Miller v. International Paper Company Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

May 1, 1968

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Miller v. International Paper Company Brief for Appellants, 1968. 233c12a6-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/51df2036-2049-4cc8-959f-23c8c6036885/miller-v-international-paper-company-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

̂ . . »l> 1 1 ..'j

\

1

:

j

i

i

t

\

0

C-cjl ' T x*^Ml_.

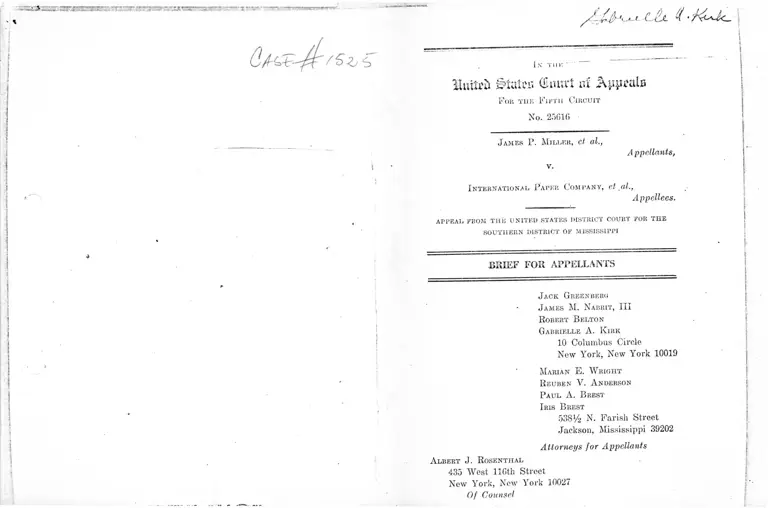

1 N TIII'.

iluiU'u Staler. (Umu*t vd Amalfi

F or t u b F ifth C ircu it

No. 25016

J am es P . Mi leer , et al.,

v.

Appellants,

I n tern ation al . P aper C o m p a n y , et al.,

Appellees.

appeal from t h e u n ited states district court for t h e

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

J ack G reenberg

J am es M. N abrit , III

R obert B elton

G abrif.lle A . K ir k

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

M arian E. W rig h t

R euben V. A nderson

P a u l A . B rest

I ris B rest

538V2 N. Parish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

Attorneys for Appellants

A lbert J . R o sen th al

435 West HGth Street

New York, New York 10027

Of Counsel

\

I N D E X

Statement of the Case ..................................................... 1

Specification of Errors ..................................................... 3

A rg u m en t :

L The District Court erred in dismissing the ac

tion as untimely ................. ................................. 3

A. Notice from EEOC is a prerequisite to a

civil suit under Title VII .............................. 5

13. Appellants did not lose their right to bring

a civil action because EEOC failed to notify

them within 30 (or 60) days after they filed

their charges ................................................... 9

II. The District Court erred in holding that this

action could not be maintained as a class action 15

A. A class action is maintainable under Title

V I I ......................... 17

B. Named plaintiffs may represent a class the

members of which have not pursued the ad

ministrative remedies of Title V I I .............. 20

III. The District Court erred in assessing appel

lants for $250 attorneys fees and costs, pay

able to appellee International Paper Company 25

C onclusion ................................... 29

Certificate of Service ............... 30

PAGE

11

A ppen d ix :

Order in Lea v. Cone Mills .................................. . la

Order in Robinson v. Lorillard .............................. 3a

PAGE

T able of Oases

Anthony v. Brooks, 65 LRRM 3074 (N.D. Ga. 1967) ....7,19

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 272 F. Supp. 332 (S.D.

Ind. 1967) ........................................................................ 19

Choate v. Caterpillar Tractor Co., 274 F. Supp. 776

(S.D. 111. 1967) .............................................................. 7

Cunningham v. Litton Industries, 66 LRM 2697 (C.D.

■ Cal. 1967) .........' ............................................................. 7

■\

Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Ry. Co., 265 F. Supp.

56 (N.D. Ala. 1967) ............................................... on, 7, lOn

Evenson v. Northwest Airlines, Inc., 268 F. Supp. 29

(E.D. Va. 1967) ........................................................ 5n, lOn

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 67 LRRM 2616 (M.D. N.C.

1967) ..............................................................................19,22

Hall v. Werthan Bag Corp., 251 F. Supp. 184 (M.D.

Tcnn. 1966) .................................................14,18,19, 21, 22

Hicks v. Crown-Zellerbach Corp., No. 16638 (E.D. La.

June 13, 1967) .........................................................19,21,24

International Chemical Workers Union v. Planters

Manufacturing Co., 259 F. Supp. 365 (N.D. Miss.

1966) ...................... .................................................... -•••• 8

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 261 F. Supp. 762 (E.D.

Tex. 1966) ...................... ™

PAOE

iii

Lance v. Plummer, 353 F.2d 585 (5th Cir. 1965), cert.

den., 384 U.S. 929 (1966) ............................................. 19

Lea, et al.'v. Cone Mills Corp., No. C-176-D-66 (M.D.

N.C. June 27, 1967) ....................................................... 22

Mondy v. Crown-Zellerbach Corp., 271 F. Supp. 258

(E.D. La. 1967) .................................................5n, 6, 9, 21n

Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 271 F. Supp. 27 (E.D.

N.C. 1967) .......................................................... 5n, 7,19, 22

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 271 F. Supp. 842 (E.D.

Va. 1967 .................................. ................................... lOn, 21

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 67 LRRM 2098 (E.D.

Va. 1968) ......................... :.... :......................................19,21

Reese v. Atlantic Steel Co., 67 LRRM 2475 (N.D. Ga.

1967) ..............................................................................7,10n

Robinson v. P. Lorillard Co., Case No. C-141-G-66

(M.D. N.C. January 26, 1967) ......................... :......... 19

Skidmore v. Swift & Company, 323 U.S. 134 (1944) .... 8

Udall v. Tallman, 380 U.S. 1 (1965) .............................. 8 '

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

372 F.2d 836 (1966), aff’d en banc 380 F.2d 896 (5th

Cir. 1967) ....................................................■-.................. 8

Ward v. Firestone Tire & Rubber Co., 260 F. Supp. 579

(W.D, Tenn. 1966) .....................................................7, lOn

S tatutes

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(a) ............

Civil Rights Act of 1964 ........ .

29 C.F.R. §1601.25(a) and (b)

.............. -..... U3

............... 3,17,19

3n, 5n,10,lOn,14

IV

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 18(a) ............. 15n

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rules 23(a) and

23(b)(2) ........................................................................17,18

PAGE

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 30(a) .............. 27

O th e r A u th o rities

Advisory Committee Note to amended Rule 23, 86 Sup.

Ct. No. 11, Yellow Supp. at 34 (1966) (reprinted in

28 U.S.C.A., F.R.C.P. 17-33, following Rule 23) ....... 19

Berg, Equal Employment Opportunity under the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 31 Brooklyn L. Rev. 81 (1964) .... 8

CCH Employment Practices Guide 17,252 .................. 20

Commission Decision 11/23/65 ....................................... 7

31 Fed. Reg. 14255 (Nov. 4, 196j6) .................................. 13

110 Cong. Rec. 2805 (daily ed. 2/10/64) ...................... 11

110 Cong. Rec. 12295 (1964) ........................................... 5n

1 Davis, Administrative Law Treatise, Sec. 5.06 (1958) 8

EEOC, First Annual Report ......................................... 24

General Counsel Opinion 10/25/65 ................................ 5n

Hill, Twenty Years of State Eair Employment Practice

Commissions: A Critical Analysis with Recommen

dations, 14 Buffalo L. Rev. 22 (1964) .................... . 12n

Norgren and Hill, Toward Fair Employment (1964) .... 12n

Opinion Letter 11/17/65 .................................................5n, 7

Opinion Letter 2/3/66 ..................................................... 20

In t h e

Shiite ( ta r t nf Appeals

F or t h e F if t h C ircu it

No. 25616

J am es P . M il l e r , et al.,

Appellants,

v.

I n tern atio n al P aper C o m p a n y , et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM TH E UNITED-STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR TH E

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF M ISSISSIPPI

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from the order of November 20, 1967,

of the United States District Court for the Southern Dis

trict of Mississippi, entering summary judgment for ap

pellees in an employment discrimination action brought

under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat.

253, 42 U.S.C. §2000e et seq. (hereinafter sometimes re

ferred to as “Title V II” ).

In December, 1966, appellants filed charges of discrim

ination with the Equal Opportunity Employment Com

mission (hereinafter referred to as “EEOC” or the “ Com

mission” ), naming as respondents the International Paper

2

Company and the unions which represent the company’s

employees at its Moss Point, Mississippi plant (R. GO-

65).1 On May 12, 1967, pursuant to the request of ap

pellants’ counsel, EEOC wrote to appellants informing

them of their right “within thirty (30) days of receipt of

this letter to institute civil action in the appropriate Fed

eral District Court” (R. 65-73). On “June'9, 1967, appel

lants filed this action against the appellees (R. 1-15).

On August 3, 1967, and August 4, 1967, the unions

(R. 42-44) and company (R. 46-47), respectively, filed

motions to dismiss pursuant to Rule 12 of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure. The district court, per Judge

William Harold Cox, treated the motion to dismiss as a

motion for summary judgment and granted the motion,

holding that the action was untimely filed because it_.was

^brought more than sixty (60) days after the charges of

discrimination were filed with the EEOC, and that the

suit could not be maintained as -a class action. The dis- ~

trict court also assessed appellants with costs and attor

neys fees in the amount of $250 for their failure to appear

at depositions noticed by the unions on Saturday, July 8,

1967.

On November 29, 1967, appellants filed a notice of ap

peal and a motion for a stay of the execution of the

judgment pending the deposition of the appeal.

1 United Papermakers and Paperworkers, AFL-CIO ; Local No.

203 of United Papermakers and Paperworkers, AFL-CIO ; Singing

River Local No; 384 of the United Papermakers and Paperworkers,

AFL-CIO ; International Brotherhood of Pulp, Sulphite, and Paper

Mill Workers, AFL-CIO; Local No. 379 of International Brother

hood of Pulp, Sulphite and Paper Mill Workers, AFL-CIO; Inter

national Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, AFL-CIO and Local

No. 181G of International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, AFL-

CIO.

i

Specification of Errors

1. The district court erred in holding that this suit was

not timely filed.

2. The district court erred in holding that the appellants

could not maintain a class action pursuant to Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

3. The district court erred in assessing appellants with-

costs and attorneys’ fees payable to the International Paper

Company for their failure to appear at the depositions on

Saturday, June 8, 1967.

The District Court erred in dismissing the action as

untimely.

In December, 1966, pursuant to Section 706(a) of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(a), appellants

filed charges of discrimination against appellees with the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

After the expiration of more than sixty (60) days,

pursuant to 29 C.F.R. §1601.25a(b),2 appellants demanded

2 29 C.F.R. §3601.25a(a) and (b) provides;

a) The time for processing all cases is extended to sixty days

except insofar as proceedings may be earlier terminated pur

suant to §1601.19.

b) Notwithstanding the provisions of subsection (a) hereof,

the Commission shall not issue a notice pursuant to §1601.25

prior to a determination under §1601.19 or, where reasonable

cause lias been found, prior to efforts at conciliation with re

spondent, except that the charging party or the respondent

may upon the expiration o7 sixty days after'the filing of the

charge or at any time thereafteigdcnnnid in writing that such

___ notice issue, and the Commission’sliall prompt I)’ issue” .such-

~~ notice to all parties,,

I

4

that the Commission issue notice to the parties advising

appellants of their right to tile suit in federal court. As

a result of this demand, the Commission informed appel

lants in letters dated May 12, 1967, three months after

the end of the sixty (GO)-day period (after the filing of

charges with EEOC), that they may “within thirty (30)

days of receipt of this letter institute a civil action in

the appropriate federal district court” (R. 65-73). This

was the first and only notice that appellants received ad

vising them of their right to file suit. On June 9, 1967,

within thirty (30) days of receipt of this notification,

appellants filed this action in the United States District

Court for the Southern District of Mississippi.

The district court granted summary judgment for the

appellees because the action had not been “ timely filed”

within the requirements of Section 706(e) of Title VII.

In reaching this decision, the court relied on two seemingly

inconsistent arguments: First, notice from EEOC is not 0 ,

a prerequisite to a civil action under Title VII and appel

lants erred in failing to sue within the time limits pre

scribed by its opinion, notwithstanding the absence of

notice.3 4 Second, although notice is a prerequisite, the Com- (T

mission’s failure to notify appellants of their right to sue

within this time period precludes this suit." Neither view

can be sustained by the language or purpose of the Act

and both views are contrary to the decisions construing

the language of the Act.

3 In footnote 2 of the opinion, the court below seems to so hold

(JR.. 57).

4 “ The charge had to be filed first and it was mandatory that the

Commission in this case notify the aggrieved person immediately

if it were unable to obtain voluntary compliance with the act so

as to entitle the offending [sic] party to file a suit” (R. 58).

5

A. Notice from EEOC is a prerequisite to a civii suit

under Title VII.

In a footnote, which is nearly all of the opinion on this

point, the district court hold that thirty (30) days after

the charges were filed with EEOC each aggrieved party

was entitled to bring suit within the next thirty (30) days,

whether or not he has received notice from the Commis

sion (R. 57).5

“ It, appears that the district court erroneously held that the

waiting period was only thirty (30) days (R. 57, ii. 2). Although

Section 706(e) speaks of an initial waiting period of thirty (30)

days, in unequivocal language it also grants to the EEOC the power

to extend that period by an additional thirty days:

(e) If within thirty days after a charge is filed with the Com

mission (except that such period may be extended to not more

than sixty days upon a determination by the Commission that

further efforts to secure voluntary compliance are warranted),

the Commission has been unable to obtain voluntary com

pliance with this title, the Commission shall so notify the

person aggrieved and the civil action may, within thirty days

thereafter, be brought against the respondent named in the

charge. . . . (Emphasis supplied.)

Early in its history, the Commission began to take the full sixty

dayrs in all cases, and on October 28, 1966, it embodied this practice

in its formal regulations:

(a) The time for processing all cases is extended to sixty days

except insofar as proceedings may be earlier terminated pur

suant to section 1601.19. 29 C.F.R. §1601.25a(a).

Every court which has considered the remedial scheme of Title

VII has accepted the Commission’s practice, and the courts have

unanimously considered the mandatory waiting period to be sixty

(60) days. See, c.g., Mondy v. Crown-Zcllerbach Corp., 271 E.

Supp. 258, 261 (E.D. La. 1967); Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co.,

2/1 P. Supp. 27, 29 (E.D. N.C. 1967); Evenson v. Northwest Air

lines, Inc., 268 P. Supp. 29, 31 (E.D. Va. 1967); Bent v. St. Louis-

San Francisco By. Co., 265-P. Supp. 56, 58 (N.D. Ala. 1967); see

also 110 Cong. Rce. 12295 (1964) (Remarks of Senator Humphrey).

In practice, the Commission has generally taken much more than

sixty (60) days, and in any event has not sent its notice to the

aggrieved party until a reasonable time after the sixty (60) days

had elapsed. See Commission Decision 11/23/65; General Counsel

Opinion 10/25/65; Opinion Letter 11/17/65. In Bent, supra, the

6

The applicable language of Section 706(e) provides:

. . . the Commission shall so notify the person ag-

grived and a civil action may, within thirty days

thereafter, be brought against the respondent named

in the charge. . . . (Emphasis added.)

y The district court completely disregarded the clear lan

guage of Section 706(e) and the extensive precedents

construing this language which points out that notice

must issue and a suit be brought within 30 days “ there

after” and left the notice requirement with no real pur

pose within the statute’s remedial scheme. Why indeed

did Congress so clearly require that notification issue prior

to the bringing of a civil suit by a charging party if the

charging party may file suit before receiving such notice ?

J To counsel’s knowledge, with only one exception, every

court considering the scope of Section 706(e) has held

that notice from the Commission is a prerequisite to com

mencement of civil litigation. In Mondy v. Zellerbach

Cory., 271 F. Supp. 258, 261 (E.D. La. 1967), in direct

response to the argument made by the court below, it

was held:

[If an aggrieved party filed suit] without first re

ceiving the statutory notice, he would be met with

the objection that he was suing prematurely, since

42 U.S.C.A. Section 2000e-5(e) says that he may bring

court characterized the sixty (60)-clay limit as directory, rather

than mandatory, upon the Commission, and all of these cases may

be regarded as inferentially so holding.

This error is, fundamentally, irrelevant to disposition of this

appeal, however; for under the rationale of the district court’s

holding that the aggrieved party must file suit within thirty (30)

days after the close of the thirty (30)-day waiting period, appel

lants' suit would be untimely even granting a sixty (60)-day

waiting period.

7

a civil action after being notified by the Commission

of its failure to obtain voluntary compliance. There

fore, he would have to wait until he received the

statutory notice from the EEOC.

Accord: Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Ry. Co., 265

F. Supp. 56 (N.D. Ala. 1967); Ward v. Firestone Tire do

Rubber Co., 260 F. Supp. 579 (W.D. Tenn. 1966) (dicta);

Moody v. Atbermarle Paper Co., 271 F. Supp. 27 (E.D.

N.C. 1967); Anthony v. Rrooks, 65 LRRM 3074 (N.D. Ga..

1967); Reese v. Atlantic Steel Co., 67 LRRM 2475 (N.D.

Ga. 1967); Choate v. Caterpillar Tractor Co., 274 F. Supp.

776 (S.D. 111. 1967). Cunningham v. Litton Industries, —■ ^^*<4

66 LRRM 2697 (C.D. Cal. 1967), holding contrary, sug

gests no understandable basis for its conclusion, and ap

pellants respectfully submit that it is incorrect. (On ap

peal to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth

Circuit.)

Indeed, from the inception of its administration of

Title VII, EEOC has recognized that notice is a pre

requisite to a private civil action. Several months after ^

the effective date of the Title (July 2, 1965), the General

Counsel stated unequivocally the Commission’s interpre

tation of Section 706(e) :

The 30-day period for filing of suits under Section

706(e) does not commence automatically upon the

expiration of the statutory period during which the

Commission is authorized to obtain voluntary com

pliance; notice by the Commission under Section 706(e)

is an integral part of the plaintiff’s cause of action,

consequently, the period within which to file a civil

action does not commence until notice from the Com

mission has been received by the person aggrieved.

Commission Decision, 11/23/65; CC Opin. 10/25/65;

Opin. Hr., 11/17/65.

8

Because this interpretation constitutes a contemporaneous

and consistent interpretation of a statute by the agency

charged with its administration, it is entitled to great

respect by the courts. As early as 1827, the Supreme Court

acknowledged that administrative constructions are highly

persuasive guides to statutory interpretation:

In the construction of a doubtful and ambiguous law,

the contemporaneous construction of those who were

called upon to act under the law, and were appointed

to carry its provisions into effect, is entitled to very

great respect. Edwards’ Lessee v. Darby, 12 Wheat.

206, 210 (1827).

Recent cases havg reiterated this approach to statutory

construction. See 1 Davis, Administrative Law Treatise

Sec. 5.06 (1958), and cases cited; Udall v. Tollman, 380

U.S. 1 (1965) ; Skidmore v. Swift & Company, 323 U.S.

134, 139-40 (1944); United States v. Jefferson County

Board of Education, 372 F.2d 836, 851 (1966), aff’d en

banc 380 F.2d 896, 902 (5th Cir. 1967); see, Berg, Equal

Employment Opportunity under the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 31 Brooklyn L. Rev. 81-82, n. 35 (1964). In Inter

national Chemical Workers Union v. Planters Manufac

turing Co., 259 F. Supp. 365, 366 (N.D. Miss. 1966) Chief

Judge Clayton, then sitting on the Court of the Northern

District of Mississippi, applied this principle of statutory

construction to uphold the EEOC’s interpretation of the

phrase “aggrieved person” in Title V II :

It has long been settled that the practical inter

pretation of a statute by the executive agency charged

with its administration or enforcement, although not

conclusive on the courts is entitled to the highest

respect. . . . Not only is the Commission’s interpre

tation of the phrase “aggrieved person” that of the

9

agency responsible for administering (lie Act; it is

also a contemporaneous construction of the statute

by those responsible “ for setting its machinery in mo

tion” and for guaranteeing the efficient working of

the statute’s machinery while it is “ still untried and

new.”

B. Appellants did not lose their right to bring a civil

action because EEOC failed to notify them within

30 (or 60) days after they bled their charges.

The district court offered the following alternative

ground for its conclusion that the suit was barred:

The charge had to be filed first and it was mandatory

that the Commission in this case notify the .aggrieved

person immediately if it were unable to obtain volun

tary compliance with the act so as to entitle the

offending (sic) party to file a suit (R. 57-58).

The court thus seemed to recognize that notice is necessary

“to entitle” plaintiffs to file a suit, but apparently main

tained that the Commission’s failure to issue “ timely”

notice barred appellants from filing suit.

Other courts considering this issue have recognized the

inconsistency and unfairness of such a holding. In Mondy

v. Croivn-Zcllcrbach Corp., 271 F. Supp. 258, 261 (E.D.

La. 1967), EEOC issued notice to the plaintiffs more than

five months after they had fded the charges. The court

held that plaintiffs were not thereby barred from bringing

suit, writing:

Surely, Congress could not have intended for an

aggrieved party to be denied his remedy under Title

VII because of the failure of the EEOC to notify him

within sixty days. We feel that the proper inter

10

pretation of 42 U.S.C.A. Section 2000e-5(e) is that a

charging party must file suit within thirty days after

receipt of the statutory notice from the EEOC regard

less of the delay before such notice is given to him.

The unfairness of prejudicing a charging party’s right

of suit because of acts or omissions of EEOC over which

he has no control is manifest.6

In declaring that it was “mandatory” that the Com

mission issue notice, the district court may have been

suggesting, however, that since appellants were entitled

to demand that notice be sent any time after the sixty

(60)-day period had run, their failure to make such a

demand acted as a waiver of their right to bring suit.

Appellants agree that 29 C.F.R. §1001.25a(b) grants to ag

grieved parties the right to demand notice immediately

after the mandatory waiting period has run, and to file

6 In another context— in regard to whether the right to sue under

Title VII should be denied because EEOC had not engaged in con

ciliation efforts prior to suit— a number of courts have recognized

this unfairness, in upholding the right to sue. “ To require more

would be to deny a complainant the right to seek redress in the

courts, resulting wholly from circumstances beyond her control.”

Evenson v. Northwest Airlines, Inc., 268 F. Supp. 29, 31 (E.D. Va.

1967). Also in Mondy, supra, at 263:

But 42 U.S.C.A. §2000e-5(e) sets out only two requirements

for an aggrieved party before he can sue: (1) he must file a

charge with the E.E.O.C., and (2) he must receive the statu

tory notice from the E.E.O.C. that it has been unable to obtain

voluntary compliance. There is nothing more that a person

can do, and this Court will not ask that he be responsible for

the Commission’s failure to conciliate, as that body’s inaction

is beyond the control of the charging party.

Accord: Reese v. Atlantic Steel Co., supra; Quarles v. Philip Mor

ris, Inc., 271 F. Supp. 842, 846-7 (E.D. Va. 1967) ; Ward v. Fire

stone Tire and Rubber Co., 250 F. Supp. 579, 580 (W.D. Tenn.

1966) (dicta). Contra: Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Railway,

supra (presently on appeal to this Court).

-r

suit. But that section does not require them to demand

notice within sixty (60) days or be barred from filing suit.

As originally passed in the House, Title VII gave EEOC

pow er-to- isstie 'cease-and-desist orders to be enforced

in the federal courts, ll.lt. 7152, 110 Cong. Rec. 2805

(daily ed. 2/10/64). When the Senate modified these

procedures to give the EEOC only informal conciliatory

powers, it compensated by assuring aggrieved parties a

right to a day in court. Section 706(e) was designed to

insure that the right to sue could not be obstructed by

delays in Commission action. As Senator Javits ex

plained in reference to the effect the Commission’s failure

to find reasonable cause had upon charging party’s right

to sue:

“ Mr. President, this provision gives the Commission

time in which to find that there exists a pattern or

practice, and it also gives the Commission time to

notify the complainant whether it lias or has not been

successful in bringing about conciliation.

# • #

“But, Mr. President, that is not a condition precedent

to the action of taking a defendant into court. A com

plainant has an absolute right to go into court, and

this provision does not effect that right at all.” 110

Cong. Rec. 14191 (June 17, 1964).

The experience under older state Fair Employment

Practice legislation made it clear that conciliation is often

a slow, complex and cumbersome process/ In fashioning

7 “One administrative weakness observable in virtually all exist

ing commissions is the tendency, in dealing with exceptionally

resistance nonconipliers, to prolong conciliation efforts over unduly

long periods, in preference to involving the public hearing and

cease-and-desist order procedures. The commissions have exhibited

this tendency most frequently in eases involving related compliance

1 2

Title VII, Congress was aware that if it placed the in

formal procedures which it had created under a rigid

timetable, the usefulness of the Title would be destroyed.

Xot only would most conciliations be cut short before,

or just as, they reached a fruitful stage, but the character

of the entire procedure would be drastically affected.

Frank and productive discussions would be prevented,

because both parties would know that litigation was in

evitable, and the conciliation stage would serve only as

an empty prelude to resolution of the dispute in court.

Thus, the parties would often be propelled into court

before cither so desired. Congress intended no such minor

role for conciliation, and it took important steps to insure

that it did not take place in the shadow of the courtroom.

For example, it expressly provided that nothing said or

don'e during the informal negotiations may be used in a

subsequent proceeding (Section 706(a)).

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission has

confronted the difficulties raised by the complex and lengthy

negotiations which it must undertake, and it has devised

procedures to deal with them. To this end, Section

I601.25a(b) of its regulations provides that notice under

Section 706(e) will not automatically issue after sixty (60)

cases. The reluctance of the commissions to invoke the mandatory

and legal-sanction features of the FEP laws appears to stem from

a desire to create and preserve a public image of the governmental

anti-discrimination effort as primarily a persuasive process, by

keeping the evidence of coercion at a minimum level. It seems ap

parent, however, that the net effect of the propensity to stretch out

the conciliation process is to reduce the commissions’ over-all effec

tiveness, mainly because it encourages determined noncompliers to

continue flouting the law, but also because it consumes a dispro

portionate amount of the commissions’ time and resources.”

Xorgrcn and Hill, Toward Fair Employment (1964), at p. 270.

See also Hill, Twenty Years of State Fair Employment Practice

Commissions: .1 Critical Analysis With Recommendations, 14 Buf

falo L. ltcv. 22 (1064).

13 —

days if there has not yet been a finding as to reasonable

cause or an effort at conciliation, even though this might

take considerably longer than the sixty (60)-day waiting

period.

The effect of this regulation is to allow the conciliation

process to continue so long as all parties prefer it to the

public forum; it thus encourages conciliation as an effec

tive procedure when conditions are ripe for a successful

settlement. At the same time, it preserves the aggrieved

parties’ right to sue when they feel that only a court can

offer adequate relief. This purpose was made clear at

the time that the Commission announced its rule:

The Commission believes that in general the purposes

of Title VII are better served by delaying the notifica

tion under Section 706(e) until the proceedings before

the Commission have been completed. However, we

recognize that there may be circumstances under which

either the charging party or the respondent may de

sire that the right to bring ah action accrue as promptly

as possible upon the expiration of the 60-day period,

and where such a desire is clearly manifested, we

believe it consistent with the statutory scheme that

notification issue irrespective of the status of the

case before the Commission. Accordingly, this amend

ment is intended to state clearly the circumstances

under which the Commission will issue notification of

its failure to achieve voluntary compliance pursuant

to Section 706(e) of the Act. 31 Fed. Keg. 14255

(Nov. 4, 1966).

Moreover, the regulation is careful not to leave the re

spondent at the mercy o f the charging parly. If the re

spondent believes that conciliation will lie unfruitful, or

desires to have his reputation vindicated quickly and

14

publicly after sixty (60) days have passed, lie need only

demand that notice issue. Under the Commission’s rule

neither party is at the peril of excessive delay or useless

negotiations, but fruitful negotiations are not abruptly

and wastefully brought to an end when both sides wish

them to continue. The Commission’s regulation gives life

to both parts of what one court has termed Title V II’s

“ split personality.” 1I all v. Werthan Bag Corp., 251 F.

Supp. 184, 187 (M.D. Tenn. 1966).

If appellees were burdened by this delay, if they desired

an immediate resolution of the charges against them,

they had only to request that notice be sent to the plain

tiffs. The Commission’s procedure under 29 C.F.R.

§1601.25a(b) was open to appellees in this case, and sixty

_(60) days after the charges were tiled they could have

^requested EEOC to notify appellants of their right to

̂ sue. ' Appellees chose not to invoke this privilege, per

haps because they believed that the private and informal

proceedings would bear fruit. Whatever the reason, ap

pellees are in no position now to object to appellants’

purported lack of timeliness.

For the foregoing reasons appellants respectfully submit

that the district court erred in holding that their suit

was untimely filed.

15

II.

The District Court erred in holding that this action

could not he maintained as a class action.

Appellants’ charges of discrimination (E. 60) fdcd with

EEOC alleged that appellees had discriminated against

“ Complainants and Negroes generally” by grouping them

in segregated lines of progression with the lowest job

ranks and pay scales, by denying them promotions on

the basis oi race; by making them take unrelated ex

aminations as a condition to promotion and advancement;

by paying them less than whites doing the same jobs

(R. 62), and by denying them access to the apprenticeship

program (R. 63). Accordingly, the complaint (It. 1) filed

on June 9, 1967, was a class action, on behalf of appellants

and other Negro persons similarly situated who were

employed or might be employed by International Paper

Company, Southern Kraft Division, Moss Point, Mis

sissippi (paragraph IV), averring that appellees dis-

crimnated against appellants and this class generally, and

seeking class relief.8

The district court held that the suit could not be main

tained as a class action, stating:

The action is instituted by and on behalf o f named

plaintiffs and other unnamed male Negroes said to

be too numerous to mention under Civil Rule 23.

For the reasons hereinafter more specifically as

signed, it is clear to this Court Ijgat a class action

cannot he instituted and maintained under the proce

dural provisions ot this enactment by any anonymous

.inn

■ 'I .

■I V.ll i -• J > ■ • I -1 f i • * I . Inf nit h

fr l • . < . I.1 f . • ? * , ’ 'itf ■ f 1 t.r

f Ilf . (,.<ft • •

16

group of people. Specifically, no person is entitled

y to the benefits of the act who has not strictly com

plied with the conditions precedent to the right to

institute a suit of this kind in a federal court. Section

2000e-5(a) (1) makes it abundantly clear that an ag

grieved person must first file a charge with the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and that

such person claiming to be aggrieved shall within

a given time institute a suit in a United States Dis

trict Court to redress his grievance, if such action

is to be instituted. This suit is purely statutory.

It is a creature of statute and Congress as creator

of such right of action has strictly and sharply de

fined its method of enjoyment. No class action may

V' be maintained in a situation of this kind where it must

* be shown that each plaintiff has exhausted his ad

ministrative remedies, and has brought the consequent

action within the time provided by statute. The ques

tions of law and fact are thus not common to the

entire class and the claims and defenses of the repre

sentative parties are not the same and are not en

tirely typical of the other claims and defenses as

required by Civil Rule 23(a). The purpose and effect

of a class action is incompatible with the require

ments of this statutory scheme as a condition precedent

to the right of enjoyment of its benefits. It is ac

cordingly the considered view of this Court that this

suit cannot be maintained as a class action (R. 55-56).

It is not clear whether the district court held that no

class action whatsoever may be brought under Title VII,

or whether it held that in such an action the class repre

sented by named plaintiffs must bo limited to persons who

have previously exhausted their administrative remedies;

accordingly, appellants discuss these issues separately.

17

A. A class action is maintainable under Title VII.

The uncontroverted averments of the complaint bring it

squarely within the requirements of Rules 23(a) and

,_23.Cb)-(2) of'the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure:

23(a)(1). The class of Negro employees (and prospec

tive employees) of the Moss Point plant of the Inter

national Paper Company is plainly so numerous that

joinder of all members is impracticable.9

23(a)(2). The right to relief for all members of the

class originates in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 ;10 the class as a whole is injured by the appellees’

general policies of racial discrimination in the institution

and application of tests, promotion and seniority systems.11

23(a)(3). Appellants’ claims arise out of appellees’

general policies of discrimination in testing, promotion,

and seniority.12

23(a)(4). Appellants’ averment that they fairly and

adequately protect the interest of the entire class13 has

not been controverted by appellees.

23(b)(2). The appellees’ general policies and conduct of

discriminating in testing, promotion, and seniority are

based on the fact that the persons discriminated against

are employed and potentional employees of the Negro

race, and it is in terms of this race that the class is defined.14

9 Complaint, III. The number of employees at the Moss Point

plant is not in evidence; however, the complaint avers that there

arc over 100. IV (A ).

10 Complaint, I.

“ Complaint, V I (A ) , VII.

15 Complaint, V 1. VII.

“ Complaint, VII

“ * "omplniut 111

18

The relief sought, inter alia, is an injunction prohibiting

discrimination against appellants and the entire class.

As the court stated in Ilall v. Wertlian Bag, supra,

at 186: “ [Rjacial discrimination is by definition a class

discrimination. If it exists, it applies throughout the

class.” Class actions are the most appropriate device

for persons challenging and seeking broad injunctive relief

against racial discrimination. The most appropriate sec

tion of Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

for the maintenance of his class action is (b)(2). Indeed,

this action is the model which (b )(2) was designed to

include. The comment of the advisory committee which

prepared the new Rule 23 makes this crystal clear.

Subdivision (b )(2). This subdivision is intended to

* reach situations where a party has taken action or

refused to take action with respect to a class, and

final relief of an injunctive nature or of a correspond

ing declaratory nature, settling the legality of the

behavior with respect to the class as a whole, is

appropriate. Declaratory relief ‘corresponds’ to in

junctive relief when as a practical matter it affords

injunctive relief or serves as a basis for later in

junctive relief. The subdivision does not extend to

cases in which the appropriate final relief relates ex

clusively or predominantly to money damages.

Action or inaction is directed to a class within the

meaning of this subdivision even if it has taken

effect or is threatened only as to one or a few members

of the class, provided it is based on grounds which

have general application to the class.

Illustrative are various actions in the civil-rights field

where a party is charged with discriminating unlaw

fully against a class, usually one whose members are

19

incapable of specific enumeration. (Advisory Com

mittee Note to amended Rule 23, 86 Sup. Ct. No. 11,

Yellow Supp. at 34 (1966) (reprinted in 28 U.S.C.A.,

F.R.C.R, ,17-33, following Rule 23). (Emphasis

added.))

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in Lance v. Plummer,

353 F.2d 585 (5th Cir. 1965), cert, denied. 384 U.S. 929

(1966), a case interpreting Title II of (he Civil Rights

Act of 1964, has ruled that a class action may be main

tained in actions arising under that Title. Title II (dealing

with public accommodations) authorizes in Section 204(a)

a private action by a. “person aggrieved” by unlawful dis

crimination. Title VII is virtually identical in this respect

to Title II, including the use of the same term “ person . . .

aggrieved” . The Fifth Circuit stated:

“ We do not find this argument persuasive. . . . We

conclude that Congress did not intend to do away with

the right of named persons to proceed by a class action

for enforcement of the rights contained in Title II of

the Civil Rights Act.” 353 F.2d at 591.

*

To counsel’s knowledge, every court that has considered

the question has held that a class action can be maintained

under Title VII. Hall, v. Wertlian Bag Carp., supra;

Hicks v. Crown-Zellerbach Corp., No. 16638 (E.D. La.

June 13, 1967); Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 271 F.

Supp. 27 (E.D. N.C. 1967); Robinson v. / ’. Larillard Co.,

Case No.'C-141-0-66 (M.D. N.C. January 26, 1967); An

thony v. Brooks, 65 LRKM 3074 (N.l). kti. 1967); Brians

v. Puke Power Co.. 67 LRKM 2616 (M.D. VC. 1967);

Quarles v. Phihji Monis. toe,, 67 1,1,'|»M 2",,M ( )•; D. \’n

ODD). v r „ l , r o , 273 r Kuril 332

̂S ! * 1 ? »j ] ) I*i J • tt 11»> 9 v / » 9 ,{ 1 /.i * (' t ‘S; j

2 0

that a class action could be maintained under Title VII,

but held that the case before him was, on its facts, in

appropriate for the class action procedure.

Nothing in the text of Title VII or its legislative history

speaks against class actions, and, indeed, the Equal Em

ployment Opportunity Commission in an Opinion Letter

(February 3, 1906) explicitly provides:

“ A person claiming to be aggrieved who brings suit

under Section 706(e) of Title VII may maintain a

class action, pursuant to the provisions of Rule 23(a),

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Other employees

of the employer may intervene as parties plaintiff,

notwithstanding the fact that they did not file a charge.”

CCI1 Employment Practices Guide 17,252, p. 7371.

Constructions and interpretations by agencies charged with

the administration of federal statutes are entitled to great

weight. See the discussion in argument I, supra, pp. 8-9.

B. Named plaintiffs may represent a class the members

of which have not pursued the administrative reme

dies of Title VII.

To hold that a class action can be maintained under

Title VII, but that each member of the class must have ex

hausted the administrative remedies provided by Title

VII, is to hold, for all practical purposes, that a class action

cannot be maintained under Title VII. The class which ap

pellants represent is partly composed of Negro persons

similarly situated who may be employed by the appellee

company in the future and an injunction is sought enjoining

the appellees from discriminating against appellants and

members of the class in the future. The persons who may

21

be employed and who may be subjected to racial discrimina

tion are not yet sufficiently defined so as to enable each

of them to file charges with EEOC. Tims, the basic and

significant question before this Court must be whether a

class action can be maintained by persons (such as the

appellants herein) who have exhausted flic administrative

remedies, on their own behalf and on behalf of others

similarly situated but who themselves have not pursued

the administrative remedies of Title VII.

At least five district courts have recognized that, in

class actions under Title VII, the class may be composed of

persons who have not filed charges with EEOC.16 In Hall

v. Werthan Bag Corp., supra at 188 the court stated:

What this court conceives to be the true purpose of

this requirement would not be served by restricting the

class for whose benefit this action may be maintained

to only those Negro employees or would-be employees

of the defendant who have resorted to the Commission,

that is, to Robert Hall alone, for he is admittedly the

only such person who has exhausted Commission pro

cedure.

The identical conclusion was reached by Judge Ileebe in

Hicks v. Crown-Zellerbacli, supra. There, Judge Ileebe

permitted a class action to be maintained and permitted

a plaintiff who had filed a charge with EEOC to represent

all employees in the Box Plant, even though no other em

ployee had filed a charge with EEOC. In Quarles v. Philip

Morris Co., supra, a class action was maintained by (wo

Negio plaintiffs. One plaintiff alleged (hat he was denied

a transfer lie sought because of his race and color. The

i ( / v . i t „ / V ( ' m i n i / < V, r i , 1 " T ) J.' S i i t u i

f . . . . - . . , . . . ’ • ' . ' 11 V

2 2

second plaintiff alleged that the company paid him a lower

wage rate for a job comparable to jobs performed by white

employees who were paid at a higher rate of pay. The

court allowed a class action to be maintained and permitted

plaintiffs to represent and to introduce evidence concerning

Negro persons who were discriminated against in hiring

and in promotion. In holding that a class action could be

maintained, Judge Butzner stated: “ [T]he effect of the

court’s ruling was to hold that each member of the class

was not required to pursue administrative relief for the

correction of the same employment practices.” at 2099.

Implicit in the decisions in both Lea, et al. v. Cone Mills

Corp., No. C-176-D-66 (M.D. N.C. June 27, 1967), and

Griggs v. 'Duke Power Co., supra, is a finding that a class

-> action may be maintained in behalf of persons who them

selves have not filed charges with EEOC. In Moody v.

Albemarle Paper Company, supra at 29, the court held

that: “ [A] 11 potential parties in a class action seeking relief

under the act [Title VII] are not required to have all

joined in as a group or class in the prior written complaint

to the Commission.” The court indicated it was following

the rationale of Hall in this respect. If it is not a pre

requisite for a named plaintiff to have filed a charge with

EEOC, most certainly, it should not be a prerequisite for

a member of the class represented by the plaintiff.

The statute and legislative history do not speak directly

to the issue, but, as the court in Hall v. Wertlian Bag Corp.,

supra, at 186-187, noted, they are suggestive:

Section 706(i), for example, provides for a form of

supervision by the Commission over matters arising

as a result of a court’s order entered in a Title VII

proceeding which suggests that Congress contemplated

a scope of relief reaching beyond the limited interests

- 2 3

of the single “person aggrieved.” Likewise, Section

706(g) provides that a court “ may enjoin the respon

dent from engaging in such unlawful employment

practice, and order such affirmative action as may be

appropriate, which may include reinstatement or hiring

of employees, with or without back pay * * * .” And as

one commentator has observed, “This language is sub

stantially unchanged from that in Section 707(e) of

the Ilouse-passed bill, and in the context of that bill

it clearly meant that the court should enjoin the sub

sequent commission of unlawful employment practices

in as broad terms as would have been proper for a

cease-and-desist order under the NLBA.”

[There is] a dichotomy in the philosophy underlying

the enforcement provisions of Title V II: emphasis

is placed primarily on protection of persons subject to

discrimination rather than on protection of the public

interest, but for the protection of persons subject

to discrimination, Congress apparently envisioned a

rather broad scope of relief similar to that which would

be necessary for the protection of the public interest.

A privately instituted class action is unique in its

adaptability to Title V II’s split personality.

The administrative.remedies provided by Title VII serve

the function of notifying the respondent of the charges

made against him, and giving him, the complaining party,

and the EEOC the opportunity to work out the grievances

through conciliation, in private, with the hope that mutual

agreement can be achieved. But conciliation goes beyond the

particular grievance of the complaining party:

The Commission’s conciliation program was based on

a two-fold objective; firstly, to obtain prompt and

appropriate relief for the charging party, and secondly,

lo seek a remedy for the underlying problem o f dis-

24

crimination. A charge of job discrimination is fre

quently a symptom of wide-spread disease. By its

very nature, discrimination is often not personal but

generalized, often not an act of individual malice but

more an element of a pattern of customary conduct.

This discrimination may be limited Jo a small depart

ment, or extend to an entire industry or region. EEOC

conciliation approaches the individual complaint on

the grounds that it may lead to improving the employ

ment status for every individual who has felt the

press of discrimination.

The foundation upon which the Commission’s con

ciliation is based, as well as its starting point, is the

finding that reasonable cause exists for the discrimina-

0 tion charge. The question of whether there has been

discrimination or not is, then, not posed by the concilia

tor ; he works on the solution of the specific problem

of discrimination, as well as the underlying problems

related to it. EEOC, First Annual Report, p. 17.

Where, as in the present case, the issues raised on behalf

of the class—the plant-wide practice of discrimination in

testing, promotion, and seniority—were raised by the

parties in the charge of discrimination to the EEOC, their

subsequent suit cannot properly be limited to personal

relief. As Judge Heebe held in Hides v. Crown Zellerbach

Corp., supra, at 6-7:

Once the administrative remedy has been fairly ex

hausted by one person as to an issue, we see absolutely

no need, and in fact only wasted effort, in requiiing

that before the Court act broadly as to that issue,

every person affected thereby initiate and prosecute

a complaint which will not be successful. Nor requiring

[sic] these certainly purposeless administrative pro-

l

cccdings deprive the employer of nothing—he cannot

be heard to say that lie might have decided to bow

to the persuasive powers of the Commission of other

complainants had been filed, for the opportunity to

voluntarily comply was not only presented once and

refused, but remains always open during the pendency

of the judicial proceedings.

For the foregoing reasons, appellants submit that a

class action may be maintained under Title VII and the

class may be composed of persons similarly situated who

themselves have not filed charges with EEOC.

III.

The District Court erred in assessing appellants for

$250 attorneys fees and costs, payable to appellee Inter

national Paper Company.

The district court ordered that appellants be assessed

with all costs, including “ a reasonable attorney’s fee to

defendant, International Paper Company, in the amount of

$250.00, for failure of plaintiffs to appear at a deposition

on July 8, 1967” (R. 75).16 The facts relevant to the im

position of this penalty are as follows.

On June 28, 1967, the appellee unions filed a Notice to

Take Deposition Upon Oral Examination of all appellants,

the depositions to begin “ on Wednesday, July 5, 1967, begin

ning at 2:00 P.M. on said day, and continuing thereafter

from day to day as the depositions may be adjourned and

until the depositions of each of said Plaintiffs named herein

shall have been completed. . . .” (R. 25). Depositions began

" I n its (It, fiH) mid jiidi’ iiif-iit (It 751. I fir dr.triVf

« rrrn iipou** !v st.’i t r s fh / i f / t j*|h ||mfM•. f<» ur /if n

'I-ruriri j "

26

on July 5, and continued on Thursday and Friday, July 6

and 7. The unions called appellant J. P. Miller as their

first witness on July 5, and continued their examination of

Miller on Thursday and Friday, completing it at 6:25 P.M.

Friday afternoon (R. 39).

At the resumption of depositions on Friday afternoon

(R. 37), and again at the close of depositions that day (R.

3S, 40), appellants’ counsel informed counsel for appellees

that they would be unable to continue the depositions on

Saturday. Miss Kirk, one of the counsel for appellants, had

other, urgent business that could not be delayed (R. 51).

Mrs. Brest, the other counsel, also had urgent business, and

she fell ill with a kidney infection on Friday and was re

quired to remain in bed for several days thereafter (R. 53).

•> Counsel for appellants had attempted to arrange for

another attorney to take over, but without success (R. 53).

They stated that they were “willing to proceed after the

weekend” or at any other convenient time (R. 40). Appel

lees would not agree to postponing resumption of the depo

sitions to a later date. Rather, Mr. Pyles, counsel for the

appellee unions, “announced and insisted”

to everybody that I will be here in the morning at

9:00 A.M. to continue the taking of these depositions

and I assure you that if I and the Court Reporter are

the only ones here, I shall ask the plaintiffs to show

cause. I intend to put the witnesses on the stand and

examine them (R. 39).

Counsel for the Company stated that they would also be

present. Appellants’ counsel made it clear that they could

not appear on Saturday, and in appellees’ presence, in

structed the appellants-deponents not to appear since their

counsel could not be present (R. 40-41).

27

True to their word, appellees had a court reporter pres

ent on Saturday (R. 20-21). On July 20, 1967, the appellee

company filed a motion to dismiss, and for costs, expenses,

and attorneys fees, based upon appellants’ failure to at-

~tend the depositions on Saturday, July 8 (R. 21-22); July

20, 1967, appellee unions filed a motion to dismiss on the

same grounds (R. 26-30). The district court declined to

dismiss the action, but assessed appellants with a $250

penal ty.

Rule 30(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure re

quires that a notice of deposition “ state the time . . . for

taking the depositions.” The appellee unions noted deposi

tions to “ continue from day to day” until depositions of all

of appellants had been completed. Appellants do not object

per se to the use of the intentionally indefinite phrase

“ from day to day” , but contend that if it is to be used

in lieu of specific dates, it must be construed in the context

of ordinary business practice. Appellants respectfully sub

mit that the court may take judicial notice that Saturday,

though not an official holiday, is also not an ordinary busi

ness day for attorneys. This is not to say that lawyers do

not work on Saturdays (and sometimes on Sundays as

well), but the work is usually internal—“catching up” on

the week’s business—and lawyers’ offices, like the courts,

are usually closed for regular business on Saturday. Ab

sent some agreement among counsel, or the unopposed ex

plicit specification of Saturday in a notice of deposition,

“from day to day” cannot properly be construed to include

Saturday. ^

Of course there may be special circumstances, such as

the inability of counsel to take depositions on weekdays,

oi the necessity of immediate discovery for emergency

disposition of the matter in suit, which make weekends

appropriate days for 111«• taking of d ep osition ", tbit there

28

were no special circumstances in the case at bar. Appellees

were in no hurry. Indeed, although appellees planned to

take the depositions of all of appellants (R. 25), by the

afternoon of Friday, July 7, the appellee unions had com

pleted their examination of only the first of the five appel

lants (R. 53; deposition of J. P. Miller (not transcribed));

neither the appellee company nor appellants had yet ex

amined him; and appellees were not planning to resume

s/ taking of depositions on Monday, but rather were planning

to recess the taking of the depositions for approximately

three weeks (R. 40, 53).

Until Friday afternoon, July 7, appellants had no rea

son to expect that appellees would insist on continuing

the taking of 'depositions on Saturday. Appellees argued

a to the district court below that appellants should, at that

point, have moved for a protective order pursuant to

Rule 30(b) of the Federal Rules. But it would have been

virtually impossible to file papers, or even to find one

of the two judges in the Southern District of Mississippi

for presentation of an oral motion, on Friday afternoon.

Indeed, had appellants adjourned the Friday afternoon

depositions for this purpose, appellees would legitimately

have complained to the court of the time and expense,

since Mr. Adams had come from Mobile for the deposi

tions, and since the unions had hired, and had present,

a court reporter.

Even assuming, arguendo, the appellants’ counsel acted

impropSSly in failing to proceed with the depositions on

Saturday, the award of $250 counsel fee to the appellee

International Paper Company was excessive and improper.

Appellants unequivocally stated at the close of the Friday

session that neither counsel nor appellants themselves

would lie present Saturday. Appellees’ expenses in hiring

a court reporter to appear on Saturday, and in appearing

.

" |

I

20 — --------------------------------------------------------------

themselves, wore foolish and wasteful—not only did ap

pellees fail to mitigate damages; what expenses they in

curred were entirely of their own making. Finally, as

suming that appellants were liable to pay attorneys fees

to anyone, it was certainly not, as the court ordered, to

the International Paper Company, which neither noticed

the depositions nor filed any document joining in the notice

filed by the appellee unions. The unions did not move for

damages or attorneys fees.

CONCLUSION

For all the foregoing reasons, the order of the district

court dismissing the action as untimely filed, holding that

it cannot be maintained as a class action, and assessing

appellants with $250 in costs and attorneys fees, should

be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reenberg

J am es M . N abrit , III

R obert B elton

G abrielle A . K irk

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

M arian E. W righ t

(Reu ben V. A nderson

, P a u l A . B rest

I ris B rest

538V2 N. Parish Street

Jackson, - Mississippi 39202

Attorneys for Appellants

A lbert J. Rosenthal

135 W est llfith SI reel

New York, New York 10027

30

Certificate of Service

This is to certify that the undersigned, one of Appel

lants’ attorneys, on this date, May — , 1968, has served

two copies of the foregoing Brief for Appellants on

Honorable C. W. Ford, Post Office Box 100, Pascagoula,

Mississippi; Honorable Robert F. Adams, Post Office Box

1958, Mobile, Alabama; Honorable Warren Woods, 1735

K Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20006; Honorable Ben

Wyle, 2 Park Avenue, New York, New York 10016; Sher

man an<l Dunn, 1200 East 15th Street, N.W, Washington,

D.C. and Honorable Dixon L. Pyles, 507 Last Pearl Stieet,

Jackson, Missisisippi/by United States air mail, postage

prepaid.

................................

l A ^ A t t o r n e y for Appellants

T - r

r > r d/.nrd .v.’ -i-, ----------vv' ;

, V x . » C I t Ai ' Co.<r ir-"- ■ y L / ’

i

1\ .

i|

I

j

i

I

i

i

Order in Lea v. Cone Mills

I n the United States D istrict Court

F or the M iddle District of North Carolina

(j REENSBORO D IVISIO N

C i v i l A c t i o n No. C-176-D-66

S hirley Lea, R omona P innix and A nnie T innin ,

Plaintiffs,

v.

Cone M ills Corporation, a corporation,

Defendant.

Order

This cause coining on to bo heard before the undersigned

upon motion of defendant to dismiss and for a determina

tion whether this cause may be prosecuted as a class action

and upon motion of plaintiffs to strike defendant’s demand

for trial by jury and to inspect the record of part of de

fendant’s answers to plaintiffs’ interrogatories 22, 24, 26

and 51, which were ordered filed under seal with the Clerk

of Court, and it appearing to the Court upon the pleadings,

exhibits, briefs and arguments of counsel for both parties

that the defendant’s motion to dismiss and motion for deter

mination by the Court that this is not a proper class action

should be denied. It further appears to the Court that

plaintiffs’ motion to inspect the record of answers to in

to, rotatories ordered to be filed under seal should be denied

and that the ( our! should defer ruling upon plaintiffs’

motion to strike demand for jury trial until final pre trial

ronf.-r.

In.

2a

Order in Lea v. Cone Mills

It is , therefore , ordered, adjudged and decreed :

1. That defendant’s motion to dismiss be and the same

is hereby denied.

2. That this is a proper class action and may be prose

cuted as such pursuant to Rule 23(a), (b)(2) of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure. The Court finding that this is

a proper class action under Rule (b) (2), no notice to mem

bers of the class need be given at this time.

Pursuant to Rule 23(c) the Court finds that the class

here involved are all Negroes who are or who might be

aifected by any racially discriminatory policies or prac

tices of defendant, should the Court find any such practices,

'at defendant’s Eno Plant in Hillsborough, North Carolina.

This ruling is conditional and may be amended, modified

or altered at any time prior to. final determination of this

cause on the merits.

3. That plaintiffs’ motion to inspect the answers of

defendant to plaintiffs’ interrogatories 22, 24, 26 and 51

which were ordered filed under seal with the Clerk of Court

be and the same is hereby denied.

4. That ruling by the Court on plaintiffs’ motion to

strike defendant’s demand for jury trial be deferred pend

ing the final pre-trial conference of this case.

This 27th day of June, 1967.

E ugene A. G ordan

J udge, U n ited S tates D istrict Court

Approved as to form:

Counsel for Defendant

Counsel for Plaintiffs

3 a

In t h e U n ited S tates D istrict C ourt

F or t h e M iddle D istrict of N orth C arolina

.Greenshoro D ivision

Case No. C-141-G-66

Order in Robinson v. Lorillard

D oroth y P. R obin son , et al.,

vs

Plaintiff,

P. L orillard Co m p a n y ,

Defendant.

M em oran du m

This matter was scheduled for hearing in the United

States Courtroom, Greensboro, North Carolina, on January

19, 1967, on all pending motions and objections to inter

rogatories. J. Levonne Chambers, Esquire, Robert Belton,

Esquiie, and Sammie Chess, Esquire, appeared as counsel

for the plaintiff; Thornton II. Brooks, Esquire, Robert G.

Sanders, Esquire, and Larry Thomas Black, Esquire, ap

peared as counsel for the defendant; Frank Schwelb, Es

quire, and Miss Monica Gallagher appeared as counsel for

the intervenor.

lhc luling of the Court on the various motions and ob

jections is as follows;

T]lf> objection filed October 10, 1906, by (be defendant

Tobacco Workers International ITiion AFL (TO, to Inter

rogator v 13, winch interrogatory, among other'*, win filed

4a

2. The motion, filed November 23, 1966, of the plaintiff

to require further answers of P. Lorillard Company to

Interrogatories 18-25 inclusive so as to have the answers

include the period between July 2, 1964, to September 23,

1966, the Interrogatories having been filed September 29,

1966, is allowed, limited, however, to answers concerning

the Greensboro Plant, and the motion is denied as to Inter

rogatory 36.

3. The motion of the defendants filed November 8, 1966,

by the Tobacco Workers International Union AFL-CIO,

and Tobacco .Workers International Union AFL-CIO,

Local 317, to dismiss under Rule 12 of the Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure is denied.

4. The motion of the defendant P. Lorillard Company,

filed November 1, 1966, to dismiss under Rule 12 of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure is denied.

5. With respect to the motion of the defendants Tobacco

Workers International Union, AFL-CIO, and Tobacco

Workers International Union, AFL-CIO, Local 317, motion

that the Court determine whether the action may be prose

cuted as a class action pursuant to Rule 23, et seq. of the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, it is the considered

judgment of the Court that this case is properly a class

action and in category a Rule 23 (a) (b) (2) action. Accord

ingly, counsel for the plaintiff will prepare and present to

the Court a proposed Order, first presenting same to

counsel for the defendant, in order that objections, if any,

may first be made by the defendants. The proposed Order

will state that it is conditional and subject to alteration or

Order in Robinson v. Lorillard

5a - —

amendment at any time prior to the final decision on the

merits.

Also, counsel for the plaintiff will prepare and present to

the Court an Order incorporating in all respects the ruling

of the Court on the respective motions and objections, first

presenting a copy of same to counsel for the defendants and

the intervenors.

I, Graham Erlacher, Official Reporter of the United States

District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina,

do hereby certify that the foregoing is a true transcript

from my notes of the entires made in the above-entitled

Case No. C-141-G-66,. before and by Judge Eugene A.

Gordon on January 19, 1967, in Greensboro, North Caro

lina; and I do hereby further certify that a copy of this

transcript was mailed to each of the below-named attorneys

on January 26, 1967.

Given under my hand this 26th day of January, 1967.

G rah am E rlach er

Official Reporter

cc.: J. Levonne Chambers, Esq.

Robert Belton, Esq.

Sammie Chess, Esq.

Thornton R. Brooks, Esq.

Robert G. Sanders, Esq.

Larry Thomas Black, Esq.

Frank Schwclb, Esq.

Miss Monica Gallagher

Order in Robinson v. Lorillard