Price v. The Civil Service Commission of Sacramento County Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

June 9, 1978

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Price v. The Civil Service Commission of Sacramento County Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amici Curiae, 1978. 85164681-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/51cc923e-6ff6-4252-8c2b-6d9886f5299b/price-v-the-civil-service-commission-of-sacramento-county-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

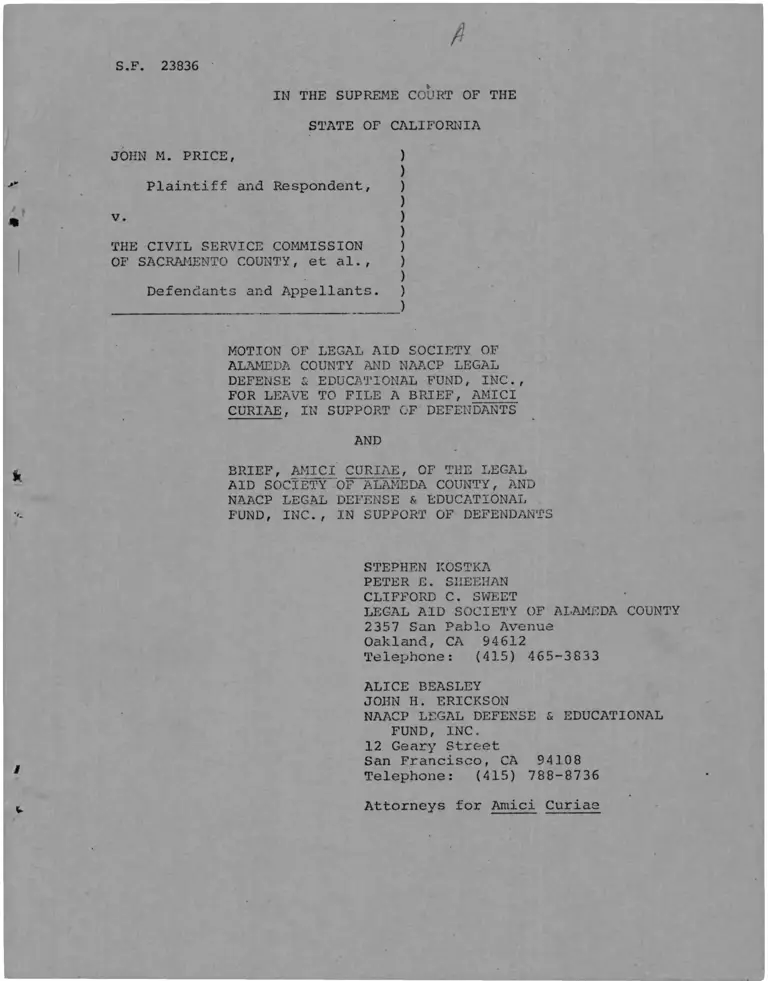

S.F. 23836

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE

STATE OF CALIFORNIA

JOHN M. PRICE, )

)

Plaintiff and Respondent, )

)

v. )

)

THE CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION )

OF SACRAMENTO COUNTY, et al., )

)

Defendants and Appellants. )

______ )

MOTION OF LEGAL AID SOCIETY OF

ALAMEDA COUNTY AND NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

FOR LEAVE TO FILE A BRIEF, AMICI

CURIAE, IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANTS"

AND

BRIEF, AMICI CURIAE, OF THE LEGAL

AID SOCIETY OF ALAMEDA COUNTY, AND

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC., IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANTS

STEPHEN KOSTKA

PETER E. SIIEEHAN

CLIFFORD C. SWEET

LEGAL AID SOCIETY OF ALAMEDA COUNTY

2357 San Pablo Avenue

Oakland, CA 94612

Telephone: (415) 465-3833

ALICE BEASLEY

JOHN H. ERICKSON

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC.

12 Geary Street

San Francisco, CA 94108

Telephone: (415) 788-8736

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

S.F. 23836

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE

STATE OF CALIFORNIA

JOHN M. PRICE, )

)

Plaintiff and Respondent, )

)

v. )

)

THE CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION )

OF SACRAMENTO COUNTY, et al., )

)

Defendants and Appellants. )

_______________________________)

MOTION OF LEGAL AID SOCIETY OF ALAMEDA

COUNTY AND THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., TO FILE A BRIEF

AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANTS

1. The Legal Aid Society of Alameda County is a California

non-profit corporation established to represent low-income

persons in civil matters. In recent years the Legal Aid Society

of Alameda County has become increasingly involved in the area

of equal employment opportunity. The Legal Aid Society has

filed and successfully prosecuted numerous cases under the

California and Federal statutes guaranteeing equal employment

opportunity.

2. The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. is

a non-profit corporation established to assist Black persons to

secure their legal rights by the prosecution of lawsuits. Its

charter declares that its purposes include rendering legal

services gratuitously to Black persons suffering injustice by

reason of racial discrimination. For many years attorneys of

- 1 -

the Legal Defense Fund have represented parties before the

appellate courts of this nation in litigation involving a

variety of race discrimination issues in the field of employment

discrimination. See, e,g., Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S.

424 (1971); Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405

(1975); Franks v. Bowman, 424 U.S. 747 (1976).

3. The issues raised by this case are matters of first

impression and of great significance to all public agencies

and to all minority persons seeking public employment in this

state. Affirmance of the court's decision would effectively

halt, contrary to the intent of Congress, the adoption by public

employers of voluntary programs designed to remedy the effects

of past discrimination. The viewpoints of amici may be useful

to the court in determining the important matters at stake.

4. Amici are familiar'with the questions involved in this

case and the scope of their presentation, and counsel for

defendants welcome the filing of this brief. Amici believe

that there is a need for additional argument on the following

points:

A. Rule 7.10 and defendant's Order are permissible

voluntary compliance authorized and encouraged by Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended;

B. Rule 7.10 and defendant's Order are constitutional

because they serve the state's compelling interest in remedying

the effects of past discrimination and are reasonably related

to the accomplishment of that goal.

-2

WHEREFORE, we respectfully move the court to permit the

filing of the accompanying brief, amici curiae, in support of

defendants the Civil Service Commission, and the Board of

r- Supervisors, of Sacramento County.

Dated: June , 1978

Respectfully submitted,

ALICE BEASLEY

JOHN H.

STEPHEN

CLIFFORD

PETER E.

ERICKSON

KOSTKA

i C. SWEET

SHEEHAN

ALICE BEASLEY

JOHN H. ERICKSON

STEPHEN KOSTKA

PETER E. SHEEHAN

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

-3

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ii

I. INTRODUCTION 1

II. MINORITY EMPLOYMENT PROGRAMS SUCH AS DEFENDANT'S

ARE AUTHORIZED BY TITLE VII 6

A. Rule 7.10 and Defendant's Order Do Not

Violate Section 703(a)(2) of Title VII 8

B. Rule 7.10 and Defendant's Order Do Not

Violate Section 703 (j) of Title VII 11

C. The Remedial Authority Granted by Section

706(g) Is Not Limited to Cases of

Intentional Discrimination 17

III. DEFENDANT IS AUTHORIZED BY TITLE VII TO ADOPT

ITS MINORITY EMPLOYMENT PROGRAM VOLUNTARILY 18

IV. DEFENDANT'S MINORITY EMPLOYMENT’ PROGRAM IS

CONSTITUTIONAL BECAUSE IT IS BASED ON EVIDENCE

OF PRIOR DISCRIMINATION AND IS REASONABLY

RELATED TO THE REMOVAL OF THE EFFECTS OF

DISCRIMINATION 24

V. CONCLUSION 36

TABLE OF CONTENT^

i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405 (1975)

Alexander v. Gardner Denver Co.,

415 U.S. 36 (1974)

Associated Gen. Contractors of Mass., Inc. v.

Altchuler, 490 F.2d 9 (1st Cir. 1973)

cert, denied 416 U.S. 957 (1974)

Bakke v. Regents of the University of California,

18 Cal.3d 34, cert. granted, 420 U.S. 1090 (1977)

Barnett v. International Harvester,

11 EPD par. 10,846 (W.D. Tenn. 1976)

Boston Chapter NAACP v. Beecher,

504 F.2d" 1017 (1st Cir. 1974)' 13,

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc, v. Members of Bridgeport

Civil Serv. Comm'n., 482 F.2d 1333 (2nd Cir. 1973) 27,

Carter v. Gallagher,

452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. 1971)

Castro v. Beecher,

459 F.2d 725 (1st Cir. 1972)

Constructors Assoc, of Western Pa. v. Kreps,

441 F.Supp. 936 (W.D. Pa. 1977) 27, 28,

Contractors Ass'n. of Eastern Pa. v. Secretary

of Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (3rd Cir. 1971),

cert, denied, 404 U.S. 954 (1971)

Crawford v. Board of Education,

17 Cal.3d 280 (1976)

Davis v. County of Los Angeles,

566 F.2d 1334 (9th Cir. 1977)

EEOC v. American Telephone and Telegraph Co.,

556 F .2d 167 (3rd Cir. 1977) 12,

Erie Human Relations Commission v. Tullio,

493 F.2d 371 (3rd Cir. 1974)

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

424 U.S. 747 (1976) 10,

Page(s)

18, 19

19

passim

passim

19

16, 18

29, 31

passim

9, 27

29 , 30

passim

passim

10, 31

16, 20

26, 27

11, 12

l i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (CON 1T .)

Cases Page(s)

Germann v. Kipp,

429 F.Supp. 1323 (W.D. Mo. 1977) 27, 28

Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424 (1971) 17

Jackson v. Pasadena City School Dist.,

59 Cal.2d 876 (1963) 24

Joyce v. McCrane,

320 F.Supp. 1284 (D.N.J. 1970) 19, 21, 27

Lige v. Town of Montclair,

367 A.2d "833 (N.J.S.Ct. 1976) 1, 31

Local 53 of Int. Ass'n. of Heat & Frost I. & A.

Wkrs. v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (5th Cir. 1969) 13, 14, 31

Loving v. Virginia,

388 U.S. 1 (1967) 24

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co.,

427 U.S. 273 (1976) ‘ ..." 9

Morrow v. Crisler,

491 F.2d 1053 (5th Cir.)(en banc), cert, denied,

418 U.S. 895 (1974) 10, 25, 27

Mulkey v. Reitman,

64 Cal.2d 529 (1966) aff'd Reitman v. Mulkey,

387 U.S. 369 (1967) 24

NAACP v. Allen,

493 F.2d 614 (5th Cir. 1974) 22, 27, 28, 29

Oatis v. Crown Zellerback,

398 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1968) 19

Oburn v. Shapp,

521 F.2d 142 (3rd Cir. 1975) 20

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co.,

535 F.2d 257 (4th Cir. 1976) 9, 13

Patterson v. Newspaper and Mail Deliverers Union,

514 F.2d 767 (2nd Cir. 1975) 20

People v. Beadley,

1 Cal.3d 80 (1969) 9

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (CONTINUED)

Cases Page(s)

Perez v. Sharp,

32 Cal.2d 711 (1948) 24

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co.,

494 F.2d 211 (3th Cir. 1974) 19

Ramirez v. Brown,

9 Cal.3d 199 (1973) rev'd sub nom Richardson v.

Ramirez, 418 U.S. 24 (1974) 28

R.I. Chapter, Associated Gen. Contractors v. Kreps,

446 F.Supp. 553 (D.R.I. 1978) 27, 28, 29, 30

Rios v. Enterprise Ass'n. Steamfitters,

Local 638, 501 F.2d 622 (2nd Cir. 1974) 9, 13

Rosenstuck v. Bd. of Governors of Univ. of N.C.,

423 F.Supp. 1321 (M.D.N.C. 1976) 28

San Francisco Unified School District v. Johnson,

3 Cal.3d 937 (1971) 25

Southern Illinois Builders' Ass'n. v. Ogilvie,

471 F.2d 680 (7th Cir. 1972) 21, 26, 27, 31

Southern Pac. Transportation Co. v. Public

Utilities Com., 18 Cal.3d 308 (1976) 27

Swann v. Charlotte-Mechlenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) 22

United Jewish Organizations v. Carey,

430 U.S. 144 (1977) 25, 28

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, Inc.,

517 F.2d 826 (5th Cir. 1975) 19, 20

United States v. City of Chicago,

549 F.2d 415 (7th Cir. 1977) 10

United States v. Elevator Constructors, Local 5,

538 F.2d 1012 (2d Cir. 1974) 9, 12

United States v. IBEW, Local 38,

428 F.2d 144 (6th Cir.), cert, denied,

400 U.S. 943 (1970) 10, 12, 14

iy

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (CON'T.)

Cases

United States v. Ironworker, Local 86,

443 F.2d 544 (9th Cir.), cert, denied,

404 U.S. 984 (1971)

United States v. Sheetmetal Workers, Local 36,

416 F.2d 123 (8th Cir. 1969)

Vulcan Society v. Civil Service Commission,

490 F.2d 387 (2nd Cir. 1973)

Washington v. Davis,

426 U.S. 229 (1976)

Weiner v. Cuyahoga Community College Dist.,

19 Ohio St. 2d 35, 249 N.E.2d 907 (1969), cert,

denied, 396 U.S. 1004 (1970)

Federal Statutes

Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C.- §2000e et seq.)

Other Materials

Preferential Law School Admissions and the Equal

Protection Clause, 22 U.C.L.A. L.Rev. 343 (1974)

Preferential Treatment and Equal Opportunity,

55 Ore.L.Rev. 53 (1976)

Subcommittee on Labor of the Senate Committee on

Labor and Public Welfare, Legislative History of

the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 (1972)

passim

14

27

17

21

passim

25

29, 35

15, 16

Page(s)

v

S.F. 23836

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE

STATE OF CALIFORNIA

JOHN M. PRICE, )

)

Plaintiff and Respondent, )

)

v. )

)

THE CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION )

OF SACRAMENTO COUNTY, et al., )

)

Defendants and Appellants. )

)

BRIEF, AMICI CURIAE, OF THE LEGAL

AID SOCIETY OF ALAMEDA COUNTY, AND

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC., IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANTS

I

INTRODUCTION

The issue presented by this case "concerns the validity

of an important tool in the arsenal of legal remedies for racial

discrimination." (Lige v. Town of Montclair, 367 A.2d 833, 845

(N.J.S.Ct. 1976) (Pashman, J., dissenting)). The court must

decide whether a public employer may voluntarily adopt a racial

hiring ratio — ̂ ("minority employment program") to remedy the

1/ The Court of Appeal characterized the challenged provision

as "establishing a minority quota hiring system" (Decision, here

after "D", at pg. 1, attached to defendants' Petition for Hearing

as the Appendix). However, it must be stressed that the court

clearly erred in characterizing the program as a quota. As noted

by one commentator the "distinction between a goal and a quota

can be simply stated . . . [A] goal simply declares an objective

which will be met only if a sufficient number of qualified

applicants apply, while a quota specifies the number to be

[Continued on following page]

-1

effects of its past discriminatory hiring practices and neutralize

the effects of its present discriminatory hiring practices. Both

of the courts below concluded that an employer could never

lawfully adopt such a program.

The minority employment program at issue here was created

by an order of defendant Sacramento County Civil Service Commission

(hereafter "defendant"), issued pursuant to Rule 7.10 of the

Commission, which allows, but does not require, defendant to

1/ (Continued from previous page)

admitted from a given group regardless of the pool of qualified

applicants." O'Neill, Discriminating Against Discrimination

(1975), p. 68. Under such a definition the program challenged

here would be a goal as it is clearly applicable only if there

are qualified minorities available, i.e., those who passed the

examination given by the county for the position (Rule 7.10

subdivision (g) set forth at CT 66).

Of even more importance, however, is the court's incorrect

characterization of the program as creating a preference for

minorities (D, pg. 2). Because the eligibility lists are based

on the results of an unvalidated examination the program cannot

be said to create a preference or quota. As pointed out by the

Eighth Circuit:

As the tests are currently utilized,

applicants must attain a qualifying score

in order to be certified at all. They are

then ranked in order of eligibility according

to their test scores. Because of the absence

of validation studies on the record before us,

it is speculative to assume that the qualify

ing test, in addition to separating those

applicants who are qualified from those who

are not, also ranks qualified applicants with

precision, statistical validity, and predictive

significance. [citations deleted] Thus, a

hiring remedy based on an alternating ratio

such as we here suggest will by no means

necessarily result in hiring less qualified

minority persons in preference to more

qualified white persons.

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d

315, 331 (8th Cir. 1971)

[Emphasis added]

2-

mandate county agencies to adopt an alternating ratio system

for employment of minorities. After a number of hearings the

Commission issued an order with findings (CT 17-22) directing

plaintiff John M. Price, the District Attorney of Sacramento

County (hereafter "plaintiff") to make appointments in the

Attorney I (the entry level) classification in his office "on

the basis of an alternating ratio of 2:1 so that at least one

minority person is appointed for every two non-minority persons"

until the percentage of minorities in the Attorney I and

Attorney II classifications reached 8 percent (CT 21).

Plaintiff then initiated this litigation. The trial court

ruled in plaintiff's favor finding Rule 7.10 and the Order

unconstitutional on their face because they discriminated

against non-minority applicants (CT 159-163). The Court of

Appeal for the Third District affirmed, but did not reach the

constitutional issue. It voided the challenged order as being

in conflict with Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and

2 /a Sacramento County Charter provision. —

Before turning to the merits, amici wish to note several

aspects of the rule which are important in evaluating its validity.

2/ Amici do not address the County Charter issue. They agree

with the Court of Appeal holding that "directions and delegations

of authority [for voluntary action] emanating from Title VII

prevail over inhibitions in state law and county charter" (D. at

9). It should also be noted that a provision similar to the

above County Charter section was held to not void a minority

quota program in Associated Gen. Contractors of Mass., Inc, v.

Altchuler, 490 F.2d 9, 20-21 (1st Cir. 1973), cert, denied

416 U.S. 957 (1974).

-3-

First, it is discretionary and is only implemented after a

public hearing is held and findings made on a number of issues.—

Second, the purpose of the rule is to remedy the effects of past

discrimination by the employer (Rule 7.10 subdivision (a)).

Third, defendant has interpreted the rule as being applicable

only where less drastic remedies have failed and there would

not be a significant increase in minority employment absent

implementation of the rule (see Findings XIII and XV, CT 19, 20).

Finally, any order issued pursuant to the rule may be modified

or rescinded by defendants at the request of any interested

4/person (Rule 7.10 subdivision (f)). —

3 /

3/ In addition to findings concerning the failure of less drastic

remedies and the lack of significant increase in minority employ

ment absent implementation of the rule, discussed infra, the

rule requires that findings be made as to whether (1) the number

of minority personnel is disproportionately low in relation to

the relevant population; (2) this low number "was caused by

discriminatory employment practices" (7.10 subdivision (c)(2));

and (3) it is feasible to adjust the disproportionate representa

tion by implementing the rule.

4/ The full text of the relevant subdivision of the rule provides

An order may be rescinded or revised from .

time to time by the Commission as it deter

mines to be necessary or appropriate. Such

action may be taken by the Commission on

its own motion or at the request of any

interested person. In determining whether

to rescind or revise an order, the Commis

sion may consider any relevant information

including but not limited to the needs of

the service, changed circumstances, problems

encountered in implementing the order, and

information which was not previously con

sidered by the Commission.

Rule 7.10 subdivision (f)

-4-

It is also important to recognize the fundamental

difference between the special admission program at issue in

Bakke v. Regents of the University of California, 18 Cal.3d 34,

cert, granted, 420 U.S. 1090 (1977) and the hiring system in

5 /this case. — In Bakke this court was careful to point out

that there was "no evidence in the record to indicate that the

University has discriminated against minority applicants in the

past" (Id. at 59). In contrast the record here demonstrates

that both defendant and the district attorney's office had

discriminated in the past. Indeed Rule 7.10 was adopted for the

explicit purpose of providing one procedure (among others) to

remedy the effects of such prior unlawful discrimination. Thus,

whatever the eventual outcome of Bakke, the issue of a race

conscious program to remedy society's, rather than a particular

employer's, discrimination is simply not presented by this

case.—^ Rather this case must be viewed as testing the lawful

ness of a public employer's voluntary adoption of a race conscious

program to remedy its past discrimination.

5/ TVmici write this brief on the assumption that Bakke will be

affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court. - Should it be reversed the

validity of the challenged rule would appear to be assured.

6/ Indeed the Bakke decision explicitly recognized the distinction

between the adoption of race conscious programs by agencies that

have not themselves engaged in prior discriminatory practices

and by agencies which have (Bakke, supra, 18 Cal.3d at 57-59).

-5-

II

MINORITY EMPLOYMENT PROGRAMS SUCH AS

DEFENDANT'S ARE AUTHORIZED BY TITLE VII

Under the 1972 amendments to section 701 of the Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the antidiscrimination provisions

of the Act were extended to apply to state and local governments.

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(a). As the Court of Appeal correctly noted,

Rule 7.10 and defendant's order creating the minority employment

program represent voluntary action by a local governmental agency

to satisfy the requirements of Title VII.(D. at 9-10) Based

upon the language of the statute and its reading of the legisla

tive history of Title VII, the Court of Appeal concluded, however,

that the use of a minority preference is an impermissible means

of meeting those requirements. (D. at 1-3) The court held that

7 /section 703(a), read in conjunction with section 703 (j) — ,

7/ Section 703(a) provides in pertinent part:

It shall be an unlawful employment practice

for an employer . . .

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify his

employees or applicants for employment in any

way which would deprive or tend to deprive any

individual of employment opportunities or

otherwise adversely affect his status as an -

employee, because of such individual's race,

color, religion, sex, or national origin.

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(a)(2)

Section 703 (j) provides:

[Nothing in Title VII] shall be interpreted to

require any employer . . . to grant preferential

treatment to any individual or to any group

because of . . . race, color, religion, sex or

national origin . . . on account of any imbalance

which may exist with respect to the . . . percentage

of persons of any race, color, religion, sex, or

national origin employed by any employer . . . in

comparison with the . . . percentage of persons of

such race, color, religion, sex or national origin

in any community . . . or in the available work force . . .

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(j)-6-

forbids preferential treatment based on race to correct racial

imbalances, no matter how those imbalances may have been caused.

The court stated:

On their face, these statutes appear to

prohibit the numerical hiring scheme embodied

in the order of the civil service commission.

The scheme makes minority status a qualifica

tion for each third opening in the Attorney I

class in the district attorney's office.

Contrary to the seeming letter of section

703(a)(2), it classifies individuals in a way

depriving Caucasian males of eligibility for

that third job. According to a fair reading

of section 703 (j), the prohibition in section

703(a)(2) is not to be sidestepped by reason

of an existing imbalance. Section 703 (j)

draws no apparent distinction between imbalances

caused by one circumstance or another. If

section 703(a)(2) prohibits minority hiring

preferences to remedy an imbalance caused by

past discrimination, section 703(j) seems to

express congressional intent to preserve that

prohibition, intact and undiminished.

D. at 12.

The court further reasoned that defendant's affirmative action

efforts could not be justified by section 706(g), because the

remedial authority provided there is limited to remedies created

in response to a finding that the employer engaged in intentional

discrimination.

As is more fully discussed below, the court erred in

failing to recognize that the existence of past and present

discrimination against minorities within the agency made the

minority hiring program an appropriate remedial action under

the Act, and thus the program was not in contravention of the

provisions of sections 703(a) and (j), and 706(g).

-7-

A. Rule 7.10 and Defendant's Order Do Not

Violate Section 703(a)(2) of Title VII

The lower court found that the minority employment program

violates section 703(a)(2) in that it classifies individuals

in a way that deprives white males of eligibility for each third

opening in the Attorney I class in the district attorney's

office. It reached this conclusion even though the primary

purpose of the minority hiring program is to eliminate the

present effects of past discrimination by providing relief to

minorities harmed by the agency's discriminatory employment

practices,and even though it is uncontrovertibly established

in the record that minority attorneys were drastically under

represented on the staff of the district attorney's office,

and that this underrepresentation resulted from discrimination

8 /against minority job applicants. —

Congress, in enacting section 703(a)(2), did not intend

to prohibit such legitimate affirmative action designed to remedy

the effects of racial discrimination. Indeed, the fact that

Congress felt obliged to include section 703(j) in Title VII

to indicate that Title VII does not require preferential treat

ment on the basis of racial imbalance alone, indicates that

Congress recognized that section 703(a)(2) does not prohibit

affirmative action as a remedy for discrimination. Otherwise

there would be no need for section 703 (j) at all. Had Congress

desired to prohibit affirmative action altogether, it could

8/ CT at 18-21 (Findinga VII to XIX).

-8-

have broadened the language of section 703 (j) to state that

preferential treatment is not permitted under any circumstances.

Instead, as the statute was written, section 703(j) merely states

that preferential treatment is not required by the Act "on

account of an imbalance which may exist" in an employers' work

force in comparison with the surrounding community.

This interpretation of section 703(a)(2) is confirmed by

the decisions of the federal circuit courts. These decisions,

which "are persuasive and entitled to great weight" (People v.

Beadley, 1 Cal.3d 80, 86 (1969)) in matters of federal law,

are in uniform agreement that racial hiring ratios, such as

created by the challenged rule and order are an appropriate

remedial device when used to remedy the effects of past discrimi

nation, and prevent the continuation of discrimination in the

future.

Thus, the nine circuit courts that have faced this issue

have all held that hiring, promotion or referral quotas are an

appropriate remedy for employment discrimination that has'

9 /adversely affected a class. — See, e.g., Castro v. Beecher,

459 F.2d 725 (1st Cir. 1972); Rios v. Enterprise Ass'n. Steamfitters,

Local 638, 501 F.2d 622 (2d Cir. 1974); United States v. Elevator

Constructors, Local 5, 538 F.2d 1012 (3rd Cir. 1976) ; Patterson

v. American Tobacco Co., 535 F.2d 257, 273-74 (4th Cir. 1976);

9/ The Supreme Court has never ruled on the legality of quotas

as a remedy for employment discrimination. In fact, the court

has expressly reserved decision on this issue. McDonald v.

Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co., 427 U.S. 273, 281 n.8 (1976).

-9-

Morrow v. Crisler, 491 F.2d 1053 (5th Cir.) (en banc), cert.

denied, 418 U.S. 895 (1974); United States v. IBEW, Local 38,

428 F.2d 144, 149 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 400 U.S. 943 (1970);

United States v. City of Chicago, 549 F.2d 415 (7th Cir. 1977);

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 327 (8th Cir. 1972) (en banc)

cert, denied, 406 U.S. 950 (1972); United States v. Ironworkers,

Local 86, 443 F.2d 544 (9th Cir.), cert. denied, 404 U.S. 984

(1971). Each of these decisions rests on the principle that

quotas are appropriate, and at times required, when used to

eliminate the effects of past discrimination and ensure that it

does not continue in the future. — ^

In Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976)

the Supreme Court held that victims of past discrimination were

entitled to seniority relief in order to place them in the place

they would have enjoyed absent discriminatory hiring practices.

The court made it clear that an award of seniority credit could

not be denied on the ground that it conflicts with the interests

of white employees, because the denial of relief would "generally

frustrate the central 'make whole' objective of Title VII."

Id. at 774. The court made it clear that the provisions of

10/ For example, in the most recent case, Davis v. County of

Los Angeles, 566 F.2d 1334(9th Cir. 1977), the Ninth Circuit

approved an order requiring accelerated hiring of racial minorities

in a ratio of one Black and one Mexican American applicant for

each three white applicants until population parity was reached.

According to the court, the order was fully appropriate.because

"an accelerated hiring order is the only way to overcome the

presently existing effects of past discrimination within a

reasonable period of time." Id_. at 1344.

-10-

section 703, which define prohibited employment practices, do

not qualify or proscribe relief appropriate under the remedial

provisions of the Act. Id. at 758-762.

Although Franks involved the issue of constructive seniority

relief for minorities, the reasoning of the case applies with

equal force to affirmative hiring relief. The circuit courts

have repeatedly held that where an employment ratio or quota

is imposed to achieve the remedial objectives of Title VII, it

does not conflict with the general nondiscrimination provisions

of the statute contained in § 703(a). Section 703(a) of Title

VII outlaws discrimination against any group, minority or majority,

if based on race; but it does not prohibit preferences designed

to provide a remedy for a class victimized by discrimination.

As the Third Circuit stated in Contractors Ass'n. of Eastern

Pa. v. Secretary of Labor, 442 F.2d 159, 173 (3rd Cir. 1971) ,

cert. denied, 404 U.S. 854 (1971):

To read § 703a [to outlaw remedial preferences]

we would have to attribute to Congress the

intention to freeze the status quo and to

foreclose remedial action under other authority

designed to overcome existing evils. We

discern no such intention either from the language

of the statute or from its legislative history.

B. Rule 7.10 and Defendant's Order Do Not

Violate Section 703(j) of Title VII__

Contary to the decision of the Court of Appeal, section

703 (j) does not restrict the scope of remedies that may be

adopted to correct violations of Title VII. Instead, it merely

places a limitation on the circumstances which will support a

finding that the Act has been contravened. Section 703(j) is

-11-

contained in the portion of Title VII'which defines substantive

violations of the Act: Section 703(a) and section 704 list

employment practices deemed to constitute violations of Title

VII and sections 703(b)-(j) set forth specific practices and

factual situations deemed not to be violations. Section 703 (j),

therefore, merely prevents a court from basing a finding of

liability solely upon a showing that an employer's workforce

does not mirror the racial make-up of the surrounding community.

United States v. Iron Workers, Local 86, 443 F.2d 544, 553-554

(9th Cir. 1971) . — '/

Thus, although section 7 03 (j) curtails a court's power to

find a violation of the Act, it places no limitations on the scope

of the remedy that may be imposed once a violation is found, or

the type of affirmative action that may be undertaken by an

employer voluntarily in the absence of such a judicial finding.

See, e.g., United States v. Elevator Constructor's Union, 538 F.2d

1012 (3rd Cir. 1976); EEOC v. American Telephone and Telegraph

Co., 556 F.2d 167, 174 (3rd Cir. 1977); cf. , Franks v. Bowman

12/Transp. Co., supra, 424 U.S. at 757-762. — ■

11/ As the court noted in United States v. IBEW, Local 38,

428 F.2d 144, 149 (6th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 400 U.S. 943

(1970), section 703(j) "prohibits interpreting the statute to

require 'preferential treatment' solely because of an imbalance

in racial employment existing at the effective date of the Act."

12/ In Franks, the Supreme Court held that a limiting provision

(§ 703(h)) appearing in the section of Title VII defining violations

was applicable only to determining what constituted an appropriate

cause of action, not to the relief that would be available under

§ 706(g) upon a proper showing of discrimination. Franks v.

Bowman, supra, 424 U.S. at 758-759. Similarly,.section 7 0 3 (j)

appears within this same section and should not be read to deny

relief otherwise available.

-12-

Even if section 703(j) is interpreted as restricting the

scope of permissible remedies, it refers only to preferential

treatment implemented to achieve racial balance with the

surrounding community. It cannot be read to apply to affirmative

action designed to eliminate continuing inequalities resulting

from past discrimination.

The courts have recognized this distinction, and unanimously

agree that section 703(j) is an attempt by Congress to differentiate

between the use of racial classifications to rectify past or

present discrimination, and the use of racial classifications to

attain racial balance for its own sake. Patterson v. American

Tobacco Co. , 535 F.2d 257, 273 (4th Cir. 1976) (§ 703 (j) bans

use of preferential hiring to change racial imbalance attributable

to factors other than discrimination; courts are authorized

under Title VII to grant preferential relief as a remedy for

unlawful discrimination); Rios v. Enterprise Association, 501 F.2d

622, 630-631 (2d Cir. 1973) (section 703 (j) intended to bar

preferential quota hiring as a means of changing a racial

imbalance attributable to causes other than unlawful discrimina

tory conduct); Boston Chapter NAACP v. Beecher, 504 F.2d 1017,

1028 (1st Cir. 1974) (section 703 (j) deals only with those cases

in which racial imbalance has come about completely without

regard to the actions of the employer). See also, United States

v. Ironworkers Local 86, supra., 443 F . 2d at 553-554 ; Local 53

of Int. Ass1n. of Heat & Frost I. & A. Wkrs. v. Vogler, 407 F.2d

1047, 1053-1054 (5th Cir. 1969).

13-

The legislative history of section 703(j) demonstrates that

this section was placed in the Act simply to counter any belief

that employers are required by the Act to correct a racial imbalance

in their workforce not withstanding evidence that the imbalance

is not created by past or present discrmination. Nowhere does

the legislative history indicate that section 703(j) was intended

to limit the scope of permissible affirmative action that could

be judicially ordered, administratively imposed, or voluntarily

undertaken. Nor does the legislative history indicate that this

section applies to anything other than imposed racial preferences

to achieve racial balance, or that it is intended to limit

remedies designed to eliminate the effects of discrimination.

Subsequent to the enactment of Title VII, at least five

circuits rejected the contention that remedial racial preferences

were impermissible under section 703(j), holding that such an

interpretation would nullify the stated purposes of the Act.

See, e.g., United States v. Iron Workers, Local 86, supra, 443 F.2d

at 544 (9th Cir. 1971); United States v. IBEW, Local 38, supra,

428 F.2d at 149-159 (6th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 400 U.S. 943

(1970); Contractors Assn, of Eastern Penn, v. Secretary of Labor,

supra, 442 F.2d at 159 (3rd Cir. 1971); United States v. Sheetmetal

Workers, Local 36, 416 F.2d 123 (8tll Cir. 1969) ; Local 53,

Asbestos Workers v. Vogler, supra, 407 F.2d 1047 (5th Cir. 1969).

13/When Congress amended Title VII in 1972 — it was well

aware of the interpretation of the Act developed in these and

13/ Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Pub. L. No. 92-261,

86 Stat. 103.

-14-

similar cases, yet the 1972 amendments did not make any changes

in the law to modify this interpretation. Where Congress did

not amend the statute, it intended to leave unimpeded the

interpretation given the statute by existing case law. The

section-by-section analysis of the amending bill, HR 1746,

provides:

In any area where the new law does not

address itself, or in any areas where a

specific contrary intention is not indicated,

it was assumed that the present case law as

developed by the courts would continue to

govern the applicability and construction of

Title VII.

Subcomm. on Labor of the Senate

Committee on Labor and Public

Welfare, Legislative History of the

Equal Employment Opportunity Act

of 1972 at 1844 (1972).

Furthermore, Congress rejected several amendments to the

Act which were expressly designed to overturn the cases

14/approving employment preferences. — Senator Ervin took the

position that section § 703 (j) forbade the use of quotas to

remedy the effects of past discrimination. Recognizing that

the office of Federal Contract Compliance, the EEOC and the courts

14/ In addition, S.B. 2515, later passed by the Senate and engrossed

Into H.B. 1746, originally eliminated the affirmative action

requirement of the Executive Order by transferring the entire

enforcement program to the EEOC. The Senate eliminated that

provision by an amendment offered by Senator Saxbe. The Senator's

remarks in support of that amendment clearly approve the goals

and timetables approach to equal employment opportunity, and

make it clear that Congress approved such affirmative action

techniques even where discrimination against minorities had not

been proved. . Legislative History, supra at 915.

-15-

had interpreted § 703(j) as not prohibiting quota-based relief,

Senator Ervin proposed an amendment which declared that "no

department, agency, or officer of the United States shall require

an employer to practice discrimination in reverse by employing

persons of a particular race, . . . in either fixed or variable

numbers, proportions, percentages, quotas, goals, or ranges."

Legislative History, supra, 1017, 1038-1039. In the ensuing

debate it was clearly recognized that the amendment was intended

to abolish all forms of quota relief theretofore recognized

15/whether judicially or administratively imposed. — The Senate

rejected the Ervin amendments by a two to one margin. — ^ See

Legislative History, supra, at 1017, 1042-1074; 1681, 1714-1717.

As the Third Circuit has noted, "the solid rejection of the Ervin

amendment confirmed the prior understanding by Congress that an

affirmative action quota remedy in favor of a class is permissible."

EEOC v. American Tel. & Tel. Co., supra, 556 F.2d at 177. See

also, Boston Chapter NAACP v. Beecher, supra, 504 F.2d at 1028.

15/ Senator Javits, the principal spokesman against the Ervin

amendments, specifically defended the pro-quota results in United

States v. Iron Workers, Local 86, supra, and Contractors Associa

tion v. Secretary of Labor, supra, and had both opinions printed

verbatim in the Congressional Record. Legislative History, supra,

at 1047-1070.

16/ Subsequently, Senator Ervin introduced another amendment

which would have explicitly applied § 7 03 (j) to any other statu

tory enactment and to all executive orders. This amendment was

also defeated by a two to one margin. Legislative History, supra,

at 1681, 1714-1717.

-16-

C. The Remedial Authority Granted by Section 706(g)

Is Not Limited to Cases of Intentional Discrimination

The lower court's holding that the affirmative action to

remedy the effects of past discrimination is limited to cases

in which the employer engaged in intentional discrimination was

based on language in section 706(g) of the Act which provides

for affirmative action as a remedy for intentional discrimination.

The first sentence of section 706(g) provides:

If the court finds that the respondent has

intentionally engaged in or is intentionally

engaging in an unlawful practice charged in

the complaint, the court may enjoin the

respondent from engaging in such unlawful

employment practice, and order such affirmative

action as may be appropriate. . . .

Section 706(g) is the part of the statute which delineates

the remedial authority for violations of the Act. Although

this section refers to intentional discrimination, it has been

uniformly construed to mean that the defendant intended to

engage in the particular acts which adversely affected minorities,

not that defendant harbored an evil intention to violate the

law. As the Supreme Court stated in Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424, 432 (1971) the Civil Rights Act is not concerned

with "good intent or the absence of discriminatory intent",

rather "Congress directed the thrust of the Act to the consequence

of employment practices, not simply the motivation." The court

reiterated this principle in Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229,

246-247 (1976) stating:

Under Title VII, Congress provided that when

hiring and promotion practices disqualifying

substantially disproportionate numbers of

-17-

Blacks are challenged, discriminatory purposes

need not be proved.

See also, Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 422

(1975).

Accordingly, the courts have routinely imposed hiring

quotas in cases where no showing was made that the defendant

had any intent or purpose to discriminate against minorities,

basing the order imposing quota relief on a showing of discrimina

tory impact alone. Boston Chapter NAACP v. Beecher, supra,

504 F.2d at 1028 (Title VII permits quota relief undertaken

to redress past discrimination, whether or not the violation

was intentional.)

Ill

DEFENDANT IS AUTHORIZED BY TITLE VII TO

ADOPT ITS MINORITY EMPLOYMENT PROGRAM

VOLUNTARILY____________________________

The lower court also concluded that the remedial authority

contained in section 706(g) of the Act merely defines the scope

of permissible court-ordered relief and that the cases approving

racial hiring ratios or quotas were inapplicable to the Commission's

voluntarily-adopted minority employment program. According to

the court, the federal courts may order an affirmative action

program containing minority hiring preferences as a form of

relief in an employment discrimination case, but it violates

Title VII for an employer voluntarily to adopt the same type

of affirmative hiring relief.

There is no support for the proposition that what the courts

may force upon employers after a finding of liability, employers

may not voluntarily institute. Cooperation and voluntary

18-

compliance with the law is the central theme of Title VII.

Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody, supra, 422 U.S. at 417-418.

Indeed, the achievement of compliance through persuasion, con

ciliation, and voluntary action, rather than litigation, is the

"preferred means" to achieve the statutory goals. Alexander v.

Gardner Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36, 44 (1974); See, United States

v. ftllegheny-Ludlum Industries, Inc., 517 F. 2 d 826, 840-847

(5th Cir. 1975); Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d

211, 258 (5th Cir. 1974); Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach, 398 F.2d

496, 493 (5th Cir. 1968).

Because of this emphasis on voluntary compliance contained

in the Civil Rights Act, the federal courts grant substantial

deference to efforts by employers to formulate a voluntary remedy

for employment discrimination. See, e,g. , Joyce v. McCrane,

320 F.Supp. 1284 (D. N.J. 1970) (approving a voluntary affirmative

action plan adopted by the state pursuant to Executive Order

11246); Barnett v. International Harvester, 11 EPD par. 10,846

(W.D. Tenn. 1976) (court rejected challenge by white applicants

to a voluntary racial quota entered into between the company

and the union). Such deference is plainly appropriate: A rule

prohibiting employers from adopting remedial affirmative action

programs as extensive as those that 'may be imposed by court

order would obviously make it impossible for employers to

develop a remedy comprehensive enough to eliminate the effects

of discrimination. Since good faith is not a defense to a

Title VII action, employers deciding to bring themselves into

-19-

compliance with the law would be unable to take.action suffi-

17 /cient to insulate themselves from liability. —

Federal courts have rejected challenges to consent agree

ments by intervening white employees based on the contention

the relief contravenes Title VII and the equal protection

clause. These courts have indicated that the judicial authority

to approve quota relief contained in a settlement is broader

than the courts' authority to impose such a remedy after trial.

As the Second Circuit has stated it, the federal courts should

grant substantial deference to the parties determinations

about the appropriateness of relief contained in a settlement

agreement, since "voluntary compliance by the parties over an

extended period will contribute significantly toward the achieve

ment of statutory goals." Patterson v. Newspaper and Mail

Deliverers Union, 514 F.2d 767 (2d Cir. 1975). See, EEOC v .

AT&T, 556 F.2d 167 (3d Cir. 1977); Oburn v. Shapp, 521 F.2d

142 (3d Cir. 1975).

The principle that Title VII does not limit the power of

an employer to provide affirmative relief for employment

discrimination is also reflected in the cases upholding

17/ For this reason the federal courts routinely approve consent

decrees which incorporate employment ratios or quotas as an

ingredient of the class remedy, even though the parties agreed

to the relief without a judicial finding or an admission by the

employer that the employer had in fact engaged in illegal

discrimination against minorities. See, e.g., Oburn v. Shapp,

393 F.Supp. 561 (E.D. Pa. 1975), aff'd 521 F.2d 142 (3d Cir.

1975); Patterson v. Newspaper and Mail Deliverers Union, supra;

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, supra, 517 F.2d

at 826; EEOC v. A.T.&~T., supra, 73 F.R.D. at 269.

-20-

affirmative action programs that set hiring goals or ratios

for employment of minorities by state 6r federal contractors.

Although these plans require contractors to comply with speci

fic percentage goals and timetables for employment of minorities

they have been upheld against challenges on Title VII grounds.

See, e.g., Southern Illinois Builders' Ass'n. v. Ogilvie,

471 F.2d 680 (7th Cir. 1972) Associated General Contractors of

Massachusetts Inc, v. Altshuler, 490 F.2d 9 (1st Cir. 1973),

cert, denied, 416 U.S. 957 (1974), Contractor's Ass'n. of

Eastern Penn, v. Secretary of Labor, supra, 442 F.2d 159, cert. .

denied, 404 U.S. 854; Weiner v. Cuyahoga Community College

Dist., 19 Ohio St. 2d 35, 249 N.E.2d 907 (1969), cert, denied,

396 U.S. 1004 (1970); Joyce v. McCrane, 320 F.Supp. 1284

(D. N.J. 1970).

In each of these cases- the courts recognized that the

federal executive has authority to require contractors to

implement affirmative action programs independent of Title VII.

In each case, the court found that administrative findings of

minority under-representation was an adequate basis for the

imposition of an affirmative remedy, even though there had

been no judicial or administrative finding of illegal discrimina

tion by any of the employers involved. These decisions also

demonstrate that the nonjudicial authority to adopt affirmative

action remedies is far broader than the authority vested in

the judicial branch.

The emphasis on voluntary compliance and the concommitant

-21-

policy of deference to nonjudicial efforts to remedy employ

ment discrimination is particularly applicable to affirmative

action programs voluntarily adopted by state or local govern

ment authorities. As the First Circuit has stated, "the

discretionary power of public authorities to remedy past

discrimination is even broader than that of the judicial

branch". Associated General Contractors of Massachusetts, Inc.

18/v. Altshuler, supra, 490 F.2d at 17. — - Further the duty to

maintain fair and nondiscriminatory criteria for public employ

ment falls in the first instance on the responsible government

officials, not the courts. NAACP v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614, 622

(5th Cir. 1974). Public agencies are better equipped than the

courts to determine the specific causes of discrimination within

the agency and to formulate an appropriate remedy. This is

particularly true of an agency such as the Sacramento Civil

Service Commission which has a unique expertise in matters of

personnel administration. In the present case the Civil Service

Commission conducted extensive hearings into the causes of the

underrepresentation of minority attorneys in the district,

attorney's office. Based on the record developed at these

hearings it determined that this underrepresentation had resulted

18/ See also, Swann v. Charlotte-Mechlenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1, 16 (1971) holding that although the judicial power

to remedy the effects of discrimination rests on a finding of

statutory or constitutional violation, other governmental

agencies have the authority to take affirmative action to remedy

the effects of agency discrimination, even in the absence of a

finding of prior racial discrimination.

-22-

from discrimination against minority attorneys which manifested

itself at a number of stages in the employment process. Using

its expertise in matters of personnel administration, it

forumulated a remedy which was carefully drawn to fit the

particular demands of the situation the agency was faced with.

This is precisely the kind of voluntary affirmative action

19/Title VII was designed to encourage. —

To deny employers the right to formulate their own remedies

would make it necessary for employers who are guilty of illegal

discrimination to do nothing to remedy the situation until

they are sued by an aggrieved job applicant. Not only would

this impose upon the courts and employers the onerous burden

of unnecessary litigation, it would eviscerate the statutory

policy of voluntary compliance.

19/ See Policy Statement on Affirmative Action Programs for

State and Local Government Agencies, 41 Fed.Reg. 38811, (joint

statement of Department of Labor, EEOC, Civil Service Commission

and Department of Treasury), which provides in part:

On the one hand, vigorous enforcement of the laws

against discrimination is essential. But equally,

and perhaps even mor- important, are affirmative,

voluntary efforts on the part of public employers

to assure that positions in the public service are

genuinely and equally accessible to qualified

persons, without regard to their sex, racial or

ethnic characteristics. Without such efforts

equal employment opportunity is no more than a

wish. The importance of voluntary affirmative

action on the part of employers is underscored by

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Executive

Order 11246, and related laws and regulations—

all of which emphasize voluntary action to achieve

equal employment opportunity.

-23-

IV *■

DEFENDANT'S MINORITY EMPLOYMENT PROGRAM '

IS CONSTITUTIONAL BECAUSE IT IS BASED ON

EVIDENCE OF PRIOR DISCRIMINATION AND IS

REASONABLY RELATED TO THE REMOVAL OF THE

EFFECTS OF DISCRIMINATION 20/

This court has frequently led the nation in voiding

classifications which have been used to subject racial

21/minorities to adverse treatment. — In doing so the court

has appropriately subjected such racial classifications to

strict judicial review and stated that they "must be viewed

with great suspicion" (Perez, supra, 32 Cal.2d at 719).

However, neither this court nor any other court has subjected

all racial classifications to such a demanding standard of

review. Rather, racial classifications in two broad areas

have been reviewed under a less stringent equal protection

standard. The first area--as identified in Bakke--is when

the classification benefits one racial group but does not

20/ While the Court of Appeal did not pass on the constitutionality

of Rule 7.10 and defendant's order the trial court did hold the

rule and order to be unconstitutional on their face because they

"discriminated" against white applicants.

21/ See, e.g., Jackson v. Pasadena City School Dist., 59 Cal.2d

876 (1963) (voiding de facto and de jure school segregation);

Perez v. Sharp, 32 Cal.2d 711 (1948) (voiding miscegenation

Statute almost two decades before Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1

(1967)); Mulkey v. Reitman, 64 Cal.2d 529 (1966) aff'd Reitman

v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967) (voiding initiative measure

designed to overturn fair housing laws).

-24-

cause detriment to another 22/ (Ba&ke, supra, 18 Cal.3d at 49,

n.13). The second area involves racial classifications adopted

to remedy the effects of past discrimination (Bakke, supra,

18 Cal.3d at 57). This approach is fully consistent with the

dictates of equal protection:

[I]n a society free of the perdition of

past discrimination, the courts might well

reject all attempts at racial classifica

tion. We seek, however, to provide for

practical remedies for present discrimina

tion, and to eradicate the effects of prior

segregation; at this point, and perhaps for

a long time, true nondiscrimination may be

attained, paradoxically, only by taking

color into consideration. [Citation deleted.]

We conclude that the racial classification

involved in the effect''ve integration of

public schools does not deny, but secures, the

euqal protection of the laws.

San Francisco Unified School District

v. Johnson, 3 Cal.3d 937, 951 (1971)

See also, Morrow v. Crisler, 491 F.2d 1053, 1059 (5th Cir.

1974) (Clark, J., concurring).

22/ This detriment/benefit concept, aptly described as '"dividing

and expanding pies" by one commentator (see Redlish, Preferential

Law School Admissions and the Equal Protection Clause, 22 U.C.L.A.

L.Rev. 343, 359-361 ~(1974) (hereafter "Law School Admissions") ,

has been subject to criticism as not reflecting the reality of

the cases it purports to explain (Bakke, supra, 18 Cal.3d at

74 (Tobriner, J., dissenting)); Law School Admissions, supra,

22 U.C.L.A. L.Rev. at 360-361, n.83) and may have been undermined

by a subsequent Supreme Court decision (see United Jewish

Organizations v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144, 169 (1977) (Brennan, J.,

concurring) ("While it is true that this demographic outcome

did not 'underrepresent the white population' throughout the

county, ante, at 154, indeed, the very definition of proportional-

representation precludes either under or over-representation—

these particular petitioners filed suit to complain that they

have been subjected to a process of classification on the basis

of race that adversely altered their status.").

-25-

While Johnson arose in the scfiool context, a plethora

of federal decisions have refused to apply strict scrutiny to

racial classifications ordered or adopted to remedy the effects

of past discrimination. Thus in Carter v. Gallagher, supra,

452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. 1972), cert, denied 406 U.S. 950, the

Eighth Circuit sitting en banc upheld the constitutionality

of a court order requiring that one out of every three persons

hired by a Fire Department be a minority individual (IdL at

331). The court recognized the dangers of racial "preferences"

(Id. at 330), but did not treat the classification as suspect

or subject it to strict scrutiny. Rather it emphasized the

limited nature of the remedy, the continued us'e (as here) of

unvalidated job examinations, and the'fact that minorities

might not apply for employment with the Department "absent

some positive assurance that if qualified they will in fact

be hired on a more than token basis". (Id., at 331) . Similarly

the Seventh Circuit approved a minority preference plan designed

to overcome the effects of past discrimination in Southern

Illinois Builders Association v. Ogilvie, 471 F.2d 680 (7th

Cir. 1972). Again the court did not treat the racial classifi

cation created by the plan as suspect or subject it to strict

scrutiny. Instead, it emphasized the existence of prior and

present discrimination, the limited time period during which

the plan was to operate, and the flexibility in the plan (Id.

at 686).

Numerous other federal decisions are in accord. See,

e.g., Erie Human Relations Commission v. Tullio, 493 F.2d 371

-26-

(3rd Cir. 1974); Morrow v. Crisler, -supra, 491 F.2d at 1053;

NAACP v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614 (5th Cir.' 1974) ; Castro v. Beecher,

supra, 459 F.2d 725; Bridgeport Guardians, Inc, v. Members of

Bridgeport Civil Serv. Comm'n., 482 F.2d 1333 (2nd Cir. 1973);

Vulcan Society v. Civil Service Commission, 490 F.2d 387 (2nd

Cir. 1973); Constructors Assoc, of Western Pa. v. Kreps, 441 F.

Supp. 936 (W.D. Pa. 1977); R.I. Chapter, Associated Gen.

Contractors v. Kreps, 446 F.Supp. 553 (D.R.I. 1978); Germann

v. Kipp, 429 F.Supp. 1323 (W.D. Mo. 1977); Associated General

Contractors v. Altshuler, supra, 490 F.2d 9; Contractors Ass'n..

v. Secretary of Labor, supra, 442 F.2d 159; Joyce v. McCrane,

320 F.Supp. 1284 (D.N.J. 1970). — '/

23/ In light of this long line of authority the trial court's

finding that the rule was unconstitutional on its face is puzzling.

Although plaintiff attempted to distinguish the above cases on the

basis that they solely dealt with the power of a federal court to

order race conscious programs after a judicial finding of past

discrimination such a distinction is incorrect and irrelevant.

First, the purported distinction is non-existent because the

decisions do not require a judicial finding of past discrimination

as a precondition to the adoption or imposition of a race conscious

program (see, e.g., Altshuler, supra, 490 F.2d at 14 (the Massachu

setts Plan); Southern Illinois Builders Ass'n., suora, 471 F.2d at

684 (the Illinois Ogilvie Plan); Contractors Ass v. Secretary

of Labor, supra, 442 F.2d at 163, 174, 177 (the . iadelphia Plan);

Constructors Assoc, of Western Pa. v. Kreps, sup , 441 F.Supp.

at 441 (legislative enactment to remedy past di crimination);

Joyce v. McCrane, supra, 320 F.Supp. at 1287-1288 (the Newark Plan).

Second, if it is constitutional for a court, a legislature, and

an administrative agency to require an employer to adopt a race

conscious program if past discrimination exists, it is difficult

to find the rationale for a constitutional theory making such a

program unlawful if adopted voluntarily by the employer. This

would appear to be especially true where, as here, affected

individuals may challenge the correctness of the finding of prior

discrimination as well as other findings supporting implementation

of the program (see, e.g., Rule 7.10 subdivision (f)). Finally

it is not only permissible for a public employer to adopt a race

conscious program but may be required (Cf., Crawford, supra,

17 Cal.3d at 284; Southern Pac. Transportation Co. v. Public

Utilities Com., 18 Cal.3d 308, 311 n.2 (1976)).

-27-

While the above decisions do hot uniformly agree upon

the precise standard to judge remedial racial classifications,

they do agree that such classifications are neither suspect

nor properly subject to the traditional strict scrutiny standard

of equal protection review. The most frequently accepted

standard is that "the means chosen to implement the compelling

interest should be reasonably related to the desired end".

Altshuler, supra, 490 F.2d at 18 (emphasis added). Accord:

NAACP v. Allen, supra, 493 F.2d at 619; Constructors Assoc.

24/of Western Pa, v. Kreps, supra, 441 F.Supp. at 950 — ; R,I.

Chapter, Associated Gen. Contractors v. Kreps, supra, 446 F.Supp.

at 567 ("carefully tailored to accomplish remedial goal"); cf.,

United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh, Inc, v. Carey,

430 U.S. 144 (1977) . — '/

Defendant has satisfied this standard here. First, the

minority employment program furthers a compelling state interest

24/ While the court in Kreps initially stated that the '"means

used be necessary" (441 F.Supp. at 950), its subsequent explana

tion of that term (means "must have a logical nexus to compelling

objective and must sufficiently reduce the dangers of such

classification so that no less onerous alternatives are reasonably

available" Id. (emphasis added)) as well as its rejection of a

more generalized classification as over inclusive (Id. at 953

n.10) demonstrates that it was not adopting the traditional

strict scrutiny test (see discussion of test in Bakke, supra,

18 Cal.3d at 49 and Ramirez v. Brown, 9 Cal.3d 199, 210-212

(1973) rev1d sub nom Richardson v. Ramirez, 418 U.S. 24 (1974) .

25/ At least two cases have adopted the even more lenient

rational basis test. See Germann v. Kipp, supra, 429 F.Supp.

at 1335-1337; Rosenstuck v. Bd. of Governors of Univ. of N.C.,

423 F.Supp. 1321, 1325 (M.D.N.C. 1976).

-28-

because "remedying past discrimination constitutes a compelling

interest" (R.I. Chapter, Associated Gen. Contractors v. Kreps,

supra, 446 F.Supp. at 568 and cases there cited). Second,

as discussed infra, the program is both reasonably related

and even necessary to achieve this interest. Moreover the

program meets all the guidelines that have been identified as

important in evaluating racial preference programs. For example,

courts and commentators have found the following important:

(i) whenever possible preferences should not displace persons

holding existing positions (see Davidson, Preferential Treatment

and Equal Opportunity, 55 Ore. L.Rev. 53, 75 (1976)); (ii) rights

associated with existing positions should be modified only where

other approaches are inadequate (111. , at 75-76; Bridgeport

Guardians, Inc., supra, 482 F.2d at 1341); (iii) provisions

to waive or modify the preference should exist (Constructors

Assoc, of Western Pa., supra, 441 F.Supp. at 954); and (iv)

selection preferences should be avoided where possible and, if

used, should be limited by number or duration (Equal Opportunity,

supra, 55 Ore. L.Rev. at 76; NAACP v. Allen, supra, 493 F.2d

at 621; Constructors Assoc, of Western Pa., supra, 441 F.Supp.

at 953).

The minority employment program contains provisions

providing for modification and waiver; has been interpreted as

requiring the failure of other less drastic methods; is solely

applicable to new positions; and is limited in number (see

discussion in §1, p. 4, supra). In light of this plaintiff's

-29-

contention in their brief in the court below (respondent's

Brief, p. 34) that the program is invalid because it fails to

provide for consideration of less onerous (i.e., non racial)

alternatives (e.g., increased recruiting, special programs for

economically deprived persons) is inconsistent with the facts

of this case. More importantly however, the reasonable relation

test does not require such a strict standard (see extensive

discussion of this point in R.I. Chapter, Associated Gen.

26/Contractors v. Kreps, supra, 446 F.Supp. at 573-574). — Thus

in the Constructors Association case it was urged that a less

onerous alternative to the 10% minority business enterprise

participation requirement would be the establishment of a "more

generalized classification such as 'disadvantages business.'"

(Constructors Assoc., supra, 441 F.Supp. at 953, n.10). However,

the court rejected this less .onerous alternative as "more

difficult to apply" and not as efficiently achieving the state's

compelling state interest (Id.). These same comments would be

equally applicable to the alternatives suggested above to the

rule.

It might additionally be contended that the rule is not

reasonably related because it is both over and under inclusive

26/ If strict scrutiny were applicable defendant would be

required to show "that there are no reasonable ways to achieve

the state's goals by means which impose a lesser limitation on

the rights of the group disadvantaged by the classification"

(Bakke, supra, 18 Cal.3d at 49). Even this strict test may be

satisfied in light of the findings found in the challenged order

(see Findings XIII and XV, CT 19, 20).

-30-

as it fails to aid the specific victims of the employer's past

discriminatory actions (see discussion- in Carter v. Gallagher,

452 F.2d at 325-326 (panel opinion) and 452 F.2d at 330 (en

banc opinion); Lige v. Town of Montclair, 367 A.2d 833, 862-863

(New Jersey Supreme Court 1976) (Pashman, J., dissenting)).

The overwhelming weight of the case law, however, is to

the contrary. As recently noted by the Ninth Circuit in Davis

v. County of Los Angeles, supra, 566 F.2d at 1343: "We do not

believe that [race conscious] relief may be limited to the

identifiable persons denied employment in the past--for 'the

presence of identified persons who have been discriminated

against is not a necessary prerequisite to ordering affirmative

relief in order to eliminate the present effects of past

discrimination.' Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d at 330." See

also discussion in Bakke, supra, 18 Cal.3d at 77, n.8 (Tobriner,

j., dissenting) and the numerous federal cases upholding minority

preference programs which did not solely benefit the specific

27/victims of discrimination. ——'

In some circumstances, such as the present, the remedy

cannot truly be characterized as over-inclusive. Sometimes it

is possible to identify each specific person who has been harmed

by an employer's discrimination and to provide particular relief

to that individual (see, e.g., Local 53 v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047

27/ See, e.g., Altshuler, supra, 490 F.2d at 18-19 (extended

benefits to new applicants for employment); Contractors Ass'n.

v. Secretary of Labor, supra, 442 F.2d at 163-164 (Id.);

Southern Illinois Builders Association, supra, 471 F.2d at 681-

683 (Id.); Bridgeport Guardians, supra, 491 F.2d at 1056 (Id.)

-31-

the state's compelling interest in remedying the effects of

past discrimination was fully satisfied by individualized

2 8/relief and a race conscious program not necessary. — However,

in other situations where, as here, the employer's discriminatory

actions include a failure to recruit minorities the specific

2 9/"victims" of discrimination are unidentifiable. — Here the

state's interest in eradicating the effects of prior discrimina

tion cannot be achieved by limiting relief to identifiable

victims and therefore the program cannot accurately be characterized

as overinclusive.

The reasoning of this court in Crawford v. Board of

Education, 17 Cal. 3d 280 (1976) supports the rejection of

strict scrutiny and application of the reasonable relation

standard in this case. In Crawford the court was faced with

the question of the degree of judicial deference to be accorded

desegregation plans adopted by local school boards. The court

(5th Cir., 1969)). In such instances it could be argued that

28/ Paradoxically the longer an employer waits to impose a race

conscious program (e.g., by exhausting all nonracial alternatives

first), the more likely the victims of the employer's discrimina

tory practices, will not be the recipients of the newly accruing

benefits created by the race conscious program.

29/ Second, as a practical matter-the state's goal may never be

achieved if the employer is not allowed, under limited circum

stances, to adopt a race conscious program which compensates

minorities as a class for past discrimination. As pointed out

by the Eighth Circuit if an employer has a prior history of

discrimination it is not unreasonable to assume that minorities

would be reluctant to apply absent some positive assurance that

if qualified they would in fact be hired (Carter, supra, 452 F.2d

at 331).

-32-

initially noted that "the task of integration is an extremely

complex one" and stated:

In light of the realities of the remedial

problem, we believe that once a court finds

that a school board has implemented a program

which promises to achieve meaningful progress

toward eliminating the segregation in the

district, the court should defer to the school

board's program and should decline to intervene

in the school desegregation process so long as

such meaningful progress does in fact follow.

A court should thus stay its hand even if it

believes that alternative techniques might

lead to more rapid desegregation of the schools.

We have learned that the fastest path to

desegregation does not always achieve the

consummation of the constitutional objective;

it may instead result in resegregation. In

the absence of an easy, uniform solution to

the desegregation problem, plans developed

and implemented by local school boards, working

with community leaders and affected citizens,

hold the most promising hope for the attainment

of integreted public schools in our state.

Crawford, supra, 17 Cal.3d at

286.

The court later listed some of the numerous administrative

techniques for facilitating desegregation and further explained

the rationale for its rule of deference:

Each of the different techniques has had varied

success in different circumstances; sociologists

are just beginning to explore the complexities

which account for the differences in results and

to identify the factors which may be utilized to

determine which desegregation tool should be used

in a given situation. [Citation deleted]. Under

these circumstances, local school boards should

clearly have the initial and primary responsibility

for choosing between these alternative methods.

In our view, reliance on the judgment of local

school boards in choosing between alternative

desegregation strategies holds society's best

-33-

hope for the formulation and implementation

of desegregation plans which will actually

achieve the ultimate constitutional objective

of providing minority students with the equal

opportunities potentially available from an

integrated education.

Crawford, supra, 17 Cal.3d

at 305, 306 (footnote deleted).

The concerns expressed in Crawford are even more forceful

when, as here, the court must determine whether an employer

may lawfully have - as one possible weapon in his arsenal to

combat the evils of past discrimination--the ability to adopt

race conscious programs without a judicial finding of prior

discrimination. The problem of devising workable remedies

"for the continuing effects of past discrimination have proven

distressingly elusive" (Bakke, supra, 18 Cal.3d at 81 (dissenting

opinion)) and are as complex as those involved in school

desegregation. And, as with the school situation, there are

a variety of techniques to remedy the problem which have had

varied success in different circumstances.

Moreover, affording deference to an employer by allowing

it to utilize a wide range of possible solutions (including

race conscious programs) to remedy the effects of past discrimina

tion makes it more likely that the problem will be successfully

resolved:

Recognizing the dangers of preferential

treatment, enterprises must be allowed

the use of preferences without court order,

indeed, without the approval of any agency.

Too many enterprises exist which ought to

engage in some form of preferential treatment

for any reasonably constituted agency to

-34-

review. More importantly) the enterprise

itself is in the best position to evaluate

its problems and the range of feasible

alternatives to its current procedures.

Although an agency may be able to develop

basic methods of identifying discriminatory

procedures, the method applicable to any

specific enterprise and the development of

a remedy in almost all cases will depend

upon a specific and detailed knowledge of

the enterprise and at least general knowledge

about the excluded group. If allowed to use

preferential treatment for preferred groups,

an enterprise can use its knowledge to maximize

the chances of success for the individuals

selected and to alter the underlying dis

criminatory pattern. In so doing, the enterprise

and the individuals who formulate the remedies

may feel they have a stake in the success of

the plan they design.

There are, of course, dangers in allowing

enterprises to adopt their own preference

plans. The plans may be inadequate. More

importantly, the remedy may tend to institu

tionalize separate treatment, or the plan may

go too far, creating unjustifiable reverse

discrimination. These dangers can be

minimized by according affected individuals

the right to challenge remedial plans and

by requiring that all preferences be justified

by, and related to, identified discriminatory

barriers.

Davidson, Preferential

Treatment and Equal Opportunity,

55 Ore.L.Rev. 53, 74-75 (1976)

(footnotes deleted)

In the instant case defendant Civil Service Commission

has the necessary expertise and is in the best position to

evaluate the problems of past discrimination and the range of

feasible alternatives to its current procedures. Certainly

a program developed by it holds the most promising hope for

the attainment of the eradication of the effects of past

-35-

discrimination. Under such circumstances— as in Crawford

the Civil Service Commission should have the primary responsi

bility for choosing the range of alternative methods it finds

most appropriate.

V

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment of the Superior

Court voiding defendant's minority employment program should be

reversed.

Dated: June 9 , 1978

Respectfully submitted,

ALICE BEASLEY

JOHN Ii. ERICKSON

STEPHEN KOSTKA

CLIFFORD C. SWEET

PETER E. SHEEHAN

ALICE BEASLEY

JOHN H. ERICKSON

STEPHEN KOSTKA

PETER E. SHEEHAN

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

-36-