Cager et al Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

February 5, 1968

23 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Cager et al Brief Amici Curiae, 1968. 8bc51343-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/52719584-3e4b-4507-84fc-f2b381c1c337/cager-et-al-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

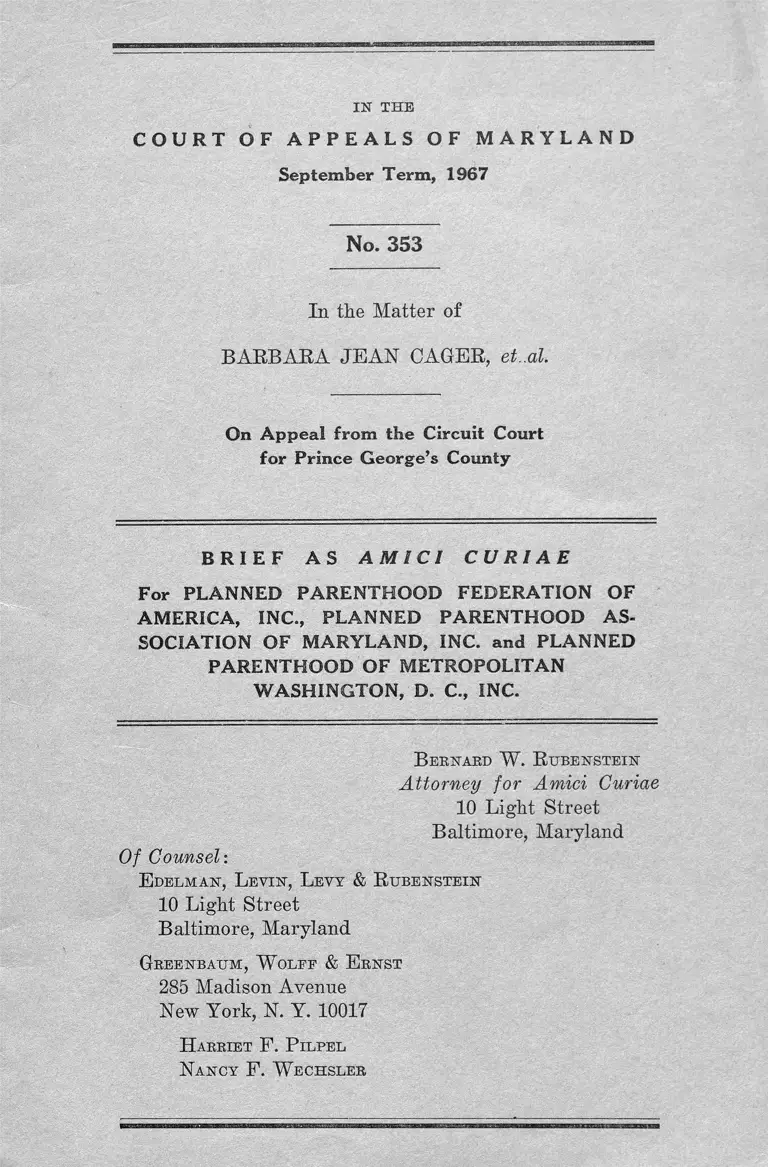

IN THE

C O U R T O F A P P E A L S O F M A R Y L A N D

September Term, 1967

No. 353

In the Matter of

BARBARA JEAN CAGER, et.a l

On Appeal from the Circuit Court

for Prince George’s County

B R I E F A S A M I C I C U R I A E

For PLANNED PARENTHOOD FEDERATION OF

AMERICA, INC., PLANNED PARENTHOOD AS

SOCIATION OF MARYLAND, INC. and PLANNED

PARENTHOOD OF METROPOLITAN

WASHINGTON, D. C., INC.

B ernard W . R ubenstein

Attorney for Amici Curiae

10 Light Street

Baltimore, Maryland

Of Counsel-.

E delman, L evin, Levy & R ubenstein

10 Light Street

Baltimore, Maryland

Greenbaum, W olee & E rnst

285 Madison Avenue

New York, N. Y. 10017

H arriet F. P ilpel

Nancy F. W echsler

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S

PAGE

Statement op Inteeest op Amici C uriae ..................... 1

Statement op Facts ........................................................ 5

Argument .......................................................................... 7

I—The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States forbids state compulsion to use

birth, control .................................................................. 9

A. The Bight of Privacy ........................................ 9

B. Substantive Due Process .................................. 14

C. Equal Protection ................................................ 16

Conclusion ........................................................................ 18

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Bantam Books v. Sullivan, 372 U. S. 5 8 ........................ 8

Boyd v. United States, 116 U. S. 616 ............................ 10

Consumers Union v. Walker, 145 F. 2d 33 (D.C. Cir.

1944) ............................................................................ 8

Gault, Matter of, 387 U. S. 1 .......................................... 17

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U. S. 479 ...........8, 9,10,11,12,

13,14,15

Harper v. Virginia, 393 U. S. 663 .................................. 17

Lombard v. Louisiana, 372 U. S. 267 ............................ 8

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U. S'. 1 ...................................... 17

PAGE

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 IT. S. 184 .......................... 17

Parrish v. Civil Service Commission of the County of

Alameda, 57 Cal. Rptr. 623, 425 P. 2d 223 (1967) 12

People v. Dominguez, 64 Cal. Rptr. 290 (1967) 13,14

Poe v. Ullman, 367 U. S. 497 ...................................... 8,11,15

Rochin v. California, 342 U. S. 165 ................................ 11

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ...................................... 8

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 IT. S. 535 .............................. 17

State v. Baird, 50 X. J. 376 (1967) ................................ 8

Other Authorities:

Constitution of the United States:

Fourth Amendment .................................................. 9

Fifth Amendment...................................................... 9

Ninth Amendment .................................................... 9

Fourteenth Amendment ...................................... 9,16,17

Social Security Act:

Title II of Public Law 90-248, January 2, 1968

Section 201(a) (1) .............................................. 15

Section 402(a) .................................................... 16

Title III of Public Law 90-248 .............................. 16

Title Y of Public Law 90-248 ................................ 16

United States Internal Revenue Code of 1954:

§501(c)(3 ) .................................................................. 3

Washington Post, June 4, 1967 ............ 5

Washington Star:

June 2, 1967 ................................................................ 5

July 19, 1967 .............................................................. 7

September 24, 1967 ................................................ 6

1ST T H E

C O U R T O F A P P E A L S O F M A R Y L A N D

S eptem ber T erm , 1967

No. 353

In the Matter of

B arbara Jean Gager, et al.

On A p p e a l from the C ircuit Court

fo r P rin ce G eorg e ’ s County

B R I E F A S A M I C I C U R I A E

For PLA N N E D P A R E N T H O O D FE D E R A TIO N OF

A M E R IC A , INC., PLA N N E D P A R E N T H O O D A S

SO C IA TIO N O F M A R Y L A N D , INC. and PLA N N ED

P A R E N T H O O D O F M E T R O P O L IT A N

W A S H IN G T O N , D. C., INC.

Statement of Interest of Amici Curiae

This brief is submitted by P lanned P arenthood F edera

tion oe A merica, Inc., P lanned P arenthoood A ssociation

oe Maryland, Inc. and P lanned P arenthood of Metropoli

tan W ashington, D. C., I nc., pursuant to leave granted by

Chief Judge Hammond in an order dated February 5, 1968.

2

Amici are respectively the national health agency in the

field of birth control (Planned Parenthood Federation of

America, Inc., also known as Planned Parenthood-World

Population) and two affiliates of Planned Parenthood Fed

eration of America, Inc, whose activities relate to the geo

graphical area out of which these proceedings arise

(Planned Parenthood Association of Maryland, Inc. and

Planned Parenthood of Metropolitan Washington, D.O.,

Inc.).

Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Inc. (here

inafter Planned Parenthood) is a New York non-profit

membership corporation. It is the central coordinating

organization of the private effort to bring to the American

people the best available services for and information about

family planning and fertility control, and to support and

stimulate research on human reproduction and on improved

techniques of birth control. The membership of Planned

Parenthood consists of 154 state and local affiliates, which

operate 400 centers throughout the nation. Planned Parent

hood Association of Maryland, Inc. and Planned Parent

hood of Metropolitan Washington, D.C., Inc. are duly con

stituted affiliates of Planned Parenthood.

Planned Parenthood is an active member of the Inter

national Planned Parenthood Federation which links na

tional organizations for medical research and services in

birth control in 50 countries and cooperates with the United

States and other governments, and which is an accredited

non-governmental agency to the United Nations Economic

and Social Council. Planned Parenthood and most of its

3

affiliates have tax exemption under §501 (c)(3 ) of the

United States Internal Revenue Code of 1954.

Through Planned Parenthood’s Medical and Social Sci

ence Committees its affiliates receive guidance in the areas

of medically directed child spacing, treatment of infertility

problems and education for marriage and parenthood.

Each of the affiliates functions under strict medical stand

ards promulgated by a National Medical Committee, in

conjunction with local medical advisory committees, all

such committees consisting of physicians.

By means of its various committees, Planned Parent

hood operates as a clearing house for information and ser

vices relating to birth control. It formulates nation-wide

medical and clinical standards and acts as an agency for

public and professional education in this field. Its medical

director and other consultants confer with medical school

faculties and local committees in relation to teaching tech

niques, formation of clinics and the like.

Planned Parenthood works with medical, social work,

religious and professional organizations throughout the

country. It is a member of the National Health Council

and the American Public Welfare Association. It is affili

ated with the National Conference on Social Welfare and

is listed as an ‘ ‘ agency of medical interest” in the Amer

ican Medical Association’s Directory of National Voluntary

Health Organizations.

Planned Parenthood encourages and stimulates research

by scientists in leading universities and laboratories and

guides and assists in the clinical testing of contraceptive

4

methods. It organizes conferences for experts in the natu

ral and social sciences and it collates information and re

search and fosters publication of articles in scientific

journals.

Many of Planned Parenthood’s affiliates operate in co

operation with local public health and public welfare agen

cies. Many affiliates are also teaching centers for physi

cians, nurses and social workers and provide referral ser

vices for patients with suspected pathological conditions

to qualified medical specialists for treatment. Many of

Planned Parenthood’s affiliates receive funds from state or

federal agencies under established government programs

— such as the Office of Economic Opportunity program to

combat poverty in the United States.

Planned Parenthood Association of Maryland, Inc.

conducts centers in the City of Baltimore which offer birth

control services and also fertility services for couples who

have been unable to have children. It also conducts a state

wide educational program and a professional training pro

gram for physicians, nurses, mid-wives, social workers and

administrators in the field of family planning and public

health.

Planned Parenthood of Metropolitan Washington, D.C.,

Inc. conducts similar centers in a number of places in the

District of Columbia and in Montgomery County, Mary

land; it also conducts an extensive educational program

in conjunction with public health facilities maintained in

the District of Columbia and Montgomery County.

5

Amici’s programs and activities are designed to make

it possible for all Americans to obtain or to reject birth

control as a matter of personal choice. Amici believe that

a judicial order requiring women to practice birth control

is an unjustified invasion of the constitutionally protected

area of privacy.

Statement of Facts

The situation here involved presents the following

basic facts: Three young women have borne illegitimate

children. The children all reside with their mothers (or

with persons chosen by their mothers). The mothers sought

public assistance, the illegitimacy of the children was dis

closed, the mothers were arrested and child neglect proceed

ings were instituted.

Following the arrest of the mothers the Welfare Depart

ment of Prince George’s County on June 1, 1967 announced

that it would refer such mothers to one of two public health

clinics then offering birth control services, and the County

Prosecutor announced that he would refrain in the future

from arresting women who could show that they had done

so (Washington Star, June 2, 1967; Washington Post,

June 4, 1967). Subsequently, the State Department of

Public Welfare and the Prince George’s County Welfare

Board advised the President of Planned Parenthood, Dr.

Alan F. Guttmacher, that neither agency’s policy permitted

compelling unwed mothers to attend birth control clinics

as a prerequisite for public assistance (Letter of Ealeigh

C. Hobson, Director, State Department of Public Welfare,

dated June 9, 1967; letter of Y. A. Hampton, Director,

6

Prince George’s County Welfare Board, dated June 12,

1967). Thereafter the neglect proceedings against the

children here involved continued. After a hearing at which

the Court below made a finding of neglect, the Court stated

(Tr. at p. 116) that it would reserve decision on whether

to direct an investigation and report by the Department

of Juvenile Services, and further stated the following (Tr.

114, 115):

“ . , . I think you are entitled to know what the

Court’s thinking is in this matter so you can govern

yourselves accordingly.

“ I believe that some headway can be made in these

cases against the third illegitimate child, because if

this case had come before the Court with two, and it

is now here some of these people have three, but I

would require them to conduct themselves in certain

ways in their homes. I would require them to study

and understand methods of birth control and to prac

tice them at the risk of losing their children if they do

not.”

The Trial Court further stated that it was prepared to

supply “ some incentive to employ modern methods of

family control” through the Court and the Department of

Juvenile Services (Tr. 115, 116).

It is apparent that at the time of the trial of these mat

ters, voluntary birth control services had not been made

readily available by the County or the State to these

women or others like them. Such facilities were “ in

adequate to meet the problem” according to the statement

of the Chairman of the Prince George’s County Commis

sioners (Washington Star, September 24, 1967). There

7

were three public birth control clinics—each of which was

open only once a week, for a total of 9 to 12% hours per

week for all clinics (ibid.; Washington Star, July 19,

1967).

Argument

Planned Parenthood Federation of America and its

Maryland and Washington, D.C. affiliates (hereinafter

referred to generally as “ Planned Parenthood” ) appear

here amici curiae because they believe that these matters

present an important issue of individual rights directly af

fecting Planned Parenthood’s activities and objectives—the

issue of compulsory birth control.

This brief does not deal with other grounds for holding

the action of the Trial Court in these proceedings invalid.

The finding of “ child neglect” upon which the Trial

Court’s order is based is itself subject to challenge on

both statutory and constitutional grounds; it is our under

standing that these challenges are raised by the parties

and others.

Planned Parenthood advocates and strives for the

widest possible dissemination of birth control information

and service to all who need and want it; it endeavors,

through its medically supervised centers and in other ways

to serve the community in this respect, Since the need

for such services is greater than the ability of private

agencies, such as Planned Parenthood, to meet it, Planned

Parenthood also advocates and supports programs by

local, state and federal governments to finance and provide

birth control services to those who do not otherwise have

access to them.

Planned Parenthood has at the same time consistently

opposed governmental edicts or restrictions which interfere

with freedom of access to birth control information or ser

vices, or freedom to use or not to nse birth control mate

rials. Poe v. Ullman, 367 IT. S. 497; Griswold v. Connect

icut, 381 IT. S. 479; Consumers Union v. Walker, 145 F. 2d

33 (D.C. Cir. 1944); State v. Baird, 50 N.J. 376 (1967).

In the matters now before this Court, Maryland author

ities and specifically the Trial Court, have asserted author

ity to require the use of birth control. The Trial Court has

threatened to enforce such asserted authority by removing

children from the custody of mothers who fail to practice

birth control if ordered to do so by the Court. Further

more, the authority of the county prosecutor, as well as that

of other local officials, has been invoked to attempt to en

force a system of compulsory birth control for welfare

recipients exclusively. Thus, in addition to the specific

threat of the Trial Court which is of record here, the situa

tion is also affected by the assertion of similar power by

other agencies—agencies which can have immense impact

on the lives of indigent citizens of the State of Maryland.

Cf. Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 IT. S. 267; Bantam Books v.

Sullivan, 372 IT. S. 58; Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 IT. S. 1.

In the instant proceedings, the judicial branch, acting

without any specific legislative authority, has threatened

to penalize the mothers here concerned if they fail to prac

tice birth control. We believe that these threats directly

impinge upon the protected area of privacy recently de

lineated by the United States Supreme Court in Griswold

v. Connecticut, supra.

9

Moreover, while the plight of the mothers is plain,

the social problem symbolized by the situation is real and

non-coercive remedies are desirable and feasible, yet, the

State of Maryland does not make adequate birth control

services available and private agencies such as Planned

Parenthood have not had the resources or facilities to

meet the need. It is in this context that the Trial Court

has threatened these mothers.

Planned Parenthood urges that resolution of the social

problems involved in the manner threatened here violates

fundamental constitutional rights of the women concerned

in these proceedings.

I. The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States forbids state compulsion to

use birth control.

We submit that, in the circumstances of these cases, to

compel these women “ to practice birth control’ ’ would in

fringe their rights under the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States.

A . T h e R ight o f P rivacy

We believe that the question of compulsion to practice

birth control must be evaluated in light of the constitutional

right of privacy enunciated in Griswold v. Connecticut,

supra. In that case, live of the justices derived this consti

tutional right from the fact that a number of specific provi

sions of the Bill of Rights, including the due process clause

of the Fifth Amendment, the Fourth Amendment and the

reservation of rights clause of the Ninth Amendment “ have

10

penumbras, formed by emanation from those guarantees

that help give them life and substance” , concluding that

these “ various guarantees create zones of privacy” (at

page 484), from which a constitutional right of privacy

must be acknowledged. Two of the justices rested their

concurrences on their understanding of the scope of per

sonal “ liberty” as a constitutional concept, and thus found

a right of privacy in the due process clause as such.

We believe that whatever specific provision or provi

sions of the Bill of Bights may be thought to have dom

inated in Griswold, the fundamental considerations which

led to the result in Griswold require a comparable result

here.

Griswold was a case involving the claim of the State of

Connecticut that it could validly forbid the use' of contra

ceptives. We submit that the reasoning of Griswold (and

of related cases touching on rights of personal privacy)

must apply also to prohibit compulsory use of contracep

tives.

In each situation the fundamental invasion of privacy

relates to the intrusion by the state into personal intimacies

which should be beyond such intrusion in a country where

human dignity and “ the privacies of life” (Boyd v. United

States, 116 U. S. 616, 630) are held supreme. We believe

that the marital status of the persons involved cannot be

determinative in resolving the basic problems of personal

privacy necessarily presented both here and in Griswold.

Surely the intrusion on protected privacy here presented

respects matters of personal intimacy and is shocking to

1 1

the conscience of a civilized society. (Bochin v. California,

342 U. S. 165; Poe v. Uliman, supra; Griswold v. Connecti

cut, supra.)

In Poe v. Uliman, supra, in a dissenting opinion pro

phetic of the result in Griswold (and involving the same

Connecticut use statute), Mr. Justice Harlan pointed out

what would be involved in enforcement of a law forbidding-

use of birth control drugs or devices:

“ • ■ • this could allow the deployment of all the

incidental machinery of the criminal law, arrests,

searches and seizures; inevitably it must mean at the

very least the lodging of criminal charges, a public

trial, and testimony as to the corpus delicti. Nor

would any imaginable elaboration of presumptions,

testimonial privileges, or other safeguards, alleviate

the necessity for testimony as to the mode and manner

of the married couple’s sexual relations, or at least

the opportunity for the accused to make denial of the

charges.” (at page 548)

-M-i’- Justice Douglas, both in his dissenting opinion in

Poe and in his opinion for the Court in Griswold, found

the same basic flaw in the law. Thus, in Poe, Mr. Justice

Douglas said:

“ I f we imagine a regime of full enforcement of

the law in the manner of an Anthony Comstock, we

would reach the point where search warrants issued

and officers appeared in bedrooms to find out what

went on.” (at pages 519, 520)

Obviously, these objections to a statute prohibiting use of

conti aceptives, are equally applicable—probably more so—

to a court order requiring use of contraceptives. In the

12

opinion for the Court in Griswold, Mr. Justice Douglas

asked :

“ Would we allow the police to search the sacred

precincts of marital bedrooms for telltale signs of the

use of contraceptives!” (at pages 485, 486)

and answered:

“ The very idea is repulsive to the notions o f pri

vacy surrounding the marriage relationship.” (at

page 486)

We submit that the very idea—either in enforcing prohibi

tion against use, or in a requirement of use—is repulsive to

the notions of privacy surrounding sex relationships,

whether in or outside of marriage in a society which re

spects human dignity. Moreover, the confidential relation

ship between physician and patient would undoubtedly be

affected.

In our society today, the home is not the traditional

one of simpler times; as between many men and women

to-day, sexual relations are not exclusively and conven

tionally limited to the legal confines of matrimony. This

is true in all strata of society. It would be unthinkable

to conclude that the absence of adherence to traditional

social forms renders individual citizens vulnerable to inva

sion of personal privacy to which those who are married

may not constitutionally be subjected.*

* In this connection it should be noted that the invasion of privacy

which is in question here goes far beyond what would be involved if

laws against fornication and adultery were actually enforced— which,

of course, is not the case (perhaps in considerable part because of

community repugnance to even that degree of systematic intrusion

on personal relationships). Cf. Parrish v. Civil Service Commission

of the County of Alameda, 57 Cal. Rptr. 623, 425 P. 2d 223 (1967),

where the Supreme Court of California held unconstitutional early

morning raids (called “ Operation Bedcheck” ) on homes of welfare

13

There should he no doubt about the impact of state com

pulsion relative to the use of contraceptives—as Justice

Douglas pointed out in Poe v. Uttman:

“ I f it (the state) can make this law, it can enforce

it. And proof of its violation necessarily involves

an inquiry into the relations between man and wife.”

(at p. 521)

How would the state enforce a law requiring the use of

contraceptives? Surely not without, at the very least, an

inquiry into the intimate details of the physician-patient

relationship and subsequently of the patient’s sexual activ

ities. Will the law seek to establish whether a woman uses

a particular method of contraception; whether a male con

traceptive is used; whether, for example, if the woman is

using an intrauterine device she has taken the necessary

precautions to ensure its continued effectiveness? Ob

viously no such inquiry should be permitted. Equally ob

viously the fact of pregnancy would not make it possible

to short cut such inquiries—no contraceptive method has

yet achieved 100% effectiveness—either because of itself

or because of errors in its use or failure to use it.*

recipients designed to detect the presence or absence of “ unauthorized

males’ ' ; where state employees were directed to “ conduct a thorough

search of the entire dwelling, giving particular attention to beds,

closets, bathrooms and other possible places of concealment” . Such

searches, the California court said, posed constitutional questions

“ relating both to the Fourth Amendment’s stricture against unrea

sonable searches and to the penumbra right of privacy and repose

recently indicated by the United States Supreme Court in Griswold

v. State of Connecticut.”

*C f. People v. Dominguez, 64 Cal. Rptr. 290 (1967), where it

was made a condition of probation that the defendant have no further

illegitimate children. The defendant claimed that “ . . . she started

having intercourse but used birth control. For some reason the birth

control medication was not effective.” The court revoked probation;

the Appellate Court reversed, saying “ Contraceptive failure is not an

indication of criminality” (at page 293).

14

Thus we think it is plain that to compel use is in a

constitutional sense, so far as the right of privacy is con

cerned, no different from forbidding use and is barred by

Griswold v. Connecticut. Like the law forbidding use, en

forced use would “ attain its goals by means having a

maximum destructive impact” upon the right of privacy

( Griswold v. Connecticut, supra, at page 515).

B. Substantive Due Process

Furthermore, there are other aspects of the situation

here presented which implicate fundamental liberty within

the meaning of due process. Quite aside from the privacy

problem involved, it is patently arbitrary and capricious

for the state to order an indigent woman to practice birth

control when the state fails to make it possible for indigent

women to obtain medical birth control service. Thus, the

state is saying to the mothers here, and others who seek

public assistance, that it will separate them from their

children unless they practice birth control, when it is per

fectly clear that the women will not be able to comply,

since the services needed for such compliance are not there.

This is like arresting a man for being without visible means

of support in a period of mass unemployment. We submit

that any such state action is arbitrary and capricious and

would deprive these mothers of liberty without due process.

In People v. Dominguez, 64 Cal. Bptr. 290 (1967) the

Supreme Court of California held invalid a condition of

probation that the defendant should have no further illegiti

mate children. The California court said (at page 294):

15

“ The motive (of the condition of probation) was to

prevent the appellant from producing offspring who

might become public charges . . . a grave problem, but a

court cannot use its awesome power in imposing condi

tions of probation to vindicate the public interest in

reducing the welfare rolls by applying unreasonable

conditions of probation.”

In Poe (at page 542), Mr. Justice Harlan pointed out

that:

‘ ‘ Due process has not been reduced to any formula;

its content cannot be determined by reference to any

code . . . it has represented the balance which our nation

built upon postulates of respect for the liberty of the

individual, has struct between that liberty and the

demands of organized society.”

In Griswold, Justice Goldberg wrote a concurring opin

ion, joined in by the Chief Justice and Justice Brennan, in

which he enumerated the following principle of due process

in relation to birth control (at page 497):

“ . . . if, upon a showing of a slender basis of ra

tionality a law outlawing voluntary birth control by

married persons is valid, then, by the same reasoning,

a law requiring compulsory birth control also would

seem to be valid. In my view, however, both types of

laws would unjustifiably intrude upon rights of marital

privacy which are constitutionally protected.”

In this connection, we should bring to this Court’s at

tention that recent federal legislation providing for exten

sion of publicly supported birth control services embodies

a clear policy against compulsion in this field. Thus, while

the recent amendments to Section 201(a)(1) and Section

16

402(a) of the Social Security Act (Title II of Public Law

90-248, January 2,1968) provide that welfare agencies must

offer “ in all appropriate cases family planning service” to

recipients of aid to Families with Dependent Children, they

also explicitly require that “ the acceptance . . . of family

planning services . . . shall he voluntary, and shall not be

a prerequisite to eligibility for or the receipt of any other

service or aid.” *

C. Equal Protection

Moreover, grave question of denial of equal protection

of the law under the Fourteenth Amendment is presented

where the state singles out for mandatory birth control

women on public assistance who have had illegitimate chil

dren. We do not address ourselves as amici to the equal

protection issues raised as to the children and the mothers

by the “ neglect” finding, points which we understand will

be briefed by the parties. Our special concern as amici is to

note that the result of an order such as that threatened

by the Trial Court would be to create an arbitrary and in

vidious classification of women who need public assistance,

as distinguished from other women who might bear illegiti

mate children. As to these indigent women only, the state

seeks to intrude into matters which, as we have discussed,

are within the constitutionally protected area of personal

privacy. Only the poor, in other words, are to be subjected

* See also Title III of Public Law 90-248 which provides that

state plans for maternal and child health under Title V of the Social

Security Act must provide “ that acceptance of family planning serv

ices . . . shall be voluntary on the part of the individual to whom

such services are offered and shall not be a prerequisite to eligibility

for or the receipt of any service under the plan.”

17

to state control over how they manage their sexual rela

tions. Cf. Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535, 541:

“ When the law lays an unequal hand on those who

have committed intrinsically the same quality of of

fense and sterilizes one and not the other, it has made

as an invidious a discrimination as if it had selected a

particular race or nationality for oppressive treat

ment.”

See also Loving v. Virginia, 388 IT. S. 1; Harper v.

Virginia, 383 U.S. 663; McLaughlin v. Florida,

379 U.S. 184.

In Matter of Gault, 387 U. S. 1, Mr. Justice Fortas, writ

ing for the Court in setting forth basic rights of juvenile

offenders, said “ . . . neither the Fourteenth Amendment

nor the Bill of Bights is for adults alone” (at page 13).

That principle applies with equal force to the people here

involved—the constitutional rights of privacy and freedom

from arbitrary action are not for the affluent alone. Surely

state officials cannot single out for compulsion only those in

our society whose economic circumstances require them to

seek public assistance.

18

Conclusion

Nothing herein stated is intended to suggest that

Planned Parenthood objects to state efforts to make birth

control information and service available to all on a volun

tary basis— on the contrary, Planned Parenthood believes

that extension of voluntary birth control service is wholly

lawful and is of the utmost social importance. We are

obliged, however, to object to state compulsion to practice

birth control and to request this Court to make clear that

such compulsion violates basic personal rights guaranteed

by the Constitution of the United States.

Respectfully submitted,

B ernard W. R ubenstein

Attorney for Amici Curiae

10 Light Street

Baltimore, Maryland

Of Counsel:

E delman, L evin, Levy & R ubenstein

Greenbatjm, W olfe & E rnst

Harriet F. P ilfer

Nancy F. W echsler

<̂ gĝ > 307 BAR PRESS, Inc.. 132 Lafayette Street, New York 13 - W O 6-3906

- 3-

County D irectors’ Inforaation & illetin No. 20 Hay 6 , 1963

Contraceptive Advice to AFDC Applicants

The Board voted to reword i t s policy requiring contraceptive advice for certain

AFDC applicants as follow s:

"Every applicant requesting an AFDC grant, which would include a female parent

or step-parent and/or her children or step-children, shall cause to bo presented

to the county welfare department a current written statement from a duly licensed

physician or a county health director that the said fm a le parent or step-parent

has been given adequate contraceptive advice or that she is physically incapable

o f bearing a child . This statement must be presented before such parent or

step-parent can be found e l ig ib le ."

AFTP Medical Review Board

In other action the Board voted to direct the State sta ff to request the coopera

tion o f the Modical Society to study the fe a s ib ility o f setting up, in appropriate

counties, sedic&l review teams to determine the e l ig ib i l i t y and r e -e l ig ib i l i t y of

APTD applicants and recipients and report to the Board.

Physician Payment

It also voted to ask the Interagency Technical Coeaittee on Health Planning and

Health Servicea to sake roccKaendations to the Board for establishing physician fees

and saelhod of paysent so that such payments can ba related to a unifora system for

a l l State agencies. It i s expected that physician payments w ill begin on or about

1 July 1968 and that county funds required would be either $500,Ca >D or £1,100,(XX).

To provide lim ited physician services, the 1967 General Assembly provided $500,000

State money fo r 1967-68 and $600,000 for 1968-69. The funds would have to be matched

by the counties. Inasmuch as none of the $500,000 has been used during 1967-68,

there i s & question of whether or not the Interagency Technical Ccoaittoe and

Advisory Budget Cosaaiaaion will combine the 1967-68 and 1968-69 funds for the payment

plan.