Md. 2011), aff’d, 133 S. Ct. 29 (2012)...............xiii, 13

Brief of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, et al.,

as Amici Curiae in Support of Appellees, Evenwel v. Abbott, No.

14-940 (U.S. Sept. 25,2015)...................................................................................6

Bruce Drake, Incarceration gap widens between whites and blacks,

Pew Research Ctr. (Sept. 6, 2013)..........................................................................18

Christopher Uggen & Sarah Shannon, State-Level Estimates o f Felon

Disenfranchisement in the United States, 2010, The Sentencing

Project (July 2012)............................................................................................... 28

Dale E. Ho, Captive Constituents: Prison-Based Gerrymandering and

the Current Redistricting Cycle, 22 Stan. L. & Pol’y Rev. 355

(2011)............................................................................................................. .passim

viii

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 10 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(continued)

Page(s)

David Hamsher, Comment, Counted Out Twice—Power,

Representation, & the “Usual Residence Rule” in the Enumeration

o f Prisoners: A State-Based Approach to Correcting Flawed

Census Data, 96 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 299 (2005).........................9, 21,24

Decision/Order, Index No. 2310-2011, Little v. LA TFOR (N. Y. Sup.

Ct. Aug. 4, 2011).........................................................................................xiii,xiv

Ending Prison-Based Gerrymandering Would Aid the A frican-

American and Latino Vote in Connecticut, Prison Pol’y Initiative

& Common Cause Conn. (2010)......................................................................... 20

Ending Prison-Based Gerrymandering Would Aid the African-

American Vote in Maryland, Prison Pol'y Initiative (Jan. 22, 2010).................10

Erika L. Wood, Implementing Reform: How Maryland & New York

Ended Prison Gerrymandering, Demos (2014)............................................11,22

Exec. Office of the President, Economic Perspectives on Incarceration

and the Criminal Justice System (2016).............................................................. 19

Federal Bureau of Prisons, Inmate Race (last updated Feb. 21,2015)....................17

Heather Ann Thompson, How Prisons Change the Balance o f Power

in America, Atlantic (Oct. 7, 2013)............................................................... 15, 25

Jean Chung, Felony Disenfranchisement: A Primer, The Sentencing

Project (May 10, 2016).........................................................................................27

Karen Humes, et al., Overview o f Race and Hispanic Origin: 2010,

2010 Census Briefs (Mar. 2011)......................................................................... x'v

Kenneth Johnson, Demographic Trends in Rural and Small Town

America, Carsey Inst., Univ. of New Hampshire (2006)..................................... 9

Kenneth Prewitt, Forward, Accuracy Counts: Incarcerated People &

The Census, Brennan Ctr. for Justice (April 8, 2004)...................................... 5, 6

Lani Guinier & Gerald Torres, The Miner’s Canary: Enlisting Race,

Resisting Power, and Transforming Democracy (2002).................................... 19

IX

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 11 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(continued)

Page(s)

LDF, Free the Vote: Unlocking Democracy in the Cells and on the

Streets.............................................................................................................. 27, 28

Leah Sakala, Breaking Down Mass Incarceration in the 2010 Census:

State-by-State Incarceration Rates by Race/Ethnicity, Prison Pol’y

Initiative (May 28, 2014).....................................................................................17

Letter from Juan Cartagena, President & General Counsel, et al., to

Karen Humes, Chief, Population Division, U.S. Census Bureau

(Aug. 22,2016)....................................................................................................xiv

Letter from Justin Levitt, Professor, Loyola Law School, to Karen

Humes, Chief, Population Division, U.S. Census Bureau (July 20,

2015)..................................................................................................... 6, 12, 13, 18

Letter from Leah C. Aden, Assistant Counsel, LDF, to Cale P. Keable,

Chairperson, Rhode Island House Committee on the Judiciary

(Apr. 13,2015)...............................................................................................xiv, 20

Letter from Leah C. Aden, Assistant Counsel, LDF, to Karen Humes,

Chief, Population Division, U.S. Census Bureau (July 19, 2015)....................xiii

Letter from Norris Henderson, Executive Director, VOTE, to Karen

Humes, Chief, Population Division, U.S. Census Bureau (July 14,

2015)...................................................................................................................... xv

Letter from Peter Wagner, Executive Director, Prison Policy

Initiative, to Karen Humes, Chief, Population Division, U.S.

Census Bureau (July 20, 2015)............................................................................... 5

Local Governments That Avoid Prison-Based Gerrymandering, Prison

Pol’y Initiative (last updated May 13, 2016)....................................................... 22

Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the

Age of Colorblindness (2010)...............................................................................19

Nathaniel Persily, The Law o f the Census: How to Count, What to

Count, Whom to Count, and Where to Count Them, 32 Cardozo L.

Rev. 755 (201 1)..................................................................................................... 19

x

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 12 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(continued)

Page(s)

Peter Wagner, 98% o f New York’s Prison Cells Are in

Disproportionately White Senate Districts, Prison Pol y Initiative

(Jan. 17, 2005)........................................................................................................ 19

Peter Wagner, Breaking the Census: Redistricting in an Era oj Mass

Incarceration, 38 Wm. Mitchell L. Rev. 1241 (2012)................................. 23, 25

Peter Wagner & Daniel Kopf, The Racial Geography o f Mass

Incarceration (July 2015)..................................................................................... 21

Prison Pol’y Initiative, A sample o f the comment letters submitted in

2015 to the Census Bureau calling for an end to prison

gerrymandering (last visited Aug. 25, 2016)........................................................ 4

Representative-Inmate Survey, Senate Education, Health, and

Environmental Affairs Committee, Bill File: 2010 Md. S.B. 400 .....................13

Sam Roberts, Census Bureau's Counting of Prisoners Benefits Some

Rural Voting Districts, N.Y. Times (Oct. 23, 2008).......................................... 12

Sara Mayeux, Rhode Island mayor: Prisoners count as residents when

it helps me, not when it helps them, Prison Pol’y Initiative (Mar.

31.2010) ................................................................................................................ 4

The Sentencing Project, Fact Sheet: Felony Disenfranchisement Laws

(2015)..................................................................................................................... 28

Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman, Counting Matters: Prison Inmates,

Population Bases, and “One Person, One Vote ”, 11 Va. J. Soc.

Pol’y & L. 229 (2004)............................................................................................ 10

Testimony of Dale E. Ho, Assistant Counsel, LDF, Hearing Before

the Kentucky General Assembly Task Force on Elections,

Constitutional Amendments, and Intergovernmental Affairs (Aug.

23.2011) ................................................................................................................ 8

Todd A. Breitbart, Comment, 2020 Decennial Census Residence Rule

and Residence Situations, Docket No. 150409353-5353-01 (July

18,2015).................................................................................................................12

xi

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 13 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

(continued)

Page(s)

U.S. Census Bureau, Quick Facts (last visited Aug. 25, 2016)............................... 17

U.S. Census Bureau, Residence Rule and Residence Situations for the

2010 Census, U.S. Census 2010 (Sept. 22, 2015).................................................3

Voting While Incarcerated: A Tool Kit for Advocates Seeking to

Register, and Facilitate Voting by Eligible People in Jail, Am. Civ.

Liberties Union & Right to Vote (Sept. 2005)....................................................28

xii

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 14 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. (“LDF”)—founded

over 75 years ago under the direction of Thurgood Marshall—is the nation's first

civil rights and racial justice organization. An integral component of LDF's

mission continues to be the attainment of unfettered participation in political life

for all Americans, including Black Americans. LDF has represented parties in

numerous voting rights cases, including before the U.S. Supreme Court.'

Consistent with its mission, LDF has participated in national and state-based

efforts to end prison-based gerrymandering, which, as explained herein,

significantly and impermissibly weakens the political power of communities ot

color.3 LDF has urged the Rhode Island Legislature, in particular, to adopt

legislation prohibiting prison-based gerrymandering.4

See, e.g., Shelby Cnty. v. Holder, 133 S. Ct. 2612 (2013); League o f United

Latin Am. Citizens v. Perry, 548 U.S. 399 (2006); Chisom v. Roemer, 501 U.S. 380

(1991); Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986); Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364

U.S. 339 (1960); Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461 (1953); Smith v. Allwright, 321

U.S. 649 (1944).

See, e.g., Letter from Leah C. Aden, Assistant Counsel, LDF, to Karen

Humes, Chief, Population Division, U.S. Census Bureau (July 19, 2015),

http://www.naacpldf.org/files/case_issue/NAACP%20LDF%20Re%20Residence

%20Rule.pdf; Brief of the Howard University School of Law Civil Rights Clinic,

et al., as Amici Curiae Supporting Respondents, Fletcher v. Lamone, 831 F. Supp.

2d 887 (D. Md. 2011), aff’d, 133 S. Ct. 29 (2012), http://www.naacpldf.org/

document/fletcher-v-lamone-brief-naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-inc-

et-al (“Howard Brief’); Decision/Order, Index No. 2310-2011, Little v. LATFOR

xiii

http://www.naacpldf.org/files/case_issue/NAACP%20LDF%20Re%20Residence

http://www.naacpldf.org/

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 15 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

LatinoJustice PRLDEF (“LJP”)—formerly known as the Puerto Rican Legal

Defense and Education Fund—is one of the nation's leading nonprofit civil rights

law firms. LJP's continuing mission is to advance, encourage, and protect the civil

rights of all Latinos/as,* 4 5 and to promote justice for the pan-Latino community.

Since LJP's founding in 1972, when it initiated a series of lawsuits seeking to

create bilingual voting systems throughout the United States, LJP consistently has

strived, in particular, to secure the voting rights of Latinos/as. To that end, LJP also

has engaged in national and state-based efforts to end prison-based

gerrymandering.6

(N.Y. Sup. Ct. Aug. 4, 2011), http://www.naacpldf.org/ document/order-granting-

intervention (“LATFOR Decision”).

4 Letter from Leah C. Aden, Assistant Counsel, LDF, to Cale P. Keable,

Chairperson, Rhode Island House Committee on the Judiciary (Apr. 13, 2015),

http://www.naacpldf.org/document/letter-urges-rhode-island-house-committee-

judiciary-pass-pending-legislation-ending-prison- (“Rhode Island Letter').

5 In this brief, the terms “Hispanic” and “Latino/a” are used interchangeably

and, as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau, “refer[] to a person of Cuban, Mexican,

Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin

regardless of race.” Karen Humes, et al., Overview o f Race and Hispanic Origin:

2010, 2010 Census Briefs, 1-2 (Mar. 2011), http://www.census.gov/prod/

cen2010/briefs/c2010br-02.pdf.

See, e.g., Letter from Juan Cartagena, President & General Counsel, et al., to

Karen Humes, Chief, Population Division, U.S. Census Bureau (Aug. 22, 2016),

http://preview.latinojustice.org/briefmg_room/press_releases/LatinoJustice_PRLD

EF Reply_Comment_Letter_to_US Census Proposed_2020_Decennial_Residenc

e_Rule_and_Residence_Situations_81_Fed_Reg_42_577.pdf (“Letter from LJP”);

LATFOR Decision.

xiv

http://www.naacpldf.org/

http://www.naacpldf.org/document/letter-urges-rhode-island-house-committee-judiciary-pass-pending-legislation-ending-prison-

http://www.naacpldf.org/document/letter-urges-rhode-island-house-committee-judiciary-pass-pending-legislation-ending-prison-

http://www.census.gov/prod/

http://preview.latinojustice.org/briefmg_room/press_releases/LatinoJustice_PRLD

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 16 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

Direct Action for Rights and Equality (“DARE”) is a grassroots,

membership-based organization in Rhode Island that organizes low-income

families in communities of color to advocate for and effectuate social, economic,

and political justice. DARE joined together with hundreds of low-income people of

color to protest the city of Providence’s most recent redistricting. In 2010, DARE

also launched Rhode Island's campaign to end prison-based gerrymandering.

Voice of the Ex-Offender (“VOTE”) is a grassroots, membership-based

organization in Louisiana that works to protect the voting rights of and expand

civic engagement by the people most affected by the criminal justice system,

especially formerly incarcerated persons and their families. VOTE is the lead

plaintiff in VOTE v. Louisiana, No. 6499587 (La. 19th Jud. D. Ct. July 1,2016), a

class action lawsuit challenging Louisiana’s felon disfranchisement law. VOTE

also has campaigned tirelessly to end prison-based gerrymandering.7

Amici curiae have significant interests in ending the unconstitutional

practice of prison-based gerrymandering and promoting the full, fair, and free

political participation of Black and Latino/a people, and other communities of

color.

7 See, e.g., Letter from Norris Henderson, Executive Director, VOTE, to Karen

Humes, Chief, Population Division, U.S. Census Bureau (July 14, 2015),

http://www.prisonersofthecensus.org/letters/VOTE_Prison_Gerrymandering.pdf.

xv

http://www.prisonersofthecensus.org/letters/VOTE_Prison_Gerrymandering.pdf

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 17 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

INTRODUCTION

When redistricting, many states and local jurisdictions count incarcerated

people as “residents” of the prison facilities in which they are involuntarily

confined. That practice—“prison-based gerrymandering”—distorts our democratic

system of government by transferring voting and representational power from

areas without prisons to areas with them, without any legitimate justification. It

also violates the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution because it causes

the weight of a citizen’s vote and his access to representation to be “made to

depend on where he lives.” Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 567 (1964).

The burden of the distortions caused by prison-based gerrymandering is

unduly borne by people of color, and thus the practice is additionally suspect. As a

result of the failed “war on drugs,” and other laws, policies, and practices

effectuating mass incarceration, our nation’s prisons are disproportionately filled

with Black and Latino individuals from predominantly urban communities of

color. Instead of being counted in their mostly Black and Latino, urban home

communities, the more than two million people now incarcerated across the United

States are treated, for redistricting, as phantom “residents” of prison facilities that

are frequently located in rural, largely white communities, from which they are

physically segregated, and where they lack any “enduring tie[s].” Franklin v.

Massachusetts, 505 U.S. 788, 804 (1992). Prison-based gerrymandering thus

1

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 18 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

amplifies the votes of principally white individuals, who often live in rural

communities, while diluting the votes of mostly Black and Latino individuals, who

often live in urban areas. Like the shameful, and now unconstitutional, practice of

counting Black people as three-fifths of a person for redistricting during slavery,

prison-based gerrymandering perversely uses the bodies of incarcerated people of

color to inflate the voting strength of white communities.

Prison-based gerrymandering also harms Black and Latino individuals in

myriad other ways. Representatives of districts with an inflated imprisoned

population often do not consider themselves accountable to the incarcerated

population, whose residence is involuntary, often temporary, and segregated from

the surrounding community. Instead, incarcerated individuals are more accurately

and fairly represented by leaders in the communities of their permanent residence,

where they are likely to have meaningful and longstanding ties. Prison-based

gerrymandering thus disconnects incarcerated individuals of color from the

officials best situated to advocate on their behalf. It also prevents incarcerated

people of color from effectuating policies to overcome past discrimination and

ameliorate systemic biases, like those underlying the failed "'war on drugs” and

mass incarceration. Representatives in areas with prisons have no incentive to end

such policies because incarcerated people typically cannot vote in those areas,

officials often perceive that communities with prisons tend to benefit economically

2

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 19 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

from their presence, and the urban areas where imprisoned people come from have

diluted voting strength and less representation due to prison-based gerrymandering.

Because the practice of prison-based gerrymandering in the City of Cranston

and across our country perverts the core principle of equal political participation

undergirding our democracy, to the particular detriment of Black and Latino

communities, this Court should not permit the City’s practice to stand.

ARGUMENT

I. PRISON-BASED GERRYMANDERING IS A NATIONWIDE

CONSTITUTIONAL PROBLEM OF STAGGERING MAGNITUDE.

A. Prison-based gerrymandering disconnects legislative districts

from the people they are meant to represent.

Despite persistent opposition, the Census Bureau, in conducting its decennial

population count, applies the so-called “usual residence” rule, under which it treats

incarcerated people as “residents” of the prisons in which they are involuntarily

confined on Census Day.8 States and local jurisdictions typically rely exclusively

on Census data to draw legislative districts.9 But there is no federal statutory or

constitutional mandate that they do so. To the contrary, the Supreme Court has

held that jurisdictions may not rely upon Census data to redistrict where, as with

8 U.S. Census Bureau, Residence Rule and Residence Situations for the 2010

Census, U.S. Census 2010 (Sept. 22, 2015), https://www.census.gov/population/

www/cen2010/resid_rules/resid rules.html.

There are, however, some noteworthy exceptions, as discussed infra at 21-22

& n.33.

3

https://www.census.gov/population/

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 20 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

prison-based gerrymandering, that information is inaccurate and not tailored to

local conditions. Mahan v. Howell, 410 U.S. 315, 320-21 (1973).

By using Census data that counts incarcerated persons at prisons during

redistricting, many jurisdictions draw legislative districts that consist largely of

prison populations—giving districts with prisons, despite having relatively fewer

actual residents, the same number of representatives as districts without them.10 11

Yet incarcerated people are not truly “residents” of prison facilities, as they have

no meaningful contact with the community surrounding them. Incarcerated people

cannot use the parks or libraries in that community. They cannot attend the

community’s schools, nor can their children." And they cannot freely seek

employment there. Moreover, because state prison sentences are typically two to

three years long, and incarcerated people “are frequently shuffled between

10 Because numerous jurisdictions use the Census Bureau s data to engage in

prison-based gerrymandering, stakeholders have repeatedly challenged the

Bureau’s use of the “usual residence” rule as applied to incarcerated persons. See,

e . g Prison Pol’y Initiative, A sample o f the comment letters submitted in 2015 to

the Census Bureau calling for an end to prison gerrymandering (last visited Aug.

25, 2016), http://www.prisonersofthecensus.org/letters/FRN2015.html.

11 See, e.g., Sara Mayeux, Rhode Island mayor: Prisoners count as residents

when it helps me, not when it helps them, Prison Pol’y Initiative (Mar. 31, 2010),

http://www.prisonersofthecensus.org/news/2010/03/31/rimayo/ (daughter of man

incarcerated in Cranston denied enrollment in Cranston’s public schools).

4

http://www.prisonersofthecensus.org/letters/FRN2015.html

http://www.prisonersofthecensus.org/news/2010/03/31/rimayo/

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 21 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

facilities at the discretion of [prison] administrators,”1- it strains credulity to think

that imprisoned people establish a meaningful “residence” in the numerous prisons

in which they are temporarily detained.'1

Given the involuntary and often temporary nature of incarceration, it is not

surprising that “[u]pon release the vast majority [of incarcerated people] return to

the community in which they lived prior to incarceration,”12 13 14 and where, even while

12 Letter from Peter Wagner, Executive Director, Prison Policy Initiative, to

Karen Humes, Chief, Population Division, U.S. Census Bureau, 3 (July 20, 2015),

http://www.prisonersofthecensus.org/letters/prison_policy_frn_census_

july_20_2015.pdf.

13 As of 2008 in New York, for example, the median time that an incarcerated

individual remained at a particular facility was only 7.1 months. Letter from LJP,

at 3. In Georgia, the average incarcerated individual has been transferred four

times, and will stay at any one facility, on average, only nine months. Id.

The experiences of imprisoned people demonstrate that a prison cell is a far

cry from home. For example, Nick Medvecky was incarcerated in federal prison

for twenty years and, in that time, he “was incarcerated in over a dozen different

prisons in seven different states”—with “[a]ll of these sites ... chosen by the prison

system, not [him]self.” Alison Walsh, “Over a dozen prisons in several different

states”: Letter to Census Bureau describes temporary nature o f incarceration,

Prison Poky Initiative (Aug. 5, 2016), http://www.prisonersof

thecensus.org/news/2016/08/05/comment_15/. Only one address remained

consistent throughout Medvecky’s incarceration: his home address. Id.

14 Kenneth Prewitt, Forward, Accuracy Counts: Incarcerated People & The

Census, Brennan Ctr. for Justice (April 8, 2004), http://www.brennancenter.org/

sites/default/files/legacy/d/RV4_AccuracyCounts.pdf (“Forward”).

5

http://www.prisonersofthecensus.org/letters/prison_policy_frn_census_

http://www.prisonersof

http://www.brennancenter.org/

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 22 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

in prison, many incarcerated people remain residents under state law.1' As former

Census Bureau Director Kenneth Prewitt put it, the “usual residence” rule blatantly

“ignore[s] the reality of prison life.” Prewitt, Forward.

B. Prison-based gerrymandering distorts the building blocks of our

democracy.

Prison-based gerrymandering enables a district with a prison to elect the

same number of representatives as a purportedly same-sized district without a

prison, even though the prison-containing district has fewer actual constituents and

eligible voters. This causes not only theoretical mathematical issues, but also fatal

constitutional problems, not to mention significant adverse policy consequences.15 16

15 See, e.g., Letter from Justin Levitt, Professor, Loyola Law School, to Karen

Humes, Chief, Population Division, U.S. Census Bureau, 2-3 (July 20, 2015),

http://redistricting.lls.edu/other/2015%20census%20residence%20comment.pdf

(“Levitt Letter”) (referencing 28 state laws, including Rhode Island’s, that

“explicitly provid[e] that incarceration does not itself’ change legal or electoral

residence).

16 The argument against prison-based gerrymandering does not mean that

noncitizens should be omitted from the total population count in their places of

actual residence. “Regardless of whether they are eligible to naturalize or choose to

do so, noncitizens who live in the United States have a deep stake in their

communities’ government, just as citizens do.” Brief of the Leadership Conference

on Civil and Human Rights, et al., as Amici Curiae in Support of Appellees,

Evenwel v. Abbott, No. 14-940, at 28-29 (U.S. Sept. 25, 2015),

http://www.scotusblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Redistricting.Evenwel.

amicuswith-Leadership-Conference-on-Civil-and-Human-Rights.pdf. It is critical

that all people, irrespective of their citizenship status, be counted as residents of the

communities in which they live, work, and contribute, and where their interests

will be represented.

6

http://redistricting.lls.edu/other/2015%20census%20residence%20comment.pdf

http://www.scotusblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Redistricting.Evenwel

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 23 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

Imagine, for example, that during redistricting, legislators using the “usual

residence” rule draw four wards of roughly 100 people each, and each ward elects

one representative to the city council. However, Ward 1 includes all 90 of the

community’s incarcerated people, and boasts only 10 free residents. Ward 1 thus

has 10 actual residents for each of the other ward’s 100. As a result, Ward l ’s

actual constituents wield 10 times more political clout than residents in the city’s

other three wards, simply because of where they live. As this example shows,

prison-based gerrymandering “results in serious population distortions in

redistricting,” and in elective districts that “fail[] to reflect accurately the

17demographics of numerous communities throughout our country.”

Due to the “usual-residence” rule used by the Census Bureau and “its flawed

application in redistricting, some two million incarcerated people” across the

United States “are being counted in the wrong place.” Brief of DARE, at *6

(emphasis added). According to the Bureau’s 2002 estimates, there are “more than

twenty counties in the United States where more than one-fifth of the population is

actually comprised of prisoners.” Dale E. Ho, Captive Constituents: Prison-Based 17

17 Brief of Amici Curiae Direct Action for Rights and Equality, et al., in

Support of Affirmance, Evenwel v. Abbott, No. 14-940, 2015 WL 5719754, at *5

(U.S. Sept. 25, 2015) (“Brief of DARE”).

7

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 24 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

Gerrymandering and the Current Redistricting Cycle, 22 Stan. L. & Pol'y Rev.

355, 359 (2011) (“Captive Constituents’’'').

Specific examples of the population distortions caused by prison-based

gerrymandering abound:

• In Lake County, Tennessee, prisoners account for

88% of the “population'” drawn into one county

commissioner district. Anthony C. Thompson,

Unlocking Democracy: Examining the Collateral

Consequences o f Mass Incarceration on Black

Political Power, 54 How. L.J. 587, 603 (2011)

(“Unlocking Democracy).

• In Morgan County, Kentucky, the total “population’'’

was said to be 13,948 people, though 1,664 (12%) of

that population was incarcerated.18 The Census

Bureau counted 611 African-American individuals as

residents of the County, even though 593 (96%) of

those individuals were incarcerated. Ho, Kentucky

Testimony.

• In La Villa, Texas, up to 69% of the City’s population

is comprised of incarcerated persons. Thompson,

Unlocking Democracy, at 603.

The operation of the usual residence rule has even resulted in the creation of

political districts that would not otherwise exist. For example, at one point, in

upstate New York there were seven rural state-senate districts that would not have

18 Testimony of Dale E. Ho, Assistant Counsel, LDF, Hearing Before the

Kentucky General Assembly Task Force on Elections, Constitutional

Amendments, and Intergovernmental Affairs, 4 (Aug. 23, 2011),

http://www.naacpldf.org/document/dale-ho-testimony-kentucky-prison-based-

gerrymandering (“Kentucky Testimony’’).

8

http://www.naacpldf.org/document/dale-ho-testimony-kentucky-prison-based-gerrymandering

http://www.naacpldf.org/document/dale-ho-testimony-kentucky-prison-based-gerrymandering

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 25 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

been large enough to qualify as individual districts without their prison

populations. Ho, Captive Constituents, at 382. In the absence of prison-based

gerrymandering, the district of New York State Senator Elizabeth O C. Little, in

particular, “face[d] an uncertain future”: her district had 13 prisons, “adding

approximately 13,500 incarcerated ‘residents’” to its purported “population”

without whom “it wouldn’t have enough residents to justify a Senate seat.” 19 *

C. Prison-based gerrymandering transfers political power from

diverse urban communities to largely white, rural areas.

Prisons are disproportionately located in rural areas, where the population

9Q

tends to be predominantly white, especially as compared to that in urban areas.

Between 1995 and 2005—during the heyday of the “war on drugs” and the era of

burgeoning mass incarceration—“a new rural prison ... opened on average every

[15] days in the United States.”21 Only about 20% of the U.S. population resides in

19 Anthony Thompson, Democracy Behind Bars, N.Y. Times (Aug. 5, 2009),

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/06/opinion/06thompson.html.

Kenneth Johnson, Demographic Trends in Rural and Small Town America,

Carsey Inst., Univ. of New Hampshire, at 24, fig. 17 (2006) (“[T]he proportion of

the rural population that is non-Hispanic white (82[%]) is higher than in

metropolitan areas (66[%]).”), http://scholars.unh.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=

1004&context=carsey.

21 David Hamsher, Comment, Counted Out Twice—Power, Representation, &

the “Usual Residence Rule” in the Enumeration o f Prisoners: A State-Based

Approach to Correcting Flawed Census Data, 96 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 299,

311 (2005) (“Counted Out Twice”).

9

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/06/opinion/06thompson.html

http://scholars.unh.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 26 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

rural communities, yet approximately 40% of incarcerated persons nationwide are

imprisoned rurally."

As one example, although 66% of New York State’s prisoners consider New

York City their home, 91% are imprisoned outside of the City in upstate,

predominantly rural areas. Ho, Captive Constituents, at 362. Following the 2000

Census, each of Florida's “ten largest cities lost representation [to rural areas] due

to the Census Bureau’s inmate enumeration method.’’ Stinebrickner-Kauffman,

Counting Matters, at 272-73."'

Thus, by counting prisoners, who are almost always unable to vote at the

prison’s location while incarcerated (infra at 27-28), as “residents” of the rural

areas where they are detained, prison-based gerrymandering significantly enhances * 23

Ho, Captive Constituents, at 362; accord Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman,

Counting Matters: Prison Inmates, Population Bases, and “One Person, One

Vote ”, 11 Va. J. Soc. Pol’y & L. 229, 272 (2004) (“Counting Matters”).

23 The reality that incarcerated people tend to come from urban areas yet are

detained in rural facilities is not isolated to New York and Florida. Cook County,

Illinois, where Chicago is located, is home to 60% of Illinois’s imprisoned

population, but physically houses 1% of the state’s prisoners. Ho, Captive

Constituents, at 362. Los Angeles, California, is home to 34% of California's

imprisoned population, but physically houses 3% of the state’s prisoners. Id.

Baltimore, Maryland is home to 68% of Maryland’s imprisoned population, but

physically houses 17% of the state’s prisoners. Ending Prison-Based

Gerrymandering Would Aid the African-American Vote in Maryland, Prison Pol’y

Initiative (Jan. 22, 2010), http://www.prisonersofthecensus.org/factsheets/md/

africanamericans.pdf.

10

http://www.prisonersofthecensus.org/factsheets/md/

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 27 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

the political power of white, rural residents, at the expense of untold numbers of

city residents, who are disproportionately Black and Latino.

D. Prison-based gerrymandering dilutes the political power of all

communities, including rural ones, without prison facilities.

Prison-based gerrymandering causes impermissible democratic distortions

because it transfers voting and representational strength not only from urban to

rural areas, but also from the parts of a community without a prison to the part of

the same community with a prison. Ho, Captive Constituents, at 356."4 When New

York permitted prison-based gerrymandering, for instance, 50% of the people

drawn into a city council ward in the small upstate community of Rome were

incarcerated, meaning that the actual residents of that ward had twice as much

influence over policies impacting Rome than did those living in other parts of the

city. Wood, Implementing Reform, at 5.

An infamous example of the intra-community imbalances caused by prison-

based gerrymandering comes from Iowa. Following the 2000 Census, the town ol

Anamosa was redistricted into four City Council wards of around 1,370 people

each. Ho, Captive Constituents, at 362. Ward 2, however, held a state prison that 24

24 See also Erika L. Wood, Implementing Reform: How Maryland & New York

Ended Prison Gerrymandering, Demos (2014), http://www.demos.org/publication/

implementing-reform-how-maryland-new-york-ended-prison-gerry mandering

(“Implementing Reform ”).

11

http://www.demos.org/publication/

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 28 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

detained more than 1,320 prisoners, none of whom could vote. Id. The town’s

redistricting plan thus gave the town's approximately 60 actual residents the same

representational power as the over 1,300 people living in each of the other three

wards. Id. at 362-63. The scheme also allowed a man who won only two write-in

votes to be elected to Anamosa’s City Council from Ward 2. Id. at 363.

Critically, representatives of inflated districts, like Ward 2 in Anamosa, are

often unaccountable to the imprisoned population deemed to “reside” within their

boundaries. When asked whether he considered incarcerated people to be his

constituents, Anamosa’s Councilmember from Ward 2 said: ‘“ They don’t vote, so,

I guess, not really.’” Sam Roberts, Census Bureau's Counting o f Prisoners

Benefits Some Rural Voting Districts, N.Y. Times (Oct. 23, 2008),

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/24/us/politics/24census.html. Likewise, a New

York legislator representing a district containing thousands of incarcerated

individuals asserted: “[g]iven a choice between the district’s cows and the district’s

prisoners, he would ‘take his chances’ with the cows, because ‘[t]hey would be

more likely to vote for me.’” Levitt Letter, at 4 r 25

25 See also Todd A. Breitbart, Comment, 2020 Decennial Census Residence

Rule and Residence Situations, Docket No. 150409353-5353-01, at 2 (July 18,

2015), http://www.prisonersofthecensus.Org/letters/T odd_Breitbart_comment_

letter.pdf (legislators “do not offer the prisoners the ‘constituent services’ that they

provide to permanent residents of their districts”).

12

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/24/us/politics/24census.html

http://www.prisonersofthecensus.Org/letters/T

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 29 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

Imprisoned people, instead, are more accurately represented by leaders in

the communities where “they left behind their families and friends, to which they

will eventually return, and where they may once again be voters.” Id. For example,

virtually all of Maryland’s legislators reported that “they would be more likely to

consider persons from their district who are incarcerated elsewhere to be their

constituents.” Howard Brief, at 7 (citing Representative-Inmate Survey, Senate

Education, Health, and Environmental Affairs Committee, Bill File: 2010 Md. S.B.

400, at 22-28). This makes sense, given that these home district politicians are

accountable to the families of incarcerated people, more likely to be attuned to and

affected by the root causes of incarceration, and must absorb the costs of their

incarcerated residents’ reentry.

In short, prison-based gerrymandering is not only wrong, but also unlawful,

because the one-person, one-vote principle is meant to “prevent debasement of

voting power and diminution of access to elected representatives,” Kirkpatrick v.

Preisler, 394 U.S. 526, 531 (1969), and prison-based gerrymandering causes both

of these harms.

E. The Supreme Court repeatedly has held that distortions like those

caused by prison-based gerrymandering are unconstitutional.

Prison-based gerrymandering “[d]ilut[es] the weight of votes because of

place of residence.” Reynolds, 377 U.S. at 566. The Supreme Court has held that

such residence-based distortions “impair[] basic constitutional rights under the

13

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 30 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

Fourteenth Amendment just as much as invidious discriminations based upon

factors such as race or economic status." Id. (citations omitted).

In Gray v. Sanders, 372 U.S. 368 (1963), the Supreme Court struck down a

voting scheme that assigned greater electoral power to less densely populated rural

areas, to the detriment of urban voters. In so holding, the Court compared the

urban-rural imbalance it invalidated to race-discrimination in voting: “If a State in

a statewide election weighted ... the white vote more heavily than the Negro vote,

none could successfully contend that that discrimination was allowable. How then

can one person be given twice or 10 times the voting power of another person in a

statewide election merely because he lives in a rural area or because he lives in the

smallest rural county?” Id. at 379 (citation omitted).

In Reynolds, the Court reiterated that “the fact that an individual lives here

or there is not a legitimate reason for overweighting or diluting the efficacy of his

vote.” 377 U.S. at 567. Debasing a citizen's right to vote because of where he

lives, the Court said, violates “the basic principle of representative government.”

Id. Under the Equal Protection Clause, “the weight of a citizen’s vote cannot be

made to depend on where he lives.” Id.

Prison-based gerrymandering runs counter to “[t]his ... clear and strong”

command, id. at 568, and where (as here) the practice causes one-person, one-vote

distortions, it must be held unconstitutional. Indeed, there are myriad examples of

14

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 31 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

districting schemes across the country that raise constitutional concerns because

they pad districts with incarcerated populations to satisfy the Court’s general rule

that population deviations among legislative districts within plus-or-minus 10% are

presumptively constitutional. See Brown v. Thomson, 462 U.S. 835, 852 (1983). To

name just two:

• Following the 2000 Census, four Michigan senate

districts and five house districts met federal minimum

population requirements “only because they claim

prisoners as constituents.” Heather Ann Thompson,

How Prisons Change the Balance o f Power in

America, Atlantic (Oct. 7, 2013),

http://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2013/10/

how-prisons-change-the-balance-of-power-in-

america/280341 / (“T/ow Prisons Change”).

• In Pennsylvania, “no fewer than eight state legislative

districts would [fail to] comply with the federal ‘one

person, one vote’ civil rights standard if non-voting

state and federal prisoners in those districts were not

counted as district residents.” Id.

The same is true here. “When Cranston drew its city ward boundaries in

2012, it included the entire prison population in Ward Six, where the [Adult

Correctional Institution] is ... located.” Mem. & Order, ECF No. 35, at 2 (May 24,

2016). Cranston contends that “the total maximum deviation among the population

of the six wards is less than [10%] percent.” Id. “However, i f ... the prisoners are

subtracted from Ward Six’s population, its total population is reduced to 10,209.

Without the prison population, the deviation between the largest ward and Ward

15

http://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2013/10/

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 32 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

Six is approximately 35%.” Id. at 2-3; cf. Br. of Pis.-Appellees 10, 19 & n.7

(calculating deviation as approximately 28%).

Cranston’s use of prison-based gerrymandering is thus unconstitutional. As

the Supreme Court has long recognized: ‘i f districts of widely unequal population

elect an equal number of representatives, the voting power of each citizen in the

larger constituencies is debased and the citizens in those districts have a smaller

share of representation than do those in the smaller districts,” which is

constitutionally impermissible. Bd. o f Estimate o f City o f New York v. Morris, 489

U.S. 688, 693-94 (1989); see also Mem. & Order, ECF No. 35, at 7 (May 24,

2016) (district court recognized it is “constitutionally unsustainable to draw district

lines so that ‘the votes of citizens in one region would be multiplied by two, five,

or 10 times for their legislative representatives’” (citing Reynolds, 377 U.S. at

563).

A total population deviation such as in Cranston (between 28 and 35%)—

and, in fact, any deviation larger than 10%—“creates a prima facie case of

discrimination and therefore must be justified by the State.” Voinovich v. Quilter,

507 U.S. 146, 161 (1993). Cranston, however, cannot offer any legitimate state

interest to justify its engagement in discriminatory prison-based gerrymandering;

the practice, as a policy matter, makes no sense at all. Supra at 3-6. Especially

given that prison-based gerrymandering also systematically dilutes the

16

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 33 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

representation of identifiable racial groups, infra at 17-29, and thus has a particular

“taint of arbitrariness or discrimination,” Roman v. Sincock, 377 U.S. 695, 710

(1964), this Court should hold that Cranston is not entitled to engage in prison-

based gerrymandering.

II. PRISON-BASED GERRYMANDERING DISPROPORTIONATELY

HARMS VOTERS OF COLOR AND THE COMMUNITIES IN

WHICH THEY LIVE.

A. Prison-based gerrymandering disempowers Black and Latino

communities.

Black and Hispanic people are disproportionately incarcerated in our

nation’s prisons. Nationwide, Black people make up 13.3% of the general

population, but 37.7% of the federal and state prison population.26 Hispanic people,

who are 17.6% of the U.S. population, are nearly twice as likely to be imprisoned

as are white people.27 Yet, prisons typically are located in rural areas that tend to

be overwhelmingly white. Supra at 9-11.

26 U.S. Census Bureau, Quick Facts, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/

PST045215/00 (last visited Aug. 25, 2016); Federal Bureau of Prisons, Inmate

Race (last updated Feb. 21, 2015), http://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_

inmaterace.jsp.

27 U.S. Census Bureau, Quick Facts, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/

PST045215/00 (last visited Aug. 25, 2016); Leah Sakala, Breaking Down Mass

Incarceration in the 2010 Census: State-by-State Incarceration Rates by

Race/Ethnicity, Prison Pol’y Initiative (May 28, 2014), http://www.prisonpolicy.

org/reports/rates.html.

Many other facts demonstrate the deeply problematic relationship between

race and our criminal system. For example, Black men are more than six times as

17

https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/

http://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_

https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/

http://www.prisonpolicy

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 34 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

Today, there are more than 200 counties where the proportion of

incarcerated Black people is over ten times larger than the proportion of Black

people in the surrounding county. Levitt Letter, at 3 & n.5. Likewise, there are

more than 40 counties where the proportion of Latino people in the incarcerated

population is over ten times larger than the proportion of Latino people in the

surrounding county. Id.

When combined with the racially disparate rates of incarceration, “the

enduring and troubling trend of building ... prisons in communities that are very

different demographically from the communities of people confined in the prisons’

means that the vote dilution and other harms of prison-based gerrymandering

uniquely fall on minority groups. Brief of DARE, at *10.28 That is, “[t]he strategic

placement of prisons in predominantly white rural districts often means that these

districts gain more political representation based on the disenfranchised people in

likely as white men to be incarcerated nationwide. Bruce Drake, Incarceration gap

widens between whites and blacks, Pew Research Ctr. (Sept. 6, 2013),

http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/09/06/incarceration-gap-between-

whites-and-blacks-widens/.

Prison-based gerrymandering thus potentially violates not only the Equal

Protection Clause, but also Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits any

“voting ... standard, practice, or procedure ... which results in a denial or

abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of

race or color.” 52 U.S.C. § 10301. Section 2, accordingly, prohibits voting

practices— like prison-based gerrymandering—that have a dilutive “effect” on

minority voting strength. See Bartlett v. Strickland, 556 U.S. 1, 10-11 (2009).

18

http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/09/06/incarceration-gap-between-whites-and-blacks-widens/

http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/09/06/incarceration-gap-between-whites-and-blacks-widens/

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 35 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

prison, while the inner-city” and largely minority “communities these prisoners

come from suffer a proportionate loss of political power and representation.” Lani

Guinier & Gerald Torres, The Miner’s Canary: Enlisting Race, Resisting Power,

and Transforming Democracy 189-90 (2002).

The facts on the ground in New York illustrate exactly how the combination

of disparate incarceration rates and prison-based gerrymandering can significantly

dilute the political power of Black and Latino people relative to white people: 82%

of the state’s prison population is Black or Latino, yet “98% ... of [its] prison cells

are located in state Senate districts that are disproportionately White for the

state.”* 30 As a result, prison-based gerrymandering, when allowed in New York,

inflated the population of largely white districts using the bodies of incarcerated

people of color.

That result is especially troubling given the well-documented and now

commonly recognized racial and economic inequalities embedded in our criminal

system. See, e.g., Exec. Office of the President, Economic Perspectives on

Incarceration and the Criminal Justice System (2016), https://www.whitehouse.

gov/sites/default/files/page/files/20160423 ceajncarceration criminalJustice.pdf;

Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of

Colorblindness (2010).

30 Peter Wagner, 98% o f New York’s Prison Cells Are in Disproportionately

White Senate Districts, Prison Pol’y Initiative (Jan. 17, 2005),

http://www.prisonersofthecensus.org/news/2005/01/17/white-senate-districts/; see

also Nathaniel Persily, The Law o f the Census: How to Count, What to Count,

Whom to Count, and Where to Count Them, 32 Cardozo L. Rev. 755, 787 (2011).

19

https://www.whitehouse

http://www.prisonersofthecensus.org/news/2005/01/17/white-senate-districts/

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 36 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

The same distortions persist in New England. In Connecticut, for example,

Black and Latino people make up only 19% of the state’s population, but more

than 70% of its prisoners.31 Nevertheless, 75% of the state’s prison cells are

located in disproportionately white state house districts. Id.

Rhode Island’s prisons exhibit similar racial imbalances. Black people

constitute 7.5% of Rhode Island’s population, but 28.7% of its prisoners. Aden,

Rhode Island Letter, at 1-2. Latino people comprise 13.6% of Rhode Island’s

population, but 19.6% of its prisoners. Id. at 2. Thus, the dilution of voting and

representational power caused by prison-based gerrymandering is felt most

strongly in communities of color in Rhode Island too.

Prison-based gerrymandering is especially harmful to Black and Latino

communities at the local level because local elective districts have smaller total

population numbers and the presence of a large prison can have a greater skewing

effect. According to 2010 Census Data, as a result of the “usual residence rule” and

its application to prison populations, in 161 counties more than half of the African-

31 Ending Prison-Based Gerrymandering Would Aid the African-American and

Latino Vote in Connecticut, Prison Pol’y Initiative & Common Cause Conn.

(2010), http://www.prisonersofthecensus.org/factsheets/ct/CT_AfricanAmericans_

Latinos.pdf.

20

http://www.prisonersofthecensus.org/factsheets/ct/CT_AfricanAmericans_

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 37 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

American residents are incarcerated. 2 Likewise, one study found “208 counties

where the portion of the county that was Black was at least 10 times smaller than

the portion of the prison that was Black.” Wagner & Kopf, Racial Geography. In

Brown County, Illinois, for example, all but five of the County’s 1,265 African-

American individuals counted as “residents” of that community (a whopping

99.6%) are imprisoned. Hamsher, Counted Out Twice, at 315.

The localized harms of prison-based gerrymandering on Latino individuals

are similarly stark. In 2010, for example, “there were 20 counties spread across 10

states where the Latino population that is incarcerated outnumbers those who are

free.” Wagner & Kopf, Racial Geography. There are also “a substantial number of

counties where the incarcerated populations are largely Latino but where Latinos

are only a very small portion of the county’s non-incarcerated population[.]” Id.

And “there are many counties”—dispersed throughout the country—“where

virtually the entire Latino population is incarcerated.” Id.

In 2010, Maryland enacted its “No Representation Without Population

Act”—prohibiting prison-based gerrymandering—to counteract these invidious 32

32 Peter Wagner & Daniel Kopf, The Racial Geography o f Mass Incarceration

(July 2015), http://www.prisonpolicy.org/racialgeography/report.html (“Racial

Geography”).

21

http://www.prisonpolicy.org/racialgeography/report.html

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 38 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

racial effects.’’ See Fletcher v. Lamone, 831 F. Supp. 2d 887, 893 (D. Md. 2011),

a ff’d, 133 S. Ct. 29 (2012). The state acknowledged that prison-based

gerrymandering disproportionately harmed minority communities, because “while

the majority of [Maryland’s] prisoners come from African-American areas, the

state’s prisons are located primarily in the majority white ... [districts.” Id. The

Act thus “empowered] all voters, including African-Americans, by counteracting

dilution of votes and better aligning districts with the interests of their voting

constituents.” Id. at 908 (Williams, J., concurring).

For the same reasons, and because such legislative efforts in Rhode Island

have failed, this Court should not permit the City of Cranston’s use of prison-based

gerrymandering to stand.

B. Prison-based gerrymandering harms communities of color not

only by diluting their voting and representational strength, but

also by impeding remedial redistricting and criminal justice

reform.

Prison-based gerrymandering prevents the enactment of policies that benefit

Black and Latino communities and encourages the entrenchment of laws that are

harmful to them.

Three other states— Delaware, New York, and California—and over 200

local jurisdictions also have acted to prevent prison-based gerrymandering. Local

Governments That Avoid Prison-Based Gerrymandering, Prison Pol'y Initiative

(last updated May 13, 2016), http://www.prisonersofthecensus.org/local/; Wood,

Implementing Reform, at 7.

22

http://www.prisonersofthecensus.org/local/

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 39 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

For instance, prison-based gerrymandering blocks communities of color

from electing their candidates of choice and thus impedes efforts to remedy

discrimination through redistricting. The case of Somerset County, Maryland is

illustrative. Until 2010, Somerset voters had never elected an African-American

person to serve in County government. Peter Wagner, Breaking the Census:

Redistricting in an Era o f Mass Incarceration, 38 Wm. Mitchell L. Rev. 1241,

1246 (2012) (“Breaking the Census”). Following voting rights litigation in the

1980s, the County agreed to create one district in which Black voters comprised

the majority of the population to provide them with the opportunity to elect their

preferred candidates. Id. However, a prison was built in the district, and the 1990

Census was conducted after its first remedial election—leaving only a small

African-American voting-eligible population in the district, and making it difficult

for African-American voters to elect their candidates of choice. Id. Had the prison

population not been included in the district's population count, African-American

voters would have had an opportunity to elect their preferred candidates. See id.

Prison-based gerrymandering also “incentiviz[es] opposition to criminal

justice reforms that would decrease reliance on mass incarceration,” Ho, Captive

Constituents, at 356—a systemic problem that inflicts significant harm on people

of color, in particular. Since the political power of areas where prison facilities are

located “depends in some measure on a continuing influx of prisoners, legislators

23

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 40 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

from prison districts have a strong incentive to oppose criminal justice reforms that

might decrease incarceration rates.” Id. at 363-64. Due to prison-based

gerrymandering, “political power is shifted from those communities most afflicted

by crime to those communities most interested in gaining from incarceration—

potentially at the expense of any alternative means of retribution, crime prevention,

drug treatment, or rehabilitation.” Hamsher, Counted Out Twice, at 310; see also

Andrea L. Maddan, Enslavement to Imprisonment: How the Usual Residence Rule

Resurrects the Three-Fifths Clause and Challenges the Fourteenth Amendment, 15

Rutgers Race & L. Rev. 310, 326 (2014) (“Since apportionment is also about

resources, the repercussions of moving money and power away from the

hometown of the prisoner means less resources to foster the societal re-integration

that he or she deserves.”). “The result is a positive feedback loop: mass

incarceration results in districts where the representatives are incentivized to favor

policies that favor even more mass incarceration.” Ho, Captive Constituents, at

364.

As an example, “the two state senators in New York who led the opposition

to efforts to reform New York’s harsh Rockefeller drug sentencing laws

represented districts that [detained] more than 17% of the state’s prisoners.” Id.

“The inflated populations of these senators’ districts gave them little incentive to

consider or pursue policies that might reduce the numbers of people sent to prison

24

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 41 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

or the length of time they spend there.” Wagner, Breaking the Census, at 1244. 4

One “representative” candidly asserted that “he was glad that the almost 9,000

people confined in his district cannot vote because ‘they would never vote for

me.’” Id.

Prison-based gerrymandering thus, itself, may prevent many jurisdictions

from democratically prohibiting the practice. Although some states and localities

have made progress towards prohibiting prison-based gerrymandering, supra at 21-

22 & n.33, it is critical that where they have not, federal courts intervene to correct

this constitutional problem. See Calvin v. Jefferson Cnty. Bd. o f Comm rs, 2016

WL 1122884 (N.D. Fla. Mar. 19, 2016) (holding that county’s use of prison-based

gerrymandering violated the Equal Protection Clause). Otherwise, prison-based

gerrymandering and its pernicious effects are likely to remain entrenched. See

Thompson, How Prisons Change. 34

34 At a time when communities of color are demanding recognition that their

lives matter, practices like prison-based gerrymandering that disincentivize the

reformation of drug laws and mass incarceration must be curbed. See Ho, Captive

Constituents, at 361 & n.31. And, as Justice Sotomayor recently acknowledged:

“We must not pretend that the countless people who are routinely targeted by

police are ‘isolated.’ They are the canaries in the coal mine whose deaths, civil and

literal, warn us that no one can breathe in this atmosphere.” Utah v. Strieff No. 14-

1373 (U.S. June 20, 2016), slip op. 12 (Sotomayor, J„ dissenting).

25

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 42 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

This is yet another reason why this Court should prohibit Cranston from

using prison-based gerrymandering—it is a practice that reinforces the political

disempowerment and mass incarceration of Black and Latino people.

C. The race-based harms of prison-based gerrymandering resemble

the unconscionable three-fifths compromise.

Prison-based gerrymandering is particularly troubling when considered in

light of our nation’s history. Arguably, “[t]here has only been one other instance in

American history where disfranchised, captive populations of people of color were

used to artificially inflate political strength: the infamous three-fifths compromise

[that was] enshrined in Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution” during slavery. Ho,

Captive Constituents, at 362 (citing U.S. Const, art. 1, § 2, cl. 3, amended by U.S.

Const, amend. XIV). Today, “[wjhere people of color are inflating the population

numbers of largely rural areas and shifting resources to those areas and away from

the urban areas where those people of color are likely to return[,] the analogy to the

Three Fifths clause is all the more compelling.” Thompson, Unlocking Democracy,

at 602. This history offers still another reason to prohibit prison-based

gerrymandering: it is “nothing short of perverse” that, as during slavery,

26

Case: 16-1692 Document: 00117050000 Page: 43 Date Filed: 08/31/2016 Entry ID: 6029646

imprisoned people's “bodies are used to over-inflate the population of a prison

* 35jurisdiction.”

In conjunction with the harms of prison-based gerrymandering, Black people

today also disproportionately bear the brunt of felon disfranchisement laws

designed to similarly constrict the political power of communities of color. LDF,

Free the Vote: Unlocking Democracy in the Cells and on the Streets,

http://www.naacpldf.org/files/publications/Free%20the%20Vote.pdt (“Free the

Vote”). These laws were passed after the Civil War and the end of slavery for the