Sassower v Field Supplemental Petition for Rehearing

Public Court Documents

June 1, 1993

11 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sassower v Field Supplemental Petition for Rehearing, 1993. 54046ea4-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/527d8b06-9ee4-49bc-aabd-568045707c18/sassower-v-field-supplemental-petition-for-rehearing. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

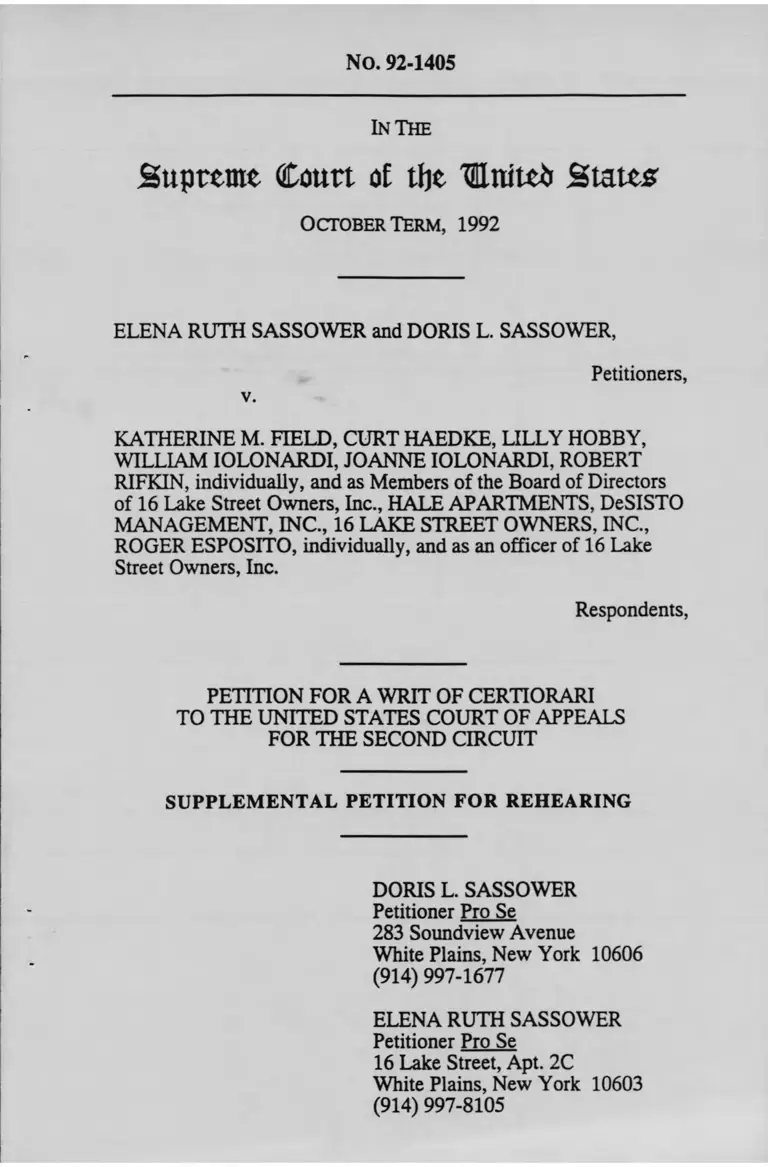

NO. 92-1405

In The

Supreme Court ot tlje United State*

October Term , 1992

ELENA RUTH SASSOWER and DORIS L. SASSOWER,

Petitioners,

v.

KATHERINE M. FIELD, CURT HAEDKE, LILLY HOBBY,

WILLIAM IOLONARDI, JOANNE IOLONARDI, ROBERT

RIFKIN, individually, and as Members of the Board of Directors

of 16 Lake Street Owners, Inc., HALE APARTMENTS, DeSISTO

MANAGEMENT, INC., 16 LAKE STREET OWNERS, INC.,

ROGER ESPOSITO, individually, and as an officer of 16 Lake

Street Owners, Inc.

Respondents,

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

SUPPLEMENTAL PETITION FOR REHEARING

DORIS L. SASSOWER

Petitioner Pro Se

283 Soundview Avenue

White Plains, New York 10606

(914) 997-1677

ELENA RUTH SASSOWER

Petitioner Pro Se

16 Lake Street, Apt. 2C

White Plains, New York 10603

(914) 997-8105

1

SUPPLEMENTAL PETITION FOR REHEARING

This Supplemental Petition is submitted to amend and clarify

the Petition for Rehearing, filed on May 14, 1993 and

calendared for this Court's conference of June 4, 1993.

Inadvertently omitted from the Petition for Rehearing through

typographical error (at p. 7) was the statutory citation to 28

U.S.C. Sec. 455(a). Petitioners' intended reliance on that

section may be seen from their quotation of the language

thereof relative to the lower courts' duty to recuse themselves

where their "impartiality might reasonably be questioned".

Petitioners further submit that this Court's recent granting of

"cert" to the case of United States v. Liteky. #92-6921, is a

supervening circumstance which is an additional reason for

granting a writ of certiorari in this case. In Litekv. this Court

will be interpreting Sec. 455(a) so as to resolve a multi-Circuit

conflict as to whether such section requires recusal for judicial,

as well as extrajudicial, bias. In that case, the Eleventh

Circuit's affirmance of the District Court's denial of recusal

rested on the fact that the District Judge's involvement in a

prior proceeding involving one of the defendants was not

viewed as extrajudicial.

The case at bar gives this Court the opportunity to add depth

and dimension to its present consideration of recusal rules. In

this case, the Second Circuit did not identify whether the bias

which was the subject of Petitioners' bias recusal motions was

of judicial or extrajudicial origin, adopting in haec verba the

conclusory statement of the District Court (CA-37)1 that:

1 The documents referred to herein are abbreviated as follows: CA-

("Cert" Appendix); Pet. ("Cert" Petition); Reply Br. (Reply Brief); Pet. for

Rehearing (Petition for Rehearing).

2

"[Petitioners] made several unsupported bias

recusal motions based upon this court's

unwilling involvement in some of the earlier

proceedings initiated by George Sassower..."

(CA-10)

Nor did the Second Circuit discuss the due process implications

of using recusal motions as a basis for sanctions. Indeed,

without any finding that Petitioners' recusal motions were

legally insufficient, false, or in bad faith, the Second Circuit

invoked inherent power to sustain a sanction award based

thereon (Pet. at 22).

Neither the District Court nor Circuit Court Decisions identified

that the aforesaid "earlier proceedings initiated by George

Sassower" were extrajudicial as to Petitioners—who were neither

party nor privy thereto—or that, by reason of said proceedings,

the District Judge acquired a "personal knowledge of disputed

evidentiary issues" which thereafter arose in Petitioners' instant

action.

As reflected by footnote 4 of the District Court's Decision

(CA-34), there existed an adversarial relationship between

George Sassower and the judges of the Second Circuit as a

result of lawsuits brought by him. Such lawsuits, resting on

serious allegations of misuse of judicial power, were brought by

him during the pendency of Petitioners' action and for several

years prior thereto. Under such circumstances, "an objective

observer would have questioned" the impartiality of any judge

sitting in the Circuit, within the intendment of 455(a). LiIjeberg

v. Health Services Acquisition Corp.. 486 U.S. 847 (1988).

3

This case documents that the "appearance of impropriety"—

which should have required immediate disqualification by both

the District and the Circuit Courts—became actualized by their

respective denial of Petitioners' right to a fair trial and to a fair

hearing of their appeal. The personal animus generated by Mr.

Sassower's unrelated litigation against the judges was such as

to make retaliation against Petitioners inevitable. This case

became the opportunity for the judges of the Second Circuit to

advance their own self-interest and that of their judicial

brethren by discrediting Mr. Sassower and adversely affecting

his right to remain in occupancy of the apartment which was

the subject of the instant litigation. Such interest by the judges

of the Second Circuit was "direct, personal, substantial, [and]

pecuniary", as proscribed by Aetna Life Insurance Co. v.

Lavoie. 475 U.S. 813 (1985)2.

The extent to which the Second Circuit recognized that it stood

to gain by an outcome adverse to Petitioners is established by

its Decision (CA-6-19) which—like that of the District Court

(CA-28-55)—is totally devoid of evidentiary support in the

record as to all material facts and, on its face, abandons

fundamental legal standards and bedrock decisional law.

2 Although all such criteria were met in this case, it may be noted

that Justice Brennan stated in his concurring opinion to Aetna.supra. at 829-

30:

"I do not understand that by this language the Court states

that only an interest that satisfies this test will taint the

judge's participation as a due process violation...

Moreover, ... an interest is sufficiently 'direct' if the

outcome of the challenged proceeding substantially

advances the judge's opportunity to attain some desired

goal even if that goal is not actually attained in that

proceeding."

4

As illustrative of the aberrant decision-making at issue, the

Second Circuit's Decision (CA-6-19), on its face:

(1) conflicts with Christiansburg v. E.E.Q.C..

434 U.S. 412 (1978), by maintaining intact the

District Court's $92,000 award under the Fair

Housing Act, notwithstanding it vacated same

based on Christiansburg (CA-12-13; Pet at lb-

19)3;

(2) conflicts with Alveska Pipeline v. Wilderness

Society. 421 U.S. 240 (1975), by using inherent

power to effect substantive fee-shifting4 (Pet. at

19);

(3) conflicts with Business Guides v. Chromatic

Communications. 498 U.S. 533 (1991), by

allowing the District Court's admittedly

uncorrelated $50,000 award under Rule 11 (CA-

3 The unprecedented nature of the Second Circuit's "trumping" of the

standard of Christiansburg was set forth in the Petition (at 17) as follows:

"Research has failed to find a single case, before or after

1988, in which a federal court has resorted to inherent

power to shift a totality of litigation fees against losing

civil rights plaintiffs, where, as here (CA-13), the action

was found not to be 'meritless' under the standards of

Christiansburg."

4 Such substantive fee-shifting is evident from the face of the

Judgment (CA-23-4) affirmed by the Second Circuit (CA-20), which made

distributive allocations to the respective Respondents solely according to the

District Court's Fair Housing Act award (Pet. at 9; 13; 19). As pointed out

in the Petition (at p. 19, fn. 14), the effect of the Second Circuit's vacatur

of the award under the Fair Housing Act should have rendered the Judgment

based thereon a nullity.

5

52-3) to remain intact, notwithstanding it

vacated the Rule 11 award for failing to identify

a single sanctionable document (CA-14; Pet. at

7, fn. 4; 19-20);

(4) conflicts with the plain language of 28

U.S.C. Sec. 1927 by keeping intact an

unidentified portion of the $42,000 sanction

awarded thereunder as to Doris Sassower (CA-

at 14-6); which unidentified sum was totally

uncorrelated to any sanctionable conduct—let

alone to any "excess costs" "reasonably

incurred" (CA-5; Pet. at 7-8; 19-21);

(5) conflicts with Chambers v. Nasco. 111 S.Ct.

2123 (1991)5—the sole authority on which it

relies for its use of inherent power—by, inter

alia.: (a) omitting the requisite finding that

available sanctioning rules and provisions were

inadequate so as to establish any "necessity" for

such invocation; and (b) omitting the requisite

finding that due process had been met before

inherent power was invoked (Pet. at 21-24;

Reply Br. 1-6);

(6) violates the Code of Judicial Conduct by

including dehors the record matter, inadmissible

hearsay, and knowingly false and defamatory

5 The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, which

participated in this case as amicus curiae before the Second Circuit, recently

cited the Second Circuit's Decision as "an unwarranted expansion of

Chambers" "indicative of a growing trend too undermine the American Rule

as explicated in Alveska..." (see Appendix to Pet. for Rehearing, para. 6).

S U P R E M E C O U R T O F T H E U N I T E D S T A T E S

O F F I C E O F T H E C L E R K

W A S H I N G T O N . D. C. 2 0 5 4 3

June 7, 1993

Mr. Charles Stephen Ralston

NAACP Legal Defense Fund

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

Re: Elena Ruth Sassower and Doris L. Sassower

v. Katherine M. Field, et a l .

No. 92-1405

Dear Mr. Ralston:

The Court today entered the following order in the above

entitled case:

The petition for rehearing is denied.

Very truly yours,

William K. Suter, Clerk

6

material obtained s x parte and as to which

Petitioners were given no notice or opportunity

to be heard (Pet. at 10-11; Reply Br. at 7; Pet.

for Rehearing at 4).

Not apparent on its face was the Second Circuit's disregard of

United States v. Aetna Casualty & Surety Co.. 338 U.S. 366

(1949), and Brocklesbv Transport v. Eastern States Escort. 904

F.2d 131 (1990), when it denied—without discussion—

Petitioners' threshold jurisdictional objection that the fully-

insured defendants were not the "real parties in interest" and

that the sanction award was a "windfall" to them, proscribed by

countless decisions of this Court, including Henslev v.

Eckerhart. 461 U.S. 424 (1983) (Pet. at 9; 10; 25-26; 27).

These and other deviant aspects of the Second Circuit's

Decision were detailed—with citation to legal authorities—in

Petitioners' Petition for Rehearing and Suggestion for Rehearing

En Banc6. Said Petition further showed (at pp. 10-11) that the

"facts" relied on by the Second Circuit to support its $92,000

fee-shifting award were wholly false and contradicted bv the

record7. The refusal of the judges of the Second Circuit—each

of whom were furnished a copy of that Petition—to grant

rehearing to Petitioners is, in view of that Petition, an

abdication of their adjudicative responsibilities so extraordinary

as to be confirmatory of a bias overriding those duties.

6 A copy of said Petition for Rehearing is on file with this Court as

Exhibit "C" to Petitioners' December 2, 1992 motion to extend time to file

their Petition for Certiorari.

7 For the convenience of the Court, the pertinent excerpt from pages

10-11 was annexed as a Supplemental Appendix to Petitioners' Reply Brief.

7

The Second Circuit's actual knowledge that the record and

controlling law would not support imposition of sanctions

against Petitioners is unmistakable from review of the appellate

submissions before it. Those submissions leave no doubt that

the reason the Second Circuit did not identify in its Decision

Petitioners' arguments on appeal—which it summarily dismissed

as "totally lacking in merit" (CA-18; Pet. at 11)—is because any

one of those arguments would have sufficed in and of itself for

vacatur of the sanction award against them (Pet at. 9-10).

Likewise, the fact that the Second Circuit's Decision does not

identify what is being sanctioned under inherent power is no

accident. Rather, as can be seen from the appellate

submissions, it is a reflection of the Second Circuit's actual

awareness that no sanctionable conduct by Petitioners can be

identified—there being none. Similarly, the Second Circuit's

failure to make the requisite threshold determination as to due

process—including Petitioners' right to an impartial

decisionmaker-bespeaks its full knowledge that Petitioners' due

process rights were violated by a district judge whose actual

bias and malice were indisputably proven by his decision which

falsified, fabricated, and omitted all material facts in order to

do Petitioners maximum injury (Pet. at 9).

Heretofore, Petitioners have stated that their Rule 60(b)(3)

motion is "dispositive of every issue before this Court" (Reply

Br. at 10, Pet. for Rehearing, at 6). However, to properly

evaluate Petitioners' right to recusal-not only of the District

Court, but of the Second Circuit—it is the appellate submissions

that were before the Second Circuit which must be examined

by this Court.

8

The gravity of the charges raised in the Petition for Rehearing-

that federal judges, sworn to uphold the rule of law, have

knowingly and deliberately perverted our sacred judicial process

to advance ulterior retaliatory goals— removes this case from

the ordinary discretionary review presented by other

applications for certiorari. This is particularly so where, as

here, the District and Circuit Courts' Decisions are so aberrant

on their face as to be suspect.

This case, considered as a companion to Litekv. will give this

Court an extraordinary and essential opportunity to redefine and

reinforce the high standards Congress intended to be met by

federal judges whose "impartiality might reasonably be

questioned".

Had the Second Circuit applied the unequivocal congressional

mandate of 455(a) and the constitutional mandate of due

process, it could neither have sustained the District Court nor

sat on the case itself since both courts were required thereunder

to disqualify themselves, s m sponte. for actual and apparent

bias. Aetna, supra: Lilieberg. supra.

9

CONCLUSION

For all the foregoing reasons, as well as those contained in the

Petition for Rehearing, the Petition for Certiorari, and the Reply

Brief, Petitioners respectfully pray that this Court, in the

exercise of its "power of supervision", grant rehearing, vacate

the Order denying certiorari, and grant the Petition for

Certiorari so as to review the Decision and Judgment below.

Respectfully submitted,

DORIS L. SASSOWER

Petitioner ElQ Sfi

283 Soundview Avenue

White Plains, New York 10606

ELENA RUTH SASSOWER

Petitioner Em Ss

16 Lake Street, Apt. 2C

White Plains, New York 10603

June 1, 1993