NAACP v. St. Louis-San Francisco RY. Co. Brief for Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Company et al.

Public Court Documents

October 18, 1954

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP v. St. Louis-San Francisco RY. Co. Brief for Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Company et al., 1954. 939f8946-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5217a6d3-3127-4fed-a2fc-eaf30fd1ea10/naacp-v-st-louis-san-francisco-ry-co-brief-for-atlantic-coast-line-railroad-company-et-al. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

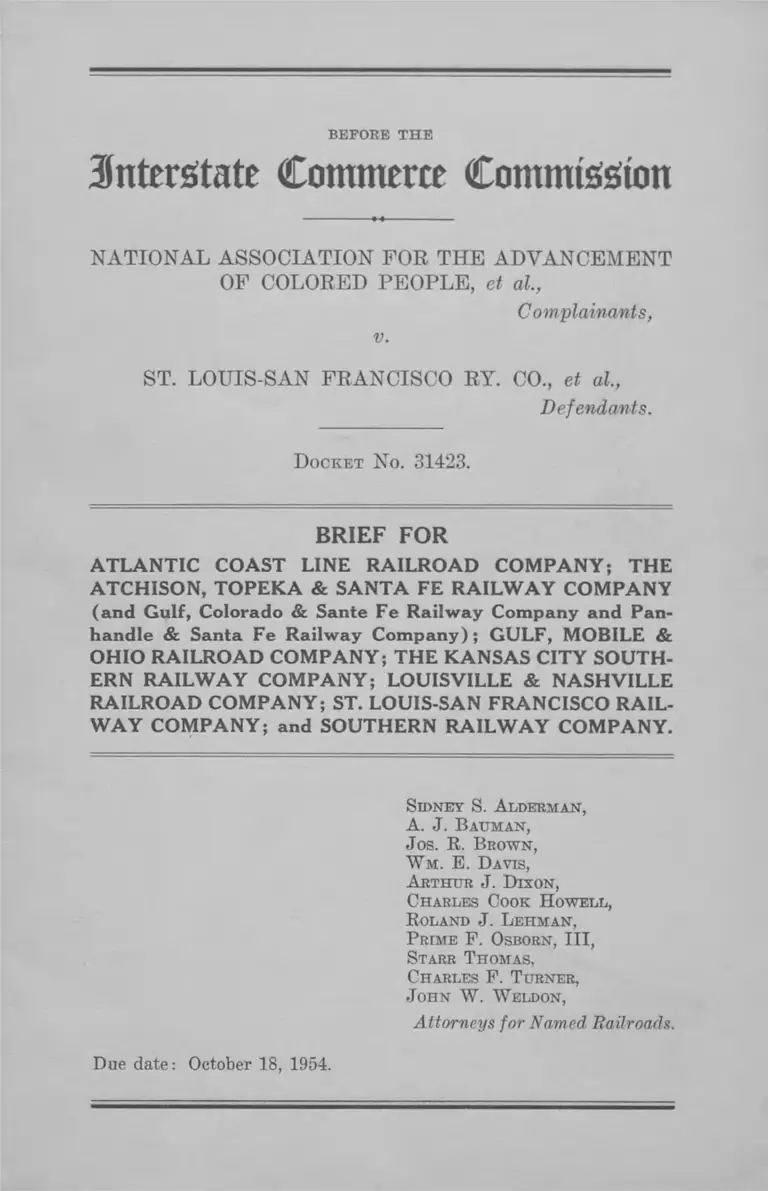

BEFORE TH E

interstate Commerce Commission

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT

OF COLORED PEOPLE, et al.,

Complainants,

v.

ST. LOUIS-SAN FRANCISCO RY. CO., et al.,

Defendants.

Docket No. 31423.

BRIEF FOR

ATLANTIC COAST LINE RAILROAD COMPANY; THE

ATCHISON, TOPEKA & SANTA FE RAILWAY COMPANY

(and Gulf, Colorado & Sante Fe Railway Company and Pan

handle & Santa Fe Railway Company); GULF, MOBILE &

OHIO RAILROAD COMPANY; THE KANSAS CITY SOUTH

ERN RAILWAY COMPANY; LOUISVILLE & NASHVILLE

RAILROAD COMPANY; ST. LOUIS-SAN FRANCISCO RAIL

W A Y COMPANY; and SOUTHERN RAILWAY COMPANY.

S id n e y S. A l d e r m a n ,

A . J . B a u m a n ,

Jos. R . B r o w n ,

W m . E. D a v is ,

A r t h u r J . D ix o n ,

C h a r l e s C oo k H o w e l l ,

R o la n d J . L e h m a n ,

P r im e F. O sbo rn , III,

S t a r r T h o m a s ,

C h a r l e s F. T u r n e r ,

J o h n W . W e l d o n ,

Attorneys for Named Railroads.

Due date: October 18, 1954.

I N D E X .

PAGE

The Complaint.................................................................... 2

The Stipulations................................................................ 3

The I ssue ......................................................................... 4

T he H oldings of the Commission------------------------- 4

T he U nited States Supreme Court Cases........... 9

Conclusion ..................................................................... 14

R equest for F indings...................................................... 17

Certificate of Service...................................................... 19

u

Cases Cited.

page

Boyer v. Garrett, 183 F. 2d 582 (1950).................... 11

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) 10,11,

16,17

Chiles v. Chesapeake & Ohio By. Co., 218 U. S. 71

(1910) ....................................................................... 8,11

Councill v. Western and Atlantic R. Co., 1 1. C. R.

638 (1887) ............................................................... 4,5

Dawson v. Baltimore, Civil No. 5847 (D. C. Md.

1954) ......................................................................... 11

Georgia Edwards v. Nashville C & St. L. By. Co.,

12 I. C. C. 247 (1907)............................................ 7

Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U. S. 485 (1878)........................ 11,12

Heard v. Georgia R. R. Co., 1 1. C. R. 719 (1888)....6,14,17

Henderson v. United States, 339 U. S. 816 (1950).. 11,13

Isaacs y. Baltimore, Civil No. 6879 (D. C. Md.

1954) ......................................................................... 11

Jackson v. Seaboard Air Line R. Co., 269 I. C. C.

399 (1947) ............................................................... 8

Joseph P. Evans v. Chesapeake & Ohio Railway

Co., 92 I. C. C. 713 (1924).................................... 7

Lonesome v. Maxwell, Civil No. 5965 (D. C. Md.

1954) ......................................................................... 11

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 80 (1941).....11,12,13

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 (1946)............... 11,13

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 (1896).......10,11,15,17

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629, 636 (1950)........... 10,11

Statutes Cited.

PAGE

Federal Constitution:

Article I, Section 8, Clause 3......................... .....2, 8,13

Fifth Amendment................................................ 2

Fourteenth Amendment .............................. 2, 3,10,11

Thirteenth Amendment...................................... 10

Interstate Commerce Act................................ 2, 4,9,12,16

Section 3(1) ....................................................... 2,13

Section 1(5) ....................................................... 3

Section 2 ............................................................... 3

Miscellaneous.

Hearings before Committee on Interstate and For

eign Commerce on H. R. 563, 1013, 1250, 3890,

7304, 7324, 8088 and 8160, 83rd Congress, 2nd

Session (1954), pages 6, 7, 8 and 9.......................... 9,13

BEFORE TH E

Sntersitate Commerce Commission

National A ssociation for the Advancement of

Colored P eople, et al.,

Complainants,

v.

St. L otjis-San F rancisco B y. Co., et al.,

Defendants.

Docket No. 31423

BRIEF FOR CERTAIN RAILROADS.

This brief is filed on behalf of the following rail

roads, each of which has entered into a separate stipu

lation with the complainants:

Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Company;

The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway Com

pany (and Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Railway

Company, and Panhandle & Santa Fe Railway

Company) ;

Gulf, Mobile & Ohio Railroad Company;

The Kansas City Southern Railway Company;

Louisville & Nashville Railroad Company;

St. Louis-San Francisco Railway Company; and

Southern Railway Company.

The stipulations provide that as to each o f those rail

roads respectively the case is submitted to the Cominis-

2

sion solely upon the basis of the pleadings and the facts

stated in the stipulations. It was so agreed at the hear

ing of July 27,1954 before the Examiner (Tr., pp. 7, 13).

The Complaint.

The complaint is an attempt to have the Commission

declare that segregation1 of passengers of the white and

colored races upon interstate passenger trains is in and

of itself unlawful; and the purpose of the complainants

is stated in the complaint specifically to be:

“ Further, complainant’s primary purpose and

concern is in the elimination of segregation and

discrimination from all segments of American life

in order that colored minorities may enjoy full

and complete citizenship rights in the United

States, its territories and possessions. Among

these citizenship rights is the free, full and unre

stricted use of the facilities and accommodations

available to the public in general operated by

defendants in and affecting interstate commerce” .

To accomplish that purpose the complainants say that

they rely upon: (1) Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 of the

Federal Constitution2; (2) upon the Fifth and Four

teenth Amendments3; (3) the entire Interstate Commerce

Act; (4) upon Section 3(1) of the Interstate Commerce

1 What is involved, however, is not an isolation or seclusion o f Negro

passengers from the general mass of passengers, hut a separation of Negro

and non-negro passengers in different coaches. I f a non-negro passenger

is required to ride in one coach and a Negro passenger is required to ride

in another, which passenger is “ segregated” ! Obviously neither.

Similarly, neither passenger is discriminated against. There simply is

no preference or disadvantage involved.

2 ‘ ‘ The Congress shall have power . . . To regulate Commerce with

foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian

Tribes” .

3 Apparently, though not stated, upon the due process clause o f the

Fifth Amendment, and upon the due process and equal protection clauses

3

Act4 5; (5) upon Section 1(5) of the Interstate Commerce

Act6; and (6) upon Section 2 of the Interstate Com

merce Act.8

The Stipulations.

With one exception7 the stipulations are of a sort;

and taking that of Coast Line as typical and representa

tive, they agree that the case to he decided by the Com

mission is based upon the following ultimate facts and

none other:

Each of the railroads sets aside separate coaches or

portions of coaches in each of its passenger trains for

the exclusive occupancy of Negro passengers and for the

exclusive occupancy of passengers who are not Negroes;

no distinction is made as to or in respect of the assign

ing of Negroes and the assigning of persons of any other

race or color to separate coaches or portions of coaches.

In their design, construction, equipment, appointments,

facilities and other physical characteristics, and in their

maintenance and upkeep, the coaches or portions of

coaches so designated, assigned and set aside for occu-

of the Fourteenth Amendment. As to the Fourteenth Amendment, it is

too plain for citation that it has to do only with action by a State. None

o f the stipulations (except one paragraph o f the stipulation filed by

The Kansas City Southern Railway Company) undertakes to rely on state

law; and Kansas City Southern relies also, as do the other railroads, upon

public opinion, custom and usage.

4 Making it unlawful for an interstate railroad ‘ ‘ to make, give or cause

any undue or unreasonable preference or advantage to any particular

person . . .; or to subject any particular person . . . to any undue or

unreasonable prejudice or disadvantage in any respect whatsoever” .

5 Requiring all charges for services rendered in the transportation

o f passengers to be " ju s t and reasonable” , and prohibiting and declaring

unlawful “ any unjust and unreasoable charge for such service” .

6 Prohibiting and declaring to be unlawful, as unjust discrimination,

any device o f any sort whereby an interstate railroad receives ‘ ‘ from any

person or persons a greater or lesser compensation for any service rendered

. . . in the transportation o f passengers” than is required o f other

persons for whom like and contemporaneous service is furnished.

T The Kansas City Southern relies, as well upon its regulations

respecting segregation, as upon a Louisiana statute.

4

pancy of Negro passengers are substantially equal to

those designated, assigned and set aside for occupancy

by passengers not of the Negro race. Such separation of

the races on the trains is effected pursuant to a rule, regu

lation or practice of each railroad which has existed con

tinuously for more than 50 years8 last past, and pursuant

to the public opinion, customs and usages of the people

of the several states through which the railroads run.8a

The fares charged by the railroads are the same to both

negro and non-negro passengers.

The Issue.

There is no element of discrimination against Negroes

involved in the case; and none can be found unless for

sooth the Commission should agree with the complain

ants that segregation itself is discrimination. The hold

ings of the Commission for the last 67 years, and of the

Supreme Court for the last 58 years, are uniformly to

the contrary, and if segregation now is to be held to be

discrimination, those holdings must be overruled.

The Holdings of the Commission.

The first complaint by a colored man that he was done

a legal wrong, when he was not permitted to ride in a

railroad coach with white people, came before the Com

mission in December, 1887, and was filed three months

after the Interstate Commerce Act became effective Feb

ruary 4,1887. The case was that of Councill v. Western

and Atlantic R. Co., 1 1. C. R. 638. The Commission held,

8 In the case o f The Sante Fe and its named affiliates, 45 years.

8a Southern Railway Company’s Stipulation states that such public

opinion, customs and usages is evidenced “ by the statutes of the said

states which require segregation o f the races” .

5

as correctly reflected by the first headnote, that “ There

is no undue prejudice or unjust preference shown by

railroad companies in separating their white and colored

passengers by providing cars for each, if the cars so pro

vided are equally safe and comfortable” . In the opin

ion (Morrison, Commissioner) it is said, at page 641:

“ Public sentiment, wherever the colored popu

lation is large, sanctions and requires this sepa

ration of races, and this was recognized by coun

sel representing both complainant and defendant

at the hearing. We cannot, therefore, say that

there is any undue prejudice or unjust preferences

in recognizing and acting upon this general senti

ment, provided it is done on fair and equal terms.

This separation may be carried out on railroad

trains without disadvantage to either race and

with increased comfort to both.”

The importance, indeed the crucial importance, of

giving attention and respect to the established and pre

vailing customs and traditions of the people of the sev

eral states, is further illustrated in that portion of the

opinion in Councill’s case which had to do with the cus

tom prevailing in 1887 of providing separate cars for

men and women ;8b and as to which the opinion continues

at page 641:

“ It is both the right and the duty of railroad

companies to make such reasonable regulations as

will secure order and promote the comfort of their

passengers. In the exercise of this right and the

performance of this duty, carriers have established

rules providing separate cars for ladies, and for

gentlemen accompanied by ladies; and their right

to make such rules as to sexes is nowhere ques-

8b Quaere: Who then was ‘ ‘ segregated ” or “ discriminated against ’ ’—

the men or the women?

6

tioned. A man, white or colored, excluded from

the ladies’ car by such a rule could hardly claim

successfully under the Act to Regulate Commerce

that he had been subjected to unjust discrimina

tion and unreasonable prejudice or disadvantage.

It is a custom of the railroad companies in the

States where the defendant’s road is located, and

in all the States where the colored population is

considerable to provide separate cars for the

exclusive use o f colored and of white people” .

Before CouncilVs case was heard, a colored man

named Wm. H. Heard filed a complaint against the

Georgia Railroad alleging discrimination on account of

his color because he, too, had been required to ride in a

coach occupied solely by people of his own race. His

case was decided February 15, 1888, Heard v. Georgia

R. R. Co., 1 I. C. R. 719. Headnote 2, by Commissioner

Cooley, accurately states the holding, and reads:

“ Separation of white and colored passengers

paying the same fare is not unlawful, if cars and

accommodations equal in all respects are fur

nished to both, and the same care and protection

of passengers observed.”

The logic of the holding is emphasized by the follow

ing statements of the opinion found on page 722:

“ The same section applies the same principles

to the transportation of property as to persons,

but no one would seriously insist that the statute

requires all property of the same kind or all kinds

of property to be carried in the same car. I f like

property receives like transportation and at like

rates, the carrier’s duty in that regard is per

formed. The number of cars used for the pur

pose is immaterial.

7

“ Identity, then, in the sense that all must he

admitted to the same ear and that under no cir

cumstances separation can be made, is not indis

pensable to give effect to the statute. Its fair

meaning is complied with when transportation and

accommodations equal in all respects and at like

cost are furnished and the same protection

enforced” .

It was 19 years before the question came again

before the Commission, in 1907 when it decided Georgia

Edwards v. Nashville C & St. L. Ry. Co., 12 I. C. C. 247.

CouncilVs case and Heard’s are referred to, and Heard

is said by the opinion to have held * ‘ that the separation

of white and colored passengers paying the same fare

is not unlawful if cars and accommodations equal in all

respects are furnished to both and the same care and

protection of passengers is observed” . The opinion

adds: ‘ * The principle that must govern is that carriers

must serve equally well all passengers, whether white or

colored, paying the same fare. Failure to do this is

discrimination and subjects the passenger to ‘ undue and

unreasonable prejudice and disadvantage’. ” 9

Joseph P. Evans v. Chesapeake <& Ohio Railway Co.,

92 I. C. C. 713 (1924), presented a complaint that because

Evans, a colored man, had been placed in a colored

coach, an unreasonable fare thereby had been exacted

from him, which, by the same token, was unjustly dis

criminatory and unduly prejudicial; his contention being

thus stated by the opinion:

“ Complainant asks us to find that defendant,

in requiring the segregation of passengers accord

ing to color without complying with the require-

8 The order rendered in that case (p. 250) required the railroads to

cease and desist from failing to furnish a washbowl, towels and separate

smoking compartment for colored passengers “ where the same accom

modations are provided for white passengers paying the same fare” .

8

ments of section 6, has violated the act, and to enter

an order requiring defendant to cease and desist

from offering any other accommodations to

passengers in interstate commerce than those set

forth in its tariffs on file with us” .

Declining to agree with the proposition, the Commission

said:

. . A regulation requiring the segregation

of passengers according to color does not, if equal

accommodations are furnished, change, affect, or

determine any part or the aggregate of the fare

or the value of the service rendered” . . . .

Specific reliance is placed on Chiles v. Chesapeake & Ohio

Ry. Co., 218 U. S. 71 (1910), where, as the Commission’s

opinion states, “ The Court said that the carrier’s regu

lation requiring the segregation in Kentucky of inter

state passengers according to color 4 can not be said to be

unreasonable’. ”

The matter came before the Commission again in

Jackson v. Seaboard Air Line R. Co., 269 I. C. C. 399,

decided October 31, 1947.10 Jackson complained of

inequality of dining car service, which the Commission

found, upon the facts, did exist. Furthermore, however,

as in the complaint here, Jackson alleged a violation of

Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 of the Constitution, and of

Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment. As to that

charge, the Commission said (Division 2, Commissioners

Aitchison, Splawn and Alldredge):

“ . . . That allegation opens up a wide field of

legal questions which the Commission does not

have authority to decide. Most such questions

have been considered by the courts, but it is not

the function of the Commission to attempt to state

the effect of decisions which do not involve provi-

io JacTeson was represented by the same counsel who represent com

plainants here.

9

sions of the act we administer. The Commission’s

attention has not been called to any case in which

it has been held that segregation of the races in

and of itself is unlawful. It will suffice to say that

the Commission has only such jurisdiction as is

specifically conferred on it by statute and that the

Interstate Commerce Act does not prohibit segre

gation or authorize the Commission to do so. The

question whether complainant was subjected to

undue prejudice or unjust discrimination forbidden

by the act is not a question of segregation but is

one of equality of treatment. Mitchell v. United

States, 313 U. S. 80. ” n

We take that statement as a definitive holding that the

Commission will not undertake to examine the complain

ants’ case any further than to see whether the facts

stipulated evidence a violation of the Interstate Com

merce Act. Such an examination will demonstrate that

there is presented here no violation of the Interstate

Commerce Act.

The United States Supreme Court Cases.

Complainants’ case not only undertakes to stand in

the face of those precise and definitive views of the Com

mission directly opposed to complainants’ theory, but

without legal regard to the treatment given contentions

such as theirs by the Supreme Court. The outstanding

n The Commission took the same position in its letters of September

28, 1953, January 27, 1954, March 5, 1954 and March 12, 1954, each

signed by then Chairman J. M. Johnson and by Commissioners Mahaffie

and Freas, to Honorable Chas. A. Wolverton, Chairman, Committee on

Interstate and Foreign Commerce o f the House of Bepresentatives.

Searings before Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce on H. B.

563, 1013, 1350, 3890, 7304, 7324, 8088 and 8160, 83rd Congress, 2nd

Session (1954), pages 6, 7, 8 and 9. Each letter stated that in all

cases o f alleged discrimination on account of segregation in train coaches

“ the Commission has limited itself to the question whether equal accom

modations and facilities are provided for members of the two races, adhering

to the view that the Interstate Commerce Act neither requires nor prohibits

segregation o f the races. Judicial opinion has supported this restricted

conception o f our powers in the premises” .

10

case in that Court is of course Plessy v. Ferguson, 163

U. S. 537 (1896), which held that separate accommoda

tions for the races in interstate commerce is not obnox

ious to the Constitution provided the separate accommo

dations furnished are equal. The precise technical

holding of the case is that a state statute requiring sepa

ration of the races in interstate commerce travel hut

requiring also that each race be furnished with equal

facilities, is not obnoxious to either the Thirteenth or

Fourteenth Amendments or any clause of either.

Almost equally well known is the recent school segre

gation case, Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483,

decided May 17, 1954, which left Plessy v. Ferguson

standing113 but declined to follow it because, the court

said, it involved “ not education but transportation” .

They then proceeded to decide Brown v. Board of Educa

tion on subjective intangibles and modernistic psycho

logical theories and opinions, saying that “ any language

in Plessy v. Ferguson” to the contrary of the Court’s con

clusions as to the modern-day view of separation in the

public schools “ is rejected” .

So far as this Commission is concerned, we would

suppose that if the complaint here brings any question

of federal law at all to the Commission, its solution is

sufficiently stated in Plessy v. Ferguson, particularly, but

not at all solely, because of the way the Supreme Court

handled it in Brown v. Board of Education,12 But for

the convenience of the Commission, and as a matter of

lia The Court was earnestly importuned by the Appellants and Peti

tioners in the school segregation cases to overrule expressly Plessy V.

Ferguson. See, e. g., joint Brief filed November 16, 1953 for Appellants on

reargument in Brown v. Board o f Education, Briggs v. Elliott, Davis v.

County School Board, Nos. 1, 2 and 3, October Term, 1953, p. 37, passim;

and Brief filed in those cases for the United States December 3, 1952, p.

13, passim.

12 In Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629, 636 (1950), the Supreme Court

specifically declined Sweatt’s request that it reexamine Plessy v. Ferguson

“ in the light of contemporary knowledge respecting the purpose of the

11

completeness as it were, we state briefly the other four

cases from the Supreme Court generally thought of

as significant in the consideration of segregation in inter

state transportation: Chiles v. Chesapeake & Ohio Ry.

Co., 218 U. S. 71 (1910); Mitchell v. United States, 313

U. S. 80 (1941); Morgans. Virginia, 328 IT. S. 373 (1946);

and Henderson v. United States, 339 U. S. 816 (1950).

When the Chiles case was decided, the Congress then,

as now, had enacted no statute requiring, recognizing or

relating to segregation of passengers in interstate com

merce. The Court held that congressional inaction in

that respect is equivalent to a declaration that a rail

road may by its regulations separate white and Negro

interstate passengers. Plessy v. Ferguson of course is

cited, and approved (as well as Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U. S.

485 (1878)); and, pointing out that in Plessy v. Ferguson

a statute of Louisiana was involved, while in Chiles v.

C <& 0 the regulation of the railroad was at stake, the

Court said (p. 77) that “ Regulations which are induced

by the general sentiment of the community for whom

they are made and upon whom they operate cannot be

said to be unreasonable” . No question of inequality of

accommodations was involved in Chiles’ case. He

simply stood upon the ground he took, as “ an interstate

passenger who knew his rights” , that “ the separate

coach law” did not apply to him. The opinion decides

Fourteenth Amendment and the effects of racial segregation” . And

the Court o f Appeals for the 4th Circuit (Boyer v. Garrett (1950), 183

F. 2d 582) refused “ to disregard a decision o f the Supreme Court

fPlessy v. Ferguson] which that Court has not seen fit to overrule and

which it expressly refrained from examining, although urged to do so

in the very recent case of Sweatt v. Painter, 70 S. Ct. 848” .

The United States District Court for the District o f Maryland on July

27, 1954, in Lonesome v. Maxwell, Civil No. 5965, and the similar cases of

Dawson v. Baltimore, Civil No. 5847 and Isaacs v. Baltimore, Civil No.

6879, examined Plessy v. Ferguson in the light o f Brown v. Board of

Education and held that separation o f the races at city-owned and

managed public bath houses with equal facilities for each race is con

stitutionally unobjectionable. Brown v. Board o f Education, the opinion

says, did not "destroy the whole pattern of segregation” .

12

what Chiles’ rights were as an interstate passenger.

This is made explicit when Justice McKenna quotes from

the decision in Hall v. DeCuir, supra, and says:

“ This language is pertinent to the case at bar,

and demonstrates that the contention of the plain

tiff in error is untenable. In other words, demon

strates that the interstate commerce clause of the

Constitution does not constrain the action of car

riers, but, on the contrary, leaves them to adopt

rules and regulations for the government of their

business, free from any interference except by

Congress. Such rules and regulations, of course,

must be reasonable, but whether they be such can

not depend upon a passenger being state or inter

state.”

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 80 (1941), was the

case in which Mitchell, a Negro Congressman, was denied

a seat in a Pullman when seats for white passengers

were available, and he was transferred from a Pullman

which he had occupied for part of his journey to a coach

whose accommodations and facilities were inferior to

those in the Pullman from which he was removed. The

issue, as stated by the Court, arose out of the fact that

he was required to ride “ in a second class car and was

thus denied the standard conveniences and privileges

afforded to first class passengers” . That, the Court of

course said, was “ manifestly a discrimination against

him . . . based solely upon the fact that he was a Negro”

and the question to be determined, the Court continued,

was whether such treatment “ was a discrimination for

bidden by the Interstate Commerce A ct” ; and that ques

tion, the Court went on to say, was “ not a question of

segregation but one of equality of treatment” . Conse

quently, the Court’s finding in favor of Mitchell was

13

“ that, the discrimination shown was palpably unjust and

forbidden by the Act” .13

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 (1946), was the

consequence of Morgan’s being forced, in obedience to a

Virginia statute, to move from bis seat in a portion of an

interstate bus designed only for the seating of white pas

sengers to a portion of the bus assigned solely for the

use of Negroes. The case was decided on the ground

that such treatment was repugnant to Clause 3, Section

8, Article I of the Federal Constitution as a burden on

interstate commerce.

Henderson v. United States, 339 U. S. 816 (1950), held

that Henderson, a colored man, could not be denied a seat

and service in a dining car when there were seats in the

car vacant and not in use. The Court finds that “ from

the beginning” the Commission bad recognized the

requirements of the Commerce Clause as applying “ to

discriminations between white and Negro passengers” ;

they said that the decision was largely controlled by

that in Mitchell*s case; that Henderson had been denied

a seat in the dining car “ although at least one seat was

vacant and would have been available to him, under the

existing rules, if he had been white” ; and that he had

“ a right to be free from unreasonable discriminations

. . . under Section 3 (1 )” .

is Complainants ’ counsel. Carter, testified before the Committee o f the

House on Interstate and Foreign Commerce in support o f H. E. 563,

et al. (ante, p. 9, footnote 11), and at page 99 o f the transcript o f the

Hearings before that Committee he is quoted as saying that M itchell’s

case “ was unquestionably merely an application of the ‘ separate but

equal’ doctrine and in no way restricted the carrier’s right to effect

racial segregation as long as Negro passengers were provided equal

accommodations” . As to Henderson v. United States, 339 U. S. 816,

he said, at page 99, that its decision “ did not in terms segregate per s e ” .

14

Conclusion.

Those who speak with the highest authority on the

subject matter of the complaint, namely, this Commis

sion and the Supreme Court, have written long, clearly

and definitely on the subject, not merely by ipse dixit,

but with careful explanation of the reasoning by which

their results were reached. So, for example, in the Com

mission’s opinion in Heard v. Georgia R. R. Co., 1 1. C. R.

719, it is said:

“ The undeniable fact of a difference in color is

one for which government and law are not respon

sible. It exists by a fiat transcending human

knowledge, and has existed through the epochs of

history. It should he recognized and dealt with

like other unchangeable facts, justly always, but

with discretion and reason. When it becomes an

element in a judicial controversy one color or race

has no exclusive right to recognition nor ground

for special favor over the other, hut white and black

alike are entitled to fair and impartial considera

tion; and the principle of equality of rights is to

be applied with even handed justice, but without

unnecessary extension beyond its legitimate pur

view. It is not, therefore, with sole regard to the

wishes or conceptions of ideal justice of colored

persons, nor only with deference to the prejudices

or abstract convictions of white persons, that a

practical adjustment is to be reached, hut with

enlightened regard to the best interests and har

monious relations of both, constrained by long

past events for which none now living are respon

sible to make their habitations and support them

selves as best they can under the same govern

ment.

“ The disposition of a delicate and important

question of this character, weighted with embar

rassments arising from antecedent legal and social

15

conditions, should aim at a result most likely to

conduce to peace and order, and to preserve the

self respect and dignity of citizenship of a common

country. And, -while the mandate of the statute

must be our paramount guide, we may be assisted

by the knowledge familiar to all of past and pres

ent circumstances relating to our diverse popula

tion, and such lights of reason and experience as

surround the question, in giving effect with the

least amount of friction to the purposes of the

law. ’ ’

Similarly, Mr. Justice Brown, wrote for the Court in

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, at page 551:

“ We consider the underlying fallacy of the

plaintiff’s argument to consist in the assumption

that the enforced separation of the two races

stamps the colored race with a badge of inferior

ity. I f this be so, it is not by reason of anything

found in the act, but solely because the colored

race chooses to put that construction upon it. The

argument necessarily assumes that if, as has been

more than once the case, and is not unlikely to he

so again, the colored race should become the domi

nant power in the state legislature, and should

enact a law in precisely similar terms, it would

thereby relegate the white race to an inferior posi

tion. We imagine that the white race, at least,

would not acquiesce in this assumption. The argu

ment also assumes that social prejudices may be

overcome by legislation, and that equal rights can

not be secured to the negro except by an enforced

commingling of the two races. We cannot accept

this proposition. I f the two races are to meet on

terms of social equality, it must be the result of

natural affinities, a mutual appreciation of each

other’s merits and a voluntary consent of individ

uals. As was said by the court of appeals of New

York in People v. Gallagher, 93 N. Y. 438, 448 [45

16

Am. Rep. 232], ‘ this end can neither be accom

plished nor promoted by laws which conflict with

the general sentiment of the community upon whom

they are designed to operate. When the govern

ment, therefore, has secured to each of its citizens

equal rights before the law and equal opportuni

ties for improvement and progress, it has accom

plished the end for which it is organized and

performed all of the functions respecting social

advantages with which it is endowed.’ Legisla

tion is powerless to eradicate racial instincts or

to abolish distinctions based upon physical differ

ences, and the attempt to do so can only result in

accentuating the difficulties of the present situa

tion. I f the civil and political rights of both races

be equal, one cannot be inferior to the other

civilly or politically. I f one race be inferior to the

other socially, the Constitution of the United

States cannot put them upon the same plane” .

The decisions of the Supreme Court, and those of

this Commission, are perfectly clear that the mere

separation of white and colored passengers, when equal

accommodations are provided, is not a violation of the

Interstate Commerce Act nor is it otherwise unlawful.

Nor are the doctrines of those decisions put aside by

the Supreme Court’s discussion in Brown v. Board of

Education. There is no way of relating the status and

condition of a passenger on a railroad train to that of

a child going to school. Riding on a train is not, as

education is, “ perhaps the most important function of

state and local governments” 14. Passenger transpor

tation is not required “ in the performance of our most

basic public responsibilities” , nor can it with any degree

of verity be said to be “ the very foundation of good

14 All the quotations in this paragraph are found in the opinion in

Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 IT. S. 483 (1954).

17

citizenship” , or “ a principal instrument in awakening

the child [or man, or woman] to cultural values, in

preparing him for later professional training, and in

helping him to adjust normally to his environment” .

There is involved in passenger transportation none of

“ those qualities which are incapable of objective

measurement but which make for greatness” . There

is no basis for a conception that the separation on

passenger trains of colored and non-colored passengers

generates in the former “ a feeling of inferiority as to

their status in the community that may affect their

hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to he undone” .

The sociological surveys and psychological studies on

which is based the Supreme Court’s opinion in Brown

v. Board of Education, and which that Court itself

refused to apply to Plessy v. Ferguson, do not suggest

that this Commission should make such an application,

nor that Heard v. Georgia R. R. Co., 1 1. C. R. 719 (1888)

should be repudiated, nor that Plessy v. Ferguson should

not be followed.

Request for Findings.

The Railroads who file this brief severally request

that the following findings be made:

1. That the segregation of the races upon interstate

passenger trains operated by the several and respective

railroads named herein accord to each race without dis

tinction substantial equality in accommodations, service

and treatment;

2. That such segregation is not contrary to any pro

vision of the Interstate Commerce Act;

3. That the rules, regulations and practices of the

several railroads, pursuant to which such segregation is

18

effected, are not unduly prejudicial to or unduly dis

criminatory against any of the complainants; and

4. That the complaint should be dismissed.

Respectfully submitted,

Charles Cook H owell,

J ohn W . W eldon,

Attorneys for Atlantic Coast Line

Railroad Company.

R oland J. L ehman,

Stare Thomas,

Attorneys for The Atchison, Topeka

& Santa Fe Railway Company;

Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Rail

way Company, and Panhandle &

Santa Fe Railway Company.

Charles F. T urner,

Attorney for Gulf, Mobile and Ohio

Railroad Company.

Jos. R. Brown,

W m. E. Davis,

Attorneys for The Kansas City

Southern Railway Company.

Prime F. Osborn, IH,

Attorney for Louisville & Nashville

Railroad Company.

A. J. Bauman,

Attorney for St. Louis-San Fran

cisco Railway Company.

Sidney S. A lderman,

A rthur J. Dixon,

Attorneys for Southern Railway

Company.

19

Certificate of Service.

I hereby certify that this day I have served this

Brief upon all parties of record in this proceeding, by

mailing a copy thereof, properly addressed, to counsel

for each of said parties.

Dated at Wilmington, North Carolina this 14th day

of October, 1954.

Charles Cook H owell,

Counsel for Atlantic Coast Line

Railroad Company.

(W«5)